Abstract

Background

The co-occurrence of slow walking speed and subjective cognitive complaint (SCC) in non-demented individuals defines motoric cognitive risk syndrome (MCR), which is a pre-dementia stage. There is no information on the association between MCR and incident dementia in Québec’s older population.

Objective

The study aims to examine the association of MCR and its individual components (i.e. SCC and slow walking speed) with incident dementia in community-dwelling older adults living in the province of Québec (Canada).

Design

Québec older people population-based observational cohort study with 3 years of follow-up.

Setting

Community dwellings.

Subjects

A subset of participants (n = 1,098) in ‘Nutrition as a determinant of successful aging: The Québec longitudinal study’ (NuAge).

Methods

At baseline, participants with MCR were identified. Incident dementia was measured at annual follow-up visits using the Modified Mini-Mental State (≤79/100) test and Instrumental Activity Daily Living scale (≤6/8) score values.

Results

The prevalence of MCR was 4.2% at baseline and the overall incidence of dementia was 3.6%. MCR (Hazard Ratio (HR) = 5.18, with 95% confidence interval (CI) = [2.43–11.03] and P ≤ 0.001) and SCC alone (HR = 2.54, with 95% CI = [1.33–4.85] and P = 0.005) were associated with incident dementia, but slow walking speed was not (HR = 0.81, with 95%CI = [0.25–2.63] and P = 0.736).

Conclusions

MCR and SCC are associated with incident dementia in NuAge study participants.

Keywords: older people, epidemiology, cohort study, dementia

Key points

Slow walking speed accompanying subjective cognitive complaint defines motoric cognitive risk syndrome (MCR) in the absence of dementia and gait disability.

MCR and subjective cognitive complaint, but not slow walking speed, are significantly associated with incident dementia in the Québec NuAge cohort.

MCR may be of clinical interest for screening individuals at risk for dementia in Québec’s older population.

Introduction

Slow walking speed and subjective cognitive complaint (SCC) are the two clinical characteristics that define motoric cognitive risk syndrome (MCR) in the absence of dementia and gait disability [1]. Although these characteristics may be independently associated with incident dementia, the risk of dementia is higher when they are combined [2]. Walking speed and SCC are easy to assess in daily clinical practice, explaining why MCR is considered an effective assessment to screen for dementia risk [3–5].

MCR is a new syndrome reported in various countries and populations [1,2,5]. However, there is no information on MCR in Quebec’s older population. Using information collected in the ‘Nutrition as a determinant of successful aging: The Québec longitudinal study’ (NuAge) project, we have the opportunity to examine the prevalence of MCR and its association with incident dementia [6]. We hypothesized that MCR could be associated with incident dementia in NuAge participants and that this association would be greater than those of slow walking speed or SCC alone. This study aims to examine the association of MCR and its components (i.e. slow walking speed and SCC) with incident dementia in NuAge participants.

Material and methods

Design

The NuAge study is an older adults’ population-based observational cohort study with 3 years of follow-up.

Population

The NuAge study recruited older (i.e. ≥65) adults without cognitive impairment (i.e. Modified Mini-Mental State (3MS) score > 79/100) who were able to walk one block and climb one storey without rest, and who lived independently in the community [6,7]. For the present study, we excluded participants using a walking aid (n = 66) and those with missing information on walking speed (n = 68), 30-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS; n = 249), 3MS scores and instrumental activity daily living (IADL) score (n = 7) [7–9], as well as those lost to follow-up (n = 227) or who withdrew their agreement to use data (n = 39). This resulted in a subset of 1,098 (62.6%) participants being selected from the original set of 1,754 individuals.

Assessment

Age, sex, medication number and current smoking status (coded yes versus no) were recorded at baseline. The 30-item GDS was used to assess depressive symptomatology, which was considered present in scores > 10/30 [8]. Overweight and/or obesity were considered present if body mass index (BMI) was ≥25 kg/m2. The Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE) was used to determine physical activity level, which was scored from 0 (i.e. lowest performance) to 793 (i.e. highest performance), with a low level defined as scores below the lowest tertile (i.e. <69.1 for females and < 87.7 for males) [10]. Hypertension was considered present when self-reported, noted positive on the Older Americans Resources and Services Multidimensional Functional Assessment (OARS) questionnaire, anti-hypertensive medications were being used, or with a blood pressure measurement > 140/90 mmHg [11]. Diabetes was considered present when it was self-reported, noted positive on the OARS questionnaire, antidiabetic medication was prescribed, or with a fasting glycemia > 6.9 mmol/L. The OARS questionnaire also provides information on various chronic conditions. A total of three dichotomous (that is yes versus no) chronic disease categories were created, assessing cardiovascular disease (including heart, limb and cerebrovascular disease), osteoarticular and muscular disease, and other diseases. Furthermore, walking speed was measured; participants were asked to walk a 4-metre distance at their usual pace twice. Between the second and the fourth metres, time in seconds was recorded with a stopwatch. The best time from the two attempts was used for this study. The follow-up period was three years. Each year, the full standardised assessment performed at baseline (T1) was repeated. The last follow-up (T4) was performed between March 2007 to June 2008.

Definition of motoric cognitive risk syndrome

MCR was defined using information collected at baseline as a combination of SCC and slow walking speed in the absence of dementia and gait disability [1]. SCC was considered when the answer to the item “Do you feel you have more problems with memory than most others?” of 30-item GDS was yes, consistent with previous studies [3]. Slow walking speed was defined as a walking speed at least one standard deviation (SD) below the age-appropriate mean values established in the present cohort. Participants were divided into two sex groups and four age groups, as described by Verghese et al [1].

Definition of dementia

Cognitive performance was evaluated at baseline (T1) and at each annual subsequent visit (T2, T3 and T4) using the 3MS score [7]. From T2 to T4, incident dementia was considered present if the 3MS score was ≤79/100 and the IADL score was ≤6/8) [7,9].

Standard protocol approval and patient consents

The Research Ethics Boards (REB) of the University Institutes of Geriatrics of Sherbrooke and the ‘Institut universitaire de gériatrie de Montréal’ approved the NuAge protocol. Written informed consent for research was obtained for all recruited NuAge participants. The present study was approved by the REB of the Jewish General Hospital (Montreal, Quebec, Canada).

Statistics

Means, SD, and percentages described the participants’ characteristics. Participants were separated on their cognitive status (i.e. dementia versus no dementia). Group comparisons were performed using unpaired t-tests, Mann–Whitney tests or Chi-squared tests. Cox regressions were performed to examine the association of MCR and its components (i.e. slow walking speed and SCC used as independent variables in separate models) with incident dementia (dependent variable) with adjustment for participants’ baseline characteristics, which were significantly different between participants with incident dementia and those without (Table 1). P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistics were performed using SPSS (version 24.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants according to their dementia status (n = 1,098)

| Incident Dementia | P-value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 39) | No (n = 1,059) | ||

| Age (year), mean ± SD | 76.2 ± 4.0 | 73.7 ± 4.1 | ≤0.001 |

| Female, n (%) | 8 (20.5) | 565 (53.4) | ≤0.001 |

| Medication taken daily, n (%) | |||

| Mean ± SD (n) | 4.7 ± 3.1 | 4.5 ± 3.1 | 0.634 |

| Polypharmacy†, n (%) | 19 (48.7) | 474 (44.8) | 0.625 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors, n (%) | |||

| Smoking|| | 21 (53.8) | 493 (46.6) | 0.370 |

| Overweight/Obesity¶ | 30 (76.9) | 756 (71.4) | 0.452 |

| Low level of physical activity§ | 16 (41.0) | 351 (33.1) | 0.306 |

| Hypertension# | 18 (46.2) | 487 (46.0) | 0.984 |

| Diabetes** | 5 (12.8) | 107 (10.1) | 0.582 |

| Cardiovascular diseases††, n (%) | |||

| Heart diseases | 10 (25.6) | 226 (21.3) | 0.521 |

| Limbs vascular diseases | 9 (23.1) | 226 (21.3) | 0.795 |

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 3 (7.7) | 30 (2.8) | 0.081 |

| Osteoarticular & muscular diseases††, n (%) | 20 (51.3) | 643 (60.7) | 0.237 |

| Other diseases††, n (%) | 28 (71.8) | 718 (67.8) | 0.479 |

| 30-item Geriatric Depression Scale | |||

| Mean scale ± SD | 6.0 ± 4.3 | 4.6 ± 4.0 | 0.037 |

| Score > 10, n (%) | 5 (12.8) | 88 (8.3) | 0.320 |

| 3MS score (/100), mean ± SD | 87.8 ± 4.2 | 94.6 ± 3.9 | ≤0.001 |

| Abnormal IADL score||||, n (%) | 30 (76.9) | 288 (27.2) | ≤0.001 |

| MCR criteria, n (%) | |||

| Slow walking speed¶¶ | 3 (7.7) | 115 (10.9) | 0.531 |

| Subjective cognitive complaint§§ | 17 (43.6) | 188 (17.8) | ≤0.001 |

| MCR, n (%) | 9 (23.1) | 37 (3.5) | ≤0.001 |

*Comparison based on unpaired t-test, Mann–Whitney or Chi-square test, as appropriate; †number of therapeutic drugs taken daily ≥5; ||currently smoking, coded as binary answer (yes versus no); ¶considered if BMI was ≥25 kg/m2; §score below the lowest tertile (i.e. <69.1 for female and <87.7 for male); #self-reported, noted positive on the OARS questionnaire, anti-hypertensive medications were being used, or with a blood pressure measurement > 140/90 mmHg; **self-reported, noted positive on the OARS questionnaire, antidiabetic medication was prescribed, or with a fasting glycemia > 6.9 mmol/L; ††based on the OARS questionnaire information, three dichotomous (i.e. yes versus no) categories of diseases were created to indicate the presence of cardiovascular diseases (associating heart, limb and cerebrovascular diseases), osteo-articular and muscular diseases, and other diseases; ||||items scored 1 (independent) and 0 (unable or assistance needed) with a score ranging from 0 (low function) to 8 (high function) and threshold ≤ 6/8; ¶¶cut-off values for defining slow walking speed were: for males, <1.09 m/s for age group 67–72, <1.00 m/s for age group 73–77 m/s, <0.97 m/s for age group 78–84, and < 0.93 m/s for age group ≥ 85; for females, <1.04 m/s for age group 67–72, <0.97 m/s for age group 73–77, <0.91 m/s for age group 78–84 and < 0.81 m/s for age group ≥85; §§answer to the 30-item Geriatric Depression Scale ‘Do you feel you have more problems with memory than most others?’ yes; significant P-values (i.e. <0.05) indicated in bold.

Results

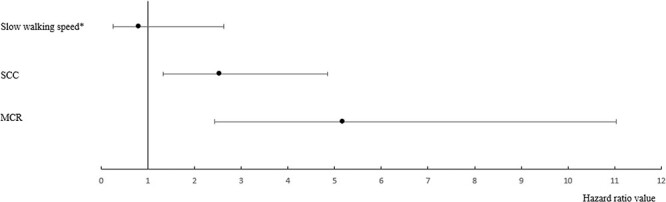

The prevalence of MCR at baseline assessment was 4.2%. The overall incidence of dementia was 3.6%. Individuals with incident dementia were older (P ≤ 0.001), less frequently female (P ≤ 0.001), had higher 30-item GDS scores (P = 0.037), lower 3MS scores (P ≤ 0.001), and were more frequently impaired in their IADL (P ≤ 0.001) when compared to participants without incident dementia (Table 1). There was higher prevalence of SCC (≤0.001) and MCR (≤0.001) among participants with incident dementia compared to those without. Multiple Cox regressions showed that MCR (hazard ratio (HR) = 5.18, with 95% confidence interval (CI) = [2.43–11.03] and P ≤ 0.001) and SCC alone (HR = 2.54, with 95% CI = [1.33–4.85] and P = 0.005) were associated with incident dementia, but slow walking speed alone was not (HR = 0.81, with 95%CI = [0.25–2.63] and P = 0.736) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Cox regressions showing the association of MCR and its components with incident dementia adjusted for participants’ age and sex (n = 1,098). SCC is defined as answering yes to the 30-item GDS item, ‘Do you feel you have more problems with memory than most others?’; *Cut-off values for defining slow walking speed were: for males, <1.09 m/s for age group 67–72, <1.00 m/s for age group 73–77, <0.97 m/s for age group 78–84 and <0.93 m/s for age group ≥ 85; for females, <1.04 m/s for age group 67–72, <0.97 m/s for age group 73–77, <0.91 m/s for age group 78–84 and <0.81 m/s for age group ≥ 85; significant P-values (i.e. <0.05) indicated in bold.

Discussion

MCR and SCC, but not slow walking speed, are significantly associated with incident dementia in the Québec NuAge cohort. Participants with MCR had a 5-fold increased risk of incident dementia compared to those without MCR. This is the highest reported risk in dementia literature [2]. Although SCC was associated with a significantly increased risk of dementia, the magnitude of this risk is halved when compared to MCR’s. This result is consistent with previous studies, which reported that SCC is a predictor of dementia [2,12,13]. Both results highlight the important relationship between cognition and locomotion and the benefit of using MCR to screen for dementia risk [12,13].

Slow walking speed was not associated with incident dementia, whereas it has previously been identified as a predictor of dementia [2,13]. A lack of power, attributable to the healthy condition and low incidence of dementia observed in NuAge participants, may explain this negative result. Nevertheless, mixed results regarding the association between slow walking speed and incident dementia have been reported, with some studies showing no association, as does the present, and others reporting walking speed to be inversely associated with incident dementia [3]. The most recent meta-analysis examining the association between walking speed and incident dementia found that three of the seven identified studies (42.8%) did not report a significant association [3].

NuAge’s large sample size and the 3-year duration of prospective and observational follow-up are both strengths of our study. However, some limitations emerged. First, even if NuAge’s design was appropriate to the objective of our study, examining an association between MCR and incident dementia was not initially planned. Though this was largely inconsequential to the assessment of MCR, there was a consequence for the characterisation of dementia. A dementia diagnosis is usually based on more exhaustive interdisciplinary evaluation that includes a comprehensive neuropsychological assessment and brain imaging. Second, the incidence of dementia in our study was low (3.6%) when compared to previous studies. This low dementia incidence highlights that the NuAge cohort represented a healthy older population. It also suggests that the criteria used to define dementia may have underestimated its incidence. Third, the GDS is not the best method to assess SCC and using an item of 30-item GDS to define SCC may result in an overlap with depressive symptomatology, as 8.5% of participants had a GDS score above 10. Fourth, the selection of 62.6% of the initial NuAge cohort for inclusion in the present study may introduce selection bias and impact outcomes.

In conclusion, MCR is associated with incident dementia in NuAge participants, indicating that MCR may be of clinical interest when screening individuals at risk for dementia in Québec’s older population.

Acknowledgements

The NuAge Study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR; MOP-62842). The NuAge Database and Biobank are supported by the Fonds de recherche du Québec (FRQ; 2020-VICO-279753), the Quebec Network for Research on Aging funded by the FRQ-Santé and by the Merck-Frosst Chair funded by La Fondation de l’Université de Sherbrooke.

Contributor Information

Olivier Beauchet, Department of Medicine, Division of Geriatric Medicine, Sir Mortimer B. Davis Jewish General Hospital and Lady Davis Institute for Medical Research, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada; Dr. Joseph Kaufmann Chair in Geriatric Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada; Centre of Excellence on longevity of McGill integrated University Health Network, Quebec, Canada; Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore.

Harmehr Sekhon, Department of Medicine, Division of Geriatric Medicine, Sir Mortimer B. Davis Jewish General Hospital and Lady Davis Institute for Medical Research, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada; Centre of Excellence on longevity of McGill integrated University Health Network, Quebec, Canada; Faculty of Medicine, Department of Medicine, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Liam Cooper-Brown, Centre of Excellence on longevity of McGill integrated University Health Network, Quebec, Canada.

Cyrille P Launay, Department of Medicine, Division of Geriatric Medicine, Sir Mortimer B. Davis Jewish General Hospital and Lady Davis Institute for Medical Research, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada; Centre of Excellence on longevity of McGill integrated University Health Network, Quebec, Canada.

Pierrette Gaudreau, Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montreal Research Center, Montreal, Quebec, Canada; Department of Medicine, University of Montreal, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

José A Morais, Department of Medicine, Division of Geriatric Medicine, Sir Mortimer B. Davis Jewish General Hospital and Lady Davis Institute for Medical Research, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada; Faculty of Medicine, Department of Medicine, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada; Division of Geriatric Medicine, McGill University Health Centre, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Gilles Allali, Department of Neurology, Geneva University Hospital and University of Geneva, Switzerland.

Declaration of Sources of Funding

None.

Declaration of Conflicts of Interest

None.

References

- 1. Verghese J, Wang C, Lipton RB, Holtzer R. Motoric cognitive risk syndrome and the risk of dementia. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2013; 68: 412–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sekhon H, Allali G, Launay CPet al. Canadian gait consortium. Motoric cognitive risk syndrome, incident cognitive impairment and morphological brain abnormalities: systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas 2019; 123: 45–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Quan M, Xun P, Chen Cet al. Walking pace and the risk of cognitive decline and dementia in elderly populations: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2017; 72: 266–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mendonça MD, Alves L, Bugalho P. From subjective cognitive complaints to dementia: who is at risk?: a systematic review. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2016; 31: 105–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Beauchet O, Sekhon H, Barden Jet al. Canadian gait consortium. Association of Motoric Cognitive Risk Syndrome with cardiovascular disease and risk factors: results from an original study and meta-analysis. J Alzheimers Dis 2018; 64: 875–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gaudreau P, Morais JA, Shatenstein Bet al. Nutrition as a determinant of successful aging: description of the Québec longitudinal study NuAge and results from cross-sectional pilot studies. Rejuvenation Res 2007; 10: 377–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Teng EL, Chui HC. The modified mini-mental state (3MS) examination. J Clin Psychiatry 1987; 48: 314–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TLet al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res 1982-1983; 17: 37–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 1969; 9: 179–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Washburn RA, McAuley E, Katula J, Mihalko SL, Boileau RA. The physical activity scale for the elderly (PASE): evidence for validity. J Clin Epidemiol 1999; 52: 643–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fillenbaum GG. Multidimensional Functional Assessment of Older Adults: The Duke Older Americans Resources and Services Procedures. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Scherder E, Eggermont L, Swaab Det al. Gait in ageing and associated dementias; its relationship with cognition. NeurosciBiobehav Rev 2007; 31: 485–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Beauchet O, Annweiler C, Callisaya MLet al. Poor gait performance and prediction of dementia: results from a meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2016; 17: 482–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]