Abstract

Objective:

Cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB)-induced endothelial dysfunction has been inferred by changes in pulmonary vascular resistance, alterations in circulating biomarkers, and post-operative capillary leak. Endothelial-dependent vasomotor dysfunction of the systemic vasculature has never been quantified in this setting. The objective of the current study was to quantify acute effects of cardiopulmonary bypass on endothelial vasomotor control and attempt to correlate these effects with post-operative cytokines, tissue edema, and clinical outcomes in infants.

Design:

Single center prospective observational cohort pilot study.

Setting:

Pediatric Cardiac ICU at a tertiary children’s hospital.

Patients:

Children less than 1 year-old requiring cardiopulmonary bypass for repair of a congenital heart lesion.

Intervention:

None.

Measurements and Main Results:

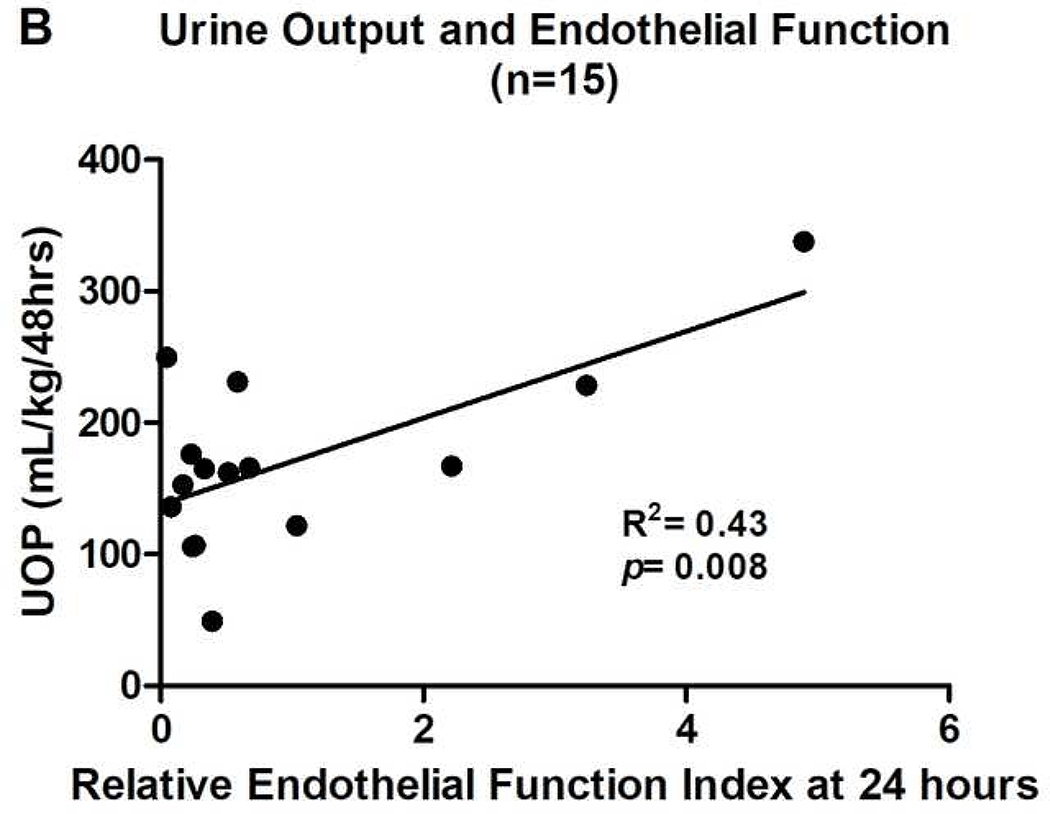

Laser Doppler perfusion monitoring (LDPM) was coupled with local iontophoresis of acetylcholine (Ach, endothelium-dependent vasodilator) or sodium nitroprusside (SNP, endothelium-independent vasodilator) to quantify endothelial-dependent vasomotor function in the cutaneous microcirculation. Measurements were obtained pre-operatively, 2–4 hours, and 24 hours after separation from CPB. Fifteen patients completed all LPDM measurements. Comparing pre-bypass with 2–4 hours post-bypass responses, there was a decrease in both peak perfusion (p=0.0006) and area under the dose response curve (p=0.005) following Ach, but no change in responses to SNP. Twenty-four hours after bypass responsiveness to Ach improved, but typically remained depressed from baseline. Conserved endothelial function was associated with higher urine output during the first 48 post-operative hours (R2=0.43, p=0.008).

Conclusions:

Cutaneous endothelial dysfunction is present in infants immediately following CPB and recovers significantly in some patients within 24 hours post-operatively. Confirmation of an association between persistent endothelial-dependent vasomotor dysfunction and decreased urine output could have important clinical implications. Ongoing research will explore the pattern of endothelial-dependent vasomotor dysfunction after CBP and its relationship with biochemical markers of inflammation and clinical outcomes.

Keywords: endothelium, cardiopulmonary bypass, inflammation, capillary leak syndrome, microcirculation, nitric oxide

INTRODUCTION

Cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) is essential for the repair of congenital heart defects, but the ensuing systemic inflammatory response complicates postoperative management. CPB increases serum levels of inflammatory mediators (cytokines, activated complement, reactive oxygen species), and results in activation of transcription factors such as NF-κB in the cells of the vascular wall. Upregulation of adhesion molecules on leukocytes, platelets, and endothelial cells promotes leukocyte extravasation and capillary leak (1). It has been proposed that this inflammatory milieu causes derangement in endothelial-dependent vasomotor function leading to alterations in vasomotor tone that can impact regional blood flow (2).

CPB-induced endothelial dysfunction has been inferred by changes in circulating levels of endothelial adhesion molecules, nitric oxide (NO•) byproducts, and endothelium derived pro-coagulation and fibrinolytic factors (3–6). While there have been studies that explored the degree of endothelial vasomotor dysfunction in response to CPB in adults, it is unclear if similar dysfunction occurs in children who lack a pre-existing burden of vascular pathology (7). Furthermore, the specific contribution of this microcirculatory derangement to organ dysfunction, and its relationship to other CPB-induced changes in endothelial function, such as increased capillary leak, are unknown.

Laser Doppler perfusion monitoring (LDPM) allows non-invasive quantitative assessment of microvascular perfusion. When coupled with transdermal iontophoresis of vasoactive agents, it provides an objective assessment of the functional status of the microvascular endothelium. Iontophoresis of acetylcholine (ACh) evaluates endothelial function since the largely NO•-dependent vasodilatory response to ACh is endothelium-dependent (8, 9). In contrast, sodium nitroprusside (SNP) is an NO• donor whose vasodilatory properties are endothelium-independent. LDPM coupled with iontophoresis of Ach and SNP has been used to assess vasomotor dysfunction in adults, where it has been shown to correlate with defects in vasomotor function in coronary and cerebrovascular disease, and hypertension (10). This methodology has also recently been employed to detect the presence of endothelial dysfunction, which is inferred by an impaired response to Ach and an intact response to SNP, in adults seven days after CPB (7).

In children, LDPM has been used to evaluate vasomotor function in diabetes, Kawasaki disease, and small for gestational age infants (11–14). However, LDPM has not been used in children undergoing CPB to direct measure endothelial dysfunction and whether this dysfunction correlates with circulating inflammatory markers or clinical endpoints. To this end, we hypothesized that microcirculatory endothelial vasomotor dysfunction would be detectable by LPDM in infants after CPB and would correlate with serum cytokine levels, capillary leak and severity of illness during the immediate 48 hour post-operative period.

METHODS

Study Design

This was a prospective cohort, pilot study conducted at the Pediatric Heart Institute and Pediatric Cardiac Critical Care Unit at the Monroe Carrel Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, TN. Patients were enrolled from November 2014 to February 2016. The study protocol was designed by the principal investigators and approved by the Institutional Review Board at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. Written consent was obtained from parents or legal guardians of all patients prior to participation in the study.

Patients

Patients < 1 year of age undergoing heart surgery requiring the use of CPB were eligible for the study. Parents or legal guardians were approached during the pre-operative clinic visit for potential enrollment. Patients were excluded or removed from the study if one of the following criteria were present: febrile illness within 4 weeks of surgery, need for surgical re-exploration or mechanical circulatory support (ECMO) within 24 hours post-operatively, or the presence of internal cardiac pacemaker. If a patient was removed from the study on the basis of the post-operative clinical course, data obtained prior to exclusion was included in results. Post-operative management was at the discretion of the ICU team and was not modified based on inclusion of a patient in this study.

Operative and Post-Operative Management

Cardiopulmonary bypass was achieved through a median sternotomy for a majority of procedures. Arterial cannulation was established at the ascending or transverse aorta, venous cannulation at superior and/or inferior vena cava. After the administration of heparin, cardiopulmonary bypass was initiated with roller pump extracorporeal circulation and an interposed membrane oxygenator. Mechanical ventilation was ceased when full cardiopulmonary bypass was achieved. The desired degree of hypothermia was induced by active circuit cooling, (18 to 34 degrees C, depending on the nature of the procedure), cardiac arrest was induced for intracardiac repairs by the application of an aortic cross clamp and infusion of high potassium Del Nido cardioplegic solution into the excluded aortic root. At the completion of repair, the heart was evacuated of any air, the cross clamp was removed to restore coronary circulation, mechanical ventilation was resumed, the patient was returned to normothermia, modified ultrafiltration was performed, and circuit support was withdrawn. Patient was transferred directly to the ICU and post-operative management was provided as directed by standardized procedural based protocols and modified at the discretion of the ICU team. Management was not modified based on inclusion of a patient in this study.

Timing of Measurements and Data Collection

Patients underwent serial assessments of endothelial-dependent vasomotor function at 3 time points: pre-operative (within 7 days of surgical date), 2–4 hours after removal from bypass, and 24 hours post-bypass. Additional data collected at all time points included blood pressure before Ach and SNP iontophoresis, estimation of total body water by bioelectrical impedance, and blood sampling for biomarker analysis. Hematocrit levels were recorded pre-operatively and first post-operative reading. A baseline creatinine level was recorded pre-operatively and the peak value was recorded for the 48 hour post-operative period. Clinical outcome data collected over the first 48 post-operative hours included; peak lactate, total intravenous fluid requirement, maximum vasoactive inotropic score (VIS), mean VIS, and total urine output. The vasoactive-inotropic score (VIS) was adapted from Gaies, et al., and milrinone dosing was not included due to its standard use in the immediate post-operative period in our cardiac ICU, regardless of severity of illness (15).

Endothelial-Dependent Vasomotor Function

Assessment of vasomotor function was accomplished by utilizing LDPM (PeriFlux 5010, Perimed, Stockholm, Sweden) with iontophoresis (Perilont 382b, Perimed, Stockholm, Sweden) of vasoactive compounds. The probe for the LDPM was equipped with a well housing a drug delivery electrode for iontophoresis, allowing for perfusion readings at the site of drug administration. During each reading, probe temperature was standardized at 33°C to avoid fluctuations in skin temperature. To assess endothelium-dependent vasomotor function, the drug delivery was performed using parameters previously established for use in children (13, 14). The delivery electrode was soaked with 180 microliters of 2% ACh (Sigma) and secured to the forearm of the patient. The dispersive electrode was attached at least 15cm proximal, typically on the shoulder. Prior to the start of iontophoresis, basal perfusion was recorded for 2.5 minutes. ACh was then delivered with a 0.1 mA anodal current for 20 seconds for a total of 5 doses separated by 60 seconds. Perfusion was monitored for a total of 10 minutes in order to standardize area under the curve (AUC) measurements. Following a 10 minute washout period, the protocol was repeated on the same arm at a separate site using 180 microliters of 1% sodium nitroprusside (SNP, Sigma) and a 0.2 mA cathodal current. The order of Ach iontophoresis followed by SNP iontophoresis was maintained throughout the study for consistency. All readings were performed by the primary author who was a pediatric critical care fellow at the time of this study.

Perfusion output data from the LPDM system is provided in perfusion units (PUs), an arbitrary unit of measurement. To measure the response to iontophoresis, PeriSoft Version 2.5 for Windows (Perimed, Stockholm, Sweden) was used to calculate the peak perfusion value and the AUC for the 10 minute monitoring period. Figure 1 provides an example of a complete set of perfusion recordings for a single patient. The peak perfusion value was defined as the highest perfusion reading achieved during the iontophoresis period, which was then normalized by subtracting the baseline perfusion value to correct for variability in baseline perfusion values between patients. Prior to calculating the AUC and peak perfusion values, the perfusion curve was zeroed to the baseline mean perfusion value. Changes in these measurements of vasomotor function after bypass were expressed as fraction of the pre-bypass values.

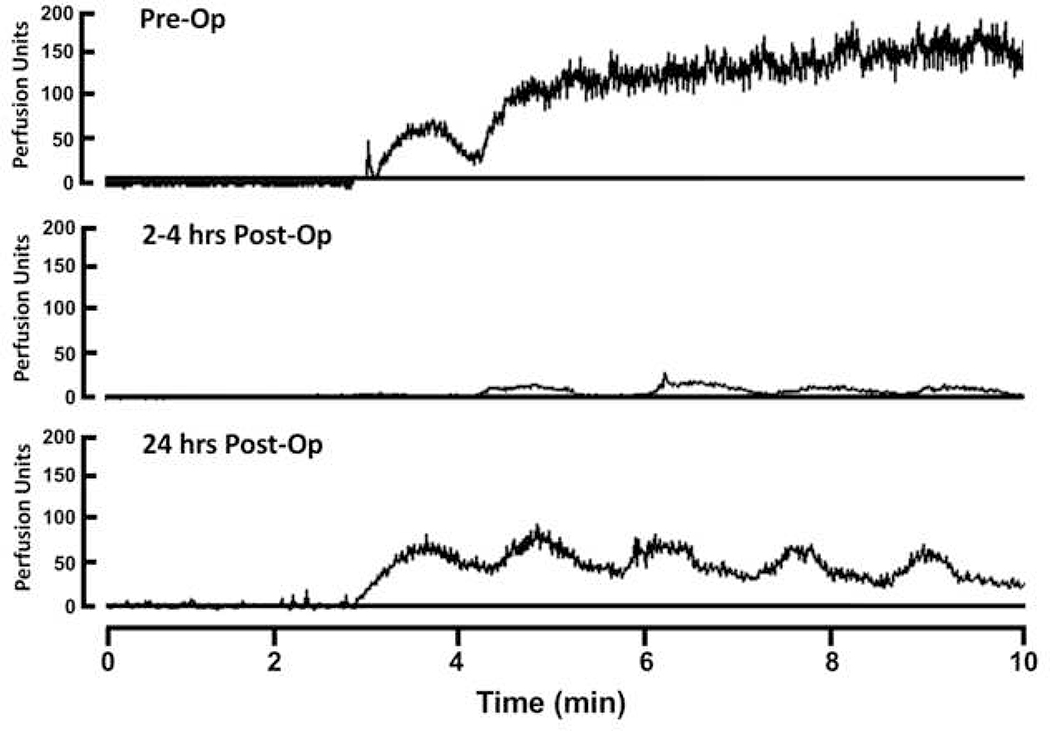

Figure 1.

Pre and Post-operative LDPM output readings from a single patient during 5 sequential pulses of ACh iontophoresis. Upward deflection indicates increasing perfusion. PU=perfusion unit.

Bioelectric Impedance

To estimate changes in total body water, a portable bioelectric impedance analysis (BIA) device (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN) was used to take readings with each assessment of vasomotor function (16). Four electrodes were placed on the hands and ipsilateral feet of the patient. Data output from BIA device included resistance (ohms, Ω), reactance (Ω), and Z-scores for both resistance and reactance measurements, which were normalized for the patient’s height. Three consecutive readings were taken while the patient was lying motionless and supine and results were averaged. Resistance values and Z-scores were utilized to assess changes in total body water (17).

Plasma Biomarkers

When possible, 0.5mL/kg of blood was collected in an EDTA treated vacutainer at the time of assessment of vasomotor function. Samples were placed on ice, centrifuged at 2200 RPM for 5 minutes to obtain plasma, and then stored at −80°C. Bio-Plex® assays (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) were used to obtain levels of platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1), soluble Tie2 receptor (sTie2), soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 (sVEGFR-1), sVEGFR-2, angiopoietin-2 (Ang-2), interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-8, IL-18, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α). Assays were performed according to manufacturer’s recommendations.

Statistical Analysis

All data are reported as medians with the 25–75th interquartile range. Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare pre and post-CPB results of vasomotor function, blood pressure, and laboratory values. In order to normalize and stratify endothelial-dependent vasomotor dysfunction, a relative endothelial function index (EFI) was created for both peak and AUC values. The index was calculated by dividing the post-operative values by the pre-operative value for each patient. Therefore, a value of less than 1 indicates vasomotor dysfunction. EFI values were used as a continuous variable in linear regression models with clinical and biochemical outcomes. GraphPad Prism version 5.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) was used for all statistical analysis. P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Patients

From November 2014 through February 2016, 23 patients were enrolled. Reliable pre-operative LDPM readings could not be obtained for 4 patients, and 4 patients did not complete post-operative readings secondary to surgical delay or cancellation. Therefore, a total of 15 patients completed the entire study and provided data for paired analysis in linear regression models. Patient characteristics and risk adjusted classification for congenital heart surgery (RACHS) classifications are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient Clinical and Surgical Characteristics

| Characteristic | Result (n=17) |

|---|---|

| Age, months (IQR) | 5.00 (0.25–6.00) |

| EGA, weeks (IQR) | 38.9 (36–39) |

| Birth weight, kg (IQR) | 3.04 (2.27–3.66) |

| Surgical weight, kg (IQR) | 5.37 (3.9–5.95) |

| CPB time, min (IQR) | 139 (100–183) |

| Aortic cross clamp time, min (IQR) | 75 (44–86) |

| RACHS category | |

| RACHS 1 (%) | 0 (0) |

| RACHS 2 (%) | 5 (29.4) |

| ASD/VSD closure | 3 (17.6) |

| Bidirectional cavopulmonary anastomosis (Glenn) | 1 (5.9) |

| TOF repair | 1 (5.9) |

| RACHS 3 (%) | 7 (41.2) |

| Transitional or complete AVSD repair | 4 (23.5) |

| DORV repair | 1 (5.9) |

| Mitral valve repair | 1 (5.9) |

| Tricuspid valve repair | 1 (5.9) |

| RACHS 4 (%) | 4 (23.5) |

| Interrupted aortic arch repair | 2 (11.7) |

| Arterial switch operation | 1 (5.9) |

| VSD repair with RV to PA conduit (Rastelli operation) | 1 (5.9) |

| RACHS 5 (%) | 0 (0) |

| RACHS 6 (%) | 1 (5.9) |

| Norwood operation | 1 (5.9) |

IQR=interquartile range, EGA=estimated gestational age, CPB=cardiopulmonary bypass, RACHS=Risk Adjustment for Congenital Heart Surgery, ASD=atrial septal defect, VSD=ventricular septal defect, TOF=tetralogy of Fallot, AVSD=atrioventricular septal defect, DORV=double outlet right ventricle

Values for continuous variables expressed as median with IQR. Values for categorical variable expressed as a number with percentage of patient population.

Vasomotor Function

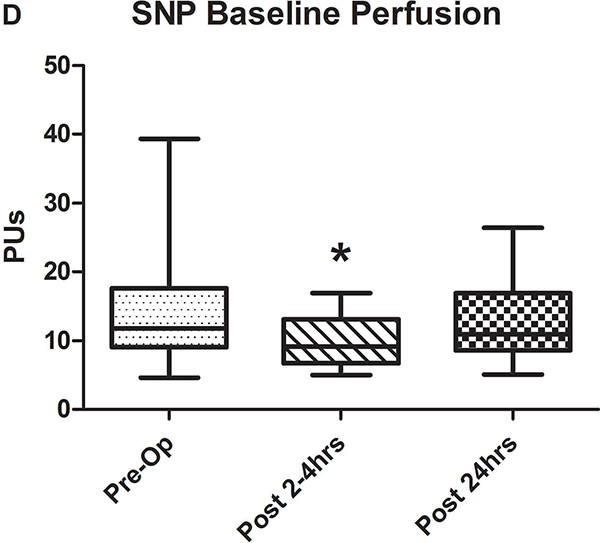

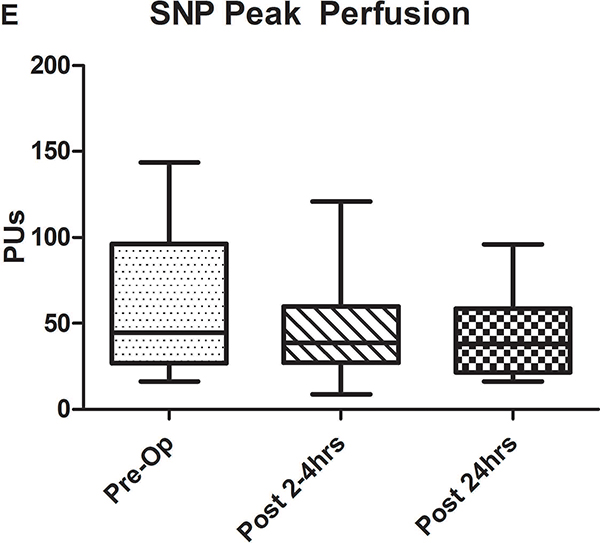

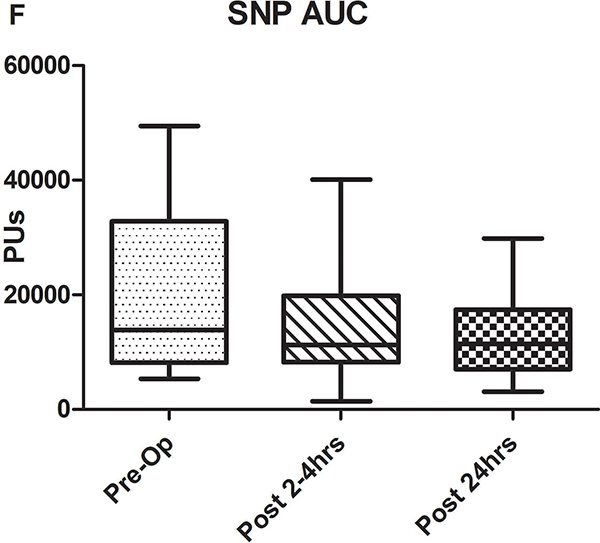

Examples of LDPM data from a single patient at all three time points obtained during iontophoresis of ACh are provided in Figure 1. In the pre-operative state, maximal vasodilation is achieved during the second 20 sec epoch of Ach iontophoresis and was maintained throughout the remainder of the measurement. In the immediate post-operative example, each epoch of iontophoresis was evident but maximal vasodilation was reduced compared to pre-operative levels. The results were qualitatively similar at 24 hours, but the magnitude of vasodilation was improved. Baseline cutaneous perfusion, which may also in part reflect endothelial function, tended to be decreased immediately following CPB for both sets of measurements (Figures 2A and D) and this effect reached statistical significance for the SNP group.

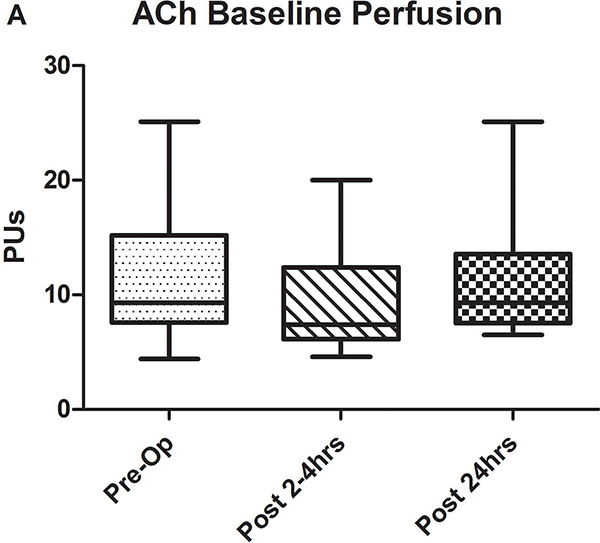

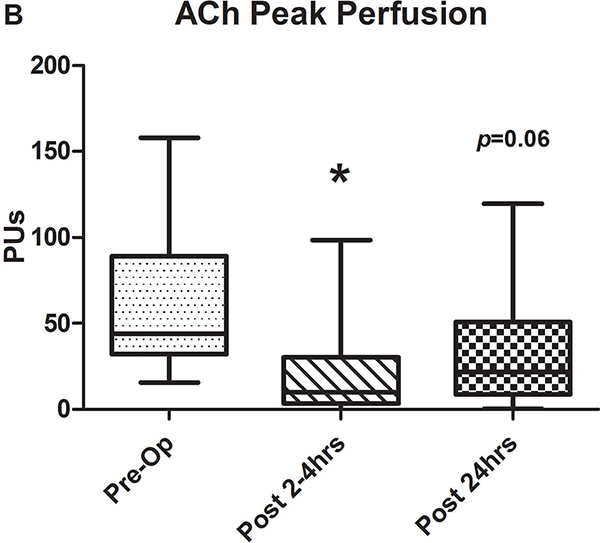

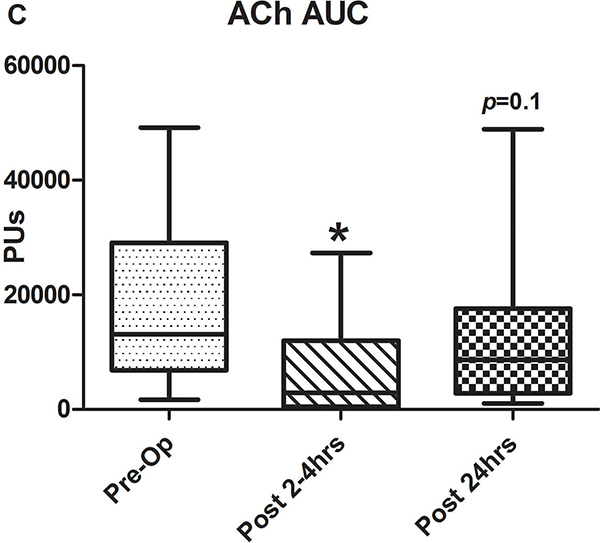

Figure 2.

A-C) Results for ACh iontophoresis, comparing pre-operative values with post-CPB values. D-F) Results for nitroprusside (SNP) iontophoresis. All data are expressed in perfusion units (PUs). AUC=area under the curve for 10 minute measurement period after being zeroed to baseline values. Lines within shaded area represent medians, edges of shaded area represent 1st and 3rd quartiles, and whiskers represent maximum and minimum values. Wilcoxon Rank Sum used to compare post-op values to pre-op values. * Indicates p<0.05.

Comparison of pre-operative responses to ACh with responses 2–4 hours after separation from CPB revealed a significant decrease in both median peak values (44 [IQR: 32.2–89.1] vs. 10.1 [3.6–30.5] perfusion units [PUs], p=0.005) and median AUC (13,143 [6,889–29,079] vs. 2,915 [507–11,979] PU/10min, p=.005) indicating the presence of significant endothelial-dependent vasomotor dysfunction (Figures 2A–C). After 24 hours, peak values (21.8 [9–50.8] PUs, p=0.07) and AUC (8,608 [2,806–17,570] PUs, p=0.1 compared to pre-op) improved from immediately post-CPB, but still tended to be depressed compared to baseline, however, this change was not statistically significant. The difference between the pre-op and 24 hour data was impacted by the fact that in four patients, endothelial-dependent vasomotor function actually improved between the immediate and 24 hour post-operative measurements and actually exceeded pre-operative responses. This is reflected by the large discrepancy between the 3rd quartile and maximum values at 24 hours post-CPB in Figures 2B and C. Endothelial-independent vasomotor responses to SNP iontophoresis did not significantly differ between pre-operative and either 2–4 hours (peak: 44.8 [26.9–96.4] vs 38.6 [27.1–59.9] PUs, p=0.25, AUC: 13,839 [8,134–32,821] vs. 11,249 [8,280–19,836] PUs, p=0.23) or 24 hours post-CPB (peak: 37.9 [21.5–58.7] PUs, p=0.28, AUC: 11,398 [7024–29845] PU/10min, p=0.12) (Figure 2D–F). Together, these data demonstrate significant impairment of microvascular dilation to Ach, but not SNP after CPB. This suggests the presence of impaired endothelial vasodilator production, but normal responsiveness of the vascular smooth muscle to NO•.

We also estimated the prevalence of endothelial dysfunction in the population by examining the change in response to vasodilators at 2 and 24 hours relative to each patient’s respective baseline response. All but 2 had a decrease in Ach responsiveness at 2 hours, thus the prevalence of endothelial-dependent vasomotor dysfunction at 2 hours post-bypass is 13/15 or 86.6% and at 24 hours it is 11/15 or 73.3%. This is compared to the estimated prevalence of endothelial-independent vasomotor dysfunction (SNP response) at 2 hours being 10/15 or 66.6% and at 24 hours being also being 10/15 or 66.6%.

Since LDPM perfusion measurements are dependent on the concentration of red blood cells, pre-operative hematocrit levels were compared with those measured immediately after surgery and no significant difference was detected (38mg/dL [IQR: 36.5–43.5] vs. 39 [35–41.5], p=0.8). There were also no differences between systolic and diastolic blood pressures during the pre-operative and post-operative (both 2–4 hours and 24 hours post-CPB) perfusion measurements.

Clinical Outcomes

Clinical markers assessed during the first 48 hours post-CPB are listed in Table 2. Serum creatinine measurements were also analyzed pre-operatively and again around 48 hours post-CPB. There was a small but significant rise in creatinine (0.42mg/dL [IQR: 0.4–0.47] vs 0.50 [0.43–0.57], p=0.006). Although the rise in creatinine was significant, it did not cross threshold to meet criteria for Stage 1 pediatric acute kidney injury making this change of questionable clinical significance. There were no deaths during the study period.

Table 2.

Clinical Outcome Markers during Initial 48 Hours Compared to Endothelial Function Index

| Outcome | Result (IQR)(n=17) |

R2 peak EFI at 2–4 hours |

P | R2 AUC EFI at 2–4 hours |

P | R2 peak EFI at 24 hours |

P | R2 AUC EFI at 24 hours |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactate, mg/dL | 1.8 (1.5–3.2) | 0.033 | 0.52 | 0.036 | 0.5 | 0.024 | 0.58 | 0.02 | 0.67 |

| IVF, mL/kg | 262 (146–332.3) | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.153 | 0.15 | 0.004 | 0.82 | 0.001 | 0.93 |

| UOP, mL/kg | 163.8 (129–202.3) | 0.024 | 0.58 | 0.075 | 0.32 | 0.384 | 0.01 | 0.433 | 0.008 |

| Maximum VIS | 3 (0–6.2) | 0.033 | 0.57 | 0.019 | 0.62 | 0* | 0.98 | 0* | 0.99 |

| Mean VIS | 1.2 (0–1.9) | 0.004 | 0.81 | 0.018 | 0.63 | 0.056 | 0.39 | 0.057 | 0.39 |

| Total time intubated, hours | 35.5 (15.5–91) | 0.007 | 0.77 | 0.003 | 0.84 | 0.025 | 0.57 | 0.039 | 0.48 |

IVF=intravenous fluids, UOP=urine output, VIS=vasoactive inotropic score=dopamine dose (μg/kg/min) + dobutamine (μg/kg/min) + 100 × epinephrine dose (μg/kg/min) + 166 × vasopressin dose (units/kg/hr) + 100 × norepinephrine (μg/kg/min), EFI=endothelial function index, AUC=area under the curve

= result less than 10e−3

Total time intubated was collected beyond 48 hours if necessary until patient was successfully extubated for 24 hours.

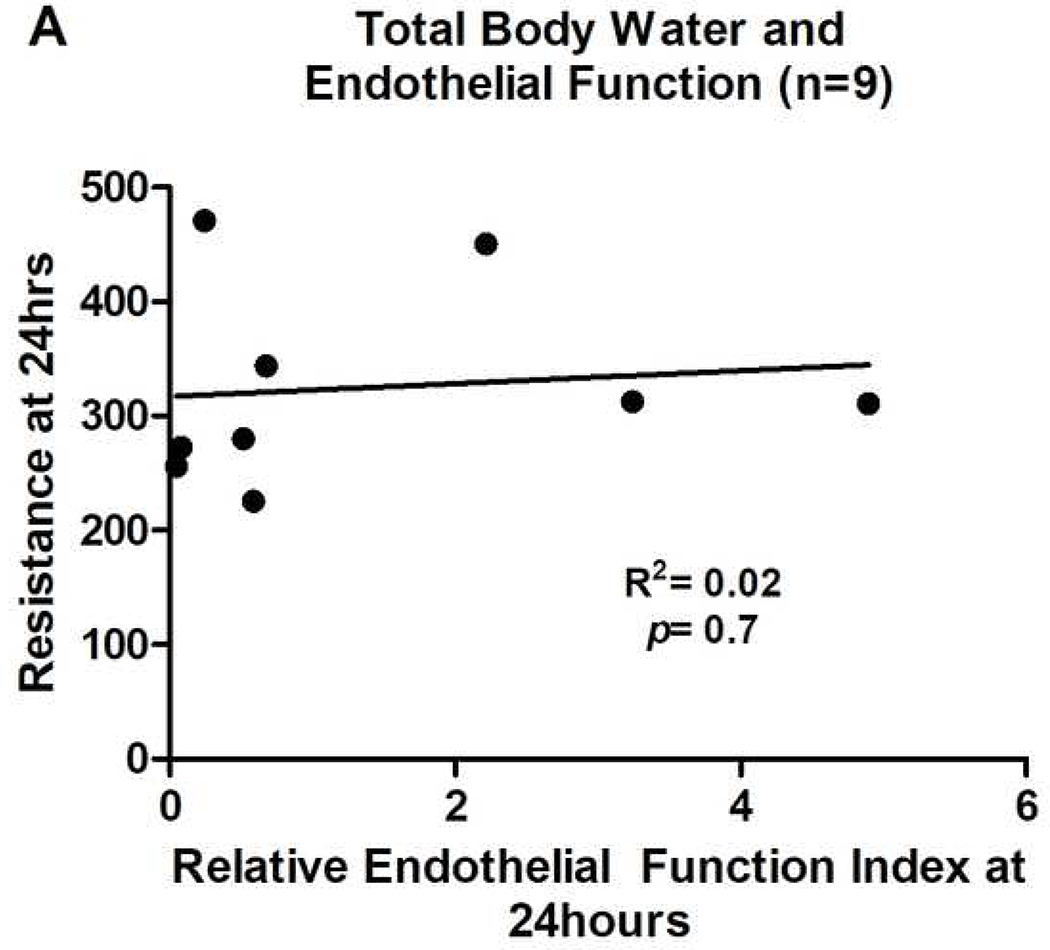

Post-operative increases in total body water as a reflection of capillary leak were added subsequent to initiation of the study, resulting in data being obtained from only 11 patients. There was a significant decrease in resistance values from baseline (571Ω [435.5–614.2]) to 2–4 hours post-CPB (423.5Ω [362.4–493.3], p=0.01) indicating an increase in total body water immediately after bypass. There was an additional significant decrease in resistance values from 2–4 hours (423.5Ω [362.4–493.3]) to 24 hours post-CPB (311.9Ω [268.6–384.1], p=0.002). However, there was no association between resistance and peak or AUC EFI values (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

UOP=urine output. Relative endothelial function index=post-operative ACh response/pre-operative ACh response. All relative endothelial function index values are for AUC results. Results for peak perfusion responses followed the same pattern.

Univariate linear regression was used to compare clinical markers with EFI at 2–4 hours and 24 hours post-CPB. Better endothelium-dependent vasomotor function at 24 hours post-CPB was associated with higher urine output over the first 48 hours post-operatively (R2=0.43, p=0.008) (Figure 3B). While this is an intriguing and further hypothesis generating preliminary association, it should be noted that given the small patient population, a single patient with high urine output and better endothelium dependent vasomotor function could greatly influence the strength of this association. It was also not possible to control for factors that could influence urine output such as diuretics. There were no patients who received renal replacement therapy or peritoneal dialysis during the study period. Endothelial function index did not show a significant relationship with any other clinical parameter.

Biomarker Data

Plasma samples were obtained from 13 patients for biomarker analysis (Supplemental Table 1). There were significant changes at one or both time points in all biomarkers post-CPB except for PECAM-1. Univariate linear regression was used to compare relative endothelial function indices with changes in biomarker levels at 2–4 and 24 hours post-CPB in patients who had paired endothelial-dependent vasomotor function data to look for preliminary associations. No statistically significant relationships were observed.

DISCUSSION

Cardiopulmonary bypass induces a systemic inflammatory response that has been postulated to cause endothelial injury. Utilizing LDPM coupled with drug iontophoresis to measure the endothelium-dependent response to Ach, we now confirm for the first time the presence of profound endothelium-dependent vasomotor dysfunction in infants after CPB. We also confirm the presence of capillary leak and a systemic inflammatory response after CPB through assessment of tissue resistance and inflammatory biomarkers. In our limited patient population, initial regression modeling suggests a relationship between better endothelial responsiveness to Ach at 24 hours post-operatively and higher urine output during the initial 48 hour post-CPB period. Confirmation of this relationship will require further investigation with a larger patient cohort. In addition, despite a significant increase in cytokine levels, that are thought to be associated with worse clinical outcomes, we observed no evidence of a relationship between vasomotor function and cytokine levels (18–20). This will also be important to better delineate with a larger study population because it could have a role in determining whether the mechanism of endothelial injury is linked to the inflammatory milieu following CPB.

Understanding mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction following CBP may have important clinical implications if the observed association with post-operative urine output can be confirmed. Fluid overload and the ability to achieve adequate urine output after aggressive fluid resuscitation have been strongly linked to clinical outcomes and mortality in multiple realms of the pediatric ICU (21, 22). In addition, CPB has been linked with acute kidney injury (AKI) and post-operative outcomes in adults (23). However, a recent study using statins as anti-inflammatory therapy failed to ameliorate AKI after CPB, suggesting a non-inflammatory etiology of renal injury (24). Methods to prevent endothelial injury or recover endothelial vasomotor function after CPB may have the potential to improve post-surgical outcomes.

In healthy adults, acetylcholine-induced cutaneous vasodilation is mediated by a combination of factors, primarily NO• and prostaglandins (25). Proposed causes of impaired endothelial NO• production fall into two general categories: inadequate substrate (L-arginine) for NO• synthesis, and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) dysfunction. The latter can be associated with eNOS “uncoupling”, in which the enzyme transitions from a dimeric, NO•-producing enzyme, to a monomeric state that produces superoxide rather than NO• (26). In regards to possible therapeutic targets, L-arginine can be regenerated from L-citrulline within caveolae, where eNOS is located, by a two-step enzymatic process (27). Therefore, supplementation of either L-arginine or L-citrulline, both of which are depleted during CPB, may protect against pulmonary endothelial dysfunction (28). However, there are no studies looking at the effect of substrate supplementation on peripheral vasomotor dysfunction or other clinical outcomes. eNOS requires tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) as a co-factor and depletion of BH4 promotes uncoupling. Oxidative stress causes oxidation of BH4 and promotes uncoupling of eNOS (29). BH4 supplementation has shown promise for improving endothelial dysfunction after CBP in animal models, but no clinical trials have been attempted (30, 31). Another potential mechanism of eNOS uncoupling is S-glutathionylation of the enzyme by reactive oxygen species. Reversal of S-glutathionylation can restore eNOS function in adults after CPB (32). The primary cause of oxidative stress following CPB is presumably reperfusion injury, but other modifiable stressors such as free hemoglobin leading to toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) activation may also play a role (33, 34). Lastly, the rapid recovery of endothelial function in some patients raises the possibility of a genetic component to recovery of eNOS function, and there is some evidence that eNOS and other polymorphisms can affect capacity for vasodilation (35, 36).

There are significant limitations to the current observational pilot study. The principal limitation was the relatively small sample size. This limited our ability to fully define the change in endothelial-dependent vasomotor dysfunction at 24 hours post-operatively and to more definitively correlate clinical and biochemical outcomes with endothelial-dependent vasomotor dysfunction. Our population was resource limited primarily by personnel availability for recruitment and a desire for single operator consistency with vasomotor reactivity assessments. Despite relatively low numbers, the data suggests that CPB can have a profound effect on endothelial-dependent vasomotor function in infants with presumably normal baseline endothelial function. In addition, it demonstrated a potentially important association between endothelial dysfunction and UOP during the early post-operative period that will need to be more fully defined by examining a larger population. This would also allow correction for diuretic dosing and other confounders that influence UOP. An additional confounder was that two infants enrolled in this study were small for gestational age at birth (less than 10th percentile), which has been associated with reduced endothelial function (13). We were unable to correct for this or do a subgroup analysis; however, data was paired for comparison of pre-operative vs. post-operative vasomotor function which should mitigate bias related to their inclusion in the analysis. Lastly, our study did not assess reproducibility of iontophoresis results using our study equipment and protocol to calculate a coefficient of variability. Performing repeat measurements was not practical due to time constraints, particular with respect to pre-operative measurements due to the need for prolonged cooperation in our patient population of infants. In other studies, variability in peak perfusion and AUC after Ach iontophoresis range from 15–20% in healthy adult volunteers (7, 12–13), but has been confirmed in infants. Design of a future larger scale study would benefit from the use of a healthy control population to establish reproducibility and assist with properly powering patient enrollment.

CONCLUSION

Endothelial-dependent vasomotor dysfunction is present in infants immediately after CPB and recovers in some patients within 24 hours post-CPB. Our data demonstrates a relationship between better endothelial-dependent vasomotor function at 24 hours post-CPB and post-operative urine output over the first 48 hours. This relationship will require a larger patient cohort to fully determine significance of the finding. Future research is needed to further understand the mechanism of endothelial injury and delineate the relationships between endothelial-dependent vasomotor dysfunction and clinical outcomes after CPB.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding: The authors have no conflicts of interest and financial support for this study came from Vanderbilt University Medical Center. RJS is supported by a grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (K08 GM117367).

Copyright form disclosure: Dr. Krispinsky disclosed government work. Dr. Stark’s institution received funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and he received support for article research from the NIH. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Disclaimers: The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, or the United States Government. I am a military service member. This work was prepared as part of my official duties. Title 17 U.S.C. 105 provides that “Copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the United States Government.” Title 17 U.S.C. 101 defines a United States Government work as a work prepared by a military service member or employee of the United States Government as part of that person’s official duties.

REFERENCES

- 1.Warren OJ, Smith AJ, Alexiou C, et al. The inflammatory response to cardiopulmonary bypass: part 1--mechanisms of pathogenesis. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2009;23(2):223–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruel M, Khan TA, Voisine P, et al. Vasomotor dysfunction after cardiac surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2004;26(5):1002–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Panagiotopoulos I, Palatianos G, Michalopoulos A, et al. Alterations in biomarkers of endothelial function following on-pump coronary artery revascularization. J Clin Lab Anal 2010;24(6):389–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lema G, Urzua J, Jalil R, et al. Decreased nitric oxide products in the urine of patients undergoing cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2009;23(2):188–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams HJ, Rebuck N, Elliott MJ, et al. Changes in leucocyte counts and soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and E-selectin during cardiopulmonary bypass in children. Perfusion-Uk 1998;13(5):322–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eikemo H, Sellevold OF, Videm V. Markers for endothelial activation during open heart surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2004;77(1):214–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gomes V, Gomes MB, Tibirica E, et al. Post-operative endothelial dysfunction assessment using laser Doppler perfusion measurement in cardiac surgery patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2014;58(4):468–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Furchgott RF, Zawadzki JV. The obligatory role of endothelial cells in the relaxation of arterial smooth muscle by acetylcholine. Nature 1980;288(5789):373–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tesselaar E, Sjoberg F. Transdermal iontophoresis as an in-vivo technique for studying microvascular physiology. Microvasc Res 2011;81(1):88–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohn JN, Quyyumi AA, Hollenberg NK, et al. Surrogate markers for cardiovascular disease: functional markers. Circulation 2004;109(25 Suppl 1):IV31–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heimhalt-El Hamriti M, Schreiver C, Noerenberg A, et al. Impaired skin microcirculation in paediatric patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2013;12:115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurio GH, Zhiroff KA, Jih LJ, et al. Noninvasive determination of endothelial cell function in the microcirculation in Kawasaki syndrome. Pediatr Cardiol 2008;29(1):121–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin H, Gazelius B, Norman M. Impaired acetylcholine-induced vascular relaxation in low birth weight infants: implications for adult hypertension? Pediatr Res 2000;47(4 Pt 1):457–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin H, Lindblad B, Norman M. Endothelial function in newborn infants is related to folate levels and birth weight. Pediatrics 2007;119(6):1152–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaies MG, Gurney JG, Yen AH, et al. Vasoactive-inotropic score as a predictor of morbidity and mortality in infants after cardiopulmonary bypass. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2010;11(2):234–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harder R, Diedrich A, Whitfield JS, et al. Smart Multi-Frequency Bioelectrical Impedance Spectrometer for BIA and BIVA Applications. IEEE Trans Biomed Circuits Syst 2016;10(4):912–919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Segal KR, Burastero S, Chun A, et al. Estimation of extracellular and total body water by multiple-frequency bioelectrical-impedance measurement. Am J Clin Nutr 1991;54(1):26–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allan CK, Newburger JW, McGrath E, et al. The relationship between inflammatory activation and clinical outcome after infant cardiopulmonary bypass. Anesth Analg 2010;111(5): 1244–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahle WT, Matthews E, Kanter KR, et al. Inflammatory Response After Neonatal Cardiac Surgery and Its Relationship to Clinical Outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giuliano JS Jr., Lahni PM, Bigham MT, et al. Plasma angiopoietin-2 levels increase in children following cardiopulmonary bypass. Intensive Care Med 2008;34(10):1851–1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arikan AA, Zappitelli M, Goldstein SL, et al. Fluid overload is associated with impaired oxygenation and morbidity in critically ill children. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2012;13(3):253–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lex DJ, Toth R, Czobor NR, et al. Fluid Overload Is Associated With Higher Mortality and Morbidity in Pediatric Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgery. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2016;17(4):307–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lopez-Delgado JC, Esteve F, Torrado H, et al. Influence of acute kidney injury on short- and long-term outcomes in patients undergoing cardiac surgery: risk factors and prognostic value of a modified RIFLE classification. Crit Care 2013;17(6):R293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Billings FTt, Hendricks PA, Schildcrout JS, et al. High-Dose Perioperative Atorvastatin and Acute Kidney Injury Following Cardiac Surgery: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2016;315(9):877–888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kellogg DL, Zhao JL, Coey U, et al. Acetylcholine-induced vasodilation is mediated by nitric oxide and prostaglandins in human skin. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2005;98(2):629–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rochette L, Lorin J, Zeller M, et al. Nitric oxide synthase inhibition and oxidative stress in cardiovascular diseases: possible therapeutic targets? Pharmacol Ther 2013;140(3):239–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flam BR, Hartmann PJ, Harrell-Booth M, et al. Caveolar localization of arginine regeneration enzymes, argininosuccinate synthase, and lyase, with endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Nitric Oxide 2001;5(2):187–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith HA, Canter JA, Christian KG, et al. Nitric oxide precursors and congenital heart surgery: a randomized controlled trial of oral citrulline. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2006;132(1):58–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Landmesser U, Dikalov S, Price SR, et al. Oxidation of tetrahydrobiopterin leads to uncoupling of endothelial cell nitric oxide synthase in hypertension. J Clin Invest 2003;111 (8):1201–1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stevens LM, Fortier S, Aubin MC, et al. Effect of tetrahydrobiopterin on selective endothelial dysfunction of epicardial porcine coronary arteries induced by cardiopulmonary bypass. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2006;30(3):464–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Szabo G, Seres L, Soos P, et al. Tetrahydrobiopterin improves cardiac and pulmonary function after cardiopulmonary bypass. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2011;40(3):695–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jayaram R, Goodfellow N, Zhang MH, et al. Molecular mechanisms of myocardial nitroso-redox imbalance during on-pump cardiac surgery. Lancet 2015;385 Suppl 1:S49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ricci Z, Pezzella C, Romagnoli S, et al. High levels of free haemoglobin in neonates and infants undergoing surgery on cardiopulmonary bypass. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2014;19(2): 183–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Belcher JD, Chen C, Nguyen J, et al. Heme triggers TLR4 signaling leading to endothelial cell activation and vaso-occlusion in murine sickle cell disease. Blood 2014;123(3):377–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Messmer-Blust AF, Zhang C, Shie JL, et al. Related transcriptional enhancer factor 1 increases endothelial-dependent microvascular relaxation and proliferation. J Vasc Res 2012;49(3):249–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Figtree GA, Guzik T, Robinson BG, et al. Functional estrogen receptor alpha promoter polymorphism is associated with improved endothelial-dependent vasolidation. Int J Cardiol 2010;143(2):207–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.