Abstract

This article examined the psychometric properties and validity of a new self-report instrument for assessing the social norms that coordinate social relations and define self-worth within three normative systems. A survey that assesses endorsement of honor, face, and dignity norms was evaluated in ethnically diverse adolescent samples in the U.S. (Study 1a) and Canada (Study 2). The internal structure of the survey was consistent with the conceptual framework, but only the honor and face scales were reliable. Honor endorsement was linked to self-reported retaliation, less conciliatory behavior, and high perceived threat. Face endorsement was related to anger suppression, more conciliatory behavior, and, in the U.S., low perceived threat. Study 1b examined identity-relevant emotions and appraisals experienced after retaliation and after calming a victimized peer. Honor norm endorsement predicted pride following revenge, while face endorsement predicted high shame. Adolescents who endorsed honor norms thought that only avenging their peer had been helpful and consistent with the role of good friend, while those who endorsed face norms thought only calming a victimized peer was helpful and indicative of a good friend. Implications for adolescent welfare are discussed.

Keywords: Sociocultural norms, honor, face, dignity, adolescent identity, revenge, reconciliation

Every social group has norms, strategies, and expectations regarding how to deal with the inevitable conflicts that arise between individuals. Recognition that a preponderance of behavioral research has occurred in Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic countries stimulated research comparing East Asian and Western societies, characterized as interdependent and independent cultures (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). Investigations of within-nation variation and other areas in the world have promoted interest in Leung and Cohen’s (2011) tripartite model of cultural prototypes (e.g., Aslani et al., 2013; Severance et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2017). These normative frameworks, described as honor, face (aka humility), and dignity, transcend national, racial, and ethnic groupings (Cross et al., 2013; Oyserman, 2017). Each framework or system gives meaning to social-ecological cues and designates appropriate and inappropriate responses. This evaluative component in turn influences self-worth and motivates compliance with social norms (Yao et al., 2017).

Demands of social living mean that the three systems share basic elements. Within groups, shared social norms provide a framework that (1) promotes social predictability and coordination, (2) prescribes strategies for fostering security and conflict resolution, and (3) imparts a sense of self-worth among group members (Leung & Cohen, 2011). Systems differ in the relative importance given to specific norms, especially during social conflict. Normative systems are maintained across time by parenting practices (Uskul & Over, 2016), and by perceptions of group consensus—whether accurate or not (Vandello et al., 2008).

Historic, ethnographic (see Aslani et al., 2013; Nisbett, 1993), and evolutionary analyses (e.g., Nowak et al., 2016) have ascribed the development of these normative systems to region-specific adaptations to the social and physical ecology. Even when ecological demands shift, social expectations and norms can maintain cultural legacies beyond their adaptive advantage (Vandello et al., 2008). Smaller, homogenous societies may have a pervasive framework that most citizens subscribe to, while larger societies may have regional differences corresponding to ethnic enclaves, ecological niches, and prevailing subsistence strategies (Fiqueredo et al., 2004; Talhelm et al., 2014). The existence of multiple normative systems can provide opportunities for individuals to interact with others who adhere to different social norms, with varying expectations for and interpretations of behavior.

While individuals may prefer a particular system, theoretical analyses posit that living in a multicultural society imparts familiarity with multiple normative frameworks that can be selectively activated according to the eliciting situation (Oyserman, 2017). Given contextual variation and individual differences (Leung & Cohen, 2011), assigning normative orientation based on ethnicity or region markers is inadequate. Accordingly, the goal of the current project was to develop a dimensional measure of honor, face, and dignity endorsement for adolescents. Despite a dearth of research, we cite evidence that these normative systems are relevant to adolescent development and to practical issues that confront youth and educators (see review, Frey et al., in press). We first provide brief descriptions of prototypical honor, face, and dignity systems from the vantage of multiple disciplines (see Aslani et al., 2013; Fischer, 1989; Leung & Cohen, 2011; Woodard, 2011 for extended discussion) and then apply Oyserman’s (2017) model of culture as situated cognition to questions of situational and individual variation.

The Underlying Logic of Honor, Face, and Dignity Systems

Honor

Honor systems are thought to evolve when rule of law is weak, making it incumbent on citizens, primarily men, to provide security for themselves and their families. They do so by establishing a trustworthy reputation and using anger and violence to demonstrate that they cannot be taken advantage of (Aslani et al., 2013; Leung & Cohen, 2011). To enhance security, many honor systems prioritize reciprocating favors (e.g., Cohen et al., 1999; Fischer, 1989; Shafa et al., 2015). Self-worth is based on reputation in a competitive milieu. Personal honor derives from both individual and family actions. Honor is needed to secure support and is critically damaged by failure to punish and avenge insult (Leung & Cohen, 2011). Thus, one must be vigilant for even minor threats to self or closely related others.

Face

Self-worth in a face system is externally determined and predicated on performing social obligations with care and humility (Lee et al., 2014). Prioritizing harmony, humility, and hierarchy, face systems demand a high level of social cooperation, self-restraint, and conformity with tradition (Güngör, et al., 2014). Unlike honor systems, group members are expected to cooperate to protect each other’s reputation and dignity (aka, face). Collective goals of one’s group and family are prioritized over personal goals (Lee et al., 2014), with mandatory social obligations specific to one’s role in a stable hierarchy. In face systems, individuals entrust superiors to punish norm violations, as personal retaliation threatens group functioning.

Dignity

Dignity cultures presume that all persons deserve equal opportunities and share an obligation for fair-dealing. While trust in strangers and out-group members is relatively high, social institutions are expected to step in when trust is violated (Aslani et al., 2013). Thus, a strong rule of law is needed to provide protection and administer justice. Personal acts of retaliation are improper, as they undermine rule of law. Within dignity systems, self-worth rests primarily on intrinsically derived standards. Each person is thought to have an inalienable self-worth that cannot be damaged by the actions of others (Leung & Cohen, 2011). Thus, neither insults nor familial transgressions pose an existential threat. In dignity systems, it is acceptable to prioritize personal goals over those of one’s social group (Lee et al., 2014).

Situational and Individual Variation

Oyserman’s (2017) process-oriented theory views culture as situated cognition in which specific environmental cues elicit corresponding normative behaviors. Experimental studies show that thoughts and behaviors are highly malleable in response to normative cues. Requiring an upright military posture, for example, or showing a violent video (IJzerman & Cohen, 2011; Shafa et al., 2015) can encourage thoughts and behaviors important in honor systems. Such analyses do not negate the existence of regional or group differences in normative predilections, since regions and groups are likely to amplify some cues over others. It simply means that an individual’s habitual use of one normative orientation does not preclude endorsing or acting on alternative norms. It is also possible that those having multiple strong orientations may express norms differently than those who primarily espouse one framework. Seeking to escape the limitations of a strictly categorical approach, the goal of this study is to develop a multi-dimensional measure suitable for adolescents.

Relevance for Adolescent Development and Measurement

The lack of attention to honor, face, and dignity norms during adolescence is surprising. Somech and Elizur (2009) argue that normative systems have their most profound impact as adolescents undertake the task of forming identities. Self-identities provide culturally anchored purpose and meaning to lives, as norms outline how to be a good person. Few studies to date have investigated the tripartite model of social norms in adolescents, and those few have only considered honor norms. In a study using region as a marker of norm endorsement, U.S. students in the so-called honor states were found to be more likely than those from non-honor states to have brought a weapon to school in the past month (Brown, 2016). School shootings were more than twice as likely to occur in honor states after controlling for demographic characteristics, notably in retaliation for threats to social identity. Among Israeli youth, endorsement of honor-related concerns fully mediated the relationships of callousness to conduct problems (Somech & Elizur, 2009) and to suspiciouness and hostility (Somech & Elizur, 2018)—supporting theorized links between honor norms, vigilance for threat, and aggression. Given the failure to explore endorsement of dignity or face systems among adolescents, development of a survey for youth might encourage research into these normative influences.

Only recently have investigators attempted systematic development of scales for all three normative systems (Smith et al., 2017; Yao et al., 2017). Intended for adults and an international business context, many of the items have limited applicability to the concerns of youth. Further, the studies primarily compared East Asian and Middle Eastern samples with European or European-American samples. We endeavored to develop measures of social norms for use with multi-ethnic North American youths. We evaluated the construct validity of the honor, face, and dignity scales with measures of core characteristics associated with each system (e.g., anger restraint, retaliation, conciliation, and threat vigilance).

Preliminary Survey Development

Survey development is an iterative process. Scales for honor, face, and dignity norms were constructed based on prior research (e.g., Leung & Cohen, 2011; Slaby & Guerra, 1988) and initial interviews with nine adolescents of African-, Chinese-, and European-American descent. Interviews explored times youth had reacted to social conflicts with retaliation, emotional restraint, and reconciliation efforts. Interviewees provided explanations for actions, appraisals, and emotions. Vocabulary used by interviewees were incorporated into survey items. A preliminary survey was administered to 54 African-, Asian-, European-, Mexican-, and Native-American youth. The survey items were then revised to improve item clarity and developmental suitability of language. As feared, dignity items overlapped with both the honor and face scales, so new items were written.

Overview of Studies

Our overall goal was to develop 3 scales consisting of 6 items each for honor, face, and dignity norms. The first aim was to test the internal validity and reliability of each scale in a pilot study in the U.S. Pacific Northwest among youth of African, European, Mexican, and Indigenous ancestry (Study 1a). If scale psychometrics were promising, each scale would be revised and be assessed for validity in Canada’s province of British Columbia among youth of East Asian, South Asian, European, and Indigenous/Pacific Islander ancestry (Study 2). The second aim was to examine construct validity in Study 1a and Study 2, using measures theorized to discriminate each system on core behaviors—vengeful and conciliatory responses, restraint of anger, and vigilance for threats.

The samples were chosen to provide a wide range of normative orientations. Our recruitment effort offered an unusual opportunity to examine links between normative orientation and adolescent identity in a diverse U.S. sample. Thus, a final aim was to test the theorized correspondence between norms and behavior and self-concept (Leung & Cohen, 2011; Yao et al., 2017). Specifically, we examined how much youth endorsed honor, face, and dignity norms, and how they evaluated past behavior that exemplified core values such as retaliation for injustice versus emotional restraint (Study 1b).

Study 1a: Assessing Internal and Construct Validity

Study 1a examined the initial factor structure and internal reliabilities of honor, face, and dignity scales in four ethnic groups. Based on prior research and regional markers of norm endorsement (e.g., Cohen et al., 1999), European American and African American samples are likely to include adherents to honor and dignity systems. While Latin America is typically considered to be a region of honor culture, Mexican Americans from farming communities might endorse face norms (Fiqueredo et al., 2004). Finally, we did not know what norms might be applicable to the Native American sample (Frey et al., in press). After examining the factor structure, we then looked at predicted relationships between our scales and criterion surveys, examining the following hypotheses.

Restraint of Anger

Emotions that are culturally congruent are expressed more frequently than incongruent ones (Mesquitia et al., 2017; Tsai, 2007). Consistent with prior research (Boiger et al., 2014; Smith et al., 2016), we predicted that endorsement of face norms would be linked to anger suppression. Honor systems promote strategic expression of anger to reclaim lost honor (Boiger et al., 2014; Smith et al., 2016), which suggests that restraint of anger would be low. Some honor cultures, however, prioritize initial anger suppression and accommodation during early stages of a conflict (Cohen et al., 1999; Shafa et al., 2015). Using nationality as a marker for cultural system, Smith and colleagues (2016) found that anger suppression and expression were positively related in honor nations but negatively related in face nations. Self-expression is important in dignity nations, making anger expression primarily an individual choice. We made no prediction regarding anger suppression for individuals high in endorsement of dignity or honor norms.

Vengeance

We predicted that adolescents who strongly endorse honor norms would report high levels of vengeful thoughts and actions following threats to self. Because honor is predictive of risk-taking on behalf of others (Mandel & Litt, 2012), we also predicted that retaliation on behalf of a close associate would be high with honor endorsement. Endorsement of face or dignity norms was expected to be inversely related to retaliation.

Conciliation

Given the importance of harmonious relations in face systems, we predicted that endorsement of face norms would be linked to high levels of conciliatory thoughts and actions following threats to self or a close associate. Because personal revenge undermines rule of law, dignity endorsement might also predict conciliation. Given strong honor norms for retaliation, we expected honor endorsement to be negatively related to conciliatory thoughts and actions.

Threat Perception

In honor cultures, small threats may be harbingers of larger ones. Thus, vigilance and a tendency to infer hostility can be adaptive. Two types of reactions have been observed in adults. First, if people believe that conflicts may become acrimonious, accommodation may prevent harm (Shafa et al., 2015). Once offense has occurred, immediate retaliation is needed to demonstrate readiness to defend family security. Individuals who engage in high levels of revenge planning after provocation display preattentive vigilance for angry expressions (Crowe & Wilkowski, 2013). Thus, we expected endorsement of honor norms to predict individual differences in perceived discrimination and victimization over and above group differences linked to ethnicity and gender.

Predictions for face and dignity endorsement were less clear. Concern for social reputation might heighten appraisal of threat for those endorsing face norms. Conversely, maintaining face in all parties may necessitate viewing social intentions in the best possible light, and social norms may foster expectations that people will not be intentionally insulting. Both self-report and heart rate data indicate that persons from China, considered a face culture, experienced less threat following social exclusion than those from Germany, considered a dignity culture (Pfundmair et al., 2015). Within the Chinese sample, those who endorsed face norms (e.g., social harmony) coped more effectively with ostracism that those who endorsed dignity norms (e.g., uniqueness). Given these findings, we predicted that face endorsement would have a negative association with threat appraisal and made no predictions for dignity endorsement.

Based on prior research and regional markers of norm endorsement (e.g., Cohen et al., 1999), European American and African American samples are likely to include adherents to honor and dignity systems. While Latin America is typically considered to be a region of honor culture, Mexican Americans from farming communities might endorse face norms (Fiqueredo et al., 2004). Finally, we did not know what norms might be applicable to the Native American sample (Frey et al., in press).

Method

Participants.

We surveyed 267 middle school and high school adolescents (52.7% female; 56.4% high school), with a mean age of 14.95 (standard deviation [SD] =1.75, range 13–18). All were fluent in English. Participants described their ethnic identity as African American (25.5%), European American (22.5%), Mexican American (23.2%), and Native American (28.8%). The latter are Columbian Plateau—a cultural group consisting of a dozen tribes whose homelands extend across three states and two Canadian provinces.

Procedure.

Surveys were individually administered in community centers, libraries, and empty school classrooms by researchers who shared the participant’s ethnicity. As part of a larger study, the experimenter read survey items at a pace calibrated to the participant’s response. Participants were compensated U.S.$5 for completing the survey. To collect data from a sample evenly divided between four ethnic groups, we surveyed and interviewed adolescents in multiple regions of the Pacific Northwest. Communities varied in economic well-being, as indicted by the percentages of students receiving free or reduced-price lunches in schools attended by participants (N = 49, range = 12%–95%, M = 62.2%, median = 71.0%).

In addition to university institutional review, a research permit was obtained from tribal authorities when requested. Youth could pick up parent permission forms at community centers and summer programs. Active consent and participant assent were required.

Measures

Anger suppression.

The Pediatric Anger Expression Scale—Anger In subscale (Jacobs et al., 1989) measures anger suppression with 4 items (I keep my anger to myself. I might feel angry or boil inside, but I hide it. I control my anger by not expressing it. When I’m feeling angry, I make sure not to show it.). Responses ranged from 1 (almost never) to 6 (almost always). A mixed-race sample of young people yielded α = .77 and a 1-year retest r = .44 (Musante et al., 1999).

Retaliation.

Six items examined retaliatory thoughts (e.g., Imagined or wished that the students would get hurt) and actions (Got back at them by yelling, threatening, or insulting them.) following the worst insult or threat to the self that occurred in the last year (Yeager et al., 2011). Responses ranged from 1 (not at all) to 5 (a lot). This scale demonstrates high internal consistency (α = .92) and is related to angry rumination, proactive, and reactive aggression. Items were modified slightly to create a comparable set of 6 items that pertained to the worst insult/threat to “someone you care about.”

Reconciliation.

Using a format similar to the desire for revenge scale, 3 items were created to measure conciliatory thoughts and actions following threat to the self (e.g., Tried to work things out with the students.), and 3 items to measure conciliatory thoughts and actions following threat to a peer “you care about” (e.g., Encouraged forgiveness.). The 5-point scale ranged from 1 (not at all) to 5 (a lot).

Threat perception.

We tested threat perception indirectly by measuring self-reported victimization, victimization of a close other, and ethnic discrimination. We assumed that covariates in our analyses (ethnicity, gender) would account for much of the variance in threat experiences and that norm endorsement would contribute to individual differences above and beyond demographic variation. Two measures used items from the California Victimization Survey (Felix et al., 2011). This is a behavior-based measure with strong test-retest reliability (r = .80-.83), concurrent, and predictive validity. Interviewers described seven examples of victimization events (e.g., Said offensive things or spread hurtful rumors behind my back. Spoke to me in offensive ways in person or online.) and asked participants to enumerate the total number of times that they had been victimized in the past month (range = 0 to 9 or more). Participants also enumerated the total number of times that peers they cared about had been victimized in the past month (e.g., Threatened those I care about with harm. Excluded or ignored those I care about in insulting ways.).

A third measure of threatening events, the Schedule of Racist Events (Landrine & Klonoff, 1996), asked about times participants had experienced ethnic/racial discrimination. We used 11 items selected by Benner and Graham (2013), including harassing events (e.g., How often have the police hassled you because of your race or ethnic background?) and prejudicial expectations (e.g., How often have you run into people who are surprised that you did something really well because of your race or background?). Following past procedure, we asked about discrimination experienced in the past year. Responses ranged from 0 (never) to 3 (often). Prior work with adolescent samples showed good internal reliability and test-retest values ranging from r = .53 to r = .76 (Fisher et al., 2000). Z-scores were calculated for the two victimization and the discrimination measures and combined to form a single score that would be used to estimate threat vigilance after accounting for the contributions of demographic variables.

Social norm orientation.

The 26-item Social Norms Survey was administered last. Participants were asked to respond based on personal beliefs

The next questions are about your beliefs. There are no right or wrong answers. People believe in some of these ideas but not others, but every idea has people who think it is true. Circle the number (ranging from 1 = not true to 6 = true) to show how much each idea is true or not true for you.

The honor scale included items for retaliation, positive reciprocity, and permeable self-family boundaries (e.g., It’s important to punish those who say bad things about your family & friends. You lose honor if you don’t repay people for helping you out). Face scale items assessed self-restraint, humility, and hierarchy concerns (e.g., Even when they do something wrong, you shouldn’t criticize others. You get along with others if you are humble and know your place.). The dignity scale included items assessing institutional justice, independence, and inner conscience (e.g., Punishment of wrongdoers is best left to the authorities. I do what my conscience says is right, even if others don’t agree.). Items reflecting non-retaliatory choices were included with the awareness that they might load on both the face and dignity scales but were included as a key element of face and dignity norms.

Analytic plan.

The rate of missing data on surveys was less than 1.0%. We used multiple imputation with chained equations within the R routine PcAux (Lang et al., 2017) to impute 267 complete data sets. Grand means of imputed values were used in subsequent confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs). Construct fit and loadings were estimated using Mplus 8.3 CFAs (Muthen & Muthen, 2017) in a two-step process. In order to create just-identified measurement structures for each construct, the number of indicators was reduced to three by parceling observed indicators of each construct (Little et al., 2013). Averaging across multiple items enhances the psychometric properties of the data, specifically by increasing the proportion of true-score variance. In order to create parcels, we first ran an item-level CFA to identify item-scale correlations and residuals. Given similar residuals, we would then pair items having higher loadings with those having lower loadings (Little et al., 2013). The resultant scales were examined for group differences in norm endorsement using analyses of variance and then used as predictors in hierarchical multiple regression analyses of survey results.

Results

Item-level analyses showed weak loadings for the positive reciprocity items (see Table 1). They were dropped from the honor scale. Face scale items regarding hierarchy (“You get along with others if you know your place”) and collective goals (“People who fail to consider the wishes of the group are selfish”) were also dropped. Four dignity scale items had weak loadings or were strongly correlated with the face scale. All described low reactivity to threat (“Those who can forget about small insults earn people’s respect;” “Punishment of wrongdoers is best left to authorities;” “You maintain your dignity when you don’t get upset by little insults,” “When people believe in themselves, they don’t need to fight others”). The remaining items, six honor, seven face, and five dignity, were used to create three parcels for each scale (see Table 1 for the contents of each).

Table 1.

Parcel Estimates for Honor, Face, and Dignity Endorsements, U.S. Sample.

| Standardized parcel estimates (Standard errors) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item parcels | Honor | Face | Dignity | |

| 1. | You maintain your dignity if you punish people that double-cross you | |||

| People will take advantage if you don’t show them how tough you are | 0.588 (0.061) | |||

| 2. | Sometimes you have to fight to stop people from taking advantage of you | |||

| You lose respect if you back down from a fight | 0.736 (0.062) | |||

| 3. | Only losers let people say insulting things to them and get away with it | |||

| It’s important to punish those who say bad things about family and friends | 0.620 (0.060) | |||

| 1. | Parents and elders give the best advice about how to get along with others | |||

| I feel proud when I do my duty without calling attention to myself | 0.640 (0.044) | |||

| 2. | It’s everyone’s duty to help people get along with each other | |||

| You maintain your dignity when you do your best in a humble way | 0.879 (0.031) | |||

| 3. | Even when they do something wrong, you shouldn’t criticize others | |||

| I try to avoid conflict even if it means some disappointment | ||||

| Having good relations with others is more important than being right | 0.678 (0.041) | |||

| 1. | You show you have inner strength when you let things go | 0.721 (0.044) | ||

| 2. | I do what my conscience says is right, even if others don’t agree | |||

| Everyone should be treated the same, no matter what their job is or what family they come from | 0.482 (0.059) | |||

| 3. | Outer strength is pretty useless without inner strength and dignity | |||

| I feel proud when I do what is right and ignore what people think of me | 0.601 (0.053) | |||

| Omegas (calculated from unstandardized estimates) | Ω(6 items) = .69 | Ω(7 items) = .79 | Ω(5 items) = .65 | |

| Items discarded due to low estimates or cross-loadings | ||||

| I would go to the ends of the earth to repay an important favor | X | |||

| You lose honor if you don’t repay people for helping you out | X | |||

| I couldn’t feel good about myself if I embarrassed my family | X | |||

| People who fail to consider the wishes of the group are selfish | X | |||

| You get along with others if you are humble and know your place | X | |||

| People who act the toughest are usually the most insecure | X | |||

| Getting back at someone is best left to the authorities | X | |||

| Those who can forget about small insults earn people’s respect | X | |||

| Punishment of wrongdoers is best left to the authorities | X | |||

| When people believe in themselves, they don’t need to fight others | X | |||

| People who get in fights just because someone insulted them look childish | X | |||

| I shrug it off if someone criticizes or insults me in front of others | X | |||

| You maintain your dignity when you don’t get upset by little insults | X | |||

Note. N = 267. Scale = 1 (not true) to 6 (true). Items were intermixed during administration.

Factor loadings for each construct were constrained to average to one to maintain the original scale of the observed indicators (Little et al., 2006). Fit indices were adequate, χ2(24, n = 267) = 62.25, p = .001; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .078, 95% confidence interval (CI) [0.054–0.101]; comparative fit index (CFI) = .937; Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) = .906; standardized root mean residual (SRMR) = .056. Only the honor and face scales showed well-defined specific dimensions with all standardized factor loadings above .500, however. The dignity scale was significantly correlated with the face (r(267) = .519, p < .001) and honor scales (r(267) = .148, p = .02). Face and honor were uncorrelated (r(267) = −.044, ns). Given weak factor loadings for the dignity scale, its marginal omega (as shown in Table 1), and high correlation with the face scale, we proceeded with validity analyses only for the honor and face scales.

Ethnic and gender differences in norm endorsement.

Preliminary analyses of norm endorsement showed no contribution of school level or grade as main effects or moderators (all Fs < 1.67). Nor was age correlated with norm endorsement (rs < .10). Analyses of variance (ANOVAs) therefore proceeded using a 2 (gender) × 4 (ethnicity) design. Endorsement of honor norms varied by gender, F(1, 259) = 5.36, p = .02, η2 = .02), with boys (M = 3.25) more likely to endorse honor norms than girls (M = 2.99). Face norm endorsement varied by ethnicity, F(3, 259) = 3.35, p = .02, η2 = .04, and the gender by ethnicity interaction, F(3, 259) = 2.80, p = .04, η2 = .03. Post hoc t-tests within gender and ethnicity revealed that Mexican American and Native American girls (Ms = 4.99 and 4.83, respectively) were more likely to endorse face norms than European American girls (M = 4.23, ps = .001). Mexican American girls also endorsed face norms more than African American girls (M = 4.50, p = .007) and Mexican American boys (M = 4.52, p = .02).

Convergence with criterion surveys.

Mean scores, SDs, and α levels for surveys used for validation purposes are shown in supplementary materials. All scales showed acceptable internal consistency (α = .74–.88). Norm endorsement for the honor and face scales was used to predict scores on the validity measures. Gender or ethnicity were significantly related to 3 of the 6 scales and included as covariates. Analyses entered dummy variables for ethnicity and gender on the first regression step, and face and honor endorsement on the second step. To check for covariate by norm interactions, honor by gender and ethnicity were entered on the third step, and face by gender and ethnicity on the fourth. We found one significant interaction. Thus, the top spanner of Table 2 provides face and honor coefficients from the interaction model for threat perception. All others results displayed the simple effects models.

Table 2.

Hierarchical Regression Predicting Retaliation, Reconciliation, Anger Suppression, and Threat Vigilance.

| Avenge selfa |

Avenge peera |

Reconcile selfa |

Reconcile peera |

Suppress angerb |

Perceive threatc |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry steps | ΔR2 | B | 95% CI [LL, UL] | ΔR2 | B | 95% CI [LL, UL] | ΔR2 | B | 95% CI [LL, UL] | ΔR2 | B | 95% CI [LL, UL] | ΔR2 | B | 95% CI [LL, UL] | ΔR2 | B | 95% CI [LL, UL] |

| U.S. sample | ||||||||||||||||||

| Covariates | .12 | .04 | .01 | .01 | .03 | .14 | ||||||||||||

| Norms | .06 | .07 | .19 | .17 | .04 | .02 | ||||||||||||

| Honord | 19*** | [0.10, 0.27] | .20*** | [0.11, 0.28] | −.07 | [−0.20, 0.06] | −.14 | [−0.27, 0.00] | .07 | [−0.10, 0.24] | .63 | [−0.48, 1.74] | ||||||

| Faced | −.03 | [−0.12, 0.06] | .03 | [−0.07, 0.12] | .57*** | [0.42, 0.71] | .56*** | [0.40, 0.72] | .32*** | [0.14, 0.51] | −.36* | [−0.69, −0.03] | ||||||

| Covariates by honor | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | .03 | ||||||||||||

| Canadian sample | ||||||||||||||||||

| Covariates | .03 | .01 | .01 | .00 | .01 | .01 | ||||||||||||

| Norms | .26 | .15 | .09 | .07 | .05 | .05 | ||||||||||||

| Honord | .36*** | [0.29, 0.43] | .31*** | [0.23, 0.39] | .08 | [−0.20, 0.05] | .00 | [−0.13, 0.13] | −.21** | [−0.35, −0.06] | .58*** | [0.29, 0.87] | ||||||

| Faced | −.04 | [−0.10, 0.03] | .00 | [−0.07, 0.08] | .29*** | [0.17, 0.40] | .30*** | [0.18, 0.42] | .16* | [0.03, 0.30] | .00 | [−0.26, 0.27] | ||||||

Note. U.S. N = 267; Canadian N = 331. Control variables were ethnicity and gender. Coefficients reflect simple effect models for all analyses except for perceive threat in the U.S. sample, which includes a covariate by honor interaction. None of the analyses revealed a significant covariate by face interaction. CI = confidence interval; LL = lower limit; UL = upper limit. All ΔR2 values for the entry of norms were significant at α < .05 in both samples.

Scale = 1 (not at all) to 5 (did a lot).

Scale = 1 (almost never) to 6 (almost always).

Perceive threat combines standardized items from the California Victimization Survey, Scale 0 = (no events) to 9 (9 or more events/month), and the Schedule of Racist Events, Scale = 0 (no events) to 3 (often).

Scale = 1 (not true) to 6 (true).

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

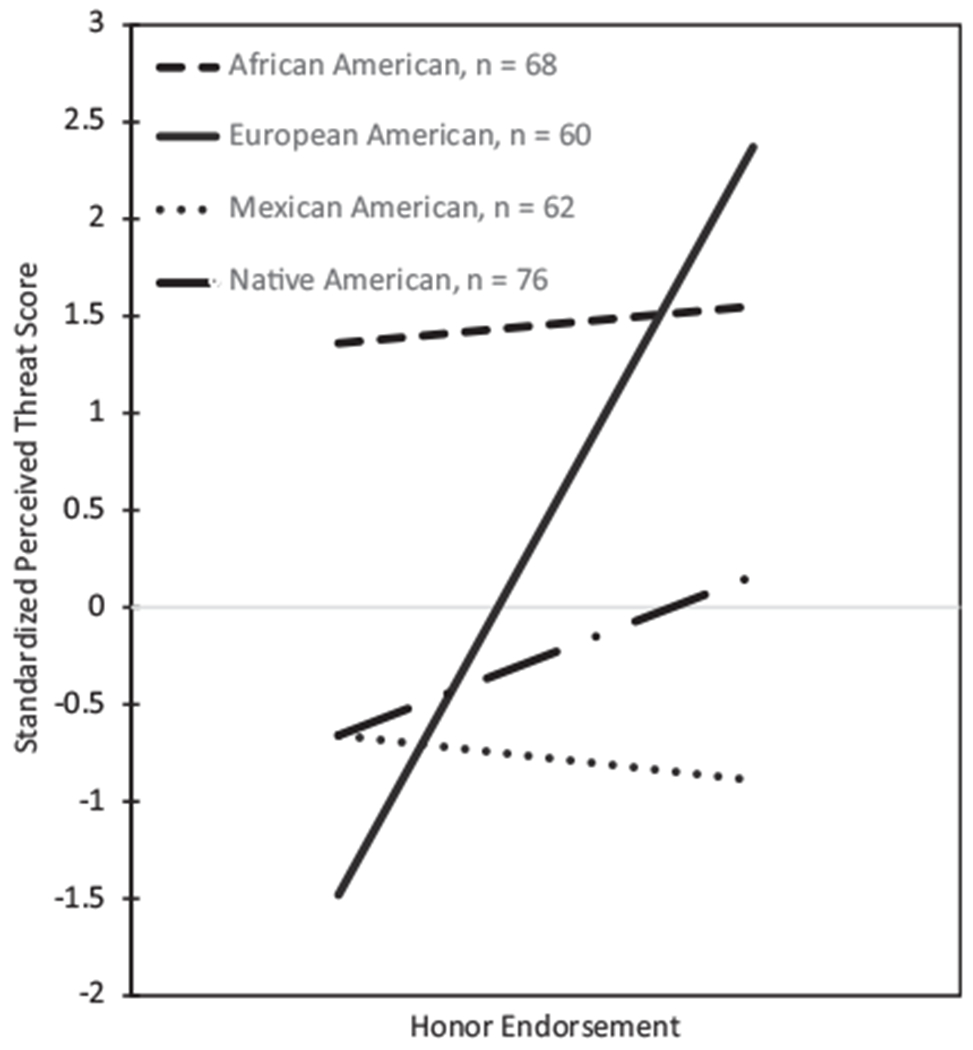

As predicted, honor endorsement was positively related to vengeance over and above the contributions of ethnicity and gender. We found no relationship between honor norms, reconciliation, and anger suppression. Contrary to predictions, honor endorsement did not have a simple relationship to threat perception but was moderated by ethnicity. Regression analyses performed within ethnicity showed that European Americans who strongly endorsed honor perceived high levels of threat in their social relations, unstandardized coefficient, B = 1.11, p < .001,95% CI [0.50, 1.72]. No other ethnicities showed a relationship between honor endorsement and threat perception (Bs > −.12 < .20, ns). As shown in Figure 1, European Americans who did not endorse honor norms perceived low levels of social threat relative to other ethnicities and to European Americans who endorsed honor norms. As predicted, face endorsement was negatively related to perceived threat and positively related to reconciliation and anger suppression. Thus, the criterion measures discriminated between honor and face subscales in theoretically coherent ways.

Figure 1.

Perceived Threat as a Function of Honor Endorsement. Note. N = 267. Range of honor endorsement = 1.00–5.67.

Discussion

This study provided initial evidence that adolescents who profess honor and face norms report levels of anger suppression, retaliation, and reconciliation that are consistent with past adult research (Boiger et al., 2014; Mandel & Litt, 2012; Smith et al., 2016). Gender differences in honor endorsement may reflect the male role in upholding honor through retaliation (Leung & Cohen, 2011). This study also broke new ground by examining normative links to threat vigilance, finding high vigilance limited to honor-endorsing European Americans. The association of face endorsement with low threat vigilance is theoretically interesting and awaits replication. While this study indicated promising results for the development of honor and face scales, efforts to create a valid and reliable dignity scale were unsuccessful. More work is needed to identify items that cohere and do not overlap with the face and honor scales.

Study 1b: Extending Norms Research to Adolescent Self-Concept

Given the link between social norms and adult identity (Leung & Cohen, 2011; Yao et al., 2017), we collected interview data to extend our understanding of how honor and face norms relate to adolescent self-concept. If normative frameworks are motivational systems that designate appropriate and inappropriate behavior, then a motivational driver is the desire to be a good person in the eyes of oneself and others. Actions undertaken in morally relevant situations are considered the most applicable to self-identity (Strohminger et al., 2017). A recursive model suggests that prosocial actions on behalf of victimized peers make important contributions to adolescent socio-moral identities (Frey et al., 2015).

Normative systems also designate appropriate emotional responses to worthy actions (Boiger et al., 2014), particularly with regard to self-evaluative emotions. After rendering assistance to a victimized peer, teens generally report feeling proud (Frey et al., 2020). Pride is appropriate in honor systems (Smith et al., 2016), but inconsistent with the humility expected of persons in face systems (Furukawa et al., 2012). Conversely, unacceptable behavior elicits self-critical emotions of shame and guilt. Shame involves feeling that others would negatively evaluate the self (Tangney et al., 2007). The capacity for shame is an important element of a well-socialized person in both face and honor systems (Boiger et al., 2014). Men in honor systems, for example, may be ashamed if they do not adequately avenge insults (Leung & Cohen, 2011). Conversely, someone operating with strong face norms might experience shame if they fail to support social harmony. Guilt over an action’s negative impact on other people may not vary as much between normative systems. Adolescents in Japan, Korea (face cultures), and the U.S. express high levels of guilt to hypothetical misdeeds (Furukawa et al., 2012).

Study 1b examined youths’ self-evaluation of past actions they had taken after an aggressive provocation to themselves and to close peers. In one condition, they were asked to describe a time when they avenged a peer’s victimization by retaliating on the peer’s behalf. In another, they were asked to describe a time when they avenged themselves after being victimized. Both actions represent appropriate responses for individuals who endorse honor norms. In the third condition, they described a time when they tried to calm the emotions of a victimized peer, a response likely to be endorsed in face systems. Assisting another in restraining anger can reduce loss of face on the part of the victim and the likelihood of retaliation and escalation, thereby promoting social order and harmony.

After participants described each situation, they indicated how strongly they experienced three self-evaluative emotions: shame, guilt, and pride. We also measured whether adolescents viewed actions on behalf of victimized peers as helpful and indicative of their identity as a good person. Loyalty toward close associates is an essential element of honor (Leung & Cohen, 2011), and face systems rely on mutually helpful actions. Judging one’s adequacy as a helpful, good friend requires an individual to compare one’s own behavior with culturally defined social obligations in the important domain of friendship.

Hypotheses

Consistent with theory and past adult research, we predicted that perceived helpfulness, adequacy as a friend, and pride would be elevated following retaliation when participants strongly endorsed honor norms. Although prior work indicates that adolescents generally report moderate levels of shame following retaliation (Frey et al., 2020), we predicted that strong honor endorsers would experience relatively low levels. Given that honor norms identify failure to retaliate as shameful (Leung & Cohen, 2011), strong honor endorsers might experience shame for an action that usually generates pride—calming a victimized peer. At the same time, ratings of helpfulness and friendship might focus on the intent to help, making honor norms less relevant for evaluating one’s adequacy as a friend than when intent to help aligns with norms.

Conversely, we predicted that perceived helpfulness and adequacy as a friend would be higher following attempts to calm a victimized peer when participants endorsed face norms. Although pride might co-vary with feeling helpful and like a good friend, we expected that face norms would encourage a focus on being helpful and the role of friend, rather than on personal pride. Face endorsement was expected to predict shame after revenge—a response proscribed in face cultures. Nevertheless, self-evaluation as a friend following retaliation might reflect both positive intentions to help a peer and the judgment that the action was not especially helpful.

Methods

Participants.

Our sample for interviews (n = 260) was 25.7% African American, 23.1% European American, 23.8% Mexican American, 27.3% Native American, and 52.7% female.

Procedure.

Paid interviewers received a detailed protocol manual and 8 hr of training and supervised practice. Interviewers were carefully trained to follow ethical guidelines regarding participant rights and to consistently follow the scripted protocol.

Using a repeated-measures design, the study examined autobiographical memory with respect to the previous school year. Participants were asked to recall and describe three aggressive events, times when they (1) calmed a victimized peer, (2) retaliated on a victimized peer’s behalf, and (3) retaliated after they had personally been the target of peer aggression (see Frey et al., 2020, for more details). The aggressive events that stimulated participant actions varied in severity, ranging from demeaning comments to physical assault, and often occurred in the context of emotionally arousing sports competitions. If participants provided an example that did not fit the condition, interviewers clarified and gave participants time to search their memories. Participants then indicated how they felt after their action.

Measures of emotion.

Participants indicated the degree to which they experienced 10 emotions following their action. The scale for each emotion ranged from 0% to 100%. The three emotions investigated in this study were “proud or pleased with myself,” “ashamed,” and “guilty,” respectively. The remaining emotions did not pertain to self-evaluation.

Self-evaluative appraisals.

In all three conditions, participants rated how helpful their actions had been using 6-point scales ranging from 1 (not at all) to 6 (a lot!). In the calming and third-party revenge conditions, participants also responded to the question, “Did you feel like you were being a good friend?” using the same scale.

Results

Preliminary repeated measures ANCOVAs were performed using a 3 (condition) × 4 (variable) × 2 (gender) × 4 (ethnicity) repeated measures design with honor and face norms as covariates. Using the Huynh–Feldt correction for violations of sphericity, we found interactions of condition by variable with both honor, F(4.4, 1058.2) = 5.77, p < .001, and face norms, F(4.4, 1058.2) = 2.47, p = .02. Because being a good friend was not included in the personal retaliation condition, we undertook an additional 2 (condition) × 2 (gender) × 4 (ethnicity) repeated measures analysis for honor and face norms. This revealed significant condition by honor, F(1, 250) = 9.30, p = .003, and condition by face, F(1, 250) = 6.23, p = .01, interactions. Neither analysis showed significant main effects or interactions for gender and ethnicity.

We thus proceeded to analyze the contributions of honor and face norms to each self-evaluation variable. Honor and face were entered in a block. Table 3 shows values for total R2, B values, and CIs

Table 3.

Hierarchical Multiple Regression Predicting Evaluative Thoughts and Emotions as a Function of Honor and Face Norm Endorsement in the U.S. Sample.

| Helpfua |

Adequacy as a frienda |

Prideb |

Shameb |

Guiltb |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Norms | ΔR2 | B | 95% CI [LL, UL] | ΔR2 | B | 95% CI [LL, UL] | ΔR2 | B | 95% CI [LL, UL] | ΔR2 | B | 95% CI [LL, UL] | ΔR2 | B | 95% CI [LL, UL] |

| Avenge self | .06*** | NA | .03* | .03** | .02† | ||||||||||

| Honorc | .34** | [0.12, 0.57] | NA | .41* | [0.03, 0.79] | −.18 | [−.42, .05] | −.27* | [−.54, .00] | ||||||

| Facec | −.36** | [−0.62, −0.10] | NA | −.28 | [−0.71, 0.14] | .29* | [.02, .56] | .18 | [−.12, .48] | ||||||

| Avenge peer | .05** | .04** | .02† | .04** | .02 | ||||||||||

| Honorc | .40** | [0.19, 0.60] | .34 ** | [0.14, 0.54] | .35† | [−0.03, 0.73] | −.29** | [−.50, −.08] | −.15 | [−.42, .12] | |||||

| Facec | .04 | [−0.19, 0.28] | −.01 | [−0.24, 0.22] | −.25 | [−0.68, 0.19] | .23† | [−.01, .47] | .24 | [−.07, .55] | |||||

| Calm peer | .06*** | .08*** | .02† | .04** | .02 | ||||||||||

| Honorc | .00 | [−0.13, 0.13] | −.02 | [−0.13, 0.08] | −.41* | [−0.78, −0.05] | .05* | [.00, .09] | .04 | [−.03, .12] | |||||

| Facec | .30** | [16, 0.45] | .30*** | [0.18, 0.42] | .08 | [0.33, 0.50] | −.05* | [−.10, .00] | −.07 | [−.16, .02] | |||||

Note. N = 260. CI = confidence interval.

Scale = 1 (not at all) to 5 (a lot!).

Scale = 0 (0% of experienced emotions) to 10 (100% of experienced emotions).

Scale = 1 (not true) to 6 (true).

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Honor endorsement.

In line with hypotheses, honor endorsement predicted positive self-evaluation after avenging oneself and a peer. Table 3 shows that adolescents who endorsed honor assessed both actions as helpful and experienced pride after avenging the self. The predicted relationship between honor and pride after avenging a peer did not reach significance, p = .07. Honor endorsement predicted reduced guilt after avenging oneself and little shame after avenging a peer. Strong honor endorsers felt shame and little pride after calming a victimized peer. Unlike most youth, they did not view the action as helpful or indicative of a good friend.

Face endorsement.

Conversely, those who strongly endorsed face norms felt like helpful, good friends after calming a peer. As predicted, they felt that avenging themselves was not helpful and experienced shame after taking revenge. Table 3 also shows that calming a peer was inversely related to shame but not related to pride. Nor was face endorsement related to guilt in any condition. Thus, self-evaluative emotions were largely in line with predictions and with youths’ judgments of their adequacy as friends.

Discussion

As predicted by theory (Frey et al., 2015), positive self-appraisal was linked to different behaviors in youth who strongly subscribed to face versus honor norms. Those who endorsed face norms felt they had been a good friend and performed well after calming a victimized peer. Those endorsing honor felt they had been a good friend and had performed well after avenging a victimized peer. Actions inconsistent with norms appeared irrelevant to enacting the friend role. Adolescents did not escape self-criticism, however. Personal vengeance violates social protocol in face cultures and predicted shame whether the object was vengeance for the self or a peer. Youth endorsing honor norms experienced higher levels of shame after calming a friend but reduced self-critical emotions after revenge. Pride was enhanced after those endorsing honor avenged themselves. Consistent with norms for humility (Tsai, 2007), face endorsement was not related to pride, even in the calming condition.

Study 2: Assessing Internal and Construct Validity of the Revised Measure

Results of Study 1 indicated that U.S. adolescents vary in their endorsement of honor and face norms and that personal norms predict actions, thoughts, and emotions in theoretically coherent ways. Results also indicated the need for further measure development. We posited that the relationships between norm endorsement and criterion variables are not limited to U.S. youth. Thus, our second study was conducted in a city in Canada’s British Columbia province (BC), affording us the opportunity to examine normative influences among youth whose ancestry may reflect face (East Asian) and honor systems (South Asian). For construct validation, we used the same set of surveys as those used in Study 1a and expected to replicate converging and diverging relationships in the new sample. For this iteration of the measure, we dropped items that did not load strongly in Study 1 and added new items with the goal creating of three 6-item scales.

Methods

Participants.

There were 307 participants (51.1% female) in grades 9–12 (M = 9.27), with a mean age of 14.8 years (range 13–18). Both university and school district approval were obtained for the research and active parent consent and student assent were required for participation. First Nation Canadians comprised only 1 % of the sample and were combined for analyses with indigenous Pacific Islanders to yield 17.9%. East Asian (primarily Chinese) Canadians comprised 43.6% of the sample; European Canadians, 24.1%; and South Asians, 14.3%. Students attended one of the two public secondary schools. English is the dominant language in southwestern Canada and was the first language of 49.8% of participants.

Measures and procedures.

Any measure is valid only to the extent that it addresses the context in which it is measured. The second iteration was tested in Canada, with a sample that differed in participant ethnicity and conditions of administration (classroom administration). Further, nearly half spoke English as a second language. We agreed to change the wording of 2 items to reflect educators’ views that the original wording was more appropriate in an American, rather than Canadian context. Students also had access to a list of synonyms (developed by their teachers) for words that might be challenging for recent English speakers. We hoped to improve the scales by adding five new items, three for dignity, our weakest scale, two for face, and one for honor norms. The scales for threat vigilance, anger suppression, revenge, and reconciliation were identical to those administered in the U.S. Participants proceeded at their own pace during the group administration.

Results

The rate of missing data was 1.0%. We followed the same analytic plan as Study 1a, imputing 307 complete data sets and using grand means of imputed values for CFAs. The resulting constructs were used to predict scores on criterion scales.

Confirmatory factor analysis.

We again used an item-level CFA to create parcels for a just-identified measurement structure. A new revenge item created for the honor scale, “You should always punish those who betray you” replaced “Sometimes you have to fight to stop people from taking advantage of you” due to stronger loadings. These changes yielded six strong predictors.

Three items did not load highly on the B.C. face scale. One item had shifted wording from duty to responsibility, weakening the social harmony demand. Two related to family hierarchy, “Parents and elders give the best advice on how to get along with others,” and to harmony, “It’s everyone’s duty to help people get along with each other,” may have seemed less useful to a sample with many immigrant youth. One new face item brought the total to four.

An item intended to measure independent standards, “I feel proud when I do what is right and ignore what people think of me,” loaded only weakly on the dignity scale. “Everybody should be treated the same, no matter what their job is or what family they come from” was correlated with the face scale and may have reflected immigrant experience with discrimination. Both items were dropped. Three new dignity items brought the total to six.

Parcels were created by pairing items having higher loadings with those having lower loadings (Little et al., 2013). The resulting parcels and loadings are presented in Table 4. Factor loadings for each construct were constrained to average to one (Little et al., 2006). Fit indices indicated a fairly good fit to the model, χ2(24, n = 307) = 51.040, p = .001; RMSEA = .059, 95% CI [.048–.69]; CFI = .958; TLI = .937; SRMR = .049. All specific dimensions were well-defined with standardized factor loadings above .500. The face and dignity constructs remained significantly correlated (r(329) = .330, p < .001), although less in the U.S. sample. Face and honor were negatively correlated (r(329) = −.259, p < .01), and honor and dignity were not related (r(329) = .014). Omegas calculated with unstandardized loadings and residual variances indicated reliable dimensions for face ω = .782, and honor, ω = .734, but not for dignity, ω = .607. Thus, we proceeded with analyses for the honor and face scales.

Table 4.

Parcel Estimates for Honor, Face, and Dignity Endorsements, Canadian Sample.

| Standardized parcel estimates (Standard errors) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item parcels | Honor | Face | Dignity | |

| 1. | You maintain your dignity if you punish people that double-cross you | |||

| Sometimes you have to fight to stop people from taking advantage of you | 0.570 (0.048) | |||

| 2. | Only losers let people say insulting things to them and get away with it | |||

| You should always punish those that betray you | 0.716 (0.045) | |||

| 3. | You lose respect if you back down from a fight | |||

| It’s important to punish those who say bad things about family and friends | 0.787 (0.045) | |||

| 1. | Even when they do something wrong, you shouldn’t criticize others | 0.796 (0.036) | ||

| 2. | I try to avoid conflict even if it means some disappointment | 0.781 (0.036) | ||

| 3. | Having good relations with others is more important than being right | |||

| It’s not good to criticize others, even if they have done something wrong | 0.567 (0.046) | |||

| 1. | I do what I believe or feel is right, even if others don’t agree | |||

| I feel good about myself when I choose to ignore small insults | 0.555 (0.059) | |||

| 2. | You show you have inner strength when you let things go | 0.645 (0.062) | ||

| It is best to let it go when others criticize you publicly | 0.645 (0.062) | |||

| 3. | Outer strength is pretty useless without inner strength and dignity | |||

| Being strong on the outside means nothing if you do not do what is right | 0.546 (0.062) | |||

| Omegas (calculated from unstandardized estimates) | Ω(6 items) = .73 | Ω(4 items) = .78 | Ω(6 items) = .61 | |

| Items discarded due to low estimates or cross-loadings | ||||

| People will take advantage if you don’t show them how tough you are | X | |||

| You lose honor if you don’t repay people for helping you out | X | |||

| Parents and elders give the best advice about how to get along with others | X | |||

| I feel proud when I do my duty without calling attention to myself | X | |||

| It’s everyone’s responsibility to help people get along with each other | X | |||

| You maintain your dignity when you do your best in a humble way | X | |||

| Everyone should be treated the same, no matter what their job is or what family they come from | X | |||

| I feel proud when I do what is right and ignore what people think of me | X | |||

Note. N = 267. Scale = 1 (not true) to 6 (true). Items were intermixed during administration. Items new to the Canadian survey are underlined, as are wording changes.

Ethnic and gender differences in norm endorsement.

Neither grade nor age were associated with honor or face endorsement (all rs < .012 and >−.031). Group differences in norm endorsement were thus evaluated using 2 (gender) × 4 (ethnicity) ANOVAs. Honor norm endorsement varied by gender, F(1, 323) = 15.24, p < .001, η2 = .045, with a significant gender by ethnicity interaction, F(3, 323) = 2.83, p = .038, η2 = .026. Among boys only, t-tests indicated that South Asian Canadians endorsed honor norms (M = 3.53) at higher levels than European (M = 2.79, p = .004) and East Asian Canadians (M = 3.01, p = .028). Differences between South Asian and Pacific Islander/Indigenous Canadians did not reach significance (M = 3.07, p = .09). Honor endorsement did not differ by ethnicity among girls (M = 2.67). Among South Asian Canadians, boys endorsed honor more than girls (M = 2.57, p < .001). No other ethnicity displayed gender differences, ts < 1. Face endorsement did not vary by ethnicity, F(3, 323) = 1.76, ns, gender, F(1, 323) = 1.28, ns, or the interaction of ethnicity and gender, F < 1.

Convergence with criterion surveys.

Mean scores, SDs, and α levels for the validation surveys are shown in supplementary material. All scales showed acceptable reliability (α = .77–.86). Replicating Study 1a, honor endorsement was significantly related to retaliation (see Table 2). The strong relationship to threat vigilance was not limited by ethnicity, however. Honor was inversely related to anger suppression, unlike Study 1a. Results for face norms replicated the positive relationships to reconciliation and anger suppression and again showed no relation to retaliation. The inverse relationship between face and threat vigilance was not replicated, however. In all, the studies revealed similar, theoretically coherent patterns of behavior and anger expression despite different sample and administration characteristics

General Discussion

Two studies with different ethnicities support the internal and construct validity of measures of honor and face norms. Diverse samples in the northwest U.S. and British Columbia province of Canada indicate that normative orientation contributes to adolescents’ emotional self-restraint (face), perceptions of the environment as threatening (honor), and vengeful (honor) versus conciliatory (face) responses to threat.

Contributions of gender and ethnicity to the criterion variables were small or nonexistent. The notable exception was threat vigilance. While African American youth perceived greater threats from discrimination and victimization than youth of other ethnicities (all ps < 05), their perceptions, like those of Mexican Americans and Native Americans, did not vary as a function of honor endorsement. Only European Americans showed the predicted association: Low endorsers of honor reported low levels of victimization and strong endorsers reported exceptionally high levels. Arguably, expectations expressed in many honor items magnify personal risk. Such expectations may activate biases in perceived threat among European American youth. This is consistent with work documenting how potential loss of privileged status increases perceived threat among some European Americans (Wilkins & Kaiser, 2013), such that they increasingly view themselves as victims of racial discrimination (Norton & Sommers, 2011). It is also possible that vengeful actions encouraged by honor norms contribute to actual victimization levels that are higher (Frey & Higheagle Strong, 2018) than are typical for European Americans (Lai & Ko, 2018), thereby elevating perceptions of relative threat among honor endorsers.

Males of South Asian ancestry showed a greater preference for honor norms, as might be expected from cultural transmission through parents (Aslani et al., 2013; Uskul & Over, 2016). Contrary to predictions, East Asian Canadians showed no preference for face norms. It is possible that many had immigrated from Hong Kong, a British territory until 1997 with a highly competitive finance-based economy. Exposure to western norms and within-group competition may have reduced the utility of a humble self-presentation. Mexican American and Native American girls endorsed face norms at high levels. Perhaps, their social role emphasizes humility and contributing to social harmony more than boys’ roles.

Self-concept.

Study 1b confirmed theoretical predictions that those endorsing face and honor norms would show different patterns of identity-relevant emotions and appraisals after vengeful and conciliatory acts. Although Somech and Elizur (2009) posit that normative systems will be most influential during identity formation, this is the first study to suggest how face and honor norms might contribute to identity. Sociomoral identity—the belief that one is a good person—seems to best reflect what people consider “their true self’ (Strohminger et al., 2017). Normative systems define appropriate ways to enact social roles (e.g., good friend, good parent). When role expectations diverge, the same behavior (e.g., revenge) can elicit different self-appraisals.

Despite contrasting appraisals of revenge and reconciliation, virtually all teens in Study 1b could recall times they had taken revenge or calmed a victimized peer. This indirectly supports Oyserman’s thesis (2017) that situational cues can elicit behavior corresponding to an individual’s nondominant norms. When the heat of the moment had passed, however, self-appraisal may have been based primarily on dominant personal norms.

Limitations and Strengths

A clear strength of this research is the theoretically grounded convergence of actions, appraisals, and emotions with the honor and face scales, demonstrating the potential utility of a measure of social norm endorsement for adolescents. Psychometric analyses indicated limitations, however. First, we failed to identify items that captured all dimensions, such as prosocial elements of honor systems. Second, obtaining clear factors was difficult because constructs in each system overlap with the other systems. Moreover, we expect that youth in multicultural societies will endorse multiple systems—thus our rationale for a multidimensional measure. This poses an additional barrier to finding separate factors. We asked about participant’s personal norms because they appear to be most valid for identifying within-group differences (Heine et al., 2002), but it may be that initial development based on family or group norms would facilitate the identification of a clear measurement structure.

Although methodologies differed—surveys of general dispositions versus interviews about specific actions—all measures in the present study relied on self-report. Thus, convergence may have been enhanced by relying on the same informant. The responses cannot be ascribed to simple self-report bias, however, given that bias would have differed in ways consistent with the two normative systems. That is, youth may have presented themselves as good exemplars of the normative systems they espoused. Future research would do well to examine other informants to see if observed behavior shows similar relationships to norm endorsement.

Implications for Adolescent Welfare

Honor, face, and dignity norms can have long-term significance for health and well-being. Regional differences linked to social norms predict U.S. rates of murder, suicide, and school shootings (Brown, 2016). The current studies with more than eight different ethnicities showed that norms predict revenge, reconciliation, and threat vigilance. Albeit an important strategy for coping with threat, vigilance that is chronic mediates links between discrimination and stress (Himmelstein et al., 2015) and predicts adverse health consequences (Miller et al., 2009). Further, if chronic vigilance promotes retaliation, youth may experience increased victimization (Frey & Higheagle Strong, 2018). Unlike revenge, conciliatory overtures appear to foster positive self-concepts and social connections in most youth (Frey et al., 2020). Thus, it is concerning that honor-endorsing adolescents experienced guilt and shame after conciliatory acts, emotions that may inhibit peaceful responses to conflict.

Given these concerns, it is important to note that honor cultures often have formal and informal avenues for resolving conflicts (Shafa et al., 2015). However, immigrant assimilation and suppression of non-dominant institutions in North America may inhibit utilization of these resources. Further, honor norms evolve in the absence of state protection or justice (Nowak et al., 2016). Institutional violence endured by marginalized communities may encourage adoption of honor norms even when cultural traditions endorse alternative ones. When people are not protected by social institutions, retaliation may support group security—despite inherent risks to individual actors (Frey & Higheagle Strong, 2018). Given the potentially broad impact of social norms on adolescent welfare, further development of the honor, face, and dignity scales is warranted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to acknowledge the hard work and essential insights provided by community members in each location, including Avalon Valencia, Robyn Pebeahsy, Joyce McFarland, Mario Sanchez, Theresa Hardy, Chris Rossman, Ajab Amin, Monette Becenti, June Shirey, among many others.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Study 1 was supported by a grant from the US National Institute of Justice (2015-CK-BX-0022) to the first author.

Footnotes

Authors’ note

Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the US Department of Justice.

Supplemental material

Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Aslani S, Ramirez-Marin J, Brett J, Yao J, Semnani-Azad Z, Zhang Z-X, Tinsley C, Weingart L, & Adair W (2013). Dignity, face and honor cultures: Implications for negotiation and conflict management. In Adair MOW (Ed.), Handbook of research on negotiation (pp. 249–282). Elgar. [Google Scholar]

- Benner AD, & Graham S (2013). The antecedents and consequences of racial/ethnic discrimination during adolescence: Does the source of discrimination matter? Developmental Psychology, 49(8), 1602–1613. 10.1037/a0030557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boiger M, Güngör D, Karasawa M, & Mesquita B (2014). Defending honour, keeping face: Interpersonal affordances of anger and shame in Turkey and Japan. Cognition and Emotion, 28, 1255–1269. https://doi.org/0.1080/02699931.2014.881324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RR (2016). Honor Bound: How a cultural ideal has shaped the American Psyche. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen D, Vandello JA, Puente S, & Rantilla AK (1999). “When you call me that, smile!” How norms for politeness, interaction styles, and aggression work together in southern culture. Social Psychology Quarterly, 62, 257–275. [Google Scholar]

- Cross SE, Uskel AK, Gercek-Swing B, Zeynep S, Alozkan C, Gunsoy C, Ataca B, & Karakitapoğlu-Aygün Z (2013). Cultural prototypes and dimensions of honor. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 40, 232–249. 10.1177/0146167213510323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe SL, & Wilkowski BM (2013). Looking for trouble: Revenge-planning and preattentive vigilance for angry facial expressions. Emotion, 13, 774–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felix ED, Sharkey JD, Green JG, Furlong MJ, & Tanigawa D (2011). Getting precise and pragmatic about the assessment of bullying: The development of the California Bullying Victimization Scale. Aggressive Behavior, 37, 234–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiqueredo AJ, Tal IR, McNeil P, & Guillen A (2004). Farmers, herders and fishers: The ecology of revenge. Evolution and Human Behavior, 25, 336–353. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer DH (1989). Albion’s seed: Four British folkways in America. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher CB, Wallace SA, & Fenton RE (2000). Discrimination distress during adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 29, 679–695. [Google Scholar]

- Frey KS, & Higheagle Strong Z (2018). Aggression predicts changes in peer victimization that vary by form and function. Journal of Abnormal Child Development, 46, 305–318. 10.1007/s10802-017-0306-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey KS, Higheagle Strong Z, Onyewuenyi AC, Pearson CR, & Eagan BR (2020). Third-party intervention in peer victimization: Self-evaluative emotions and appraisals of a diverse adolescent sample. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 1–18. 10.1111/jora.1254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey KS, Onyewuenyi AC, Higheagle Strong Z, & Waller IA (in press). Cultural systems and the development of norms governing revenge and retribution. In Wainryb HRC (Ed.), Retribution and revenge across childhood and adolescence. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frey KS, Pearson CR, & Cohen D (2015). Revenge is seductive if not actually sweet: Why friends matter in bullying prevention efforts. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 37, 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa E, Tangney J, & Higashibara F (2012). Cross-cultural continuities and discontinuities in shame, guilt, and pride: A study of children residing in Japan, Korea and the USA. Self and Identity, 11, 90–113. 10.1080/15298868.2010.512748 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Güngör D, Karasawa M, Boiger M, Dincer D, & Mesquita B (2014). Fitting in or sticking together: The prevalence and adaptivity of conformity, relatedness, and autonomy in Japan and Turkey. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 45, 1374–1389. 10.1177/0022022114542977 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heine SJ, Lehman DR, Peng K, & Greenholtz J (2002). What’s wrong with cross-cultural comparisons of subjective Likert scales? The reference-group effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 903–918. 10.1037//0022-3514.82.6.903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himmelstein MS, Young DM, Sanchez DT, & Jackson JS (2015). Vigilance in the discrimination-stress model for Black Americans. Psychology and Health, 30, 253–267. 10.1080/08870446.2014.966104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ijzerman H, & Cohen D (2011). Grounding cultural syndromes: Body comportment and values in honor and dignity cultures. European Journal of Social Psychology, 41, 456–467. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs GA, Phelps M, & Rohrs B (1989). Assessment of anger expression in children. Personality and Individual Differences, 10, 59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Lai T, & Kao G (2018). Hit, robbed and put down (but not bullied): Underreporting of bullying by minority and male students. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47, 619–635, 10.1007/s10964-017-0748-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrine H, & Klonoff EA (1996). The schedule of racist events: A measure of racial discrimination and its negative physical and mental health consequences. Journal of Black Psychology, 22, 144–168. [Google Scholar]

- Lang KM, Little TD, Chesnut S, Gupta V, Jung B, & Panko P (2017). PcAux: Automatically extract auxiliary features for simple, principled missing data analysis [R Package]. http://github.com/PcAux-Package/PcAux, October 4, 2019.

- Lee HI, Leung AK, & Kim Y-H (2014). Unpacking east-west differences in the extent of self-enhancement from the perspective of face versus dignity culture. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 8, 314–327. 10.1111/spc3.12112 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leung AK, & Cohen D (2011). Within- and between-culture variation: Individual differences and the cultural logics of honor, face, and dignity cultures. Personality Process and Individual Differences, 100, 507–526. 10.1037/a0022151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin A (2013). Classroom code-switching: Three decades of research. Applied Linguistics Review, 4(1), 195–218. [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Rhemtulla M, Gibson K, & Schoemann AM (2013). Why the item versus parcels controversy needn’t be one. Psychological Methods, 18, 285–300. 10.1017/a0033266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Slegers DW, & Card NA (2006). A non-arbitrary method of identifying and scaling latent variables in SEM and MACS models. Structural Equation Modeling, 13, 59–72. [Google Scholar]

- Mandel DR, & Litt A (2012). The ultimate sacrifice: Perceived peer honor predicts troops’ willingness to risk their lives. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 16, 375–388. 10.1177/1368430212461961 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Markus HR, & Kitayama S (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98, 224–253. [Google Scholar]

- Mesquitia B, Boiger M, & De Leersnyder J (2017). Doing emotions: The role of culture in everyday emotions. European Review of Social Psychology, 28, 95–133. 10.1080/10463283.2017.1329107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller G, Chen E, & Cole SW (2009). Health psychology: Developing biologically plausible models linking the social world and physical health. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 501–524. 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musante L, Treiber FA, Davis HC, Waller JL, & Thompson WO (1999). Assessment of self-reported anger expression in youth. Assessment, 6, 225–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (2017). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.). Muthen & Muthen. [Google Scholar]

- Nisbett RE (1993). Violence and U.S. regional culture. American Psychologist, 48, 441–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton MI, & Sommers SR (2011). Whites see racism as a zero-sum game that they are now losing. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6, 215–218. 10.1177/1745691611406922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak A, Gelfand MJ, Borkowski W, Cohen D, & Hernandez I (2016). The evolutionary basis of honor cultures. Psychological Science, 27, 12–24. 10.1177/0956797615602860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman D (2017). Culture three ways: Culture and subcultures within countries. Annual Review of Psychology, 68, 435–463. 10.1146/annurev-psych-122414-033617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfundmair M, Aydin N, Du H, Yeung S, Frey D, & Graupmann V (2015). Exclude me if you can—Cultural effects on the outcomes of social exclusion. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 46, 579–596. 10.1177/0022022115571203 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Severance L, Bui-Wrzosinska L, Gelfand M, Lyons S, Nowak A, Borkowski W, Soomro N, Soomro N, Rafaeli A, Treister DE, Lin C-C, & Yamaguchi S (2013). The psychological nature of aggression across cultures. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34, 835–865. 10.1002/job.1873 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shafa S, Harinck F, Ellemers N, & Beersma B (2015). Regulating honor in the face of insults. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 47, 158–174. 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2015.04.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Slaby RG, & Guerra NG (1988). Cognitive mediators of aggression in adolescent offenders 1. Assessment. Developmental Psychology, 24, 580–588. [Google Scholar]

- Smith PB, Easterbrook MJ, Blount J, Koc Y, Harb C, Torres C, Ahmad AH, Ping H, Celikkol GC, Diaz Loving R, & Rizwan M (2017). Culture as perceived context: An exploration of the distinction between dignity, face and honor cultures. Acta de Investigatión Psicológica, 7, 2568–2576. 10.1016/j.aipprr.2017.03.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PK, Easterbrook MJ, Celikkol GC, Chen SX, Ping H, & Rizwan M (2016). Cultural variations in the relationship between anger coping styles, depression, and life satisfaction. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 47, 441–456. 10.1177/0022022115620488 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Somech LY, & Elizur Y (2009). Adherence to honor code mediates the prediction of adolescent boys’ conduct problems by callousness and socioeconomic status. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 38, 606–618. 10.1080/15374410903103593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somech LY, & Elizur Y (2018). Anxiety/depression and hostility/suspiciousness in adolescent boys: Testing adherence to honor code as mediator of callousness and attachment security. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 22, 89–99. 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2011.00745.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strohminger N, Knobe J, & Newman G (2017). The true self: A psychological concept distinct from the self. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12, 551–560. 10.1177/1745691616689495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talhelm T, Zhang X, Oishi S, Shimin C, Duan D, Lan X, & Kitayama S (2014). Large-scale psychological differences within China explained by rice versus wheat agriculture. Science, 344, 603–608. 10.1126/science.1246850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Stuewig J, & Mashek DJ (2007). Moral emotions and moral behavior. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 345–372. 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai JL (2007). Ideal affect: Cultural causes and behavioral consequences. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 2, 242–259. 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00043.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uskul AK, & Over H (2016). Culture moderates children’s responses to ostracism situations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 110, 710–724. 10.1037/pspi0000050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]