ABSTRACT

Background

Prebiotic dietary fibers change the intestinal microbiome favorably and provide a health benefit to the host.

Objectives

Polylactose is a novel fiber, synthesized by extrusion of lactose. We evaluated its prebiotic activity by determining its fermentability, effect on the microbiota, and effects on adiposity and liver lipids in a diet-induced obesity animal model.

Methods

Male Wistar rats (4–5 wk old) were fed normal-fat (NF, 25% fat energy) or high-fat (HF, 51% fat energy) diets containing different fibers (6% fiber of interest and 3% cellulose, by weight), including cellulose (NFC and HFC, negative and positive controls, respectively), polylactose (HFPL), lactose matched to residual lactose in the HFPL diet, and 2 established prebiotic fibers: polydextrose (HFPD) and fructooligosaccharide (HFFOS). After 10 wk of feeding, organs were harvested and cecal contents collected.

Results

HFPL animals had greater cecum weight (3 times greater than HFC) and lower cecal pH (∼1 pH unit lower than HFC) than all other groups, suggesting that polylactose is more fermentable than other prebiotic fibers (HFPD, HFFOS; P < 0.05). HFPL animals also had increased taxonomic abundance of the probiotic species Bifidobacterium in the cecum relative to all other groups (P < 0.05). Epididymal fat pad weight was significantly decreased in the HFPL group (29% decrease compared with HFC) compared with all other HF groups (P < 0.05) and did not differ from the NFC group. Liver lipids and cholesterol were reduced in HFPL animals when compared with HFC animals (P < 0.05).

Conclusions

Polylactose is a fermentable fiber that elicits a beneficial change in the gut microbiota as well as reducing adiposity in rats fed HF diets. These effects of polylactose were greater than those of 2 established prebiotics, fructooligosaccharide and polydextrose, suggesting that polylactose is a potent prebiotic.

Keywords: prebiotic, fermentation, fatty liver, liver cholesterol, adiposity, microbiota, rat

Introduction

Obesity continues to be a major public health issue worldwide. The WHO's Health Statistics Report of 2018 estimated that obesity was occurring in 39% of the global population (1). The inflammation and insulin resistance that accompany increased adiposity can lead to many health issues, such as type 2 diabetes (T2D), cardiovascular disease, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). NAFLD is of particular interest, because its incidence has been estimated at 75%–90% in adults who are overweight or obese, occurring in 25% of adults worldwide (2, 3).

NAFLD is defined as the accumulation of excess lipids in the liver (2–4). Simple fatty liver (nonalcoholic fatty liver) is the most common form of NAFLD and occurs with little to no inflammation or scarring. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is the more severe form of NAFLD and occurs with irreversible scarring, or cirrhosis, and fibrosis (2–4). Continued liver lipid accumulation, inflammation, cirrhosis, and fibrosis in NASH lead to chronic liver disease and, eventually, liver failure. Currently, no effective pharmacological treatment exists for NAFLD. However, weight loss, as a result of dietary changes, increased exercise, or bariatric surgery, has been shown to reverse the early stages of NAFLD (2–4). Given the difficulty of achieving weight loss by diet or exercise, and the invasive nature of bariatric surgery, a dietary approach to reverse NAFLD that does not require weight loss would be highly desirable.

Little is known about the molecular mechanisms that lead to NAFLD (5, 6). It is clear that obesity, hypertriglyceridemia, insulin resistance, and T2D are associated with the development of NAFLD (5, 6). A number of factors can result in the accumulation of lipids in the liver, including increased uptake of triacylglycerols from dietary fat and fatty acids from lipolysis of adipose tissue, increased de novo hepatic lipid synthesis, and a reduction in lipid oxidation and mobilization (4, 7, 8). Many of these factors are dysregulated in obesity and hyperinsulinemia. During periods of hyperinsulinemia, many tissues, including the liver, become insulin resistant, leading to hepatic lipid accumulation. This is largely attributable to the upregulation of lipogenic transcription factors, such as sterol regulatory element binding protein-1c (SREBP1c) (4, 7, 8), which results in increased lipid synthesis in the liver. Further, there is a reduction in lipid oxidation and mobilization. With continued lipid accumulation, low-grade inflammation develops that can eventually lead to NASH, fibrosis, and cirrhosis.

Recent studies have shown that there is a relation between the gut microbiota, NAFLD, and obesity (9, 10). Increased large intestinal abundance of the phylum Firmicutes and a reduction in Bacteroidetes [or increased ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes (F:B)] has been correlated with increased adiposity in humans (11, 12) and animals (13), although its usefulness as a biomarker of obesity has been challenged (14). Similarly, human studies have shown correlations between lean subjects and increased abundances of Bifidobacterium (15) and/or Lactobacillus (16, 17). Thus, changes in the abundance of specific taxa of large intestinal bacteria appear to have an important influence on host health.

Increased production of SCFAs may mediate these host health benefits. Large intestinal bacteria ferment dietary fibers and other nondigestible carbohydrates to produce SCFAs, which can be taken up into the circulation and utilized by host tissues (18, 19). SCFA production differs based on the type of carbohydrate presented to the large intestinal microbiome (20) as well as an individual's particular microbiome (21). SCFAs, primarily composed of butyrate, propionate, and acetate, are utilized differently after their absorption in the large intestine. Butyrate is primarily utilized for energy in colonocytes. The remaining SCFAs, including unutilized butyrate, are transported through the portal circulation, with propionate and butyrate taken up by hepatocytes (22), where propionate is used as a gluconeogenic precursor (23, 24). Acetate is primarily taken up by the adipose and skeletal muscle, where it is utilized as a substrate for cholesterol, fatty acid, glutamate, and glutamine synthesis (24, 22). Understanding how a nondigestible carbohydrate changes the microbiome, subsequently affecting SCFA production and altering hepatic lipid metabolism, will likely be important for developing effective dietary approaches to preventing or reversing NAFLD.

Prebiotics are a potential dietary intervention that can alter the gut microbiome by providing a substrate for SCFA production. Prebiotics are defined as indigestible substrates that are fermented in the large intestine, elicit a beneficial change in the gut microbiome, and provide a health benefit to the host (25). The objective of the present study was to investigate the prebiotic potential of a novel dietary fiber, polylactose. Polylactose is produced by polymerizing lactose by reactive extrusion, using heat and citric acid as catalysts (26). Purified polylactose analyzes as a dietary fiber (26). It contains oligomers with a degree of polymerization (DP) of 3–11 monomeric sugars, with the bulk of the oligomers falling in the range of 3–5 DP. Because several established prebiotic dietary fibers are oligomers, we hypothesized that this polylactose preparation might also perform as a prebiotic dietary fiber, as defined above. Therefore, we assessed its fermentability, its effect on the gut microbiota and on cecal SCFA, and whether it produced host health benefits, focusing on its ability to reduce liver lipids and adiposity.

Methods

Preparation of polylactose

Polylactose was produced on a twin-screw extruder as previously described (26, 27). It was subsequently solidified, ground, rehydrated in distilled water, and purified on a mixed-bed carbon and ion exchange column. The filtration column consisted of layers of diatomaceous earth, a 1:1 mixture of Ambersep 200 (H+) and Amberlite FPA 53 (OH−), and activated carbon (Norit GAC 1240 PLUS, Cabot Norit Americas, Inc.). The eluate and 1 L of rinse were collected and pooled before spray drying. This produced a white, almost tasteless, powder. Polylactose fiber, lactose, glucose, and citric acid were measured in the final product using commercial kits (Integrated Total Dietary Fiber Assay Kit, Lactose/Sucrose/D-Glucose Assay Kit, and Citric Acid Assay Kit, respectively; Megazyme). The final product contained ∼50% soluble fiber, 22% free lactose, residual glucose and citric acid, and other unidentified materials.

Animals and treatments

Seventy-two male Wistar rats (initial body weight 75–99 g, 4–5 wk of age) were purchased from Envigo Laboratories. Animals were singly housed in hanging wire cages and kept on a 12-h light/dark cycle. Food and water were provided to the animals ad libitum for the duration of the study. All animal use procedures were approved by the University of Minnesota Animal Care and Use Committee.

All animals were adapted to a purified rodent diet (modified AIN-93G diet) for 2 wk before the start of experimental diets (Supplemental Table 1). At the start of week 3, the animals were randomly assigned into 6 groups (12 rats/group), which were fed 1 of 6 experimental diets for 10 wk. The 6 experimental diets were as follows: normal-fat cellulose (NFC; modified AIN-93G diet), high-fat cellulose (HFC; 9% cellulose), high-fat polylactose (HFPL; 6% polylactose fiber, 3% cellulose), high-fat matched free lactose (HFMFL; 2.6% lactose, matched to the amount of free lactose in the HFPL diet, 6.4% cellulose), high-fat polydextrose (HFPD; 6% PD, 3% cellulose), and high-fat fructooligosaccharide (HFFOS; 6% FOS, 3% cellulose). The prebiotic dose was chosen as one that is potentially attainable in the human diet. Supplemental Table 1 shows the composition of the diets. Food intake and body weight were measured weekly. A 3-d fecal collection was conducted at week 8 of the experimental diets. Feces were lyophilized and stored at −20°C until further analysis.

After 10 wk feeding the experimental diets, food-deprived animals were anesthetized with isoflurane and blood collected by cardiac puncture. Blood was centrifuged at 3000 × g for 20 min at 4°C and plasma aliquots were stored at −80°C until use. Ceca were harvested, cecal pH was measured with a spear-tip electrode, and contents were expressed into sterile 15-mL conical tubes, frozen on dry ice, and stored at −80°C. Empty ceca were rinsed, weighed, and discarded. One epididymal fat pad from each animal was harvested, rinsed, weighed, frozen on dry ice, and stored at −80°C. Livers were excised, rinsed, weighed, frozen on dry ice, and stored at −80°C until further analysis.

Blood glucose control and gluconeogenesis potential

Tolerance testing was performed during the final 2 wk of feeding the experimental diets after overnight (8-h) deprivation of food. Insulin-tolerance tests (ITTs; 1 IU insulin/kg body weight) and pyruvate-tolerance tests (60 mg sodium pyruvate/kg body weight) were conducted during week 9, with each being administered intraperitoneally. Oral-glucose-tolerance tests (OGTTs) (0.5 g glucose/kg body weight) were conducted during week 10. For all tolerance testing, blood glucose was measured using blood glucose test strips and a glucometer (AlphaTrak, Zoetis Inc.) at 0, 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min. AUCs were calculated using the trapezoidal method.

Liver lipids and cholesterol

Approximately 1 g of liver from each animal was homogenized and lipids were extracted using chloroform:methanol (2:1) (28). Extracted lipids were dried under N2 gas and quantified gravimetrically. Lipid samples were reconstituted with 10 mL chloroform:methanol (2:1) and cholesterol was measured enzymatically using a previously described method (29).

Circulating adipokines and lipids.

Circulating leptin and adiponectin were quantified by ELISA (Millipore Sigma EZRL-83K and abcam ab10874, respectively) using plasma samples from the time of harvest. Plasma triacylglycerols were measured spectrophotometrically using a commercial kit (T7532120, Pointe Scientific Inc.).

Microbiome sequencing

Cecal contents were thawed on ice and mixed before use. DNA was extracted from ∼180–220 mg of contents using the Qiagen Stool Extraction kit and DNA eluates were quantified spectrophotometrically. DNA eluates were then submitted to the University of Minnesota Genomics Center for sequencing of the 16S ribosomal subunit with the V5/V6 region amplicon on an Illumina MiSeq using 2 × 300-bp paired end reads. Data were analyzed using DADA2 and phyloSeq in R (The R Foundation).

SCFAs and bile acids

SCFAs were extracted from cecal contents and measured by GC (30–32). Bile acids were extracted from fecal samples, partially purified (33), and total bile acids quantified enzymatically (34).

Statistical analysis

All data except microbiota data were analyzed by 1-factor ANOVA followed by Duncan's multiple range test using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute). Homogeneity of variances was assessed using Levene's test. Any variable with unequal variances between the groups was log transformed before statistical analysis. Duncan's multiple range test was used to conduct pairwise comparisons among all groups, reducing the chance of making type II errors. To examine for trends in differences, Student's t tests were used to compare groups of interest. Pearson correlation analyses were conducted in SAS for SCFAs and adiposity measures. AUC was calculated in R and analyzed by ANOVA and Student's t test in SAS. Microbiota data were analyzed in R (35), using the DADA2 and phyloseq packages for β-diversity, taxonomic abundance, and statistical analyses.

Results

Polylactose reduced adiposity with no significant changes in energy intake or body weight

Daily mean energy intake was significantly greater in HFC than in HFPL (P < 0.05). However, the energy intakes for NFC, HFMFL, HFPD, and HFFOS did not differ from either HFC or HFPL (Table 1). Final body weights did not differ between the groups (P = 0.31). The epididymal fat pads of HFPL and NFC weighed less than those of HFC (P = 0.034) (Table 1). Further, epididymal fat pad weight of HFPL was significantly less than those of HFMFL, HFPD, and HFFOS (P < 0.05). Plasma leptin concentration in HFPL and NFC was less than in HFMFL. Plasma leptin concentration, which has been shown to correlate with total body fat (36, 37), was highly correlated with epididymal fat pad weight (r = 0.69, P < 0.0001). Plasma adiponectin concentration did not differ between the groups (P = 0.88).

TABLE 1.

Energy intake, final body weight, cecal pH, and tissue weights in rats fed normal-fat diet or high-fat diet alone or with matched free lactose, polylactose, polydextrose, or fructooligosaccharide for 10 wk1

| Variable | NFC | HFC | HFPL | HFMFL | HFPD | HFFOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy intake, kJ/d | 377.4 ± 14.3ab | 410.1 ± 12.9a | 363.7 ± 15.9b | 371.6 ± 12.8ab | 382.2 ± 13.7ab | 385.6 ± 14.0ab |

| Initial body weight, g | 197.4 ± 3.9 | 196.2 ± 3.9 | 192.4 ± 3.6 | 189.7 ± 3.9 | 188.8 ± 5.0 | 195.5 ± 5.6 |

| Final body weight, g | 490.0 ± 11.8 | 534.8 ± 14.8 | 496.5 ± 12.5 | 517.8 ± 17.5 | 514.9 ± 19.6 | 523.0 ± 13.4 |

| Empty cecum weight, g/100 g FBW | 0.119 ± 0.003c | 0.109 ± 0.007c | 0.324 ± 0.022a | 0.104 ± 0.004c | 0.156 ± 0.008b | 0.152 ± 0.009b |

| Cecal pH | 6.91 ± 0.66a | 6.98 ± 0.06a | 6.05 ± 0.08c | 6.86 ± 0.06a | 6.54 ± 0.08b | 6.98 ± 0.06a |

| Epididymal fat pad weight, g/100 g FBW | 1.076 ± 0.068bc | 1.322 ± 0.064a | 0.943 ± 0.055c | 1.335 ± 0.098a | 1.301 ± 0.081a | 1.220 ± 0.072ab |

| Liver weight, g/100 g FBW | 3.060 ± 0.119c | 3.447 ± 0.162ab | 3.195 ± 0.104bc | 3.350 ± 0.108abc | 3.126 ± 0.082bc | 3.541 ± 0.079a |

1 n = 12. Values are means ± SEMs. Means within a row without a common letter are statistically different, P < 0.05. FBW, final body weight; HFC, high-fat cellulose; HFFOS, high-fat fructooligosaccharide; HFMFL, high-fat matched free lactose; HFPD, high-fat polydextrose; HFPL, high-fat polylactose; NFC, normal-fat cellulose.

Polylactose was vigorously fermented in the large intestine

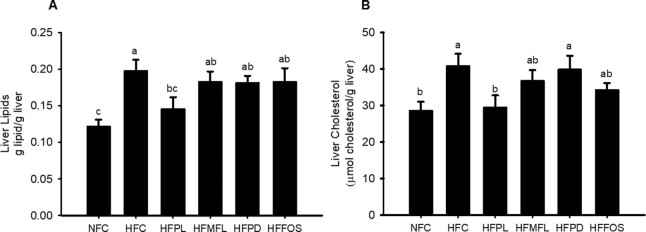

Most fermentation by the gut microbiota in the rat occurs in the first part of the large intestine, the cecum. Fermentation lowers the pH of the cecal contents and increases the mass of the cecal tissue (38). Cecal pH was lower in HFPL and HFPD than in all other groups, but pH was lower in HFPL than in HFPD (P < 0.0001) (Table 1). Empty cecum weight was dramatically greater in HFPL than in all other groups (P < 0.0001). HFPD and HFFOS also had a significantly greater empty cecum weight than HFC and NFC. Total cecal SCFA content was increased in HFPL compared with all other groups (P < 0.0001). This was due to greater amounts of acetate and propionate in the cecal contents of HFPL than in all other groups (P < 0.0001) (Figure 1). Total butyrate content in the cecal contents did not differ between the groups. Total cecal contents SCFA was strongly correlated with empty cecal weight (r2 = 0.788, P < 0.0001, for all animals). Total cecal acetate and propionate were also individually highly correlated with empty cecum weight (r2 = 0.792 and 0.811, respectively, P < 0.0001), whereas total cecal contents butyrate showed no correlation to empty cecum weight (r2 = −0.105, P = 0.40). Epididymal fat pad weight did not correlate with total cecal contents SCFA (r = −0.17, P = 0.18) nor with any individual SCFA (r = −0.18, P = 0.13 for acetate; r = −0.21, P = 0.09 for propionate; r = 0.13, P = 0.29 for butyrate). Likewise, plasma leptin concentration did not correlate with total cecal contents SCFA (r = −0.008, P = 0.95) nor with any individual SCFA (r = −0.02, P = 0.87 for acetate; r = −0.004, P = 0.97 for propionate; r = −0.02, P = 0.90 for butyrate).

FIGURE 1.

Content of individual SCFAs in cecal contents in rats fed normal-fat diet or high-fat diet alone or with matched free lactose, polylactose, polydextrose, or fructooligosaccharide for 10 wk. Values represent mean ± SEM, n = 12. Labeled means without a common letter are significantly different, P < 0.05. HFC, high-fat cellulose; HFFOS, high-fat fructooligosaccharide; HFMFL, high-fat matched free lactose; HFPD, high-fat polydextrose; HFPL, high-fat polylactose; NFC, normal-fat cellulose.

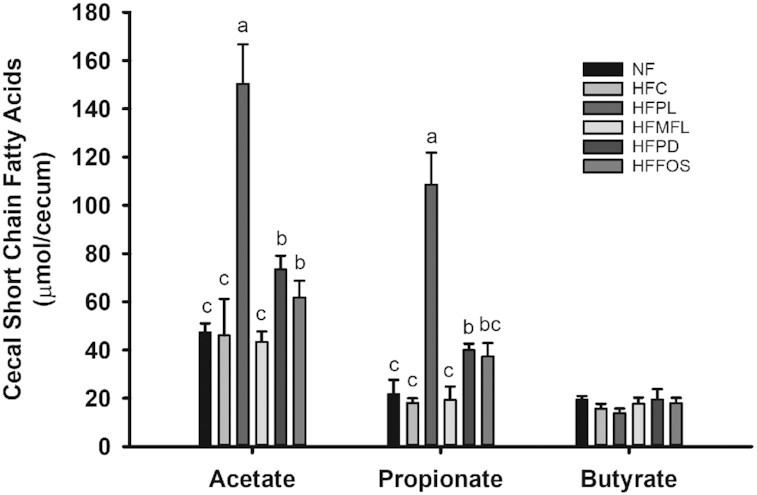

Polylactose reduced fatty liver

Liver weights were greater in HFC and HFFOS than in NFC (P < 0.05) (Table 1). HFPL had less liver lipids than HFC (P = 0.0035) and trended less than HFMFL (P = 0.075), HFPD (P = 0.075), and HFFOS (P = 0.087) (Figure 2A). Liver cholesterol was also decreased in HFPL compared with HFC (P = 0.0028) and was similar to NFC (Figure 2B). Plasma triacylglycerol concentration was lower in all high-fat (HF) diet groups than in NFC (P < 0.0001) (Table 2). Among the HF diet groups, plasma triacylglycerol concentration was lower in HFFOS than in HFC (P < 0.0001). Daily fecal total bile acid excretion was not different between the HF-fed groups, but excretion was less in HFMFL and HFPD than in NFC (P = 0.016 and P = 0.004, respectively) (Table 2).

FIGURE 2.

Liver lipids (A) and liver cholesterol (B) in rats fed normal-fat diet or high-fat diet alone or with matched free lactose, polylactose, polydextrose, or fructooligosaccharide for 10 wk. Values represent mean ± SEM, n = 12. Labeled means without a common letter are significantly different, P < 0.05. HFC, high-fat cellulose; HFFOS, high-fat fructooligosaccharide; HFMFL, high-fat matched free lactose; HFPD, high-fat polydextrose; HFPL, high-fat polylactose; NFC, normal-fat cellulose.

TABLE 2.

Plasma glucose, hormone, and triacylglycerol concentrations, cecal total SCFA content, and fecal bile acid excretion in rats fed normal-fat diet or high-fat diet alone or with matched free lactose, polylactose, polydextrose, or fructooligosaccharide for 10 wk1

| Variable | NFC | HFC | HFPL | HFMFL | HFPD | HFFOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fasting plasma glucose, mg/dL | 115 ± 4.2 | 116 ± 5.0 | 115 ± 7.3 | 118 ± 4.0 | 125 ± 4.2 | 128 ± 3.8 |

| Fasting plasma insulin, ng/mL | 4.99 ± 0.57b | 6.44 ± 0.64ab | 6.58 ± 1.12ab | 7.03 ± 0.67ab | 8.45 ± 1.17a | 5.62 ± 0.50b |

| Plasma leptin, ng/mL | 9.18 ± 1.26b | 16.8 ± 1.94a | 12.7 ± 1.92ab | 20.5 ± 3.13a | 15.1 ± 2.34ab | 14.2 ± 1.97ab |

| Plasma adiponectin, µg/mL | 19.4 ± 3.56 | 23.4 ± 3.52 | 23.3 ± 3.39 | 25.2 ± 3.85 | 20.0 ± 3.47 | 22.4 ± 3.68 |

| Plasma triacylglycerols, mmol/L | 1.77 ± 0.14a | 1.24 ± 0.12b | 0.91 ± 0.14bc | 1.02 ± 0.09bc | 1.01 ± 0.09bc | 0.87 ± 0.09c |

| Total SCFAs, µmol/cecum | 95.3 ± 5.7c | 89.4 ± 8.6c | 286 ± 30.7a | 88.5 ± 9.3c | 149 ± 12.4b | 131 ± 16.6bc |

| Fecal bile acid excretion, µmol/d | 39.1 ± 2.5a | 32.6 ± 3.0ab | 26.6 ± 4.3ab | 27.1 ± 1.9b | 24.6 ± 2.3b | 33.4 ± 2.4ab |

1 n = 12, except fecal bile acid excretion, where n = 7–12. Values are means ± SEMs. Means within a row without a common letter are statistically different, P < 0.05. HFC, high-fat cellulose; HFFOS, high-fat fructooligosaccharide; HFMFL, high-fat matched free lactose; HFPD, high-fat polydextrose; HFPL, high-fat polylactose; NFC, normal-fat cellulose.

Polylactose-fed animals trended toward improved glycemic control

There were no significant differences between the groups in fasting plasma glucose (Table 2). Fasting plasma insulin trended toward being greater in HFC than in NFC (P = 0.0755). Plasma insulin was significantly greater in HFPD than in HFFOS and NFC, but HFC, HFPL, and HFMFL did not differ from HFPD or HFFOS (P < 0.05). The ITT showed no differences in insulin sensitivity, as measured by the glucose response (P = 0.9431, data not shown). However, HFPL showed a trend toward a smaller AUC for the OGTT than HFC (P = 0.056) when compared by Student's t test (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

OGTT in rats fed normal-fat diet or high-fat diet alone or with matched free lactose, polylactose, polydextrose, or fructooligosaccharide for 10 wk. (A) Mean OGTT curve by diet group. (B) AUC for the OGTT. Values represent mean ± SEM, n = 12. Labeled means without a common letter are significantly different, P < 0.05. *HFC compared with HFPL, P = 0.056 by Student's t test. HFC, high-fat cellulose; HFFOS, high-fat fructooligosaccharide; HFMFL, high-fat matched free lactose; HFPD, high-fat polydextrose; HFPL, high-fat polylactose; NFC, normal-fat cellulose; OGTT, oral-glucose-tolerance test.

Polylactose elicited a beneficial change in the gut microbiota

β-Diversity analysis of the gut microbiota revealed 3 distinct clusters: control groups (NFC, HFC, and HFMFL), commercial prebiotics (HFPD, HFFOS), and polylactose (HFPL). The HFPL cluster was most dissimilar from the control groups and in line with, yet separated from, the prebiotic cluster. This indicates greater change in the gut microbiota when compared with the prebiotic groups, as was shown by the Bray–Curtis dissimilarity measure of β-diversity as visualized in Figure 4. Statistical analysis of the Bray–Curtis dissimilarity matrix revealed that 33% of the microbial variation between animals was due to diet (R2 = 0.33, P < 0.001). Taxonomic analysis (Figure 5) revealed that HFPL contained greater Bifidobacterium species and Gammaproteobacteria than all other HF groups (P < 0.0001). Lactobacillus species were also increased in HFPL compared with HFC (P < 0.04). Akkermansia muciniphila was increased in HFPL when compared with all other HF groups (P < 0.0001), and increased in HFFOS when compared with the control groups (NFC, HFC, and HFMFL; P < 0.0001). Lastly, F:B was reduced in HFPL compared with all other groups (P < 0.0001) (Figure 5). F:B correlated significantly but inversely with cecal total SCFA content (r = −0.377, P = 0.0021) and with cecal acetate and propionate content (r = −0.399, P = 0.0012 and r = −0.383, P = 0.0018, respectively) but not with cecal butyrate content (r = 0.176, P = 0.164).

FIGURE 4.

Bray–Curtis PCoA for β-diversity of bacteria in cecal contents of rats fed normal-fat diet or high-fat diet alone or with matched free lactose, polylactose, polydextrose, or fructooligosaccharide for 10 wk. Each point represents an individual animal, coded by diet. There is a statistically significant difference between the diet groups, by analysis of dissimilarities (adonis) (R2 = 0.33, P < 0.001). HFC, high-fat cellulose; HFFOS, high-fat fructooligosaccharide; HFMFL, high-fat matched free lactose; HFPD, high-fat polydextrose; HFPL, high-fat polylactose; NFC, normal-fat cellulose; PCoA, principal coordinate analysis.

Figure 5.

Select taxonomy in cecal contents of rats fed NF diet or HF diet alone or with MFL, PL, PD, or FOS for 10 wk. (A) Bifidobacterium (genus), (B) Lactobacillus (genus), (C) Gammaproteobacteria (class), (D) Akkermansia muciniphila, (E) Firmicutes:Bacteroidetes ratio (phyla). Abundance represented as percent (proportion of taxa sequence reads/total reads per sample). Values represent mean ± SEM, n = 11–12. Labeled means without a common letter are significantly different, P < 0.05. NFC, normal fat cellulose control; HFC, high fat cellulose control; HFPL, high fat polylactose; HFMFL, high fat matched free lactose; HFPD, high fat polydextrose; HFFOS, high fat fructooligosaccharide.

Discussion

Here we present the first study, to our knowledge, of the prebiotic activity of polylactose. Prebiotic dietary fibers are fibers that produce beneficial changes in the gut microbiota and that provide a health benefit to the host (39). Polylactose, a novel, synthetic dietary fiber, fulfills the criteria for a prebiotic, in that it elicited a beneficial change in the gut microbiota in a diet-induced obesity animal model and provided several health benefits, specifically reducing adiposity and fatty liver, and trending toward improvement of glycemic control. In contrast, PD- and FOS-fed animals, who presented only a modest change in the microbiota, showed no change in adiposity, liver lipids, or improvement in glycemic control at the dietary concentration of 6% used in the present study (P > 0.05).

Feeding studies of PD and FOS have shown a change in the gut microbiota (40–42) or greater fermentation in the cecum (40, 43). This is consistent with our findings that both PD and FOS were fermented, as indicated by a reduction in cecal pH, an increase in empty cecum weight, and a change in the gut microbiota. However, these differences occurred to a much lesser degree than with polylactose. This suggests that polylactose is a better substrate for certain taxa in the gut, such as Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus species, leading to greater fermentation. This is further corroborated by the greater content of total and individual SCFAs in the cecal contents of polylactose-fed animals, specifically an increase in acetate and propionate, than in the PD and FOS groups. Other studies have shown a similar increase in total SCFAs and propionate with PD and FOS feeding compared with an HFC control group (43, 44). An HF diet has been reported to suppress SCFA production, relative to a normal-fat (NF) diet, but FOS or other highly fermentable fibers fed as part of the HF diet restored SCFAs to concentrations found in the NF diet group (43, 44). However, in the present study, cecal contents SCFA did not differ between the NF and HF groups.

Rodent studies feeding PD or FOS at dietary concentrations similar to that used in the present study, between 2.5% and 10%, have found variable effects on physiological endpoints. Although adiposity was sometimes reduced (40, 41, 44, 45), final body weight typically was reduced as well, suggesting that the prebiotic fibers reduced body size but did not necessarily change body composition. In the present study, we found that although all groups had statistically similar final body weights, rats fed polylactose had greatly reduced epididymal fat pad weights compared with all other HF groups, indicating a change in body composition. Leptin is an adipokine whose plasma concentration correlates directly with adiposity (36, 37), which was confirmed in the present study. Although plasma leptin was significantly lower in the HFPL group than in 1 of the HF control groups (HFMFL), it did not differ significantly from the HFC group. Oral administration of propionate to mice has been found to increase plasma leptin concentration (46) and therefore could have attenuated the reduction in plasma leptin expected from the lower degree of adiposity in the HFPL group. However, in the present study, no correlation was found between plasma leptin and either cecal contents propionate or total SCFA.

A common feature of the diet-induced obesity animal model is impaired glycemic control. The AUC of the OGTT of the polylactose-fed animals was similar to that of the NF control group (NFC) and showed a trend for a reduction compared with the HFC group (P = 0.056 by Student's t test). Neither PD nor FOS at 6% of the diet reduced fasting plasma glucose or the AUC of the OGTT. This suggests that polylactose prevented the impairment of glycemic control experienced by rats fed an HF diet, whereas the commercial prebiotics PD and FOS did not. Consistent with our finding, FOS fed at 5% on an HF background did not reduce OGTT AUC, fasting glucose, or fasting insulin (P > 0.05) (43). Similarly, no reduction in fasting insulin and fasting glucose in rats fed 10% FOS on an HF background was found by Cluny et al. (40). In contrast, 21% FOS was reported to reduce the OGTT AUC and ITT AUC when compared with an HF control group (42). This suggests that a high dietary concentration of FOS is needed to improve glycemic control in animals fed HF diets, a dietary concentration that is likely unattainable in a human diet.

The HF diet–induced obesity model also presents with increased hepatic lipid accumulation (47, 48). Fatty liver is the first step in development of NAFLD, a condition with few effective treatments (2–4, 49). Simple fatty liver can be reversed by dietary- or exercise-based interventions (2–4, 47). Presently, there is little evidence that commercial prebiotics reverse fatty liver, particularly at attainable dietary amounts (42, 44, 45). Although these studies demonstrated reduced liver weights, only Nakamura et al. (44) found reduced liver lipids. In contrast, when FOS was fed at a high dose (21%), liver weight and total liver cholesterol were reduced but liver lipids were not (45). In the present study, FOS-fed animals did not exhibit a reduction in liver weight, liver lipids, or liver cholesterol concentration. However, polylactose feeding led to lower liver lipid accumulation. Liver cholesterol concentration was lower in both the polylactose and PD groups than in the HFC group.

Small differences in energy intake over time can lead to differences in body weight and adiposity. In the present study, the HFC group had a significantly greater energy intake (P < 0.05) than the HFPL group as well as a heavier fat pad weight. However, the HFMFL and the HFPL groups had essentially identical energy intakes but fat pad weight was significantly less in the HFPL group than in the HFMFL group. Thus, changes in the large intestinal microbiome are a more likely explanation for the decrease in adiposity and liver lipids and modest improvement in glycemic control found in the group fed polylactose. This group had greatly increased taxonomic abundance of Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus species and Gammaproteobacteria in the cecal contents, all of which are fermenters of galactose (50, 51), 1 of the 2 monosaccharides composing lactose, which is used to synthesize polylactose. Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus are established probiotic organisms and their increased abundance has been correlated with reduced fatty liver (9, 10, 52–55). Interestingly, fecal Gammaproteobacteria abundance increases after bariatric surgery (56), which is known to reduce fatty liver (57), yet Gammaproteobacteria abundance was slightly but significantly greater in obese children with NAFLD than in healthy normal-weight children (58). Thus, the influence of Gammaproteobacteria on fatty liver warrants further investigation.

Galactose fermenters produce large amounts of acetate and propionate, typically the 2 most abundant SCFAs (59–61), which were in much greater abundance in the cecal contents of the polylactose group relative to all other groups. After uptake into the portal circulation, acetate and propionate are used by the liver for energy metabolism and also regulate lipid synthesis, largely via activation (phosphorylation) of AMP kinase by acetate, increasing lipid oxidation in the liver (24). In addition, polylactose-, PD-, and FOS-fed animals all exhibited an increase in A. muciniphila when compared with the nonprebiotic control animals. A. muciniphila is suggested as a beneficial gut bacterium (62) and has been associated with reduced adiposity and improved glycemic control in animal and human studies (9, 63–65). Although A. muciniphila was increased in abundance in all 3 prebiotic groups, polylactose-fed animals had a statistically significantly greater abundance than the other prebiotic groups.

The mechanism by which polylactose may reduce fatty liver and adiposity is uncertain. Although viscous dietary fibers are effective at reducing fatty liver and adiposity in animal models, independently of their fermentability (66, 67), polylactose consumption does not increase small intestinal viscosity (data not shown). F:B shows a modest correlation with BMI in humans (68) and is positively associated with increased adiposity in human and animal studies (68, 69). Only the polylactose group reduced F:B relative to the NFC and HFC groups, consistent with this association. How changes in F:B might mediate changes in fatty liver and adiposity is unknown. The correlation in the present study of F:B with the cecal content of acetate and propionate suggests that SCFAs may mediate the effect of F:B on adiposity and fatty liver. Feeding acetate, propionate, or butyrate to mice as part of an HF diet has been found to attenuate the accumulation of adipose tissue relative to the HF diet alone (70). However, our results suggest there is a threshold of SCFA production needed to reduce adiposity and fatty liver, because only polylactose, which produced much greater amounts of cecal SCFA than PD or FOS, reduced adiposity and fatty liver.

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate that polylactose, a novel dietary fiber, behaves as a prebiotic in rats fed an HF diet. That is, polylactose is a dietary fiber that changes the large intestinal microbiota in a beneficial manner, provides health benefits to the host, specifically reducing adiposity and liver lipids, and thus fulfills the definition of a prebiotic dietary fiber (39). Further, polylactose produced these effects at a dietary concentration at which other prebiotic dietary fibers did not provide health benefits. Additional studies of the potential benefits of polylactose consumption seem warranted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—BEA, TCS, and DDG: designed the research; BEA: conducted the research, analyzed the microbiota data, and wrote the manuscript; ASB: conducted the SCFA analysis; BEA and DDG: analyzed all other data; DDG: edited the manuscript and was responsible for the final content; and all authors: read and approved the final manuscript.

Notes

Supported by the Midwest Dairy Association (to TCS). The funder had no role in the design, implementation, analysis, and interpretation of the data.

Author disclosures: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Supplemental Table 1 is available from the “Supplementary data” link in the online posting of the article and from the same link in the online table of contents at https://academic.oup.com/jn/.

Abbreviations used: DP, degree of polymerization; F:B, Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratio; FOS, fructooligosaccharide; HF, high fat; HFC, high-fat cellulose; HFFOS, high-fat fructooligosaccharide; HFMFL, high-fat matched free lactose; HFPD, high-fat polydextrose; HFPL, high-fat polylactose; ITT, insulin-tolerance test; NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; NASH, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; NF, normal fat; NFC, normal-fat cellulose; OGTT, oral-glucose-tolerance test; PD, polydextrose; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

Contributor Information

Breann E Abernathy, Department of Food Science and Nutrition, University of Minnesota, St. Paul, MN, USA.

Tonya C Schoenfuss, Department of Food Science and Nutrition, University of Minnesota, St. Paul, MN, USA.

Allison S Bailey, Department of Food Science and Nutrition, University of Minnesota, St. Paul, MN, USA.

Daniel D Gallaher, Department of Food Science and Nutrition, University of Minnesota, St. Paul, MN, USA.

References

- 1. WHO. Noncommunicable diseases country profiles 2018. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, Diehl AM, Brunt EM, Cusi K, Charlton M, Sanyal AJ. The diagnosis and management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: practice guideline by the American Gastroenterological Association, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, and American College of Gastroenterology. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1592–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease—meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64:73–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Smith BW, Adams LA. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2011;48:97–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Correia-Sá I, de-Sousa-Lopes H, Martins MJ, Azevedo I, Moura E, Vieira-Coelho MA. Effects of raftilose on serum biochemistry and liver morphology in rats fed with normal or high-fat diet. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2013;57:1468–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hamaguchi M, Takeda N, Kojima T, Ohbora A, Kato T, Sarui H, Fukui M, Nagata C, Takeda J. Identification of individuals with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by the diagnostic criteria for the metabolic syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1508–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tilg H, Moschen AR. Evolution of inflammation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: the multiple parallel hits hypothesis. Hepatology. 2010;52:1836–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Browning JD, Horton JD. Molecular mediators of hepatic steatosis and liver injury. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:147–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Miura K, Ohnishi H. Role of gut microbiota and Toll-like receptors in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:7381–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kirpich IA, Marsano LS, McClain CJ. Gut–liver axis, nutrition, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Biochem. 2015;48:923–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schwiertz A, Taras D, Schäfer K, Beijer S, Bos NA, Donus C, Hardt PD. Microbiota and SCFA in lean and overweight healthy subjects. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2010;18:190–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ley RE, Turnbaugh PJ, Klein S, Gordon JI. Microbial ecology: human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature. 2006;444:1022–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen Q, Liu M, Zhang P, Fan S, Huang J, Yu S, Zhang C, Li H. Fucoidan and galactooligosaccharides ameliorate high-fat diet–induced dyslipidemia in rats by modulating the gut microbiota and bile acid metabolism. Nutrition. 2019;65:50–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Al-Ghalith GA, Vangay P, Knights D. The guts of obesity: progress and challenges in linking gut microbes to obesity. Discov Med. 2015;19:81–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kalliomaki M, Collado MC, Salminen S, Isolauri E. Early differences in fecal microbiota composition in children may predict overweight. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:534–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Santacruz A, Marcos A, Wärnberg J, Martí A, Martin-Matillas M, Campoy C, Moreno LA, Veiga O, Redondo-Figuero C, Garagorri JMet al. Interplay between weight loss and gut microbiota composition in overweight adolescents. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2009;17:1906–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Woodard GA, Encarnacion B, Downey JR, Peraza J, Chong K, Hernandez-Boussard T, Morton JM. Probiotics improve outcomes after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery: a prospective randomized trial. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1198–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Koh A, De Vadder F, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, Bäckhed F. From dietary fiber to host physiology: short-chain fatty acids as key bacterial metabolites. Cell. 2016;165:1332–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Morrison DJ, Preston T. Formation of short chain fatty acids by the gut microbiota and their impact on human metabolism. Gut Microbes. 2016;7:189–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Flint HJ, Scott KP, Duncan SH, Louis P, Forano E. Microbial degradation of complex carbohydrates in the gut. Gut Microbes. 2012;3:289–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Baxter NT, Schmidt AW, Venkataraman A, Kim KS, Waldron C, Schmidt TM. Dynamics of human gut microbiota and short-chain fatty acids in response to dietary interventions with three fermentable fibers. mBio. 2019;10:e02566–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bloemen JG, Venema K, van de Poll MC, Olde Damink SW, Buurman WA, Dejong CH. Short chain fatty acids exchange across the gut and liver in humans measured at surgery. Clin Nutr. 2009;28:657–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Roy CC, Kien CL, Bouthillier L, Levy E. Short-chain fatty acids: ready for prime time?. Nutr Clin Pract. 2006;21:351–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. den Besten G, van Eunen K, Groen AK, Venema K, Reijngoud DJ, Bakker BM. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. J Lipid Res. 2013;54:2325–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pineiro M, Asp N, Reid G, Macfarlane S, Morelli L, Brunser O, Tuohy K. FAO Technical meeting on prebiotics. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:S156–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kuechel AF, Schoenfuss TC. Short communication: development of a rapid laboratory method to polymerize lactose to nondigestible carbohydrates. J Dairy Sci. 2018;101:2862–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tremaine AJ, Reid EM, Tyl CE, Schoenfuss TC. Polymerization of lactose by twin-screw extrusion to produce indigestible oligosaccharides. Int Dairy J. 2014;36:74–81. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Folch J, Lees M, Sloane Stanley G. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J Biol Chem. 1957;226:497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gallaher DD, Hassel CA, Lee K, Gallaher CM. Viscosity and fermentability as attributes of dietary fiber responsible for the hypocholesterolemic effect in hamsters. J Nutr. 1993;123:244–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Carlson J, Hospattankar A, Deng P, Swanson K, Slavin J. Prebiotic effects and fermentation kinetics of wheat dextrin and partially hydrolyzed guar gum in an in vitro batch fermentation system. Foods. 2015;4:349–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hoving LR, Heijink M, van Harmelen V, van Dijk KW, Giera M. GC-MS analysis of short-chain fatty acids in feces, cecum content, and blood samples. Methods Mol Biol. 2018;1730:247–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schneider SM, Girard-Pipau F, Anty R, van der Linde EG, Philipsen-Geerling BJ, Knol J, Filippi J, Arab K, Hebuterne X. Effects of total enteral nutrition supplemented with a multi-fibre mix on faecal short-chain fatty acids and microbiota. Clin Nutr. 2006;25:82–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Locket PL, Gallaher DD. An improved procedure for bile acid extraction and purification and tissue distribution in the rat. Lipids. 1989;24:221–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sheltawy MJ, Losowsky MS. Determination of faecal bile acids by an enzymic method. Clin Chim Acta. 1975;64:127–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna (Austria): R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wolden-Hanson T, Marck BT, Smith L, Matsumoto AM. Cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis of age-associated changes in body composition of male brown Norway rats: association of serum leptin levels with peripheral adiposity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999;54:B99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hu FB, Chen C, Wang B, Stampfer MJ, Xu X. Leptin concentrations in relation to overall adiposity, fat distribution, and blood pressure in a rural Chinese population. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25:121–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Demigne C, Levrat MA, Remesy C. Effects of feeding fermentable carbohydrates on the cecal concentrations of minerals and their fluxes between the cecum and blood plasma in the rat. J Nutr. 1989;119:1625–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gibson GR, Hutkins R, Sanders ME, Prescott SL, Reimer RA, Salminen SJ, Scott K, Stanton C, Swanson KS, Cani PDet al. Expert consensus document: the International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of prebiotics. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14:491–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cluny NL, Eller LK, Keenan CM, Reimer RA, Sharkey KA. Interactive effects of oligofructose and obesity predisposition on gut hormones and microbiota in diet-induced obese rats. Obesity. 2015;23:769–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Raza GS, Putaala H, Hibberd AA, Alhoniemi E, Tiihonen K, Makela KA, Herzig KH. Polydextrose changes the gut microbiome and attenuates fasting triglyceride and cholesterol levels in Western diet fed mice. Sci Rep. 2017;7:5294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Saha DC, Reimer RA. Long-term intake of a high prebiotic fiber diet but not high protein reduces metabolic risk after a high fat challenge and uniquely alters gut microbiota and hepatic gene expression. Nutr Res. 2014;34:789–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hira T, Suto R, Kishimoto Y, Kanahori S, Hara H. Resistant maltodextrin or fructooligosaccharides promotes GLP-1 production in male rats fed a high-fat and high-sucrose diet, and partially reduces energy intake and adiposity. Eur J Nutr. 2018;57:965–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nakamura Y, Natsume M, Yasuda A, Ishizaka M, Kawahata K, Koga J. Fructooligosaccharides suppress high-fat diet-induced fat accumulation in C57BL/6J mice. Biofactors. 2017;43:145–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Reimer RA, Maurer AD, Eller LK, Hallam MC, Shaykhutdinov R, Vogel HJ, Weljie AM. Satiety hormone and metabolomic response to an intermittent high energy diet differs in rats consuming long-term diets high in protein or prebiotic fiber. J Proteome Res. 2012;11:4065–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Xiong Y, Miyamoto N, Shibata K, Valasek MA, Motoike T, Kedzierski RM, Yanagisawa M. Short-chain fatty acids stimulate leptin production in adipocytes through the G protein-coupled receptor GPR41. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:1045–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yaqoob J, Sherrington EJ, Jeffery NM, Sanderson P, Harvey DJ, Newsholme EA, Calder PC. Comparison of the effects of a range of dietary lipids upon serum and tissue lipid composition in the rat. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1995;27:297–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Buettner R, Schölmerich J, Bollheimer LC. High-fat diets: modeling the metabolic disorders of human obesity in rodents. Obesity. 2007;15:798–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Muhammad A. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, an overview. Integr Med (Encinitas). 2019;18:42–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Poot-Hernandez AC, Rodriguez-Vazquez K, Perez-Rueda E. The alignment of enzymatic steps reveals similar metabolic pathways and probable recruitment events in Gammaproteobacteria. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. de Vries W, Stouthamer AH. Fermentation of glucose, lactose, galactose, mannitol, and xylose by Bifidobacteria. J Bacteriology. 1968;96:472–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Alves CC, Waitzberg DL, de Andrade LS, Dos Santos Aguiar L, Reis MB, Guanabara CC, Júnior OA, Ribeiro DA, Sala P. Prebiotic and synbiotic modifications of beta oxidation and lipogenic gene expression after experimental hypercholesterolemia in rat liver. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Paolella G, Mandato C, Pierri L, Poeta M, Di Stasi M, Vajro P. Gut-liver axis and probiotics: their role in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:15518–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bagarolli RA, Tobar N, Oliveira AG, Araújo TG, Carvalho BM, Rocha GZ, Vecina JF, Calisto K, Guadagnini D, Prada POet al. Probiotics modulate gut microbiota and improve insulin sensitivity in DIO mice. J Nutr Biochem. 2017;50:16–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Cani PD, Bibiloni R, Knauf C, Waget A, Neyrinck AM, Delzenne NM, Burcelin R. Changes in gut microbiota control metabolic endotoxemia-induced inflammation in high-fat diet–induced obesity and diabetes in mice. Diabetes. 2008;57:1470–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Guo Y, Huang Z-P, Liu C-Q, Qi L, Sheng Y, Zou D-J. Modulation of the gut microbiome: a systematic review of the effect of bariatric surgery. Eur J Endocrinol. 2018;178:43–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bower G, Toma T, Harling L, Jiao LR, Efthimiou E, Darzi A, Athanasiou T, Ashrafian H. Bariatric surgery and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review of liver biochemistry and histology. Obes Surg. 2015;25:2280–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Michail S, Lin M, Frey MR, Fanter R, Paliy O, Hilbush B, Reo NV. Altered gut microbial energy and metabolism in children with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2015;91(2):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. LeBlanc JG, Chain F, Martin R, Bermúdez-Humarán LG, Courau S, Langella P. Beneficial effects on host energy metabolism of short-chain fatty acids and vitamins produced by commensal and probiotic bacteria. Microb Cell Fact. 2017;16:79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Nagpal R, Wang S, Ahmadi S, Hayes J, Gagliano J, Subashchandrabose S, Kitzman DW, Becton T, Read R, Yadav H. Human-origin probiotic cocktail increases short-chain fatty acid production via modulation of mice and human gut microbiome. Sci Rep. 2018;8:12649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Pokusaeva K, Fitzgerald GF, van Sinderen D. Carbohydrate metabolism in Bifidobacteria. Genes Nutr. 2011;6:285–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Cani PD, de Vos WM. Next-generation beneficial microbes: the case of Akkermansia muciniphila. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Dao MC, Everard A, Aron-Wisnewsky J, Sokolovska N, Prifti E, Verger EO, Kayser BD, Levenez F, Chilloux J, Hoyles Let al. Akkermansia muciniphila and improved metabolic health during a dietary intervention in obesity: relationship with gut microbiome richness and ecology. Gut. 2016;65:426–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Everard A, Belzer C, Geurts L, Ouwerkerk JP, Druart C, Bindels LB, Guiot Y, Derrien M, Muccioli GG, Delzenne NMet al. Cross-talk between Akkermansia muciniphila and intestinal epithelium controls diet-induced obesity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:9066–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Schneeberger M, Everard A, Gómez-Valadés AG, Matamoros S, Ramírez S, Delzenne NM, Gomis R, Claret M, Cani PD. Akkermansia muciniphila inversely correlates with the onset of inflammation, altered adipose tissue metabolism and metabolic disorders during obesity in mice. Sci Rep. 2015;5:16643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Brockman DA, Chen X, Gallaher DD. High-viscosity dietary fibers reduce adiposity and decrease hepatic steatosis in rats fed a high-fat diet. J Nutr. 2014;144:1415–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Hung SC, Bartley G, Young SA, Albers DR, Dielman DR, Anderson WH, Yokoyama W. Dietary fiber improves lipid homeostasis and modulates adipocytokines in hamsters. J Diabetes. 2009;1:194–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Koliada A, Syzenko G, Moseiko V, Budovska L, Puchkov K, Perederiy V, Gavalko Y, Dorofeyev A, Romanenko M, Tkach Set al. Association between body mass index and Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio in an adult Ukrainian population. BMC Microbiol. 2017;17:120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Kasai C, Sugimoto K, Moritani I, Tanaka J, Oya Y, Inoue H, Tameda M, Shiraki K, Ito M, Takei Yet al. Comparison of the gut microbiota composition between obese and non-obese individuals in a Japanese population, as analyzed by terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism and next-generation sequencing. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015;15:100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. den Besten G, Bleeker A, Gerding A, van Eunen K, Havinga R, van Dijk TH, Oosterveer MH, Jonker JW, Groen AK, Reijngoud D-Jet al. Short-chain fatty acids protect against high-fat diet–induced obesity via a PPARγ-dependent switch from lipogenesis to fat oxidation. Diabetes. 2015;64:2398–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.