Abstract

Grasping and manipulation are fundamental ways for many creatures to interact with their environments. Different morphologies and grasping methods of “grippers” are highly evolved to adapt to harsh survival conditions. For example, human hands and bird feet are composed of rigid frames and soft joints. Compared with human hands, some plants like Drosera do not have rigid frames, so they can bend at arbitrary points of the body to capture their prey. Furthermore, many muscular hydrostat animals and plant tendrils can implement more complex twisting motions in 3D space. Recently, inspired by the flexible grasping methods present in nature, increasingly more bio‐inspired soft grippers have been fabricated with compliant and soft materials. Based on this, the present review focuses on the recent research progress of bio‐inspired soft grippers based on impactive gripping. According to their types of movement and a classification model inspired by biological “grippers”, soft grippers are classified into three types, namely, non‐continuum bending‐type grippers, continuum bending‐type grippers, and continuum twisting‐type grippers. An exhaustive and updated analysis of each type of gripper is provided. Moreover, this review offers an overview of the different stiffness‐controllable strategies developed in recent years.

Keywords: bio‐inspired materials, soft robotics, soft grippers, soft actuators, variable stiffness, smart materials

According to movement ways and the classification model inspired by biological “grippers”, the soft grippers are divided into three types: non‐continuum bending‐type grippers, continuum bending‐type grippers, and continuum twisting‐type grippers. For each type of gripper, material properties, device architectures, and manipulation strategies are systematically explored and analyzed. In addition, an overview of stiffness‐controllable strategies developed in recent years is proposed.

1. Introduction

For creatures, including both animals and plants, grasping and manipulation are essential ways to interact with their environments. Many animals and plants usually take advantage of their bodies, such as human hands, bird feet, elephant trunks, octopus tentacles, Drosera bodies, and plant tendrils, as their end effectors to achieve many interaction‐based tasks, including hunting, nest building, and feeding.[ 1 ] The morphologies and functions of these end effectors have evolved in entirely different ways to adapt to environmental changes. For example, although octopus tentacles are flexible enough to implement complex twisting movements, octopuses have evolved suckers on their tentacles to ensure the stability of grasping.

Unlike the grippers of creatures, traditional robotic grippers, the earliest imitations of biological end effectors, are mainly composed of rigid frames and joints. They are widely applied in industrial robots, aeronautics, and humanoid robots, such as the famous ASIMO series. Actuators can accurately transfer power to manipulate components via traditional transmission mechanisms, such as gear and link transmission mechanisms. Traditional robotic grippers with high structural stiffness generally have the merits of a high load‐bearing capacity, fast operation speed, and precise position control. However, the high structural stiffness also limits their ability to deform elastically and adapt to target objects. More importantly, it is unsafe for humans to interact with robotic grippers with high structural stiffness; for instance, workers are not allowed to enter into the work area of robotic arms to avoid danger.[ 2 ]

To overcome the defects and disadvantages inherent in traditional rigid grippers, increasingly more researchers have begun to apply soft robotic technologies in the field of grippers and manipulators. These are usually called “soft grippers” or “soft manipulators,” which allow for increasing compliance and adaptability to accomplish specific tasks. The softness of robots is represented in various aspects, such as soft textures, deformable materials, elastic actuators, and soft movements, which are friendly for the manipulated object.[ 3 ] Like their natural counterparts, soft grippers are compliant and flexible, and have better adaptability to various target objects. In addition, compared with traditional rigid grippers, soft grippers based on soft robotics could provide an opportunity to bridge the gap between facilities and people.[ 2 ] They are characterized by improved safety, especially in scenarios that involve human interaction. For example, soft cooperative robots can be safely used in elderly and handicapped care. Additionally, soft robots for use in minimally invasive surgery inflict less damage to the human body.

Biology has long been a blueprint of inspiration for soft robotics.[ 2 ] The softness and body compliance present in biology exhibit the advantage of the reducing complexity in environmental interactions.[ 4 ] The material compositions, structures, and movement methods of creatures with the ability to grasp and manipulate have been studied as counterparts to soft grippers. After a long evolutionary process, the grasping methods of creatures can be roughly divided into two types, the first of which is adhesion grasping via the use of adhesives between the end effectors and target objects.[ 5 ] The pangolin is a representative animal that implements this grasping method, and exploits its sticky tongue to gather white ants. The other type is impactive grasping, which is the primary grasping manner in nature. Impactive grasping includes non‐continuum bending‐type grasping represented by human hands, continuum bending‐type grasping represented by the body of the Drosera, and continuum twisting‐type grasping represented by plant tendrils. In this paper, the impactive grasping classification of creatures is equally applied to the classification of impactive soft grippers, and more details are provided in Section 3.

In addition to compliant movement methods, the softness of components is another typical feature of soft grippers. non‐continuum bending‐type grippers (NBGs) usually consist of rigid frames and soft joints, which compose a rigid‐flexible coupling system. In contrast, CBGs and CTGs consist almost completely of soft materials that play an essential role, and their material characteristics influence the manifestation of the entire system. The most frequently used compliant materials include soft silicone elastomer, polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), and rubber, which are used as the bodies of soft grippers. The Young's modulus of these compliant materials is similar to that of the biological components of natural organisms, such as skin, muscle tissue, and cartilage, which have moduli on the order of 102–106 Pa.[ 2 , 6 ] This is the foremost reason why soft grippers are biologically compatible and considered to be safe for man‐machine interaction.

The addition of soft materials in the body makes soft grippers compliant and flexible. Thus, soft actuators can be integrated into the main body of grippers to allow them to implement bending or twisting motions. Different from those of traditional rigid grippers, the actuators used in soft grippers are also compliant, and can therefore deform with the grippers. In addition to the most widely used soft pneumatic actuators (SPAs) and cable‐driven actuators, the actuators of soft grippers can be made of shape memory polymers and shape memory alloys, which are temperature‐responsive. Electroactive polymers include dielectric elastomers, liquid‐crystal elastomers, and ionic polymer metal composites, which can respond to an applied electric field. Actuators can also be made of responsive hydrogels and many other new intelligent materials, which are not only compliant but also able to respond to pH, electromagnetic fields, temperature, light, and chemicals.

Soft grippers with variable stiffness have also become another research hotspot. Along with the vigorous development of soft robotics technology in recent years, many stiffness‐controllable strategies, such as the jamming effect, electrorheological fluids, magnetorheological fluids, low‐melting materials, and shape memory polymers, can be adopted in soft grippers. Soft grippers can easily switch between two states by controlling their stiffness; the low‐stiffness state has better flexibility and compliance, while the high‐stiffness state has the advantages of higher structural rigidity and a higher load capacity.

Some reviews on soft grippers have been published.[ 1 , 7 ] However, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, discussions on the development of impactive soft grippers based on a novel biologically‐inspired classification, are relatively rare. In this review, the recent developments of impactive soft grippers are discussed from a new perspective. In Section 2, inspired by creatures in nature with grasping abilities, the classification of impactive soft grippers is elaborated. In Section 3, soft grippers based on different soft actuators are reviewed. In Section 4, stiffness control strategies of impactive soft grippers are discussed. Finally, persistent challenges, future developments, and potential applications of impactive soft grippers are also proposed.

2. Biologically‐Inspired Manipulation Modes for Soft Grippers

The traditional rigid robotic manipulators (RRMs), which have rigid limbs and hinge joints, have been widely applied, especially in the fields of industrial and anthropomorphic robots. Via finite‐time control,[ 8 , 9 , 10 ] terminal sliding mode control,[ 11 , 12 , 13 ] and many other types of algorithms, RRMs have achieved high‐precision and high‐stability performance. As shown in Figure 1 , the Gifu Hand II is representative of RRMs, and is integrated with servomotors and tactile sensors that allow it to perform dexterous object manipulations.[ 14 ] However, its precise position control and rigid body limit its ability to adapt to various operated objects and safely interact with humans in some scenarios, such as healthcare and cooperative human assistance.[ 15 ]

Figure 1.

The comparison of grippers with the different driving modes, including rigid robotic manipulators (RRM), non‐continuum bending‐type gripper (NBG), continuum bending‐type gripper (CBG), and continuum twisting‐type gripper (CTG) and their typical representatives or counterparts in nature, which include the Gifu Hand II (Reproduced with permission.[ 14 ] Copyright 2012, IEEE), the human hand, the Drosera, and the octopus tentacle. It should be noted that “white components” are regarded as rigid, and “gray components” are regarded as flexible.

Compared with RRMs, the grippers of muscular hydrostat animals, plant tendrils, and boa constrictors in nature are more flexible and can adapt to contact with all kinds of shapes, surface textures, and mechanical properties. Moreover, they have an infinite number of degrees of freedom (DOFs) that allow them to bend or twist unconstrained in 3D space. Muscular hydrostat structures are found in animals, such as elephant trunks, octopus tentacles,[ 16 , 17 ] and the tongues of many animals.[ 18 , 19 ] The large and convoluted extension movements of muscular hydrostat structures, such as elongation, shortening, bending, and torsion, depend on their internal muscle fibers that are oriented in three different directions: parallel to the long axis, perpendicular to the long axis, and wrapped obliquely around the long axis.[ 20 , 21 ] Moreover, the stiffness of muscular hydrostat structures can be increased by contracting muscle or connective tissue, despite a lack of skeletal support.[ 22 ] The dexterity and load‐bearing capabilities of many animals can be ascribed to their muscular hydrostat structures,[ 23 ] which have also provided inspiration for the design of soft grippers. Plant tendrils are another flexible structure that can respond to variable ambient conditions and implement flexible grasping movements via bending and twisting. Their flexible physiological structure allows them to move to more profitable ecological niches with abundant sunshine and other advantages.[ 24 ] Another advantage of plant tendrils is that their coiling structure can be regarded as an elastic rod, which enhances their tolerance against external impacts.[ 25 ] It has been found that the internal strain mismatch within tendril tissues and the asymmetric contraction of an internal fiber ribbon with specialized cells are the leading causes of the generation of bending and twisting movements.[ 26 , 27 , 28 ] Enlightened by the asymmetric contraction structure, many tendril‐like structures that can flexibly implement bending and twisting motions have been proposed.[ 29 , 30 ] The boa constrictor is a flexible ambush predator with an exceptional hunting pattern; it captures prey with its body, and proceeds to constrict the prey until death. Moreover, monkeys are able to keep their hands free for manipulation by using their prehensile tails to hold onto branches, and the prehensile tails of possums have the same function.[ 31 ] In this paper, biological grippers with the grasping modes of muscular hydrostat animals, plant tendrils, and boa constrictors are referred to as biological continuum twisting‐type grippers (BCTGs).

The characteristics of human hands in terms of gripping are between those of traditional RRMs and tendril‐type grippers. Compared with RRMs, human hands are more flexible and compliant, whereas compared with tendril‐type grippers, they are more precise, stable, and have an improved loading capacity, which is attributed to their rigid internal structures (phalanges). As the bridge between humans and the outside world, human hands have always been an inspiration for robotic gripper design,[ 32 ] which are composed of 27 bones, about 40 muscles, and more than 21 DOFs.[ 33 ] They are able to perform complex and varied tasks by using an effective integrated system of mechanisms, sensors, actuators, and control functions.[ 34 ] The joints of human hands have complex structures, such as ligaments and tendons, which exhibit passive compliance. The grasping modes of human hands are usually divided into two types, namely the precision grasping mode that emphasizes dexterity and sensitivity, and the power mode that emphasizes security and stability.[ 35 ] Soft bionic hands driven by flexible actuators are usually designed for wrap grasping and operation in the power mode. This is because the control of the compliant structure is complicated, and the precision grasp mode is usually realized in rigid industrial grippers. In this paper, biological grippers with grasping modes similar to those of human hands are referred to as biological non‐continuum bending‐type grippers (BNBGs).

In nature, some creatures can achieve planar bending motion like human hands, whereas, in contrast to human hands, they have an infinite number of rotational DOFs in the plane. Still, they cannot twist in 3D space like muscular hydrostat animals and plant tendrils. Drosera is a typical representative of this; it is a carnivorous plant that can capture and digest insects by using sticky secretions on the surfaces of its leaves. When insects are attracted by the sweet mucilage, Drosera can rapidly bend its body to capture them.[ 36 ] The bending force originates from osmotic actuation (rapid cell expansion due to an increase of internal cell pressure),[ 37 ] which is capable of generating effective movements despite deficient power.[ 38 ] After this, it takes hours to reset the wrapping movement.[ 39 ] In this paper, biological grippers with the grasping modes like those of Drosera and other creatures that can continuously bend to achieve planar grasping motion are referred to as biological continuum bending‐type grippers (BCBGs).

In summary, impactive biological grippers can be categorized as BCTGs, BNBGs, or BCBGs. As shown in Figure 1, biological grippers include BNBGs represented by human hands, BCBGs represented by Drosera, and BCTGs represented by octopus tentacles. Their flexibility and compliance increase accordingly, while their precision and stability weaken successively.

BNBGs, which are represented by human hands, usually have rigid limbs and soft joints that provide relatively precise control and the ability to achieve stable and robust movement. In contrast, BCTGs, which are represented by octopus tentacles, have an infinite number of DOFs, which allow them to twist unconstrained in 3D space. Consequently, BCTGs exhibit the best performance in terms of flexibility and compliance. BCBGs, which are represented by Drosera, also have an infinite number of DOFs, but they often achieve only planar bending motion. Thus, the performance of BCBGs is between those of BNBGs and BCTGs. After hundreds of millions of years of evolution, these impactive grasping modes have ensured that creatures can interact with nature efficiently, and are worth investigating for application in soft robotic grippers.

In this paper, according to the proposed classification of biological grippers, impactive grippers are also divided into three categories, namely NBGs, CBGs, and CTGs (Figure 1). Moreover, the variable stiffness of soft grippers is considered.

All robotic grippers can be categorized as one of four basic types, namely impactive, ingressive, astrictive, and contigutive robotic grippers.[ 40 ] Their descriptions and typical representatives are provided in Table 1 .[ 41 ] In this paper, focus is placed on soft grippers based on the impactive gripping method. Impactive gripping usually requires the motion of solid jaws to produce the necessary grasping forces that are applied to the object from two or more directions.[ 41 ] Physically grasping an object via direct impact is the most direct way to realize capture and manipulation, so impactive gripping is the most popular method used in robotic grippers.

Table 1.

Stiffness‐controllable strategies and their features

| Gripping method | Description | Typical representatives |

|---|---|---|

| Impactive | Physically grasp by direct impact upon the object | Jaws, clamps, and pinch mechanisms |

| Ingressive | Physically penetrate the surface of the object | Pins, hackles, and hook |

| Astrictive | Attractive forces applied to the objects surface | Vacuum suction, magnetoadhesion,and electroadhesion |

| Contigutive | Requiring direct contact for adhesion to take place | Chemical and thermal adhesion |

The astrictive gripping method is also widely applied in soft grippers. Adhesive grippers can take the place of impactive grippers to accomplish tasks in some specific working situations, such as underwater working environments and other situations that require the grasping of objects with a smooth surface. Moreover, while the impactive gripping method can result in high surface pressures between the object and contact points, which could cause damage to the operated objects,[ 41 ] the astrictive gripping method avoids this disadvantage. Many reviews on the astrictive gripping method have been conducted; for example, Jeffrey et al. and Li et al.[ 42 , 43 ] discussed dry adhesive materials and their applications, Shintake et al.[ 44 ] summarized soft grippers with electro adhesion, Croll et al.[ 5 ] reviewed switchable adhesives for multifunctional interfaces, and Hofman et al.[ 45 ] explored underwater adhesives. The present review considers only soft grippers based on the impactive gripping method.

3. Soft Grippers Based on the Impactive Gripping Method

In this section, soft grippers (referring to soft grippers based on the impactive gripping method) are discussed. Figure 2 presents an abridged overview of NBGs, CBGs, and CTGs, which have different features and application scenarios, just as their counterparts in nature.

Figure 2.

Non‐continuum bending‐type grippers (NBGs): A soft gripper with “pouch motors.” Reproduced with permission.[ 46 ] Copyright 2015, Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. A soft micro‐gripper with four fingers. Reproduced with permission.[ 47 ] Copyright 2009, IEEE. A cable‐driven manipulation with elastic finger joints. Reproduced with permission.[ 48 ] Copyright 2017, SAGE Publications. A gripper is driven by a single cable tendon. Reproduced with permission.[ 49 ] Copyright 2015, Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. An omni‐purpose soft gripper incorporated with soft fingers and a suction cup. Reproduced with permission.[ 50 ] Copyright 2019, IEEE. A wireless folding gripper. Reproduced with permission.[ 51 ] Copyright 2017, The American Association for the Advancement of Science. A soft hand with a good bending capacity. Reproduced with permission.[ 52 ] Copyright 2016, Elsevier. A bionic finger is driven by IPMC actuators. Reproduced with permission.[ 53 ] Copyright 2006, IOP Publishing. Continuum bending‐type grippers (CBGs): A flexible pressure‐driven gripper. Reproduced with permission.[ 54 ] Copyright 1990, Cambridge University Press. A soft gripper is used to grasp aquatic mollusk. Reproduced with permission.[ 55 ] Copyright 2019, The American Association for the Advancement of Science. A precharged pneumatic soft gripper. Reproduced with permission.[ 56 ] Copyright 2018, Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. A soft wearable robot for hands. Reproduced with permission.[ 57 ] Copyright 2019, Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. A gripper is driven by SMPs. Reproduced with permission.[ 58 ] Copyright 2015, Springer Nature. Bidirectional SMPs. Reproduced with permission.[ 59 ] Copyright 2013, John Wiley and Sons. An SMA‐based soft gripper. Reproduced with permission.[ 60 ] Copyright 2017, Elsevier. A gripper with SMA springs. Reproduced with permission.[ 61 ] Copyright 2019, IOP Publishing. A soft gripper based on DEME. Reproduced with permission.[ 62 ] Copyright 2007, AIP Publishing. Hydraulically amplified self‐healing electrostatic gripper. Reproduced with permission.[ 63 ] Copyright 2018, The American Association for the Advancement of Science. A microgripper is driven by IPMC. Reproduced with permission.[ 101 ] Copyright 2008, Springer Nature. A Venus flytrap‑inspired microrobot consists of two IPMC actuators. Reproduced with permission.[ 65 ] Copyright 2015, Springer Nature. A micrometer‐scale, light‐driven plier. Reproduced with permission.[ 66 ] Copyright 2020, John Wiley and Sons. Electrically controlled soft gripper with three LCE tubular actuators. Reproduced with permission.[ 67 ] Copyright 2019, The American Association for the Advancement of Science. A polymer electrothermal hand. Reproduced with permission.[ 68 ] Copyright 2015, American Chemical Society. pH‐responsive hydrogel‐based soft micro‐robot. Reproduced with permission.[ 69 ] Copyright 2016, IOP Publishing. Continuum twisting‐type grippers (CTGs): A gripper with multiple bending modes. Reproduced with permission.[ 70 ] Copyright 2012, John Wiley and Sons. A wearable mobile manipulation. Reproduced with permission.[ 71 ] Copyright 2019, Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. A helical soft pressure‐driven actuator. Reproduced with permission.[ 72 ] Copyright 2019, Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. A soft micro‐gripper. Reproduced with permission.[ 73 ] Copyright 2015, Springer Nature. Cable‐driven biomimetic gripper. Reproduced with permission.[ 74 ] Copyright 2012, IOP Publishing. A soft arm inspired by the octopus. Reproduced with permission.[ 75 ] Copyright 2012, Taylor & Francis. A completely soft octopus‐like robotic arm. Reproduced with permission.[ 76 ] Copyright 2012, IEEE. A soft tendril‐inspired twining‐type gripper. Reproduced with permission.[ 77 ] Copyright 2018, American Chemical Society.

CBGs account for a considerable proportion (about 46%) of soft grippers. By comparison, NBGs and CTGs respectively account for 21% and 33% of soft grippers (these statistics are based on papers referenced in this review, which were published between 1990–2020). This indicates that researchers are more inclined to use CBGs, which are characterized by simple structures, easy processing, and more convenience for the application of soft actuators.

In contrast, the manipulation modes of creatures in nature with different grasping abilities are almost all concentrated on the non‐continuum bending‐type and continuum twisting‐type modes. The continuum bending‐type grippers like those of Drosera are relatively rare in nature. This indicates that the selection mechanism of natural evolution is more inclined to grant survival to creatures with grippers whose features are more prominent. For instance, creatures with the non‐continuum bending‐type grasping mode, represented by human hands and bird feet, have the best high‐precision and high‐stability performance in nature. On the contrary, creatures with the continuum twisting‐type grasping mode, represented by plant tendrils and octopus tentacles, have the advantages of flexibility and compliance. The continuum bending‐type grasping mode is seemingly more balanced, as shown in Figure 2. Still, due to their insufficient competitiveness, creatures with this grasping mode are easily eliminated in fierce competition. However, compared with the non‐continuum bending‐type and continuum twisting‐type grasping modes, the continuum bending‐type grasping mode usually requires more simple structures and control algorithms, which is suitable for some plants like Drosera and the sporangium of the fern. All three grasping modes have different features that are worth investigating to consider their applications in soft grippers.

In nature, the BNBGs, which are represented by human hands and bird feet, usually have rigid frameworks and flexible joints covered by ligament tissue. Similar to their counterparts, the flexible joints of NBGs, which exploit the compliance of soft materials to realize bending motion similar to that of human hands, are not hinges characterized by DOFs of rotation. The compliance of joints will enhance the flexibility of the gripper and its adaptability to objects with complex geometries. Moreover, the existence of rigid frameworks allows for a stable pinch grasp. As shown in Figure 1, NBGs include another kind of grasping mode, namely enveloping grasp. The gripper can choose the proper grasping mode depending on the position, geometric shape, and size of the grasped object.[ 78 ] The bending motions of soft joints are usually passive, and the joints are bent by the soft actuators, such as cable‐driven actuators. Many soft joints are flexible connections and simultaneously act as soft actuators. Compared with those of CBGs and CTGs, the stability and accuracy of the motion of NBGs are usually better due to the existence of a rigid framework, whereas their flexibility and compliance are insufficient. Moreover, due to the similarity to the structure of human hands, NBGs are an excellent choice for bionic hands for applications in the fields of anthropomorphic robots and artificial limbs.

Due to the usual movement mode of CBGs, namely continuous planar bending, which is consistent with the primary motion methods of soft actuators, almost all soft actuators can be used in CBGs. Like their counterparts, which are represented by Drosera, CBGs usually have a continuous and asymmetric structure that can be found in different types of soft actuators. This is one of the reasons why CBGs have been applied extensively in daily life. Unlike the structures of NBGs, which are integrated with rigid frameworks and compliant joints, there are typically no rigid structures in CBGs. Instead, CBGs have one or more soft and continuum fingers characterized by better flexibility and compliance. Like NBGs, most CBGs also have two kinds of grasping modes, namely pinch grasp and enveloping grasp. However, due to the absence of a rigid structure, the load‐holding capacity is relatively low compared with that of NBGs; thus CBGs are more suited to work in the enveloping grasping mode in most cases. On the other hand, the continuum structure is an obstacle to independent movement in specific parts of the finger, which is probably the greatest challenge of CBGs. Moreover, researchers have integrated some new materials and structures into CBGs to provide them with exceptional performance, such as self‐healing materials, which can provide a self‐repairing quality, an origami structure that introduces a novel driving method, and other biomimetic constructions that can significantly improve the performance of CBGs.

Twisting motion is an essential way for many animals and plants to interact with their survival circumstances. Different animals and plants wind around objects by using various patterns that allow them to reliably capture the target object.[ 79 ] Twisting motions of animals and plants are common in nature, and include those by octopus tentacles, elephant trunks, the tongues of many mammals, and vines. Generally, efficient and reliable manipulation can be achieved via a twisting motion with only one gripper, which has often become the imitation object of many CTGs. Compared with NBGs and CBGs, CTGs have more advantages in terms of flexibility and compliance. They can better adapt to objects with complex geometries and achieve reliable grasping by using as few executors as possible. In fact, many CTGs only need one executor to complete a grasping job, while CBGs, as their competitors, require at least two executors to implement grasping movements. However, to achieve a twisting motion, complex structures and control algorithms are needed. The soft actuators that can only achieve bending motion may need to be redesigned for application in twisting‐type grippers. The complexity of a controllable twisting motion remains a challenge for the actuators used in CTGs. Moreover, due to their unique movement form, CTGs can only operate in the enveloping grasping mode, which could limit their applications in many use situations. For example, as shown in Figure 1, it is difficult for CTGs to grasp flat objects because they are difficult to envelop. At present, soft pneumatic actuators and cable‐driven actuators might be better choices for CTGs. Some smart materials that can generate a twisting motion via asymmetric structures have also been rapidly developed.

Generally, soft grippers need to deform or generate bending and twisting motions. Soft actuators play a crucial role in this process and are applied in different soft grippers. The applied soft grippers include soft pneumatic actuators (SPAs), cable‐driven actuators, dielectric elastomer actuators (DEAs), ionic polymer metal composites (IPMCs), shape memory alloys (SMAs), shape memory polymers (SMPs), liquid‐crystal elastomers (LCEs), and smart materials. Although actuators based on stimuli‐responsive smart materials have been developed, the traditional soft actuators like SPAs and cable‐driven actuators are still the most widely used in soft grippers. For example, cable‐driven actuators are the most widely used in NBGs. Compared with other actuators, their working pattern is more similar to that of human hands. Due to their intrinsic bending characteristics, almost all types of soft actuators could be applied in CBGs, which is why CBGs are the most popular type of soft gripper. The continuum twisting motion is more complicated than the continuum bending motion, and remains a challenge for soft actuators. More than 90% of CTGs are based on SPAs and cable‐driven actuators. While some programmable polymers and hydrogel architectures can also implement twisting motions, their movement methods are predetermined by asymmetric structures, which results in low‐flexibility control. Further, they do not provide enough gripping force to pick up heavy objects.

In this section, soft grippers based on different actuators are discussed, each of which is categorized by its manipulation mode, namely NBGs, CBGs, and CTGs. An overview of the many function parameters for soft grippers is presented in Table 2 . For each type of gripper, its material properties, device architectures, and manipulation strategies are systematically explored and analyzed in the subsequent subsections.

Table 2.

The comparison of the soft actuators used in soft grippers

| Category | Driving forms | Minimum response time [s] | Gripper size [cm] | Maximum load [g] | Application scenarios |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPAs | Compressed air | 0.1[ 80 ] | 0.5[ 47 ]–≈19.3[ 46 ] a) | ≈131[ 46 ] b) | NBGs |

| ≈4[ 81 ]–20[ 82 ] | 546[ 83 ] | CBGs | |||

| 0.5[ 73 ]–148[ 84 ] | 89 000[ 85 ] | CTGs | |||

| Cable‐Driven Actuators | Pulling force | N/A | ≈6[ 86 ]–15.8[ 48 ] | 22 000[ 87 ] | NBGs |

| 12[ 56 ]–≈19.3[ 57 ] a) | 1500[ 88 ] | CBGs | |||

| 25[ 89 ] – 45[ 90 ] | 65[ 89 ] | CTGs | |||

| SMAs | Internal energy | 0.15[ 91 ] | ≈6[ 51 ]–25.5[ 52 ] | 60[ 52 ] | NBGs |

| 1[ 92 ]–10.078[ 93 ] | 2000[ 61 ] | CBGs | |||

| 40[ 94 ] | 478[ 94 ] | CTGs | |||

| SMPs | Internal energy | 10[ 95 ] | ≈0.4[ 96 ]–≈6[ 59 ] | 2.5[ 59 ] c) | CBGs |

| DEAs | Electric voltage | 0.096[ 97 ] | 2[ 98 ]–10.5[ 99 ] | ≈4000[ 63 ] | CBGs |

| IPMCs | Electric voltage | 0.33[ 65 ] | 6.1[ 100 ]–≈19.3[ 53 ] a) | N/A | NBGs |

| 0.5[ 101 ]–5.08[ 102 ] | 10.3[ 102 ] | CBGs | |||

| LCEs | Internal energy | 0.2[ 103 ] | 0.03[ 66 ] – ≈2.5[ 104 ] | 7.4[ 104 ] | CBGs |

| ≈2[ 105 ] – ≈3[ 67 ] | 50[ 67 ] | CTGs |

The average length of an adult male's hand

The average weight of a medium‐sized orange

The weight of a penny.

3.1. Soft Grippers Based on SPAs

3.1.1. Soft Pneumatic Actuators

In this section, soft grippers based on SPAs are reviewed. While SPAs are one of the oldest actuators, however, due to their numerous advantages, including compliance brought by the compressibility of air, safety (due to the avoidance of the use of hazardous materials, like hydraulic oil that could lead to cleanliness problems), multi‐DOF motion,[ 106 ] a simple structure,[ 107 ] robustness,[ 108 , 109 ] and high forces,[ 110 ] they have been widely used in the field of soft grippers.[ 111 , 112 , 113 , 114 ] The famous McKibben artificial muscle is a representative example of the application of SPAs,[ 115 , 116 ] the performance of which is similar to that of skeletal muscle.[ 117 ] Another example is a high‐force pneumatic actuator reported in 2016, whose blocked forces could reach 77.36 N at 300 kPa.[ 118 ] In addition, pneumatic actuators are driven by compressed air, not high temperatures or high voltage, and are therefore safe for robotic surgery tools and other scenarios that involve human interaction.[ 119 ]

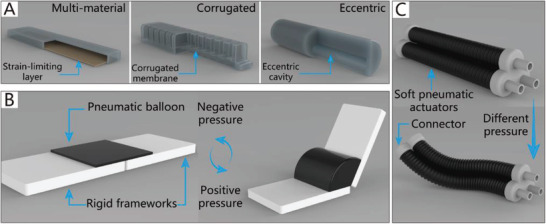

Generally, SPAs can be roughly classified into three types based on their movement methods, the first type of SPAs includes contracting or expanding actuators (for example, Yang et al.[ 120 ] reported bio‐inspired linear actuators powered by a vacuum pump; Hawkes et al.[ 121 ] demonstrated an inverse pneumatic artificial muscle that attains over 300% strain and can achieve nearly linear control). The second type of SPA includes twisting actuators (for example, Kurumaya et al.[ 122 ] released a modular wrist actuator for underwater manipulation; Byrne et al.[ 123 ] demonstrated a twisting actuator via additive manufacturing; Yan et al.[ 124 ] reported a soft torsional actuator with two spiral chambers that can generate torsional motion). The final type of SPA includes bending actuators, which are currently extensively used in the field of soft grippers. The realization of their bending motion is usually based on different types of asymmetry, including multi‐material asymmetry, corrugated membrane asymmetry, and eccentric asymmetry,[ 125 ] as depicted in Figure 3A. Furthermore, Figure 3B,C shows some structural asymmetry designs that could be applied in CBGs and CTGs based on SPAs.

Figure 3.

The schematic diagrams of SPAs. A) The schematic diagram of CBGs driven by SPAs. B) The schematic diagram of NBGs driven by SPAs. C) The schematic diagram of CTGs driven by SPAs.

SPAs can also be roughly categorized into three types based on their driving method, namely membrane actuators, balloon actuators, and origami actuators. Membrane actuators are systems that consist of clamped and flexible films that can expand when pressurized. For instance, Ikeuchi et al.[ 126 ] developed the smallest pressure‐driven micro active catheter with a radius of 200 µm. Balloon actuators are composed of deformable chambers designed with different hollow chambers on the inside that decide the motion direction of actuators.[ 127 ] One example is a gripper driven by elastomeric beams; when negative pressure is applied, a series of useful motions can be produced.[ 128 ] Origami actuators are systems that consist of a flexible skin and internal origami structure, and their shape asymmetry governs the motion of the actuator. For example, an origami‐based vacuum pneumatic actuator was designed by Lee et al.[ 129 ] that could produce large forces (>400 N) with a contraction ratio of >90% of the actual length.

3.1.2. NBGs Based on SPAs

Typically, the pneumatic balloons of NBGs driven by SPAs simultaneously act as joints and actuators. Their working principle is illustrated in Figure 3B. The rigid frameworks are attached between pneumatic balloons as the base of the gripper like their counterpart in nature, phalanxes. The pneumatic balloons can be driven individually or collectively to meet different requirements.

An example is a thin and flexible end effector driven by pneumatic balloon actuators, as illustrated in Figure 4B.[ 130 ] The pneumatic balloon actuator is made by incorporating two layers of film that are stacked together by an adhesive to form an internal cavity. The upper film is made of silicon rubber, and the lower is made of polyimide. Consequently, when pressure is supplied, the pneumatic balloon actuator can swell toward the upper film. Similarly, the pneumatic balloon actuators simultaneously act as both actuators and joints.

Figure 4.

NBGs based on SPAs. A) An end‐effector driven by pneumatic balloon actuators. Reproduced with permission.[ 130 ] Copyright 2001, Elsevier. B) A soft micro‐gripper with four fingers.[ 47 ] Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2009, IEEE. C) A soft gripper with “pouch motors.” Reproduced with permission.[ 46 ] Copyright 2015, Mary Ann Liebert, Inc.

Using a similar theory, Choi et al.[ 47 ] proposed a soft microgripper with four fingers that consist of silicon block bases and pneumatic balloons used as joints to connect the silicon blocks. When the balloon actuator is inflated with compressed air, the attached silicon blocks will make relative out‐of‐plane motions against each other to implement a grasping motion. The microgripper can pick up various‐sized objects by changing the numbers of pneumatic balloons and silicon blocks. The microgripper has only one air inlet; thus, the four fingers can achieve the synchronization of movement. Figure 4C depicts an electric capacitor being captured by the soft microgripper at 240 kPa.

Typically, silicon rubber,[ 130 ] and parylene[ 47 ] are appropriate materials for pneumatic balloon actuators because their tensile strength and extensibility are sufficient to satisfy the movement demands. The manufacturing methods of balloon actuators include casting,[ 131 , 132 , 133 ] 3D printing,[ 134 , 135 , 136 , 137 , 138 ] and a large‐scale preparation method using thermoplastic film. “Pouch motors” are made first by placing two layers of films together and then hot‐pressing them using a heat‐stamping machine. With this approach, two types of drivers can be fabricated, namely the linear pouch motor (which has a maximum stroke of up to 28%) and the angular pouch motor (which has a maximum range of motion of up to 80°), which can generate expanding and contracting motions by a pneumatic control system.[ 46 , 139 ] A soft gripper based on these drivers is shown in Figure 4C.

In consideration of the compact structures of grippers, the size of the soft joints in NBGs is generally small, which has a negative impact on the power of balloon‐type actuators. For example, an extended finger based on pneumatic balloons can only produce a force of about 0.6 N on the fingertip with an air pressure of 40 kPa.[ 46 ] Therefore, NBGs based on SPAs are typically used for the manipulation of small objects. Moreover, the non‐continuum structure of NBGs based on SPAs is unfavorable to the increase of the gripper length, which limits their adaptability for the manipulation of objects of different sizes. However, the non‐continuum structure introduces a competitive advantage for NBGs based on SPAs, the joints of which can be driven independently.

3.1.3. CBGs Based on SPAs

Due to the security and inherent compliance of CBGs based on SPAs, they are commonly used in various industries and daily life. SPAs usually exploit differences in the extent of dilation to bend toward the given side, which can be realized by asymmetric structural designs. The common asymmetric designs and their schematic diagrams are shown in Figure 3A. The specific approaches to build CBGs based on SPAs are thoroughly discussed in this section.

For instance, Deimel and Brock presented a series of dexterous robotic hands based on structural asymmetry,[ 83 , 140 ] the latest of which is driven by the PneuFlex actuator. Its bottom embodies an inelastic fabric that can prohibit the extension of rubber. Consequently, the top side is longer than the bottom side when pressurized. Thus, the actuator bends toward the bottom side. The dexterous robotic hand can be adapted to many applications, such as the manipulation of chopsticks and pens, as illustrated in Figure 5A. It should be noted that, although its shape is similar to that of human hands, its working principle differs significantly.

Figure 5.

CBGs based on SPAs. A) A dexterous robotic hand driven by a PneuFlex actuator. Reproduced with permission.[ 140 ] Copyright 2016, SAGE Publications. B) A bio‐inspired 3D printable soft vacuum gripper. Reproduced with permission.[ 141 ] Copyright 2018, Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. C) A flexible pressure‐driven gripper. Reproduced with permission.[ 54 ] Copyright 1990, Cambridge University Press. D) A starfish‐like gripper. Reproduced with permission.[ 108 ] Copyright 2011, John Wiley and Sons. E) A pressure‐driven gripper with bilaterally curved fingers. Reproduced with permission.[ 81 ] Copyright 2017, Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. F) A gripper with asymmetrical beam structure. Reproduced with permission.[ 142 ] Copyright 2018, National Academy of Sciences – Biactive Work. G) An origami‐inspired gripper. Reproduced with permission.[ 143 ] Copyright 2019, IEEE. H) A modular pressure‐driven actuator. Reproduced with permission.[ 144 ] Copyright 2018, Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. I) A soft gripper fabricated by sculpting. Reproduced with permission.[ 82 ] Copyright 2016, Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. J) A soft gripper used to grasp aquatic mollusk. Reproduced with permission.[ 55 ] Copyright 2019, The American Association for the Advancement of Science. K) A hydraulic gripper based on transparent hydrogel actuators. Reproduced with permission.[ 145 ] Copyright 2017, Springer Nature. L) A self‐healing soft pneumatic gripper. Reproduced with permission.[ 146 ] Copyright 2017, The American Association for the Advancement of Science.

The imitation of the structural asymmetry of the natural world has also been explored. For example, the sporangium of the fern can force its radial walls to bend via negative pressure generated in the cells.[ 147 ] Using a similar driving principle, a bio‐inspired 3D printable soft vacuum actuator has been reported by Charbel et al.[ 141 ] Its structural design was inspired by the sporangium of fern trees. When air is exhausted by the vacuum pump, the bio‐inspired actuator shrinks in volume and bends toward the given side. Some of the advantages of this actuator include its high actuation speed (5.54 Hz) and significant output forces (≈16 N). Based on this type of actuator, a gripper with three fingers that can pick up a cup and a kiwi fruit has been developed, as shown in Figure 5B.

The grippers described previously can only bend to one side when pressurized, and their reset motion (from the bending state to the extension state) is realized by their elasticity. Thus, the speed of the reset motion is uncontrollable. To realize controllable bilateral bending, a design has been proposed by Tedford; each motion module contains two independently‐driven chambers, and by exploiting the pressure difference between the two chambers, bilateral bending motion can be realized.[ 54 ] Based on this novel design, a flexible pressure‐driven gripper that has two fingers to handle delicate fruit for export is presented in Figure 5C. Similarly, Figure 5D shows a starfish‐like gripper that has two‐layered actuators embedded in pneumatic networks of channels that can drive the actuators to bend or extend under different pressures.[ 108 ] Via the use of two‐layered pouch motor actuators, Moghadam et al.[ 81 ] reported a thin SPA that is hot‐pressed with four layers of thermoplastic polyurethane. As illustrated in Figure 5E(a), the first and second layers form a pouch motor, and the third and fourth layers form another pouch motor. Pressure‐driven grippers can generate movement when the two pouch motors are at different pressures. As shown in Figure 5E(b), different pick‐and‐place tasks can be achieved with bilaterally curved fingers.

Structural asymmetry in actuators can also exist in the form of an origami structure. Origami‐inspired SPAs are usually driven by a vacuum pump, which can produce large contractile strokes with relatively compact shapes.[ 148 ] Moreover, the possibility of bursting and bulging, which can occur in conventional pneumatic actuators, is eliminated.[ 141 ] The inner soft origami structure can improve the drive efficiency[ 149 ] and provide specific bending resilience based on different folding patterns.[ 150 ] Li et al.[ 142 ] presented origami‐inspired artificial muscles, the performance of which is similar to or better than that of natural muscle. The peak power density of these muscles can reach 2 kW per kg when they achieve a bending motion. As shown in Figure 5F, an asymmetric beam structure was designed, which tends to the given side when the actuator is driven by a vacuum pump. Later, the authors reported another origami‐inspired vacuum‐driven gripper with a hollow hemispherical body shape.[ 143 ] The gripper consists of three components, namely the origami‐based internal skeletal structure, the skin that envelopes the skeletal structure, and the connector of the gripper and manipulator. As illustrated in Figure 5G, the gripper can grasp a large variety of different‐shaped objects with sufficient gripping force.

Researchers have also been continually interested in modular pressure‐driven actuators,[ 151 , 152 ] which could overcome the existing problem of the continuum structure being unable to implement independent movement in specific parts of the actuators. One example is a modular pneumatic bending actuator fabricated by Natividad et al.,[ 144 ] as shown in Figure 5H, which is composed of many removable inflatable gas cells and a flexible spine, and can act as a finger of a pressure‐driven gripper. Due to the different distributions of the pressurized flow to the modules (gas cells), the actuator can achieve different geometric variations and functions. Furthermore, the reconfigurability of the actuator allows it to rapidly be suited for different application scenarios.

From the preceding examples, it is evident that the typical working mode of CBGs based on SPAs is being driven by gas cells with structural asymmetry. The fabrication methods of gas cells are usually intricate, and include casting, 3D printing, and adhesion. To simplify the fabrication process, Argiolas et al.[ 82 ] proposed a fast and simple methodology, namely the foam porous structure, to replace traditional gas cells. The foam porous structure is convenient for 3D printing and sculpting, and is therefore friendly for amateurs. Regarding the production process of foam porous structure actuators, the lost‐salt method[ 153 ] is first used to fabricate foams by mixing silicone prepolymer and common salt. Then, the foams and strain‐limiting material are wrapped up together with an external seal. As shown in Figure 5I, a soft gripper fabricated by sculpting is able to grasp an apple.

The materials adopted in CBGs based on SPAs include PDMS (the elongation at break of which is 150%), Ecoflex 00–30 (the elongation at break of which is 900%),[ 108 ] thermoplastic polyurethane (the elongation at break of which is 800%),[ 141 ] and Ecoflex 00–10 (the elongation at break of which is 800%).[ 82 ] These materials are all compliant, soft, and inherently safe, and have high elongation. They are also used in some particular fields in which the softness (elastic modulus) and self‐healing ability of materials must be considered.

The collection of fragile objects, like aquatic mollusk samples, is another application of CBGs based on SPAs.[ 154 , 155 ] Sinatra et al.[ 55 ] fabricated an ultra‐gentle soft robotic gripper incorporated in a lower durometer silicone matrix (Shore 20A), which is better served to capture delicate specimens of gelatinous aquatic life. This soft grasping robot is composed of four or six slender fingers, each of which is an independent actuator that contains two layers. One of the layers is so elastic and tight that it cannot extend, while the other is flexible; as a result, the flexible layer will tend toward the tough layer under pressure. The gripper is exceptionally light (123g) and can therefore be driven using low pressure, which helps the finger to protect delicate specimens. As shown in Figure 5J, the handheld grasping device can gently grasp a moon jellyfish and a blue blubber jellyfish. To the same end, Yuk et al.[ 145 ] reported a hydraulic gripper based on transparent hydrogel actuators that can be camouflaged in water and maintain their robustness and functionality over multiple cycles of actuation. The transparent hydrogel gripper can catch, lift, and release a goldfish, as shown in Figure 5K. The agile actuation and optical transparency of the gripper ensure the rate of success of capture, and due to the low stiffness of the gripper, the collected biological samples are not harmed.

Appropriate CBGs based on SPAs can protect delicate objects from damage; however, they are usually made from soft materials and are highly susceptible to damage. To overcome this limitation, Terryn et al.[ 146 ] developed a self‐healing soft pneumatic gripper made of Diels–Alder polymers, as shown in Figure 5L. Via a thermo‐reversible Diels–Alder reaction,[ 156 ] visible damages caused by sharp objects or the overloading of the gripper are sealed, and the initial mechanical properties are recovered. CBGs based on SPAs can also be applied in the field of soft exoskeletons. For example, Heung et al.[ 157 ] developed an exoskeleton that provides convenience to the accomplishment of grasping by using a soft‐elastic composite actuator.

Furthermore, the application of SPAs in the industrial field is already quite mature, which means that they have better stability and lower fault rates. These advantages have resulted in SPA‐based CBGs being the most widely used type of soft gripper. Moreover, compared with NBGs based on SPAs, the grasping capability of CBGs based on SPAs is increased significantly, as shown in Table 2; one such gripper can lift a water bottle with a weight of 546 g.[ 83 ] However, most CBGs based on SPAs cannot bend in specified locations like their counterpart in nature, Drosera. To tackle this problem, modular SPAs are a solution that could expand the application fields of CBGs based on SPAs.

3.1.4. CTGs Based on SPAs

With inspiration from the typical muscular hydrostat structures of elephant trunks and octopus tentacles, many CTGs based on SPAs have been designed.[ 158 , 159 , 160 , 161 , 162 , 163 , 164 ] They are usually driven by actuators of pressure‐driven antagonistic actuation, which consist of two or more antagonistic units; the schematic diagram is shown in Figure 3C. The difference in the gas pressure in antagonistic units forces the actuators to implement specific movements, such as bending movements[ 165 , 166 ] and rotational movements.[ 167 ]

As early as 1991, a flexible micro‐actuator was designed by Suzumori et al.,[ 168 , 169 ] which has three internal chambers. The micro‐actuator is reinforced with inextensible fiber in the circular direction, and it therefore easily deforms in the axial direction. By controlling the internal pressure of the three chambers, the actuator can implement pitching, yawing, and stretching movements. As presented in Figure 6A, a flexible soft gripper has been designed by using three such micro actuators, which can flexibly manipulate a beaker filled with liquid. Using similar actuators, Bartow et al.[ 84 ] presented a continuum manipulator driven by artificial muscles connected by zip ties. By controlling the internal pressure of the artificial muscles, the manipulator can conduct different active motions. Besides, Elsayed et al.[ 170 ] determined the optimal design of a pneumatically actuating silicone module via finite element analysis. Various pneumatic chamber designs for the pneumatic actuator were investigated, including chambers with a circular cross‐section, semicircular cross‐section, circular sector cross‐section, and ring sector cross‐section. Besides, the interior material of the chambers can also be optimally designed, just like a vacuum‐powered SPA, which is based on three antagonistic chambers consisting of an off‐the‐shelf foam core and brushed‐on layers of silicone rubber. The foam core chambers are more robust to external disturbance than traditional air chambers, and they can be easily fabricated without a mold or 3D printer.[ 171 ]

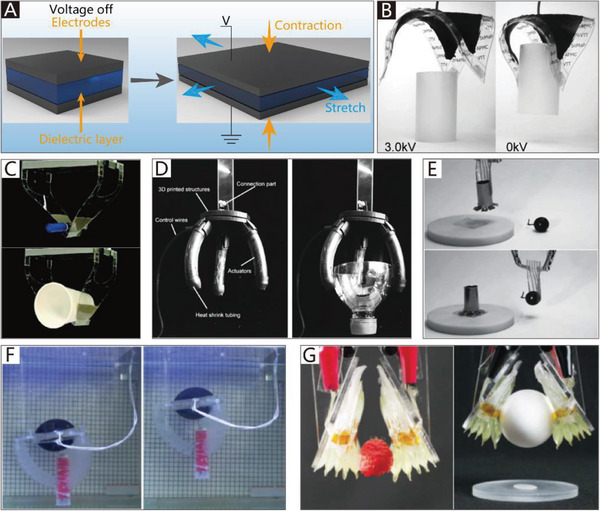

Figure 6.

CTGs based on SPAs. A) A 4‐finger gripper. Reproduced with permission.[ 169 ] Copyright 1992, IEEE. B) A gripper with multiple bending modes. Reproduced with permission.[ 70 ] Copyright 2012, John Wiley and Sons. C) OctArm. Reproduced with permission.[ 85 ] Copyright 2006, SPIE. D) A wearable mobile manipulation. Reproduced with permission.[ 71 ] Copyright 2019, Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. E) A helical inflatable gripper. Reproduced with permission.[ 172 ] Copyright 2015, IEEE. F) A helical soft pressure‐driven actuator. Reproduced with permission.[ 72 ] Copyright 2019, Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. G) A high‐load soft gripper. Reproduced with permission.[ 79 ] Copyright 2019, Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. H) A soft micro‐gripper. Reproduced with permission.[ 73 ] Copyright 2015, Springer Nature.

Based on the antagonistic actuation principle, the motion chambers of a typical biomimetic muscle hydrostat gripper usually influence each other, which is not conducive to the operability of soft grippers. More complex motion can be achieved by dividing the entire gripper into several parts to operate them separately. One representative example is a soft manipulator for minimally invasive surgery. Like octopus tentacles, the soft manipulator is composed of soft materials and driven by two identical modules with multi‐directional bending and stiffening capabilities. A single module can conduct active motion while the other module stiffens. The independent motion of the modules can enhance the manipulability of the soft manipulator during surgery.[ 173 ] Also, based on the modular design idea, Martinez et al.[ 70 ] developed a biomimetic gripper with 3D mobility that has three different pressure‐driven sections, each of which has three independent microchannels for antagonistic actuation, as shown in Figure 6B(a). The range of motion and the capability for complex manipulation increase with the number of pressure modules. As shown in Figure 6B(b), a soft gripper with multiple bending modes can adopt complex shapes and manipulate delicate objects. Another example of modular manipulators is a soft robot called OctArm that consists of three sections. Each section has individual air muscle extensors with control channels that provide two‐axis bending and extension. The soft robot manipulator can provide 890 and 250 N of vertical and transverse load, respectively, using 8.27 bar of air pressure. As shown in Figure 6C, the modular design allows the manipulator to easily meet various complex requirements.[ 85 , 174 ] Similarly, Nguyen et al.[ 71 ] developed a fluid‐driven, wearable mobile manipulator for daily living tasks. The wearable manipulator equips the user with an additional limb that is safe and compliant, enabling the user to achieve complex 3D motion in space. It consists of three modular tapered segments, each of which is made of three chambers. By controlling the internal pressure of the chambers, the manipulation equipment can implement specific movements. The end‐effector functional module is also reconfigurable according to different grasping tasks, as presented in Figure 6D.

Even without a muscular hydrostat, some creatures (like boa constrictors and vines) can achieve grasping movements similar to those of octopus tentacles and elephant trunks. Many pressure‐driven manipulators inspired by the winding behaviors of these creatures have been designed.[ 175 , 176 , 177 ] One example is a tendril‐like gripper based on an inflatable origami‐based actuator, which is constructed by connecting a soft chamber to an origami rotational joint. The advantages of the origami structure are that the soft chamber is protected from punctures, and stability is provided for the whole gripper.[ 178 ] Figure 6E depicts an extremely lightweight helical inflatable gripper that consists of an inflatable soft actuator with pleated structures. While this end effector weighs only about 40 g, it has a gripping force of up to 15 N. The bag structure of the gripper consists of two upper pleated plastic‐films and one lower plastic film. Due to its asymmetry, when the bag structure is pressurized, the gripper can generate a helical motion.[ 172 ] Based on the asymmetry of the structure, Hu and Alici developed a bio‐inspired helical soft pressure‐driven actuator that can simultaneously generate bending and twisting motions (Figure 6F). The pressure‐driven actuator is composed of a passive lower layer and an upper active layer with the same helix angle arranged in a row. When the actuator is under pressure, the expansion of the upper active layer is greater than that of the lower layer. The asymmetry of the upper active layer and the lower passive layer forces the gripper to move vertically and horizontally.[ 72 ] Inspired by the winding behaviors of animals and plants, Li et al.[ 79 ] reported four types of high‐load soft grippers, namely the spiral interleaving bionic gripper, parallel interleaving bionic gripper, spiral winding bionic gripper, and parallel winding bionic gripper, all of which are driven by pneumatic artificial muscles. A simulation and experimental analysis revealed that the parallel winding bionic gripper could achieve the highest gripping force under the same air pressure. The high‐load soft gripper can lift heavy objects that weigh up to 20 kg. As shown in Figure 6G, in addition to their higher load capacity, they can grip multiple kinds of objects with different shapes and stiffnesses. In addition, Paek et al.[ 73 ] proposed a soft microgripper with spiral bending capability, which is composed of a PDMS microtube (with an inner diameter of 100–125 µm) as the platform structure and a hump as an additional structure to help the microgripper produce a tentacle‐like spiraling motion. The grasping force of the microgripper is about 0.78 mN, and it can wind around and hold fragile micro‐objects with a final spiral radius of ≈200 µm. A Mallotus villosus egg can be comfortably held by the microgripper, as shown in Figure 6H.

Based on the preceding analysis, the SPAs applied in CTGs can be divided into two categories. The first includes antagonistic actuators that consist of two or more (usually three) antagonistic units. After years of continuous improvement, modular design has been introduced to antagonistic actuators; the entire gripper is divided into several parts and meets the demand of individual operation. The manipulability and flexibility of these actuators have been improved at the expense of the complexity of control. The second type of SPA can generate twisting motions by using its structural asymmetry. While these actuators usually have compact and simple structures, their movement forms are relatively singular, which restricts both their controllability and functionality. Future studies on the application of SPAs in CTGs could focus on ensuring the flexibility and manipulability of the actuators without sacrificing their compact and simple structure.

The materials adopted in CTGs based on SPAs include Ecoflex 00–30 (the elongation at break of which is 900%),[ 70 ] Dragon Skin 30 (the elongation at break of which is 364 %),[ 71 ] FilaFlex (the elongation rate of which reaches 400%),[ 72 ] and PDMS (the elongation at break of which is 150%).[ 73 ] Materials with high elongation are a necessary qualification for CTGs based on SPAs, which must implement grasping tasks via the large deformation of soft actuators. Moreover, some measures have been taken to sufficiently enhance deformation (which usually refers to axial deformation). For example, plastic rings are inserted along the length of the actuator to restrict radial expansion.[ 71 ]

The continuity of CTGs is beneficial for the arrangement of powerful SPAs, which can increase the load capacity of grippers. As shown in Table 2, their length is increased, and one SPA is as long as 148 cm.[ 84 ] While the increase of the gripper length makes the workspace larger, it also enhances the adaptability of the CTG to objects with different scales. However, due to the continuity of the actuators, the motion of any part of a CTG based on SPAs is dependent; thus, the separate control of a portion of the gripper is difficult.

3.2. Soft Grippers Based on Cable‐Driven Actuators

3.2.1. Cable‐Driven Actuators

Due to the compressibility of gas, the pneumatic system is considered to be nonlinear.[ 179 ] Therefore, it is challenging for pneumatic actuators to achieve accurate control.[ 180 , 181 ] In contrast, it is much easier for inextensible cables to achieve the precise control of position and force, which allows them to meet high requirements, such as those of surgical robots.[ 182 ] Moreover, end effectors, such as cable‐driven hands, can be installed far from the power source by cable transmissions,[ 183 ] which lowers the moment of inertia of the end effector.[ 184 ] Additionally, flexible and compliant cables have a very high tensile strength along their longitudinal axis; thus, they can easily fit into the manipulators.[ 1 ] Based on these advantages, many traditional cable‐driven hands consisting of rigid links and joints have been developed.[ 185 , 186 , 187 , 188 , 189 , 190 , 191 ] Recently, cable actuators based on soft materials have been widely developed in the field of light weight soft robotic hands.[ 7 , 192 ] Due to the similarity between cable actuators and human hands regarding their driving form, cable actuators are suitable for use in the field of bionic soft hands.

However, one of the limitations of cable‐driven actuators is their elasticity, which usually adversely influences their static and dynamic performance. Additionally, routing systems that guide the cables from the power source to the end effector will add additional friction to the system.[ 183 ]

3.2.2. NBGs Based on Cable‐Driven Actuators

Unlike traditional rigid cable‐driven grippers, which include fingers consisting of many rigid joints between stiff segments, NBGs based on cable‐driven actuators have no rigid joints, which are instead replaced by hinges made of elastic materials. The elastic hinges introduce compliance to the system, and are also used as actuators to return the actuated fingers previously driven by cables.[ 193 , 194 , 195 ] The detailed schematic diagram is shown in Figure 7A. Based on this method, Stuart et al.[ 48 ] reported an adaptive cable‐driven manipulation design that utilizes elastic finger joints and a spring transmission to implement multiple types of motions, including various pinches and grasps, like human hands. The gripper is actuated by cables, which pass over joints molded by urethane flexures and return the actuated fingers by preloaded stainless‐steel springs. The grasping ability of the gripper, which can grasp various irregularly‐shaped objects, is presented in Figure 7B. Furthermore, a dexterous tendon‐driven hand that possesses five anthropomorphic, adaptive fingers has been reported. The fingers can smoothly accomplish adduction/abduction and flexion/extension.[ 195 ] As shown in Figure 7C, the bionic hand can perform various grasping tasks in daily life. Similarly, Tavakoli et al.[ 196 ] reported a low‐cost, adaptive, and low‐weight (only 280 g) anthropomorphic hand that is integrated with a twisted string actuation system, which includes motors and twisted string that can convert the rotational motion of actuators into linear motion. Furthermore, the natural compliance of the system ensures that the hand can operate safely around humans.

Figure 7.

NBGs based on cable‐driven actuators. A) The driving type of the NBGs based on cable‐driven actuators. B) A cable‐driven manipulation with elastic finger joints. Reproduced with permission.[ 48 ] Copyright 2017, SAGE Publications. C) A dexterous tendon‐driven hand. Reproduced with permission.[ 195 ] Copyright 2019. D) A gripper is driven by a single cable tendon. Reproduced with permission.[ 49 ] Copyright 2015, Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. E) An Omni‐purpose soft gripper incorporated with soft fingers and a suction cup. Reproduced with permission.[ 50 ] Copyright 2019, IEEE. F) A biomimetic cable‐driven hand. Reproduced with permission.[ 197 ] Copyright 2016, IEEE. G) An origami‐inspired soft gripper. Reproduced with permission.[ 86 ] Copyright 2019, IEEE.

Each finger of a soft gripper driven by cable‐driven actuators usually has an independent actuator to implement coordinated manipulation. However, the control system will become complicated when each finger is separately driven. Thus, Manti et al.[ 49 ] put forward a more straightforward control method in which only a single cable tendon is used to drive the whole gripper, which has the advantages of simple control and adaptive grasping. The gripper has three fingers driven by a single cable inside the tubes. As shown in Figure 7D, when external resistance is applied to one finger, the other two fingers can still achieve the complete closure of the object to realize a full grasp. Hence, the control scheme guarantees the ability to grasp objects with different shapes. When the gripper is ready for the next grasping task, the cable will release, and the fingers will spring back.

A combination of tendon‐driven actuators and other auxiliary structures could achieve better‐grasping performance. One representative example (Figure 7E) is an omni‐purpose soft gripper that incorporates soft fingers and a suction cup, which helps to grasp a wide variety of objects with smooth surfaces. The three tendon‐driven soft fingers of the gripper are driven by linear soft vacuum actuators manufactured using low‐cost 3D printing. The soft gripper can be mounted on a 6‐DOF robotic manipulator, which is responsible for controlling the position of the soft gripper in space.[ 50 ]

The working pattern of NBGs based on cable‐driven actuators is quite similar to the working pattern of human hands, which have a driving system consisting of skeletal muscles, tendons, and fingers. The fingers can achieve flexing and extension, as well as abduct and adduct motions under the drive of the skeletal muscles of the palm and forearm via the delivery of tendons connected with the phalanxes. Therefore, researchers have investigated human hands with the intention of replicating their functions by robots performing tasks. Xu and Todorov developed a biomimetic cable‐driven hand with a highly biomimetic design, including the morphology of bones, tendons, and joints as the connection between two adjacent bones. As shown in Figure 7F, this hand can perform the in‐hand manipulation of a whiteboard eraser. With the aim of preserving the structural features of bones to the greatest extent, the manufacturing method of 3D printing is adopted. The adjacent 3D‐printed bones are connected by crocheted ligaments and laser‐cut joint soft tissues, which are used to mimic human soft tissues to provide similar functions as the finger joint. Ten dynamic servos are also used to imitate important large skeletal muscles, and high‐strength strings are used to imitate tendons.[ 197 ]

In addition to the grasping task, bionic hands can be used for the biomechanical study of human hands. To better understand human hands, another highly biomimetic tendon‐driven hand was designed by Çulha and Iida. The passive compliance of the cable‐driven hand is achieved by covering two types of elastic ligaments, including capsule ligaments, which are a layer to keep the joints in place and that slide over each other, and collateral ligaments, which surround the sides of the capsule ligaments to guide the motion of the joints. Moreover, the structural parameters of the right‐hand bones provided by 3B Scientific GmbH are adopted for anatomic accuracy. Finally, the cables are used to drive the bones of the fingers to surround the bone tips.[ 198 ]

In addition to the human hand‐type frame, the origami structure is another good option for the frame of cable‐driven grippers. These structures have rigid frames and relatively soft joints (the creases used for folding in the origami structure). Kan et al.[ 86 ] designed an origami‐inspired soft gripper that can generate grasping movements depending on the geometric constraints of the origami spring structures. The soft gripper consists of two origami fingers and a tendon‐based actuator. The gripper is powered by the tendon‐based actuator and can be flexibly switched between a flat‐sheet mode and a gripping mode. As illustrated in Figure 7G, a prototype of a soft gripper based on the origami pattern was fabricated using elastic material via 3D printing technology, and can hold various common objects.

Different from NBGs based on SPAs, the joints of which also are actuators, NBGs based on cable‐driven actuators have passive‐compliance joints, and their elastic constraints are provided by bionic ligaments. In addition, power is provided independently by cable‐driven actuators, which can be installed in a location other than in the gripper. Thus, the increased volume and weight introduced by the high‐power actuators will not affect the operating efficiency of the manipulators. Moreover, due to the existence of rigid structures, NBGs based on cable‐driven actuators can achieve high‐stability performance; as shown in Table 2, they have the advantages of a high load capacity, high stability, and reliability.

NBGs based on cable‐driven actuators have been gradually matured in recent years. They are made with elastic materials (such as urethane,[ 48 ] silicone,[ 49 ] and black nitrile rubber[ 198 ]) and have hinges and cable tendons (made of materials such as nylon cable [ 49 ] and fishing line[ 50 ]) like human hands, and can smoothly accomplish various pinching and grasping tasks. Due to the material attributes of cable tendons, the deformation of which is extremely low, the response time of these grippers can often be ignored. However, a potential limitation of NBGs based on cable‐driven actuators is their load capacity. Compared with human hands, almost all NBGs can only be used under low‐load conditions, even though their driving mode and structural features are similar to those of human hands. Besides, the use of bionic NBGs based on cable‐driven actuators to study the biomechanical properties of human hands will be a potential research issue in the future.

3.2.3. CBGs Based on Cable‐Driven Actuators

A continuum soft gripper can be considered as a bending manipulator consisting of elastic elements with ideally infinite DOFs.[ 199 ] The working pattern of cable‐driven actuators is quite suitable for CBGs. Therefore, cable‐driven actuators are also widely applied in the field of CBGs. One example is a pre‐charged pneumatic soft gripper that includes a combination of SPAs and tendon‐driven actuators. The gripper is precisely controlled by the tendons and powered by pre‐charged air. Each finger of the gripper bends to different degrees when the tendons are pulled or released. As depicted in Figure 8A(a), the soft finger has three control parameters, namely the tendon pulling/releasing displacement, the tendon pulling force, and the tendon pulling/releasing speed. One parameter can be selected at a time for control. The soft gripper prototype is shown in Figure 8A(b), and is composed of a gripper base and three fingers that can grasp various subjects, such as a bottle of water, a piece of tofu, and a roll of tape.[ 56 ] Additionally, Zhu et al.[ 200 ] proposed a novel spherical self‐adaptive gripper that has a continuous elastic membrane made of a deformable material. The elastic membrane, which is connected to one end of the cable, can envelop and pick up an object with the pulling‐up motion of the cable, and can adapt to objects with various shapes and sizes.

Figure 8.

CBGs, CTGs based on cable‐driven actuators. A) A precharged pneumatic soft gripper. Reproduced with permission.[ 56 ] Copyright 2018, Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. B) A soft wearable robot for hands. Reproduced with permission.[ 57 ] Copyright 2019, Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. C) The schematic diagram of CTGs based on cable‐driven actuators. The dotted lines show the hidden arrangement of the cables and the circle on the right of each picture represents the cross section of the cylinder in which the filled dots represent pulled cables, and empty dots represent released cables. (Modified and redrawn.) Reproduced with permission.[ 90 ] Copyright 2011, Elsevier. D) A cable‐driven biomimetic gripper. Reproduced with permission.[ 74 ] Copyright 2012, IOP Publishing. E) A soft arm inspired by the octopus. Reproduced with permission.[ 75 ] Copyright 2012, Taylor & Francis. F) A variable compliance, soft gripper. Reproduced with permission.[ 89 ] Copyright 2014, Springer Nature.

Another application of cable‐driven actuators is their use in soft wearable robots, which help people pinch and grasp. Human hands could be considered as cable‐driven grippers when people equip the wearable robot. Kang et al. developed a series of soft wearable robots for the hands, which are constructed of polymer materials and driven by cable‐driven actuators. The latest soft wearable robot consists of a glove, tendon sheaths, and an actuation system (Figure 8B), and can restore the ability of the hands to pinch and grasp various objects in daily life. Due to the reduced number of components, the robustness of the glove is improved and its weight is decreased, which is critical to the wearing comfort.[ 57 , 88 ] The working principle of cable‐driven actuators is the most similar to that of human hands, which will exceptionally meet the needs of soft wearable robots to help spinal cord injury patients accomplish daily tasks.

Like SPAs, cable‐driven actuators have been widely applied in industry. However, they cannot change their stiffness by themselves, as can SPAs. Therefore, they are usually combined with other stiffness‐controllable materials when applied in soft grippers. In the future, cable‐driven actuators will be widely applied in the field of soft wearable equipment due to their excellent characteristics, such as those of human tendons. Due to the particularity of their applications, the materials of soft wearable equipment are usually required to have no toxicity and allow for sanitization. Silicone (KE‐1300T) is a common choice, as it has ability to adapt to different sizes and can be easily cleaned compared with fabric.[ 57 ] Moreover, to guarantee the mechanical characteristics of the body, sweat volatility and antibacterial activity should be taken into account for wearable equipment in future work.

3.2.4. CTGs Based on Cable‐Driven Actuators

Cable‐driven actuators are characterized by the ability to precisely control their position and force, a high tensile strength in the longitudinal axis direction, and inherent compliance, which make them suitable for the complex motions of CTGs. Many CTGs have been successfully designed on the basis of cable‐driven actuators, the ideally infinite DOFs and hyper‐redundancy of which improve the maneuverability of grippers.[ 201 , 202 , 203 ] The basic working principle of CTGs based on cable‐driven actuators is shown in Figure 8C. The mock‐up, as shown in Figure 8C(a), includes a silicone cylinder and 4 longitudinal cables embedded in the silicone material. When all the cables are pulled, the mock‐up shortens, and the diameter increases (Figure 8C(b)). As shown in Figure 8C(c,d), the mock‐up is driven by pulling a longitudinal cable; in particular, the stiffening of a part of the mock‐up (represented by the rigid tube shown in Figure 8C(d)) can avoid the shortening, elongation, or bending actions of the corresponding part.[ 90 ]

Recently, researchers have drawn inspiration from biology to study CTGs with excellent properties. For example, Laschi et al. developed a series of biomimetic CTGs based on octopus tentacles, which are entirely non‐rigid structures with many DOFs and high flexibility. One of these CTGs is a cable‐driven continuum soft manipulator based on a 3D geometrically‐exact steady‐state model, as illustrated in Figure 8D. The soft manipulator is composed of a single conical piece of silicone driven by low‐stretch cables, which are dispersedly fixed inside the silicone body and coated with a polymer sheath to avoid friction resistance generated between the cables and the silicone body of the manipulator. The general geometrically‐exact steady‐state model of the soft manipulator is so accurate that the model can be easily used to define essential characteristics of motion.[ 74 ] A supervised learning method and model‐based method have been proposed to solve the inverse statics of the cable‐driven continuum manipulator, and can improve the accuracy and rapidity of the cable‐driven soft manipulator.[ 204 ]