Abstract

Establishing a multidisciplinary approach regarding the treatment of spondylodiscitis and analyzing its effect compared to a single discipline approach. 361 patients diagnosed with spondylodiscitis were included in this retrospective pre-post intervention study. The treatment strategy was either established by a single discipline approach (n = 149, year 2003–2011) or by a weekly multidisciplinary infections conference (n = 212, year 2013–2018) consisting of at least an orthopedic surgeon, medical microbiologist, infectious disease specialist and pathologist. Recorded data included the surgical and antibiotic strategy, complications leading to operative revision, recovered microorganisms, as well as the total length of hospital and intensive care unit stay. Compared to a single discipline approach, performing the multidisciplinary infections conference led to significant changes in anti-infective and surgical treatment strategies. Patients discussed in the conference showed significantly reduced days of total antibiotic treatment (66 ± 31 vs 104 ± 31, p < 0.001). Moreover, one stage procedures and open transpedicular screw placement were more frequently performed following multidisciplinary discussions, while there were less involved spinal segments in terms of internal fixation as well as an increased use of intervertebral cages instead of autologous bone graft (p < 0.001). Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis were the most frequently recovered organisms in both patient groups. No significant difference was found comparing inpatient complications between the two groups or the total in-hospital stay. Implementation of a weekly infections conference is an effective approach to introduce multidisciplinarity into spondylodiscitis management. These conferences significantly altered the treatment plan compared to a single discipline approach. Therefore, we highly recommend the implementation to optimize treatment modalities for patients.

Subject terms: Clinical microbiology, Medical research, Health care, Orthopaedics, Infectious diseases

Introduction

Spondylodiscitis, also referred to as vertebral osteomyelitis, is a serious disease with an incidence of 2.2–5.8 per 100.000 and a mortality rate of up to 20%1. Main treatment goals include the elimination of the infection as well as preservation or restoration of spinal stability and neurological function1,2. Due to its complexity, diagnosis and treatment of spondylodiscitis remain very challenging and require a coordinated approach2. Surgical management consists of a wide spectrum of procedures including specimen recovery, debridement of the septic focus, instrumented stabilization, autologous bone graft or cage interposition, vertebral replacement and spinal decompression. Also, the surgical strategies in terms of approach (anterior, posterior or combined), quantity (single-stage or two-stage) and invasiveness (open and percutaneous) need to be defined1–6. Moreover, complicated by the emergence of highly resistant, Gram-positive and –negative organisms, duration and choice of antimicrobials may be challenging. Furthermore, conservative and additional options such as immobilization, bed rest and physical therapy have to be considered in the treatment plan2,7,8. Still, the optimal treatment modalities and their indications are controversial and precise recommendations are lacking1,2,7.

A multidisciplinary approach with involvement of infectious disease specialists to bone and joint infections is a long-standing concept. Recently it has even been stated that orthopedic infectious disease can be considered as subspecialty of its own9,10. Therefore clinical practice guidelines recommend a multidisciplinary approach to spondylodiscitis care that brings together all relevant disciplines to discuss optimal disease management7,11. However, multidisciplinary case conferences have not been introduced or examined in the context of spondylodiscitis so far while being an essential component of cancer care in many countries11–14. Recently, this standardized multidisciplinary approach was introduced in the context of prosthetic joint infections as well13,15. The implementation of these conferences could improve the treatment plan and might even be associated with better clinical outcome and survival12–14. In this study, we retrospectively analyzed patient records to test the hypothesis that the implementation of a multidisciplinary infections conference is an effective approach to significantly improve management of spondylodiscitis.

Patients and Methods

Study setting

Level of Evidence: III

This study was conducted at a large University Medical Center located in central Europe. The hospital is a 1600 bed tertiary care provider hosting in-house departments for medical microbiology and pathology. Patients included were treated in the spine center which is incorporated in the Department of Trauma- and Orthopedic Surgery. All methods were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All experimental protocols were approved by and informed consent was obtained from all subjects according to the Ethics Committee of the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (Hamburg Medical Chamber, Hamburg, study number WF-013/20).

Infections conference

In 2011 multidisciplinary infections conferences were first established at our institution and the standardized setting was as previously described13. Since then the conference is held on a weekly basis. Every patient diagnosed with spondylodiscitis is included in the conference and discussed every week until discharge. The conference is organized and prepared by the department of trauma and orthopedic surgery and always takes place in a same defined meeting room at the same time that allows and simplifies all specialties to participate. Four specialties need to take part in order to validate multidisciplinary decision making: a senior spinal surgeon, a senior pathologist, a senior microbiologist and an infectious disease specialist. Each case was furthermore discussed with a senior radiologist but for organizational reasons in a separate setting. In urgent medical cases the plan was discussed immediately and afterwards included in the conference and reevaluated. Apart from spondylodiscitis, prosthetic joint infections, osteomyelitis, soft tissue infections and osteosynthesis associated infections are discussed in the conference as well but with a senior orthopedic surgeon. The spinal surgeon is in charge of case selection and its presentation, orally and in written form beforehand. The presentation document is standardized and includes patient data, past medical history, risk factors, lab results, date of diagnosis, current treatment modalities, operations, clinical presentation, wound status, current antibiotics and microbiological results, if available. The duties of the pathologist include presentation of the histopathological findings, especially in terms of acute or chronic inflammatory aspects. The microbiologist is responsible for interpretation of microbiological findings, suggests performance of additional microbiological diagnostics if necessary and defines optimal antibiotic regimens. Major case discussion aspects include: type of treatment (operative vs conservative); surgical strategy; type, number and duration of antibiotics used as well as duration of the inpatient and outpatient treatment. After the discussion, the interdisciplinary treatment plan is established and delivered to each physician in charge.

Patient selection

All patients with diagnosed spondylodiscitis (hematogenously or per continuitatem) who were treated at our institution between 2003 and 2018 were included into this retrospective analysis. Cases of postoperative spondylodiscitis were excluded. Spondylodiscitis was defined as previously described by the presence of characteristic radiological changes of the intervertebral disc and adjacent vertebrae in MRI and CT scan as well as typical clinical and laboratory findings indicating an infection (back/neck pain, fever, elevated C-reactive protein and white blood cell count). Microbiological work up included 3–5 five tissue biopsies which were collected either via open surgery or transpedicular approach (10 Gauge Jamshidi needle) as well as two set of blood cultures. Furthermore at least one sample was obtained for histopathological work up16. Every patient included in this study underwent spinal MRI evaluation or if MRI evaluation was not possible due to a cardiac pacemaker, CT with contrast medium or PET- CT Scan were performed instead. Overall 361 patients were identified. Patients were divided into two groups depending on if they were discussed in the infections conference (referred to as group 1; year; 2013–2018 n = 212) or not (referred to as group 2; year 2003–2011; n = 149).

Retrospective analysis

Recorded data included age, sex, ASA score, recovered organisms, anatomic and segmental distribution of the spondylodiscitis, length of hospital and intensive care unit stay as well as therapeutic management (antibiotic and surgical strategy). Surgical data included the number of involved segments, type of screw placement (open and percutaneous), one stage or two stage procedures, as well as the type of anterior spinal fusion (intervertebral cage implantation, autologous iliac crest bone graft, vertebral body replacement, none). To analyze the antibiotic strategy, all systematically active agents were analyzed in terms of Defined Daily Dose (DDD)17, duration of therapy as well as mode of application (orally or intravenously).

Statistical analysis

Mean value, range and standard deviation were calculated for all variables. Significance was tested by two tailed t-test and Pearson´s chi-squared test where appropriate with a p-value of < 0.05 indicating statistical significance. To determine whether significant differences are attributable to the introduction of a multidisciplinary infections conference a multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) was performed. To test for the overall difference among variables, the analysis was performed with group assignment as independent variable and time as covariate indicating a possible development trend in spinal surgery. In this mixed model approach, dichotomous variables were simultaneously included in addition to continuous variables as dependent variables. However, a classic analysis of variance could be conducted as the study includes a sufficiently large number of cases18. All data were analysed using SPSS software version 25.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Ethical approval

Ethical Review Committee Hamburg, Germany; study number: WF-013/20.

Results

A total of 361 patients diagnosed with spondylodiscitis were included in the study. 212 patients were discussed in the infections conference (group I), whereas 149 patients were treated without conference discussion (group II). Patient characteristics are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics, ASA score as well as spinal localization and distribution in both treatment groups. The ASA Score in both groups differed significantly (p < 0.001).

| With infections conference n = 212 | Without infections conference n = 149 | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 65 ± 15 (range: 19—89 years) | 65 ± 15 (range: 25—89 years) |

| Male to Female Ratio | 2:1 | 1.5:1 |

| Mean ASA Score | 3.2 ± 1 | 2.8 ± 0,6 |

| Median ASA Score | 3 (1–4) | 3 (1–5) |

| Localization | ||

| Lumbar | 113 (53%) | 92 (62%)92 (62%) |

| Thoracic | 48 (23%) | 57 (38%) |

| Cervical | 33 (16%) | 0 (0%) |

| Multifocal | 18 (8%) | 0 (0%)0 (0%) |

| Segmental distribution | ||

| Monosegmental | 153 (72%) | 122 (82%) |

| Bisegmental | 32 (15%) | 11%) |

| ≥ Three segments | 27 (13%) | 10 (7%) |

Analysis of recovered organisms revealed S. aureus and S. epidermidis to be the most common causative organisms in both groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Absolute and relative distribution of recovered top four organisms in both groups.

| Distribution of recovered organisms | |

|---|---|

| With infections conference (n = 212) | S. aureus (64; 30%) |

| S. epidermidis (39; 18%) | |

| E. coli (11; 5%) | |

| M. tuberculosis (8; 4%) | |

| Other (62; 29%) | |

| No findings (31; 15%) | |

| Without infections conference (n = 149) | S. epidermidis (36; 24%) |

| S. aureus (30; 20%) | |

| E. coli (10; 7%) | |

| M. tuberculosis (8; 5%) | |

| Other (76; 51%) | |

| No findings (17; 11%) |

Focusing on a potential change in treatment plan, we analyzed the different surgical procedures performed. Whereas 70% of the patients, discussed in the infections conference, underwent a one stage strategy, only 48% were treated with this strategy when the decision was made by a single discipline approach (Table 3, p = 0.001). In group I, pedicle screws were mostly placed in an open manner (80%). In contrast, in over 50% of the patients of group II the screws were inserted percutaneously (Table 3, p < 0.001). The type and technique of spinal fusion differed significantly between the two groups (Table 3). In group I, most patients were treated with a cage interponat (44%). In contrast, only 7% of the patients in group II received a spinal cage implantation. Instead, the most common choice in group II was the implantation of an iliac crest autologous bone graft (64%) compared to 23% in group I (Table 3). Unplanned operative revision due to complications (impairment of wound healing, screw displacement, relevant postoperative hematoma, neurological deficit) was similar in both groups (group I 20%, group II 19%, p = 0.809).

Table 3.

Surgical strategy and techniques in both groups.

| Type of surgery | With infections conference | Without infections conference | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical strategy | |||

| One stage | 131/188 (70%) | 67/141 (48%) | 0.001 |

| Two stage | 57/188 (30%) | 74/141 (52%) | 0.001 |

| Mean number of operated segments | |||

| Stabilization | 2.7 ± 1.8 | 3.7 ± 1.7 | < 0.001 |

| Decompression | 1.1 ± 1.2 | 1.1 ± 0.9 | 0.84 |

| Transpedicular screw placement | |||

| Open | 144/161 (89%) | 73/148 (49%) | < 0.001 |

| Percutaneous | 17/ 161 (11%) | 75/148 (51%) | < 0.001 |

| Type of anterior spinal fusion | |||

| Titanium or polyetheretherketone cage (PEEK) | 82/188 (44%) | 7/144 (5%) | < 0.001 |

| Autologous bone graft (iliac crest) | 43/188 (23%) | 92/144 (64%) | < 0.001 |

| Vertebral body replacement | 24/188 (13%) | 10/144 (7%) | 0.083 |

| No interponate | 49/188 (26%) | 35/144 (24%) | 0.71 |

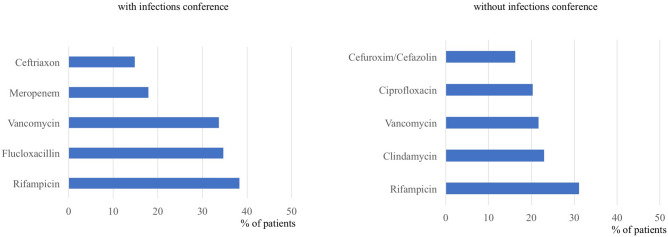

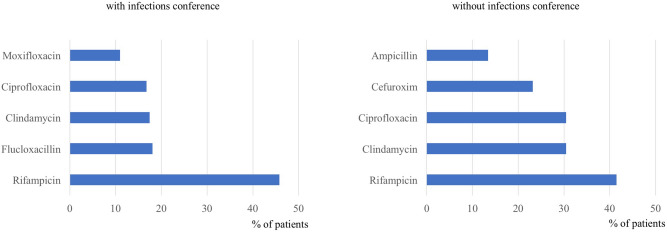

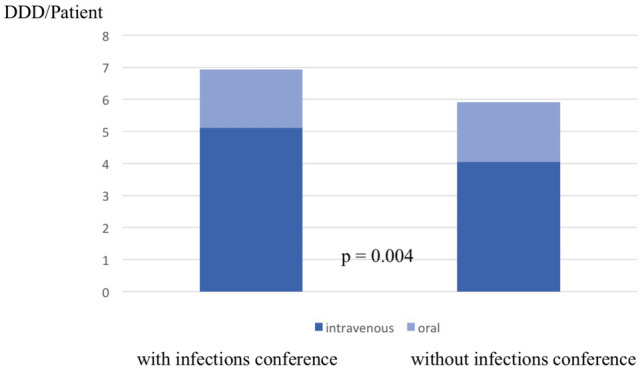

Overall (orally and intravenously), group I showed a significant shorter duration of antibiotic treatment (group I 66 d ± 31, group II 104 d ± 31, p < 0.001, Table 4). Further analysis focusing on the mode of application revealed a significantly longer intravenous therapy in group I compared to group II (Table 4). Analysis of the DDD values in both groups revealed a significant increase in the infections conference group (Fig. 1, p = 0.004). Regarding the type of antibiotics, Rifampicin was the most frequently used antibiotic in both groups for oral and intravenous therapy. In contrast to group II, the narrow spectrum beta-lactam antibiotic Flucloxacillin was frequently used if the decision was made by the multidisciplinary conference (Figs. 2 and 3).

Table 4.

Mean duration in days of intravenous, oral and total antibiotic therapy. Due to its prolonged therapy, M. tuberculosis spondylodiscitis is not respected in this analysis.

| With infections conference | Without infections conference | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intravenous antibiotic therapy | 26 ± 19 | 18 ± 8 | < 0.001 |

| Oral antibiotic therapy | 40 ± 33 | 87 ± 25 | < 0.001 |

| Total antibiotic therapy | 66 ± 31 | 104 ± 31 | < 0.001 |

Figure 1.

Defined Daily Dose per patient in both groups and subcategorization according to the application method. Number of patients included: 96 (without infections conference), 203 (with infections conference).

Figure 2.

Relative distribution of top five intravenous antibiotics used in both groups. Number of patients included: 74 (without infections conference), 196 (with infections conference).

Figure 3.

Relative distribution of top five oral antibiotics used in both groups. Number of patients included: 82 (without infections conference), 155 (with infections conference).

Comparing the total length of hospital stay between the two groups did not reveal a significant difference with a mean length of 27 days (Group I) and 31 days (Group II) retrospectively (p = 0.1). Still, patients who were treated according to a plan established by the infections conference (Group I) had a significantly (p = 0.003) longer stay on the ICU (Table 5).

Table 5.

Mean length and standard deviation of total hospital stay in days as well as mean length and standard deviation in days of intensive care unit treatment.

| With infections conference (n = 212) | Without infections conference (n = 149) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean length of hospital stay | 27 ± 21 | 31 ± 22 | 0.1 |

| Mean length of ICU stay | 7 ± 15 | 3 ± 9 | 0.003 |

The results of MANCOVA indicate that the main effect of the multidisciplinary infections conference was significant (F = 5.11, p < 0.001). The implementation had an independent significant impact on length of ICU stay (F = 4.62, p = 0.033), total days of oral (F = 15.99, p < 0.001), intravenous antibiotic therapy (F = 6.17, p = 0.014) and transpedicular screw placement (F = 23.06, p < 0.001) controlled for the variable time. There is also a trend that the surgical procedure (one-stage vs. two stage) could be influenced by the multidisciplinary conference (F = 3.67, p = 0.057). Differences in type of anterior spinal fusion cannot be attributed to the implemented conference. Instead, the main effect of the covariate was also significant (F = 2.31, p = 0.022), indicating that time exclusively had a significant effect on the change in use of a cage interponat (F = 20.33, p < 0.001) and iliac crest autologous bone graft (F = 4.63, p = 0.033) as type of anterior spinal fusion.

Discussion

This study demonstrates the successful implementation of a weekly infections conference in the treatment of spondylodiscitis.

In the context of cancer care, multidisciplinary conferences are already a fundamental practice and these conferences can be linked to a change in treatment plan as well as improved patient outcome and survival19–22. Therefore, the here reported infections conference was established in a similar manner with weekly frequency, as reported in the majority of the reported studies in the literature12,14,23,24. Due to the attendance of at least a spinal surgeon, a microbiologist, an infectious disease specialist and a pathologist as well as the additional discussion with a radiologist, the key specialties needed in the management of spondylodiscitis are all closely involved in the treatment plan.

Similar to multidisciplinary cancer conferences our results show that performing these discussions led to a significant alteration in the treatment plan, displayed by a different surgical and antibiotic regimen. Patients in the infections conference group received a significantly shorter duration of antibiotic treatment, which was furthermore strengthened by a multivariate analysis emphasizing the impact of the conferences. The results are in accordance to the recent opinion that a shorter period of antibiotic treatment (mostly 6 weeks) is not inferior to a longer application duration (mostly 12 weeks) and reflects the current guidelines of the Infections Disease Society of America11,25–27. Establishing these conferences could therefore be a useful instrument to secure adherence to guidelines, as numerous studies have demonstrated improved guideline adherence due to the implementation of multidisciplinary cancer conferences22,23,28,29. Limiting the duration of antibiotic therapy to a shorter but equally effective course may further the goal of reducing side effects in the individual patient and reducing overall antibiotic consumption, thus reducing the development and selection of drug resistant bacteria30–32. Interestingly, the intravenous treatment duration was significantly increased in the infections conference group, which could be explained by the prolonged intensive care unit stay and higher ASA Scores of patients in this group. However, compared to most other studies the duration of intravenous therapy in both groups of this study is comparatively low11,33–35. Furthermore, potentially improved bioavailability might influence the slight increase of duration as well, especially when taking the limited bone penetration of most antibiotics and the prolonged bone revascularization after surgery into consideration. Moreover, the increased rate of S. aureus in the conference group could be another explanation since S. aureus infections are thought to be associated with higher complications so that prolonged intravenous therapy could be essential1,36–39. Still, it needs to be considered that there is a lack of data supporting its efficacy and recent research questions the superiority of intravenous compared to oral antibiotic treatment but not in the specific context of spondylodiscitis11,40–42. Even though several surgical and instrumentation techniques to treat spondylodiscitis have been described, valid recommendations are few and there is no consensus about the optimal surgical strategy. The multidisciplinary conference is a tool to strengthen a standardized approach while also respecting the heterogeneous and individual nature of this disease. Even though we could detect significant alterations regarding the surgical management, multivariate analysis revealed that only certain aspects can be attributed to the conference. It has to be considered, that surgical strategies as well as implants have changed over the years, so that it is to be expected that the recorded differences cannot just be ascribed to the conference discussion. In this study, the alterations in the surgical strategy which can be associated to the conference by multivariate analysis were the type of screw placement as well as an almost significant trend towards one-stage procedures. Whereas the type of anterior spinal fusion could not be attributed to the implemented conference.

A potential change in treatment plan due to these conferences is one of the most valuable arguments in favor of conducting these conferences which is supported by these results14,23. Still, even though therapeutic changes could be demonstrated in this study we could not detect any changes regarding complications leading to operative revision or when it comes to the total length of hospital stay, as previously reported in other studies13,14. Therefore, a change in clinical outcome could not be shown in this study.

Additionally, following implementation of the infections conferences, it was noticeable that they were an efficient tool to accelerate the process of multimodal decision making, which both the patient and the staff benefitted from. Especially complex medical decisions which rely on fundamental knowledge in various fields can be quite time consuming for hospital staff. Consulting physicians might not be readily available and it can be an administrative challenge to gather all information and implement the expert opinions of various people. With all fields of expertise gathered at the weekly conferences, complex decisions could be efficiently and profoundly made.

The limitations of the study include its retrospective nature and a lack of randomization. Also, the different distribution of spinal localization and different ASA scores in the two groups lead to a potential bias. It needs to be recognized that, according to multivariate analysis, not all significant results could be attributed to the introduction of the conference. The results of our study do not allow to comment on prognostic outcome and need to be carefully interpreted.

In conclusion, due to the successful implementation of a multidisciplinary infections conference our study demonstrates a feasible and effective solution to ensure the multidisciplinary approach in spondylodiscitis care. Performing these conferences significantly alters the treatment plan when compared to a single discipline approach and is a helpful tool to increase the efficiency of multidisciplinary decision making. Prospective studies are warranted in order to examine the conference´s effect on clinical outcome.

Author contributions

All authors assisted in drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content. Additionally, they approved the final version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. DN substantial contribution to the conception and design of the work, substantial contribution to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, wrote the better part of the manuscript. BS substantial contribution to the conception and design of the work, substantial contribution to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data. DMT substantial contribution to the conception and design of the work, substantial contribution to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data. LV substantial contribution to the conception and design of the work, substantial contribution to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data. HK substantial contribution to the conception and design of the work, substantial contribution to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data. HR substantial contribution to the conception and design of the work, substantial contribution to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, supervision of the project. AB substantial contribution to the conception and design of the work, substantial contribution to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, constant board member. AL substantial contribution to the conception and design of the work, constant board member. AS substantial contribution to the design of the work, analysis and interpretation of data, writing parts of the manuscript. MD substantial contribution to the conception and design of the work, substantial contribution to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, supervision of the project. MS substantial contribution to the conception and design of the work, substantial contribution to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, supervision of the project.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. No funding was received for this study.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Herren C, et al. Spondylodiscitis: diagnosis and treatment options. Dtsch. Arzteblatt Int. 2017;114:875–882. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2017.0875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mavrogenis AF, et al. Spondylodiscitis revisited. EFORT Open Rev. 2017;2:447–461. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.2.160062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gregori F, et al. Treatment algorithm for spontaneous spinal infections: A review of the literature. J. Craniovertebral Junction Spine. 2019;10:3–9. doi: 10.4103/jcvjs.JCVJS_115_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zarghooni K, Röllinghoff M, Sobottke R, Eysel P. Treatment of spondylodiscitis. Int. Orthop. 2012;36:405–411. doi: 10.1007/s00264-011-1425-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dimar JR, et al. Treatment of pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis with anterior debridement and fusion followed by delayed posterior spinal fusion. Spine. 2004;29:326–332. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000109410.46538.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fayazi A. Preliminary results of staged anterior debridement and reconstruction using titanium mesh cages in the treatment of thoracolumbar vertebral osteomyelitis*1. Spine J. 2004;4:388–395. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pola E, et al. Multidisciplinary management of pyogenic spondylodiscitis: epidemiological and clinical features, prognostic factors and long-term outcomes in 207 patients. Eur. Spine J. Off. Publ. Eur. Spine Soc. Eur. Spinal Deform Soc. Eur. Sect. Cerv. Spine Res. Soc. 2018;27:229–236. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5598-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ascione T, et al. Clinical and microbiological outcomes in haematogenous spondylodiscitis treated conservatively. Eur. Spine J. Off. Publ. Eur. Spine Soc. Eur. Spinal Deform Soc. Eur. Sect. Cerv. Spine Res. Soc. 2017;26:489–495. doi: 10.1007/s00586-017-5036-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hedström SÅ. Collaboration between orthopaedic surgeons and infection specialists in bone and joint infections. J. Bone Jt. Infect. 2019;4:292–294. doi: 10.7150/jbji.41662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vasoo S, Chan M, Sendi P, Berbari E. The value of ortho-id teams in treating bone and joint infections. J. Bone Jt. Infect. 2019;4:295–299. doi: 10.7150/jbji.41663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berbari EF, et al. 2015 Infectious diseases society of america (IDSA) clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of native vertebral osteomyelitis in adults. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2015;61:e26–46. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wright FC, De Vito C, Langer B, Hunter A. Expert panel on multidisciplinary cancer conference standards multidisciplinary cancer conferences: a systematic review and development of practice standards. Eur. J. Cancer Oxf. Engl. 2007;43:1002–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ntalos D, et al. Implementation of a multidisciplinary infections conference affects the treatment plan in prosthetic joint infections of the hip: a retrospective study. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2019;139:467–473. doi: 10.1007/s00402-018-3079-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shao, J., Rodrigues, M., Corter, A. L. & Baxter, N. N. Multidisciplinary care of breast cancer patients: a scoping review of multidisciplinary styles, processes, and outcomes. Curr. Oncol.26, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Karczewski D, et al. A standardized interdisciplinary algorithm for the treatment of prosthetic joint infections. Bone Jt. J. 2019;101B:132–139. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.101B2.BJJ-2018-1056.R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stangenberg M, et al. Impact of the localization on disease course and clinical management in spondylodiscitis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;99:122–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization (WHO). Definition and general considerations of defined daily dose (DDD). http://www.whocc.no/ddd/definition_and_general_considera/Accessed (2020).

- 18.Lunney GH. Using analysis of variance with a dichotomous dependent variable: an empirical study. J. Educ. Meas. 1970;7:263–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-3984.1970.tb00727.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foster TJ, Bouchard-Fortier A, Olivotto IA, Quan ML. Effect of multidisciplinary case conferences on physician decision making: breast diagnostic rounds. Cureus. 2016;8:e895. doi: 10.7759/cureus.895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El Saghir NS, Keating NL, Carlson RW, Khoury KE, Fallowfield L. Tumor boards: optimizing the structure and improving efficiency of multidisciplinary management of patients with cancer worldwide. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol Educ. Book Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Meet. 2014 doi: 10.14694/EdBook_AM.2014.34.e461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sundi D, et al. Establishment of a new prostate cancer multidisciplinary clinic: Format and initial experience. Prostate. 2015;75:191–199. doi: 10.1002/pros.22904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelly SL, Jackson JE, Hickey BE, Szallasi FG, Bond CA. Multidisciplinary clinic care improves adherence to best practice in head and neck cancer. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2013;34:57–60. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2012.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Croke JM, El-Sayed S. Multidisciplinary management of cancer patients: chasing a shadow or real value? An overview of the literature. Curr. Oncol. Tor. Ont. 2012;19:e232–238. doi: 10.3747/co.19.944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keating NL, et al. Tumor boards and the quality of cancer care. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2013;105:113–121. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bernard L, et al. Antibiotic treatment for 6 weeks versus 12 weeks in patients with pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis: an open-label, non-inferiority, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2015;385:875–882. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61233-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flury & Flury. Is switching to an oral antibiotic regimen safe after 2 weeks of intravenous treatment for primary bacterial vertebral osteomyelitis? 14: 226, (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Roblot F, et al. Optimal duration of antibiotic therapy in vertebral osteomyelitis. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;36:269–277. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farrugia DJ, Fischer TD, Delitto D, Spiguel LRP, Shaw CM. Improved breast cancer care quality metrics after implementation of a standardized tumor board documentation template. J. Oncol. Pract. 2015;11:421–423. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.003988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.English R, et al. Factors influencing implementation of decisions made within a multi-disciplinary breast team. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. EJSO. 2009;35:1235. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2009.07.128. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goossens H, Ferech M, Vander Stichele R, Elseviers M. Outpatient antibiotic use in Europe and association with resistance: a cross-national database study. The Lancet. 2005;365:579–587. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17907-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goossens H, Sprenger MJW. Community acquired infections and bacterial resistance. BMJ. 1998;317:654–657. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7159.654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Onorato L, et al. The effect of an antimicrobial stewardship programme in two intensive care units of a teaching hospital: an interrupted time series analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Legrand E, et al. Management of nontuberculous infectious discitis. Treatments used in 110 patients admitted to 12 teaching hospitals in France. Joint Bone Spine. 2001;68:504–509. doi: 10.1016/S1297-319X(01)00315-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bettini N, Girardo M, Dema E, Cervellati S. Evaluation of conservative treatment of non specific spondylodiscitis. Eur. Spine J. 2009;18:143–150. doi: 10.1007/s00586-009-0979-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McHenry MC, Easley KA, Locker GA. Vertebral osteomyelitis: long-term outcome for 253 patients from 7 cleveland-area hospitals. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002;34:1342–1350. doi: 10.1086/340102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mulleman D, et al. Streptococcal and enterococcal spondylodiscitis (vertebral osteomyelitis) High incidence of infective endocarditis in 50 cases. J. Rheumatol. 2006;33:91–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Loibl M, et al. Outcome-related co-factors in 105 cases of vertebral osteomyelitis in a tertiary care hospital. Infection. 2014;42:503–510. doi: 10.1007/s15010-013-0582-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jensen AG, Espersen F, Skinhøj P, Frimodt-Møller N. Bacteremic staphylococcus aureus spondylitis. Arch. Intern. Med. 1998;158:509. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.5.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rutges JPHJ, Kempen DH, van Dijk M, Oner FC. Outcome of conservative and surgical treatment of pyogenic spondylodiscitis: a systematic literature review. Eur. Spine J. Off. Publ. Eur. Spine Soc. Eur. Spinal Deform Soc. Eur. Sect. Cerv. Spine Res. Soc. 2016;25:983–999. doi: 10.1007/s00586-015-4318-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li H-K, et al. Oral versus intravenous antibiotics for bone and joint infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019;380:425–436. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1710926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li HK, Agweyu A, English M, Bejon P. An unsupported preference for intravenous antibiotics. PLOS Med. 2015;12:e1001825. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Daver NG, et al. Oral step-down therapy is comparable to intravenous therapy for Staphylococcus aureus osteomyelitis. J. Infect. 2007;54:539–544. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.