Abstract

By analogy to the revolution the “home glucose monitor” created in the treatment of diabetes, the availability of a modular, “platform” technology able to measure nearly any metabolite, biomarker, or drug “at-home” in unprocessed, finger-prick volumes of whole blood could revolutionize the monitoring and treatment of disease. Thus motivated, we have adapted here the electrochemical aptamer-based sensing platform to the problem of rapidly and conveniently measuring the level of phenylalanine in the blood, an ability that would aid the monitoring and management of phenylketonuria (PKU). To achieve this, we exploited a previously reported DNA aptamer that recognizes phenylalanine in complex with a rhodium-based “receptor” that improves affinity. We re-engineered this to undergo a large-scale, binding-induced conformational change before modifying it with a methylene blue redox reporter and attaching it to a gold electrode that supports the appropriate electrochemical interrogation. The resultant sensor achieves a useful dynamic range of 90 nM to 7 μM. When challenged with finger-prick-scale sample volumes of the whole blood (diluted 1000-fold to match the sensor’s dynamic range), the device achieves the accurate (±20%), calibration-free measurement of blood phenylalanine levels in minutes.

Keywords: aptasensor, personalized medicine, E-AB sensors, amino acid, metabolite, therapeutic drug monitoring

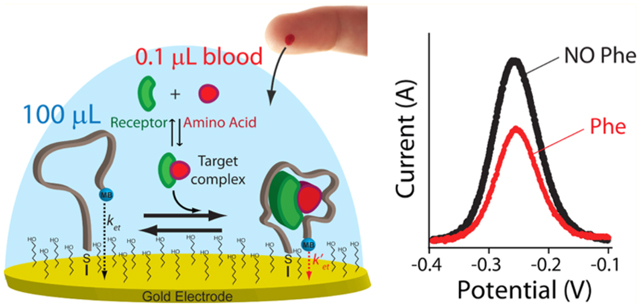

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

As thehome glucose monitor revolutionized the treatment of diabetes,1,2 the availability of a general platform able to measure drugs, metabolites, and biomarkers indicative of a disease “at-home” in unprocessed, easily collected clinical samples could revolutionize personalized medicine by enhancing the ease and frequency with which we can monitor health and treatment status.3,4 Other than for glucose, however, such point-of-care (PoC) molecular testing is largely restricted to lateral-flow dipstick tests,5 an approach that has proven difficult to adapt to quantitative measurements.6,7 Specifically, despite a long history of academic efforts to develop quantitative PoC devices, no commercially viable lateral flow has yet been achieved for the quantitative measurement of drug or metabolite levels in whole blood.8

In response to the potentially great promise of rapid, convenient, quantitative molecular testing, we have been developing electrochemical aptamer-based (E-AB) sensors,9,10 a platform technology that employs aptamers as its recognition elements, rendering the approach generalizable to any of a wide range of targets.11 In an E-AB sensor, the target-recognizing aptamer is attached via one end to a gold electrode and modified on the other with a redox reporter [here methylene blue (MB)] (Figure 1A).11 A binding-induced change in the aptamer’s conformation alters, in turn, the efficiency with which the redox reporter transfers electrons to the electrode, producing an easily measured signal when the sensor is interrogated electrochemically. This conformation-linked signal transduction mechanism renders the platform quite insensitive to nonspecific adsorption; enough so that E-AB sensors can even be deployed directly in biological fluids (either in vitro or in vivo) for many hours.12–16 Further speaking to their convenience, E-AB sensors are rapid (often reaching effective equilibrium in seconds) and can be made calibration-free.17

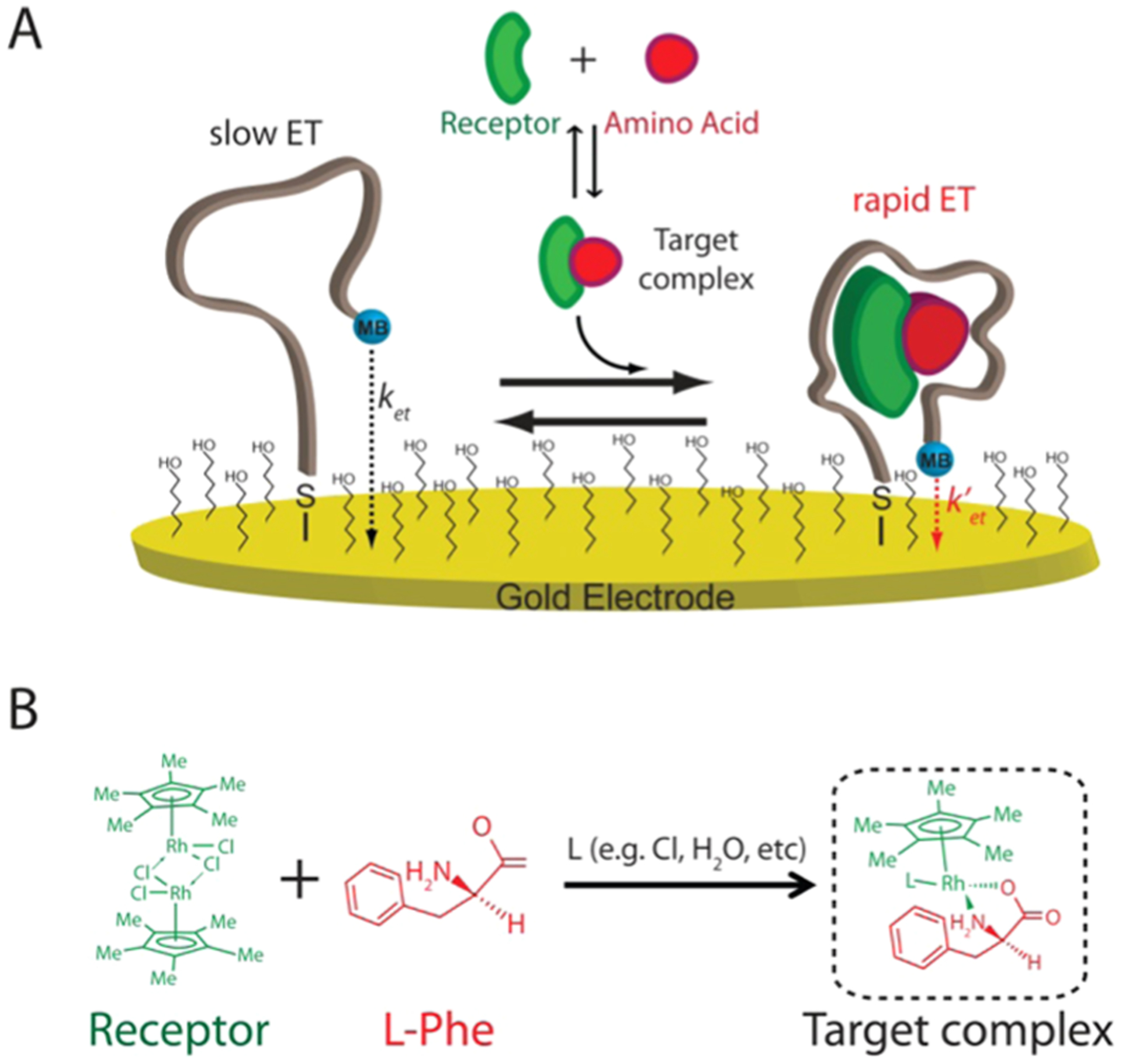

Figure 1.

Electrochemical aptamer-based (E-AB) sensor supporting the measurement of phenylalanine. (A) E-AB sensors employ an electrode-bound (via an alkane–thiol self-assembled monolayer), redox-reporter-modified aptamer that undergoes a conformational change in the presence of its target. Specifically, binding to the phenylalanine–rhodium complex alters the kinetics with which the reporter (here methylene blue, MB) exchanges electrons with the electrode surface (ket). This produces a target-dependent change in current that can be measured via different electrochemical methods, such as square-wave voltammetry (SWV), that are sensitive to changes in electron-transfer kinetics. (B) Structure of the rhodium-based receptor [(Cp*RhCl2)2] (green) that in solution can interact with phenylalanine (red) and other nucleophilic ligands present in solution (L) forming the complex target recognized by the aptamer.18

Given the above attributes, we were motivated to adopt the E-AB platform to the clinical need for convenient, at-home measurement of phenylalanine in the blood for use in monitoring and managing phenylketonuria (PKU), a relatively common (1 in 10 000 live births in Europe and 1 in 15.000 in the U.S.) inborn error of metabolism.19 The treatment of PKU requires a tailored nutritional regime, the goal of which is to maintain phenylalanine levels below certain threshold values via the restriction of dietary intake of the amino acid.19,18,20,21 The ability to measure such phenylalanine levels rapidly and conveniently would provide a direct means of monitoring the effectiveness of such treatment, improving both efficacy and patient quality of life.20–22 Specifically, a phenylalanine-measuring technology analogous to the home glucose monitor could prove a valuable adjunct in efforts to keep phenylalanine levels within the three critical clinical windows: (1) the 120–360 μM ideal range for children, which ensures sufficient biosynthesis of neurotransmitters while preventing the mental retardation associated with hyperphenylalaninemia; (2) a 360 μM maximum threshold for pregnant women to prevent fetal injury; and (3) a 600 μM maximum threshold that adults should remain below.8,19,18 Unlike the situation for diabetics, however, there is no analogous approach by which PKU patients can measure their own phenylalanine levels.8,18 In response, we describe here the fabrication and characterization of an E-AB sensor (Figure 1A) supporting the rapid (minutes), two-step (dilute-and-measure; calibration-free), and cost-effective (e.g., using screen-printed electrodes) measurement of clinically relevant phenylalanine levels in finger-prick-scale volumes of the diluted but otherwise unprocessed blood.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials.

Reagent-grade chemicals, including sodium hydroxide, sulfuric acid, 6-mercapto-1-hexanol, sodium chloride, ethanol, 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), tris(2-carboxyethyl)-phosphine (TCEP), tris[hydroxymethyl]-aminomethane hydrochloride, magnesium chloride, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), potassium chloride, pentamethylcyclopentadienyl rhodium-(III) chloride dimer, l-phenylalanine, l-tryptophan, l-tyrosine, l-glutamine, l-histidine, l-arginine, l-alanine, and sodium phosphate monobasic (all from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri) were used as received. Human blood was purchased from BioIVT (San Francisco, California). Gold screen-printed electrodes (ref PW-AU10) were purchased from DropSens (Llanera, Spain).

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)-purified oligonucleotides were purchased from Biosearch Technologies (Novato, CA). The aptamer variants were modified with a thiol-C6-SS-C6 group at its 5′ end and a methylene blue attached by a six-carbon linker to an amine at its 3′ end. The oligonucleotides were dissolved in buffer (100 mM Tris buffer, 10 mM MgCl2, pH 7.8) at a concentration of 100 μM and then aliquot and stored at −20 °C. The final concentration of the oligonucleotides was confirmed using a Beckman Coulter DU 800 UV–vis spectrophotometer (Männedorf, Switzerland) using a 100 μL quartz cuvette and measuring the relative absorbance at 260 nm.

The aptamer sequences we employed were a truncated version of a previously reported aptamer against this target:18

Trunc 1: 5′-GACGA CGGAC GCTAAT CTTAC AAGGG CGTAG TGTAT GTCGT C-3′

Trunc 2: 5′-GACGG ACGCT AATCT TACAA GGGCG TAGTG TATGT C-3′

Trunc 3: 5′-GGACG CTAAT CTTAC AAGGG CGTAG TGTAT −3′

NUPACK Simulations.

We used NUPACK (www.nupack.org/)23 to predict the folding free energies of the stem portion for the original aptamer and the truncated variants (Figure S1). The aptamer sequences were analyzed by the software using the following parameters: (a) temperature: 25 °C; (b) number of strand species: 1; (c) maximum complex size: 4; (d) oligo concentration = 500 nM; in advanced options; (e) [Na+] = 1 M, [Mg2+] = 0.01 M; and (f) dangle treatment: some.

Sensor Fabrication on Gold-Disk Electrodes.

The E-AB sensors were fabricated using an established approach (Figures 2–4, S2, S5, S7, and S9).24 Briefly, E-AB sensors were fabricated on gold-disk electrodes (3.0 mm diameter, BAS, West Lafayette, IN). These were prepared by polishing on a micro cloth pad soaked before with a 1 μm diamond suspension slurry (MetaDi, Buehler, Lake Bluff, IL) and then with a 0.05 μm alumina powder aqueous suspension. Each polishing step is followed by sonication of the electrodes in a solution 1:1 water/ethanol for 5 min. The electrodes were then electrochemically cleaned using the following procedure: (a) The electrodes are placed in a 0.5 M NaOH solution and through cyclic voltammetry 1000–2000 scans are performed using a potential between −0.4 and −1.35 V versus Ag/AgCl at a scan rate of 2 V s−1; (b) The electrodes were moved to a 0.5 M H2SO4 solution, and, using chronocoulometry, an oxidizing potential of 2 V was applied for 5 s, followed by a reducing potential of −0.35 V for 10 s; (c) Using cyclic voltammetry, we cycled the electrodes rapidly (4 V s−1) in the same solution between −0.35 and 1.5 V for 10 scans followed by two cycles recorded at 0.1 V s−1 using the same potential window.

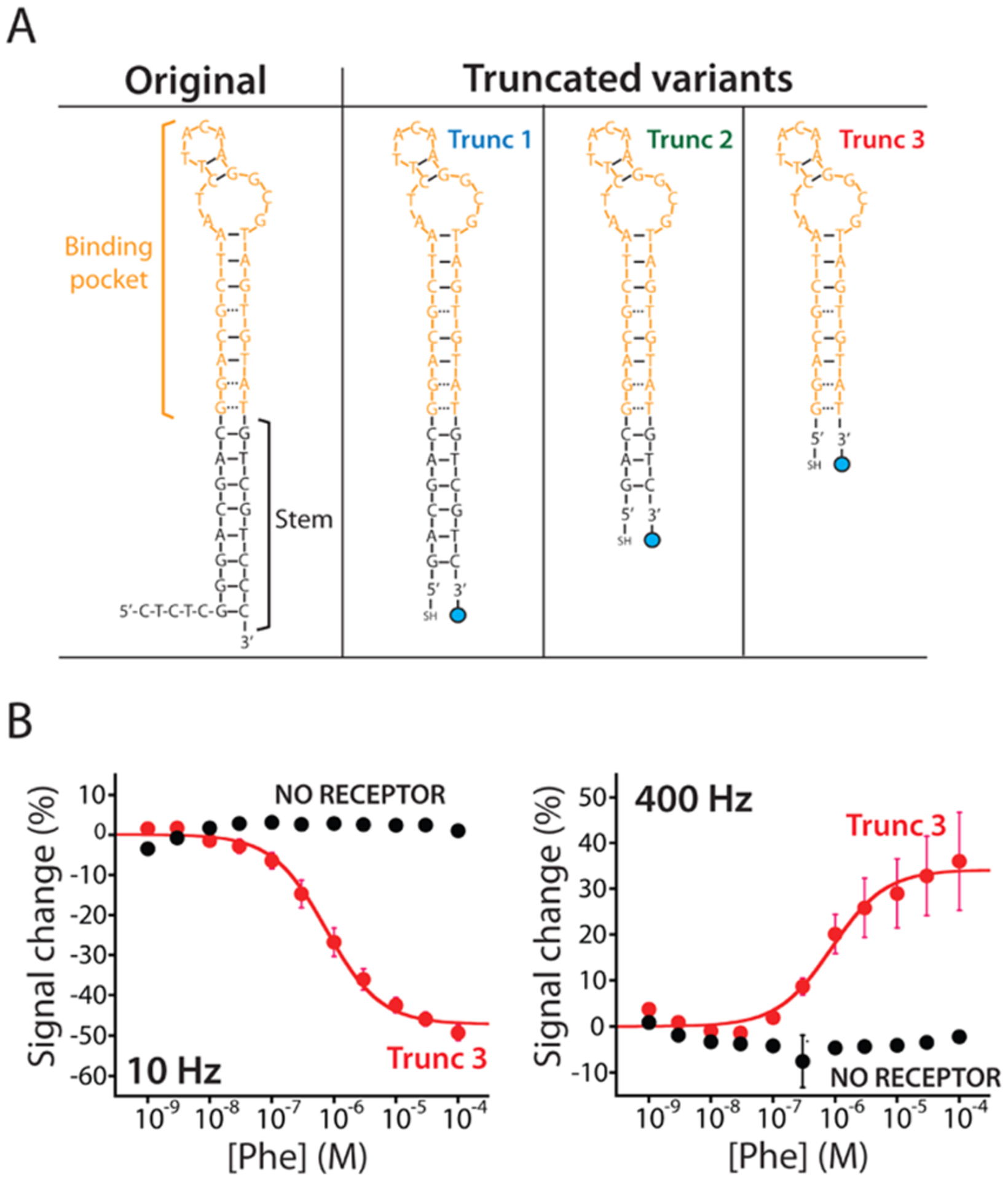

Figure 2.

Re-engineered E-AB sensors promptly respond to phenylalanine. (A) To adapt the original aptamer to the E-AB sensing platform, we re-engineered its sequence. We did so by truncating its stem portion (black) to destabilize its structure. This destabilization induces the aptamer to populate a more open or unfolded state in the absence of the complex target producing a larger conformational change during the binding and, thus, a larger current signal change. (B) Trunc 3 E-AB sensor displays the higher signal gain (Figure S2) and responds to phenylalanine only in the presence (red curve) of the rhodium-based receptor. When the sensor is interrogated at responsive square-wave frequencies (10 and 400 Hz) in the presence of increasing concentrations of the target (at a fixed 100 μM concentration of the rhodium receptor), it produces two well-defined Langmuir isotherms with identical (within experimental uncertainties) dissociation constants (KD) of 745 ± 94 nM (left) and 883 ± 212 nM (right), respectively.

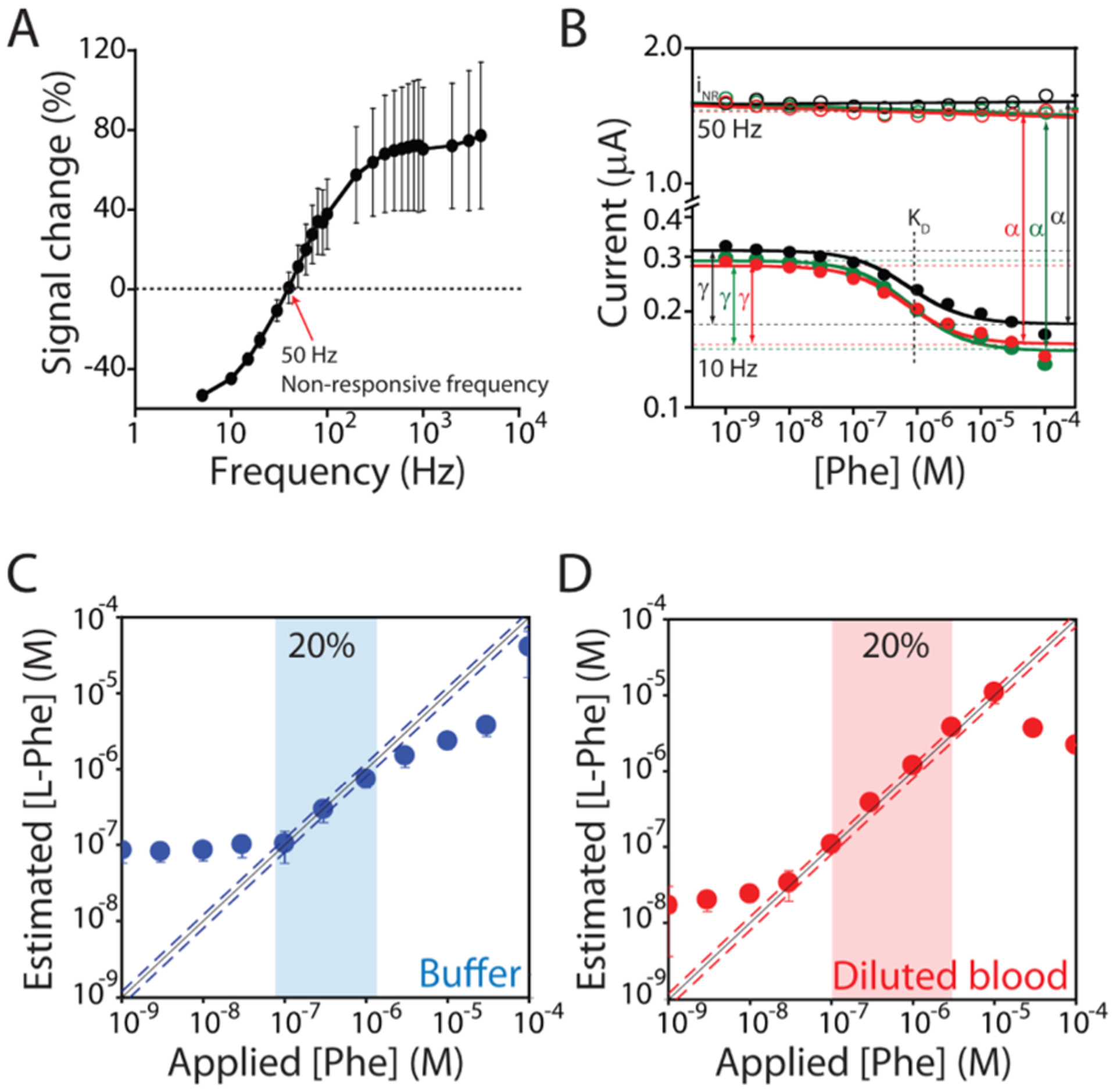

Figure 4.

E-AB sensors can support calibration-free measurements exploiting the voltammetric signal from a “nonresponsive” square-wave frequency.17 (A) The signal gain of our E-AB sensor is dependent on the frequency of the interrogating SWV potential pulse (Figure S2).25,26 This dependence is enough strong that there is a specific frequency (50 Hz) at which the sensor does not respond to phenylalanine. (B) We choose this frequency (50 Hz) as non-responsive, and as expected, the voltammetric signal, iNR, is constant irrespective of the target concentration. Instead, as the responsive frequency, we choose 10 Hz, at which the voltammetric signal, i, is strongly dependent on the concentration of phenylalanine. Using these two voltammetric signals, we can estimate the dissociation constant (KD), the relative signal gain (γ), and the proportionality constant (α) that relates iNR to the current i that would be measured in the absence of the target at the responsive frequency. These three parameters are constant for all sensors in the same class. (C, D) Shown are phenylalanine-detecting sensors interrogated in the buffer and diluted (1:1000) whole blood, respectively. Under the former conditions, we achieved excellent accuracy within ±20% over the range of 0.1–1 μM (blue dashed line). Under the latter conditions, these sensors display high accuracy, achieving accuracy within ±20% (red dashed line) over the range of 0.1–10 μM, which (when accounting for the dilution factor) covers the entire clinical range from 100 μM to 10 mM.

We first reduced the probe DNA (100 μM) by treating it for 1 h in a solution of 10 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)-phosphine hydrochloride in the dark. This was then dissolved in “assembly buffer” (10 mM Na2HPO4 with 1 M NaCl and 1 mM MgCl2 at pH 7.3) at a final concentration of 500 nM. The electrochemically cleaned gold electrodes were then immersed in 200 μL of this solution for 1 h in the dark. Following this, the electrode surface was rinsed with distilled water and incubated overnight at 4 °C in assembly buffer containing 5 mM 6-mercaptohexanol, followed by a further rinse with distilled water before use.

Sensor Fabrication on Screen-Printed Gold Electrodes.

The gold screen-printed electrodes are emplaced on a flexible plastic substrate of dimensions 33 × 10 × 0.175 mm3. The working (4 mm diameter) electrode is made of gold, the counter electrode is made of carbon, and the reference electrode and the electric contacts are made of silver. We limited the cleaning of screen-printed gold electrodes to electrochemical cleaning (Figure 5). For this, we first performed a series of cyclic voltammetry in 0.5 M H2SO4 scanning from 0 to +1.5 V (scanning every 1 mV with a scan rate of 1 V s−1) until the gold peak was stable (approximately 20 scans). Then, after carefully rinsing with deionized (DI) water, we dried them without touching the gold surface. We then deposited a 100 μL drop of the 500 nM DNA probe (previously reduced with TCEP using the same procedure described for gold-disk electrodes) onto the dry electrodes and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. To prevent the evaporation of the solution, we placed the electrodes inside a Petri dish with a wet piece of paper to maintain humidity. After a final rinse with DI water (to remove the loosely adsorbed DNA), we incubated the electrodes in the assembly buffer with 5 mM 6-mercaptohexanol overnight at 4 °C.

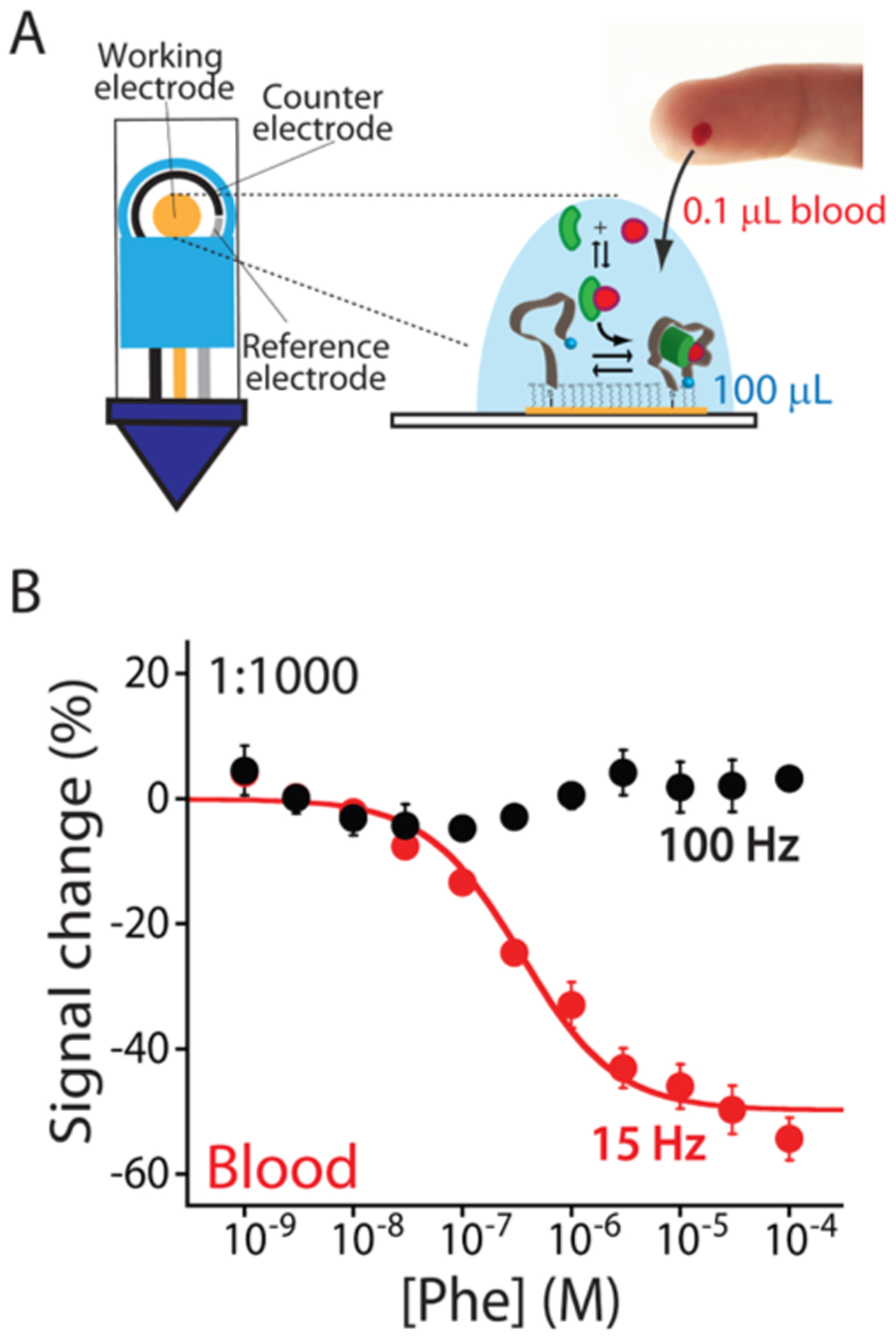

Figure 5.

E-AB sensors can fully support the strip-based technology demonstrating all of their potentials to perform at-home measurements. (A) We used screen-printed electrodes to fabricate our sensors. Specifically, the working (4 mm diameter) electrode is made of gold, the counter electrode is made of carbon, and the reference electrode is made of silver. The small dimensions of these sensors allow us to measure phenylalanine concentrations using a total volume of 100 μL and only 0.1 μL of the blood sample (less of a blood finger prick). (B) Testing our sensor in diluted human blood (1:1000), we can detect phenylalanine in its clinical range with a maximum signal gain of −49.7 ± 2.4% and an estimated KD of 0.4 ± 0.1 μM. Again, our E-AB sensors fabricated using screen-printed electrodes maintain a nonresponsive frequency at 100 Hz.

Sensor Testing.

We performed our electrochemical measurements at room temperature using a CHI660D potentiostat with a CHI684 Multiplexer (CH Instruments, Austin, TX) and a standard three-electrode cell containing a platinum counter electrode and a Ag/AgCl (3 M KCl) reference electrode. Square wave voltammetry (SWV) was performed using a potential window of −0.1 to −0.45 V, using an amplitude of 50 mV and a potential step of 1 mV for frequencies above 50 Hz and a potential step of 3 mV for frequencies below 50 Hz.

Experimental titration curves (Figures 2B, 3, and 4, S5 and S7) were performed in 10 mL of the working buffer (20 mM HEPES, 1 M NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM KCl, pH 7.5) using three or six E-AB sensors modified with the oligonucleotide probe and using responsive SWV frequencies of 10 and 400 Hz and nonresponsive frequencies of 50 and 120 Hz. Initially, in the absence of target and rhodium-based receptors, we performed a preliminary treatment by interrogating the electrodes with 40–80 scans until stable current peaks were obtained. Once the sensor’s signal was stable, the desired rhodium-based receptor concentration was added to the solution to reach the final concentration of 100 μM.18 The rhodium-based receptor was dissolved in DI water at a concentration of 6 mM. Then, increasing concentrations of the target were added, and the sensors were interrogated after 10 min. The titration curves in Figures 4 and S7 were performed using the same experimental approach but adding the appropriate volume of human blood (10 μL) to achieve the desired 1:1000 dilution factor.

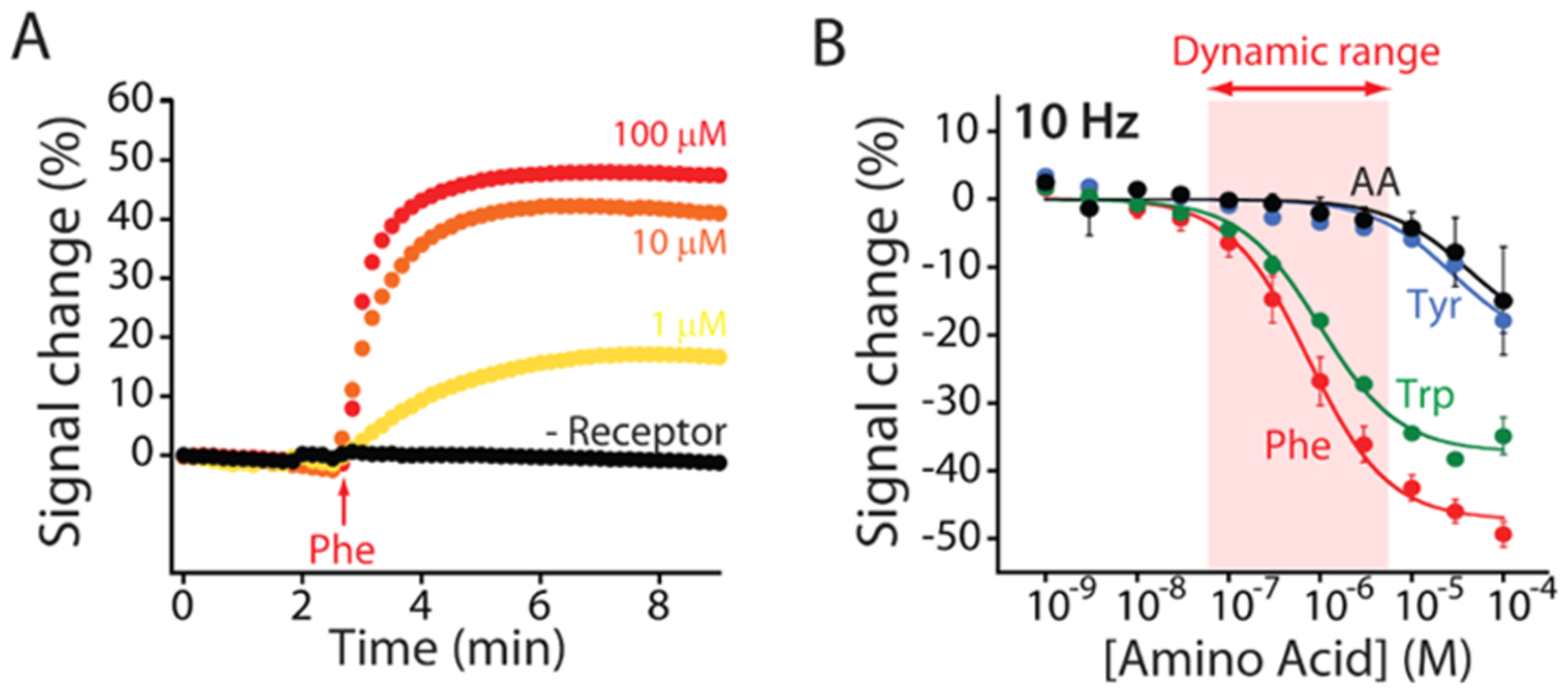

Figure 3.

Phenylalanine-detecting E-AB sensor is rapid, quantitative, and specific. (A) The sensor responds with a time constant of less than 1 min at physiological (i.e., above 120 μM) concentrations. (B) The sensor achieves clinically relevant specificity. e.g., when it is tested against either tyrosine or a mix of five amino acids (glutamine, histidine, proline, arginine, and alanine), it does not produce a detectable signal change until the concentration rises above 10 μM. In contrast, the sensor does cross-react with tryptophan. Given, however, the physiological levels of this amino acid and the 1:1000 dilution, we employ no interference from tryptophan is expected.

Experimental titration curves using gold screen-printed electrodes (Figure 5) were performed in a final volume of 100 μL, containing the human blood diluted 1000× in the working buffer (20 mM HEPES, 1 M NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM KCl, pH 7.5) and using three E-AB sensors modified with the oligonucleotide probe and a responsive SWV frequency of 15 Hz. Initially, in the absence of target and rhodium-based receptors, we performed a preliminary treatment by interrogating the electrodes with 20–40 scans until stable peaks were obtained. Once the signal was stable, the solution was removed, and the working buffer with the blood and the desired rhodium-based receptor concentration (100 μM) were added.18 We then added increasing concentrations of the target and interrogated the sensor after 10 min.

The peak current for each sensor at each concentration of the target was extracted by subtracting the baseline current from the peak maxima (ITarget). The resultant data were fitted using a Langmuir equation (single-site binding)27 in KaleidaGraph (Synergy Software)

| (1) |

Here, [Phe] is the target concentration, ITarget is the raw signal current in the presence of the target, I0 is the background raw current seen in the absence of the target, IMax is the raw current signal change seen at the saturating target, and KD is the dissociation constant of the surface-bound aptamer.

Using the I0 estimated from the fit, we converted the raw signaling current of each sensor into relative signal change (I%) using the following equation

| (2) |

We determined the frequency dependence of the sensor’s signal gain (relative signal change upon challenge with the saturating target; Figure S2) by interrogating three sensors in the presence (100 μM) of the rhodium-based receptor and either no target or saturating phenylalanine (100 μM). The collected peak currents were converted in signal gain using eq 2, where I0 corresponds to the current in the absence of the target.25,26 Using the same data set, we estimated the electron-transfer rate associated with all three variants in the absence and in the presence of phenylalanine (Figure S4).25,26 Finally, we selected the aptamer constructs and frequencies that produced a better combination of signal gain and affinity.

Control experiments indicate that the rhodium receptor does not produce any measurable interference over the potential window employed (Figure S3). To show this, we employed gold-disk electrodes in 10 mL of the working buffer (20 mM HEPES, 1 M NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM KCl, pH 7.5), and we selected responsive SWV frequencies of 10 and 400 Hz. We cleaned the electrodes following the previously described approach, and then we immersed them in 200 μL of 5 mM 6-mercaptohexanol and incubated overnight at 4 °C, followed by a further rinse with distilled water before use. We interrogated the electrodes in the presence (100 μM) and in the absence of the rhodium receptor using a potential window of −0.1 to −0.45 V and detected no relevant signal from the rhodium receptor (Figure S3).

We determined the sensor’s equilibration time (Figure 3A) using the above experimental approach and interrogating the sensor every 10 s in the working buffer using 400 Hz as the responsive square-wave frequency. After we achieved a stable current baseline in the presence (100 μM) or in the absence of the rhodium-based receptor, we added the target to the solution and then we monitored the voltammetric signal for over 15 min. The observed signal change was fitted to a single exponential decay in KaleidaGraph (Synergy Software) to obtain the equilibration time constant of the sensor.

To determine the sensor parameters supporting calibration-free measurements, we performed data analysis using in-house built Matlab Scripts to simultaneously fit data from all of the electrodes in a given training set to eq 3 to obtain the optimized parameters α, γ, and KD (Figures S5 and S7).17 The least-square errors in the fittings were propagated by Monte Carlo analysis (10 000 steps) to provide a distribution of the variability in the calculated parameters α, γ, and KD (Figures S6 and S8), which we then applied to a separate test set of electrodes.17

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

As the aptamer in our phenylalanine-detecting E-AB sensor, we employed a previously reported18 DNA sequence that recognizes a supramolecular complex between phenylalanine and a rhodium-based receptor, pentamethylcyclopentadienyl rhodium(III). The latter, which binds all amino acids, is used to enhance their “epitope” complexity, thus improving affinity (Figure 1B). We re-engineered this aptamer to undergo a large-scale conformational change via truncation of its double-stranded terminal stem (Figure 2A), with the expectation that the resultant destabilization would lead to binding-induced folding.28,29 Using the nucleic acid folding predictor NUPACK23 to estimate their folding thermodynamics, we designed three truncates (trunc 1, trunc 2, and trunc 3) that are expected to decrease the stability of the aptamer from the −15.5 kJ/mol of the parent sequence to as low as −4.6 kJ/mol for trunc 3 (Figure S1). To support their incorporation into E-AB sensors, we modified each variant with a thiol group on its 5′ end (to anchor it to the gold electrode) and a methylene blue redox reporter on its 3′ end (Figure 2A).

E-AB sensors fabricated from all three aptamer variants respond to the target phenylalanine–Rh complex when interrogated using square-wave voltammetry (SWV) (Figure S2). Previous studies have indicated that the frequency of the interrogating SWV potential pulse alters both (1) the magnitude of the signal change observed upon target binding (signal gain) and (2) its sign (i.e., producing either signal-on or signal-off behavior).25,26 Testing our sensors in the presence of saturating (100 μM)18 phenylalanine–Rh complex and characterizing the sensors’ frequency response over square-wave frequencies ranging from 5 to 4000 Hz (Figure S2), we find that trunc 3 produces the highest gain of the three sequences (Figure S2).

To explore why this is true, we characterized the electron-transfer rate associated with all three variants in the absence or presence of Phe.25,26 In the absence of the target, the transfer rate of trunc 3 is slower than those of the other two variants (Figure S4) presumably because it is less stable and, thus, better populates the expanded, unfolded state, pushing the redox reporter farther from the electrode surface.30 In the presence of the target (100 μM), in contrast, all three variants display the same electron-transfer rate presumably because they all adopt the same conformation when target-bound (Figure S4). Moving forward, we thus focused our efforts on sensors employing the trunc 3 variant.

The trunc 3 E-AB sensor provides a convenient tool for measuring phenylalanine. For example, observing the voltammetric signal of the E-AB sensor in the presence of increasing concentrations of phenylalanine and a fixed (100 μM) concentration of the rhodium receptor, we observe Langmuir isotherm binding curves at all square-wave frequencies tested (Figure 2B). At 10 Hz, for example, the sensor displays signal-off behavior with a maximum signal gain of −47.3 ± 1.2% and an estimated dissociation constant (KD) of 750 ± 90 nM (unless otherwise noted, the confidence intervals reported here and elsewhere in this paper reflect standard deviations, to illustrate sensor-to-sensor variability, derived using at least three independently fabricated sensors). From this titration, we see that the sensor’s useful dynamic range (defined here as the range from 10 to 90% of the maximum signal change) is from 90 nM to 7 μM. In the absence of the rhodium receptor, in contrast, the sensor does not measurably respond to phenylalanine even at the highest concentrations we have employed (Figure 2B, black curves).

The phenylalanine-detecting E-AB sensor is rapid and specific enough to support at-home measurements of phenylalanine levels in diluted blood samples. The sensor’s equilibration time constant, for example, is 1.7 ± 0.1 min when challenged with 1 μM phenylalanine (Figure 3A, yellow curve), a value easily rapid enough to support self-testing by patients. The sensor is also sufficiently specific to support clinically relevant phenylalanine measurements. It does not, for example, respond significantly when challenged with either 10 μM tyrosine or a mixture of 10 μM glutamine, histidine, proline, arginine, and alanine (Figure 3B, blue and black curves). The only amino acid for which we observed a similar response was tryptophan. The sensor’s limit of detection for tryptophan, however, is sufficiently high that no significant cross-reactivity is observed at physiological tryptophan levels. Specifically, the level of tryptophan in the blood does not exceed 90 μM in either healthy individuals or PKU patients.18,31 Given the 1:1000 dilution employed in our assay, the resultant 0.09 μM tryptophan concentration is far below the level at which this amino acid produces a measurable signal change from this phenylalanine-detecting sensor.

Sensor calibration has proven a major hurdle limiting the transition of biosensors from the laboratory to at-home use.32,33 Specifically, the need for the end-user to calibrate each individual sensor increases the number of operations required, which decreases ease of use and provides an additional opportunity for mistakes34,35 that can negatively affect outcomes.36 Given this, elimination of the need to calibrate could significantly advance at-home use.37 To achieve this, we have employed a previously described “dual-frequency” interrogation approach17 in which the parameters necessary to convert the sensor’s raw output into a quantitative measurement of concentration are determined a single time for all sensors in the class and then employed for all future sensors in that same class.

The dual-frequency calibration-free approach exploits the observation that as the sensor transitions from signal-on behavior (at higher square-wave frequencies) to signal-off behavior (at lower frequencies), it passes through a frequency at which its signal is entirely independent of the presence or absence of the target (Figure 4A). The output at this nonresponsive frequency, thus, provides a phenylalanine-concentration-independent reference that we can use to correct for sensor-to-sensor variability (e.g., variability in the absolute number of aptamers, and, thus, the current produced by the methylene blue reporters). Specifically, the concentration of the target is given by the relationship

| (3) |

where i is the peak current observed at a square-wave frequency at which the sensor responds to its target (here 10 Hz), iNR is the peak current observed at the nonresponsive frequency (50 or 120 Hz depending on the sample conditions), KD is the aptamer’s dissociation constant, γ is the relative signal gain (the ratio of the signal seen in the presence of the saturating target to that seen in the absence of the target), and α is the proportionality constant relating iNR to the signal that would be measured at the responsive frequency in the absence of the target. Because KD, γ, and α are constants for all E-AB sensors of a given class under a given set of measurement conditions (Figure 4B), these can be determined once for sensors in the class and then applied to all new sensors, abrogating the need to calibrate each individual device. The determination of target concentration, thus, depends only on i and iNR, which can be measured in situ in the sample, obviating the need for separate measurements employing calibration standards.

To perform calibration-free phenylalanine measurements in simple buffer solutions, we first determined KD, γ, and α for sensors in this class using a nonresponsive frequency of 50 Hz and a responsive frequency of 10 Hz (Figure 4B). To do so, we challenged a test set of six E-AB sensors against increasing concentrations of phenylalanine (with 100 μM of the rhodium receptor) and globally fit the resulting data to eq 3 (Figures S5 and S6). Applying the parameters derived from this set of sensors to sensors outside of the set, we were able to estimate phenylalanine concentrations with an accuracy of better than ±20% across the concentration range 0.1–1 μM (Figures 4C, S5, and S6).

While the above experiments were all performed in simple buffer solutions, the E-AB platform is sufficiently selective to perform measurements in more complex sample matrices (including even deployment directly in the living body12,13), thus suggesting that the platform can easily measure phenylalanine levels in the diluted whole blood. Given, however, that the useful dynamic range of the calibration-free sensor (0.1–1 μM) is far below the concentration of phenylalanine in the blood, dilution is required to match the expected and the measurable range. Conveniently, this dilution also provides an opportunity to introduce the necessary rhodium receptor. Moving to the 1:1000-diluted whole blood, we employed a new test set to redetermine KD, γ, and α (these are sensitive to sample conditions, Figures S7 and S8) using a nonresponsive frequency of 120 Hz and a responsive frequency of 10 Hz (Figure S9).17,25 Under these conditions, we obtained estimated phenylalanine concentrations accurate to within ±20% across a 0.1–10 μM (predilution) concentration range (Figure 4D), which nicely spans the clinically relevant concentrations of this amino acid.

All of the above experiments were conducted using 3 mm diameter gold-disk electrodes, necessitating sample volumes of order 1 mL. Screen-printed electrodes, in contrast, would be much better suited for at-home use as they are small and inexpensive.38,39 Thus motivated, we also fabricated and characterized sensors employing such electrodes and tested them with increasing concentrations of phenylalanine in a 100 μL volume of diluted human blood (1000× dilution, Figure 5). As expected, the screen-printed sensors maintained the analytical performance seen for disk electrodes, responding to their target (in the diluted whole blood) with a maximum signal gain of −49.7 ± 2.4% and a KD of 0.4 ± 0.1 μM (Figure 5B).

CONCLUSIONS

To support at-home testing, a sensor must achieve clinically acceptable specificity and accuracy and yet simultaneously be convenient, rapid, and inexpensive.3,4 Here, we demonstrate that an electrochemical E-AB sensor for the detection of phenylalanine can meet these demanding requirements. Specifically, the sensor displays clinically relevant accuracy (±20%) and specificity (nothing else in the blood interferes detectably) when challenged in diluted human blood. It is also rapid (<10 min), convenient (requires only finger-prick sample volumes diluted into a receptor-containing buffer), and calibration-free. Finally, it can be deployed on inexpensive, screen-printed electrodes without significant loss in performance. The ability to perform at-home measurements of this clinically important metabolite, much less of many other metabolites, biomarkers, and drugs, could significantly advance personalized medicine.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by Grant EB022015 from the National Institutes of Health and a grant from Aptakek, Inc. We thank Prof. Milan Stojanovic for his suggestions and helpful discussion of the manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): Prof. Kevin W. Plaxco has a financial interest in and serves on the scientific advisory boards of two companies attempting to com-mercialize E-AB sensors.

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acssensors.9b01703.

NUPACK simulations and sequences of the variants, characterization of signal gain as a function of SWV frequency, control experiments regarding the electro-chemistry of the rhodium receptor, characterization of the electron-transfer rates associated with all three variants, characterization of the parameters for calibration-free measurements, and demonstration of the effects of the blood on the sensor’s SWV frequency response (PDF)

REFERENCES

- (1).Clarke SF; Foster JR A history of blood glucose meters and their role in self-monitoring of diabetes mellitus. Br. J. Biomed. Sci 2012, 69, 83–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Montagnana M; Caputo M; Giavarina D; Lippi G Overview on self-monitoring of blood glucose. Clin. Chim. Acta 2009, 402, 7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Vashist SK; Luppa PB; Yeo LY; Ozcan A; Luong JHT Emerging Technologies for Next-Generation Point-of-Care Testing. Trends Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 692–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Luppa PB; Müller C; Schlichtiger A; Schlebusch H Point-of-care testing (POCT): Current techniques and future perspectives. TrAC, Trends Anal. Chem 2011, 30, 887–898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Syedmoradi L; Daneshpour M; Alvandipour M; Gomez FA; Hajghassem H; Omidfar K Point of care testing: The impact of nanotechnology. Biosens. Bioelectron 2017, 87, 373–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Miller BS; Parolo C; Turbé V; Keane CE; Gray ER; McKendry RA Quantifying Biomolecular Binding Constants using Video Paper Analytical Devices. Chem. – Eur. J 2018, 24, 9783–9787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Mak WC; Beni V; Turner APF Lateral-flow technology: From visual to instrumental. TrAC, Trends Anal. Chem 2016, 79, 297–305. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Yu Q; Xue L; Hiblot J; Griss R; Fabritz S; Roux C; Binz PA; Haas D; Okun JG; Johnsson K Semisynthetic sensor proteins enable metabolic assays at the point of care. Science 2018, 361, 1122–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Lai RY; Plaxco KW; Heeger AJ Aptamer-based electrochemical detection of picomolar platelet derived growth factor directly in blood serum. Anal. Chem 2007, 79, 229–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Xiao Y; Lubin AA; Heeger AJ; Plaxco KW Label-free electronic detection of thrombin in blood serum by using an aptamer-based sensor. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2005, 44, 5456–5459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Lubin AA; Plaxco KW Folding-based electrochemical biosensors: the case for responsive nucleic acid architectures. Acc. Chem. Res 2010, 43, 496–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Idili A; Arroyo-Currás N; Ploense KL; Csordas AT; Kuwahara M; Kippin TE; Plaxco KW Seconds-resolved pharmacokinetic measurements of the chemotherapeutic irinotecan in situ in the living body. Chem. Sci 2019, DOI: 10.1039/C9SC01495K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Arroyo-Currás N; Somerson J; Vieira PA; Ploense KL; Kippin TE; Plaxco KW Real-time measurement of small molecules directly in awake, ambulatory animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2017, 114, 645–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Li H; Somerson J; Xia F; Plaxco KW Electrochemical DNA-based sensors for molecular quality control: continuous, real-time melamine detection in flowing whole milk. Anal. Chem 2018, 90, 10641–10645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Somerson J; Plaxco KW Electrochemical aptamer-based sensors for rapid point-of-use monitoring of the mycotoxin ochratoxin a directly in a food stream. Molecules 2018, 23, No. E912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Swensen JS; Xiao Y; Ferguson BS; Lubin AA; Lai RY; Heeger AJ; Plaxco KW; Soh HT Continuous, real-time monitoring of cocaine in undiluted blood serum via a microfluidic, electrochemical aptamer-based sensor. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 4262–4266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Li H; Dauphin-Ducharme P; Ortega G; Plaxco KW Calibration-Free Electrochemical Biosensors Supporting Accurate Molecular Measurements Directly in Undiluted Whole Blood. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 11207–11213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Yang K-A; Barbu M; Halim M; Pallavi P; Kim B; Kolpashchikov DM; Pecic S; Taylor S; Worgall TS; Stojanovic MN Recognition and sensing of low-epitope targets via ternary complexes with oligonucleotides and synthetic receptors. Nat. Chem 2014, 6, 1003–1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Blau N; Van Spronsen FJ; Levy HL Phenylketonuria. Lancet 2010, 376, 1417–1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Camp KM; Lloyd-Puryear MA; Huntington KL Nutritional treatment for inborn errors of metabolism: Indications, regulations, and availability of medical foods and dietary supplements using phenylketonuria as an example. Mol. Genet. Metab 2012, 107, 3–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Walter JH; White FJ; Hall SK; MacDonald A; Rylance G; Boneh A; Francis DE; Shortland GJ; Schmidt M; Vail A How practical are recommendations for dietary control in phenylketonuria? Lancet 2002, 360, 55–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Goldstein A; Vockley J Clinical trials examining treatments for inborn errors of amino acid metabolism. Expert Opin. Orphan Drugs 2017, 5, 153–164. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Zadeh JN; Steenberg CD; Bois JS; Wolfe BR; Pierce MB; Khan AR; Dirks RM; Pierce NA NUPACK: Analysis and design of nucleic acid systems. J. Comput. Chem 2011, 32, 170–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Xiao Y; Lai RY; Plaxco KW Preparation of electrode-immobilized, redox-modified oligonucleotides for electrochemical DNA and aptamer-based sensing. Nat. Protoc 2007, 2, 2875–2880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).White RJ; Plaxco KW Exploiting binding-induced changes in probe flexibility for the optimization of electrochemical biosensors. Anal. Chem 2010, 82, 73–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Idili A; Amodio A; Vidonis M; Feinberg-Somerson J; Castronovo M; Ricci F Folding-upon-binding and signal-on electrochemical DNA sensor with high affinity and specificity. Anal. Chem 2014, 86, 9013–9019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Esteban Fernández de Ávila B; Watkins HM; Pingarrón JM; Plaxco KW; Palleschi G; Ricci F Determinants of the detection limit and specificity of surface-based biosensors. Anal. Chem 2013, 85, 6593–6597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).White RJ; Rowe AA; Plaxco KW Re-engineering aptamers to support reagentless, self-reporting electrochemical sensors. Analyst 2010, 135, 589–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Idili A; Gerson J; Parolo C; Kippin T; Plaxco KW An electrochemical aptamer-based sensor for the rapid and convenient measurement of l-tryptophan. Anal. Bioanal. Chem 2019, 411, 4629–4635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Dauphin-Ducharme P; Arroyo-Curras N; Adhikari R; Somerson J; Ortega G; Makarov DE; Plaxco KW Chain dynamics limit electron transfer from electrode-bound, single-stranded oligonucleotides. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 21441–21448. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Yarbro MT; Anderson JA l-Tryptophan metabolism in phenylketonuria. J. Pediatr 1966, 68, 895–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Acciaroli G; Vettoretti M; Facchinetti A; Sparacino G Calibration of minimally invasive continuos glucose monitoring sensors: state-of-the-art and current perspectives. Biosensors 2018, 8, 24–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Heller A; Feldman B Electrochemical glucose sensors and their applications in diabetes management. Chem. Rev 2008, 108, 2482–2505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Noble M; Rippeth J; Edington D; Rayman G; Brandon-Jones S; Hollowood Z; Kew S Clinical evaluation of a novel on-strip calibration method for blood glucose measurement. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol 2014, 8, 766–775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Lodwig V; Heinemann L Continuous glucose monitoring with glucose sensors: calibration and assessment criteria. Diabetes Technol. Ther 2003, 5, 572–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Parkes JL; Slatin SL; Pardo S; Ginsberg BH A new consensus error grid to evaluate the clinical significance of inaccuracies in the measurement of blood glucose. Diabetes Care 2000, 23, 1143–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Bakker E Can Calibration-Free Sensors Be Realized? ACS Sens. 2016, 1, 838–841. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Arduini F; Micheli L; Moscone D; Palleschi G; Piermarini S; Ricci F; Volpe G Electrochemical biosensors based on nanomodified screen-printed electrodes: Recent applications in clinical analysis. TrAC, Trends Anal. Chem 2016, 79, 114–126. [Google Scholar]

- (39).Morrin A; Killard AJ; Smyth MR Electrochemical characterization of commercial and home-made screen-printed carbon electrodes. Anal. Lett 2003, 36, 2021–2039. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.