Abstract

Background

An accurate point-of-care test for tuberculosis (TB) in children remains an elusive goal. Recent evaluation of a novel point-of-care urinary lipoarabinomannan test, Fujifilm SILVAMP Tuberculosis Lipoarabinomannan (FujiLAM), in adults living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) showed significantly superior sensitivity than the current Alere Determine Tuberculosis Lipoarabinomannan test (AlereLAM). We therefore compared the accuracy of FujiLAM and AlereLAM in children with suspected TB.

Methods

Children hospitalized with suspected TB in Cape Town, South Africa, were enrolled (consecutive admissions plus enrichment for a group of children living with HIV and with TB), their urine was collected and biobanked, and their sputum was tested with mycobacterial culture and Xpert MTB/RIF or Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra. Biobanked urine was subsequently batch tested with FujiLAM and AlereLAM. Children were categorized as having microbiologically confirmed TB, unconfirmed TB (clinically diagnosed), or unlikely TB.

Results

A total of 204 children were enrolled and had valid results from both index tests, as well as sputum microbiological testing. Compared to a microbiological reference standard, the sensitivity of FujiLAM and AlereLAM was similar (42% and 50%, respectively), but lower than that of Xpert MTB/RIF of sputum (74%). The sensitivity of FujiLAM was higher in children living with HIV (60%) and malnourished children (62%). The specificity of FujiLAM was substantially higher than that of AlereLAM (92% vs 66%, respectively). The specificity of both tests was higher in children 2 years or older (FujiLAM, 96%; AlereLAM, 72%).

Conclusions

The high specificity of FujiLAM suggests utility as a “rule-in” test for children with a high pretest probability of TB, including hospitalized children living with HIV or with malnutrition.

Keywords: tuberculosis, diagnosis, children, lipoarabinomannan, LAM

Fujifilm SILVAMP Tuberculosis Lipoarabinomannan, has high specificity and useful sensitivity for pulmonary tuberculosis, particularly in hospitalized children living with human immunodeficiency virus or malnutrition, and should be considered as a rapid rule-in urine test.

(See the Editorial Commentary by Marais on pages e289–90.)

There have been incremental advances in the microbiological diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB) in children over the past decade. The most important of these has been the development of the molecular diagnostic tests Xpert MTB/RIF [1] and Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra [2] (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA), which rapidly identify Mycobacterium tuberculosis and the presence of resistance to rifampicin. However, implementation in countries with a high burden of tuberculosis (TB) has been constrained by cost, laboratory infrastructure, limited diagnostic sensitivity (62% for sputum samples in a recent meta-analysis [3]) and difficulty obtaining suitable specimens for testing from young children. Similar constraints apply to the diagnosis of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–associated TB in adults; however, recent studies have demonstrated that rapid testing for TB in adults living with advanced HIV using a urine test for Mycobacterium-specific lipoarabinomannan (LAM) reduces mortality [4, 5]. The Alere Determine TB LAM test (AlereLAM, Abbott, Chicago, IL) is a lateral flow test suitable for point-of-care use, and urine is easily obtained from most adults and children.

In adults, AlereLAM has useful sensitivity only in patients living with HIV: specifically, those with advanced HIV infections [6]. Studies of AlereLAM in children living with HIV have shown widely varying accuracy, with sensitivity ranging from 43–65% and specificity from 57–94% [7–9]. The reason for the particularly wide range in specificity is unclear, but may relate to the type of urine sample collected. Fecal contamination of urine collected from a bag may reduce specificity [10], potentially due to cross-reactivity of AlereLAM’s polyclonal antibodies [11].

More recently, Broger and colleagues [12] reported on the accuracy of a novel urine lateral flow LAM test, Fujifilm SILVAMP Tuberculosis Lipoarabinomannan (FujiLAM; Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan), which uses high-affinity monoclonal antibodies and a silver signal–amplification step to achieve increased sensitivity. Amongst adults living with HIV, the sensitivity of FujiLAM was 71%, compared with 35% for AlereLAM, with comparable specificity between tests (91% vs 95%, respectively) [13]. There are no published reports of the accuracy of FujiLAM in children, and we therefore evaluated the accuracy of FujiLAM and AlereLAM using biobanked urine samples from a prospectively enrolled cohort of children presenting to hospital with presumptive PTB in South Africa.

METHODS

The study population was of children (<15 yrs) consecutively enrolled in a study of new TB diagnostics presenting to a children’s hospital, Red Cross Children’s Hospital, Cape Town, South Africa, in whom a diagnosis of PTB was being considered between 1 September 2016 and 17 September 2018. In addition, in order to enrich results for children living with HIV, between 28 August 2012 and 22 September 2016 we consecutively enrolled into the same diagnostic cohort an additional group of 17 children living with HIV in whom urine was available for testing and microbiologically confirmed TB was documented.

Inclusion criteria were a cough of any duration and at least 1 of the following: household contact with an infectious TB source case within the preceding 3 months, loss of weight or failure to gain weight in the preceding 3 months, a positive tuberculin skin test to purified protein derivative (2TU, PPD RT23, Staten Serum Institute, Denmark, Copenhagen; a positive test was defined as ≥10 mm in children living without HIV and ≥5 mm in children living with HIV), or a chest radiograph suggestive of PTB.

Children were excluded if they received more than 72 hours of TB treatment or prophylaxis, if they were not a resident in Cape Town, or if informed consent was not obtained. HIV testing was done in all children unless the HIV status of the child was already known; all children living with HIV also had a CD4 count performed. Written, informed consent for enrolment in the study was obtained from a parent or legal guardian. The Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, approved the study.

At least 1 induced sputum specimen was obtained as previously described [1]. Following decontamination with sodium hydroxide, centrifuged sputum deposits were resuspended in phosphate buffer and used for automated liquid culture (BACTEC Mycobacterial Growth Indicator Tube [BACTEC MGIT], Becton Dickinson, Cockeysville, MD) and Xpert MTB/RIF or Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra testing, as per the manufacturer’s instructions (Ultra was introduced partway through the study). Positive cultures were identified by acid-fast staining, followed by MTBDRplus testing (Hain Lifescience, Nehren, Germany).

Urine was collected at enrolment in urine bags, except in older children who were able to provide a freshly voided specimen. Urine was immediately transferred to an on-site laboratory, where it was frozen at −80oC. Urine was subsequently batch tested with AlereLAM and FuijLAM in parallel, according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with reading by 2 independent laboratory scientists. For FujiLAM, this includes a 5-step procedure taking 50–60 minutes, as has been described previously [12, 14]. Laboratory staff performing urine testing were blinded to each others’ readings and to the clinical details and microbiological results from children. For discordant LAM results between readers, a final interpretation was arrived at after discussion. All LAM tests giving an invalid result were retested once.

Treatment for TB was initiated at the discretion of the treating doctor. Follow-up visits were done at 1, 3, and 6 months for children on TB therapy and at 1 and 3 months for those not treated. Improvement at the 1-month follow-up was defined as weight gain and improvement or resolution of symptoms or signs, compared to the enrolment measurements. Microbiological investigations were not repeated unless a child was deteriorating. TB diagnostic categorization was based on clinical and microbiological investigations, in line with consensus definitions [15]: confirmed TB (any induced sputum culture or Xpert MTB/RIF positive for M. tuberculosis), unlikely TB (TB culture negative, no TB treatment given, and documented improvement of symptoms and signs at a follow-up visit), or unconfirmed TB (all other children).

The sample size was determined by the number of FujiLAM kits available. Only children with a urine sample and at least 1 induced sputum sample were considered for urine LAM testing. Urine from the remaining children was tested; however, results were excluded from the analysis if (1) the child could not be categorized according to TB diagnosis due to loss to follow-up; or (2) either AlereLAM or FujiLAM did not give valid results after repeat testing (we report, however, on the number of invalid results). In addition, since we specifically enrolled children with pulmonary TB, we excluded children with extrapulmonary TB with no evidence of pulmonary involvement from the primary analysis (an analysis including these cases is presented separately).

The accuracy of AlereLAM and FujiLAM was determined by comparison with a microbiological reference standard, as well as a composite reference standard, with 95% confidence intervals, and was computed in STATA version 15.1 using the Wilson method. The microbiological reference standard positive category was made up of cases with confirmed TB. The negative category included those with unconfirmed TB and unlikely TB: in this instance, children with clinically diagnosed TB were allocated to the negative group. The composite reference standard positive category included those with confirmed plus unconfirmed TB; the negative category included those with unlikely TB.

In order to assess whether the method of urine collection may have influenced test accuracy, and since we did not collect data on the collection method, we stratified the analysis by age (<24 months: more likely to have had urine collected in a bag specimen; ≥24 months: more likely to have had spontaneously voided urine collected). Since we included an enriched group of children living with HIV and confirmed TB, the overall proportion of children with confirmed TB is not representative. We therefore calculated predictive values of the index tests, omitting this enriched group of children living with HIV.

World Health Organization 2007 growth standards were used to calculate standardized z scores. Malnutrition was classified as a weight-for-age z-score of less than −2 and stunting was classified as height-for-age z-score of less than −2, calculated for children aged less than 10 years.

RESULTS

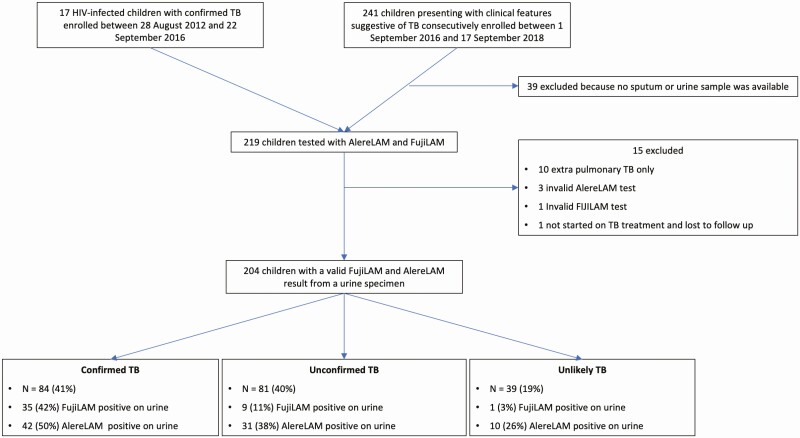

A total of 241 children were enrolled over the study period, with an additional 17 children living with HIV included from the extended period of enrolment, as described above. Results from 204 children were included in the analysis. Reasons for exclusion of children are described in Figure 1. The median age of the 204 children was 45 months (interquartile range, 21–89), 54% were male, 25% were malnourished, and 64% had a positive tuberculin skin test (Table 1). Of the 204 children, 40 (20%) were living with HIV, with a median CD4% of 18 (interquartile range, 9–22) and a CD4 count ≤200 in 9/40 (23%). The majority of children (190/204, 93%) had valid culture results from at least 2 induced sputum samples. Of the 198 children tested with Xpert MTB/RIF or Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra, 17 were tested with Xpert MTB/RIF and 181 with Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra.

Figure 1.

Study flow. Abbreviations: AlereLAM, Alere Determine Tuberculosis Lipoarabinomannan test; FujiLAM, Fujifilm SILVAMP Tuberculosis Lipoarabinomannan; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; TB, tuberculosis.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Children by Tuberculosis Diagnostic Category

| All | Confirmed TB | Unconfirmed TB | Unlikely TB | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 204 | 84 (41) | 81 (40) | 39 (19) | |

| Age, months, median (IQR) | 45.2 (21.2–88.8) |

56.7 (22.9–104.0) |

31.4 (18.4–72.4) |

60.1 (31.1–88.4) |

.058 |

| Age categories | … | … | … | … | .196 |

| <1 yr | 33 (16) | 11 (13) | 16 (20) | 6 (16) | |

| ≥1 yr to <5 yrs | 85 (42) | 33 (39) | 39 (48) | 13 (33) | |

| ≥5 yrs | 86 (42) | 40 (48) | 26 (32) | 20 (51) | |

| Age categories | … | … | … | … | .173 |

| <2 yrs | 59 (29) | 22 (26) | 29 (36) | 8 (21) | |

| ≥2 yrs | 145 (71) | 62 (74) | 52 (64) | 31 (79) | |

| Male sex | 111 (54) | 43 (51) | 43 (53) | 25 (64) | .390 |

| Living with HIV | 40 (20) | 25 (30) | 8 (10) | 7 (18) | .005 |

| CD4 cells/uL median (IQR) | 552 (206–849) | 396 (206–813) | 787 (280–1744) | 815 (121–1031) | .478 |

| CD4% median (IQR) | 18.4 (9.1–22.2) | 17.6 (11.4–27.3) | 13.8 (3.3–20.6) | 20.3 (7.1–22.2) | .467 |

| CD4 count category | … | … | … | … | .875 |

| ≤200 | 9 (22.5) | 5 (20) | 2 (25) | 2 (29) | |

| >200 | 31 (77.5) | 20 (80) | 6 (75) | 5 (71) | |

| Prior TB treatmenta | 20 (10.0) | 7 (9) | 8 (10) | 5 (13) | .773 |

| TST positiveb | 105/165 (64) | 51/66 (77) | 51/64 (80) | 3/35 (9) | <.001 |

| Malnutrition | 44 (25) | 21 (30) | 16 (23) | 7 (20) | .412 |

| Stunted | 73 (40) | 32 (44) | 26 (34) | 15 (44) | .353 |

| FujiLAM positive | 45 (22) | 35 (42) | 9 (11) | 1 (3) | |

| AlereLAM positive | 83 (41) | 42 (50) | 31 (38) | 10 (26) | |

| AlereLAM qualitative | |||||

| 1+ | 74 (89) | 37 (88) | 27 (87) | 10 (100) | |

| 2+ | 4 (5) | 1 (2) | 3 (10) | 0 (0) | |

| 3+ | 3 (4) | 2 (5) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | |

| 4+ | 2 (2) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Malnutrition was defined as a weight-for-age z score <−2; stunting was defined as height-for-age <−2.

Abbreviations: AlereLAM, Alere Determine Tuberculosis Lipoarabinomannan test; FujiLAM, Fujifilm SILVAMP Tuberculosis Lipoarabinomannan; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IQR, interquartile range; TB, tuberculosis; TST, tuberculin skin test.

a3 reported as unknown.

b39 children do not have a result for TST, reasons for not administering a TST include previous TB and tuberculin out of stock.

Of the 204 children with valid FujiLAM and AlereLAM tests, 84 (41%) had confirmed TB, 81 (40%) had unconfirmed TB, and 39 (19%) had unlikely TB. All children with unconfirmed TB received TB treatment. Discordance was reported between the first and second readers in 16 FujiLAM and 32 AlereLAM tests (Supplementary Table 1): all were resolved after consultation. More invalid results were recorded for FujiLAM than AlereLAM (22 vs 7, respectively). All except 4 invalid tests were resolved after repeat testing. The proportion of children with positive results for the 2 urine tests in each of the diagnostic categories is shown in Figure 1.

Using a positive reference standard of confirmed TB and a negative reference standard of all other children (unconfirmed plus unlikely TB), the sensitivity was similar between FujiLAM (42%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 32–52) and AlereLAM (50%; 95% CI, 40–61); however, FujiLAM had substantially higher specificity (92%; 95% CI, 85–95) than AlereLAM (66%; 95% CI, 57–74; Table 2; Figure 2). Using an AlereLAM grade cutoff of 2 (based on the 4-grade reference card) increased specificity to 116/120 (97%; 95% CI, 92–99), but substantially decreased sensitivity to 5/84 (6%; 95% CI, 3–13%). The characteristics of children with positive AlereLAM or FujiLAM tests and with unconfirmed or unlikely TB are shown in Supplementary Table 2.

Table 2.

Accuracy of Lipoarabinomannan Tests

| n | Sensitivity, n test positive/n true positive (%); 95% CI |

Specificity, n test negative/n true negative (%); 95% CI |

PPV, n true positive/n total positive (%); 95% CI |

NPV, n true negative/n total negative (%); 95% CI |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confirmed TB vs unlikely TB | |||||

| FujiLAM | |||||

| All | 123 | 35/84 (41.7); 31.7–52.3 |

38/39 (97.4); 86.8–99.5 |

… | … |

| Excluding enriched HIV+ cohort | 106 | 26/67 (38.8); 28.0–50.8 |

38/39 (97.4); 86.8–99.5 |

26/27 (96.3); 81.7–99.3 |

38/79 (48.1); 37.4–58.9 |

| AlereLAM | |||||

| All | 123 | 42/84 (50.0); 39.5–60.5 |

29/39 (74.4); 58.9–85.4) |

… | … |

| Excluding enriched HIV+ cohort | 106 | 37/67 (55.2); 43.4–66.5 |

29/39 (74.4); 58.9–85.4 |

37/47 (78.7); 65.1–88.0 |

29/59 (49.2); 36.8–61.6 |

| Confirmed TB vs unconfirmed or unlikely TB | |||||

| FujiLAM | |||||

| All | 204 | 35/84 (41.7); 31.7–52.3 |

110/120 (91.7); 85.3–95.4 |

… | … |

| Excluding enriched HIV+ cohort | 187 | 26/67 (38.8); 28.0–50.8 |

110/120 (91.7); 85.3–95.4 |

26/36 (72.2); 56.0–84.2 |

110/151 (72.8); 65.3–79.3 |

| AlereLAM | |||||

| All | 204 | 42/84 (50.0); 39.5–60.5 |

79/120 (65.8); 57.0–73.7 |

… | … |

| Excluding enriched HIV+ cohort | 187 | 37/67 (55.2); 43.4–66.5 |

79/120 (65.8); 57.0–73.7 |

37/78 (47.4); 36.7–58.4 |

79/109 (72.5); 63.4–80.0 |

| Confirmed plus unconfirmed TB vs unlikely TB | |||||

| FujiLAM | |||||

| All | 204 | 44/165 (26.7); 20.5–33.9 |

38/39 (97.4); 86.8–99.5 |

… | … |

| Excluding enriched HIV+ cohort | 187 | 35/148 (23.6); 17.5–31.1 |

38/39 (97.4); 86.8–99.5 |

35/36 (97.2); 85.8–99.5 |

38/151 (25.2); 18.9–32.6 |

| AlereLAM | |||||

| All | 204 | 73/165 (44.2); 36.9–51.9 |

29/39 (74.4); 58.9–85.4 |

… | … |

| Excluding enriched HIV+ cohort | 187 | 68/148 (45.9); 38.1–54.0 |

29/39 (74.4); 58.9–85.4 |

68/78 (87.2); 78.0–92.9 |

29/109 (26.6); 19.2–35.6 |

Data used reference standards of (1) confirmed TB versus unlikely TB; (2) confirmed TB versus children with unconfirmed or unlikely TB; and (3) confirmed plus unconfirmed TB versus unlikely TB.

Abbreviations: AlereLAM, Alere Determine Tuberculosis Lipoarabinomannan test; CI, confidence interval; FujiLAM, Fujifilm SILVAMP Tuberculosis Lipoarabinomannan; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HIV+, living with human immunodeficiency virus; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value; TB, tuberculosis.

Figure 2.

Accuracy of FujiLAM and AlereLAM using a reference standard of confirmed TB versus unconfirmed or unlikely TB in children. Point estimates of sensitivity and specificity are shown together with 95% confidence intervals. Abbreviations: AlereLAM, Alere Determine Tuberculosis Lipoarabinomannan test; FujiLAM, Fujifilm SILVAMP Tuberculosis Lipoarabinomannan; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; TB, tuberculosis.

The sensitivity of Xpert MTB/RIF (or Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra) testing was higher than that of the LAM tests (59/80, 74%; 95% CI, 63–82%). Both LAM assays detected additional culture-confirmed cases that were missed by Xpert MTB/RIF (5 for FujiLAM and 13 for AlereLAM; Figure 3). A combination of FujiLAM + Xpert MTB/RIF had a sensitivity of 64/84 (76%; 95% CI, 66–84), while AlereLAM + Xpert MTB/RIF had a sensitivity of 72/84 (86%; 95% CI, 77–92).

Figure 3.

Venn diagram showing intersection of positive results for lipoarabinomannan tests, Xpert MTB/RIF, and mycobacterial culture. A) The intersection of positive tests amongst 84 children with confirmed TB. B) The intersection of positive tests amongst all children with positive AlereLAM, FujiLAM, microbiological culture, or Xpert MTB/RIF. Abbreviations: AlereLAM, Alere Determine Tuberculosis Lipoarabinomannan test; FujiLAM, Fujifilm SILVAMP Tuberculosis Lipoarabinomannan; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; TB, tuberculosis; Xpert, Xpert MTB/RIF or Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra.

The sensitivity of FujiLAM was higher in children living with HIV (15/25, 60%) than in children living without HIV (20/59, 34%; P = .027) and was higher in malnourished children (13/21, 62%) than in children who were not malnourished (15/48, 31%; P = .017; Table 3). The difference in sensitivity of FujiLAM between children with CD4 counts ≤200 cells/ul (4/5, 80%), compared with children with CD4 counts >200 cells/ul (11/20, 55%) was not significant (P = .307). AlereLAM also showed higher sensitivity in malnourished children (14/21 [67%] vs nonmalnourished 22/48 [46%]; P = .111), but not in children living with HIV (9/25 [36%] vs living without HIV 33/59 [56%]; P = .095). However, the number of samples per subgroup was small, and precision for these stratified estimates is low.

Table 3.

Test Accuracy

| FujiLAM | AlereLAM | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity, n test positive/n true positive (%); 95% CI |

Specificity, n test negative/n true negative (%); 95% CI |

Sensitivity, n test positive/n true positive (%); 95% CI |

Specificity, n test negative/n true negative (%); 95% CI |

|

| By age | ||||

| <24 months old | 9/22 (40.9); 23.3–61.3 |

30/37 (81.1); 65.8–90.5 |

16/22 (72.7); 51.8–86.8 |

19/37 (51.4); 35.9–66.6 |

| ≥24 months | 26/62 (41.9); 30.5–54.3 |

80/83 (96.4); 90.0–98.8 |

26/62 (41.9); 30.5–54.3 |

60/83 (72.3); 61.8–80.8 |

| By HIV infection status | ||||

| Living with HIV | 15/25 (60.0); 40.7–76.6 |

14/15 (93.3); 70.2–98.8 |

9/25 (36.0); 20.2–55.5 |

7/15 (46.7); 24.8–69.9 |

| Living without HIV | 20/59 (33.9); 23.1–46.6 |

96/105 (91.4); 84.5–95.4 |

33/59 (55.9); 43.3–67.8 |

72/105 (68.6); 59.2–76.7 |

| CD4 cells/uL ≥ 200 | 11/20 (55.0); 34.2–74.2 |

11/11 (100); 74.1–100 |

7/20 (35.0); 18.1–56.7 |

6/11 (54.5); 28.0–78.7 |

| CD4 cells/uL < 200 | 4/5 (80.0); 37.6–96.4 |

3/4 (75.0); 30.0–95.4 |

2/5 (40.0); 11.8–76.9 |

1/4 (25.0); 4.6–69.9 |

| By nutritional status | ||||

| Malnourished | 13/21 (61.9); 40.9–79.2 |

22/23 (95.7); 79.0–99.2 |

14/21 (66.7); 45.4–82.8 |

16/23 (69.6); 49.1–84.4 |

| Not malnourished | 15/48 (31.3); 19.9–45.3 |

75/83 (90.4); 82.1–95.0 |

22/48 (45.8); 32.6–59.7 |

52/83 (62.7); 51.9–72.3 |

Data are of FujiLAM and AlereLAM accuracy amongst patient subgroups, comparing children with confirmed TB versus unconfirmed or unlikely TB. Malnourishment was defined as a weight-for-age z score <−2.

Abbreviations: AlereLAM, Alere Determine Tuberculosis Lipoarabinomannan test; CI, confidence interval; FujiLAM, Fujifilm SILVAMP Tuberculosis Lipoarabinomannan; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; TB, tuberculosis.

Both FujiLAM and AlereLAM testing of urine from older children (≥24 months, who were more likely to have produced a spontaneously voided urine sample) showed higher specificity than testing from younger children (FujiLAM, 96% vs 81%, respectively [P = .005]; AlereLAM, 72% vs 51%, respectively [P = .026]). The sensitivity of FujiLAM was unaffected by age (P = .933), while that of AlereLAM was lower amongst children ≥24 months (P = .013; Table 3).

Using the composite reference standard, in which children with either confirmed or unconfirmed TB (all of whom received TB treatment) were classified as positive, the sensitivity of both FujiLAM and AlereLAM was poor (27% [95% CI, 21–34] and 44% [95% CI, 37–52], respectively; Table 2). The specificity of FujiLAM remained higher than that of AlereLAM (97% [95% CI, 87–100] and 74% [95% CI, 59–85], respectively). Excluding the enriched group of children living with HIV with confirmed TB, the positive predictive value of AlereLAM was 87% (95% CI, 78–93), and was higher for FujiLAM (97%; 95% CI, 86–100) due to its higher specificity.

Amongst the 10 children with extrapulmonary TB (6 children with lymph node TB, 1 child with combined lymph node and abdominal TB, and 1 child each having spinal TB, joint TB, or TB otomastoiditis), FujiLAM was negative in all, whilst AlereLAM was positive in 2 (Supplementary Table 3).

Discussion

In this cohort of South African children hospitalized with suspected PTB, FujiLAM and AlereLAM showed modest sensitivity, lower than that of Xpert, for the detection of microbiologically confirmed TB, but FujiLAM showed high specificity. Consistent with findings in adults living with HIV, FujiLAM had higher sensitivity in children living with HIV, and especially in those with severe immunosuppression, while this was not the case for AlereLAM. Both tests had higher sensitivity in malnourished children

The low sensitivity of FujiLAM for microbiologically confirmed TB in children (42%) was similar to that found in studies of adults living with HIV, where sensitivity was modest in those with preserved immunity [12, 13]; however, as with adults, sensitivity was higher in children with HIV infection, particularly those with low CD4 counts. The higher sensitivity in children who are malnourished or living with HIV may reflect a higher bacillary burden or disseminated TB. Although there was a relatively small incremental change in sensitivity from adding FujiLAM to an Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra test of a respiratory sample, the relative utility of these tests may be different in routine care, as urine samples may be more easily obtained from young children than respiratory samples.

Our finding of high specificity and a high positive predictive value of FujiLAM in children is in line with the high analytical specificity observed [11]. This high specificity suggests that there may be a role for FujiLAM as a rule-in test for TB in children. Indeed, given that children tolerate anti-tuberculous therapy well, and that the risk of rapid progression of illness is considered high when the diagnosis of TB is missed, a strong argument may be made for starting TB treatment in a child with a positive FujiLAM result. This is particularly relevant amongst children living with HIV or who are malnourished, who have the highest risks of developing severe TB disease and death. The rapid identification of PTB in these vulnerable groups by FujiLAM may offer potential for timely treatment.

Given that previous comparative studies of FujiLAM and AlereLAM in adults with HIV have shown higher sensitivity for FujiLAM [12, 16], our finding of similar sensitivity for the 2 assays (slightly higher for AlereLAM) was unexpected. However, in this cohort, AlereLAM had very low specificity: 41 of the 120 children in the combined unconfirmed and unlikely TB categories had a positive AlereLAM test, whilst 10 of the 39 children in the unlikely TB group had a positive AlereLAM test. One might expect a similar proportion of nonspecific positive results in the group of children with confirmed TB, which would artificially inflate the sensitivity of AlereLAM. Indeed, among older children in whom the specificity of AlereLAM was higher (72% in children ≥24 months), the sensitivity was correspondingly lower (42%). Use of the more specific 2+ cutoff value for interpreting the AlereLAM test improved specificity substantially, but decreased sensitivity to only 6%.

Our finding of very low specificity of AlereLAM in this study is consistent with our previous study of a different group of children from the same setting [7], but differs from those of several other investigators. A possible reason for this difference is the method of urine collection. In our study, the majority of urine samples were collected from young children in urine bags, which are prone to contamination by stool and skin flora, including nontuberculous mycobacteria and environmental contaminants, which have been shown to give rise to false-positive AlereLAM results [10]. Unfortunately, we did not record the method of collection of samples, and so are unable to compare specificity using different collection methods. However, using age as a proxy for the method of urine collection, we showed higher specificity for both assays in older children, where clean-catch collection was more likely. The importance of clean-catch collection for testing of urine specimens with LAM antigen detection tests should be emphasized in testing protocols.

Another possible explanation for the low specificity of AlereLAM may relate to the insensitivity of the microbiological reference standard comparator. Among children with unconfirmed TB, 38% were positive with AlereLAM (compared to 11% with FujiLAM). It is likely that some of these children did in fact have TB. Since all children in the unconfirmed TB group were placed on TB treatment, it is not possible to assess this accurately. However, the high proportion of positive AlereLAM tests in the unlikely TB group (26%) suggests that these are real false positives. The unlikely TB group represents children who were not placed on TB treatment and had documented clinical improvement at the follow-up visit.

The overall high specificity of FujiLAM, which incorporates highly specific monoclonal antibodies for LAM, is encouraging, and suggests that this assay is more robust to contamination of urine samples [11], which would likely be encountered in program implementation conditions.

The apparent higher sensitivity of AlereLAM in children living without versus with HIV is surprising, given the results of previous studies showing higher sensitivity in adults living with HIV. However, since a substantial proportion of positive AlereLAM results were false positives, and numbers were small in the group living with HIV, this difference may simply be due to chance (P = .095).

Limitations include the relatively small sample size, failure to record the method of urine collection, retrospective LAM testing, specifically recruiting children with pulmonary TB (and not both pulmonary and extrapulmonary TB), and a study design that was specifically enriched for children living with HIV with confirmed TB. We cannot exclude the possibility that prolonged storage may have affected the likelihood of a positive LAM result, although this is unlikely based on recently published data [17].

In conclusion, FujiLAM has moderate sensitivity but high specificity for the diagnosis of TB in children. Testing of urine with FujiLAM should be considered for rapid rule-in diagnoses of TB in children with a high pretest probability of infection, such as hospitalized immunosuppressed or malnourished children. Further, large studies in different settings are needed to obtain more precise estimates of accuracy of FujiLAM, particularly in children who are living with HIV or malnourished. Reactivity to common environmental or commensal contaminants should be taken into consideration during the development of next-generation LAM tests.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors thank the National Health Laboratory Service (NHLS) diagnostic microbiology laboratory at Groote Schuur Hospital; the study, laboratory, and clinical staff at Red Cross Children’s Hospital; the Division of Medical Microbiology; and the children and their caregivers for their contributions.

Disclaimer. The Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics (FIND) is a non-for-profit foundation whose mission is to find diagnostic solutions to overcome diseases of poverty in low- and middle-income countries. It works closely with the private and public sectors and receives funding from some of its industry partners. It has organizational firewalls to protect it against any undue influences in its work or the publication of its findings. All industry partnerships are subject to review by an independent Scientific Advisory Committee or another independent review body, based on due diligence, target product profiles (TPPs), and public sector requirements. FIND catalyzes product development, leads evaluations, takes positions, and accelerates access to tools identified as serving its mission. It provides indirect support to industry (eg, access to open specimen banks, a clinical trial platform, technical support, expertise, and laboratory capacity strengthening in low- and middle-income countries, etc.) to facilitate the development and use of products in these areas. FIND also supports the evaluation of prioritized assays and the early stages of implementation of World Health Organization–approved assays using donor grants. In order to carry out test validations and evaluations, FIND has product evaluation agreements with several private-sector companies for the diseases FIND works in, which strictly define its independence and neutrality vis-a-vis the companies whose products get evaluated, and describes roles and responsibilities.

Financial support. This work was supported by the Regional Prospective Observational Research in Tuberculosis (RePORT TB) Consortium, which is cofunded by the Medical Research Council of South Africa and the US Office of Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health of the US (grant number DAA2–16–62066–1); the Medical Research Council of South Africa for the Tuberculosis Collaborating Centre for Child Health and for the Medical Research Council (MRC) South African Medical Research Council Unit on Child and Adolescent Health; the National Institutes of Health (grant number RO1HD058971); and a Global Health Innovative Technology Fund (grant number G2017–207).

Potential conflicts of interest. M. P. N. is supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Grant (number APP1174455). C. M. D. and T. B. have received funding from the UK Department for International Development (grant number 300341–102), German Federal Ministry of Education and Research through KfW (grant number 2020 62 156), Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs (grant number PDP15CH14). C. M. D. worked for the Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics (FIND) until April 2019. T. B. has patent WO2019186486 pending and worked for FIND until January 2019. S. G. S. and R. S. work for FIND. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Nicol MP, Workman L, Isaacs W, et al. Accuracy of the Xpert MTB/RIF test for the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis in children admitted to hospital in Cape Town, South Africa: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis 2011; 11:819–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nicol MP, Workman L, Prins M, et al. Accuracy of Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra for the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis in Children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2018; 37:e261–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Detjen AK, DiNardo AR, Leyden J, et al. Xpert MTB/RIF assay for the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med 2015; 3:451–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gupta-Wright A, Corbett EL, van Oosterhout JJ, et al. Rapid urine-based screening for tuberculosis in HIV-positive patients admitted to hospital in Africa (STAMP): a pragmatic, multicentre, parallel-group, double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2018; 392:292–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Peter JG, Zijenah LS, Chanda D, et al. Effect on mortality of point-of-care, urine-based lipoarabinomannan testing to guide tuberculosis treatment initiation in HIV-positive hospital inpatients: a pragmatic, parallel-group, multicountry, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016; 387:1187–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lawn SD, Kerkhoff AD, Burton R, et al. Diagnostic accuracy, incremental yield and prognostic value of Determine TB-LAM for routine diagnostic testing for tuberculosis in HIV-infected patients requiring acute hospital admission in South Africa: a prospective cohort. BMC Med 2017; 15:67. doi: 10.1186/s12916-017-0822-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nicol M, Allen V, Workman L, et al. Urine lipoarabinomannan testing for the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis in children – a prospective study. Lancet Global Health 2014; 2:e278–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kroidl I, Clowes P, Reither K, et al. Performance of urine lipoarabinomannan assays for paediatric tuberculosis in Tanzania. Eur Respir J 2015; 46:761–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. LaCourse SM, Pavlinac PB, Cranmer LM, et al. Stool Xpert MTB/RIF and urine lipoarabinomannan for the diagnosis of tuberculosis in hospitalized HIV-infected children. AIDS 2018; 32:69–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kroidl I, Clowes P, Mwakyelu J, et al. Reasons for false-positive lipoarabinomannan ELISA results in a Tanzanian population. Scand J Infect Dis 2014; 46:144–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sigal GB, Pinter A, Lowary TL, et al. A novel sensitive immunoassay targeting the 5-methylthio-d-xylofuranose-lipoarabinomannan epitope meets the WHO’s performance target for tuberculosis diagnosis. J Clin Microbiol 2018; 56:e01338–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Broger T, Sossen B, du Toit E, et al. Novel lipoarabinomannan point-of-care tuberculosis test for people with HIV: a diagnostic accuracy study. Lancet Infect Dis 2019; 19:852–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Broger T, Nicol MP, Székely R, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of a novel tuberculosis point-of-care urine lipoarabinomannan assay for people living with HIV: a meta-analysis of individual in- and outpatient data. PLoS Med 2020; 17:e1003113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aK-QtzkLBug. Accessed 9 March 2020.

- 15. Graham SM, Cuevas LE, Jean-Philippe P, et al. Clinical case definitions for classification of intrathoracic tuberculosis in children: an update. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61(Suppl 3:S179–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bjerrum S, Broger T, Szekely R, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of a novel and rapid lipoarabinomannan test for diagnosing tuberculosis among people with human immunodeficiency virus. Open Forum Infect Dis 2020; 7:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Broger T, Muyoyeta M, Kerkhoff AD, Denkinger CM, Moreau E. Tuberculosis test results using fresh versus biobanked urine samples with FujiLAM. Lancet Infect Dis 2020; 20:22–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.