Abstract

The study investigated the impact of the electronic Goal Attainment Scaling (eGAS) process on medical speech-language pathologists’ (SLPs) interviewing and goal setting. The process was trained via the eGAS app, designed to facilitate motivational interviewing and goal attainment scaling. The study utilized a single-case, nonconcurrent, multiple-baseline design replicated across three clinicians and their 27 respective clients. We observed client-clinician dyads engaged in setting rehabilitation goals pre and post eGAS training. The clients had neurogenic conditions and were being treated for cognitive, communication and/or swallowing challenges in an outpatient setting. Two measures were used to collect data on the clinician’s interviewing and goal-setting behaviors: (1) Assessment of Client-Centeredness when Interviewing and Goal Setting (ACIG) scale, and (2) a task analysis, i.e., the Clinician Interview Behavior scale (CIB). Training with eGAS had a strong effect on clinicians’ collaborative interviewing behaviors, an inconsistent effect on their ability to adhere to a three-phase interview structure, and a strong effect on their ability to generate valid goal attainment scales. This study provides preliminary support that the eGAS process provides a feasible framework for training hospital-based SLPs engaged in neurorehabilitation to use collaborative interviewing behaviors and produce valid person-centered rehabilitation goals.

Keywords: Goal-setting, Collaborative, Patient-centered, Patient-reported, Neurogenic

The confluence of several healthcare movements and advances in rehabilitation research, have urged practitioners to involve patients in evaluating healthcare processes and measuring outcomes (D’Arcy & Rich, 2012; Quatrano & Cruz, 2011). Patient-centered outcome measures (PCOMs) or tools that engage clients in the process of identifying goals, priorities, and measuring rehabilitation outcomes have been linked to decreased healthcare costs, higher goal attainment, and improved self-efficacy (Bertakis & Azari, 2011; Black et al., 2010; Donnelly & Carswell, 2002; Locklear, 2015; Prescott et al., 2015; Willer & Miller, 1976; Wressle et al., 2002). Over 100 studies have been published in the last two decades that explore the importance, benefits, and challenges with generating person-centered goals in the acquired disability population across a variety of healthcare settings (Levack et al., 2015). Although researchers have critiqued the quality of evidence, the literature base suggests that involving clients in conversations regarding rehabilitation goals is associated with improved treatment adherence, goal attainment and patient satisfaction (Bergquist et al., 2012; Doig et al., 2011; Krasny-Pacini et al., 2014; Prescott et al., 2015; Watermeyer et al., 2016). Standardized cognitive tests cannot capture functional outcomes of the heterogeneous ABI population (Chaytor & Schmitter-Edgecombe, 2003; Cicerone et al., 2011) necessitating alternative measurement paradigms. Despite the growing literature base, legal mandates and clinical need incentivizing the use of PCOMs, they are underutilized within the field of speech-language pathology as measures of neurorehabilitation efficacy.

Two major barriers affect the adoption and uptake of PCOMs as outcome measures. One concern is the design and validity of currently used PCOM tools. Existing tools commonly utilize a survey-based approach to elicit client input with pre-set survey items that are not universally applicable, and are often fraught with floor or ceiling effects (Stevens et al., 2013; Wilde et al., 2010). A second barrier is clinicians’ reluctance to use alternative PCOMs that promote personalized goal setting based on collaborative conversations. Clinicians perceive the mechanics of initiating, engaging, and sustaining a conversation with a client who has cognitive-communicative impairments to establish personal goals that serve as valid and measurable outcomes, as overly complex and time consuming (Plant et al., 2016; Rosewilliam et al., 2016).

A potential solution to the barriers in using patient-centered outcome measures

The literature suggests that personal goal-setting techniques are feasible and valid when the process is sufficiently operationalized (Dörfler & Kulnik, 2019; Lawton et al., 2018). Two structured goal-setting frameworks that have the potential to mitigate measurement and feasibility concerns are Goal Attainment Scaling (GAS; Kiresuk & Sherman, 1968) and Motivational Interviewing (MI; Medley & Powell, 2010).

GAS is a method for deriving personalized goals and turning them into quantifiable, measurable evaluation scales that serve as a valid, sensitive, and responsive measure of personalized progress in individuals with ABI (Bovend’Eerdt et al., 2009; Grant & Ponsford, 2014; Kiresuk & Sherman, 1968). An international group of researchers reviewed the literature and proposed 17 appraisal criteria to ensure that GAS is sufficiently valid and reliable to be used in a randomized controlled trial. The authors used the acronym “SMARTED” (specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, time-specific, equidistant, and (uni)dimensional) to identify key characteristics and provide an objective way to measure the validity and reliability of GAS (Krasny-Pacini et al., 2016; Turner-Stokes et al., 2009). Specificity refers to whether the overarching goal is directly related to the intervention. Measurable refers to whether the goal attainment indicators are observable and quantifiable. Attainability refers to whether the client could carry out the objective if they were able, for example, they have access to a device they are learning to use. Relevance means that the goal is meaningful to the individual client. Equidistance refers to the intervals between the levels being equivalent. Unidimensional refers to the fact that the goal attainment scale is for one specific construct or overarching goal. From a feasibility standpoint, it is difficult to achieve these criteria because a client-centric conversation is rooted in the clinician’s ability to tailor the conversation to client-specific needs (Plant et al., 2016). Although the GAS methodology prescribes steps for turning goals into measurable progress indicators, the largely subjective criteria of “including client” remains idiosyncratic and elusive and often poses risks for the degree to which a goal can be considered client-centered, individualized, and meaningful (Krasny-Pacini et al., 2016; Prescott et al., 2015; Schlosser, 2004). One purpose of the present study was to address this challenge.

Conversational exchange relevant to goal setting can be fostered by using motivational interviewing (MI), a client-centered communication approach to promote engagement, readiness for rehabilitation and evoke motivation for change, while ensuring the client’s autonomy throughout the exchange. It is defined as a collaborative, goal-oriented style of communication with particular attention to the language of change (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). MI is comprised of a series of interview and counseling techniques grounded in a philosophy of collaborative therapy that include open-ended questions, affirmations, reflections, and summaries (often referred to collectively as OARS). The focus on empowering clients using these faciliatory communication techniques makes it an effective rehabilitation goal setting methodology for the ABI population (Medley & Powell, 2010). A current practice gap is produced by SLPs lack training in MI, and the absence of clinical tools that facilitate MI by allied health providers working in neurorehabilitation.

The electronic Goal Attainment Scaling (eGAS) tool is an app that integrates GAS and MI. eGAS was designed to promote person-centered goal setting and address the need for an efficient, clinically feasible, and individualized measure that facilitated creation of valid, reliable, and measurable client-centric goals. The purpose of this research study was to ecologically measure the impact of training medical SLPs to use the eGAS tool within a hospital context. Specifically, we examined the potential impact of eGAS exposure on clinician interviewing and goal-setting skills in an outpatient setting. Impact, within the context of this study, was defined as a clinician’s ability to conduct a collaborative, client-centered interview that addressed three key areas (problem identification, treatment selection, and construction of valid goal attainment scales).

Research questions

The study sought to examine the following primary research questions:

Is there a functional relation between training and exposure to the eGAS process and an increase in (a) clinician collaborative interviewing behaviors, and (b) adherence to a structured interview format?

Is there a functional relation between exposure to the eGAS process and an increase in the validity of patient goal attainment scales?

Our hypothesis was that training in the eGAS process would effectively teach key concepts and provide an ongoing reference of target behaviors with the following outcome: clinicians would increase their use of collaborative interviewing techniques, and adhere to the interview format that involved three interview phases, and construct goal attainment scales that met the SMARTED criteria. This was a preliminary evaluation to examine the malleability of clinician goal setting behavior based on structured training and ongoing prompting in MI and GAS specific to the neurogenic rehabilitation context.

Methods

Setting characteristics

We sought to identify a hospital setting in which to conduct the study that met the following criteria: (1) treated patients with acquired or progressive neurological diagnoses affecting cognitive-communicative function; (2) employed SLPs in the treatment of these diagnoses; (3) had the capacity to accommodate the demands of a research study (e.g., capacity for recording and observing of sessions, an institutional review board); (4) had an institutional mission aligned with the objectives of the study and valued patient-centered treatment, and (5) had no previous association or relationship with the researchers. Casa Colina Hospital located in in southern California met all selection criteria and agreed to participate.

Participant characteristics

Study participants included both clinicians and their rehabilitation clients.

Clinicians.

An informational orientation meeting was held to describe the study, and interested SLPs met with the first author to verify that they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) actively delivering neurorehabilitation services to adults; (2) reported that at least 20% of the caseload included individuals with an ABI; (3) not familiar with the eGAS app; and (4) no previous exposure to either MI or GAS. Three interested and eligible clinicians were consented according to the facility and university institutional review panels. All three SLPs worked in outpatient services, their experience levels ranged from 1 to 10 years of clinical practice. Table 1 displays the experience level, ethnicity, and age of the participating clinicians.

Table 1.

Clinician characteristics.

| Clinician | Experience (years) | Ethnicity | Age |

|---|---|---|---|

| ML | 10 | Caucasian | 58 |

| HG | 1 | Caucasian | 25 |

| MP | 5 | Asian | 32 |

Note. The experience level represents the number of years a clinician has spent in professional practice.

Clients.

Clients needed to meet the following inclusion criteria to be eligible for recruitment: (1) adults seeking neurorehabilitation provided by SLPs as a result of mild to moderate cognitive, speech, language, and/or swallowing impairment due to an acquired brain injury, a neurodegenerative condition, or other neurological disease, and (2) adequate cognitive-communicative skills to engage in a goal-setting conversation. Clients were excluded if they were: (1) unable to communicate as a result of severe speech and/or language impairment, and (2) were not their own guardian. Informally, the ability to communicate was ascertained in two ways. First, the PI reviewed client medical records to identify any contraindications in the notes that would suggest that they could not participate. Notes from the speech-language pathologist, physicians, and when available neurologists were reviewed to discern diagnoses or conditions that would prevent a client from successfully conversing with the clinician. Examples of contraindications would include co-morbidities such as dementia that would affect a client’s ability to engage in a multi-turn conversation or severe apraxia or aphasia that would require significant support from clinician and caregivers to engage in conversation. Secondly, when the PI called to confirm the appointment, the conversation with the client or the caregiver was used to confirm that communication deficits were not detrimental to engaging in such a conversation. Of the 32 clients who were referred, three were not interested in participating and two did not meet criteria, yielding a sample of 27 clients. Written consent was obtained prior to audio recording and observing the clients’ interactions with their respective clinicians.

Clients ranged from 18–82 years of age, with the average age being 58 years. Approximately 56% of the sample was male and 44% female. 41% of clients were seeking cognitive rehabilitation with the remaining 59% seeking services for aphasia, dysphagia, and/or dysarthria. The most common diagnoses were cerebrovascular accident (CVA) (41%) and traumatic brain injury (TBI) (30%). 81% of the sample displayed either a mild or a moderate degree of impairment, while the remaining 19% displayed deficits in the mild-moderate range. See Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of client characteristics.

| Characteristics | Frequency | |

|---|---|---|

| Etiology | ||

| TBI | 7 (26%) | |

| CVA | 11 (41%) | |

| Neurodegenerative (Multiple Sclerosis, Parkinson Disease, Systemic Sclerosis, Spinal Ataxia) | 5 (19%) | |

| Other (Bell’s Palsy, Neurofibromatosis, Cancer) | 4 (15%) | |

| Ethnicity | Male (n = 15) | Female (n = 12) |

| White | 6 (40%) | 3 (25%) |

| Black | 4 (27%) | 2 (17%) |

| Hispanic | 3 (20%) | 5 (42%) |

| Asian | 2 (13%) | 2 (25%) |

| Mean age in years (SD) | 57.36 (16.27) | 57.90 (16.94) |

| Cognitive-communicative diagnosis | Mild | Moderate |

| Cognitive impairment | 7 (26%) | 4 (15%) |

| Aphasia | 1 (3%) | 2 (7%) |

| Dysarthria/Apraxia | 3 (11%) | 2 (10%) |

| Dysphagia | 3 (11%) | 0 |

Note. N = 27.

Experimental design

We used a single-case experimental design, non-concurrent, multiple-baseline design. A multiple-baseline design enabled the systematic replication of effects across participants in a staggered manner, eliminating bias arising from confounding variables, such as small sample sizes and clinically heterogenous populations (Smith, 2012). The nonconcurrent aspect of the multiple-baseline design allowed flexibility in recruiting clinician-client dyads within a reasonable time-frame and accommodation of multiple extraneous factors inherent within unstandardized contexts (Byiers et al., 2012; Harvey et al., 2004).

The study design consisted of two phases: baseline (Phase A), and an experimental phase (Phase B). The independent variable was training in the eGAS process and ongoing access to the app. Prior to commencing Phase B, clinicians received training on using the eGAS framework and then were asked to use the app as reference during initial goal setting interviews with clients. Data on the dependent variables, i.e., clinicians’ interviewing behaviors, adherence to the interview phase structure, and validity of the generated scales, were collected using two project-specific measures, the Assessment of Client-Centeredness when Interviewing and Goal-setting (ACIG) scale and a task analysis called Clinical Interview Behavior (CIB).

The primary unit of analysis was the clinician-client dyad. The dyads comprised the same clinician interacting with different clients (e.g., three clinicians and 27 clients). Each data point, across both phases, represented a session when the SLP engaged in the initial goal setting conversation with a new client. Hence each of the 27 clients in the study contributed a single data point associated with goal setting. Sessions were conducted in the private offices typically used by the SLPs for treatment. Each session was audio recorded using a digital recorder (Olympus Model VN-541PC) to allow reliability and fidelity checks using a second-rater. The procedures were repeated for all three SLPs in the outpatient setting.

Baseline Phase.

During the baseline phase (Phase A), clinicians were asked to engage in their typical goal setting interviews with clients. While sessions were in progress, the first author collected data on clinicians’ interactional behaviors using the Clinician Interview Behavior (CIB) task analysis and the ACIG measure.

Per conventions of a non-concurrent single-case design, each clinician began the baseline phase at a different time and based on availability of patient evaluation sessions. For each clinician, the baseline phase was three to five data points. RoBinT quality appraisal suggests a strict minimum of three data points but acknowledge that five data is superior (Tate et al., 2013). It was not clinically appropriate to wait more than three to five data points. Clinicians commenced the experimental phase when the preceding clinician ended the baseline and initiated at least one session in the experimental phase which expanded the baseline phase up to five sessions for the second and third clinician. Following the baseline phase, each clinician underwent a two-hour training to learn the eGAS process in conjunction with app use.

Intervention Using eGAS. We designed the eGAS app with the goal of enabling clients and speech language pathologists to efficiently identify objective, personally meaningful goals in the following domains: cognition, motor speech, aphasia/social communication and swallowing. The purpose of the tool was to train clinicians and provide them with ongoing prompts about how to engage in client-centered goal setting based on principles of MI (Medley & Powell, 2010) and GAS (Kiresuk & Sherman, 1968).

Motivational interviewing is designed to strengthen personal motivation for and commitment to a specific goal by eliciting and exploring the person’s own reasons for change within an atmosphere of acceptance and compassion (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). The MI OARS communication techniques consist of strategic use of open ended questions, affirmations, reflections and summaries that have been shown to be effective with the ABI population (Medley & Powell, 2010).

GAS is a criterion-referenced outcome measure that allows objective evaluation of progress toward an overarching rehabilitation goal by dividing the goal into discrete levels. A common approach, and the one used in eGAS, is to divide the rehabilitation goal into five equidistant, measurable levels which form a goal attainment scale (Bovend’Eerdt et al., 2009; Schlosser, 2004). The eGAS app prompts clinicians to generate goal scales that contain five levels and meet the SMARTED criteria (Krasny-Pacini et al., 2016).

The eGAS tool divides the goal setting interview into four discrete phases. Three of these phases (Problem Identification, Treatment Selection, and GAS Construction) are considered vital to goal setting with clients who have neurogenic challenges following ABI, while the fourth phase (Buy-in) is optional and dependent on client motivation and responsivity to engaging in therapy. We use the term “buy-in” to signify encouragement and acceptance for clients who need information or counseling to pursue therapy or need guidance on narrowing and focusing on a single area of concern to ultimately construct goals. Client conversation drives the sequence of the eGAS and clinicians can switch between phases and do not have to follow any order. The tool contains sample scripted prompts for each phase, categorized by MI behaviors including open-ended questions, affirmations, reflections and summaries (OARS; Miller & Rollnick, 2002) to provide clinicians with a reference that contained examples of how to support a client in independently planning their desired rehabilitation process. An example of a script prompt for an open-ended question in the problem identification phase is “What would you like to be different than it is now?” An example of a script prompt for an affirmation in the treatment selection phase is “Sounds like you are motivated to figure out how to improve this.” Along with scripted sample prompts, the interface also provides eight buttons strategically labeled with preformulated dropdown menus to allow efficient documentation of: functional goal domains, activity and context for each of the rehabilitation domains. Additionally, templates are included for defining GAS levels, and weighting goals. (Readers may contact authors for examples of dropdown menus and templates.)

The app contains a digital manual which includes background, theory, instructions and videos and scripts of sample goal setting interviews. The eGAS app is designed to be delivered on an iPAD and provides information relevant to the interview and goal setting process. Ostensibly the eGAS information could be delivered using a paper/pencil format, but the electronic platform promoted efficiency and accessibility.

The eGAS app was designed with input from clinicians and clinical researchers using the Apple Testflight beta testing program (https://developer.apple.com/testflight/). Over 50 clinicians downloaded the app for trial and 30 provided feedback on design and functionality which was incorporated into the program used in this study. One group of researchers used eGAS to measure potential outcomes of an external cognitive aid training program with adults with Parkinson’s Disease (Spencer et al., 2020). Please see screenshots in Appendix A under the supplementary materials section.

eGAS Training.

The basic format and content of the training aligned with guidelines published for ensuring provider competency and skill acquisition (Madson et al., 2009). Training consisted of didactic instruction with embedded practice activities to elucidate the purpose and procedures for using the eGAS framework. Each training session lasted two hours and was conducted individually for each clinician in their respective office spaces. Didactic instruction was provided on the setup and procedure of the eGAS process, sample goal attainment scales, the OARS technique, and tips for talking with clients that displayed limited insight all of which were contained in the eGAS instructional manual. Practice activities included observing a sample video or a live demonstration of a clinician using eGAS. A checklist of sequential behaviors for each of the interview phases for a hypothetical interview served as the benchmark criteria for clinicians to be considered competent in implementing eGAS. Training emphasized integrity with the interview structure and process as opposed to fluency with the app. The app served as a platform to structure and teach key interview and goal setting behaviors and to provide ongoing support as a reference during the interview. Table 3 summarizes components of the training. Each clinician was requested to use eGAS for their next five consecutive evaluation consults which constituted the intervention phase for that clinician. Clients that met the inclusion criteria were selected from the pool of incoming admissions/referrals and assigned according to usual clinical protocol to clinicians based on their work schedule and availability.

Table 3.

Components of training for each clinician.

| Components | Elements |

|---|---|

| Didactic Instruction (using PowerPoint presentation slides) |

|

| Practice Activities |

|

Experimental Phase.

The experimental phase (Phase B) measured potential effects of training in the eGAS process when provided ongoing access to the app during interviews. It consisted of five data points for each clinician. Conducting the study in a naturalistic work setting with practicing clinicians enabled us to ecologically evaluate the impact of training the eGAS process, but posed a variety of challenges to internal validity. Providing clinicians with implementation feedback was limited by ethical constraints that precluded interfering during patient-provider interactions, and productivity demands restricting their time to receive and analyze feedback. To ensure a time-sensitive and minimally intrusive approach to ensuring integrity in the clinicians’ use of the eGAS process, the first author conducted 15-minute debriefing with clinicians after the first two sessions to discuss: (1) what went well, (2) what was challenging, and (3) what could be improved for the next session. A summary email was sent after the debriefing. If clinicians expressed further concerns or questions, they were referred to corresponding sections in the eGAS digial manual that addressed their questions. At the end of the experimental phase, clinicians completed two questionnaires, one questionnaire assessed the social validity of the eGAS app and the other assessed the social validity of the eGAS process. Each clinician also participated in a half-hour interview with the first author to provide feedback regarding the app, training protocol, and the implementation of the study. Table 4 summarizes the procedures used in the study.

Table 4.

Sequence of procedures for each participant.

| Parameters | Baseline | Post-Baseline | Experimental | Post-experimental |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Research aim | Observe typical interviewing routines | 2-hour training session for clinicians to use eGAS during interviews | Observe interviewing routines with eGAS | Assess social validity from clinician’s point of view |

| Measures | CIB Task-analysis* ACIG* | CIB Task-analysis ACIG | TARF-R** Informal interview** |

Note. ACIG = Assessment of Client-centered when Interviewing and Goal-setting. CIB = Clinician Interviewing Behavior scale.

Indicates measures that were administered repeatedly at every session.

Indicates measure that was administered only once.

Measures

Two project-specific measures were developed to measure the impact of eGAS on interviewing and goal setting behaviors. The first measure was the Assessment of Client-Centered Interviewing and Goal-setting (ACIG) scale, developed to assess the degree of adherence to eGAS process and phase outcome. The second measure was a task analysis, Clinician Interview Behaviors (CIB) checklist, that allowed repeated measurements of discrete interviewing and goal-setting behaviors hypothesized to change as a result of the eGAS training and ongoing prompts.

ACIG.

We developed the Assessment of Client-Centered Interviewing and Goal-setting (ACIG) to evaluate clinician adherence to the eGAS process, including MI techniques, collaborative interview behaviors, and goal attainment scaling (GAS) processes.

ACIG Development.

Development of the tool was derived from three bodies of literature containing relevant procedures and principles including: (1) studies elucidating methods to objectively measure collaborative communication (e.g., Leach et al., 2010; Sabee et al., 2015), (2) literature evaluating MI implementation fidelity (e.g., Dobber et al., 2015; Madson & Campbell, 2006), and (3) reviews appraising the quality of GAS (Krasny-Pacini et al., 2016). Specifically, Sabee and colleagues showed the importance of analyzing all stakeholder activity in an exchange using a specified classification scheme and prompted us to operationalize client-centric behaviors for all four sections of the eGAS interview process. Related, the literature also supported the use of a continuum extending from therapist-controlled to client-centered interview behavior as a way to quantify this aspect of the interview (Leach et al., 2010). The literature evaluating the implementation of MI further guided our development of ACIG suggesting multiple measures are needed to reliably measure all the ingredients of a dynamic process such as MI (Dobber et al., 2015; Jelsma et al., 2015; Madson & Campbell, 2006). Central for measuring the fidelity of MI was to evaluate the technical ingredients (i.e., frequency of use of OARS strategies and other MI techniques) as well as relational ingredients (i.e., behaviors that were representative of the MI spirit and collaborativeness (Madson & Campbell, 2006)). One existing reliable MI measurement is the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity Scale (Moyers et al., 2016) components of which were used to create the elements of the ACIG scale that assessed the degree to which clinicians’ communicative acts were client centric. Finally, we used the GAS quality appraisal guidelines proposed by Krasny-Pacini and colleagues (2016) to create an index to measure the validity of generated goal attainment scales. The acronym “SMARTED” (specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, time-specific, equidistant, and (uni)dimensional) reflects key characteristics emphasized in the literature that make GAS a valid outcome measure (Krasny-Pacini et al., 2016). See Appendix B for ACIG tool.

ACIG Scale Components.

The ACIG tool included two indices of interview behavior (Level of Client Centeredness Scale; Goal-setting Phase Outcome Scale) and one index of adhering to goal validity criteria (GAS Quality Appraisal Scale). The Level of Client Centeredness Scale was based on a scale of collaboration that could range from 0 (indicative of clinician-directed interviewing behaviors) to a maximum of 4 (indicative of client-led interviewing behaviors) for each of the four interview phases. The Goal-setting Phase Outcome Scale measured the degree to which the clinician met the intended outcome for each phase of the interview. For instance, on the Problem Identification phase of eGAS, the outcome score for a clinician ranged from 0 indicating unmet (no functional domain identified) to partially met (multiple functional domains identified but no domain prioritized), to 2 indicating met (a functional domain identified and prioritized). Scaled scores were aggregated across all 4 interview phases to create a maximum score of 8 and 12, for the level of client-centeredness, and the goal setting phase outcome, respectively. When the buy-in phase was excluded from an interview, the corresponding maximum score for each of those subscales was 6 and 9. A third outcome measure was the GAS Quality Appraisal Scale which reflected the degree to which scales met SMARTED criteria for validity. Goals received a score from 0 to 2 for each of the 8 criteria, resulting in a possible total score of 16. Appendix C describes the results of a small pilot study supporting the use of ACIG as a valid measure of the eGAS process.

Clinician Interview Behavior (CIB).

In addition to having the composite scores yielded by the ACIG tool, we created a task analysis (CIB) that allowed more discrete measurement of key behaviors. The task analysis was generated on the same principles as ACIG, and allowed for repeated measures critical to single subject experimentation. Descriptive indicators of ACIG’s level of client-centeredness, outcome, and GAS quality appraisal scales were used to create a 23-item scale that encapsulated strategic eGAS behaviors. Clinicians were assigned a score between 0 and 2 (0 = behavior not noted, 1 = behavior noted only once, 2 = behavior noted more than once) for each item on the scale. Scoring criteria measured aspects of adherence and competence to eGAS. While there was redundancy between the behaviors measured on the ACIG and the CIB, the CIB allowed a behavioral count of discrete behaviors, while the ACIG provided a conceptual measure by rating key interview practices and goal attainment scale components. The first author converted the frequency of 0s and 1s into a percentage that indicated the percentage of behaviors that were absent versus present, facilitating a direct measure of interview behaviors in addition to the composite score.

CIB Administration.

To record clinician behaviors in real-time during each interview, the first author used the Countee application (https://www.counteeapp.com/) on an iPad which allowed recording the frequency of each behavior on the CIB. The two ACIG interview scales (Level of Client-Centeredness Scale and the Goal-Setting Phase Outcome Scale) as well as the GAS validity measure (GAS Quality Appraisal Scale) were completed at the end of each interview.

Social Validity.

Clinician perspective on the eGAS process and app was examined via a standardized questionnaire and an informal interview. The Treatment Acceptance Rating Form - Revised (TARF-R; Reimers et al., 1992) is a global measure of treatment acceptability and consists of 17 questions focused on evaluating different aspects of acceptability. Aspects of acceptance measured by TARF-R include reasonableness of the treatment, perceived effectiveness, side-effects, disruption/time costs, affordability, willingness, severity of the problem, understanding of the treatment, and compliance with treatment variables. Items are rated on a five-point scale with descriptors for anchors based on the item. Higher scores represent greater levels of acceptability. Clinicians completed two forms: one to measure acceptability of the app, and a separate form to measure acceptability of the interviewing process.

Following completion of the project, each clinician participated in an informal interview. Every clinician was asked what they liked and what could be improved about the training, implementation of the research project, and the eGAS app. The first author transcribed clinicians’ responses for analysis while interviewing them in order to further investigate social validity.

Analysis

We used the traditional single-case research approach of visual analysis for analyzing data (Horner et al., 2005). We made observations regarding changes in level, trend, variability, immediacy of effect, degree of non-overlap, and consistency within, and across phases for each participant. It is important to note that visual analysis is useful for detecting clinical meaningful change, but has limited reliability and may inflate Type I errors (Mercer & Sterling, 2012). Therefore, visual analysis was supplemented with a quantitative, nonparametric approach, Tau-U to help detect statistically significant change (Perdices & Tate, 2009). Tau-U measures nonoverlap between baseline and intervention phases, as well as intervention phase trend to yield reliable estimates of effect size (Parker et al., 2011b). We used a web-based calculator (http://www.singlecaseresearch.org/calculators/tau-u) to calculate Tau-U values.

We interpreted Tau-U scores using the following benchmarks: .65 or lower: weak or small effect; .66 to .92: medium to high effect; and .93–1: large or strong effect (Parker et al., 2011a; Vannest & Ninci, 2015). No participants required baseline correction. Although results of visual analyses of the baseline data suggest that the outcome may not be significantly altered with baseline correction, the relatively small number of data points in the baseline phase might result in the statistical test not being sensitive to the presence of trend. Post-hoc within-subject effect size estimates were also calculated using a parametric test, standardized mean difference (SMD) Post-hoc analyses were conducted using SMD to quantify the degree of change in outcome variables for each clinician and across behaviors. We used a pooled standard deviation to calculate effect-size estimates. Effect-size estimates were interpreted using benchmarks observed in the single-case aphasia literature (Beeson & Robey, 2006): 2.6–3.89: small; 3.9–5.79: medium, and 5.80 or higher: largesized effect. Along with statistical analyses, we also conducted descriptive analyses to analyze post-experimental social validity data.

Results

Results are reported for each of the research questions.

Research Question 1: Is there a functional relation between use of eGAS and an increase in (a) clinician collaborative interviewing behaviors, and (b) adherence to the three interview phases?

Our hypothesis was that training in the eGAS process and ongoing access to the app would result in functional increases in collaborative interviewing skills as measured by (1) ACIG’s Level of Client-Centeredness Scale and (2) the CIB. Results from both measures showed a strong functional relation between the training in the eGAS process and ongoing access to the app and an increase in the percentage of collaborative interviewing behaviors.

Client collaborative interviewing behavior.

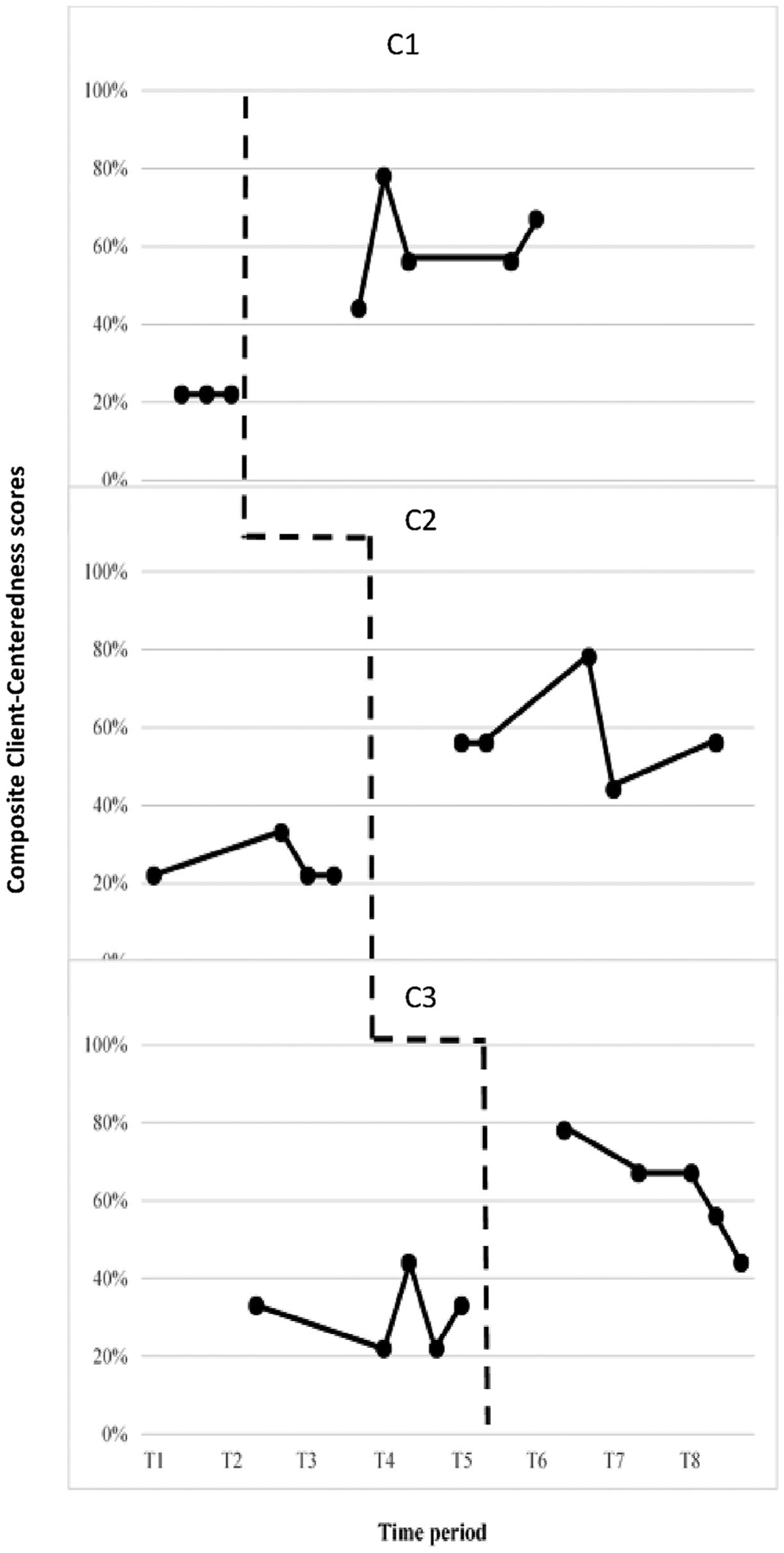

Figure 1 demonstrates the effects of eGAS on following person-centered interviewing practices for the three goal setting phases (Problem Identification, Treatment Selection and GAS Construction) as measured by ACIG’s Level of Client-Centeredness Scale. The Buy-In Phase was not analyzed as not every client needed facilitation of buy-in to treatment. Visual analysis of the data suggested that all three clinicians demonstrated: (1) an immediacy effect, and (2) an increase in the overall level of scores. For clinician 3, C3, a decrease in the trend of the score percentage was noted. However, the Tau U scores 1.00, 1.00, and 0.96 suggested a large or strong effect despite the decreasing trend in the experimental phase for the third clinician. Table 5 displays Tau U scores, z and p values for each clinician. Weighted average Tau U scores (refer to Table 6) as measured by the ACIG Level of Client-Centeredness scale suggests an overall strong treatment effect across the three tiers on the degree of client-centeredness.

Figure 1.

ACIG’s level of client-centeredness scale.

Table 5.

Tau U, z, and p values by measure and clinician.

| Measure | Tau U | Z | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACIG Level of Client-centeredness | |||

| C1 | 1 | 2.24 | 0.03 |

| C2 | 1 | 2.45 | 0.02 |

| C3 | 0.96 | 2.51 | 0.01 |

| ACIG Goal-setting Phase Outcome | |||

| C1 | 1 | 2.24 | 0.03 |

| C2 | 1 | 2.45 | 0.01 |

| C3 | 0.44 | 1.15 | 0.25 |

| CIB (Present behaviors) | - | - | - |

| C1 | 1 | 2.24 | 0.03 |

| C2 | 1 | 2.45 | 0.01 |

| C3 | 1 | 2.61 | 0.00 |

| GAS Quality Appraisal Scale | - | - | - |

| C1 | 1 | 2.24 | 0.03 |

| C2 | 0.95 | 2.33 | 0.02 |

| C3 | 0.96 | 2.51 | 0.01 |

Note. ACIG = Assessment of Client-centeredness when Interviewing and Goal-setting.

CIB = Clinician Interview Behaviors. GAS = Goal Attainment Scale.

Autocorrelation of data may alter p values.

Table 6.

Weighted average values by measure.

| Measure | Tau U | z | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACIG Level of Client-Centeredness | 0.99 | 4.13 | 0 |

| ACIG Goal-setting Phase Outcome | 0.78 | 3.35 | 0.0008 |

| CIB (Present behaviors) | 1 | 4.19 | 0 |

| GAS Quality Appraisal Scale | 0.97 | 4.06 | 0 |

Note. ACIG = Assessment of Client-centeredness when Interviewing and Goal-setting.

CIB = Clinician Interview Behaviors. GAS = Goal Attainment Scale.

Autocorrelation of data may alter p values.

Post-hoc analyses to quantify the degree of change in composite client-centeredness scores using SMD revealed that all three clinicians showed small changes in response to eGAS (SMD between 2.6 and 3.89).

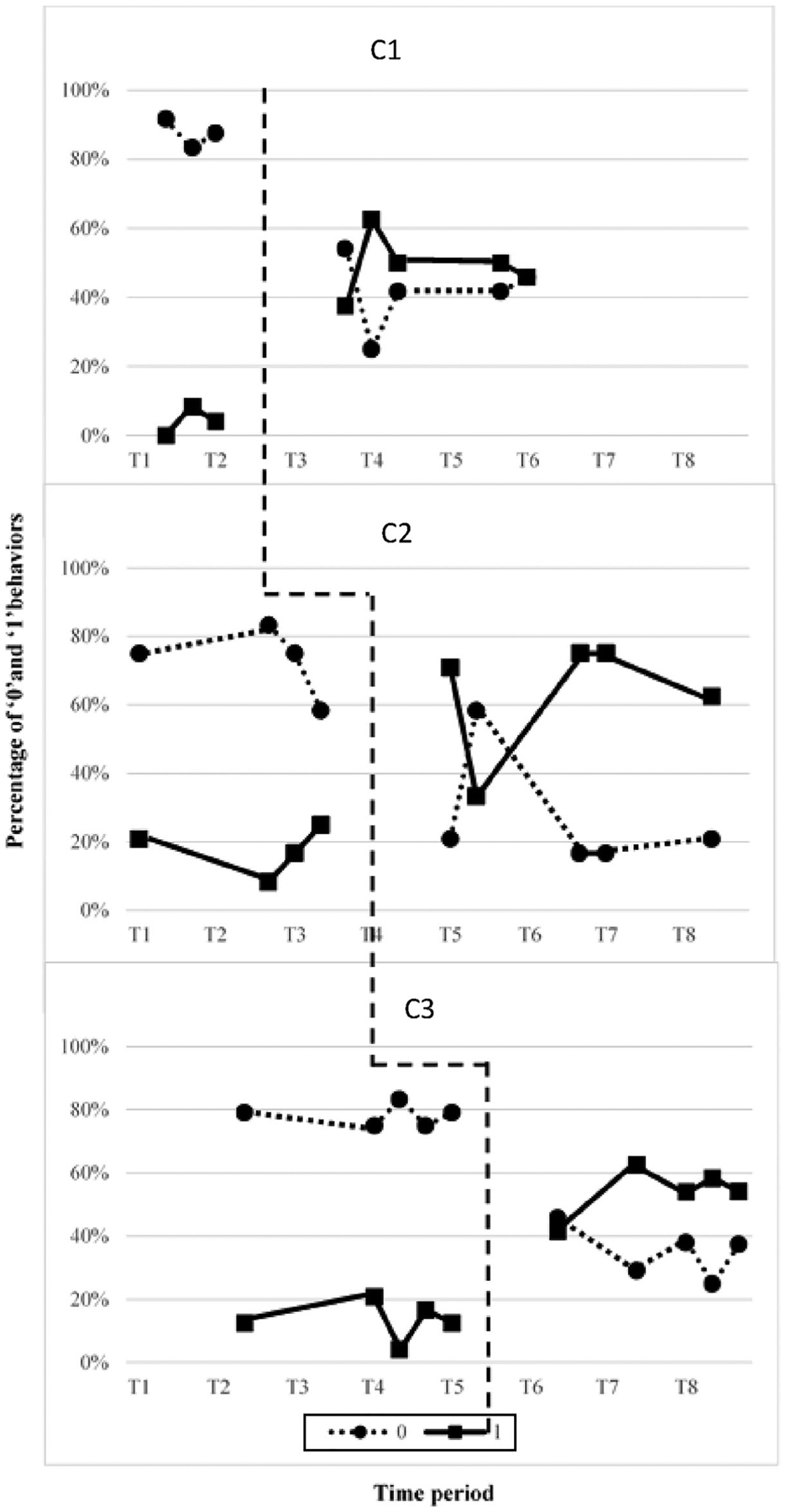

Figure 2 illustrates the percentage of collaborative interviewing behaviors that were present (behaviors with a score of “1”) versus absent (behaviors with a score of “0”) based on the CIB. Visual analysis revealed that all three clinicians demonstrated: (1) an immediacy effect from baseline to experimental phases, (2) a distinct decrease in the level of percentage of absent behaviors accompanied with a corresponding increase in the level of percentage of present behaviors. For participant 2, C2, stability of baseline data was questionable given the increasing trend in the percentage of 1s with a corresponding decreasing trend of 0s. However, the Tau U score of 1 for all three clinicians when analyzing data of percentage of behaviors receiving a score of 1 suggested a large or strong effect despite the increasing trend in baseline phase for the second clinician. Table 5 displays Tau U scores, z and p values for each clinician. Weighted average Tau U scores (refer to Table 6) as measured by the CIB scale suggests an overall strong treatment effect across the three tiers on the percentage of present behaviors.

Figure 2.

CIB Task-analysis depicting the percentage of present (1) and absent (0) behaviors.

Post-hoc analyses were completed to quantify the degree of change in each item of the TA as well as degree of change for each clinician from baseline to experimental phase in response to eGAS use. Two of three clinicians demonstrated medium effect sizes (SMD > 3.9) and one clinician showed small effect size (SMD > 2.6). To determine change in each item of the TA, data were pooled for each phase across clinicians. Behaviors consistently present for all clinicians increased from 4% to 25% in the baseline phase to at least 49% of the items on the task analysis in the experimental phase. When pooling data across phases, three interview behaviors (i.e., defining 3 of 5 GAS levels) showed small changes (SMD > 2.6) and incorporating the goal attainment scale criteria of unidimensionality showed medium effect sizes (SMD > 3.9).

Adherence to Interview Phases.

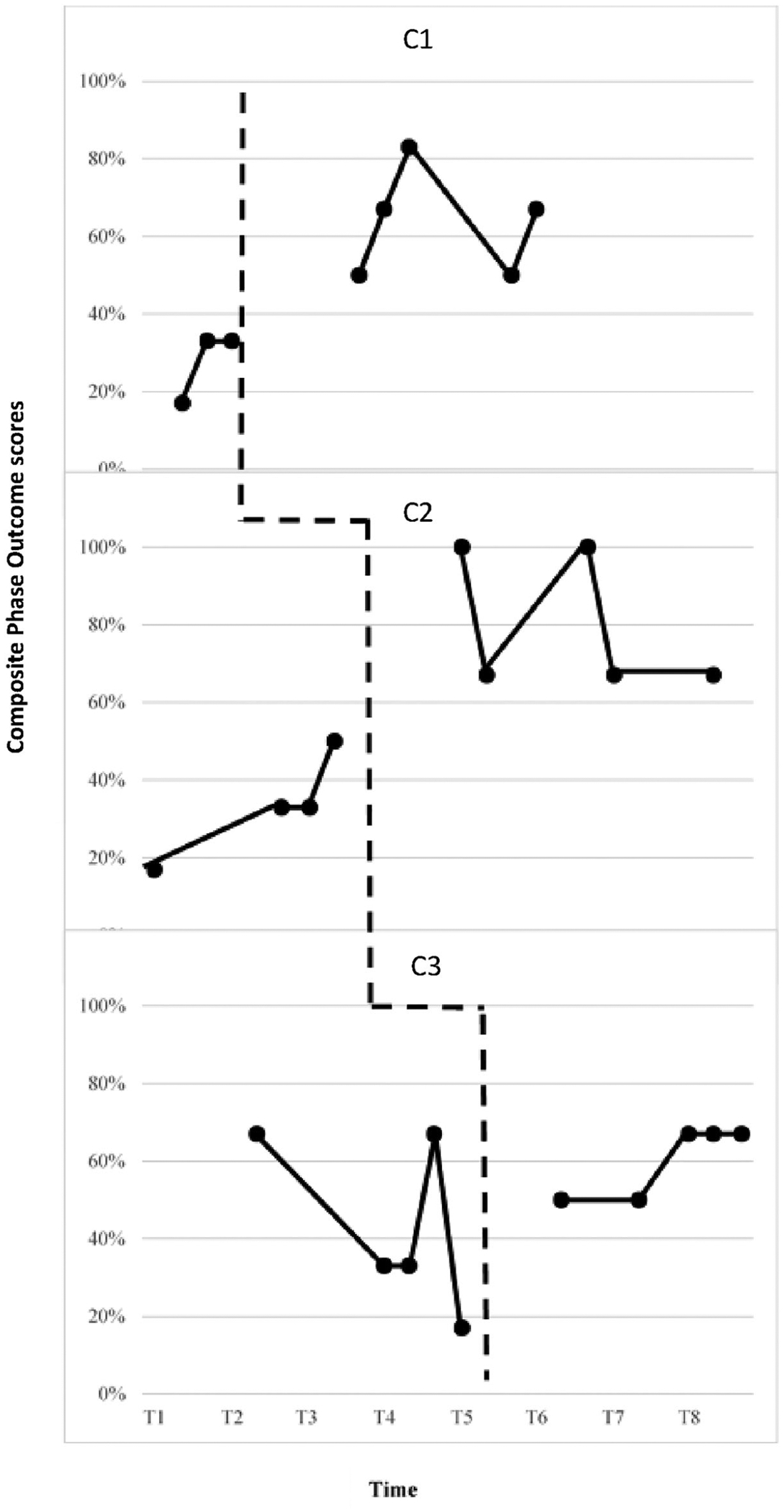

ACIG’s Goal-setting Phase Outcome scale measured whether the eGAS process resulted in clinicians gathering the relevant information for each of the three interview phases by assigning a score of 0–3 for each phase that was converted into a composite percentage score. Figure 3 displays the phase outcome percentage score for each clinician. A moderate functional relation between eGAS and interview phase objectives was shown by: (1) the presence of an immediacy effect, and (2) a level change for the first and second clinicians. No change in level and 100% overlap was noted for the third clinician (C3), however there was reduced variability and consistent maintenance of a positive trend in the data for the intervention compared to the baseline phase. There was an increasing baseline for the second clinician, but this was offset by the level change in Phase B. Tau U score of 0.44 for the third clinician indicated a weak effect. However, Tau U scores of 1 for the remaining two clinicians indicated a strong effect despite the increasing trend in the baseline phase for the second clinician. Table 5 displays Tau U scores, z and p values for each clinician. Weighted average Tau U scores (refer to Table 6) as measured by ACIG’s Goal-setting Phase Outcome scale suggests an overall medium treatment effect across the three tiers on the degree to which clinicians meet the ultimate outcome of each phase of goal-setting.

Figure 3.

ACIG goal-setting phase outcome scale.

Inter-rater Reliability.

Table 7 displays weighted kappa estimates and 95% confidence levels for all measures, calculated using the MedCalc Software (Version 19.0.4) based on linear weights. A trained research assistant analyzed 20% of the audio recordings in each phase (n = 6). Inter-rater reliability was fair for ratings of Level of Client-Centeredness Scale for the Problem Identification, and Treatment Selection interview phases, and good for the GAS Construction interview phase and composite scores (κ ~ 0.30). Inter-rater reliability for the Goal-setting Phase Outcome Scale was moderate for the Problem Identification interview phase (κ = 0.40) and composite scores (κ > 0.48), and good (κ > 0.61) for the Treatment Selection and GAS Construction interview phases. Inter-rater reliability for the TA measure was moderate (κ = 0.50).

Table 7.

Inter-rater reliability of ACIG subscale and composite scores and CIB measures.

| Interviewing phases | k estimates [95% CI: LL, UL] |

|---|---|

| Problem Identification | |

| Client-centeredness | 0.31 [−0.13,0.74] |

| Outcome | 0.40 [−0.14, 0.94] |

| Treatment Selection ** | |

| Client-centeredness | 0.00 |

| Outcome | 0.00 |

| GAS Construction | |

| Client-centeredness | 0.33 [0.05, 0.61] |

| Outcome | 0.65 [0.26, 1.00] |

| ACIG Composite | |

| Client-centeredness | 0.35 [0.15, 0.55] |

| Outcome | 0.48 [0.15, 0.80] |

| CIB Task-analysis | 0.50 [0.25, 0.75] |

| ACIG GAS quality appraisal scale (SMARTED) | 0.71 [0.50, 0.93] |

Note. n = 6.

p < .05.

For the treatment selection phase, 4 out of 6 cases had 100% agreement on outcome (score of 0), while in the remaining 2 cases there was a 1-point difference (RA had a rating of 1, researcher had rating of 0 for both cases). There was 100% agreement on the client-centeredness ratings (score of 0) for the treatment selection phase.

CIB = Clinician Interview Behavior Scale. ACIG = Assessment of Client-centeredness when Interviewing and Goal-setting. CI = Confidence interval. LL = Lower level. UL = Upper level.

Research Question 2: Is there a functional relation between using eGAS and an increase in the validity of the generated scales?

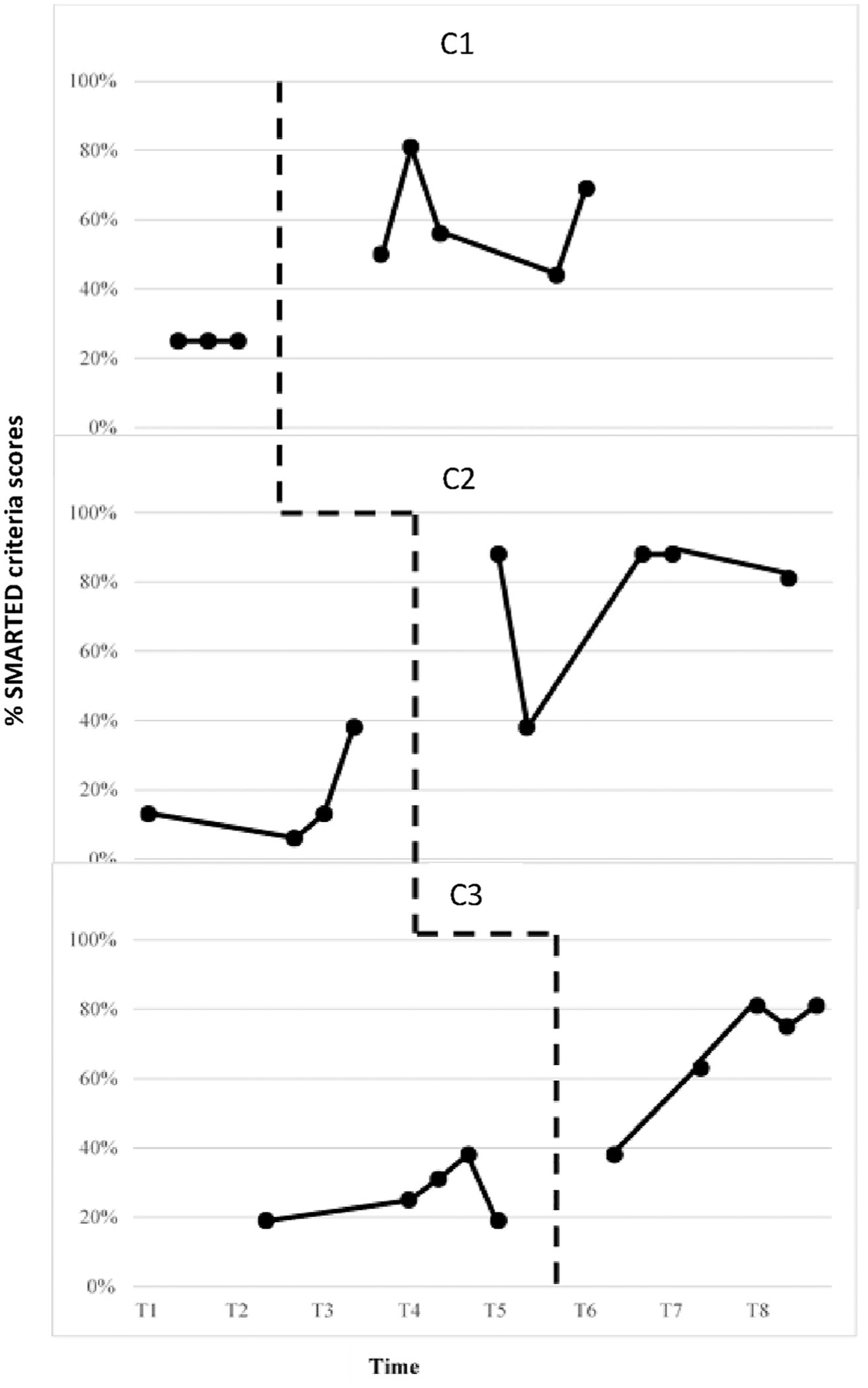

Figure 4 displays the percentage of SMARTED (specific, meaningful, attainable, relevant, time-specific, equidistant, and unidimensional) criteria that each goal attainment scale met for all clinician-client dyads (Krasny-Pacini et al., 2016). A strong functional relation between use of eGAS and goal validity was observed for all clinicians based on: (1) the presence of an immediacy effect from the baseline to experimental phase, (2) an increase in the level from baseline to experimental phase, and (3) an overall increase or maintenance of trend of data in the experimental phase. For clinician 2, C2, the stability of baseline was questionable given the increasing trend of appraisal scores. However, Tau U scores of 1.00, 0.95, and 0.96 suggested the presence of a strong effect. Table 5 displays Tau U scores, z and p values for each clinician. Weighted average Tau U scores (refer to Table 6) as measured by GAS Quality Appraisal scale suggests an overall strong treatment effect across the three tiers on the validity of goal attainment scale.

Figure 4.

GAS quality appraisal scale.

Inter-rater Reliability.

Using the aforementioned procedures, inter-rater reliability was calculated for the GAS Quality Appraisal Scale that rated goals based on SMARTED criteria, Results presented in Table 7 suggested good inter-rater reliability (κ = 0.71) between the researcher and RA for scoring scales based on the SMARTED criteria.

Social validity: Clinician perspective

Table 8 presents items that clinicians rated as 4 or higher on the two TARF-R (Reimers et al., 1992) surveys that gathered clinician perspectives on the eGAS tool and interviewing process. Items evaluating clinician buy-in, tool effectiveness and cost received high ratings on both surveys. Items measuring clinician willingness, reasonableness or acceptability were also highly rated on the survey evaluating clinician perception of eGAS’s process.

Table 8.

Ratings averaged across the treatment acceptability and rating form - revised.

| TARF-R Items | eGAS application | eGAS process | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |

| 1. How clear is your understanding of the eGAS app/procedure?* | 1.33 | 4.00 | 2.33 | 4.33 |

| 2. How acceptable do you find the eGAS app/procedure?* | 3.00 | 4.33 | 3.00 | 4.67 |

| 3. The assessment/interview sessions using eGAS app/procedure will be easy to do for me.* | 3.00 | 4.00 | 3.00 | 4.00 |

| 4. The assessment/interview sessions using eGAS app/procedure will be easy to complete for me.* | 2.67 | 4.00 | 3.00 | 4.00 |

| 5. I believe that eGAS app/procedure will be beneficial to me and my peers.* | 3.33 | 4.67 | 3.67 | 4.67 |

| 6. To what extent do you think there might be disadvantages to using the eGAS app/procedure? | 2.00 | 2.33 | 2.67 | 2.00 |

| 7. How much time will be needed for familiarizing yourself with the eGAS app/procedure before the next session? | 3.00 | 2.33 | 3.33 | 2.67 |

| 8. How confident are you that the eGAS app/procedure will provide an effective technique for engaging in patient-centered communication and goal-setting?* | 3.00 | 4.67 | 3.33 | 4.67 |

| 9. How helpful do you think the eGAS app/procedure will be?* | 3.00 | 4.33 | 3.33 | 4.67 |

| 10. How disruptive will the eGAS app/procedure be? | 3.33 | 2.33 | 2.67 | 1.67 |

| 11. How much do you like the eGAS app/procedure?* | 3.00 | 4.33 | 3.00 | 4.67 |

| 12. How willing would you be to suggest the eGAS app/procedure to others needing assistance?* | 3.33 | 4.33 | 3.00 | 4.67 |

| 13. How much discomfort are you likely to experience while using eGAS app/procedure? | 3.00 | 2.33 | 2.33 | 1.67 |

| 14. How well supported did you feel using the eGAS app/procedure?* | 2.67 | 4.33 | 3.33 | 4.33 |

| 15. How well will carrying out the eGAS app/procedure fit into your existing routine?* | 3.00 | 4.00 | 3.00 | 4.33 |

| 16. How effective will the eGAS app/procedure be in teaching and other clinicians?* | 3.33 | 4.67 | 3.33 | 4.67 |

| 17. How well does the eGAS app/procedure fit to improve your use of research- based strategies to improve patient-centered interviewing and assessment?* | 3.33 | 4.67 | 3.67 | 4.67 |

Note. TARF-R = Treatment Acceptability and Rating Form-Revised. The TARF-R likert scale ranges from 1 to 5, with higher ratings indicating greater acceptability or likability. The values in this table represent the rating averaged across three clinicians.

Indicates items that displayed an increase in scores to a rating of 4 or higher in the post intervention phase.

Table 9 presents clinician responses from the informal interview, organized by the category of study implementation, eGAS app, and training. Responses during the informal interview supported trends found in the TARF-R responses. All three clinicians felt that the feedback and debriefing after the first two sessions in the experimental phase was instrumental in helping them learn and feel confident about the process. Aspects of the eGAS interface that were reported to be helpful included the MI portion with sample verbiage and scripts for conducting the interview, as well the layout for inputting client information. Even though the interface was positively received, 2 out of 3 clinicians noted that the layout could be simplified for use in a session with clients by reducing the scripting content. The role play component of the training was useful to clinicians in learning the app. Two out of three clinicians felt that training needed to more specifically address steps to turn a goal into a scale, and additional examples would have been beneficial.

Table 9.

Informal interview responses.

| Questions | C1 | C2 | C3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study implementation |

|

|

|

| eGAS app |

|

|

|

| Training |

|

|

|

Discussion

To our knowledge this work represents the first experimental evaluation of SLPs response to training and structured support to implement collaborative goal setting in a neurorehabilitation setting. Previous studies using patient-centered goal-setting techniques have ascribed to using techniques such as the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) and GAS to elicit goals in a hospital setting (Rice et al., 2017; Stolee et al., 2012). In these studies, training has been effective in establishing an overarching treatment target or objective, however client-specific factors (e.g., cognitive limitations) (Stolee et al., 2012), variations in delivery and lack of measurable properties (Rice et al., 2017) have been acknowledged as limitations to creating patient-centered goals that serve as valid measures of treatment efficacy. Lack of knowledge and constraints inherent in clinical environments are significant barriers impeding adoption of goal-setting frameworks into practice (Lenzen et al., 2017). Results of this study suggested that is possible to train rehabilitation clinicians to use a tool such as eGAS that prompts the clinician to engage in a semi-structured interview process grounded in MI and GAS to generate client-centric, valid goal attainment scales. We hypothesized that training clinicians to use the eGAS process which provided structure and visual supports to integrate MI and GAS during goal setting conversations would result in an increase in clinicians’ collaborative interviewing behaviors and adherence to an interview phase structure. We also hypothesized that it would improve clinicians’ ability to generate valid goal attainment scales. Overall the data supported the first and third hypotheses and partially supported the second.

Impact on clinician collaborative interviewing behaviors

Results showed that using eGAS resulted in an increase in clinicians’ collaborative interviewing behavior as measured by both the ACIG’s Level of Client-Centeredness Scale and the TA. All three clinicians showed improvements on both of these measures. Post-hoc analyses of behaviors identified by the CIB task analysis and ACIG client-centeredness subscale suggested that for all three clinicians, goal setting conversations moved from a narrow focus on clinicians’ identifying the primary impairments and describing how treatment might help, to identifying client concerns and then constructing a goal attainment scale. Post-hoc analyses of a composite of the behaviors in the Level of Client-Centeredness Scale suggested there may be small positive changes for clinicians with less professional experience. Years of experience may be a relevant factor with more seasoned clinicians benefitting less from being trained in the eGAS process. C2 who had the least amount of professional experience demonstrated the highest gain in percentage of goal-setting behaviors, whereas C1, with the most amount of professional experience demonstrated the lowest gain.

Results indicated that using eGAS improved interview adherence for two out of three clinicians as measured by ACIG’s Goal-setting Phase Outcome Scale that evaluated the degree to which clinicians attained the intended outcome of each eGAS phase. For the third clinician, C3, although results indicated no significant improvements in adherence to the interview phase, reduction in variability and maintenance of an interviewing structure were observed post eGAS training. Deeper analysis of trends in outcome scores by clinician implied that using eGAS resulted in differential improvements that were largely dependent on certain phases of the interview.

Increase in the outcome level score for two phases - the Problem Identification and GAS Construction phases - positively influenced the overall composite reliability score whereas outcome scores of Buy-in and Treatment Selection phases remained relatively unchanged. The Buy-in phase was not required for every client and could therefore be considered an adaptable component of the interview. The Treatment Selection phase is dependent, in part, upon clinicians’ familiarization with a range of different techniques; the categorization and types of treatments listed in the eGAS tool may not have resonated with all clinicians creating less adherence. However, clinician-client dyads did not tend to identify other treatments not listed in eGAS, and it is more likely that enlisting clients in discussions about selection of treatment approach is not common and may require more practice or training.

Setting-specific constraints such as third-party payor regulations mandated how sessions were structured. Inclusion of standardized test scores was necessary for reimbursement which limited the time available for the goal setting interview. It may be that not all components can be addressed in the allotted time.

Impact on clinician ability to generate valid goal attainment scales

Results suggested that using eGAS had a strong impact on clinicians’ ability to generate valid goal attainment scales as measured by the ACIG’s GAS Quality Appraisal Scale and the CIB task analysis, both of which corresponded to the behaviors associated with writing SMARTED goals (Krasny-Pacini et al., 2016). Post-hoc analyses revealed that using eGAS had a large effect on enhancing clinicians’ ability to write unidimensional goal attainment scales associated with a functional goal that was meaningful to individual clients and were comprised of five measurable, equidistant levels.

Informal analysis revealed several factors that appeared to be associated with instances of generating less valid goal attainment scales including client profile and consistency with which the clinician referred to the eGAS app. Goal attainment scales generated with clients who exhibited difficulties in verbal expression (e.g., anomia or extreme verbosity) tended to meet less of the validity criteria. When working with clients who have these profiles, clinicians may need to supplement the collaborative conversation format with additional or alternative techniques. Additionally, one clinician (C3) reported struggling with transitioning from her current mode of identifying an overall goal to scaling a goal that listed levels of progress and felt training lacked exemplars. She may have benefitted from more practice as her goals received uneven validity scores. Lack of consistency in using the app throughout the interview also appeared to influence validity scores. C2 demonstrated the highest compliance in using the features of the app during conversation as indicated by opening and referring to the different components of the app during her client interviews. Her validity scores were noted to be above 80% for a majority of the scales. C1 displayed the greatest inconsistency with active app use, which might explain why she has the lowest validity scores. eGAS app was intended to provide a platform to deliver content crucial to a collaborative interview and provide ongoing prompting. The preliminary study in clinician responsivity to training did not allow systematic evaluation of the utility of eGAS app itself. Future studies may be helpful in identifying the optimal modality and training regimen for increasing clinicians’ ability to collaboratively engage in goal setting interviews that lead to valid goal attainment scales.

Clinician perception of eGAS

Clinicians endorsed the concept and clinical value of the eGAS process. One expected finding was that clinicians rated the process more highly than the app. This trend is not surprising because training emphasized mastery of interview techniques and GAS procedures, not mastery of app usage. Clinicians also reported feeling confident in implementing the process and continuing to use the MI techniques post completion of the study. The two clinicians with lower ratings reported the need for more training and less complexity on the app in the feedback interview. From the standpoint of the clinician as an end-user, eGAS has the potential to be adopted if the setup of the app is less complex and training expands to include multiple opportunities for practice.

Study limitations

Contextual Factors.

Compromises in study validity were a direct result of our goal to conduct a highly ecological study in the natural hospital setting. Implementation science encourages early partnering with stakeholders, particularly clinicians, when evaluating interventions (Sohlberg et al., 2015), which while important, can be challenging. For example, the institution required that the study duration, number of sessions, and training schedules be disclosed in advance which made it difficult to ensure a stable baseline. Another barrier that prevented adherence to the gold standard of conducting a concurrent multiple-baseline design was managing clinicians’ work schedules, professional obligations, with the incoming caseload for scheduling evaluations. Clinicians had varying workdays, work demands that would often require them to work in other units of the hospital, differences in vacation times that did not consistently coincide with times when the hospital had higher census and more flexibility to schedule evaluations. Scheduling of evaluation sessions was largely dependent on clinician and caseload availability, making it impossible for all clinicians to begin the study simultaneously.

For participating clinicians, meeting the demands of the research project conflicted with institutional-level prerogatives. Construction of new offices and introduction of a new electronic medical record (EMR) software were disruptive to participation. SLP offices were in proximity to the workspace under construction and resulting noise levels were a deterrent for the client and clinician to participate in the session. Introduction of the EMR also reduced the amount of time clinicians invested in study-related activities like training and consulting the manual to gain fluency with the process.

Restricting the study to the outpatient department of a research-affiliated hospital precluded the ability to understand barriers and facilitators unique to other settings, such as acute-care or skilled nursing facilities. Although internal validity is bound to be compromised, the naturalistic practice context allowed us to evaluate implementation and uptake in a way that will inform future development of eGAS or other programs promoting client-centered goal setting for neurorehabilitation.

Methodological Factors.

There were several methodological issues due to the preliminary nature of this study and the goal to conduct in a naturalistic setting with working, full time SLPs. Not being able to use a concurrent multiple baseline design reduced the methodological rigor. Further, had we been able to conduct a maintenance phase, we could have evaluated whether or not the eGAS effect was durable when the app was no longer used. Additionally, the study did not allow the identification of the active ingredients of eGAS. It was not possible to dissociate use of the app from the interview and goal setting processes they were designed to promote. In this study, the independent variable was globally defined as “eGAS process use.” It is not clear whether the physical presence of the app is needed once clinicians have internalized the process and do not require access to the reminders and scripts during their interviews.

There were several design and measurement challenges that potentially affected internal and external validity. First, was the limited number of clinicians. More clinicians would enable having more tiers, thereby improving the internal validity of the design. More tiers would mean more opportunities to demonstrate a replication of effect in accordance with recommendations for single subject designs (Tate et al., 2013). Second, a longer intervention phase would bolster the internal validity by facilitating intra-subject replication of an intervention effect. Third, the nature of the research question to evaluate changes in clinician goal setting conversations necessitated using different clients for each data point since a goal setting conversation takes place only once for each client. Having five different clients in the intervention phase thus introduced a confounder whose influence cannot be determined and therefore, is a threat to internal validity. This study provided the initial exploration that allowed individual analyses and encourages future studies to consider group designs that would eliminate this confounder. Fourth, refinement of measurements might have enhanced study validity. A preliminary pilot study provided support for ACIG’s construct validity, but validity or reliability of the CIB task analysis measure was not established prior to study onset. It was assumed that because the CIB largely constituted a behavioral count, pilot validation was not critical.

Future studies should address the above limitations to bolster the internal and external validity. Additionally, altering the design might make it more feasible to conduct in clinical contexts. For example, the training format could be modified to multiple thirty-minute slots with each session focused on one aspect of the app and till clinicians gain complete fluency with that phase. This setup would be conducive to the scheduling constraints of a medical setting while enabling clinicians to receive more practice.

Conclusion

Engaging clients in goal-setting conversations has a positive impact on health outcomes, but such frameworks have yet to be adopted into routine clinical practice (Plant et al., 2016). This study provides preliminary support that it is feasible, relatively efficient and acceptable to train and support hospital-based SLPs working in the field of neurorehabilitation to effectively implement collaborative goal setting interviews to create valid client-centric goal attainment scales using a framework delivered via an app that structures the relevant content and processes. A noteworthy clinical implication is that it is possible to execute collaborative, goal setting with relatively high fidelity despite variations in characteristics of the end-user (clinician experience or client profile), organizational barriers, and professional regulations.

Another important contribution of the project was the design of measures that can be used to validly assess clinician collaborative interviewing for the purpose of goal setting. The ACIG and CIB may have potential to be used in SLP or other allied health graduate training programs as indices of client-centeredness and collaborative interactions. Finally, we hope that this paper will encourage other researchers to validate and evaluate the feasibility and usability of apps or electronic clinical tools as this is key for ultimate adoption and implementation.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health [grant number R03 HD091453-02].

This study was completed in partial fulfillment of the first author’s dissertation and was supported in part by grant R03 HD091453-02 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2020.1838301

References

- Beeson PM, & Robey RR (2006). Evaluating single-subject treatment research: Lessons learned from the aphasia literature. Neuropsychology Review, 16(4), 161–169. 10.1007/s11065-006-9013-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergquist TF, Micklewright JL, Yutsis M, Smigielski JS, Gehl C, & Brown AW (2012). Achievement of client-centred goals by persons with acquired brain injury in comprehensive day treatment is associated with improved functional outcomes. Brain Injury, 26(11), 1307–1314. 10.3109/02699052.2012.706355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertakis KD, & Azari R (2011). Patient-centered care is associated with decreased health care utilization. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 24(3), 229–239. 10.3122/jabfm.2011.03.100170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black SJ, Brock KA, Kennedy G, & Mackenzie M (2010). Is achievement of short-term goals a valid measure of patient progress in inpatient neurological rehabilitation? Clinical Rehabilitation, 24(4), 373–379. 10.1177/0269215509353261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovend’Eerdt TJH, Botell RE, & Wade DT (2009). Writing SMART rehabilitation goals and achieving goal attainment scaling: A practical guide. Clinical Rehabilitation, 23(4), 352–361. 10.1177/0269215508101741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byiers BJ, Reichle J, & Symons FJ (2012). Single-subject experimental design for evidence-based practice. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 21(4), 397–414. 10.1044/1058-0360(2012/11-0036) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaytor N, & Schmitter-Edgecombe M (2003). The ecological validity of neuropsychological tests: A review of the literature on everyday cognitive skills. Neuropsychology Review, 13(4), 181–197. 10.1023/b:nerv.0000009483.91468.fb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicerone KD, Langenbahn DM, Braden C, Malec JF, Kalmar K, Fraas M, Felicetti T, Laatsch L, Harley P, Bergquist T, Azulay J, Cantor J, & Ashman T (2011). Evidence-based cognitive rehabilitation: Updated review of the literature from 2003 through 2008. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 92(4), 519–530. 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Arcy LP, & Rich EC (2012). From comparative effectiveness research to patient centered outcomes research: Policy history and future directions. Neurosurgical Focus, 33(1), E7. 10.3171/2012.4.FOCUS12106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobber J, van Meijel B, Barkhof E, Scholte op Reimer W, Latour C, Peters R, & Linszen D (2015). Selecting an optimal instrument to identify active ingredients of the motivational interviewing-process. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 78(3), 268–276. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doig E, Fleming J, Kuipers P, Cornwell P, & Khan A (2011). Goal-directed outpatient rehabilitation following TBI: A pilot study of programme effectiveness and comparison of outcomes in home and day hospital settings. Brain Injury, 25(11), 1114–1125. 10.3109/02699052.2011.607788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly C, & Carswell A (2002). Individualized outcome measures: A review of the literature. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. Revue Canadienne D’ergotherapie, 69(2), 84–94. 10.1177/000841740206900204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dörfler E, & Kulnik ST (2019). Despite communication and cognitive impairment-person-centred goal-setting after stroke: A qualitative study. Disability and Rehabilitation. Advance online publication. 10.1080/09638288.2019.1604821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant M, & Ponsford J (2014). Goal attainment Scaling in brain injury rehabilitation: Strengths, limitations and recommendations for future applications. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 24(5), 661–677. 10.1080/09602011.2014.901228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey MT, May ME, & Kennedy CH (2004). Nonconcurrent multiple baseline designs and the evaluation of educational systems. Journal of Behavioral Education, 13(4), 267–276. 10.1023/B:JOBE.0000044735.51022.5d [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Horner RH, Carr EG, Halle J, McGee G, Odom S, & Wolery M (2005). The use of single-subject research to identify evidence-based practice in special education. Exceptional Children, 71(2), 165–179. 10.1177/001440290507100203 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jelsma JGM, Mertens VC, Forsberg L, & Forsberg L (2015). How to measure Motivational interviewing fidelity in randomized controlled Trials: Practical recommendations. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 43, 93–99. 10.1016/j.cct.2015.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiresuk T, & Sherman R (1968). Goal attainment Scaling: A general method for evaluating Comprehensive Community Mental health programs. Community Mental Health Journal, 4(6), 443–453. 10.1007/BF01530764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasny-Pacini A, Chevignard M, & Evans J (2014). Goal Management training for rehabilitation of executive functions: A systematic review of effectivness in patients with acquired brain injury. Disability and Rehabilitation, 36(2), 105–116. 10.3109/09638288.2013.777807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasny-Pacini A, Evans J, Sohlberg M, Chevignard M, Hospitals M, & Maurice S (2016). Proposed criteria for appraising goal attainment scales used as outcome measures in rehabilitation. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 97(1), 157–170. 10.1016/j.apmr.2015.08.424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton M, Sage K, Haddock G, Conroy P, & Serrant L (2018). Speech and language therapists’ perspectives of therapeutic alliance construction and maintenance in aphasia rehabilitation post-stroke. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 53(3), 550–563. 10.1111/1460-6984.12368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach E, Cornwell P, Fleming J, & Haines T (2010). Patient centered goal-setting in a sub-acute rehabilitation setting. Disability and Rehabilitation, 32(2), 159–172. 10.3109/09638280903036605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzen SA, Daniëls R, van Bokhoven MA, van der Weijden T, & Beurskens A (2017). Disentangling self-management goal setting and action planning: A scoping review. PLoS One, 12(11), e0188822. 10.1371/journal.pone.0188822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levack W, Mark W, Hay Smith J, Dean S, McPherson K, & Siegert R (2015). Goal setting and strategies to enhance goal pursuit for adults with acquired diasability participating in rehabilitation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 7, 1. 10.1002/14651858.CD009727.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locklear T (2015). Reaching consensus on patient-centered definitions: A report from the Patient-Reported Outcomes PCORnet Task Force. NIH Collaboratory. [Google Scholar]

- Madson MB, & Campbell TC (2006). Measures of fidelity in motivational enhancement: A systematic review. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 31(1), 67–73. 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madson MB, Loignon AC, & Lane C (2009). Training in motivational interviewing: A systematic review. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 36(1), 101–109. 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medley AR, &Powell T(2010).Motivational interviewing topromote self-awareness and engagement in rehabilitation following acquired brain injury: A conceptual review. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 20(4), 481–508. 10.1080/09602010903529610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer SH, & Sterling HE (2012). The impact of baseline trend control on visual analysis of single-case data. Journal of School Psychology, 50(3), 403–419. 10.1016/j.jsp.2011.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, & Rollnick S (2002). Motivational interviewing-second addition. Guildford. [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Rowell LN, Manuel JK, Ernst D, & Houck JM (2016). The motivational interviewing treatment integrity code (MITI 4): Rationale, preliminary reliability and validity. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 65, 36–42. 10.1016/j.jsat.2016.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker RI, Vannest KJ, & Davis JL (2011a). Effect size in single-case research: A review of nine nonoverlap techniques. Behavior Modification, 35(4), 303–322. 10.1177/0145445511399147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker RI, Vannest KJ, Davis JL, & Sauber SB (2011b). Combining nonoverlap and trend for single-case research: Tau-U. Behavior Therapy, 42(2), 284–299. 10.1016/j.beth.2010.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdices M, & Tate RL (2009). Single-subject designs as a tool for evidence-based clinical practice: Are they unrecognised and undervalued? Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 19 (6), 904–927. 10.1080/09602010903040691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plant SE, Tyson SF, Kirk S, & Parsons J (2016). What are the barriers and facilitators to goal-setting during rehabilitation for stroke and other acquired brain injuries? A systematic review and meta-synthesis. Clinical Rehabilitation, 30(9), 921–930. 10.1177/0269215516655856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prescott S, Fleming J, & Doig E (2015). Goal setting approaches and principles used in rehabilitation for people with acquired brain injury: A systematic scoping review. Brain Injury, 29 (13–14), 1515–1529. 10.3109/02699052.2015.1075152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quatrano L. a., & Cruz TH (2011). Future of outcomes measurement: Impact on research in medical rehabilitation and neurologic populations. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 92(10 Suppl.), S7–11. 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.08.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimers TM, Wacker DP, Cooper LJ, & DeRaad AO (1992). Clinical evaluation of the variable.

- Rice DB, McIntyre A, Mirkowski M, Janzen S, Viana R, Britt E, & Teasell R (2017). Patient-Centered goal setting in a hospital-based outpatient Stroke rehabilitation Center. Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 9(9), 856–865. 10.1016/j.pmrj.2016.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosewilliam S, Sintler C, Pandyan AD, Skelton J, & Roskell CA (2016). Is the practice of goal-setting for patients in acute stroke care patient-centred and what factors influence this? A qualitative study. Clinical Rehabilitation, 30(5), 508–519. 10.1177/0269215515584167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabee CM, Koenig CJ, Wingard L, Foster J, Chivers N, Olsher D, & Vandergriff I (2015). The process of interactional sensitivity coding in health care: Conceptually and operationally defining patient-centered communication. Journal of Health Communication, 20(7), 773–782. 10.1080/10810730.2015.1018567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlosser RW (2004). Goal attainment scaling as a clinical measurement technique in communication disorders: A critical review. Journal of Communication Disorders, 37(3), 217–239. 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2003.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JD (2012). Single-case experimental designs: A systematic review of published research and current standards. Psychological Methods, 17(4), 510–550. 10.1037/a0029312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohlberg MM, Kucheria P, Fickas S, & Wade SL (2015). Developing brain injury interventions on both ends of the treatment continuum depends upon early research partnerships and feasibility studies. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 58(6), S1864–S1870. 10.1044/2015_JSLHR-L-15-0150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer K, Paul J, Brown K, Taylor E, & Sohlberg M (2020). Cognitive rehabilitation for individuals with Parkinson’s disease: Development and piloting an external aids treatment program. American Journal Speech Language Hearing, 29(1), 1–19. 10.1044/2019_AJSLP-19-0078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]