A nitrate-induced plant-specific transcription factor subfamily impairs nitrate deficiency-triggered ROS accumulation and high-affinity nitrate transport. We isolated a quadruple mutant that displays 2.5-fold more high-affinity nitrate uptake activity.

Keywords: Cell sorting, GARP transcription factors, nitrogen starvation response, plant growth, root nitrate uptake, root protoplasts, ROS, TARGET

Abstract

Plants need to cope with strong variations of nitrogen availability in the soil. Although many molecular players are being discovered concerning how plants perceive NO3− provision, it is less clear how plants recognize a lack of nitrogen. Following nitrogen removal, plants activate their nitrogen starvation response (NSR), which is characterized by the activation of very high-affinity nitrate transport systems (NRT2.4 and NRT2.5) and other sentinel genes involved in N remobilization such as GDH3. Using a combination of functional genomics via transcription factor perturbation and molecular physiology studies, we show that the transcription factors belonging to the HHO subfamily are important regulators of NSR through two potential mechanisms. First, HHOs directly repress the high-affinity nitrate transporters, NRT2.4 and NRT2.5. hho mutants display increased high-affinity nitrate transport activity, opening up promising perspectives for biotechnological applications. Second, we show that reactive oxygen species (ROS) are important to control NSR in wild-type plants and that HRS1 and HHO1 overexpressors and mutants are affected in their ROS content, defining a potential feed-forward branch of the signaling pathway. Taken together, our results define the relationships of two types of molecular players controlling the NSR, namely ROS and the HHO transcription factors. This work (i) up opens perspectives on a poorly understood nutrient-related signaling pathway and (ii) defines targets for molecular breeding of plants with enhanced NO3− uptake.

Introduction

Nitrogen (N) fertilization can considerably improve crop yields. Hence, it is a key requirement for global food production systems, sustaining the world’s population and ensuring food security. As N is the key rate-limiting nutrient in plant growth, understanding the factors that limit N-use efficiency (NUE) will have particular relevance (Han et al., 2015). Inefficient NUE by agricultural systems is also responsible for nitrate run-off into soil water and the atmosphere. Increased leaching of N into drainage water and the release of atmospheric nitrous oxide and reactive N greenhouse gases pollute the troposphere, contribute to global warming, accelerate the eutrophication of rivers, and acidify the soils (Sutton et al., 2011). Thus, understanding the regulation of N transport by plants is likely to contribute to tackling these problems.

As sessile organisms, plants need to adapt to fluctuating nutrient availability (Crawford and Glass, 1998; O’Brien et al., 2016). N-related adaptations include changes in germination rate (Alboresi et al., 2005), root and shoot development (Rahayu et al., 2005; Forde and Walch-Liu, 2009; Krouk et al., 2010a; Gruber et al., 2013; O’Brien et al., 2016), flowering time (Castro Marin et al., 2010), and the transcriptome and metabolome (Scheible et al., 1997; Stitt, 1999; Wang et al., 2004; Krouk et al., 2010a; O’Brien et al., 2016; Alvarez et al., 2020).

Interestingly, one can distinguish between different N-related signaling pathways being activated in response to different N variation scenarios and being reported by different sets of sentinel genes. These signaling pathways include the primary nitrate response (PNR) that can be perceived when NO3−-depleted or N-depleted plants are treated with NO3− (Hu et al., 2009; Medici and Krouk, 2014). PNR sentinel genes are very rapidly regulated by NO3− (within minutes) (Krouk et al., 2010b) and include nitrate reductase gene 1 (NIA1), nitrite reductase gene 1 (NIR1), glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH), and others such as the GARP (Golden2, ARR-B, Psr1) (Safi et al., 2017) transcription factor (TF) genes HRS1 [hypersensitive to low Pi-elicited primary root shortening 1 (Liu et al., 2009)] and HHO1 [HRS1 homolog 1 (Liu et al., 2009; Canales et al., 2014; Medici and Krouk, 2014)]. The PNR is probably the most studied and understood N-related signaling pathway for which several molecular players have been identified. These include the NO3− transceptor CHL1/NRT1.1/NPF6.3 (Ho et al., 2009), a number of kinases and phosphatases (CIPK8, CIPK23, ABI2, and CPK10,30,32) (Ho et al., 2009; Hu et al., 2009; Leran et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2017), and several TFs (NLP6/7, TGA1, NRG2, BT1/BT2, TCP20, and SPL9) (Castaings et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2009; Krouk et al., 2010b; Marchive et al., 2013; Alvarez et al., 2014; Araus et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2016; Guan et al., 2017). Recently an NO3−-triggered Ca2+ signal has been shown to be a crucial relay between the NRT1.1 transceptor and the nuclear events controlling the PNR (Riveras et al., 2015; Krouk, 2017; Liu et al., 2017).

N-related long-distance root–shoot–root signals have also been shown to adapt plant development and metabolism to the whole N status of the plant (Gansel et al., 2001; Ruffel et al., 2011, 2015; Li et al., 2014; Poitout et al., 2017; Gautrat et al., 2020). These long-distance signals can be divided into N demand and N supply signals, which can be genetically uncoupled (Ruffel et al., 2011, 2015; Li et al., 2014). Cytokinin and CEPs (C-terminally encoded peptides) have been shown to be important to generate the N demand root–shoot–root relay necessary to regulate gene expression and modify root development in conditions where N supply is heterogeneous (Ruffel et al., 2011, 2015; Tabata et al., 2014; Ohkubo et al., 2017; Gautrat et al., 2020; Ota et al., 2020)).

Finally, another signaling pathway consists of the nitrogen starvation response (NSR). It can be related to the molecular events triggered by a prolonged N deprivation (Krapp et al., 2011; Kiba and Krapp, 2016; Menz et al., 2016). Sentinel genes of the NSR include high-affinity (Km ~10 µM) NO3− transporters NRT2.4 and NRT2.5 (activated to retrieve traces of NO3− in the soil), as well as the glutamate dehydrogenase 3 gene (GDH3; hypothesized to be activated for N recycling) (Yong et al., 2010; Kiba et al., 2012; Marchi et al., 2013; Lezhneva et al., 2014). To date, the NSR is still less understood than the PNR at a molecular level. The calcineurin B-like7 calcium sensor displayed an effect on NRT2.4 and NRT2.5 expression in the context of the NSR (Ma et al., 2015). A role for miR169 was shown in the control of NFYA TFs in response to NSR, with a substantial impact on NRT2.1 and NRT1.1 transcriptional regulation (Zhao et al., 2011). However, no proof of the actual role of NFYA genes themselves in the NSR was provided in this work (Zhao et al., 2011). LBD37,38,39 TF overexpression has been shown to impact anthocyanin production in N-deprived plants, with a potential regulation of nitrate transporters including NRT2.5 (Rubin et al., 2009). However, no direct regulatory targets of LBDs were provided (Rubin et al., 2009). Finally, recent reports showed that HRS1/HHOs (aka NIGTs) are transcriptional regulators of NRT2.4 and NRT2.5 (Kiba et al., 2018; Maeda et al., 2018).

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are produced during normal cell metabolism and are now largely accepted to be key signaling molecules (Choudhury et al., 2017). Their roles range from physiological to developmental processes such as biotic and abiotic stress response, cell division, cell elongation, and programmed cell death (Foyer and Noctor, 2013; Noctor et al., 2018). In the context of nutritional signaling pathways, ROS are known to be produced upon N, P, and K starvation (Shin and Schachtman, 2004; Shin et al., 2005; Jung et al., 2018). Altering ROS production indeed affects transcriptional responses to K deficiency (Shin and Schachtman, 2004). However, for N, evidence of ROS as potential second messengers is still scant.

Recently CC-type glutaredoxins were shown to be highly N responsive and their overexpression modifies NRT2.1 responsiveness to N (Jung et al., 2018). Also very recently, HNI9, which is potentially involved in N response (Widiez et al., 2011), was shown to display ROS accumulation that correlates with NRT2.1 transcriptional control (Bellegarde et al., 2019). Despite these interesting pieces of indirect evidence, the role of ROS per se in NSR has never been directly demonstrated.

Here, we show that NO3− regulation of one of the most strongly and rapidly induced TFs (HRS1) (Krouk et al., 2010b; Canales et al., 2014) and its close homologs (HHOs) (Safi et al., 2017) are involved in NSR regulation through probably two parallel mechanisms. First, HHOs, being PNR responsive, are repressors of the NSR via direct repression of NRT2.4, NRT2.5, and GDH3 genes. This regulation, when abolished in a quadruple hho mutant, dramatically increases the NO3− high-affinity transport system (HATS), leading to striking phenotypes with potential biotechnological applications. This provides new insight into the molecular connection between PNR and NSR signaling. Second, ROS-scavenging treatments concomitant with N deprivation treatments totally abolish the NSR, showing that ROS accumulation is a prerequisite for the NSR. Third, HHO genetic manipulations (overexpression and knockout mutations) impair ROS accumulation and/or metabolism of the plants. These observations led us to build a working model in which the HHOs control two parallel branches of the NSR response in Arabidopsis including one that involves ROS.

Materials and methods

Plant material

All Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) plants were in the Columbia-0 background. hrs1-1 (SALK_067074), hho1-1 (SAIL_28_D03) (Medici et al., 2015), hho2-1 (SALK_070096), and hho3-1 (SALK_146833) mutants were obtained from the ABRC seed stock center, and homozygous lines were screened by PCR. The double (hrs1;hho1), triple (hrs1;hho1;hho2), and quadruple (hrs1;hho1;hho2;hho3) mutants have been obtained by crossing. The promoter:gene:GFP (green fluorescent protein) lines were obtained by cloning the 3 kb upstream promoter region followed by the HRS1 gene (genomic sequence) into the pMDC107 Gateway-compatible vector (Curtis and Grossniklaus, 2003).

The overexpressor lines were obtained by cloning HRS1- and HHO1-coding sequences into the pMDC32 Gateway-compatible vector (Medici et al., 2015). The constructs were transferred to the Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101strain and used in plant transformation by floral dip (Zhang et al., 2006).

Growth conditions and treatments

Plants were grown in sterile hydroponic conditions for 14 d in day/night cycles (16/8 h; 90 µmol photons m−2 s−1) at 22 °C as described by Krouk et al. (2010b). The hydroponic medium consisted of 1 mM KH2PO4, 1.5 mM MgSO4, 0.25 mM K2SO4, 3 mM CaCl2, 0.1 mM Na-Fe-EDTA, 30 µM H3BO3, 5 µM MnSO4, 1 µM ZnSO4, 1 µM CuSO4, 0.1 µM (NH4)6Mo7O24, 5 µM KI; supplied with 3 mM sucrose, 0.5 mM NH4NO3 (1 mM KNO3 for results in Fig. 1), and 0.5 g l−1 MES. pH was adjusted to 5.7 by adding 1 M KOH. For +N→–N experiments, plants were transferred to an equivalent fresh N-free or 0.5 mM NH4NO3-containing medium (1 mM KNO3 for results in Fig. 1). For –N→+N experiments, all plants were N starved for 3 d, and then transferred to an equivalent fresh medium containing 0.5 mM NH4NO3. ROS-scavenging drugs were applied upon plant transfer to the new medium. Roots (corresponding to ~60 plants coming from a single phytatray) were harvested at different time points and immediately frozen in liquid N. Each time point and genotype was harvested from a different phytatray. Experiments were performed at least twice, and representative data are reported in the figures.

Fig. 1.

HRS1 and HHO1 are repressors of NSR sentinel genes. (A) Root response of NRT2.4, NRT2.5, and GDH3 to the NSR in Columbia, hrs1;hho1, and 35S:HRS1 genotypes. Plants were grown in sterile hydroponic conditions on N-containing medium for 14 d. At time 0, the medium was shifted to –N conditions for 0, 2, 4, or 6 d, or +N as a control. (B) Root response of NRT2.4, NRT2.5, and GDH3 to NSR in Columbia WT, 35S:HRS1, and 35S:HHO1 genotypes. Plants were grown in sterile hydroponic conditions on N-containing medium for 14 d. Then the medium was shifted to –N conditions for 0, 1, 2, 4, and 6 d (the media background was kept unchanged). All transcript levels were quantified by qPCR and normalized to two housekeeping genes (ACT and CLA); values are means ±SE (n=4). Asterisks indicate significant differences from WT plants (*P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; Student’s t-test).

For non-sterile hydroponic culture, seeds were sown on Eppendorf tube caps with a 1 mm hole filled by H2O–agar 0.5% solution and grown for 7 d on H2O. Then, plants were transferred to the same medium as above (without sucrose), supplied with 0.5 mM NH4NO3, and grown in a short-day light period (8 h light 23 °C and 16 h dark 21 °C) at 260 µmol photons m−2 s−1 and 70% humidity. The nutritive solution was renewed every 4 d for 5 weeks. Then plants were transferred to an equivalent fresh N-free or 0.5 mM NH4NO3-containing medium (1–3 weeks for 15NO3− uptake experiments and 6 h for ROS measurements).

For mutant complementation experiments (Fig. 2D), wild-type (WT) and complemented (hrs1;hho1;hho2;hho3;pHRS1:HRS1:GFP) sterilized seeds were sown on the surface of sterile solid N-free Murashige and Skoog (MS)/2 basal salt medium [1% (w/v) agar], supplemented with 3 mM sucrose, 0.5 mM NH4NO3, and MES buffered at pH 5.7 (0.5 g l−1). Agar plates were incubated vertically in an in vitro growth chamber for 12 d in day/night cycles (16/8 h; 90 µmol photons m−2 s−1) at 22 °C.

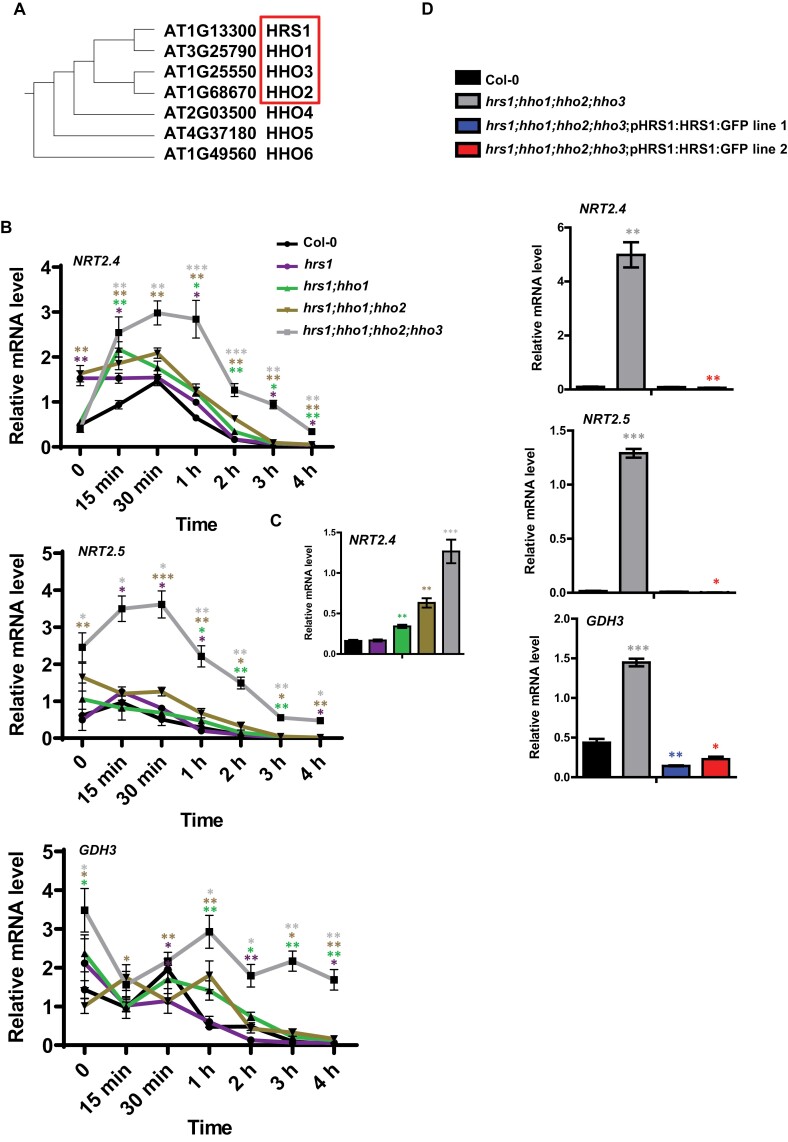

Fig. 2.

The HHO subfamily is involved in repressing NSR sentinels after NO3− provision.

(A) Phylogenetic tree representing the GARP HHO subfamily. The tree was built as previously described (Safi et al., 2017). (B) Root response of NRT2.4, NRT2.5, and GDH3 to the PNR following N starvation in Columbia WT, hrs1, hrs1;hho1, hrs1;hho1;hho2, and hrs1;hho1;hho2;hho3 genotypes. Plants were grown in sterile hydroponic conditions on full medium for 14 d, subjected to N starvation for 3 d, and then resupplied with 0.5 mM NH4NO3 for 0 (harvested before treatment), 15 min, 30 min, 1 h, 2 h, 3 h, and 4 h (the media background was kept unchanged). (C) NRT2.4 expression 2 h after N supply, showing an additive de-repression effect following sequential deletion of HHO genes. (D) pHRS1:HRS1:GFP is sufficient to complement the quadruple mutant. WT, hrs1;hho1;hho2;hho3, and hrs1;hho1;hho2;hho3;pHRS1:HRS1:GFP line 1 and line 2 (two independent transformation events) were grown on Petri dishes on 0.5 mM NH4NO3 for 12 d. Roots were harvested and transcripts were measured by qPCR. All transcript levels were quantified by qPCR and normalized to two housekeeping genes (ACT and CLA); values are means ±SE (n=4). Asterisks indicate significant differences from WT plants (*P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; Student’s t-test).

Real-time quantitative PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from Arabidopsis roots using Trizol® (Thermo Scientific) and digested with DNase I (Sigma-Aldrich). RNA was then reverse transcribed to single-stranded cDNA using Thermo script reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Gene expression was determined by quantitative PCR (LightCycler 480; Roche Diagnostics) using gene-specific primers (provided upon request) and TAKARA mix (Roche). Expression levels of tested genes were normalized to expression levels of the Actin and Clathrin genes as previously described (Krouk et al., 2010b).

Expression and purification of GST–HRS1 protein

The protocol is fully described in Medici et al. (2015). Briefly, the HRS1 coding sequence was first inserted into the pDONR207 vector, and then transferred to the pDEST15 vector (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Glutathione S-transferase (GST)–HRS1 fusion protein was expressed in Escherichia coli Rosetta 2(DE3)pLysS (Novagen). Transformed bacteria were grown in Terrific broth medium at 37 °C containing the appropriate antibiotics until the OD660 reached 0.7–0.8. After induction with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 16 h at 22 °C, cells were harvested by centrifugation (6000 g, 10 min, 4 °C) and suspended in 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing lysozyme from chicken egg white (Sigma) and complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). The resulting cell suspension was sonicated and centrifuged at 15 000 g for 15 min at 4 °C to remove intact cells and debris. The protein extract was mixed with buffered glutathione–Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare), and incubated at 4 °C for 3 h. The resin was centrifuged (500 g, 10 min, 4 °C) and washed five times with 1× PBS.

GST–HRS1 was then eluted with 10 mM reduced glutathione (Sigma) in 50 mM Tris buffer and dialyzed overnight in 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 buffer.

All fractions were subjected to SDS–PAGE. For protein quantification, absorbance was measured on a VICTOR2™ microplate reader (Perkin Elmer) at 660 nm using the Pierce 660 nm Protein Assay (Pierce/Thermo Scientific).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

EMSA was performed using purified GST–HRS1 protein and 3′ end Biotin_TEG-labeled DNA probes. ssDNA oligonucleotides were incubated at 95 °C for 10 min and then annealed to generate dsDNA probes by slow cooling. The sequences of the oligonucleotide probes were synthesized by Eurofins Genomics and are provided in Supplementary Fig. S6. The binding of the purified proteins (~150 ng) to the Biotin_TEG-labeled probes (20 fmol) was carried out using the LightShift Chemiluminescent EMSA Kit (Thermo Scientific) in a 20 μl reaction mixture containing 1× binding buffer (10 mM Tris, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, pH 7.5), 2.5% glycerol, 5 mM MgCl2, 2 µg of poly(dI–dC), and 0.05% NP-40. After 30 min of incubation at 24 °C, the protein–probe mixture was separated in a 4% polyacrylamide native gel at 100 V for 50 min then transferred overnight to a Biodyne B Nylon membrane (Thermo Scientific) by capillarity in 20× SSC buffer. After UV cross-linking (254 nm) for 90 s at 120 mJ cm−2, the migration of the Biotin_TEG-labeled probes was detected using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin in the LightShift Chemiluminescent EMSA Kit (Thermo Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and then exposed to X-ray film.

ROS measurement

An Amplex® Red Hydrogen Peroxide/Peroxidase Assay Kit (Molecular Probes) was used to measure hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) production in 6-week-old plants, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Six independent roots for each treatment and genotype were frozen and ground in liquid N. All the protocol steps were carried out in a cold room at 4 °C. A 200 µl aliquot of phosphate buffer (50 mM K2HPO4, pH 7.4) was added to 50 mg of ground frozen tissue. After two centrifugations at 14 000 g for 10 min, 50 µl of the supernatant were added to 50 µl of the Amplex® Red mixture (100 µM 10-acetyl-3,7-dihydroxyphenoxazine and 0.2 U ml–1 horseradish peroxidase) and incubated in the dark at room temperature for 30 min. The absorbance was measured using the VICTOR2™ microplate reader (Perkin Elmer) at 560 nm in 96-well transparent plates. A blank (containing 50 μl of phosphate buffer and 50 μl of Amplex® Red reagent) was used as a negative control. The H2O2 concentration was reported to the exact powder mass of each sample. The absorbance was measured twice for each point.

Nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT; Sigma-Aldrich) was used for superoxide (O2· −) staining. Plants were vertically grown on 0.5 mM NH4NO3-containing medium for 2 weeks. Whole freshly harvested plants were stained for 15 min in 20 mM phosphate buffer pH 6.1 containing 2 mM NBT. The seedlings were subsequently washed using the same buffer.

Antioxidant enzyme [ascorbate peroxidase (APX), glutathione reductase (GR), and glutatthione peroxidase ((GPX)] activity measurements were performed as previously described (Leclercq et al., 2012).

15NO3− uptake

Root 15NO3− influx was assayed as previously described (Lejay et al., 1999). Plants were sequentially transferred to 0.1 mM CaSO4 for 1 min and then to basal nutrient medium (pH 5.7) containing appropriate concentrations of K15NO3. In the labeling solution, K15NO3 was used at 10–250 µM for the HATS and at 1–5 mM for the low-affinity transport system (LATS). After 5 min, roots were washed for 1 min in 0.1 mM CaSO4, harvested, dried at 70 °C for 48 h, and analyzed. The total N content and atomic percentage 15N abundance of the samples were determined by continuous-flow MS as previously described (Clarkson et al., 1996), using a Euro-EA Eurovector elemental analyzer coupled with an IsoPrime mass spectrometer (GV Instruments). Each uptake value is the mean ±SE of six replicates (six independent roots from different plants).

Phylogenetic analysis

The phylogeny reconstruction was established as described in Safi et al. (2017) on the whole protein sequences. Briefly, the tree was built using the mafft algorithm (http://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server/, parameters: G-INS-1, BLOSUM62) and drawn with FigTree. Different parameters including FFT-NS-2, FFT-NS-i, and E-INS-i were used and they yielded very similar trees.

TF perturbation assays in the TARGET system

The TARGET (transient assay reporting genome-wide effect of transcription factors) procedure was performed as previously described (Bargmann et al., 2013; Medici et al., 2015). Root protoplasts were treated with 35 μM CHX (cycloheximide) for 30 min, then 10 μM DEX (dexamethasone) was added and the cell suspension was incubated in the dark overnight at room temperature. Controls were respectively treated with DMSO and ethanol.

The red fluorescent protein was used as a selection marker for fluorescent-activated cell sorting of successfully transformed protoplasts. N-free buffers were maintained during the whole procedure (as compared with Medici et al., 2015, where NO3− was maintained during the TARGET procedure). RNA was extracted and amplified for hybridization with ATH1 Affymetrix chips.

Transcriptomic analysis was performed using ANOVA followed by a Tukey test using R (https://www.r-project.org/) custom-made scripts following previously published procedures (Obertello et al., 2010; Ristova et al., 2016). Clustering was performed using the MeV software (http://mev.tm4.org/). Briefly, the ANOVA was carried out using the R ‘aov()’ function on log2 MAS5-normalized data. A probe signal has been modeled as follows: Yi=α 1.DEX+α 2.NO3+α 3.NO3×DEX+ε; where α1–α3 represent the coefficient quantifying the effect of each factor (DEX, NO3−) and their interaction (DEX×NO3−), and ε represents the unexplained variance. We determined the false discovery rate (FDR) to be <10% for an ANOVA P-value cut-off of 0.01 and a Tukey P-value cut-off of 0.01.

Statistical analysis

The mean ±SE is shown for all numerical values. Statistical significance was computed using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. Significance cut-off was *P<0.05, **P<0.01, and ***P<0.001.

Fully detailed protocols for ANOVA and Tukey tests for TARGET and ROS signature clustering are provided upon request.

Results

During our previous investigations, we studied the role of HRS1 in the control of primary root growth in response to a combination of N and P provision (Medici et al., 2015). This research led to the identification of a set of HRS1 direct targets. In that study, we noted that NRT2.4 transcript accumulation was repressed upon controlled nuclear entrance of the GR:HRS1 fusion protein (Supplementary Fig. S1A (Bargmann et al., 2013; Medici et al., 2015). We also observed that NRT2.4 was overexpressed in the double hrs1;hho1 mutant (Supplementary Fig. S1B). These preliminary results suggested that HRS1 could be a direct regulator (e.g. repressor) of the NRT2.4 gene. Moreover, as NRT2.4 was shown to be a very good marker of the NSR (Kiba et al., 2012), and no regulator was shown to participate in this signaling pathway at the outset of our study, we decided to investigate the role of HRS1 and its close HHO homologs in the NSR. Since the experiments on the HRS1/HHO family in Medici et al. (2015) (Supplementary Fig. S1B) were performed on plants grown in very particular conditions (low phosphate, high N), in this current study we investigated the behavior of the hrs1;hho1 mutants and HRS1 and HHO1 overexpressors (Supplementary Fig. S1A) in the specific context of the NSR (transfer of plants from N-containing media to N-free media). To consolidate our investigations, we also studied two other genes considered as NSR sentinels, namely NRT2.5 (Lezhneva et al., 2014) and GDH3 (Marchi et al., 2013).

HHO transcription factors repress NSR sentinel genes

Consistent with previous findings (Kiba et al., 2012), when transfered to N-depleted medium, WT plants show strong activation of NRT2.4, NRT2.5, and GDH3 genes within the first days of starvation (Fig. 1A). However, this response, defined as the NSR, is diminished in 35S:HRS1 plants. NSR marker genes are also affected in the hrs1;hho1 double mutant as they peak earlier and are also repressed at earlier time points compared with the WT (Fig. 1A). Given that HRS1 and HHO1 are homologous genes, and because the double mutant has an NSR phenotype, we set up an experiment to compare HRS1 and HHO1 overexpressors side by side. This experiment (Fig. 1B) showed that indeed 35S:HRS1 and 35S:HHO1 display similar molecular phenotypes with a reduction of the NSR. Taken together, these results suggest that HRS1 and HHO1 are repressors of the NSR, probably through the direct regulation of NRT2.4 and NRT2.5 loci.

One interesting aspect of the hrs1;hho1 double mutant was a very variable response across experiments to the NSR, with the most representative response shown in Fig. 1A. This can be explained by the previous findings that showed that HRS1, HHO1, and its paralogs HHO2 and HHO3 are all transcriptionally regulated by the PNR (Wang et al., 2004; Krouk et al., 2010b). To understand the interactions of the HHO paralogs in regulating the NSR, we generated plants with an increasing number of deletions in this gene subfamily (Fig. 2A). We created the triple hrs1;hho1;hho2 and quadruple hrs1;hho1;hho2;hho3 mutants by crossing (characterization in Supplementary Fig. S2B) and compared them with the WT, and single and double mutants. The rationale was that if these HRS1/HHO TFs are indeed repressors of the NSR, they could be strongly regulated by nitrate (in the context of the PNR) in order to rapidly stop the NSR when NO3− is available. We thus tested this hypothesis by subjecting the plants (WT, single, double, triple, and quadruple hrs1/hho mutants) to an N starvation treatment first, then treated them with NO3−, and subsequently followed the speed of NSR sentinel gene repression (Fig. 2B). In this context, we showed that in the WT, consistent with what was observed by Okamoto et al. (2003), NSR sentinels peak within minutes and are strongly repressed within 2–4 h following NO3− provision (Fig. 2B). As predicted, the sequential deletion of the HHO paralogs triggers a de-repression of NSR genes. It is noteworthy that the de-repression of the NSR sentinel genes follows the sequential deletion of HHO genes (quite manifest at the 2 h and 3 h time points) (Fig. 2C). The HRS1/HHO quadruple mutant displays the strongest phenotype and seems to be unable to completely repress the locus even after several hours of NO3− provision (Fig. 2B, C).

To validate that it is indeed a combination of HRS1/HHO deletion that de-repressed the NSR sentinels (as opposed, for example, to the simple effect of hho3 mutation), we performed a complementation experiment of the quadruple hrs1;hho1;hho2;hho3 mutant with pHRS1:HRS1:GFP. We showed (Fig. 2D) that two independent lines are able to fully restore the WT phenotype regarding the NSR sentinel gene expression. This demonstrates that it is indeed a combination of HRS1/HHO deletions that is needed to observe the de-repression of NSR genes (Fig. 2B–D).

These results show that HHOs have a redundant function and that they collectively are involved in repressing NSR sentinels when NO3− is provided (Fig. 2).

HHO transcription factors control NO3− uptake via HATS

Among the three NSR sentinel genes, NRT2.4 and NRT2.5 were shown to be involved in a very high-affinity nitrate transport system (Kiba et al., 2012; Lezhneva et al., 2014). Since we observed interesting molecular phenotypes in the context of N starvation for the 35S:HRS1 and hrs1;hho1 mutants (Fig. 1), we tested their HATS activity following prolonged NO3− starvation (Fig. 3A). We performed 15NO3− labeling experiments, and indeed found that 35S:HRS1 plants are affected in NO3− HATS (10 µM) activity. We subsequently sought to determine the range of affinities at which HRS1 overexpression may have an effect. We observed (Fig. 3B) that the whole high-affinity range was decreased in the 35S:HRS1 plants (with a 2-fold decrease for the very high nitrate affinity conditions, concomitant with a decrease in NRT2.4, NRT2.5, and NRT2.1 mRNA accumulation), while low-affinity nitrate transport activity remained unchanged in the 35S:HRS1 background (Fig. 3B). The double mutant hrs1;hho1 displayed a weak phenotype in this context, as compared with the WT.

Fig. 3.

HRS1 and HHO1 negatively control NO3− HATS. (A) NO3− uptake is altered in 35S:HRS1 and in the double mutant hrs1;hho1. Plants were grown for 5 weeks on N-containing medium. The medium was then shifted to –N conditions or +N as a control for 1 or 3 weeks. Values are means ±SE (n=6). (B) Plants starved for 1 week were used to quantify NO3− HATS and LATS activities as well as high-affinity NO3− transporter transcript levels. qPCR data were normalized to two housekeeping genes (ACT and CLA); values are means ±SE (n=12). NO3− uptake measurements were performed on different 15NO3− concentrations (10, 100, 250 µM, 1 mM, and 5 mM) to evaluate HATS and LATS. Values are means ±SE (n=6). The experiment was performed exactly as detailed for (A). Asterisks indicate significant differences from WT plants (*P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; Student’s t-test).

Since we showed that the hrs1/hho mutants were unable to totally repress the NRT2.4 and NRT2.5 loci (Fig. 2B), we also wanted to study functional phenotypes in these mutants. Thus, we performed 15NO3− labeling experiments on N-containing media (Fig. 4A). Consistent with our previous findings (Fig. 2B), the sequential deletion of HHO genes (Fig. 2A) increases NO3− HATS activity, with a maximum effect recorded in the hrs1;hho1;hho2;hho3 quadruple mutant that displays a 2.5-fold increase of HATS activity (Fig. 4A). Very interestingly, the nitrate transport activity increase is accompanied by a strong stimulation of the quadruple mutant growth in these conditions (Fig. 4B). Although its phenotype is less pronounced than in the quadruple mutant, the double mutant hrs1;hho1 still displays larger shoots as compared with the WT (Supplementary Fig. S3). The mutant phenotypes were lost in plants grown in –N conditions. This can be easily explained. Indeed, even if NRT2.4 and NRT2.5 are de-repressed in the mutants in both conditions, only the mutants grown on +N can take up more nitrate than the WT. Furthermore, expression of HHOs is known to be very low in –N conditions (Krouk et al., 2010b; Menz et al., 2016), so mutations of genes which are weakly expressed in –N are expected to have low or no effect. These are two possible explanations of why we see mutant phenotypes only on +N conditions. Finally, the quadruple mutant displays strong phenotypes following N provision even for genes not previously known to be involved in the NSR such as NRT1.1, NRT2.2, or NAR2.1 (Supplementary Fig. S4). Also, a very recent study reported that heterologous expression of DsNAR2.1 (Dianthus spiculifolius) increased NO3− influx in N-starved Arabidopsis plants (Ma et al., 2020). Thus, our data demonstrate that many players of the NO3− transport machinery are highly expressed in the quadruple hrs1;hho1;hho2;hho3 mutant.

Fig. 4.

The HHO subfamily represses NO3− uptake and growth in +N conditions. (A) NO3− uptake is altered in hrs1, hrs1;hho1, hrs1;hho1;hho2, and hrs1;hho1;hho2;hho3 mutants. Plants were grown for 6 weeks on N-containing non-sterile hydroponics (0.5 mM NH4NO3). NO3− uptake measurements were performed at 100 µM 15NO3− to evaluate the HATS. Values are means ±SE (n=6). Asterisks indicate significant differences from WT plants (*P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; Student’s t-test). (B) Representative pictures of the WT and the hrs1;hho1;hho2;hho3 quadruple mutant, grown in +N conditions, on the day of the uptake experiment show a growth phenotype.

In conclusion, the modification of HHO TF expression has functional consequences on NO3− HATS activities, consistent with their role in the transcriptional control on HATS nitrate transporters NRT2.4 and NRT2.5.

Identification of HRS1 direct targets points to a role for reactive oxygen species

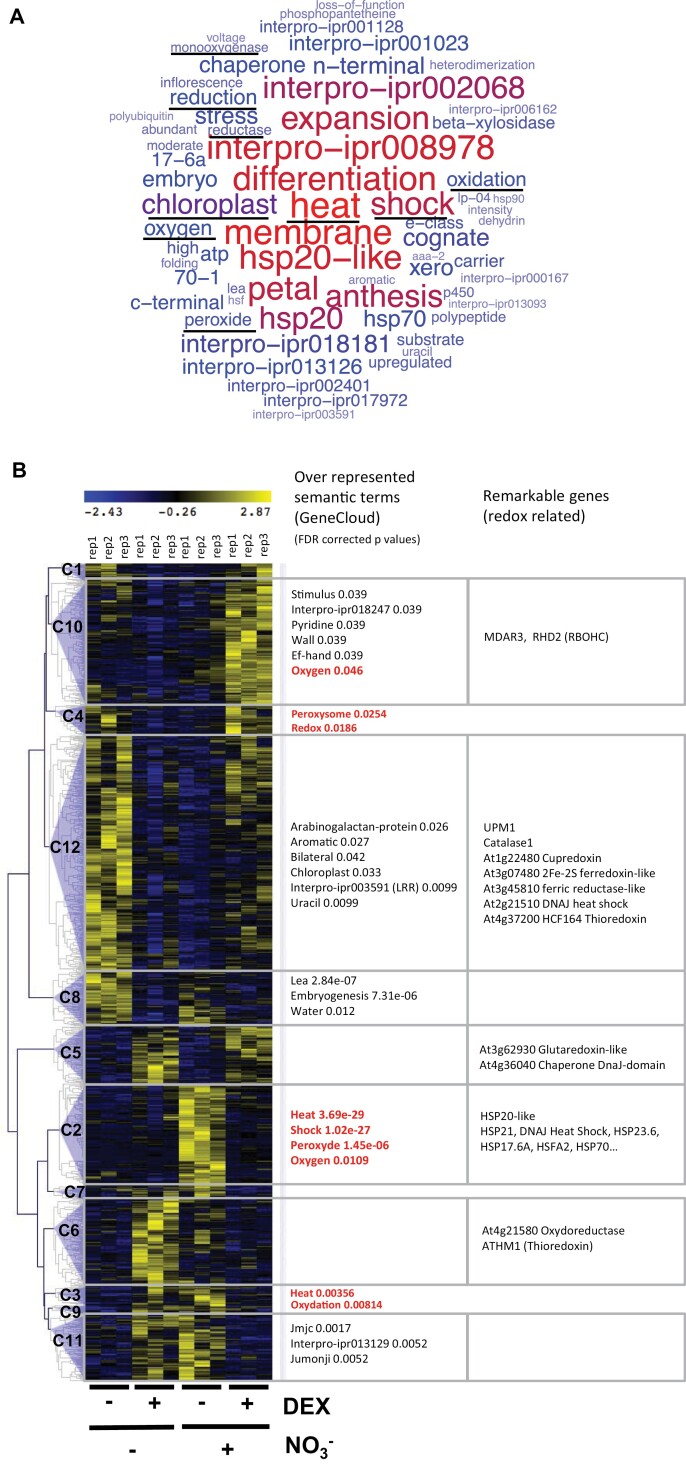

To broaden our investigations around this phenomenon, we studied HRS1 direct genome-wide targets in an N-varying context. To this end, we performed HRS1 perturbation using the TARGET approach (Bargmann et al., 2013; Para et al., 2014; Medici et al., 2015), including three biological repeats, by using root protoplasts not treated with NO3− during the TARGET procedure. We compared these new results with our previously reported HRS1 TARGET data, performed on NO3−-containing medium (Medici et al., 2015). Both studies were performed in parallel in the exact same conditions and in the same lab. CHX was maintained in the media during the procedure to retrieve only potential direct targets of HRS1. This provided several important insights concerning HRS1 TF activity. First, we retrieved 1050 potential HRS1 direct targets (non-redundant AGI) (see the Materials and methods for statistics, and Supplementary Dataset S1 for the gene list). The obtained HRS1 direct targets were subjected to GeneCloud (Krouk et al., 2015) analysis that performs semantic term enrichment investigation on gene lists (Fig. 5A). This revealed that HRS1 controls a highly coherent group of genes, function-wise. Very strikingly, terms related to redox function (oxidation, peroxide, reductase, and oxygen) were highly over-represented in this list of genes controlled by HRS1 (Fig. 5A; Supplementary Dataset S1).

Fig. 5.

HRS1 direct genome-wide targets are largely NO3− dependent and contain many redox-related genes. The TARGET procedure was performed with NO3− (data from Medici et al., 2015) and without NO3− (this work). An ANOVA followed by a Tukey test retrieved 1050 HRS1-regulated genes (ANOVA P-value cut-off 0.01, Tukey P-value cut-off 0.01, FDR <10%). (A) GeneCloud analysis (Krouk et al., 2015) of the 1050 direct targets of HRS1. (B) Clustering analysis (Pearson correlation) was performed using MeV software (number of clusters was determined by the FOM method). A selection of over-represented semantic terms is displayed in front of each cluster. Notable redox-related genes are displayed in the right column. The list of each cluster, their related gene list, as well as their respective semantic analysis are provided in Supplementary Dataset S1.

A clustering analysis revealed 12 different modes of gene regulation by HRS1 in combination with NO3− (Fig. 5B; Supplementary Dataset S1). Interestingly, the expression of the vast majority (86%) of HRS1 direct genome-wide targets is dependent on the NO3− context (Fig. 5B). This can be explained by N-related transcriptional, post-transcriptional, and post-translational modifications that could affect HRS1 itself or its partners.

Among the 12 clusters of HRS1 target genes, the two NO3−-insensitive clusters are clusters #5 and #8. Cluster #8 contains genes whose functions were reminiscent of the germination control of HRS1 demonstrated in previous work (Wu et al., 2012) (Fig. 5B). Cluster #5 contains genes with diverse functions including a chaperone Dnaj-domain protein and a glutaredoxin. It is noteworthy that most of the HRS1-regulated gene clusters contain genes related to the cell redox state (Fig. 5B). However, the most enriched clusters in redox-related genes are clusters #12 and #2. Cluster #2 contains many genes annotated as heat shock proteins and heat shock factors. For this cluster, HRS1 plays a role of repressor only when NO3− is provided to the protoplasts. On the other hand, cluster #12 contains genes that are repressed by HRS1 only when NO3− is not present during the TARGET procedure (Fig. 5B). This cluster contains many redox-related genes such as catalase1, a ferredoxin, a thioredoxin, and a cupredoxin.

In conclusion, this HRS1 TF perturbation analysis in the plant cell-based TARGET system prompted us to investigate below (i) the role of ROS in the NSR and (ii) the role of ROS in the HRS1-dependent control of the NSR. It also illustrates that a TF can greatly modify its targets according to a nutritional context (Fig. 5).

ROS scavenging molecules are repressors of the NSR

To investigate the role of ROS in the NSR, we undertook a pharmacological approach. In a first experiment, we used a co-treatment with potassium iodide (KI, 5 mM) (Tsukagoshi et al., 2010; Yamada et al., 2020) and mannitol (5 mM) (Shen et al., 1997a, b; Voegele et al., 2005; Cuin and Shabala, 2007), shown to scavenge H2O2 and hydroxyl radicals (·OH), respectively. This KI–mannitol co-treatment completely abolished the induction of the NSR sentinel genes (Fig. 6A). Then, we investigated the individual as well as the combined effect of KI and mannitol, in parallel with diphenyleniodonium (DPI; an NADPH oxidase inhibitor) (Orozco-Cardenas et al., 2001; Tsukagoshi et al., 2010). This experiment confirmed that the inhibition of ROS production has a severe effect on the NSR (Fig. 6B). More precisely, for NRT2.4 and NRT2.5, we recorded that KI and DPI strongly repressed the gene response to N deprivation. For NRT2.5 and GDH3, mannitol alone seems to also have an effect as it dampens down the transcriptional responses to N depletion. We also found that DMSO may have a potential effect on its own (for NRT2.5 and GDH3) which indeed correlates with the fact that it showed quenching activity on ·OH (Franco et al., 2007). However, when DPI treatment was compared with its DMSO mock control, it was itself significantly affecting the NSR for the three sentinel genes (Fig. 6B). These experiments demonstrate that ROS-scavenging molecules are affecting the plant NSR, and that ROS are an essential activating potential second messenger of the NSR.

Fig. 6.

ROS are necessary for the NSR. (A) Altered response of NRT2.4, NRT2.5, and GDH3 by KI–mannitol treatment. Plants were grown in sterile hydroponic conditions on N-containing medium for 14 d. Thereafter, the medium was shifted to –N conditions containing or not 5 mM KI and 5 mM mannitol for 0, 2, 4, and 6 d, or +N as a control. (B) Altered response of NRT2.4, NRT2.5, and GDH3 by ROS scavenger treatment. Plants were grown in sterile hydroponic conditions on N-containing medium for 14 d. Then they were transferred to –N or +N conditions for 0, 2, and 4 d. In parallel, some of the N-starved plants were treated with 5 mM KI, 5 mM mannitol, a combination of both, or with 10 µM DPI. DMSO was used as a mock treatment of DPI. All transcript levels were quantified by qPCR and normalized to two housekeeping genes (ACT and CLA); values are means ±SE (n=4). Asterisks indicate significant differences from WT plants (*P<0.045; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; Student’s t-test).

To further characterize the role of ROS in the control of the NSR, we studied the effect of rboh mutants on the NSR. Indeed, we noticed that a major ROS-producing gene (RBOHC/RHD2) in plants was a potential direct target of HRS1 since it belongs to cluster #10 (Fig. 5B). We monitored NSR in rbohc single and rbohd;rbohf double mutants (Supplementary Fig. S5). As expected, rbohc mutation (characterized in Supplementary Fig. S2C) significantly affected the NSR of NRT2.4 and NRT2.5 (Supplementary Fig. S5). The GDH3 NSR is affected in the rbohd;rbohf double mutant. Interestingly H2O2 provision reverts the mutant phenotype, which strongly suggests that H2O2 is necessary to maintain the NSR (Supplementary Fig. S5).

HHO TFs repress the NSR through direct and indirect mechanisms

Given that (i) HRS1 regulates ROS-related genes (Fig. 5); (ii) ROS production seems to be important for the NSR (Fig. 6); and (iii) HRS1 and HHOs are themselves important regulators of the NSR (Figs 1, 2), we wanted to investigate if the NSR control by HRS1 could have some branch which is ROS dependent or if it was a direct regulation. To do this, we set up two types of experiments:

First, we demonstrated that the regulation of NRT2.4 and NRT2.5 loci happens through the potential binding of HRS1 to the promoter of these genes (Supplementary Fig. S6). To this end, we identified a new potential HRS1 DNA-binding element by running the MEME algorithm (Bailey et al., 2009) on the 500 bp upstream sequences of the most repressed HRS1 genes in the TARGET analysis (list of repressed direct targets in Medici et al., 2015). This new uncovered HRS1 cis-element contains the GANNNTCTNGA consensus that resembles the consensus motif of HHO2 and HHO3 revealed by DAP-seq in the work by O’Malley et al. (2016) (Supplementary Fig. S6A). We used EMSA and competition assays with cold probes to demonstrate that HRS1 had a specific affinity for this new motif, and that the conserved cytosine in the sequence is not critical for the DNA–protein recognition, while the distal guanines play a significant role (Supplementary Fig. S6B–D). Interestingly, this HRS1 motif is found twice in each of the promoters of the three sentinel genes as well as in NRT2.1 (Supplementary Fig. S6E). We thus tested the binding of HRS1 to probes made from the promoter sequences framing the HRS1-binding sites, and validated that HRS1 is able to bind NSR sentinel genes in a promoter context (Supplementary Fig. S6E–G). Our results are strengthened by DAP-seq data (O’Malley et al., 2016) showing that HHO subfamily binding (Safi et al., 2017) is especially present in the promoter of the NRT2.4, NRT2.5, and GDH3 genes (Supplementary Fig. S7). Interestingly, no specific binding is recorded for KANADI2 or bZIP16 being, respectively, a G2-like TF as well, but not in the same subfamily (Safi et al., 2017), or a bZIP (different TF family).

Taken together, DAP-seq (Supplementary Fig. S7), EMSA (Supplementary Fig. S6), and TARGET data (Supplementary Fig. S1A), as well as the overexpression approach (Fig. 1; Supplementary Fig. S1B) and mutant phenotypes (Figs 1–4; Supplementary Fig. S1B), strongly suggest that HRS1 and its homolog genes directly repress the NSR sentinel genes. Very recent results (Kiba et al., 2018) (Maeda et al., 2018) demonstrated that this HRS1–DNA binding occurs using the yeast one-hybrid system and promoter–β-glucuronidase (GUS) transactivation in plants. This provides a very good external validation of our results, and vice versa.

Second, we wanted to test if the HHO-related phenotypes could also be explained by a default in ROS production and/or accumulation. To this aim, by using Amplex® Red measurements (Shin and Schachtman, 2004; Shin et al., 2005; Chakraborty et al., 2016), we demonstrated that early N depletion (within 6 h) triggers ROS accumulation in root tissues of WT plants, consistent with previous observations (Shin et al., 2005). We also found that this accumulation is lost in the 35S:HRS1 plants and reduced in the 35S:HHO1 genotype, validating a role for these TFs in the control of ROS accumulation in plants following N provision (Fig. 7A). Interestingly, the quadruple hrs1;hho1;hho2;hho3 mutant does not display any ROS accumulation changes in these conditions (Fig. 7A), which could be explained by (i) a modification of their ROS-scavenging processes (verified below) or (ii) by referring to the NO3− transport phenotypes. Indeed nitrate transport-related phenotypes of the HHO overexpressors are displayed in –N conditions (Fig. 1) and the molecular phenotypes of the mutants are manifested in +N conditions (Fig. 2B). Thus, we rationalized that it might be the same with ROS-related phenotypes in the hrs1/hho mutants.

Fig. 7.

ROS are produced early after nitrogen deprivation, regulated by HRS1, and crucial for the NSR. (A) H2O2 production after N deprivation. Plants were grown in non-sterile hydroponics for 6 weeks on N-containing medium. Thereafter, the medium was shifted to –N conditions or +N as a control for 6 h. H2O2 accumulation was measured using Amplex® Red (see the Materials and methods). Values are means ±SE (n=6). Different letters indicate significant differences (Student’s t-test, P<0.05). (B) ROS-scavenging treatment represses NSR sentinel genes in hho mutants. Plants were grown in sterile hydroponic conditions on N-containing medium for 14 d. They were then N deprived for 3 d and treated with 5 mM KI and 5 mM mannitol. Plants kept on the same renewed medium were used as control. Values are means ±SE (n=4).

As we observed that ROS accumulate early in response to N starvation (Fig. 7A), we decided to treat the double and quadruple hrs1;hho1;hho2;hho3 mutants with KI–mannitol (Fig. 7B). We found that ROS-scavenging treatment indeed represses NSR sentinel genes in the hrs1/hho mutants to almost the level of the WT, totally abolishing the NSR and the mutant phenotype (Fig. 7B). These results show that ROS-scavenging agents are able to overcome the mutant phenotype.

We then decided to further analyze the ROS-related mutant phenotypes in –N→+N transfer conditions (Fig. 8A). First, we measured the APX, GPX, and GR activities in plants (WT and the quadruple hrs1;hho1;hho2;hho3 mutant) grown for 4 weeks on +N (1 mM NH4NO3) then transferred to either +N (5 mM KNO3) or –N (5 mM KCl mock control) for 3 d, and finally treated with 5 mM KNO3 for 3 h (Fig. 8A). We recorded that N provision to plants pre-treated with +N conditions did not change ROS-scavenging activities. However, when plants are treated with N after an N starvation period, the quadruple hrs1;hho1;hho2;hho3 mutant displays a significantly higher activity of APX and GPX (~2-fold) compared with WT plants. This marks the launch of a probable H2O2 detoxification program, being enhanced in the hho mutant as compared with the WT (Fig. 8A). This also provides a probable explanation for the mild phenotypes recorded in the hho mutant for H2O2 contents (Fig. 7A).

Fig. 8.

The hho quadruple mutant displays ROS-related phenotypes following N treatment (A) Ascorbate peroxidase (APX), glutathione peroxidase (GPX), and glutathione reductase (GR) activities of the WT and hho quadruple mutant. Plants were grown for 4 weeks in hydroponic conditions +N (1 mM NH4NO3) then transferred to either +N (5 mM KNO3) or –N (5 mM KCl mock control) for 3 d, and finally treated with 5 mM KNO3 for 3 h. (B) NBT staining of the WT and the quadruple hho mutant. Plants were grown on Petri dishes for 2 weeks on 0.5 mM NH4NO3. Fresh plants were harvested and directly stained with NBT. Leaves of the mutant plants display a strong decrease in NBT coloration, reporting a defect in superoxide accumulation. (C) ROS signature genes are controlled by NO3− and by HRS1 entry into the nucleus. ROS signature genes (Vaahtera et al., 2014) were clustered on HRS1 TARGET data (Fig. 5B). ROS signature genes were color-coded according to their responsiveness to different ROS (red, hydrogen peroxide; blue, singlet oxygen; purple, superoxide; cyan, ozone) and according to statistical analysis. ANOVA followed by a Tukey test was performed. If a gene was significantly regulated (P-value <0.05) based on an ANOVA or a Tukey test [nitrate, DEX, nitrate×DEX, or a difference in the Tukey analysis (±DEX in the +N or –N context)], a black square is reported in the clustering.

To continue our study of the quadruple hrs1;hho1;hho2;hho3 mutant, we performed ROS staining using DAB (3,3′-diaminobenzidine) and NBT dyes. Notwithstanding that DAB did not yield reproducible results, we observed with NBT staining a strong deviation from the WT in the shoots of the quadruple mutant (Fig. 8B). On N-containing media (steady-state N provision), we observed a very weak coloration in the quadruple mutant, supposedly marking a lower accumulation of O2· − or potentially higher detoxification activity. Although, contrary to our expectation, the Amplex® Red and DAB assays did not show a significant increase in the mutant H2O2 content, the concomitant enhanced peroxidase (APX and GPX) activities (Fig. 8A) can simply explain this distorted response. The higher scavenging activity may redress the rapid increase of H2O2 content to normal (Fig. 7A) while, on the other hand, it may deplete the initially normal level of O2· − (Fig. 8A). Further studies will be necessary to decipher these complex ROS species dynamics.

Interestingly, the above observations are consistent with our overexpression of HHOs in the cell-based TARGET assay (Fig. 5B). Indeed, as stated above, the major cluster of HHO-regulated genes harboring a very high enrichment for ROS-related genes is cluster #2 (Fig. 5B). This cluster contains genes being induced by NO3− in –DEX conditions and repressed upon HRS1 translocation to the nucleus (+NO3−, +DEX). This result is exactly what we observe in whole plants; that is, N provision triggers ROS accumulation to be repressed in the overexpressors (Fig. 7A). We also measured mRNA accumulation of ROS-related genes predicted to be direct targets of HRS1 (Fig. 5) in the quadruple mutant in different N conditions. Results in Supplementary Fig. S8 show that the hho quadruple mutation significantly affects ROS-related genes, including NADPH oxidase, catalases, MDAR, etc. in an N-varying context. Finally, we retrieved key signature genes of the ROS response (different ROS species) defined by a meta-analysis (Vaahtera et al., 2014). To evaluate the control of HRS1 on ROS signature genes, we clustered the expression profile of this gene list and plotted: (i) if the gene reports the action of H2O2, singlet oxygen, O2· − , or ozone; and (ii) if the gene is controlled by NO3−, HRS1 nuclear entrance (DEX), or the interaction of both (Fig. 8C). This analysis again pointed to the fact that NO3−, HRS1, and their combinations influence ROS signature genes for H2O2 (four genes), singlet oxygen (three genes), and O2· − (one gene) (Fig. 8C). Despite the efforts to define ROS-specific markers (Gadjev et al., 2006; Rosenwasser et al., 2013), the highly transformable nature of ROS prevents us from reaching firm conclusions. However, these results are in accordance with our in planta observations and are another argument showing that HRS1/HHOs are involved in the control of ROS homeostasis in Arabidopsis.

In summary, we show that members of the HHO TF family directly control NSR sentinels (Figs 1, 2; Supplementary Figs S6, S7). We also report that upon N starvation, ROS are produced and participate in NSR activation. To a certain extent, ROS accumulation can also explain phenotypes observed in HHO-affected genotypes. Thus, we conclude that HRS1 and HHO1 are able to reduce ROS accumulation and potentially repress the NSR through a parallel ROS-dependent branch of this signaling pathway (Figs 7, 8; Supplementary Fig. S8).

Discussion

To date, the role of ROS as a potential messenger in the NSR was hypothesized by several groups (Shin et al., 2005; Krapp et al., 2011) but, to our knowledge, never formally demonstrated. Previously, Shin and Schachtman (2004) demonstrated that upon K starvation, ROS accumulation through the action of RHD2 (NADPH oxidase) was important to sustain the full transcriptional activation of K+ transporters. The same group (Shin et al., 2005) also demonstrated that –P and –N treatments trigger the production of ROS. However, the direct role of ROS in the NSR has so far been elusive. In the current work, we present evidence that preventing the production and/or accumulation of ROS during N starvation strongly represses the response of the NSR sentinel genes (Figs 6, 7B; Supplementary Fig. S5). Taken together, the above-mentioned research (Shin and Schachtman, 2004; Shin et al., 2005; Krapp et al., 2011) and that by others (Muller et al., 2015; Hoehenwarter et al., 2016; Balzergue et al., 2017; Mora-Macias et al., 2017) strongly support that ROS are potential central hubs of the nutrient starvation responses. Because plants are able to distinguish between different nutritional deprivations, the next challenge will be to understand how the nutritional specificity of ROS production is detected by cells. How is the plant able to detect the ROS signal coming from N rather than a K deficiency? Some clue probably lies in the tissular and cellular specificity of ROS production (Shin et al., 2005). Different types of ROS might presumably have different outcomes with regards to the NSR. For instance, whereas H2O2 induces NRT2.1 expression (Bellegarde et al., 2019), nitric oxide (NO), on the other hand, inhibits it (Frungillo et al., 2014). Besides their type, the subcellular origin of ROS might also determine the specificity of each pathway (He et al., 2018). It is noteworthy that H2O2 can directly pass from chloroplasts to the nucleus to regulate gene expression (Exposito-Rodriguez et al., 2017). In addition, ROS induce not only chloroplast relocalization towards the nucleus (Ding et al., 2019), but also stromule formation, leading to the development of a direct nucleus–chloroplastic interaction (Caplan et al., 2015). Can the plastids sense a lack of N and then increase their ROS production accordingly? N assimilation indeed occurs in the plastids where NO2− can enter to be reduced to NH4+ and produce amino acids. Many studies revealed an interconnection between C (carbon) and N status in plants (Malamy and Ryan, 2001; Coruzzi and Zhou, 2001; Gutierrez et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2016; Ruffel et al., 2020). It is thus worth further exploring the differential response to N deficiency in roots versus shoots. Remarkably, we observed a difference in ROS type and accumulation between the roots and the leaves in the hho mutant (Figs 7A, 8B). Also, unlike our own (Fig. 7A) and previous findings (Shin et al., 2005; Jung et al., 2018) which corroborate an increase in H2O2 content in N-starved roots, the H2O2 level was rather slightly decreased in leaves after N starvation (Bieker et al., 2019). Also, roots and shoots respond differentially to ROS (ozone) treatment (Evans et al., 2005). Recently, it was proposed that ROS might be the integrator that connects N and C signaling (Chaput et al., 2020).

One could also consider that ROS production is an independent and unspecific branch enhancing any kind of nutrient deficiencies whose specificities are encoded by genetic factors [as for the phosphate starvation response (PSR); Puga et al., 2014]. Those genetic specificities can largely explain why P starvation enhances HRS1/HHO expression while N starvation has a repressive effect on their expression, although ROS are being produced in both cases (Maeda et al., 2018; Ueda et al., 2020). Several studies have revealed crosstalk between N and P signaling and that the NSR and PSR are tightly interconnected (Medici et al., 2015, 2019; Kiba et al., 2018; Maeda et al., 2018; Hu and Chu, 2020; Ueda et al., 2020). However, more investigations are needed in order to understand, for example, how ROS are perceived during a combined N and P depletion. However, we also need to ask what are the molecular players and events involved downstream of ROS production in response to nutrient deficiency.

Regarding the NSR, the answer might consist of CC-type glutaredoxins. Remarkably, two independent studies have recently reported that members of CC-type glutaredoxins (aka ROXYs) are differentially expressed in response to variable availability of nitrate (Patterson et al., 2015; Jung et al., 2018). Intriguingly, these ROXY members reveal opposite responses not only to nitrate abundance but also towards oxidative stress (Jung et al., 2018). In other words, ROXYs can be classified into two groups: the first class, which is induced by NO3− and repressed by ROS, represses NRT2 expression; and the second, which is induced by N starvation and ROS, induces in its turn NRT2 expression (Patterson et al., 2015; Jung et al., 2018). Rouhier et al. (2008) suggested that different structural and biochemical properties and therefore different functions of GRX in plants are the predictable result of their huge number compared with other organisms and of the low conservation of their sequences, particularly around the active site. These remarkable breakthroughs prompted us to investigate how CC-type GRXs are regulated by HHO TFs and how this regulation would fit our proposed model. To answer these questions, we drilled down through our TARGET data but also through the transcriptomes of the hrs1;hho1 double mutant and of the overexpressor lines (Medici et al., 2015; Kiba et al., 2018). Although the two ROXY classes respond differently to NO3− and ROS, some of them are regulated by HHOs in a way that promotes the same fate, namely NRT2 repression. For example, ROXY15 (GRXS8) and 17 (GRXS6) which act as repressors of NRT2, are up-regulated by HHOs. On the other hand, the NRT2 activators ROXY8 (GRXC14) and 9 (GRXC13/CEPD2) are repressed by HHOs. Together, our observations shed light on a new mechanism by which HHO TFs regulate NRT2 expression and which in its turn strengthens our initial model that the nitrate-induced HHOs repress NSR directly by regulating NRT2 activity but also indirectly via ROS inhibition. With these new findings, we gained insight into how ROS might affect NSR marker expression as ROXYs are most likely to be the mediators of ROS signaling in this pathway. It is well established that GRXs are involved in oxidative stress responses mostly via reducing disulfide bonds of their target proteins (Rouhier et al., 2008). Jung et al. (2018) proposed that similar mechanisms might be used by ROXYs in order to adapt TGA1/4 TF activity. Indeed, those redox-sensitive TFs (Despres et al., 2003) are known not only to be regulators of the PNR by controlling NRT2.1/NRT2.2 expression (Alvarez et al., 2014, 2019) but also to interact with many ROXY members (Ndamukong et al., 2007; Li et al., 2009; Murmu et al., 2010; Zander et al., 2012).

The second factor found in this work to be a strong regulator of NSR sentinel genes is the TF HRS1. These findings are in agreement with recent independent investigations (Kiba et al., 2018; Maeda et al., 2018). HRS1 was previously found to control the P response of primary root development (Liu et al., 2009; Medici et al., 2015) and to control germination via an abscisic acid (ABA)-dependent pathway (Wu et al., 2012). HRS1 and its close HHO homolog genes are also very well known to be among the most NO3−-regulated genes in Arabidopsis (Wang et al., 2004; Krouk et al., 2010b; Canales et al., 2014). The very strong control of HHOs by NO3− seems to be important for its functions. Previously, we showed that HRS1 NO3− regulation is necessary to integrate the NO3− and the PO43− signal, and to trigger the appropriate primary root response (Medici et al., 2015). Herein, we show by TF perturbation in planta (overexpressors and mutants) or in plant cells (TARGET), and by DNA-binding assays (EMSA and DAP-seq), that HRS1 directly represses NRT2.4 and NRT2.5 genes. These genes are activated upon N starvation to retrieve NO3− traces in the soil solution. Thus, it seems critical for the plant to repress them (by HRS1/HHO TF activity) when NO3− is provided to N-starved plants (Fig. 2). In this work, we generated a genotype missing four HHOs (HRS1, HHO1, HHO2, and HHO3). This genotype is unable to fully repress the NRT2.4 and NRT2.5 loci (Kiba et al., 2012; Lezhneva et al., 2014). These four mutations led to an important enhancement of HATS activity (~2.5-fold at 100 µM of external NO3−), with a very obvious growth enhancement (Fig. 4). This opens up original perspectives to develop genotypes with increased transport capacities in crops, and improve NUE with a potential long-term impact on global warming. Similarly, a very recent study showed that N deficiency-induced OsNLP1 enhances NUE and plant growth by up-regulating multiple N uptake and assimilation genes (Alfatih et al., 2020). This includes genes involved in the NSR and NO3− transport (NRT2.4, NRT2.1, and NRT1.1). Based on these inputs, one can postulate that HHOs might also regulate NSR via repressing NLP1 especially as its promoter is recognized in vivo by HHO2 (Kiba et al., 2018).

In conclusion, the model that we propose (Fig. 9) defines two new kinds of molecular players (the TFs HRS1/HHOs and ROS) in the control of the plant NSR (+N→–N). We show that ROS are produced upon NSR and that this response is necessary for NSR sentinel gene activation. We also show that HRS1 and HHO1 (i) control ROS accumulation in response to NSR and (ii) directly repress NSR sentinel genes (NRT2.4 and NRT2.5).

Fig. 9.

Proposed model of the regulation of NSR by HHOs and ROS. Under –N conditions, ROS are produced and are needed for induction of the NSR. When nitrogen is present in the media, HRS1 and its homologs are rapidly and highly expressed to repress the NSR either directly by regulating NRT2 and GDH3 promoter activities or indirectly by reducing ROS production.

Supplementary data

The following supplementary data are available at JXB online.

Fig. S1. NRT2.4 is down-regulated by HRS1 and HHO1.

Fig. S2. Characterization of the mutants and overexpressor lines.

Fig. S3. The hrs1;hho1 double mutant displays a growth phenotype in +N conditions.

Fig. S4. The HHO subfamily is involved in repressing genes responsible for NO3− transport.

Fig. S5. RBOH (NADPH oxidase) mutants are affected in NSR marker gene expression.

Fig. S6. Identification of a new HRS1 cis-regulatory element and binding of HRS1 to NRT2.4 and NRT2.5 promoters.

Fig. S7. HHO binding evidence in NR2.4, NRT2.5, and GDH3 promoters.

Fig. S8. The quadruple hho mutant affects ROS-related gene expression.

Dataset S1. TARGET data.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Agence Nationale de la Recherche (IMANA ANR-14-CE19-0008 with a doctoral fellowship to AS), by CNRS (LIA- CoopNet and IRP- CoopNet2) to GK. The work on the TARGET experiments was supported by NIH Grant R01-GM121753 to GC and NIH NRSA Fellowship- GM095273 to AM-C. ROS-related enzymatic activities were measured by the Biochemistry Phenotyping Platform (PPB, at CIRAD-AGAP, Montpellier France). We are very gratful to Dr Alexandre Martiniere for sharing NADPH oxidase mutants.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- GDH3

glutamate dehydrogenase 3

- HHO

HRS1 homolog

- HRS1

hypersensitive to low Pi-elicited primary root shortening 1

- NSR

nitrogen starvation response

- NRT

nitrate transporter

- NUE

N-use efficiency

- PNR

primary nitrate response

- PSR

phosphate starvation response

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- TF

transcription factor

Author contributions

GK, BL, and GC designed the project. AS, AM, WS, FM, ACV, AMC, JL, and GK performed the experiments and analyzed the data. AS, SR, FG, HR, BL, and GK contributed to the study design during the project course. GK and AS wrote the manuscript with revision by all the authors.

Data availability

All data and materials will be made available to researchers upon request.

References

- Alboresi A, Gestin C, Leydecker MT, Bedu M, Meyer C, Truong HN. 2005. Nitrate, a signal relieving seed dormancy in Arabidopsis. Plant, Cell & Environment 28, 500–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfatih A, Wu J, Zhang ZS, Xia JQ, Jan SU, Yu LH, Xiang CB. 2020. Rice NIN-LIKE PROTEIN 1 rapidly responds to nitrogen deficiency and improves yield and nitrogen use efficiency. Journal of Experimental Botany 71, 6032–6042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez JM, Moyano TC, Zhang T, et al. 2019. Local changes in chromatin accessibility and transcriptional networks underlying the nitrate response in Arabidopsis roots. Molecular Plant 12, 1545–1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez JM, Riveras E, Vidal EA, et al. 2014. Systems approach identifies TGA1 and TGA4 transcription factors as important regulatory components of the nitrate response of Arabidopsis thaliana roots. The Plant Journal 80, 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez JM, Schinke AL, Brooks MD, Pasquino A, Leonelli L, Varala K, Safi A, Krouk G, Krapp A, Coruzzi GM. 2020. Transient genome-wide interactions of the master transcription factor NLP7 initiate a rapid nitrogen-response cascade. Nature Communications 11, 1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araus V, Vidal EA, Puelma T, Alamos S, Mieulet D, Guiderdoni E, Gutiérrez RA. 2016. Members of BTB gene family of scaffold proteins suppress nitrate uptake and nitrogen use efficiency. Plant Physiology 171, 1523–1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey TL, Boden M, Buske FA, Frith M, Grant CE, Clementi L, Ren J, Li WW, Noble WS. 2009. MEME SUITE: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Research 37, W202–W208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balzergue C, Dartevelle T, Godon C, et al. 2017. Low phosphate activates STOP1-ALMT1 to rapidly inhibit root cell elongation. Nature Communications 8, 15300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargmann BO, Marshall-Colon A, Efroni I, Ruffel S, Birnbaum KD, Coruzzi GM, Krouk G. 2013. TARGET: a transient transformation system for genome-wide transcription factor target discovery. Molecular Plant 6, 978–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellegarde F, Maghiaoui A, Boucherez J, Krouk G, Lejay L, Bach L, Gojon A, Martin A. 2019. The chromatin factor HNI9 and ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL5 maintain ROS homeostasis under high nitrogen provision. Plant Physiology 180, 582–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieker S, Riester L, Doll J, Franzaring J, Fangmeier A, Zentgraf U. 2019. Nitrogen supply drives senescence-related seed storage protein expression in rapeseed leaves. Genes 10, 72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canales J, Moyano TC, Villarroel E, Gutiérrez RA. 2014. Systems analysis of transcriptome data provides new hypotheses about Arabidopsis root response to nitrate treatments. Frontiers in Plant Science 5, 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan JL, Kumar AS, Park E, Padmanabhan MS, Hoban K, Modla S, Czymmek K, Dinesh-Kumar SP. 2015. Chloroplast stromules function during innate immunity. Developmental Cell 34, 45–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castaings L, Camargo A, Pocholle D, et al. 2009. The nodule inception-like protein 7 modulates nitrate sensing and metabolism in Arabidopsis. The Plant Journal 57, 426–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro Marin I, Loef I, Bartetzko L, Searle I, Coupland G, Stitt M, Osuna D. 2010. Nitrate regulates floral induction in Arabidopsis, acting independently of light, gibberellin and autonomous pathways. Planta 233, 539–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty S, Hill AL, Shirsekar G, Afzal AJ, Wang GL, Mackey D, Bonello P. 2016. Quantification of hydrogen peroxide in plant tissues using Amplex Red. Methods 109, 105–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaput V, Martin A, Lejay L. 2020. Redox metabolism: the hidden player in carbon and nitrogen signaling? Journal of Experimental Botany 71, 3816–3826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Yao Q, Gao X, Jiang C, Harberd NP, Fu X. 2016. Shoot-to-root mobile transcription factor HY5 coordinates plant carbon and nitrogen acquisition. Current Biology 26, 640–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury FK, Rivero RM, Blumwald E, Mittler R. 2017. Reactive oxygen species, abiotic stress and stress combination. The Plant Journal 90, 856–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson DT, Gojon A, Saker LR, Wiersema PK, Purves JV, Tillard P, Arnold GM, Paams AJM, Waalburg W, Stulen I. 1996. Nitrate and ammonium influxes in soybean (Glycine max) roots: direct comparison of 13N and 15N tracing. Plant, Cell & Environment 19, 859–868. [Google Scholar]

- Coruzzi GM, Zhou L. 2001. Carbon and nitrogen sensing and signaling in plants: emerging ‘matrix effects’. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 4, 247–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford NM, Glass ADM. 1998. Molecular and physiological aspects of nitrate uptake in plants. Trends in Plant Science 3, 389–395. [Google Scholar]

- Cuin TA, Shabala S. 2007. Compatible solutes reduce ROS-induced potassium efflux in Arabidopsis roots. Plant, Cell & Environment 30, 875–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis MD, Grossniklaus U. 2003. A gateway cloning vector set for high-throughput functional analysis of genes in planta. Plant Physiology 133, 462–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Despres C, Chubak C, Rochon A, Clark R, Bethune T, Desveaux D, Fobert PR. 2003. The Arabidopsis NPR1 disease resistance protein is a novel cofactor that confers redox regulation of DNA binding activity to the basic domain/leucine zipper transcription factor TGA1. The Plant Cell 15, 2181–2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding X, Jimenez-Gongora T, Krenz B, Lozano-Duran R. 2019. Chloroplast clustering around the nucleus is a general response to pathogen perception in Nicotiana benthamiana. Molecular Plant Pathology 20, 1298–1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans NH, McAinsh MR, Hetherington AM, Knight MR. 2005. ROS perception in Arabidopsis thaliana: the ozone-induced calcium response. The Plant Journal 41, 615–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exposito-Rodriguez M, Laissue PP, Yvon-Durocher G, Smirnoff N, Mullineaux PM. 2017. Photosynthesis-dependent H2O2 transfer from chloroplasts to nuclei provides a high-light signalling mechanism. Nature Communications 8, 49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forde BG, Walch-Liu P. 2009. Nitrate and glutamate as environmental cues for behavioural responses in plant roots. Plant, Cell & Environment 32, 682–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foyer CH, Noctor G. 2013. Redox signaling in plants. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 18, 2087–2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco R, Panayiotidis MI, Cidlowski JA. 2007. Glutathione depletion is necessary for apoptosis in lymphoid cells independent of reactive oxygen species formation. Journal of Biological Chemistry 282, 30452–30465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frungillo L, Skelly MJ, Loake GJ, Spoel SH, Salgado I. 2014. S-nitrosothiols regulate nitric oxide production and storage in plants through the nitrogen assimilation pathway. Nature Communications 5, 5401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadjev I, Vanderauwera S, Gechev TS, Laloi C, Minkov IN, Shulaev V, Apel K, Inzé D, Mittler R, Van Breusegem F. 2006. Transcriptomic footprints disclose specificity of reactive oxygen species signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology 141, 436–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gansel X, Muños S, Tillard P, Gojon A. 2001. Differential regulation of the NO3– and NH4+ transporter genes AtNrt2.1 and AtAmt1.1 in Arabidopsis: relation with long-distance and local controls by N status of the plant. The Plant Journal 26, 143–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautrat P, Laffont C, Frugier F, Ruffel S. 2020. Nitrogen systemic signaling: from symbiotic nodulation to root acquisition. Trends in Plant Science [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber BD, Giehl RF, Friedel S, von Wirén N. 2013. Plasticity of the Arabidopsis root system under nutrient deficiencies. Plant Physiology 163, 161–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan P, Ripoll JJ, Wang R, Vuong L, Bailey-Steinitz LJ, Ye D, Crawford NM. 2017. Interacting TCP and NLP transcription factors control plant responses to nitrate availability. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 114, 2419–2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez RA, Lejay LV, Dean A, Chiaromonte F, Shasha DE, Coruzzi GM. 2007. Qualitative network models and genome-wide expression data define carbon/nitrogen-responsive molecular machines in Arabidopsis. Genome Biology 8, R7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han M, Okamoto M, Beatty PH, Rothstein SJ, Good AG. 2015. The genetics of nitrogen use efficiency in crop plants. Annual Review of Genetics 49, 269–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He H, Van Breusegem F, Mhamdi A. 2018. Redox-dependent control of nuclear transcription in plants. Journal of Experimental Botany 69, 3359–3372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho CH, Lin SH, Hu HC, Tsay YF. 2009. CHL1 functions as a nitrate sensor in plants. Cell 138, 1184–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoehenwarter W, Mönchgesang S, Neumann S, Majovsky P, Abel S, Müller J. 2016. Comparative expression profiling reveals a role of the root apoplast in local phosphate response. BMC Plant Biology 16, 106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu B, Chu C. 2020. Nitrogen–phosphorus interplay: old story with molecular tale. New Phytologist 225, 1455–1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu HC, Wang YY, Tsay YF. 2009. AtCIPK8, a CBL-interacting protein kinase, regulates the low-affinity phase of the primary nitrate response. The Plant Journal 57, 264–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung JY, Ahn JH, Schachtman DP. 2018. CC-type glutaredoxins mediate plant response and signaling under nitrate starvation in Arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biology 18, 281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiba T, Feria-Bourrellier AB, Lafouge F, et al. 2012. The Arabidopsis nitrate transporter NRT2.4 plays a double role in roots and shoots of nitrogen-starved plants. The Plant Cell 24, 245–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiba T, Inaba J, Kudo T, et al. 2018. Repression of nitrogen starvation responses by members of the Arabidopsis GARP-type transcription factor NIGT1/HRS1 subfamily. The Plant Cell 30, 925–945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiba T, Krapp A. 2016. Plant nitrogen acquisition under low availability: regulation of uptake and root architecture. Plant & Cell Physiology 57, 707–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krapp A, Berthomé R, Orsel M, Mercey-Boutet S, Yu A, Castaings L, Elftieh S, Major H, Renou JP, Daniel-Vedele F. 2011. Arabidopsis roots and shoots show distinct temporal adaptation patterns toward nitrogen starvation. Plant Physiology 157, 1255–1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krouk G. 2017. Nitrate signalling: calcium bridges the nitrate gap. Nature Plants 3, 17095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krouk G, Carré C, Fizames C, Gojon A, Ruffel S, Lacombe B. 2015. GeneCloud reveals semantic enrichment in lists of gene descriptions. Molecular Plant 8, 971–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krouk G, Crawford NM, Coruzzi GM, Tsay YF. 2010a. Nitrate signaling: adaptation to fluctuating environments. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 13, 266–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krouk G, Mirowski P, LeCun Y, Shasha DE, Coruzzi GM. 2010b. Predictive network modeling of the high-resolution dynamic plant transcriptome in response to nitrate. Genome Biology 11, R123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leclercq J, Martin F, Sanier C, Clément-Vidal A, Fabre D, Oliver G, Lardet L, Ayar A, Peyramard M, Montoro P. 2012. Over-expression of a cytosolic isoform of the HbCuZnSOD gene in Hevea brasiliensis changes its response to a water deficit. Plant Molecular Biology 80, 255–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejay L, Tillard P, Lepetit M, Olive Fd, Filleur S, Daniel-Vedele F, Gojon A. 1999. Molecular and functional regulation of two NO3– uptake systems by N- and C-status of Arabidopsis plants. The Plant Journal 18, 509–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leran S, Edel KH, Pervent M, Hashimoto K, Corratgé-Faillie C, Offenborn JN, Tillard P, Gojon A, Kudla J, Lacombe B. 2015. Nitrate sensing and uptake in Arabidopsis are enhanced by ABI2, a phosphatase inactivated by the stress hormone abscisic acid. Science Signaling 8, ra43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lezhneva L, Kiba T, Feria-Bourrellier AB, Lafouge F, Boutet-Mercey S, Zoufan P, Sakakibara H, Daniel-Vedele F, Krapp A. 2014. The Arabidopsis nitrate transporter NRT2.5 plays a role in nitrate acquisition and remobilization in nitrogen-starved plants. The Plant Journal 80, 230–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Lauri A, Ziemann M, Busch A, Bhave M, Zachgo S. 2009. Nuclear activity of ROXY1, a glutaredoxin interacting with TGA factors, is required for petal development in Arabidopsis thaliana. The Plant Cell 21, 429–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Krouk G, Coruzzi GM, Ruffel S. 2014. Finding a nitrogen niche: a systems integration of local and systemic nitrogen signalling in plants. Journal of Experimental Botany 65, 5601–5610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Yang H, Wu C, Feng J, Liu X, Qin H, Wang D. 2009. Overexpressing HRS1 confers hypersensitivity to low phosphate-elicited inhibition of primary root growth in Arabidopsis thaliana. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 51, 382–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu KH, Niu Y, Konishi M, et al. 2017. Discovery of nitrate–CPK–NLP signalling in central nutrient–growth networks. Nature 545, 311–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H, Zhao J, Feng S, Qiao K, Gong S, Wang J, Zhou A. 2020. Heterologous expression of nitrate assimilation related-protein DsNAR2.1/NRT3.1 affects uptake of nitrate and ammonium in nitrogen-starved Arabidopsis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Q, Tang RJ, Zheng XJ, Wang SM, Luan S. 2015. The calcium sensor CBL7 modulates plant responses to low nitrate in Arabidopsis. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 468, 59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]