Toxoplasma gondii and Cryptosporidium parvum, members of the phylum Apicomplexa, are significant pathogens of both humans and animals worldwide for which new and effective therapeutics are needed. Here, we describe the activity of the antibiotic boromycin against Toxoplasma and Cryptosporidium. Boromycin potently inhibited intracellular proliferation of both T. gondii and C. parvum at half-maximal effective concentrations (EC50) of 2.27 nM and 4.99 nM, respectively.

KEYWORDS: Toxoplasma gondii, Cryptosporidium parvum, boromycin, antiparasitic, drug discovery

ABSTRACT

Toxoplasma gondii and Cryptosporidium parvum, members of the phylum Apicomplexa, are significant pathogens of both humans and animals worldwide for which new and effective therapeutics are needed. Here, we describe the activity of the antibiotic boromycin against Toxoplasma and Cryptosporidium. Boromycin potently inhibited intracellular proliferation of both T. gondii and C. parvum at half-maximal effective concentrations (EC50) of 2.27 nM and 4.99 nM, respectively. Treatment of extracellular T. gondii tachyzoites with 25 nM boromycin for 30 min suppressed 84% of parasite growth, but T. gondii tachyzoite invasion into host cells was not affected by boromycin. Immunofluorescence of boromycin-treated T. gondii showed loss of morphologically intact parasites with randomly distributed surface antigens inside the parasitophorous vacuoles. Boromycin exhibited a high selectivity for the parasites over their host cells. These results suggest that boromycin is a promising new drug candidate for treating toxoplasmosis and cryptosporidiosis.

INTRODUCTION

The Apicomplexa is a large phylum of parasitic protozoa. Several of its members are causative agents of significant diseases affecting both humans and animals worldwide, such as Toxoplasma and Cryptosporidium.

Toxoplasmosis, caused by Toxoplasma gondii, is a widespread disease believed to infect 20 to 30% of the world’s population (1). Infection can be acquired through foodborne, animal-to-human, or congenital transmission and rarely through organ transplant or blood transfusion. Although usually an asymptomatic chronic infection, Toxoplasma can cause a serious condition in immunocompromised individuals, such as those with HIV/AIDS or organ transplant recipients (2). The weakened immune systems of these individuals pose significant risk for development of life-threatening toxoplasmic encephalitis. Primary infection in a pregnant woman can cause severe and disabling disease in the developing fetus (3). Studies also show that latent toxoplasmosis is associated with behavioral changes, including impaired learning (4), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (5), and schizophrenia (6). Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drugs against toxoplasmosis include the combination of sulfonamide and pyrimethamine that sequentially inhibits dihydropteroate synthase (DHPS) and dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), enzymes important for parasite survival and replication. As DHFR is also present in humans, severe hematological side effects and embryopathies can occur with this treatment combination because of folate deficiency (7). However, even after supplementation with folinic acid, side effects associated with sulfonamides and DHFR inhibitors in immunocompromised patients were still reported (2). Other current alternative therapies, such as clindamycin, spiramycin, or atovaquone, have been used with limited efficacy (8). Because of these limitations, the search for new alternative therapeutic options against toxoplasmosis is vital and a prime concern.

Cryptosporidium was identified as one of the leading pathogens causing severe diarrhea in infants and toddlers in a massive clinical and epidemiological study involving children from Africa and Asia (9). The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that 9.9% of 7.6 million yearly deaths of children younger than 5 years old were attributable to diarrhea (10). Cryptosporidiosis is a self-limiting infection of the intestinal tract in immunocompetent patients (11); however, chronic diarrhea has been consistently observed in immunocompromised people infected with Cryptosporidium, such as those with AIDS or following organ transplantation (12). Cryptosporidium parvum and Cryptosporidium hominis are the two agents that have been linked to large-scale waterborne disease outbreaks worldwide (13). C. parvum infection in cattle can also contribute to contamination of water supplies and human outbreaks (14). In a nationwide survey of dairy farms in the United States, Cryptosporidium was found to infect calves in 59% of 1,103 farms tested (15). Currently, nitazoxanide is the only FDA-approved therapy for human cryptosporidiosis, but reduced efficacy has been observed in children and nitazoxanide is of no value to immunocompromised patients (16, 17). Therefore, there is a need to explore more effective treatments against this intestinal parasite.

In this study, we describe the activity of boromycin against Toxoplasma and Cryptosporidium. Boromycin, a lipid-soluble antibiotic produced by Streptomyces antibioticus, has been shown to be active against Gram-positive bacteria, certain fungi, and protozoa but ineffective against Gram-negative bacteria (18). It is the first known antibiotic to contain boron in a lipophilic macrocyclic lactone ring which is structurally similar to tartrolon E (trtE), a recently described compound to have pan-antiapicomplexan activity (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) (19). The antibacterial action of boromycin is due to its ionophore activity with relative selectivity for K+ (18, 20) that leads to loss of membrane potential in bacteria (21). Since it was previously shown to be effective against apicomplexan parasites in the genera Eimeria (22), Plasmodium, and Babesia (23), we tested boromycin’s activity against other related apicomplexan parasites. The results of several assays demonstrated boromycin’s potent inhibitory activity against T. gondii and C. parvum with a high in vitro safety index. These results suggest that boromycin is a promising drug candidate that can be added to the therapeutic armamentarium for toxoplasmosis and cryptosporidiosis.

RESULTS

Boromycin potently inhibits intracellular proliferation of T. gondii.

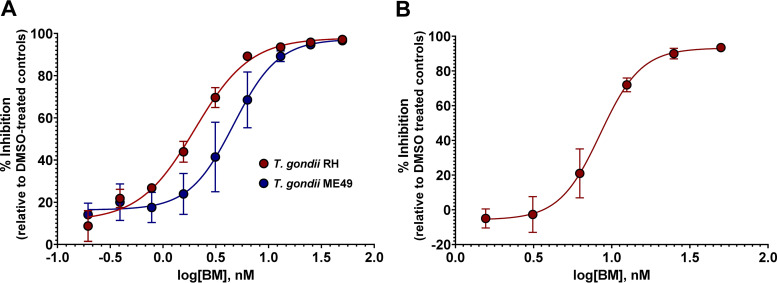

The effect of boromycin on intracellular proliferation of T. gondii in human foreskin fibroblasts (HFF) was determined using an in vitro drug inhibition assay. Boromycin dose dependently inhibited the growth of T. gondii of both type I (TgRH GFP::Luc) and type II (TgME49ΔHPT::Luc) genotypes, as indicated by a reduction in luciferase activity (Fig. 1A). The half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) of boromycin was recorded at 2.27 nM (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.92 to 2.63 nM) and 5.31 nM (95% CI, 4.2 to 6.8 nM) for TgRH GFP::Luc and TgME49ΔHPT::Luc, respectively. The two inhibitory curves are not significantly different (P = 0.2707); nevertheless, based on the EC50s, TgRH GFP::Luc is 2.3 times more susceptible to the drug than TgME49ΔHPT::Luc, which could be attributed to the differences in their growth rates (7).

FIG 1.

Boromycin displays a dose-dependent inhibitory effect against intracellular and extracellular T. gondii. (A) Parasites were allowed to infect host cells for 24 h, and then dilutions of compound were added and the incubation was continued for 24 h. Boromycin exhibits EC50s of 2.27 nM (95% CI, 1.92 to 2.63 nM) and 5.31 nM (95% CI, 4.2 to 6.8 nM) for TgRH GFP::Luc and TgME49ΔHPT::Luc, respectively. (B) Extracellular TgRH GFP::Luc tachyzoites were exposed to boromycin for 2 h, washed to remove the compound, and then allowed to infect the HFF monolayer for 24 h. Boromycin inhibited the establishment of infection in HFF after 2 h of drug exposure with an EC50 of 9.60 nM (95% CI, 8.52 to 10.86 nM). EC50s were calculated using the log(inhibitor) versus response-variable slope (four-parameter) regression equation in GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). Means ± standard deviations (SD) of results from three independent experiments consisting of three replicates per condition are shown.

Boromycin affects infectivity and recovery of extracellular T. gondii tachyzoites.

Since it was possible that boromycin was killing the parasites through an indirect effect on the host cells, the activity of boromycin against extracellular parasites was examined. Extracellular tachyzoites were exposed to serially diluted boromycin for 2 h, and then tachyzoites were washed to remove the compound. Parasites were introduced into host cells and incubated for 24 h. Even after boromycin was removed from the parasites, the ability of the tachyzoites to establish infection in host cells was inhibited with an EC50 of 9.60 nM (95% CI, 8.52 to 10.86 nM) (Fig. 1B).

Boromycin rapidly kills T. gondii.

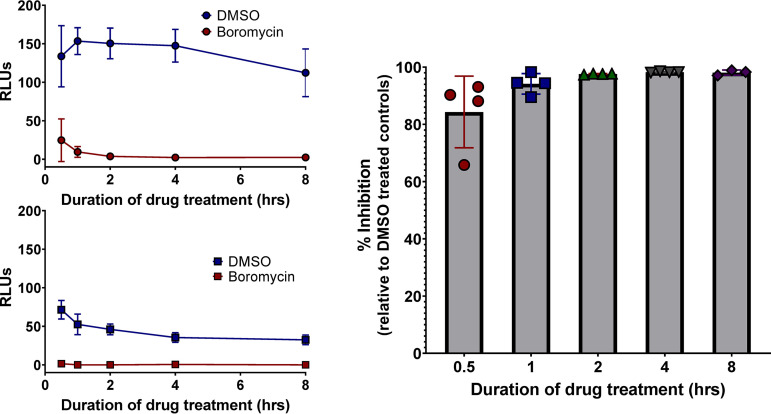

To assess how quickly boromycin affects the growth of T. gondii, TgME49ΔHPT::Luc-infected host cells were exposed to 25 nM boromycin for 0.5, 1, 2, 4, or 8 h. The compound was washed off from the infected monolayer, and parasites were allowed to grow for 72 h after drug exposure. After 30 min of boromycin exposure, parasite growth was inhibited by 84% in comparison to that of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)-treated parasites (Fig. 2A). Growth inhibition ranging from 94% to 100% was recorded in parasites exposed to boromycin for 1, 2, 4, or 8 h (Fig. 2C). To determine if extending the incubation for an additional 24 h after drug exposure would allow parasites to recover, the assay was then repeated, but growth was evaluated 96 h posttreatment. Boromycin-treated TgME49ΔHPT::Luc did not recover even after this prolonged incubation. At 96 h posttreatment, parasites exposed to DMSO began to die off because of a lack of host cells, resulting in lower luciferase readings (Fig. 2B). No recovery of parasite growth occurred even when parasites were permitted a 14-day recovery period (Fig. S2).

FIG 2.

Boromycin rapidly kills T. gondii. Proliferating TgME49ΔHPT::Luc parasites were treated with 25 nM boromycin or DMSO for 0.5, 1, 2, 4 and 8 h. (A and B) Relative luminescence (RLUs) of the parasites after 72 h and 96 h of incubation posttreatment, respectively. (C) Percent growth inhibition calculated using the results shown in panel A. Eighty-four percent of parasite growth was inhibited after 30 min of boromycin treatment. Samples were run in triplicate, and the means ± SD of results from three independent experiments (A) or two independent experiments (B) are shown.

Boromycin causes parasite swelling and disruption.

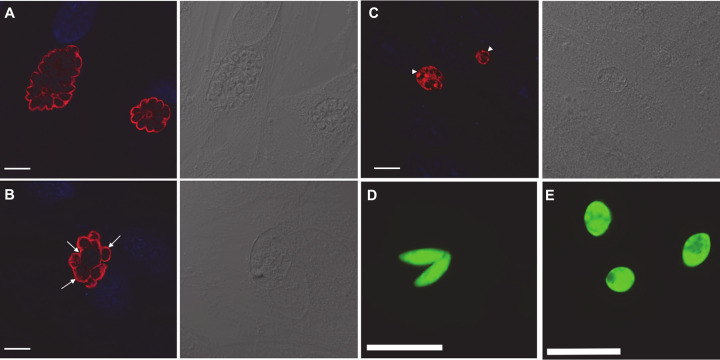

Immunofluorescence assays were performed to characterize the morphological effects of boromycin on replicating parasites. TgRH GFP::Luc-infected monolayers were treated with either 2 nM boromycin or the DMSO control 24 h postinfection. After 24 h of drug treatment, infected cells were fixed and processed for immunofluorescence assays. Confocal imaging of DMSO-treated cells revealed normal crescent-shaped tachyzoites within the parasitophorous vacuole (PV) arranged in a radial structure or “rosette” (22) (Fig. 3A). In contrast, most of the parasites exposed to 2 nM boromycin exhibited swelling and a loss of their characteristic crescent shape (Fig. 3B, arrows). When the concentration of boromycin was increased to 11 nM, more PVs with randomly distributed surface antigens were observed (Fig. 3C, arrowheads). Furthermore, cell swelling was also observed when free tachyzoites were incubated with 25 nM boromycin for 2 h (Fig. 3E) compared to the crescent-shaped tachyzoites exposed to DMSO (Fig. 3D).

FIG 3.

Morphology of intracellular and extracellular T. gondii RH strain treated with DMSO or boromycin. (A to C) Parasites were visualized with antibody against T. gondii SAG-1 (red), and nuclei are visualized with DAPI (blue). Images were captured using an SP8 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA). Differential interference contrast (DIC) images are to the right of the immunofluorescence image. (A) DMSO-treated parasites. (B) Intracellular T. gondii exposed to 2 nM boromycin. Tachyzoite swelling was observed in the majority of treated parasites (arrows). (C) Intracellular T. gondii exposed to 11 nM boromycin. Parasitophorous vacuoles containing randomly distributed surface antigens with complete loss of morphologically intact parasites (arrowheads) were commonly observed after treatment with 11 nM boromycin. (D and E) Images of GFP-expressing tachyzoites were captured using a wide-field fluorescence microscope (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA). (D) DMSO-treated tachyzoites exhibit their normal crescent shape. (E) Cell swelling was observed in extracellular tachyzoites exposed to 25 nM boromycin for 2 h. Scale bar, 10 μm.

Boromycin did not affect invasion of T. gondii tachyzoites into host cells.

Since boromycin treatment of tachyzoites inhibited the ability of the parasite to establish infection (Fig. 1B), we evaluated the drug’s effect on the parasite’s ability to invade host cells. To be successful in invading a host cell, the parasite must first attach to the host cell and then penetrate it (24, 25). Any disruption in these two aspects of the parasite invasion process leads to its inability to infect host cells. Using a high-K+ buffer that temporarily restricts motility and invasion of the parasite, we allowed free tachyzoites to make contact with the host cells first (26, 27). We then removed the high-K+ buffer, replacing it with prewarmed complete medium (CM) containing 25 nM or 50 nM boromycin, DMSO control, or high-K+ buffer as a negative control. Parasites were allowed to invade for 5 min, before fixation and antibody labeling. GFP+ SAG1+ (extracellular) and GFP+ SAG1− (intracellular) parasites were enumerated and used to calculate percent invasion.

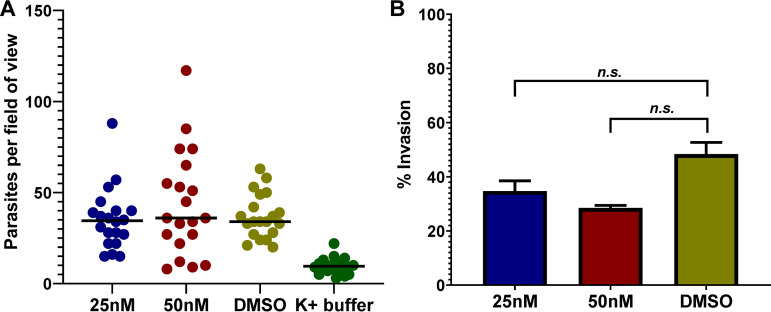

An average count of ∼35 to 44 parasites/field of view was recorded in boromycin- and DMSO-treated wells, except for the high-K+ buffer (negative control), which had an average of 10 parasites per field of view (Fig. 4A), confirming that this buffer impeded parasite motility, attachment, and invasion. Boromycin at 25 nM did not significantly inhibit parasite invasion (P = 0.5701). Even at 50 nM, boromycin reduced but did not significantly inhibit parasite invasion (P = 0.0650) (Fig. 4B).

FIG 4.

Boromycin did not significantly affect T. gondii invasion into host cells. Invasion of T. gondii tachyzoites was first synchronized by exposing the parasites to high-K+ buffer in the HFF monolayer for 20 min. High-K+ buffer was then aspirated, and parasites on the host cell surface were exposed to 25 nM, 50 nM boromycin, or DMSO in CM for 5 min before fixation. (A) Number of parasites counted in 10 randomly selected fields. (B) Percent invasion was calculated as (number of intracellular parasites/total number of parasites) × 100. A significant reduction in tachyzoite invasion of HFF was not observed with 25 nM boromycin. Increasing the concentration to 50 nM resulted in a slight, but not statistically significant, reduction in invasion compared to the DMSO control (P = 0.0650). Means ± SD of results from two independent experiments are shown.

Boromycin potently inhibits C. parvum development in vitro.

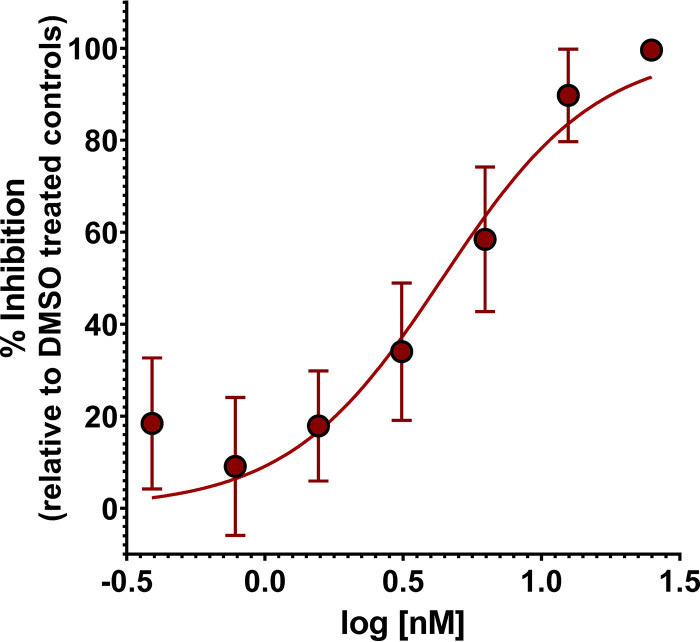

Since a related compound, tartrolon E, was found to have efficacy against multiple apicomplexan parasites (19), we investigated the in vitro activity of boromycin against C. parvum. Transgenic C. parvum Iowa strain II oocysts expressing nanoluciferase (NLuc C. parvum) were used to infect HCT-8 cells for 24 h. Twofold serial dilutions of boromycin, from 28 to 0.22 nM, were added to infected cells and incubated for 48 h. Boromycin potently inhibited C. parvum growth at nanomolar concentrations with an EC50 of 4.99 nM (95% CI, 3.77 to 6.49 nM) (Fig. 5), comparable to boromycin’s effect on T. gondii.

FIG 5.

Boromycin potently inhibits in vitro growth of C. parvum. NLuc C. parvum Iowa oocysts were used to infect HCT-8 cells for 24 h. Infected cells were treated with 2-fold serial dilutions of boromycin, and parasite growth was evaluated 48 h posttreatment. C. parvum growth was monitored by nanoluciferase activity. Boromycin exhibited an EC50 of 4.99 nM (95% CI, 3.77 to 6.49 nM) against C. parvum. Samples were run in triplicate, and the means ± SD of results from three independent experiments are shown.

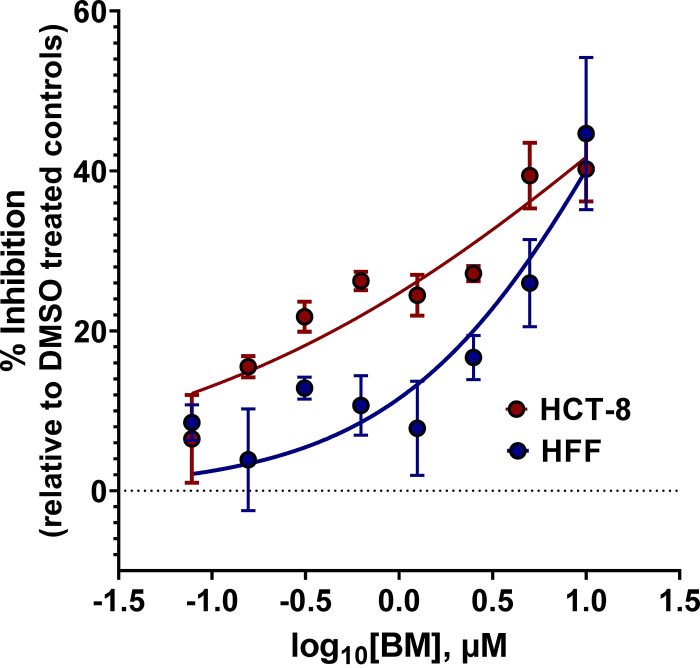

Boromycin is not toxic to host cells at antiparasitic concentrations.

To assess the cytotoxic effect of boromycin on host cells, HFF and HCT-8 cell lines were grown separately to <40% confluence in 96-well plate. Serially diluted boromycin from 11 μM to 0.089 μM was added to the host cells and incubated for 24 h, at which point host cell viability was evaluated by quantification of ATP. Luminescence readings revealed a half-maximal cytotoxic concentration (CC50) of 20.0 μM (95% CI, 13.32 to 39.30 μM) for HFF, while 27.46 μM CC50 (95% CI, 13.80 to 88.44 μM) was recorded for HCT-8 cells (Fig. 6). The selectivity index (SI) was also calculated. The SI of a compound is a widely accepted parameter used to express a compound’s in vitro efficacy in selectively inhibiting a pathogen (27). The SI of boromycin was between 3,767 and 8,812, indicating that the compound is highly selective for T. gondii and C. parvum over host cells (Table 1). When toxicity was measured 72 h posttreatment, the CC50s for HCT-8 cells and HFF decreased to 0.48 (95% CI of 0.31 to 0.71) and 5.14 μM (95% CI of 2.94 to 12.42), respectively, likely due to the accumulated effect of prolonged growth inhibition (Fig. S3). Regardless, the differential between antiparasitic activity and cell toxicity using these more conservative estimates is still significant.

FIG 6.

Boromycin is not toxic to host cells at therapeutic concentrations. Host cells used in the in vitro parasite inhibition assays (HFF, HCT-8) were grown to 40% confluence and then treated with boromycin from 11 μM to 0.089 μM. The viability of the cells was determined by quantification of ATP with a CellTiter Glo luminescent assay after 24 h of drug exposure. Boromycin’s half-maximal cytotoxic concentration (CC50) was calculated to be 20.0 μM (95% CI, 13.32 to 39.30 μM) for HFF and 27.46 μM (95% CI, 13.80 to 88.44 μM) for HCT-8 cells. Samples were run in triplicate, and the means ± SD of results from three independent experiments are shown.

TABLE 1.

EC50s, CC50s, and SIs of boromycin

| Parasite | EC50 (nM) (95% CI) | Host cell | CC50 (nM) | SIa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TgRH GFP::Luc | 2.27 (1.92–2.63) | HFF | 20,002.27 | 8,812 |

| TgME49ΔHPT::Luc | 5.31 (4.20–6.80) | HFF | 20,002.27 | 3,767 |

| nLUC C. parvum | 4.99 (3.77–6.49) | HCT-8 | 27,457.67 | 5,503 |

SI, selectivity index.

Boromycin does not induce GFP leakage in treated T. gondii tachyzoites.

To characterize the specific effect of boromycin on T. gondii, we investigated if increasing the concentration of the compound could cause immediate cell lysis of the parasites, an effect observed in boromycin-treated bacteria (21). TgRH GFP::Luc parasites were treated with high concentrations of boromycin for 1.5 to 2 h, and the release of green fluorescent protein (GFP) from tachyzoites into the supernatant was quantified. Parasites lysed using 1% Triton-X were used as a positive control. Boromycin at 100 nM did not increase the release of GFP from T. gondii, relative to the DMSO control (Fig. S4) (P > 0.9999). Increasing the concentration to 200 nM, changing the centrifugation condition, or increasing the length of drug exposure did not affect cytoplasmic protein leakage from the parasites.

DISCUSSION

Discovery of new effective drugs against human and animal parasitic protozoa is challenging yet necessary. Some of the reasons why existing therapies against T. gondii and C. parvum have limited benefits include little to no efficacy against some parasite stages (28), a marginal safety profile (29), and drugs that are ineffective in young and immunocompromised patients (17). Current strategies to speed up drug discovery and development include extending the usefulness of existing drugs by generating new formulations with various strengths or new combinations, de novo drug discovery, “piggy-back” drug discovery approaches (30), or label extension or drug repositioning (31). Drugs currently approved for another use, withdrawn because of adverse effects or not accepted for failing to prove efficacy, can still be repositioned and used for a new disease or indication (32). Repositioning or repurposing of existing drugs has already been investigated not only for malaria (33) but also for cryptosporidiosis (34), sarcocystosis (35), and toxoplasmosis (36).

In the two patents awarded for boromycin (23) and its use in the treatment and prevention of coccidiosis in poultry (22), data are provided that strongly encourage the investigation of boromycin as a potential therapeutic for toxoplasmosis and cryptosporidiosis. When given orally, boromycin was found to be highly effective against murine and avian malaria, rodent babesia (23), and avian coccidiosis (22), indicating that the compound should have in vivo efficacy against Toxoplasma and Cryptosporidium. Moreover, the inventors observed a reasonable safety margin between antiparasitic activity and toxicity in mice (23). It is unclear why boromycin was never brought to market, but in light of the recently recognized need for cryptosporidiosis treatments, this compound should be revisited.

Eimeria acervulina and Eimeria tenella, common coccidial species in the phylum Apicomplexa, cause severe and often fatal intestinal disease in chickens. Without treatment, severe forms lead to growth depression, reduced feed efficiency, and increased mortality (37). Boromycin was tested in feed premixes in different materials such as corn and soybean meals to treat poultry with active symptoms of coccidiosis as well as those without overt symptoms but that had been exposed to Eimeria species (22). Since boromycin is effective against coccidiosis in chickens and is structurally similar to the antiapicomplexan compound tartrolon E (19), we decided to examine boromycin’s activity against two other apicomplexans. Here, we described the in vitro nanomolar activity of boromycin against two related parasites, T. gondii and C. parvum. This compound has a rapid and irreversible effect on T. gondii proliferation but has no effect on parasite invasion. The high specificity of the drug for parasites, as reflected by its selectivity index, suggests that boromycin may be an effective and safe drug to treat infections caused by T. gondii and C. parvum and may potentially have an activity against other members of phylum Apicomplexa, including Plasmodium and Babesia.

Macrolide antibiotics with chemical configurations related to boromycin, having boron-borate-bridged macrodiolides (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), also reportedly exhibited anti-apicomplexan activities. Aplasmomycin, obtained from Streptomyces griseus (38), was found be active against Plasmodium in vivo. Mice experimentally infected with Plasmodium berghei were found to have significantly fewer Plasmodium-containing red blood cells after being treated with two oral doses of aplasmomycin, and all treated mice survived posttreatment (39). Likewise, tartrolon E (trtE), a compound isolated from a symbiotic bacterium of shipworms, demonstrated activity and potency comparable to that of boromycin against T. gondii and C. parvum in vitro with 3 nM and 3.85 nM EC50s, respectively (19). Subsequent experiments also revealed its nanomolar to picomolar level of activity against other apicomplexan parasites, including Babesia, Plasmodium, and Theileria (19). trtE was also effective in vivo against Cryptosporidium infection, highlighting the potential of this compound class as potential anti-apicomplexan therapeutics.

Although the mechanism of action of boromycin against these parasites has not yet been elucidated, studies of boromycin’s activity against Bacillus subtilis described its potassium complexing function (20). The ionophoric activity of boromycin against bacteria causes loss of intracellular potassium ions, leading to rapid loss of membrane potential, growth arrest, leakage of cytoplasmic proteins, and cell death (18, 21). Calcium homeostasis was also found to be influenced by boromycin in excitable and nonexcitable cells. This could be explained by the indirect interaction of boromycin with Ca2+ and Na+ transport systems via the massive efflux of K+ directly triggered by boromycin (40). In bacteria, the action of boromycin was reversed by adding excess potassium to medium blocking the action of this ionophore antibiotic (20, 21).

The anti-apicomplexan effects of boromycin observed in this study are similar to those of other ionophores, in that boromycin acts rapidly (33), it has a broad spectrum of activity (41), and it induces parasite swelling (42). Application of more advanced molecular and genetic tools revealed other molecular targets of ionophores that are distinct from the expected mechanism of membrane disruption. Monensin, aside from its function as a Na+/H+ antiporter, was found to induce some type of cellular stress and potentially DNA damage in T. gondii (43). The DNA damage initiated by monensin activates a mitochondrial homologue of MutS DNA mismatch repair enzyme (TgMSH-1), causing cell cycle arrest by an unknown mechanism, eventually leading to parasite death. As the ionophore salinomycin has a similar TgMSH-1-dependent effect on the T. gondii life cycle, it has been proposed that the DNA damage caused by monensin was a consequence of ionic disruption of the mitochondrion (43). In cancer cells, salinomycin, a highly selective potassium ionophore, has been reported to induce cell cycle arrest in differentiated cancer stem cells and to delay tumor formation in mice inoculated with breast cancer cells, making this ionophore a candidate for antitumor therapy (44). Interestingly, boromycin displayed a mechanism contrasting with that of salinomycin but the same anticancer effect. In a leukemia cell line, boromycin was observed to specifically abrogate the G2 cell cycle checkpoint induced by a DNA-damaging agent, leading to rapid cell death at nanomolar concentrations (45). Checkpoint-related kinases like ATM, Chk1, Chk2, and Wee1 were not inhibited by boromycin. This leads to an interesting idea that boromycin may inhibit a novel target different from G2 checkpoint inhibitors.

In this study, we have described the specific, rapid, and irreversible activity of boromycin against Toxoplasma and its potent effect against Cryptosporidium. These data add to the previously known antiapicomplexan activities of boromycin and might lead to an expansion of the therapeutic armamentarium for diseases caused by apicomplexans.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Parasite strains and maintenance.

The type I RH strain of Toxoplasma gondii, expressing green fluorescent protein and luciferase (TgRH GFP::Luc), was obtained from Jeroen Saeij, University of California Davis, and the type II ME49 strain of T. gondii (TgME49ΔHPT::Luc) was obtained from Laura Knoll of the University of Wisconsin. Parasites were maintained in human foreskin fibroblasts (HFF; ATCC SCRC-1041TM) grown in complete medium (CM; Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum [FBS], 25 mM HEPES, 2× l-glutamine, 10,000 IU/ml of penicillin, and 10 mg/ml streptomycin). Parasites were harvested and passaged as previously described (46). Cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2.

Transgenic Cryptosporidium parvum Iowa strain II oocysts expressing nanoluciferase (NLuc C. parvum) (46) were obtained from the Sterling Parasitology Laboratory at the University of Arizona in Tucson. Oocysts were stored at 4°C or maintained on ice at all times to reduce unintended excystation. Oocysts were used within 3 months to ensure maximum viability, since after 3 months of storage, infection rates decrease rapidly. The host cells used for evaluating NLuc C. parvum infection were human ileocecal colorectal adenocarcinoma cells (HCT-8 cells; ATCC CCL244). HCT-8 cells were maintained in CM-R (RPMI 1640 with l-glutamine [Corning, NY] supplemented with 10% FBS and penicillin/streptomycin [Sigma-Aldrich, MO]). Subcultures were performed according to the manufacturer’s recommended procedure. HCT-8 cells were maintained for less than 30 passages.

Compounds.

A stock solution (1 mg/ml) of boromycin (AdipoGen, San Diego, CA) was prepared in 100% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), aliquoted, and kept at −80°C.

In vitro drug inhibition assay for T. gondii.

HFF were seeded onto white 96-well clear-bottom plates. Plates were incubated at 37°C under 5% CO2 until monolayers reached 100% confluence. Cells were then infected with 5.0 × 105/ml of TgRH GFP::Luc or 1.0 × 106/ml of TgME49ΔHPT::Luc per well. At 24 h postinfection, 2-fold serial dilutions of boromycin from 57 to 0.22 nM were made in a separate plate. Thereafter, 100 μl of each drug concentration was transferred to each T. gondii-infected well. DMSO (0.1%) was used as a negative control. Parasite viability was measured after 24 h of treatment using Bright-Glo luciferase reagent (Promega, Madison WI). A Synergy HTX multimode microplate reader (BioTek, USA) recorded the relative luminescence units (RLU) in each well. The RLU value of cells only (RLUcells only) was used to obtain background and was subtracted from RLUDMSO and RLUtreatment values. The percent of growth inhibition was calculated from the luminescence values relative to the negative control by the following formula: % inhibition = [(RLUDMSO − RLUtreatment)/RLUDMSO] × 100. Samples were run in triplicate, and three independent assays were performed. Data are expressed as the means ± standard deviation (SD). Half-maximal effective concentrations (EC50s) of boromycin and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were extrapolated using the log(inhibitor) versus response-variable slope (four-parameter) regression equation in GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). Inhibition curves were compared using the extra sum-of-squares F test, while EC50s were compared using a Student's t test.

Pretreatment assay.

To evaluate the effect of boromycin on extracellular T. gondii, tachyzoites were harvested from two T25 flasks infected with TgRH GFP::Luc. Old medium and dead or dying tachyzoites were removed, and then the infected monolayers were scraped into fresh CM before being lysed with a syringe three times to release the tachyzoites. A 400-μl volume of tachyzoite suspension was distributed in each well of a 24-well plate, and then 400 μl of 2-fold serial dilutions of boromycin from 57 to 1.8 nM concentration was added to the parasites. The plate was then incubated for 2 h at 37°C under 5% CO2. The contents of each well were then transferred into an Eppendorf tube and centrifuged at 600 × g for 5 min. Supernatant was aspirated, and the pellet was resuspended in CM. The centrifugation and washing processes were repeated three times to remove the compound from the parasites. Parasites were resuspended in 400 μl of fresh medium, and 100 μl of parasite suspension was introduced into confluent HFF monolayers in white 96-well clear-bottom plates. Parasites were allowed to infect and proliferate in the monolayer for 24 h. Parasite proliferation was measured by luminescence detection as described above. Percent inhibition and half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) values were determined as described above.

Time-to-kill assay.

Confluent monolayers of HFF in white 96-well clear-bottom plates were infected with 5.0 × 105/ml of TgME49ΔHPT::Luc/well. After 24 h of infection, infected cells were exposed to 25 nM boromycin for 0.5, 1, 2, 4, or 8 h. DMSO-treated parasites were run in parallel at each time point. CM was used to wash the monolayer three times to remove the compound at every time point. Wells were reconstituted with fresh CM and incubated for another 72 h or 96 h after compound removal. Parasites were assayed by the same procedure used for the in vitro drug inhibition assay to assess the ability of T. gondii to recover from treatments. Three independent assays were performed with a 72-h post-drug-removal incubation, while two independent experiments were conducted with a 96-h post-drug-removal incubation. To verify that the boromycin kills parasites, one experiment was conducted in which parasites were allowed to recover for up to 14 days postinfection. Samples were run in triplicate. Data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and differences were determined by Dunnett’s multiple-comparison posttest.

Immunofluorescence of T. gondii treated with boromycin.

For immunofluorescence assays, an 8-well chamber slide was seeded with HFF and then incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2. Once the monolayers reached at least 90% confluence, the cells were infected with TgRH GFP::Luc parasites. At 24 h postinfection, wells were treated with 2 nM or 11 nM boromycin. DMSO was run in parallel as a vehicle control. Cells were fixed 24 h posttreatment with 2% paraformaldehyde, 3% glutaraldehyde, and 0.1 M phosphate buffer for 20 min at 4°C. Wells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) three times. To avoid nonspecific binding of the primary antibody, 400 μl of 2% bovine serum albumin in PBS (BSA-PBS) was added to each well, and slides were incubated at 4°C overnight or for 1 h at room temperature. Rabbit polyclonal antibody against the immunodominant surface antigen of Toxoplasma, SAG-1, was used as the primary antibody. Rabbit anti-SAG1 was detected with Alexa Fluor 594-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen, CA). The slides were prepared for visualization by mounting them in 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI)-containing Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Samples were examined, and images were obtained using a Leica SP8 Lightning confocal laser microscope (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA).

Synchronous invasion assay.

To assess the effect of boromycin on tachyzoite invasion, TgRH GFP::Luc parasites were harvested and released from their host cells by passing them three times through a 25-gauge syringe needle. The parasite suspension was centrifuged in a 15-ml conical tube at 700 × g for 10 min. After the medium was aspirated from the tube, the parasites were resuspended in a high-potassium-based buffer containing 44.7 mM K2SO4, 10 mM MgSO4, 106 mM sucrose, 5 mM glucose, 20 mM Tris-H2SO4 (pH 8.2), and 3.5 mg/ml BSA (26). Tachyzoites (5 × 106/well) were then introduced into each well of a chambered slide containing confluent HFF. Slides were incubated for 20 min at 37°C to allow tachyzoites to adhere to the monolayer. The high-K+ buffer was gently aspirated and replaced with 400 μl of prewarmed CM containing either 25 nM boromycin, 50 nM boromycin, 0.1% DMSO, or high-K+ buffer, the latter two serving as controls. The slide was incubated at 37°C for 5 min and then subsequently fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at 4°C. Blocking and staining protocols were the same as for the immunofluorescence assay described above. Ten fields per treatment were randomly selected, and intracellular and extracellular parasites were enumerated. Parasites were identified as extracellular if they were GFP positive and stained with anti-SAG-1 antibody (GFP+ SAG1+) or intracellular if GFP was only detected (GFP+ SAG1−). Percent invasion was calculated by dividing the number of intracellular parasites by the total number of parasites counted. Results were analyzed by one-way ANOVA and the Kruskal-Wallis multiple-comparison test for nonparametric data.

In vitro drug inhibition assay for C. parvum.

Nanoluciferase-expressing C. parvum Iowa strain (NLuc C. parvum) was used to infect HCT-8 monolayers. HCT-8 cells were seeded and grown to 90% confluence in white 96-well clear-bottom plates. NLuc C. parvum oocysts were pretreated with 10% bleach solution for 10 min at room temperature and then centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 6 min. After the bleach solution was aspirated, the pellets were then resuspended with 1 ml of PBS and centrifuged again at 14,000 × g for 6 min to wash the oocysts. CM-R plus 0.6% taurocholate was used to resuspend the pellet. Oocysts were introduced into the host cells, and then the plates were centrifuged for 5 min at 1,000 × g to allow oocysts to contact cell monolayers, facilitating invasion of sporozoites. At 24 h postinfection, infected cells were treated with 2-fold serially diluted boromycin, from 28 to 0.22 nM. DMSO at 0.1% was run in parallel as a vehicle control.

After 48 h of infection, the plates were centrifuged for 5 min at 1,000 × g before the medium was aspirated using an Integra Viaflo 96 handheld channel pipette (Integra, NH, USA). Cells were lysed by adding 50 μl of fecal lysis buffer (FLB) consisting of 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM dithiothreitol, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), and 2 mM EDTA. The plates were again centrifuged at 92 rpm for 1 h, after which 50 μl of Nano-Glo luciferase reagent (Promega, Madison, WI) was added per well and luminescence signals were quantified as previously described. The EC50 was determined as described for T. gondii above. Samples were run in triplicate, and three independent assays were conducted. The inhibition curve and the EC50 were calculated as described above.

Cytotoxicity assay.

To assess the toxicity of boromycin for host cells, the ATP present in the metabolically active cells was quantified by the CellTiter-Glo luminescent cell viability assay (Promega, Madison WI) after drug treatment. Ninety-six-well plates were seeded with 5.0 × 104 cells/ml for HFF or 1.5 × 105 cells/ml for HCT-8 cells, and then cells were incubated for 24 h to attain 30 to 40% confluence. Boromycin was added to cells at concentrations starting at 11 μM diluted down to 0.089 μM. DMSO controls were run in parallel. Cells were incubated with the compound for 24 h or 72 h, and viability was determined using CellTiter-Glo reagent by following the manufacturer’s directions. Control wells containing medium without cells were also prepared to obtain RLU measurements for background subtraction. Cytotoxicity was calculated by the following formula: % cytotoxicity = [(RLUDMSO − RLUtreatment)/RLUDMSO] × 100. The cytotoxicity at which 50% of the cells were killed (CC50) was determined using a log(inhibitor) versus response-variable slope (four-parameter) regression equation in GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). The selectivity indices (SI) of boromycin were calculated as the ratio between cytotoxic activity (CC50) to host cells and antiparasitic activities (EC50) to T. gondii and C. parvum according to the following formula: SI = CC50(HFF; HCT-8)/EC50(T. gondii; C. parvum).

GFP leakage assay.

To assess if boromycin causes cell lysis of T. gondii tachyzoites, TgRH GFP::Luc was used. Tachyzoites were harvested from three (3) infected T25 flasks and treated with 100 nM and 200 nM boromycin diluted in Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS). For a positive control, tachyzoites were treated with 1% Triton X-100. DMSO at the same dilution as boromycin was used as a negative control. After 1.5 or 2 h of incubation with the drug at room temperature, tachyzoites were centrifuged at 4,000 × g or 16,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Supernatants were collected and transferred to a 96-well black, optically clear-bottom plate. GFP fluorescence was quantified using a Synergy HTX multimode microplate reader (BioTek, USA) with excitation at 485 nm (λmax) and emission at 528 nm (λmax). The fluorescence emission of HBSS and 1% Triton X-100 were used to calculate background fluorescence. Samples were analyzed by one-way ANOVA, and differences were determined by Dunnett’s multiple-comparison posttest.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by grant no. R21AT009174 from the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Complimentary and Integrated Health, to R.O. J.A. was supported by a scholarship provided by Fulbright Philippines and the Commission on Higher Education (CHED).

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Montoya JG, Liesenfeld O. 2004. Toxoplasmosis. Lancet 363:1965–1976. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16412-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luft BJ, Remington JS. 1992. Toxoplasmic encephalitis in AIDS. Clin Infect Dis 15:211–222. doi: 10.1093/clinids/15.2.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McAuley JB. 2014. Congenital toxoplasmosis. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 3(Suppl 1):S30–S35. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piu077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Piekarski G. 1981. Behavioral alterations caused by parasitic infection in case of latent toxoplasma infection. Zentralbl Bakteriol Mikrobiol Hyg A 250:403–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miman O, Mutlu EA, Ozcan O, Atambay M, Karlidag R, Unal S. 2010. Is there any role of Toxoplasma gondii in the etiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder? Psychiatry Res 177:263–265. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flegr J. 2013. How and why Toxoplasma makes us crazy. Trends Parasitol 29:156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meneceur P, Bouldouyre MA, Aubert D, Villena I, Menotti J, Sauvage V, Garin JF, Derouin F. 2008. In vitro susceptibility of various genotypic strains of Toxoplasma gondii to pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine, and atovaquone. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52:1269–1277. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01203-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alomar ML, Rasse-Suriani FA, Ganuza A, Coceres VM, Cabrerizo FM, Angel SO. 2013. In vitro evaluation of beta-carboline alkaloids as potential anti-Toxoplasma agents. BMC Res Notes 6:193. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-6-193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kotloff KL, Nataro JP, Blackwelder WC, Nasrin D, Farag TH, Panchalingam S, Wu Y, Sow SO, Sur D, Breiman RF, Faruque AS, Zaidi AK, Saha D, Alonso PL, Tamboura B, Sanogo D, Onwuchekwa U, Manna B, Ramamurthy T, Kanungo S, Ochieng JB, Omore R, Oundo JO, Hossain A, Das SK, Ahmed S, Qureshi S, Quadri F, Adegbola RA, Antonio M, Hossain MJ, Akinsola A, Mandomando I, Nhampossa T, Acacio S, Biswas K, O'Reilly CE, Mintz ED, Berkeley LY, Muhsen K, Sommerfelt H, Robins-Browne RM, Levine MM. 2013. Burden and aetiology of diarrhoeal disease in infants and young children in developing countries (the Global Enteric Multicenter Study, GEMS): a prospective, case-control study. Lancet 382:209–222. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60844-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu L, Johnson HL, Cousens S, Perin J, Scott S, Lawn JE, Rudan I, Campbell H, Cibulskis R, Li M, Mathers C, Black RE, Child Health Epidemiology Reference Group of WHO and UNICEF. 2012. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality: an updated systematic analysis for 2010 with time trends since 2000. Lancet 379:2151–2161. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60560-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chalmers RM, Davies AP. 2010. Minireview: clinical cryptosporidiosis. Exp Parasitol 124:138–146. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Navin TR, Weber R, Vugia DJ, Rimland D, Roberts JM, Addiss DG, Visvesvara GS, Wahlquist SP, Hogan SE, Gallagher LE, Juranek DD, Schwartz DA, Wilcox CM, Stewart JM, Thompson SE, III, Bryan RT. 1999. Declining CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts are associated with increased risk of enteric parasitosis and chronic diarrhea: results of a 3-year longitudinal study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol 20:154–159. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199902010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Striepen B. 2013. Parasitic infections: time to tackle cryptosporidiosis. Nature 503:189–191. doi: 10.1038/503189a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacKenzie WR, Schell WL, Blair KA, Addiss DG, Peterson DE, Hoxie NJ, Kazmierczak JJ, Davis JP. 1995. Massive outbreak of waterborne cryptosporidium infection in Milwaukee, Wisconsin: recurrence of illness and risk of secondary transmission. Clin Infect Dis 21:57–62. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garber LP, Salman MD, Hurd HS, Keefe T, Schlater JL. 1994. Potential risk factors for Cryptosporidium infection in dairy calves. J Am Vet Med Assoc 205:86–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abubakar I, Aliyu SH, Arumugam C, Hunter PR, Usman NK. 2007. Prevention and treatment of cryptosporidiosis in immunocompromised patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1:CD004932. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004932.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amadi B, Mwiya M, Musuku J, Watuka A, Sianongo S, Ayoub A, Kelly P. 2002. Effect of nitazoxanide on morbidity and mortality in Zambian children with cryptosporidiosis: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 360:1375–1380. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11401-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hutter R, Keller-Schierlein W, Knusel F, Prelog V, Rodgers GC, Jr, Suter P, Vogel G, Voser W, Zahner H. 1967. The metabolic products of microorganisms. Boromycin. Helv Chim Acta 50:1533–1539. doi: 10.1002/hlca.19670500612. (In German.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Connor RM, Nepveux VF, Abenoja J, Bowden G, Reis P, Beaushaw J, Bone Relat RM, Driskell I, Gimenez F, Riggs MW, Schaefer DA, Schmidt EW, Lin Z, Distel DL, Clardy J, Ramadhar TR, Allred DR, Fritz HM, Rathod P, Chery L, White J. 2020. A symbiotic bacterium of shipworms produces a compound with broad spectrum anti-apicomplexan activity. PLoS Pathog 16:e1008600. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pache W, Zahner H. 1969. Metabolic products of microorganisms. 77. Studies on the mechanism of action of boromycin. Arch Mikrobiol 67:156–165. doi: 10.1007/BF00409681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moreira W, Aziz DB, Dick T. 2016. Boromycin kills mycobacterial persisters without detectable resistance. Front Microbiol 7:199. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller MB, Burg RW. 1975. Boromycin as a coccidiostat. U.S. Patent 3864479.

- 23.Prelog V, Zaehner H, Bickel H. 1973. Antibiotic A 28829. U.S. Patent 3,769,418.

- 24.Hall CI, Reese ML, Weerapana E, Child MA, Bowyer PW, Albrow VE, Haraldsen JD, Phillips MR, Sandoval ED, Ward GE, Cravatt BF, Boothroyd JC, Bogyo M. 2011. Chemical genetic screen identifies Toxoplasma DJ-1 as a regulator of parasite secretion, attachment, and invasion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:10568–10573. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105622108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carey KL, Westwood NJ, Mitchison TJ, Ward GE. 2004. A small-molecule approach to studying invasive mechanisms of Toxoplasma gondii. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:7433–7438. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307769101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kafsack BF, Beckers C, Carruthers VB. 2004. Synchronous invasion of host cells by Toxoplasma gondii. Mol Biochem Parasitol 136:309–311. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sweeney KR, Morrissette NS, LaChapelle S, Blader IJ. 2010. Host cell invasion by Toxoplasma gondii is temporally regulated by the host microtubule cytoskeleton. Eukaryot Cell 9:1680–1689. doi: 10.1128/EC.00079-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anonymous. 2020. Human toxoplasma infection, p 117–227. In Weiss L, Kim K (ed), Toxoplasma gondii, 3rd ed. Elsevier, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Howes RE, Piel FB, Patil AP, Nyangiri OA, Gething PW, Dewi M, Hogg MM, Battle KE, Padilla CD, Baird JK, Hay SI. 2012. G6PD deficiency prevalence and estimates of affected populations in malaria endemic countries: a geostatistical model-based map. PLoS Med 9:e1001339. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nwaka S, Hudson A. 2006. Innovative lead discovery strategies for tropical diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov 5:941–955. doi: 10.1038/nrd2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andrews KT, Fisher G, Skinner-Adams TS. 2014. Drug repurposing and human parasitic protozoan diseases. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist 4:95–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Naveja JJ, Dueñas-González A, Medina-Franco JL. 2016. Drug repurposing for epigenetic targets guided by computational methods, p 327–357. In Medina-Franco J (ed), Epi-informatics. Elsevier, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 33.D'Alessandro S, Corbett Y, Ilboudo DP, Misiano P, Dahiya N, Abay SM, Habluetzel A, Grande R, Gismondo MR, Dechering KJ, Koolen KM, Sauerwein RW, Taramelli D, Basilico N, Parapini S. 2015. Salinomycin and other ionophores as a new class of antimalarial drugs with transmission-blocking activity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:5135–5144. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04332-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lunde CS, Stebbins EE, Jumani RS, Hasan MM, Miller P, Barlow J, Freund YR, Berry P, Stefanakis R, Gut J, Rosenthal PJ, Love MS, McNamara CW, Easom E, Plattner JJ, Jacobs RT, Huston CD. 2019. Identification of a potent benzoxaborole drug candidate for treating cryptosporidiosis. Nat Commun 10:2816. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10687-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bowden GD, Land KM, O'Connor RM, Fritz HM. 2018. High-throughput screen of drug repurposing library identifies inhibitors of Sarcocystis neurona growth. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist 8:137–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2018.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dittmar AJ, Drozda AA, Blader IJ. 2016. Drug repurposing screening identifies novel compounds that effectively inhibit Toxoplasma gondii growth. mSphere 1:e00042-15. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00042-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peek HW, Landman WJ. 2011. Coccidiosis in poultry: anticoccidial products, vaccines and other prevention strategies. Vet Q 31:143–161. doi: 10.1080/01652176.2011.605247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakamura H, Iitaka Y, Kitahara T, Okazaki T, Okami Y. 1977. Structure of aplasmomycin. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 30:714–719. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.30.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Okami Y, Okazaki T, Kitahara T, Umezawa H. 1976. Studies on marine microorganisms. V. A new antibiotic, aplasmomycin, produced by a streptomycete isolated from shallow sea mud. J Antibiot 29:1019–1025. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.29.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lakatos B, Kaiserova K, Simkovic M, Orlicky J, Knezl V, Varecka L. 2002. The effect of boromycin on the Ca2+ homeostasis. Mol Cell Biochem 231:15–22. doi: 10.1023/a:1014428713997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rajendran V, Ilamathi HS, Dutt S, Lakshminarayana TS, Ghosh PC. 2018. Chemotherapeutic potential of monensin as an anti-microbial agent. Curr Top Med Chem 18:1976–1986. doi: 10.2174/1568026619666181129141151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Couzinet S, Dubremetz JF, Buzoni-Gatel D, Jeminet G, Prensier G. 2000. In vitro activity of the polyether ionophorous antibiotic monensin against the cyst form of Toxoplasma gondii. Parasitology 121:359–365. doi: 10.1017/S0031182099006605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lavine MD, Arrizabalaga G. 2011. The antibiotic monensin causes cell cycle disruption of Toxoplasma gondii mediated through the DNA repair enzyme TgMSH-1. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:745–755. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01092-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gupta PB, Onder TT, Jiang G, Tao K, Kuperwasser C, Weinberg RA, Lander ES. 2009. Identification of selective inhibitors of cancer stem cells by high-throughput screening. Cell 138:645–659. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arai M, Koizumi Y, Sato H, Kawabe T, Suganuma M, Kobayashi H, Tomoda H, Omura S. 2004. Boromycin abrogates bleomycin-induced G2 checkpoint. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 57:662–668. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.57.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vinayak S, Pawlowic MC, Sateriale A, Brooks CF, Studstill CJ, Bar-Peled Y, Cipriano MJ, Striepen B. 2015. Genetic modification of the diarrhoeal pathogen Cryptosporidium parvum. Nature 523:477–480. doi: 10.1038/nature14651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.