Abstract

Introduction

Empagliflozin, a sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitor, is approved in the USA to reduce risk of cardiovascular (CV) death in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and established CV disease, based on EMPA-REG OUTCOME (Empagliflozin Cardiovascular Outcome Event Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients) trial results. Empagliflozin reduced major adverse CV event (MACE) by 14%, CV death by 38%, and hospitalization for heart failure (HHF) by 35% vs placebo, each on top of standard of care (SoC). SGLT-2 inhibitors canagliflozin and dapagliflozin have also been compared with placebo, all on top of SoC, in CV outcome trials. In the CANVAS (Canagliflozin Cardiovascular Assessment Study) Program, canagliflozin reduced MACE by 14% and HHF by 33%. Dapagliflozin reduced HHF by 27% in the DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial (Multicenter Trial to Evaluate the Effect of Dapagliflozin on the Incidence of Cardiovascular Events). This analysis estimated the cost-effectiveness of empagliflozin versus canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, or SoC, in US adults with T2DM and established CV disease.

Research design and methods

Individual patient-level discrete-event simulation was conducted to predict time-to-event for CV and renal outcomes, and specific adverse events over patients’ lifetimes. Occurrence of events in EMPA-REG OUTCOME was estimated based on event-free survival curves with time-dependent covariates. An HR for canagliflozin or dapagliflozin versus empagliflozin on each clinical event was estimated from published CANVAS, DECLARE-TIMI 58, and EMPA-REG OUTCOME data using indirect treatment comparison. Public sources provided US costs and utilities.

Results

The model predicted longer survival for empagliflozin versus canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, and SoC mainly due to direct reduction in CV death. Empagliflozin dominated canagliflozin, yielding more quality-adjusted life years (QALYs; 0.38) at a lower cost (−US$306). Compared with dapagliflozin and SoC, empagliflozin yielded 0.50 and 0.84 incremental QALYs at US$1517 and US$27 539 incremental costs, yielding incremental cost-effectiveness ratios of US$3054/QALY and US$32 848/QALY, respectively.

Conclusions

Empagliflozin was projected to dominate canagliflozin and be highly cost-effective compared with dapagliflozin and SoC using US healthcare costs.

Keywords: type 2 diabetes, cost effectiveness, sodium glucose cotransporter, cardiovascular system

Significance of this study.

What is already known about this subject?

The sodium glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitor (SGLT-2) empagliflozin is Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved to reduce the risk of cardiovascular (CV) death in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and established CV disease (CVD) based on the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial, which showed a significant reduction in the major adverse CV event (3-point MACE: a composite of CV death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke), CV death, and hospitalization for heart failure (HHF) for empagliflozin versus placebo, each in addition to standard of care (SoC).

SGLT-2 therapies canagliflozin and dapagliflozin have FDA approval for different CV indications—canagliflozin to reduce the risk of MACE in patients with T2DM and established CVD based on results from the CANVAS Program, and dapagliflozin to reduce the risk of HHF in patients with T2DM and established CVD or multiple CV risk factors based on results from the DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial.

What are the new findings?

Based on a lifetime cost-effectiveness analysis of empagliflozin plus SoC compared with canagliflozin plus SoC, dapagliflozin plus SoC, or SoC alone, in adults with T2DM and established CVD, empagliflozin plus SoC was projected to dominate canagliflozin plus SoC (ie, cost less and have greater quality-adjusted life years) and be a highly cost-effective therapy compared with dapagliflozin plus SoC and SoC alone.

Results were driven by the reduction in CV death with empagliflozin and were robust to variation in most parameters in sensitivity analyses.

Significance of this study.

How might these results change the focus of research or clinical practice?

The potential of empagliflozin to have a positive health benefit for patients at cost savings to third-party payers in the US healthcare system should be considered by decision makers who determine whether interventions are implemented in clinical practice.

Introduction

The high costs of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in the USA are exacerbated by elevated risks of vascular complications in patients with T2DM, such as myocardial infarction (MI) and hospitalization for heart failure (HHF). One US study attributed between 48% and 64% of the lifetime direct medical cost of T2DM to complications, primarily cardiovascular (CV) disease and nephropathy.1 Another study estimated a national cost of T2DM of US$327 billion, including US$69 billion in increased use of inpatient services and US$71 billion in medication excluding therapies for T2DM.2 Accordingly, T2DM management focuses on reducing complication risks to increase patients’ life expectancy and improve quality of life.3 Although excess risks of complications and premature death in patients with versus without diabetes has been known for years,4 until recently there have been gaps in our understanding of the CV impact of glucose-lowering therapies.5

Several randomised controlled cardiovascular outcome trials (CVOTs) of glucose-lowering drugs have been completed recently. CVOTs that evaluated dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors,6–9 alpha-glucosidase inhibitors,10 and insulin analogues11 yielded neutral findings. In CVOTs of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, liraglutide12 and semaglutide13 showed improvements versus placebo in a composite major adverse CV event (MACE) outcome. Two sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors, empagliflozin14 and canagliflozin,15 demonstrated an improvement in both MACE and HHF versus placebo in CVOTs. Another SGLT-2 inhibitor, dapagliflozin, demonstrated a reduction in HHF versus placebo.16 Among adults with T2DM and chronic kidney disease, canagliflozin showed CV and renal benefits compared with placebo.17

Empagliflozin (10 or 25 mg once daily) was the first glucose-lowering therapy indicated to reduce the risk of CV death in adults with T2DM and established CV disease (CVD) to be approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), based on significant reduction in CV outcomes in EMPA-REG OUTCOME (Empagliflozin Cardiovascular Outcome Event Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients).18 In this CVOT, patients received empagliflozin or placebo in addition to standard of care (SoC) therapy according to local treatment guidelines.14 The SoC in patients with T2DM and established CVD includes multiple drugs for glycemic control and CV risk management taken alone or in combination. Empagliflozin plus SoC significantly reduced the composite outcome of 3-point MACE (CV death, non-fatal MI, and non-fatal stroke; HR 0.86, 95% CI 0.74 to 0.99), with a 38% reduction in CV death (HR 0.62, 95% CI 0.49 to 0.77) versus placebo plus SoC in the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial.14 Moreover, a risk reduction in HHF of 35% (HR 0.65, 95% CI 0.50 to 0.85) for patients receiving empagliflozin versus placebo was also reported.14 The overall benefit-risk profile of empagliflozin in patients with T2DM and established CVD is favourable, although there is a somewhat higher incidence of genital mycotic infection (GMI) in the empagliflozin group (6.4%) compared with the placebo group (1.8%). Canagliflozin (100 or 300 mg once daily) is FDA-approved to reduce the risk of MACE in adults with T2DM and established CVD.19 The CANVAS (Canagliflozin Cardiovascular Assessment Study) trial of canagliflozin plus SoC15 has shown a 14% reduction in composite 3-point MACE (HR 0.86, 95% CI 0.75 to 0.97) and a 33% reduction in HHF (HR 0.67, 95% CI 0.52 to 0.87) compared with placebo plus SoC, although no significant reduction was seen in CV death (HR 0.87, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.06) and results showed an increased risk of bone fracture (HR 1.26, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.52) and lower-limb amputation (LLA; HR 1.97, 95% CI 1.41 to 2.75). Dapagliflozin (10 mg once daily) is FDA-approved to reduce the risk of HHF in adults with T2DM and either established CVD or multiple CV risk factors.20 The DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial (Multicenter Trial to Evaluate the Effect of Dapagliflozin on the Incidence of Cardiovascular Events) of dapagliflozin plus SoC16 showed a 27% reduction in HHF (HR 0.73, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.88) compared with placebo plus SoC, but no significant reduction in MACE (HR 0.93, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.03) or CV death (HR 0.98, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.17). Results of safety analyses showed lower risk versus placebo plus SoC in major hypoglycemic event (HR 0.68, 95% CI 0.49 to 0.95) and acute kidney injury (AKI; HR 0.69, 95% CI 0.55 to 0.87), but an increase in risk of GMI (HR 8.36, 95% CI 4.19 to 16.68).

Quantifying health benefits and net costs is important in understanding the full economic impact of a therapy, which can inform medical decision making and healthcare policy. Differences in clinical outcomes with empagliflozin 10 or 25 mg once daily plus SoC (empagliflozin), canagliflozin 100 or 300 mg once daily plus SoC (canagliflozin), dapagliflozin 10 mg once daily plus SoC (dapagliflozin), or SoC alone (SoC) may impact patients’ life expectancy, quality of life (QoL), and medical costs; thus, comparative analyses are important. The purpose of this study was to compare the cost-effectiveness of empagliflozin versus canagliflozin, versus dapagliflozin, or versus SoC for the treatment of patients with T2DM and established CVD from the perspective of the third-party payer in the US healthcare system.

Methods

Model approach and description

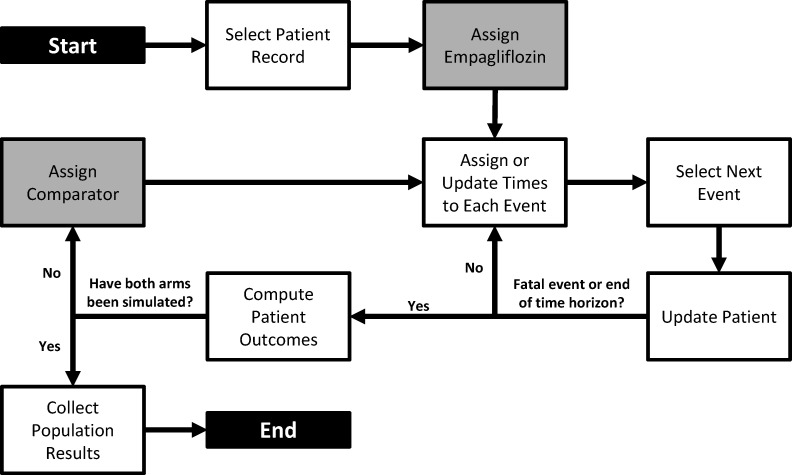

An individual patient-level discrete-event simulation model was developed in Microsoft Excel to track patients’ risk of CV and renal events and adverse events (AEs) over their lifetimes when treated with empagliflozin, canagliflozin, dapagliflozin or SoC (figure 1). This approach was chosen based on a systematic literature review of approaches in modelling hard end points from clinical trials.21 Multiple events for each patient can be captured, with the risk of events changing over time dependent on the type of events previously experienced by the patient and their clinical characteristics (eg, age, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c)).

Figure 1.

Diagram of the simulation model process.

The simulation began by generating a cohort of patients with T2DM and established CVD. Patients were duplicated and assigned to each therapy arm. Based on patients’ CV risk profiles, the model simulated nine possible CV or renal events that corresponded to end points in EMPA-REG OUTCOME and published data from CANVAS and DECLARE-TIMI 58: CV death, non-fatal MI, non-fatal stroke (the primary outcome in EMPA-REG OUTCOME, CANVAS, and DECLARE-TIMI 58 was a composite of these three events), HHF, progression of albuminuria (a primary outcome in CANVAS-R), a composite renal outcome (defined as a 40% reduction in estimated glomerular filtration rate, renal replacement therapy, or renal death), hospitalization for unstable angina (UA), transient ischemic attack (TIA), and revascularization (online supplemental table OS1).14 15 Recurrent non-fatal CV events were permitted in the model (eg, a simulated patient may experience more than one non-fatal MI), but renal events were considered non-recurring. Selected AEs in the model were GMI, AKI, LLA, bone fracture, and major hypoglycemic event.

bmjdrc-2020-001313supp001.pdf (479KB, pdf)

For each simulated patient, the time-to-event for CV, renal events, and AEs were estimated. Then the model compared the timing of all events, and the earliest time determined which event happened first. When any non-fatal event occurred, the patient remained in the model and their treatment history, risk of future events, and time to next event were updated. The model process repeated to identify the next event. Non-fatal events could recur and influence the patient’s risk (or experience) of future events. If a fatal event occurred or the end of the time horizon was reached, the simulation of the patient ended, and the model moved to the next patient. For each patient, cumulative events per 100 patients-years (PYs), cumulative costs of management, life years, and quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) were tracked. Once all patients had been simulated on all treatments, the individual patient outcomes were aggregated to compute the mean population outcomes.

Population baseline characteristics

Individual patient profiles were created (see online supplemental file 1) based on the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial population baseline characteristics previously published.14 Each sampled profile was duplicated, and identical copies were simulated for empagliflozin and each comparator (canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, and SoC) so that treatment comparisons captured observed incremental treatment effects, and were not influenced by differences in patient characteristics.

Risk equations

Time-dependent parametric survival analyses of the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial data were conducted to characterise CV and renal event rates over time under SoC and empagliflozin. An individual patient-level risk equation was developed for each CV and renal event in the model using a systematic two-stage analysis. First, event-free survival (EFS) curves were fit to the trial data to describe the population-level occurrence of each CV and renal event. Second, individual patient-level estimates of risk were generated by testing baseline and time-dependent patient characteristics as potential predictors of the outcomes in parametric proportional-hazards regression analyses. Details on statistical analyses and risk equations included in the economic model are provided in online supplemental table OS2. To validate that the derived risk equations reproduced the overall event rates in the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial when treated as competing events, the model was run for a 3-year time horizon to match the mean trial follow-up duration. Predicted 3-year HRs for empagliflozin versus SoC were congruent with the trial data (online supplemental table OS3).

US life table data were used to predict risk of non-cardiac death in simulated patients. An exponential-shaped EFS curve was assumed to estimate risk of AEs from published data.

Relative treatment effects

Head-to-head trial data were not available, thus treatment effects of SGLT2 inhibitors against the common placebo comparator were used to derive indirect estimates of the relative effect of canagliflozin versus empagliflozin and dapagliflozin versus empagliflozin using the indirect treatment comparison (ITC) method previously described by Bucher et al.22

The publications for EMPA-REG OUTCOME,14 CANVAS Program,15 and DECLARE-TIMI 5816 were used for the ITC. Outcomes from the CREDENCE trial (canagliflozin) were not used for comparison due to population differences.17 A standard process was followed to assess whether an ITC was feasible in terms of CV and renal outcomes (details in online supplemental file 1).

The feasibility analysis concluded the control arms could serve as the common comparator. In all CVOTs, use of SoC therapies was encouraged in line with local treatment guidelines, and not restricted to a specific type of SoC. Some differences were identified across the CVOTs with regard to inclusion criteria, baseline demographic and clinical characteristics, concomitant CV medications, history of CVD and outcome definitions (online supplemental table OS4 and table OS5). Mean age, percentage female, and most clinical characteristics (eg, HbA1c, BMI, SBP) were homogeneous across the CVOTs. There was heterogeneity across the CVOTs with respect to renal function, particularly between the EMPA-REG OUTCOME and DECLARE-TIMI 58 trials. Clinical history (prior PAD, MI, stroke, HF) was not consistently reported and showed some heterogeneity across the trials. Concomitant CV medications were generally similar between EMPA-REG OUTCOME and the CANVAS Program; some differences between EMPA-REG OUTCOME and DECLARE-TIMI 58 were observed in baseline treatment with beta-blockers and lipid-lowering therapy. The proportion of patients with established CVD at baseline varied from 100% in EMPA-REG OUTCOME, 65.6% in the CANVAS Program, and 40.6% in DECLARE-TIMI 58. Published subpopulation data were available from the CANVAS Program23 and DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial16 for patients with established CVD at baseline. Thus, it was possible to reduce the heterogeneity between the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial and the CANVAS Program and DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial populations by using this subpopulation data for patients with baseline CVD to inform the ITC. Intent-to-treat (ITT) population data were used to derive relative efficacy parameters for scenario analyses. The definitions of clinical events were not identical, but the differences were modest and considered not to preclude the feasibility of an ITC.

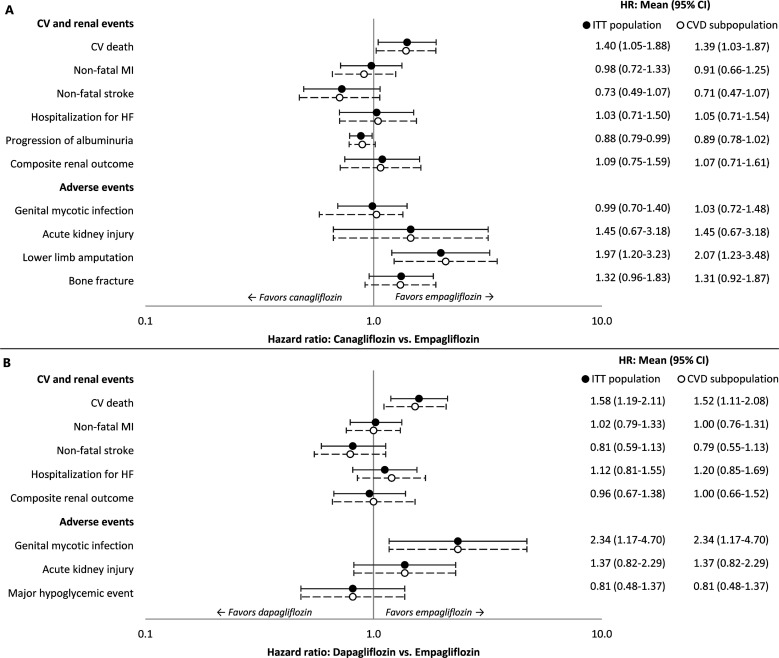

HRs with 95% CIs for canagliflozin versus empagliflozin and dapagliflozin versus empagliflozin are shown in figure 2A, B, respectively. The survival functions for each of the CV and renal events were used to estimate risk of clinical events for empagliflozin, and this risk was adjusted for canagliflozin and dapagliflozin using the HRs. The AE rates for empagliflozin were similarly adjusted.

Figure 2.

HRs of event rates for sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 therapies versus empagliflozin. (A) canagliflozin versus empagliflozin, (B) dapagliflozin versus empagliflozin. Studies included in the indirect treatment comparison: EMPA-REG OUTCOME, CANVAS Program, and DECLARE-TIMI 58. CV, cardiovascular; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HF, heart failure; ITT, intent-to-treat; MI, myocardial infarction.

Quality of life

Published health utility scores were obtained from studies of patients with T2DM.24–26 Health-related utilities were computed by applying permanent event disutilities to a baseline utility value (online supplemental table OS6). As patients accumulated multiple clinical events, the total combined utility decrement was adjusted based on the number of events experienced to account for overlapping effects.26 QALYs consisted of the number of life years (ie, length of survival from model initiation to death or until the time horizon expires) weighted by the utility score associated with each of those years.

Costs and perspective

Direct costs were accrued in 2020 US$ (online supplemental table OS7). The model simulated commercially insured and Medicare populations separately and overall.

Treatment costs were based on published27 wholesale acquisition costs (WAC) of empagliflozin, canagliflozin, and dapagliflozin. Costs to the health plan were computed net of a US$35 patient co-pay28 and rebate (assumed to be 50% in commercially insured patients, 53% in Medicare patients, or 51% overall weighted based on patients in EMPA-REG OUTCOME). Pharmacy costs for SoC therapies and all other regular disease management and monitoring costs were assumed to be the same across regimens and were therefore not included in the model.

Acute costs of care for each clinical event were identified for commercial29–32 and Medicare31–33 payers and inflated to 2020 prices using the medical component of the US consumer price index.29 31 32 34 For each event, the model used an average of the commercial and Medicare costs, weighted by the per cent of patients below age 65 years at baseline. Non-CV death events were assumed to incur no costs.

Model assumptions

A few key additional modeling assumptions were made. First, changes in the risk of clinical events due to changes in treatment were implicitly captured in event rate trajectories. The statistical analyses of EMPA-REG OUTCOME data quantified associations among time-dependent risk factors. Event histories were predictors across other events, creating coupled, time-dependent risk equations (ie, as events accumulate, they can alter the risk of future events). Second, regardless of changes in event or treatment history, a constant treatment effect was assumed for each event. Proportional-hazards models assumed that the effect of the covariates on the hazard rate was the same at all times. Third, unmodeled comorbidities were assumed to not significantly influence the shapes of the statistical extrapolations or the role of specific risk predictors. The role of any baseline confounders not influenced by empagliflozin was minimized by the trial randomization process, which insured balance between treatment arms.

Model analyses

In the base case, a lifetime horizon was selected to fully capture costs and QoL associated with each treatment. Future costs and QALYs were discounted at a 3.0% annual rate. Relative clinical effects of canagliflozin and dapagliflozin versus empagliflozin for patients with baseline CVD in the CANVAS Program and DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial, respectively, were used. The analysis for empagliflozin versus canagliflozin excluded hospitalization for UA, TIA, and revascularization, because these were not published outcomes of the CANVAS Program, but included GMI, AKI, LLA, and bone fracture AEs. For empagliflozin versus dapagliflozin, the analysis excluded hospitalization for UA, TIA, revascularization, and progression of albuminuria, as these were not published outcomes in DECLARE-TIMI 58, but included GMI, AKI, and major hypoglycemic event AEs. All nine CV and renal events from EMPA-REG OUTCOME were included in the empagliflozin versus SoC analysis, plus GMI and AKI AEs. EMPA-REG OUTCOME data indicated that GMI and AKI occurred at significantly different rates (p<0.05) between treatment arms.

Deterministic sensitivity analyses were conducted to evaluate the robustness of the model inputs and assumptions. The model varied discount rates, empagliflozin treatment effect, and relative efficacy of comparators (notably, comparator HRs vs empagliflozin using their 95% CIs and ITT population data), utilities, and costs. A probabilistic sensitivity analysis was performed using distributions reflecting parameter uncertainties (online supplemental table OS8).35 Risk equation coefficients derived from EMPA-REG OUTCOME were varied using Cholesky decomposition, and the comparator HRs versus empagliflozin derived from ITCs were varied over their 95% CIs using a lognormal distribution. The model produced 1000 pairs of incremental effectiveness and cost estimates. Scenario analyses assessed the impact of shorter time horizons (1, 3, 5, and 10 years).

Results

Base-case analysis

Patients receiving empagliflozin were predicted to survive longer due to lower rates of CV death versus canagliflozin (incremental −0.56 events/100 PY), dapagliflozin (incremental −0.58 events/100 PY), and SoC (incremental −1.29 events/100 PY) (table 1; see additional details in online supplemental table OS9). When compared with canagliflozin, empagliflozin had lower rates of progression of albuminuria, LLA, AKI, and bone fracture; similar rates of HHF, composite renal outcome, and GMI but higher rates of non-fatal MI and non-fatal stroke. When compared with dapagliflozin, empagliflozin had lower rates of GMI and AKI; similar rates of non-fatal MI, HHF, and composite renal outcome but higher rates of non-fatal stroke. Relative to SoC, empagliflozin had lower rates of non-fatal MI, HHF, revascularization, progression of albuminuria, composite renal outcome, and AKI; similar rates of hospitalization for UA and TIA but higher rates of non-fatal stroke and GMI.

Table 1.

Simulation model base case incremental results over a lifetime horizon

| Empagliflozin versus canagliflozin | Empagliflozin versus dapagliflozin | Empagliflozin versus SoC | |

| CV and renal event rates per 100 PYs | |||

| CV death | −0.56 | −0.58 | −1.29 |

| Non-fatal MI | 0.21 | 0.03 | −0.33 |

| Non-fatal stroke | 0.38 | 0.24 | 0.24 |

| Hospitalization for HF | 0.05 | −0.08 | −1.02 |

| Progression of albuminuria | −0.16 | – | −0.86 |

| Composite renal outcome | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.64 |

| Hospitalization for UA | – | – | 0.04 |

| Transient ischemic attack | – | – | −0.04 |

| Revascularization | – | – | −0.20 |

| Non-CV death | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.32 |

| AE rates per 100 PYs | |||

| Genital mycotic infection | −0.06 | −1.47 | 1.16 |

| Acute kidney injury | −0.14 | −0.11 | −0.23 |

| Lower limb amputation | −0.55 | – | – |

| Bone fracture | −0.29 | – | – |

| Major hypoglycemic event | – | 0.08 | – |

| Undiscounted life expectancy (years) | 0.80 | 1.09 | 1.77 |

| Discounted QALY | 0.38 | 0.50 | 0.84 |

| Discounted costs over patients’ lifetime | |||

| Drug acquisition cost, US$ | 1675 | 2917 | 31 539 |

| CV/renal event management cost, US$ | 13 | −1558 | −4.070 |

| AE management cost, US$ | −1994 | 157 | 70 |

| Total cost, US$ | −306 | 1517 | 27 539 |

| ICER, US$/LY | Dominates | 1398 | 15 524 |

| ICER, US$/QALY | Dominates | 3054 | 32 848 |

AE, adverse event; CV, cardiovascular; HF, heart failure; ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; LY, life year; MI, myocardial infarction; PY, patient-year; QALY, quality-adjusted life year; SoC, standard of care; UA, unstable angina.

Simulated patients receiving empagliflozin were estimated to have a higher rate of non-CV-related mortality than those on comparator treatments. Since a lifetime time horizon was applied, every patient in the model experienced a terminal death event. Given the reductions in CV death for patients receiving empagliflozin, these patients survived longer, and their increased age led to an increase in the estimated non-CV death rates.

Longer overall survival and reduced rates of clinical events translated to incremental QALYs gained for empagliflozin versus canagliflozin (0.38), dapagliflozin (0.50), and SoC (0.84). The total net cost per patient was −US$306 vs canagliflozin, US$1517 vs dapagliflozin, and US$27 539 vs SoC. Savings from management of fewer clinical events with empagliflozin offset (for canagliflozin) or partially offset (for dapagliflozin and SoC) the additional drug cost due to extended survival. Empagliflozin showed dominance36 (cost less and had higher QALYs) over canagliflozin and yielded ICERs of US$3054/QALY and US$32 848/QALY versus dapagliflozin and SoC, respectively.

Sensitivity analyses

Empagliflozin remained dominant over canagliflozin in the majority of deterministic sensitivity analyses (table 2), and ICERs ranged from US$246/QALY to US$16 738/QALY in the remaining analyses. Empagliflozin was dominant over dapagliflozin in several pricing scenarios and when the treatment effect of dapagliflozin was worsened (applying the dapagliflozin vs empagliflozin HR 95% CI upper limit). Reducing HRs for the comparator SGLT-2 treatment versus empagliflozin (favouring the comparators) had the largest impact on cost-effectiveness results. Empagliflozin remained cost-effective compared with SoC, with ICERs ranging from US$20 438/QALY (no discount rate on health outcomes) to US$52 666/QALY (commercial perspective). All ICERs fell below the US$100 000/QALY US cost-effectiveness threshold.37

Table 2.

Sensitivity analyses results

| ICER-QALY for low and high scenario values (US$) | ||||||

| Empagliflozin versus canagliflozin | Empagliflozin versus dapagliflozin | Empagliflozin versus SoC | ||||

| Low | High | Low | High | Low | High | |

| Perspective, Medicare | * | NA | 787 | NA | 23 255 | NA |

| Perspective, commercial | * | NA | 4174 | NA | 52 666 | NA |

| Discount rate, cost: 0%–5% | 1372 | * | 6044 | 1964 | 44 899 | 27 497 |

| Discount rate, health: 0%–5% | * | * | 1827 | 4136 | 20 438 | 43 673 |

| Baseline CV/renal event rates HR:±10% | * | * | 2984 | 3116 | 22 803 | 51 384 |

| HRs versus empagliflozin: 95% CI | † | * | † | * | NA | NA |

| HRs versus empagliflozin: ITT population | * | NA | 2665 | NA | NA | NA |

| Drug cost, empagliflozin: ±20% | * | 16 738 | * | 18 360 | 24 792 | 40 904 |

| Rebate percentage, empagliflozin:±20% | 8530 | * | 11 199 | * | 37 135 | 28 561 |

| Rebate percentage, comparator:±20% | * | 8026 | * | 10 529 | NA | NA |

| CV/renal event management cost:±20% | * | * | 3681 | 2427 | 33 819 | 31 877 |

| AE management cost: ±20% | 246 | * | 2991 | 3117 | 32 831 | 32 865 |

| Baseline utility: 95% CI | * | * | 3070 | 3039 | 33 017 | 32 681 |

| Utility decrements, CV/renal events: 95% CI | * | * | 3104 | 3007 | 33 100 | 32 624 |

| Utility decrements, AEs: 95% CI | * | * | 2970 | 3083 | 33 218 | 32 713 |

*Empagliflozin is less costly and more effective than the comparator.

†The comparator is less costly and more effective than empagliflozin.

AE, adverse event; CV, cardiovascular; ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; ITT, intent-to-treat; NA, not applicable; QALY, quality-adjusted life year; SoC, standard of care.

In probabilistic sensitivity analyses, the ICER (US$/QALY) scatter plot demonstrated that empagliflozin always yielded more QALYs than canagliflozin, and empagliflozin was less expensive compared with canagliflozin in the majority of model iterations. In 88% of cases, empagliflozin dominated canagliflozin (ie, points fall in the southeast quadrant of the scatter plot; online supplemental figure OS1). The iterations for empagliflozin versus dapagliflozin yielded a mean ICER of US$2811/QALY (95% CI US$1597/QALY–US$3918/QALY), with all iterations below a stringent US$50 000/QALY cost-effectiveness threshold.37 Empagliflozin was more expensive and more effective in terms of QALYs gained compared with SoC (99.8% of iterations were below US$150 000/QALY). The mean (95% CI) ICER for empagliflozin versus SoC was US$36 387/QALY (US$21 724/QALY–US$62 859/QALY). These results are based on the clinical event rates shown in online supplemental table OS10.

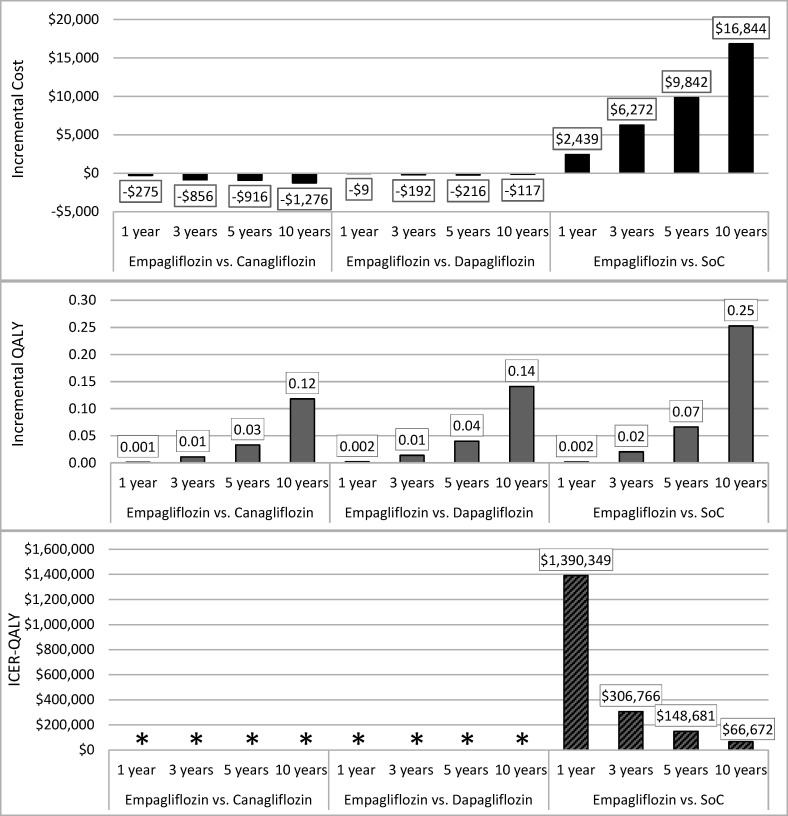

Scenario analyses

Changing the time horizon (1–10 years) did not have an effect on the direction of results (figure 3). Empagliflozin was dominant (less costly, more effective) over both canagliflozin and dapagliflozin over the shorter durations. Empagliflozin remained cost-effective relative to SoC over 10 years (US$66 672/QALY) and 5 years (US$148 681/QALY) at US$100 000/QALY and US$150 000/QALY thresholds,37 respectively.

Figure 3.

Short-term analyses with different time horizons. *Empagliflozin is less costly and more effective than the comparator. ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; QALY, quality-adjusted life year; SoC, standard of care.

Discussion

Patients with T2DM have increased risks of microvascular/macrovascular complications and premature death, with increased medical expenditures. Emerging evidence from CVOTs suggests a CV protective role for newer medications in people with T2DM and established CVD. Pharmacoeconomic evaluation can translate observed reductions in CV events to savings in healthcare expenditure and quantify the value of glucose-lowering drugs. This health economic evaluation demonstrated the benefits of empagliflozin compared with canagliflozin or dapagliflozin as an addition to SoC or SoC alone in the USA from a payer perspective, suggesting that empagliflozin economically dominates canagliflozin (ie, provides greater health benefits at a lower cost) and is highly cost-effective compared with dapagliflozin and SoC. The findings showed some sensitivity of results to drug rebates and parameters that affect clinical event risks; however, empagliflozin was consistently the dominant or cost-effective treatment.

Existing studies have performed similar analyses for empagliflozin versus SoC in various settings based on patient-level data from EMPA-REG OUTCOME, drawing consistent conclusions with our analysis about cost-effectiveness.38–42 Differences in model design, inputs, and assumptions, make it difficult to compare our model with other published cost-effectiveness analysis for empagliflozin versus comparators in patients with T2DM and established CVD. However, a targeted literature search identified one key US payer-perspective cost-effectiveness study with a treatment comparison included in our model. A study that used a Markov model to estimate the lifetime cost-effectiveness of empagliflozin versus SoC in the USA based on EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial data found that empagliflozin was associated with higher costs (US$98 484 per patient) and more QALYs (1.29) compared with SoC, yielding an ICER of US$76 167/QALY, still below the US cost-effectiveness threshold (US$100 000/QALY).43 Although not a cost-effectiveness analysis, another published study evaluated costs avoided (in 2016 US$) for patients treated with canagliflozin and empagliflozin in a US commercially insured population aged <65 years.44 That study found a positive cost avoidance for each treatment, based on unadjusted clinical event rates and assuming independent non-recurrent events, for each treatment versus placebo from CANVAS and EMPA-REG OUTCOME. Only CV event costs were captured; no costs associated with drug utilization, renal events, or AEs were included in their analysis. No studies including empagliflozin and dapagliflozin were identified.

This model directly predicted clinical event rates exclusively using data from the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial, CANVAS Program, and DECLARE-TIMI 58, requiring no extrapolated changes in surrogate biomarkers. Drug pricing was conservative, assuming no difference in the costs of treatment between arms other than the presence of SGLT-2 treatment, and that treatment was never discontinued. Empagliflozin’s survival benefit and thus longer treatment duration contribute to the higher pharmacy cost of empagliflozin versus comparator treatments, and discontinuation would help reduce this cost. Three-year overall outcomes from the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial were closely reproducible by the model.

Limitations of this model should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the clinical event rates observed in EMPA-REG OUTCOME were based on controlled trial settings and may not be reproduced in clinical practice. This is a typical limitation of interpreting any trial outcomes. However, the CVOT designs were not prescriptive to the type of SoC, instead calling for the usual SoC in controlling HbA1c and CV risk factors according to local treatment guidelines, thus improving the likelihood of direct relevance to clinical practice. Next, the relative effects of canagliflozin or dapagliflozin versus empagliflozin on each modeled clinical event were estimated based on ITC rather than direct trial comparisons. The ITC was informed by data from CVOTs for empagliflozin (EMPA-REG OUTCOME),14 canagliflozin (CANVAS Program; integrated analysis of CANVAS and CANVAS-R),15 and dapagliflozin (DECLARE-TIMI 58),16 with efficacy parameters stratified by baseline presence of CVD. We acknowledge the possibility of misclassification in the trial data, in that baseline presence of established CVD was investigator-reported and some participants could have had undiagnosed CVD. Sensitivity analyses using treatment effect in the ITT population for canagliflozin (empagliflozin was dominant) and dapagliflozin (US$2665/QALY) showed little variation in the results. In addition, treatment intensification beyond the trial duration cannot be easily captured in the model; thus, conservative treatment assumptions were used. Downstream treatment may affect clinical and cost outcomes observed in real-world practice. Model outcomes were sensitive to the impact of subsequent events of the same type on future event rates (eg, survivors of acute MI are at elevated risk of recurrent MI and other CV events, such as stroke), but there were relatively few data from the trials to estimate the change in risk associated with recurrent events. The model does not capture recognized but relatively mild AEs (eg, polyuria, episodes of dehydration) or rare complications (ie, diabetic ketoacidosis) of SGLT-2 inhibitors; these were not observed in sufficient numbers in the trials.

Conclusions

This research evaluated the lifetime cost-effectiveness of empagliflozin versus canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, and SoC in patients with T2DM and established CVD in the USA, by implementing an economic model that draws on the results of the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial (all patients had CVD), CANVAS Program CVD subpopulation and DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial CVD subpopulation. Findings suggest that prescribing empagliflozin in addition to SoC for the treatment of patients with T2DM and CVD leads to substantial health benefits and is a dominant (vs canagliflozin plus SoC) or cost-effective (vs dapagliflozin plus SoC or SoC) treatment option from the perspective of US payers, and may assist patients, clinicians, and decision makers in the selection of a regimen for the management of T2DM and CVD.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Samuel Mettam, formerly of Boehringer Ingelheim, for his contribution to the empagliflozin versus dapagliflozin cost-effectiveness analysis. The authors also gratefully acknowledge Janet Dooley of the Evidera Editorial and Design team for her editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the interpretation of data and results and drafting the manuscript. Additionally, OSR, ARK, LC, and SBB contributed to the model development, identification of data sources, conduct of analyses, and implementation of the design. KF performed the indirect treatment comparison. PKG, EP, and AU reviewed the final model design, data sources, and results.

Funding: Sponsorship for this study and article processing charges were funded by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH & Co KG of Ingelheim am Rhein, Germany. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. Editorial assistance in the preparation of this article was provided by Janet Dooley of Evidera’s Editorial and Design Services team. Support for this assistance was funded by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Competing interests: OSR, SBB, and KF are employees of Evidera, which provides consulting and other research services to the biopharmaceutical industry. ARK and LC were employees of Evidera during the conduct of this study and development of this article, but are now employed elsewhere. In their salaried positions, Evidera employees work with a variety of companies and organizations, and are precluded from receiving any payment or honoraria directly from these organisations for services rendered. Evidera received funding from Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH & Co KG. EP and AU are current employees of Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH & Co. KG of Ingelheim am Rhein, Germany. PKG was an employee of Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc. in Ridgefield, Connecticut, USA during the conduct of this study and development of this article, but he is now employed elsewhere.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Our study data (which is based on de-identified data from a clinical trial) is not in a repository, but is available on reasonable request from the corresponding author (ORCiD 0000-0003-0714-5619).

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

We used de-identified data from a clinical trial involving human participants, but we did not deal with or report on any specific participants, so we did not seek ethics committee approval.

References

- 1. Zhuo X, Zhang P, Hoerger TJ. Lifetime direct medical costs of treating type 2 diabetes and diabetic complications. Am J Prev Med 2013;45:253–61. 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. American Diabetes Association . Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2017. Diabetes Care 2018;41:917–28. 10.2337/dci18-0007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Marshall SM, Flyvbjerg A. Prevention and early detection of vascular complications of diabetes. BMJ 2006;333:475–80. 10.1136/bmj.38922.650521.80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mahmood SS, Levy D, Vasan RS, et al. The Framingham heart study and the epidemiology of cardiovascular disease: a historical perspective. Lancet 2014;383:999–1008. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61752-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cefalu WT, Kaul S, Gerstein HC, et al. Cardiovascular Outcomes Trials in Type 2 Diabetes: Where Do We Go From Here? Reflections From a Diabetes Care Editors' Expert Forum. Diabetes Care 2018;41:14–31. 10.2337/dci17-0057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Green JB, Bethel MA, Armstrong PW, et al. Effect of sitagliptin on cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2015;373:232–42. 10.1056/NEJMoa1501352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Scirica BM, Bhatt DL, Braunwald E, et al. Saxagliptin and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1317–26. 10.1056/NEJMoa1307684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. White WB, Cannon CP, Heller SR, et al. Alogliptin after acute coronary syndrome in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1327–35. 10.1056/NEJMoa1305889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rosenstock J, Perkovic V, Johansen OE, et al. Effect of linagliptin vs placebo on major cardiovascular events in adults with type 2 diabetes and high cardiovascular and renal risk: the CARMELINA randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2019;321:69–79. 10.1001/jama.2018.18269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Holman RR, Coleman RL, Chan JCN, et al. Effects of acarbose on cardiovascular and diabetes outcomes in patients with coronary heart disease and impaired glucose tolerance (ACE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2017;5:877–86. 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30309-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Marso SP, McGuire DK, Zinman B, et al. Efficacy and safety of Degludec versus Glargine in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2017;377:723–32. 10.1056/NEJMoa1615692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, et al. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2016;375:311–22. 10.1056/NEJMoa1603827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Marso SP, Bain SC, Consoli A, et al. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1834–44. 10.1056/NEJMoa1607141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, et al. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2117–28. 10.1056/NEJMoa1504720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Neal B, Perkovic V, Mahaffey KW, et al. Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal events in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2017;377:644–57. 10.1056/NEJMoa1611925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wiviott SD, Raz I, Bonaca MP, et al. Dapagliflozin and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2019;380:347–57. 10.1056/NEJMoa1812389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, et al. Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med 2019;380:2295–306. 10.1056/NEJMoa1811744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH. Jardiance (empagliflozin) [package insert], 2020. Available: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/204629s023lbl.pdf [Accessed 23 Aug 2020].

- 19. Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies. Invokana (canagliflozin) [package insert], 2020. Available: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/204042s034lbl.pdf [Accessed 23 Aug 2020].

- 20. AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals. Farxiga (dapagliflozin) [package insert], 2020. Available: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2020/202293s020lbl.pdf [Accessed 23 Aug 2020].

- 21. Kansal AR, Zheng Y, Palencia R, et al. Modeling hard clinical end-point data in economic analyses. J Med Econ 2013;16:1327–43. 10.3111/13696998.2013.838960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bucher HC, Guyatt GH, Griffith LE, et al. The results of direct and indirect treatment comparisons in meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Epidemiol 1997;50:683–91. 10.1016/S0895-4356(97)00049-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mahaffey KW, Neal B, Perkovic V, et al. Canagliflozin for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular events: results from the canvas program (canagliflozin cardiovascular assessment study). Circulation 2018;137:323–34. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Grandy S, Fox KM, SHIELD Study Group . Change in health status (EQ-5D) over 5 years among individuals with and without type 2 diabetes mellitus in the shield longitudinal study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2012;10:99. 10.1186/1477-7525-10-99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lindgren P, Graff J, Olsson AG, et al. Cost-Effectiveness of high-dose atorvastatin compared with regular dose simvastatin. Eur Heart J 2007;28:1448–53. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sullivan PW, Ghushchyan VH. EQ-5D scores for diabetes-related comorbidities. Value Health 2016;19:1002–8. 10.1016/j.jval.2016.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Red book Online® Micromedex clinical knowledge suite, IBM Watson health (formerly owned by Truven health analytics), 2020. Available: http://www.micromedexsolutions.com/home/dispatch [Accessed May 2020].

- 28. United benefit advisors (UBA). UBA special report: trends in prescription drug benefits, 2016. Available: http://cdn2.hubspot.net/hubfs/182985/docs/UBA_SPECIAL_REPORT-_Trends_in_Prescription_Drug_Benefits_Brochure-Web.pdf [Accessed 1 Aug 2018].

- 29. Shetty S, Stafkey-Mailey D, Yue B. The direct cost of cardiovascular disease-related death in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in a commercially-insured population in the United States. poster PC-00198. AMCP 2016 Nexus National Harbor, MD, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 30. InHealth Professional Services . InHealth 2020 Physicians’ Fee & Coding Guide. Atlanta, GA: InHealth Professional Services, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Healthcare cost and utilization project (HCUP), agency for healthcare research and quality (AHRQ). HCUPnet. weighted national estimates from HCUP national inpatient sample (NIS), 2016, agency for healthcare research and quality (AHRQ), based on data collected by individual states and provided to AHRQ by the states. total number of weighted discharges in the U.S. based on HCUP NIS = 35,675,421. statistics by principal Diagnosis/Procedure and payer (insurance status), 2016. Available: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp [Accessed May 2020].

- 32. United States Renal Data System (USRDS) . 2018 USRDS annual data report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2018. https://www.usrds.org/annual-data-report/previous-adrs/ [Google Scholar]

- 33. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid services (CMS). physician fee schedule Look-up tool. 2020 national payment amount Non-facility fee, 2020. Available: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/PhysicianFeeSched/ [Accessed May 2020].

- 34. Bureau of Labor Statistics, United States Department of Labor . Consumer price index 2018: medical care, 2018. Available: https://stats.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm [Accessed May 2020].

- 35. Briggs AH, Weinstein MC, Fenwick EAL, et al. Model parameter estimation and uncertainty: a report of the ISPOR-SMDM Modeling Good Research Practices Task Force--6. Value Health 2012;15:835–42. 10.1016/j.jval.2012.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cohen DJ, Reynolds MR. Interpreting the results of cost-effectiveness studies. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:2119–26. 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.09.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) . Overview of the ICER value assessment framework and update for 2017-2019 2017. Available: http://icer-review.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/ICER-value-assessment-framework-Updated-050818.pdf [Accessed 1 Aug 2018].

- 38. Gourzoulidis G, Tzanetakos C, Ioannidis I, et al. Cost-Effectiveness of Empagliflozin for the treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus at increased cardiovascular risk in Greece. Clin Drug Investig 2018;38:417–26. 10.1007/s40261-018-0620-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Iannazzo S, Mannucci E, Reifsnider O, et al. Cost-Effectiveness analysis of empagliflozin in the treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes and established cardiovascular disease in Italy, based on the results of the EMPA-REG outcome study. FE 2017;18:43–53. 10.7175/fe.v18i1.1332 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kaku K, Haneda M, Sakamaki H, et al. Cost-Effectiveness analysis of Empagliflozin in Japan based on results from the Asian subpopulation in the EMPA-REG outcome trial. Clin Ther 2019;41:2021–40. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2019.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kansal A, Reifsnider OS, Proskorovsky I, et al. Cost-Effectiveness analysis of empagliflozin treatment in people with type 2 diabetes and established cardiovascular disease in the EMPA-REG outcome trial. Diabet Med 2019;36:1494–502. 10.1111/dme.14076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mettam SR, Bajaj H, Kansal AR. Cost effectiveness of empagliflozin in patients with T2DM and high cv risk in Canada. Abstract PDB52 at ISPOR 19th annual European Congress, 29 October-2 November 2016, Vienna Austria. Value Health 2016;19:A674. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nguyen E, Coleman CI, Nair S, et al. Cost-Utility of empagliflozin in patients with type 2 diabetes at high cardiovascular risk. J Diabetes Complications 2018;32:210–5. 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2017.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kamstra R, Durkin M, Cai J, et al. Economic modelling of costs associated with outcomes reported for type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patients in the canvas and EMPA-REG cardiovascular outcomes trials. J Med Econ 2019;22:280–7. 10.1080/13696998.2018.1562817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjdrc-2020-001313supp001.pdf (479KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Our study data (which is based on de-identified data from a clinical trial) is not in a repository, but is available on reasonable request from the corresponding author (ORCiD 0000-0003-0714-5619).