Abstract

Tyrosine phosphorylation of secretion machinery proteins is a crucial regulatory mechanism for exocytosis. However, the participation of protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs) in different exocytosis stages has not been defined. Here we demonstrate that PTP‐MEG2 controls multiple steps of catecholamine secretion. Biochemical and crystallographic analyses reveal key residues that govern the interaction between PTP‐MEG2 and its substrate, a peptide containing the phosphorylated NSF‐pY83 site, specify PTP‐MEG2 substrate selectivity, and modulate the fusion of catecholamine‐containing vesicles. Unexpectedly, delineation of PTP‐MEG2 mutants along with the NSF binding interface reveals that PTP‐MEG2 controls the fusion pore opening through NSF independent mechanisms. Utilizing bioinformatics search and biochemical and electrochemical screening approaches, we uncover that PTP‐MEG2 regulates the opening and extension of the fusion pore by dephosphorylating the DYNAMIN2‐pY125 and MUNC18‐1‐pY145 sites. Further structural and biochemical analyses confirmed the interaction of PTP‐MEG2 with MUNC18‐1‐pY145 or DYNAMIN2‐pY125 through a distinct structural basis compared with that of the NSF‐pY83 site. Our studies thus provide mechanistic insights in complex exocytosis processes.

Keywords: catecholamine, exocytosis, PTP‐MEG2, structure, tyrosine phosphorylation

Subject Categories: Membrane & Intracellular Transport; Post-translational Modifications, Proteolysis & Proteomics; Structural Biology

The tyrosine phosphatase PTP‐MEG2 regulates multiple steps of exocytosis through two distinct substrates: it de‐phosphorylates (1) NSF‐pY83 to modulate quantal size; (2) DYNAMIN2‐pY125 and MUNC18‐1 pY145 to regulate fusion pore opening.

Introduction

Secretion via vesicle exocytosis is a fundamental biological event involved in almost all physiological processes (Wu et al, 2014; Neher & Brose, 2018; Dittman & Ryan, 2019). The contents of secreted vesicles include neuronal transmitters, immune factors, and other hormones (Alvarez de Toledo et al, 1993; Sudhof, 2013; Magadmi et al, 2019). There are three major exocytosis pathways in secretory cells, namely, full‐collapse fusion, kiss‐and‐run, and compound exocytosis, which possess different secretion rates and release amount (Sudhof, 2004). It has previously been reported that the phosphorylation of critical proteins at serine/threonine or tyrosine residues participates in stimulus–secretion coupling in certain important exocytosis processes, for example, the secretion of insulin from pancreatic β cells and the secretion of catecholamine from the adrenal medulla (Seino et al, 2009; Ortsater et al, 2014; Laidlaw et al, 2017). However, the exact roles of protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs) in the regulation of key hormone secretion procedures are not fully understood.

The 68‐kDa PTP‐MEG2, encoded by ptpn9, is a non‐receptor classical PTP encompassing a unique N‐terminal domain with homology to the human CRAL/TRIO domain and yeast Sec14p (Gu et al, 1992; Alonso et al, 2004; Huynh et al, 2004; Cho et al, 2006; Zhang et al, 2012; Zhang et al, 2016). The N‐terminal Sec14p homology domain of PTP‐MEG2 recognizes specific phospholipids in the membrane structure and is responsible for its specific subcellular location. In secretory immune cells, PTP‐MEG2 has been suggested to regulate vesicle fusion via direct dephosphorylation of the pY83 site of N‐ethylmaleimide‐sensitive fusion protein (NSF; Huynh et al, 2004). However, many key issues regarding PTP‐MEG2‐regulated cell secretion remain controversial or even unexplored. For example, it is uncertain whether PTP‐MEG2 regulates vesicle exocytosis only within immune cells (Zhang et al, 2016) and only plays insignificant roles in other hormone secretion processes. It remains elusive whether PTP‐MEG2 regulates vesicle trafficking pathways other than the NSF‐mediated vesicle fusion.

Functional characterization of PTP‐MEG2 in vivo normally requires a knockout model; however, PTP‐MEG2‐deficient mice show neural tube and vascular defects, and the lack of PTP‐MEG2 is embryonic lethal (Wang et al, 2005). Alternatively, a specific small‐molecule inhibitor of PTP‐MEG2 has fast response with no compensatory effects, enabling it to serve as a powerful tool to investigate PTP‐MEG2 functions (Zhang et al, 2012; Yu & Zhang, 2018). Recently, we have developed a potent and selective PTP‐MEG2 inhibitor, Compound 7, that has a Ki of 34 nM and shows at least 10‐fold selectivity for PTP‐MEG2 over more than 20 other PTPs (Zhang et al, 2012). The application of this selective PTP‐MEG2 inhibitor in combination with electrochemical approaches enabled us to reveal that PTP‐MEG2 regulates multiple steps of catecholamine secretion from the adrenal medulla by controlling the vesicle size, the release probabilities of individual vesicles, and the initial opening of the fusion pore during exocytosis. Further crystallographic studies of the PTP‐MEG2 protein in complex with the pY83‐NSF fragment and enzymological kinetic studies captured the transient interaction between PTP‐MEG2 and NSF and provided the structural basis for PTP‐MEG2 substrate specificity. Interestingly, by delineating the substrate specificity of deficient PTP‐MEG2 mutants in the study of catecholamine secretion from primary chromaffin cells, our results suggested that PTP‐MEG2 regulates the initial opening of the fusion pore during exocytosis by regulating substrates other than the known NSF through a distinct structural basis. We therefore took advantage of this key knowledge and utilized bioinformatics analysis, GST pull‐down screening, and enzymological and electrochemical techniques to identify the potential key PTP‐MEG2 substrates involved in fusion pore opening. These experiments led to the identification of several new PTP‐MEG2 substrates in the adrenal medulla, of which DYNAMIN2‐pY125 and Mammalian homolog of Unc‐18 (MUNC18)‐1‐pY145 are the crucial dephosphorylation sites of PTP‐MEG2 in the regulation of initial pore opening and expansion. Further crystallographic analyses and functional assays with MUNC18‐1 Y145 and DYNAMIN2‐pY125 revealed the mechanism underlying the recognition of MUNC18‐1 and DYNAMIN2 by PTP‐MEG2 and how these PTP‐MEG2‐mediated dephosphorylation events regulate fusion pore dynamics.

Results

Phosphatase activity of PTP‐MEG2 is required for catecholamine secretion from adrenal glands

Endogenous PTP‐MEG2 expression was readily detected in mouse adrenal gland and chromaffin cell line PC12 cells (Appendix Fig S1A and B). Because PTP‐MEG2 knockout is embryonic lethal (Wang et al, 2005), we applied our newly developed active site‐directed and active site‐specific PTP‐MEG2 inhibitor (Compound 7) to investigate the functional roles of PTP‐MEG2 in catecholamine secretion from adrenal glands (Appendix Fig S1C). Compound 7 is a potent and cell‐permeable PTP‐MEG2 inhibitor, with a K i value of 34 nM and extraordinary selectivity against other phosphatases (Zhang et al, 2012). The administration of either high concentrations of potassium chloride (70 mM) or 100 nM angiotensin II (AngII) significantly increased the secretion of both epinephrine (EPI) and norepinephrine (NE) from the adrenal medulla as previously reported (Teschemacher & Seward, 2000; Liu et al, 2017), and this effect was specifically blocked by pre‐incubation with Compound 7 (400 nM) for 1 h (Fig 1A–D). Notably, basal catecholamine secretion also decreased after pre‐incubation with Compound 7 (Fig 1A–D). However, the intracellular catecholamine contents did not change in response to Compound 7 incubation (Appendix Fig S1D and E). These results indicate that PTP‐MEG2 plays an essential role in catecholamine secretion from the adrenal medulla.

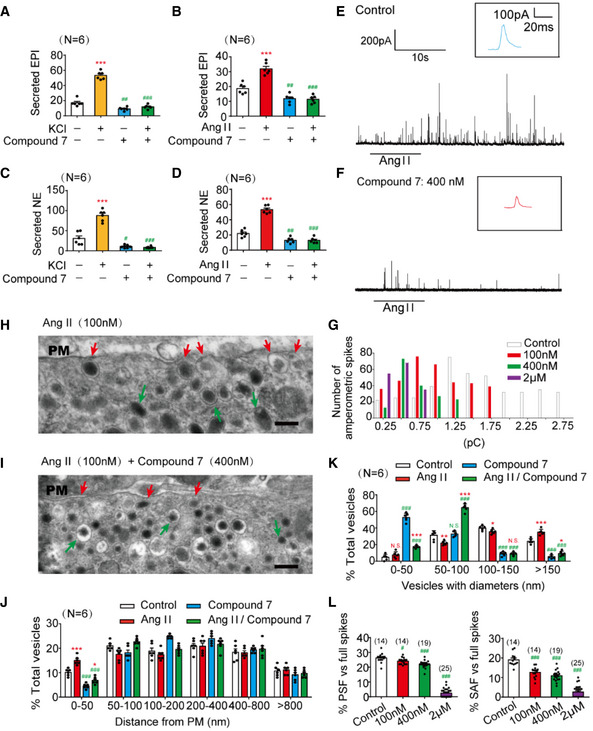

Figure 1. Inhibition of PTP‐MEG2 reduced the spike amplitude and “foot” probability of catecholamine secretion.

-

A–DThe epinephrine (A, B) or norepinephrine (C, D) secreted from the adrenal medulla was measured by ELISA method after stimulation with high KCl (70 mM) (A, C) or angiotensin II (AngII, 100 nM) (B, D) for 1 min, with or without pre‐incubation with a specific PTP‐MEG2 inhibitor (400 nM) for 1 h.

-

E, FAmperometric spikes of primary mouse chromaffin cells induced by AngII (100 nM) were determined by electrochemical experiments after incubation with PTP‐MEG2 inhibitor at different concentrations.

-

GThe distribution of the quantal size of AngII (100 nM)‐induced amperometric spikes by primary chromaffin cells after incubation with different concentrations of PTP‐MEG2 inhibitor. Histograms show the number of amperometric spikes of different quantal sizes.

-

H, ISecretory vesicles of primary chromaffin cells were examined by transmission electron microscopy after 100 nM AngII stimulation, with or without pre‐incubation with 400 nM Compound 7. Scale bars: (H, I), 150 nm. Red arrows indicate morphologically docked LDCVs, and green arrows stand for undocked LDCVs. PM represents plasma membrane.

-

JVesicle numbers according to different distances from the plasma membrane were calculated in the presence or absence of 100 nM AngII or 400 nM Compound 7. PM represents plasma membrane.

-

KThe percentage of vesicles with different diameters was measured after 100 nM AngII stimulation or incubation with 400 nM Compound 7. Compound 7 significantly decreased vesicle size under AngII stimulation.

-

LThe percentage of pre‐spike foot (PSF) (left panel) and stand‐alone foot (SAF) (right panel) was calculated after incubation with the indicated concentrations of Compound 7.

Data information: Data were analyzed using one‐way ANOVA and displayed as the mean ± s.e.m. (A–D, J–L) *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001: cells stimulated with KCl or AngII compared with un‐stimulated cells. # P < 0.05; ## P < 0.01; ### P < 0.001: cells pre‐incubated with PTP‐MEG2 inhibitors compared with control vehicles. N.S. means no significant difference. Data were from 6 (A–D, J–K) or 8 (L) independent experiments. # indicates P < 0.05 and ### indicates P < 0.001 compared with control group.

PTP‐MEG2 inhibition reduces the quantal size and the release probabilities of catecholamine secretion from individual vesicles

We used the carbon fiber electrode (CFE) to characterize the effects of PTP‐MEG2 inhibition on the kinetics of catecholamine secretion from primary cultured chromaffin cells (Chen et al, 2005; Harada et al, 2015; Fig 1E and F, Appendix Fig S1F and G). The Ang II‐induced catecholamine secretion was gradually attenuated by increasing the concentration of Compound 7 after pre‐incubation with the primary chromaffin cells, from 20% at 100 nM Compound 7 to 80% at 2 μM Compound 7 (Fig 1E and F, Appendix Fig S1F–H). We then compared individual amperometric spikes of chromaffin cells pre‐incubated with different concentrations of Compound 7 to determine the effect of PTP‐MEG2 inhibition on quantal size (total amperometric spike charge) and vesicle release probabilities. The application of PTP‐MEG2 inhibitor reduced quantal size, as indicated by statistical analysis of the quantal size distribution and averaged amperometric spike amplitude (Fig 1G and Appendix Fig S1I). Specifically, the peak of the amperometric spikes decreased from 1.1 pC to 0.5 pC after incubation with 400 nM Compound 7 (Fig 1G). The number of AngII‐induced amperometric spikes also significantly decreased in the presence of Compound 7 (Appendix Fig S1J).

We then used transmission electron microscopy to examine the location of the large‐dense‐core vesicles (LDCVs) in the adrenal medulla after incubation with AngII and Compound 7 (Fig 1H and I, Appendix Fig S2A and B). The intracellular distribution of the LDCVs was summarized by 50 nm bins according to their distance from the chromaffin plasma membrane (Fig 1J). Vesicles with distance less than 50nm were generally considered to be in the docking stage. Here we found that the application of 400 nM Compound 7 significantly decreased the number of docking vesicles in contact with the plasma membrane (Fig 1J). Moreover, Compound 7 significantly increased the number of LDCVs with a diameter less than 50 nm and decreased the number of LDCVs with a diameter > 150 nm (Fig 1K), consistent with the statistical analysis of the total amperometric spike charge obtained by electrochemical measurements (Appendix Fig S1H–M). This change of vesicle size in the adrenal medulla was in accordance with the functional studies of PTP‐MEG2 in immunocytes, which identified that vesicles were excessively larger if PTP‐MEG2 was overexpressed (Huynh et al, 2004).

PTP‐MEG2 regulates the initial opening of the fusion pore

Generally, the presence of pre‐spike foot (PSF) is a common phenomenon preceding large amperometric spikes which indicate catecholamine secretion in chromaffin cells, while stand‐alone foot (SAF) is considered to represent “kiss‐and‐run” exocytosis (Chen et al, 2005). Both PSF and SAF are usually considered as indications of the initial opening of the fusion pore (Alvarez de Toledo et al, 1993; Zhou et al, 1996). In the present study, Compound 7 substantially decreased the PSF frequency from 25 to 3% and attenuated the SAF frequency from 18 to 4% in response to AngII stimulation (Fig 1L). Consistent with PSF/SAF frequency, the inhibitor Compound 7 also decreased the average duration, amplitude, and charge (Appendix Fig S2C–J).

The crystal structure of the PTP‐MEG2/phospho‐NSF complex reveals significant structural rearrangements in the WPD loop and β3‐loop‐β4

PTP‐MEG2 is known to modulate interleukin‐2 secretion in macrophages via dephosphorylation of NSF, a key regulator in vesicle fusion (Huynh et al, 2004). In response to stimulation with either high potassium chloride or AngII, the two stimulators for catecholamine secretion from the adrenal medulla, the tyrosine phosphorylation of NSF increased, indicating that NSF phosphorylation actively participates in catecholamine secretion (Fig 2A, Appendix Fig S3A and B). Moreover, a significant portion of NSF co‐localized with PTP‐MEG2 in the adrenal medulla upon AngII stimulation, and the substrate‐trapping mutant PTP‐MEG2‐D470A interacted with the tyrosine‐phosphorylated NSF from the adrenal medulla treated with hydrogen peroxide (Fig 2B–D, Appendix Fig S3C–E), suggesting that PTP‐MEG2 regulates catecholamine secretion in chromaffin cells through direct dephosphorylation of NSF. Hydrogen peroxide was used to elevate the overall protein tyrosine phosphorylation levels in cells because it is permeable to cell and can oxidize the catalytic cysteine located in the active site of the PTP catalytic domains (Kanda et al, 2006; Frijhoff et al, 2014).

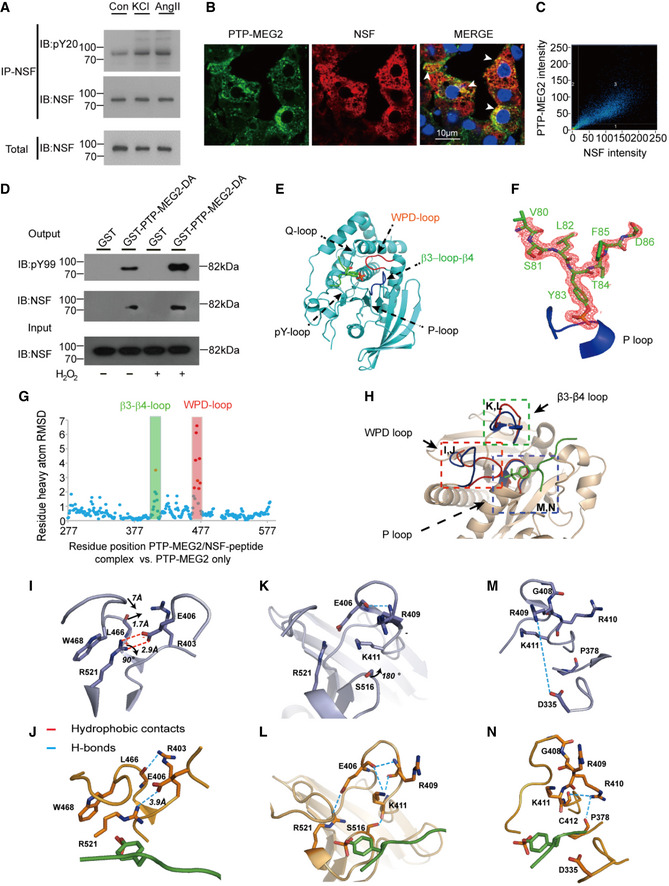

Figure 2. Interaction of PTP‐MEG2 and tyrosine‐phosphorylated NSF in the medulla and the crystal structure of the PTP‐MEG2/phospho‐NSF‐segment complex.

-

ANSF was phosphorylated after stimulation with AngII or KCl. Adrenal medulla cells were stimulated with 100 nM AngII or 70 mM KCl for 5 min and lysed. NSF was immunoprecipitated with a specific NSF antibody coated with Protein A/G beads. A pan‐phospho‐tyrosine antibody pY20 was used in Western blot to detect the tyrosine‐phosphorylated NSF in the adrenal medulla under different conditions.

-

BNSF was co‐localized with PTP‐MEG2 in the adrenal medulla. After stimulation with 100 nM AngII, NSF and PTP‐MEG2 in the adrenal medulla were visualized with immunofluorescence. White arrow stands for co‐localization of the PTP‐MEG2 and NSF.

-

CAnalysis of PTP‐MEG2 and NSF fluorescence intensities by Pearson’s correlation analysis. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was 0.7.

-

DPhosphorylated NSF interacted with PTP‐MEG2. PC12 cells were transfected with FLAG‐NSF. After stimulation of the cells with 100nM AngII in the presence or absence of 100 μM H2O2 for 5 min (H2O2 was exploited to increase the overall tyrosine phosphorylation of the cellular proteins), the potential PTP‐MEG2 substrate in cell lysates was pulled down with GST‐PTP‐MEG2‐D470A or GST control.

-

EThe overall structure of PTP‐MEG2‐C515A/D470A in complex with the NSF‐pY83 phospho‐segment.

-

FThe 2Fo‐Fc annealing omit map (contoured at 1.0σ) around the NSF‐pY83 phospho‐segment. The P‐loop was highlighted in blue.

-

GPlot of distance RMSDs of individual residues between the crystal structures of the PTP‐MEG2/NSF‐pY83 phospho‐peptide complex (PDB: 6KZQ) and the PTP‐MEG2 native protein (PDB: 2PA5).

-

HSuperposition of the PTP‐MEG2/NSF‐pY83 phospho‐peptide complex structure (red) on the PTP‐MEG2 native protein structure (PDB: 2PA5, blue). The structural rearrangement of the WPD loop and β3‐loop‐β4 is highlighted.

-

I, JThe closure of the WPD loop and corresponding conformational changes in the inactive state (I) and the active state (J) of PTP‐MEG2. The rotation of R521 leads to the movement of W468 and a corresponding 7 Å movement of the WPD loop.

-

K, LThe structural rearrangement of β3‐loop‐β4 of PTP‐MEG2 in the active state (L) compared with the inactive state (K). The disruption of the salt bridge between E406 and R521 contributed to the new conformational state of the N‐terminal of β3‐loop‐β4.

-

M, NThe conformational change of the P‐loop of the inactive state (M) and the active state of PTP‐MEG2 in response to NSF‐pY83 segment binding (N). The disruption of the charge interaction between R409 and D335 resulted in the movement of the main chain from G408 to K411.

We therefore co‐crystallized PTP‐MEG2/phospho‐NSF‐E79‐pY83‐K87, and the structure was solved at 1.7 Å resolution (Table 1). The 2Fo‐Fc electron density map allowed for the unambiguous assignment of the phospho‐NSF‐E79‐pY83‐K87 in the crystal structure (Fig 2E and F). Importantly, the binding of phospho‐NSF‐E79‐pY83‐K87 induced substantial conformational changes in both the WPD loop and β3‐loop‐β4 compared to the crystal structure of PTP‐MEG2 alone (Barr et al, 2009; Fig 2G and H). Specifically, the interaction of the phosphate group of pY83 of NSF with the guanine group of R521 of PTP‐MEG2 induced rotation of approximately 90 degrees, which resulted in the movement of W468 and a traverse of 7 Å of the WPD loop for a closed state (Fig 2I and J). Unique to the PTP‐MEG2/substrate complex, the movement of L466 in the WPD loop by 1.7 Å enabled the formation of a new hydrogen bond between its main chain carbonyl group and the side chain of R403 (Fig 2I and J). The disruption of the salt bridge between E406 and R521 also contributed to the new conformational state of the N‐terminal of the β3‐loop‐β4 (Fig 2K and L). The presence of the phosphate in the PTP‐MEG2 active site C‐terminal to β3‐loop‐β4 caused a 180‐degree rotation of the side chain of S516, allowing its side chain oxygen to form a new hydrogen bond with the main chain carbonyl of group K411 (Fig 2K and L). This structural rearrangement altered the side chain conformation of K411, which pointed to the solvent region and formed new polar interactions with E406 and the carbonyl group of R409 (Fig 2K and L). Moreover, the presence of the phospho‐NSF‐E79‐pY83‐K87 peptide between R409 and D335 disrupted their charge interactions, enabling a movement of the main chain from G408 to K411, accompanied by a side chain movement of R410 and the formation of new polar interactions with the main chain of P378 and C412 (Fig 2M and N). These structural rearrangements that occurred in the WPD loop and β3‐loop‐β4 enabled the accommodation of the phospho‐substrate of PTP‐MEG2 and may be important for its appropriate interactions with its physiological substrates/partners and subsequent activation.

Table 1.

Crystallographic data and refinement statistics.

| Data collection | PTP‐MEG2. NSF pY83 peptide | PTP‐MEG2. MUNC18‐1 pY145 peptide |

|---|---|---|

| Space group | p21212 | p21212 |

| Cell dimensions | ||

| a (Å) | 71.447 | 71.048 |

| b (Å) | 83.708 | 84.074 |

| c (Å) | 48.615 | 48.753 |

| α (deg) | 90 | 90 |

| β (deg) | 90 | 90 |

| γ (deg) | 90 | 90 |

| Resolution (Å) | 80–1.70 (1.76–1.70) a | 54.3–2.08 (2.08–2.20) a |

| Unique observations | 32,748 (3167) a | 18,019 (1773) a |

| Completeness (%) | 99.6 (98.3) a | 99.8 (99.8) a |

| Redundancy | 3.8 (3.8) a | 6.1 (6.3) a |

| <I>/<σ> | 22.22 (2.34) a | 6.5 (2.3) a |

| R merge | 0.064 (0.477) a | 0.191 (0.927) a |

| Structure refinement | 80–1.70 | |

| Resolution (Å) | 1.70 | 2.08 |

| Reflections used for R work/R free | 31,212/1536 | 17,995/896 |

| R work /R free b (%) | 0.1900/0.2173 | 0.2102/0.2304 |

| Average B‐factor | ||

| Protein | 20.98 | 35.36 |

| Peptide | 31.525 | 53.25 |

| RMSD ideal bonds (Å) | 0.008 | 0.008 |

| RMSD ideal angles (deg) | 1.212 | 0.968 |

| Ramachandran plot (%) | ||

| Most favored | 93.73 | 93.56 |

| Allowed | 4.88 | 6.10 |

| Generously allowed | 1.39 | 0.34 |

| Disallowed | 0 | 0 |

The values in parentheses correspond to the highest resolution shell.

Each dataset was collected from a single crystal.

Structural basis of the PTP‐MEG2‐NSF interaction

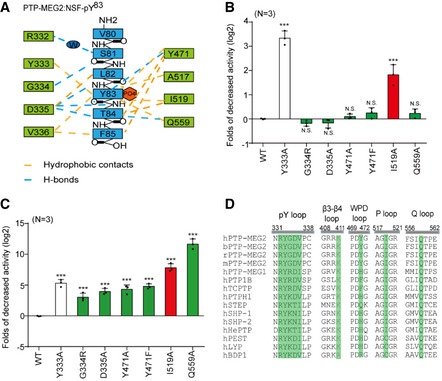

The structural analysis identified critical residues for the phospho‐substrate recognition by PTP‐MEG2 (Fig 3A). PTP‐MEG2 Y333 forms extensive hydrophobic interactions with the phenyl ring of pY83 in NSF. Mutation of this residue caused a significant decrease of more than 8‐fold in activity for both p‐nitrophenyl phosphate (pNPP) and the phospho‐NSF‐peptide (Fig 3B and C), suggesting that this residue is important for PTP‐MEG2 recognition of all substrates with phenyl rings. N‐terminal to pY83, the side chain oxygen of S81 formed a hydrogen bond with the carbonyl oxygen of the main chain of R332 of PTP‐MEG2. The carbonyl oxygen of the main chain of S81 formed a hydrogen bond with the amide group of G334, and L82 formed hydrophobic interactions with the side chain of D335 (Fig 3A). Specifically, mutation of G334 to R impaired the activity of PTP‐MEG2 toward the NSF‐pY83 phospho‐peptide but did not affect on its intrinsic phosphatase activity as measured by using pNPP as a substrate, suggesting that G334 plays an important role in the recognition of the N‐terminal conformation of the peptide substrate (Fig 3B and C, Appendix Table S1).

Figure 3. Molecular determinants of PTP‐MEG2 interaction with the NSF‐pY83 site.

- Schematic representation of interactions between PTP‐MEG2 and the NSF‐pY83 site.

- Relative values of the decreased phosphatase activities of different PTP‐MEG2 mutants toward pNPP (p‐Nitrophenyl phosphate) compared with wild‐type PTP‐MEG2.

- Fold change decreases in the phosphatase activities of different PTP‐MEG2 mutants toward the NSF‐pY83 phospho‐segment compared with wild‐type PTP‐MEG2.

- Sequence alignment of PTP‐MEG2 from different species and with other PTP members. Important structural motifs participating in phosphatase catalysis or the recognition of the NSF‐pY83 site are shown, and key residues contributing to the substrate specificity are highlighted.

Data information: ***P < 0.001: PTP‐MEG2 mutants compared with the control group. Data were obtained from 3 independent experiments. N.S. means no significant difference. All the data were analyzed using one‐way ANOVA and displayed as the mean ± s.e.m. In (B, C), the red column indicates that the mutation sites have greater effects on the enzyme activities toward phospho‐NSF segment than the pNPP. The green column indicates that the mutation sites only have significant effects on the enzyme activity toward NSF phospho‐segment but not pNPP. The white column stands for the mutants that have similar effects on pNPP and NSF phospho‐segment.

The D335 in the pY binding loop of PTP‐MEG2 is also critical for determining the peptide orientation of the substrate by forming important hydrogen bonds with the main chain amide and carbonyl groups of pY83 and T84 in NSF. Residues C‐terminal to NSF‐pY83, T84, and F85 formed substantial hydrophobic interactions with V336, F556, Q559, and Y471 (Fig 3A). Accordingly, mutation of D335A or Q559A showed no significant effect on pNPP activity but substantially decreased their activities toward the phospho‐NSF peptide (Fig 3B and C, Appendix Table S1). Mutation of I519A caused a decrease in the intrinsic activity of PTP‐MEG2 and a further decrease of approximately 256‐fold in its ability to dephosphorylate phospho‐NSF‐peptide. Moreover, Y471 formed extensive hydrophobic interactions with T84 and F85 and a hydrogen bond with the carboxyl group of pY83. Mutation of Y471 to either A or F greatly reduced its activity toward the phospho‐NSF‐E79‐pY83‐K87 peptide but had little effects on pNPP dephosphorylation. Taken together, the structural analyses and enzymological studies identified G334, D335, Y471, I519, and Q559 as critical residues for the substrate recognition of NSF by PTP‐MEG2. Importantly, although none of these residues are unique to PTP‐MEG2, the combination of these residues is not identical across the PTP superfamily but is conserved in PTP‐MEG2 across different species, highlighting the important roles of these residues in mediating specific PTP‐MEG2 functions (Fig 3D, Appendix Fig S4).

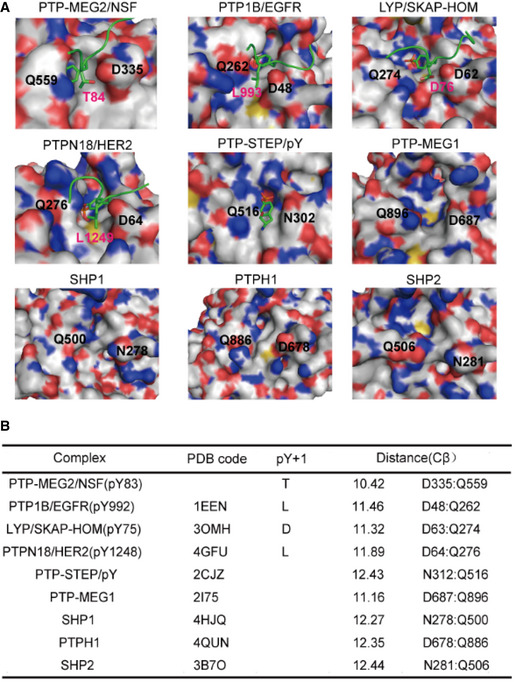

Molecular determinants of Q559:D335 for the substrate specificity of PTP‐MEG2

The pY + 1 pocket is an important determinant of substrate specificity in different PTP superfamily members (Barr et al, 2009; Yu et al, 2011; Wang et al, 2014; Li et al, 2016). The pY + 1 pocket of PTP‐MEG2 was found to consist of D335, V336, F556, and Q559 (Fig 4A). Unique to the PTP‐MEG2/NSF‐E79‐pY83‐K87 complex structure, a relatively small T84 residue occurred at the pY + 1 position, in contrast to L993 in the PTP1B/EGFR‐pY992 complex structure, D76 in the lymphoid‐specific tyrosine phosphatase (LYP)/ Src kinase‐associated protein of 55 kDa homolog (SKAP‐HOM)‐pY75 complex structure, and L1249 in the PTPN18/ human receptor tyrosine‐protein kinase erbB‐2 (HER2)‐pY1248 complex structure (Fig 4A). Although several PTPs have an equivalent D: Q pair similar to D335:Q559 of PTP‐MEG2 determining the entrance of the pY + 1 residue into the pY + 1 pocket, such as PTP1B, LYP, PTPN18, Striatum‐enriched protein tyrosine phosphatase (STEP), PTP‐MEG1, SHP1, PTPH1, and SHP2, structural analysis indicated that the Cβ between Q559 and D335 is the smallest in PTP‐MEG2, at least 1 Å narrower than the other PTP structures examined (Fig 4B). The narrower pY + 1 pocket entrance could be a unique feature for substrate recognition by PTP‐MEG2.

Figure 4. The tip opening of the pY + 1 pocket is critical for PTP‐MEG2 substrate specificity.

- Surface representations of the complex structures of PTP‐MEG2‐C515A/D470A/NSF‐pY83, PTP1B‐C215A/EGFR‐pY992 (PDB: 1EEN), LYP‐C227S/SKAP‐HOM‐pY75 (PDB: 3OMH), PTPN18‐C229S/HER2‐pY1248 (PDB: 4GFU), and PTP‐STEP/pY (PDB: 2CJZ). Crystal structures of PTP‐MEG1 (PDB: 2I75), SHP1 (PDB: 4HJQ), PTPH1 (PDB: 4QUN), and SHP2 (PDB: 3B7O). The pY + 1 sites are highlighted.

- Summary of the distance between the Cβ atoms of D335 and Q559 (corresponding to PTP‐MEG2 number) of the pY + 1 pocket in PTP‐MEG2 and other classical non‐receptor PTPs bearing the same residues at similar positions.

PTP‐MEG2 regulates two different steps of catecholamine secretion through dephosphorylation of different substrates

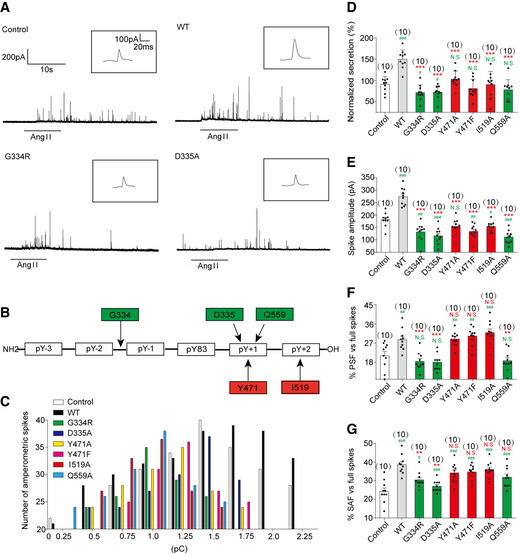

We then infected primary chromaffin cells with lentivirus encoding wild‐type PTP‐MEG2 or different mutants for electrochemical investigation of the structure–function relationship of PTP‐MEG2 in the regulation of catecholamine secretion (Fig 5A, Appendix Figs S5A–G and S6A–D). In addition to the wild‐type PTP‐MEG2, we chose 6 PTP‐MEG2 mutants, including G334R, D335A, Y471A, Y471F, I519A, and Q559A, whose positions are determinants of the interactions between PTP‐MEG2 and NSF from the pY83‐1 position to the pY83 + 2 position (Fig 5B). Cells with approximately 15‐fold of overexpressed exogenous PTP‐MEG2 wild type or mutants than the endogenous PTP‐MEG2 were selected for electrochemical studies (Appendix Fig S5E and F). The PTP‐MEG2 mutations did not significantly affect its interaction with NSF, suggesting that residues not located within the active site of PTP‐MEG2 may also participate in NSF associations (Appendix Figs S5G). The overexpression of wild‐type PTP‐MEG2 significantly increased both the number and amplitude of the amperometric spikes, which are indicators of the release probabilities of individual vesicles and their quantal sizes, respectively (Fig 5C–E, Appendix Fig S6E). In contrast, the expression of G334R, D335A, Y471A, Y471F, I519A, and Q559A all significantly decreased the quantal size, the release probabilities of individual vesicles, the half‐width, and the rise rate of each spike (Fig 5C–E, Appendix Fig S6E, F and H). However, there was no difference in the rise time between these mutations and the wild type (Appendix Fig S6G). These results suggest that the interaction of PTP‐MEG2 with NSF is important for controlling vesicle size and the release probability of catecholamine secretion.

Figure 5. Effects of different PTP‐MEG2 mutants on properties of catecholamine secretion from primary chromaffin cells.

-

APrimary mouse chromaffin cells were transduced with a lentivirus containing the gene for wild‐type PTP‐MEG2 or different mutants with a GFP tag at the C‐terminus. Positive transfected cells were confirmed with green fluorescence and selected for electrochemical analysis. Typical amperometric current traces evoked by AngII (100 nM for 10 s) in the control (transduced with control vector) (top left panel), WT (top right panel), G334R (bottom left panel), and D335A (bottom right panel) are shown.

-

BThe schematic diagram shows key residues of PTP‐MEG2 defining the substrate specificity adjacent to the pY83 site of NSF.

-

CThe distribution of the quantal size of chromaffin cells transduced with lentivirus containing the genes encoding different PTP‐MEG2 mutants.

- D

-

E–GCalculated parameters of secretory dynamics, including the spike amplitude (E), PSF frequency (F), and SAF frequency (G).

Data information: (B, D–G) Green color represents the amino acids which are found to modulate foot probability based on structure analysis, and red color means amino acids which does not regulate foot probability. (D–G), * indicates PTP‐MEG2 mutant overexpression group compared with the WT overexpression group. # indicates the overexpression group compared with the control group. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 and # P < 0.05; ## P < 0.01; ### P < 0.001. N.S. means no significant difference. Data were from six independent experiments. All the data were analyzed using one‐way ANOVA and showed as the mean ± s.e.m.

Unexpectedly, the PTP‐MEG2 mutants showed different effects on the probabilities of both PSF and SAF (Fig 5F and G). G334R mutation which disrupted the recognition of the N‐terminal conformation of the peptide substrate of PTP‐MEG2, and D335A and Q559A, which are the determinants of pY + 1 substrate specificity, significantly reduced the AngII‐induced foot probabilities. The mutations of I519 and Y471, which formed specific interactions with T84 and F85 of NSF and are determinants of the C‐terminal region of the central phospho‐tyrosine involved in the substrate specificity of PTP‐MEG2, showed no significant effects (Fig 5B, F and G, Appendix Fig S6I–N). These results indicate that PTP‐MEG2 regulates the initial opening of the fusion pore via a distinct structural basis from that of vesicle fusion, probably through dephosphorylating other unknown substrates. As D335A and Q559A of PTP‐MEG2 maintained the occurrence of the foot probability, the unknown PTP‐MEG2 substrate that regulates the fusion pore opening should have a small residue, such as G, A, S, or T at the pY + 1 position. Conversely, the unknown PTP‐MEG2 substrate should have a less hydrophobic residue at the pY + 2 position because Y471F, Y471A, and I519A of PTP‐MEG2 had no significant effects on the foot probability.

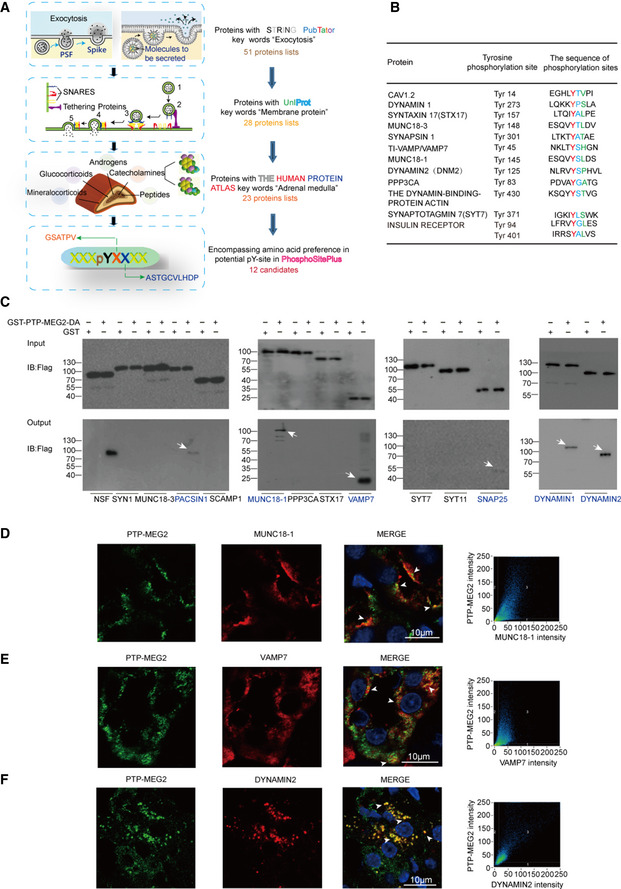

Identification of new PTP‐MEG2 substrates that contributed to the initial opening of the fusion pore

The effects of PTP‐MEG2 mutations along the PTP‐MEG2/NSF phospho‐segment interface on catecholamine secretion indicated that a PTP‐MEG2 substrate other than NSF with distinct sequence characteristics contributes to the regulation of “foot probability” (Fig 5). We therefore utilized this key information to search for new potential PTP‐MEG2 substrates by bioinformatics methods (Fig 6A). First, we searched for the keywords “fusion pore”, “secretory vesicle” and “tyrosine phosphorylation” using the functional protein association network STRING and the text mining tool PubTator, which resulted in a candidate list of 51 proteins (Appendix Table S2, Table EV1). Second, we applied UniProt by selecting proteins located only in the membrane or vesicle, which limited the candidates to 28 members (Appendix Table S3). Third, as our experiments were carried out in the adrenal gland, we used the Human Protein Atlas database for filtering to exclude the proteins which is not detectable in adrenal gland, which narrowed the candidate list to 23 proteins. Finally, we exploited the post‐translational‐motif database PhosphoSitePlus to screen candidate proteins with potential phospho‐sites that matched the sequence requirements at both the pY + 1 position and the pY + 2 position, which are “G, S, A, T, V, P” and “G, A, S, T, C, V, L, P, D, H”, respectively. These positions were further evaluated by surface exposure if a structure was available. The combination of these searches produced 12 candidate lists with predicted pY positions (Fig 6B).

Figure 6. Identification of potential candidate substrates of PTP‐MEG2 that participate in fusion pore initiation and expansion.

-

AFlowchart for the workflow to predict the candidate substrates of PTP‐MEG2 during fusion pore initiation and expansion. A total of 51 proteins were enriched with the functional protein association network STRING and the text mining tool PubTator by searching the keywords “fusion pore”, “secretory vesicle” and “tyrosine phosphorylation”. These proteins were filtered with UniProt by selecting proteins located only in the membrane or vesicle, which resulted in 28 candidates. The Human Protein Atlas database was then applied to exclude proteins with no expression in the adrenal gland. Finally, we used the post‐translational‐motif database PhosphoSitePlus to screen candidate proteins with potential phospho‐sites that matched our sequence motif prediction at the pY + 1 or pY + 2 positions.

-

BAfter the bioinformatics analysis, a total of 12 candidate PTP‐MEG2 substrates that may participate in fusion pore initiation and expansion and their potential phospho‐sites were displayed.

-

CThe GST pull‐down assay suggested that PACSIN1, MUNC18‐1, VAMP7, SNAP25, DYNAMIN1, and DYNAMIN2 directly interact with PTP‐MEG2. PC12 cells were transfected with plasmids of candidate substrates, including SYN1, MUNC18‐3, PACSIN1, SCAMP1, MUNC18‐1, PPP3CA, STX17, VAMP7, SYT7, SYT11, SNAP25, DYNAMIN1, and DYNAMIN2 stimulated with 100 nM AngII. The tyrosine phosphorylation of these proteins was verified by specific anti‐pY antibodies (Appendix Fig S8A–E). The potential substrates of PTP‐MEG2 in cell lysates were pulled down with a GST‐PTP‐MEG2‐D470A trapping mutant and then detected by Western blot. White arrow stands for Western blot band consistent with the predicted molecular weight of the potential PTP‐MEG2 substrate.

-

D–FCo‐immunostaining assays of PTP‐MEG2 with potential substrates in the adrenal medulla. MUNC18‐1, VAMP7, and DYNAMIN2 all showed strong co‐localization with PTP‐MEG2 after 100 nM AngII stimulation in the adrenal medulla. White arrow stands for co‐localization of PTP‐MEG2 with MUNC18‐1, VAMP7, or DYNAMIN2. Pearson’s correlation coefficients for (D, E, and F) were 0.61, 0.65, and 0.79 respectively. The co‐immunostaining results of PTP‐MEG2 with other potential substrates are shown in Appendix Fig S7.

To biochemically characterize whether these proteins are substrates of PTP‐MEG2, we transfected the plasmids encoding the cDNAs of these candidate proteins into PC12 cells, stimulated the cells with AngII, and performed a pull‐down assay with the GST‐PTP‐MEG2‐D470A trapping mutant or GST controls. The known PTP‐MEG2 substrate NSF was used as a positive control. Notably, six candidates, including protein kinase C and casein kinase substrate in neurons protein 1 (PACSIN1), MUNC18‐1, vesicle‐associated membrane protein 7 (VAMP7), synaptosomal‐associated protein 25 (SNAP25), DYNAMIN1, and DYNAMIN2, showed specific interactions with PTP‐MEG2 after AngII stimulation in PC12 cells (Fig 6C, Appendix Fig S7A and B). Whereas the protein of MUNC18‐1, VAMP7, DYNAMIN2, and SNAP25 was readily detected in the adrenal medulla, DYNAMIN1 and PACSIN1 showed substantially lower expression than that in the liver and brain (Appendix Fig S7C). Moreover, whereas MUNC18‐1, VAMP7, and DYNAMIN2 strongly co‐localized with PTP‐MEG2 in the adrenal medulla (Fig 6D–F), the co‐localization of SNAP25 and PACSIN1 with PTP‐MEG2 was relatively weak (Appendix Fig S7D and E). Therefore, MUNC18‐1, VAMP7, and DYNAMIN2 are more likely candidate PTP‐MEG2 substrates which were further strengthened by the fact that the high potassium chloride‐ or AngII‐stimulated tyrosine phosphorylation of these proteins in the adrenal medulla was significantly dephosphorylated by PTP‐MEG2 in vitro (Appendix Fig S8A–C and E), whereas the tyrosine phosphorylation of SNAP25 had no obvious change (Appendix Fig S8D and E).

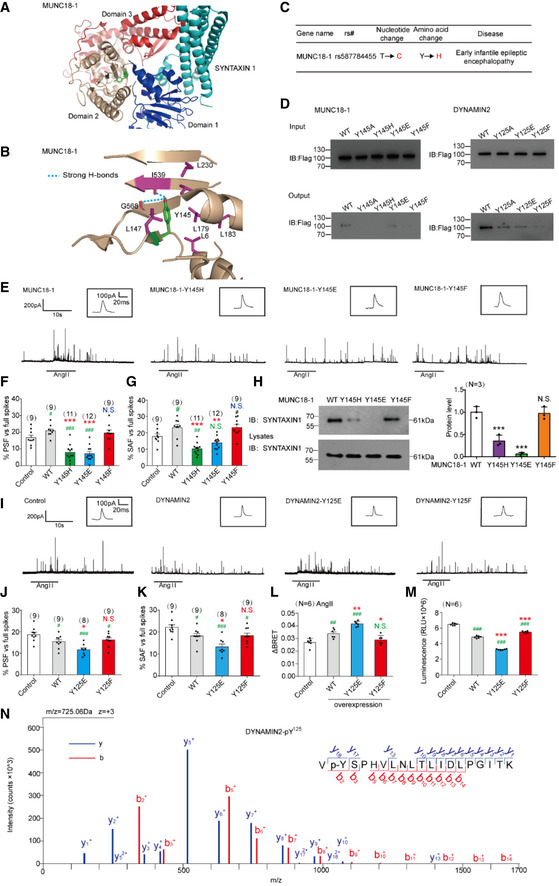

PTP‐MEG2 regulates the initial opening of the fusion pore through dephosphorylating MUNC18‐1‐ pY145

The predicted PTP‐MEG2 dephosphorylation site on MUNC18‐1 (also called STXBP1) is Y145, which localizes on the β sheet linker and forms extensive hydrophobic interactions with surrounding residues (Hu et al, 2011; Yang et al, 2015; Fig 7A, Appendix Fig S9A). Moreover, the phenolic oxygen of Y145 forms specific hydrogen bonds with the main chain amide of F540 and the main chain carbonyl oxygens of I539 and G568 (Fig 7B). These key interactions might be involved in regulating the arrangement of the arc shape of the three domains of MUNC18‐1, by tethering the interface between domain 1 and domain 2. The phosphorylation of Y145 likely abolishes this H‐bond network and changes its ability to associate with different snare complexes participating in vesicle fusion procedures (Fig 7B). Interestingly, a missense mutation of MUNC18‐1 Y145H was found to be associated with early infantile epileptic encephalopathy (Stamberger et al, 2017; Fig 7C).

Figure 7. Dephosphorylations of MUNC18‐1 at the pY145 site and DYNAMIN2 at the pY125 site by PTP‐MEG2 determine the “foot” probability of catecholamine secretion from chromaffin cells.

-

AStructural representation and location of MUNC18‐1‐Y145 in the complex structure of MUNC18‐1‐SYNTAXIN1 (PDB: 3PUJ).

-

BDetailed structural representation of MUNC18‐1‐Y145 and its interactive residues. Y145 of MUNC18‐1 interacts with the main chain carboxylic oxygen of residues I539 and G568 and forms hydrophobic interactions with L6, I539, L147, L179, L183, and L230 to tether the arc shape of the three domains of MUNC18‐1 (PDB: 3PUJ).

-

CAssociation analysis of SNPs of MUNC18‐1 with human disease.

-

DInteractions of the PTP‐MEG2‐trapping mutants with the MUNC18‐1‐Y145 mutants and DYNAMIN2‐Y125 mutants. PC12 cells were transfected with FLAG‐MUNC18‐1‐Y145, FLAG‐DYNAMIN2‐Y125 and different mutations of the FLAG‐MUNC18‐1‐Y145A, Y145H, Y145E or Y145F, FLAG‐DYNAMIN2‐Y125A, Y125E, Y125F, 24 h before stimulation with 100 nM AngII, respectively. The cell lysates were then incubated with GST beads‐PTP‐MEG2‐D470A complex for 2 h with constant rotation. The potential PTP‐MEG2 substrates were pulled down by GST beads, and their levels were examined by the FLAG antibody with Western blot.

-

EPrimary chromaffin cells were transduced with lentivirus containing the gene encoding wild‐type MUNC18‐1 or different mutants. These cells were stimulated with 100 nM AngII. The amperometric spikes were detected with electrochemical experiments. Typical amperometric traces are shown.

-

F, GThe percentages of pre‐spike foot (F) and stand‐alone foot (G) for wild‐type MUNC18‐1 or different mutants were calculated.

-

HThe MUNC18‐1‐Y145 mutations decreased the interaction between MUNC18‐1 and SYNTAXIN1. PC12 cells were transfected with plasmid encoding SYNTAXIN‐1. The proteins in cell lysates were pulled down with purified GST beads‐MUNC18‐1‐Y145 complex and the GST‐MUNC18‐1‐Y145H/E/F, and detected with SYNTAXIN1 antibody. The right histogram shows the quantified protein levels.

-

IPrimary chromaffin cells were transduced with lentivirus containing the gene encoding wild‐type DYNAMIN2 or different mutants. These cells were stimulated with 100 nM AngII. The amperometric spikes were detected with electrochemical experiments. Typical amperometric traces are shown.

-

J, KThe percentages of pre‐spike foot (J) and stand‐alone foot (K) for wild‐type DYNAMIN2 or different mutants were calculated.

-

LPlasmids encoding DYNAMIN2 (DYNAMIN2‐WT, DYNAMIN2‐Y125E or DYNAMIN2‐Y125F) and LYN‐YFP, AT1aR‐C‐RLUC were co‐transferred into HEK293 cells at 1:1:1 ratio. The BRET experiment was performed to monitor the mutation effects of DYNAMIN2 on AT1aR endocytosis in response to AngII (1 μM) stimulation.

-

MThe GTPase assay was performed to detect the GTPase activity of the DYNAMIN2‐WT, DYNAMIN2‐Y125E, and DYNAMIN2‐Y125F. Purified DYNAMIN2 proteins were incubated with 5 μM GTP in the presence of 500 μM DTT for 90 min, followed by addition of GTPase‐Glo™ Reagent and detection reagent. The luminescence was measured after 37‐min incubation.

-

NPhosphorylated Y125 of DYNAMIN2 was identified by LC‐MS/MS. The PTP‐MEG2‐D470A trapping mutant was used to pull down potential PTP‐MEG2 substrates from the adrenal lysates after AngII stimulation. Trypsin‐digested potential PTP‐MEG2 substrates were subjected to LC‐MS/MS analysis. The doubly charged peptide with m/z 725.06 matches VYSPHVLNLTLIDLPGITK of DYNAMIN2 with Y125 phosphorylation.

Data information: (F–H, J–M) * indicates MUNC18‐1, DYNAMIN2 mutant overexpression group compared with the WT overexpression group. # indicates MUNC18‐1, DYNAMIN2 overexpression group compared with the control group. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 and # P < 0.05; ## P < 0.01; ### P < 0.001. N.S. means no significant difference. Data were from 6 (F, G, J, K, L, M) or 3 (H) independent experiments. All the data were analyzed using one‐way ANOVA, and showed as the mean ± s.e.m.

Notably, the Y145H missense mutation may not be phosphorylated properly. We therefore overexpressed wild‐type MUNC18‐1, Y145A, a non‐phosphorylable mutant, Y145E, a phosphomimetic mutant, Y145F, a non‐phosphomimetic mutant, and the disease‐related Y145H mutant in PC12 cells stimulated with AngII and then examined their abilities to interact with PTP‐MEG2 trapping mutant. The GST pull‐down results indicated that all MUNC18‐1 Y145 mutations significantly decreased their ability to associate with PTP‐MEG2 (Fig 7D, Appendix Fig S8G and H). In contrast, mutation of the predicted phosphorylation sites of SNAP25, the SNAP25‐Y101A, had no significant effect on their interactions with PTP‐MEG2 (Appendix Fig S8F–H). These results suggested that pY145 is one of the major sites of MUNC18‐1 regulated by PTP‐MEG2 (Fig 7D).

Next, primary chromaffin cells were infected by the following four types of lentivirus encoding wild‐type MUNC18‐1, the MUNC18‐1 Y145‐tyrosine phosphorylation‐deficient mutant Y145F, the MUNC18‐1 Y145‐tyrosine phosphorylation mimic mutant Y145E, and the disease‐related mutant Y145H. The Y145E is a phosphorylation mimic mutant of pY145, which generate a negative charge at this specific site. In contrast, the Y145F could not be phosphorylated because of lack of the phenolic oxygen. We examined the effects of these mutants using primary chromaffin cells harboring approximately 20~40‐fold MUNC18‐1 overexpression related to that of expression level of endogenous wild‐type MUNC18‐1 (Appendix Fig S9B–D). Interestingly, Y145E or Y145H of MUNC18‐1 significantly reduced the percentage of PSF and SAF of catecholamine secretion in response to AngII stimulation, whereas the phosphorylation‐deficient mutant Y145F showed no significant effects compared to that of the wild type (Fig 7E–G, and Appendix Figs S9 and S10).

In order to investigate the mechanism underlying the phosphorylation of MUNC18‐1 Y145 as well as the disease‐related mutant Y145H in the regulation of hormone secretion, we compared the interactions of wild‐type and mutant MUNC18‐1 with the binding partner SYNTAXIN1 (Lim et al, 2013). Importantly, both the phosphorylation mimic mutant MUNC18‐1‐Y145E and the disease‐related mutant Y145H significantly impaired the interaction between MUNC18‐1 and SYNTAXIN1 (Fig 7H, Appendix Fig S10C). The effects of MUNC18‐1 phospho‐mimic Y145E or phospho‐defective Y145F mutants on fusion pore dynamics are correlated with their abilities for interaction with the SYNTAXIN1, thus indicating that the binding between the MUNC18‐1 and SYNTAXIN1, which was controlled by the phosphorylation status of Y145 of MUNC18‐1, may play an important role in the formation of the fusion pore during catecholamine secretion. In contrast, the dephosphorylation of pY145 of MUNC18‐1 by PTP‐MEG2 promoted initial pore opening and fusion. Collectively, these results suggested that the tyrosine phosphorylation of Y145 impaired the initial opening of the fusion pore in agonist‐induced catecholamine secretion in the primary chromaffin cells. This is probably through either disrupting the arc shape of MUNC18‐1 or impairing the interaction between MUNC18‐1 and Syntaxin1. In addition, the effects of the mutations of MUNC18‐1 on protein stability were detected in response to cycloheximide (CHX) treatments. The results show that the mutations of MUNC18‐1 had no significant influence on protein stability, which suggested that the influence of MUNC18‐1 on “foot” parameters had no correlation with their degradation (Appendix Fig S12).

PTP‐MEG2 regulated the initial opening of the fusion pore through dephosphorylating DYNAMIN2‐pY125

Besides MUNC18‐1, two additional substrates of PTP‐MEG2, the Y45 site of VAMP7 and the Y125 site of DYNAMIN2, were confirmed by GST pull‐down assay (Fig 7D, Appendix Fig S8F–H). It was well known that DYNAMIN1 and DYNAMIN2, both active regulators of pore fusion dynamics, involved in the pore establishment, stabilization, constriction, and fission processes (Zhao et al, 2016; Jones et al, 2017; Shin et al, 2018). The dephosphorylation site of DYNAMIN2 by PTP‐MEG2, the Y125, is located in a β‐sheet of DYNAMIN GTPase domain according to the DYNAMIN1 structure (PDB ID: 5D3Q). Previous studies have identified that phosphorylation of DYNAMIN close to the G domain significantly increased its GTPase activity, thus promoted endocytosis (Kar et al, 2017). We hypothesized that the phosphorylation of the DYNAMIN2 pY125 site increased pore fission by up‐regulating its GTPase activity, whereas dephosphorylation of DYNAMIN2 pY125 site by PTP‐MEG2 reversed it. Consistent with the negative regulation role of DYNAMIN2 on pore fusion, the primary chromaffin cells transduced by lentivirus encoding DYNAMIN2 wild type and the Y125F mutant significantly decreased the percentage of the PSF and SAF of catecholamine secretion elicited by AngII. Importantly, the phosphorylation mimic mutant DYNAMIN2 Y125E exhibited significantly more reduction on the PSF and SAF percentage compared to that of the wild‐type DYNAMIN, indicating that the DYNAMIN Y125E is a gain of function mutant (Fig 7I–K, Appendix Fig S11). It has been demonstrated that the DYNAMIN‐mediated pore fission process is closely correlated with the receptor endocytosis. In accordance with their effects on percentage of PSF and SAF, overexpression of the DYNAMIN2 wild type or Y125E phospho‐mimic mutant markedly increased the AngII‐induced AT1aR endocytosis (Fig 7L; Liu et al, 2017). The in vitro GTPase activity further suggested that the phosphorylation of DYNAMIN2 at pY125 site up‐regulated its activity (Fig 7M). Moreover, the LS‐MS/MS verified the phosphorylation of DYNAMIN2 at pY125 site in primary adrenal medulla under AngII stimulation (Fig 7N, Appendix Table S4). Collectively, these results indicated that DYNAMIN2 pY125 phosphorylation occurred under AngII stimulation and negatively regulated the percentage of PSF and SAF of the AngII‐induced catecholamine secretion through increase the GTPase activity of DYNAMIN2. In addition, the effects of the mutations of DYNAMIN2 on protein stability were detected in response to cycloheximide (CHX) treatments. The results show that the mutations of DYNAMIN2 had no significant influence on protein stability, which suggested that the influence of DYNAMIN2 on “foot” parameters had no correlation with their degradation (Appendix Fig S12).

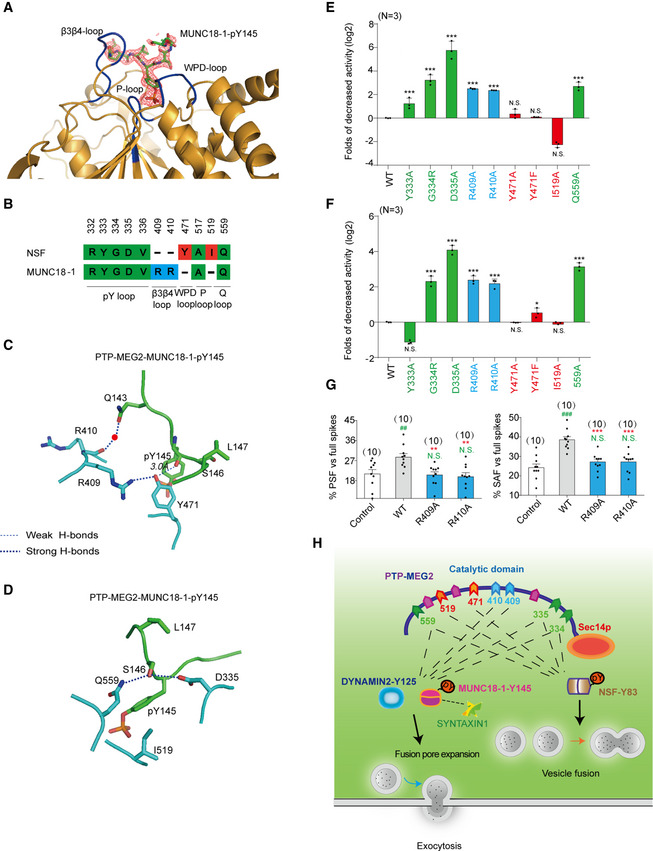

Molecular mechanisms of the interaction between PTP‐MEG2/MUNC18‐1‐pY145 and interaction between the PTP‐MEG2/DYNAMIN2‐pY125

The k cat/K m of PTP‐MEG2 toward a phospho‐segment derived from MUNC18‐1‐pY145 is very similar to that obtained with a phospho‐segment derived from the known substrate pY83 site of NSF (Appendix Table S1 and Appendix Table S5). We therefore crystallized the PTP‐MEG2 trapping mutant with the MUNC18‐1‐E141‐pY145‐S149 phospho‐segment and determined the complex structure at 2.2 Å resolution (Table 1). The 2Fo‐Fc electro‐density map allowed the unambiguous arrangement of seven residues of the phospho‐MUNC18‐1‐E141‐pY145‐S149 segment in the crystal structure (Fig 8A). Importantly, comparing with the phospho‐NSF‐E79‐pY83‐K87 segment, the phospho‐MUNC18‐1‐E141‐pY145‐S149 displayed different interaction patterns with the residues in the PTP‐MEG2 active site, forming new interactions with R409 and R410 but lost interactions with Y471 and I519 (Fig 8B). Whereas PTP‐MEG2 Y471 formed extensive hydrophobic interactions with NSF‐T84 and NSF‐F85, as well as a well‐defined hydrogen bond (2.4 Å) with the carbonyl oxygen of NSF‐pY83, PTP‐MEG2 Y471 formed only a weaker H‐bond with the carbonyl oxygen of MUNC18‐1‐pY145 due to a 0.62 Å shift of Y471 away from the central pY substrate (Fig 8C, Appendix Fig S13A). Similarly, PTP‐MEG2 I519 did not form specific interactions with the MUNC18‐1‐E141‐pY145‐S149 segment except for the central pY. In contrast, PTP‐MEG2 I519 formed specific hydrophobic interactions with NSF‐T84 (Fig 8D, Appendix Fig S13B). Consistently, mutations of PTP‐MEG2 Y471A, Y471F, or I519A significantly decreased the phosphatase activity toward the phospho‐NSF‐E79‐pY83‐K87 segment (Fig 3C) but had no significant effect on the phospho‐segments derived from both MUNC18‐1‐pY145 and DYNAMIN2 pY125 sites (Fig 8E and F, Appendix Table S5). Meanwhile, R409A and R410A mutations substantially decreased the catalytic activity toward phospho‐segments derived from both MUNC18‐1‐pY145 and DYNAMIN2 pY125 sites. This indicated that recognition of these substrates was mediated by common residues (Fig 8E and F, Appendix Table S5). Notably, the PTP‐MEG2 catalytic domain mutations showed no significant effects on the interactions between PTP‐MEG2 with the NSF, MUNC18‐1, and DYNAMIN2. This indicated that other domain of PTP‐MEG2, such as its sec14p domain, participated in the association of PTP‐MEG2 with these proteins (Appendix Figs S5G and S13C–F). With electrochemical studies, we further demonstrated that R409A and R410A mutations decreased the probability of both PSF and SAF (Fig 8G, Appendix Fig S14). It is worth to note that PTP‐MEG2 Y471A, Y471F, and I519A affect only the spike number and amount, but not the foot probability (Fig 5B–G). Collectively, our data suggested that PTP‐MEG2 regulated intracellular vesicle fusion by modulating the NSF‐pY83 phospho‐state but regulated the process of vesicle fusion pore initiation by dephosphorylating MUNC18‐1 at pY145 site and DYNAMIN2 at pY125 site (Fig 8H).

Figure 8. The structural details of the PTP‐MEG2‐MUNC18‐1‐Y145 interaction and catalytic bias of PTP‐MEG2 toward NSF‐pY83 and MUNC18‐1‐pY145 .

- The 2Fo‐Fc annealing omit map (contoured at 1.0σ) around MUNC18‐1‐pY145 phospho‐segment.

- Comparison of residues of PTP‐MEG2 interacting with NSF and MUNC18‐1. Amino acid residues of NSF and MUNC18‐1 are colored as follows: green, residues interacting with both NSF and MUNC18‐1; red, residues specifically contributing to NSF recognition; and blue, residues selectively contributing to MUNC18‐1 interaction.

- The structural alteration of the interactions surrounding Y471 of PTP‐MEG2 with the MUNC18‐1‐pY145 site.

- The structural alteration of the interactions surrounding I519 of PTP‐MEG2 with the MUNC18‐1‐pY145 site.

- Relative phosphatase activities of different PTP‐MEG2 mutants toward the MUNC18‐1‐pY145 phospho‐segment compared with wild‐type PTP‐MEG2.

- Relative phosphatase activities of different PTP‐MEG2 mutants toward the DYNAMIN 2‐pY125 phospho‐segment compared with wild‐type PTP‐MEG2.

- The percentages of PSF and SAF for PTP‐MEG2‐R409A or R410A were calculated.

- Schematic illustration of the PTP‐MEG2‐regulated processes of vesicle fusion and secretion in chromaffin cells via the dephosphorylation of different substrates with distinct structural basis. PTP‐MEG2 regulates vesicle fusion and vesicle size during the catecholamine secretion of adrenal gland by modulating the phosphorylation state of the pY83 site of NSF, which relies on the key residues G334, D335 (pY loop), Y471 (WPD loop), I519 (P‐loop), and Q559 (Q loop). PTP‐MEG2 regulates the fusion pore initiation and expansion procedures of catecholamine secretion by the adrenal gland (also designated as foot probability) by modulating the newly identified substrate MUNC18‐1 at its pY145 site and DYNAMIN2 at its pY125, through distinct structural basis from that of its regulation of NSF phosphorylation.

Data information: (E, F) Residues are colored according to Fig 8B. (E, F), *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001: PTP‐MEG2 mutants compared with the control. N.S. means no significant difference. Data were obtained from 3 independent experiments. (G), * indicates PTP‐MEG2‐R409A or R410A mutant overexpression group compared with the WT overexpression group. # indicates the PTP‐MEG2 overexpression group compared with the control group. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 and ## P < 0.01; ### P < 0.001. N.S. means no significant difference. Data were obtained from 10 cells in each group of 6 independent experiments. All the data were analyzed using one‐way ANOVA and showed as the mean ± s.e.m.

Discussion

Post‐translational modifications of secretion machinery proteins are known as powerful ways to regulate exocytosis. In contrast to the well‐characterized serine/threonine phosphorylation, the importance of tyrosine phosphorylation in exocytosis has only recently begun to be appreciated (Seino et al, 2009; Jewell et al, 2011; Cijsouw et al, 2014; Laidlaw et al, 2017; Meijer et al, 2018; Gabel et al, 2019). In addition to the phosphorylation of NSF at its pY83 site, recent studies have shown that tyrosine phosphorylation of MUNC18‐3 at the pY219 and pY527 sites, Annexin‐A2 at pY23, and MUNC18‐1 at pY473 actively participates in the vesicle release machinery to explicitly regulate exocytosis processes (Jewell et al, 2011; Meijer et al, 2018; Gabel et al, 2019). The tyrosine phosphorylation at specific sites of the signaling molecule is precisely regulated by protein tyrosine kinases and protein tyrosine phosphatases (Tonks, 2006; Yu & Zhang, 2018). Although tyrosine kinases such as the insulin receptor, Src, and Fyn are acknowledged to play critical roles in hormone secretion (Jewell et al, 2011; Soares et al, 2013; Meijer et al, 2018; Oakie & Wang, 2018), only a very few PTPs that regulate the vesicle release machinery have been identified, and the structural basis of how these PTPs selectively dephosphorylate the key tyrosine phosphorylation sites governing exocytosis was unknown. In the current study, we demonstrated that PTP‐MEG2 is an important regulator of hormone secretion from the chromaffin cell, using a selective PTP‐MEG2 inhibitor in combination with cellular and electrochemical amperometric recording. The current study extended the regulatory role of PTP‐MEG2 in various steps of exocytosis in hormone secretion beyond the previously known simple vesicle fusion step of the immune system (Huynh et al, 2004). We then determined the crystal structure of PTP‐MEG2 in complex with the pY83 phospho‐segment of the NSF, the key energy provider for disassembling fusion‐incompetent cis SNARE complexes in the process of vesicle fusion in immunocytes (Huynh et al, 2004). The complex structure not only revealed the structural rearrangement in PTP‐MEG2 in response to binding of the substrate NSF and identified Q559:D335 as the key pair for substrate specificity of the pY + 1 site, but also provided clues that PTP‐MEG2 regulated the initial opening of the fusion pore through another unknown substrate. Fortunately, we were able to deduce the signature of the pY + 1 and pY + 2 positions of this unknown substrate by carefully inspecting the PTP‐MEG2/phospho‐NSF‐E79‐pY83‐K87 complex structure and analyzing the functional data of the PTP‐MEG2 interface mutants. Further bioinformatics studies and cellular and physiological experiments enabled us to discover that PTP‐MEG2 regulates the initial opening of the fusion pore by modulating the tyrosine phosphorylation states of MUNC18‐1 at the pY145 site and DYNAMIN2 at the pY125 site. Therefore, we have revealed that PTP‐MEG2 regulates different steps of the exocytosis processes via dephosphorylating distinct substrates. PTP‐MEG2 regulates the vesicle size and vesicle–vesicle fusion step by dephosphorylating NSF at its NSF‐pY83 site, whereas it regulates the process of LDCV fusion pore initiation and expansion by controlling specific phosphorylation sites of MUNC18‐1 and DYNAMIN2. Moreover, our studies highlight that the combination of structural determination and functional delineation of the interface mutants of the protein complex is a powerful approach to characterizing the signaling events and identifying unknown downstream signaling molecules.

Fusion pore opening and expansion is thought to be a complex process requiring the docking of apposed lipid bilayers and involvement of multiple proteins to form a hemi‐fusion diaphragm including SNAREs, MUNC18‐1, and DYNAMIN (Sudhof & Rothman, 2009; Hernandez et al, 2012; Mattila et al, 2015; Baker & Hughson, 2016; Zhao et al, 2016; Jones et al, 2017). Dissection of the molecular mechanism underlying pore fusion dynamics in exocytosis is challenging because direct observation of this process is difficult to achieve due to the short expansion time and the tiny size of the pore (Hong & Lev, 2014; Baker & Hughson, 2016; Gaisano, 2017). Importantly, the DYNAMINs are key terminators of the fusion pore expansion by scissoring vesicles from the cell membrane (Eitzen, 2003; Zhao et al, 2016; Jones et al, 2017; Shin et al, 2018). The large‐scale phosphoproteomic screens have identified multiple tyrosine phosphorylation sites of DYNAMIN, such as that occurring at pY80, pY125, pY354, and pY597 sites (Ballif et al, 2008; Mallozzi et al, 2013). Among them, the Y597 was a well‐studied phosphorylation site of DYNAMIN, which was previously reported to increase self‐assembly and GTP hydrolysis in both DYNAMIN1 and 2 (Kar et al, 2017). However, the Y597 of DYNAMIN was probably not the target of PTP‐MEG2 because the interaction of Y597 or A597 with PTP‐MEG2 exhibited no significant differences. However, the regulation of other tyrosine phosphorylation site, such as pY125, as well as how this particular tyrosine phosphorylation participated in a selective secretion process, has not been elucidated previously. Here, by using pharmacological approach with high selectivity, functional alanine mutagenesis according to structural characterization, combined with bioinformatics, electrochemistry and enzymology, we have demonstrated that PTP‐MEG2 negatively regulated the pY125 phosphorylation state of DYNAMIN2 during the catecholamine secretion, which promoted the cessation of the fusion pore expansion through increasing its GTPase activity.

In addition to DYNAMIN, MUNC18‐1 and its closely related subfamily members have been demonstrated to participate in several processes during vesicle secretion by interacting with SNAREs, such as docking, priming, and vesicle fusion (Fisher et al, 2001; Korteweg et al, 2005; Gulyas‐Kovacs et al, 2007; Ma et al, 2013; Cijsouw et al, 2014; Ma et al, 2015; Chai et al, 2016; He et al, 2017; Sitarska et al, 2017; Meijer et al, 2018). Importantly, the tyrosine phosphorylation of MUNC18‐1 at Y473 was recently reported as a key step in modulating vesicle priming by inhibiting synaptic transmission and preventing SNARE assembly (Meijer et al, 2018). In addition, the tyrosine phosphorylation of MUNC18‐3 on Y521 was essential for the dissociation of MUNC18‐3 and SYNTAXIN4 (Umahara et al, 2008). Moreover, the dephosphorylation of MUNC18‐1‐Y145 was suggested to be essential in maintaining the association between MUNC18‐1 and SYNTAXIN1 (Lim et al, 2013). In the present study, we demonstrated that the MUNC18‐1 Y145E phospho‐mimic mutation, but not the non‐phosphorylated mutation Y145F, significantly decreased the PSF and the SAF probability in cultured primary chromaffin cells. Notably, either the Y145E phospho‐mimic mutation or the epileptic encephalopathy associated Y145H mutant disrupted their interactions with SYNTAXIN1. Structural inspection also suggested that both phosphorylation of Y145 and Y145H mutant could destabilize the arc shape of native MUNC18‐1. Therefore, it is very likely that either the association of the MUNC18‐1 with the SYNTAXIN1 or the maintenance of the arc shape of the MUNC18‐1 actively participated in initial pore opening and expansion. Future studies by solving the fusion machinery structures encompassing the MUNC18‐1 at different stages with high resolutions, as well as more detailed fusion pore dynamics analysis using in vitro reconstitution system, could provide deeper insights for these key events in pore fusion processes. In the present study, the structural and enzymatic analysis of PTP‐MEG2 in complex with MUNC18‐1‐pY145 confirmed that PTP‐MEG2 regulated two different substrates, the MUNC18‐1‐pY145 and the DYNAMIN2‐pY125, which presented similar structural features recognized by PTP‐MEG2 and generated similar effects on fusion pore dynamics. Therefore, our studies exemplified how a PTPase regulated one important physiological process through two different substrates. This added new information of the fusion pore regulation from another aspect.

Notably, the MUNC18‐1 Y145H mutation is a known SNP that is associated with epileptic encephalopathy (Stamberger et al, 2017). Y145H behaves similarly to the MUNC18‐1 phosphorylation mimic mutant Y145E by disrupting its interaction with SYNTAXIN1 and reducing the probability of PSF elicited by AngII stimulation in primary chromaffin cells. This observation provided a clue for the pathological effects of the MUNC18‐1 Y145H mutation. In addition to MUNC18‐1, we found that VAMP7 interacted with PTP‐MEG2 via their Y45 tyrosine phosphorylation site, respectively. DYNAMIN1, PASCIN1, and SNAP25 are also potential substrates of PTP‐MEG2 depending on specific cellular contexts. The functions of VAMP7 phosphorylation at the Y45 site and its dephosphorylation by PTP‐MEG2 in the exocytosis process await further investigation.

Finally, by solving the two crystal structures of PTP‐MEG2 in complex with two substrates, the phospho‐NSF‐E79‐pY83‐K87 segment and the phospho‐MUNC18‐1‐E141‐pY145 ‐S149 segment, we revealed that PTP‐MEG2 recognized these functionally different substrates through distinct structural bases. Whereas K411, Y471, and I519 contributed most to the selective interaction of PTP‐MEG2 with NSF, another set of residues, including R409 and R410, mediated the specific binding of PTP‐MEG2 to MUNC18‐1 (Fig 8B). Most importantly, mutating Y471 and I519 to A significantly decreased the activity of PTP‐MEG2 toward the phospho‐NSF‐E79‐pY83‐K87 segment but not the phospho‐MUNC18‐1‐E141‐pY145‐S149 segment. The biochemical data lined up with the functional data that PTP‐MEG2 Y471A and I519A of PTP‐MEG2 affected the vesicle fusion procedure only but not the fusion pore opening and expansion processes. These data not only indicate that PTP‐MEG2 regulates different steps of exocytosis through different substrates in an explicit temporal and spatial context but also afforded important guidance for the design of selective PTP‐MEG2 inhibitors according to the different interfaces between PTP‐MEG2 and its substrates to explicitly regulate specific physiological processes, supporting the hypothesis of “substrate‐specific PTP inhibitors” (Doody & Bottini, 2014). The design of such inhibitors will certainly help to delineate specific roles of PTP‐MEG2 in different physiological and pathological processes.

In conclusion, we have found that PTP‐MEG2 regulates two different processes of exocytosis during catecholamine secretion, namely, vesicle fusion and the opening and extension of the fusion pore, through two different substrates with distinct structural bases. We achieved this knowledge by determining the complex structure and performing functional delineation of the protein complex interface mutants. The present study supports the hypothesis that the tyrosine phosphorylation of secretion machinery proteins is an important category of regulatory events for hormone secretion and is explicitly regulated by protein tyrosine phosphatases, such as PTP‐MEG2. Dissecting the molecular and structural mechanisms of such modulation processes will provide an in‐depth understanding of the exocytosis process and guide further therapeutic development for exocytosis‐related diseases, such as epileptic encephalopathy (Stamberger et al, 2017).

Materials and Methods

Cells and agents

The HEK293 cell lines, the 293T cell lines, and PC12 cell lines were originally obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). The HEK293 cell lines and 293T cell lines were grown in DMEM with 10% FBS (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, US) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C. PC12 cells were maintained at 37°C in DMEM containing 10% FBS (Gibco, US), 5% donor equine serum (Gibco, US), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. The information of agents and softwares is displayed in Appendix Table S6.

Constructs

Sequences of PTP‐MEG2 catalytic domain were subcloned into PET‐15b expression vector with an N‐terminal His tag or PGEX‐6P‐2 expression vector containing an N‐terminal GST tag. The mutations of PTP‐MEG2 were constructed by the QuikChange kit from Stratagene. The information of constructs and primers is detailed in Appendix Table S7.

Recombinant lentivirus construction and lentivirus infection

For recombinant lentivirus packaging, the construction and infection was carried out as previously reported (Zhang et al, 2018). Plasmids carrying different genes including pCDH‐PTP‐MEG2‐G334R/D335A/Y471A/Y471F/I519A/Q559A/ R409A/ R410A /WT‐GFP, pCDH‐MUNC18‐1‐Y145H/Y145E/Y145F/WT‐GFP, and pCDH‐DYNAMIN2‐Y125E/Y125F/WT‐GFP were transfected into 293T cells using Lipofectamine TM 2000 (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Three days after transfection, the supernatant of virus encoding PTP‐MEG2, MUNC18‐1, or DYNAMIN2 was collected and filtered. The PTP‐MEG2, MUNC18‐1, or DYNAMIN2 lentivirus (1 × 106 TU/ml) was used to infect the primary chromaffin cells in later experiments.

ELISA

Freshly isolated adrenal medullas from adult female mice (6–8 weeks) were cultured in DMEM containing 1% penicillin/streptomycin and 10% FBS. After 2 h of starvation, adrenal medullas were stimulated with high KCl (70 mM) or AngII (100 nM) for 1 min, with or without pre‐incubation of a specific PTP‐MEG2 inhibitor (400 nM) for 1 h. The supernatants were collected, and the epinephrine or norepinephrine secretion was determined by using the Epinephrine or norepinephrine ELISA kit (Shanghai Jianglai Co., Ltd, JL11194‐48T/JL13969‐96T) according to the manufacture’s protocol.

Primary chromaffin cells and animal ethics

Adrenal medullas were freshly isolated from adult female C57BL/6 mice (6–8 weeks) and placed in cold D‐Hank's buffer (PH 7.2, 109.5 nM NaCl, 23.8 nM NaHCO3, 10.0 nM D‐Glucose, 5.36 nM KCl, 17.72 nM H‐HEPE, 10.07 nM NaH2PO4, 7.28 nM Na‐HEPE). The adipose tissue was separated in cold D‐Hank's buffer. Then, the adrenal cortex was isolated and discarded. The adrenal medulla should be isolated as quickly as possible and then the medulla was cut into 4 pieces. The medulla was transferred to 1 ml Papain solution and placed in an incubator at 37°C for digestion for 10 min (the mixture should be reversed at 5 min). After that, the enzyme solution was absorbed and discarded and then changed to fresh Papain solution for further digestion for 10 min (the mixture should be reversed at 5 min). D‐Hank's buffer was added to terminate digestion. Adding 100–200 µl D‐Hank's buffer, start gently pipetting cells 20 times and then discard the supernatant (repeated 3 times). 50–100 µl D‐Hank's buffer was again added and cells were pipetted 20 times. After that, the supernatant was collected and spreaded (repeated until the precipitate disappeared) and put it into the incubator at 37°C for 30 min to resuspend the chromaffin cells. D‐Hank's buffer was then discarded and replaced with 2 ml DMEM. The relevant experimental operation was completed within 48 h. The animal experiments were approved and supervised by the Animal Ethics Committee of Shandong University (No. LL‐201602037).

Quantitative real‐time PCR

Adrenal medullas were freshly isolated from adult female mice (6–8 weeks). The lentivirus encoding wild type or mutants of PTP‐MEG2, MUNC18‐1 or DYNAMIN2 (1 × 106 TU/ml) were used to infect the primary chromaffin cells. On the third day, about 10–20 pheochromaffin cells with different brightness were selected in each plate under the fluorescence microscope and the fluorescence photographs were taken. After classification by different brightness, the cells were glued with the tips of ultra‐fine glass tubes, and the tips of glass tubes with the cells were directly broken in the PCR tube. The PCR tube was preloaded with 5 µl RNA enzyme inhibitors (Invitrogen, 10777019). 1 µl DNA scavenger was added to the PCR tube, which was left at room temperature for half an hour and then terminated with a terminator. The purpose of this step is to remove the interference of genomic DNA. All the samples were reverse‐transcribed using the Revertra Ace qPCR RT Kit (TOYOBO FSQ‐101) to obtain cDNA. Then, the quantitative real‐time PCR was performed with the LightCycler apparatus (Bio‐Rad) using the FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master (Roche). The expression of actin was used as a control. The primer sequences are detailed in Appendix Table S8.

Electrochemical amperometry

5‐μm glass carbon fiber electrode (CFE) was used to measure quantal CA released from the mouse adrenal medulla chromaffin cell as previously described (Liu et al, 2017). We used a Multiclamp 700B amplifier (2012, Axon, Molecular Devices, USA) to perform electrochemical amperometry, which interfaced to Digidata 1440A with the pClamp 10.2 software (Liu et al, 2017). The holding potential of 780 mV was used to record the amperometric current (Iamp). All experiments were performed at room temperature (20–25°C). The CFE surface was positioned in contact with the membrane of clean primary chromaffin cells to monitor the quantal release of the hormone containing catecholamine substances. In our kinetic analysis of single amperometric spike, we only used the amperometric spikes with S/N > 3 (signal/noise). The standard external solution for our amperometry measurement is as follows: 5 mM KCl, 10 mM glucose, 10 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 2 mM CaCl2, 150 mM NaCl, and 2 mM MgCl2. We analyzed all data using Igor (WaveMetrix, Lake Oswego, Oregon) and a custom‐made macro program. Statistical data were given as the mean ± s.e.m. and analyzed with one‐way ANOVA.

Electron microscopy

The female mice (6–8 weeks) were decapitated, and the adrenal medullas were freshly isolated and cut to 150‐μm‐thick sections. The sections were immersed in Ringer’s saline (125 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 26 mM NaHCO3, 10 mM D‐Glucose, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2) for 40 min at room temperature. During this period, continuous gases of 5% CO2 and 95% O2 were offered to the saline to ensure the survival of the tissue slice. After 40 min of starvation, the sections were stimulated with different conditions (control; only 100 nM AngII agonists for 1 min; only 400 nM PTP‐MEG2 inhibitor for 45 min; 100 nM AngII agonists and 400 nM PTP‐MEG2 inhibitor for 1 or 45 min) at 37°C, respectively. These sections were firstly immersed in precooled 3% glutaraldehyde and fixed at 4°C for 2 h, and then rinsed in PBS isotonic buffer, with repeated liquid exchanges and cleaning overnight, so that the samples were thoroughly rinsed and soaked in the buffer. After rinsing, the sample was fixed at 4°C with 1% osmium acid for 2 h. It was rinsed with isosmotic buffer solution at 0.1 M PBS for 15 min. The sections were dehydrated with ethanol at concentrations of 50, 70, and 90%, then ethanol at concentration of 90% and acetone at concentration of 90%, and at last only acetone at concentrations of 90 and 100%. We then replaced the acetone with the Epon gradually. The sections were added to Epon and polymerized at 60°C for 36 h. Ultra‐thin sections were performed at the thickness of 60 nm by the LKB‐1 ultra microtome, and then the ultra‐thin sections were collected with the single‐hole copper ring attached with formvar film. The sample was stained with 2% uranium acetate for 30 min and then stained with 0.5% lead citrate for 15 min. These prepared samples were examined by JEM‐1200EX electron microscope (Japan).

Western

Cells or medulla sections were lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM NaF, 1% NP‐40, 2 mM EDTA, Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 10% glycerol, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM Na3VO4, 0.3 μM aprotinin, 130 μM bestatin, 1 μM leupeptin, 1 μM pepstatin, and 0.5% IAA) after rinsing with the pre‐chilled PBS on ice. Cell and tissue lysates were kept on ice for 35 min and then sediment via centrifugation (10,800 g) for 15 min at 4°C. The whole‐cell and tissue protein lysate samples (30 μg) were prepared for SDS–PAGE. The proteins in the gel were transferred to a nitrocellulose filter membrane by electro blotting and then probed with the appropriate primary and secondary antibodies. Antibody binding was detected by an HRP system.

Immunofluorescence

For the acquisition of tissue cells used in immunofluorescence, the Wistar rats were decapitated, and the adrenal medullas were freshly isolated (female mice, 6–8 weeks). The isolated adrenal medullas were incubated in 100 nM AngII for 1 min and then immersed in 4% paraformaldehyde for fixation overnight at 4°C. Then, the fixed tissues were washed for 4 h in PBS containing 10% sucrose at 4°C for 8 h in 20% sucrose and in 30% sucrose overnight. Then, these adrenal medullas were imbedded in Tissue‐Tek OCT compound and then mounted and frozen them at −25°C. Subsequently, the adrenal medulla was cut to 4‐μm‐thick coronal serial sections. The adrenal medullas sections were blocked with 1% (vol/vol) donkey serum, 2.5% (wt/vol) BSA, and 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X‐100 in PBS for 1.5 h. Then, the slides were incubated with primary antibodies against PTP‐MEG2 (1:100), NSF (1:50), MUNC18‐1 (1:50), VAMP7 (1:50), DYNAMIN2 (1:100), SNAP25 (1:100), and PACSIN1 (1:50) at 4°C overnight. After washing with PBS for 3 times, the slides were incubated with the secondary antibody (1:500) for 1 h at room temperature. The slides were stained with DAPI (1:2,000). Images were captured using a confocal microscope (ZEISS, LSM780). Pearson’s co‐localization coefficients were analyzed with Image‐Pro Plus.

K m and k cat measurements

Enzymatic activity measurement was carried out as previously reported (Wang et al, 2014; Li et al, 2016). The standard solution (DMG buffer) for our enzymatic reactions is as follows: 50 mM 3, 3‐dimethyl glutarate pH 7.0, 1 mM EDTA, and 1 mM DTT. The ionic strength was maintained at 0.15 M (adjusted by NaCl). For the pNPP activity measurement, 100 µl reaction mixtures were set up in a total volume in a 96‐well polystyrene plate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, US). The substrate concentration ranging from 0.2 to 5 K m was used to determine the k cat and K m values. Reactions were started by the addition of an appropriate amount of His‐PTP‐MEG2‐CD‐WT or corresponding mutants, such as Y333A, G334R, D335A, Y471A, Y471F, I519A, Q559A, R409A, and R410A. The dephosphorylation of pNPP was terminated by adding 120 µl 1 M NaOH, and the enzymatic activity was monitored by measuring the absorbance at 405 nm. The activities toward phospho‐peptide segment derived from NSF or MUNC18‐1 were measured as following: In the first column, 90 μl diluted NSF/MUNC18‐1/DYNAMIN2 phospho‐peptide substrate (100 μM) was added. The successive columns were diluted by 1.5 times. The phospho‐peptide substrates were pre‐incubated at 37°C for 5 min. Reactions were started by the addition of an appropriate amount of enzymes. The dephosphorylation of NSF/MUNC18‐1/DYNAMIN2 was terminated by adding 120 µl Biomol green, and the enzymatic activities were monitored by measuring the absorbance at 620 nm. The steady‐state kinetic parameters were determined from a direct fit of the data to the Michaelis–Menten equation using GraphPad Prism 5.0.

GST pull‐down