Abstract

Background:

Canadian federal restrictions on food marketing to children (children’s marketing) were proposed in 2016 as Bill S-228, the Child Health Protection Act, which subsequently died on the parliamentary table. This study quantified the interactions (meetings, correspondence and lobbying) related to Bill S-228 and children’s marketing by different stakeholders with the federal government.

Methods:

Interactions between all stakeholders and government related to children’s marketing and Bill S-228 (Sept. 1, 2016–Sept. 30, 2019) were analyzed. These included the “Meetings and correspondence on healthy eating” database, detailing interactions between stakeholders and Health Canada related to nutrition policies; and Canada’s Registry of Lobbyists, reporting activities of paid lobbyists. We categorized the interactions by stakeholder type (industry, nonindustry and mixed), and analyzed the number and type of interactions with different government offices.

Results:

We analyzed 139 meetings, 65 lobbying registrants, 215 lobbying registrations and 3418 communications related to children’s marketing and Bill S-228. Most interactions were from industry stakeholders, including 84.2% of meetings (117/139), 81.5% of lobbying registrants (53/65), 83.3% of lobbying registrations (179/215) and 83.9% of communications (2866/3418). Most interactions (> 80%) in the highest-ranking government offices were by industry.

Interpretation:

Industry stakeholders interacted with government more often, more broadly and with higher ranking offices than nonindustry stakeholders on subjects related to children’s marketing and Bill S-228. Although further research is needed to analyze the nature of the discourse around children’s marketing, it is apparent that industry viewpoints were more prominent than those of nonindustry stakeholders.

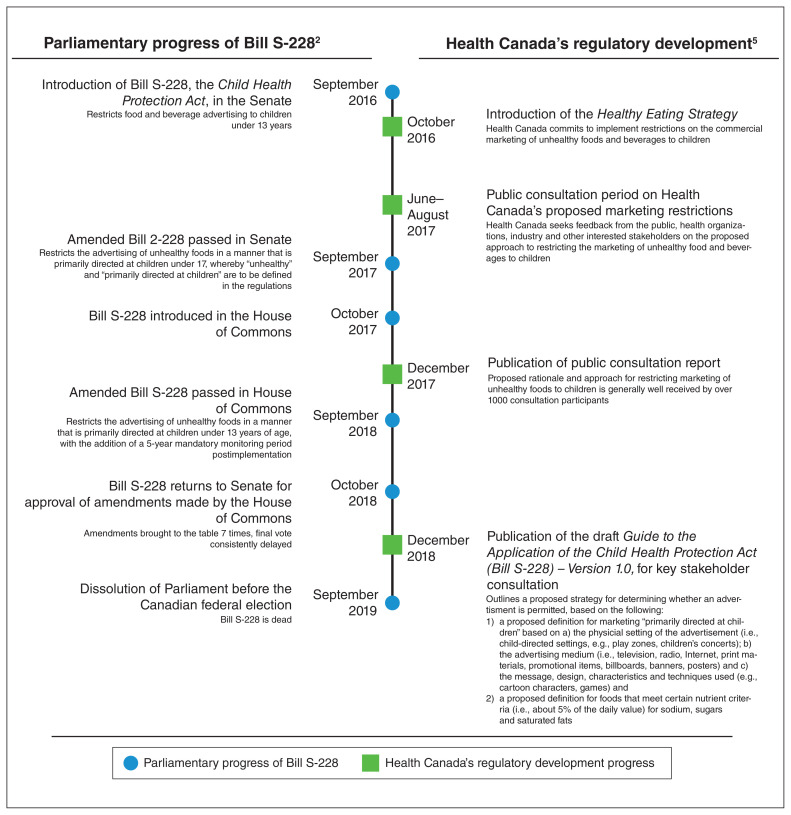

Marketing unhealthy food products to children (“children’s marketing,” hereafter) is an important factor in influencing children’s dietary habits and preferences, with consequences for childhood overweight and obesity.1 To help mitigate these effects, Bill S-228, the Child Health Protection Act, was proposed in the Senate of Canada in September 2016, aiming to federally restrict children’s marketing.2 This proposal was supported by Health Canada’s Healthy Eating Strategy, nutrition-related policies aimed at making the healthier choice the easier choice for Canadians.3 Parallel to Bill S-228’s parliamentary progress, Health Canada was developing regulations for implementing the new legislation, and a strategy for monitoring its impact.4 Details of Bill S-228’s parliamentary progress and Health Canada’s regulatory development process are shown in Figure 1. In September 2019, the bill died on the parliamentary table before the federal election,5,6 despite seemingly strong support from parliamentarians and the public and an apparent policy window (window of opportunity for policy change).7,8 Following his re-election, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau identified children’s marketing restrictions as a public health priority for Canada in his Mandate Letter to the Minister of Health (published late 2019), suggesting the opening of another children’s marketing policy window.9

Figure 1:

Timeline of policy events for Bill S-228: the Child Health Protection Act and the development of Health Canada’s proposed related regulations.2,5

The development of nutrition-related policies is influenced by many factors, such as scientific evidence, stakeholders, public support and political will.10,11 Stakeholders employ powerful strategies — not dissimilar to those of the tobacco industry — to influence policy-makers, and understanding these influences is critical to the development of unbiased nutrition policies.12–16 Canadian research has shown that industry stakeholders are actively attempting to influence the nutrition-related policies articulated in the Healthy Eating Strategy.12 However, the extent to which stakeholders influenced the development of Canada’s restrictions on children’s marketing, specifically, is unknown. With the reprioritization of marketing restrictions occurring so closely after Bill S-228, as stated in a CMAJ commentary, “How this bill came to die, despite overwhelming support for it, is worthy of attention if we are to protect the health of Canadian children in the future.”6 Understanding the influence of stakeholders during Bill S-228’s policy window will help elucidate reasons for the bill’s failure and support the development of new restrictions. 6 This study aimed to quantify the meetings, correspondence and lobbying that occurred related to children’s marketing and Bill S-228, and the type of stakeholders and government involved.

Methods

Study design and data sources

This study presents a quantitative descriptive analysis of the only 2 sources of publicly available data on the interactions that occurred between stakeholders and government related to children’s marketing and Bill S-228 from September 2016 to September 2019.

Health Canada’s “Meetings and correspondence on healthy eating” database

Health Canada developed a “Meetings and correspondence on healthy eating” database as part of the Government of Canada’s Regulatory Transparency and Openness Framework. 17,18 The database contains detailed information and content of all meetings, correspondence and documents (“meetings,” hereafter) that were shared between Health Canada and stakeholders (e.g., citizens, industry, nongovernmental organizations, professionals, academia and professional associations), related to the Healthy Eating Strategy, including the development of children’s marketing restrictions (i.e., Bill S-228).18 Meetings between Health Canada and other levels of Canadian or foreign governments and individuals or experts representing themselves are excluded from this database.18

The Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying’s Registry of Lobbyists

The Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying requires that, by law, information on the activities of all paid lobbyists in Canada is entered into the Registry of Lobbyists.19 Lobbyists employed by government-relations firms (i.e., consultant lobbyists) must register all lobbying activities, whereas lobbyists communicating on behalf of their employer (i.e., in-house lobbyists) must register only if lobbying activities make up more than 20% of monthly duties.20 Volunteers and individuals lobbying on their own behalf need not register.20 The registry is publicly available online and for download on the open data website.19,21 Available data include lobbying registrations (information on every paid individual who registered to communicate with government, e.g., parliamentarians and civil servants), and monthly communication reports (reporting basic details about communications that occurred between lobbyists and government).21 Unlike in the Health Canada database, the contents of these communications are not disclosed.

Data extraction

The Health Canada database was searched in September 2019 and documents labelled by Health Canada with the subject “marketing to kids” were downloaded (excluding French duplicates). We extracted the stakeholder name, type of meeting (i.e., stakeholder- or Health Canada–initiated, as indicated in the database) and the Health Canada office involved into an Excel database (C.M.). As per research by Vandenbrink and colleagues, stakeholder type was assigned to meetings as either “industry” (i.e., any organization that could have a commercial interest, such as food companies, advertising companies, industry association), “nonindustry” (i.e., any organization with no commercial interest, such as public health or not-for-profit organizations), or “mixed” (i.e., meetings with industry and nonindustry stakeholders together, or unspecified stakeholders).12 All data were validated (C.M. in consultation with A.J.).

Lobbying registrations and monthly communication reports files were downloaded from the Registry of Lobbyists on Jan. 24, 2020. Lobbying registrations were analyzed for registrations that occurred between Sept. 1, 2016, and Sept. 30, 2019, while Bill S-228 was being considered. The subject matter details of registrations that occurred during this period were searched for topics related to Bill S-228 or children’s marketing using several keyword searches (e.g., “marketing to kids,” “Bill S-228,” “advertising restrictions”). The keywords were validated through cross-checking with the subject matter details (i.e., keywords) in the online registry to ensure all appropriate terms were captured. From the lobbying registrations found to be related to children’s marketing and Bill S-228, registrant ID number, registrant name, client name and the organization or corporation they represented were extracted into an Excel database (C.M.). Stakeholder type (i.e., industry or nonindustry) was assigned based on the client represented.

From the monthly communication reports, all communications registered from Sept. 1, 2016, to Sept. 30, 2019, associated with the previously identified registrant ID numbers were analyzed. From these communications, the name, position title, branch unit and government institution of the individuals that lobbyists met with were extracted into an Excel database (C.M.). For government institutions representing 1% or greater of all communications, the ranking of the government office with which a stakeholder communicated was categorized (Table 1), based on the individual’s role in government, using their registered position title and branch unit. All data were validated (C.M. in consultation with M.R.L.).

Table 1:

Categorization and rank of offices within the federal government

| Categories and rank of federal government offices* | Description and examples |

|---|---|

| Parliamentarians and their staff | Elected individuals or individuals designated by the prime minister for that parliamentary term, and staff working for those individuals, responsible to the political party in power |

| Prime Minister’s Office |

|

| Ministers and parliamentary secretaries |

|

| Ministerial staff |

|

| Members of Parliament, Senators and their staff |

|

| Civil servants | Nonpolitical staff (i.e., nonelected), responsible to the state (i.e., Canada) and not to the political party in power |

| Privy Council Office |

|

| Deputy ministers |

|

| Assistant deputy ministers |

|

| Other government officials |

|

Categories of federal government office are ranked in order of highest to lowest rank, within “Parliamentarians and their staff” and within “Civil servants”.

Statistical analysis

The number and proportion of meetings were calculated per stakeholder type (i.e., industry, nonindustry or mixed), per meeting type (i.e., stakeholder- or Health Canada–initiated), and per Health Canada office involved (e.g., Deputy Minister’s Office). The number and proportion of individual lobbying registrants and unique registrations were calculated by stakeholder type, as well as the mean number (and standard deviation [SD]) of communications that were reported by each individual registrant. The number and proportion of communications per government institution and per rank of government office were calculated by stakeholder type. All statistical analyses were completed using RStudio (Version 1.1.463) and Microsoft Excel software.

Ethics approval

All data were publicly available; ethics approval was not required.

Results

Stakeholder interactions from the Health Canada database

In summary, 84.2% of meetings (117/139) related to children’s marketing from the Health Canada database were from industry stakeholders, 13.7% (19/139) from nonindustry stakeholders and 2.2% (3/139) from mixed stakeholders (Table 2). Stakeholders initiated 73.4% (102/139) of all meetings; 81.2% (95/117) of industry meetings were stakeholder-initiated in comparison to 36.8% (7/19) of nonindustry meetings.

Table 2:

Meetings* related to marketing to kids from the Health Canada “Meetings and correspondence on healthy eating” database, summarized by meeting type and stakeholder type

| Meeting type | Industry stakeholders | Nonindustry stakeholders | Mixed stakeholders† | All stakeholders |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) of meetings,* summarized by meeting type | ||||

| Stakeholder-initiated meetings | 95 (93.1) | 7 (6.9) | 0 (0.0) | 102 (100.0) |

| Health Canada–initiated meetings | 22 (59.5) | 12 (32.4) | 3 (8.1) | 37 (100.0) |

| All meeting types | 117 (84.2) | 19 (13.7) | 3 (2.2) | 139 (100.0) |

| No. (%) of meetings,* summarized by stakeholder type | ||||

| Stakeholder-initiated meetings | 95 (81.2) | 7 (36.8) | 0 (0) | 102 (73.4) |

| Health Canada–initiated meetings | 22 (18.8) | 12 (63.2) | 3 (100.0) | 37 (27.6) |

| All meeting types | 117 (100.0) | 19 (100.0) | 3 (100.0) | 139 (100.0) |

The term “meetings” refers to any meetings, correspondence or documents in the Meetings database labelled with the subject “marketing to kids.”

Meetings were categorized as being from “mixed stakeholders” if they were meetings with industry and nonindustry stakeholders together, or the stakeholder was unspecified.

Overall, stakeholders most often met with the Assistant Deputy Minister’s Office (n = 51 meetings) and the Director General of the Food Directorate’s Office (n = 48) at Health Canada (Table 3). More than 65% of meetings in any Health Canada office (aside from 1 nonindustry meeting in the Director General of the Office of Nutrition Policy and Promotion’s office) were with industry, with all (16/16) of meetings in the Deputy Minister’s Office and 88.2% (45/51) in the Assistant Deputy Minister’s office being with industry.

Table 3:

Meetings* related to marketing to kids from the Health Canada “Meetings and correspondence on health eating” database, summarized by Health Canada office and stakeholder type

| Health Canada office | Industry stakeholders | Nonindustry stakeholders | Mixed stakeholders† | All stakeholders |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) of meetings,* summarized by Health Canada office | ||||

| Deputy Minister’s Office | 16 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 16 (100.0) |

| Assistant Deputy Minister’s Office | 45 (88.2) | 6 (11.8) | 0 (0.0) | 51 (100.0) |

| Director General’s Office, Food Directorate | 40 (83.3) | 6 (12.5) | 2 (4.2) | 48 (100.0) |

| Director General’s Office, Office of Nutrition Policy and Promotion | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (1.0) | 1 (100.0) |

| Food directorate | 13 (65.0) | 5 (25.0) | 2 (10.0) | 20 (100.0) |

| Office of Nutrition Policy and Promotion | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (100.0) |

| All offices | 117 (84.2) | 19 (13.7) | 3 (2.2) | 139 (100.0) |

| No. (%) of meetings,* summarized by stakeholder type | ||||

| Deputy Minister’s Office | 16 (13.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 16 (11.5) |

| Assistant Deputy Minister’s Office | 45 (38.5) | 6 (31.5) | 0 (0.0) | 51 (36.7) |

| Director General’s Office, Food Directorate | 40 (34.2) | 6 (31.6) | 2 (66.7) | 48 (34.5) |

| Director General’s Office, Office of Nutrition Policy and Promotion | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) |

| Food directorate | 13 (11.1) | 5 (26.3) | 2 (66.7) | 20 (14.4) |

| Office of Nutrition Policy and Promotion | 2 (1.7) | 1 (5.3) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.2) |

| All offices | 117 (100.0) | 19 (100.0) | 3 (100.0) | 139 (100.0) |

The term “meetings” refers to any meetings, correspondence or documents in the Meetings database labelled with the subject “marketing to kids.”

Meetings were categorized as being from “mixed stakeholders” if they were meetings with industry and nonindustry stakeholders together, or the stakeholder was unspecified.

Lobbying interactions from the Registry of Lobbyists

In total, there were 65 individual lobbying registrants, 215 lobbying registrations with subject matters related to children’s marketing or Bill S-228, and 3418 communications between these registrants and government during Bill S-228’s policy window (Table 4). Lobbyists representing industry were responsible for 81.5% (53/65) of registrants, 83.3% (179/215) of registrations and 83.9% (2866/3418) of communications. The mean number of communications per registrant was similar between industry (54.1 [SD 83.3]) and non-industry (46.0 [72.7]) lobbyists.

Table 4:

Lobbying registrants and lobbying registrations related to marketing to children and Bill S-228, and their communications, from the Registry of Lobbyists, summarized by stakeholder type

| Stakeholder type | Lobbying registrants no. (%)* | Lobbying registrations no. (%)† | Communications no. (%)‡ | Communications per registrant, mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industry | 53 (81.5) | 179 (83.3) | 2866 (83.9) | 54.1 ± 83.3 |

| Nonindustry | 12 (18.5) | 36 (16.7) | 552 (16.1) | 46.0 ± 72.7 |

| All stakeholders | 65 (100.0) | 215 (100.0) | 3418 (100.0) | 56.6 ± 81.0 |

Note: SD = standard deviation.

Proportion of all registrants.

Proportion of all registrations.

Proportion of all communications.

Overall, among government institutions that accounted for more than 1% of all communications, industry stakeholders were responsible for 60%–100% of all communications with that institution (Appendix 1, Supplementary Table S1, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/9/1/E280/suppl/DC1). The House of Commons was the government institution most often communicated with overall (1226/3418, 35.9% of all communications) and by both industry (905/2866, 31.6% of industry communications) and nonindustry lobbyists (321/552, 58.2% of nonindustry communications). Following this, the institutions that had the most communications were Agriculture and Agri-Foods Canada (322/2866, 11.2% of industry communications) and Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (316/2866, 11.0%) for industry lobbyists, and the Senate (90/552, 16.3% of nonindustry communications) and Health Canada (60/552, 10.9%) for non-industry lobbyists.

Across all lobbyists, 78.3% (2519/3218) of communications occurred with parliamentarians and their staff, versus 21.7% (699/3218) occurring with civil servants and their staff, with the highest proportion of communications occurring with Members of Parliament, Senators and their staff (42.6%, 1371/3218) (Table 5). Industry lobbyists had 75.3% (2026/2689) of communications with parliamentarians and 24.7% (663/2689) with civil servants, whereas nonindustry lobbyists had 93.2% (493/529) of communications with parliamentarians and 6.8% (36/529) with civil servants. More than 70% of all communications at any rank of government office were from industry lobbyists.

Table 5:

Communications* by lobbying registrants, registered with subject matters related to marketing to kids and Bill S-228 in the Registry of Lobbyists, summarized by stakeholder type, and category and rank of federal government office†

| Federal government office | Industry stakeholders | Nonindustry stakeholders | All stakeholders |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) of lobbying communications,* summarized by stakeholder type | |||

| Parliamentarians and their staff | 2026 (75.3) | 493 (93.2) | 2519 (78.3) |

| Prime Minister’s Office | 143 (5.3) | 13 (2.5) | 156 (4.8) |

| Ministers and parliamentary secretaries | 157 (5.8) | 18 (3.4) | 175 (5.4) |

| Ministerial staff | 753 (28.0) | 64 (12.1) | 817 (25.4) |

| Members of Parliament, senators and their staff | 973 (36.2) | 398 (75.2) | 1371 (42.6) |

| Civil servants and their staff | 663 (24.7) | 36 (6.8) | 699 (21.7) |

| Privy Council Office | 38 (1.4) | 5 (0.9) | 43 (1.3) |

| Deputy ministers | 110 (4.1) | 3 (0.6) | 113 (3.5) |

| Assistant deputy ministers | 233 (8.7) | 12 (2.3) | 245 (7.6) |

| Other government officials | 282 (10.5) | 16 (3.0) | 298 (9.3) |

| All categories | 2689 (100.0) | 529 (100.0) | 3218 (100.0) |

| No. (%) of lobbying communications,* summarized by category and rank of federal government office† | |||

| Parliamentarians and their staff | 2026 (80.4) | 493 (19.6) | 2519 (100.0) |

| Prime Minister’s Office | 143 (91.7) | 13 (8.3) | 156 (100.0) |

| Ministers and parliamentary secretaries | 157 (89.7) | 18 (10.3) | 175 (100.0) |

| Ministerial staff | 753 (92.2) | 64 (7.8) | 817 (100.0) |

| Members of Parliament, senators and their staff | 973 (71.0) | 398 (29.0) | 1371 (100.0) |

| Civil servants and their staff | 663 (94.8) | 36 (5.2) | 699 (100.0) |

| Privy Council Office | 38 (88.4) | 5 (11.6) | 43 (100.0) |

| Deputy ministers | 110 (97.3) | 3 (2.7) | 113 (100.0) |

| Assistant deputy ministers | 233 (95.1) | 12 (4.9) | 245 (100.0) |

| Other government officials | 282 (94.6) | 16 (5.4) | 298 (100.0) |

| All categories | 2689 (83.6) | 529 (16.4) | 3218 (100.0) |

These analyses were completed only for communications occurring in government institutions representing ≥1% of total communications (n = 3218/3418 total communications).

The category and rank of government office for a communication was determined based on the individual’s role or position in government, using their registered position title and branch unit, as stated in the Registry of Lobbyists; categories of federal government office are ranked in order of highest to lowest rank, within “Parliamentarians and their staff” and within “Civil servants”, as described in Table 1.

Interpretation

Most meetings were by industry (> 84%) and most lobbying registrants, lobbying registrations and communications were from industry (> 82%). Overall, industry lobbyists had 5 times more communications than nonindustry lobbyists (2866 v. 552), and at least 10 times more communications with the highest government offices. The results of this study indicate that industry stakeholders were by far the most active communicators and lobbyists on topics related to children’s marketing and Bill S-228 during the period examined.

Research has shown that decision-makers are affected by information overload, meaning that in cases like Bill S-228, in which 1 type of stakeholder is disproportionally interacting with all levels of government, their views may have a stronger influence on the policy outcome.10 Although this study found that nonindustry stakeholders initiated many meetings and interactions related to children’s marketing, their contribution to the overall policy discourse was much less than that of industry. Moreover, compared with an earlier analysis of the Healthy Eating Strategy as a whole, in which 56% of meetings were from industry stakeholders,12 our results showed that for policy discourse related to Canadian children’s marketing restrictions specifically, more than 80% of all interactions with government were from industry. Overall, stakeholder interactions with government related to children’s marketing policy were particularly one-sided.

This study found that industry stakeholders were meeting more broadly across government institutions, and with higher ranking offices than nonindustry stakeholders. More than 90% of communications with the Prime Minister’s Office, with ministers, parliamentary secretaries, deputy ministers and assistant deputy ministers (i.e., the highest ranking offices of government) were with industry lobbyists, and 100% of meetings in the Health Canada deputy minister’s office were with industry. Results suggest that certain government institutions and high-ranking government offices were exposed almost exclusively to industry-influenced messaging related to Bill S-228. Research has indicated that industry stakeholders are often at an advantage in terms of influencing nutrition policy because of many strong, direct relationships with decision-makers, whereas the voices of nutrition and public health professionals often become diluted by the high volume and quantity of readily available nutrition information from industry and other sources, limiting nonindustry stakeholders’ impact on policy change.10,22 Pressure from industry and the limited resources (e.g., funds for lobbying activities) of nonindustry stakeholders have been noted as barriers to nutrition policy change,11 and based on the results of this study, this may have been the case for Bill S-228.

Further qualitative analysis of the nature of the discourse around children’s marketing and Bill S-228 from different stakeholders could provide a clearer understanding of the bill’s eventual outcome. Such an analysis is highly feasible using the Meetings database, given that the contents of all correspondence are publicly available. The Registry of Lobbyists, however, does not disclose the contents of the communications between lobbyists and government and, therefore, does not facilitate qualitative analysis. Given the sheer quantity of communications that occurred from lobbyists registered related to children’s marketing or Bill S-228 (3418 communications, 25 times more than the 139 interactions recorded in the Meetings database), the inclusion of the Registry of Lobbyists under the Transparency and Openness Framework (like the Meetings database), as well as other departments beyond Health Canada, would provide researchers and regulators with deeper insight into all the discourse that occurred around Bill S-228 than is possible using data from only the Health Canada Meetings database. Further elucidation of the potential reasons for Bill S-228’s failure will be crucial to ensuring the successful implementation of future children’s marketing restrictions in Canada.

Limitations

This study provides important quantitative data on stakeholder interactions related to children’s marketing in Canada; however, there are limitations to this analysis, inherent to the nature of the publicly available data. The Meetings database and Registry of Lobbyists exclude interactions between Health Canada and individuals or experts representing themselves (e.g., academic experts), and the Registry of Lobbyists does not include activities from volunteers or from corporations and not-for-profit organizations for which actions of in-house lobbyists form a small portion (< 20%) of duties.20 Therefore, such interactions were not included in this analysis and the outcomes may underrepresent those who infrequently or voluntarily interact with government. Conversely, lobbyists may have registered under broad subject matter terms such as “healthy eating” or “nutrition” and used these meetings to speak about children’s marketing or Bill S-228. Thus, our analyses may underestimate the number of lobbying registrations or communications that took place on these topics. In addition, lobbyists often register with multiple subject matters per registration, and since the specific contents of lobbying communications are unavailable, we are unable to estimate the number of communications that took place specifically related to children’s marketing or Bill S-228 and are limited to analyses of communications that occurred by lobbyists who registered on these subject matters, without knowing the exact details of their communications. Increasing the openness and transparency of the Registry of Lobbyists would reduce this limitation.

Conclusion

The results of this study highlight that industry stakeholders interacted with government more often, more broadly and with higher ranking offices than nonindustry stakeholders on subjects related to children’s marketing and Bill S-228. Although further research is needed to elucidate the nature of discourse around children’s marketing from the various stakeholder communications, continued efforts are also needed to broaden the openness and transparency of stakeholder interactions occurring in more government departments and in the Registry of Lobbyists. Regardless, it is apparent that industry viewpoints were more prominent than those of nonindustry stakeholders during Bill S-228’s policy window.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Christine Mulligan, Aalaa Jawad, Monique Potvin Kent, Lana Vanderlee and Mary L’Abbé contributed to the conception and design of the work. Aalaa Jawad and Mary L’Abbé validated the data. Christine Mulligan and Mary L’Abbé interpreted the data. Christine Mulligan drafted the work and Christine Mulligan, Aalaa Jawad, Monique Potvin Kent, Lana Vanderlee and Mary L’Abbé revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: This research was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Frederick Banting and Charles Best Canada Graduate Scholarships Doctoral Award (Christine Mulligan), the Lawson Centre for Child Nutrition Policy and Nutrition Collaborative Grant (Mary L’Abbé) and by CIHR Project Grants Nos. 142300 and 152979 (Lana Vanderlee, Mary L’Abbé). The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Data sharing: Researchers can access all data through the following links: Registry of Lobbyists (URL: https://lobbycanada.gc.ca/app/secure/ocl/lrs/do/guest?lang=eng) and Health Canada’s Meeting and Correspondence on Healthy Eating database (URL: https://www.canada.ca/en/services/health/campaigns/vision-healthy-canada/healthy-eating/meetings-correspondence.html)

Supplemental information: For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/9/1/E280/suppl/DC1.

References

- 1.Building momentum: lessons on implementing robust restrictions of food and non-alcoholic beverage marketing to children. World Cancer Research Fund International; 2020. [accessed 2020 Jan. 20]. Available: www.wcrf.org/buildingmomentum. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bill S-228: an Act to amend the Food and Drugs Act (prohibiting food and beverage marketing directed at children). 42nd Parliament, 1st session. 2017. Sep 28, [accessed 2020 Jan. 20]. Available: www.parl.ca/DocumentViewer/en/421/bill/S-228/third-reading.

- 3.Healthy Eating Strategy. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2016. [accessed 2020 Feb. 1]. Available: http://healthycanadians.gc.ca/publications/eating-nutrition/healthy-eating-strategy-canada-strategie-saine-alimentation/index-eng.php. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toward restricting unhealthy food and beverage marketing to children: discussion paper for public consultation. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2017. [accessed 2020 Feb. 1]. Available: https://s3.ca-central-1.amazonaws.com/ehq-production-canada/documents/attachments/9bced5c3821050c708407be04b299ac6ad286e47/000/006/633/original/Restricting_Marketing_to_Children.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Consultation report: Restricting marketing of unhealthy food and beverages to children in Canada. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2017. [accessed 2020 Feb. 1]. Available: www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/publications/food-nutrition/restricting-marketing-to-kids-what-we-heard.html. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell NRC, Greene Raine N. The Child Health Protection Act: advocacy must continue. CMAJ. 2019;191:E1040–1. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.190857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guldbrandsson K, Fossum B. An exploration of the theoretical concepts policy windows and policy entrepreneurs at the Swedish public health arena. Health Promot Int. 2009;24:434–44. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dap033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kingdon JW. Agendas, alternatives, and public policies. Boston: Little, Brown; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trudeau J. Minister of Health mandate letter. Ottawa: Office of the Prime Minister of Canada; 2019. [accessed 2020 Feb. 5]. Available: https://pm.gc.ca/en/mandate-letters/minister-health-mandate-letter. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cullerton K, Donnet T, Lee A, et al. Effective advocacy strategies for influencing government nutrition policy: a conceptual model. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2018;15:83. doi: 10.1186/s12966-018-0716-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cullerton K, Donnet T, Lee A, et al. Playing the policy game: a review of the barriers to and enablers of nutrition policy change. Public Health Nutr. 2016;19:2643–53. doi: 10.1017/S1368980016000677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vandenbrink D, Pauzé E, Potvin Kent M. Strategies used by the Canadian food and beverage industry to influence food and nutrition policies. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2020;17:3. doi: 10.1186/s12966-019-0900-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mialon M, Swinburn B, Allender S, et al. Systematic examination of publicly-available information reveals the diverse and extensive corporate political activity of the food industry in Australia. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:283. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-2955-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mialon M, Swinburn B, Wate J, et al. Analysis of the corporate political activity of major food industry actors in Fiji. Global Health. 2016;12:18. doi: 10.1186/s12992-016-0158-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moodie AR. What public health practitioners need to know about unhealthy industry tactics. Am J Public Health. 2017;107:1047–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brownell KD, Warner KE. The perils of ignoring history: Big Tobacco played dirty and millions died. How similar is Big Food? Milbank Q. 2009;87:259–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00555.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Regulatory transparency and openness. Ottawa: Health Canada; [accessed 2020 Jan. 29]. modified 2019 Jan 28. Available: www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/corporate/transparency/regulatory-transparency-and-openness.html. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meetings and correspondence on healthy eating. Ottawa: Health Canada; [accessed 2020 Jan. 29]. modified 2020 Oct. 7. Available: www.canada.ca/en/services/health/campaigns/vision-healthy-canada/healthy-eating/meetings-correspondence.html. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Registry of Lobbyists. Ottawa: Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying of Canada; [accessed 2020 Mar. 14]. modified 2020 Oct. 19. Available: https://lobbycanada.gc.ca/app/secure/ocl/lrs/do/guest?lang=eng. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ten things you should know about lobbying: a guide for federal public office holders. Ottawa: Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying of Canada; [accessed 2020 Nov. 14]. modified 2020 July 13. Available: https://lobbycanada.gc.ca/en/ten-things-you-should-know-about-lobbying-a-guide-for-federal-public-office-holders/ [Google Scholar]

- 21.Open data. Ottawa: Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying of Canada; [accessed 2020 Jan. 14]. modified 2020 May 25. Available: https://lobbycanada.gc.ca/eic/site/012.nsf/eng/h_00872.html. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cullerton K, Donnet T, Lee A, et al. Exploring power and influence in nutrition policy in Australia. Obes Rev. 2016;17:1218–25. doi: 10.1111/obr.12459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.