Abstract

Heterogeneous clinical and neuropathological features have been observed in the recently described neuronal intermediate filament inclusion disease (NIFID). The immunohistological findings common to all cases are α‐internexin and neurofilament‐positive neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions, which have not been found in comparable density in other neurodegenerative disorders. Notwithstanding these common features, the cases reported so far have shown differences concerning age at onset, constellation and dominance of symptoms as well as type and distribution of additional neuropathological findings. Here we present the first NIFID case that exhibits severe involvement of lower motor neurons. Also, this patient may have had a clinical onset of disease in early childhood, as she was diagnosed as having dysarthria, which could not be attributed to any other cause at the age of 3 years. This case is a further contribution to the spectrum of this novel neurodegenerative disease.

INTRODUCTION

Two neuronal intermediate filaments (IFs)—neurofilament (NF) and α‐internexin (α‐IN)—have received increased attention in recent years, as they have been identified as components of neuronal inclusion bodies in patients with neurologic and psychiatric symptoms. Yokoo et al were the first to report on a 61‐year‐old male patient with atrophy and eosinophilic neuronal inclusion bodies, which stained positive for NF in immunohistochemistry, in the frontal and temporal cortex, subcortical gray matter and substantia nigra. This patient had suffered from mental decline, pyramidal and extrapyramidal deficits, speech impairment including mutism for 13 years (46). Jaros et al reported on a new form of neurodegenerative disease in a 55‐year‐old woman after a 3‐year period of rapidly progressive dementia with psychiatric signs and extrapyramidal deficits, which neuropathologically was characterized by neuronal cytoplasmic eosinophilic inclusions stained positive with antibodies against ubiquitin and NF, but negative for tau and α‐synuclein, in many cortical neurons, subcortical gray matter and substantia nigra (23). A similar clinical and histological picture was found in a 23‐year‐old woman with a 5‐year disease duration (7). Later on, around ten more reports appeared with similar case histories, histological and immunohistochemical pictures (3, 16, 19, 25, 26, 35). The disease was named NF inclusion disease by Cairns et al or NF inclusion body disease by Josephs et al (7, 25). Cairns et al re‐investigated the cases mentioned above and discovered abundant α‐internexin positive neuronal inclusions in addition to the phosphorylated and un‐phosphorylated NF positive inclusions (6, 8, 9). This novel disease entity therefore was named neuronal intermediate filament inclusion disease (NIFID). Further investigations have shown that the detection of numerous α‐IN inclusions is very specific for NIFID (8, 44).

In contrast to the rather uniform appearance of the neuronal inclusions composed of abnormally aggregated neuronal IF, there is considerable heterogeneity of the anatomical distribution of the inclusion bodies in the brain and of additional neuropathological findings. The clinical picture is heterogeneous and there are no paraclinical markers which would allow the diagnosis of NIFID during lifetime. There is a broad spectrum concerning age at onset, disease duration and combination of symptoms. The clinical differential diagnoses include frontotempral dementia (FTD), motor neuron disease (MND), Pick disease and corticobasal degeneration (6, 15). To date no familial cases of NIFID have been reported. Cairns et al concluded from their retrospective study that NIFID should be taken into consideration in cases with no family history of FTD, young age at onset (mean 40 years), behavioral and personality changes, cognitive impairment, language impairment, extrapyramidal and pyramidal signs and a disease duration of about 4.5 years (6). These criteria must be extended by the very recently published case of a NIFID patient without dementia (26).

IFs are one of three filamentous systems of the eukaryotic cytoskeleton besides microfilaments and microtubules. Within the IF system, there are at least five classes of proteins which differ in immunologic specificity and tissue distribution, such as vimentin in mesenchymal cells or keratin in epithelial cells (38). Neuronal IFs are the NFs with the three subgroups defined by their molecular weight NF‐L (light), NF‐M (medium), NF‐H (high), α‐internexin (α‐IN) and peripherin (34). According to their sequence homology and intron‐exon organization pattern, NF and α‐IN have been classified as type IV and peripherin as type III IFs (11, 27, 28, 33, 42). As developmental studies have shown, neuronal IFs seem to play a role in the generation and maintenance of the structure of neurons and their processes as well as in intracellular transport (29, 31). On the other hand, experiments with knock‐out mice have demonstrated that none of the neuronal IFs are absolutely essential for nervous system development (31).

NFs are composed of three subunits defined by their molecular weight: NF‐L (68 kDa), NF‐M (160 kDa) and NF‐H (200 kDa). The NF proteins are synthesized in the perikaryon, phosphorylated and glycosylated in the axons, axonally transported and finally are degraded in the synapse [Review: (2, 34)]. The expression of the NF triplet proteins is not simultaneous during development (10). They have different functions concerning axon growth, axon maturation, regeneration and neuronal protection, which depend on posttranslational modifications such as phosphorylation, dephosphorylation and glycosylation at the right moment. These posttranslational modifications are essential for physiological and pathological processes (2, 34). Physiologically, the phosphorylation of the NF tail domain takes place in the axon. If that occurs abnormally in perikaryon, the phosporylated NFs form aggregates and accumulate in the cell body. This has been reported for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Alzheimers disease (AD), Parkinson disease (PD) and other disorders (21, 36, 40, 41). On the other hand, there is evidence that cytosolic accumulation of NF‐H functions protectively by slowing down the progress of the disease in mutant SOD1 (superoxide dismutase) mice (ALS), while severe phenotypes were seen in NF‐L over‐expressing mice and in NF‐M/H double knock‐out mice (13, 17, 22, 45). Mutations in NF‐genes have been associated with ALS (NF‐H) (1, 18, 43), with PD (NF‐L, NF‐M) (30, 32) and with Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth disease (NF‐L) (14, 20, 24, 37, 47).

α‐IN is a 66 kDa protein, first described and investigated by Pachter et al (38). Developmental studies described that the expression of α‐IN is high, especially in developing neurons following that of vimentin and preceding that of NF‐L (29). It is evenly distributed in the perikarya of undifferentiated cells, axonally transported along with NF‐L and later found at very low levels in comparison to the developing brain and to NFs in neuronal processes after the formation of neurites (29, 39). α‐IN can self‐assemble into homopolymers or co‐assemble with vimentin, glial filament protein or NFs (12). As the axon caliber in the developing nervous system is small while the α‐IN level is high, α‐IN may be related to forming an IF network in developing axons while NFs are responsible for increasing the axonal caliber (38).

In the normal adult CNS α‐IN, NF‐L and NF‐M have been detected in all layers of the neocortex and subcortical white matter, in fibres of the cerebellar white matter and in cerebellar medium‐ and large‐caliber axons of granular and molecular layer. The small axons of basket cells as well as layer II neurons stained for α‐IN. The cell bodies of Purkinje cells and granular cells did not stain for these IFs. A small number of α‐IN inclusions have been found in neurons of patients with AD, PD and frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD)‐MND (8).

CASE HISTORY

This female patient was born as the second child of healthy parents with unremarkable neurological or psychiatric family history. The pregnancy and delivery were normal. The weight at birth was 3420 g, body length 50 cm, Apgar‐Score 10. During breast‐feeding, the child was felt to be weak during the first weeks after birth. Because of a slowed psychomotor development at the age of 3 months, she was seen by a pediatrician who diagnosed a spastic movement disorder and prescribed physiotherapy according to the Bobath concept and a hip abduction splint. At the age of 13 months, her movements had become normal, she walked independently at 16 months. In addition to these motor problems, her parents noticed a delay in speech development of about 1 year in comparison to her healthy siblings as well as a scanning and unarticulated speech, while her hearing ability was considered normal. When she was 4 months old, her parents were concerned about her insufficient weight gain, with a body weight below the 3rd percentile. For the evaluation of this problem, she was finally admitted to a university pediatric center at the age of 3 years. At that time, her neurological examination was normal except for a mild dysarthria. Because of laboratory findings, a diagnosis of celiac disease was made but later revoked. In the following years, her body weight normalized but her psychomotor development was inadequate. According to her parents, her movements were “clumsy”, her painting and writing were inaccurate. While eating, she constantly had uncontrolled protrusion of her tongue. During puberty, difficulties arose in her social behavior and with personal hygiene. Nevertheless, she began a professional training for geriatric care, which she broke off a short time before the final exam. At the age of 21 years, she gave birth to a premature girl. Until her little daughter turned 5 years, she seemed to cope with the care for her child, but neglected homemaking. Then the grandparents took over the care for their granddaughter because they felt that the mother was no longer able to do so.

At about the age of 26 years, a sudden decline of motor and cognitive functions became apparent. She started to show “odd” movements, her gait became unsteady and she suffered frequent falls. As she did not show any insight into her own situation, she had to be persuaded to see a neurologist. The clinical examination showed an extremely disheveled appearance and a childish behavior. She exhibited opsoclonus and facial hypokinesia, mild pronator drift on the left and marked impairment of diadochokinetic movements of both hands. Muscle tone was increased, especially in both legs. Walking was very unsteady. She displayed Trendelenburg gait with a marked hyperextension of her knees and dystonia of her left arm while walking. The somato‐sensory evoked potentials showed a decreased cortical potential after stimulation of the left median nerve. Motor evoked potentials were indicative of a pyramidal tract lesion to the left arm. Her electroencephalogram showed intermittent brief episodes of 4/s spike‐wave complexes. The electromyogram (EMG), motor and sensory neurography and cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were normal. Cerebral positron‐emission tomography (PET) revealed mild hypometabolism in the right precentral gyrus. The CSF was normal.

During the following year, her condition deteriorated rapidly and she was unable to walk unassisted. At that time, she exhibited a childish and naive behavior, frontal dysexecutive signs with slowing of intellectual processes, diminished inhibition of affective response, restlessness, unmotivated laughter. On neuropsychological examination, her verbal memory was reduced and perseverations in figural tasks were noticed. On neurological examination, she had a marked symmetric spastic tetraparesis with hyperextension of her knees while standing, brisk exaggerated deep tendon reflexes, spontaneous pyramidal signs bilaterally. Her hand muscles were atrophic. No sensory deficits were found. The motor evoked potentials revealed severely progressive lesions of pyramidal tracts with pathological motor evoked potentials (MEPs) of both arms and left leg. EMG and nerve conduction velocity studies (NCSs) were still normal. Cerebral MRI showed symmetric hyperintensity on T2‐weighted images in both dorsal internal capsules, no signs of iron deposits. Cranial PET showed a progressive bilateral hypometabolism in precentral cortices in comparison to the preliminary examination.

She became completely bedridden 3 years after the onset of symptoms. She seemed to neglect her surroundings, lying in bed and constantly staring without fixation. Voluntary movements were scarce as muscles became severely atrophic. Because of dysphagia she had to be fed parenterally. She spent the last 2 years of her life in a nursing home. At the time of death her Body‐Mass‐Index was 15.8 kg/m2 (42 kg/1.63 m). She died at the age of 30 years. At that time, her four brothers and her 9‐year‐old daughter were healthy. Clinical differential diagnoses were cerebral palsy, hereditary spastic paraparesis, Rett syndrome and Hallervorden–Spatz disease. A complete autopsy was performed. Pneumonia with cardiovascular failure was declared as cause of death

NEUROPATHOLOGICAL FINDINGS

Parts of a formalin‐fixed sectioned brain weighing 1200 g and parts of the spinal cord were received for neuropathological investigation. Gross examination showed regular gyration of the cortex with signs of mild edema; there was mild dilatation of the lateral ventricles as a sign of brain atrophy. The basal ganglia, cerebellum, substantia nigra and the spinal cord were macroscopically inconspicuous. Certain regions such as the subthalamic nucleus were not available for neuropathologic examination.

Histology. Histological examination was performed on 4 µm thick sections of numerous regions of formalin‐fixed and paraffin embedded cerebrum, cerebellum, brainstem and spinal cord. Hematoxylin and eosin, iron stain as well as Gallyas silver stains were performed using standard techniques. Immunohistochemistry was performed with antibodies directed against phosphorylated tau (AT8, 1 : 200, Innogenetics, Ghent, Belgium), α‐synuclein (15G7, 1 : 10), ubiquitin (1 : 300, Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), neurofilament (p‐NF‐L, p‐NF‐H) (1 : 300, Dako), α‐internexin (1 : 200, Zymed, San Francisco, USA), αB‐crystalline (1 : 500, Calbiochem, Nottingham, UK).

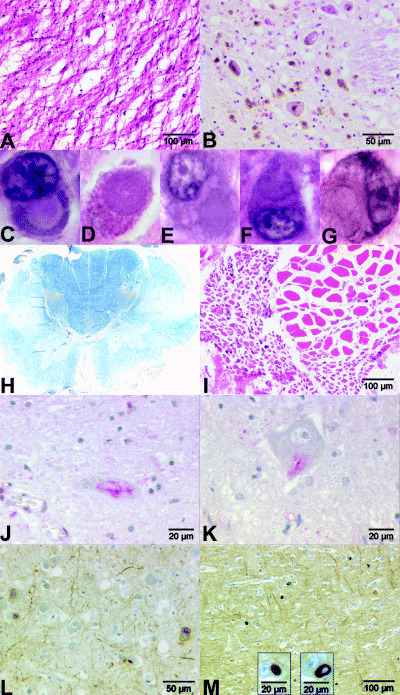

Histological examination of H&E stained sections of the temporal, occipital and parietal cortex was largely inconspicuous except for a small number of achromatic, slightly ballooned neurons. In the precentral gyrus, the architecture of the cortical layers was completely lost; severe neuronal degeneration with neuronal loss, a small number of achromatic neurons and astrocytic gliosis in gray and white matter were noted. Severe changes were also found in the caudate nucleus bilaterally with remarkable atrophy and gliosis with nearly complete loss of neurons; anterior parts of the caudate seemed slightly less affected than posterior parts (Figure 1A). The putamen showed mild gliosis, loss of neurons and few achromatic neurons. In the globus pallidus externus we found massive gliosis with reduction of neurons and few diffusely distributed brownish, iron positive dot‐like pigment deposits. By comparison, the globus pallidus internus was minimally affected. In the claustrum we found a mild gliosis with well‐preserved neurons. The neurons of the lateral geniculate body, nucleus basalis of Meynert and thalamus were also well preserved. A few of the hippocampal neurons included Hirano bodies, in particular in the CA2 region. The corpus callosum, mainly the anterior part, was mild demyelinated. The cerebellar cortex revealed no pathological changes. In the midbrain, the neurons of the nucleus ruber and the trigeminal mesencephalic nucleus appeared normal. The substantia nigra and locus coeruleus showed neuronal degeneration with severe loss of melanin pigment (Figure 1B). In the medulla oblongata the neurons of the inferior olivary nucleus, the nuclei cuneatus and gracilis, nucleus n. X as well as spinal trigeminal nucleus appeared normal. Only a small number of neurons of the arcuate nucleus, the hypoglossal nucleus and nucleus ambiguus showed chromatolytic changes. In addition to these findings, we observed weakly eosinophilic to glassy, cytoplasmic neuronal inclusions of varied forms from round to irregular and lobulated in the following regions: cerebral cortex, putamen, caudate nucleus, pallidum, hypothalamus, dentate nucleus, the pontine nuclei and arcuate nucleus (Figure 1C–G).

Figure 1.

Different histological sections with HE stain (A–G,I). A. Severe atrophy in the caudate nucleus. B. Pigment incontinence of substantia nigra. Weakly eosinophilic to glassy, cytoplasmic neuronal inclusions (magnification 100×) in following regions (C–G): C. parietal cortex; D. putamen; E. dentate nucleus; F. pons; G. arcuate nucleus. H. Severe demyelination of the pyramidal tracts in spinal cord. LFB‐PAS stain. I. Neurogenic atrophy of muscle quadriceps femoris. Immunohistochemistry with an antibody against ubiquitin (J,K). Skein‐like inclusions in the spinal cord: J. cervical; K. lumbal. L. Immunohistochemistry with an antibody against neurofilament (pNF‐L, pNF‐H). Neuronal inclusions in the frontal cortex. M. Immunohistochemistry with an antibody against α‐internexin. Neuronal inclusions in the frontal cortex.

In the sections of the cervical, thoracic and lumbar spinal cord the number of motor neurons was severely reduced, some showed achromatic changes and neuronophagia was noted. The sensory root ganglia and the spinal ganglia did not seem to be affected. The LFB‐PAS stain revealed severe demyelination of the ventral and lateral pyramidal tracts (Figure 1H). There were glial cells and macrophages among the fibers. The posterior columns were normal. Axonal spheroids were very rare throughout the CNS. The quadriceps femoris muscle showed signs of neurogenic atrophy (Figure 1I). The LFB‐PAS stain of the sciatic nerve did not show any demyelination.

Iron‐positive deposits were found diffusely distributed in the internal part of globus pallidus, corpus callosum, claustrum and more prominently in the putamen, caudate and external part of globus pallidus. Using the Gallyas silver stain, argyrophilic neuronal or glial inclusions were not found in any of the regions investigated.

Immunohistochemistry. The results of immunohistochemical studies are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Distribution of neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions. Abbreviations: — = not tested; 0 = no inclusions; X = only few inclusions; XX = moderate number of inclusions; XXX = numerous inclusions. FC = frontal cortex; PG = precentral gyrus; TC = temporal cortex; PC = parietal cortex; OC = occipital cortex; NC = caudate nucleus; Gpe and Gpi = external and internal nucleus of globus pallidus; GD = dentate gyrus, CA = cornu ammonis; SC = spinal cord; SN = substantia nigra; NR = nucleus rubber; LC = locus coeruleus; Nar = arcuate nucleus; Ol = nucleus olivaris inferior; (v)Np = (ventral) nuclei pontis; cerv. = cervical; lumb. = lumbal; Ndt = nucleus dorsalis tegmenti.

| Neurofilament | α‐internexin | Ubiquitin | α‐synuclein | AT 8 | Gallyas | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FC | XX | XXX | XXX | 0 | — | 0 |

| PG | X | XXX | XX | — | — | — |

| TC | X | XXX | XX | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PC | XX | XX | XX | — | — | — |

| OC | XX | XXX | — | — | — | — |

| NC | 0 | XXX | XX | 0 | — | 0 |

| Putamen | 0 | XXX | XX | 0 | — | 0 |

| GPe | 0 | X | 0 | — | — | 0 |

| GPi | 0 | X | 0 | — | — | 0 |

| GD | X | X | X | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CA | X | X | X | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| EC | — | X | X | — | 0 | — |

| Thalamus | — | XX | 0 | 0 | — | 0 |

| Cerebell. cortex | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | — | — |

| Dentate nucleus | X | X | 0 | — | — | — |

| Mesenceph. | X SN (NR) | X (SN, NR) | X (SN, NR) | 0 | — | 0 |

| Pons | X (vNp) | XX (Np,Nar) X (LC, Ndt) | XX (vNp) X(LC) | — | — | |

| Medulla obl. | X (Nar) | X (Nar, Ol,) | X (Ol), 0 (Nar) | 0 | — | 0 |

| SC | 0 | 0 | X (cerv., lumb.) | — | — | — |

Using an antibody against ubiquitin, cytoplasmic inclusions were detected in many neurons, in particular those of the lower layers of the frontal cortex and less frequently in the temporal and parietal cortex. In the remaining neurons of the caudate nucleus and putamen, we found a small number of ubiquitin‐labeled cytoplasmic inclusions. In the pyramidal cells of the hippocampus (CA1 region) and the dentate gyrus, only small numbers of ubiquitin‐positive neurons were found. Very few neurons of the substantia nigra, nucleus ruber, locus coeruleus, nucleus tegmentalis in the pons, few neurons of the inferior olive and nucleus ambiguus revealed a positive cytoplasmic stain with an antibody against ubiquitin. In some neurons of the hypoglossal nucleus we found granular ubiquitin‐positive staining of the cytoplasm. Interestingly, some skein‐like inclusions (SLIs) were detectable in lumbar and cervical motor neurons (Figure 1J,K).

Using an antibody against the phosphorylated form of the 200 kDa and 70 kDa components of NFs, we found cytoplasmic but no intranuclear inclusions in neurons of the lower layer of the frontal (Figure 1L), parietal and occipital cortex. Only a small number of neurons with cytoplasmic inclusions were found in the temporal cortex, precentral gyrus and hippocampus as well as in the substantia nigra, ventral pons (nuclei pontis) and arcuate nucleus.

The most impressive inclusion bodies were found with an antibody against IF α‐internexin (α‐IN). This antibody revealed very pleomorphic round, tail‐like or half‐moon‐like neuronal intracytoplasmic inclusions. They were located mainly in the lower layers, most commonly in the precentral gyrus, frontal (Figure 1M), inferior temporal and occipital cortex, less frequently in the parietal and superior temporal cortex. The white matter did not exhibit these inclusions. Inclusions were found in remaining neurons of the caudate nucleus, putamen and thalamus, only a few in the pallidum, hippocampus, dentate gyrus and entorhinal cortex. The Purkinje cells in cerebellum showed a diffusely stained cytoplasm but no inclusions. Only very few neurons of the dentate nucleus had α‐IN‐positive cytoplasmic inclusions. In the brainstem, the most frequent inclusions were found in the ventral pons (nuclei pontis) and, to a lesser degree, in the substantia nigra, nucleus ruber, nucleus dorsalis tegmenti, locus coeruleus, arcuate nucleus, olive and nucleus intercalatus. The remaining motor neurons in the spinal cord did not have α‐IN‐positive inclusions. There were no swollen axons or spheroids which stained positive with α‐IN.

Using an anti αB‐crystalline antibody, we identified very few ballooned neurons in the frontal cortex. Using the antibodies against α‐synuclein and hyperphosphorylated tau protein (AT8), we could not detect any neuronal or glial inclusions.

Using an antibody against macrophages and microglial cells (CD 68), we found many positive cells in the ventral and lateral corticospinal tract as well as diffusely distributed and in perivascular locations in the anterior horn of the spinal cord. Only very isolated CD68‐positive cells were found in the precentral gyrus but not in the striatum. The same distribution pattern was found using an antibody against the cytotoxic T‐cells (CD 8), with a more prominent stain of perivascular areas. No positive cells were found with an antibody against B‐cells (CD 20).

DISCUSSION

This is a case history of a young woman with no family history of neurological or psychiatric disorders, who showed first signs of neurological disease with spasticity and dysarthria soon after birth and behavioral change during childhood. She developed pyramidal and extrapyramidal signs as well as frontal lobe signs a few years before death. The disease progression was very rapid during the last 3 years before she died at the age of 30 years. The clinical differential diagnoses were cerebral palsy, hereditary spastic paraparesis, Rett syndrome and neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA)‐1 (formerly Hallervorden–Spatz disease).

A postmortem examination of the CNS showed severe neuronal loss in the precentral gyrus, caudate nucleus, spinal cord motor neurons and pigment loss in the substantia nigra. Many neurons in the cortical and subcortical gray matter and the brainstem contained cytoplasmic eosinophilic inclusions, which stained positive for neurofilament (pNF‐L, pNF‐H) and even more for α‐IN. These inclusions were also found in regions not affected by neuronal loss. Furthermore, there was severe degeneration of the pyramidal tracts as well as ubiquitin positive, but NF and α‐IN negative inclusions in remaining motor neurons (MNs) in the spinal cord, moreover neurogenic degeneration of the quadriceps femoris muscle (no other skeletal muscle was available for neuropathologic examination). There were no tau‐ or α‐synuclein inclusions and no argyrophilic inclusions in the gray or white matter of the cerebrum, cerebellum, brainstem or spinal cord.

NIFID and ALS must be discussed as possible diagnoses from a neuropathological point of view. In regard to the published summary of clinical findings in NIFID, we found the following deficits in our patient: language deficit and mutism (late), memory loss, executive dysfunction, severe behavioral change, frontal lobe signs, severe loss of insight, bilateral pyramidal signs (tetraspasticity), extrapyramidal signs (dystonia, rigidity) and oculomotor abnormalities. Thus the neurological and psychiatric deficits at the time of clinical presentation, the rapid disease progression during the last 3 years as well as a negative family history of dementia are consistent with the cases reported by Cairns et al (6). Since the spastic movements after birth were resolved by physiotherapy, it does not seem likely that they were early signs of the disease. It is debatable whether her early difficulties in speech development, her clumsy movements and uncontrolled tongue protrusion since childhood as well as her progressive behavioral deficits since early puberty may be an expression of very early disease onset of NIFID.

The regions of neuronal loss and the characteristics of the neuronal inclusions in our case are mainly in accordance with the published NIFID cases, whereas the degree of these changes can vary between the patients as described (6). The regions with the most severe neuronal loss and the highest number of inclusions in NIFID are the frontal and temporal cortex, putamen and caudate nucleus. Deviating from published NIFID cases our patient showed no cortical neuronal loss besides the frontal cortex, but more severe neuronal loss than has been published in the substantia nigra and the anterior horn of the spinal cord and more inclusions in the parietal and occipital lobes.

In addition, the case presented here showed neuropathological changes typical of ALS. We found severe loss of upper and lower motor neurons, SLIs, severe demyelination of the lateral and anterior corticospinal tract and only very few spheroids. Minor changes reminiscent of ALS have been noted in previously reported NIFID cases, however, the severity and constellation of changes noted in the patient presented here are exceptional. Bigio et al observed neuronal loss and neuronophagia in the anterior horn of the uppermost cervical spinal cord with NF positive and ubiquitin negative hyaline conglomerate‐like inclusions but ubiquitin positive SLIs. There was no pyramidal tract demyelination (3). When Cairns et al investigated this case, they did not describe SLIs in the spinal cord, which shows that SLIs might be a less common finding in NIFID than in ALS (6). Mackenzie at al. published a case with severe lateral and anterior corticospinal tract demyelination and a normal number of spinal MNs containing very few Bunina bodies and NF positive axonal spheroids (35). One further NIFID‐case was found to have spinal neuronal Bunina bodies (19). None of these three patients had clinical signs of lower MND. In accordance with the published NIFID cases there were no clinical signs of lower MN involvement such as fasciculations, EMG or NLG abnormalities in our patient.

The revised version of the El Escorial Criteria allows to make a diagnosis of ALS even if there are no clinical but only neuropathological signs of lower MN involvement as in our case (4, 5). Following these criteria, the extrapyramidal symptoms and dementia in our case also do not exclude the diagnosis of ALS but could suggest an ALS‐Plus‐syndrome. Cairns et al studied neuronal inclusions in different neurological diseases and found that the ubiquitin positive inclusions in MND were not labeled with an antibody against α‐IN; only rarely were α‐IN positive swollen axons and spheroids and neuronal inclusions in granule cells of dentate gyrus seen in FTLD‐MND (8). Thus the determining finding to diagnose NIFID were the numerous α‐IN‐positive inclusions, which in that amount could not be found in any other neurodegenerative disease (8, 44). Furthermore, we saw severe atrophy of caudate and substantia nigra, which has not been reported in MND.

This is the first report of a NIFID case with additional neuropathological signs of severe upper and lower motor neuron involvement and SLIs as found in ALS. This constellation raises the question of whether this is a chance coincidence of two rare diseases in one patient or whether there is a shared etiologic or pathogenetic denominator for ALS and NIFID. As minor signs of ALS have been noted in previously published cases of NIFID and few NF and α‐IN inclusions have been described in cases of ALS or FTLD‐MND, the latter hypothesis seems to be a realistic possibility (3, 8, 19, 35). At least this shows that MND‐type changes (e.g. SLIs) in NIFID are not an unusual finding.

As the spinal cord was available only in less than half of NIFID cases described so far and again SLIs are not present in all motoneurons it might have been overlooked that MND‐type changes are also a feature of NIFID or at least of a NIFID‐subgroup. That there might be a neuropathological defined NIFID‐subgroup could further be concluded from the findings of Cairns et al (6), who described neurons with cytoplasmic and rare ubiquitin‐positive intranuclear inclusions only in NIFID cases with MND‐type inclusions.

These intranuclear inclusions as well as the SLIs did not stain with antibodies against IFs in contrast to neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions in the same case. This might point to different components in intranuclear and SLIs on the one hand and cytoplasmic inclusions on the other, although both are characteristics of the same disease. Although the ubiquinated protein in the intranuclear inclusions and SLIs is unknown, we could speculate that the immunhistochemically different inclusions in NIFID and MND have a partly common pathway in early generation and therefore belong to one group of neurodegenerative disease. This has to be clarified by further pathological and biochemical studies.

Thus MND, FTLD‐MND and NIFID may represent a continuum of etiologically related diseases with a wide spectrum of neuropathological changes and variable overlap of phenotype.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank A. Henn and I. Pigur for expert technical assistance in histological processing.

REFERENCES

- 1. Al Chalabi A, Andersen PM, Nilsson P, Chioza B, Andersson JL, Russ C, Shaw CE, Powell JF, Leigh PN (1999) Deletions of the heavy neurofilament subunit tail in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum Mol Genet 8:157–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Al Chalabi A, Miller CC (2003) Neurofilaments and neurological disease. Bioessays 25:346–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bigio EH, Lipton AM, White CL III, Dickson DW, Hirano A (2003) Frontotemporal and motor neurone degeneration with neurofilament inclusion bodies: additional evidence for overlap between FTD and ALS. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 29:239–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brooks BR (1994) El Escorial World Federation of Neurology criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Subcommittee on Motor Neuron Diseases/Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis of the World Federation of Neurology Research Group on Neuromuscular Diseases and the El Escorial “Clinical limits of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis” workshop contributors. J Neurol Sci 124 (Suppl.): 96–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brooks BR, Miller RG, Swash M, Munsat TL (2000) El Escorial revisited: revised criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord 1:293–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cairns NJ, Grossman M, Arnold SE, Burn DJ, Jaros E, Perry RH, Duyckaerts C, Stankoff B, Pillon B, Skullerud K, Cruz‐Sanchez FF, Bigio EH, Mackenzie IR, Gearing M, Juncos JL, Glass JD, Yokoo H, Nakazato Y, Mosaheb S, Thorpe JR, Uryu K, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ (2004) Clinical and neuropathologic variation in neuronal intermediate filament inclusion disease. Neurology 63:1376–1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cairns NJ, Perry RH, Jaros E, Burn D, McKeith IG, Lowe JS, Holton J, Rossor MN, Skullerud K, Duyckaerts C, Cruz‐Sanchez FF, Lantos PL (2003) Patients with a novel neurofilamentopathy: dementia with neurofilament inclusions. Neurosci Lett 341:177–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cairns NJ, Uryu K, Bigio EH, Mackenzie IR, Gearing M, Duyckaerts C, Yokoo H, Nakazato Y, Jaros E, Perry RH, Arnold SE, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ (2004) Alpha‐internexin aggregates are abundant in neuronal intermediate filament inclusion disease (NIFID) but rare in other neurodegenerative diseases. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 108:213–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cairns NJ, Zhukareva V, Uryu K, Zhang B, Bigio E, Mackenzie IR, Gearing M, Duyckaerts C, Yokoo H, Nakazato Y, Jaros E, Perry RH, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ (2004) Alpha‐internexin is present in the pathological inclusions of neuronal intermediate filament inclusion disease. Am J Pathol 164:2153–2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Carden MJ, Trojanowski JQ, Schlaepfer WW, Lee VM (1987) Two‐stage expression of neurofilament polypeptides during rat neurogenesis with early establishment of adult phosphorylation patterns. J Neurosci 7:3489–3504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ching GY, Liem RK (1991) Structure of the gene for the neuronal intermediate filament protein alpha‐internexin and functional analysis of its promoter. J Biol Chem 266:19459–19468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ching GY, Liem RK (1993) Assembly of type IV neuronal intermediate filaments in nonneuronal cells in the absence of preexisting cytoplasmic intermediate filaments. J Cell Biol 122:1323–1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Couillard‐Despres S, Zhu Q, Wong PC, Price DL, Cleveland DW, Julien JP (1998) Protective effect of neurofilament heavy gene overexpression in motor neuron disease induced by mutant superoxide dismutase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:9626–9630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. De Jonghe P, Mersivanova I, Nelis E, Del Favero J, Martin JJ, Van Broeckhoven C, Evgrafov O, Timmerman V (2001) Further evidence that neurofilament light chain gene mutations can cause Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth disease type 2E. Ann Neurol 49:245–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. DeKosky ST, Ikonomovic MD (2004) NIFID: a new molecular pathology with a frontotemporal dementia phenotype. Neurology 63:1348–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Duyckaerts C, Mokhtari K, Fontaine B, Hauw J‐J (2003) Maladie de Pick généralisée: une démence mal nommée caractérisée par des inclusions neurofilamentaires. Rev Neurol (Paris) 159:224–224. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Elder GA, Friedrich VL Jr, Pereira, D , Tu PH, Zhang B, Lee VM, Lazzarini RA (1999) Mice with disrupted midsized and heavy neurofilament genes lack axonal neurofilaments but have unaltered numbers of axonal microtubules. J Neurosci Res 57:23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Figlewicz DA, Krizus A, Martinoli MG, Meininger V, Dib M, Rouleau GA, Julien JP (1994) Variants of the heavy neurofilament subunit are associated with the development of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum Mol Genet 3:1757–1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gearing M, Castellano AA, Hunter SB, Brat DJ, Glass JD (2003) Unusual neuropathologic findings in a case of primary lateral sclerosis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 62:555–555. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Georgiou DM, Zidar J, Korosec M, Middleton LT, Kyriakides T, Christodoulou K (2002) A novel NF‐L mutation Pro22Ser is associated with CMT2 in a large Slovenian family. Neurogenetics 4:93–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hirano A, Donnenfeld H, Sasaki S, Nakano I (1984) Fine structural observations of neurofilamentous changes in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 43:461–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jacomy H, Zhu Q, Couillard‐Despres S, Beaulieu JM, Julien JP (1999) Disruption of type IV intermediate filament network in mice lacking the neurofilament medium and heavy subunits. J Neurochem 73:972–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jaros E, Perry RH, Ince P, Lowe J (2000) A new form of dementia: inclusion body cortico‐striatal nigral degeneration. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 26:189–190. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jordanova A, De Jonghe P, Boerkoel CF, Takashima H, De Vriendt E, Ceuterick C, Martin JJ, Butler IJ, Mancias P, Papasozomenos SC, Terespolsky D, Potocki L, Brown CW, Shy M, Rita DA, Tournev I, Kremensky I, Lupski JR, Timmerman V (2003) Mutations in the neurofilament light chain gene (NEFL) cause early onset severe Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth disease. Brain 126:590–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Josephs KA, Holton JL, Rossor MN, Braendgaard H, Ozawa T, Fox NC, Petersen RC, Pearl GS, Ganguly M, Rosa P, Laursen H, Parisi JE, Waldemar G, Quinn NP, Dickson DW, Revesz T (2003) Neurofilament inclusion body disease: a new proteinopathy? Brain 126:2291–2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Josephs KA, Uchikado H, McComb RD, Bashir R, Wszolek Z, Swanson J, Matsumoto J, Shaw G, Dickson DW (2005) Extending the clinicopathological spectrum of neurofilament inclusion disease. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 109(4):427–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Julien JP, Cote F, Beaudet L, Sidky M, Flavell D, Grosveld F, Mushynski W (1988) Sequence and structure of the mouse gene coding for the largest neurofilament subunit. Gene 68:307–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Julien JP, Grosveld F, Yazdanbaksh K, Flavell D, Meijer D, Mushynski W (1987) The structure of a human neurofilament gene (NF‐L): a unique exon‐intron organization in the intermediate filament gene family. Biochim Biophys Acta 909:10–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kaplan MP, Chin SS, Fliegner KH, Liem RK (1990) Alpha‐internexin, a novel neuronal intermediate filament protein, precedes the low molecular weight neurofilament protein (NF‐L) in the developing rat brain. J Neurosci 10:2735–2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kruger R, Fischer C, Schulte T, Strauss KM, Muller T, Woitalla D, Berg D, Hungs M, Gobbele R, Berger K, Epplen JT, Riess O, Schols L (2003) Mutation analysis of the neurofilament M gene in Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci Lett 351:125–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lariviere RC, Julien JP (2004) Functions of intermediate filaments in neuronal development and disease. J Neurobiol 58:131–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lavedan C, Buchholtz S, Nussbaum RL, Albin RL, Polymeropoulos MH (2002) A mutation in the human neurofilament M gene in Parkinson’s disease that suggests a role for the cytoskeleton in neuronal degeneration. Neurosci Lett 322:57–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Levy E, Liem RK, D’Eustachio P, Cowan NJ (1987) Structure and evolutionary origin of the gene encoding mouse NF‐M, the middle‐molecular‐mass neurofilament protein. Eur J Biochem 166:71–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liu Q, Xie F, Siedlak SL, Nunomura A, Honda K, Moreira PI, Zhua X, Smith MA, Perry G (2004) Neurofilament proteins in neurodegenerative diseases. Cell Mol Life Sci 61:3057–3075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mackenzie IR, Feldman H (2004) Neurofilament inclusion body disease with early onset frontotemporal dementia and primary lateral sclerosis. Clin Neuropathol 23:183–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Manetto V, Sternberger NH, Perry G, Sternberger LA, Gambetti P (1988) Phosphorylation of neurofilaments is altered in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 47:642–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mersiyanova IV, Perepelov AV, Polyakov AV, Sitnikov VF, Dadali EL, Oparin RB, Petrin AN, Evgrafov OV (2000) A new variant of Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth disease type 2 is probably the result of a mutation in the neurofilament‐light gene. Am J Hum Genet 67:37–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pachter JS, Liem RK (1985) Alpha‐internexin, a 66‐kD intermediate filament‐binding protein from mammalian central nervous tissues. J Cell Biol 101:1316–1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Shea TB, Beermann ML (1999) Neuronal intermediate filament protein alpha‐internexin facilitates axonal neurite elongation in neuroblastoma cells. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 43:322–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shepherd CE, McCann H, Thiel E, Halliday GM (2002) Neurofilament‐immunoreactive neurons in Alzheimer’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurobiol Dis 9:249–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sternberger NH, Sternberger LA, Ulrich J (1985) Aberrant neurofilament phosphorylation in Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 82:4274–4276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Thompson MA, Ziff EB (1989) Structure of the gene encoding peripherin, an NGF‐regulated neuronal‐specific type III intermediate filament protein. Neuron 2:1043–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tomkins J, Usher P, Slade JY, Ince PG, Curtis A, Bushby K, Shaw PJ (1998) Novel insertion in the KSP region of the neurofilament heavy gene in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Neuroreport 9:3967–3970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Uchikado H, Shaw G, Wang DS, Dickson DW (2005) Screening for neurofilament inclusion disease using alpha‐internexin immunohistochemistry. Neurology 64:1658–1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Xu Z, Cork LC, Griffin JW, Cleveland DW (1993) Increased expression of neurofilament subunit NF‐L produces morphological alterations that resemble the pathology of human motor neuron disease. Cell 73:23–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Yokoo H, Oyama T, Hirato J, Sasaki A, Nakazato Y (1994) A case of Pick’s disease with unusual neuronal inclusions. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 88:267–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yoshihara T, Yamamoto M, Hattori N, Misu K, Mori K, Koike H, Sobue G (2002) Identification of novel sequence variants in the neurofilament‐light gene in a Japanese population: analysis of Charcot‐Marie‐Tooth disease patients and normal individuals. J Peripher Nerv Syst 7:221–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]