Abstract

Background:

Influenza may contribute to the burden of acute cardiovascular events during annual influenza epidemics.

Objective:

To examine acute cardiovascular events and determine risk factors for acute heart failure (aHF) and acute ischemic heart disease (aIHD) in adults with a hospitalization associated with laboratory-confirmed influenza.

Design:

Cross-sectional study.

Setting:

U.S. Influenza Hospitalization Surveillance Network during the 2010-to-2011 through 2017-to-2018 influenza seasons.

Participants:

Adults hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed influenza and identified through influenza testing ordered by a practitioner.

Measurements:

Acute cardiovascular events were ascertained using discharge codes from the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification, and ICD, 10th Revision. Age, sex, race/ethnicity, tobacco use, chronic conditions, influenza vaccination, influenza antiviral medication, and influenza type or subtype were included as exposures in logistic regression models, and marginal adjusted risk ratios and 95% CIs were estimated to describe factors associated with aHF or aIHD.

Results:

Among 89 999 adults with laboratory-confirmed influenza, 80 261 had complete medical record abstractions and available ICD codes (median age, 69 years [interquartile range, 54 to 81 years]) and 11.7% had an acute cardiovascular event. The most common such events (non-mutually exclusive) were aHF (6.2%) and aIHD (5.7%). Older age, tobacco use, underlying cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and renal disease were significantly associated with higher risk for aHF and aIHD in adults hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed influenza.

Limitation:

Underdetection of cases was likely because influenza testing was based on practitioner orders. Acute cardiovascular events were identified by ICD discharge codes and may be subject to misclassification bias.

Conclusion:

In this population-based study of adults hospitalized with influenza, almost 12% of patients had an acute cardiovascular event. Clinicians should ensure high rates of influenza vaccination, especially in those with underlying chronic conditions, to protect against acute cardiovascular events associated with influenza.

Primary Funding Source:

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death and health care expenditure in the United States (1). Acute infections (2, 3), specifically influenza virus infections (4-8), have been a clinically underrecognized contributor to the burden of cardiovascular disease. Annual influenza epidemics in the United States result in 140 000 to 810 000 hospitalizations and 12 000 to 61 000 deaths each year (9). Although respiratory disease is a hallmark of influenza virus infection, cardiovascular events are also important complications of influenza (8, 10).

A relationship between influenza virus infection and cardiovascular disease has been demonstrated through strong temporal associations between syndromic influenza activity and cardiovascular mortality (8, 11-15). In a recent study using laboratory-confirmed influenza, rates of acute myocardial infarction were higher in the 7 days after a positive result on an influenza test than in control time intervals (4). In addition, influenza may exacerbate other types of chronic cardiovascular conditions, such as heart failure, or contribute to acute cardiovascular events, including acute myocarditis (5, 16, 17), acute pericarditis (18, 19), and cardiac tamponade (20, 21). However, few population-based studies have estimated the frequency of acute cardiovascular events associated with influenza.

In this study, we describe the spectrum of acute cardiovascular events among adults hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed influenza between 2010 and 2018 using data from the U.S. Influenza Hospitalization Surveillance Network (FluSurv-NET). We also assess factors associated with risk for acute heart failure (aHF) and acute ischemic heart disease (aIHD).

Methods

Study Design, Setting, and Participants

Our study is a cross-sectional analysis of data from FluSurv-NET, a large, multicenter, U.S. network that is sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and conducts population-based surveillance for hospitalizations associated with laboratory-confirmed influenza (22). The network was established in 2003 through a partnership among the CDC, state and local health departments, and academic institutions. Data from FluSurv-NET are used to generate age-stratified hospitalization rates (23) and national estimates of influenza disease burden (24, 25). This analysis includes adult patients aged 18 years or older who were hospitalized in the FluSurv-NET catchment area between 1 October and 30 April during the 2010-to-2011 through 2017-to-2018 influenza seasons. During this time, the FluSurv-NET catchment area (covering 9% of the U.S. population) included selected counties in California, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, New Mexico, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Tennessee, and Utah. Additional counties in Idaho (2010 to 2011), Iowa (2012 to 2013), Oklahoma (2010 to 2011), and Rhode Island (2010 to 2013) also contributed to the network.

The CDC determined that this surveillance project was not human subjects research; therefore, approval by the CDC's institutional review board was not required. Data were deidentified before delivery to the CDC. Each participating site submitted the FluSurv-NET protocol to their state and local institutional review boards for review as appropriate. In the preparation of this manuscript, we adhered to the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) reporting guidelines.

Variables, Data Sources, and Measurements

We defined laboratory-confirmed influenza as a positive test result within 14 days before or 3 days after hospital admission by rapid antigen assay, reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction, direct or indirect fluorescent staining, or viral culture. From medical records, trained surveillance officers abstracted patient demographic characteristics; underlying medical conditions; antiviral use; influenza vaccination status for the current season (vaccinated at least 2 weeks before hospital admission); discharge diagnoses and outcomes, including length of hospital stay; intensive care unit admission; mechanical ventilatory support; extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; and in-hospital death. We described the timing of earliest antiviral treatment with relation to hospital admission date. We defined early treatment as beginning antiviral therapy 2 days before through up to 1 day after hospital admission and late treatment as beginning antiviral therapy after 1 day of hospitalization. Data were not available to determine timing of treatment relative to the acute cardiovascular event.

We identified and classified acute cardiovascular events using primary and secondary discharge diagnostic codes from the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification, and ICD, 10th Revision (up to 9 codes were abstracted for each FluSurv-NET patient) (Appendix Table 1, available at Annals.org). We restricted ICD codes to those that used the terms acute, acute-on-chronic, or exacerbation to better capture acute events. We also included diagnoses that are not known to be chronic conditions, including cardiac tamponade, cardiogenic shock, and hypertensive crisis. We excluded diagnoses for which we could not distinguish between acute and chronic conditions by ICD discharge codes alone, such as atrial fibrillation and other cardiac arrhythmias. We classified the acute cardiovascular events into the following 7 groups: acute myocarditis, acute pericarditis, aHF, aIHD, cardiac tamponade, cardiogenic shock, and hypertensive crisis. Consistent with proposed changes to ICD, 11th Revision, we classified cerebrovascular accidents and hemorrhages as neurologic diagnoses rather than acute cardiovascular events (26, 27).

Between the 2010-to-2011 and 2016-to-2017 influenza seasons, surveillance officers abstracted complete medical record data for all patients with laboratory-confirmed influenza identified in the FluSurv-NET catchment area. During the 2017-to-2018 influenza season, surveillance officers collected a minimum set of variables for all patients but implemented a sampling scheme for complete medical record abstraction for patients aged 50 years or older. Random numbers were autogenerated and assigned to each case as soon as a case identification number was entered into the database; random samples of cases, stratified by age group and surveillance site, were drawn using these random numbers. Individual surveillance sites were given the option to abstract complete medical record information from 25%, 50%, or 100% random samples of patients aged 65 years or older and 50% or 100% random samples of patients aged 50 to 64 years. Of the 14 surveillance sites in 2017 to 2018, 7 opted to review medical records on all identified cases and 7 implemented a sampling strategy. Complete medical record abstractions were done for all patients younger than 50 years and all patients of any age who died during their hospitalization (28). Among surveillance sites that chose to sample case report forms during the 2017-to-2018 season, the distribution of sampled versus nonsampled cases was even across facilities, showing that sampled cases were representative of the FluSurv-NET catchment area (data not shown).

Statistical Analysis

We used survey procedures in SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute), to appropriately weight data to reflect the probability of sampling for complete medical record abstraction for patients aged 50 years or older. Sample sizes are listed as unweighted numbers, whereas percentages, medians, and interquartile ranges are reported as weighted values. We described the frequency of demographic and clinical characteristics for patients with and without any acute cardiovascular event.

Influenza A subtype was not reported for 52% of patients with influenza A virus infection. We used multiple imputation (70 imputations) to estimate missing values of influenza A subtype using patient age, surveillance site, and admission month in the imputation model. Patients were excluded from the imputation analysis if influenza type could not be distinguished between influenza A and B or if they were co-infected with A(H1N1)pdm09 and A(H3N2). We analyzed each of the 70 imputed data sets using logistic regression models for aHF and aIHD and pooled the estimates using the built-in option in SAS-Callable SUDAAN for analyzing multiply imputed data in regression procedures.

We used bivariate and multivariable logistic regression models to estimate the adjusted prevalence, or marginal predicted probabilities, of aHF and aIHD as 2 separate outcomes and to identify risk factors for these outcomes using marginal standardization (29). Our final models included season, surveillance site, age, sex, race/ethnicity, body mass index (BMI), tobacco use history, chronic medical conditions (including atrial fibrillation, chronic heart failure or cardiomyopathy, coronary artery disease, diabetes, and chronic renal disease), influenza vaccination status for the current season, antiviral therapy, and influenza type or subtype. For our final analysis, we excluded patients who began influenza antiviral therapy more than 2 days before hospital admission, those who were missing information for BMI or vaccination status, and those for whom influenza subtype imputation was not done. We included antiviral therapy to adjust for possible confounding but could not assess effectiveness because the timing of therapy relative to the cardiovascular outcomes was unknown. We identified collinearity between chronic respiratory condition and tobacco use history; we chose to include tobacco use history in place of chronic respiratory condition in the final model. For each model, our comparison group consisted of patients who had no acute cardiovascular events.

For all of our data analyses, we used SAS software or SAS-Callable SUDAAN software, version 9.4, to account for the complex survey design and to conduct marginal standardization.

Role of the Funding Source

The CDC designed and conducted the study; received, managed, analyzed, and interpreted the data; prepared, reviewed, and approved the manuscript; and had a role in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Results

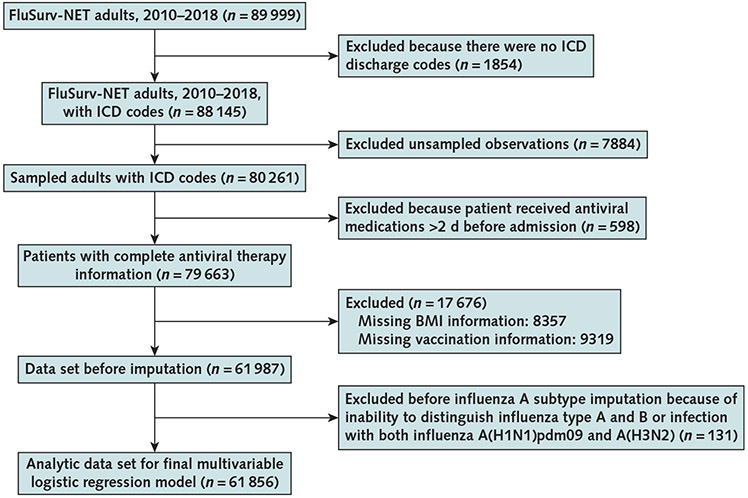

During influenza seasons from 2010 through 2018, FluSurv-NET received reports of 89 999 adults hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed influenza (Figure 1). We excluded 1854 patients with no ICD discharge codes. Among 80 261 adults sampled for medical record review and included in our analysis (median age, 69 years [interquartile range, 54 to 81 years]), 11.7% had an ICD discharge code for an acute cardiovascular event, most commonly aHF (6.2%) or aIHD (5.7%) and less commonly hypertensive crisis (1.0%), cardiogenic shock (0.3%), acute myocarditis (0.1%), acute pericarditis (0.05%), or cardiac tamponade (0.02%).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study population.

BMI = body mass index; FluSurv-NET = U.S. Influenza Hospitalization Surveillance Network; ICD = International Classification of Diseases.

The unadjusted weighted prevalence of acute cardiovascular events was higher in patients who had underlying medical conditions–particularly chronic cardiovascular conditions, chronic metabolic conditions, chronic renal disease, and chronic hematologic conditions-than in those without acute cardiovascular events (data not shown). In this study, 20.6% of those with chronic cardiovascular disease, 19.3% of those with chronic renal disease, and 14.8% of those with diabetes had an acute cardiovascular event (Appendix Table 2, available at Annals.org). Overall, 47.2% of patients received an influenza vaccine in the current season, 39.2% did not receive it, and 13.6% had unknown vaccination status (data not shown).

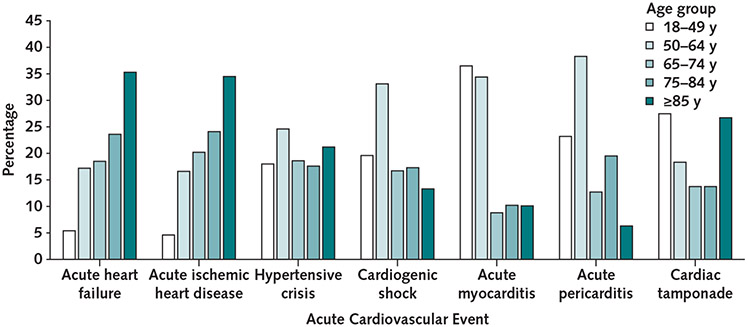

Among patients with an acute cardiovascular event, 53.5% had aHF, 49.3% aIHD, 8.3% hypertensive crisis, 2.7% cardiogenic shock, 0.8% acute myocarditis, 0.5% acute pericarditis, and 0.2% cardiac tamponade. Most patients with acute myocarditis, acute pericarditis, or cardiogenic shock were aged 18 to 64 years, whereas most with aHF or aIHD were aged 65 years or older (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Distribution of acute cardiovascular events, by age group (n = 9046).

Overall, patients with acute cardiovascular events had a median length of hospital stay of 5 days, 31.2% were admitted to the intensive care unit, 14.0% required mechanical ventilatory support, and 7.3% died in the hospital (Table 1). Patients with cardiogenic shock had the longest median length of stay (9 days), and 38.9% died during the hospitalization. When we excluded cardiogenic shock from the analysis, 6.4% of patients with another acute cardiovascular event died in the hospital. Among the 2683 patients who died in the hospital, 23.7% had an associated acute cardiovascular event, excluding the diagnosis of cardiogenic shock (data not shown). In-hospital outcomes did not differ substantively between male and female patients with acute cardiovascular events (data not shown).

Table 1.

Hospital Outcomes of Adults With Laboratory-Confirmed Influenza Virus Infection, by Acute Cardiovascular Event*

| Acute Diagnosis | Total† | Median Length of Stay (IQR), d |

Intensive Care Unit Admission |

Mechanical Ventilatory Support |

Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation |

In-Hospital Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All acute cardiovascular events‡ | 9046 (11.5) | 5 (3–8) | 2901 (31.2) | 1319 (14.0) | 40 (0.4) | 740 (7.3) |

| Acute heart failure | 4828 (6.2) | 5 (3–9) | 1443 (29.2) | 595 (11.9) | 15 (0.3) | 352 (6.5) |

| Acute ischemic heart disease | 4412 (5.7) | 5 (3–8) | 1645 (35.9) | 777 (16.8) | 13 (0.3) | 423 (8.5) |

| Hypertensive crisis | 788 (1.0) | 4 (2–6) | 182 (23.4) | 60 (7.6) | 1 (0.1) | 10 (1.2) |

| Cardiogenic shock | 261 (0.3) | 9 (4–17) | 239 (92.2) | 174 (65.8) | 15 (5.6) | 105 (38.9) |

| Acute myocarditis | 74 (0.1) | 4 (2–8) | 33 (46.9) | 21 (30.4) | 6 (7.6) | 9 (11.3) |

| Acute pericarditis | 42 (0.1) | 3 (2–7) | 12 (32.0) | 2 (10.9) | 2 (4.2) | 1 (2.1) |

| Cardiac tamponade | 19 (0.03) | 7 (5–12) | 9 (54.2) | 3 (13.8) | 2 (9.2) | 1 (4.6) |

| Noncardiovascular event | 71 215 (88.5) | 3 (2–5) | 9897 (13.5) | 3907 (5.3) | 191 (0.3) | 1943 (2.5) |

FluSurv-NET = U.S. Influenza Hospitalization Surveillance Network; IQR = interquartile range.

Numbers are unweighted values, and percentages are weighted values. Values are numbers (percentages) unless otherwise specified.

Percentage listed out of all FluSurv-NET patients with and without acute cardiovascular events (n = 80 261).

Acute cardiovascular events are non–mutually exclusive diagnoses.

After excluding patients who received antiviral treatment 2 days or more before hospital admission; those with missing data on antiviral treatment, vaccination status for the current season, and BMI; and those for whom influenza subtype was not imputed, we included 61 856 patients (Figure 1) in the multivariable logistic regression models to examine factors associated with aHF and aIHD.

Compared with patients aged 18 to 49 years, older patients had increased risk for aHF (50 to 64 years: adjusted risk ratio [aRR], 1.40 [95% CI, 1.22 to 1.61]; 65 to 74 years: aRR, 1.58 [CI, 1.36 to 1.84]; 75 to 84 years: aRR, 1.88 [CI, 1.62 to 2.18]; and ≥85 years: aRR, 2.32 [CI, 2.00 to 2.70]) (Table 2). Other factors associated with increased risk for aHF included extreme obesity (aRR, 1.19 [CI, 1.06 to 1.33]), current tobacco use (aRR, 1.17 [CI, 1.07 to 1.28]), atrial fibrillation (aRR, 1.40 [CI, 1.30 to 1.52]), chronic heart failure or cardiomyopathy (aRR, 8.33 [CI, 7.60 to 9.12]), coronary artery disease (aRR, 1.18 [CI, 1.10 to 1.27]), diabetes mellitus (aRR, 1.09 [CI, 1.01 to 1.17]), and chronic renal disease (aRR, 1.22 [CI, 1.14 to 1.32]). Risk for aHF was significantly lower for patients vaccinated against influenza at least 2 weeks before hospitalization than for unvaccinated patients (aRR, 0.86 [CI, 0.80 to 0.92]).

Table 2.

Factors Associated With Acute Ischemic Heart Disease and Acute Heart Failure in Adults Hospitalized With Influenza (n = 61 856)*

| Factor | Acute Heart Failure |

Acute Ischemic Heart Disease |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted Risk Ratio (95% CI) |

Adjusted Prevalence (95% CI) |

Adjusted Risk Ratio (95% CI) |

Unadjusted Risk Ratio (95% CI) |

Adjusted Prevalence (95% CI) |

Adjusted Risk Ratio (95% CI) |

|

| Age group | ||||||

| 18–49 y | Reference | 3.90 (3.39–4.39) | Reference | Reference | 2.07 (1.74–2.39) | Reference |

| 50–64 y | 2.6 (2.28–2.97) | 5.46 (5.04–5.88) | 1.40 (1.22–1.61) | 2.94(2.54–3.41) | 4.12 (3.83–4.59) | 2.04 (1.72–2.43) |

| 65–74 y | 3.51 (3.06–4.01) | 6.17 (5.68–6.66) | 1.58 (1.36–1.84) | 4.45 (3.84–5.16) | 6.04 (5.52–6.56) | 2.93 (2.44–3.51) |

| 75–84 y | 4.63 (4.07–5.28) | 7.31 (6.79–7.82) | 1.88 (1.62–2.18) | 5.55 (4.80–6.41) | 7.07 (6.52–7.63) | 3.43 (2.85–4.12) |

| ≥85 y | 5.95 (5.25–6.73) | 9.04 (8.47–9.62) | 2.32 (2.00–2.70) | 6.84 (5.95–7.86) | 9.02 (8.36–9.68) | 4.37 (3.64–5.25) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | Reference | 6.81 (6.48–7.14) | Reference | Reference | 6.43 (6.09–6.76) | Reference |

| Female | 0.89 (0.84–0.95) | 6.74 (6.43–7.05) | 0.99 (0.93–1.06) | 0.77 (0.73–0.82) | 5.56 (5.27–5.86) | 0.87 (0.80–0.93) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | Reference | 6.84 (6.56–7.12) | Reference | Reference | 5.83 (5.56–6.09) | Reference |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 0.76 (0.70–0.83) | 6.41 (5.87–6.95) | 0.94 (0.85–1.03) | 0.77 (0.70–0.84) | 6.02 (5.4–6.60) | 1.03 (0.93–1.15) |

| Hispanic | 0.65 (0.57–0.76) | 7.15 (6.10–8.20) | 1.05 (0.90–1.22) | 0.75 (0.65–0.87) | 6.53 (5.42–7.64) | 1.12 (0.94–1.34) |

| Other | 0.82 (0.74–0.90) | 6.74 (6.03–7.45) | 0.99 (0.88–1.10) | 1.06 (0.96–1.16) | 6.46 (5.77–7.15) | 1.11 (0.99–1.25) |

| BMI | ||||||

| Underweight(<18.5 kg/m2) | 0.77 (0.64–0.93) | 5.64 (4.61–6.66) | 0.84 (0.70–1.02) | 0.97 (0.82–1.13) | 6.80 (5.71–7.90) | 1.05 (0.89–1.25) |

| Normal (18.5–24.9 kg/m2) | Reference | 6.68 (6.26–7.10) | Reference | Reference | 6.47 (6.05–6.88) | Reference |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m2) | 1.01 (0.92–1.09) | 6.27 (5.87–6.67) | 0.94 (0.86–1.02) | 0.94 (0.86–1.02) | 5.88 (5.47–6.28) | 0.91 (0.83–1.00) |

| Obesity (30.0–39.9 kg/m2) | 1.08 (1.00–1.18) | 7.07 (6.65–7.50) | 1.06 (0.97–1.15) | 0.78 (0.71–0.85) | 5.46 (5.06–5.86) | 0.84 (0.77–0.93) |

| Extreme obesity (≥40.0 kg/m2) | 1.3 (1.18–1.45) | 7.94 (7.19–8.68) | 1.19 (1.06–1.33) | 0.68 (0.60–0.78) | 5.74 (4.95–6.52) | 0.89 (0.76–1.03) |

| Tobacco use | ||||||

| None | Reference | 6.57 (6.24–6.90) | Reference | Reference | 5.62 (5.31–5.94) | Reference |

| Current | 0.86 (0.79–0.94) | 7.70 (7.11–8.30) | 1.17 (1.07–1.28) | 0.98 (0.90–1.08) | 7.47 (6.81–8.13) | 1.33 (1.20–1.48) |

| Previous | 1.41 (1.31–1.51) | 6.66 (6.30–7.03) | 1.01 (0.94–1.09) | 1.37 (1.28–1.48) | 5.82 (5.46–6.18) | 1.03 (0.95–1.13) |

| Medical history† | ||||||

| Atrial fibrillation | 3.49 (3.28–3.71) | 8.56 (8.02–9.10) | 1.40 (1.30–1.52) | 1.95 (1.80–2.11) | 6.32 (5.76–6.88) | 1.08 (0.97–1.19) |

| Chronic heart failure or cardiomyopathy | 11.27 (10.55–12.04) | 20.33 (19.39–21.26) | 8.33 (7.60–9.12) | 3.05 (2.86–3.25) | 10.05 (9.36–10.74) | 2.11 (1.93–2.31) |

| Coronary artery disease | 2.78 (2.62–2.95) | 7.53 (7.11–7.96) | 1.18 (1.10–1.27) | 2.81 (2.64–3.00) | 8.63 (8.08–9.18) | 1.75 (1.61–1.91) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.67 (1.58–1.78) | 7.11 (6.73–7.49) | 1.09 (1.01–1.17) | 1.42 (1.33–1.52) | 6.51 (6.11–6.90) | 1.15 (1.06–1.24) |

| Chronic renal disease | 2.53 (2.38–2.69) | 7.73 (7.30–8.16) | 1.22 (1.14–1.32) | 1.93 (1.80–2.07) | 7.00 (6.51–7.49) | 1.25 (1.15–1.36) |

| Influenza vaccination status | ||||||

| Vaccinated | 0.74 (0.69–0.79) | 6.39 (6.11–6.67) | 0.86 (0.80–0.92) | 0.81 (0.75–0.87) | 5.48 (5.21–5.75) | 0.80 (0.74–0.87) |

| Not vaccinated | Reference | 7.44 (7.05–7.83) | Reference | Reference | 6.82 (6.43–7.21) | Reference |

| Antiviral therapy‡ | ||||||

| No treatment | 1.02 (0.93–1.11) | 7.11 (6.50–7.72) | 1.10 (1.00–1.20) | 0.86 (0.78–0.96) | 5.79 (5.14–6.43) | 0.99 (0.88–1.11) |

| Early treatment | Reference | 6.47 (6.22–6.72) | Reference | Reference | 5.86 (5.62–6.10) | Reference |

| Late treatment | 1.64 (1.49–1.79) | 9.25 (8.39–10.10) | 1.43 (1.29–1.58) | 1.3 (1.18–1.44) | 7.56 (6.61–8.32) | 1.27 (1.13–1.44) |

| Influenza type or subtype | ||||||

| B | Reference | 6.67 (6.15–7.18) | Reference | Reference | 5.59 (5.09–6.10) | Reference |

| A(H1N1)pdm09 | 0.77 (0.69–0.86) | 7.22 (6.27–8.17) | 1.08 (0.93–1.26) | 0.73 (0.65–0.83) | 6.38 (5.34–7.42) | 1.14 (0.95–1.37) |

| A(H3N2) | 1.09 (1.00–1.18) | 6.71 (6.39–7.03) | 1.01 (0.92–1.10) | 1.16 (1.06–1.27) | 6.00 (5.69–6.32) | 1.07 (0.96–1.20) |

BMI = body mass index.

Patients were excluded if they were missing BMI, were missing influenza vaccination information, had been treated with influenza antiviral medication >2 d before hospital admission, had an infection that could not be distinguished between influenza type A and B, or were co-infected with A(H1N1)pdm09 and A(H3N2). To adjust for possible confounding by site, we included site as a variable in the model for both acute heart failure and acute ischemic heart disease. The final models for both of these conditions were adjusted for season, surveillance site, age group, sex, race/ethnicity, BMI, tobacco use history, medical history of atrial fibrillation, chronic congestive heart failure or cardiomyopathy, coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, chronic renal disease, influenza vaccination status, antiviral therapy, and influenza type or subtype. Regression models were run on each of the 70 imputed data sets and combined using SAS Callable-SUDAAN.

For each medical condition, no history of the condition was used as the reference group.

Antiviral treatment timing was determined relative to the patient's admission date and not the acute cardiovascular event or initial symptom onset.

Older age was also significantly associated with higher risk for aIHD compared with age 18 to 49 years (50 to 64 years: aRR, 2.04 [CI, 1.72 to 2.43]; 65 to 74 years: aRR, 2.93 [CI, 2.44 to 3.51]; 75 to 84 years: aRR, 3.43 [CI, 2.85 to 4.12]; and ≥85 years: aRR, 4.37 [CI, 3.64 to 5.25]) (Table 2). Other factors associated with higher risk for aIHD included current tobacco use (aRR, 1.33 [CI, 1.20 to 1.48]), chronic heart failure or cardiomyopathy (aRR, 2.11 [CI, 1.93 to 2.31]), coronary artery disease (aRR, 1.75 [CI, 1.61 to 1.91]), diabetes mellitus (aRR, 1.15 [CI, 1.06 to 1.24]), and chronic renal disease (aRR, 1.25 [CI, 1.15 to 1.36]). Women (aRR, 0.87 [CI, 0.80 to 0.93]) and obese patients (aRR, 0.84 [CI, 0.77 to 0.93]) had lower risk for aIHD, as did patients who were vaccinated against influenza at least 2 weeks before hospitalization compared with those who were not vaccinated (aRR, 0.80 [CI, 0.74 to 0.87]).

Patients who received late antiviral treatment had higher risk for aHF and aIHD than those who received early antiviral treatment; however, information on the timing of antiviral treatment in relation to that of acute cardiovascular events was not available.

Discussion

In this study of more than 80 000 adults hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed influenza in the United States, approximately 12% of patients had acute cardiovascular events, most commonly aHF and aIHD. Although respiratory tract diagnoses are most commonly associated with influenza (28), acute cardiovascular events are important contributors to influenza-related morbidity and mortality. Almost one third of patients with an acute cardiovascular event were admitted to the intensive care unit, and 7% (6% excluding those with cardiogenic shock) ultimately died during hospitalization, underscoring the severity of cardiovascular complications with concomitant influenza virus infection. Underlying cardiovascular disease was strongly associated with both aHF and aIHD among patients hospitalized with influenza. Our findings highlight the importance of preventing influenza virus infection, especially in those with underlying chronic conditions.

Influenza may be an important but underrecognized contributor to the health care burden of hospitalized cardiovascular disease. In 1 prospective study in which all patients admitted to a coronary care unit were systematically tested for influenza, 8% were found to have influenza virus infection (30). Another study estimated the proportion of myocardial infarction–associated hospitalizations that are related to influenza to be 3% to 5% in England and Wales and 8% in Hong Kong at the peak of influenza circulation (31). Costs associated with cardiovascular disease may increase in the next 20 years, with lost productivity from illness and premature death (32). Public health interventions should include focused attention on preventable causes of this health care burden, including prevention of influenza virus infection.

Although this analysis was not designed to assess the effectiveness of influenza vaccination or antiviral medications, evidence suggests that these interventions may have benefits in attenuating disease severity. Several studies have found that vaccination (33, 34) and influenza antiviral medication (35, 36) help decrease severity of disease and symptom duration. Yet despite these benefits, influenza vaccination rates are suboptimal: Only 33.9% to 56.3% of U.S. adults (varying by state) received the influenza vaccine in the 2018-to-2019 season (37). Especially among patients with risk factors for acute cardiovascular events, practitioners may play an essential role in mitigating the burden of cardiovascular disease by maintaining high rates of annual influenza vaccination (38-41) and providing early antiviral treatment to patients with suspected or confirmed influenza (42-44).

The most common acute cardiovascular events among adults hospitalized with influenza were aHF and aIHD. Although causality cannot be determined from our study alone, the pathophysiologic mechanisms that lead to cardiovascular events after influenza virus infection have been described. For example, systemic inflammatory response in the setting of influenza virus infection promotes oxidative stress, leading to hemodynamic consequences and activation of prothrombotic pathways (13, 15, 45-47) as evidenced by increased levels of serum troponin (48) and myosin light chains (49) in some patients hospitalized with influenza. Patients with preexisting conditions may be at greater risk for cardiovascular decompensation because decreased circulatory reserve at baseline leads to increased risk for in-hospital morbidity and mortality in the setting of influenza infection (50, 51). In patients with aIHD, various factors—including direct results of plaque disruption (3), vasoconstrictive effects of systemic inflammation (46), increased metabolic demand from systemic inflammation (15), and ambient temperature (52, 53)—may be the basis for these acute cardiovascular events in the setting of influenza infection. Although direct associations between heart failure exacerbation and influenza have not been well characterized (54), aHF-associated hospitalizations correlate with influenza activity (55, 56). During the influenza season, practitioners should consider an influenza diagnosis when a patient is hospitalized with an exacerbation of or new-onset cardiovascular event (57). Early identification of influenza, especially in those at greater risk for complications like acute cardiovascular events, could lead to earlier treatment with antiviral medication, reduce unnecessary antibiotic use, and lessen the morbidity and mortality of disease (57).

We found that older patients may have a higher risk for aHF and aIHD when hospitalized with influenza, a finding supported by previous studies (4, 31, 58, 59). We showed that patients with preexisting cardiovascular conditions, namely chronic heart failure or cardiomyopathy, and known cardiovascular risk factors, such as tobacco use, diabetes, and renal disease, had the highest risk for aHF or aIHD with influenza. In fact, 1 in 5 patients with a chronic cardiovascular condition who were hospitalized with influenza also had an acute cardiovascular event during the hospitalization. Of note, extreme obesity was found to be associated with higher risk for aHF, but obesity was associated with lower risk for aIHD in patients hospitalized with influenza virus infection. In observational studies, this finding may be related to the previously described obesity paradox, whereby certain subgroups of patients who are obese have better cardiovascular outcomes than those with lower BMI (60). Other explanations that contribute to these findings may include nonpurposeful weight loss associated with chronic disease (61), changes in inflammatory response due to obesity (62), increased muscle mass interpreted as obesity (61), or a practitioner's threshold for admission of patients who are obese or have a history of chronic comorbid conditions. Ultimately, the reasons for the reduced association between obesity and aIHD in patients with influenza are not clear, and additional studies are required to better understand these associations.

Our study adds to the growing body of literature on the effect of acute cardiovascular events on the morbidity and mortality associated with influenza. These include long hospital stays and severe in-hospital outcomes, including death. Previous studies have shown that patients with influenza virus infection and cardiovascular complications, such as heart failure (50) and acute myocardial infarction (63), had higher mortality than those without influenza. They demonstrate that cardiovascular complications related to influenza may be significant outcomes of infection and that estimations of influenza burden relying solely on respiratory diagnoses are likely to underestimate the true burden of influenza-related complications.

Our study has limitations to consider. First, patients were identified from practitioner-initiated influenza testing. Practitioners are more likely to test for influenza in patients presenting with symptoms of respiratory infection and other influenza-like illness (64); thus, we may have underestimated the true prevalence of influenza-associated cardiovascular events (65). Second, because our study included only hospitalized patients with laboratory-confirmed influenza, uncontrolled collider bias is possible if influenza testing is a common effect of the exposures we considered (66). Third, we used ICD discharge codes to classify acute cardiovascular event groups, and diagnoses were not based on laboratory confirmation of a cardiovascular event. Although ICD codes are a common method to identify cardiovascular complications (4, 15, 31, 55), administrative codes may be subject to misclassification bias if they are carried over from recent hospitalizations or if ICD coding is affected by billing practices, the experience of medical coders, or incomplete capture of medical information documented by the clinician (67). Using ICD discharge codes also limits our ability to distinguish between acute and chronic conditions and may bias the observed association between acute and underlying cardiovascular diseases. We attempted to lessen this risk for misclassification by selecting ICD discharge codes of diagnoses that were most likely limited to the current hospital stay. In addition, FluSurv-NET captures only the first 9 ICD codes listed in the medical record, and diagnoses listed thereafter are not included in the analysis. Fourth, we could not assess the timing of antiviral therapy relative to the onset of aHF or aIHD; thus, our finding of higher odds of aHF and aIHD among those who received late antiviral treatment should be interpreted with caution. Antiviral therapy was included in the model to control for confounding, and the aRRs should not be interpreted as a measure of antiviral effectiveness against aHF or aIHD. Last, we may not have captured all confounders within our regression models for aHF and aIHD. For example, hypertension and hyperlipidemia are known risk factors for heart failure and ischemic heart disease but were not collected as underlying conditions in FluSurv-NET.

In this study, acute cardiovascular events were common diagnoses among adults hospitalized with influenza, particularly among older patients and those with underlying chronic disease. A high percentage of patients with acute cardiovascular events experienced in-hospital morbidity and mortality. Increasing rates of influenza vaccination, especially among those with cardiovascular risk factors, is essential in preventing infection and potentially attenuating influenza-related cardiovascular complications and adverse outcomes.

Acknowledgment:

The authors thank all of those involved in the FluSurv-NET sites for their support of this study, data collection, and management, including Lauren Grant, MApStat (Battelle Memorial Institute and Influenza Division, CDC, Atlanta, Georgia); Charisse Cummings, MPH (Chickasaw Nation Industries, Norman, Oklahoma, and Influenza Division, CDC, Atlanta, Georgia); James Meek, MPH, Darcy Fazio, BS, Tamara Rissman, MPH, and Amber Maslar, MPA (Connecticut Emerging Infections Program, Yale School of Public Health, New Haven, Connecticut); Monica Farley, MD, Stepy Thomas, MSPH, Suzanne Segler, MPH, Kyle Openo, DrPH, and Emily Fawcett, MPH (Georgia Emerging Infections Program, Atlanta, Georgia); Patricia Ryan, MS, Robert Sunkel, MPH, Alicia Brooks, MPH, Sophia Wozny, MPH, Cindy Zerrlaut, Elisabeth Vaeth, MPH, Rebecca Perlmutter, MPH, Molly Hyde, MHS, Brian Bachaus, MS, and Emily Blake, MPH (Maryland Department of Health, Baltimore, Maryland), Jim Collins, MPH, Shannon Johnson, MPH, and Justin Henderson, MPH (Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, Lansing, Michigan), Melissa McMahon, Craig Morin, MPH, Anna Strain, Sara Vetter, and Team Flu (Minnesota Department of Health, St. Paul, Minnesota); Alison Muse, MPH, Nancy Spina, MPH, and Eva Pradhan, MPH (New York State Department of Health, Albany, New York); Christina Felsen, MPH, and Maria Gaitan (University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, Rochester, New York); Nicholas Fisher, BS, and Krista Lung, MPH (Ohio Department of Health, Columbus, Ohio); and Karen Leib, RN, Katie Dyer, Danielle Ndi, and Tiffanie Markus, PhD (Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee).

Grant Support: By the CDC through the Emerging Infections Program cooperative agreement (grant CK17-1701), the 2008–2013 Influenza Hospitalization Surveillance Project (IHSP) cooperative agreement (grant 5U38HM000414), the 2013–2018 IHSP cooperative agreement (grant 5U38OT000143), and the 2018–2023 IHSP cooperative agreement (grant 5NU38OT000297).

Appendix

Appendix Table 1.

ICD Discharge Diagnostic Codes (ICD-9 and ICD-10), by Acute Cardiovascular Event

| Disease Condition | ICD-9 Code | ICD-10 Code |

|---|---|---|

| Acute myocarditis | ||

| Acute myocarditis | 422 | I40 |

| Influenza due to other identified influenza virus with myocarditis | — | J10.82 |

| Influenza due to unidentified influenza virus with myocarditis | — | J11.82 |

| Acute pericarditis | 420 | I30 |

| Cardiac tamponade | 423.3 | I31.4 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 785.51 | R57.0 |

| Acute heart failure | ||

| Acute systolic heart failure | 428.21 | I50.21 |

| Acute-on-chronic systolic heart failure | 428.23 | I50.23 |

| Acute diastolic heart failure | 428.31 | I50.31 |

| Acute-on-chronic diastolic heart failure | 428.33 | I50.33 |

| Acute combined systolic and diastolic heart failure | 428.41 | I50.41 |

| Acute-on-chronic combined systolic and diastolic heart failure | 428.43 | I50.43 |

| Acute right heart failure | 428.9 | I50.811 |

| Acute-on-chronic right heart failure | 428.9 | I50.813 |

| Hypertensive crisis | — | I16 |

| Malignant essential hypertension | 401.0 | — |

| Malignant hypertensive heart disease | 402.0 | — |

| Malignant hypertensive heart disease without heart failure | 402.00 | — |

| Malignant hypertensive heart disease with heart failure | 402.01 | — |

| Malignant hypertensive renal disease | 403.0 | — |

| Malignant hypertensive heart and renal disease | 404.0 | — |

| Malignant secondary hypertension | 405.0 | — |

| Malignant renovascular hypertension | 405.01 | — |

| Other malignant secondary hypertension | 405.09 | — |

| Hypertensive urgency | — | I16.0 |

| Hypertensive emergency | — | I16.1 |

| Hypertensive crisis, unspecified | — | I16.9 |

| Acute ischemic heart disease | ||

| Unstable angina | 411.1 | I20.0 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 410 | I21 |

| Acute myocardial infarction of anterolateral wall | 410.0 | — |

| Acute myocardial infarction of other anterior wall | 410.1 | — |

| Acute myocardial infarction of inferolateral wall | 410.2 | — |

| Acute myocardial infarction of inferoposterior wall | 410.3 | — |

| Acute myocardial infarction of other inferior wall | 410.4 | — |

| Acute myocardial infarction of other lateral wall | 410.5 | — |

| True posterior wall infarction | 410.6 | — |

| Subendocardial infarction | 410.7 | — |

| Acute myocardial infarction of other specified sites | 410.8 | — |

| Acute myocardial infarction of unspecified site | 410.9 | — |

| ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction of anterior wall | — | I21.0 |

| ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction of inferior wall | — | I21.1 |

| ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction of other sites | — | I21.2 |

| ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction of unspecified site | — | I21.3 |

| Non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction | 410.71 | I21.4 |

| Acute myocardial infarction, unspecified | — | I21.9 |

| Subsequent ST-segment elevation and non–ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction | 410.01–410.11 | I22 |

| Subsequent ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction of anterior wall | 410.21, 410.31, 410.41 | I22.0 |

| Subsequent ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction of inferior wall | 410.21, 410.31, 410.41 | I22.1 |

| Subsequent non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction | 410.71 | I22.2 |

| Subsequent ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction of other sites | 410.51, 410.61, 410.81 | I22.8 |

| Subsequent ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction of unspecified site | 410.91 | I22.9 |

| Other acute and subacute forms of ischemic heart disease | 411 | I24 |

ICD = International Classification of Diseases; ICD-9 = ICD, Ninth Revision; ICD-10 = ICD, 10th Revision.

Appendix Table 2.

Unadjusted Weighted Prevalence of Acute Cardiovascular Events, by Patient Characteristic*

| Characteristic | Total (n = 80 261), n |

Patients With Acute Cardiovascular Events (n = 9046), n (%) |

Patients Without Acute Cardiovascular Events (n = 71 215), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza season | |||

| 2010–2011 | 4520 | 360 (8.0) | 4160 (92.0) |

| 2011–2012 | 1842 | 113 (6.1) | 1729 (93.9) |

| 2012–2013 | 10 085 | 1087 (10.8) | 8998 (89.2) |

| 2013–2014 | 7978 | 717 (9.0) | 7261 (91.0) |

| 2014–2015 | 14 902 | 1820 (12.2) | 13 082 (87.8) |

| 2015–2016 | 7263 | 711 (9.8) | 6552 (90.2) |

| 2016–2017 | 15 275 | 1887 (12.4) | 13 388 (87.6) |

| 2017–2018 | 18 396 | 2351 (13.2) | 16 045 (86.8) |

| Age | |||

| 18–49 y | 16 142 | 656 (4.1) | 15 486 (95.9) |

| 50–64 y | 19 020 | 1652 (8.9) | 17 368 (91.1) |

| 65–74 y | 14 456 | 1726 (12.0) | 12 730 (88.0) |

| 75–84 y | 14 057 | 2049 (14.7) | 12 008 (85.3) |

| ≥85 y | 16 586 | 2963 (17.7) | 13 623 (82.3) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 35 571 | 4361 (12.5) | 31 210 (87.5) |

| Female | 44 690 | 4685 (10.8) | 40 005 (89.2) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White, non-Hispanic | 49 308 | 5887 (12.2) | 43 421 (87.8) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 14 674 | 1534 (10.5) | 13 140 (89.5) |

| Hispanic | 5657 | 458 (8.7) | 5199 (91.3) |

| Other | 10 622 | 1167 (11.4) | 9455 (88.6) |

| BMI | |||

| Underweight (<18.5 kg/m2) | 3068 | 335 (10.8) | 2733 (89.2) |

| Normal (18.5–24.9 kg/m2) | 20 921 | 2480 (12.0) | 18 441 (88.0) |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m2) | 20 516 | 2368 (11.9) | 18 148 (88.1) |

| Obesity(30.0–39.9 kg/m2) | 19 979 | 2223 (11.5) | 17 756 (88.5) |

| Extreme obesity (≥40.0 kg/m2) | 7376 | 889 (12.3) | 6487 (87.7) |

| Influenza vaccination status in corresponding year | |||

| Yes | 34 732 | 4511 (10.0) | 32 921 (90.0) |

| No | 32 218 | 3157 (12.3) | 29 061 (87.7) |

| Missing status | 10 611 | 1378 (13.5) | 9233 (86.5) |

| Tobacco use history | |||

| Current† | 15 427 | 1526 (10.2) | 13 901 (89.8) |

| Previoust‡ | 22 384 | 3178 (14.5) | 19 206 (85.5) |

| Never used or unknown† | 36 416 | 3882 (10.9) | 32 534 (89.1) |

| Medical history§ | |||

| No known medical history | 6064 | 312 (5.3) | 5752 (94.7) |

| Chronic disease | |||

| Neurologic | 19 829 | 2254 (11.3) | 17 575 (88.7) |

| Respiratory tract | 33 481 | 3770 (11.5) | 29 711 (88.5) |

| Cardiovascular | 31 919 | 6519 (20.6) | 25 400 (79.4) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 10 467 | 2370 (22.8) | 8097 (77.2) |

| Coronary artery disease | 15 956 | 3400 (21.5) | 12 556 (78.5) |

| Chronic heart failure or cardiomyopathy | 14 866 | 4589 (31.0) | 10 277 (69.0) |

| Metabolic | 33 578 | 4697 (14.1) | 28 881 (85.9) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 24 637 | 3637 (14.8) | 21 000 (85.2) |

| Renal | 15 655 | 3037 (19.3) | 12 618 (80.7) |

| Hepatic disease† | 3065 | 319 (10.9) | 2746 (89.1) |

| Hematologic† | 3677 | 493 (13.6) | 3184 (86.4) |

| Immunosuppressive† | 13 669 | 1247 (9.3) | 12 422 (90.7) |

| Pregnant | 2188 | 5 (0.2) | 2183 (99.8) |

| Antiviral therapyǁ | |||

| No treatment | 10 579 | 1115 (10.8) | 9464 (89.2) |

| Early treatment | 62 772 | 6903 (11.3) | 55 869 (88.7) |

| Late treatment¶ | 6312 | 973 (15.8) | 5339 (84.2) |

| Influenza type or subtype, imputed** | |||

| A(H1N1) pdm09 | 15 443 | 1333 (8.8) | 14 110 (91.2) |

| A(H3N2) | 49 597 | 6030 (12.4) | 43 567 (87.6) |

| B | 15 024 | 1671 (11.4) | 13 353 (88.6) |

BMI = body mass index.

Numbers are unweighted values, and percentages are weighted values. Percentages are row percentages.

From 2011–2018.

From 2012–2018.

Diagnoses are not mutually exclusive.

598 patients received influenza antiviral therapy >2 d before hospital admission and were excluded from this frequency. Treatment timing was relative to the patient's hospital admission date and not relative to the acute cardiovascular event or initial symptom onset.

90 patients received antiviral treatment >6 d after hospital admission.

Patients were excluded from influenza subtype imputation if influenza type could not be distinguished between influenza A and B or if they had A(H1N1)pdm09 and A(H3N2) co-infection (n = 197); frequencies are averaged from 70 imputed data sets.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the CDC. Dr. Chow had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Disclosures: Disclosures can be viewed at www.acponline.org/authors/icmje/ConflictOfInterestForms.do?msNum=M20-1509.

Reproducible Research Statement: Study protocol and statistical code: Available from Dr. Garg (izj7@cdc.gov). Data set: Not available.

Current author addresses and author contributions are available at Annals.org.

Contributor Information

Eric J. Chow, Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia.

Melissa A. Rolfes, Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia.

Alissa O’Halloran, Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia.

Evan J. Anderson, Emory University School of Medicine and Atlanta Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Atlanta, Georgia.

Nancy M. Bennett, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, Rochester, New York.

Laurie Billing, Ohio Department of Health, Columbus, Ohio.

Shua Chai, Center for Preparedness and Response, Atlanta, Georgia.

Elizabeth Dufort, New York State Department of Health, Albany, New York.

Rachel Herlihy, Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, Denver, Colorado.

Sue Kim, Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, Lansing, Michigan.

Ruth Lynfield, Minnesota Department of Health, St. Paul, Minnesota.

Chelsea McMullen, New Mexico Department of Health, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Maya L. Monroe, Maryland Department of Health, Baltimore, Maryland.

William Schaffner, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tennessee.

Melanie Spencer, Salt Lake County Health Department, Salt Lake City, Utah.

H. Keipp Talbot, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tennessee.

Ann Thomas, Oregon Public Health Division, Portland, Oregon.

Kimberly Yousey-Hindes, Yale School of Public Health, New Haven, Connecticut.

Carrie Reed, Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia.

Shikha Garg, Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia.

References

- 1.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. ; Writing Group Members. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2016 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133:e38–360. [PMID: 26673558] doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smeeth L, Thomas SL, Hall AJ, et al. Risk of myocardial infarction and stroke after acute infection or vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2611–8. [PMID: 15602021] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Musher DM, Abers MS, Corrales-Medina VF. Acute infection and myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:171–176. [PMID: 30625066] doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1808137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kwong JC, Schwartz KL, Campitelli MA, et al. Acute myocardial infarction after laboratory-confirmed influenza infection. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:345–353. [PMID: 29365305] doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1702090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sellers SA, Hagan RS, Hayden FG, et al. The hidden burden of influenza: a review of the extra-pulmonary complications of influenza infection. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2017;11:372–393. [PMID: 28745014] doi: 10.1111/irv.12470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mamas MA, Fraser D, Neyses L. Cardiovascular manifestations associated with influenza virus infection. Int J Cardiol. 2008;130:304–9. [PMID: 18625525] doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.04.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Estabragh ZR, Mamas MA. The cardiovascular manifestations of influenza: a systematic review. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:2397–403. [PMID: 23474244] doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.01.274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fleming DM, Cross KW, Pannell RS. Influenza and its relationship to circulatory disorders. Epidemiol Infect. 2005;133:255–62. [PMID: 15816150] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Past seasons estimated influenza disease burden. 2018. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/flu/about/burden/past-seasons.html on 17 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reed C, Chaves SS, Perez A, et al. Complications among adults hospitalized with influenza: a comparison of seasonal influenza and the 2009 H1N1 pandemic. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:166–74. [PMID: 24785230] doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Public health weekly reports for November 11, 1932. Public Health Rep. 1932;47:2159–2189. [PMID: 19315373] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reichert TA, Simonsen L, Sharma A, et al. Influenza and the winter increase in mortality in the United States, 1959-1999. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:492–502. [PMID: 15321847] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fares A Winter cardiovascular diseases phenomenon. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:266–79. [PMID: 23724401] doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.110430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nguyen JL, Yang W, Ito K, et al. Seasonal influenza infections and cardiovascular disease mortality. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1:274–81. [PMID: 27438105] doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.0433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foster ED, Cavanaugh JE, Haynes WG, et al. Acute myocardial infarctions, strokes and influenza: seasonal and pandemic effects. Epidemiol Infect. 2013;141:735–44. [PMID: 23286343] doi: 10.1017/S0950268812002890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finland M, Parker F Jr, Barnes MW, et al. Acute myocarditis in influenza A infections. Am J Med Sci. 1945;209:455–68. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bowles NE, Ni J, Kearney DL, et al. Detection of viruses in myocardial tissues by polymerase chain reaction: evidence of adenovirus as a common cause of myocarditis in children and adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:466–72. [PMID: 12906974] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spoto S, Valeriani E, Locorriere L, et al. Influenza B virus infection complicated by life-threatening pericarditis: a unique case-report and literature review. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:40. [PMID: 30630424] doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3606-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edelen JS, Bender TR, Chin TD. Encephalopathy and pericarditis during an outbreak of influenza. Am J Epidemiol. 1974;100:79–84. [PMID: 4851849] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sidhu RS, Sharma A, Paterson ID, et al. Influenza H1N1 infection leading to cardiac tamponade in a previously healthy patient: a case report. Res Cardiovasc Med. 2016;5:e31546. [PMID: 27800452] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pandey Y, Hasan R, Joshi KP, et al. Acute influenza infection presenting with cardiac tamponade: a case report and review of literature. Perm J. 2019;23:18–104. [PMID: 30624200] doi: 10.7812/TPP/18-104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chaves SS, Lynfield R, Lindegren ML, et al. The US Influenza Hospitalization Surveillance Network. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:1543–50. [PMID: 26291121] doi: 10.3201/eid2109.141912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. FluView Interactive. 2020. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/fluviewinteractive.htm on 9 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rolfes MA, Foppa IM, Garg S, et al. Annual estimates of the burden of seasonal influenza in the United States: a tool for strengthening influenza surveillance and preparedness. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2018;12:132–137. [PMID: 29446233] doi: 10.1111/irv.12486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Disease burden of influenza. 2020. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/flu/about/burden/index.html on 20 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shakir R, Norrving B. Stroke in ICD-11: the end of a long exile [Letter]. Lancet. 2017;389:2373. [PMID: 28635606] doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31567-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shakir R The struggle for stroke reclassification. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018;14:447–448. [PMID: 29959393] doi: 10.1038/s41582-018-0036-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chow EJ, Rolfes MA, O’Halloran A, et al. Respiratory and non-respiratory diagnoses associated with influenza in hospitalized adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e201323. [PMID: 32196103] doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.1323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muller CJ, MacLehose RF. Estimating predicted probabilities from logistic regression: different methods correspond to different target populations. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:962–70. [PMID: 24603316] doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muñoz P, Vicent L, Bouza E, et al. Prognostic implications of influenza virus infection in a cardiac intensive care unit: potential impact of a screening program. Cardiology. 2019;143:85–91. [PMID: 31514195] doi: 10.1159/000501230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Warren-Gash C, Bhaskaran K, Hayward A, et al. Circulating influenza virus, climatic factors, and acute myocardial infarction: a time series study in England and Wales and Hong Kong. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:1710–8. [PMID: 21606529] doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heidenreich PA, Trogdon JG, Khavjou OA, et al. ; American Heart Association Advocacy Coordinating Committee. Forecasting the future of cardiovascular disease in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:933–44. [PMID: 21262990] doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31820a55f5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arriola C, Garg S, Anderson EJ, et al. Influenza vaccination modifies disease severity among community-dwelling adults hospitalized with influenza. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65:1289–1297. [PMID: 28525597] doi: 10.1093/cid/cix468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thompson MG, Pierse N, Sue Huang Q, et al. ; SHIVERS investigation team. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in preventing influenza-associated intensive care admissions and attenuating severe disease among adults in New Zealand 2012-2015. Vaccine. 2018;36:5916–5925. [PMID: 30077480] doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.07.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dobson J, Whitley RJ, Pocock S, et al. Oseltamivir treatment for influenza in adults: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2015;385:1729–1737. [PMID: 25640810] doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62449-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Butler CC, van der Velden AW, Bongard E, et al. Oseltamivir plus usual care versus usual care for influenza-like illness in primary care: an open-label, pragmatic, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2020; 395:42–52. [PMID: 31839279] doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32982-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Flu vaccination coverage, United States, 2018–19 influenza season. 26 September 2019. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/coverage-1819estimates.htm on 17 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Udell JA, Zawi R, Bhatt DL, et al. Association between influenza vaccination and cardiovascular outcomes in high-risk patients: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2013;310:1711–20. [PMID: 24150467] doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.279206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vardeny O, Claggett B, Udell JA, et al. ; PARADIGM-HF Investigators. Influenza vaccination in patients with chronic heart failure: the PARADIGM-HF trial. JACC Heart Fail. 2016;4:152–158. [PMID: 26746371] doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2015.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nichol KL, Nordin J, Mullooly J, et al. Influenza vaccination and reduction in hospitalizations for cardiac disease and stroke among the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1322–32. [PMID: 12672859] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.MacIntyre CR, Mahimbo A, Moa AM, et al. Influenza vaccine as a coronary intervention for prevention of myocardial infarction. Heart. 2016;102:1953–1956. [PMID: 27686519] doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2016-309983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muthuri SG, Venkatesan S, Myles PR, et al. ; PRIDE Consortium Investigators. Effectiveness of neuraminidase inhibitors in reducing mortality in patients admitted to hospital with influenza A H1N1pdm09 virus infection: a meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2:395–404. [PMID: 24815805] doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70041-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Muthuri SG, Myles PR, Venkatesan S, et al. Impact of neuraminidase inhibitor treatment on outcomes of public health importance during the 2009-2010 influenza A(H1N1) pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis in hospitalized patients. J Infect Dis. 2013;207:553–63. [PMID: 23204175] doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hsu J, Santesso N, Mustafa R, et al. Antivirals for treatment of influenza: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:512–24. [PMID: 22371849] doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-7-201204030-00411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mittleman MA, Mostofsky E. Physical, psychological and chemical triggers of acute cardiovascular events: preventive strategies. Circulation. 2011;124:346–54. [PMID: 21768552] doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.968776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Influenza Warren-Gash C. and ischaemic heart disease: research challenges and future directions [Editorial]. Heart. 2013;99:1795–6. [PMID: 24150664] doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-304748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koupenova M, Corkrey HA, Vitseva O, et al. The role of platelets in mediating a response to human influenza infection. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1780. [PMID: 30992428] doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09607-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harris JE, Shah PJ, Korimilli V, et al. Frequency of troponin elevations in patients with influenza infection during the 2017-2018 influenza season. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. 2019;22:145–147. [PMID: 30740511] doi: 10.1016/j.ijcha.2018.12.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kaji M, Kuno H, Turu T, et al. Elevated serum myosin light chain I in influenza patients. Intern Med. 2001;40:594–7. [PMID: 11506298] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Panhwar MS, Kalra A, Gupta T, et al. Effect of influenza on outcomes in patients with heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2019;7:112–117. [PMID: 30611718] doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2018.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Panhwar MS, Kalra A, Gupta T, et al. Relation of concomitant heart failure to outcomes in patients hospitalized with influenza. Am J Cardiol. 2019;123:1478–1480. [PMID: 30819433] doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2019.01.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sun Z, Chen C, Xu D, et al. Effects of ambient temperature on myocardial infarction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Pollut. 2018;241:1106–1114. [PMID: 30029319] doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.06.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bhaskaran K, Hajat S, Haines A, et al. Effects of ambient temperature on the incidence of myocardial infarction. Heart. 2009;95:1760–9. [PMID: 19635724] doi: 10.1136/hrt.2009.175000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vardeny O, Solomon SD. Influenza and heart failure: a catchy comorbid combination [Editorial]. JACC Heart Fail. 2019;7:118–120. [PMID: 30611719] doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2018.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kytömaa S, Hegde S, Claggett B, et al. Association of influenza-like illness activity with hospitalizations for heart failure: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4:363–369. [PMID: 30916717] doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.0549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ang LW, Yap J, Lee V, et al. Influenza-associated hospitalizations for cardiovascular diseases in the tropics. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;186:202–209. [PMID: 28338806] doi: 10.1093/aje/kwx001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Uyeki TM, Bernstein HH, Bradley JS, et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America: 2018 update on diagnosis, treatment, chemoprophylaxis, and institutional outbreak management of seasonal influenza. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68:e1–e47. [PMID: 30566567] doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Blackburn R, Zhao H, Pebody R, et al. Laboratory-confirmed respiratory infections as predictors of hospital admission for myocardial infarction and stroke: time-series analysis of English data for 2004-2015. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67:8–17. [PMID: 29324996] doi: 10.1093/cid/cix1144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Talbot HK. Influenza in older adults. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2017;31:757–766. [PMID: 28911829] doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2017.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lavie CJ, Carbone S, Agarwal MA. An obesity paradox with myocardial infarction in the elderly [Editorial]. Nutrition. 2018;46:122–123. [PMID: 29029870] doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2017.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lavie CJ, McAuley PA, Church TS, et al. Obesity and cardiovascular diseases: implications regarding fitness, fatness, and severity in the obesity paradox. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:1345–54. [PMID: 24530666] doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.01.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.De Schutter A, Kachur S, Lavie CJ, et al. The impact of inflammation on the obesity paradox in coronary heart disease. Int J Obes (Lond). 2016;40:1730–1735. [PMID: 27453423] doi: 10.1038/ijo.2016.125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vejpongsa P, Kitkungvan D, Madjid M, et al. Outcomes of acute myocardial infarction in patients with influenza and other viral respiratory infections. Am J Med. 2019;132:1173–1181. [PMID: 31145880] doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hartman L, Zhu Y, Edwards KM, et al. Underdiagnosis of influenza virus infection in hospitalized older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66:467–472. [PMID: 29341100] doi: 10.1111/jgs.15298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Babcock HM, Merz LR, Fraser VJ. Is influenza an influenza-like illness? Clinical presentation of influenza in hospitalized patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2006;27:266–70. [PMID: 16532414] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cole SR, Platt RW, Schisterman EF, et al. Illustrating bias due to conditioning on a collider. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39:417–20. [PMID: 19926667] doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.O’Malley KJ, Cook KF, Price MD, et al. Measuring diagnoses: ICD code accuracy. Health Serv Res. 2005;40:1620–39. [PMID: 16178999] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]