Abstract

The level of circulating interferon-γ (IFNγ) is elevated in various clinical conditions including autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, sepsis, acute coronary syndrome, and viral infections. As these conditions are associated with high risk of myocardial dysfunction, we investigated the effects of IFNγ on 3D fibrin-based engineered human cardiac tissues (“cardiobundles”). Cardiobundles were fabricated from human pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes, exposed to 0–20ng/ml of IFNγ on culture days 7–14, and assessed for changes in tissue structure, viability, contractile force and calcium transient generation, action potential propagation, cytokine secretion, and expression of select genes and proteins. We found that application of IFNγ induced a dose-dependent reduction in contractile force generation, deterioration of sarcomeric organization, and cardiomyocyte disarray, without significantly altering cell viability, action potential propagation, or calcium transient amplitude. At molecular level, the IFNγ-induced structural and functional deficits could be attributed to altered balance of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, upregulation of JAK/STAT signaling pathway (JAK1, JAK2, and STAT1), and reduced expression of myosin heavy chain, myosin light chain-2v, and sarcomeric α-actinin. Application of clinically used JAK/STAT inhibitors, tofacitinib and baricitinib, fully prevented IFNγ-induced cardiomyopathy, confirming the critical roles of this signaling pathway in inflammatory cardiac disease. Taken together, our in vitro studies in engineered myocardial tissues reveal direct adverse effects of pro-inflammatory cytokine IFNγ on human cardiomyocytes and establish the foundation for a potential use of cardiobundle platform in modeling of inflammatory myocardial disease and therapy.

Keywords: hiPSC, inflammation, secretome, fibrin hydrogel, COVID-19

Graphic abstract

1. Introduction

Systemic inflammation is a complex pathological process, which manifests clinically in various forms [1] and is frequently associated with increased risk of cardiovascular diseases, including cardiomyopathy. Rheumatoid arthritis, for example, is a chronic systemic inflammatory disease which affects approximately 1% of the population [2] and carries high risk of congestive heart failure [3–5]. Similarly, 50% of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus have been diagnosed for myocardial involvement in post-mortem assessments [6]. According to multiple clinical studies [1, 7–10], 20–68% of patients with sepsis and septic shock develop myocardial dysfunction, which manifests in contractile deficit, ventricular dilatation, and reduced cardiac response to volume loading [9–11]. Similar to sepsis, waves of systemic inflammation in patients with newly emerging viral infections, such as H1N1 influenza virus [12] and COVID-19 [13], are also associated with unusually high occurrence of cardiomyopathy. How does systemic inflammation lead to myocardial dysfunction is still not well-understood.

Cytokines are key modulators of inflammatory processes [14]. As an important pro-inflammatory cytokine, interferon-γ (IFNγ) is predominantly produced by immune cells such as T helper 1, CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, and activated natural killer cells. In healthy individuals, IFNγ production is tightly regulated by monocyte-/macrophage-derived cytokines [15], with blood levels being normally below 10 pg/ml [16]. However, in a variety of autoimmune diseases [17, 18], sepsis and septic shock [19, 20], acute coronary syndrome [21, 22], and viral infections [23], concentration of IFNγ in the blood is significantly elevated, thus overlapping with diseases with increased occurrence of myocardial dysfunction. In chronic inflammatory conditions, serum IFNγ rises to be as high as several hundred pg/ml [17], whereas in patients with septic shock IFNγ concentration can be several ng/ml [20]. It has been debated if IFNγ has harmful or beneficial roles in rodent and human hearts [24]. Overexpression of IFNγ in mice led to ventricular dilation and systolic impairment [25], while in vitro studies in rat [26] and mouse [27, 28] cardiomyocytes showed protective roles of IFNγ in a pressure overload setting. In human studies, a case report on a patient with renal carcinoma showed that following systemic IFNγ treatment, the patient developed reversible congestive heart failure [29]. Profiling multiple cytokines in patients with sepsis revealed persistently higher plasma IFNγ levels in non-survivors [20, 30], while strong IFNγ response to parasitic infection has been associated with Chagas disease cardiomyopathy [31].

Since IFNγ can have complex effects on multiple cell types present in the heart [32] and its systemic elevation is often accompanied with altered levels of other cytokines, it is challenging to dissect IFNγ-specific effects on human cardiomyocyte survival and function in vivo. Development of reproducible methods to derive human cardiomyocytes from pluripotent stem cells (hPSC-CMs) [33] and engineering of functional cardiac tissues have enabled in vitro studies of patient-specific, cell-autonomous response of cardiomyocytes to various growth factors, cytokines, and pharmacological agents. Yet, there have been no studies that examined how chronically elevated levels of IFNγ may affect structural and functional properties of hPSC-CMs. We have previously established methodology for engineering highly mature 3-dimensional (3D) fibrin-based hPSC-CM tissues (“cardiopatches and cardiobundles”) amenable to studies of myocardial function and drug response [34–37]. In the present study, we have first-time examined how chronic application of IFNγ affects cardiobundle structure, viability, contractile function, action potential propagation, cytokine secretion, and gene and protein expression. Collectively, our studies reveal direct adverse effects of IFNγ on structure and function of human cardiomyocytes that can be prevented by JAK/STAT inhibitors prescribed to patients with chronic inflammatory diseases. These results warrant further developments of human cardiobundles as a potential in vitro platform for studies of inflammatory cardiomyopathy.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. hiPSC maintenance and cardiomyocyte differentiation

hiPSCs were maintained and differentiated to cardiomyocytes as previously described [35, 36]. Briefly, hiPSCs (P25-P50) derived from normal human epidermal keratinocytes at Duke University were cultured in mTESR1 plus media (Stemcell Technologies) and passaged every 4–5 days with 0.5 mM EDTA in PBS. To initiate cardiomyocyte differentiation, hiPSCs were detached with accutase (Stemcell Technologies) treatment and seeded in 10-cm dishes at a density of 6.4×105/cm2. Cells in monolayer were allowed to grow for 3 days and media switched to RPMI-1640 media supplemented with B27 minus insulin (RB−, Stemcell Technologies). Cells were treated with CHIR 99021 (12 μM, Tocris Bioscience), recombinant activin A (60 ng/ml, R&D Systems) and ascorbic acid (50 μg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich) for 24 hours, followed by endo-IWR 1 (5 μM, Tocris Bioscience) for 5 days, of which ascorbic acid (50 μg/ml) was included during the first 3 days. Thereafter, cells were incubated in RPMI-1640 and insulin-supplemented B27 (RB+, Stemcell Technologies). Spontaneous contractions of hiPSC-CMs usually appeared on the 5th day after initiation of differentiation. hiPSC-CM purity determined by flow cytometry for cardiac troponin T (cTnT) ranged between 75% and 89%. No metabolic selection [38] was applied.

2.2. Cardiobundle fabrication and culture

Cardiobundles were fabricated from hiPSC-CMs after 15–21 days of differentiation, as previously described [36]. Briefly, 2.75×105 cells were mixed in a fibrin-based hydrogel and cell/gel solution (27.5 μl) was cast inside a PDMS mold containing a Cerex® frame (Fig. 1A). First seven days, cardiobundles were cultured in a serum-free RPMI-1640-based medium containing 2.8 mM glucose, 8.4 mM galactose, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 45 μM L-ascorbic acid 2-phosphate sesquimagnesium, 2% B27 supplement, 1% MEM, 100 u/ml penicillin-streptomycin, and 0.2% aminocaproic acid (ACA). Subsequently tissues were cultured for additional 7 days in a DMEM-based medium containing 0.2% ACA, 100 u/ml of penicillin-streptomycin and 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS). DMEM-based medium was prepared from glucose- and bicarbonate-free DMEM powder (D5030, Sigma, St Louis, MO) by adding 2.8 mM glucose and 8.4 mM galactose as energy substrates and 25 mM sodium bicarbonate. Cardiobundles were cultured in a 5% CO2 incubator on a rocking platform [36] and after 2 weeks structural, molecular, and functional assessments were performed only if control myobundles (not treated with any cytokines or drugs) paced at 2 Hz produced average contractile force larger than 1mN (>85% of cases).

Figure 1.

Seven-day IFNγ treatment of human cardiobundles reduces contractile force generation without altering calcium transients. A) Schematics of experimental timeline involving hiPSC-CM differentiation, cardiobundle formation, culture, and assessments. B) Representative force traces during 2 Hz stimulation recoded from 2-week cardiobundles treated with specified doses of IFNγ on culture days 7–14. C-E) Quantified cardiobundle twitch force amplitude (C), contraction time (D), and relaxation time (E) as a function of 7-day application of IFNγ at different doses (n = 5–6 cardiobundles per group). F-G) Representative calcium transients and quantified Ca2+ transient amplitudes (ΔF/F of Fluo-4) of untreated (0 ng/ml) and IFNγ-treated (20 ng/ml) cardiobundles during 1 Hz (F) and 2 Hz (G) stimulation (n = 7–8 cardiobundles per group). *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 vs. 0 ng/ml IFNγ.

2.3. IFNγ, IL-6, IL-1α, and JAK inhibitor applications

Human recombinant IFNγ (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ) was prepared as 50 μg/ml stock solution in 0.1% BSA-containing PBS. One day after tissues were switched to DMEM-based medium, IFNγ was added to culture medium for 7 days. For the dose-response experiment, the applied concentrations of IFNγ in the media were 0, 0.01, 0.1, 1, and 20 ng/ml. IFNγ was removed at least 4 hours before functional assessments. Because other cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-1 have been reported to affect cardiomyocytes of rodents directly or indirectly [39, 40], we also assessed cardiobundle contractile force in response to similarly applied doses (0, 0.01, 0.1, 1, and 20 ng/ml) of IL-6 (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ) and IL-1α (Biolegend, San Diego, CA). For pharmacological experiments, two JAK inhibitors, tofacitinib and baricitinib (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), were prepared as 500 μM stock solutions in water and DMSO, respectively, before being added to tissue culture media. Each drug was applied 24 hours before and then during IFNγ application.

2.4. Measurement of isometric contractile force

Contractile force generation in cardiobundles was measured isometrically, as previously described [34–36, 41]. Briefly, cardiobundles were immersed in Tyrode’s solution containing 1.8 mM Ca2+, fixed at one end and connected at another end to a force transducer attached to a computer-controlled linear actuator (Thorlabs, Newton, NJ). Contractions were evoked by electric field stimulation via two parallel platinum electrodes (2 Hz rate and 3 V/cm amplitude) while tissue was stretched in 8% increments until 24% elongation. Passive tension, twitch force amplitude and kinetics (10–90% contraction and relaxation times) were determined using custom MATLAB software [42].

2.5. Optical mapping of action potential propagation

Action potential propagation in cardiobundles was optically mapped using a voltage-sensitive die Di-4-ANEPPS (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), as previously described [42, 43]. Briefly, tissues were stained with Di-4-ANEPPS for 5 min at room temperature and placed in 37°C Tyrode’s solution supplemented with 10 μM Blebbistatin to prevent contraction artifacts. A bipolar platinum point-electrode positioned at one end of the bundle was used to stimulate tissues at 2 Hz rate. Recorded signals were filtered and used to construct isochrone map of action potential propagation and determine conduction velocity (CV) and action potential duration at 80% repolarization (APD) by a custom MATLAB software.

2.6. Imaging of calcium transients

Calcium transient recordings were performed as previously described [36, 44]. Briefly, cardiobundles were incubated with 10 μM Fluo-4 AM (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) at 37°C for 30 min followed by 30 min incubation in Tyrode’s solution at room temperature. Tissues were subsequently incubated in 37°C Tyrode’s solution supplemented with 10 μM Blebbistatin and stimulated at 1Hz and 2Hz rate by a point-electrode positioned at one end of cardiobundle. Fluorescence images were acquired at 4X magnification and 80 fps using a Nikon EclipseTE2000 microscope and a fast EMCCD camera (iXonEM+, Andor). Regions of interest in the center of the cardiobundle were selected and the mean pixel intensity was measured as a function of time and analyzed by a custom MATLAB software. Amplitude of calcium transients was determined from relative changes in fluorescence intensity (ΔF/F) [36, 44].

2.7. Immunofluorescence analysis

Immunostaining of cardiobundles was performed as previously described. Briefly, cardiobundles were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS at 4°C overnight and used for whole-mount staining or snap-frozen in Tissue-Tek OCT (Sakura FineTek USA, Torrance, CA) for staining of cryosections. For whole-mount stains, tissues were incubated at 4°C overnight in 0.5% Triton X-100, 5% chicken serum, and 2.5% BSA in PBS and incubated with primary antibodies diluted in the blocking solution at 4°C for 12 hours (Supp. Table 1). Alexa Flour 488- and Alexa Flour 594-conjugated secondary antibodies (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA), DAPI, and Alexa Flour 647-conjugated phalloidin (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) were applied at 4°C overnight. For cross-sectional stains, OCT-embedded cardiobundles were cut into 10-μm-thick sections, incubated for 90 min with blocking solution (with 0.2% Triton X-100), followed by 90 min incubation with secondary antibodies. Whole-mount tissues or cross-sections were mounted with Fluoromount-G (SoutherBiotech, Bringham, AL) and imaged with a TCS SP5 Leica confocal microscope.

2.8. Transmission electron microscopy

Samples for transmission electron microscopy were prepared as previously described [42]. Briefly, cardiobundles were washed with Cacodylate buffer and fixed overnight with 2% buffered gluteraldehyde at 4 °C. After 1% OsO4 post-fixation, samples were sequentially dehydrated in a series of ascending acetone concentrations (70%, 95%, 100%), then placed in the 50/50 acetone:epoxy overnight, followed by embedding in 100% epoxy and baking at 60 °C overnight. Ultrathin sections were placed on copper grids and stained with uranyl acetate. Images were acquired using Philips CM12 transmission electron microscope operated at 200 kV, with XR60 camera system (Advanced Microscopy Techniques).

2.9. TUNEL assay

Apoptotic cell death was detected using the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay, as previously described [45, 46]. Cardiobundle cross-sections were stained with Click-iT® TUNEL kit (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and nuclei were stained with DAPI. Sections were imaged with a TCS SP5 Leica confocal microscope. The percentage of TUNEL-positive cells was calculated by dividing the number of TUNEL-positive spots with the number of DAPI-positive nuclei in each section.

2.10. Morphometric image analysis

The direction and dispersion of sarcomeres in whole-mount sarcomeric α-actinin (SAA) stained cardiobundles were determined using the Directionality plug-in in ImageJ-Fiji by randomly analyzing 0.003 mm2 areas of each tissue after software auto-thresholding with the default method. Nuclear dispersion was determined in DAPI-stained whole-mount sections by analysis of 0.3 mm2 areas with the same procedure. Similarly, characteristics of individual DAPI-stained nuclei, including circularity and lengths of major and minor nuclear axes, were determined using particle analysis in ImageJ-Fiji, in a 0.006 mm2 area in each section.

2.11. qRT-PCR analysis

Gene expression analysis was performed as previously described [36, 44]. Extraction and purification of RNA from snap-frozen cardiobundles were carried out with a Qiagen RNeasy® fibrous tissue mini kit (Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands) per manufacturer instructions. The RNA concentration yielded was determined by a Qubit™ RNA HS assay Kit (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA). One hundred nanograms of RNA were used to synthesize cDNA using an iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Gene expression was analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR using a SYBR qPCR Supermix in 10 μl of the reaction solution. The sequences of primers have been listed in a previous study [35]. Expression levels of genes of interest were first calculated relative to expression level of a reference human hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase-1 (HPRT-1) gene. These relative expression levels in IFNγ-treated samples were then shown normalized to corresponding relative expression levels in untreated control samples.

2.12. Western blot analysis

Protein expression in cardiobundles was assessed by Western blotting as previously described [36, 47]. Expression of contractile proteins, myosin heavy chain (MHC), myosin light chain 2v (MLC-2v), SAA, and cardiac troponin-T (cTnT) was assessed at day 7 of IFNγ treatment, whereas expression of JAK/STAT signaling proteins was evaluated 48 or 96 hours after start of IFNγ treatment. Proteins were extracted with RIPA lysis and extraction buffer (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and protein concentrations measured using a BCA assay with bovine serum albumin as the standard. Proteins were loaded onto 4–15% gradient Mini-PROTEAN gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), separated through electrophoresis, and transferred onto PVDF membranes. After blocking, membranes were incubated with primary antibodies (Supp. Table 1) at 4°C overnight before application of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX). After washes, the membranes were incubated with Amersham ECL prime Western blotting detection reagent and imaged using a Bio-Rad Chemidoc apparatus (Hercules, CA). The integrated optical density for each protein in the loaded sample was semi-quantified using ImageJ and normalized to that of housekeeping protein GAPDH.

2.13. Quantification of cytokines in culture media

At ninety-six hours of IFNγ exposure, the culture medium from each well was collected for cytokine measurements. Eighteen cytokines, IL-1β, IL-4, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-12p70, IL-15, IL-17A, IL-18, IL-21, IL-23, GM-CSF, fractalkine (CX3CL1), IFNγ, leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), MCP-1 (CCL2), RANKL, and TNFα, were detected using a custom-designed human magnetic 18-plex panel for the Luminex platform (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA). All independent samples were thawed and analyzed on the same plate. For each independent sample, three replicates were measured, and the values were averaged.

2.14. Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Two-group comparisons were performed with an unpaired t-test, whereas differences among more than two groups were analyzed with one-way ANOVA following Tukey’s or Dunnett’s test for multiple group comparisons, as appropriate. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. IFNγ induces contractile force decline in cardiobundles without affecting the amplitude of calcium transients

A seven-day treatment of human cardiobundles with IFNγ induced a dose-dependent decrease in contractile force generation, with the highest concentration of 20 ng/ml yielding a force decline of more than 3-fold (Fig. 1B&C). Except for a minimal effect at the highest studied dose, the kinetics of cardiobundle contraction and relaxation were unaffected by IFNγ (Fig. 1D&E). In contrast to IFNγ, contractile function of cardiobundles was unaltered by 7-day treatment with IL-1α, IL-6, or TNFα at doses of up to 1–20 ng/ml (Supp. Fig. 1). We further examined if the IFNγ-induced force decline was associated with changes in calcium transient amplitude. Even at the highest studied IFNγ dose, calcium transient amplitudes during 1 or 2 Hz pacing were not statistically different from those recorded in control (untreated) cardiobundles (Fig. 1F&G). In addition, we optically mapped action potential propagation in cardiobundles treated with different doses of IFNγ (Supp. Fig. 2A) and found no effects on conduction velocity (CV, Supp. Fig. 2B) or action potential duration (APD, Supp. Fig. 2C). Taken together, continuous 7-day exposure of cardiobundles to a pro-inflammatory cytokine IFNγ induced contractile force deficit without affecting action potential propagation or calcium transient amplitude.

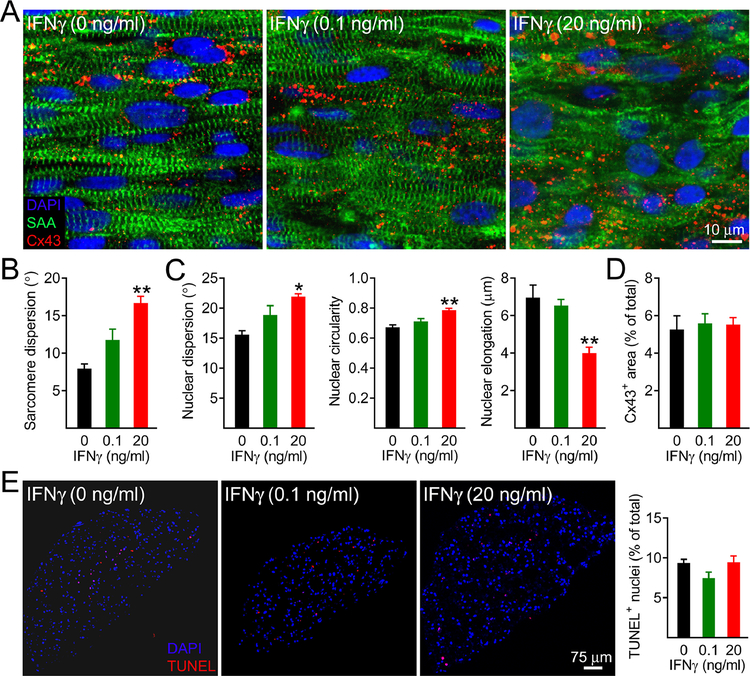

3.2. IFNγ induces myofibrillar disarray in cardiobundles without increasing cell death

To assess if the 7-day IFNγ treatment altered tissue morphology and sarcomeric structure, we stained sarcomeric α-actinin (SAA) and connexin-43 (Cx43, Fig. 2A). Compared to untreated control, the IFNγ treatment induced sarcomeric and nuclear disarray and decreased nuclear elongation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2A–C), while no apparent changes in the Cx43 density were observed (Fig. 2A&D), consistent with the lack of changes in conduction velocity. IFNγ-induced sarcomere loss and disorganization were also apparent in transmission electron microscopy images (Supp. Fig. 3). We then applied TUNEL immunostaining assay to detect apoptotic and necrotic cell death [48, 49] and found similar percentages of TUNEL+ nuclei in cardiobundle cross-sections independent of the IFNγ treatment (Fig. 2E). To further confirm these results, we assessed the apoptotic cell death by immunostaining and western blot analyses for cleaved caspase-3 and found no differences among the assessed groups at 48h or 7 days of treatment (Supp. Fig. 4). Cardiobundle cross-sectional area following IFNγ exposure appeared larger (Supp. Fig. 4A), suggestive of changes in tissue remodeling. Collectively, these studies revealed that contractile force deficit in human cardiobundles induced by 7-day IFNγ treatment could be primarily attributed to significant myofibrillar disorganization in cardiomyocytes without compromise in cell viability.

Figure 2.

Seven-day IFNγ treatment of cardiobundles induces myofibrillar disarray without loss in cell viability. A) Representative whole-tissue immunostains of cardiobundles treated for 7 days with specified doses of IFNγ. SAA, sarcomeric α-actinin; Cx43, connexin-43; DAPI, nuclei. Note increased cardiomyocyte misalignment and sarcomere disorganization with increased doses of IFNγ. B) Quantitative analysis of sarcomere misalignment (dispersion) as a function of IFNγ dose. C) Quantitative analyses of nuclear misalignment (dispersion), circularity (1 = perfect circle), and elongation (major – minor axis difference in a best fit ellipse). D) Quantification of percent imaged area positive for Cx43 (n = 4–6 cardiobundles per group). E) Representative TUNEL stainings of cardiobundle cross-sections and corresponding quantifications of fractions of TUNEL+ nuclei, shown for specified doses of IFNγ (n = 6–8 cardiobundles per group). *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.001 vs. 0 ng/ml IFNγ.

3.3. IFNγ downregulates expression of contractile proteins in cardiobundles while upregulating expression of corresponding genes

To assess potential changes in contractile gene and protein expression induced by IFNγ, we performed qRT-PCR and western blot analyses. Compared to control tissues, cardiobundles exposed to 20 ng/ml IFNγ for 7 days showed significant upregulation of MYH6, MYH7, MYL2, and TNNT2 genes (Fig. 3A) from 3–11 fold. Interestingly, these gene expression changes were not paralleled with upregulated expression of contractile proteins. Rather, protein expression levels of MHC, cTnT, MLC-2v, and SAA showed decreasing trends with increasing doses of IFNγ, with MHC, SAA and MLC-2v protein levels declining in the presence of 20 ng/ml of IFNγ by more than two-fold compared to expression in control tissues (Fig. 3B&C). Overall, these results demonstrated that IFNγ-induced myofibrillar disarray in cardiobundles was associated with significant post-transcriptional downregulation of contractile proteins, which contrasted upregulated expressions of corresponding contractile genes.

Figure 3.

Seven-day IFNγ treatment of cardiobundles decreases expression of sarcomeric proteins and upregulates expression of corresponding genes. A) Quantified expression of sarcomeric genes shown relative to 0 ng/ml group. All mRNA expression levels were first normalized to expression of reference gene HPRT-1 (n = 3 samples per group). MYH6 and MYH7 genes coding for α- and β-myosin heavy chain (MHC), respectively; MYL2 coding for ventricular myosin light chain-2 (MLC-2v); TNN2 coding for cardiac troponin T (cTnT). B) Representative Western blots for MYH, MLC-2v, cTnT, and sarcomeric α-actinin (SAA). C) Corresponding quantification of expressed proteins normalized to GAPDH (n = 6 samples per group). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 vs. 0 ng/ml IFNγ.

3.4. IFNγ alters secretome of cardiobundles

Since IFNγ has been shown to alter cytokine expression in various tissues [50–52], we quantified levels of cardiobundle-secreted proteins in culture media with and without IFNγ treatment (Fig. 4). As expected, IFNγ secretion by control tissues was below detection limit, while adding 20 ng/ml IFNγ to culture media expectedly resulted in the presence of high exogenous IFNγ levels of ~15 ng/ml. Furthermore, the presence of IFNγ increased or stimulated cardiobundle secretion of multiple pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-6, IL-7, IL-12p70, IL-18, and MCP-1, and reduced secretion of IL-8, IL-21 and fractalkine, which were all secreted in doses of less than 2 ng/ml.

Figure 4.

Four-day IFNγ treatment alters cardiobundle cytokine secretion. Note that concentration of IFNγ is in ng/ml rather than pg/ml (n = 3 samples per group), reflecting the presence of exogenously added IFNγ. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 vs. 0 ng/ml IFNγ.

3.5. JAK inhibitors abolish both force decline and morphological deterioration induced by IFNγ

Since IFNγ and other pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g. IL-6) are shown to exert their effects via upregulation of JAK/STAT signaling pathway [53, 54], we have tested two clinically approved JAK inhibitors tofacitinib (Tofa) and baricitinib (Bari) in an attempt to prevent adverse effects of IFNγ on cardiobundle structure and function. The two inhibitors were applied at two different doses (50 nM and 500 nM) based on previously published human pharmacodynamics data [55, 56]. Application of Tofa alone, in the absence of IFNγ, did not result in contractile force changes; however, the drug attenuated IFNγ-induced contractile force decline at 50 nM and completely abolished it at 500 nM (Fig. 5A), without significant affecting contractile force kinetics (except for the effect of 50 nM Tofa on twitch relaxation time, Fig. 5A). Prevention of IFNγ-induced contractile force decline by tofacitinib was associated with the absence of myofibrillar disarray (Fig. 5B). Similar to Tofa, the application of Bari to cardiobundles prevented IFNγ-induced deficits in contractile function and tissue morphology without significantly altering structure and function of control tissues (Supp. Fig. 5). Taken together, inhibitors targeting JAK1 and JAK2 signaling were capable of blocking IFNγ-induced force decline and morphological deterioration in cardiomyocytes.

Figure 5.

Tofacitinib treatment of cardiobundles prevents contractile force decline and morphological deterioration induced by IFNγ. A) Quantified cardiobundle twitch force amplitude, contraction time, and relaxation time without treatment (Control) or after 7-day treatment with 20 ng/ml IFNγ, 50 nM or 500 nM Tofacitinib (Tofa), or both IFNγ and Tofa (n = 4–11 cardiobundles per group). B) Representative whole-tissue immunostains of cardiobundles treated with IFNγ with and without specified doses of Tofa. F-actin, filamentous actin; Cx43, connexin-43; DAPI, nuclei. Note that cardiomyocyte misalignment due to IFNγ is prevented in the presence of Tofa. **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 vs. control.

3.6. Effects of IFNγ on JAK/STAT signaling pathway

To gain further insights in the changes in JAK/STAT1 signaling in the presence of IFNγ and JAK inhibitors, we analyzed expression of total and phosphorylated STAT1 (p-STAT1) by immunoblotting (Fig. 6). IFNγ (20 ng/ml) treatment for 48 hr or 96 hr substantially increased levels of both STAT1 (20.2 ± 1.6 and 27.4 ± 1.2 fold, respectively) and p-STAT1 (4.5 ± 0.1 and 2.6 ± 0.2 fold, respectively), while co-application of tofacitinib (500 nM) reduced IFNγ-induced upregulation of p-STAT1 but not STAT1 at both time points (Fig. 6A&B). As JAK1 and JAK2 are known to act upstream of STAT1 upon IFNγ stimulation [57, 58], we also assessed the effect of IFNγ (48 hr exposure) on expression and activation of JAK1 and JAK2. IFNγ had no effect on JAK1 expression (Fig. 7A&B) but increased expression of p-JAK1 (Fig. 7A&C), while co-application of tofacitinib (500 nM) also had no effect on total JAK1 levels (Fig. 7A&B) but prevented IFNγ-induced p-JAK1 upregulation (Fig. 7A&C). IFNγ treatment significantly upregulated JAK2 and p-JAK2 expression (Fig. 7D–F), while co-treatment with tofacitinib did not affect IFNγ-induced JAK2 upregulation (Fig. 7D&E) but prevented the IFNγ-induced increase in p-JAK2 (Fig. 7D&F). Taken together, IFNγ induced JAK1, JAK2, and STAT1 activation, all of which were blunted by the co-treatment with tofacitinib.

Figure 6.

Tofacitinib treatment of cardiobundles prevents IFNγ-induced upregulation of STAT1 phosphorylation. A-B) Representative Western blots and corresponding quantifications of STAT1 and phosphorylated STAT1 (p-STAT1) expression 48 h (A) and 96 h (B) after treatment with IFNγ with or without Tofa normalized to GAPDH expression and shown relative to untreated (Control) group (n = 3 samples per group). **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 vs. control; $P < 0.01 and $P < 0.001 vs. IFNγ group.

Figure 7.

Tofacitinib treatment of cardiobundles prevents IFNγ-induced JAK1 and JAK2 phosphorylation. A-C) Representative Western blots (A) and corresponding quantifications of JAK1 (B) and phosphorylated JAK1 (p-JAK1, C) expression normalized to GAPDH expression and shown relative to untreated (Control) group (n = 6–9 samples per group). D-F) Representative Western blots (D) and corresponding quantifications of JAK2 (E) and phosphorylated JAK2 (p-JAK2, F) expression normalized to GAPDH expression and shown relative to untreated (Control) group (n = 6 samples per group). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 vs. control; $P < 0.05 vs. IFNγ group.

4. Discussion

Our studies show that in vitro exposure of human cardiomyocytes to IFNγ for 7 days induces a dose-dependent loss of contractile force generation and sarcomere organization without significantly changing cell viability, action potential propagation, or amplitude of electrically stimulated calcium transients. The observed myofibrillar disarray and force deficit were associated with changes in cardiomyocyte secretome and could be attributed to downregulated expression of several sarcomeric proteins, including myosin heavy chain (MHC), myosin light chain 2v (MLC-2v), and sarcomeric α-actinin (SAA). Mechanistically, these pro-inflammatory effects on engineered myocardium were mainly caused by IFNγ-induced upregulation of JAK/STAT signaling pathway since they could be fully prevented by co-application of FDA-approved JAK inhibitors used in anti-inflammatory treatment of rheumatoid arthritis [59] and recently COVID-19 [60].

Myocardial involvement in diseases with systemic inflammation, regardless of etiology, is common [3–10, 12, 13]. In patients with sepsis/septic shock, the prevalence of myocardial dysfunction can be as high as 75% and correlates with high death rates [6–9]. Elevation of circulating cytokine levels is a hallmark of systemic inflammation [61]. As a pro-inflammatory cytokine, IFNγ has elevated concentration in the blood not only in systemic inflammatory diseases [19, 20] and autoimmune diseases [18], but also in acute coronary syndrome [21, 22] and viral infections [23], including COVID-19. In a recent report, Arentz and colleagues [13] found that nearly one-third of COVID-19 patients admitted to an intensive care unit developed cardiomyopathy. In a previous study, 24–48h exposure of 2D-cultured neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVMs) to IFNγ-induced cell atrophy by selective, caspase activity-independent degradation of MHC [62]. In the present study, 7-day IFNγ treatment of 3D engineered human cardiac tissues was associated with loss of contractile force generation (Fig. 1) due to downregulation of multiple sarcomeric proteins, in addition to MHC (Fig. 3B). Similar to the findings in NRVMs, decreased protein abundance in cardiobundles appeared to be caused post-transcriptionally, contrasting the upregulated expression of corresponding sarcomeric genes (Fig. 3A) and suggesting the involvement of IFNγ-induced proteasomal degradation [62–64]. Elevated IFNγ could also lead to oxidative damage of newly synthesized proteins [65] to contribute to the observed protein loss. These results underscore the importance of examining the effects of pro-inflammatory cytokines in cardiomyocytes beyond the transcriptomic level.

In congenital and acquired cardiomyopathies, deficit in contractile function is frequently associated with cardiomyocyte loss, replacement fibrosis, and impaired action potential conduction leading to increased incidence of cardiac arrhythmias [66, 67]. In this study, we found no changes in the number of TUNEL+ cardiomyocytes (Fig. 2E) or the level of cleaved caspase-3 expression (Supp. Fig. 4), action potential conduction parameters (CV and APD, Supp. Fig. 2), or calcium transient amplitude (Fig. 1F&G), suggesting that IFNγ alone (at least after 7-day treatment) does not lead to arrhythmogenic changes in cardiac tissue, while the resulting loss of multiple sarcomeric proteins (Fig. 3B&C) is the major contributor to observed myofibrillar disarray and contractile deficit. In particular, with IFNγ exposure, any or all of the downregulated MHC, MLC-2v, or SAA proteins could result in the contractile force decline and abnormal sarcomere appearance (Supp. Fig. 3) [68]. Reductions in both MHC and MLC-2v expression would compromise the function of thick myofilaments. On the other hand, the SAA cross-links actin filaments in the Z-disk via its N-terminal actin binding domain, while its C-terminal calmodulin-like domain interacts with titin Z-repeats, the number of which determines the stability of Z-disk [69, 70]. IFNγ-induced decrease in SAA expression along with its very short half-life (25 sec) makes this protein a likely culprit for the observed loss of sarcomere organization.

Among seven types of STATs [71], IFNγ is known to affect only STAT1 [72] following the activation of JAK1 and JAK2 [73]. Although nearly all cell types in humans can respond to IFNγ [57, 58], the downstream signaling in human cardiomyocytes has not been fully characterized. In comparison to IFNγ-treated human epithelial cells and fibroblasts which showed prolonged upregulation of STAT1 but not p-STAT1 [74], cardiobundles in our study exhibited upregulation of both STAT1 and p-STAT1 for at least 96h (Fig. 6). As previously shown, increased STAT1 expression may broaden and prolong downstream changes in gene expression induced by IFNγ, independent of p-STAT1 [74]. Additionally, cardiobundles exposed to IFNγ showed upregulated expression of JAK2, but not JAK1, and increased phosphorylation of both JAK1 and JAK2, which could further induce non-canonical, STAT-independent changes in gene expression [75, 76]. The dominant role of JAK/STAT signaling in the adverse effects of IFNγ on human cardiobundles was confirmed by establishing robustly protective action of 500 nM tofacitinib (and baricitinib) that reduced phosphorylation of all of JAK1, JAK2, and STAT1 (Fig. 6&7).

While JAK/STAT pathway controls expression of the inducible proteasomal subunits and de novo synthesis of proteasomes [77], the exact link between upregulated JAK/STAT signaling and decreased expression of specific contractile proteins in cardiomyocytes remains to be studied. Nevertheless, the effectiveness of JAK inhibitors in our in vitro studies suggests their potential use for cardioprotection in the settings of acute and chronic inflammation, including systemic inflammatory response syndrome, sepsis, and allergic acute coronary syndrome, in addition to their current applications for the treatment of autoimmune diseases and myeloproliferative disorders. Moreover, understanding if JAK inhibition can revert an already induced inflammatory damage (along with its preventive effects explored in this study) merits future investigations. Importantly, as certain JAK inhibitors like baricitinib suppress coronavirus proliferation in addition to their anti-inflammatory effects [78] and the SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 appears to be an interferon-stimulated gene in human tissues [79] including the heart [80], the screening of JAK inhibitors for use in COVID-19 patients with myocardial involvement is warranted.

While it is possible that longer IFNγ exposure of cardiobundles could induce additional structural and electrophysiological remodeling characteristic of inflammatory cardiomyopathies, other pro-inflammatory cytokines or cell types present in vivo may be required to fully recapitulate the disease phenotypes observed in patients [81]. From our secretome analysis (Fig. 4), the IFNγ treatment increased or induced cardiobundle secretion of other pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-7, IL-12p70, IL-18, and MCP-1) whose potential roles in the observed structural and functional deficits remain to be studied. Additionally, given the critical roles of immune system cells in acute and chronic inflammation, incorporation of macrophages and T-cells within cardiobundles would enable more realistic studies of cardiac inflammatory responses. Improved structural and functional maturation of hiPSC-CMs would further increase relevance of the cardiobundle platform for human disease modeling.

In summary, 7-day application of IFNγ in human cardiobundles induced a dose-dependent decline in contractile force and myofibrillar organization, attributable to the loss of multiple sarcomeric proteins and upregulation of JAK/STAT signaling pathway. We expect that the future incorporation of various resident non-myocytes in cardiobundles, in conjunction with the application of select combinations of cytokines, will enable detailed mechanistic studies of human cardiac inflammatory disease and therapy.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Seven-day applications of interleukin-1α (IL-1α) or interleukin-6 (IL-6) do not alter cardiobundle contractile function. Quantified cardiobundle twitch force amplitude, contraction time, and relaxation time after 7-day application of IL-1α (top) or IL-6 (bottom) at specified doses (n = 5–6 cardiobundles per group).

Supplementary Figure 2. Seven-day application of IFNγ does not alter cardiobundle action potential propagation. A) Representative isochrone activation maps in cardiobundles treated with specified doses of IFNγ for 7 days. Cardiobundles were stimulated at 2 Hz rate (pulse sign) and induced action potential propagation was optically mapped. Color bar, time elapsed after the stimulus. Scale bar applies to all maps. B-C) Corresponding quantifications of conduction velocity (B) and action potential duration (APD) measured at 80% repolarization (C) (n = 4–6 cardiobundles per group).

Supplementary Figure 3. Representative transmission electron micrographs of untreated control cardiobundles (top row, 0 ng/ml) and cardiobundles treated with 20 ng/ml IFNγ for 7 days (bottom row). Note the decreased abundance and organization of sarcomeres in IFNγ-treated group.

Supplementary Figure 4. Application of IFNγ does not alter apoptotic events in cardiobundles. A-B) Representative cleaved caspase-3 (cCasp-3) staining images (A) and corresponding quantifications of percent imaged area positive for cCasp-3 (B) in cross-sections of cardiobundles treated with specified doses of IFNγ for 7 days. (n = 6–8 cardiobundles per group). SAA, sarcomeric α-actinin; DAPI, nuclei. C) Representative Western blots and corresponding quantifications of cCasp-3 expression in cardiobundles either not treated (Control, 0 ng/ml) or treated with 20 ng/ml of IFNγ for 48 hrs. cCasp-3 expression was normalized to that of GAPDH and shown relative to the control group (n = 6 cardiobundles per group).

Supplementary Figure 5. Baricitinib treatment of cardiobundles prevents contractile force decline and morphological deterioration induced by IFNγ. A) Quantified cardiobundle twitch force amplitude, contraction time, and relaxation time without treatment (Control) or after 7-day treatment with 20 ng/ml IFNγ, 50 nM or 500 nM Baricitinib (Bari), or both IFNγ and Bari (n = 4–6 cardiobundles per group). B) Representative whole-tissue immunostains of cardiobundles treated with IFNγ with and without specified doses of Bari. F-actin, filamentous actin; Cx43, connexin-43; DAPI, nuclei. Note that cardiomyocyte misalignment due to IFNγ is prevented in the presence of Bari. **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 vs. control.

Supplementary Table 1. Primary antibodies for immunofluorescence (IF) and Western blots

Significance statement.

Various inflammatory and autoimmune diseases including rheumatoid arthritis, sepsis, lupus erythematosus, Chagas disease, and others, as well as viral infections including H1N1 influenza and COVID-19 show increased systemic levels of a pro-inflammatory cytokine interferon-γ (IFNγ) and are associated with high risk of heart disease. Here we explored for the first time if chronically elevated levels of IFNγ can negatively affect structure and function of engineered human heart tissues in vitro. Our studies revealed IFNγ-induced deterioration of myofibrillar organization and contractile force production in human cardiomyocytes, attributed to decreased expression of multiple sarcomeric proteins and upregulation of JAK/STAT signaling pathway. FDA-approved JAK inhibitors fully blocked the adverse effects of IFNγ, suggesting a potentially effective strategy against human inflammatory cardiomyopathy.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by NIH grants UG3TR0002142 from the NIH Common Fund for the Microphysiological Systems Initiative and NIAMS and U01HL134764 from NIH-NHLBI.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Hotchkiss RS, Moldawer LL, Opal SM, Reinhart K, Turnbull IR, Vincent JL, Sepsis and septic shock, Nat Rev Dis Primers 2 (2016) 16045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].McInnes IB, Schett G, The pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis, N Engl J Med 365 (2011) 2205–2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kaplan MJ, Cardiovascular complications of rheumatoid arthritis: assessment, prevention, and treatment, Rheum Dis Clin North Am 36 (2010) 405–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Liao KP, Cardiovascular disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, Trends Cardiovasc Med 27 (2017) 136–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Mackey RH, Kuller LH, Moreland LW, Update on cardiovascular disease risk in patients with rheumatic diseases, Rheum Dis Clin North Am 44 (2018) 475–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Wijetunga M, Rockson S, Myocarditis in systemic lupus erythematosus, Am J Med 113 (2002) 419–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Parker MM, Shelhamer JH, Bacharach SL, Green MV, Natanson C, Frederick TM, Damske BA, Parrillo JE, Profound but reversible myocardial depression in patients with septic shock, Ann Intern Med 100 (1984) 483–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Romero-Bermejo FJ, Ruiz-Bailen M, Gil-Cebrian J, Huertos-Ranchal MJ, Sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy, Curr Cardiol Rev 7 (2011) 163–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Beesley SJ, Weber G, Sarge T, Nikravan S, Grissom CK, Lanspa MJ, Shahul S, Brown SM, Septic cardiomyopathy, Crit Care Med 46 (2018) 625–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Vallabhajosyula S, Pruthi S, Shah S, Wiley BM, Mankad SV, Jentzer JC, Basic and advanced echocardiographic evaluation of myocardial dysfunction in sepsis and septic shock, Anaesth Intensive Care 46 (2018) 13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Martin L, Derwall M, Al Zoubi S, Zechendorf E, Reuter DA, Thiemermann C, Schuerholz T, The septic heart: current understanding of molecular mechanisms and clinical implications, Chest 155 (2019) 427–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Barbandi M, Cordero-Reyes A, Orrego CM, Torre-Amione G, Seethamraju H, Estep J, A case series of reversible acute cardiomyopathy associated with H1N1 influenza infection, Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J 8 (2012) 42–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Arentz M, Yim E, Klaff L, Lokhandwala S, Riedo FX, Chong M, Lee M, Characteristics and outcomes of 21 critically ill patients with COVID-19 in Washington State, JAMA 323 (2020) 1612–1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Mateen S, Zafar A, Moin S, Khan AQ, Zubair S, Understanding the role of cytokines in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis, Clin Chim Acta 455 (2016) 161–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Boehm U, Klamp T, Groot M, Howard JC, Cellular responses to interferon-gamma, Annu Rev Immunol 15 (1997) 749–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Lauw FN, Simpson AJ, Prins JM, Smith MD, Kurimoto M, van Deventer SJ, Speelman P, Chaowagul W, White NJ, van der Poll T, Elevated plasma concentrations of interferon (IFN)-gamma and the IFN-gamma-inducing cytokines interleukin (IL)-18, IL-12, and IL-15 in severe melioidosis, J Infect Dis 180 (1999) 1878–1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Han JH, Suh CH, Jung JY, Ahn MH, Han MH, Kwon JE, Yim H, Kim HA, Elevated circulating levels of the interferon-gamma-induced chemokines are associated with disease activity and cutaneous manifestations in adult-onset Still’s disease, Scientific reports 7 (2017) 46652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Oke V, Gunnarsson I, Dorschner J, Eketjall S, Zickert A, Niewold TB, Svenungsson E, High levels of circulating interferons type I, type II and type III associate with distinct clinical features of active systemic lupus erythematosus, Arthritis Res Ther 21 (2019) 107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Calandra T, Baumgartner JD, Grau GE, Wu MM, Lambert PH, Schellekens J, Verhoef J, Glauser MP, Prognostic values of tumor necrosis factor/cachectin, interleukin-1, interferon-alpha, and interferon-gamma in the serum of patients with septic shock. Swiss-Dutch J5 Immunoglobulin Study Group, J Infect Dis 161 (1990) 982–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Bjerre A, Brusletto B, Hoiby EA, Kierulf P, Brandtzaeg P, Plasma interferon-gamma and interleukin-10 concentrations in systemic meningococcal disease compared with severe systemic Gram-positive septic shock, Crit Care Med 32 (2004) 433–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ranjbaran H, Sokol SI, Gallo A, Eid RE, Iakimov AO, D’Alessio A, Kapoor JR, Akhtar S, Howes CJ, Aslan M, Pfau S, Pober JS, Tellides G, An inflammatory pathway of IFN-gamma production in coronary atherosclerosis, J Immunol 178 (2007) 592–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Eid RE, Rao DA, Zhou J, Lo SF, Ranjbaran H, Gallo A, Sokol SI, Pfau S, Pober JS, Tellides G, Interleukin-17 and interferon-gamma are produced concomitantly by human coronary artery-infiltrating T cells and act synergistically on vascular smooth muscle cells, Circulation 119 (2009) 1424–1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Han H, Ma Q, Li C, Liu R, Zhao L, Wang W, Zhang P, Liu X, Gao G, Liu F, Jiang Y, Cheng X, Zhu C, Xia Y, Profiling serum cytokines in COVID-19 patients reveals IL-6 and IL-10 are disease severity predictors, Emerg Microbes Infect 9 (2020) 1123–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Levick SP, Goldspink PH, Could interferon-gamma be a therapeutic target for treating heart failure?, Heart failure reviews 19(2) (2014) 227–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Reifenberg K, Lehr HA, Torzewski M, Steige G, Wiese E, Kupper I, Becker C, Ott S, Nusser P, Yamamura K, Rechtsteiner G, Warger T, Pautz A, Kleinert H, Schmidt A, Pieske B, Wenzel P, Munzel T, Lohler J, Interferon-gamma induces chronic active myocarditis and cardiomyopathy in transgenic mice, Am J Pathol 171 (2007) 463–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Jin H, Li W, Yang R, Ogasawara A, Lu H, Paoni NF, Inhibitory effects of interferon-gamma on myocardial hypertrophy, Cytokine 31 (2005) 405–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Garcia AG, Wilson RM, Heo J, Murthy NR, Baid S, Ouchi N, Sam F, Interferon-gamma ablation exacerbates myocardial hypertrophy in diastolic heart failure, Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 303 (2012) H587–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kimura A, Ishida Y, Furuta M, Nosaka M, Kuninaka Y, Taruya A, Mukaida N, Kondo T, Protective roles of interferon-gamma in cardiac hypertrophy induced by sustained pressure overload, J Am Heart Assoc 7 (2018) e008145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Morino Y, Hara K, Ushikoshi H, Tanabe K, Kuroda Y, Noguchi T, Ayabe S, Hara H, Yanbe Y, Kozuma K, Ikari Y, Saeki F, Tamura T, Gamma-interferon-induced cardiomyopathy during treatment of renal cell carcinoma: a case report, J Cardiol 36 (2000) 49–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Mera S, Tatulescu D, Cismaru C, Bondor C, Slavcovici A, Zanc V, Carstina D, Oltean M, Multiplex cytokine profiling in patients with sepsis, APMIS 119 (2011) 155–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Gomes JA, Bahia-Oliveira LM, Rocha MO, Martins-Filho OA, Gazzinelli G, Correa-Oliveira R, Evidence that development of severe cardiomyopathy in human Chagas’ disease is due to a Th1-specific immune response, Infect Immun 71(3) (2003) 1185–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Pinto AR, Ilinykh A, Ivey MJ, Kuwabara JT, D’Antoni ML, Debuque R, Chandran A, Wang L, Arora K, Rosenthal NA, Tallquist MD, Revisiting cardiac cellular composition, Circ Res 118 (2016) 400–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Lian X, Zhang J, Azarin SM, Zhu K, Hazeltine LB, Bao X, Hsiao C, Kamp TJ, Palecek SP, Directed cardiomyocyte differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells by modulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling under fully defined conditions, Nat Protoc 8 (2013) 162–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Zhang D, Shadrin IY, Lam J, Xian HQ, Snodgrass HR, Bursac N, Tissue-engineered cardiac patch for advanced functional maturation of human ESC-derived cardiomyocytes, Biomaterials 34(23) (2013) 5813–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Shadrin IY, Allen BW, Qian Y, Jackman CP, Carlson AL, Juhas ME, Bursac N, Cardiopatch platform enables maturation and scale-up of human pluripotent stem cell-derived engineered heart tissues, Nat Commun 8 (2017) 1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Jackman CP, Carlson AL, Bursac N, Dynamic culture yields engineered myocardium with near-adult functional output, Biomaterials 111 (2016) 66–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Bassat E, Mutlak YE, Genzelinakh A, Shadrin IY, Baruch Umansky K, Yifa O, Kain D, Rajchman D, Leach J, Riabov Bassat D, Udi Y, Sarig R, Sagi I, Martin JF, Bursac N, Cohen S, Tzahor E, The extracellular matrix protein agrin promotes heart regeneration in mice, Nature 547 (2017) 179–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Tohyama S, Hattori F, Sano M, Hishiki T, Nagahata Y, Matsuura T, Hashimoto H, Suzuki T, Yamashita H, Satoh Y, Egashira T, Seki T, Muraoka N, Yamakawa H, Ohgino Y, Tanaka T, Yoichi M, Yuasa S, Murata M, Suematsu M, Fukuda K, Distinct Metabolic Flow Enables Large-Scale Purification of Mouse and Human Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes, Cell stem cell 12(1) (2013) 127–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Palmer JN, Hartogensis WE, Patten M, Fortuin FD, Long CS, Interleukin-1 beta induces cardiac myocyte growth but inhibits cardiac fibroblast proliferation in culture, J Clin Invest 95 (1995) 2555–2564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Fredj S, Bescond J, Louault C, Delwail A, Lecron J-C, Potreau D, Role of interleukin-6 in cardiomyocyte/cardiac fibroblast interactions during myocyte hypertrophy and fibroblast proliferation, J Cell Physiol 204 (2005) 428–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Bassat E, Mutlak YE, Genzelinakh A, Shadrin IY, Baruch Umansky K, Yifa O, Kain D, Rajchman D, Leach J, Riabov Bassat D, Udi Y, Sarig R, Sagi I, Martin JF, Bursac N, Cohen S, Tzahor E, The extracellular matrix protein agrin promotes heart regeneration in mice, Nature 547(7662) (2017) 179–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Jackman C, Li H, Bursac N, Long-term contractile activity and thyroid hormone supplementation produce engineered rat myocardium with adult-like structure and function, Acta Biomater 78 (2018) 98–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Jackman CP, Ganapathi AM, Asfour H, Qian Y, Allen BW, Li Y, Bursac N, Engineered cardiac tissue patch maintains structural and electrical properties after epicardial implantation, Biomaterials 159 (2018) 48–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Li Y, Song D, Mao L, Abraham DM, Bursac N, Lack of Thy1 defines a pathogenic fraction of cardiac fibroblasts in heart failure, Biomaterials 236 (2020) 119824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Juhas M, Abutaleb N, Wang JT, Ye J, Shaikh Z, Sriworarat C, Qian Y, Bursac N, Incorporation of macrophages into engineered skeletal muscle enables enhanced muscle regeneration, Nat Biomed Eng 2(12) (2018) 942–954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Pedrotty DM, Klinger RY, Kirkton RD, Bursac N, Cardiac fibroblast paracrine factors alter impulse conduction and ion channel expression of neonatal rat cardiomyocytes, Cardiovasc Res 83(4) (2009) 688–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Khodabukus A, Madden L, Prabhu NK, Koves TR, Jackman CP, Muoio DM, Bursac N, Electrical stimulation increases hypertrophy and metabolic flux in tissue-engineered human skeletal muscle, Biomaterials 198 (2019) 259–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Charriaut-Marlangue C, Ben-Ari Y, A cautionary note on the use of the TUNEL stain to determine apoptosis, Neuroreport 7 (1995) 61–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Grasl-Kraupp B, Ruttkay-Nedecky B, Koudelka H, Bukowska K, Bursch W, Schulte-Hermann R, In situ detection of fragmented DNA (TUNEL assay) fails to discriminate among apoptosis, necrosis, and autolytic cell death: a cautionary note, Hepatology 21 (1995) 1465–1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Nagaraju K, Raben N, Merritt G, Loeffler L, Kirk K, Plotz P, A variety of cytokines and immunologically relevant surface molecules are expressed by normal human skeletal muscle cells under proinflammatory stimuli, Clin Exp Immunol 113 (1998) 407–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Hu X, Ivashkiv LB, Cross-regulation of signaling pathways by interferon-gamma: implications for immune responses and autoimmune diseases, Immunity 31 (2009) 539–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Zha Z, Bucher F, Nejatfard A, Zheng T, Zhang H, Yea K, Lerner RA, Interferon-γ is a master checkpoint regulator of cytokine-induced differentiation, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114 (2017) E6867–E6874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Horvath CM, The Jak-STAT pathway stimulated by interferon gamma, Sci STKE 2004 (2004) tr8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Morris R, Kershaw NJ, Babon JJ, The molecular details of cytokine signaling via the JAK/STAT pathway, Protein Sci 27 (2018) 1984–2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Dowty ME, Jesson MI, Ghosh S, Lee J, Meyer DM, Krishnaswami S, Kishore N, Preclinical to clinical translation of tofacitinib, a Janus kinase inhibitor, in rheumatoid arthritis, J Pharmacol Exp Ther 348 (2014) 165–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Shi JG, Chen X, Lee F, Emm T, Scherle PA, Lo Y, Punwani N, Williams WV, Yeleswaram S, The pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and safety of baricitinib, an oral JAK 1/2 inhibitor, in healthy volunteers, J Clin Pharmacol 54 (2014) 1354–1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Schindler C, Shuai K, Prezioso VR, Darnell JE Jr., Interferon-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of a latent cytoplasmic transcription factor, Science 257 (1992) 809–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Green DS, Young HA, Valencia JC, Current prospects of type II interferon gamma signaling and autoimmunity, J Biol Chem 292 (2017) 13925–13933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Lee YH, Song GG, Comparative efficacy and safety of tofacitinib, baricitinib, upadacitinib, filgotinib and peficitinib as monotherapy for active rheumatoid arthritis, J Clin Pharm Ther 45 (2020) 674–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Luo W, Li YX, Jiang LJ, Chen Q, Wang TY, Ye DW, Targeting JAK-STAT signaling to control cytokine release syndrome in COVID-19, Trends Pharmacol Sci 41 (2020) 531–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Kany S, Vollrath JT, Relja B, Cytokines in inflammatory disease, Int J Mol Sci 20 (2019) 6008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Cosper PF, Harvey PA, Leinwand LA, Interferon-gamma causes cardiac myocyte atrophy via selective degradation of myosin heavy chain in a model of chronic myocarditis, Am J Pathol 181 (2012) 2038–2346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Tanahashi N, Murakami Y, Minami Y, Shimbara N, Hendil KB, Tanaka K, Hybrid proteasomes. Induction by interferon‐gamma and contribution to ATP‐dependent proteolysis, J Biol Chem 275 (2000) 14336–14345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Cascio P, Call M, Petre BM, Walz T, Goldberg AL, Properties of the hybrid form of the 26S proteasome containing both 19S and PA28 complexes, EMBO J 21 (2002) 2636–2645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Seifert U, Bialy LP, Ebstein F, Bech-Otschir D, Voigt A, Schröter F, Prozorovski T, Lange N, Steffen J, Rieger M, Kuckelkorn U. Aktas, Kloetzel P-MO, Krüger E, Immunoproteasomes preserve protein homeostasis upon interferon-induced oxidative stress, Cell 142 (2010) 613–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Yalta T, Yalta K, Systemic inflammation and arrhythmogenesis: A review of mechanistic and clinical perspectives, Angiology 69 (2018) 288–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Lazzerini PE, Capecchi PL, Laghi-Pasini F, Systemic inflammation and arrhythmic risk: lessons from rheumatoid arthritis, Eur Heart J 38 (2017) 1717–1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Tucholski T, Cai W, Gregorich ZR, Bayne EF, Mitchell SD, McIlwain SJ, de Lange WJ, Wrobbel M, Karp H, Hite Z, Vikhorev PG, Marston SB, Lal S, Li A, dos Remedios C, Kohmoto T, Hermsen J, Ralphe JC, Kamp TJ, Moss RL, Ge Y, Distinct hypertrophic cardiomyopathy genotypes result in convergent sarcomeric proteoform profiles revealed by top-down proteomics, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 117 (2020) 24691–24700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Gautel M, Djinovic-Carugo K, The sarcomeric cytoskeleton: from molecules to motion, J Exp Biol 219 (2016) 135–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Grison M, Merkel U, Kostan J, Djinovic-Carugo K, Rief M, alpha-Actinin/titin interaction: A dynamic and mechanically stable cluster of bonds in the muscle Z-disk, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114 (2017) 1015–1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Noon-Song EN, Ahmed CM, Dabelic R, Canton J, Johnson HM, Controlling nuclear JAKs and STATs for specific gene activation by IFNgamma, Biochem Biophys Res Commun 410 (2011) 648–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Shuai K, Schindler C, Prezioso VR, Darnell JE Jr., Activation of transcription by IFN-gamma: tyrosine phosphorylation of a 91-kD DNA binding protein, Science 258 (1992) 1808–1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Kotenko SV, Pestka S, Jak-Stat signal transduction pathway through the eyes of cytokine class II receptor complexes, Oncogene 19 (2000) 2557–2565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Cheon H, Stark GR, Unphosphorylated STAT1 prolongs the expression of interferon-induced immune regulatory genes, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106(23) (2009) 9373–9378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Zouein FA, Duhé RJ, Booz GW, JAKs go nuclear: emerging role of nuclear JAK1 and JAK2 in gene expression and cell growth, Growth Factors 29 (2011) 245–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Tsurumi A, Zhao C, Li WX, Canonical and non-canonical JAK/STAT transcriptional targets may be involved in distinct and overlapping cellular processes, BMC Genomics 18 (2017) 718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Hohn TJ, Grune T, The proteasome and the degradation of oxidized proteins: part III-Redox regulation of the proteasomal system, Redox Biol 2 (2014) 388–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Stebbing J, Krishnan V, de Bono S, Ottaviani S, Casalini G, Richardson PJ, Monteil V, Lauschke VM, Mirazimi A, Youhanna S, Tan YJ, Baldanti F, Sarasini A, Terres JAR, Nickoloff BJ, Higgs RE, Rocha G, Byers NL, Schlichting DE, Nirula A, Cardoso A, Corbellino M, Sacco Baricitinib Study G, Mechanism of baricitinib supports artificial intelligence-predicted testing in COVID-19 patients, EMBO Mol Med 12 (2020) e12697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Ziegler CGK, Allon SJ, Nyquist SK, Mbano IM, Miao VN, Tzouanas CN, Cao Y, Yousif AS, Bals J, Hauser BM, et al. , SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 is an interferon-stimulated gene in human airway epithelial cells and is detected in specific cell subsets across tissues, Cell 181 (2020) 1016–1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Liu H, Gai S, Wang X, Zeng J, Sun C, Zhao Y, Zheng Z, Single-cell analysis of SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 and spike protein priming expression of proteases in the human heart, Cardiovasc Res 116 (2020) 1733–1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Hanna A, Frangogiannis NG, Inflammatory cytokines and chemokines as therapeutic targets in heart failure, Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 34 (2020) 849–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Seven-day applications of interleukin-1α (IL-1α) or interleukin-6 (IL-6) do not alter cardiobundle contractile function. Quantified cardiobundle twitch force amplitude, contraction time, and relaxation time after 7-day application of IL-1α (top) or IL-6 (bottom) at specified doses (n = 5–6 cardiobundles per group).

Supplementary Figure 2. Seven-day application of IFNγ does not alter cardiobundle action potential propagation. A) Representative isochrone activation maps in cardiobundles treated with specified doses of IFNγ for 7 days. Cardiobundles were stimulated at 2 Hz rate (pulse sign) and induced action potential propagation was optically mapped. Color bar, time elapsed after the stimulus. Scale bar applies to all maps. B-C) Corresponding quantifications of conduction velocity (B) and action potential duration (APD) measured at 80% repolarization (C) (n = 4–6 cardiobundles per group).

Supplementary Figure 3. Representative transmission electron micrographs of untreated control cardiobundles (top row, 0 ng/ml) and cardiobundles treated with 20 ng/ml IFNγ for 7 days (bottom row). Note the decreased abundance and organization of sarcomeres in IFNγ-treated group.

Supplementary Figure 4. Application of IFNγ does not alter apoptotic events in cardiobundles. A-B) Representative cleaved caspase-3 (cCasp-3) staining images (A) and corresponding quantifications of percent imaged area positive for cCasp-3 (B) in cross-sections of cardiobundles treated with specified doses of IFNγ for 7 days. (n = 6–8 cardiobundles per group). SAA, sarcomeric α-actinin; DAPI, nuclei. C) Representative Western blots and corresponding quantifications of cCasp-3 expression in cardiobundles either not treated (Control, 0 ng/ml) or treated with 20 ng/ml of IFNγ for 48 hrs. cCasp-3 expression was normalized to that of GAPDH and shown relative to the control group (n = 6 cardiobundles per group).

Supplementary Figure 5. Baricitinib treatment of cardiobundles prevents contractile force decline and morphological deterioration induced by IFNγ. A) Quantified cardiobundle twitch force amplitude, contraction time, and relaxation time without treatment (Control) or after 7-day treatment with 20 ng/ml IFNγ, 50 nM or 500 nM Baricitinib (Bari), or both IFNγ and Bari (n = 4–6 cardiobundles per group). B) Representative whole-tissue immunostains of cardiobundles treated with IFNγ with and without specified doses of Bari. F-actin, filamentous actin; Cx43, connexin-43; DAPI, nuclei. Note that cardiomyocyte misalignment due to IFNγ is prevented in the presence of Bari. **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 vs. control.

Supplementary Table 1. Primary antibodies for immunofluorescence (IF) and Western blots