Abstract

Context.

The International Association for Hospice and Palliative Care developed a consensus-based definition of palliative care (PC) that focuses on the relief of serious health-related suffering, a concept put forward by the Lancet Commission Global Access to Palliative Care and Pain Relief.

Objective.

The main objective of this article is to present the research behind the new definition.

Methods.

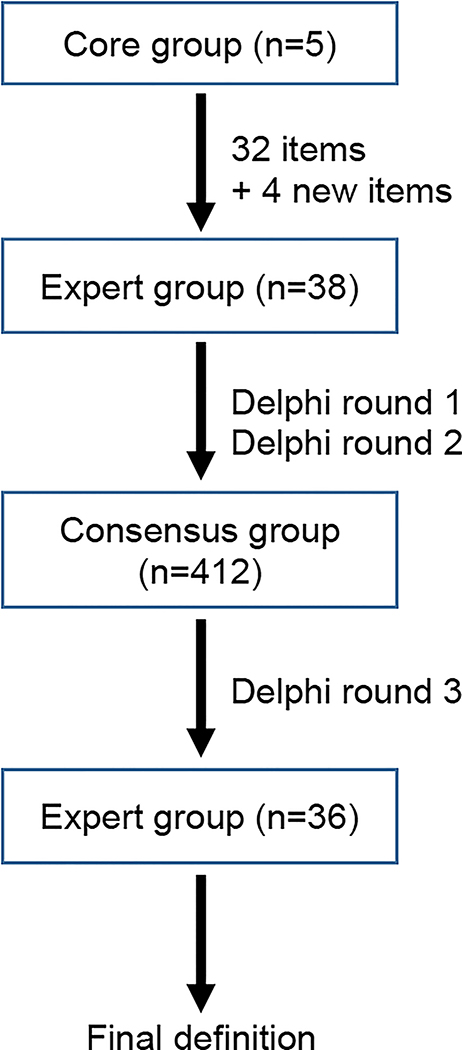

The three-phased consensus process involved health care workers from countries in all income levels. In Phase 1, 38 PC experts evaluated the components of the World Health Organization definition and suggested new/revised ones. In Phase 2, 412 International Association for Hospice and Palliative Care members in 88 countries expressed their level of agreement with the suggested components. In Phase 3, using results from Phase 2, the expert panel developed the definition.

Results.

The consensus-based definition is as follows: Palliative care is the active holistic care of individuals across all ages with serious health-related suffering due to severe illness and especially of those near the end of life. It aims to improve the quality of life of patients, their families and their caregivers. The definition includes a number of bullet points with additional details as well as recommendations for governments to reduce barriers to PC.

Conclusion.

Participants had significantly different perceptions and interpretations of PC. The greatest challenge faced by the core group was trying to find a middle ground between those who think that PC is the relief of all suffering and those who believe that PC describes the care of those with a very limited remaining life span.

Keywords: Definition of palliative care, consensus, Delphi method, quality of life, relief of suffering, low or middle income countries

Introduction

Access to palliative care (PC)—an essential component of health care and integral to Universal Health Coverage1,2—is still grossly inadequate or nonexistent in most parts of the world.3 The Lancet Commission on Global Access to Palliative Care and Pain Relief (hereafter referred to as The Lancet Commission) estimated that annually, more than 61 million people experience health conditions associated with suffering that could be significantly ameliorated through PC. At least 80% lack access to even the most basic PC interventions, such as pain medication.4

Appropriately defining and delimiting the nature and scope of PC is key for integration into the care continuum, to identifying the human, financial and physical resources required to meet global need, and to close the enormous inequitable divides in access. Yet, as clinical science and capacity to deliver health care have evolved, the debates around the definition of PC have become more intense and complex.5

PC initially and historically focused on alleviating the relief of suffering at the end of life. However, it is now considered best practice6 and is increasingly implemented earlier in the trajectory of life-threatening health conditions. Furthermore, the historical development of PC was focused largely on patients with cancer, whereas it is now being integrated into treatment of all life-threatening health conditions. Existing research suggests that PC is both effective in reducing symptom burden and improving quality of life, cost effective, and synonymous with quality of care.7,8

A consensus on the definition is required for conceptual clarity in PC, which in turn impacts on scope of practice, therapeutic aims, and outcome assessment. Lack of conceptual clarity may hamper the efforts of countries, especially those of low income and middle income, to implement PC and thus to achieve universal health care.

The Lancet Commission identified the need to review and revise the definition of PC. As part of its agreement of work as a nongovernmental organization in official relations with the World Health Organization (WHO), the International Association for Hospice and Palliative Care (IAHPC) took on this task.

The objective of this article is to present the research behind the new definition. We developed a consensus-based definition of PC that focuses on the relief of serious health-related suffering (SHS), a concept put forward by the Lancet Commission, that is, timely and is applicable to all patients regardless of diagnosis, prognosis, geographic location, point of care, or socioeconomic level. This article describes the process undertaken by IAHPC, the findings of the consensus-building exercises, and presents the resulting definition and recommendations.

Definitions, Terminology, and Scope of PC

In 1990, WHO published a definition of PC,9 and in 1998, a specific one for children.10 The WHO definition was revised in 2002 (Table 1).11 This definition expanded the scope of PC considerably and placed a much-needed focus on a public health approach. However, there has also been criticism of this definition. It limits PC to problems associated with life-threatening illnesses, rather than the burdensome experience of patients with severe and frequently multiple chronic conditions. The range and severity of potential PC needs may be more relevant indicators of need for these patients than prognosis alone.12

Table 1.

PC—Definition of the WHO11

| PC is an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problem associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial, and spiritual. |

| PC: |

| • Provides relief from pain and other distressing symptoms; |

| • Affirms life and regards dying as a normal process; |

| • Intends neither to hasten or postpone death; |

| • Integrates the psychological and spiritual aspects of patient care; |

| • Offers a support system to help patients live as actively as possible until death; |

| • Offers a support system to help the family cope during the patient’s illness and in their own bereavement; |

| • Uses a team approach to address the needs of patients and their families, including bereavement counseling, if indicated; |

| • Will enhance quality of life and may also positively influence the course of illness; |

| • Is applicable early in the course of illness, in conjunction with other therapies that are intended to prolong life, such as chemotherapy or radiation therapy, and includes those investigations needed to better understand and manage distressing clinical complications |

PC = palliative care; WHO = World Health Organization.

Some PC specialists have expressed doubts as to the meaning of impeccable as well as to whether this is a valid marker for assessment and treatment. Other areas of the definition of PC that require clarification are that it can be provided wherever the patient’s other care takes place, is needed for chronic and terminal illness, and can be adapted in different geopolitical, cultural, and economic settings.13 More recently, other changes in the concept of PC have been discussed, including different models of care provision and organization of care.5,14

Some organizations, such as the African Palliative Care Association and the Asian Pacific Hospice Palliative Care Network, have adopted the WHO definition, whereas others have adopted their own definitions of PC.15–20 The International Children’s Palliative Care Network has a dedicated section in its Web site that presents the various definitions used for children’s PC.21

A review of the different definitions revealed variance in how (as a medical specialty or as a general approach) and when (end of life or early integration) PC is implemented within the care continuum.22 Integrating PC early in the course of illness may both improve symptom control and quality of life, and early integration into treatment protocols for both adults and children has been advocated.23,24 This is particularly important for diseases other than cancer, for example, HIV and multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Sub-Saharan Africa,25 where sufficient evidence exists to support provision of PC based on need rather than on prognosis or disease stage. PC is now also being considered an important component in responding to acute epidemics26 and humanitarian emergencies.27

Despite of these differences, there seems to be a common understanding and discourse. An analysis of 37 English and 26 German definitions identified the prevention and relief of suffering and improvement of quality of life as common shared goals of PC.22

In 2017, the Lancet Commission presented a framework to measure the global burden of SHS as a metric of PC need.4 Suffering is defined as health related when it is associated with illness or injury of any kind. Health-related suffering is serious when it cannot be relieved without professional intervention and when it compromises physical, social, spiritual, and/or emotional functioning. The estimation of SHS includes the 20 health conditions or illness groups that are most likely to generate a need for PC.4,14 This new approach resulted in an even broader conceptualization of the scope of PC. The Lancet Commission recommended that the WHO definition be reviewed and revised to better encompass all levels of the health care system and varying socioeconomic conditions, especially in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) where medical professionals often have the difficult task of caring for patients with severely limited access to necessary medicines, equipment, or training.

Methodology

A three-phased consensus process was designed in accordance with the Conducting and REporting DElphi Studies guideline for PC (Fig. 1).28 Some additional information on the consensus process, for example, the names of the participants in Phases 1, 2, and 3, are available online.14

Fig. 1.

Flowchart for consensus process.

Phase 1

In March 2018, the IAHPC formed a core group of PC experts and WHO representatives (Lukas Radbruch, Roberto Wenk, Gilles Forte, Marie-Charlotte Bousseau, and Liliana De Lima). Tania Pastrana served as research adviser. All materials such as survey questionnaires used in the three phases were piloted by the core group.

The core group identified 38 experts, who all agreed to participate in the expert group.14 The experts were regionally and professional diverse and located in countries in all income levels (Table 2). Board members of international PC organizations were included, as well as PC leaders specialized in pediatrics, geriatrics, research, spiritual care, primary care, pharmacy, and health economics. Given that one of the tasks of the members of this group was to revise and approve the project proposal and the proposed methodology, in this phase, we included only persons with strong clinical and research background.

Table 2.

Members of the Expert Group

| Name | Profession | Residence | Country’s Income Levela |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Bee Wee | Physician and researcher; head of palliative care research and development, Sir Michael Sobell House in Oxford | U.K. | High |

| 2. Carlos Centeno | Physician and researcher—education in PC. ATLANTES Professor Palliative Care Universidad de Navarra | Spain | High |

| 3. Charmaine Blanchard | Physician—PC; senior lecturer and researcher, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg | South Africa | Upper middle |

| 4. Chitra Venkateswaran | Physician—mental health and PC; founder and clinical director MEHAC Foundation | India | Lower middle |

| 5. Christina Puchalski | Physician—spiritual care; director, GWish | U.S. | High |

| 6. Claudia Burla | Physician—geriatrician; secretary of the board, International Association of Gerontologists | Brazil | Upper middle |

| 7. Cynthia Goh | Physician—chairperson of the Asia Pacific Hospice and Palliative Care Network | Singapore | High |

| 8. Dingle Spence | Physician—PC; regional leader, president Caribbean Palliative Care Association | Jamaica | Upper middle |

| 9. Eduardo Bruera | Physician—PC in cancer; researcher; PC chair, MD Anderson Cancer Center | U.S. | High |

| 10. Emmanuel Luyirika | Physician—regional leader; executive director; APCA | Uganda | Low |

| 11. Esther Cege Munyoro | Physician—PC; coordinator, PC unit, Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi | Kenya | Lower middle |

| 12. Hibah Osman | Physician—PC; executive and medical director, Balsam Center, Beirut | Lebanon | Upper middle |

| 13. Jim Cleary | Physician—PC in cancer; researcher; director WHO Collaborating Center in PPSG | U.S. | High |

| 14. Jinsun Yong | Nurse—education in PC; director WHO Collaborating Center for Training in Hospice & Palliative Care | Republic of Korea | High |

| 15. Joan Marston | Nurse—PALCHASE | South Africa | Upper middle |

| 16. John Beard | Physician—epidemiology—Healthy Aging WHO | Switzerland | High |

| 17. Julia Downing | Nurse—professor PC; Makerere—ICPCN | Uganda | Low |

| 18. Katherine Pettus | Political science—advocacy international legal frameworks, access to medicines for PC; advocacy officer IAHPC | U.S. | High |

| 19. Kathy Foley | Physician—PC specialist; adviser to IAHPC | U.S. | High |

| 20. Liliana De Lima | Psychologist, HC administrator, executive director IAHPC | U.S./Colombia | High |

| 21. Lukas Radbruch | Physician—professor PC, University Bonn, Chair IAHPC | Germany | High |

| 22. M. R. Rajagopal | Physician—PC advocate, Chair Pallium India | India | Lower middle |

| 23. Mary Callaway | Administrator—Board member IAHPC and APCA | U.S. | High |

| 24. Mhoira Leng | Physician—PC development, education; lead for PC Makerere University; and Cairdeas International Palliative Care Trust | Uganda | Low |

| 25. Odette Spruitt | Physician—PC; associate professor, Peter MacCallum Cancer Center, Australasian Palliative Link International | Australia | High |

| 26. Odontuya Davaasuren | Physician—professor PC; Mongolian Palliative Care Society | Mongolia | Lower middle |

| 27. Phillippe Larkin | Nurse, researcherdPresident of EAPC | Ireland | High |

| 28. Quach T. Khanh | Physician—Ho Chi Minh City Hospital—director palliative care unit | Vietnam | Lower middle |

| 29. Richard Harding | Sociologist, researcher—Director of the Center for Global Health Palliative Care Kings College, London | U.K. | High |

| 30. Roberto Wenk | Physician—PC director—National Palliative Care program FEMEBA | Argentina | Upper middle |

| 31. Roger Woodruff | Physician—founder IAHPC; retired professor PC | Australia | High |

| 32. Rosa Buitrago | Pharmacist—dean, School of Pharmacy, University of Panama | Panama | High |

| 33. Sebastiane Moine | Physician—primary PC IPPCN | France | High |

| 34. Stephen Connor | Psychologist, administrator, and researcher, ED WHPCA | U.S. | High |

| 35. Sushma Bhatnaghar | Physician—professor PC, AIIMS Institute, New Delhi, India | India | Lower middle |

| 36. Tania Pastrana | Physician, sociologist, and researcher—Aachen University; president, Latin American Association for Palliative Care | Germany/Colombia | High |

| 37. Wendy Gomez-Garcia | Pediatric oncology—Global Pediatric Medicine Collaborator for Haiti & Dominican Republic, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital | Dominican Republic | Upper middle |

| 38. Zipporah Ali | Physician—executive director, KEHPCA | Uganda | Low |

PC = palliative care; MEHAC = Mental Health Care and Research Foundation; GWish = The George Washington University Institute for Spirituality and Health; APCA = African Palliative Care Association; WHO = World Health Organization; PPSG = Policy and Pain Studies Group; PURCHASE = Palliative Care in Humanitarian Aid Situations and Emergencies network; ICPCN = International Children’s Palliative Care Network; EAPC = European Association for Palliative, Care; FEMEBA = Federación Médica de la Provincia de Buenos Aires; IPPCN = International Primary Palliative Care Network; ED = emergency department; WHPCA = Worldwide Hospice Palliative Care Alliance; KEHPCA = Kenya Hospices and Palliative Care Association.

Per the World Bank Classification

The WHO definition of PC was broken down into its main components resulting in 32 items. Using an online survey tool (SurveyMonkey©, Survey Monkey [Corp.], San Mateo, CA), these components were presented to members of the expert group in a first round of a Delphi consensus procedure. The survey also included four additional components considered by the core group to be absent from the WHO definition. For each component, participants were asked to select one of four options (stay as is; revise; delete; and do not know/not sure) and were given the opportunity to edit and suggest language.

In a second Delphi round, participants were provided with anonymized results from the first round and were given the opportunity to change or modify their initial response. After the second round of Delphi, components receiving approval of 70% or more were left as they were. Other components were revised based on the suggestions of the participants.

Phase 2

Participants in this phase were recruited from among the 1025 members registered with the IAHPC as of April 2018. Excluding undergraduates, 1014 members were eligible for the survey. The IAHPC members were stratified by their respective countries’ socioeconomic level according to the World Bank classification (high income, upper middle, lower middle, and low income).29 From each country income-level group, 150 members were randomly selected. The selected members received an electronic mail invitation between June and July 2018 to participate in the survey. The IAHPC members who responded to the invitation received a link to an online survey.

Participants were assured of confidentiality and privacy. The respondents’ data from the survey were stored in a SurveyMonkey password-protected account.

Participants were asked to rank their agreement with each component that was approved or revised in Phase 1 using a Likert scale (completely disagree, mostly disagree, neither agree nor disagree, mostly agree, completely agree, and do not know). They could also provide additional comments in free-text fields.

Consensus was defined a priori as ≥70% of answers scoring 5 (strongly agree) or 4 (agree), and the mean score >4 on the Likert scale.

Phase 3

Based on the components reaching consensus in Phase 2, a definition was drafted and sent to the members of the expert group. In this final phase, each member was given the opportunity to comment and suggest changes to the proposed definition.

Results

In Phase 1, all invited members of the expert group participated in the survey. After two rounds of Delphi, consensus was reached for 16 components of the WHO definition to remain and for one component (problems associated with life-threatening illness) to be revised (Table 3). In this phase, some comments expressed dislike for the term approach and the adjective impeccable applied to assessment and treatment, in the WHO definition. The group agreed not to delete any component.

Table 3.

Components of the WHO 2002 PC Definition as Rated by Members of the Expert Group (N = 38) Phase 1 (Percentages)

| Component | Stays As Is | Needs Revision | Delete |

|---|---|---|---|

| Approach | 47.2 | 52.8 | 0 |

| Improves the quality of life | 77.8 | 22.2 | 0 |

| Patients and their families | 70.1 | 29.9 | 0 |

| Problems associated with life-threatening illness | 27.8 | 72.2 | 0 |

| Prevention and relief of suffering | 70.1 | 29.92 | 0 |

| Early identification of pain | 75 | 16.7 | 8.3 |

| Impeccable assessment of pain | 33.3 | 61.1 | 5.6 |

| Treatment of pain | 66.7 | 25 | 8.3 |

| Early identification of physical problems | 66.7 | 22.2 | 11.1 |

| Impeccable assessment of physical problems | 33.3 | 61.1 | 5.6 |

| Treatment of physical problems | 52.8 | 36.1 | 11.1 |

| Early identification of psychosocial problems | 50 | 36.1 | 13.9 |

| Impeccable assessment of psychosocial problems | 30.6 | 58.3 | 11.1 |

| Treatment of psychosocial problems | 38.9 | 50 | 11.1 |

| Early identification of spiritual problems | 58.3 | 27.8 | 13.9 |

| Impeccable assessment of spiritual problems | 30.6 | 55.6 | 13.8 |

| Treatment of spiritual problems | 30.6 | 52.8 | 16.6 |

| Provides relief from pain | 80.6 | 11.1 | 8.3 |

| Provides relief from other distressing symptoms | 77.8 | 13.9 | 8.3 |

| Affirms life and regards dying as a normal process | 75 | 19.4 | 5.6 |

| Intends neither to hasten or postpone death | 72.3 | 19.4 | 8.3 |

| Integrates the psychological aspects of patient care | 77.8 | 16.7 | 5.5 |

| Integrates the spiritual aspects of patient care | 77.8 | 16.6 | 5.6 |

| Offers a support system to help patients live as actively as possible until death | 72.2 | 25 | 2.8 |

| Offers a support system to help the family cope during the patient’s illness and in their own bereavement | 72.2 | 22.2 | 5.6 |

| Uses a team approach to address the needs of patients and their families | 55.6 | 41.6 | 2.8 |

| including bereavement counseling, if indicated | 63.9 | 22.2 | 13.9 |

| will enhance quality of life | 70 | 25 | 5 |

| and may also positively influence the course of illness | 77.8 | 13.9 | 8.3 |

| is applicable early in the course of illness | 72.2 | 27.8 | 0 |

| in conjunction with other therapies that are intended to prolong life such as chemotherapy or radiation therapy | 16.6 | 77.8 | 5.6 |

| and includes those investigations needed to better understand and manage distressing clinical complications2 | 70 | 19.1 | 10.9 |

| Additional Items Missing and Suggested by the Core Group | Include | Include With Revision | Do Not Include |

| Access to controlled medicines for pain relief and PC | 80.6 | 19.4 | 0 |

| PC also includes the management of acute pain (i.e., after trauma) | 11.1 | 2.8 | 86.1 |

| PC also includes the management of chronic pain in non-life-threatening diseases and conditions | 22.2 | 2.8 | 75 |

| PC services should also be available to children, older persons, and vulnerable populations | 88.9 | 8.3 | 2.8 |

| Applicable to special vulnerable population groups, including refugees and disaster victims, LBGT, and prisoners2 | 27.8 | 27.8 | 44.4 |

WHO = World Health Organization; PC = palliative care; LBGT = lesbian, bisexual, gay, transgender.

In bold: Components that reached ≥70% consensus.

Note: The option do not know/not sure was never selected.

For the four additional items (Table 3) not included in the WHO definition, there was consensus to include a statement about access to controlled medicines for pain relief and PC, and one on the provision of PC services to children, older persons, and vulnerable populations. The expert group agreed not to include management of acute pain and of chronic pain in non-life-threatening diseases and conditions.

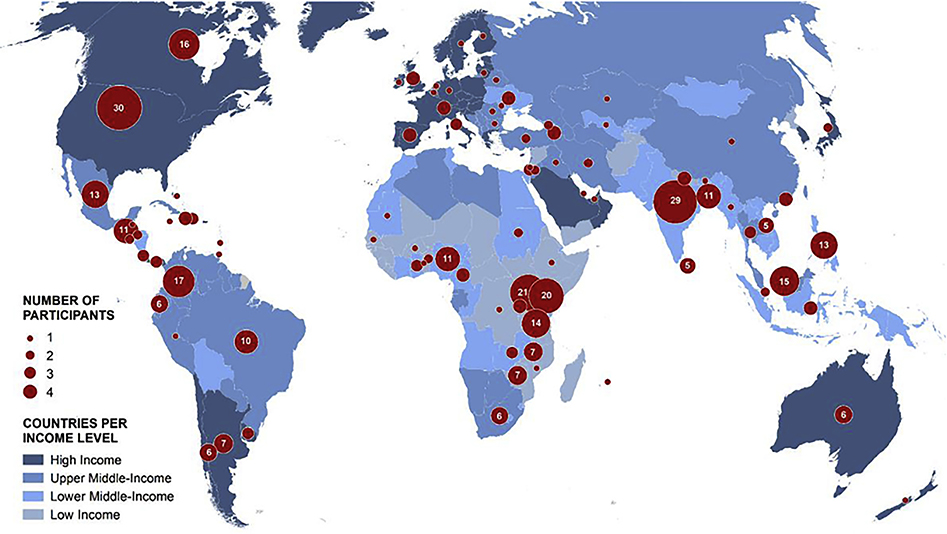

In Phase 2, 600 invitations were sent, and 412 completed the survey (response rate = 69%; see Disclosures and Acknowledgments section). Ninety-nine respondents were from high-income countries (HICs; 29% of 344 members), 101 from upper middle-income countries (45% of 224 members), 143 from LMICs (56% of 255 members), and 69 from low-income countries (LICs; 36% of 191 members) (Fig. 2). Participants represented a broad range of backgrounds, including health professionals, caregivers, and patients. There was a strong level of consensus with more than 90% of participants rating mostly or completely agree for all the items in the third Delphi round.14 A significant proportion of respondents (32%; n = 131) submitted additional comments and suggestions, addressing education, community, access to essential medicines, policy, service provision, funding/resources, and research.14

Fig. 2.

Countries represented in each income group and number of participants from each country in Phase 2.

In Phase 3, members of the core group revised the definition, and based on recommendations from some of its members, we added recommendations directed to national and local governments around how to achieve PC integration into health systems. The draft was then sent to the expert group from Phase 1. Thirty-six key persons of the initial 38 participated in this final phase. Three rounds of discussions and revisions were carried out until consensus was reached for a final text. The discussion highlighted significant differences and provoked extensive discussion among the participants on the restriction of PC to severe illness, which some participants criticized as too narrow, whereas others felt it excessively broadened the scope. Including a focus on end of life was another area of contention.

The resulting consensus definition was presented to WHO in September 2018 (Table 4). Up until the submission of this article, the WHO had not revised or modified its existing PC definition.

Table 4.

PC—Resulting Definition From Phase 3

| PC is the active holistic care of individuals across all ages with SHS (suffering is health related when it is associated with illness or injury of any kind. Health-related suffering is serious when it cannot be relieved without medical intervention and when it compromises physical, social, spiritual, and/or emotional functioning. Available from http://pallipedia.org/serious-health-related-suffering-shs/) because of severe illness (severe illness is a condition that carries a high risk of mortality, negatively impacts quality of life and daily function, and/or is burdensome in symptoms, treatments, or caregiver stress. Available from http://pallipedia.org/serious-illness/) and especially of those near the end of life. It aims to improve the quality of life of patients, their families, and their caregivers |

| PC: |

| • Includes, prevention, early identification, comprehensive assessment, and management of physical issues, including pain and other distressing symptoms, psychological distress, spiritual distress, and social needs. Whenever possible, these interventions must be evidence based |

| • Provides support to help patients live as fully as possible until death by facilitating effective communication, helping them, and their families determine goals of care |

| • Is applicable throughout the course of an illness, according to the patient’s needs |

| • Is provided in conjunction with disease-modifying therapies whenever needed |

| • May positively influence the course of illness |

| • Intends neither to hasten nor to postpone death, affirms life, and recognizes dying as a natural process |

| • Provides support to the family and caregivers during the patients’ illness, and in their own bereavement |

| • Is delivered recognizing and respecting the cultural values and beliefs of the patient and family |

| • Is applicable throughout all health care settings (place of residence and institutions) and in all levels (primary to tertiary) |

| • Can be provided by professionals with basic PC training |

| • Requires specialist PC with a multiprofessional team for referral of complex cases |

| To achieve PC integration, governments should: |

| • Adopt adequate policies and norms that include PC in health laws, national health programs, and national health budgets |

| • Ensure that insurance plans integrate PC as a component of programs |

| • Ensure access to essential medicines and technologies for pain relief and PC, including pediatric formulations |

| • Ensure that PC is part of all health services (from community health-based programs to hospitals), that everyone is assessed, and that all staff can provide basic PC with specialist teams available for referral and consultation |

| • Ensure access to adequate PC for vulnerable groups, including children and older persons |

| • Engage with universities, academia, and teaching hospitals to include PC research and PC training as an integral component of ongoing education, including basic, intermediate, specialist, and continuing education |

PC = palliative care; SHS = serious health-related suffering.

Discussion

Definition

This article describes a consensus-based process to develop a new PC definition that engaged PC stakeholders from around the world. To our knowledge, it is the first time that such a large-scale effort has been implemented to reach a definition for this field. Previous definitions,22 including the WHO definition,30 have been developed by a small group of individuals with no broader input. The definition described in this article resulting from a methodologically sound process reflects the consensus of more than 450 PC workers from around the globe, located in all geographical regions, representing different fields of work and working in different settings. The definition is well aligned with the 2014 resolution by the World Health Assembly on PC6 and reflects the international growth of and transitions in PC over time.

The resulting definition is based on the SHS concept, as put forward by the Lancet Commission. Emphasizing suffering as a mainstay of the new definition allows a further shift from a disease-centered conceptualization to a more person-centered approach to PC. The definition recognizes that PC should be delivered based on need rather than prognosis, is applicable in all care settings and levels, and encompasses both general and specialist care. Increasingly, SHS is replacing older concepts in population-based studies and strategic planning of health care delivery, to identify PC need and monitor effective access for target populations,31 and this revised definition is a useful complement to that work.

This consensus-based definition follows a similar structure to the current WHO definitions and is separated into two sections: an initial concise statement and a list of bulleted and more specific components.

A third section was added after participants suggested that a set of recommendations to governments should accompany the definition. These recommendations are directed to national and local governments on how to achieve PC integration into health systems as a component of Universal Health Coverage32 to achieve the sustainable development goals by 2030.33

The new definition includes family members and caregivers as the unit of care, thus requiring additional resources from care services, which may be challenging to health care systems with limited resources.

Feedback From Panelists

During the first Delphi round in Phase 1, there was no consensus among the experts on 12 components, but analysis of their comments indicated concerns with form rather than substance. For example, there was no consensus to keep the component Provides relief of pain, as the relief cannot be guaranteed, although pain should always be evaluated and managed when present. The experts agreed that the aim is to relieve pain, enhance quality of life, and relieve suffering, but there is no assurance that these will be completely achieved.

Comments from the large number of participants in the second phase of the study highlighted differences among specialized PC professionals working in HIC and in complex settings and those working at the community level in countries with fewer resources. One participant from Australia commented: … emphasizing care in the community overlooks the current reality that the majority of people (at least in developed countries) die in hospital, where end of life care is often suboptimal and needs support, whereas another from Nigeria stated: Integrating palliative care services proactively at the primary and community level is supposed to be the bedrock of the services. Many comments underscored the need to implement robust PC training programs for health care professionals both at the undergraduate and specialty levels. Trained professionals are a scarce resource in countries in all income levels. However, even in HIC, a significant percentage of PC is delivered by nonspecialist PC staff, including not only general practitioners and other physicians but also nurses and allied health care professionals. In consequence, the Lancet Commission advocated that all health care professionals caring for severely ill patients should have basic PC training as part of their formal education.4

Perceptions

During all the phases of the study, it became clear that participants had significantly different perceptions and interpretations of PC. The greatest challenge faced by the core group was trying to find a middle ground between those who think that PC is the relief of all suffering and those who believe that PC describes the care of those with a very limited remaining life span.

The term that generated the most divergent opinions was severe illness. Severe illness has been defined by the Lancet Commission as any acute or chronic illness and/or health condition that carries a high risk of mortality, negatively impacts quality of life and daily function, and/or is burdensome in symptoms, treatments, or caregiver stress.34 Some experts disagreed with the term because it excludes patients with less than severe conditions from access to care, as they think that PC is to relieve all health-related suffering (e.g., including acute trauma). Other experts rejected the term for exactly opposite reasons, as they argued that it broadens the scope too much, with the potential of confusing providers, administrators, policy makers, and funders. Their concern was that the resulting ambiguity surrounding the use of this term would open up PC to treating any illness including acute or transitory conditions. The discussion highlighted that an inclusive term is extremely important, even more so in LICs, where many times patients with other than life-limiting diseases face considerable suffering if they cannot access PC. The members of the core group decided to keep the term severe illness with the addition of a special—but not exclusive—focus on the end of life.

Some participants were critical of the term end of life and felt that the definition was too focused on death and dying. However, of all the vulnerable groups in PC, those facing end of life are the most fragile and the ones with the weakest voices. Health systems—especially in countries with limited resources—tend to leave dying patients on the fringes and not allocate resources for their care. Including specific mention of end of life in the definition serves as a reminder to professionals, policy makers, and funders that patients at the end of life represent an important group requiring health care. The final wording of the definition seemed to present the broadest common denominator for all participants, as consensus was achieved for all statements at the end of the process.

Study Limitations

The definition was developed using an established consensus methodology. We followed the Conducting and REporting DElphi Studies recommendations for consensus building in PC. For example, we provided external validation by asking a number of international PC organizations to review the final version of the definition before publication and dissemination. Some organizations were very supportive, whereas others were quite critical, indicating a lack of agreement on some components of the new definition. The critical responses focused on the scope of the new definition being either too broad or too narrow. This highlights the wide range of practices, perspectives, and understanding of PC around the world and underscores the need to have a consensus-based definition. With this in mind, we considered all critical comments in the final definition, which marks the common ground among different PC settings.

The large group of participants in the second phase of the consensus process was recruited from the IAHPC membership, which led to a selection bias. Most of the IAHPC members are located in Africa (25%) and Asia (24%), followed by North America (19%), South America, (12%), Europe (10%), and other regions (10%). Notwithstanding, the IAHPC is one of the three international PC organizations with members located in all regions of the world. IAHPC membership is open to PC workers from all fields, including physicians, nurses, psychologists, social workers, spiritual care professionals, and many others.

The consensus panel included a representative selection, with comparable numbers of participants from HICs, middle-income countries, and LICs around the world, rather than being skewed toward the concentration of PC professionals in HIC. The sample reflects the higher met and unmet needs for PC in LMICs.4 This is a much broader approach than those used previously for other definitions, including WHOs. The expert group and consensus panel included pediatric and geriatric experts. A major shortcoming is the limited number of patients and caregivers in the development of the definition. The focus of the consensus process was on PC providers rather than patients, although several experts also had experienced PC as caregivers for a family member, and one expert was a cancer survivor. Feedback from these stakeholders is a key feature of the next stage of work on the proposed definition highlighting the need for more research that includes focus group analysis with patients of varying ages (including young people) and caregivers. This would ensure that the definition is understandable and sensitive to the voice of patients.

This study focused on describing the process to develop a consensus-based definition. No qualitative analysis of the participants’ perceptions and interpretations was performed. Further analysis of such information will be undertaken.

Dissemination

The IAHPC is facilitating and encouraging the dissemination and uptake of this work through its global network of PC organizations and members. For example, the definition has been translated by IAHPC members (using their mother tongues) into Arabic, Chinese, Dutch, Estonian, French, German, Greek, Indonesian (Bahasa), Italian, Japanese, Portuguese, Russian, and Spanish (available at https://hospicecare.com/what-we-do/projects/consensus-based-definition-of-palliative-care). Members who contributed to this project in a volunteer basis were given a three-month extension to their membership as a gesture of gratitude for their contribution.

As of November 2019, 180 hospice and PC organizations and academic centers as well as more than a 1000 individuals from countries from all world regions had endorsed and agreed to use the PC definition proposed in this article (https://hospicecare.com/what-we-do/projects/consensus-based-definition-of-palliative-care/endorses-list/).

Conclusion

Developing a consensus-based definition of PC required extensive deliberation, rigorous examination, and thorough testing. It was challenging to find common ground among individuals with long-standing experience in the field of PC who had firmly held positions.

Although the consensus-based definition is not perfect, it creates practice and policy value beyond its intended purpose of defining PC comprehensively and clearly. It provides an opportunity to examine international developments in the conceptualization and practice of PC and to achieve an explicit and shared understanding of that practice across the global community. The new definition is inclusive, encompasses health-system advances, and reflects the opinions and perceptions among a global community of professional health care providers. The new definition is aligned with the recommendations of the Lancet Commission, allowing for future synergy with efforts to implement the recommendations of its report and future implementation activities.

Future research is needed to evaluate the uptake, benefits, and challenges faced by those who use this new definition. This consensus-based definition must be open to critical discussion that includes patients and caregivers as well as providers. To this end, IAHPC continues to collate all feedbacks in what will be a continuous process of adapting the definition of PC to the ever-changing realities of patient needs.

Disclosures and Acknowledgments

The map on Fig. 1 was prepared by Dr. Juan Jose Pons, from the ATLANTES research group at the University of Navarra.

The authors are very grateful with the 412 IAHPC members who accepted their invitation to participate in Phase 2 of this project. The participants and their country of residence are included in Table 2.

This research received no specific funding/grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

A portion of the salary of L. D. L. was covered by a core support grant, IAHPC Core Support, from the U.S. Cancer Pain Relief Committee and the grant Advancing palliative care through advocacy for policy changes from Open Society Foundations (grant number: OR2018-41903).

Lukas Radbruch is chair of the board of directors of the IAHPC. Liliana de Lima is chief executive officer of the IAHPC. Katherine Pettus is employed as advocacy officer of the IAHPC. Marry Callaway, Julia Downing, Hibah Osman, Dingle Spence, Citra Venkateswaran, Roberto Wenk, and Roger Woodruff are members of the board of directors of IAHPC. Felicia Knaul has chaired the Lancet Commission on Global Access to Palliative Care and Pain Relief. Zipporah Ali is executive director of the Kenya Hospices and Palliative Care Association. Stephen Connor is executive director of the Worldwide Hospice and Palliative Care Alliance. Julia Downing is chief executive officer of the International Children’s Hospice and Palliative Care Network. Philip Larkin is past president of the European Association for Palliative Care. Sebastien Moine is a member of the board of directors of the European Association for Palliative Care. M. R. Rajagopal is chairman of Pallium India. Tania Pastrana is president of the Asociación Latinoamericana de Cuidados Paliativos.

Ethical approval: The project did not involve any therapeutic intervention. Ethical aspects of the consensus project, for example, on data protection, were discussed extensively among the board of directors of IAHPC. The project plan was submitted to the Ethics Committee at the Fundacion Federación Médica de la Provincia de Buenos Aires in Argentina by one of the lead authors (R. W.) and was approved with no ethical issues raised.

Contributor Information

Lukas Radbruch, Department of Palliative Medicine, University Hospital Bonn, Bonn, Germany.

Liliana De Lima, International Association for Hospice and Palliative Care, Houston, Texas.

Felicia Knaul, University of Miami Institute for Advanced Study of the Americas, Coral Gables, Florida, USA.

Roberto Wenk, San Nicolash, Argentina.

Zipporah Ali, Kenian Hospice and Palliative Care Association, Nairobi, Kenya.

Sushma Bhatnaghar, Department of Onco-Anaesthesia and Palliative Medicine, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India.

Charmaine Blanchard, Wits Centre for Palliative Care, University of the Witwatersrand Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa.

Eduardo Bruera, Department of Palliative Rehabilitation and Integrative Medicine, MD Anderson Cancer Center Houston, Houston, Texas, USA.

Rosa Buitrago, School of Pharmacy, University of Panama, Panama City, Panama.

Claudia Burla, Private Practice, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Mary Callaway, New York, New York, USA.

Esther Cege Munyoro, Pain and Palliative Care Unit, Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi, Kenya.

Carlos Centeno, Department of Palliative Medicine, Clinica Universidad de Navarra, Navarra, Spain.

Jim Cleary, Department of Medicine, IU Simon Cancer Center, IU School of Medicine, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA.

Stephen Connor, Worldwide Hospice Palliative Care Alliance, London, United Kingdom.

Odontuya Davaasuren, General Practice and Basic Skills Department, Mongolian National University of Medical Sciences, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia.

Julia Downing, International Children’s Palliative Care Network, Cape town, South Africa.

Kathleen Foley, New York, New York, USA.

Cynthia Goh, Division of Palliative Medicine at the National Cancer Centre Singapore, Singapore.

Wendy Gomez-Garcia, Clínica de Linfomas and LMA Cuidados Paliativos and Terapia Metronómica, King’s College London, London, United Kingdom.

Richard Harding, Hospital Infantil Dr. Robert Reid Cabral, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic; Centre for Global Health Palliative Care, King’s College London, London, United Kingdom.

Quach T. Khan, Palliative Care Department, Ho Chi Minh City Oncology Hospital, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

Phillippe Larkin, Institut universitaire de formation et de recherche en soins, Universite de Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland.

Mhoira Leng, Department of Palliative Care, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda.

Emmanuel Luyirika, African Association for Palliative Care, University Parisse, Kampala, Uganda.

Joan Marston, International Children’s Palliative Care Network, Cape town, South Africa.

Sebastien Moine, Health Education and Practices Laboratory, University Parisse, Villetaneuse, France.

Hibah Osman, Palliative and Supportive Care Program at the American University of Beirut Medical Center, Palliative and Supportive Care Program at the American University of Beirut Medical Center.

Katherine Pettus, International Association for Hospice and Palliative Care, Houston, Texas.

Christina Puchalski, George Washington University’s Institute for Spirituality and Health, Washington, District of Columbia, USA.

M.R. Rajagopal, Trivandrum Institute of Palliative Sciences, Trivandrum, Kerala, India.

Dingle Spence, Hope Institute Hospital, Kingston, Jamaica.

Odette Spruijt, Australasian Palliative Link International, Melbourne, Australia.

Chitra Venkateswaran, Mehac Foundation, Kochi, Kerala, India.

Bee Wee, Sir Michael Sobell House, Oxford University Hospital, Oxford, United Kingdom.

Roger Woodruff, Melbourne, Australia.

Jinsun Yong, College of Nursing Catholic, University of Korea, Seoul, South Korea.

Tania Pastrana, Department of Palliative Medicine, University Hospital Aachen, Aachen, Germany.

References

- 1.World Health Organization, United Nations Children’s Fund. Declaration of Astana. 2018. Available from https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/primary-health/declaration/gcphc-declaration.pdf. Accessed April 24, 2019.

- 2.World Health Organization. Health in 2015: from MDGs, millennium development goals to SDGs, sustainable development goals. 2015. Available from https://www.who.int/gho/publications/mdgs-sdgs/en/. Accessed April 24, 2019.

- 3.Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance. Global Atlas of Palliative Care at the end of life. 2014. Available from http://www.who.int/nmh/Global_Atlas_of_Palliative_Care.pdf. Accessed March 16, 2015.

- 4.Knaul FM, Farmer PE, Krakauer EL, et al. Alleviating the access abyss in palliative care and pain relief—an imperative of universal health coverage: the Lancet Commission report. Lancet 2018;391:1391–1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gomez-Batiste X, Connor S. Building integrated palliative care programs and services. Barcelona: Liberdúplex, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Assembly. Strengthening of palliative care as a component of comprehensive care within the continuum of care. 2014. Available from http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA67/A67_R19-en.pdf. Accessed July 11, 2018.

- 7.Gomes B, Calanzani N, Curiale V, McCrone P, Higginson IJ. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of home palliative care services for adults with advanced illness and their caregivers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013: CD007760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith S, Brick A, O’Hara S, Normand C . Evidence on the cost and cost-effectiveness of palliative care: a literature review. Palliat Med 2014;28:130–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. Cancer pain relief and palliative care. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. Cancer pain relief and palliative care in children. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization. National Cancer Control Programmes. Policies and managerial guidelines, 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murray SA, Kendall M, Mitchell G, et al. Palliative care from diagnosis to death. BMJ 2017;356:j878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gwyther E, Krakauer E. WPCA Policy statement on defining palliative care. 2011. Available from http://www.thewhpca.org/resources/item/definging-palliative-care. Accessed January 14, 2019.

- 14.Radbruch L, De Lima L, Knaul F, et al. Redefining palliative care—a new consensus-based definition:supplemental material. 2019. Available from https://hospicecare.com/uploads/2019/9/PC%20Definition%20-%20online%20supplement%20material%20for%20IAHPC%20website.pdf. Accessed September 26, 2019.

- 15.American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Care. Strategic plan (glossary). 2016. Available from http://aahpm.org/uploads/2016-2020_Final_Strategic_Plan.pdf. Accessed April 25, 2019.

- 16.Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association. What is palliative care?. Available from http://www.chpca.net/family-caregivers/faqs.aspx. Accessed April 25, 2019.

- 17.European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC). What is palliative care?. Available from https://www.eapcnet.eu/about-us/what-we-do. Accessed April 25, 2019.

- 18.Palliative Care Australia. What is palliative care?. Available from https://palliativecare.org.au/what-is-palliative-care. Accessed April 25, 2019.

- 19.The National Council for Palliative Care. Palliative care explained. Available from https://www.ncpc.org.uk/palliative-care-explained. Accessed April 25, 2019.

- 20.Ministry of Health New Zealand (Palliative care subcommittee). What is palliative care? Available from https://www.health.govt.nz/your-health/services-and-support/health-care-services/palliative-care. Accessed April 25, 2019.

- 21.International Children’s Palliative Care Network. What is palliative care? Available from http://www.icpcn.org/abouticpcn/what-is-childrens-palliative-care/. Accessed April 25, 2019.

- 22.Pastrana T, Junger S, Ostgathe C, Elsner F, Radbruch L. A matter of definition—key elements identified in a discourse analysis of definitions of palliative care. Palliat Med 2008;22:222–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haun MW, Estel S, Rucker G, et al. Early palliative care for adults with advanced cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017:CD011129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dalgaard KM, Bergenholtz H, Nielsen ME, Timm H. Early integration of palliative care in hospitals: a systematic review on methods, barriers, and outcome. Palliat Support Care 2014;12:495–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harding R, Foley KM, Connor SR, Jaramillo E. Palliative and end-of-life care in the global response to multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Lancet Infect Dis 2012;12:643–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nouvet E, Kouyaté S, Bezanson K, et al. Preparing for the dying and ‘dying in honor’: Guineans’ perceptions of palliative care in Ebola treatment centers. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018;56:e55–e56. [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization. Integrating palliative care and symptom relief into the response to humanitarian emergencies and crises. 2018. Available from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/274565/9789241514460-eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed January 15, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Junger S, Payne SA, Brine J, Radbruch L, Brearley SG . Guidance on Conducting and REporting DElphi Studies (CREDES) in palliative care: recommendations based on a methodological systematic review. Palliat Med 2017;31: 684–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups. 2020. Available from https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519. Accessed April 10, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sepulveda C, Marlin A, Yoshida T, Ullrich A. Palliative care: the World Health Organization’s global perspective. J Pain Symptom Manage 2002;24:91–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sleeman KE, de Brito M, Etkind S, et al. The escalating global burden of serious health-related suffering: projections to 2060 by world regions, age groups, and health conditions. Lancet Glob Health 2019;7:e883–e892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knaul FM. Integrating palliative care into health systems is essential to achieve Universal Health Coverage. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:e566–e567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krakauer E, Kwete X, Verguet S, et al. Palliative care and pain control. In: Disease control priorities: Improving health and reducing poverty, 3rd ed. Washington, DC: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.International Association for Hospice and Palliative Care. Pallipedia—the online palliative care dictionary. Serious illness. Available from http://pallipedia.org/serious-illness/. Accessed April 26, 2019. [Google Scholar]