Abstract

Background:

Bariatric surgery is underutilized in the United States.

Objective:

To examine temporal changes in patient characteristics and insurer type mix among adult bariatric surgery patients in Southeastern Pennsylvania and to investigate the associations between payer type, insurance plan type, cost-sharing arrangements (among traditional Medicare beneficiaries), and bariatric surgery utilization.

Setting:

Pennsylvania Health Care Cost Containment Council’s databases in Southeastern Pennsylvania during 2014-2018.

Methods:

All adult patients who underwent the most common types of bariatric surgery and a 1:1 matched sample of surgery patients and those who were eligible for surgery but did not undergo surgery were identified. Contingency tables, Pearson Chi-Square tests, and logistic regression were used for statistical analysis.

Results:

Over the five years, there was an increase in the proportion of Black individuals (37.1% in 2014 vs 43.0% in 2018), Hispanics (5.4% vs 8.0%), and Medicaid beneficiaries (19.2% in 2014 vs 28.5% in 2018) who underwent surgery. The odds of undergoing bariatric surgery based on payer type only between Medicare beneficiaries were statistically different (22% smaller odds) compared to privately insured individuals. There were significantly different odds of undergoing surgery based on insurance plan type within Medicare and private insurance payer categories. Individuals with traditional Medicare plans with no supplementary insurance and those with dual eligibility had smaller odds of undergoing surgery (42% and 32%, respectively) compared to those with private secondary insurance.

Conclusions:

Insurance plan design may be as important in determining the utilization of bariatric surgery as the general payer type after controlling for confounding socio-demographic factors.

Keywords: obesity, bariatric surgery, health insurance, access to health care

Introduction

Bariatric surgery is the most effective treatment for clinically severe obesity, providing sizable and long-lasting weight losses as well as significant improvements in obesity-related comorbidities [1,2]. Nevertheless, only a small percentage of individuals meeting the eligibility criteria for bariatric surgery undergo surgery each year. For example, the estimated utilization of bariatric surgery in the eligible population was 503 per 100,000 (or 0.5%) in 2016 [3].

Nationwide data show that approximately two-thirds of bariatric surgery patients in 2016 were white [3]. Eight of 10 were women and patients were an average age of 44 years [3]. Six of 10 patients who underwent bariatric surgery had private insurance [3]. The racial and socioeconomic disparities in access to bariatric surgery are becoming increasingly recognized [4-7]. For example, a study based on the 2005-2006 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and the 2006 Nationwide Inpatient Sample found significant disparities in the receipt of bariatric surgery based on race, income, education level, and insurance type [4].

Fortunately, the gap in the utilization rates among publicly and privately insured patients has been narrowing in the past decade. Particularly, the nationwide share of Medicare and Medicaid in the payer mix for bariatric surgery was 8.3% and 5.9% in 2005; those figures increased to 14.2% and 17.2% in 2016, respectively [3]. It is unknown, however, whether in communities with a larger percentage of non-white citizens, such as in Southeastern Pennsylvania [8], followed the nationwide trends.

Our research team reported that specific aspects of insurance plan type (e.g. preferred provider organization [PPO], fee-for-service, health maintenance organization [HMO]) have been associated with the utilization of bariatric surgery [9]. However, statistically different odds of undergoing bariatric surgery based on payer type were not observed [9]. These findings were novel and in contrast with previous investigations [4,5,10]. Sociodemographic variables, including age, sex, race, and area of residence (zip code) and which were controlled for in the analytic plan, may account for the difference between studies.

Other studies have reaffirmed the association between insurance plan type and utilization of bariatric surgery [11,12]. Utilization of surgery was reported to be higher in the more generous commercial insurance plans that generally have lower out-of-pocket payments, such as PPO plans, and lowest in high-deductible health plans [11,12]. This is not surprising, considering the high cost of bariatric surgery ($8,678–$14,082) [3]. Similarly, individuals with Medicare Advantage PPO plans (Medicare plans administered by private insurers) had greater odds of undergoing bariatric surgery compared with Medicare Advantage HMO plan beneficiaries [9]. However, it is unknown whether dual-eligible beneficiaries (eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid) who generally have no or limited cost-sharing have better access to bariatric surgery compared to those enrolled in traditional Medicare with no supplemental insurance (e.g. without Medigap plans that pay for the costs not covered by Medicare).

The current study was undertaken to investigate the temporal changes in the patient characteristics and insurer type mix among bariatric surgery patients in Southeastern Pennsylvania. The study also examined the associations between payer type, insurance plan type, cost-sharing arrangements (among traditional Medicare beneficiaries), and utilization of bariatric surgery; a better understanding of these issues could help policymakers in addressing insurance-related barriers to accessing bariatric surgery.

The study had the following a priori hypotheses. First, we predicted considerable variation by year in the payer mix for bariatric surgery. The largest increase in bariatric surgery utilization was expected among Medicaid and Medicare Advantage beneficiaries. Second, individuals with PPO plans in Medicare Advantage and PPO, as well as fee-for-service plans within privately insured categories, were anticipated to have greater odds of undergoing bariatric surgery compared to those with HMO plans in the corresponding insurer categories. This would confirm previously reported findings from our team on the role of insurance plan type in determining access to bariatric surgery [9]. Third, individuals with traditional Medicare coverage but without supplemental insurance coverage were expected to have smaller odds of undergoing bariatric surgery compared to those covered by traditional Medicare and with secondary private supplemental insurance or those with dual eligibility (qualifying for both Medicare and Medicaid).

Methods

Data Source and Study Population

The study used Pennsylvania Health Care Cost Containment Council’s inpatient discharge and ambulatory/outpatient procedure databases for the years 2014-2018 [13]. These data sources contain de-identified clinical and claims data from all hospitals (excluding Veterans Administration Hospitals) and outpatient and freestanding ambulatory surgery centers in the Philadelphia, Bucks, Montgomery, Chester, and Delaware counties in Southeastern Pennsylvania. The combined population of these counties in 2018 was approximately 4.1 million; 65% of individuals were white, 22% Black, and 13% were other races [8]. The American Community Survey 5-year data from the U.S. Census Bureau (2018) were used to estimate median household income based on the patient's area of residence at the ZIP code level.

Two separate study populations were examined. First, to investigate the temporal changes in patient demographics and payer mix, all adult patients (captured in the datasets) who underwent the most common types of bariatric surgery (sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass) at an inpatient setting during 2014-2018 and had a diagnosis code for severe obesity were identified. Patients with a diagnosis code for noninfective enteritis and colitis and abdominal neoplasms were excluded (Appendix 1, supplementary materials).

Second, to examine the associations between payer type, insurance plan type, cost-sharing arrangements for traditional Medicare beneficiaries, and utilization of surgery, a 1:1 matched sample of bariatric surgery patients and those who were eligible for, but did not undergo surgery (based on a diagnosis of severe obesity, absence of diagnosed common relative contraindications) and with known public or private primary insurance type was identified and served as a comparison group. The sample of comparison patients included adults from the 2014-2018 ambulatory/outpatient procedure databases who met the following criteria: 1) had a diagnosis code for morbid (severe) obesity; 2) did not have a record of any bariatric procedure during 2014-2018; 3) and did not have a diagnosis code for heart failure, chronic ischemic heart disease, malignant neoplasms, portal hypertension, Crohn's disease, mental and behavioral disorders due to psychoactive substance use, or Intellectual disabilities since those conditions are common relative contraindications to surgery which could decrease the likelihood of undergoing bariatric surgery [14].

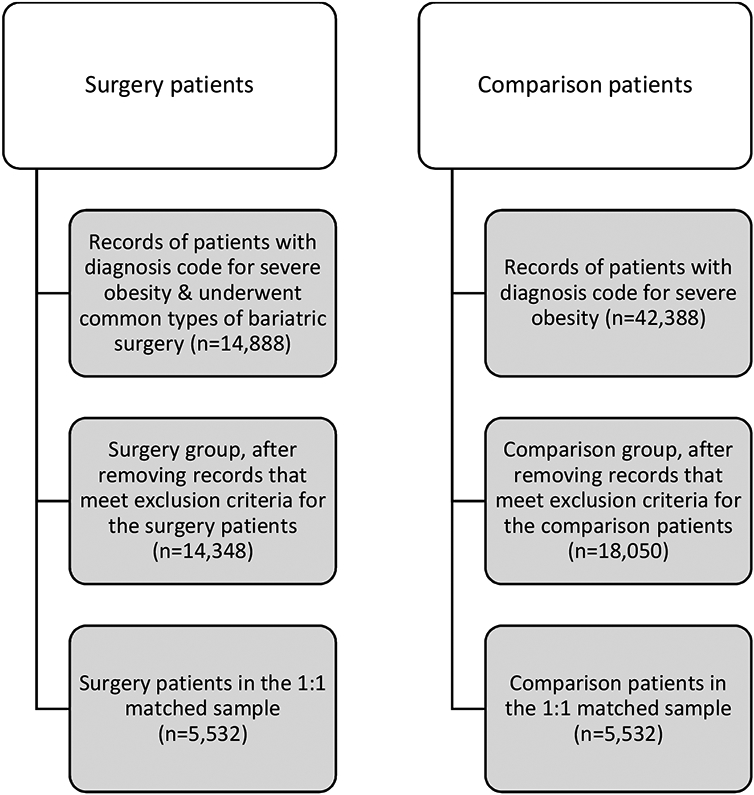

The international classification of disease/clinical modification procedure codes, ninth and tenth revisions (ICD-9, ICD-10), and Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System Level I Current Procedural Terminology (HCPCS CPT-4) codes used for identification of bariatric surgery and comparison patients are described in Appendix 1 (supplementary materials). Medicaid beneficiaries residing outside of Pennsylvania were excluded since coverage for bariatric surgery by Medicaid varies in some states [15]. Duplicate records in the inpatient and outpatient databases were identified and excluded using a pseudo patient identifier variable. The number of surgery patients in the second study population is smaller compared to the one described first as the surgery and comparison patients were 1:1 matched on several sociodemographic variables. Match tolerance in the software [IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 25.0; Armonk, NY, USA)] was set to a value of zero (exact match) for matching variables. Sampling was done without replacement. Figure 1 shows how the study samples were screened and selected.

Figure 1: Identification of study populations for the bariatric surgery and comparison groups.

Note. Diagnosis codes for morbid (severe) obesity were defined as 278.01 in the 9th and E66.01 in the 10th editions of international classification of disease. Obesity surgery types include sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.

Study design and variables

To examine the associations between socio-demographic factors, health insurance arrangements, and utilization of bariatric surgery, records of surgery patients were 1:1 matched by age group (18-34, 35-44, 45-54, 55-64, 65-76), sex, race, ethnicity, and zip code, and the year of medical bill’s claim with those of eligible patients who did not undergo surgery. This was done to control for the potential confounding effects of those socio-demographic factors on the odds of undergoing the surgery or having a certain type of insurance coverage.

The variables of interest were 1) demographic characteristics and the proportion of each major insurer type among all bariatric surgery patients captured in the 2014-2018 inpatient databases and 2) whether or not the patient had surgery during 2014-2018 in the 1:1 matched sample of bariatric surgery and comparison patients. Major payer types were defined as patients covered by Medicare, Medicaid, other government insurance, and private insurance; studied insurance plan types included PPO, fee-for-service, HMO, and point-of-service (POS) plans.

The primary predictor variables in the multivariable logistic regression models included payer type and insurance plan type, and, for patients covered by traditional Medicare, their secondary insurance coverage status/type. Patient age, sex, race, ethnicity, an estimate of median household income based on their area of residence, as well as the year when the patient encounter was recorded were included as covariates.

Statistical analysis

Contingency tables and Pearson Chi-Square tests were used to examine the associations between patient race, insurer type, and the year of bariatric surgery record within the cohort of all surgical patients. An independent t-test was used to compare the mean age in the matched surgery and comparison groups. Logistic regression analyses were performed to examine the association between payer type and the likelihood of undergoing bariatric surgery, as well as insurance plan type and the likelihood of undergoing the surgery, within Medicare and private payer categories. Medicaid beneficiaries were not considered for the latter model, since Medicaid fee-for-service beneficiaries transition into HMO (managed care) plans in a few months, after their initial enrollment in the Pennsylvania Medical Assistance program [16]. An additional logistic regression model was used to examine the association between secondary insurance arrangements and the odds of undergoing surgery among patients covered by traditional Medicare. Significance level was determined using an alpha of 0.05. The analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 25.0; Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Demographic characteristics of bariatric surgery patients

The study identified 14,348 patients who underwent bariatric surgery in an inpatient setting between 2014 and 2018. Almost half of the patients (45.3%) resided in Philadelphia county, followed by 13.9% in Montgomery county, 13.6% in Delaware county, 11.2% in Bucks county, and 6.5% in Chester county. Less than 10% (9.1%) of patients resided outside of Pennsylvania. The vast majority of bariatric surgery patients were women (80.5%) with a mean age of 43.3 ± 11.8 years. White (49.7%) and Black (40.8%) individuals comprised the largest racial groups with most (93.0%) not being of Hispanic/Latino origin or descent. Notably, there was a steady decrease in the proportion of white patients undergoing bariatric surgery from 55.1% in 2014 to 46.2% in 2018 and an increase in the proportion of Black patients, from 37.1% in 2014 to 43.0% in 2018. Similarly, the proportion of Hispanic/Latino origin or descent patients increased from 5.4% in 2014 to 8.0% in 2018. The demographic characteristics of these patients, stratified by year, are presented in Table 1.

Table 1:

Number of inpatient bariatric surgeries and patient characteristics in Southeastern Pennsylvania: overall 2014 to 2018 and by year (N=14,348)

| Variables | 2014- 2018 |

2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | Pearson Chi- Square, degree of freedom, p (2-sided) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. surgeries | 14,348 | 2,616 | 2,683 | 2,877 | 3,179 | 2,993 | |

| Age | |||||||

| Mean (SD) | 43.3 (11.8) |

44.1 (11.6) |

43.8 (11.9) |

43.2 (11.6) |

42.9 (11.9) |

42.8 (11.9) |

|

| Sex | |||||||

| Female N (%) | 11,549 (80.5) |

2,055 (78.6) |

2,131 (79.4) |

2,357 (81.9) |

2,569 (80.8) |

2,437 (81.4) |

|

| Male N (%) | 2,799 (19.5) |

561 (21.4) |

552 (20.6) |

520 (18.1) |

610 (19.2%) |

556 (18.6) |

|

| Race | X2=104.5, df=28, p<0.001 | ||||||

| White alone (%) | 7,126 (49.7) |

1,441 (55.1) |

1,431 (53.3) |

1,395 (48.5) |

1,477 (46.5) |

1,382 (46.2) |

|

| Black alone (%) | 5,856 (40.8) |

971 (37.1) |

1016 (37.9) |

1,206 (41.9) |

1,376 (43.3) |

1,287 (43.0) |

|

| Asian alone (%) | 42 (0.3) |

5 (0.2) |

8 (0.3) |

8 (0.3) |

12 (0.4) |

9 (0.3) |

|

| American Indian and Alaskan Native alone (%) | 6 (0.0) |

1 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

2 (0.1) |

1 (0.0) |

2 (0.1) |

|

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (%) | 3 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

1 (0.0) |

2 (0.1) |

|

| Two or More Race Groups (%) | 7 (0.0) |

1 (0.0) |

1 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0.0) |

5 (0.2) |

|

| Other (%) | 981 (6.8) |

146 (5.6) |

176 (6.6) |

201 (7.0) |

217 (6.8) |

241 (8.1) |

|

| Unknown (%) | 327 (2.3) |

51 (1.9) |

51 (1.9) |

65 (2.3) |

95 (3.0) |

65 (2.2) |

|

| Ethnicity | X2= 18.8, df=4, p=0.001 | ||||||

| Patient is of Hispanic/Latino origin or descent | 1,000 (7.0) |

142 (5.4) |

172 (6.4) |

200 (7.0) |

247 (7.8) |

239 (8.0) |

|

| Patient is not of Hispanic/Latino origin or descent | 13,348 (93.0) |

2,474 (94.6) |

2,511 (93.6) |

2,677 (93.0) |

2,932 (92.2) |

2,754 (92.0) |

Note. Data availability: Complete data available: age, sex, and ethnicity at 100%, race at 97.7%

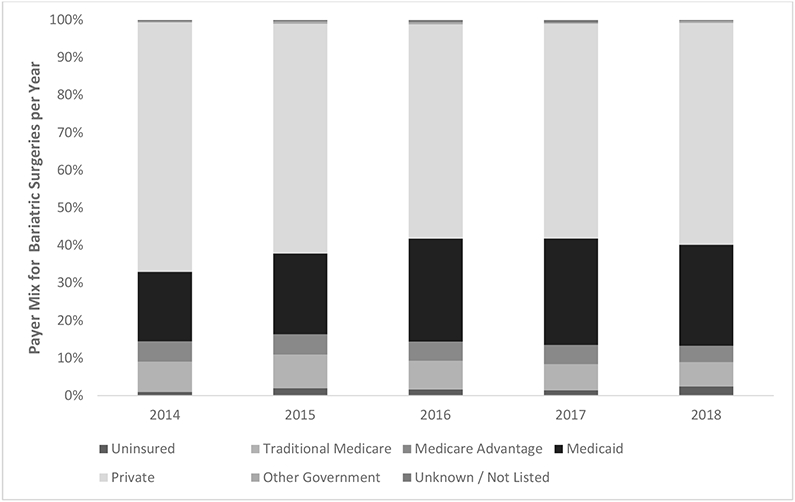

Payer mix for bariatric surgery

The largest insurer category for bariatric surgical procedures was private insurance (59.9%), followed by Medicaid (24.8%), traditional Medicare (7.6%), and Medicare Advantage (5.1%). As predicted, there was a steady increase of Medicaid’s share within the payer mix from 18.5% in 2014 to a high of 28.4% in 2017, followed by a slight decrease in 2018 to 26.9%. However, contrary to our a priori hypothesis, the share of Medicare Advantage plans within the payer mix decreased slightly from 5.5% in 2014 to 4.3% in 2018 (Figure 2). Appendix 2 (supplementary materials) presents more granular information about bariatric surgery patients’ insurance coverage (by insurer and insurance plan type) during 2014-2018. Appendix 3 (supplementary materials) provides a snapshot of the distribution of payer categories for inpatient bariatric surgeries in Southeastern Pennsylvania by county in 2014 vs 2018. The largest increase in the proportion of bariatric surgery patients with Medicaid coverage was in Philadelphia county (31.7%, n = 331 in 2014 vs 43.9%, n = 610 in 2018), followed by Bucks (5.9%, n = 16 vs 14.5%, n = 43), Chester (4.9%, n = 9 vs 10.2%, n = 15), Montgomery (10.0%, n = 41 vs 13.1%, n = 48), and Delaware counties (23.6%, n = 85 vs 24.5%, n = 87, respectively).

Figure 2: Proportion of insurer categories for inpatient bariatric surgeries in Southeastern Pennsylvania: 2014-2018 (N=14,348).

Note. X2= 163.4, df=24, p< 0.001

Logistic regression analysis results

After matching bariatric surgery and comparison patients 1:1 on age group, sex, race, ethnicity, zip code, and the year of medical bill’s claim, 11,064 patient records comprised the study sample – 5,532 in the surgery and 5,532 in the comparison groups. White patients comprised 49.8% of both the surgery and comparison groups, followed by 46.4% Black patients, 3.4% other races, and 0.4% individuals for whom race was not available in the record. Similarly, in both groups, 3.5% of patients were of Hispanic/Latino origin or descent and 83.0% were female. The mean age was 46.2 ± 11.9 in the surgery and 46.6 ± 12.4 in the comparison group (the difference was not statistically significant, P = 0.07). Payer type and insurance plan profile among matched bariatric surgery and comparison patients are presented in Table 2.

Table 2:

Payer and insurance plan profile for bariatric surgery vs comparison patients 1:1 matched on age group, sex, race, ethnicity, zip code, and the year of medical bill’s claim (N=11,064)

| Payer type | Insurance plan | Surgery group (n=5,532) |

Comparison group (n=5,532) |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (% within row) | ||||

| Medicare | 1,013 (44.9) | 1,241 (55.1) | 2,254 (100.0) | |

| Traditional Medicare (Parts A & B) Fee-for-service | 601 (41.2) | 856 (58.8) | 1,457 (100.0) | |

| Medicare Advantage PPO | 114 (67.1) | 56 (32.9) | 170 (100.0) | |

| Medicare Advantage HMO | 298 (47.5) | 329 (52.5) | 627 (100.0) | |

| Medicaid | 1,769 (51.8) | 1,648 (48.2) | 3,417 (100.0) | |

| Fee-for-service | 7 (10.1) | 62 (89.9) | 69 (100.0) | |

| HMO | 1,762 (52.6) | 1,586 (47.4) | 3,348 (100.0) | |

| Private insurance | 2,740 (51.0) | 2,636 (49.0) | 5,376 (100.0) | |

| PPO | 1,309 (51.7) | 1,222 (48.3) | 2,531 (100.0) | |

| POS | 128 (47.1) | 144 (52.9) | 272 (100.0) | |

| Fee-for-service | 625 (55.5) | 502 (44.5) | 1,127 (100.0) | |

| HMO | 678 (46.9) | 768 (53.1) | 1,446 (100.0) | |

| Other government | 10 (58.8) | 7 (41.2) | 17 (100.0) | |

| PPO | 4 (66.7) | 2 (33.3) | 6 (100.0) | |

| HMO | 6 (54.5) | 5 (45.5) | 11 (100.0) | |

As found in Table 3, the odds of undergoing bariatric surgery were smaller among patients who were Medicare beneficiaries compared to those with private insurance (OR = 0.78, 95% CI 0.70 - 0.87, P < 0.001), after adjusting for patient age, sex, race, ethnicity, estimated median household income, and year of record. The odds of undergoing bariatric surgery were not statistically different between those with Medicaid or other government insurance coverage vs privately insured patients.

Table 3:

Association of payer type and insurance plan type within payer category with odds of bariatric surgery

| Payer type/Insurer |

Insurance plan | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Payer type (n=11,062) | ||||

| Other government | - | 1.37 | 0.52 - 3.61 | 0.52 |

| Medicare | - | 0.78 | 0.70 - 0.87 | <0.001 |

| Medicaid | - | 1.05 | 0.95 - 1.15 | 0.35 |

| Private insurance | - | reference category | ||

| Model 2: Insurance plan type within Medicare (n=2,253) | ||||

| Medicare | PPO | 2.18 | 1.51 - 3.16 | <0.001 |

| Fee-for-service | 0.78 | 0.64 - 0.95 | 0.01 | |

| HMO | reference category | |||

| Model 3: Insurance plan type within private insurance (n=5,375) | ||||

| Private insurance | PPO | 1.21 | 1.06 - 1.38 | 0.006 |

| POS | 1.02 | 0.78 - 1.32 | 0.90 | |

| Fee-for-service | 1.39 | 1.19 - 1.63 | <0.001 | |

| HMO | reference category | |||

| Model 4: Medicare/Medicaid dual eligibility, supplemental private insurance, or no secondary insurance among patients with traditional Medicare (n=1,506) | ||||

| Traditional Medicare | No secondary insurance | 0.58 | 0.43 - 0.79 | 0.001 |

| Medicaid (dual coverage) | 0.68 | 0.51 - 0.91 | 0.01 | |

| Supplemental private insurance | reference category | |||

Note. All models were adjusted for patient age, sex, race, ethnicity, an estimate of median household income based on their area of residence (ZIP code), and the year when the patient encounter was recorded. PPO = preferred provider organization, POS = point-of-service, HMO = health maintenance organization.

Among those with Medicare, the Medicare Advantage PPO plan was associated with greater odds (OR = 2.18, 95% CI 1.51 - 3.16, P < 0.001) and fee-for-service plan (traditional Medicare parts A & B) with smaller odds (OR = 0.78, 95% CI 0.64 - 0.95, P = 0.01) of undergoing bariatric surgery compared to Medicare Advantage HMO plan. Among individuals with private insurance and known insurance plan, those with PPO (OR = 1.21, 95% CI 1.06 - 1.38, P = 0.006) and fee-for-service (OR = 1.39, 95% CI 1.19 - 1.63, P < 0.001) had greater odds of undergoing bariatric surgery, compared to beneficiaries of private HMO plans. POS plan was not a significant predictor in the model (Table 3).

In the logistic regression model examining the association between secondary insurance coverage and odds of undergoing bariatric surgery, lack of secondary coverage (OR = 0.58, 95% CI 0.43 - 0.79, P = 0.001) and Medicare/Medicaid dual eligibility (OR = 0.68, 95% CI 0.51 - 0.91, P = 0.01) were associated with smaller odds of undergoing surgery compared with having supplemental private insurance (Table 3).

All the presented regression models were adjusted for patient age, sex, race, ethnicity, estimated median household income, and year of record. We did not report the multiple adjusted effect estimates of these covariates to avoid “Table 2 fallacies,” i.e. presenting and interpreting confounder coefficients [17].

Discussion

Over the five-year period from 2014 to 2018, there was a notable increase in the proportion of Black (37.1% in 2014 vs 43.0% in 2018) and Hispanic individuals (5.4% vs 8.0%, respectively) and a substantial decrease in the proportion of white individuals (55.1% vs 46.2%) who underwent bariatric surgery. While the corresponding nationwide trends in bariatric surgery utilization from 2013-2016 followed the same direction, the national changes were much smaller (e.g. 66.5% white patients in 2013 vs 63.9% in 2016) [3]. The overall demographics of the region in relation to race and ethnicity did not change considerably from 2014 (66.7% white, 22.4% Black, and 7.9% Hispanic or Latino) to 2018 (65.4%, 22.3%, and 8.8% respectively) [8]. Given the overall growth in the number of surgeries between 2014 and 2018 (2,616 in 2014 vs 2,993 in 2018) and that the increase in rates of obesity among white individuals (29.5% in 2015 vs 31.5% in 2018) was slightly higher in Pennsylvania between 2015-2018 compared to Black individuals (37.1% in 2015 vs 38.1% in 2018),[18] this is likely a sign of greater access to bariatric surgery among Black and Hispanic individuals.

Within the payer mix, there was a considerable increase of Medicaid’s share (19.2% in 2014 vs 28.5% in 2018) that was balanced by a decrease in the proportions of patients with private insurance (66.7% vs 59.7%) and Medicare (14.0% vs 11.4%), from 2014 to 2018. These trends largely correspond to nationwide data on Medicaid’s share of bariatric surgeries from 2013-2016 (e.g. 10.3% of Medicaid’s share in 2013 vs 17.2% in 2016) [3].

Pennsylvania expanded its Medicaid program as of January 1, 2015. By February 2019, approximately 700,000 Pennsylvanians gained health insurance coverage as a result of the expansion [19]. Furthermore, if in 2014 the uninsured rates for the nonelderly were 8.8% among white, 14.8% among Black, and 19.4% among Hispanic individuals, the corresponding rates in 2018 were 6.0%, 8.1%, and 12.3% respectively, indicating a considerable narrowing of racial and ethnic disparities in access to health insurance [20]. This could explain the improved access to bariatric surgery among Black and Hispanic individuals and payer mix changes from 2014-2018.

This study detected statistically different odds of undergoing bariatric surgery based on payer type, but only between Medicare beneficiaries (22% smaller odds) compared to those with private insurance. After matching bariatric surgery and comparison patients from Southeastern Pennsylvania on several relevant sociodemographic variables, we did not detect statistically different odds of undergoing bariatric surgery based on having Medicaid, other government insurance vs private insurance coverage. It is likely that reported disparities in private vs public insurance coverage among bariatric surgery patients and eligible patients who did not undergo surgery are largely influenced by demographic and socio-economic factors [4,5,7].

As predicted, significantly different odds of undergoing bariatric surgery associated with insurance plan type within Medicare and private insurance payer categories, replicating the findings from earlier studies [9,12]. Particularly, individuals with PPO and fee-for-service insurance plans within the private insurance category had greater odds of undergoing bariatric surgery, compared with private HMO plan holders. This could be explained by the fact that PPO and fee-for-service plans are less restrictive in allowing enrollees to select a doctor or hospital and do not require referral for specialized care by primary care providers [9]. Similarly, among Medicare beneficiaries, those with Medicare Advantage PPO plans had greater odds of undergoing surgery compared to Medicare Advantage HMO plans.

Individuals with traditional Medicare (Parts A & B) fee-for-service plans had smaller odds of undergoing surgery as compared to beneficiaries of Medicare Advantage HMO plans. Furthermore, traditional Medicare beneficiaries with no supplementary insurance and those with dual eligibility had smaller odds of undergoing surgery (42% and 32%, respectively) as compared to those with private secondary insurance coverage; this likely has to do with patient cost-sharing arrangements within the traditional Medicare plan. Bariatric surgery patients covered by traditional insurance, but without supplementary/secondary insurance, may be responsible for part A (inpatient hospital care) and part B (physician services) deductibles and copayments [21]. Just more than one-fifth (21.7%) of the comparison patients vs 16.4% bariatric surgery patients covered by traditional Medicare did not have any supplemental insurance coverage. A previous study of commercial health insurance beneficiaries found higher utilization rates among insurance plans with lower cost-sharing (e.g. PPO plans), compared to high-deductible health plans; a $1,000 increase in cost-sharing was associated with 5 fewer bariatric surgeries per 100,000 insured individuals [22]. Thus, cost-sharing should not be used indiscriminately as a barrier to care; instead, patient out-of-pocket costs should be based on the clinical value of a specific bariatric procedure. The alignment of cost-sharing and clinical value by moving high-value services and medications into lower-priced tiers, adjusting cost-sharing based on patient characteristics, and incentivizing patients to seek high-performing providers are key principles of value-based insurance design [23,24].

This study has novel findings but also has limitations. The Pennsylvania Health Care Cost Containment Council’s databases allowed us to easily capture bariatric surgery patients from all hospitals (excluding Veterans Administration Hospitals) in Southeastern Pennsylvania. However, this was not true for the comparison group. Specifically, while bariatric surgery is currently recommended for adults with severe obesity (BMI ≥40 kg/m2), or those with a BMI ≥35 kg/m2 in the presence of at least one significant comorbidity associated with obesity,[25] we were able to only capture records of patients with a diagnosis code for severe obesity and were not able to identify patients by BMI. As a result, we may not have captured a small group of individuals with BMIs between 35–39 kg/m2 with severe a comorbidity, such as uncontrolled type II diabetes, and for whom the insurance company agreed to cover the use of surgical treatment. Also, bariatric surgery coverage by Medicaid varies by state [15]. Payer-mix and demographic factors may also vary across the United States, which may limit the generalizability of this study’s findings to other areas.

This study did not investigate other elements of insurance plan design for bariatric surgery that could impact utilization. One example of this is the requirement by many insurers for preoperative supervised medical weight management prior to surgery. A recent study from our research group found that among privately insured patients, the insurance requirement for 3-6 months preoperative supervised medical weight management was associated with smaller odds of undergoing surgery (OR = 0.459, 95% CI 0.253 - 0.832, P = 0.010), after adjusting for insurance plan type and the requirement for documented weight history [12]. The COVID-19 pandemic has made presenting for in-person medical care even more challenging, particularly for individuals from underserved communities. In response, many bariatric programs pivoted to increased utilization of telemedicine appointments to complete preoperative assessments and postoperative follow-up visits. Previous barriers to telemedicine (such as lower reimbursement rates or a requirement for the origination site to be a medical facility) were temporarily removed by public and private payers and bariatric surgery programs anecdotally reported a profound decrease in cancellations and no shows for appointments [26,27]. Continued use of telemedicine as part of bariatric surgery care beyond the pandemic could help to reorganize care around the patient and address some of the barriers to care due to insurance benefits design [26].

Conclusions

While private insurance remains the largest payer category for bariatric procedures in Southeastern Pennsylvania, there was a considerable increase in the proportion of patients with Medicaid from 2014-2018. It appears that there has also been an improvement in access to bariatric surgery among Black and Hispanic populations in the area. Given the profound and long-standing health disparity concerns in bariatric surgery, and obesity care in general, we find this small, yet meaningful change encouraging. We are optimistic that larger changes will be observed in the years and decades to come. Such changes will be critical to the ability of the American healthcare system to manage the obesity epidemic and provide equal access to patients.

Furthermore, the findings support the notion that insurance plan design and cost-sharing arrangements may be as important in determining the access and utilization of bariatric surgery as the general payer type when controlling for potentially confounding socio-demographic factors. Careful examination of the bariatric surgery benefit design and application of value-based insurance design to bariatric surgery [28] may improve the access to this potentially life-saving surgery for many Americans. Particularly, several studies documented the cost-effectiveness of bariatric surgery for adults with severe obesity and diabetes compared with usual medical care or intensive lifestyle intervention [29-31]. Some employers have already incorporated elements of value-based insurance design to bariatric surgery coverage in their self-administered insurance benefit plans (for example, via offering coverage for bariatric surgery at a designated center of excellence and reimbursing patient out-of-pocket expenses if a planned weight reduction goal is achieved in a certain timeframe) [28]. Further research could help evaluate the health and economic implications of applying value-based insurance design to bariatric surgery coverage.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Insurance plan type is strongly associated with the uptake of bariatric surgery.

So is supplemental insurance coverage among traditional Medicare beneficiaries.

The proportion of Black and Hispanic surgery patients increased in Southeastern PA.

Within the payer mix, there was an increase in Medicaid patients during 2014-2018.

Acknowledgments

Disclosures: Dr. David B. Sarwer discloses grant funding to support his research in the area of bariatric surgery from the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Disease (R01-DK-108628-01); the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (1R01DE026603-01A1); and the Common-wealth of Pennsylvania (PA CURE). He has consulting relationships with Ethicon and Novo Nordisk. Dr. Hamlet Gasoyan, Dr. Jennifer K. Ibrahim, and Dr. William E. Aaronson do not have anything to disclose.

The Pennsylvania Health Care Cost Containment Council (PHC4) is an independent state agency responsible for addressing the problem of escalating health costs, ensuring the quality of health care, and increasing access to health care for all citizens regardless of ability to pay. PHC4 has provided data to this entity in an effort to further PHC4’s mission of educating the public and containing health care costs in Pennsylvania.

PHC4, its agents, and staff, have made no representation, guarantee, or warranty, express or implied, that the data—financial, patient, payor, and physician specific information—provided to this entity, are error-free, or that the use of the data will avoid differences of opinion or interpretation.

This analysis was done by the authors at Temple University. PHC4, its agents and staff, bear no responsibility or liability for the results of the analysis, which are solely the opinion of the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Wolfe BM, Kvach E, Eckel RH. Treatment of Obesity. Circ Res 2016;118:1844–55. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.307591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Colquitt JL, Pickett K, Loveman E, Frampton GK. Surgery for weight loss in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014. 10.1002/14651858.CD003641.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [3].Campos GM, Khoraki J, Browning MG, Pessoa BM, Mazzini GS, Wolfe L. Changes in Utilization of Bariatric Surgery in the United States From 1993 to 2016. Ann Surg 2020;271:201–9. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Martin M, Beekley A, Kjorstad R, Sebesta J. Socioeconomic disparities in eligibility and access to bariatric surgery: a national population-based analysis. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2010;6:8–15. 10.1016/j.soard.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Mainous AG, Johnson SP, Saxena SK, Wright RU. Inpatient Bariatric Surgery Among Eligible Black and White Men and Women in the United States, 1999–2010. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:1218–23. 10.1038/ajg.2012.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bhogal SK, Reddigan JI, Rotstein OD, Cohen A, Glockler D, Tricco AC, et al. Inequity to the Utilization of Bariatric Surgery: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Obes Surg 2015;25:888–99. 10.1007/s11695-015-1595-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hecht LM, Pester B, Braciszewski JM, Graham AE, Mayer K, Martens K, et al. Socioeconomic and Racial Disparities in Bariatric Surgery. Obes Surg 2020;30:2445–9. 10.1007/s11695-020-04394-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2018. https://www.census.gov/acs/www/data/data-tables-and-tools/data-profiles/2018/ (accessed December 18, 2020).

- [9].Gasoyan H, Halpern MT, Tajeu G, Sarwer DB. Impact of insurance plan design on bariatric surgery utilization. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2019;15:1812–8. 10.1016/j.soard.2019.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hennings DL, Baimas-George M, Al-Quarayshi Z, Moore R, Kandil E, DuCoin CG. The Inequity of Bariatric Surgery: Publicly Insured Patients Undergo Lower Rates of Bariatric Surgery with Worse Outcomes. Obes Surg 2018;28:44–51. 10.1007/s11695-017-2784-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Chhabra KR, Fan Z, Dimick JB, Telem DA. Role of Private Insurance Markets in Use of Bariatric Surgery. J Am Coll Surg 2019;229:S162–3. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2019.08.358. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gasoyan H, Soans R, Ibrahim JK, Aaronson WE, Sarwer DB. Do Insurance-mandated Precertification Criteria and Insurance Plan Type Determine the Utilization of Bariatric Surgery Among Individuals With Private Insurance? Med Care 2020. 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [13].Pennsylvania Health Care Cost Containment Council. Services & Data Requests [homepage on the Internet]. Harrisburg, PA: 2020. http://www.phc4.org/services/datarequests/data.htm (accessed October 8, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- [14].Stahl JM, Malhotra S. Obesity Surgery Indications And Contraindications. 2019. [PubMed]

- [15].Jannah N, Hild J, Gallagher C, Dietz W. Coverage for Obesity Prevention and Treatment Services: Analysis of Medicaid and State Employee Health Insurance Programs. Obesity 2018;26:1834–40. 10.1002/oby.22307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].The Pennsylvania Health Law Project. Medical Assistance in PA: Frequently Asked Questions n.d. http://www.phlp.org/home-page/providers/provider-faq/medical-assistance-in-pa-frequently-asked-questions.

- [17].Westreich D, Greenland S. The Table 2 Fallacy: Presenting and Interpreting Confounder and Modifier Coefficients. Am J Epidemiol 2013;177:292–8. 10.1093/aje/kws412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].United Health Foundation. Annual Report: Obesity in Pennsylvania [homepage on the Internet]. Am Heal Rank 2020. https://www.americashealthrankings.org/explore/annual/measure/Obesity/state/PA?edition-year=2018 (accessed October 8, 2020).

- [19].Pennsylvania Department of Human Services. 2019 Medicaid Expansion Report Update. 2019.

- [20].Kaiser Family Foundation. Uninsured Rates for the Nonelderly by Race/Ethnicity 2020. https://www.kff.org/uninsured/state-indicator/nonelderly-uninsured-rate-by-raceethnicity/?currentTimeframe=5&selectedRows=%7B%22states%22:%7B%22pennsylvania%22:%7B%7D%7D%7D&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D (accessed December 18, 2020).

- [21].U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Is my test, item, or service covered? Bariatric surgery. n.d. https://www.medicare.gov/coverage/bariatric-surgery.

- [22].Chhabra KR, Fan Z, Chao GF, Dimick JB, Telem DA. The Role of Commercial Health Insurance Characteristics in Bariatric Surgery Utilization. Ann Surg 2019;Publish Ah:1. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Buxbaum J, de Souza J, Fendrick AM. Using clinically nuanced cost sharing to enhance consumer access to specialty medications. Am J Manag Care 2014;20:e242–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Hirth RA, Cliff EQ, Gibson TB, McKellar MR, Fendrick AM. Connecticut’s Value-Based Insurance Plan Increased The Use Of Targeted Services And Medication Adherence. Health Aff 2016;35:637–46. 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Mechanick JI, Youdim A, Jones DB, Timothy Garvey W, Hurley DL, Molly McMahon M, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Perioperative Nutritional, Metabolic, and Nonsurgical Support of the Bariatric Surgery Patient—2013 Update: Cosponsored by American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, The Obesity Society, and American Society fo. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2013;9:159–91. 10.1016/j.soard.2012.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Chao GF, Ehlers AP, Telem DA. Improving obesity treatment through telemedicine: increasing access to bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2020. 10.1016/j.soard.2020.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Sarwer DB. Mask Wearing and Interpersonal Interactions. CommonHealth 2020;1:153–6. 10.15367/ch.v1i3.422. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Gasoyan H, Tajeu G, Halpern MT, Sarwer DB. Reasons for underutilization of bariatric surgery: The role of insurance benefit design. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2019;15:146–51. 10.1016/j.soard.2018.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kim DD, Arterburn DE, Sullivan SD, Basu A. Economic Value of Greater Access to Bariatric Procedures for Patients With Severe Obesity and Diabetes. Med Care 2018;56:583–8. 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Hoerger TJ, Zhang P, Segel JE, Kahn HS, Barker LE, Couper S. Cost-Effectiveness of Bariatric Surgery for Severely Obese Adults With Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2010;33:1933–9. 10.2337/dc10-0554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Keating C, Neovius M, Sjöholm K, Peltonen M, Narbro K, Eriksson JK, et al. Health-care costs over 15 years after bariatric surgery for patients with different baseline glucose status: results from the Swedish Obese Subjects study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2015;3:855–65. 10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00290-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.