Abstract

Cancers must alter their metabolism to satisfy the increased demand for energy and building blocks that are required to create a rapidly growing tumor. Further, for cancer cells to thrive, they must also adapt to cope with an often changing tumor microenvironment that can present new metabolic challenges (ex. hypoxia) that are unfavorable for most other cells. As such, altered metabolism is now considered an emerging hallmark of cancer. Like many other malignancies, the metabolism of prostate cancer is considerably different compared to matched benign tissue. However, prostate cancers exhibit distinct metabolic characteristics that set them apart from many other tumor types. In this chapter, we will describe the known alterations in prostate cancer metabolism that occur during initial tumorigenesis and throughout the disease’s progression. In addition, we will highlight upstream regulators that control these metabolic changes. Finally, we will discuss how this new knowledge is being leveraged to improve patient care through the development of both novel biomarkers and new, metabolically targeted therapies.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, Metabolism, Androgen receptor, Imaging

Introduction

In the 1920s, Otto Warburg first described the ability of cancer cells to exhibit glycolysis even in the presence of oxygen (aerobic glycolysis), a phenomenon now commonly referred to as the Warburg effect [1,2]. Since then, the altered metabolism of cancers relative to benign tissue has been more broadly recognized and as such, is now considered one of the hallmarks of cancer [3]. Interestingly, while prostate cancers indeed have distinct metabolic phenotypes from normal prostate, they also exhibit atypical metabolism compared to many other cancer types. Hence, many of the generalities established for cancer metabolism are not pertinent for prostate cancer. But like many diseases, the metabolism of prostatic tumors is context and stage dependent.

The prostate is a reproductive gland, generating and releasing fluid that nourishes sperm. Sperm are nourished in large part by citrate that is produced and secreted from the luminal epithelial cells of the prostate. Luminal epithelial cells are able to produce and secrete large amounts of citrate as the result of a truncated tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle (also referred to as the citric acid or Krebs cycle) that is caused by the extraordinarily high levels of zinc that accumulate in these cells. To that end, the luminal epithelial cells of the prostate contain amongst the highest levels of zinc (~.8–1.5 mM) of any cell in the human body [4–9]. The high intracellular levels of zinc disrupt the TCA cycle by inhibiting the enzyme m-aconitase which converts citrate to isocitrate [7]. This truncated TCA cycle converts prostatic luminal epithelial cells from citrate-consuming to citrate-producing cells [7,10]. One of the first events to occur during the malignant transformation of prostate epithelial cells is a decrease in the expression of zinc transporters [11,12]. This results in decreased intracellular zinc accumulation and a derepression of aconitase and therefore the TCA cycle. As such, in contrast to what has been described for most cancers, the majority of prostate cancers exhibit high levels of glucose oxidation through increased TCA cycle flux (Figure 1).

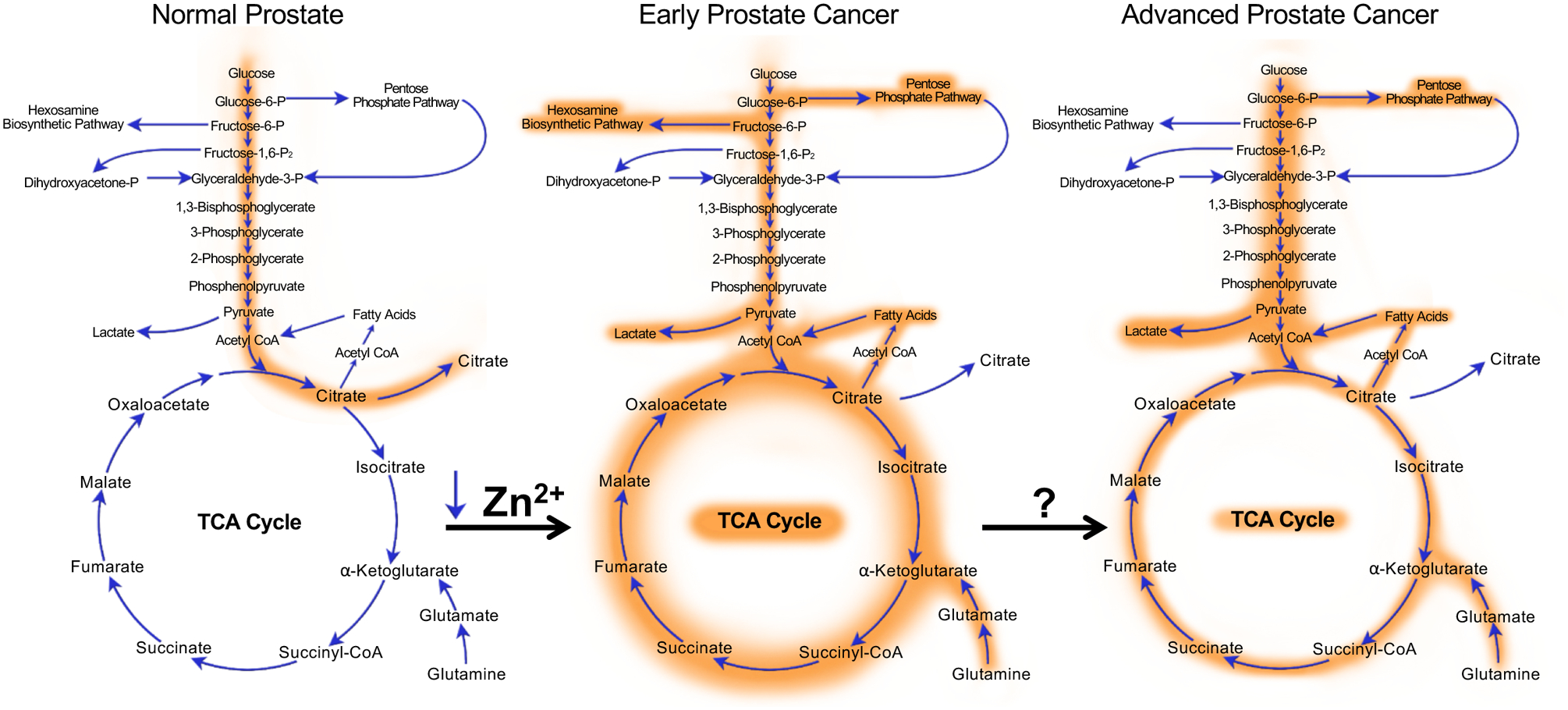

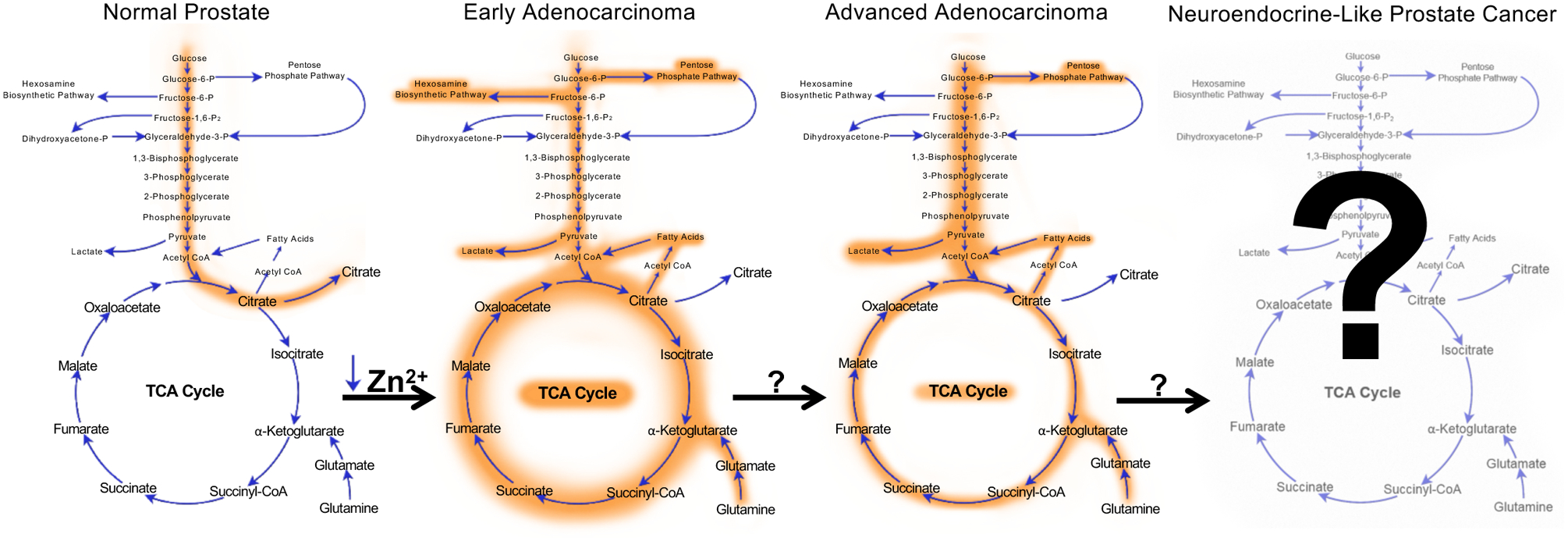

Figure 1. Evolution of prostate cancer metabolism.

Normal prostate epithelial cells exhibit a truncated TCA cycle that results in the increased production and secretion of citrate. During the initial transformation towards malignancy, intracellular concentrations of zinc drop causing a derepression of aconitase (the enzyme that converts citrate to isocitrate) and subsequent increased flux through the TCA cycle. Concurrently, cancer cells start to exhibit aerobic glycolysis, elevated glutaminolysis and increased flux through the hexosamine biosynthetic and pentose phosphate pathways. Interestingly, another hallmark of prostate cancers is the concurrent increases in both de novo lipogenesis and fatty acid oxidation. When prostate cancers progress into the late stages of the disease, the classic Warburg effect becomes more pronounced while some pathways, such as the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway, may reverse. While the initial metabolic transformation of prostatic cells has been well described to result from alterations such as the decreases in intracellular zinc concentrations, many of the drivers of the metabolic changes that occur in advanced prostate cancer remain poorly understood. Shown here is only a brief snapshot of central carbon metabolism.

While the shift towards increased glucose oxidation during transformation has been known for over 20 years, what has become clear is that prostate cancers co-opt a number of other important metabolic processes, described below, to help satisfy the increased energetic and biosynthetic demands of a rapidly growing tumor (Figure 1). Further, these metabolic changes continue to change throughout disease progression. For example, many advanced, lethal prostate cancers will eventually demonstrate increased glycolytic flux, similar to the classic Warburg effect (Figure 1). Importantly, cancer cells must also adapt to survive the harsh tumor microenvironment that evolves in part due to the increased metabolic waste produced from the cancers themselves. Beyond their contribution to the production of energy, building blocks and redox homeostasis, new research is emerging that indicates the increased uptake of many nutrients contributes directly to the synthesis of new signaling molecules that can function as oncogenic signals to reprogram the cells and promote disease progression.

Our understanding of which nutrients are used by tumors, how and when they are metabolized and the regulation of these metabolic processes is required to translate these observations towards clinical utility. Importantly, the chemical nature of metabolism makes it possible to develop biomarkers (ex. imaging) that can assess when certain pathways have been altered in patients and therefore identify men who could benefit from emerging, metabolically targeted therapies.

Here, we describe the metabolic alterations that occur during the initiation and progression of prostate cancer. Further, we will highlight how key signaling pathways (ex. AR, PI3K, MYC) as well as other factors such as changes in the tumor microenvironment regulate these processes. Finally, we will discuss the clinical significance of this field. Accordingly, we will summarize the new metabolic-targeted therapies that are being tested for the treatment of prostate cancer. Importantly, we will also outline the emerging approaches being used to monitor metabolism in patients and how these could guide future clinical trials.

Metabolic Reprogramming in Prostate Cancer

Glucose Metabolism

The specific metabolic phenotype of normal prostate epithelial cells includes the accumulation of high zinc concentrations (~3–10 fold higher than in other tissues) that subsequently lead to a truncated TCA cycle and increased citrate production (~30–50 fold higher than other tissues), decreased oxidative phosphorylation and low energy metabolism [13]. Such inefficient metabolism cannot meet the energy requirements for rapidly growing prostate cancer cells. To adjust, prostate cancer cells are reprogrammed to have an efficient, energy-generating metabolism during their initial transformation. A notable metabolic shift during this transformation is an increase the levels of citrate oxidation as the malignant glands contain significantly lower concentrations of zinc compared to normal cells [14]. This shift allows cells to oxidize citrate and produce energy via a functional TCA cycle. This metabolic alteration can also protect prostate cancer cells from cell death [15]. In normal prostate epithelial cells, zinc accumulation facilitates Bax-associated mitochondrial pore formation which promotes cytochrome c release from mitochondria and subsequent caspase cascades as well as an inhibition of the anti-apoptotic protein NFkB [16,17]. Conversely, prostate cancer cells as less susceptible to mitochondrial induced apoptosis in the presence of low zinc concentrations. As noted above, zinc transporters are an important contributor to intracellular zinc regulation. The expression of ZIPs is significantly decreased or often absent altogether in prostate cancer [12,18]. Interestingly, differences in ZIP expression may also explain in part some of the racial disparities observed for prostate cancer. A study comparing African American and Caucasians suggested that ZIPs are expressed less in African Americans, preventing them from maintaining normal intracellular zinc concentrations [19]. Although it is not entirely clear how ZIPs are downregulated during prostate cancer progression, one potential explanation is epigenetic repression. In prostate cancer cells, higher methylation levels have been observed in the promoter region for the gene encoding activating enhancer binding protein 2 alpha (AP-2 alpha), leading to the decreased expression of AP-2 alpha, an important transcription factor of ZIPs [20]. Given the known role of zinc in prostate metabolism, interest has risen in the use of zinc dietary supplements and the development of ZIP inhibitors to treat prostate cancer [18]. Due to the metabolic shift towards citrate oxidation, some metabolic intermediates and genes in TCA cycle are also increased/hyperactivated during early transformation. A recent integrative proteomics study revealed that the TCA pathway proteins citrate synthase, aconitate hydratase, 2-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex, succinate-CoA ligase, fumarate hydratase and malate dehydrogenase, were all upregulated in primary prostate cancer compared to benign prostatic hyperplasia [21]. Furthermore, the corresponding intermediate metabolites in TCA cycle like malate, fumarate, succinate and 2-hydroxyglutaric acid were significantly elevated in tumors, suggesting a dependence of primary prostate cancers on oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). Interestingly, because of the high OXPHOS in primary prostate cancers, only modest levels of glucose uptake and the Warburg effect are observed [22,23]. Consequently, [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) is a poor detector of primary prostate cancer.

Unlike most primary prostate cancers, late-stage prostate cancers can often be detected in FDG-PET scans. Accordingly, increased glycolytic metabolism has been correlated with disease progression and poor prognosis [24]. Though the exact mechanism of glucose metabolism regulation in prostate cancer has not been fully elucidated, emerging evidence suggests the regulation of multiple glycolytic enzymes in the advanced cancer stages.

Facilitative glucose transporter (GLUTs) control the first rate-limiting step of glucose metabolism by mediating glucose diffusion. To date, 14 members have been identified in the human GLUT family. Each are associated with different substrate affinities and tissue distributions. GLUT1 is overexpressed in several tumors including prostate cancer. High GLUT1 expression has been found elevated in prostate tissues compared to tumor-adjacent normal tissues and its expression is correlated with a shorted time to recurrence after radical prostatectomy [25,26]. Accordingly, higher expression of GLUT1 has been reported in androgen-independent prostate cancers [27]. Moreover, GLUT1 can be induced in a tissue-specific manner by androgens and glucose deprivation, which can help cancer cells survive in a low glucose environment [28]. Besides GLUT1, GLUT12 has also recently been shown to play a functional role in prostate cancer [29]. GLUT12 was required for androgen-induced glucose uptake and cell growth in LNCaP and VCaP cells. Further, it played a similar role in AR-negative PC-3 cells. Interestingly, GLUT12 subcellular trafficking was observed to be increased in multiple prostate cancer cell models, suggesting a functional regulation beyond mRNA and protein expression. Of note, other GLUT members such as GLUT3, 7 and 11 are reported to be overexpressed as well in prostate cancer [30]. However, the functional role of these transporters is less clear.

Hexokinases (HKs) catalyze the first irreversible step in glycolysis by converting glucose to glucose-6-phosphate (G6P). Out of the four isoforms identified, HK2 is a major contributor to the Warburg effect and is required for tumor growth. Recent work indicates that HK2 is significantly elevated in prostate tumors relative to normal tissue and it is significantly correlated to Gleason score [31,24,32,33]. However, dramatic variability in expression levels has been observed in individual CRPC patient samples, further evidence of the heterogeneity of prostate cancer [33]. Though our understanding of what increases HK2 expression during the disease evolution is incomplete, new findings have begun to reveal potential mechanisms of action. First, PTEN and p53 co-deletion/mutation have been correlated with high levels of HK2 in prostate cancer cell lines, xenograft and genetic mouse models and prostate cancer patient samples. On one hand, PTEN loss leads to mTOR signaling pathway activation and 4EBP1 phosphorylation, triggering cap-dependent translation of HK2 through facilitating the dissociation of 4EBP1 and 4IF4E [33]. On the other hand, HK2 expression can be further increased by decreased miR-143 expression, a miRNA whose biogenesis is promoted by p53 [34]. In support of these findings, a recent study revealed that increased HK2 expression and activity, caused by androgen deprivation, was associated with increased p-AKT in PTEN/p53 deficient mice [35]. AKT not only increased HK2 expression by mTORC1, but it also promoted the localization of HK2 to the mitochondria, increasing HK2 activity. Besides PTEN/p53, HK2 expression has been described to be regulated by EZH2 and PKA. EZH2 can upregulate HK2 and glycolysis in PC-3 cells through the inhibition of miR181b [36]. Whereas, PKA-CREB signaling can promote HK2 expression and glucose utilization following androgen treatment in LNCaP cells [37]. Importantly, systemic deletion of Hk2 in a genetic mouse model demonstrated a marked repression of tumor growth without any glucose homeostasis dysfunction in normal cells [38], suggesting a selective HK2 inhibitor could be exploited clinically with tolerant toxicities.

Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC) catalyzes the conversion of pyruvate to acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl CoA), thereby regulating the carbon flux from glycolysis into the TCA cycle. PDC is a multi-enzyme complex composed of three enzymes: pyruvate dehydrogenase (E1), dihydrolipoamide acetyltransferase (E2), and lipoamide dehydrogenase (E3). PDHA1 (E1 alpha subunit) is a major component of PDC. As such, PDHA1 plays a critical role in controlling the appropriate mitochondrial activity for the requirement of cell metabolism and growth. It is established that PDHA1 is regulated by phosphorylation [39,40]. PDHA1 can be phosphorylated at serine 293 by pyruvate dehydrogenase kinases (PDKs). PDKs inhibit PDC activity and therefore the TCA cycle. This shifts the cell’s metabolism away from OXPHOS and towards a Warburg effect. Conversely, dehydrogenase phosphatases (PDPs) can reverse such inhibition. Typically, PDKs are thought to be overexpressed in the glycolytic cancers [41]. In those cancers, the upregulated expression of PDKs partly inactivates PDC, and in turn reroutes pyruvate towards glycolysis and away from the mitochondrion for respiration. This metabolic alteration accelerates the Warburg effect and has frequently been associated with increased tumorigenesis. In agreement with this, Zhong et al. reported that reduced expression of PDHA1 in prostate cancer was correlated with poor prognosis [42]. Accordingly, knockout of PDHA1 significantly decreased mitochondrial OXPHOS but increased glycolysis, which contributed to fast tumor growth. Moreover, PDHA1 KO cells are able to expand a stem-like cell population, suggesting a potential role in chemotherapy resistance and migration. However, Chen et al. offered a different view by demonstrating the amplification and overexpression of PDHA1 and its phosphatase PDP1 in prostate cancer [43]. Here, the authors demonstrated that inhibition of PDC activity precluded the development of prostate cancer in mouse and human xenograft tumor models. They also provided evidence that compartmentalized PDCs have different functions, but that distinct pools could all still contribute to lipid biosynthesis for prostate cancer progression. For example, nuclear PDC promoted lipogenesis by regulating histone acetylation-mediated lipogenic gene expression [44]. Alternatively, mitochondrial PDC converted pyruvate to citrate for lipid anabolism. Taken together, it is still unclear whether PDHA1 and its regulators are tumor promotors or suppressors. Given the changing citrate-related metabolism during prostate cancer progression, it is very possible that PDC has context-dependent functions in prostate cancer.

Pyruvate kinase catalyzes the committed step that transfers the phosphate group from phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) to ADP and generates pyruvate and ATP. PK muscle isozymes M1 and M2 are different splice variants encoded by the same gene, PKM. PKM2 is closely correlated to tumorigenesis. While PKM1 is expressed in differentiated tissues, PKM2 can be highly expressed in proliferating cells including embryonic and cancer cells [45]. Consistently, PKM2 is correlated with Gleason score and aggressive tumor types in prostate cancer [46,47]. There are some potential explanations for such isoform differences. First, PKM2 is an allosterically regulated isoform. Tetrameric PKM2 actively promotes the conversion of PEP into ATP and pyruvate. Conversely, dimeric PKM2 has low catalytic activity and instead promotes the entry of glycolytic intermediates into the glycolytic branch pathways such as the pentose phosphate pathway, by which cells can generate several key building blocks for their growth and proliferation [48]. This activity change is most evident in rapidly proliferating cells that appear to adhere to the Warburg effect. Second, PKM2 has non-metabolic functions that can modulate signaling and transcriptional activity to promote prostate cancer progression. For example, in CRPC, PKM2 may partner with KDM8 and co-translocate to the nucleus where they can function as coactivators of HIF-1α to upregulate glycolytic genes (GLUT1, HK2, PKM2, LDHA, etc.) and downregulate TCA cycle-related PDHA1 and B1 genes [49]. Moreover, the reciprocal regulation of PKM2 and HIF-1α could facilitate CRPC cell survival under hypoxic conditions and promote drug resistance [50,46,51]. Interestingly, PKM2 may also respond to extracellular signaling during prostate cancer metastasis. To that end, cancer associated fibroblasts can induce PKM2 post-translational modifications and nuclear translocation. In the nucleus, PKM2 worked with HIF-1α and DEC1 to deregulate miR-205 expression and in turn promote the epithelial mesenchymal transition [52]. Several PKM2 inhibitors and PKM2 tetramerization activators have been developed and exhibited efficacy, including overcoming drug resistance, in preclinical models [48,45]. Although little work has been done in this regards in prostate cancer, DASA-58, a PKM2 activator, did inhibit the lung metastasis of PC-3 cells in SCID mice [52], suggesting further studies are warranted in prostate cancer.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) catalyzes the reversible conversion of pyruvate and lactate. LDH (mostly LDHA) has been identified as a potential target for prostate cancer therapy [53,54]. LDH is a tetramer composed of two subunits, LDHA and LDHB. LDHA has a high affinity to pyruvate and thereby favors the reaction from pyruvate to lactate. Studies have suggested that in most tumors, increased LDHA is a hallmark for overactivated glycolysis and advanced progression. LDHA knockdown in prostate cancer cell not only inhibited cell growth but sensitized cells to radiotherapy [53,55]. Conversely, LDHB exhibits context-dependent roles [56]. A recent study indicated that LDHA and LDHB have opposite roles in prostate cancer [57]. Abnormal LDH, hyperphosphorylation and high expression of LDHA and low expression of LDHB correlated with short overall survival and time to biochemical recurrence patients with prostate cancer. They also found this aberrant LDH status was regulated by fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1) signaling. Mechanistically, FGFR1 can phosphorylate four tyrosine residues on LDHA to stabilize the protein. This enhanced glycolysis and reduced oxygen consumption. However, FGFR can also repress LDHB transcription by inhibiting TET1 (demethylase) expression and subsequently increasing DNA methylation at its promoter. Such coordinated regulation allows cancer cells to develop highly glycolytic metabolism.

As noted above, late-stage prostate cancer cells often increase glycolysis. Thus, lactate builds up as a byproduct of excessive anaerobic metabolism. To avoid lactate-mediated toxicities and apoptosis, cancer cells express high levels monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs) to ensure the rapid efflux of intracellular lactate. MCTs are well-studied membrane transport proteins that are responsible for the transmembrane shuttling of small carboxylates like lactate, pyruvate and short-chain fatty acids [58]. While the expression of MCTs vary in prostate cancer patients, more MCT has generally been correlated with more aggressive disease and poor prognosis [14].

Of the 14 isoforms identified, MCT1, 2 and 4 have been implicated in prostate cancer progression. MCT4 was first identified as a lactate exporter specially in highly glycolytic cells [59]. The elevated expression of MCT4 has been confirmed by several studies and its high expression is strongly associated with high glycolytic rates in prostate cancer including CRPC and neuroendocrine prostate cancer [31,60,55]. However, a clinical pathology study argued against the relationship between increasing MCT4 with lactate efflux (also MCT2) in prostate cancer [61]. They observed a significant increase of MCT4 (and MCT2) expression in the cytoplasm of prostate cancer cells rather than at the plasma membrane, indicating the roles of MCTs in prostate cancer may be involved in organelle function instead of lactate shuttling. Although further investigation is required to demonstrate why prostate cancer cells are reprogramed to express more MCT4, MCT4 does appear to be a useful prognostic factor and potential target for prostate cancer. Regarding the latter, knockdown of MCT4 significantly reduced PC-3 cell proliferation [55]. Moreover, targeting MCT4 by antisense oligonucleotides inhibited glycolysis, lactate production and cell proliferation in advanced prostate cancer [60]. Furthermore, high MCT4 expression may be involved in cancer–stroma interactions thought to facilitate prostate cancer progression (discussed further below the Section “Influence of the tumor microenvironment”) [62].

In addition to MCT4, MCT2 promotes prostate cancer progression [63,64]. Elevated MCT2 levels in prostate cancer have been linked to two differentially methylated regions at the SLC16A7 locus (gene encoding MCT2). One locus, upstream of the promoter, was hypermethylated in patient samples and responsible for full length MCT2 expression. The other locus, within an internal promoter, was recurrently demethylated in patient samples and subsequently induced the expression of an alternative isoform of MCT2. This isoform contains a different set of 5’-UTR translation signals that are most likely related to the high MCT2 expression. In addition to expression, MCT2 has been demonstrated to translocate to peroxisomes during disease progression, where it bound to Pex19 and enhanced beta-oxidation for malignant transformation. Together, these findings suggest that prostate cancer cells are able to adaptively increase MCT2 by epigenetic and compartmentalized regulation to meet their metabolic demands.

MCT1 is a controversial target for prostate cancer therapy. In some glycolytic cancers, an MCT1 inhibitor is being investigated in clinical trials due to its potent ability to reduce tumor growth in preclinical studies [58]. In prostate cancer, unfortunately, the benefit is still undefined. Howard et al. showed that pharmacological inhibition of MCT1 by α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamate (CHC, has a 10-fold selectivity for MCT1 compared to other MCTs) was associated with increased necrosis but not a significant difference in xenograft tumor size [65]. However, Pertega-Gomes et al. indicated that another MCT1 inhibitor, AR-C155858, decreased cell proliferation and increased cell apoptosis in Pten-deficient mouse tumor tissues without substantial side effects on benign tissue [31]. Regardless, the relationship between MCT1 and prostate cancer is complicated. Though a continued decrease of MCT1 has been found from benign prostatic tissue to metastatic prostate cancer, the expression of MCT1, MCT4 and CD147 were suggested to be markers of poor prognosis [61]. Interestingly, MCT1 expression is upregulated by hypoxia and glucose starvation [62,31], two common features of tumor microenvironments. However, it is unclear whether prostate cancer benefits from such MCT1 regulation.

The pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) is a glucose catabolic pathway that runs parallel to glycolysis. Evidence indicates that the PPP is important in cancer cell growth. This is largely due to PPP’s contribution to the production of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) and ribose 5-phosphate for scavenging of reactive oxygen species, reductive biosynthesis and supplying of nucleotide precursors [66,67]. A recent study showed that transketolase-like protein 1, an enzyme involved in the non-oxidative phase of the PPP, was altered throughout prostate cancer progression [68]. Of note, metastatic prostate cancer tissue had the highest TKTL1 expression, suggesting the potential role of TKTL1 in prostate cancer metastasis. Moreover, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD), the rate-limiting enzyme of the PPP, is also found to be a critical regulator for prostate cancer. Efrosini et al. revealed that G6PD is upregulated in prostate cancer and functionally was required for AR-mediated ROS modulation and cell growth [69]. At this time, the functional role of the PPP in metastasis is unknown.

Lipid Metabolism

Lipids are essential for many cell functions. They are used to form cell membranes and create membrane anchors, post-translationally modify proteins, promote various signaling pathways and can be used for energy storage. Lipid metabolic pathways produce compounds like fatty acids, steroids (including hormones and sterols like cholesterol), phospholipids and others. An important characteristic of prostate cancer cells is the dysregulation of lipid metabolic pathways. In normal cells, lipids are primarily acquired extracellularly, and can also be synthesized in specific tissues such as liver and adipose. Fatty acids produced in these tissues can be stored or transported to other areas. In cancer cells, there is an increase in de novo lipogenesis, which is necessary to accommodate the excessive cell growth and proliferation that occurs in cancer [70]. Prostate cancer cells undergo this characteristic shift from a reliance on extracellular fatty acid uptake to de novo lipogenesis. This shift is accompanied by the upregulation of multiple enzymes in the fatty acid synthesis pathway and is regulated by AR signaling. Upregulation of AR signaling in advancing cancer is accompanied by an increase in lipogenic enzymes [71]. This is largely dependent on the major lipogenesis transcription factor sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP) [72]. Interestingly, a feedback mechanism also exists where AR transcription is regulated by SREBP [73]. Beyond AR, additional genomic alterations observed in prostate cancer such as PTEN and PML co-deletion can also hyperactivate SREBP-mediated lipogenesis and subsequent prostate cancer progression [74]. Thus, SREBP may represent a downstream conduit of several oncogenic signaling networks in prostate cancer.

SREBPs are important transcription factors regulating fatty acid metabolism. In mammals, SREBP exists as SREBP-1a and SREPB-1c (two variants of a single gene), and SREBP-2 [75,76]. SREBP associates with SREBP cleavage-activating protein (SCAP) in the ER membrane. In response to a decrease in intracellular sterols, the SREBP-SCAP complex translocates to the Golgi apparatus, where SREBP is cleaved and activated, allowing it to move to the nucleus. SREBP controls the transcription of several genes involved in fatty acid and cholesterol synthesis, including ACLY, ACACA, SCD1, and FASN [77,78]. SREBP is upregulated in various cancers and can be activated by androgens in prostate cancer, due to the effect of AR on SCAP transcription [79]. SREBP can, in turn, further activate AR expression by binding to a sterol regulatory element (SRE) in the AR gene [80].

Lipids have an important role in forming the structure of outer and inner cell membranes. They are used to form the phospholipid bilayer as well as cholesterol-rich membrane rafts within the plasma membrane, which are important for intracellular signaling and trafficking. Since cancer cells experience rapid proliferation as well as increased synthesis and uptake of materials, membrane expansion is necessary. In addition, the metabolic shift to de novo lipogenesis in cancer increases lipid saturation, which may prevent cell death from oxidative damage [81]. The lipid rafts are microdomains within the plasma membrane that contain cholesterol, sphingolipids and transmembrane proteins [82]. Receptors like tyrosine kinase receptors in these lipid rafts can be activated by ligands to promote phosphorylation cascades, while the microdomain of the raft allows for the accumulation of intracellular scaffolding and adaptors and can protect against phosphatases [83,84]. Cholesterol in lipid rafts regulates AKT signaling, a major driver of prostate cancer progression [85]. There is also evidence suggesting that AR can interact with AKT at lipid rafts to promote oncogenic signaling [86]. However, AR’s extragenomic roles in prostate cancer are still debated.

Intracellular fat can be stored in lipid droplets. Lipid droplets are composed of a phospholipid monolayer containing polar sterols and various transmembrane proteins, and internally, non-polar sterol esters and triacylglycerols [87]. In cancer, lipid droplets are increased due to the increased lipid accumulation. Lipid droplet biogenesis also occurs in response to cell stress, such as when cancer cells undergo metabolic or oxidative imbalance due to conditions like hypoxia or nutrient starvation [88–91]. In addition to their roles in resistance to stress and as a source for excess lipid storage, lipid droplets can interact with mitochondria to regulate β-oxidation, and have a role in maintenance of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) homeostasis. Androgens increase lipid droplets, which correlate with prostate cancer aggressiveness [92]. The increase in lipid droplets in prostate cancer is additionally related to the upregulation of the PI3K/AKT pathway, often following PTEN loss, which causes the accumulation of intracellular cholesterol esterases [93].

PI3K/AKT signaling also leads to the upregulation of fatty acid synthase (FASN), which is overexpressed in prostate cancer [94,95] FASN is also regulated by AR signaling and correlates with Gleason score and PSA levels [96,97]. Inhibition of FASN with a small molecule inhibitor has been shown to suppress de novo fatty acid synthesis and tumor growth in part by targeting AR signaling [98]. FASN expression can also be increased in response to oxidative stress such as hypoxia. This effect is via activation of the AKT pathway and SREBP-1, which regulates FASN transcription [99]. FASN expression is also regulated by the p300 acetyltransferase, which increases FASN transcription and contributes to lipid accumulation and prostate cancer growth [100]. It remains to be seen whether p300’s effects are mediated through any of the above-mentioned transcription factors.

Lipids can have important roles in the post-translational modification of proteins. Acylation by the covalent addition of palmitate or myristate to proteins can facilitate oncogenic signaling [101]. In prostate cancer, myristoylation of Src kinase has been shown to increase oncogenic signaling and promote tumor progression [101]. In addition, palmitoylation of Src contributes to prostate cancer initiation [102]. Prenylation, the addition of isoprenoids such as farnesyl or geranylgeranyl to proteins, often causes membrane association [103]. Inhibition of geranylgeranylation has been shown to induce autophagy in prostate cancer cells and reduce prostate cancer metastasis in murine models [104,105].

While products from the TCA cycle are used for OXPHOS in normal cells, cancer cells upregulate alternative metabolic pathways to increase NADPH in part for fatty acid production. In this context, the citrate that is produced in the TCA cycle can be shuttled to the cytoplasm to be used for fatty acid synthesis. Cytosolic citrate production can also result from increased glutamine uptake, another characteristic of prostate cancer cells [106,29]. Glutamine can be converted glutamate and then to α-ketoglutarate, which can be used as a carbon source for fatty acid synthesis by conversion to cytosolic citrate via reductive metabolism by the enzymes IDH1 and ACO1 [107]. Alternately, α-ketoglutarate can replenish the carbon intermediates of the TCA cycle. This utilization of cytosolic glutamine for fatty acid synthesis and the TCA cycle is observed in cancer cells [108]. In addition, the oxidation of isocitrate to α-ketoglutarate can produce excess NADPH for fatty acid synthesis [109].

The process of fatty acid synthesis is mediated by a variety of enzymes that are involved in prostate cancer progression. Citrate is converted to acetyl-CoA in the cytoplasm by ATP citrate lyase (ACLY) [110]. ACLY activation can result from PI3K/AKT upregulation, which is common in prostate cancer [111]. Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC1) converts acetyl-CoA to malonyl-CoA [112], which then is processed by fatty acid synthase (FASN), creating the 16-carbon fatty acid palmitate [113]. Enzymes such as stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 (SCD1) or elongation enzymes can function to either insert a double bond in the fatty acid chain to generate a mono-unsaturated fatty acid, or to lengthen the carbon chain, respectively. Desaturation of fatty acids is required for prostate cancer cell growth, an effect that can be blocked by inhibition of SCD1 [114]. These fatty acids are then used in various cell functions including in catabolic pathways as a source of energy, membrane biogenesis, protein post-translational modifications, or regulation of oncogenic pathways. Cytosolic acetyl-CoA can alternately be used for the mevalonate pathway, in which it is converted to mevalonate by HMG-CoA reductase (HMGCR).

Mevalonate is a precursor for synthesis of isoprenoids and cholesterol, which can be used to produce steroids such as androgen [115]. Statins act to reduce cholesterol levels by inhibiting HMGCR, thereby preventing the formation of mevalonate from acetyl-CoA. Statins have been shown to prevent prostate cancer progression, biochemical recurrence, and mortality [116,117]. As such, they are under clinical evaluation for the treatment of prostate cancer. Statins cause an increase in the expression of low-density lipoprotein receptors (LDL-R) [118]. LDL-R is a plasma membrane protein that facilitates the intake of LDL into the cell via endocytosis, providing another source of cholesterol to the cell, and has been shown to regulate cholesterol homeostasis in prostate cancer cells [119]. The LDL-R pathway is regulated by various transcriptional and post-transcriptional factors. For example, expression of LDL-R is activated by SREBP proteins, mainly SREBP-2, through interaction with the SRE, while SREBP-2 activation is inhibited by high levels of intracellular cholesterol [120]. SREBP-2 also regulates transcription of HMGCR; together, this suggests that SREBP-2 contributes to cholesterol accumulation. SREBP-2 also has a role in regulating androgen production, which can be synthesized from cholesterol through this pathway. Interestingly, SREBP-2 can also be regulated by androgens, suggesting a feedback loop for androgen synthesis.

SREBP-2 has been shown to contribute to cholesterol accumulation, which opposes the effect of the nuclear receptor liver X receptors (LXR), another important factor in cholesterol homeostasis [121]. LXRs respond to excess cholesterol by modulating the transcription of various intermediates in the cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis pathways. Two isoforms exist (LXRα and LXRβ), which differ in their tissue localization. Oxysterols, an oxidized derivative of cholesterol, can activate LXRs, which eliminate cholesterol by reducing LDL uptake [122], regulating ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter expression [123], and converting cholesterol to bile acid [123,124]. In cells with increased levels of cholesterol, ABC transporters can mediate the release of cholesterol by the process of reverse cholesterol transport (RCT) which is mediated by LXRs [125]. LXR has been shown to promote a tumor suppressive role in prostate cancer [126,125]. In addition, the synthesis of steroids from cholesterol is regulated by the cytochrome P450 family of enzymes. CYP27A1 encodes a cytochrome P450 oxidase that converts cholesterol into 27HC and other oxysterols. This creates a system in which 27HC inhibits prostate cancer cell growth by depleting cellular stores of cholesterol [127] and possibly through the activation of LXR.

Interestingly, while prostate cancer has classically been characterized by increased fatty acid synthesis and lipid uptake, it is now clear that these tumors ironically also exhibit and require high levels of beta oxidation [128]. While fatty acid synthesis provides lipids for various purposes and pathways in the cell, beta oxidation can provide necessary energy from stored lipids, which can be used for cancer cell growth by providing ATP, as well as acetyl-CoA which can be recycled into the TCA cycle, used as second messenger or possibly rerouted for use in epigenetic regulation. The process of beta oxidation occurs mainly in the inner mitochondrial membrane, where fatty acids can be transported via carnitine transport. Carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 (CPT1) has been demonstrated to be required for prostate cancer cell growth [129–131]. Blockade of beta oxidation at additional steps was also able to impair prostate cancer growth and metastasis in vivo by inhibiting CaMKII activation [132]. Beta oxidation also occurs in peroxisomes, after which oxidized lipids can be transported to the mitochondria or can enter different cell pathways [133]. An increase in beta oxidation in prostate cancer is supported by the upregulation of α-methylacyl-CoA racemase (AMACR), an enzyme involved in catalyzing the peroxisomal and mitochondrial beta oxidation of branched-chain fatty acids, in human prostate cancer [134,135]. D-bifunctional protein (DBP), which is involved in peroxisomal beta oxidation, is also upregulated in prostate cancer [136]. Taken together, prostate cancers exhibit dynamic lipid metabolism, indicating that both the synthesis and breakdown of fats may represent therapeutic vulnerabilities for the treatment of the disease.

Amino Acid Metabolism

While glutamine is not an essential amino acid, it plays an important role during cancer cell starvation as a source of energy, carbon and nitrogen [137–139]. SLC1A5 (ASCT2) is the primary glutamine transporter in cancer [140]. Other transporters such as SLC1A4 (ASCT1) may also play a role in glutamine transport under conditions of stress in the tumor microenvironment [141]. However, it is unclear at this time if this is due to direct or indirect transport. Both SLC1A4 and SLC1A5 are observed to be upregulated in prostate cancer by androgens [142,141]. However, SCL1A4 and SCL1A5 are not direct targets of the androgen receptor [141]. While MYC is a major regulator of glutamine metabolism in many cancer types [139,143,144], MYC appears to regulate glutamine metabolism in prostate cancer in a context-dependent manner that is potentially influenced by the PTEN status of the cell [141]. Interestingly, glutamine uptake in prostate cancer cells is driven by several oncogenic networks such as AR, MYC and mTOR signaling.

Due to the dependence of cancer cells on glutamine, several attempts have been made to exploit this vulnerability. The drug CB-839 (Calithera Biosciences), which targets mitochondrial glutaminase, is currently being tested in early phase clinical trials for the treatment of solid tumors in combination with chemotherapeutic drugs [145]. A recent study demonstrated that the aggressive prostate cancer cell line PC-3 and the metastatic derivative PC-3M are sensitive to CB-839 due to their dependence on glutamine metabolism [106]. While appealing to target the conversion of glutamine to glutamate, this approach has limitations as it does not consider the contributions of glutamine metabolism independent of glutaminolysis. First, glutamine can activate MAPK signaling independently of RAS [146]. Second, it was reported that amino acids, including glutamine, can activate CaMKK2 which in turn activates AMPK [147]. While AMPK was initially described as a tumor suppressor due to its upstream kinase LKB1 [148–150], a context-dependent oncogenic role for AMPK has emerged in recent years [131,151–153]. To account for these additional aspects of glutamine metabolism, the first selective inhibitor of SLC1A5/ASCT2, V-9302, was developed [154]. This inhibitor was tested across a panel of 29 cancer cell models and in vivo, resulting in decreased growth, increased cell death and oxidative stress [154]. However, it should be mentioned that glutamine is not the only amino acid transported by ASCT2 [154]. Hence, the effect of V-9302 might not be due to glutamine uptake alone. Further, even though ASCT2 is the major glutamine transporter [155], additional transporters such as LAT1 and 2, as well as SNAT1–5 can also transport glutamine [154]. LAT1 and 3 are upregulated in prostate cancer and while they are the main transporters for leucine, the transport of glutamine is also possible [142,154]. Thus, inhibition of other amino acid transporters besides ASCT2, such as LAT1, may also decrease tumor growth [142]. An advantage of the transporters is their cell surface localization, making them theoretically accessible for other types of potentially more selective targeting (ex. antibody-mediated delivery).

Another non-essential amino acid that has been targeted for cancer treatment is arginine. Many advanced cancers, including prostate cancer, demonstrate a loss of components of the urea cycle such as argininosuccinate synthease (ASS) [156–159]. ASS is needed for the eventual conversion of arginine from citrulline [160], which means that loss of ASS leads to a cellular dependence on the uptake of extracellular arginine. This vulnerability is targeted by introducing the enzyme arginine deiminase (ADI) conjugated to polyethylene glycol (the latter for decreased immune response and increased serum half-life), resulting in the depletion of circulating arginine from the serum [161]. In ASS-deficient prostate cancer cells such as CWR22Rv1, treatment with ADI-PEG20 alone or in combination with docetaxel led to reduced tumor growth in mouse xenograft models [157]. As expected, cells expressing low levels of ASS (PC-3) are responsive to ADI-PEG20, while those expressing high levels of ASS (LNCaP) are resistant to ADI-PEG20 [157]. While this approach shows promising results [157], it was reported that the deprivation of arginine can lead to resistance due to the compensatory induction of ASS expression [156]. Another approach to starve cancer of arginine is the use of recombinant arginase, which converts arginine into ornithine [162]. While this is dependent on the levels of ornithine carbamoyl transferase (OCT) expression, the study concluded that several prostate cancer cell lines with low levels of OCT are responsive to arginase treatment [162]. However, this approach has to be carefully considered due to the importance of the polyamine synthesis pathway which uses ornithine as a substrate. Several cancers have showed increased proliferation when the polyamine synthesis pathway was upregulated [163]. In prostate cancer, the enzyme ornithine decarboxylase (ODC), which converts ornithine to putrescine, is a direct target of AR [164]. Further, when ODC is overexpressed, regular prostate epithelial cells can be transformed into prostate cancer cell [165]. Inhibition of the uptake of polyamines by N1-spermine-L-lysine amide or ODC itself by α-difluoromethylornithine is sufficient to inhibit the growth of prostate cancer in culture and in vivo [166]. However, as noted below in the Section “Biofluids and Tissue Metabolism Biomarkers”, the role of the polyamines in prostate cancer may not mirror that observed for other cancer types. For example, the levels of polyamines, and especially spermine, are often decreased in primary prostate cancer relative to benign prostate [167–169]. Hence, whether the polyamines, or perhaps specific polyamines, have unique roles in prostate cancer and whether these roles vary further in different disease stages, remains poorly understood.

One-carbon metabolism connects two important pathways: the folate and methionine cycles which can then feed into the transsulfuration and polyamine synthesis pathways. As a result, one carbon metabolism regulates several cellular processes such as epigenetics via methylation (methionine cycle), DNA synthesis and repair (folate cycle) and protection against reactive oxygen species via glutathione (transsulfuration pathway) [170]. This intricate network is fueled by the amino acids serine and glycine [171]. Several key enzymes in these pathways are regulated by the androgen receptor [171]. For example, the conversion of glycine to N-methylglycine (sarcosine) is facilitated by the glycine-N-methyl transferase (GNMT) and has been shown to be important for cell invasion [172]. Knockdown of GNMT resulted in lower amounts of sarcosine and decrease in invasion using DU-145 cells [172]. In contrast, the knockdown of the enzyme sarcosine dehydrogenase (SARDH), responsible for the conversion of sarcosine to glycine, resulted in high levels of sarcosine and elevated invasion [173]. GNMT and SARDH are both regulated by AR and the TMPRSS2-ERG fusion [172,174].

Another important aspect of the one-carbon cycle is its role as a source for methyl groups to perform epigenetic modifications. Methylation of histones depends on S-adenosyl-methionine (SAM), a product of the methionine cycle [170]. It was shown that DNA is often hypermethylated in prostate cancer, regulating genes involved in cell cycle, DNA repair and apoptosis [175–184]. Thus, the main DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) is upregulated and activated in prostate cancer [185,186]. Consequently, tumor formation can be altered, using 5-azacitidine, an inhibitor of DNMT1 [187]. One-carbon metabolism is influenced by AR and fuels prostate epigenetic reprogramming by providing the substrate (SAM) to methyltransferases that are also upregulated by AR [170]. This is highly significant since the epigenetic reprogramming has been shown to lead to drug resistance in prostate cancer. Patients in phase I and II clinical trials demonstrated increased chemosensitivity to docetaxel in combination with 5-azacitidine [188]. In addition to SAM’s important role in epigenetics as a substrate for methyltransferases, it can also be diverted into the polyamine synthesis pathway [170]. Given the importance of the polyamines in the prostate and its association with cancer progression [163,189], the inhibition of methyltransferases may counterproductively lead to an increase in polyamine synthesis. To that end, it was reported that elevated levels of polyamines could lead to prostate cancer progression [190,191] as the reduction of polyamines in CRPC patients led to prolonged survival [192]. Interestingly, when SAM is utilized by the methyltransferases it creates S-adenosyl-homocysteine (SAH), which moves along the methionine cycle to intersect with the folate cycle to create methionine and regenerate SAM [170]. Along the methionine cycle SAM is converted to SAH and further to homocysteine by the enzyme S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase [171]. Homocysteine can then feed into the transsulfuration pathway, resulting in the production of glutathione and therefore altering the cellular response to ROS [170]. Taken together the one-carbon cycle represents a complex network of several pathways, of which we are only beginning to understand if, how and when to target.

Hexosamine Biosynthetic Pathway

The Hexosamine Biosynthetic Pathway (HBP) branches from the traditional glycolytic pathway to synthesize UDP-GlcNAc, the essential substrate for N- and O-linked protein glycosylation and glycosaminoglycan, proteoglycan, and glycolipid production. While the HBP shunts only a small percentage of fructose 6-phosphate away from glycolysis, it is viewed as a readout of total cellular energy levels because it incorporates metabolites from several key metabolic pathways, including nucleotide (uracil), amino acid (glutamine), fatty acid (acetyl-CoA), and glucose (F6P) metabolism [193]. Additionally, the UDP in UDP-GlcNAc is an energetic compound that can serve as a non-ATP readout of cellular energy availability [193].

In prostate cancer, the HBP is upregulated in hormone-sensitive, localized tumor samples, as the mRNA and protein levels of the first and rate-limiting enzyme in the HBP, glutamine fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase (GFAT/GFPT1), and the final enzyme in the HBP, UDP-N-Acetylglucosamine Pyrophosphorylase 1 (UAP1) are elevated in cancerous prostate tissues compared to matched benign samples. GFAT and UAP1 levels are also increased in response to androgens in LNCaP and VCaP cells [194,195]. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)-based evaluation of the levels of sugar nucleotides in cells revealed UDP-GlcNAc levels are high in early-stage, AR-positive cell lines (LNCaP and VCaP), but low in nontransformed human prostate cell lines (RWPE-1 and PNT2) as well as AR-negative PC-3 cells. In addition, AR-positive cell lines express ~50% more enzymes involved in the HBP compared to AR-negative cell lines. This indicates that AR mediates the upregulation of HBP enzymes, and, therefore, the flux of metabolites through the HBP in early, localized prostate cancer.

N-linked glycosylation utilizes UDP-GlcNAc to add complex sugar conjugates to proteins in the ER and Golgi bound for the outer membrane which can, amongst other effects, influence the localization and stability of those proteins [196]. The decrease in the expression of AR target genes KLK3 and CAMKK2 (cytosolic proteins that are not N-glycosylated) in the presence of the N-linked glycosylation inhibitor tunicamycin suggests that AR activity may be dependent on positive crosstalk with a membrane bound protein that relies on N-linked glycosylation for activity and/or stability. The main candidates for this are receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), specifically insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF-1R). N-linked glycosylation increases RTK membrane retention time resulting in longer RTK signaling. In LNCaPs and VCaPs, glycosylation of IGF-1R increased AR-mediated transcription of IGF-1R indicating there is a positive feedback between the two that requires glycosylation-mediated IGF-1R membrane retention and subsequent IGF-1R-mediated AR activation.

O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine transferase (OGT), the enzyme that utilizes UDP-GlcNAc to mediate O-GlycNAcylation (O-GlcNAc) of protein substrates, is also upregulated in clinical samples of localized prostate cancer and is associated with poor prognosis [195,197,198]. O-GlcNAc modification of Ser/Thr residues on proteins can act similarly to phosphorylation to change the activity of a given target protein. Inhibition of OGT either pharmacologically or molecularly led to a decrease in the viability of LNCaP, VCaP and PC-3 cells. It also led to a decrease in tumor size in mouse xenografts of prostate cancer and other cancer types. This could be due in large part to the destabilization of c-MYC caused when OGT is lost. When glycosylated by OGT, c-MYC remains stable, but when c-MYC remains unglycosylated, it becomes vulnerable to ubiquitin mediated proteasomal degradation.

Paradoxically, in CRPC, expression of the HBP enzyme glucosamine-phosphate N-acetyltransferase 1 (GNPNAT1) is significantly decreased compared to localized prostate cancer [199]. Loss of GNPNAT1 expression increased the aggressiveness and proliferation of CRPC. This was mediated by the expression of several oncogenic cell cycle genes through activation of the PI3K-AKT pathway in cells expressing full-length androgen receptor (AR) or by specific protein 1 (SP1)-regulated expression of carbohydrate response element-binding protein (ChREBP) in cells containing the AR-V7 variant. Accordingly, addition of UDP-GlcNAc to CRPC cells decreased proliferation in cell culture and tumor growth in vivo. UDP-GlcNAc treatments also sensitized CRPC cells to enzalutamide. Taken together, activation of the HBP or addition of its end product UDP-GlcNAc, particularly in conjunction with a standard of care drug like enzalutamide, could have clinical efficacy in the treatment of CRPC.

Metabolic Scavenging

Autophagy is a cellular recycling process that can provide metabolites under conditions of cellular stress such as starvation. It can also help mitigate ROS by clearing out dysfunctional organelles (ex. mitochondria), and clear the cell of protein aggregates and damaged proteins that interfere with normal cell operations. Initially, autophagy was categorized as a tumor suppressive process due to its ability to shut down proliferation and induce cell death when hyper-activated. However, recent studies indicate autophagy is contextual, exhibiting both pro-cancer and anti-cancer functions [200,201]. In prostate cancer, autophagy has been shown to provide advanced prostate cancers protection against starvation and hypoxia while promoting resistance to cancer therapies [202]. Moving forward, the intricate relationship between autophagy core components, its upstream regulators, altered AR signaling, and conditions in the tumor microenvironment must be defined to determine if, how, and when modulators of autophagy could be used to treat prostate cancer.

A study of melanoma showed that knockout of the core autophagy gene Atg7 led to a decrease in tumor growth due to DNA damage and activation of senescence [203]. Another study of melanoma showed monoallelic loss of Atg5 led to tumor metastasis while, in contrast, total loss of Atg5 led to increased sensitivity to BRAF inhibitors and decreased tumor burden [204]. These findings suggest that there are dose-dependent effects of autophagy in cancer. This seems to be the case in prostate cancer as well. Using genetic mouse models, deletion of Atg7 specifically in prostate epithelia was sufficient to impair cancer progression in Pb-Cre, Ptenf/f in both intact and castrate conditions [205]. Interestingly, co-targeting of HK2 and ULK1-dependent autophagy suppressed the growth of PTEN- and TP53- deficient CRPC [185], indicating that autophagy inhibitors may have improved efficacy under induced conditions of metabolic stress.

It is becoming increasingly clear that autophagy plays a critical role in resistance to treatments of advanced prostate cancers [206,207]. To that end, enzalutamide resistance in CRPC cells can be overcome by inhibition of autophagy [208–210]. Docetaxel induces autophagy through Beclin1-Vps34-Atg14 complex formation in CRPC cells without effecting mTOR or p-mTOR expression [211]. Inhibition of autophagy boosted sensitivity to the chemotherapy in CRPC cells, and interestingly, it has been found that activation of STAT3 by IL-6 could inhibit autophagy and improve chemotherapeutic efficacy [211–213]. Additionally, autophagy provided protection against the anti-cancer drug diindolylmethane (DIM) in LNCaP and C4–2B cell lines and PC-3 xenograft mouse models [214,215]. Treatment of DIM in combination with the ULK1 inhibitor MRT 67307, chloroquine (CQ), or siRNAs against the oncogene AEG-1 or AMPK significantly reduced cell proliferation in culture and tumor growth in vivo. Further, when PC-3 cells were treated with the cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitor celecoxib, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) mediated the activation of autophagy to protect cells from celecoxib-induced apoptosis [216]. Finally, curcumin can activate autophagy and apoptosis in CRPC. Curcumin treatment in conjunction with inhibitors of autophagy increased apoptotic cell death and mitigated the protective effect of autophagy [217]. To date, however, significant anti-cancer efficacy of autophagy-targeted therapies has not been observed in prostate cancer patients. However, this could be due to the lack of potent and selective inhibitors of autophagy, a major limitation of the field.

Recently, loss of the transcription factor repressor element-1 silencing transcription factor (REST) combined with induction of autophagy was found to promote the neuroendocrine differentiation (NED) of prostate cancer. Monoamine oxidase A (MAOA), a mitochondrial enzyme, was identified to be downregulated by REST [218]. Downregulation of MAOA resulted in decreased autophagic flux (specifically mitophagy). Cells with downregulated MAOA were also identified to have fewer NED characteristics. Clinically, MAOA expression tracked with prostate cancer relapse in patient samples. Thus, MAOA expression could induce neuroendocrine transdifferentiation in part through induction of autophagy/mitophagy. Like MAOA, tumor necrosis factor α-inducible protein 8 (TNFAIP8) has been shown to be expressed highly in AR-negative PC-3 cells and expression is associated with prostate cancer survival [219]. Overexpression of TNFAIP8 in PC-3 cells tracked with autophagic flux and biomarkers of NED. Another new possible regulator of autophagy is dCTP pyrophosphatase 1 (DCTPP1) [220]. DCTPP1 typically is involved in hydrolyzing dCTP to dCMP. High DCTPP1 levels track with prostate cancer progression and Gleason score as well as the progression of other cancer types. A bioinformatics study has linked DCTPP1 tumor promoting actions to autophagy, but further research is still needed to determine how DCTPP1 is mechanistically linked to autophagy.

While still controversial, most data support a tumor suppressive role of autophagy in the early stages of the disease and a tumor-supportive role of autophagy in the late stages [202]. Current evidence suggests that inhibiting autophagy, or its upstream regulators, in combination with antiandrogens, taxanes, or other targeted therapies may have clinical efficacy in the advanced stages of prostate cancer. Recent interesting findings point toward a link between autophagy and NED. How autophagy can induce this differentiation or if autophagy is just a bystander during NED is still unclear. As new ways to accurately measure autophagic flux in vivo become available, understanding what type of autophagy, when autophagy is activated, and where autophagy is activated will provide the needed insights into how autophagy is contributing to disease progression and therapy resistance. Further, discovery of new regulators of autophagy and efficacious in vivo inhibitors will undoubtedly be needed to push this therapeutic approach in the clinic.

During a process known as macropinocytosis, cells engulf nearby extracellular substances and transport them to lysosomes for degradation to yield smaller metabolites that provide cells with additional nutrients. In the context of cancer, macropinocytosis can provide starved and stressed cells with additional nutrients much like autophagy, even sharing some of the same components and regulatory pathways [221]. However, unlike autophagy, macropinocytosis can scavenge extracellular nutrients, easing the burden on cells to recycle their own components which will eventually become depleted. Given that cancer cells can utilize macropinocytosis to survive in nutrient starved environments, targeting its upstream regulators and core machinery could have therapeutic value.

Macropinocytosis requires PI3K-mediated production of PIP3 for membrane enclosure and RAC1 activation to prompt cytoskeletal remodeling and membrane ruffling necessary for engulfment of extracellular materials [222]. The PI3K inhibitor PTEN is the most commonly deleted tumor suppressor in prostate cancer. Concurrently, the RAC1 activator AMPK is often highly activated in prostate cancer due to the increased expression of the AR target gene and AMPK activator CaMKK2 [223]. Taken together, macropinocytosis can be highly activated in prostate cancer. Recently, it was found that macropinocytosis in PTEN-deficient prostate cancer differs from RAS-driven cancers as it did not account for all of the albumin uptake into the cell [222]. However, it was shown that necrotic debris was exclusively taken into the cell via macropinocytotic engulfment. This discovery was elegantly accomplished using fluorescently labeled murine hematopoietic cell “corpses” introduced into the media of prostate cancer cells. Necrotic debris is often available in the tumor microenvironment due to starvation-induced death initiated by the tumor cell itself or by cancer therapies that kill some but not all tumor cells. Containing organelles, proteins and other nutrients, engulfed necrotic tissue is broken down into metabolites to sustain growth, proliferation, and survival. Proteins from the necrotic debris provide amino acids for biomass. Besides increased biomass, the replenished amino acid pool activates mTOR signaling. Further, lipids are also derived from the necrotic tissue and supplement lipid biosynthesis and subsequent lipid metabolism that is critical to many prostate cancers. Hence, micropinocytosis is an emerging biological process in cancer that may warrant drug development efforts. To that end, the requirement for lysosomal activity in both autophagy and micropinocytosis may account for some of the efficacy of the reported autophagy inhibitors that function via disrupting lysosomal functions.

Regulation of Metabolic Reprogramming

Signal Transduction

The regulation of cancer metabolism by signal transduction pathways has garnered considerable attention over the past two decades. It is clear that aberrant signaling, from both intracellular and extracellular stimuli, converge to alter a cancer cell’s central metabolism to support the high demands for energy production and building blocks. In the context of prostate cancer, AR activation has been tightly coupled with global metabolic alterations. Also, MYC amplification, PTEN loss and aberrant activation PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling, all common events in advanced prostate cancer, have profound effects on metabolic adaptation. Here, we summarized the association of several key signaling pathway regulators with metabolic reprogramming in prostate cancer.

As the major driver of prostate cancer, AR’s influence on diverse metabolic pathways has significant implications for prostate cancer progression. Transcriptional upregulation of enzymatic genes is one of the important ways that AR works in metabolic rewiring. A common mechanism is AR directly binding to the promoters of these genes and increasing their transcription. The expression of these critical enzymes promotes a metabolic shift that facilitates cell growth, survival and migration [224,153,225,226]. A detailed description of known, direct AR metabolic target genes has been previously described [225]. Additionally, some important metabolic regulators are downstream targets of AR. For example, AR actives a CaMKK2-AMPK-mediated cascade. CAMKK2 is the direct target of AR and is overexpressed and over-activated in prostate cancer [151–153,227]. CaMKK2, the predominant upstream kinase of AMPK in the prostate, helps cells to adapt to various energetic stresses. AMPK-mediated metabolic changes have been correlated with increasing intracellular ATP levels, glycolysis, glucose uptake and PGC-1α-mediated mitochondrial biogenesis [131,227,153,29]. HIF1α also coordinates with AR to mediate metabolic adaptation to hypoxia and help cells maintain redox balance and cell survival under hypoxia. In a low androgen environment, HIF1 α directly upregulated AR expression in the presence of hypoxia [228]. Meanwhile, AR can stabilize and activate HIF1α through an autocrine loop of PI3K/AKT in a hypoxia-independent manner [229]. This crosstalk provides rationale for the joint inhibition of AR and HIF-1α to treat prostate cancer by blocking metabolic adaption to varied androgen or oxygen levels. Of note, AR splice variants can also regulate prostate cancer cell metabolism. For example, AR-V7 can promote cell growth, migration, and glycolysis [173]. Like AR, in CRPC cells, AR-V7 can drive de novo lipogenesis [71]. However, AR-V7 did exhibit some unique metabolic regulatory behavior. A metabolic profile showed that in AR-V7-stimulated cells, there were some striking differences in the levels of TCA cycle intermediates [173]. Notably, AR-V7 promoted higher levels of citrate oxidation, similar to what was observed in CRPC patient samples [173]. Further, AR-V7 increased glutaminolysis and reductive carboxylation.

MYC is another common oncogene that drives prostate cancer tumorigenesis. Amplification and mutations of MYC are frequently seen in advanced prostate cancer and associated with poor prognosis in a subset of cases [230]. Similar to AR, MYC contributes to metabolic reprogramming partially through the activation and expression of metabolic enzymes. Mitochondrial glutaminase, GLS1, has been identified as a MYC downstream effector for glytaminolysis in PC-3 cells via miR-23a/b [143]. Additionally, glutamine uptake was regulated by MYC in a PTEN-dependent manner [141]. Many MYC-mediated effects are exerted through complex interactions. MYC-E2F1 had a greater regulation of nucleotide metabolism while MYC-HIF-1α was more involved in glucose metabolism [231]. Moreover, MYC may also play a role in lipid metabolism. Oncogene-mediated metabolic signatures in prostate cancer revealed that dysregulated lipid metabolism was induced by MYC overexpression [232].

PTEN loss and subsequent hyperactivation of PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling are also common events in advanced prostate cancer. As a master regulator of metabolism, the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway controls nutrient uptake and utilization as well as metabolic scavenging. PI3K/AKT activation has been strongly linked to aerobic glycolytic metabolism [232]. Further, mTORC1 promotes glycolysis by increasing HK2 translation and upregulating the expression of HIF-1α [233,234]. The mTORC2 complex further augmented glycolysis through AKT-dependent HK2 activation [233]. In addition, activation of AKT via PTEN-deficiency has been indicated to increase glucose metabolism by increasing HK2 phosphorylation and expression which in turn increased intracellular ROS-mediated cell growth [235]. Moreover, AKT/mTORC1 has been suggested to influence fatty acid synthesis through the activation of SREBP and upregulation of FASN [95,236]. Inhibition of AKT in PTEN-deficient cells modulated the activation of ACLY. This repression limited the conversion of citrate to acetyl-CoA which ultimately reduced histone acetylation and epigenetic regulation [237,234]. PTEN loss also led to cholesterol ester accumulation which has been linked with more aggressive diseases [93,238]. Therapeutically, Naguib et al. suggested that inhibition of mitochondrial complex I is an effective strategy to decrease PTEN loss-induced cell growth [239]. This was attributed to the fact that PTEN-null cells are more dependent on consuming ATP through mitochondrial complex V. Additionally, mTOR signaling modulates amino acid metabolism in prostate cancer through its regulation of glutamine uptake, glutamine utilization, and polyamine biosynthesis [141,240,241]. Importantly, PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling can function in part as a nutrient sensor by responding to changes in cellular energy status. For instance, leucine deprivation inhibited proliferation and induced apoptosis in CRPC via blocking mTORC1 signaling [242].

Of note, signaling pathways rarely work in isolation. Instead, they are greatly influenced by one another. AR has been demonstrated to regulate MYC expression in a context-dependent manner [141]. Blocking either AR or the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway can mutually stimulate the other pathway to support cancer cell proliferation, particularly in the context of CRPC [243–245]. Meanwhile, AR activation induced mTOR nuclear localization and reprogramed its genomic binding. In this scenario, mTOR acted as a transcriptional integrator to facilitate androgen-dependent metabolic rewiring [246]. In addition, AMPK activation is essential for PTEN loss-increased macropinocytosis [222]. Also, mTOR signaling promoted prostate cancer stem cell survival, an effect that was modulated by HIF-1α [247]. Considering the abundance of multiple feedback mechanisms, future therapeutic regimens may benefit from combinatorial treatment strategies, especially for overcoming drug resistance [244,245,248].

Non-coding RNAs

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small, endogenous non-coding RNAs of 18~25 nucleotides in length, which act as gene regulators. Different from transcription factors, miRNAs regulate gene expression by directly binding to the 3’-untranslated region (3’UTR) of mRNAs and inducing mRNA degradation and/or inhibiting translation. Therefore, miRNAs have been associated with a number of biological processes including proliferation, apoptosis and metabolism. Emerging evidence has revealed that the altered metabolism in cancers including prostate cancer is strongly mediated by miRNAs. They can either directly target the transporters, kinases and enzymes in established metabolic pathways or indirectly manipulate important signaling pathways that regulate cancer metabolic shifts. Here, we focus on the direct regulation and will briefly summarize miRNAs and their related metabolic targets in prostate cancer (Table 1).

Table 1:

miRNAs Regulating Prostate Cancer Metabolism.

| miRNAs | Regulation | Target Genes | Direct | miRNA Function in Metabolism | Tissues/Cell Lines | Reference (PMID) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-132 | down | GLUT1 | Yes | inhibit glucose uptake, lactate secretion and glycolysis | PC-3, DU-145, LNCaP, prostate cancer tissue | 27398313 |

|

PKM2 HK2 |

unknown | |||||

| miR-181b | down | HK2 | Yes | inhibit glycolysis | PC-3 | 28184935 |

| miR-143 | down | HK2 | Yes | glucose metabolism | GSE21032 dataset, PC-3 | 26269764 |

| miR-421 | down | PFKFB2 | Yes | inhibit glycolysis | LNCaP, 22Rv1, PC-3, LNCaP, prostate cancer tissue | 26269764 |

| miR-205 | down |

HK2 GLUT1 |

unknown | promote metabolic shift from glycolysis to OXPHOS, Docetaxel resistance | docetaxel-resistant PC-3 and DU-145 | 27542265 |

| MDH2 | Yes | inhibit MDH2 expression | different stages of prostate cancer tissue | 29563510 | ||

|

miR185 miR-342 |

down |

SREBP1 SREBP2 |

Yes | inhibit the expression of FASN and HMGCT, inhibit lipogenesis and cholesterogenesis | LNCaP, C4–2B | 23951060 |

| miR23a/b | down | GLS1 | yes | increase glutamine catabolism | PC-3 | 19219026 |

| miR22b-3p | up | PRODH | inhibit proline catabolism | PC-3 | 22615405 | |

| miR-22 | down | ACLY | yes | inhibit de novo lipid synthesis | PC-3 | 27317765 |

| down | MDH2 | Yes | inhibit MDH2 expression | primary prostate cancer, CRPC, PC-3 | 29563510 | |

| miR-17/92 cluster | up | PPARA | unknown | increase lipogenesis | LNCaP | 23059473 |

|

miR-1 miR-206 |

down |

G6PD TKT PGD GPD2 |

unknown | inhibit glycolysis | DU-145 | 23921124 |

| miR-29c | down | SLC2A3 | Yes | inhibit glucose metabolism | prostate cancer tissue | 29715514 |

In contrast to the largely global increase of miRNAs in prostate cancer [249], miRNAs directly regulating prostate cancer glucose metabolism are mostly downregulated. Such inhibition facilitates the stability and expression of metabolism-related mRNAs. Decreased expression of miR-132, observed in prostate cancer, can promote a metabolic shift towards glycolysis by increasing the expressions of GLUT1, HK2 and PKM2 [250]. Targeting miR-132 using an inhibitor was sufficient to stimulate glucose uptake, increase lactate secretion and boost cell proliferation. Similarly, miR-181b, 142, 421, 205 and 143 are also associated with the regulation of glycolysis (Table 1).

In addition, miRNAs also regulate the TCA cycle and OXPHOS. Malate dehydrogenase 2 (MDH2), a TCA cycle enzyme, has been associated with miR-22 and miR-205 [21]. Through comparing RNA-seq and proteomics data from benign, untreated primary prostate cancer and CRPC samples, a recent study showed that the protein expression of MDH2, which persistently increased during prostate cancer progression, was not correlated with its mRNA level. Strikingly, miR-22 and miR-205 were found to directly bind to the mRNA of MDH2 and suppress its protein translation. miR-205 also contributed to docetaxel resistance in prostate cancer by promoting a metabolic shift from glycolysis to OXPHOS. OXPHOS engagement may be a hallmark of docetaxel resistance in PC-3 cells. Compared to parental PC-3 cells, in docetaxel-resistant derivative PC-3 cells, OXPHOS-related genes are upregulated while glycolytic genes are downregulated. Accordingly, restoration of miR-205 led to the increase of HK2 and GLUT1 mRNA and made cells more sensitive to the docetaxel. However, it remains unknown how miR-205 upregulates HK2 and GLUT1.

Further, miRNAs can target the PPP to provide building blocks for nucleotide biosynthesis as well as NADPH for anabolic metabolism and ROS homeostasis. Singh et al. demonstrated that miR-1 and its identical paralog miR-206 are associated with prostate cancer metabolic alterations through targeting three key PPP genes (G6PD, PGD, and TKT) and one carbohydrate/lipid metabolism regulation gene (glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, GPD2) [251]. Nuclear factor erythroid-2-related factor 2 (NRF2) was reported to promote tumor growth by attenuating miR-1 and miR-206 expression, activating the PPP pathway, which in turn accelerated cell proliferation.

SREBP-1, −2, ACLY and PPARA have been identified as the direct targets of miRNAs [252]. For instance, ACLY was identified as a direct target of miR-22 [253]. MiR-22 bound to the 3’UTR (seed sequence GGCAGCU) of ACLY to decrease it subsequent de novo lipid synthesis. As a result, miR-22 treatment was able to inhibit PC-3 cell growth and metastasis in cell and xenograft models. Moreover, SREBP-1 and −2, master transcription factors for lipogenesis and cholesterogenesis, are controlled by miR-185 and miR-342 in prostate cancer [254]. Through repressing SREBP-1 and −2, these two miRNAs block the expression of FASN and HMGCR, two genes important for fatty acid and cholesterol synthesis. Compared to the non-cancerous prostate epithelial cell line RWPE-1, LNCaP and C4–2B cells had lower expression of both miR-185 and 342. Restoration of miR-185 and 342 not only decreased the amounts of fatty acid and cholesterol, but inhibited tumorigenesis, cell growth, migration and invasion in the prostate cancer cells.

MiR-23a and miR-23b are two miRNAs identified to regulate glutamine catabolism in prostate cancer. Gao et al. reported that miR-23a and miR-23b directly targeted mitochondrial glutaminase to influence cell survival [143]. Mechanistically, MYC transcriptionally impeded the expression of miR-23a and miR-23b, which increased the expression of glutaminase. This promoted the conversion of glutamine to glutamate. Glutamate could then serve as a substrate for ATP production or glutathione synthesis, both of which could impact the cell proliferation. However, MYC was also reported to upregulate miR-23b-3p and consequently proline dehydrogenase expression [255]. Since proline dehydrogenase can induce apoptosis, the decreased level of proline dehydrogenase could protect cells against oxidative stress and increase cell survival. Clearly, additional work needs to be done to fully understand MYC’s regulation of this set of miRNAs.

Influence of the Tumor Microenvironment

While cancer cell intrinsic mutations and signaling aberrations undoubtedly drive metabolic reprogramming in prostate cancer, it is now appreciated that the cancer microenvironment, including fibroblasts, adipocytes, immune cells as well as endothelial cells, can greatly influence metabolism and disease progression [256]. Cancer initiation, progression and metastasis all require adaptation to the harsh host microenvironments that can include a lack of nutrients, high oxidative pressure and hypoxia. Meanwhile, by interaction or signal secretion, cancer cells are able to remodel the extracellular matrix (ECM), repurpose the surrounding non-malignant cells and eventually leverage their neighbors to support their rapid proliferation. Therefore, the crosstalk between cancer cells and surrounding cells helps determines the fate of cancer and thus may provide an attractive target for cancer therapy. Here, we will focus on the metabolic interaction between prostate cancer and its microenvironment.