Abstract

Rationale:

U.S. health departments routinely conduct post-arrival evaluation of immigrants and refugees at risk for tuberculosis, but this important intervention has not been thoroughly studied.

Objectives:

To assess outcomes of the post-arrival evaluation intervention.

Methods:

We categorized at risk immigrants and refugees as: with recent completion of treatment for pulmonary tuberculosis disease overseas (including Mexico and Canada); with suspected tuberculosis disease (chest radiograph/clinical symptoms suggestive of tuberculosis) but negative cultures overseas; or with latent tuberculosis infection diagnosed overseas. Among 2.1 million US-bound immigrants and refugees screened for tuberculosis overseas during 2013–2016, 90,737 were identified as at risk for tuberculosis. We analyzed a national dataset of these at risk immigrants and refugees, and calculated rates of tuberculosis disease for those who completed post-arrival evaluation.

Measurements and Main Results:

Among 4,225 persons with recent completion of treatment for pulmonary tuberculosis disease overseas, 3,005 (71.1%) completed post-arrival evaluation within 1 year of arrival; of these, 22 were diagnosed with tuberculosis disease (732 cases/100,000 persons): 4 sputum culture-positive cases (133 cases/100,000 persons), 13 sputum culture-negative cases (433 cases/100,000 persons), and 5 cases with no reported sputum culture results (166 cases/100,000 persons). Among 55,938 with suspected tuberculosis disease but negative cultures overseas, 37,089 (66.3%) completed post-arrival evaluation; of these, 597 were diagnosed with tuberculosis disease (1610 cases/100,000 persons): 262 sputum culture-positive cases (706 cases/100,000 persons), 281 sputum culture-negative cases (758 cases/100,000 persons), and 54 cases with no reported sputum culture results (146 cases/100,000 persons. Among 30,574 with latent tuberculosis infection diagnosed overseas, 18,466 (60.4%) completed post-arrival evaluation; of these, 48 were diagnosed with tuberculosis disease (260 cases/100,000 persons): 11 sputum culture-positive cases (60 cases/100,000 persons), 22 sputum culture-negative cases (119 cases/100,000 persons), and 15 cases with no reported sputum culture results (81 cases/100,000 persons). Of 21,714 persons for whom treatment for latent tuberculosis infection was recommended at post-arrival evaluation, 14,977 (69.0%) initiated and 8,695 (40.0%) completed treatment.

Conclusions:

Post-arrival evaluation of at risk immigrants and refugees can be highly effective. To optimize yield and impact of this intervention, strategies are needed to improve completion rates of post-arrival evaluation and treatment for latent tuberculosis infection.

Keywords: post-arrival evaluation, latent tuberculosis infection, treatment

Introduction

Finding and treating tuberculosis (TB) disease and latent TB infection (LTBI) in foreign-born persons are crucial to achieving TB elimination in the United States (1, 2, 3, 4). In 2018, TB incidence was 2.8 cases per 100,000 persons in the United States, and 69.5% (6,276) of 9,029 new TB cases were among non–U.S.-born persons (5). Incidence of TB disease among foreign-born persons is highest within the first year of arrival in the United States (6, 7). During 2013–2016, persons within 1 year of arrival accounted for 16.5% of non–U.S.-born TB cases and 24.8% of non–U.S.-born multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) cases (8). To reduce the importation of TB to the United States, U.S.-bound immigrants and refugees are required to undergo screening for TB overseas (including Mexico and Canada) and, when indicated, receive directly observed therapy to cure (9, 10, 11). Before 2007, the overseas screening used a sputum smear-based algorithm that could not diagnose smear-negative but culture-positive TB (10). In 2007, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) developed a new algorithm to include mycobacterial culture for persons with a chest radiograph suggestive of TB and directly observed therapy for those diagnosed with TB disease (11). Implementation of the new culture-based algorithm began in 2007 and was scaled up to all countries by 2013.

In addition to reducing importation of TB through treatment of TB disease overseas, the implementation of culture-based screening also identifies a large number of persons at risk for TB (11). Among 2,102,415 arrivals of immigrants and refugees during 2013–2016, 90,737 were identified overseas as at risk for tuberculosis. CDC routinely notifies state and local health departments of at risk immigrants and refugees entering their jurisdictions so they can follow up to screen for TB during domestic medical examination (9, 10, 11, 12). We analyze the outcomes from these post-arrival evaluations conducted during a 4-year period.

METHODS

Definition of immigrants and refugees

Immigrants, also known as lawful permanent residents or green card recipients, are persons who have been granted lawful permanent residence in the United States. In this analysis, “immigrants” referred to newly arrived persons admitted as immigrants from overseas. Newly arrived immigrants are distinct from adjustment-of-status immigrants, which refers to persons who enter the United States in a non-immigrant status, and later adjust their status to lawful permanent residents. Refugees are persons who are unable or unwilling to return to their country of nationality because of persecution or a well-founded fear of persecution due to race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion. Refugees apply for refugee status outside the United States. In this analysis, “refugees” referred to persons admitted from overseas as refugees including follow-to-join refugees (eligible relatives of previously admitted refugees). U.S.-bound immigrants and refugees are required to have overseas medical examination, and adjustment-of-status immigrants are required to have medical examination in the United States. This analysis does not include adjustment-of-status immigrants.

During 2013–2016, there were 2,102,415 arrivals of immigrants and refugees, and 1,772,281 adjustment-of-status immigrants (not including refugees) in the United States (data were from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security).

Overseas TB screening

TB screening is a major component of the mandatory medical examination for U.S.-bound immigrants and refugees (9, 10, 11). The examination is performed overseas by “panel physicians”, licensed local physicians who are appointed by U.S. embassies and consulates (13). CDC provides technical instructions and quality oversight for the examination. The culture-based algorithm, which is used in TB screening and treatment, requires all persons aged ≥15 years to have a chest radiograph, and those aged 2–14 years in countries with a TB incidence ≥20 cases/100,000 population/year to undergo a tuberculin skin test or interferon-γ release assay and, if positive, to have a chest radiograph (11). Persons with a chest radiograph or clinical signs or symptoms suggestive of TB must provide 3 sputum specimens to undergo microscopy for acid-fast bacilli, culture for mycobacteria, confirmation of the mycobacterium species at least to the mycobacterium tuberculosis complex level, and drug susceptibility testing for positive cultures. Completion of directly observed therapy is required for those diagnosed with pulmonary TB disease (11). Details of the culture-based screening algorithm and its TB classifications for U.S.-bound immigrants and refugees are described elsewhere (11).

Study population

The study population of this analysis included arrivals of immigrants and refugees during 2013–2016 who 1) recently completed treatment for pulmonary TB disease overseas; 2) had suspected TB disease (chest radiograph/clinical symptoms suggestive of TB) but negative cultures overseas; or 3) had LTBI diagnosed overseas. We excluded 254 persons with suspected extrapulmonary tuberculosis disease but negative cultures overseas. Data from overseas screening and post-arrival evaluation within 1 year of arrival were obtained from the CDC’s Electronic Disease Notification (EDN) database (14). All persons aged 2–14 years in countries with a World Health Organization (WHO)-estimated TB incidence ≥20 cases/100,000 population/year received a tuberculin skin test or interferon-γ release assay, while other persons received this testing if panel physicians determined their risk for TB warranted testing.

Post-arrival evaluation in the United States

CDC routinely notifies state and local health departments of arriving at-risk immigrants and refugees via its EDN database (10, 11, 14). Health department physicians use a worksheet developed by CDC in post-arrival evaluation of at risk immigrants and refugees, assign a TB diagnosis, treat TB disease, may recommend and offer treatment to persons with LTBI, and enter the evaluation data directly to CDC’s EDN database (10, 11, 14).

For persons whom health department physicians suspect pulmonary TB disease, 3 sputum specimens are obtained on 3 consecutive days for mycobacterial culture. Drug susceptibility testing is conducted for those who have positive culture results. Based on the results of sputum culture and chest radiograph/clinical symptoms, health department physicians assign a TB diagnosis for immigrants and refugees. In this analysis, we categorized persons with TB disease as sputum culture-positive, sputum culture-negative, and culture results not reported.

Ethics review

The study protocol was reviewed for human subjects concerns by CDC and found to be consistent with CDC’s public health surveillance activities and not human subjects research; therefore, review by an institutional review board was not required.

Statistical analysis

We calculated the proportions of completion of post-arrival evaluation, and rates of TB disease for newly arrived at risk immigrants and refugees. For persons who were recommended for LTBI treatment at post-arrival evaluation, we calculated the proportions of initiation and completion of treatment.

We applied a modified Poisson regression approach (i.e., Poisson regression with a robust error variance) to assess risk factors for sputum culture-positive TB disease among newly arrived at risk immigrants and refugees in the United States (15). We also applied the modified Poisson regression approach to evaluate risk factors for 1) non-completion of post-arrival evaluation among at risk immigrants and refugees, 2) non-initiation of LTBI treatment among persons for whom treatment was recommended at post-arrival evaluation, and 3) non-completion of LTBI treatment among persons who initiated treatment at post-arrival evaluation (15). These models included year of arrival, visa type, sex, age, country of birth, and overseas TB classification.

RESULTS

Post-arrival evaluation in the United States

During 2013–2016, 64.5% (58,560) of 90,737 immigrants and refugees at risk for TB completed post-arrival evaluation. Median time between overseas medical examination and initiation of post-arrival evaluation was 98 days (interquartile range 79–120) for persons with completion of treatment for pulmonary TB disease overseas, 99 days (interquartile range 77–123) for those with suspected TB disease but negative cultures overseas, and 123 days (interquartile range 79–174) for those with LTBI diagnosed overseas.

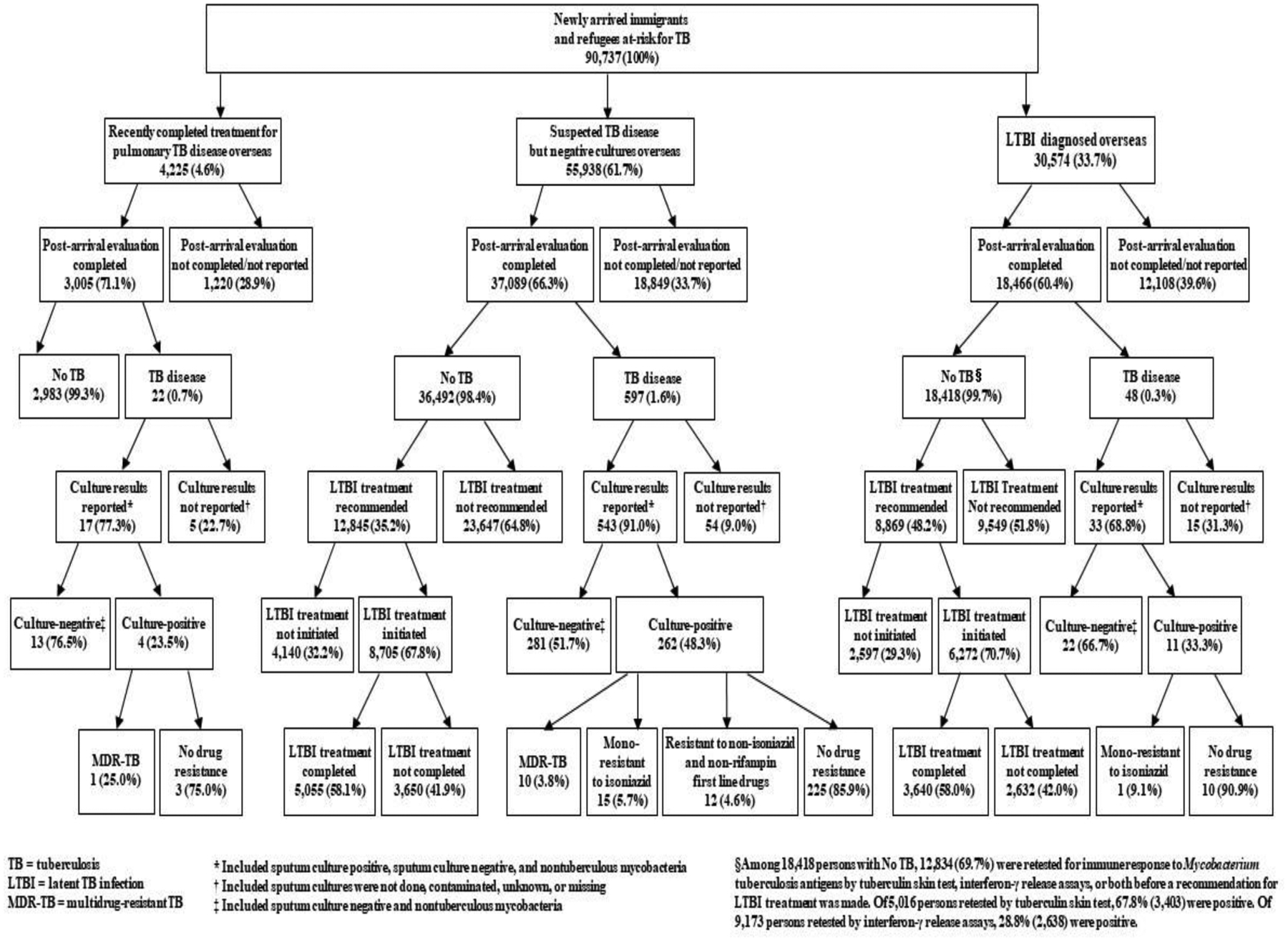

Of 4,225 persons with recent completion of treatment for pulmonary TB disease overseas, 3,005 (71.1%) completed post-arrival evaluation (Figure 1). Post-arrival evaluation identified 22 TB cases (732 cases/100,000 persons): 4 sputum culture-positive cases (133 cases/100,000 persons), 13 sputum culture-negative cases (433 cases/100,000 persons), and 5 cases with no reported sputum culture results (166 cases/100,000 persons; Table 1).

Figure 1.

Post-arrival evaluation of newly arrived immigrants and refugees at risk for TB in the United States, 2013–2016.

Table 1.

Rates of TB disease among immigrants and refugees who completed post-arrival evaluation within 1 year of arrival in the United States, 2013–2016.

| Variable | Persons with recent completion of treatment for pulmonary TB disease overseas | Persons with suspected TB disease but negative cultures overseas | Persons with LTBI diagnosed overseas | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | TB disease diagnosed at post-arrival evaluation | Total | TB disease diagnosed at post-arrival evaluation | Total | TB disease diagnosed at post-arrival evaluation | ||||||||||||||||

| Culture-positive | Culture-negative* | Culture results not reported† | Culture-positive | Culture-negative* | Culture results not reported† | Culture-positive | Culture-negative* | Culture results not reported† | |||||||||||||

| No. | Rate‡ | No. | Rate‡ | No. | Rate‡ | No. | Rate‡ | No. | Rate‡ | No. | Rate‡ | No. | Rate‡ | No. | Rate‡ | No. | Rate‡ | ||||

| Year of arrival | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 2013 | 721 | 1 | 139 | 1 | 139 | 1 | 139 | 8,345 | 62 | 743 | 62 | 743 | 20 | 240 | 4,831 | 2 | 41 | 7 | 145 | 3 | 62 |

| 2014 | 791 | 1 | 126 | 2 | 253 | 3 | 379 | 8,361 | 65 | 777 | 69 | 825 | 12 | 144 | 4,323 | 3 | 69 | 8 | 185 | 9 | 208 |

| 2015 | 744 | 2 | 269 | 5 | 672 | 0 | 0 | 9,051 | 61 | 674 | 69 | 762 | 13 | 144 | 4,512 | 3 | 66 | 5 | 111 | 0 | 0 |

| 2016 | 749 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 668 | 1 | 134 | 11,332 | 74 | 653 | 81 | 715 | 9 | 79 | 4,800 | 3 | 63 | 2 | 42 | 3 | 63 |

| Visa type | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Immigrant | 2,113 | 1 | 47 | 4 | 189 | 4 | 189 | 27,085 | 216 | 797 | 180 | 665 | 33 | 122 | 14,959 | 3 | 20 | 12 | 80 | 9 | 60 |

| Refugee | 892 | 3 | 336 | 9 | 1,009 | 1 | 112 | 10,004 | 46 | 460 | 101 | 1,010 | 21 | 210 | 3,507 | 8 | 228 | 10 | 285 | 6 | 171 |

| Gender | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Male | 1,752 | 3 | 171 | 10 | 571 | 2 | 114 | 18,256 | 130 | 712 | 150 | 822 | 23 | 126 | 9,259 | 6 | 65 | 10 | 108 | 7 | 76 |

| Female | 1,253 | 1 | 80 | 3 | 239 | 3 | 239 | 18,833 | 132 | 701 | 131 | 696 | 31 | 165 | 9,207 | 5 | 54 | 12 | 130 | 8 | 87 |

| Age | |||||||||||||||||||||

| <2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8333 | 61 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2–14 | 106 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 943 | 2 | 1,887 | 534 | 3 | 562 | 13 | 2,434 | 6 | 1124 | 17,270 | 8 | 46 | 22 | 127 | 15 | 87 |

| 15–44 | 1,449 | 2 | 138 | 6 | 414 | 2 | 138 | 12,350 | 102 | 826 | 117 | 947 | 20 | 162 | 843 | 2 | 237 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 45–64 | 1,045 | 2 | 191 | 5 | 478 | 0 | 0 | 15,052 | 98 | 651 | 93 | 618 | 22 | 146 | 234 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ≥65 | 402 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 249 | 1 | 249 | 9,141 | 59 | 645 | 58 | 635 | 5 | 55 | 58 | 1 | 1724 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Two age groups | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 2–14 | 106 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 943 | 2 | 1887 | 534 | 3 | 562 | 13 | 2434 | 6 | 1124 | 17,270 | 8 | 46 | 22 | 127 | 15 | 87 |

| Recent contact§ | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 25,000 | 0 | 0 | 214 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| No recent contact | 105 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 952 | 2 | 1,905 | 530 | 3 | 566 | 12 | 2,264 | 6 | 1,132 | 17,056 | 8 | 47 | 22 | 129 | 15 | 88 |

| ≥15 | 2,896 | 4 | 138 | 12 | 414 | 3 | 104 | 36,543 | 259 | 709 | 268 | 733 | 47 | 129 | 1,135 | 3 | 264 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Recent contact§ | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 160 | 1 | 625 | 1 | 625 | 1 | 625 | 523 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| No recent contact | 2,880 | 4 | 139 | 12 | 417 | 3 | 104 | 36,383 | 258 | 709 | 267 | 734 | 46 | 126 | 612 | 3 | 490 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Country of birthll | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Mexico | 53 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3,334 | 6 | 180 | 15 | 450 | 3 | 90 | 2,386 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Philippines | 1,011 | 1 | 99 | 1 | 99 | 1 | 99 | 9,846 | 99 | 1,005 | 54 | 548 | 12 | 122 | 8,684 | 1 | 12 | 8 | 92 | 5 | 58 |

| India | 37 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2,703 | 0 | 0 | 1,476 | 14 | 949 | 13 | 881 | 4 | 271 | 137 | 1 | 730 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Vietnam | 702 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 142 | 2 | 285 | 3,589 | 40 | 1,115 | 26 | 724 | 5 | 139 | 703 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 142 |

| China | 139 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 719 | 0 | 0 | 1,979 | 11 | 556 | 11 | 556 | 1 | 51 | 252 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 397 |

| Guatemala | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 29 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 80 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Haiti | 23 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 295 | 4 | 1,356 | 8 | 2,712 | 1 | 339 | 223 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ethiopia | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2,500 | 669 | 7 | 1,046 | 10 | 1,495 | 5 | 747 | 374 | 1 | 267 | 1 | 267 | 2 | 535 |

| Honduras | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 27 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 69 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Burma | 451 | 2 | 443 | 5 | 1,109 | 0 | 0 | 3,044 | 19 | 624 | 32 | 1,051 | 3 | 99 | 639 | 4 | 626 | 1 | 156 | 1 | 156 |

| Other | 547 | 1 | 183 | 4 | 731 | 1 | 183 | 12,801 | 62 | 484 | 112 | 875 | 20 | 156 | 4,919 | 4 | 81 | 12 | 244 | 5 | 102 |

| TB incidence in country of birth** | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 0–19 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 527 | 2 | 380 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 218 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 459 | 0 | 0 |

| 20–99 | 262 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 382 | 0 | 0 | 10,118 | 32 | 316 | 52 | 514 | 6 | 59 | 4,999 | 2 | 40 | 5 | 100 | 5 | 100 |

| ≥100 | 2,742 | 4 | 146 | 12 | 438 | 5 | 182 | 26,436 | 228 | 862 | 229 | 866 | 48 | 182 | 13,244 | 9 | 68 | 16 | 121 | 10 | 76 |

| No estimate | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Recent contact§ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 164 | 1 | 610 | 2 | 1220 | 1 | 610 | 744 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| No | 2,988 | 4 | 134 | 13 | 435 | 5 | 167 | 36,925 | 261 | 707 | 279 | 756 | 53 | 144 | 17,722 | 11 | 62 | 22 | 124 | 15 | 85 |

| Total | 3,005 | 4 | 133 | 13 | 433 | 5 | 166 | 37,089 | 262 | 706 | 281 | 758 | 54 | 146 | 18,466 | 11 | 60 | 22 | 119 | 15 | 81 |

“Sputum culture-negative” included negative-culture results or nontuberculous mycobacteria

“Sputum culture results not reported” included culture results reporting as not done, contaminated, unknown, or missing

Number of cases per 100,000 persons

A recent contact of a known TB case

The 10 birth countries of the most reported TB cases among non–U.S.-born persons in the United States in 2016

2016 WHO-estimated TB incidence for country of birth

Among 55,938 persons with suspected TB disease but negative cultures overseas, 37,089 (66.3%) completed post-arrival evaluation (Figure 1). Post-arrival evaluation identified 597 TB cases (1610 cases/100,000 persons): 262 sputum culture-positive cases (706 cases/100,000 persons), 281 sputum culture-negative cases (758 cases/100,000 persons), and 54 cases with no reported sputum culture results (146 cases/100,000 persons; Table 1).

Among 30,574 persons with LTBI diagnosed overseas, 18,466 (60.4%) completed post-arrival evaluation (Figure 1). Post-arrival evaluation identified 48 TB cases (260 cases/100,000 persons): 11 sputum culture-positive cases (60 cases/100,000 persons), 22 sputum culture-negative cases (119 cases/100,000 persons), and 15 cases with no reported sputum culture results (81 cases/100,000 persons; Table 1). Rates per 100,000 persons for sputum culture-positive TB were 46 and 264 for those aged 2–14 and ≥15 years, with LTBI diagnosed overseas, respectively; Table 1).

Among 30,574 persons with LTBI diagnosed overseas, 29,735 (97.3%) had data on testing for immune response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigens; of these, 28,803 (96.9%) were tested by tuberculin skin tests, 625 (2.1%) tested by interferon-γ release assays, and 307 (1.0%) tested by both tuberculin skin tests and interferon-γ release assays.

Among 18,418 persons with LTBI diagnosed overseas who completed post-arrival evaluation and were not diagnosed with TB disease, 12,834 (69.7%) were retested by tuberculin skin tests, interferon-γ release assays, or both before a recommendation for LTBI treatment was made. Of 5,016 persons retested by tuberculin skin test, 67.8% (3,403) were positive. Of 9,173 persons retested by interferon-γ release assay, 28.8% (2,638) were positive.

Drug resistance

Of 277 sputum culture-positive TB cases, 11 (4.0%) had MDR-TB, 16 (5.8%) were mono-resistant to isoniazid, and 12 (4.3%) resistant to a non-isoniazid and non-rifampin first-line drug (Figure 1).

Risk factors for sputum culture-positive TB at post-arrival evaluation

Among immigrants and refugees from the 10 birth countries with the most reported non–U.S.-born TB cases in the United States in 2016, risk for sputum culture-positive TB was higher among persons born in the Philippines (adjusted risk ratio [RR] 5.8, 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.5–13.2), India (adjusted RR 6.2, 95% CI 2.4–16.0), Vietnam (adjusted RR 6.6, 95% CI 2.8–15.5), China (adjusted RR 3.4, 95% CI 1.3–9.2), Haiti (adjusted RR 7.7, 95% CI 2.2–27.1), Ethiopia (adjusted RR 7.6, 95% CI 2.6–21.9), and Myanmar (adjusted RR 6.3, 95% CI 2.3–17.8) than among those born in Mexico (Table 2). Persons with suspected TB disease but negative cultures overseas had a higher risk for sputum culture-positive TB than those with recent completion of treatment for pulmonary TB disease overseas (adjusted RR 6.6, 95% CI 2.4–17.9; Table 2).

Table 2.

Evaluation of risk factors for sputum culture-positive TB among newly arrived at risk immigrants and refugees in the United States, 2013–2016*.

| Variable | Total | Persons with sputum culture-positive TB | No. of Persons with no TB | Adjusted RR (95% CI)† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | No. of cases per 100,000 persons | ||||

| Year of arrival | |||||

| 2013 | 13,803 | 65 | 471 | 13,738 | Reference |

| 2014 | 13,372 | 69 | 516 | 13,303 | 1.1 (0.8–1.6) |

| 2015 | 14,215 | 66 | 464 | 14,149 | 1.0 (0.7–1.4) |

| 2016 | 16,780 | 77 | 459 | 16,703 | 0.9 (0.7–1.3) |

| Visa type | |||||

| Immigrant | 43,915 | 220 | 501 | 43,695 | 1.5 (0.9–2.5) |

| Refugee | 14,255 | 57 | 401 | 14,198 | Reference |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 29,065 | 139 | 478 | 28,926 | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) |

| Female | 29,105 | 138 | 474 | 28,967 | Reference |

| Age | |||||

| <2 | 75 | 0 | 0 | 75 | - |

| 2–14 | 17,851 | 11 | 62 | 17,840 | 0.5 (0.1–2.5) |

| 15–44 | 14,497 | 106 | 731 | 14,391 | 1.3 (0.9–1.9) |

| 45–64 | 16,211 | 100 | 617 | 16,111 | 0.9 (0.7–1.3) |

| ≥65 | 9,536 | 60 | 629 | 9,476 | Reference |

| Country of birth‡ | |||||

| Mexico | 5,755 | 6 | 104 | 5,749 | Reference |

| Philippines | 19,460 | 101 | 519 | 19,359 | 5.8 (2.5–13.2) |

| India | 1,632 | 15 | 919 | 1,617 | 6.2 (2.4–16.0) |

| Vietnam | 4,959 | 40 | 807 | 4,919 | 6.6 (2.8–15.5) |

| China | 2,356 | 11 | 467 | 2,345 | 3.4 (1.3–9.2) |

| Guatemala | 110 | 0 | 0 | 110 | - |

| Haiti | 532 | 4 | 752 | 528 | 7.7 (2.2–27.1) |

| Ethiopia | 1,064 | 8 | 752 | 1,056 | 7.6 (2.6–21.9) |

| Honduras | 97 | 0 | 0 | 97 | - |

| Myanmar | 4,092 | 25 | 611 | 4,067 | 6.3 (2.3–17.8) |

| Other | 18,113 | 67 | 370 | 18,046 | 3.6 (1.5–8.5) |

| Overseas TB classification | |||||

| Recent completion of treatment for pulmonary TB disease overseas | 2,987 | 4 | 134 | 2,983 | Reference |

| Suspected TB disease but negative cultures overseas | 36,754 | 262 | 713 | 36,492 | 6.6 (2.4–17.9) |

| LTBI diagnosed overseas | 18,429 | 11 | 60 | 18,418 | 1.1 (0.2–7.3) |

Excluded 316 sputum culture-negative TB cases and 74 TB cases with no reported culture results

Estimated by using a modified Poisson regression approach (i.e., Poisson regression with a robust error variance), RR = risk ratio, CI = confidence interval

The 10 birth countries of the most reported TB cases among non–U.S.-born persons in the United States in 2016

Treatment for LTBI at post-arrival evaluation

Of 21,714 persons for whom LTBI treatment was recommended at post-arrival evaluation, 14,977 (69.0%) initiated treatment and 8,695 (40.0%) completed treatment (Table 3).

Table 3.

Initiation and completion of LTBI treatment among immigrants and refugees for whom treatment was recommended at post-arrival evaluation in the United States, 2013–2016.

| Variable | Persons for whom treatment was recommended | Initiation of treatment | Completion of treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % of persons for whom treatment was recommended | No. | % of persons who initiated treatment | % of persons for whom treatment was recommended | ||

| Year of arrival | ||||||

| 2013 | 5,589 | 3,979 | 71.2 | 2,084 | 52.4 | 37.3 |

| 2014 | 5,164 | 3,598 | 69.7 | 2,056 | 57.1 | 39.8 |

| 2015 | 5,109 | 3,441 | 67.4 | 2,183 | 63.4 | 42.7 |

| 2016 | 5,852 | 3,959 | 67.7 | 2,372 | 59.9 | 40.5 |

| Visa type | ||||||

| Immigrant | 15,803 | 10,260 | 64.9 | 6,078 | 59.2 | 38.5 |

| Refugee | 5,911 | 4,717 | 79.8 | 2,617 | 55.5 | 44.3 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 11,083 | 7,719 | 69.6 | 4,499 | 58.3 | 40.6 |

| Female | 10,631 | 7,258 | 68.3 | 4,196 | 57.8 | 39.5 |

| Age | ||||||

| <2 | 27 | 20 | 74.1 | 11 | 55.0 | 40.7 |

| 2–14 | 8,389 | 5,940 | 70.8 | 3,422 | 57.6 | 40.8 |

| 15–44 | 4,869 | 3,523 | 72.4 | 2,111 | 59.9 | 43.4 |

| 45–64 | 5,729 | 3,867 | 67.5 | 2,271 | 58.7 | 39.6 |

| ≥65 | 2,700 | 1,627 | 60.3 | 880 | 54.1 | 32.6 |

| Country of birth* | ||||||

| Mexico | 2,107 | 1,462 | 69.4 | 768 | 52.5 | 36.4 |

| Philippines | 6,945 | 4,369 | 62.9 | 2,732 | 62.5 | 39.3 |

| India | 587 | 389 | 66.3 | 226 | 58.1 | 38.5 |

| Vietnam | 1,767 | 1,079 | 61.1 | 611 | 56.6 | 34.6 |

| China | 899 | 503 | 56.0 | 258 | 51.3 | 28.7 |

| Guatemala | 38 | 29 | 76.3 | 18 | 62.1 | 47.4 |

| Haiti | 299 | 232 | 77.6 | 152 | 65.5 | 50.8 |

| Ethiopia | 574 | 416 | 72.5 | 234 | 56.3 | 40.8 |

| Honduras | 40 | 31 | 77.5 | 19 | 61.3 | 47.5 |

| Myanmar | 1,411 | 1,140 | 80.8 | 700 | 61.4 | 49.6 |

| Other | 7,047 | 5,327 | 75.6 | 2,977 | 55.9 | 42.2 |

| TB incidence in countries of birth† | ||||||

| 0–19 | 205 | 128 | 62.4 | 74 | 57.8 | 36.1 |

| 20–99 | 5,334 | 3,628 | 68.0 | 2,041 | 56.3 | 38.3 |

| ≥100 | 16,171 | 11,219 | 69.4 | 6,579 | 58.6 | 40.7 |

| No estimate | 4 | 2 | 50.0 | 1 | 50.0 | 25.0 |

| Overseas TB classification | ||||||

| Recent completion of treatment for pulmonary TB disease overseas | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Suspected TB disease but negative cultures overseas | 12,845 | 8705 | 67.8 | 5,055 | 58.1 | 39.4 |

| LTBI diagnosed overseas | 8,869 | 6272 | 70.7 | 3,640 | 58.0 | 41.0 |

| Total | 21,714 | 14,977 | 69.0 | 8,695 | 58.1 | 40.0 |

The 10 birth countries of the most reported tuberculosis cases among non–U.S.-born persons in the United States in 2016

2016 WHO-estimated tuberculosis incidence for country of birth

Factors associated with non-completion of post-arrival evaluation

Non-completion of post-arrival evaluation was more likely among immigrants than among refugees (adjusted RR 1.4, 95% CI 1.3–1.4; Table 4). Compared with persons born in Mexico, non-completion of post-arrival evaluation was less likely among those born in the Philippines (adjusted RR 0.9, 95% CI 0.8–0.9), India (adjusted RR 0.8, 95% CI 0.8–0.9), Vietnam (adjusted RR 0.8, 95% CI 0.8–0.9), Haiti (adjusted RR 0.8, 95% CI 0.7–0.9), and Myanmar (adjusted RR 0.8, 95% CI 0.7–0.8), but more likely among those born in China (adjusted RR 1.1, 95% CI 1.1–1.2; Table 4). Compared with persons with completion of treatment for pulmonary TB disease overseas, non-completion of follow-up evaluation was more likely among those with LTBI diagnosed overseas (adjusted RR 1.3, 95% CI 1.2–1.4; Table 4).

Table 4.

Evaluation of risk factors for non-completion of post-arrival evaluation in the United States of at risk immigrants and refugees, 2013–2016.

| Variable | Persons at risk for TB | Persons who did not complete post-arrival evaluation in the United States | Adjusted RR (95% CI)* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % of persons at risk for TB | |||

| Year of arrival | ||||

| 2013 | 20,804 | 6,907 | 33.2 | Reference |

| 2014 | 20,600 | 7,125 | 34.6 | 1.0 (1.0–1.1) |

| 2015 | 21,997 | 7,690 | 35.0 | 1.0 (1.0–1.1) |

| 2016 | 27,336 | 10,455 | 38.2 | 1.1 (1.1–1.2) |

| Visa type | ||||

| Immigrant | 71,221 | 27,064 | 38.0 | 1.4 (1.3–1.4) |

| Refugee | 19,516 | 5,113 | 26.2 | Reference |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 45,122 | 15,855 | 35.1 | 1.0 (0.9–1.0) |

| Female | 45,615 | 16,322 | 35.8 | Reference |

| Age | ||||

| <2 | 116 | 40 | 34.5 | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) |

| 2–14 | 29,614 | 11,704 | 39.5 | 0.9 (0.9–1.0) |

| 15–44 | 21,379 | 6,737 | 31.5 | 0.9 (0.9–1.0) |

| 45–64 | 24,514 | 8,183 | 33.4 | 0.9 (0.9–1.0) |

| ≥65 | 15,114 | 5,513 | 36.5 | Reference |

| Country of birth† | ||||

| Mexico | 10,082 | 4,309 | 42.7 | Reference |

| Philippines | 30,799 | 11,258 | 36.6 | 0.9 (0.8–0.9) |

| India | 2,502 | 852 | 34.1 | 0.8 (0.8–0.9) |

| Vietnam | 7,469 | 2,475 | 33.1 | 0.8 (0.8–0.9) |

| China | 4,352 | 1,982 | 45.5 | 1.1 (1.1–1.2) |

| Guatemala | 186 | 76 | 40.9 | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) |

| Haiti | 825 | 284 | 34.4 | 0.8 (0.7–0.9) |

| Ethiopia | 1,617 | 534 | 33.0 | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) |

| Honduras | 170 | 73 | 42.9 | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) |

| Myanmar | 5,352 | 1,218 | 22.8 | 0.8 (0.7–0.8) |

| Other | 27,383 | 9,116 | 33.3 | 0.9 (0.9–1.0) |

| Overseas TB classification | ||||

| Recent completion of treatment for pulmonary TB disease overseas | 4,225 | 1,220 | 28.9 | Reference |

| Suspected TB disease but negative cultures overseas | 55,938 | 18,849 | 33.7 | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) |

| LTBI diagnosed overseas | 30,574 | 12,108 | 39.6 | 1.3 (1.2–1.4) |

Estimated by using a modified Poisson regression approach (i.e., Poisson regression with a robust error variance), RR = risk ratio, CI = confidence interval

The 10 birth countries of the most reported tuberculosis cases among non–U.S.-born persons in the United States in 2016

Factors associated with non-initiation of LTBI treatment at post-arrival evaluation

Non-initiation of LTBI treatment was more likely among immigrants than among refugees (adjusted RR 1.5, 95% CI 1.3–1.6; Table 5). Compared with persons aged ≥65 years, non-initiation of treatment was less likely among those aged 2–14 years (adjusted RR 0.7, 95% CI 0.6–0.8), 15–44 years (adjusted RR 0.8, 95% CI 0.8–0.9), and 45–64 years (adjusted RR 0.8, 95% CI 0.8–0.9; Table 5). Compared with persons born in Mexico, non-initiation of treatment was more likely among those born in the Philippines (adjusted RR 1.2, 95% CI 1.1–1.3), Vietnam (adjusted RR 1.3, 95% CI 1.2–1.4), and China (adjusted RR 1.4, 95% CI 1.3–1.5), but less likely among those born in Haiti (adjusted RR 0.7, 95% CI 0.6–0.9; Table 5).

Table 5.

Evaluation of risk factors for non-initiation and non-completion of LTBI treatment among immigrants and refugees for whom treatment was recommended at post-arrival evaluation in the United States, 2013–2016.

| Variable | Initiation of LTBI treatment* | Completion of LTBI treatment† | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Persons for whom treatment was recommended | Persons who did not initiate treatment | Adjusted RR (95% CI)‡ | Persons who initiated treatment | Persons who did not complete treatment | Adjusted RR (95% CI)‡ | |||

| No. | % of persons for whom treatment was recommended | No. | % of persons who initiated treatment | |||||

| Year of arrival | ||||||||

| 2013 | 5,589 | 1,610 | 28.8 | Reference | 3979 | 1,895 | 47.6 | Reference |

| 2014 | 5,164 | 1,566 | 30.3 | 1.1 (1.0–1.1) | 3598 | 1,542 | 42.9 | 0.9 (0.8–0.9) |

| 2015 | 5,109 | 1,668 | 32.6 | 1.1 (1.1–1.2) | 3441 | 1,258 | 36.6 | 0.8 (0.7–0.8) |

| 2016 | 5,852 | 1,893 | 32.3 | 1.1 (1.1–1.2) | 3959 | 1,587 | 40.1 | 0.8 (0.8–0.9) |

| Visa type | ||||||||

| Immigrant | 15,803 | 5,543 | 35.1 | 1.5 (1.3–1.6) | 10260 | 4,182 | 40.8 | 0.9 (0.8–0.9) |

| Refugee | 5,911 | 1,194 | 20.2 | Reference | 4717 | 2,100 | 44.5 | Reference |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 11,083 | 3,364 | 30.4 | 1.0 (0.9–1.0) | 7719 | 3,220 | 41.7 | 1.0 (0.9–1.0) |

| Female | 10,631 | 3,373 | 31.7 | Reference | 7258 | 3,062 | 42.2 | Reference |

| Age | ||||||||

| <2 | 27 | 7 | 25.9 | 0.6 (0.3–1.2) | 20 | 9 | 45.0 | 1.1 (0.6–1.7) |

| 2–14 | 8,389 | 2,449 | 29.2 | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) | 5940 | 2,518 | 42.4 | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) |

| 15–44 | 4,869 | 1,346 | 27.6 | 0.8 (0.8–0.9) | 3523 | 1,412 | 40.1 | 0.9 (0.8–0.9) |

| 45–64 | 5,729 | 1,862 | 32.5 | 0.8 (0.8–0.9) | 3867 | 1,596 | 41.3 | 0.9 (0.8–0.9) |

| ≥65 | 2,700 | 1,073 | 39.7 | Reference | 1627 | 747 | 45.9 | Reference |

| Country of birth§ | ||||||||

| Mexico | 2,107 | 645 | 30.6 | Reference | 1462 | 694 | 47.5 | Reference |

| Philippines | 6,945 | 2,576 | 37.1 | 1.2 (1.1–1.3) | 4369 | 1,637 | 37.5 | 0.8 (0.7–0.8) |

| India | 587 | 198 | 33.7 | 1.1 (0.9–1.2) | 389 | 163 | 41.9 | 0.9 (0.7–1.0) |

| Vietnam | 1,767 | 688 | 38.9 | 1.3 (1.2–1.4) | 1079 | 468 | 43.4 | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) |

| China | 899 | 396 | 44.0 | 1.4 (1.3–1.5) | 503 | 245 | 48.7 | 1.0 (0.9–1.2) |

| Guatemala | 38 | 9 | 23.7 | 0.8 (0.5–1.4) | 29 | 11 | 37.9 | 0.8 (0.5–1.2) |

| Haiti | 299 | 67 | 22.4 | 0.7 (0.6–0.9) | 232 | 80 | 34.5 | 0.7 (0.6–0.9) |

| Ethiopia | 574 | 158 | 27.5 | 1.1 (0.9–1.3) | 416 | 182 | 43.8 | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) |

| Honduras | 40 | 9 | 22.5 | 0.8 (0.4–1.4) | 31 | 12 | 38.7 | 0.8 (0.5–1.3) |

| Myanmar | 1,411 | 271 | 19.2 | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) | 1140 | 440 | 38.6 | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) |

| Other | 7,047 | 1,720 | 24.4 | 1.0 (0.9–1.2) | 5327 | 2,350 | 44.1 | 0.9 (0.8–0.9) |

| Overseas tuberculosis classification | ||||||||

| Recent completion of treatment for pulmonary TB disease overseas | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Suspected TB disease but negative cultures overseas | 12,845 | 4,140 | 32.2 | Reference | 8705 | 3,650 | 41.9 | Reference |

| LTBI diagnosed overseas | 8,869 | 2,597 | 29.3 | 1.0 (0.9–1.2) | 6272 | 2,632 | 42.0 | 0.9 (0.8–1.0) |

Included persons for whom LTBI treatment was recommended at post-arrival evaluation in the United States

Included persons who initiated LTBI treatment at post-arrival evaluation in the United States

Estimated by using a modified Poisson regression approach (i.e., Poisson regression with a robust error variance), RR = risk ratio, CI = confidence interval

The 10 birth countries of the most reported TB cases among non–U.S.-born persons in the United States in 2016

Risk factors associated with non-completion of LTBI treatment at post-arrival evaluation

Non-completion of LTBI treatment was less likely among immigrants than among refugees (adjusted RR 0.9, 95% CI 0.8–0.9; Table 5). Non-completion of treatment was less likely among persons aged 15–44 years (adjusted RR 0.9, 95% CI 0.8–0.9) and 45–64 years (adjusted RR 0.9, 95% CI 0.8–0.9) than among those aged ≥65 years (Table 5). Compared with persons born in Mexico, non-completion of treatment was less likely among those born in the Philippines (adjusted RR 0.8, 95% CI 0.7–0.8), Haiti (adjusted RR 0.7, 95% CI 0.6–0.9), and Myanmar (adjusted RR 0.7, 95% CI 0.6–0.8; Table 5).

DISCUSSION

Overseas TB screening has two goals: to find and treat U.S.-bound immigrants and refugees with TB disease overseas, and to identify those at risk for developing TB disease after arrival in the United States. The effect of overseas TB screening on finding and treating U.S-bound immigrants and refugees has been evaluated by a previous study (11). Our analysis demonstrated that post-arrival evaluation can be highly effective but completion rates need to be improved. During 2013–2016, post-arrival evaluation of immigrants and refugees within 1 year of arrival in the United States diagnosed 667 TB cases (277 sputum culture-positive, 316 sputum culture-negative, and 74 with sputum culture results not reported). However, 35.5% of 907,373 newly arrived at risk immigrants and refugees did not complete post-arrival evaluation or their evaluation data were not reported to CDC. Had these persons completed follow-up evaluation, by using the tuberculosis rates in Table 1, we estimated that 344 cases of active tuberculosis (142 culture-positive cases, 163 culture-negative, and 39 cases with no/not reported culture results) could have been diagnosed.

We found a high proportion of sputum culture-negative TB among cases diagnosed at post-arrival evaluation, 53.3% (316 of 593 cases with sputum culture results) overall and 76.5% (13 of 17 cases with culture results) for those with recent completion of treatment for pulmonary TB disease overseas. According to the U.S. National TB Surveillance System, 39.0% (1,431) of 3,667 cases with sputum culture results among non–U.S.-born persons within 1 year of arrival during 2013–2016 did not have positive cultures (data were from Division of TB Elimination, CDC). The high proportion of culture-negative cases provides reassurance the overseas screening program is succeeding in reducing the importation of overt, culture-positive, infectious TB. Possible explanations for this finding include over-diagnosis of TB disease; diagnosis at an early stage of disease by active screening; overrepresentation of conditions associated with extrapulmonary disease such as recurrent disease following treatment failure, or certain comorbidities; or some combination of these above factors. Key information from the post-arrival examination, such as detailed documentation of clinical decision-making and additional tests that may have been performed (e.g., molecular tests), is not captured by CDC’s EDN database. New studies with additional data are needed to further evaluate the high proportion of culture-negative TB diagnosed at post-arrival evaluation.

To help ensure U.S. TB control programs best understand who receives overseas TB treatment to cure, the 2018 update to CDC’s TB Technical Instructions for Panel Physicians created “Class B0 TB” for persons with recent completion of treatment for pulmonary TB disease overseas through the panel physicians’ rigorous directly observed therapy program (16). Our analysis showed that this new classification could be an effective tool for U.S. health department physicians to stratify risk and manage these patients. The creation of Class B0 TB could help health departments prioritize more resources to newly arrived immigrants and refugees with suspected TB disease but negative cultures overseas.

Previous studies have reported that recurrent TB rates range from 0.1% to 10.3%, depending on treatment regimens and time intervals of follow-up (17, 18, 19, 20). In our analysis, 4 (0.1%) of 3,005 persons with recent completion of treatment for pulmonary TB overseas were re-diagnosed with sputum culture-positive TB by post-arrival evaluation shortly after arrival (1 had multidrug-resistant TB). All four of these sputum culture-positive cases had received directly observed therapy overseas by panel physicians (one took self-administered therapy before presenting for the panel physician examination and then enrolled in the panel physician’s directly observed therapy program for the remainder of treatment, but did not have MDR-TB at post-arrival evaluation). Since the culture-based screening and treatment algorithm requires directly observed therapy overseen by a panel physician, a low risk of relapse or reinfection in the short time between completion of overseas treatment and post-arrival evaluation would be expected.

We found that MDR-TB was in 4.0% (11) of 277 sputum culture-positive TB cases at post-arrival evaluation. In comparison, the U.S. National TB Surveillance System reported that MDR-TB was in 3.0% (83) of 2,811 foreign-born sputum culture-positive TB cases within 1 year of arrival during 2013–2016 (8). To treat TB disease and LTBI effectively, more studies on drug-resistance in immigrants and refugees are needed.

Foreign-born persons in the United States have a high prevalence of LTBI (15.9% with positive interferon-γ release assay or 20.5% with tuberculin skin test ≥10mm) (21). To eliminate TB in the United States, finding and treating LTBI among foreign-born persons is critical (2, 3, 4, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26). During our analysis period, the culture-based overseas screening required a tuberculin skin test or interferon-γ release assay overseas only for children (2–14 years) in high-burden countries (11, 20). Expanding interferon-γ release assay requirement (tuberculin skin tests were disallowed in 2018) to include adults, as part of a comprehensive evaluation for TB disease consistent with U.S. recommendations and clinical practices, could help overseas screening identify more persons at risk for TB, leading to additional TB cases diagnosed at post-arrival evaluation. In our analysis, 3 cases of (264 cases/100,000 persons) sputum culture-positive TB were diagnosed in 1,135 adults (≥15 years) with LTBI diagnosed overseas. All 3 cases of sputum culture-positive TB were diagnosed in 612 adults without recent contact of a known TB case. Since our sample size is relatively small, adults with LTBI diagnosed overseas need to be further studied.

Tuberculin skin tests were commonly used in the overseas TB screening program for children during the study period. Of those with LTBI diagnosed overseas, less than a third (28.8%) were positive when retested by interferon-γ release assays at post-arrival evaluation. This could be one reason that many persons with LTBI diagnosed overseas were not recommended for preventive treatment at post-arrival evaluation. On October 1, 2018, the overseas medical examination for children started requiring testing by interferon-γ release assays only, and disallowed tuberculin skin tests. It is hoped the overseas diagnosis of LTBI will thus be more reliable, leading to an increase in the proportion of persons with LTBI diagnosed overseas to be offered preventive treatment at post-arrival evaluation.

Treating LTBI in refugees overseas and in newly arrived immigrants and refugees have been shown to be cost-effective (27, 28). However, ensuring completion of treatment for LTBI can be challenging (29). For example, in the United States and Canada, a completion rate of 49.3% was reported among foreign-born persons who initiated LTBI treatment during 2007–2008 (30). In our analysis, completion rate was 58.1% for immigrants and refugees who initiated treatment. Shorter, rifamycin-based, treatment regimens (31, 32, 33, 34), and active outreach policies (35) can improve the completion rate.

Our analysis found that 35.5% of at risk immigrants and refugees did not complete follow-up evaluation in the United States. There are elevated rates of TB disease post-arrival among persons with all three overseas TB classifications. The yield and impact of the post-arrival evaluation interventions depend on the number of at risk immigrants and refugees who complete the evaluation. Health departments and CDC need to be vigorous in implementing strategies to increase the completion rates of post-arrival evaluation. Our multivariate analysis showed non-completion of post-arrival evaluation was associated with several factors. Non-completion of post-arrival evaluation was more likely among persons born in Mexico and China than among those born in the rest of the 10 birth countries with most TB cases reported in the United States. Non-completion of post-arrival evaluation was more likely among persons with LTBI diagnosed overseas than among those with recent completion of treatment for pulmonary TB overseas. Non-completion of post-arrival evaluation was less likely among refugees than among immigrants, likely because they have 8 months of federally-funded medical assistance after arrival and also receive supports from domestic refugee health programs. Previous studies have reported that active outreach policies can improve the completion rates of post-arrival evaluation (9, 36, 37). For example, of newly arrived at risk immigrants and refugees, 82.9% of those who had an appointment with health department clinics and 81.0% of those who received the telephone numbers of their county health department’s TB programs at the port of entry completed post-arrival evaluation, but only 38.4% of those who did not have a referral at the port of entry completed post-arrival evaluation (37). Education about TB for immigrants and refugees could increase their willingness to complete a post-arrival evaluation. For example, during overseas screening, panel physician can communicate with at risk immigrants and refugees and encourage them to complete post-arrival evaluation in the United States. Post-arrival evaluation could also be improved if 1) state and local health departments have access to a fully electronic and complete record of the examination and treatment, if any, provided by panel physicians overseas for newly arrived at risk immigrants and refugees in their jurisdictions, and 2) the linkage is available for data of TB cases between the U.S. National TB Surveillance System and the CDC’s EDN database..

Data used in this analysis have several limitations. Diagnosis of sputum culture-negative TB based on chest radiograph findings and/or clinical symptoms is difficult and therefore misclassification of TB cases might have occurred at the post-arrival evaluation. Post-arrival evaluation data were unavailable for 35.5% of at-risk immigrants and refugees, and sputum culture results were unknown for 11.1% of TB cases. Our data only captured TB cases that occurred in the short time between overseas medical examination and post-arrival evaluation shortly after arrival; cases that might have occurred later were not identified in this analysis, but would be reported through the U.S. National TB Surveillance System.

In conclusion, our analysis demonstrated that post-arrival evaluation of newly arrived immigrants and refugees at risk for TB can be highly effective, but strategies are needed to improve the completion rate of post-arrival evaluation. Our analysis also suggests that the newly introduced overseas TB classification “Class B0 TB”, indicating persons recently treated by directly observed therapy for pulmonary TB disease overseas, will lead to improved risk stratification. Finally, our analysis highlights the need to improve the completion rate of treatment for persons with LTBI.

Acknowledgments:

We thank Dr. Alawode Oladele of the DeKalb County Tuberculosis Program and Dr. Mary Naughton of CDC’s Division of Global Migration and Quarantine for helpful discussions on preventive treatment for immigrants and refugees diagnosed with latent tuberculosis infection at U.S. follow-up evaluation. We also thank Dr. Joanna Regan of CDC’s Division of Global Migration and Quarantine for reviewing information of overseas diagnosis and treatment for some sputum culture-positive tuberculosis cases; Mr. Robert Pratt of CDC’s Division of Tuberculosis Elimination for providing us data from the U.S. National Tuberculosis Surveillance System on tuberculosis cases with sputum culture results among non-–U.S.-born persons within 1 year of arrival during 2013–2016; Mr. Wei-Lun Juang of CDC’s Division of Global Migration and Quarantine for providing computer programming supports; the staff of CDC’s EDN team for updating and managing CDC’s notification system for tuberculosis in immigrants and refugees; the staff of CDC’s Quarantine Stations for collecting information of overseas medical examination; the panel physicians for performing overseas tuberculosis screening; and the staff of state and local health departments for conducting follow-up evaluations.

The findings and conclusions of this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

References

- 1.American Thoracic Society. American Thoracic Society/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Infectious Diseases Society of America: controlling tuberculosis in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;172:1169–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cain KP, Benoit SR, Winston CA, Mac Kenzie WR. Tuberculosis among foreign-born persons in the United States. JAMA 2008;300:405–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.LoBue PA, Mermin JH. Latent tuberculosis infection: the final frontier of tuberculosis elimination in the USA. Lancet Infect Dis 2017;17:327–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hill AN, Becerra JE, Castro KG. Modeling tuberculosis trends in the USA. Epidemiol Infect 2012;140(10):1862–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Talwar A, Tsang CA, Price SF, et al. Tuberculosis — United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019; 68(11):257–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cain KP, Haley CA, Armstrong LR, et al. Tuberculosis among foreign-born persons in the United State: achieving tuberculosis elimination. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;175:75–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walter ND, Painter J, Parker M, et al. Tuberculosis Epidemiologic Studies Consortium. Persistent latent tuberculosis reactivation risk in United States immigrants. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014;189:88–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Online Tuberculosis Information System (OTIS) Data. (https://wonder.cdc.gov/TB-v2017.html)

- 9.Binkin NJ, Zuber PLF, Wells CD, et al. Overseas screening for tuberculosis in immigrants and refugees to the United States: current status. Clin Infect Dis 1996;23:1226–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu Y, Weinberg MS, Ortega LS, et al. Overseas screening for tuberculosis in U.S.-bound immigrants and refugees. N Engl J Med 2009;360:2406–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu Y, Posey DL, Cetron MS, Painter JA. Effect of a culture-based screening algorithm on tuberculosis incidence in immigrants and refugees bound for the United States: a population-based cross-sectional study. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:420–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor EM, Painter J, Posey DL, et al. Latent tuberculosis infection among immigrant and refugee children arriving in the United States: 2010. J Immigr Minor Health 2015. 10.1007/s10903-015-0273-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Y. Panel Physician. In: Loue S, Sajatovic M, editors. Encyclopedia of Immigrant Health. Germany: Springer. 2012:1171–2. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee D, Philen R, Wang J, et al. Disease surveillance among newly arriving refugees and immigrants – Electronic Disease Notification System, United States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2013;62(SS07):1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159(7):702–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tuberculosis Technical Instructions for Panel Physicians. (https://www.cdc.gov/immigrantrefugeehealth/exams/ti/panel/tuberculosis-panel-technical-instructions.html)

- 17.Hong Kong Chest Service/British Medical Research Council. Five year follow-up of a controlled trial of five 6-month regimens of chemotherapy for tuberculosis. Am Rev Respir Dis 1987;136:1339–1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hong Kong Chest Service/British Medical Research Council. Controlled trial of 2, 4, and 6-months of pyrazinamide in 6-month, three-times weekly regimens for smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis, including an assessment of a combined preparation of isoniazid, rifampin, and pyrazinamide: results at 30 months. Am Rev Respir Dis 1991;143:700–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Combs DL, O’Brien RJ, Geiter LJ. USPHS Tuberculosis Short-Course Chemotherapy Trial 21: effectiveness, toxicity, and acceptability: the report of final results. Ann Intern Med 1990;112:397–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Millet J-P, Shaw E, Orcau À, Casals M, Miró JM, et al. Tuberculosis recurrence after completion treatment in a European City: reinfection or relapse? PLoS ONE 2013;8(6):e64898. 10.1371/journal.pone.0064898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miramontes R, Hill AN, Yelk Woodruff RS, et al. Tuberculosis infection in the United States: prevalence estimates from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011–2012. PLoS ONE 2015;10(11):e0140881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shea KM, Kammerer JS, Winston CA, et al. Estimated rate of reactivation of latent tuberculosis infection in the United States, overall and by population subgroup. Am J Epidemiol 2014;179(2):216–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ricks PM, Cain KP, Oeltmann JE, et al. Estimating the burden of tuberculosis among foreign-born persons acquired prior to entering the U.S., 2005–2009. PLoS ONE 2011;6(11):e27405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Thoracic Society, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Targeted tuberculin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;161:S221–S247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lönnroth K, Migliori GB, Abubakar I, et al. Towards tuberculosis elimination: an action framework for low-incidence countries. Eur Respir J 2015;45(4):928–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization. Latent tuberculosis infection: Updated and consolidated guidelines for programmatic management. 2018. [PubMed]

- 27.Wingate LT, Coleman MS, de la Motte Hurst C, et al. A cost-benefit analysis of a proposed overseas refugee latent tuberculosis infection screening and treatment program. BMC Public Health 2015. December 1;15(1):1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Porco T, Lewis B, Marseille E, et al. Cost-effectiveness of tuberculosis evaluation and treatment of newly-arrived immigrants. BMC Public Health 2006;6:157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sandgren AA, Noordegraaf-Schouten MV, van Kessel F, et al. Initiation and completion rates for latent tuberculosis infection treatment: a systematic review. BMC Infect Dis 2016;16(1):204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hirsch-Moverman Y, Shrestha-Kuwahara R, Bethel J, et al. Latent tuberculous infection in the United States and Canada: who completes treatment and why? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2015;19:31–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sterling TR, Villarino ME, Borisov AS, et al. Three months of rifapentine and isoniazid for latent tuberculosis infection. N Engl J Med 2011;365(23):2155–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.LoBue PA, Menzies D. Treatment of latent tuberculosis infection: An update. Respirology 2010;15:603–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for use of an isoniazid-rifapentine regimen with direct observation to treat latent mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2011;60(48):1650–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Borisov AS, Bamrah Morris S, Njie GJ, et al. Update of recommendations for use of once-weekly isoniazid-rifapentine regimen to treat latent mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:723–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Subedi P, Drezner KA, Dogbey MC, et al. Evaluation of latent tuberculosis infection and treatment completion for refugees in Philadelphia, PA, 2010–2012. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2015;19(5):565–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Catlos EK, Cantwell MF, Bhatia G, et al. Public health interventions to encourage TB class A/B1/B2 immigrants to present for TB screening. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;158:1037–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bell TR, Molinari NM, Blumensaadt S, et al. Impact of port of entry referrals on initiation of follow-up evaluations for immigrants with suspected tuberculosis: Illinois. J Immigr Minor Health 2013;15(4):673–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]