Abstract

Background

Asthma affects 350 million people worldwide including 45% to 70% with mild disease. Treatment is mainly with inhalers containing beta₂‐agonists, typically taken as required to relieve bronchospasm, and inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) as regular preventive therapy. Poor adherence to regular therapy is common and increases the risk of exacerbations, morbidity and mortality. Fixed‐dose combination inhalers containing both a steroid and a fast‐acting beta₂‐agonist (FABA) in the same device simplify inhalers regimens and ensure symptomatic relief is accompanied by preventative therapy. Their use is established in moderate asthma, but they may also have potential utility in mild asthma.

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of single combined (fast‐onset beta₂‐agonist plus an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS)) inhaler only used as needed in people with mild asthma.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Airways Trials Register, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE and Embase, ClinicalTrials.gov and the World Health Organization (WHO) trials portal. We contacted trial authors for further information and requested details regarding the possibility of unpublished trials. The most recent search was conducted on 19 March 2021.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and cross‐over trials with at least one week washout period. We included studies of a single fixed‐dose FABA/ICS inhaler used as required compared with no treatment, placebo, short‐acting beta agonist (SABA) as required, regular ICS with SABA as required, regular fixed‐dose combination ICS/long‐acting beta agonist (LABA), or regular fixed‐dose combination ICS/FABA with as required ICS/FABA. We planned to include cluster‐randomised trials if the data had been or could be adjusted for clustering. We excluded trials shorter than 12 weeks. We included full texts, abstracts and unpublished data.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted data. We analysed dichotomous data as odds ratios (OR) or rate ratios (RR) and continuous data as mean difference (MD). We reported 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We used Cochrane's standard methodological procedures of meta‐analysis. We applied the GRADE approach to summarise results and to assess the overall certainty of evidence. Primary outcomes were exacerbations requiring systemic steroids, hospital admissions/emergency department or urgent care visits for asthma, and measures of asthma control.

Main results

We included six studies of which five contributed results to the meta‐analyses. All five used budesonide 200 μg and formoterol 6 μg in a dry powder formulation as the combination inhaler. Comparator fast‐acting bronchodilators included terbutaline and formoterol. Two studies included children aged 12+ and adults; two studies were open‐label. A total of 9657 participants were included, with a mean age of 36 to 43 years. 2.3% to 11% were current smokers.

FABA / ICS as required versus FABA as required

Compared with as‐required FABA alone, as‐required FABA/ICS reduced exacerbations requiring systemic steroids (OR 0.45, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.60, 2 RCTs, 2997 participants, high‐certainty evidence), equivalent to 109 people out of 1000 in the FABA alone group experiencing an exacerbation requiring systemic steroids, compared to 52 (95% CI 40 to 68) out of 1000 in the FABA/ICS as‐required group. FABA/ICS as required may also reduce the odds of an asthma‐related hospital admission or emergency department or urgent care visit (OR 0.35, 95% CI 0.20 to 0.60, 2 RCTs, 2997 participants, low‐certainty evidence).

Compared with as‐required FABA alone, any changes in asthma control or spirometry, though favouring as‐required FABA/ICS, were small and less than the minimal clinically‐important differences. We did not find evidence of differences in asthma‐associated quality of life or mortality. For other secondary outcomes FABA/ICS as required was associated with reductions in fractional exhaled nitric oxide, probably reduces the odds of an adverse event (OR 0.82, 95% CI 0.71 to 0.95, 2 RCTs, 3002 participants, moderate‐certainty evidence) and may reduce total systemic steroid dose (MD ‐9.90, 95% CI ‐19.38 to ‐0.42, 1 RCT, 443 participants, low‐certainty evidence), and with an increase in the daily inhaled steroid dose (MD 77 μg beclomethasone equiv./day, 95% CI 69 to 84, 2 RCTs, 2554 participants, moderate‐certainty evidence).

FABA/ICS as required versus regular ICS plus FABA as required

There may be little or no difference in the number of people with asthma exacerbations requiring systemic steroid with FABA/ICS as required compared with regular ICS (OR 0.79, 95% CI 0.59 to 1.07, 4 RCTs, 8065 participants, low‐certainty evidence), equivalent to 81 people out of 1000 in the regular ICS plus FABA group experiencing an exacerbation requiring systemic steroids, compared to 65 (95% CI 49 to 86) out of 1000 FABA/ICS as required group. The odds of an asthma‐related hospital admission or emergency department or urgent care visit may be reduced in those taking FABA/ICS as required (OR 0.63, 95% CI 0.44 to 0.91, 4 RCTs, 8065 participants, low‐certainty evidence).

Compared with regular ICS, any changes in asthma control, spirometry, peak flow rates (PFR), or asthma‐associated quality of life, though favouring regular ICS, were small and less than the minimal clinically important differences (MCID). Adverse events, serious adverse events, total systemic corticosteroid dose and mortality were similar between groups, although deaths were rare, so confidence intervals for this analysis were wide. We found moderate‐certainty evidence from four trials involving 7180 participants that FABA/ICS as required was likely associated with less average daily exposure to inhaled corticosteroids than those on regular ICS (MD ‐154.51 μg/day, 95% CI ‐207.94 to ‐101.09).

Authors' conclusions

We found FABA/ICS as required is clinically effective in adults and adolescents with mild asthma. Their use instead of FABA as required alone reduced exacerbations, hospital admissions or unscheduled healthcare visits and exposure to systemic corticosteroids and probably reduces adverse events. FABA/ICS as required is as effective as regular ICS and reduced asthma‐related hospital admissions or unscheduled healthcare visits, and average exposure to ICS, and is unlikely to be associated with an increase in adverse events.

Further research is needed to explore use of FABA/ICS as required in children under 12 years of age, use of other FABA/ICS preparations, and long‐term outcomes beyond 52 weeks.

Keywords: Adolescent, Adult, Child, Humans, Adrenal Cortex Hormones, Adrenal Cortex Hormones/administration & dosage, Adrenergic beta-2 Receptor Agonists, Adrenergic beta-2 Receptor Agonists/administration & dosage, Anti-Asthmatic Agents, Anti-Asthmatic Agents/administration & dosage, Asthma, Asthma/drug therapy, Beclomethasone, Beclomethasone/administration & dosage, Budesonide, Budesonide/administration & dosage, Disease Progression, Drug Combinations, Formoterol Fumarate, Formoterol Fumarate/administration & dosage, Hospitalization, Hospitalization/statistics & numerical data, Nebulizers and Vaporizers, Prednisolone, Prednisolone/administration & dosage, Quality of Life, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Terbutaline, Terbutaline/administration & dosage

Plain language summary

Combination fixed‐dose beta agonist and steroid inhaler as required for adults or children with mild asthma

Background

Asthma is the most common respiratory illness. Many people with asthma have mild asthma, but still remain at risk of severe asthma exacerbations, which often result in the use of oral steroids. Mild asthma is commonly treated with preventative inhalers, which contain a steroid used to reduce inflammation in the airways, and with reliever inhalers, which relax the muscles of the airways causing quick relief of asthma symptoms. Combination inhalers contain both the preventative steroid and the reliever, simplifying treatment and ensuring steroids are always given alongside the immediate relief of symptoms.

Review question

We examined the findings of clinical trials to assess the use of combination inhalers in the treatment of mild asthma when taken on an as‐needed, symptom‐driven basis.

Study characteristics

We searched for studies up to March 2021. Results were collected from six studies which compared use of a combination inhaler used on an as‐needed basis with either as‐needed reliever‐only therapy or daily treatment with a low dose preventative inhaler.

Key findings

We found that combination inhalers used as‐needed when compared with reliever‐only treatment reduced severe exacerbations requiring tablet steroids and rates of emergency admission to hospital with asthma symptoms. Differences in other measures relating to symptom control and lung function were too small to be clinically important. Rates of severe exacerbations were similar between patients on daily preventative steroid inhalers and those using combination inhalers as‐needed. People using combination inhalers had lower rates of hospital admission and lower total inhaled steroid dose, whilst the differences in lung function and asthma symptom control were not clinically significant.

This review found the use of combination inhalers used when the patient experiences asthma symptoms was beneficial in reducing severe exacerbations when compared to stand‐alone reliever therapy in mild asthma. In addition to this the use of combination inhalers used on an as‐needed basis was associated with a reduction in hospital admissions and total inhaled steroid dose when compared with regularly‐taken low dose preventative inhaler therapy.

Quality of the evidence

The studies which contributed data were well‐designed and robust, although two were open‐label (participants knew which treatment they were getting), with some potential for bias, so the evidence was generally of moderate‐to‐high quality.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. As‐required FABA/ICS inhalers compared to as‐required FABA inhalers for mild asthma.

| As‐required FABA/ICS inhalers compared to as‐required FABA inhalers for mild asthma | ||||||

| Patient or population: mild asthma Setting: community Intervention: as‐required FABA/ICS inhalers Comparison: as‐required FABA inhalers | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with as required FABA inhalers | Risk with as required FABA / ICS inhalers | |||||

| Asthma exacerbation requiring systemic steroid follow‐up: 52 weeks | 109 per 1,000 | 52 per 1,000 (40 to 68) | OR 0.45, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.60 | 2997 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH 1 2 | People with mild asthma treated with combined inhalers have substantially fewer exacerbations requiring systemic steroid than those treated with FABA alone. |

| Hospital admission, ED and urgent care visits follow‐up: 52 weeks | 34 per 1,000 | 12 per 1,000 (7 to 21) | OR 0.35, 95% CI 0.20 to 0.60 | 2997 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 3 | People with mild asthma treated with combined inhalers probably have substantially fewer exacerbations requiring hospital admission, ED attendance or urgent care visit than those treated with FABA alone. |

| Asthma control

follow‐up: 52 weeks Lower scores = better control. |

Mean baseline ACQ‐5 ranged from 1.1 to 1.61 | MD ‐0.15, 95% CI ‐0.20 to ‐0.10 | ‐ | 2859 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 2 | MCID for ACQ‐5 is 0.5. A third study reported no difference in asthma symptom scores between the two arms. |

| Inhaled steroid dose assessed with: Mean daily inhaled steroid dose, μg beclomethasone equivalent follow‐up: 52 weeks | The mean inhaled steroid dose was 18.7 μg beclomethasone | MD 76.50 μg beclomethasone higher (69.40 higher to 83.60 higher) | ‐ | 2554 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 2 | People with mild asthma treated with a combined inhaler have a higher daily inhaled steroid dose than those treated with a FABA alone. |

| Total systemic steroid dose assessed with: mg prednisolone total over 52 weeks follow‐up: 52 weeks | The mean total systemic steroid dose was 17.4 mg prednisolone | MD 9.90 mg prednisolone lower (19.38 lower to 0.42 lower); participants = 443) | ‐ | 443 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2 4 | Total systemic steroid dose was similar and small in both those given combined inhalers and those given FABA alone. |

| Adverse events follow‐up: 52 weeks | 486 per 1,000 | 437 per 1,000 (402 to 473) | OR 0.82 (0.71 to 0.95) | 3002 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 2 | Slightly fewer adverse events occurred in those taking combination inhalers compared with those taking FABA alone. |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ACQ‐5: asthma control questionnaire ‐5; CI: Confidence interval; ED: emergency department; FABA: fast‐acting beta₂‐agonist; ICS: inhaled corticosteroids; MCID: minimum clinically important difference; MD: mean difference; OR: Odds ratio; RCT: randomised controlled trial. | ||||||

|

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1 Upgraded as large effect (OR < 0.5) with fairly tight confidence intervals.

2 Downgraded as included an open label study.

3 Downgraded as based on a small number of events

4 Downgraded as based on one study with a relatively small number of participants.

Summary of findings 2. As‐required FABA/ICS inhalers compared to regular inhaled steroid for mild asthma.

| As‐required FABA/ICS inhalers compared to regular inhaled steroid for mild asthma | ||||||

| Patient or population: mild asthma Setting: community Intervention: as‐required FABA/ICS inhalers Comparison: regular inhaled steroid | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with regular inhaled steroid | Risk with as required FABA / ICS inhalers | |||||

| Exacerbations requiring systemic steroid follow‐up: 52 weeks | 81 per 1,000 | 65 per 1,000 (49 to 86) | OR 0.79 (0.59 to 1.07) | 8065 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | Exacerbations requiring systemic steroid occurred less frequently in those treated with as required combination inhalers than those treated with regular inhaled steroid, but the 95%CI includes no difference. |

| Hospital admission, ED and urgent care visits follow‐up: 52 weeks | 19 per 1,000 | 12 per 1,000 (8 to 17) | OR 0.63 (0.44 to 0.91) | 8065 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 3 | Fewer hospital admissions, ED attendances and urgent care visits occurred in those treated with as required combination inhalers compared with regular inhaled steroid. |

| Asthma control

assessed with: ACQ‐5,

follow‐up: 52 weeks Lower scores indicate better asthma control. |

The mean asthma control was ‐0.467 points, change from baseline | MD 0.12 points higher (0.09 higher to 0.15 higher) | ‐ | 7382 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | ACQ‐5 fell slightly more compared with baseline in those treated with regular inhaled steroid than those treated with combination inhalers. MCID for ACQ‐5 is 0.5 points. |

| Inhaled steroid dose assessed with: Mean daily dose in μg, beclomethasone equivalent follow‐up: 52 weeks | The mean inhaled steroid dose was 257.8 μg beclomethasone equivalent per day | (MD 154.51 μg/day lower (207.94 lower to 101.09 lower) | ‐ | 7180 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | Those treated with as required combination inhalers had a lower average daily inhaled steroid dose than those treated with a regular inhaled steroid. |

| Total systemic steroid dose assessed with: Mean cumulative dose of prednisolone over the course of the trial in mg follow up: 52 weeks | The mean total systemic steroid dose was 20.97 mg prednisolone | MD 7 mg prednisolone lower (13.97 lower to 0.03 lower) | ‐ | 1330 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | Total systemic steroid exposure was similar and low in those treated with regular inhaled steroid and those treated with as required combination inhalers. |

| Adverse events assessed with: Participants experiencing at least one adverse event follow‐up: 52 weeks | 493 per 1,000 | 482 per 1,000 (443 to 525) | OR 0.96 (0.82 to 1.14) | 8072 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | The proportion of participants experiencing at least one adverse event was similar in those treated with combination inhalers and those with regular inhaled steroid. |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ACQ‐5: asthma control questionnaire‐5; CI: Confidence interval; ED: emergency department; FABA: fast‐acting beta₂‐agonist; ICS: inhaled corticosteroids; MCID: minimum clinically important difference; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial; OR: Odds ratio. | ||||||

|

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1 Downgraded as included open label studies

2 Downgraded as heterogeneity between trials at low risk of bias in all domains and those at high risk in at least one domain

3 Downgraded as based on a relatively small number of events

Background

Description of the condition

Asthma is the most common chronic respiratory disease, affecting 350 million people worldwide; and it is potentially serious, claiming 400,000 lives per year (GBD Study 2017; GINA 2019). Asthma is recognised as a heterogeneous disease, but common symptoms include wheezing, shortness of breath, chest tightness and cough; these vary over time in their occurrence, frequency and intensity (GINA 2019). Asthma is a clinical diagnosis defined by the history of a constellation of respiratory symptoms that vary over time and in intensity, together with variable expiratory airflow limitation (GINA 2019). Asthma treatment broadly focusses on maintaining daily symptom control and preventing acute worsening of symptoms known as asthma attacks or 'exacerbations'.

The seriousness of asthma varies greatly and severe asthma has attracted significant interest from researchers. Asthma control is the extent to which features of asthma are observed in an individual or have been reduced by treatment. Asthma severity is assessed retrospectively from the level of treatment required to control symptoms and exacerbations (GINA 2019). Globally, prevalence of mild asthma is estimated to be between 45% and 70% of all patients diagnosed with the condition (Rabe 2004; Dusser 2007; Sadatsafavi 2010). Despite being labelled as having mild asthma, this group continues to have severe asthma attacks requiring oral steroids or hospital admission (Bloom 2018), and suffer asthma‐related deaths (Bergström 2008; RCP 2014). Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are the most effective preventer drug for adults in achieving overall treatment goals and reducing mortality (Suissa 2000). Intermittence of symptoms in this population often leads to poor inhaler adherence (Taylor 2014). Up to 90% of people with asthma do not take ICS regularly as prescribed (AIHW 2007). Poor adherence to preventer ICS is thought to be a main cause for an increase in risk of exacerbations in people with mild asthma (Engelkes 2015).

Description of the intervention

Preventers and relievers

There are over 30 different inhalers now approved for use in asthma. They are usually classified as preventers or relievers. Short‐acting beta‐agonists (SABA) have been used since the 1970s for rapid relief of asthma symptoms from bronchoconstriction. They lead to rapid improvement of symptoms but do not affect the underlying pathological process (Barnes 1999).

Taking daily preventer steroid inhalers should lead to better asthma control (Chauhan 2013). Adherence to ICS is often poor, however, for a variety of reasons including fear of side effects, costs and perceptions of asthma severity (Bender 2005). Increasing the daily dose of the preventer ICS therapy during the early phase of an acute exacerbation has also been studied as a way to treat the exacerbation without the need for systemic corticosteroids (Kew 2016), though a benefit from this approach has not been shown. These regimens still depend on the use of a preventer even when the patient feels well; and they are still affected by poor adherence rates (Beasley 2019).

Longer‐acting beta₂ agonists (LABA) are also available. They are generally used as preventer medication and are co‐prescribed with an ICS. Some LABAs have a rapid onset of action and will also rapidly relieve symptoms (Wallin 1993). In this review, we refer to any beta agonist (SABA or LABA) that has a quick onset of action as a fast‐acting beta₂‐agonist (FABA).

Fixed‐dose combination inhalers

A number of combination inhalers exist. These contain both a steroid and a beta₂ agonist in the same device, thus delivering both treatments at the same time. This has the advantages of simplifying an inhaler regimen and ensuring LABA therapy is not taken without ICS. This is important because use of a LABA without an ICS is associated with a significantly increased risk of asthma death (Nelson 2006). In some, but not all, combination inhalers, the LABA is also a FABA, making the inhaler potentially suitable for as‐required use.

Exacerbations or 'attacks' are thought to be precipitated by external triggers (viral, bacterial, allergen or irritants) leading to an enhanced type 2 inflammatory response in the asthmatic airways (Papi 2018). The prodrome preceding an attack would be a logical time to intervene, especially if these are infrequent. The rapid‐acting beta₂ agonist will act immediately on the smooth muscle to relieve airway narrowing and resultant symptoms. ICS are thought to work by suppressing the type 2 inflammation at the epithelial level (Barnes 2010). Pairing the ICS with the beta₂ agonist therapy, specifically at the time of increased symptoms, could lead to both symptomatic improvement and suppression of the underlying pathological process, and importantly decrease the risk of severe or life‐threatening events (Beasley 2019). In patients with moderate asthma not controlled on medium‐dose ICS or ICS/LABA, fixed‐dose ICS/FABA inhalers used as both maintenance and reliever therapy (MART) is effective in reducing risk of asthma attacks (Cates 2013), but these data cannot necessarily be extrapolated to mild asthma or to use of the combination inhaler as‐required, without its use also as regular maintenance therapy.

How the intervention might work

This review focuses on fixed‐dose combination ICS/fast‐acting beta₂ agonist taken as needed — i.e. both treatments in the same inhaler. This is now being considered as a replacement for prescribing people either a SABA or SABA and a separate ICS. The idea is that when people's symptoms are worse they will take their inhaler more often to get symptom relief from the bronchodilator (Wallin 1993); and they will also get more steroid to treat the underlying inflammation (Barnes 2010). This also has the possible benefit of simplification due to the use of a single inhaler as well as reduced issues with adherence, and may in effect titrate the amount of ICS delivered to the individual's symptomatology.

Why it is important to do this review

Several clinical trials of as‐required fixed‐dose combination inhalers have been reported in recent years, and have led to a significant change in an international guideline (GINA 2019), which now recommends fixed‐dose ICS/FABA as first‐line therapy for mild asthma, where the previous guideline recommended use of SABA only. As the majority of economic costs of asthma are related to regular prescribing of preventer medications in primary care (Mukherjee 2016), this recommendation has major cost implications, particularly for public health systems in low‐ to middle‐income countries. There is also the potential for important benefits in improving symptom control, reducing exposure to systemic corticosteroids and reducing admissions; the last of which is a major contributor to the economic burden of asthma (Mukherjee 2016). Therefore, an accurate assessment of these benefits using all available randomised clinical trial data is timely, with implications for millions of people with asthma worldwide.

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of single combined (fast‐acting beta₂‐agonist (FABA) plus an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS)) inhaler only used as needed in people with mild asthma.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) as well as cross‐over designs provided they included an appropriate washout period (a week or more) between interventions. We planned to include cluster‐randomised trials if the data had been or could be adjusted for clustering. We excluded trials of very short duration (an intervention of less than 12 weeks). We included studies reported in full text, those published as an abstract only and unpublished data.

Types of participants

We included adults and children (age 6 years and older) with a diagnosis of mild asthma as defined by GINA 2019: asthma that is well‐controlled with as‐needed controller medication alone, or with low‐intensity maintenance controller treatment. Where GINA definitions were not specified, review authors judged severity using baseline characteristics; an Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ) score less than or equal to 1.5 or an Asthma Control Test (ACT) score equal to or more than 16. We did not exclude participants based on non‐respiratory co‐morbidities, provided they also met the required definition for a diagnosis of asthma. We excluded participants with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), defined by GOLD 2020; and any physician diagnosis of pulmonary fibrosis, bronchiectasis, lung cancer or other respiratory co‐morbidity. To ensure that we only investigated patients with mild asthma, we excluded patients taking moderate‐dose ICS daily (defined as greater than or equal to 300 μg per day of beclomethasone equivalent) or higher‐dose ICS daily (defined as greater than or equal to 600 μg per day of beclomethasone equivalent for adults and children aged 12 years or older).

Types of interventions

We included studies comparing a single fixed‐dose ICS/FABA inhaler used as needed with at least one of the following comparators.

No treatment

Placebo

As‐required SABA

Regular ICS with as‐required SABA

Regular fixed‐dose combination ICS/LABA, with or without as‐required SABA

Regular fixed‐dose combination ICS/LABA with as‐required ICS/FABA

Separate comparisons were done comparing single fixed‐dose ICS/FABA against each of the comparators listed above. Fast‐acting beta₂ agonists include salbutamol (albuterol), terbutaline, and formoterol.

We did not consider studies investigating other asthma treatments: if required, they would suggest severe asthma. Including systemic corticosteroids, leukotriene inhibitors, inhaled long‐acting anti‐cholinergics, methylxanthines and monoclonal antibodies.

Types of outcome measures

We analysed the following outcomes in the review, but did not use them as a basis for including or excluding studies. Where possible we analysed outcomes at the 12‐month time point.

Primary outcomes

Exacerbations requiring systemic steroids.

Hospital admissions/emergency department or urgent care visits for asthma.

Measures of asthma control: in order of preference Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ), Asthma Control Test (ACT), symptom‐free days.

Secondary outcomes

Measures of lung physiology: in order of preference post‐bronchodilator FEV₁, post‐bronchodilator peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR), FeNO, then other measures.

Quality of life measures, preferably Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (AQLQ), then the Short Form 36 (SF‐36).

Adverse events/side effects.

Total inhaled steroid dose. We converted inhaled steroid doses to beclomethasone equivalents using the conversion described in Table 3.

Total systemic corticosteroid dose.

Mortality.

1. Inhaled steroid equivalents.

| Drug | Dose considered equivalent to 100 μg beclomethasone dipropionate | Conversion factor |

| Beclometasone | 100 | 1.0 |

| Beclometasone (extra fine particles) | 50 | 2.0 |

| Budesonide | 100 | 1.0 |

| Fluticasone propionate | 50 | 2.0 |

| Fluticasone furoate | 12.5 | 8.0 |

| Mometasone | 50 | 2.0 |

| Ciclesonide | 62.5 | 1.6 |

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We identified studies from searches of the following databases and trial registries.

Cochrane Airways Trials Register (Cochrane Airways 2019), via the Cochrane Register of Studies, all years to 19 March 2021.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in the Cochrane Library, via the Cochrane Register of Studies, all years to 19 March 2021.

MEDLINE Ovid SP 1946 to 18 March 2021 (searched 19 March 2021).

Embase Ovid SP 1974 to week 10 2021 (searched 19 March 2021).

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register (www.ClinicalTrials.gov).

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (apps.who.int/trialsearch).

We present the database search strategies in Appendix 1. The search strategy was developed in MEDLINE by the Cochrane Airways Information Specialist in collaboration with the authors, and then adapted for use in the other databases.

We searched all databases and trials registries from their inception to 19 March 2021, and we imposed no restriction regarding language or type of publication. We identified hand searched conference abstracts and grey literature through the Cochrane Airways Trials Register and the CENTRAL database.

Searching other resources

We checked the reference lists of all primary studies and review articles for additional references. We searched relevant manufacturers' websites for study information.

We searched on PubMed for errata or retractions from included studies published in full text on 30 March 2021.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We used Cochrane's Screen4Me workflow to help assess the search results. Screen4Me comprises three components: known assessments – a service that matches records in the search results to records that have already been screened in Cochrane Crowd and have been labelled as 'RCT' or 'Not an RCT'; the RCT classifier – a machine learning model that distinguishes RCTs from non‐RCTs; and, if appropriate, Cochrane Crowd (crowd.cochrane.org) – Cochrane's citizen science platform where 'the crowd' help to identify and describe health evidence. More detailed information about the Screen4Me components can be found in the following publications: McDonald 2017; Thomas 2017; Marshall 2018; Noel‐Storr 2018.

Following this initial assessment, four review authors (ST, FY, MG, AF) screened the titles and abstracts of the remaining search results independently using Rayyan (Ouzzani 2016), and coded them as 'retrieve' (eligible or potentially eligible/unclear) or 'do not retrieve', with each abstract being screened by at least two review authors. We retrieved the full‐text study reports of all potentially eligible studies and two review authors (two of ST, FY, RR, MG and AF) independently screened them for inclusion, recording the reasons for exclusion of ineligible studies. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or, if required, consulted a third person/review author (IC or TSCH). We identified and excluded duplicates and collated multiple reports of the same study so that each study, rather than each report, was the unit of interest in the review. We recorded the selection process in sufficient detail to complete a PRISMA flow diagram and 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table (Moher 2009). Ouzzani 2016.

Data extraction and management

We used a data collection form which had been piloted on at least one study in the review for study characteristics and outcome data. Two review authors out of FY, RR, PW, EOB, SR and MG extracted the following study characteristics from each included study.

Methods: study design, total duration of study, details of any 'run‐in' period, number of study centres and location, study setting, withdrawals and date of study.

Participants: N, mean age, age range, gender, severity of condition, diagnostic criteria, baseline lung function, smoking history, inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria.

Interventions: intervention, comparison (including types and doses of beta agonist and corticosteroid), concomitant medications, prior medications and excluded medications.

Outcomes: primary and secondary outcomes specified and collected, and time points reported.

Notes: funding for studies and notable conflicts of interest of trial authors.

Two review authors (out of FY, RR, PW, EOB, SR and MG) independently extracted outcome data from included studies. We noted in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table if outcome data were not reported in a usable way. We resolved disagreements by discussion or by involving a third person/review author (IC or TSCH) to reach consensus. One review author (IC) transferred data into the Review Manager 5 file (Review Manager 2014). We double‐checked that data were entered correctly by comparing the data presented in the systematic review with the study reports. A second review author (TSCH) spot‐checked study characteristics for accuracy against the study report.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (SR, GH) assessed risk of bias independently for each study using the criteria outlined in version 5.1 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved any disagreements by discussion or by involving another author (IC or TSCH). We assessed the risk of bias according to the following domains.

Random sequence generation

Allocation concealment

Blinding of participants and personnel

Blinding of outcome assessment

Incomplete outcome data

Selective outcome reporting

Other bias

We judged each potential source of bias as high, low or unclear risk and provide a quote from the study report together with a justification for our judgement in the 'Risk of bias' table. We summarised the 'Risk of bias' judgements across different studies for each of the domains listed. We considered blinding separately for different key outcomes where necessary (e.g. for unblinded outcome assessment, risk of bias for all‐cause mortality may be very different than for a patient‐reported pain scale). Where information on risk of bias related to unpublished data or correspondence with a trialist, we noted this in the 'Risk of bias' table.

When considering treatment effects, we took into account the risk of bias for the studies that contribute to that outcome.

Assessment of bias in conducting the systematic review

We conducted the review according to this published protocol and justified any deviations from it in the 'Differences between protocol and review' section of the review.

Measures of treatment effect

We analysed dichotomous data as odds ratios (OR) or (where appropriate) rate ratios (RR) and continuous data as the mean difference (MD).We planned to use the standardised mean difference (SMD) to combine trials that measured the same outcome but used different methods. If data from rating scales were combined in a meta‐analysis, we ensured they were entered with a consistent direction of effect (e.g. lower scores always indicate improvement).

We undertook meta‐analyses only where this is meaningful: that is, if the treatments, participants and the underlying clinical question were similar enough for pooling to make sense.

We described skewed data narratively (for example, as medians and interquartile ranges for each group).

Where multiple trial arms were reported in a single study, we included only the relevant arms. If two comparisons (e.g. drug A versus placebo and drug B versus placebo) were combined in the same meta‐analysis, we either combined the active arms or halved the control group to avoid double‐counting.

If adjusted analyses were available (ANOVA or ANCOVA), we used these as a preference in our meta‐analyses. If both change from baseline and endpoint scores were available for continuous data, we used change from baseline unless there was low correlation between measurements in individuals. If a study reported outcomes at multiple time points, we used 12 months preferentially, with three months as a 'second choice'.

We used intention‐to‐treat (ITT) or 'full analysis set' analyses where they were reported (i.e. those where data had been imputed for participants who were randomly assigned but did not complete the study) instead of completer or per protocol analyses

Unit of analysis issues

For outcomes involving event counts where participants may have had multiple events (exacerbations, hospitalisations) and three or 12 month incidence rates were available, we used events primarily as the unit of analysis rather than participants. For other dichotomous outcomes and where incidence rate ratios were not available, we used participants, rather than events, as the unit of analysis (i.e. number of children admitted to hospital, rather than number of admissions per child).

Dealing with missing data

We contacted investigators or study sponsors in order to verify key study characteristics and obtain missing numerical outcome data where possible (e.g. when a study was identified as an abstract only). When this was not possible, and the missing data were thought to introduce serious bias, we took this into consideration in the GRADE rating for affected outcomes.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We used the I² statistic to measure heterogeneity among the studies in each analysis. When we identified substantial heterogeneity we reported it and planned to explore the possible causes by prespecified subgroup analysis.

We defined substantial heterogeneity using the following ranges from Higgins 2019:

0% to 40%: might not be important;

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity;

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity;

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity

Assessment of reporting biases

Had we been able to pool more than 10 studies, we planned to create and examine a funnel plot to explore possible small‐study and publication biases.

Data synthesis

We performed meta‐analysis using RevMan Web. We used a random‐effects model and performed a sensitivity analysis with a fixed‐effect model.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to carry out the following subgroup analyses.

Adults and adolescents versus children (i.e. 12 years and over versus under 12 years) in keeping with GINA 2019 definitions

High versus low eosinophil counts (for trials where this was reported, using the trialists' definition of high and low)

High versus low FeNO (where reported, using the trialists' definition of high and low)

By inhaler component drugs (i.e. by each inhaled steroid drug and by short‐ or long‐acting beta agonist)

We planned to use the following outcomes in subgroup analyses.

Exacerbations requiring oral steroid

Hospital admissions/emergency department or urgent care visits for asthma

Measures of asthma control

For this review, we did not identify studies that would allow such subgroup analyses.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to carry out sensitivity analyses, removing the following from the primary outcome analyses.

Trials deemed at high risk of bias in at least one domain

Cross‐over (as opposed to parallel group) trials

Trials in which asthma severity is not explicitly stated, but only derived from baseline characteristics

For this review, only the first sensitivity analysis was possible. We compared the results from a fixed‐effect model with the random‐effects model.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We created 'Summary of findings' tables using the following outcomes.

Exacerbations requiring systemic steroids

Hospital admissions/emergency department or urgent care visits for asthma

Asthma control, preferably measured by the Asthma Control Questionnaire

Inhaled steroid dose

Total systemic steroid dose

Adverse events

We used the five GRADE considerations (risk of bias; consistency of effect; imprecision; indirectness; and publication bias) to assess the certainty of a body of evidence as it relates to the studies that contributed data for the prespecified outcomes. We used the methods and recommendations described in Section 8.5 and Chapter 12 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2019), using GRADEpro software (GRADEpro GDT). We justified all decisions to downgrade the certainty of studies using footnotes and we made comments to aid the reader's understanding of the review where necessary.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

We identified 14,045 records in our literature search conducted in December 2019: 6597 records were removed as duplicates; 108 were excluded by Cochrane Crowd Known Assessments; and 1490 by the Cochrane RCT classifier. We excluded a further 5526 records on the basis of title and abstract. An additional search in March 2021 identified a further 612 records, 257 of which were removed as duplicates. A further 17 were removed by Cochrane Crowd Known Assessments and 78 by the RCT classifier. From the remaining 260 records, two new ongoing studies were identified as well as 10 new references to studies that had already been included. The literature search is summarised in Figure 1.

1.

Included studies

Six studies met our inclusion criteria (Characteristics of included studies). Four of those (Novel START, PRACTICAL, SYGMA 1 and SYGMA 2) were large studies from the same research group and we identified multiple records referring to each of these studies.There was one record for Haahtela 2006, a peer‐reviewed journal article. A further study (Tanaka 2017) was only mentioned in a brief conference abstract. The authors of this abstract did not respond to requests for further information.

Two studies (SYGMA 1 and SYGMA 2) included children aged 12 and over as well as adults. The other four studies included adults only. We did not identify any trial that accepted participants under the age of 12. A total of 9657 participants were included in the five trials included in the meta analysis. There were a further 28 participants in Tanaka 2017.

No trials compared as‐required combination inhalers with no treatment, placebo or regular combination inhalers.

As‐required combination inhaler compared with as‐required fast‐acting beta agonist (FABA)

Three studies (SYGMA 1, Novel START and Haahtela 2006) compared an as‐required combined inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) and fast‐acting beta‐agonist (FABA) inhaler with an as required beta‐agonist. Both SYGMA 1 and Novel START used budesonide 200 μg with formoterol 6 μg as the combination inhaler. The beta‐agonist was terbutaline (0.5 mg per puff) in SYGMA 1 and salbutamol (2 puffs of 100 μg each) in Novel START. Haahtela 2006 compared as‐required combined budesonide (160 μg) and formoterol (4.5 μg) with as‐required formoterol (4.5 μg).

As‐required combination inhaler compared with regular inhaled steroid plus as required fast‐acting beta agonist (FABA)

Five studies compared an as‐required FABA/ICS combination inhaler versus regular inhaled steroid plus an as‐required beta‐agonist. SYGMA 1, SYGMA 2, Novel START and PRACTICAL all compared the combination of budesonide 200 μg and formoterol 6 μg with regular budesonide 200 μg twice daily. The as‐required beta‐agonist given with the regular budesonide was salbutamol (200 μg) in Novel START and terbutaline (500 μg) in the other three studies. Tanaka 2017 compared budesonide 320 μg with formoterol 9 μg as required with regular budesonide 160 μg once daily. It was not stated whether or not those receiving regular budesonide in this study also got an as‐required beta‐agonist.

Excluded studies

We examined a large number (N = 293) of full‐text records as our initial search identified many records with a title but no abstract (see Characteristics of excluded studies). The main reason for excluding records at this stage was that the study did not include an arm with participants treated on a purely as‐required basis with a combination inhaled steroid and rapid acting beta‐agonist inhaler. Such studies often included a regular dose of the combination inhaler in addition to as‐required doses in the intervention arm or delivered the beta‐agonist and inhaled steroid using separate devices. Thirty‐eight records were excluded as the study enrolled participants with moderate or severe asthma and we were not able to identify a subgroup with mild asthma from the study. Twenty‐seven studies looked at interventions lasting less than 12 weeks. Many of these studies would also have been excluded for lack of an appropriate intervention arm. Seventeen studies were excluded as the only combination inhaler used contained a beta‐agonist that was not fast‐acting, for example, salmeterol. All of these studies also lacked an appropriate intervention arm. Other records were excluded because they were review articles or correspondence to journals, not describing original studies (21 records), or because they described studies without randomisation (three records).

We identified two ongoing studies that would potentially meet our inclusion criteria (see Characteristics of ongoing studies). ACTRN12620001091998 2020 will compare as‐required salbutamol with as‐required budesonide‐formoterol in children aged 5 to 15 years, but as of October 2020, had yet to start recruiting. NCT04215848 2020 is comparing budesonide‐formoterol with regular budesonide in adults and scheduled to complete in late 2021.

Risk of bias in included studies

We assessed risk of bias using the Cochrane 'Rrisk of bias' tool from Higgins 2011. The revised 'RoB 2' tool from Higgins 2019 was not in widespread use at the time our protocol was written. The 'Risk of bias' assessments are summarised in Figure 2.

2.

'Risk of bias' summary review

Allocation

We did not have enough information to assess the allocation and randomisation procedures in Tanaka 2017, and therefore marked it at uncertain risk of bias in this domain. The other studies were felt to be at low risk.

Blinding

Novel START ,PRACTICAL and Tanaka 2017 were all open‐label studies and were therefore judged at high risk of bias in these domains. The other studies were judged at low risk of bias.

Incomplete outcome data

Tanaka 2017 had an 18% dropout rate with a suspicion that dropout was related to treatment allocation, so was judged at high risk of attrition bias. We felt we had insufficient information on dropout in Haahtela 2006 and so rated it as at unclear risk of attrition bias. The other studies were felt to be low risk in this domain.

Selective reporting

We judged Tanaka 2017 to be at high risk of selective reporting bias on the limited and vague details in the conference abstract. Without an identified published protocol, it was unclear whether there was any selective reporting in the Haahtela 2006 study. The other studies all had published protocols and we were able to confirm that the reported outcomes matched the protocols.

Other potential sources of bias

We did not identify any other potential sources of bias in the included studies. It should be noted that four of the RCTs contributing data were funded by AstraZeneca.

Effects of interventions

All outcomes discussed are at 52 weeks unless otherwise stated. For an overview of the data and judgements on the certainty see Table 1 and Table 2.

As‐required combination inhalers compared with as‐required fast‐acting beta‐agonists (FABA)

Exacerbations requiring systemic steroids

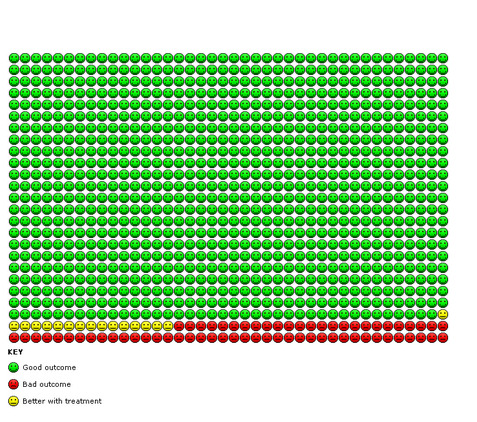

We found evidence from two trials (Novel START, SYGMA 1) that compared with as‐required beta‐agonists alone, as‐required FABA/ICS significantly reduced the number of asthma exacerbations requiring systemic steroid over a 52‐week period (odds ratio (OR) 0.45, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.34 to 0.60; participants = 2997, high‐certainty evidence, Figure 3Analysis 1.1). In the control group 109 people out of 1000 had exacerbations requiring systemic steroids over 52 weeks, compared to 52 (95% CI 40 to 68) out of 1000 for the active treatment group (Figure 4).

3.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: As required fixed dose combination inhaler versus as required short acting beta agonist, Outcome 1: Asthma exacerbations requiring systemic steroid

4.

In the FABA as required group, 109 people out of 1000 had exacerbations requiring systemic steroids over 52 weeks, compared to 52 (95% CI 40 to 68) out of 1000 for the FABA/ICS as required group.

Data from the same two studies showed an overall reduction in the annual exacerbation rate (Rate ratio 0.41, 95% CI 0.30 to 0.55; participants = 2997, Analysis 1.2). The third study that looked at this comparison (Haahtela 2006) did not record exacerbation rates or numbers.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: As required fixed dose combination inhaler versus as required short acting beta agonist, Outcome 2: Annual exacerbation rate

Hospital admissions/emergency department or urgent care visits for asthma

We found a reduction in the odds of hospital admission or emergency department or urgent care visit for asthma in participants given as‐required FABA/ICS compared with as‐required short‐acting beta‐agonists (SABA) alone (OR 0.35, 95% CI 0.20 to 0.60; participants = 2997, low‐certainty evidence, Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: As required fixed dose combination inhaler versus as required short acting beta agonist, Outcome 3: Exacerbations requiring hospital admission or emergency department / urgent care visit

Measures of asthma control

Three studies in this area reported measures of asthma control. Haahtela 2006 reported no difference in asthma symptom scores between the two arms. Novel START reported slightly lower ACQ‐5 scores (with lower scores indicating better asthma control) at some, but not all time points in the study and the differences were less than the typical minimal clinically important difference (MCID) of 0.5. SYGMA 1 reported slightly better improvements from baseline in ACQ‐5 in the as‐required FABA/ICS group compared with the as‐required SABA alone group, but again not reaching the point of clinical significance. The combined change from baseline scores and endpoint scores at longest follow‐up favoured as‐required FABA/ICS, but did not exceed the MCID (MD ‐0.15, 95% CI ‐0.20 to ‐0.10; participants = 2859, moderate‐certainty evidence, Analysis 1.4). The number of "electronically recorded weeks with well controlled asthma" were slightly higher in the as‐required FABA/ICS group in SYGMA 1 compared with as‐required SABA.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: As required fixed dose combination inhaler versus as required short acting beta agonist, Outcome 4: ACQ‐5

Measures of lung function

The three studies captured data on pre bronchodilator FEV1 (rather than post bronchodilator). In two studies (Haahtela 2006 and SYGMA 1), there was a larger increase in FEV1 on treatment compared with baseline on as‐required FABA/ICS compared with as‐required SABA (MD 64.03 mL, 95% CI 27.49 to 100.57; participants = 2596, Analysis 1.5). This difference is less than the MCID for FEV1 of about 100 mL. Novel START reported no statistically significant difference in FEV1 between as‐required FABA/ICS and as‐required SABA at any time point.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: As required fixed dose combination inhaler versus as required short acting beta agonist, Outcome 5: FEV1 change from baseline

SYGMA 1 found a smaller drop in both morning and evening peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR) in the as‐required FABA/ICS group compared with the as‐required SABA group. The magnitude of the differences was small at around 10 to 12 L/minute. The other studies did not report PEFR.

Novel START reported a 17% reduction in mean FeNO at 52 weeks in the as‐required FABA/ICS group compared to as‐required SABA using a ratio of geometric means due to skew (ratio of geometric means 0.83, 95% CI 0.75 to 0.92; participants = 387, Analysis 1.6). Similarly, Haahtela 2006 showed a bigger decrease in FeNO from baseline to treatment in those treated with as‐required FABA/ICS compared with as‐required SABA (MD ‐15.50 parts per billion (ppb), 95% CI ‐23.39 to ‐7.61; participants = 93, Analysis 1.7). SYGMA 1 did not collect FeNO data.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1: As required fixed dose combination inhaler versus as required short acting beta agonist, Outcome 6: FeNO [ppb]

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1: As required fixed dose combination inhaler versus as required short acting beta agonist, Outcome 7: FeNO change from baseline

Quality of life measures

Asthma quality of life questionnaire (AQLQ) scores were reported in SYGMA 1, but only available in graphical form. AQLQ did not differ between any of the arms by a clinically significant amount at any time point. The other two trials did not report quality of life data.

Adverse events

We did not find a clear difference in serious adverse events in the three trials reporting this outcome, although events were infrequent and confidence intervals wide (OR 1.31, 95% CI 0.50 to 3.46; participants = 3095, Analysis 1.8). In the two trials reporting all adverse events, the odds of an adverse event were about 18% lower in the as‐required FABA/ICS group compared with as‐required SABA (OR 0.82, 95% CI 0.71 to 0.95; participants = 3002,moderate‐certainty evidence, Analysis 1.9).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1: As required fixed dose combination inhaler versus as required short acting beta agonist, Outcome 8: Serious adverse events

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1: As required fixed dose combination inhaler versus as required short acting beta agonist, Outcome 9: All adverse events

Total inhaled steroid dose

The daily inhaled steroid dose was unsurprisingly higher in the as‐required FABA/ICS group than the as‐required SABA group. It appears that some participants in the as‐required SABA arm of SYGMA 1 did receive inhaled steroids and data were provided that is displayed in Analysis 1.10 (MD 77 μg beclomethasone equivalent/day, 95% CI 69 to 84; participants = 2554). Haahtela 2006 did not report daily inhaled steroid doses but we estimate these to be around 130 μg beclomethasone equivalent in the as‐required FABA/ICS group based on the average weekly number of as required medication doses. It does not appear that the as‐required SABA arm in Haahtela 2006 or Novel START had any inhaled steroid exposure.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1: As required fixed dose combination inhaler versus as required short acting beta agonist, Outcome 10: Daily inhaled steroid dose

Total systemic corticosteroid dose

Only Novel START reported systemic corticosteroid doses. These did not differ between the as‐required FABA/ICS and as required SABA arms (Analysis 1.11). The majority of participants in both arms did not receive systemic steroids.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1: As required fixed dose combination inhaler versus as required short acting beta agonist, Outcome 11: Total systemic corticosteroid dose

Mortality

We found no difference in mortality between as required FABA/ICS and as required SABA (Analysis 1.12), however this is based on a single death in the three studies (in an as‐required FABA/ICS arm) so we have very low confidence in the precision of this result.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1: As required fixed dose combination inhaler versus as required short acting beta agonist, Outcome 12: Mortality

As‐required combination inhalers compared with regular inhaled steroids

Exacerbations requiring systemic steroids

We found evidence based on four studies (Novel START, PRACTICAL, SYGMA 1 and SYGMA 2) that the odds of an asthma exacerbation requiring systemic steroids were reduced in participants treated with as‐required FABA/ICS compared with regular ICS, but confidence intervals include no difference (OR 0.79, 95% CI 0.59 to 1.07; participants = 8065, low‐certainty evidence, Figure 5, Analysis 2.1). In the control group 81 people out of 1000 had exacerbations requiring systemic steroids over 52 weeks, compared to 65 (95% CI 49 to 86) out of 1000 for the active treatment group (Figure 6).

5.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Fixed dose combination inhaler as required versus regular inhaled steroid plus as required short acting beta agonist, Outcome 1: Number of exacerbations requiring systemic steroid

6.

In the regular ICS group 81 people out of 1000 had exacerbations requiring systemic steroids over 52 weeks, compared to 65 (95% CI 49 to 86) out of 1000 for the FABA/ICS as required group.

The annual rate of asthma exacerbations requiring systemic steroid was similar in both groups (rate ratio 0.90, 95% CIs 0.76 to 1.06, participants = 8065, Analysis 2.2). Tanaka 2017 reported that one participant discontinued the study because of an asthma exacerbation but otherwise does not give further information on exacerbation rates.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Fixed dose combination inhaler as required versus regular inhaled steroid plus as required short acting beta agonist, Outcome 2: Annual severe exacerbation rate

Hospital admissions/emergency department or urgent care visits for asthma

There were fewer exacerbations of asthma requiring either hospital admission or a visit to an emergency department or urgent care clinic in participants taking as‐required FABA/ICS compared with regular ICS (OR 0.63, 95% CI 0.44 to 0.91; participants = 8065,low‐certainty evidence, Analysis 2.3).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Fixed dose combination inhaler as required versus regular inhaled steroid plus as required short acting beta agonist, Outcome 3: Exacerbations requiring hospital admission or emergency department / urgent care visit

Measures of asthma control

Two studies (Novel START and PRACTICAL) reported ACQ‐5 at last trial visit and two studies (SYGMA 1 and SYGMA 2) reported change in ACQ‐5 from baseline. We combined these scores in Analysis 2.4. We found that analyses of these data showed a statistical advantage to regular ICS compared with as‐required FABA/ICS but the absolute differences were small and probably not clinically significant (MD 0.12, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.15; participants = 7382). The MCID in ACQ‐5 is around 0.5 points.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Fixed dose combination inhaler as required versus regular inhaled steroid plus as required short acting beta agonist, Outcome 4: ACQ‐5

Tanaka 2017 reported no difference in mean ACQ‐5 scores at 4, 8, 16 and 24 weeks between regular ICS and as‐required FABA/ICS without giving values for mean ACQ‐5 score.

Measures of lung function

Two studies (PRACTICAL and Novel START) reported (probably pre‐bronchodilator) FEV1 at 52 weeks. We found no difference between as‐required FABA/ICS and regular ICS for this outcome (MD ‐0.01 L 95% CIs ‐0.11 to 0.09, participants = 1199, Analysis 2.5). SYGMA 1 and SYGMA 2 reported the change in FEV1 from baseline. FEV1 was 38 mL lower in the as‐required FABA/ICS group compared with regular ICS (MD ‐37.68 mL, 95% CIs ‐68.19 to ‐7.17; participants = 6287, Analysis 2.6). This finding is below the MCID in FEV1 of around 100 mL. Tanaka 2017 reported no difference in mean change in FEV1 and FVC from baseline without giving absolute values or specifying whether they were pre or post bronchodilator.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Fixed dose combination inhaler as required versus regular inhaled steroid plus as required short acting beta agonist, Outcome 5: FEV1

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Fixed dose combination inhaler as required versus regular inhaled steroid plus as required short acting beta agonist, Outcome 6: FEV1 change from baseline

SYGMA 1 found that morning and evening PEFR increased slightly in the regular ICS group compared with baseline and fell slightly compared with baseline in the as‐required FABA/ICS group. The absolute differences between as‐required FABA/ICS and regular ICS in change in peak flow from baseline were small, less than 10 L/minute. The other studies did not report PEFR data.

Two studies (PRACTICAL and Novel START) reported data on FeNO. Both studies reported the ratio of geometric means due to skew in this outcome, which indicated that mean FeNO levels at 52 weeks were 13% higher in the as‐required FABA/ICS arm compared to the regular ICS arm (OR 1.13, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.20; participants = 1197, Analysis 2.7) .

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Fixed dose combination inhaler as required versus regular inhaled steroid plus as required short acting beta agonist, Outcome 7: FeNO [ppb]

Quality of life measures

Both SYGMA 1 and SYGMA 2 collected data on AQLQ but the findings were only available in graphical form. AQLQ scores were generally higher in the regular ICS arms compared with as‐required FABA/ICS but by less than the minimal clinically important difference of 0.5 points.

Tanaka 2017, Novel START and PRACTICAL did not report quality of life measures.

Adverse events

Serious adverse events occurred at similar rates in the as‐required FABA/ICS and regular ICS arms across four trials, although confidence intervals are wide (OR 1.14, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.57; participants = 8072, Analysis 2.8). We found similar odds of experiencing any adverse event in the two groups (OR 0.96, 95% CIs 0.82 to 1.14; participants = 8072, moderate‐certainty evidence, Analysis 2.9). Other than reporting a discontinuation due to an asthma exacerbation, Tanaka 2017 did not report adverse events.

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Fixed dose combination inhaler as required versus regular inhaled steroid plus as required short acting beta agonist, Outcome 8: Serious adverse events

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Fixed dose combination inhaler as required versus regular inhaled steroid plus as required short acting beta agonist, Outcome 9: All adverse events

Total inhaled steroid dose

We found that participants randomised to as‐required FABA/ICS received about 150 μg less ICS (beclomethasone equivalent) per day than those on regular ICS (MD ‐154.51 μg/day, 95% CI ‐207.94 to ‐101.09; participants = 7180; moderate‐certainty evidence, Analysis 2.10). Tanaka 2017 did not report data on ICS usage.

2.10. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Fixed dose combination inhaler as required versus regular inhaled steroid plus as required short acting beta agonist, Outcome 10: Daily inhaled steroid dose

Total systemic corticosteroid dose

Using data from two studies (PRACTICAL; Novel START), we found similar total systemic steroid exposure in the as‐required FABA/ICS and regular ICS groups (MD ‐7.00 mg prednisolone, 95% CI ‐13.97 to ‐0.03; participants = 1330, moderate‐certainty evidence, Analysis 2.11) The other three studies did not report systemic steroid doses. There were numerically fewer total days on systemic steroid in the as‐required FABA/ICS group compared with regular ICS in SYGMA 1 (465 versus 500 days). SYGMA 2 reported that those in the as‐required FABA/ICS and the regular ICS groups had the same median number of days on systemic steroids (six days). Tanaka 2017 did not report data on systemic steroid usage.

2.11. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Fixed dose combination inhaler as required versus regular inhaled steroid plus as required short acting beta agonist, Outcome 11: Total systemic corticosteroid dose

Mortality

There was no clear difference in the risk of death between as‐required FABA/ICS and regular ICS four studies (OR 0.63, 95% CI 0.12 to 3.25; participants = 8070, Analysis 2.12). This analysis is based on a small number of events and consequently has very broad confidence intervals. Tanaka 2017 didn't report information on mortality.

2.12. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Fixed dose combination inhaler as required versus regular inhaled steroid plus as required short acting beta agonist, Outcome 12: Mortality

Subgroup analyses

Our preplanned subgroup analyses were not possible, given the lack of studies covering these areas. In particular, we found no studies recruiting children (under 12 years) and included studies used the combination of formoterol and budesonide rather than other combination inhalers. We found little evidence of heterogeneity across the majority of outcomes studied. This is perhaps unsurprising as the bulk of the data came from studies carried out using similar methodology, led by one research group.

Sensitivity analyses

No cross‐over trials were identified, nor were there any included studies where the baseline asthma severity had to be implied from the baseline characteristics. Excluding the open‐label studies (Novel START and PRACTICAL, judged at high risk of bias due to lack of blinding) did not alter the direction of effect in any of the primary outcomes. Using a fixed‐effect model as opposed to a random‐effects one made no meaningful difference to the point estimates of the primary outcomes.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Of the six studies which met our inclusion criteria, four (Novel START, PRACTICAL, SYGMA 1 and SYGMA 2) dominated the results of the meta‐analyses. These were large randomised controlled trials from the same research group and included 9565 participants in total. Two studies (SYGMA 1 and SYGMA 2) included children aged 12 and over as well as adults. Two studies were open‐label (Novel START and PRACTICAL) and judged as high risk of bias in this domain, but all studies were otherwise of low risk of bias in other domains. In all four of these trials the fixed‐dose combination as‐required fast‐acting beta₂‐agonist/inhaled corticosteroids (FABA/ICS) was budesonide 200 μg and formoterol 6 μg in a dry powder formulation. Haahtela 2006 is a smaller study with 93 participants, conducted by a different research group. It also used budesonide/formoterol as the combination inhaler, again as dry powder formulation.

When compared with as‐required short‐acting beta2‐agonists (SABA) alone, as‐required fixed‐dose combination inhalers significantly reduced the number of asthma exacerbations requiring systemic steroids (odds ratio (OR) 0.45, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.34 to 0.60, Analysis 1.1), and reduced the annual exacerbation rate (rate ratio 0.41, 95% CI 0.30 to 0.55, Analysis 1.2), and the odds of an asthma‐related hospital admission or emergency department or urgent care visit (OR 0.35, 95% CI 0.20 to 0.60, Analysis 1.3). The reduction in exacerbations requiring systemic steroid is based on high‐certainty evidence from two clinical trials including 2997 participants. The certainty of the other outcomes is lower, particularly as they are based on relatively few events.

Compared with SABA alone, any changes in asthma control or spirometry, though favouring as required FABA/ICS, were small and less than the minimal clinically‐important differences. We did not find evidence of differences in asthma‐associated quality of life, total systemic corticosteroid dose or mortality. For other secondary outcomes as‐required FABA/ICS was associated with significant reductions in FeNO, a marker of exacerbation risk (Petsky 2016), by ‐11 to ‐15.5 ppb and of the odds of an adverse event (OR 0.82, 95% CI 0.71 to 0.95, Analysis 1.9), and with an increase in the daily inhaled steroid dose (mean difference (MD) 76.50 μg beclomethasone equivalent per day, 95% CI 69.40 to 83.60, Analysis 1.10).

When compared with regular maintenance use of inhaled corticosteroids, as‐required fixed‐dose combination inhalers did not lead to a significant difference in the odds ratio (OR 0.79, 95% CI 0.59 to 1.07, Analysis 2.1) or annual rate (rate ratio 0.90, 95% CIs 0.76 to 1.06, Analysis 2.2) of severe asthma exacerbations requiring systemic steroids, but did reduce the odds of an asthma‐related hospital admission or emergency department or urgent care visit (OR 0.63, 95% CI 0.44 to 0.91, Analysis 2.3). We have relatively low certainty in the precision of these estimates.

Compared with regular maintenance use of inhaled corticosteroids, any changes in asthma control, spirometry, peak flow rates, or asthma‐associated quality of life, though favouring regular ICS, were small and less than the minimal clinically‐important differences. As this review was limited to mild asthma, study participants generally had good asthma control and normal lung function and so it is not surprising that we found no major between intervention effects. We found evidence that adverse events, serious adverse events, total systemic corticosteroid dose and mortality were similar between groups, although deaths were rare, so confidence intervals for this analysis were wide. We found moderate‐certainty evidence from four trials involving 7180 participants that as‐required FABA/ICS was associated with less average daily exposure to inhaled corticosteroids than those on regular ICS (MD ‐154.51 μg/day, 95% CI ‐207.94 to ‐101.09, Analysis 2.10).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

We believe these studies are representative of adults with mild asthma in the real world, with broad inclusion criteria, with only two of the studies that contributed data requiring reversibility as an inclusion criterion, the others depending on self‐report of physician‐diagnosed asthma. Participants had mean age 36 to 43 years, a mild deficit in baseline lung function (pre‐bronchodilator FEV1 84% to 90%) and including current smokers (2.3% to 11% of participants), and those with a range of preceding annual exacerbation rates (5.5% to 22%). These results are therefore likely to be generalisable to populations with mild asthma in primary care.

Whilst numbers of exacerbations, annual severe exacerbation rates and severe adverse events were reported consistently between studies, other outcome measures including symptom scores, FeNO and lung function were not, and none of the included studies reported on quality of life outcomes. As we were unable to obtain single‐patient data we were unable to include a large randomised controlled trial (RCT) (Papi 2007), which included participants with a mixture of mild and moderate asthma. We also identified an unpublished trial presented only in a conference abstract, although this trial was small so unlikely to influence significantly the findings of the meta‐analyses.

There are a number of different preparations of fixed‐dose FABA/ICS, including pressurised meter dose inhaler formulations, but our search identified studies which used dry powder formulations of budesonide and formoterol only. The majority of studies which contributed data are produced by a single group of investigators, albeit as part of a multinational collaboration, and three of these are funded by a single pharmaceutical company.

Quality of the evidence

Using the GRADE system, we judged the certainty of the evidence per outcome for main comparisons – those related to rates of exacerbations – to be low (with the exception of exacerbations requiring systemic steroid in the as‐required FABA/ICS versus as‐required FABA comparison). This judgement may be a little harsh, as the results are based solely on relevant, well‐designed randomised clinical trials. Of the five trials that contributed data, two were open‐label, which has the potential to introduce biases in participant behaviour, such as seeking urgent care, and treatment outcomes such as reducing the threshold for prescribing systemic steroids, or affecting the reporting of adverse events. However, the methodological quality was otherwise good for the included trials, they were conducted in applicable populations, examining outcomes of direct relevance to participants, with low‐moderate heterogeneity across studies, and with consistent findings between studies, including between blinded and unblinded studies. It is unlikely that lack of blinding would be sufficient to explain the large magnitude of the observed differences on exacerbation rates between as‐required FABA/ICS and FABA alone. This is particularly so as the effect size observed was larger for reduction in exacerbations requiring hospital admission or urgent care visit, than for exacerbations requiring systemic corticosteroids, both in comparisons with SABA alone and in comparisons with maintenance steroids. Blinding would be unlikely to have a sizeable effect on other markers of lung function, though knowledge of treatment allocation is likely to affect symptom scores, which could be rated higher in those aware they are not receiving combination therapies.

Several of the outcomes, particularly in comparisons against as‐required SABA alone, were based on only one or two studies. Given the large trial sizes, good methodological quality and large effect size, we have a high degree of confidence in the benefits of as‐required FABA/ICS in reducing exacerbations compared with SABA alone, and in the evidence suggesting no difference between as‐required FABA/ICS and maintenance ICS in rates of exacerbations or adverse events. We have less confidence in comparative effects of as‐required FABA/ICS and SABA alone on FeNO or Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ‐5) as these are dependent on a single open‐label RCT. Due to the small number of included studies, a funnel plot was not feasible as a formal assessment of publication bias. However, our search strategy was comprehensive and rigorous, and our searches included conference abstracts and ongoing trials to find unpublished studies.

Potential biases in the review process

Our review adhered closely to the published protocol (Crossingham 2020). We were unable to identify data on quality of life or meta‐analyse lung function due to differences in data presentation between studies, and for the same reason we could analyse only severe adverse events rather than all adverse events for the comparison of as required FABA/ICS with regular ICS.

There remains the possibility that we may have failed to identify unpublished trials contributing positive or negative results, although we have searched available trial registries, and most relevant trials will have been conducted since the introduction of mandatory trial registration. We are aware of the potential for publication bias. We identified six trials meeting our prespecified inclusion criteria through comprehensive, systematic database searches, and all identified studies were reviewed independently by two review authors to minimise study selection bias or errors.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Our findings are in broad agreement with one previous meta‐analysis (Hatter 2021), which was conducted by the authors of the Novel START and PRACTICAL studies. The authors assessed their open‐label trials as of lower risk of bias than did our assessments, and their meta‐analysis considered only the comparison of as‐required FABA/ICS with regular ICS, and not the comparison against SABA alone. Both meta‐analyses found similar results, and similar magnitudes of effects for a range of outcomes including reduction in inhaled steroid dose and a slight increase in ACQ‐5, which was less than the: minimum clinically important difference (MCID), and no evidence of differences in rates of severe adverse events and mortality.

Both meta‐analyses found some evidence of a reduction in urgent care visits associated with as‐required FABA/ICS, though, due to differences in methodology and the statistical analysis selected, the two meta‐analyses differed in the detail. The current meta‐analysis found fewer exacerbations requiring hospital admission or urgent care visit with as‐required FABA/ICS compared with maintenance ICS, whilst Hatter 2021, using Peto Odds Ratios, reported no difference in this outcome or in hospitalisation rates. However the upper limits of their confidence intervals were close to unity and their findings would be compatible with significant decrease in these outcomes. Moreover Hatter 2021 reported a significant reduction in emergency department visits with as‐required FABA/ICS (Peto OR 0.65, 95%CI 0.43 to 0.98), consistent with evidence of a reduction in urgent care visits.