Abstract

Mangroves are among the most carbon-dense ecosystems on the planet. The capacity of mangroves to store and accumulate carbon has been assessed and reported at regional, national and global scales. However, small-scale sampling is still revealing ‘hot spots’ of carbon accumulation. This study reports one of these hotspots, with one of the largest-recorded carbon stocks in mangroves associated with sinkholes (cenotes) in the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. We assessed soil organic carbon (SOC) stocks, sequestration rates and carbon origin of deep peat soils (1 to 6 m). We found massive amounts of SOC up to 2792 Mg C ha−1, the highest value reported in the literature so far. This SOC is primarily derived from highly preserved mangrove roots and has changed little since its deposition, which started over 3220 years ago (±30 BP). Most cenotes are owned by Mayan communities and are threatened by increased tourism and the resulting extraction and pollution of groundwater. These hot spots of carbon sequestration, albeit small in area, require adequate protection and could provide valuable financial opportunities through carbon-offsetting mechanisms and other payments for ecosystem services.

Keywords: Caribbean, carbon credits, karst, soil organic carbon, Yucatan, wetlands

1. Introduction

Mangroves are among the most carbon-dense ecosystems on the planet and offer significant potential to mitigate atmospheric carbon concentrations [1]. As a result, efforts to map their aerial cover, and associated carbon stocks, have been undertaken through spatial models [2] and intensive field campaigns [3]. However, even the most detailed and accurate global or national model cannot reasonably account for ‘hot spots’ of carbon storage and sequestration, especially when they are very small in area, albeit extremely dense in carbon. Carbon projects are emerging as an innovative conservation tool, where carbon accumulated in ecosystems can be sold through carbon-offset markets [4]. These projects typically need to be large to ensure that the project is financially viable, i.e. that the costs of conservation or restoration are lower than the value of the carbon. However, sites that are very dense in carbon may provide enough credits to meet the project targets. Here, we provide evidence for one of those hotspots in mangroves associated with sinkholes in the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico.

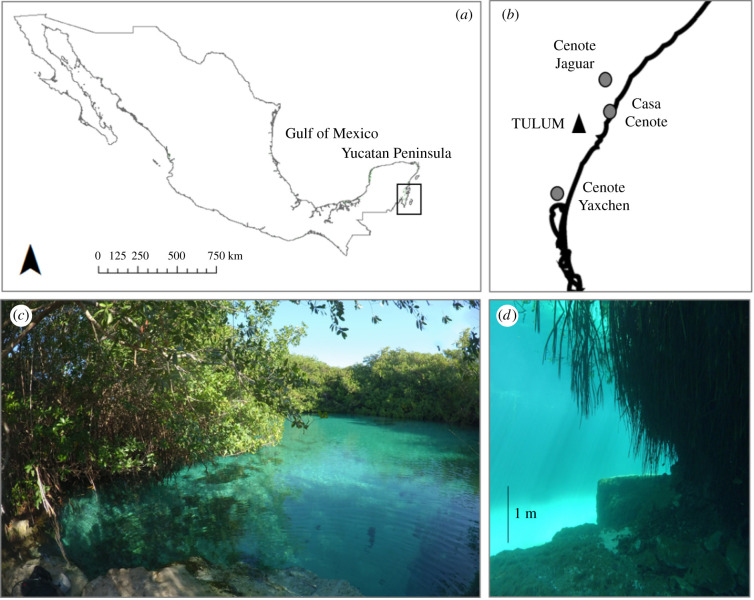

The Yucatan Peninsula is characterized by one of the largest karst aquifer networks in the world, with a surface area of 165 000 km2 of permeable limestone [4]. Rainwater slowly dissolves the calcium carbonate forming a groundwater network, with ongoing dissolution eventually leading to the collapse of the limestone [5]. This process can create sinkholes, locally known as cenotes, a word derived from the low-land Maya language ‘tz'onot’. There are over 2000 cenotes distributed throughout the Yucatan Peninsula. In the north, cenotes were formed by the impact of the Chicxulub asteroid creating a feature known as ‘Ring of Cenotes’ [6]. In the east, cenotes are associated with the Holbox fault, which formed open water bodies parallel to the coastline. In these cenotes, seawater intrudes into the aquifer creating a habitat for dense mangrove forests (figure 1). Cenotes are highly valuable wetlands that provide habitat for migrating birds and many endemic amphibians and freshwater fish, many of which are classified as endangered [6]. Despite their importance, cenotes face significant threats, including groundwater extraction that supports a rapidly growing tourist industry and pollution from agricultural and domestic activities [7].

Figure 1.

(a,b) Sampling sites within the east coast of the Yucatan Peninsula, near Tulum, Mexico; (c) the sinkholes are surrounded by dense mangrove forests, (d) the peat underneath the mangroves can be 6 m deep (Casa Cenote, pictures MF Adame).

Preliminary studies have shown that the mangroves associated with groundwater in the Yucatan Peninsula can have very large carbon stocks exceeding 1000 Mg C ha−1 [8]. However, these values may underestimate their carbon content due to the difficulty of taking deep soil cores (greater than 2 m). Here, we explored sinkholes surrounded by mangroves in the Yucatan Peninsula, where deep soil samples (up to 6 m) were accessible through underwater caves. The objectives were to obtain carbon stock estimates, identify the origin of this carbon and calculate sequestration rates within mangroves associated with these potential carbon hotspots.

2. Methodology

(a) . Study site

Yucatan Peninsula is in the southeast of Mexico. The region has a tropical wet–dry climate (Köppen classification Aw) with a mean annual temperature of 25.7°C (mean annual minimum and maximum of 20.0 and 31.4°C, respectively) and mean annual precipitation of 1122 mm (Tulum Meteorological Station, 1981–2010; [9]). There are three distinct seasons: a cool season of nortes (north winds) from November to January with sporadic rains (mean monthly precipitation of 68.3 mm), a hot dry season from March to April (37.7 mm) and a hot wet season from May to October (133.9 mm), when tropical storms are common.

We selected three cenotes associated with mangroves, where SCUBA diving was accessible (figure 1). Casa Cenote (20°16′ N, 87°23.5′ W) is a narrow meandrous cenote located 50 m from the sea with a cave opening of about 1000 m2. This cenote has a maximum depth of 8 m, with a halocline at 6.5 m separating brackish (12.5 ppt of salinity) at the surface from marine water at the bottom (35 ppt salinity). Cenote Yaxchen (20°07′52′ N, 87°28′ W) is about 350 m from the sea, with an opening of 6500 m2, maximum depth of 7.5 m and a similar halocline profile as Casa Cenote. Finally, Cenote Jaguar (20°19′ N, 87°23′ W) is located furthest from the sea, 2 km inland, with an opening of 500 m2, a maximum depth of 8 m and no halocline, with salinity values <3 ppt throughout the water column.

(b) . Methodology

Sampling was conducted in September 2019 with SCUBA equipment. We sampled two points at Cenote Jaguar and Yaxchen and four points at Casa Cenote. Within each point, underwater sampling was conducted with a 60 ml mini core, which resulted in minimum compaction. Sampling was done at each of the following depths: 0–15, 15–30, 30–50, 50–100 cm, and every 100 cm until the bottom of the peat [10], which varied among sites. The deep peats were accessed with the SCUBA equipment from the underwater cave system of these cenotes (see video in the electronic supplementary material or https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lGVYxnlkHu8&feature=youtu.be). In Cenote Jaguar, the peat layer was 1 m deep; in Yaxchen, the peat reached 5 m and in Casa Cenote, it reached 6 m. The samples were refrigerated and transported to the laboratory, where they were oven-dried and weighed. Bulk density was determined from the dry mass per wet volume (expressed as g cm−3).

Soil samples were acid-washed with HCl to eliminate carbonates and analysed for soil organic carbon (SOC) and δ13C with an elemental analyser coupled with an isotope ratio mass spectrometer [8] (EA-IRMS, Serco System, Griffith University, Brisbane, Australia; analytical standard deviation less than 0.1‰). The stability and origin of soil carbon were determined from the variation of δ13C values with depth. We expected that isotope values would remain constant with depth if carbon was stable through time and decomposition was low; on the contrary, isotopic values would increase if decomposition was high [11]. We also expected that if all the carbon were from mangrove roots, δ13C would be close to −28‰, a value typical of plants with a C3 photosynthetic pathway and common for mangroves in the region [12].

Three soils samples (from 75 cm deep in Cenote Jaguar and 450 cm deep in Casa Cenote and Yaxchen) were radiocarbon dated at Beta Analytics (Miami, USA). The results were corrected for isotopic fractionation and calibrated with the 2013 INTCAL program (Libby half-life, 5568 years) and rounded to the nearest 10 years [13,14]. Carbon sequestration rates were estimated by dividing the SOC stock above the sampled depth by the age of the sample. Comparison between SOC stocks and depth were conducted with a linear regression, where samples were pre-tested for normality and homogeneity of variances with the program SPSS Statistics v26 (IBM, USA).

3. Results

The SOC for all sites was 38.5 ± 0.9% (mean ± s.e.), values close to vegetation, indicating that the samples were mostly peat, with little sediment (table 1). Bulk density was low with values of 0.11 ± 0.01 g cm−3. The δ13C values were remarkably consistent with depth (difference < 2‰ for all sites and depths). Carbon stocks were very high at Casa Cenote and Cenote Yaxchen with a mean value of 1492 ± 549 and 1518 ± 561 Mg C ha−1, respectively, with one sampling point in Casa Cenote reaching 2792 Mg C ha−1. In comparison, SOC stocks at Cenote Jaguar were moderate with 429 ± 44 Mg C ha−1.

Table 1.

Bulk density (BD; g cm3), SOC (%), δ13C (‰), SOC stock, radiocarbon age (BP) and sequestration rates (Mg C ha−1 yr−1) of three mangrove cenotes in the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico; n = number of sampling sites. Values are (mean ± s.e.).

| depth | BD (g cm3) | SOC (%) | δ13C (‰) | SOC stock (Mg C ha−1) | radiocarbon age (±30 BP) | SOC sequestration (Mg C ha−1 yr−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cenote Jaguar (n = 2) | ||||||

| 0–15 | 0.10 ± 0.03 | 41.6 ± 0.1 | −28.3 | 61.7 ± 19.0 | ||

| 15–30 | 0.12 ± 0.00 | 41.4 ± 0.7 | −26.8 | 74.1 ± 0.2 | ||

| 30–50 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 42.0 ± 0.7 | −26.9 | 94.7 ± 12.4 | ||

| 50–100 | 0.09 ± 0.00 | 43.3 ± 0.7 | −27.5 | 198.2 ± 12.8 | 2490 | |

| total | 428.7 ± 44.4 | 0.12 | ||||

| Cenote Yaxchen (n = 2) | ||||||

| 0–15 | 0.11 ± 0.05 | 41.8 ± 0.9 | −27.6 | 66.3 ± 27.0 | ||

| 15–30 | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 40.5 ± 0.2 | −27.4 | 54.7 ± 16.1 | ||

| 30–50 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 41.5 ± 1.2 | −27.9 | 68.8 ± 14.8 | ||

| 50–100 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 42.9 ± 0.2 | −27.4 | 180.2 ± 12.0 | ||

| 100–200 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 40.5 ± 0.4 | −27.6 | 371.5 ± 55.5 | ||

| 200–300 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 40.7 ± 0.1 | −28.6 | 374.4 ± 33.5 | ||

| 300–400 | 0.10 | 38.7 | −27.5 | 379.7 | ||

| 400–500 | 0.10 | 38.5 | −27.9 | 424.6 | 3040 | |

| total | 1517 ± 561.0 | 0.61 | ||||

| Casa Cenote (n = 4) | ||||||

| 0–15 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 35.6 ± 1.3 | −27.5 | 67.1 ± 6.5 | ||

| 15–30 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 39.5 ± 0.8 | −27.8 | 67.8 ± 2.8 | ||

| 30–50 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 36.8 ± 0.7 | −27.4 | 97.0 ± 5.2 | ||

| 50–100 | 0.14 ± 0.02 | 37.1 ± 1.8 | −27.8 | 259.5 ± 44.8 | ||

| 100–200 | 0.17 ± 0.05 | 33.8 ± 3.5 | −27.9 | 537.1 ± 81.8 | ||

| 200–300 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 33.8 ± 1.1 | −28.7 | 409.6 ± 39.9 | ||

| 300–400 | 0.20 ± 0.07 | 33.8 ± 1.1 | −27.9 | 457.1 ± 41.0 | ||

| 400–500 | 0.13 | 34.4 ± 11.0 | −28.1 | 488.1 | 3220 | |

| 500–600 | 0.11 | 38.7 | −29.3 | 426.9 | ||

| total | 1491 ± 548.6 | 0.66 | ||||

Because bulk density and SOC concentration were relatively consistent throughout all sampling sites (table 1), SOC stocks were highly correlated with depth (R2 = 0.89; p = 0.024, y = 471.3x + 24.8; electronic supplementary material, figure S1). The radiocarbon age of the deep peat samples was 2490 ± 30 BP (75 cm deep), 3040 ± 30 BP and 3220 ± 30 BP (450 cm deep) in Cenote Jaguar, Cenote Yaxchen and Casa Cenote, respectively. Correspondingly, SOC sequestration rates were estimated at 0.12, 0.60 and 0.66 Mg C ha−1 yr−1 (table 1).

4. Discussion

We found massive SOC stocks below mangroves of the cenotes close to the sea at Casa Cenote and Cenote Yaxchen, with a mean value of 1504 ± 13 Mg C ha−1. The SOC density was higher than stocks reported for other mangroves globally (199–1218 Mg C ha−1, means per country, [3]). These SOC stocks were also much higher than those for terrestrial vegetation, which range from 42 Mg C ha−1 in deserts to 344 Mg C ha−1 in boreal forests, and maximum values in boreal peat soils where SOC stocks can reach 1650 Mg C ha−1 [15,16]. Remarkably, one sampling site in Casa Cenote with 2792 Mg C ha−1 was the highest SOC stock for mangroves ever recorded (range of 46–2076 Mg C ha−1 in 190 plots distributed globally, [3]). The massive SOC from these cenotes is a result of high soil carbon content (greater than 38%) and deep soils, which have been preserved for millennia.

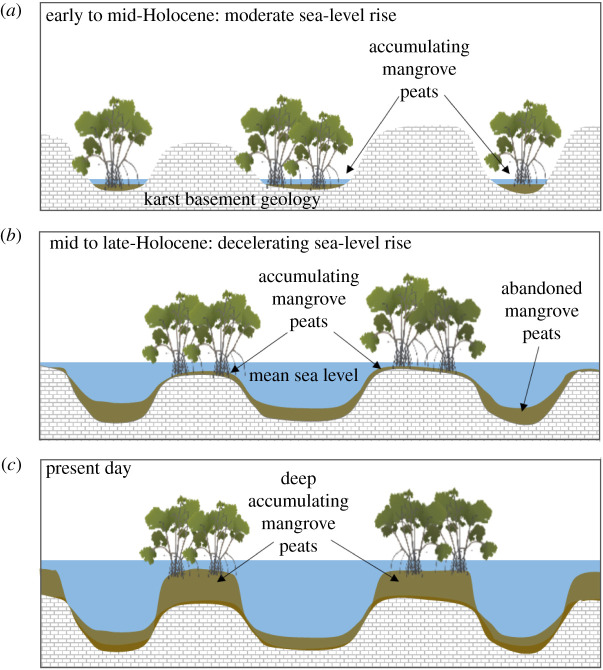

We propose that the high SOC stocks of these mangroves are associated with the sea-level history of the region. Globally, after the last glacial minimum, sea-level rise accelerated and then decelerated towards the mid and late-Holocene [17]. At the time of deceleration, conditions were favourable for mangrove expansion [18]. In Yucatan, rates of sea-level rise during the Holocene are uncertain but likely followed a similar pattern [19]. It is possible that during the early to mid-Holocene (11.7–8.2 thousand years BP), the sea level was lower than present levels but rising at rates beyond the capacity of mangroves to increase elevation through root production (figure 2). During the mid- to late-Holocene (8.2–4.2 thousand years BP), sea-level rise decelerated, providing conditions suitable for mangrove vertical growth through root addition and generation of new vertical space, commonly termed ‘accommodation space’, for mangroves to accumulate SOC [20,21]. The age of mangrove peats in this study corresponds to this period of deceleration and suggests SOC accumulation occurred at an average rate of 0.66 Mg C ha−1 yr−1 in coastal cenotes (Cenote Yaxchen and Casa Cenote) and 0.12 Mg C ha−1 yr−1 in inland cenotes (Cenote Jaguar). At present day, deep SOC continues to accumulate, probably at rates similar to those of current sea-level rise [20,21] (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mangrove peat accumulation in cenotes (a) during the early to mid-Holocene (11.7–8.2 thousand years BP) when sea level was low but rising at rates beyond the capacity to increase elevation in situ, (b) during the mid to late-Holocene (8.2–4.2 thousand years BP) when rates of sea-level rise decelerated and mangrove initiated vertical accretion through root production at similar rates to sea-level rise and (c) at present day when deep mangrove peats have developed, and vertical growth corresponds to sea-level rise.

The formation of large SOC stocks in these mangroves could also have been favoured by their biological and hydrological characteristics. First, mangroves in the Yucatan Peninsula are highly productive [22,23]; the high root productivity would have allowed for mangroves to accumulate vertically and keep pace with the rising sea [24]. Second, the preservation of accumulated SOC could have been facilitated by increasing submersion over the past millennia due to sea-level rise and the microtidal regime of the region (less than 2 m of tidal amplitude), which allows for these mangroves to be submerged, or at least wet, most of the time. The anoxic conditions caused by submersion limit decomposition and diagenesis and, thus, favour SOC preservation.

The SOC stocks in these cenotes are remarkable; however, rates of carbon sequestration are comparable to other mangroves which have lower SOC stocks. For example, SOC sequestration rates in riverine mangroves in southern Mexico are 0.4 to 1.8 Mg C ha−1 yr−1, but their SOC stocks are lower (less than 700 Mg C ha−1 to 1.5 m in depth) [25]. The rates reported in this study represent sequestration occurring over thousands of years synchronous with relative sea-level rise and corresponds to rates of vertical adjustment for other cenotes [20] and rates of root production for nearby mangroves (0.64 and 2.6 Mg C ha−1 yr−1) [23]. While rates of carbon accumulation of other mangroves may be higher, this likely occurs as accommodation space is rapidly infilled with mineral and organic material [24]. Thus, the higher rates of carbon accumulation cannot be sustained over thousands of years as vertical space becomes limited and accumulation increasingly corresponds to rates of relative sea-level rise. Critically, the carbon storage within these mangroves constitutes long-term carbon sequestration as SOC has been stored for thousands of years as evidenced by δ13C values consistent with a mangrove origin (27–29‰ [12]). Although the additional contribution of terrestrial C3 vegetation cannot be discarded, observations of the SOC in the field indicated that it was highly likely to be mangrove roots (see electronic supplementary material video).

The established relationship between SOC stock and depth provides a significant opportunity to reduce costs and effort when estimating SOC for mangroves associated with cenotes in this region (electronic supplementary material, figure S1). The massive and stable SOC stocks from this study also provide a strong basis for the inclusion of these mangroves in carbon projects. For instance, a carbon project in a mangrove forest in this region with peat of 2 m would have approximately 1000 Mg C ha−1, from which more than 50% could be lost if the site is converted to another land use [26]. If deforestation rates of the area are 0.1% annually, a conservation project of only 100 ha (the size of the Yaxchen cenotes complex) for 100 years could offset almost 13 341 Mg of CO2eq every year [27], which corresponds to over US$13 000 a year within current carbon prices (expecting a value of US$10 per Mg CO2eq in an international market), a considerable amount of money for a rural community in Mexico. This economic incentive could also be complemented through other payments for ecosystem services given the high endemicity of species within these cenotes [6] and important cultural values for the Mayan communities, which could be included as part of the Sustainable Development Goals for Mexico.

The exceptionally large SOC stocks stored in these unique ecosystems are threatened by poorly planned tourism, excessive water extraction and groundwater pollution. The latter is caused by the lack of water treating infrastructure in the region, which mostly relies on septic treatments that can leach nitrogen into the aquifer [28]. Contemporary and future sea-level rise would likely increase saltwater intrusion and may favour the expansion of mangroves in new habitats that were not previously inundated. Increased phosphorus in seawater (a key limiting nutrient for these mangroves) could further boost productivity [22,23]. However, urbanization and road construction could significantly impede mangrove inland migration and alter the hydrology of the groundwater network, causing degradation or even massive deaths. The fate of carbon accumulation by existing mangroves is dependent on future rates of sea-level rise, as the threshold of tolerance for vertical adjustment is very likely to be exceeded at rates greater than 5.2 mm yr−1 [18]. Thus, the capacity of these mangroves to continue accumulating SOC may become limited at high rates of sea-level rise. Avoiding emissions from these carbon hotspots could be achieved by protecting hydrological networks, avoiding clearing, facilitating inland migration and conducting hydrological restoration in degraded forests including those damaged by tropical storms [29]. These activities could provide economic incentives to the Mayan communities for the sustainable management of cenotes within the Yucatan Peninsula.

Acknowledgements

We thank Esteban Marcellin and Gibran Hoffmann Bonilla for fieldwork assistance and Ejido Jacinto Pat, Dos Ojos Cenotes Park and Ejido Jose María Pino Suárez for providing access to the cenotes.

Ethics

There are no ethical concerns in this study. All fieldwork was carried out with the permission of the owners of the cenotes and in collaboration with a local NGO.

Data accessibility

Data are available from the Dryad Digital Repository: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.cz8w9gj2x [30].

Authors' contributions

M.F.A., N.S.S. and K.R. designed the study; M.F.A. and O.T.T. conducted fieldwork; N.S. conducted laboratory work; all co-authors contributed to the interpretation of the data; M.F.A. wrote the first manuscript and all co-authors contributed with revision of subsequent drafts. Authors agree to be held accountable for the content therein and approve the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research was funded by the Queensland Government through the Advance Queensland Fellowship granted to M.F.A. and through a Cátedra Fellowship (project 236) from the National Council of Science and Technology (CONACYT) to N.S.S.

References

- 1.Murdiyarso D, et al. 2015. The potential of Indonesian mangrove forests for global climate change mitigation. Nat. Clim. Chang. 5, 1089–1092. ( 10.1038/nclimate2734) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamilton SE, Friess DA. 2018. Global carbon stocks and potential emissions due to mangrove deforestation from 2000 to 2012. Nat. Clim. Chang. 8, 240–244 ( 10.1038/s41558-018-0090-4) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kauffman J, et al. 2020. Total ecosystem carbon stocks of mangroves across broad global environmental and physical gradients. Ecol. Monogr. 90, e01405. ( 10.1002/ecm.1405) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lovelock CE, Duarte CM. 2019. Dimensions of Blue Carbon and emerging perspectives. Biol. Lett. 15, 20180781. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2018.0781) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perry E, Velazquez-Oliman G, Marin L. 2002. The hydrogeochemistry of the karst aquifer system of the northern Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. Int. Geol. Rev. 44, 191–221. ( 10.2747/0020-6814.44.3.191) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmitter-Soto J, et al. 2002. Hydrogeochemical and biological characteristics of cenotes in the Yucatan Peninsula (SE Mexico). Hydrobiologia 467, 215–228. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hernández-Terrones L, Rebolledo-Vieyra M, Merino-Ibarra M, Soto M, Le-Cossec A, Monroy-Ríos E. 2011. Groundwater pollution in a karstic region (NE Yucatan): baseline nutrient content and flux to coastal ecosystems. Water Air Soil Pollut. 218, 517–528. ( 10.1007/s11270-010-0664-x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adame MF, Kauffman JB, Medina I, Gamboa JN, Torres O, Caamal JP, Reza M, Herrera-Silveira JA. 2013. Carbon stocks of tropical coastal wetlands within the karstic landscape of the Mexican Caribbean. PLoS ONE 8, e56569. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0056569) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.CONAGUA-SMN. 2018. Comision Nacional del Agua- Servicio Meteorologico Nacional (National Water Commission-National Secretary of Meteorology). See http://smn.cna.gob.mx/es/ (accessed on 20 March 2018).

- 10.Kauffman JB, Donato DC. 2012. Protocols for the measurement, monitoring and reporting of structure, biomass and carbon stocks in mangrove forests. CIFOR, Working paper 86. Bogor, Indonesia.

- 11.Adame MF, Fry B. 2016. Source and stability of soil carbon in mangrove and freshwater wetlands of the Mexican Pacific coast. Wetl. Ecol. Manag. 24, 129–137. ( 10.1007/s11273-015-9475-6) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adame MF, Fry B, Gamboa JN, Herrera-Silveira JA. 2015. Nutrient subsidies delivered by seabirds to mangrove islands. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 525, 15–24. ( 10.3354/meps11197) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramsey B. 2009. Bayesian analysis of radiocarbon dates. Radiocarbon 51, 337–360. ( 10.1017/S0033822200033865) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reimer PJ, Bard E, Bayliss A, Beck JW, Blackwell PG, Bronk C, Caitlin R, Hai EB, Edwards RL. 2021. INTCAL13 and MARINE13 radiocarbon age calibration curves 0–50 000 years cal BP. Radiocarbon 55, 1869–1887. ( 10.2458/azu_js_rc.55.16947) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prentice IC, et al. 2001. The carbon cycle and atmospheric carbon dioxide. In Climate change 2001: the scientific basis. Contribution of working group I to the third assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change (eds Houghton JT, et al.), pp. 185–237. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beilman DW, Vitt DH, Bhatti JS, Forest S. 2008. Peat carbon stocks in the southern Mackenzie River Basin: uncertainties revealed in a high-resolution case study. Glob. Chang. Biol. 14, 1221–1232. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2008.01565.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rogers K, et al. 2019. Wetland carbon storage controlled by millennial-scale variation in relative sea-level rise. Nature 567, 91–95. ( 10.1038/s41586-019-0951-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saintilan N, Khan NS, Ashe E, Kelleway JJ, Rogers K, Woodroffe CD, Horton BP. 2020. Thresholds of mangrove survival under rapid sea level rise. Science 368, 1118–1121. ( 10.1126/science.aba2656) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khan NS, et al. 2017. Drivers of Holocene sea-level change in the Caribbean. Quat. Sci. Rev. 155, 13–36. ( 10.1016/j.quascirev.2016.08.032) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Collins SV, Reinhardt EG, Werner CL, Le Maillot C, Devos F, Rissolo D. 2015. Late Holocene mangrove development and onset of sedimentation in the Yax Chen cave system (Ox Bel Ha) Yucatan, Mexico: implications for using cave sediments as a sea-level indicator. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 438, 124–134. ( 10.1016/j.palaeo.2015.07.042) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Torrescano N, Islebe GA. 2006. Tropical forest and mangrove history from southeastern Mexico: a 5000 yr pollen record and implications for sea level rise. Veg. Hist. Archaeobot. 15, 191–195. ( 10.1007/s00334-005-0007-9) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adame MF, et al. 2013. Drivers of mangrove litterfall within a karstic region affected by frequent hurricanes. Biotropica 45, 147–154. ( 10.1111/btp.12000) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adame MF, Teutli C, Santini NS, Caamal JP, Zaldívar-Jiménez A, Hernández R, Herrera-Silveira JA. 2014. Root biomass and production of mangroves surrounding a karstic oligotrophic coastal lagoon. Wetlands 34, 479–488. ( 10.1007/s13157-014-0514-5) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKee KL, Cahoon DR, Feller IC. 2007. Caribbean mangroves adjust to rising sea level through biotic controls on change in soil elevation. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 6, 545–556. ( 10.1111/j.1466-8238.2007.00317.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adame SNS, Tovilla C, Vázquez-Lule A, Castro L, Guevara M. 2015. Carbon stocks and soil sequestration rates of tropical riverine wetlands. Biogeosciences 12, 3805–3818. ( 10.5194/bg-12-3805-2015) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sasmito SD, Taillardat P, Clendenning JN, Cameron C, Friess DA, Murdiyarso D, Hutley LB. 2019. Effect of land-use and land-cover change on mangrove blue carbon: a systematic review. Glob. Chang. Biol. 25, 4291–4302. ( 10.1111/gcb.14774) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adame BCJ, Bejarano M, Herrera-Silveira JA, Ezcurra P, Kauffman JB, Birdsey R. 2018. The undervalued contribution of mangrove protection in Mexico to carbon emission targets. Conserv. Lett. 11, e12445. ( 10.1111/conl.12445) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alcocer J, Lugo A, Marín LE. 1988. Hydrochemistry of waters from five cenotes and evaluation of their suitability for drinking-water supplies, northeastern Yucatan, Mexico. Hydrogeol. J. 6, 293–301. ( 10.1007/s100400050152) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adame MF, et al. 2021. Future global emission from mangrove forest loss. Glob. Chang. Biol. ( 10.1101/2020.08.27.271189) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adame MF, Santini NS, Torres-Talamante O, Rogers K. 2021. Data from: Mangrove sinkholes (cenotes) of the Yucatan Peninsula, a global hotspot of carbon sequestration. Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.cz8w9gj2x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Adame MF, Santini NS, Torres-Talamante O, Rogers K. 2021. Data from: Mangrove sinkholes (cenotes) of the Yucatan Peninsula, a global hotspot of carbon sequestration. Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.cz8w9gj2x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the Dryad Digital Repository: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.cz8w9gj2x [30].