Abstract

Background

Critical care telemedicine (CCT) has long been advocated for enabling access to scarce critical care expertise in geographically‐distant areas. Additional advantages of CCT include the potential for reduced variability in treatment and care through clinical decision support enabled by the analysis of large data sets and the use of predictive tools. Evidence points to health systems investing in telemedicine appearing better prepared to respond to sudden increases in demand, such as during pandemics. However, challenges with how new technologies such as CCT are implemented still remain, and must be carefully considered.

Objectives

This synthesis links to and complements another Cochrane Review assessing the effects of interactive telemedicine in healthcare, by examining the implementation of telemedicine specifically in critical care. Our aim was to identify, appraise and synthesise qualitative research evidence on healthcare stakeholders’ perceptions and experiences of factors affecting the implementation of CCT, and to identify factors that are more likely to ensure successful implementation of CCT for subsequent consideration and assessment in telemedicine effectiveness reviews.

Search methods

We searched MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, and Web of Science for eligible studies from inception to 14 October 2019; alongside 'grey' and other literature searches. There were no language, date or geographic restrictions.

Selection criteria

We included studies that used qualitative methods for data collection and analysis. Studies included views from healthcare stakeholders including bedside and CCT hub critical care personnel, as well as administrative, technical, information technology, and managerial staff, and family members.

Data collection and analysis

We extracted data using a predetermined extraction sheet. We used the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) qualitative checklist to assess the methodological rigour of individual studies. We followed the Best‐fit framework approach using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) to inform our data synthesis. We classified additional themes not captured by CFIR under a separate theme. We used the GRADE CERQual approach to assess confidence in the findings.

Main results

We found 13 relevant studies. Twelve were from the USA and one was from Canada. Where we judged the North American focus of the studies to be a concern for a finding’s relevance, we have reflected this in our assessment of confidence in the finding. The studies explored the views and experiences of bedside and hub critical care personnel; administrative, technical, information technology, and managerial staff; and family members. The intensive care units (ICUs) were from tertiary hospitals in urban and rural areas.

We identified several factors that could influence the implementation of CCT. We had high confidence in the following findings:

Hospital staff and family members described several advantages of CCT. Bedside and hub staff strongly believed that the main advantage of CCT was having access to experts when bedside physicians were not available. Families also valued having access to critical care experts. In addition, hospital staff described how CCT could support clinical decision‐making and mentoring of junior staff.

Hospital staff greatly valued the nature and quality of social networks between the bedside and CCT hub teams. Key issues for them were trust, acceptance, teamness, familiarity and effective communication between the two teams.

Interactions between some bedside and CCT hub staff were featured with tension, frustration and conflict. Staff on both sides commonly described disrespect of their expertise, resistance and animosity.

Hospital staff thought it was important to promote and offer training in the use of CCT before its implementation. This included rehearsing every step in the process, offering staff opportunities to ask questions and disseminating learning resources. Some also complained that experienced staff were taken away from bedside care and re‐allocated to the CCT hub team.

Hospital staff's attitudes towards, knowledge about and value placed on CCT influenced acceptance of CCT. Staff were positive towards CCT because of its several advantages. But some were concerned that the CCT hub staff were not able to understand the patient’s situation through the camera. Some were also concerned about confidentiality of patient data.

We also identified other factors that could influence the implementation of CCT, although our confidence in these findings is moderate or low. These factors included the extent to which telemedicine software was adaptable to local needs, and hub staff were aware of local norms; concerns about additional administrative work and cost; patients' and families’ desire to stay close to their local community; the type of hospital setting; the extent to which there was support from senior leadership; staff access to information about policies and procedures; individuals' stage of change; staff motivation, competence and values; clear strategies for staff engagement; feedback about progress; and the impact of CCT on staffing levels.

Authors' conclusions

Our review identified several factors that could influence the acceptance and use of telemedicine in critical care. These include the value that hospital staff and family members place on having access to critical care experts, staff access to sufficient training, and the extent to which healthcare providers at the bedside and the critical care experts supporting them from a distance acknowledge and respect each other’s expertise. Further research, especially in contexts other than North America, with different cultures, norms and practices will strengthen the evidence base for the implementation of CCT internationally and our confidence in these findings. Implementation of CCT appears to be growing in importance in the context of global pandemic management, especially in countries with wide geographical dispersion and limited access to critical care expertise. For successful implementation, policymakers and other stakeholders should consider pre‐empting and addressing factors that may affect implementation, including strengthening teamness between bedside and hub teams; engaging and supporting frontline staff; training ICU clinicians on the use of CCT prior to its implementation; and ensuring staff have access to information and knowledge about when, why and how to use CCT for maximum benefit.

Plain language summary

What are healthcare stakeholders’ perceptions and experiences of factors affecting the implementation of critical care telemedicine?

What is the aim of this review?

The aim of this review was to identify factors that affect the acceptance and use of health care from a distance (known as telemedicine) for patients in intensive care units (also known as critical care). To answer this question, we searched for and analysed qualitative studies about the perceptions and experiences of clinical staff, managers and administrators, as well as patients and family members. This review links to another Cochrane Review assessing the effects of telemedicine.

Key messages

Our review identified several factors that could influence the acceptance and use of telemedicine in critical care. These included the value that hospital staff and family members place on having access to critical care experts, staff access to sufficient training, and the extent to which healthcare providers at the bedside and the critical care experts supporting them from a distance acknowledge and respect each other’s expertise.

What was studied in this synthesis?

In critical care telemedicine (CCT), patients in intensive care units (ICUs) are monitored by critical care experts based at a ‘hub’ outside the hospital. By monitoring patients, hub staff are able to warn staff at the bedside of potential problems and offer them decision support. The use of CCT means that patients and staff in rural or small hospitals have access to critical care experts. But there may still be challenges when implementing CCT. In this review, we assessed studies that looked at the perceptions and experiences of healthcare workers, family members and others to find factors that could influence the acceptance and use of CCT.

What are the main findings of the synthesis?

We included 13 relevant studies. Twelve were from the USA and one was from Canada. Where we judged the North American focus of the studies to be a concern for a finding’s relevance, we have reflected this in our assessment of confidence in the finding. The studies explored the views and experiences of bedside and hub critical care personnel; administrative, technical, information technology, and managerial staff, and family members. The ICUs were from hospitals in both urban and rural areas.

We identified several factors that could influence the acceptance and use of CCT. We had high confidence in the following findings:

Hospital staff and family members described several advantages of CCT. Bedside and hub staff strongly believed that the main advantage of CCT was having access to experts when bedside doctors were not available. Families also valued having access to critical care experts. Hospital staff also described how CCT could support clinical decision‐making and mentoring of junior staff.

Hospital staff greatly valued the nature and quality of social networks between the bedside and CCT hub teams. Key issues for them were trust, acceptance, being part of a team, familiarity and effective communication between the two teams.

Interactions between some bedside and CCT hub staff were featured with tension, frustration and conflict. Staff on both sides commonly described disrespect of expertise, resistance and animosity.

Hospital staff thought it was important to promote and offer training in the use of CCT before its implementation. This included rehearsing every step in the process, offering staff opportunities to ask questions and disseminating learning resources. Some also complained that experienced staff were taken away from bedside care and re‐allocated to the CCT hub team.

Hospital staff's attitudes towards, knowledge about and value placed on CCT influenced acceptance of CCT. Staff were positive towards CCT because of its several advantages. But some were concerned that the hub staff were not able to understand the patient’s situation through the camera. Some were also concerned about confidentiality of patient data.

We also identified other factors that could influence the acceptance and use of CCT, although our confidence in these findings is moderate or low. These factors include the extent to which telemedicine software was adaptable to local needs, and hub staff were aware of local norms; concerns about additional administrative work and cost; patients' and families’ desire to stay close to their local community; the type of hospital setting; the extent to which there was support from senior leadership; staff access to information about policies and procedures; individuals' readiness to change; staff motivation, competence and values; clear strategies for staff engagement; feedback about progress; and the impact of CCT on staffing levels.

How up‐to‐date is this review?

We searched for studies that had been published up to October 2019.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Summary of qualitative findings.

| Summary of review findings | Studies contributing to the review finding | GRADE‐CERQual assessment of confidence in the evidence | Explanation of GRADE‐CERQual assessment |

| CFIR Domain I: Factors affecting implementation related to intervention characteristics | |||

| Finding 1: Hospital staff’s personal experience, and anecdotes from colleagues, supported their belief that CCT has positive effects on patient care. Specifically, these effects were for patient safety and quality of care, support at the bedside by critical care experts, and standardisation of practice | Khunlertkit 2013; Moeckli 2013; Shahpori 2011a; Stafford 2008a; Ward 2015; Wilkes 2016 | Moderate confidence | Downgraded to moderate confidence because of minor concerns about methodological limitations, coherence, and adequacy; and moderate concerns about relevance |

| Finding 2: Hospital staff and family members described several advantages of CCT. Bedside and hub staff strongly believed that the main advantage of CCT was having access to experts when bedside doctors were not available. Families also valued having access to critical care experts. In addition, hospital staff described how CCT could support clinical decision‐making and mentoring of junior staff | Jahrsdoerfer 2013; Kahn 2019; Khunlertkit 2013; Moeckli 2013; Shahpori 2011a; Stafford 2008a; Thomas 2017 | High confidence | Graded as high confidence because of no or very minor concerns about methodological limitations, relevance, coherence, and adequacy |

| Finding 3: Bedside staff valued the potential adaptability of CCT to speak to local needs and practices. However, this was not always evident, with reported examples being mainly around developing camera usage etiquette and integration with local protocols | Moeckli 2013; Stafford 2008a; Thomas 2017 | Low confidence | Downgraded to low confidence because of minor concerns about coherence; moderate concerns about relevance; and serious concerns about adequacy |

| Finding 4: Both bedside and hub clinicians expressed difficulties with the implementation of CCT. Key barriers related to implementation were perceptions of additional workload, need for more co‐ordination work, and concern around the presence of cameras | Moeckli 2013; Mullen‐Fortino 2012; Shahpori 2011a; Stafford 2008a; Ward 2015 | Moderate confidence | Downgraded to moderate confidence because of minor concerns about coherence; moderate concerns about methodological limitations; and moderate concerns about adequacy |

| Finding 5: Cost considerations featured as an influencing factor in a limited way, with only a few examples noting the high cost of implementing CCT, especially compared to the cost of recruiting additional ICU staff | Shahpori 2011a; Stafford 2008a | Low confidence | Downgraded to low confIdence because of moderate concerns about methodological limitations; and serious concerns about relevance, and adequacy |

| CFIR Domain II: Factors affecting implementation related to outer setting | |||

| Finding 6: Hospital staff as well as family members perceived CCT to be providing a community benefit, specifically for patients' and families' desire to stay close to their local community without requiring transfer to specialist centres to access critical care expertise | Goedken 2017; Moeckli 2013; Shahpori 2011a; Ward 2015; Wilkes 2016 | Moderate confidence | Downgraded to moderate confidence because of minor concerns about adequacy; moderate concerns about methodological limitations; and serious concerns about relevance |

| CFIR Domain III: Factors affecting implementation related to inner setting | |||

| Finding 7: Hospital staff greatly valued the nature and quality of social networks between the bedside and CCT hub teams. Key issues for them were trust, acceptance, teamness, familiarity and effective communication between the two teams | Hoonakker 2018; Jahrsdoerfer 2013; Kahn 2019; Khunlertkit 2013; Moeckli 2013; Mullen‐Fortino 2012; Stafford 2008a; Wilkes 2016 | High confidence | Graded as high confidence because of no or very minor concerns about relevance, coherence, and adequacy; and minor concerns about methodological limitations |

| Finding 8: Hospital bedside staff were concerned over the hub team not being aware of local unit norms, values, and culture. This led local bedside teams to feel that CCT intruded on their practice | Kahn 2019; Moeckli 2013; Mullen‐Fortino 2012; Stafford 2008a; Ward 2015; Wilkes 2016 | Moderate confidence | Downgraded to moderate confidence because of moderate concerns about methodological limitations, relevance, and adequacy |

| Finding 9: Bedside clinicians were reluctant to use CCT because they lacked clarity about its purpose, were concerned that their decision‐making skills would be weakened through remote supervision, and did not consider hub clinicians an equal counterpart in patient management. Hub clinicians were disengaged due to lack of role clarity and limited integration with patient care | Kahn 2019; Moeckli 2013; Shahpori 2011a; Stafford 2008a | Moderate confidence | Downgraded to moderate confidence because of minor concerns about methodological limitations, and adequacy; and moderate concerns about relevance. |

| Finding 10: Hospital locale shaped prioritisation of CCT, with staff in rural centres noting that CCT was of greater benefit to them considering their staff shortage and lack of critical care resources | Kahn 2019; Shahpori 2011a; Ward 2015; Wilkes 2016 | Low confidence | Downgraded to low confidence because of moderate concerns about methodological limitations, relevance, and coherence; and serious concerns about adequacy |

| Finding 11: Bedside and hub clinicians perceived the absence of support from, and lack of engagement in dialogue with leaders and senior administrators during the implementation of CCT as major barriers. Listening to staff needs, and creating groundwork connections with them from the outset were perceived as facilitating factors to implementation | Kahn 2019; Wilkes 2016 | Low confidence | Downgraded to low confidence because of minor concerns about methodological limitations; moderate concerns about relevance; and serious concerns about adequacy |

| Finding 12: Hospital staff expressed it was important to promote and offer training in the use of CCT before its implementation. This included rehearsing every step in the process, offering staff opportunities to ask questions and disseminating learning resources. Some also complained that experienced staff were taken away from bedside care and re‐allocated to the CCT hub team | Kahn 2019; Moeckli 2013; Shahpori 2011a; Stafford 2008a; Ward 2015 | High confidence | Graded as high confidence because we had minor concerns about relevance, coherence, and adequacy; and moderate concerns about methodological limitations |

| Finding 13: Hospital staff reported the lack of access to information about how CCT staff, policies and procedures can be incorporated into the bedside workflow as a barrier to implementation | Moeckli 2013 | Low confidence | Downgraded to low confidence because of minor concerns about methodological limitations; and serious concerns about relevance, and adequacy |

| CFIR Domain IV: Factors affecting implementation related to characteristics of individuals | |||

| Finding 14: Hospital staff's attitudes towards, knowledge about and value placed on CCT influenced acceptance of CCT. Staff were positive towards CCT because of its several advantages. But, some were concerned that the CCT hub staff were not able to understand the patient’s situation through the camera. Some were also concerned about confidentiality of patient data | Kahn 2019; Khunlertkit 2013; Moeckli 2013; Mullen‐Fortino 2012; Shahpori 2011a; Stafford 2008a; Thomas 2017 | High confidence | Graded as high confidence because of minor concerns about methodological limitations, relevance, coherence, and adequacy |

| Finding 15: Hospital staff noted that acceptance and normalisation of CCT in their daily work took time; progressing through different stages of change did not occur at the same pace for everyone, with some remaining resistant to change | Kahn 2019; Khunlertkit 2013 | Low confidence | Downgraded to low confidence because of minor concerns about coherence; moderate concerns about relevance; and serious concerns about adequacy |

| Finding 16: Hub nurses’ personal attributes, specifically about their motivation, multitasking competence and values, were noted as important enablers for implementation of CCT | Hoonakker 2013 | Low confidence | Downgraded to low confidence because of minor concerns about methodological limitations; moderate concerns about adequacy; and serious concerns about relevance |

| CFIR Domain V: Factors affecting implementation related to process | |||

| Finding 17: Hospital staff were frustrated due to lacking a clear strategy for engagement; specifically lack of consistent training, the orientation of new and resistant staff to the hub facility, and timely co‐ordination for CCT implementation | Kahn 2019; Moeckli 2013 | Low confidence | Downgraded to low confidence because of minor concerns about methodological limitations, and coherence; moderate concerns about relevance; and serious concerns about adequacy |

| Finding 18: Hospital staff were encouraged by the visibility of the intended benefits of CCT. They valued both quantitative feedback through auditing, as well as qualitative feedback through reflective accounts | Kahn 2019; Khunlertkit 2013; Thomas 2017 | Moderate confidence | Downgraded to moderate confidence of minor concerns about coherence, and adequacy; and moderate concerns about relevance |

| Other factors affecting implementation | |||

| Finding 19: Hospital staff highlighted that CCT can support ICUs to overcome challenges associated with staff shortages especially during nights and weekends, and in rural hospitals where ICU nurses are assigned to different departments; and with retaining physicians and nurses. Some concerns over the potential negative impact of CCT on overall staffing levels were also expressed | Goedken 2017; Hoonakker 2013; Kahn 2019; Shahpori 2011a | Moderate confidence | Downgraded to moderate confidence because of minor concerns about relevance; moderate concerns about methodological limitations, and adequacy |

| Finding 20: Interactions between some bedside and CCT hub staff were featured with tension, frustration and conflict. Staff on both sides commonly described disrespect of expertise, resistance and animosity | Hoonakker 2013; Kahn 2019; Khunlertkit 2013; Moeckli 2013; Mullen‐Fortino 2012; Stafford 2008a; Wilkes 2016 | High confidence | Graded as high confidence because of no or very minor concerns about coherence and adequacy; minor concerns about relevance; and moderate concerns about methodological limitations |

Background

International interest in the benefits and implementation of telemedicine in a variety of settings and for different conditions is growing fast, as evidenced by the recently published Cochrane intervention review (Flodgren 2015) and Cochrane qualitative evidence synthesis protocol (Odendaal 2020). This is especially the case in the care of critically‐ill people. The burden of critical illness is higher than is generally appreciated, and is expected to increase as a result of global population ageing (Adhikari 2010; Vincent 2014). Consequently, critical care services in major hospitals are stretched, while smaller hospitals and rural areas have limited access to relevant expertise (Wunsch 2008). In addition, critical care is challenged by inconsistent application of evidence‐based guidelines, variation in staffing levels and clinical outcomes, higher rates of medication errors and adverse drug events (Pronovost 2004; Rothchild 2005), all of which are aggravated by the unpredictable nature of patient conditions, the urgent nature of many admissions to critical care and the need for out‐of‐hours decision‐making. For the purposes of this review, we define critical care as the concentration of healthcare staff and equipment in a distinct area of the hospital in order to care for people whose conditions are life‐threatening and who need constant and close monitoring and support.

Description of the topic

Telemedicine has been broadly defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as: “the delivery of health care services, where distance is a critical factor, by all health care professionals using information and communication technologies for the exchange of valid information for the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of disease and injuries, research and evaluation, and for the continuing education of health care providers, all in the interests of advancing the health of individuals and their communities” (WHO 2010). Critical care telemedicine (CCT) in particular enables a team of critical care doctors and nurses to provide 24‐hour remote support to clinicians using audio‐visual communication and computer systems. In 2014, it was estimated that 8% of total intensive care unit (ICU) beds in the USA were covered by CCT, with an average growth rate of 8% a year (Khan 2014). CCT offers minute‐by‐minute monitoring and recording of vital organ function, making use of electronic records and remote surveillance in order to facilitate early detection and response to physiological deterioration. In addition, the integration of decision‐support tools and early‐warning systems supports adherence to clinical guidelines, which can level out variations in quality of care. Further advantages of CCT for stakeholders may include additional support for junior staff, with patients and families feeling looked after. Consequently, CCT has potential to improve clinical outcomes beyond the confines of the ICU for people who may benefit from critical care expertise but are not based in specialist units; for example, they may be in an emergency department, generic ICU or medical/surgical ward. This is possible by extending the availability and reach of critical care expertise through a hub‐and‐spoke model, adding a safety net to ward‐based and non‐specialist bedside providers.

The hub‐and‐spoke model of CCT is used in the context of multi‐location delivery of critical care services. A remotely‐based team of senior and experienced critical care clinicians ‐ called the hub ‐ is networked through audio‐visual communication and telemonitoring systems with a number of bedside terminals, clinicians and patients. The hub acts as a single point of contact for critical care advice and support, while through seamless extensions ‐ called spokes ‐ hands‐on patient care is provided across multiple locations. In a wider role, the hub can also take on co‐ordinating responsibilities, including patient flow through ICUs, brokering admission and discharge of patients, as well as quality, risk and performance management through early‐warning capabilities, rounding tools to monitor at‐risk patients, inbuilt clinical decision support and prompts for adherence to best practice. In summary, CCT includes the following functionality: synchronous, interactive client‐to‐provider telemedicine; telemonitoring; client health records; provider‐to‐provider telemedicine; provider‐based decision support; laboratory and diagnostics management; data collection, management and use.

CCT is designed as a continuous form of clinical support to bedside practice, enabling clinical oversight and interactions between providers. In this way, it is distinct from other telemedicine models that mainly offer an interface for sporadic consultation between providers and patients in remote locations, or between generalist and specialist clinicians. Critical care patients’ condition can be unstable, can deteriorate unexpectedly and quite rapidly, requiring close monitoring and prompt reaction by a multidisciplinary team of expert clinicians, there and then. As a consequence, critical care services tend to have increased organisational autonomy, resources and staffing levels compared to other areas of the hospital. These unique features of critical care practice can influence professionals’ perceptions, experience and use of CCT, all of which can affect successful implementation.

How the intervention might work

The implementation of new technologies in healthcare settings is beset with multiple challenges. Reports on the failure of widely‐accepted and seemingly diffused health technologies to become embedded in daily practise are commonplace in the literature, even where these have support by both clinicians and politicians (May 2000). To understand where the implementation of such technologies fail, a strong theoretical foundation is needed to guide the evaluation of such programmes. Use of implementation theory can help generate explanatory models and hypotheses about factors influencing implementation of health technologies, leading to the identification of approaches more likely to result in successful implementation.

For the purpose of this review, we will use the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) (Damschroder 2009) to theoretically conceptualise data from the included studies and to guide the data analysis. CFIR is a 'meta‐theoretical' model, made up of constructs generated out of a synthesis of existing theories; one of its strengths and unique features is that it does not depict rigid interrelationships, specific ecological levels, or specific hypotheses. This allows for theory development guided by exploratory questions such as what works, where and why across different contexts. The CFIR has been used successfully in reviews of eHealth and is found to offer great theoretical and explanatory capabilities (Ross 2016).

CFIR is composed of five key constructs, each made up of different factors that affect the implementation of innovations into practice (see Appendix 1). In summary, the five key constructs of the CFIR are:

Intervention characteristics;

Inner settings;

Outer settings;

Characteristics of individuals; and

Process of implementation.

The first construct, Intervention characteristics , refers to features of the intervention including its source, evidence base, advantage over other interventions, the extent of its adaptability, 'trialability' and complexity, as well as its quality and cost. The second and third constructs, Inner and Outer Settings , relate to the internal and external environment in which implementation occurs. For example, the inner setting is about features of the structural, political and cultural organisation contexts through which the implementation process takes place; while the outer setting relates to the economic, political and social context within which the organisation resides. The fourth construct refers to the Characteristics of the Individuals who engage with the intervention or the implementation process. Individuals’ knowledge and beliefs about the intervention, their self‐efficacy, personal attributes and identification with the organisation play a key part in the success or failure of the implementation process. The final construct relates to the Implementation process itself, which includes elements of planning, engaging with leaders, champions and change agents, carrying out the implementation plan and evaluating the process and experience.

Operationalising the CFIR as an organising framework in the context of this qualitative evidence synthesis allows for a theoretically informed approach to data extraction, analysis and synthesis; helps with the interpretation of results; and strengthens the theoretical transferability and comparability of conclusions. At the same time, it allows for testing of the CFIR and consequent elaboration in the context of telemedicine in general, and CCT in particular.

Why it is important to do this review

Cochrane Reviews (Flodgren 2015) on the use of telemedicine indicate that answering questions about its efficacy requires attention to the contextual features of its application, including participants and settings. Effectiveness reviews of CCT in particular report a great degree of variability in effectiveness (e.g. Young 2011a), likely related to challenges with successful implementation (Thomas 2009). For example, Wilcox 2012 concluded that "the impact of telemedicine likely depends on characteristics of the environment in which it is deployed, including ICU organisation"; however, existing quantitative studies report limited contextual details. Currently, adoption of CCT appears haphazard and unplanned, and decision‐making about this lies hidden; this risks patient safety, quality of care and resource waste. Before such complex interventions are to be further developed and implemented, a more complete understanding of the factors that influence successful implementation is necessary (Glenton 2013). These include the perceptions, experiences and values of relevant stakeholders, as well as usability and applicability in different contexts.

It is therefore important to complement existing effectiveness reviews on CCT with a qualitative evidence synthesis that enables understanding of the factors affecting successful implementation, and illuminates the unintended consequences, acceptability and feasibility of CCT. This is especially important given that, despite a lack of conclusive evidence, there has been a rapid uptake of CCT in North America; and considering that the 24/7 hub‐and‐spoke model of CCT may have reach beyond critical care – Critical Care Outreach and Emergency Departments, for example – and in this way has great potential to transform the provision, quality and safety of acute care across hospital settings in the future.

How this review might inform or supplement what is already known in this area

This qualitative evidence synthesis addresses a subset of the Flodgren 2015 effectiveness review on interactive telemedicine. By looking at CCT in particular; it will complement Flodgren 2015 by providing an added layer of knowledge that can enable a more nuanced understanding of the factors influencing implementation of CCT. It also complements the Cochrane qualitative evidence synthesis of experiences of mHealth technologies in primary health care (Odendaal 2020), since critical care represents the acute far end of the health system and the opposite pole to primary care. In addition, CCT is distinct as an application from the traditional models of mHealth, which rely on mobile technology, used in primary care, since it uses a hub‐and‐spoke model to provide a 24/7 continuous form of clinical support to bedside practice rather than just being an interface for sporadic communication between patients and providers.

Objectives

To identify, appraise and synthesise qualitative research evidence on healthcare stakeholders’ perceptions and experiences of factors affecting the implementation of CCT, and to identify factors that are more likely to ensure successful implementation of CCT for subsequent consideration and assessment in telemedicine effectiveness reviews.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Type of studies

We included empirical studies that used qualitative designs and methods for data collection and analysis. These included ethnographic studies using participant observation and phenomenological studies using interviews. We considered studies using mixed designs where the qualitative component and findings could be discerned; we also considered qualitative process evaluations as well as formative studies used to inform the design of CCT where the previous statement applied. We included studies regardless of whether these were linked to effectiveness studies of CCT. We excluded studies that used qualitative data‐collection methods but performed quantitative data analysis (e.g. using descriptive statistics). We considered both published and unpublished studies and studies published in any language. We did not exclude studies based on our assessment of methodological limitations, but used this information to assess our confidence in the review findings.

Topic of interest

Study participants

We considered all relevant stakeholders with a part to play in the implementation of CCT, including:

All kinds of critical care workers (i.e. professionals, paraprofessionals and lay health workers) who make use of telemedicine to support or provide care to patients or family members, or both. Critical care workers are the main users of CCT and/or are the ones whose daily work is influenced to various degrees by the introduction of CCT. Their views about acceptance, resistance to or rejection of CCT are likely to be a contributing factor to implementation success or failure.

Any other individuals or groups involved in the commissioning, evaluation, design and implementation of CCT. These individuals or groups can include administrative staff, information technology staff, managerial and supervisory staff, and industry partners who may or may not be based in a critical care facility, but must be involved in the use or implementation of CCT. We also considered participants identified as the technical staff who develop and maintain the CCT architecture used, since it is their logic and understanding of critical care services that underpin the final product at the point of use.

Critical care patients and family members who have been the consumers or been involved in the development of CCT. As the recipients of care mediated by CCT, their views are likely to hold insight into factors influencing successful implementation.

Study settings

We included studies of telemedicine programmes implemented in critical care services, irrespective of specialisation (e.g. general, cardiothoracic, liver), or country. For the purposes of this review, we define critical care as the concentration of healthcare staff and equipment in a distinct area of the hospital in order to care for people whose conditions are life‐threatening and who need constant and close monitoring and support. Critical care services provide intensive 24‐hour monitoring and support of threatened or failing vital functions in people who have illnesses with the potential to endanger life.

CCT interventions

This review focuses on healthcare stakeholders' perceptions and experiences of factors affecting the implementation of CCT; we considered studies that looked at either the initiation or ongoing delivery of CCT. For the purposes of this review, CCT consists of the following combination:

laboratory and diagnostics management, and patient health records including the continuous electronic recording of patients' vital signs at the bedside linked to a computer system enabling display of real‐time data;

provider‐based decision support, in the form of clinical decision‐making algorithms and electronic alerts; and

synchronous, interactive provider/client to provider telemedicine, using a remotely‐located team of critical care specialists, including doctors and nurses, who monitor the patients.

We required the presence of all three features to identify an intervention as CCT. We did not consider CCT applications that excluded clinical decision‐making as in some forms of plain remote screening.

Search methods for the identification of studies

Electronic searches

The EPOC Information specialist helped develop the MEDLINE search strategy in consultation with the review authors. We used the following databases to identify primary research studies for inclusion.

MEDLINE 1946 to October Week 3 2019, Ovid (searched 14 October 2019)

Embase 1974 to October Week 3 2019, Ovid (searched 14 October 2019)

CINAHL 1937 to October Week 3 2019, EbscoHost (searched 14 October 2019)

Web of Science Core Collection 1900 to October Week 3 2019, Clarivate Analytics (searched 14 October 2019)

The search strategies are given in Appendix 2; we tailored the MEDLINE search as necessary for each database following the Cochrane Qualitative Research Methods Group's guidelines (Booth 2011). We did not apply any limits on language or publication date. We searched all databases from inception to the date of search (14 October 2019). We included a methodological filter for qualitative studies.

Searching other resources

We sought related reviews through PDQ‐Evidence (www.pdq-evidence.org, searched 14 October 2019), the reference lists of which we scanned for relevant studies. We also searched the reference lists of all included studies.

Grey literature

We searched for grey literature through The Grey Literature Report (www.greylit.org, searched 14 October 2019) and OpenGrey (www.opengrey.eu, searched 14 October 2019). We used GoogleScholar to search for references to the included studies.

Selection of studies

We collated all titles and abstracts identified through the search strategy into one reference management database (Covidence). After removing duplicate records, four review authors (AX, KI, SB, MT) independently screened the corpus of identified literature for relevant studies using a predetermined tool based on the SPIDER framework (Cooke 2012; Appendix 3) to evaluate eligibility. Following title and abstract review, we excluded irrelevant citations. We retrieved the full text of all the papers identified as potentially relevant by two review authors. Two review authors then assessed these papers independently, resolving disagreements through discussion, or by involving a third member of the team.

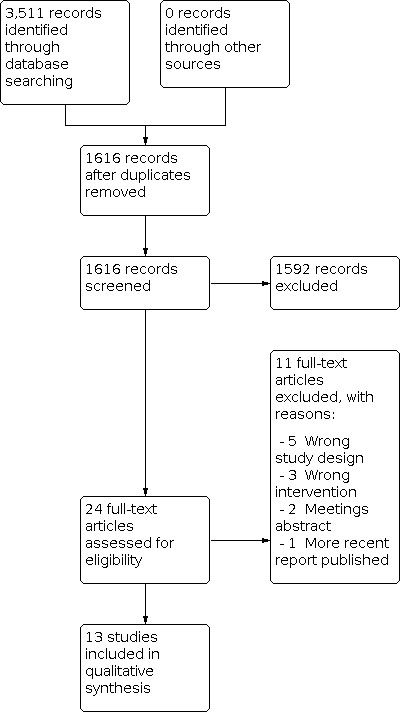

We include a table listing studies that we excluded from our review at the full‐text stage, and the main reasons for exclusion. We include a PRISMA flow diagram to show our search results and the process of screening and selecting studies for inclusion.

Language translation

Relevant studies published in a language other than English would have been translated following the approach proposed by Downe 2019. However, this was not necessary, since we did not find studies in languages other than English.

Sampling of studies

We acknowledge that qualitative evidence synthesis aims for variation in concepts rather than an exhaustive sample, and large amounts of study data can impair the quality of the analysis. Therefore, once we identified all the studies eligible for inclusion, we assessed whether their number or data richness were likely to represent a problem for the analysis, and considered selecting a sample of studies. For the purposes of this review, and given the limited literature on the topic of CCT, we decided against sampling and instead included all the eligible articles.

Data extraction

At least two review authors extracted key features of the included papers independently, using a predetermined table to include: author(s), year, country, hospital type, ICU model and staffing, CCT system and vendor, study design, data collection and participants. We also extracted data on stakeholders' perceptions and experiences of factors affecting the implementation of CCT; this included authors' interpretations as well as actual data in the form of quotes or field‐note extracts. We considered data presented in either the Results or Discussion sections of the articles.

Appraisal of the methodological limitations of included studies

Two review authors (AX, KI) independently applied a predetermined set of quality criteria to each of the included studies, based on the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) quality assessment tool for qualitative studies (CASP 2013). We considered all eligible studies, irrespective of quality. In cases of disagreement between the two review authors, a third member of the team (JP) was invited to adjudicate. We assessed methodological limitations according to the following questions:

Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research?

Is a qualitative methodology appropriate?

Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research?

Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research?

Were the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue?

Has the relationship between the researcher and participants been adequately considered?

Have ethical issues been taken into consideration?

Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous?

Is there a clear statement of findings?

We report our assessment in a Methodological Limitations table (Table 2, Additional Tables).

1. Methodological limitations of included studies.

| Study | Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research? | Is a qualitative methodology appropriate? | Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research? | Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research? | Were the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? | Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered? | Have ethical issues been taken into consideration? | Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? | Is there a clear statement of findings? |

| Goedken 2017 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Insufficient | Insufficient | No | Yes | Insufficient | Yes |

| The aim of the study is clearly expressed in the abstract and introduction of the paper | The study sought to illuminate ways in which Tele‐ICU can optimise its benefits, therefore a qualitative approach was the appropriate methodology to address the study's aim | Although the qualitative approach was appropriate to address study's aim, the researchers did not discuss or justify why they decided to employ the methods they used | The researchers did not discuss how participants were selected. However, all types of end‐users were included in the sample. There was also no reporting around the recruitment strategy. In their supplement they reported that they approached participants through an email and no participant declined to participate | Data saturation was not reported. The number of participants who were interviewed at the 3 time periods of data collection was not clearly presented. Field notes were not included in the analysis. Focus groups were only reported in the data collection section of the paper | The researchers' critical examination of their own role, potential bias and influence during data collection, sample recruitment and choice of location was lacking | The study was approved by the relevant institutions locally and nationally. Participants consented to participate in the study. However, no information was provided on whether participants had sufficient explanation about the study and whether confidentiality and anonymity would be maintained during and after data collection | An in‐depth description of the analysis process was lacking. Reporting of how the themes were derived from the data was not included, although the authors did report that they applied a coding tree. The researchers’ role, potential bias or influence during analysis and selection of data were not reported | Findings were clearly described, and adequate discussion about these was included. Findings were discussed in relation to the research aims. The 3 authors analysed only 10% of transcripts collectively; the remainder were analysed independently | |

| Hoonakker 2013 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Insufficient | Yes | Yes |

| The aim of the study was clearly stated. Researchers argued that it was important to examine the satisfaction and motivation of highly skilled and expert ICU nurses for working in the Tele‐ICU working environment, compared to a clinical ICU environment | A qualitative approach was reasonable, considering the research aims. No explanation was provided about the chosen qualitative approach and type of interviews | No overall qualitative design identified. The authors did not provide any justification about how they decided to use a qualitative approach and interviews | The researchers did not report any inclusion and exclusion criteria for sampling the Tele‐ICU nurses. Nor did they explain how the 10 Tele‐ICU nurses interviewed from each unit differed from those who were not interviewed | The data collection method was clearly described, although the choice of method was not justified. The setting where interviews were conducted was not reported. Although an interview guide was used, the link given to this was inactive. Saturation of data was not discussed, but the number of responses corresponding to each category is reasonable | The role of the researchers (bias or influence) during data collection, choice of location, and sample recruitment were lacking | The study was granted approval by the institutional research committees. Transcripts were kept anonymous. But no information was provided about participants' explanations about the purpose, benefits, and harms from the study. It was not clear if interviewees were asked to return a signed consent form | The data analysis process was described sufficiently. The researchers explained how data were selected from the original sample. Enough data extracts were used to support the study's findings. But the researchers did not discuss their own role and potential bias during analysis and selection of data for presentation | The findings were presented clearly. The research team read the transcripts and the interviews were coded by 2 researchers, thus enhancing rigour in the analysis. The findings were discussed in relation to the study's original aim | |

| Hoonakker 2018 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Insufficient | Yes | Yes |

| A clear statement of the aim of the research was reported. The researchers explained why the study was important to undertake | A qualitative approach was an appropriate methodology to address the study's aims, considering that the researchers aimed to explore Tele‐ICU nurses' experiences | The researchers used a case‐study research design by employing multiple data collection methods. This paper focused on the findings from the interviews. The researchers explained why they chose to use this research design | The study's participants accepted to be interviewed voluntarily. However, information about participants’, non‐participants’ characteristics, and whether any differences affected the quality of data was lacking. No discussion was provided about the process of recruitment | Interviews and other data collection methods were employed in the study. However, only interview data were reported in this paper. Interviews were recorded and analysed using a qualitative data analysis software. Saturation of data was not discussed. The structure of the participating setting was described | The researchers did not provide information about their background or relationship with the organisation and study participants | Transcribed interviews were anonymous, and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board. It was not reported if the study was explained to participants or they provided written consent | A clear description of the data analysis process was reported. Data were initially coded, before assembled into categories, and developed into matrices. The research team collectively completed the analysis over several meetings. The role of researchers during the data analysis process was not discussed | The findings were discussed in relation to the aim of the research. More than 1 researcher analysed the transcripts, and more than 1 method was used to collect data. Data extracts were not adequately used to support the researchers’ interpretations | |

| Jahrsdoerfer 2013 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| The aims of the research were clearly stated informing the reader about the study's participants and research design | The study used a questionnaire, which included 2 open‐ended questions. But the phrasing of those 2 questions along with low responses to them, and unclear data analysis, render the qualitative aspect of the study's research design weak | The researchers did not explain why they decided to employ a survey over other approaches (e.g. interviews) | There was a clear explanation of how the participants were selected, and why those selected were the most appropriate. The researchers provided possible explanations as to why the response rate in 1 site was low | Data were not collected in an optimal way to address the qualitative aspect of the study (understanding family members' perceptions) | Trained volunteers explained the study, distributed and collected the completed questionnaires from participants. In 1 site the volunteers did not fully adhere to the study protocol for recruitment | Anonymity of participants' responses was assured, and informed consent was provided. Completed questionnaires were placed in sealed envelopes. The study was approved by the institutional review boards at each of the participating hospitals | Identified themes were broken down into categories, but it was not clear how the themes were derived, and limited evidence was provided to support development of these themes. Moreover, the researchers did not critically discuss their role, potential bias or influence during data analysis | Only findings from 1 of the 2 open‐ended questions were reported. 2 researchers identified recurring themes from comments. Inadequate data extracts were used to support interpretations | |

| Kahn 2019 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| The goal of the study was clearly stated. Researchers presented clearly why the study was important and what its relevance was at general and individual level | The qualitative approach was appropriate to meet the study’s objective | The researchers employed a focused ethnography to address the study's aims. They explicitly justified why they chose to use in‐depth site visits and in‐person interviews | The researchers clearly described the process of ICU site selection in detail, based on set characteristics and eligibility criteria | The researchers justified their data collection choices. Interview and focus group guides were used, which were digitally audio‐recorded. Saturation of data was discussed. Details of the site visits were not provided. It is not clear when and for how long observations were held in each unit | The paper includes an online supplement which reports on the study methods. The researchers’ relationship with participants was reported in a previously published protocol | Written consent was provided by the participants and the study has been approved by a University Review Board. The study protocol discussed ethical considerations in detail | A rigorous data analysis process was described in full details in the study. A constant comparative approach was used. Interpretation of data were cross‐checked with participants. A thematic codebook was developed. The researchers' role during data analysis has been discussed | The findings were clearly described and discussed in relation to the research aims | |

| Khunlertkit 2013 | Yes | Yes | Insufficient | Yes | Yes | Insufficient | Insufficient | Yes | Yes |

| The aim of the research was clearly stated. The researchers explained why the study was important, and its relevance within Tele‐ICU research field | The qualitative approach was appropriate to shed light to existing knowledge about Tele‐ICU care processes and patient outcomes | No overall design identified. They did not provide any justification for the study's methodology | The researchers explained why they used a purposeful sampling strategy. Moreover, they justified why the study's sample was the most appropriate to provide the type of knowledge relevant to the study's aim. Inclusion criteria were presented | Information about the location of interviews was provided. It was reported how data were collected, and what predefined questions and probes were asked during the interviews. The link to the interview guide is no longer active. Saturation of data was discussed | The issue of selection bias, and the actions employed to mitigate its impact on the study's results, were examined. The issue of interviewer's bias was addressed | Ethical issues were taken into consideration. The study was approved by 3 institutional review boards. All participants consented to be interviewed. IRBs waived the need for informed consent; it is unclear if participants gave written consent | A detailed description of the data analysis process was included. 2 analysts were involved in data analysis and theme identification. Sufficient data were presented to support the study's findings. Both positive and negative outcomes were taken into consideration in the presentation of findings | The findings were explicitly described. Extracts from the interviews provided rich insights into the identified themes. A sufficient discussion of the findings about the original research aim was included | |

| Moeckli 2013 | Yes | Insufficient | Insufficient | No | Insufficient | No | Yes | Insufficient | Yes |

| The aim of the study was clearly stated. The researchers justified why the study was important, and reported what gaps in research they attempted to address | Given the focus of the study to evaluate the impact of a Tele‐ICU programme, the choice of qualitative methodology, without a quantitative component in the study, was not sufficiently justified | The researchers employed interviews and observation to address the study's aims. Although a qualitative approach was appropriate, the researchers did not discuss or justify their choice of methods | Participant selection was not explained. No information was provided on why some participants were interviewed in the pre‐ and others in the post‐implementation phase | Data collection methods were not adequately justified. Not enough information was provided about the observational data. The rationale for using observation was not explained, and it was not clear how observational data corroborated interview data. Saturation of data was not discussed | There was no critical examination of the researchers’ role during data collection, sample recruitment and choice of research site. The role of observers – for example, participant or non‐participant observation, establishment of rapport, maintenance of role‐boundaries and Hawthorn effect – was not discussed | Approval was granted by the national and local institutional review boards. Informed consent was obtained by participants, but little is reported about how the study was provided to participants, whether participants’ identification was concealed | Limited information was provided about the codebook development. Thematic analysis was performed, but reporting of the process through which the themes were identified was lacking. Sufficient data were presented to support the findings, while contradictory data were also considered | Development of the findings was not adequately explained. The trustworthiness of the findings was enhanced with a consensus coding by 3 researchers, but this process was only applied to 10% of the data | |

| Mullen‐Fortino 2012 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| A clear statement of the study's aim and relevance was reported | An internet survey was used to address the study's aims. Participants were also given space to report their opinions about the Tele‐ICU programme. The nature of the survey does not allow for in‐depth understanding of attitudes toward, and perceptions about, the use of telemedicine | The cross‐sectional research design was not ideal to examine in depth the nurses' perceptions about the Tele‐medicine programme | The researchers explained how the participants were selected, and why they were appropriate to provide the type of data sought by the study | The open‐ended space allowed on the questionnaire for gaining nurses' perceptions of tele‐medicine did not allow for collection of in‐depth and rich data | The researchers did not critically examine their own role, potential bias or influence during data collection, sample recruitment and choice of location | The survey was administered anonymously to the participants. No information was provided whether the study was adequately explained to participants | Analysis of answers to the open‐ended questions was performed by reviewing the participants' responses and summarising key themes. Participant quotes were reported in a table to support the identified key themes | The identified themes and corresponding quotes were presented in a table. The qualitative findings were inadequately discussed. There was no mention of credibility, respondent validation or use of more than 1 analyst | |

| Shaphori 2011 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | Insufficient | No | Insufficient |

| There was clear reporting of the study aims. The researchers discussed why they considered the study significant in the wider context of Tele‐ICU research | The study used a survey questionnaire to address the study's aims. For each survey question, a free‐text section was provided to capture participants' concerns and suggestions before implementation of a Tele‐ICU intervention | The researchers aimed to capture staff concerns and suggestions about the implementation of ICU‐Telemedicine. For this purpose, free‐text sections were added within each survey question which captured data in a limited way | The researchers explained how and why the participants were selected. No characteristics were provided about the non‐respondents to the survey | The researchers justified the choice of setting for the data collection. Data were collected through survey questionnaires. Free‐text sections for each survey question formed the basis of the qualitative data in the study. Saturation of qualitative data was not discussed | The relationship between the researchers and participants was not reported in the study | The study was approved by ethics and research review boards. An educational preparation for the study was provided prior to the survey. The survey was administered anonymously, but issues around maintaining confidentiality of qualitative data were not reported in the study | An in‐depth description of the analysis process was lacking, and no explanation provided about how the data presented were selected from the original sample to demonstrate the analysis process | Summary commentary data were presented in the study, although actual quotes were missing. The credibility of the qualitative findings was not discussed. An adequate discussion of the findings about the study's aims was provided | |

| Stafford 2008 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| The goal of the study was to describe the experiences of healthcare workers in the eICU and to examine how they functioned in this setting. The researchers justified the significance of this study | An ethnographic approach was used in this study. This approach was appropriate for addressing the study's aims, that is, to describe staff experiences and interactions | The researchers used ethnography, with semi‐structured interviews and participant observation. The researchers explained their choice of design and data collection methods | A purposeful sample was targeted, including all eICU physicians and eICU nurses. The researchers reported how many participated in the semi‐structured interviews and how many participated in the field study. Nobody declined to participate in the study | The setting was clearly described. The researchers clearly explained and justified their choice of data collection methods. But no information was provided about the interview topic guide and observation schedule. Saturation of data was not discussed | The researchers’ role during the formulation of the research aims, data collection methods, sample recruitment and choice of the research setting was not adequately discussed | The study was approved by the participating institutions' review boards. Participants provided informed consent, while identifiers or names in the transcriptions were avoided. But there was insufficient information about how the research was explained to participants | The analysis process was described sufficiently. Coding, memos and typologies were used as part of the analysis. An audit trail was used to assure confirmability. Credibility, transferability, and dependability were also considered | The findings were explicitly presented, and adequate discussion of these was provided. The number of data analysts was not reported. Credibility of the findings was established through data triangulation | |

| Thomas 2017 | Yes | Yes | Insufficient | Insufficient | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| The aim and significance of the study were clearly stated | A qualitative approach was appropriate to address the study's aims. The researchers aimed to understand how ICU physicians and nurses understood and practised Telemedicine | Individual and group semi‐structured interviews were conducted. The researchers supported their choice by justifying the strengths of open‐ended qualitative interviewing, but details and justification for the focus groups is missing. An overall qualitative design is not identified | It was noted that sample might not have been representative of the population. No information was provided whether more participants were needed to generate data. Little was known why some chose not to take part, and whether a clear recruitment strategy was used | An adequate explanation of how interviews were conducted was provided by the researchers. Saturation of data was not discussed. More details about the characteristics of the setting, interview guide and interview transcripts were previously described | The researchers did not discuss their own role, potential bias and influence during data collection. Little was noted about where the interviews took place and whether any interruptions occurred, and if so how these were managed | The study was approved by Institutional and research boards. Informed consent was obtained by all participants. However, little is known about whether clear explanations of the study was provided; what were the study's potential benefits and harms; and how anonymity of transcripts was ensured | Information about the coding process was missing. Information about the researchers' role during analysis was lacking. No information was provided about their education, background, and perspective. A thematic analysis was used by applying inductive and deductive coding | Findings were explicitly described in the study with an adequate discussion of these in relation to the original aim of the study. Independent analysis of the data by more than 1 researcher was performed. Verbatim quotes were presented | |

| Ward 2015 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Insufficient | No | Insufficient |

| A clear statement of the aim of the research was reported in the study, which was to assess staff acceptance at multiple hospitals that had implemented a Tele‐ICU system. The researchers also reported why they thought their study was important | The study used both quantitative and qualitative methodology to address the aims of the study. Qualitative approach was appropriate, given the aim to gain a deeper understanding of factors affecting staff perceptions of Tele‐ICU services | Although the researchers provided a discussion about using a qualitative approach alongside a survey, they did not fully explain or justify this design choice | It was not explained how participants were selected from the total sample; whether they had also completed the survey or not; and why they were the most appropriate to provide the data sought by the study. Participant characteristics were not reported | Data were collected through phone interviews and site visits. No information was provided on how interviews were conducted or if a topic guide was used. Interviews were recorded and transcribed. Saturation of data was not discussed. Interview process and purpose of site visits was unclear |

The study provided no critical account of the researchers' role, potential bias and influence during data collection and choice of research location | The review boards approved the protocols for the interviews. Transcripts from the interviews were anonymised. It was not clear whether a detailed explanation of the study's aims, potential benefits or harms, and issues of confidentiality were provided to participants | No information was reported about the coding process; how themes were derived from the data; the role of the researchers; and potential bias or influence. Data were reported as narrative text of the authors’ interpretations instead of direct participant quotes | There was a clear description of the identified themes. A summary of the interviewees' responses supported each theme. An adequate discussion on the qualitative findings related to the study's aims was presented. 3 researchers coded and analysed the qualitative data into themes. No direct quotes provided | |

| Wilkes 2016 | Insufficient | Yes | Insufficient | Yes | Insufficient | No | Insufficient | Insufficient | No |

| The aim of the research was phrased in slightly different ways throughout the text. The significance of the study was discussed | The qualitative methodology used in the study was appropriate, considering that the aim to gain insight into the organisational culture of Tele‐ICUs. | The study used semi‐structured interviews, which were appropriate to address the aims of the research. The overall study design was unclear | There was adequate explanation of the research settings and participants. Justifications were provided about why some participants were not interviewed. Purposive sampling was used, but interviews were recommended by 'administrative leaders' without a clear indication of selection criteria | The researchers justified their choice of method. Interview guides were developed. Saturation of data was not discussed. Handwritten notes were taken during the interviews, increasing the risk of inaccuracies. The researchers discussed their efforts to assure accuracy of notes, but whether this was achieved remains questionable | The study did not report the researchers' role, potential bias and influence during data collection, recruitment or choice of research sites | The study was sufficiently explained to the participants. An informed consent form was signed by the participants, and their anonymity was ensured. Approval was sought by the research company review board. Approval from a university review board, or from the hospital sites is not mentioned | Inter‐analyst agreement was mentioned, but a clear indicator for this was not reported. Much of the findings were from the researchers’ interpretation, not always supported by participant quotes. The researchers' role, potential bias and influence were not reported | The study's findings were not reported in a clear and explicit way, resulting in difficulty in tracking the identified themes. Some discussion about the existing literature was included. Credibility of the study was enhanced by including more than 1 analyst |

Data management, analysis and synthesis

We imported all the included papers into the NVivo qualitative data analysis software (QSR International). Data synthesis drew from the CFIR framework (Appendix 1) to examine the available evidence on factors affecting the implementation of CCT. As noted in the Background, the CFIR is a 'meta‐theoretical' model, made up of five constructs: I. Intervention characteristics, II. Inner and III. Outer Settings, IV. Characteristics of individuals, and V. the Process of implementation. CFIR informed but did not restrict data synthesis, with additional themes not captured by CFIR used to challenge and add to previously‐held assumptions. This approach led to a more refined understanding of implementation in the context of CCT, building on and extending the propositions of CFIR, thus strengthening the theoretical generalisability of the review findings.

We followed the Best‐fit framework approach (Carroll 2013), since this allows examination of the alignment of identified themes with an existing framework, as well as conceptual revisions as necessary. Our approach consisted of four main analysis stages completed by two review authors (AX, KI): First, we developed a coding tree in NVivo based on the CFIR framework and coded data from the included studies against this. Second, themes not accounted for by CFIR were noted, coded and classified under separate constructs. Third, following a consensus approach, we used additional constructs to supplement CFIR; had the framework changed substantially, the papers would be re‐coded based on the new framework, but this was not required. Fourth, we revisited the data to explore relationships between themes and constructs in order to develop concise review findings statements that capture the coded data.

Assessing our confidence in the review findings

Two review authors (AX, KI) used the GRADE‐CERQual (Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research) approach to assess our confidence in each finding (Lewin 2018). CERQual assesses confidence in the evidence, based on the following four key components.

Methodological limitations of included studies: the extent to which there are concerns about the design or conduct of the primary studies that contributed evidence to an individual review finding

Coherence of the review finding: an assessment of how clear and cogent the fit is between the data from the primary studies and a review finding that synthesises those data. By cogent, we mean well‐supported or compelling

Adequacy of the data contributing to a review finding: an overall determination of the degree of richness and quantity of data supporting a review finding

Relevance of the included studies to the review question: the extent to which the body of evidence from the primary studies supporting a review finding is applicable to the context (perspective or population, phenomenon of interest, setting) specified in the review question

After assessing each of the four components, we made a judgement about the overall confidence in the evidence supporting the review finding. We judge confidence as high, moderate, low, or very low. The final assessment was based on consensus among the review authors. All findings started as high confidence and were then downgraded if there were important concerns about any of the CERQual components. The starting point of high confidence reflected a view that each review finding should be seen as a reasonable representation of the phenomenon of interest, unless there were factors that weakened this assumption.

Summary of qualitative findings table and Evidence Profiles

We present summaries of the findings and our assessments of confidence in these findings in Table 1. We present detailed descriptions of our confidence assessment in a two‐part Evidence Profile (Table 3; Table 4, Additional Tables).

2. Evidence profile (findings 1‐10).

| Finding 1: Hospital staff’s personal experience, and anecdotes from colleagues, supported their belief that CCT has positive effects on patient care. Specifically, these effects were in terms of patient safety and quality of care, support at the bedside by critical care experts, and standardisation of practice. | |

| Assessment for each GRADE‐CERQual component | |

| Methodological limitations | 6 studies contributed data to this finding. None of the studies discussed researcher reflexivity. 2 studies were assessed as having methodological limitations related to data analysis and collection, of which 1 study was assessed as having methodological limitations related to research design and the other was assessed as having methodological limitations related to recruitment. A third study was also assessed as having methodological limitations related to recruitment. The body of evidence contributing to this review finding was assessed as having minor concerns about methodological limitations |

| Coherence | No or very minor concerns about coherence |

| Relevance | Moderate concerns about relevance, because while the studies covered different ICU settings from different countries these were all North American; and the value staff placed on their experiences and anecdotes is likely to differ across world regions |

| Adequacy | Minor concerns about adequacy, because the 6 studies together offer only moderately rich data |

| Overall GRADE‐CERQual assessment and explanation | |

| Moderate confidence | Downgraded to moderate confidence because we had minor concerns about methodological limitations, coherence, and adequacy; and moderate concerns about relevance |

| Contributing studies | |

| Khunlertkit 2013; Moeckli 2013; Shahpori 2011a; Stafford 2008a; Ward 2015; Wilkes 2016 | |

| Finding 2: Hospital staff and family members described several advantages of CCT. Bedside and hub staff strongly believed that the main advantage of CCT was having access to experts when bedside doctors were not available. Families also valued having access to experts. In addition, hospital staff described how CCT could support clinical decision making and mentoring of junior staff | |

| Assessment for each GRADE‐CERQual component | |

| Methodological limitations | 7 studies contributed data to this finding. 2 studies discussed researcher reflexivity. 2 studies were assessed as having methodological limitations related to data analysis, research design and data collection. 1 study was assessed as having methodological limitations related to recruitment. The body of evidence contributing to this review finding was assessed as having minor concerns about methodological limitations |

| Coherence | No or very minor concerns about coherence |

| Relevance | Minor concerns about relevance, because the studies covered different ICU settings from different countries, and even though these were all North American the focus of the finding is on standard features of CCT technology that are unlikely to differ across world regions |

| Adequacy | No or very minor concerns about adequacy |

| Overall GRADE‐CERQual assessment and explanation | |

| High confidence | Graded as high confidence because we had minor concerns about methodological limitations, relevance, coherence, and adequacy |

| Contributing studies | |

| Jahrsdoerfer 2013; Kahn 2019; Khunlertkit 2013; Moeckli 2013; Shahpori 2011a; Stafford 2008a; Thomas 2017 | |

| Finding 3: Bedside staff valued the potential adaptability of CCT to speak to local needs and practices. However, this was not always evident, with reported examples being mainly around developing camera usage etiquette and integration with local protocols. | |

| Assessment for each GRADE‐CERQual component | |

| Methodological limitations | 3 studies contributed data to this finding. 1 study discussed researcher reflexivity. 1 study was assessed as having methodological limitations related to recruitment. The body of evidence contributing to this review finding was assessed as having no or very minor concerns about methodological limitations |

| Coherence | Minor concerns about coherence, because the data contributing to the review finding were only reasonably consistent within studies |