Abstract

With rapid and accurate molecular influenza testing now widely available in clinical settings, influenza vaccine effectiveness (VE) studies can prospectively select participants for enrollment based on real-time results rather than enrolling all eligible patients regardless of influenza status, as in the traditional test-negative design (TND). Thus, we explore advantages and disadvantages of modifying the TND for estimating VE by using real-time, clinically available viral testing results paired with acute respiratory infection eligibility criteria for identifying influenza cases and test-negative controls prior to enrollment. This modification, which we have called the real-time test-negative design (rtTND), has the potential to improve influenza VE studies by optimizing the case-to-test-negative control ratio, more accurately classifying influenza status, improving study efficiency, reducing study cost, and increasing study power to adequately estimate VE. Important considerations for limiting biases in the rtTND include the need for comprehensive clinical influenza testing at study sites and accurate influenza tests.

Keywords: influenza, vaccine effectiveness, test-negative design, real-time test-negative design, clinical testing

Rapid molecular influenza testing has potential to improve vaccine effectiveness studies. Prospectively enrolling participants based on real-time results rather than enrolling all eligible patients regardless of influenza status (traditional test-negative design) can increase efficiency and optimize the case-to-test-negative control ratio.

Globally, millions of influenza virus infections occur every season, resulting in an estimated 290 000–650 000 deaths each year [1]. With the rapid genetic changes in influenza viruses, seasonal influenza vaccines have to be updated annually. Thus, measuring vaccine effectiveness (VE) annually is critical in evaluating vaccine performance and improving vaccine performance in subsequent years. The test-negative design (TND) is the most commonly used study design to evaluate influenza VE. The design involves enrolling patients during the influenza season who meet prespecified clinical criteria for an acute respiratory infection (ARI), such as fever and cough, and who are subsequently tested to differentiate between test-positive cases and test-negative controls. Traditionally, this influenza testing is completed in specialized research laboratories long after patient enrollment in the study, meaning case/test-negative control status and their ratio in the study are not known at the time of enrollment. After influenza testing is completed, VE is estimated by comparing the odds of antecedent vaccination between influenza-positive cases and test-negative controls, while controlling for key confounders [2–10].

Prior studies have evaluated the underlying assumptions of the design, quantified the potential effect of biases, and validated the design against randomized clinical trials [11–13].The TND can reduce confounding by enrolling cases and test-negative controls from the same underlying population with similar healthcare-seeking behavior, participation rates, initial presentation, and data quality and completeness [12, 14, 15]. The TND offers logistical advantages over other study designs (case-control and cohort) because it can be conducted in countries with existing surveillance systems and electronic medical records, thus reducing costs and improving efficiency.

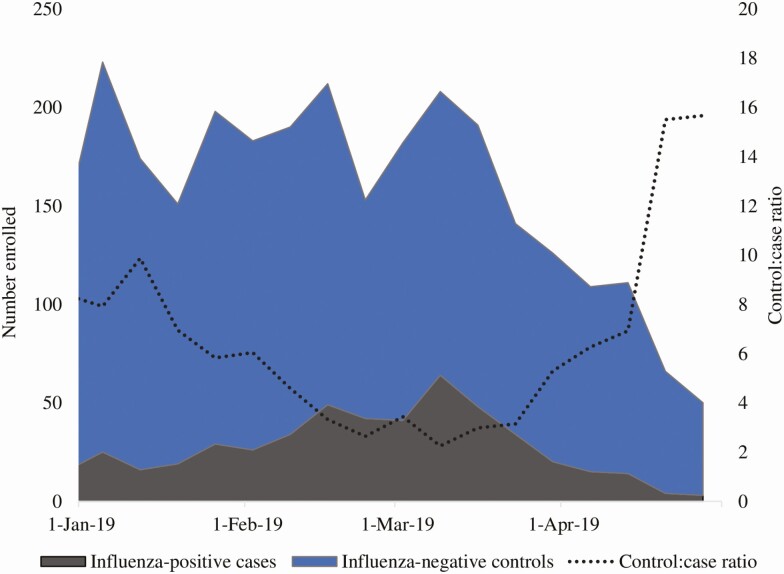

However, the traditional TND also has limitations, especially for hospitalized and severely ill patients [16–20]. Depending on influenza activity and timing of enrollment in a given season, the case-to-test-negative control ratio in the TND may be as low as 1:15 [21, 22], with diminishing returns on statistical power when the case-to-test-negative control ratio is lower than 1:4 (Figure 2) [23]. Because resource-intensive efforts (especially in hospital settings) are required to screen patients who meet the TND ARI eligibility criteria, ascertain vaccination history, abstract clinical data from medical charts, and conduct laboratory research testing for all enrolled patients, the TND could introduce information bias during the lengthy data-collection process. It also becomes less efficient and may be cost-prohibitive, particularly when influenza activity is low and the test-negative controls greatly outnumber the influenza cases [24]. As a result, many TND VE studies are not powered to conduct subanalyses to look at VE by virus subtype or lineage, which are critical for determining whether there are egg-adapted changes in the vaccine [2, 25]. The TND may also be subject to selection bias, particularly in inpatient settings, where controls may meet the ARI case definition due to respiratory exacerbation of chronic conditions and are also more likely to be vaccinated because of those conditions [13].

Figure 2.

Study participant enrollment and case to test-negative control ratio in a test-negative study design within a hospital-based surveillance system, 2018–2019.

With advances in viral molecular diagnostic testing with accurate results available in near real time in many hospital settings, test-positive case versus test-negative control status can be determined at the time of study enrollment for many patients. This provides an opportunity to optimize the case-to-test-negative control ratio and potentially greatly improve study efficiency. Indeed, several influenza VE studies have used real-time clinical testing to identify their study population [26–28].

In this paper, we explore the advantages and disadvantages of modifying the TND to use real-time viral testing results among patients who meet prespecified ARI eligibility criteria for identifying influenza cases and test-negative controls for enrollment (Table 1). Using real-time laboratory testing modifies the TND, such that influenza test results are known at enrollment and the case-to-test-negative control ratio can be tracked (and thus controlled) throughout the enrollment period. Thus, we have named this modification to the traditional TND as “the real-time test-negative design” (rtTND). We also consider the feasibility and potential biases of other modifications to the TND, including consenting and collecting research samples on all patients with ARI and then re-contacting a subset of patients with a specific case-to-control ratio once research influenza testing is complete, and limiting enrollment of patients with ARI to peak influenza season.

Table 1.

Strengths and Limitations of the Test-negative Design and the Real-time Test-negative Design

| Test-negative Design | Real-time Test-negative Design | |

|---|---|---|

| Strengths | 1. Well-established and validated methodology | 1. Optimizes the case-to-test-negative control ratio |

| 2. Simple to implement | 2. Reduces confounding by enrolling cases and controls from the same healthcare-seeking population | |

| 3. Reduces confounding by enrolling cases and controls from the same healthcare-seeking population | 3. Improves study efficiency | |

| 4. Conducted within existing surveillance systems | 4. Reduces use of study resources and cost | |

| Limitations | 1. Can be costly | 1. Requires widespread use of clinical testing with molecular assays |

| 2. Large sample size requirements | 2. Subject to bias through differential data-collection practices by influenza status | |

| 3. Time consuming/resource intensive | 3. Subject to selection bias if controls are preferentially chosen | |

| 4. Subject to selection bias in inpatient setting if chronic conditions are associated with vaccine uptake and increased probability of hospital admission for respiratory non-ARI events [13] | 4. Subject to selection bias in inpatient setting if chronic conditions are associated with vaccine uptake and increased probability of hospital admission for respiratory non-ARI events [13] |

Abbreviation: ARI, acute respiratory infection.

IMPLEMENTING THE REAL-TIME TEST-NEGATIVE DESIGN

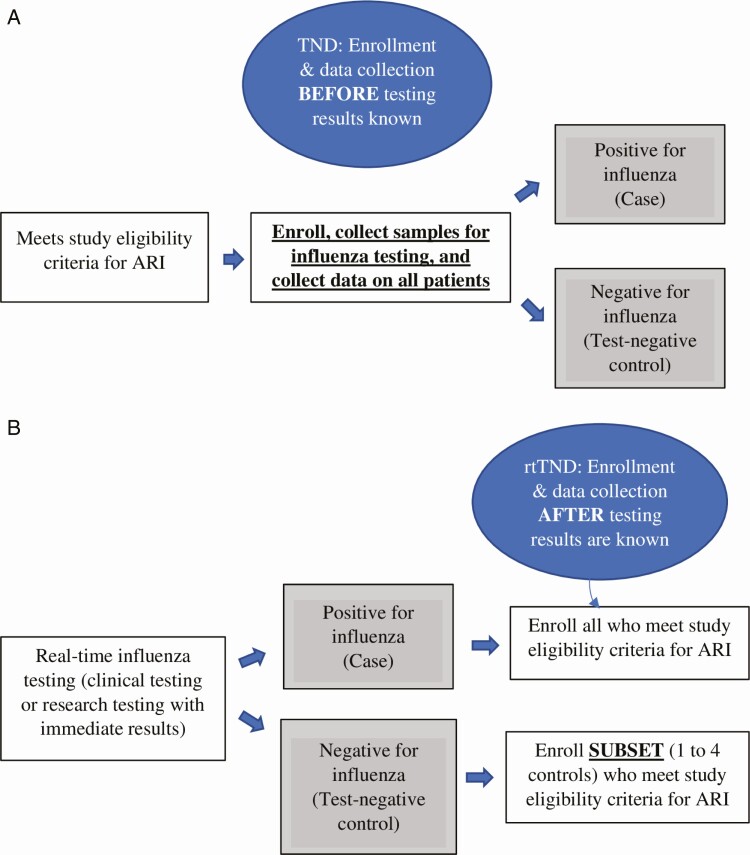

In a traditional TND, study personnel typically enroll all eligible patients who meet prespecified ARI criteria without knowledge of influenza status during the defined study periods (Figure 1). The case-to-test-negative control ratio depends on influenza prevalence, which varies based on enrollment start and end relative to the ascent, peak, and descent of the influenza season (Figure 2). One of the major disadvantages of the TND is lost resources from data-collection efforts directed towards a high number of test-negative controls relative to fewer influenza-positive cases. Four recent influenza VE studies using the traditional TND have had case-to-control ratios higher than 1:4 [2, 21, 22, 25]. Thus, we estimate that these studies could have enrolled up to 800 fewer patients, improving efficiency and potentially reducing selection and information bias.

Figure 1.

A, Traditional TND: participant enrollment. B, rtTND: participant enrollment. Abbreviations: ARI, acute respiratory infection; rtTND, real-time test-negative design; TND, test-negative design.

As molecular influenza testing is highly accurate and widely available in most hospitals, the rtTND modifies the TND to use real-time laboratory testing results available at the time of study enrollment to set the case-to-test-negative control ratio. One of the primary advantages of using real-time testing results is that it enables study personnel to calibrate enrollment of cases and test-negative controls, reducing the typical excess of test-negative controls found in the TND and improving the study efficiency. Reduced enrollment of excess controls also reduces the use of study resources needed for critical study procedures, such as vaccine verification and data collection, which can be particularly resource intensive for hospitalized and critically ill patients.

Similar to the TND, the rtTND utilizes prespecified ARI eligibility criteria for inclusion in the study (Figure 1). Thus, the advantage of having similar healthcare-seeking behavior among cases and test-negative controls in the TND is retained in the rtTND. The rtTND also allows for flexibility in the approach to enrollment of test-negative controls, such that there is the option to match cases and test-negative controls based on patient characteristics and timing of enrollment during the season, further improving study efficiency by balancing covariates [24].

The rtTND is also less burdensome for study enrollees, as the number of respiratory biospecimens collected, which typically requires nasal swabbing in influenza studies, is minimized. In the traditional TND, study patients often undergo repeated nasal swabbing, initially by clinical teams for “clinical testing,” then by study personnel for “research testing.” In an rtTND, a single respiratory specimen may be collected from each participant (as part of routine care if the clinicians obtained molecular influenza testing or as a research procedure if the patient is otherwise eligible for study inclusion but did not have clinical influenza testing). This approach is now possible due to widespread availability of highly accurate molecular influenza testing in hospital laboratories. Limiting the number of nasal samplings has many advantages. It avoids unnecessary procedures, thus improving the patient experience. Enrolling patients without requiring repeat nasal sampling is also likely to decrease participant refusal rates, thus increasing sample size and generalizability, improving the external validity of study results by minimizing selection bias. Additionally, cost savings are gained from not having to do repeat testing and not having to ship specimens to a central laboratory. If additional testing is required on the specimens, such as testing for viral load or viral sequence, use of the discarded clinical testing specimen is also a possibility.

Clinically obtained influenza tests in the rtTND have an advantage over the use of research specimens in the traditional TND in terms of potentially increased sensitivity of influenza detection when there is a delay between clinical presentation and enrollment for research. In a traditional TND, nasal specimen collection for study purposes is required and case/test-negative control status is determined by influenza results from those samples. Although enrollment and sample collection are restricted to a defined period following disease onset, sometimes study specimens may be collected several days after the clinical sample is taken. As a result, specimens collected for study purposes in the TND may be less likely to have influenza virus detected than the clinical specimens, especially if those samples are collected more than 4 days after disease onset [29]. This is often particularly problematic for critically ill patients because consent for study inclusion may be delayed until the patient’s clinical condition has stabilized. Patients with influenza who die early in the hospitalization are often missed altogether (not enrolled) due to study personnel not gaining access to dying patients. In critically ill patients with influenza who survive, influenza testing on study swabs collected after patient stabilization may be less likely to yield positive results due to the time delay from onset of illness and interceding treatment with antiviral medications. Therefore, relying on delayed study sample collection for classifying influenza status may systematically result in missing the most severely ill patients and misclassifying the most severely ill enrolled patients with influenza as test-negative controls. Alternatively, in the rtTND, clinical influenza testing on specimens collected early in the patient’s course is used to classify case/test-negative control status. Clinical test specimens are usually collected shortly after the patient presents at a healthcare facility and almost assuredly earlier in the course of illness than specimens obtained for study purposes. Early sampling during maximal viral shedding (ie, within the first 2 days of presentation [30]) increases the chance of detecting influenza virus, thus improving the validity of study results by minimizing misclassification of case-test-negative control status.

POTENTIAL IMPLICATIONS OF USING RTTND FOR VACCINE EFFECTIVENESS EVALUATIONS

We acknowledge that the rtTND has certain limitations. Three primary aspects of using real-time testing for influenza VE evaluations warrant consideration.

Variability in Clinical Influenza Testing

First, real-time influenza testing is frequently part of routine clinical care for hospitalized patients with ARI during influenza season but deciding who to test is not standardized across healthcare centers. If the rtTND relies solely on clinical testing, selection bias may be introduced if only a subset of all patients presenting with ARI are clinically tested at any given facility and, for some reason, those patients are inherently different from those with ARI who are not tested [15]. If tested and untested patients have the same risk for influenza, VE estimates will not be biased, even if tested patients are more likely to be unvaccinated. However, if tested patients are more likely to be unvaccinated and also more likely to be influenza positive, VE will be overestimated because the study will be enriched with unvaccinated influenza-positive cases compared with influenza-negative controls. Conversely, if, compared with untested patients, tested patients are more likely to be unvaccinated and less likely to have influenza, VE will be underestimated by enriching the study with unvaccinated controls. The magnitude of bias will depend on the extent of preferential selection of patients, the overall proportion of patients tested, and VE. Thus, the use of rtTND may not be appropriate in settings where clinical testing is not widely practiced.

To avoid variability in clinical testing altogether, one approach could be to consent and collect research specimens on all patients with ARI and wait to fully enroll cases and a subset of controls once research influenza testing is complete and disease status is known. This approach would require contacting patients after their initial clinical visit to collect information on risk factors and potential confounders not found (or inaccurate) in medical records, such as smoking status and alcohol use. While this may be feasible in situations where the timing between the clinical visit and ascertainment of influenza status is relatively short, there could be substantial loss to follow-up depending on the quality of contact information and characteristics of the patient population, which would increase the likelihood of selection bias. While this approach is less resource intensive than a TND, it requires prospective consenting and research specimen collection from patients who will not be included in the final analysis and shipping and testing of specimens at a central laboratory. It is also still susceptible to misclassification of influenza status if research specimens are collected several days after initial presentation. An alternative approach could be to restrict enrollment to the peak influenza period and collect research specimens on all patients with ARI during that time; however, this would be logistically challenging and could result in a reduced number of influenza cases such that a VE analysis would be underpowered.

Ideally, in rtTND studies, all patients with ARI would be clinically tested for influenza and the history of vaccination would not influence the decision to test. A previous study suggested this is common, with most clinicians testing for influenza based on ARI symptoms, unaware of vaccination status at the time of deciding whether to test [31]. If true, bias is not likely to be substantial unless clinical factors that affect testing practices are correlated with vaccination status (eg, testing rates are increased among unhealthy patients compared with healthy patients with a high likelihood of influenza). However, another study among hospitalized older adults did show that clinicians were less likely to test vaccinated patients with ARI than unvaccinated patients with ARI [32]; this raises an important consideration of vaccine-induced attenuation of disease severity—that is, those who were vaccinated may have had milder disease presentation and thus less likely to be tested [33]. To minimize the potential of this selection bias, which may be present in both TND and rtTND studies, a more stringent clinical case definition of ARI could be employed [33]. Additionally, real-time collection and testing of study samples for influenza virus could be incorporated into study procedures for patients meeting the ARI criteria who did not undergo clinical testing, such that all eligible patients receive an influenza test with real-time results, either through routine clinical care or study participation. This solution of supplementing clinical testing with real-time research testing as needed remains cost-effective because it still eliminates the need for research testing for most enrolled patients.

Study Enrollment Practices and Data-collection Efforts

Second, factors such as data quality and completeness are similar in cases and test-negative controls in the traditional TND but could differ for the rtTND. Unlike the TND, rtTND study investigators may have access to both vaccination status and influenza testing results of patients prior to enrollment. As a result, vaccinated test-negative controls could be more likely to be enrolled than unvaccinated test-negative controls if researchers’ pre-existing beliefs about the effectiveness of influenza vaccination influence enrollment practices (either consciously or unconsciously). In this scenario, VE would be overestimated through enriching the study with vaccinated test-negative controls. This type of preferential selection of test-negative controls could be avoided by protocolizing selection of controls to match that of cases and by blinding study personnel responsible for enrollment to vaccination status until enrollment is complete. Additionally, potential biases could be introduced through differential data-collection efforts (eg, stronger efforts made to identify prior vaccine receipt in controls than cases) if study personnel responsible for vaccine verification are unblinded to case-control status. Blinding study personnel who perform vaccine verification to influenza outcome status, although potentially logistically difficult, would help reduce bias by ensuring that equal efforts are made in obtaining vaccination history for cases and test-negative controls. Blinding efforts would be beneficial in both the TND and rtTND, where clinical test results may be available at the time of vaccine verification processes.

Validity of the Diagnostic Assay

Third, the sensitivity and specificity of diagnostic assays used for detecting influenza can affect VE estimates in the rtTND [34]. The 2 most commonly used clinical assays include molecular reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), the gold standard, and antigen-based rapid influenza diagnostic tests (RIDTs). Both assays have specificity greater than 90% [35–37]. However, molecular assays have higher sensitivity (90–95%) compared with antigen-based RIDTs (50–70%) [37, 38]. Because sensitivity of RIDTs is lower than specificity, the use of RIDTs for clinical testing is more likely to cause misclassification of cases as test-negative controls, thus potentially underestimating VE as shown by Orenstein et al [39] and Jackson and Rothman [34]. Thus, we do not recommend the use of RIDTs for case/test-negative control classification in VE studies, including rtTND, that incorporate clinical test results. With increased availability of rapid molecular assays that meet US Food and Drug Administration new standards for higher specificity [29], we believe that clinical influenza molecular testing can be useful for classifying case/test-negative control status in influenza VE studies.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, we propose the use of the rtTND as a modification to the traditional TND for influenza VE studies. The rtTND takes full advantage of the widespread availability of accurate and timely molecular influenza testing. This approach has the potential to greatly improve influenza VE studies by accurately classifying influenza status at enrollment and enabling the study to optimize the case-to-test-negative control ratio. The rtTND may be particularly beneficial for estimating severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) VE, once a vaccine becomes available, due to stringent infection-prevention control measures that make access to patients for sample collection challenging. Depending on study setting, objectives, and resource availability, investigators should carefully weigh the feasibility, advantages, and disadvantages of the rtTND, TND, or other modifications to the TND before choosing to implement one. Important considerations for the rtTND include whether clinical influenza testing at study sites is comprehensive among those with ARI and whether strategies to minimize bias related to enrollment and data-collection practices derived from influenza status knowledge are in place. In addition, it is imperative that clinical and research testing use highly sensitive and specific molecular tests to detect influenza infections. The rtTND may be particularly useful for studying influenza VE in critically ill populations, where the prevalence of real-time clinical influenza testing is high, influenza prevalence in the season is relatively low, and the traditional TND is at risk for systematically failing to enroll the most severely ill patients.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors gratefully acknowledge the collaboration and support of Pediatric Acute Lung and Sepsis Investigator’s Network and Pediatric Intensive Care Influenza Study Group (PALISI PICFLU) study site investigators who enrolled patients and made other major contributions to this study, specified as follows: Michele Kong, MD (Children’s of Alabama, Birmingham, AL); Ronald C. Sanders, Jr, MD, MS; Katherine Irby, MD (Arkansas Children’s Hospital, Little Rock, AR); Mary Gaspers, MD, MPH (Diamond Children’s Medical Center, Tucson, AZ); Barry Markovitz, MD (Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA); Natalie Cvijanovich, MD (UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital Oakland, Oakland, CA); Adam Schwarz, MD (Children’s Hospital of Orange County, Orange, CA); Peter Mourani, MD; Aline Maddux, MD (Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora, CO); Natalia Martinez Schlurmann, MD (UF Health Shands Children’s Hospital, Gainesville, FL); Keiko Tarquinio, MD (Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta at Egleston, Atlanta, GA); Bria M. Coates, MD (Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, Chicago, IL); Janice Sullivan, MD, and Vicki Montgomery, MD, FCCM (Norton Children’s Hospital, Louisville, KY); Heidi R. Flori, MD (C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital, Ann Arbor, MI); Janet Hume, MD, PhD (University of Minnesota Masonic Children’s Hospital, Minneapolis, MN); Jennifer E. Schuster, MD (Children’s Mercy Kansas City, Kansas City, MO); Melissa Cullimore, MD, PhD; Russell McCulloh, MD; Sidharth Mahapatra, MD, PhD (Children’s Hospital of Nebraska, Omaha, NE); Shira J. Gertz, MD (Saint Barnabas Medical Center, Livingston, NJ); Ryan Nofziger, MD, FAAP (Akron Children’s Hospital, Akron, OH); Steven L. Shein, MD (Rainbow Babies and Children’s Hospital, Cleveland, OH); Mark W. Hall, MD (Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, OH); Neal Thomas, MD (Penn State Hershey’s Children’s Hospital, Hershey, PA); Scott L. Weiss, MD (The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA); Laura L. Loftis, MD (Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, TX); Janet A. Englund, MD, and Lincoln S. Smith, MD (Seattle Children’s Hospital, Seattle, WA)

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Financial support. This work was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (grant number 75D301-19-C-05670; to W. H. S.) and the National Institutes of Health (grant number R37 AI032042; to M. E. H.).

Potential conflicts of interest. C. G. G. has been paid by Pfizer, Merck, and Sanofi-Pasteur for his consulting services and has received research funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Campbell Alliance, National Institutes of Health, Food and Drug Administration, and Agency for Health Care Research and Quality; M. E. H. received research funding from National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; I. D. P. has received research funding to his institution from Asahi Kasei Pharma, Immunexpress Inc, and Janssen Pharmaceuticals. S. M. B. has been paid by Janssen for his services for research related to the treatment of influenza; N. H. has been paid by Sanofi-Pasteur, Quidel, Karius, and Moderna for her consulting services and research related to influenza, and received research funding from CDC; A. G. R. has received research funding from CDC and Genentech Inc, been paid by La Jolla Pharma Inc for her consulting services, and received royalties from UpToDate; T. W. R. is Director of Affairs of Cumberland Pharmaceuticals; H. K. T. serves on the Data Safety and Monitoring Board for Seqirus; W. H. S. has received research funding from CDC and has been paid by Merck and Gilead Sciences for his work on pneumococcal disease and hepatitis C. All other authors report no potential conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Contributor Information

Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness in the Critically Ill (IVY) Investigators and the Pediatric Intensive Care Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness (PICFLU-VE) Investigators:

Michele Kong, Jr Ronald C Sanders, Katherine Irby, Mary Gaspers, Barry Markovitz, Natalie Cvijanovich, Adam Schwarz, Peter Mourani, Aline Maddux, Natalia Martinez Schlurmann, Keiko Tarquinio, Bria M Coates, Janice Sullivan, Vicki Montgomery, Heidi R Flori, Janet Hume, Jennifer E Schuster, Melissa Cullimore, Russell McCulloh, Sidharth Mahapatra, Shira J Gertz, Ryan Nofziger, Steven L Shein, Mark W Hall, Neal Thomas, Scott L Weiss, Laura L Loftis, Janet A Englund, and Lincoln S Smith

References

- 1. Iuliano AD, Roguski KM, Chang HH, et al. ; Global Seasonal Influenza-associated Mortality Collaborator Network . Estimates of global seasonal influenza-associated respiratory mortality: a modelling study. Lancet 2018; 391:1285–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jackson ML, Chung JR, Jackson LA, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in the United States during the 2015–2016 season. N Engl J Med 2017; 377:534–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rolfes MA, Flannery B, Chung JR, et al. Effects of influenza vaccination in the United States During the 2017–2018 influenza season. Clin Infect Dis 2019; 69:1845–13. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Doyle JD, Chung JR, Kim SS, et al. Interim estimates of 2018-19 seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness—United States, February 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019; 68:135–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rondy M, Kissling E, Emborg H-D, et al. Interim 2017/18 influenza seasonal vaccine effectiveness: combined results from five European studies. Euro Surveill 2018; 23:18-00086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Belongia EA, Simpson MD, King JP, et al. Variable influenza vaccine effectiveness by subtype: a systematic review and meta-analysis of test-negative design studies. Lancet Infect Dis 2016; 16:942–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Flannery B, Chung JR, Belongia EA, et al. Interim estimates of 2017-18 seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness—United States, February 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018; 67:180–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Skowronski DM, Chambers C, Sabaiduc S, et al. Interim estimates of 2016/17 vaccine effectiveness against influenza A(H3N2), Canada, January 2017. Euro Surveill 2017; 22:30460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Flannery B, Chung JR, Monto AS, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in the United States during the 2016–2017 season. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 68:1798–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ferdinands JM, Gaglani M, Martin ET, et al. Prevention of influenza hospitalization among adults in the United States, 2015–2016: results from the US Hospitalized Adult Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network (HAIVEN). J Infect Dis 2018; 220:1265–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. De Serres G, Skowronski DM, Wu XW, Ambrose CS. The test-negative design: validity, accuracy and precision of vaccine efficacy estimates compared to the gold standard of randomised placebo-controlled clinical trials. 2013; 18:20585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jackson ML, Nelson JC. The test-negative design for estimating influenza vaccine effectiveness. Vaccine 2013; 31:2165–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Foppa IM, Haber M, Ferdinands JM, Shay DK. The case test-negative design for studies of the effectiveness of influenza vaccine. Vaccine 2013; 31:3104–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vandenbroucke JP, Pearce N. Test-negative designs: differences and commonalities with other case–control studies with “other patient” controls. 2019; 30:838–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fukushima W, Hirota Y. Basic principles of test-negative design in evaluating influenza vaccine effectiveness. Vaccine 2017; 35:4796–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Puig-Barberà J, Arnedo-Pena A, Pardo-Serrano F, et al. Effectiveness of seasonal 2008–2009, 2009–2010 and pandemic vaccines, to prevent influenza hospitalizations during the autumn 2009 influenza pandemic wave in Castellón, Spain: a test-negative, hospital-based, case–control study. Vaccine 2010; 28:7460–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cheng AC, Kotsimbos T, Kelly HA, et al. Effectiveness of H1N1/09 monovalent and trivalent influenza vaccines against hospitalization with laboratory-confirmed H1N1/09 influenza in Australia: a test-negative case control study. Vaccine 2011; 29:7320–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cheng AC, Holmes M, Irving LB, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness against hospitalisation with confirmed influenza in the 2010–11 seasons: a test-negative observational study. PLoS One 2013; 8:e68760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Talbot HK, Griffin MR, Chen Q, Zhu Y, Williams JV, Edwards KM. Effectiveness of seasonal vaccine in preventing confirmed influenza-associated hospitalizations in community dwelling older adults. J Infect Dis 2011; 203:500–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Talbot HK, Zhu Y, Chen Q, Williams JV, Thompson MG, Griffin MR. Effectiveness of influenza vaccine for preventing laboratory-confirmed influenza hospitalizations in adults, 2011–2012 influenza season. Clinl Infect Dis 2013; 56:1774–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ferdinands JM, Gaglani M, Martin ET, et al. Prevention of influenza hospitalization among adults in the United States, 2015–2016: results from the US Hospitalized Adult Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network (HAIVEN). J Infect Dis 2019; 220:1265–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Flannery B, Chung J, Monto AS, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in the United States during the 2016–2017 season. Open Forum Infect Dis 2017; 4:S451– S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Grimes DA, Schulz KF. Compared to what? Finding controls for case-control studies. Lancet 2005; 365:1429–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Verani JR, Baqui AH, Broome CV, et al. Case-control vaccine effectiveness studies: data collection, analysis and reporting results. Vaccine 2017; 35:3303–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Feldstein LR, Ogokeh C, Rha B, et al. Vaccine effectiveness against influenza hospitalization among children in the United States, 2015–2016. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2020; doi: 10.1093/jpids/piaa017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sullivan SG, Arriola CS, Bocacao J, et al. Heterogeneity in influenza seasonality and vaccine effectiveness in Australia, Chile, New Zealand and South Africa: early estimates of the 2019 influenza season. 2019; 24:1900645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Skowronski DM, Masaro C, Kwindt TL, et al. Estimating vaccine effectiveness against laboratory-confirmed influenza using a sentinel physician network: results from the 2005-2006 season of dual A and B vaccine mismatch in Canada. Vaccine 2007; 25:2842–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nichols MK, Andrew MK, Ye L, et al. The impact of prior season vaccination on subsequent influenza vaccine effectiveness to prevent influenza-related hospitalizations over 4 influenza seasons in Canada. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 69:970–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Information on rapid molecular assays, RT-PCR, and other molecular assays for diagnosis of influenza virus infection. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/diagnosis/molecular-assays.htm. Accessed 13 January 2019.

- 30. Loeb M, Singh PK, Fox J, et al. Longitudinal study of influenza molecular viral shedding in Hutterite communities. J Infect Dis 2012; 206:1078–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Balasubramani GK, Saul S, Nowalk MP, Middleton DB, Ferdinands JM, Zimmerman RK. Does influenza vaccination status change physician ordering patterns for respiratory viral panels? Inspection for selection bias. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2019; 15:91–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hartman L, Zhu Y, Edwards KM, Griffin MR, Talbot HK. Underdiagnosis of influenza virus infection in hospitalized older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018; 66:467–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chua H, Feng S, Lewnard JA, et al. The use of test-negative controls to monitor vaccine effectiveness: a systematic review of methodology. Epidemiology 2020; 31:43–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jackson ML, Rothman KJ. Effects of imperfect test sensitivity and specificity on observational studies of influenza vaccine effectiveness. Vaccine 2015; 33:1313–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Irving SA, Vandermause MF, Shay DK, Belongia EA. Comparison of nasal and nasopharyngeal swabs for influenza detection in adults. Clin Med Res 2012; 10:215–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Roa PL, Catalán P, Giannella M, de Viedma DG, Sandonis V, Bouza E. Comparison of real-time RT-PCR, shell vial culture, and conventional cell culture for the detection of the pandemic influenza A (H1N1) in hospitalized patients. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2011; 69:428–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Rapid influenza diagnostic tests. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/diagnosis/clinician_guidance_ridt.htm. Accessed 13 January 2019.

- 38. Uyeki TM. Influenza diagnosis and treatment in children: a review of studies on clinically useful tests and antiviral treatment for influenza. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2003; 22:164–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Orenstein EW, De Serres G, Haber MJ, et al. Methodologic issues regarding the use of three observational study designs to assess influenza vaccine effectiveness. Int J Epidemiol 2007; 36:623–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]