Abstract

The electrophotocatalytic heterofunctionalization of arenes is described. Using 2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyanoquinone (DDQ) under a mild electrochemical potential with visible light irradiation, arenes undergo oxidant-free hydroxylation, alkoxylation, and amination with high chemoselectivity. In addition to batch reactions, an electrophotocatalytic recirculating flow process is demonstrated, enabling the conversion of benzene to phenol on a gram scale.

Keywords: Electrophotocatalysis, electrochemistry, photochemistry, hydroxylation, alkoxylation, amination

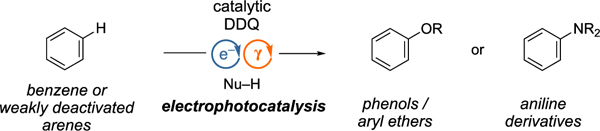

Graphical Abstract

The electrophotocatalytic C-H heterofunctionalization of arenes with high chemoselectivity at both batch and flow conditions is demonstrated.

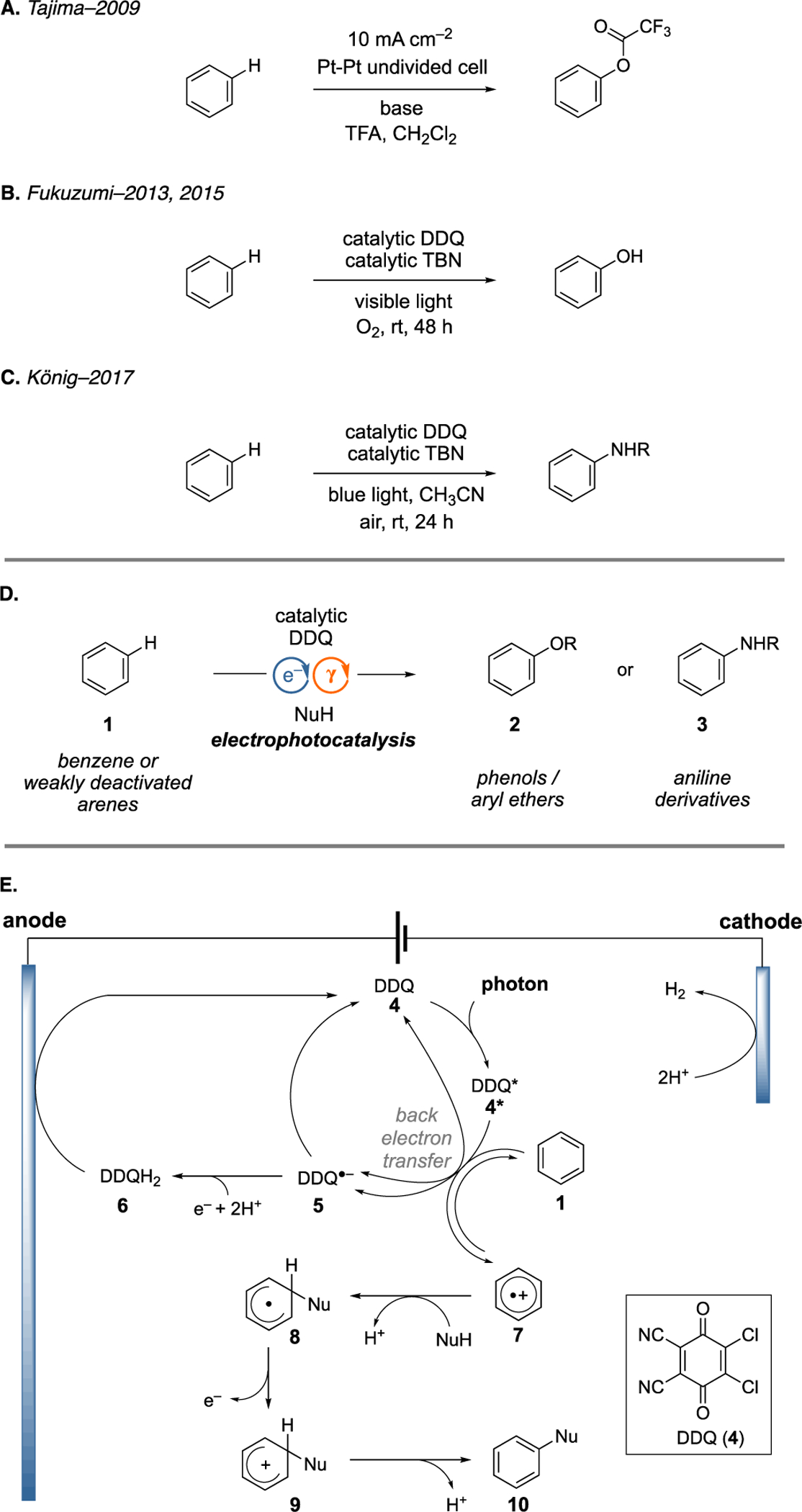

Direct C–H functionalization provides a time-, effort-, and resource-economical approach to synthesize substituted arenes from simple precursors (Figure 1A).[1] While transition metal catalyzed strategies have arguably been the most well-studied approach to accomplish such transformations,[2,3] reactions initiated by single-electron oxidation of the arene have also been explored. The oxygenation of arenes by direct electrolysis has long been known (e.g. Figure 1A), although these approaches tend to suffer from low yield, selectivity, and scope.[4] More recently, visible-light photocatalysis has enabled a number of powerful methods for arene functionalization that do not require the use of metals or metal-directing groups.[5] Because these photoredox reactions are typically initiated by single-electron oxidation of the arene ring, they tend to be performed with relatively electron-rich substrates due to their lower oxidation potentials. In contrast, it has proven more challenging to achieve such reactions with weakly electron-deficient or electron-neutral arenes, for example those bearing halogen atoms or benzene (1) itself, because of their relatively high oxidation potentials. A notable exception was reported by Fukuzumi, who described the visible-light-induced hydroxylation of benzene (1) using DDQ (2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone) (4), which has a sufficiently high excited state redox potential to achieve the single-electron oxidation of benzene (Figure 1B).[6,7] Despite the groundbreaking nature of this discovery, this process was limited to the small-scale hydroxylation of benzene with a relatively high catalyst loading (30–100 mol%). Subsequently, König showed that DDQ photocatalysis could achieve the direct amination of arenes using nucleophiles such as carbamates and ureas, greatly expanding the utility of this chemistry (Figure 1C).8 However, the relatively high catalyst loading and the use of tert-butyl nitrite and air, which forms a potentially explosive mixture, were not ideal. We hypothesized that adaptation to an electrophotocatalytic strategy might address some of the issues noted above and thus enable a range of useful arene C–H functionalizations.

Figure 1.

A. Example of oxygenation of benzene by direct electrolysis. B. DDQ photocatalyzed hydroxylation of benzene. C. DDQ photocatalyzed amination of benzene D. Electrophotocatalytic arene heterofunctionalization. E. Mechanistic rationale.

We recently demonstrated the use of DDQ as an electrophotocatalyst[9–11] for SNAr reactions with non-traditional substrates under mild conditions.[10b] Given that success, and the Fukuzumi and König precedents, we speculated that this electrophotocatalytic approach might be adapted to realize an efficient arene heterofunctionalization strategy (Figure 1D). We anticipated that the process would operate by a mechanism akin to the previous reports, wherein photoexcited DDQ effects single electron transfer (SET) oxidization of an arene 1 to furnish a radical cation 7 that can undergo nucleophilic capture. The key difference is that DDQ (4) would be regenerated by anodic oxidation of the reduced DDQH2 (6), with concomitant cathodic reduction of protons to form hydrogen gas completing the electrochemical reaction. Thus, this electrophotocatalytic setup obviates the need for a traditional oxidant like TBN. In this Communication, we demonstrate the electrophotocatalytic heterofunctionalization of arenes, including hydroxylation, alkoxylation, and amination reactions, both in batch and in a recirculating flow process.

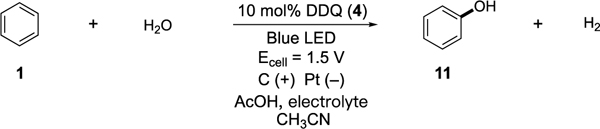

We first examined the electrophotocatalytic coupling of benzene (1) and water to form phenol (11) (Table 1). Our initial condition choice was based on our previous study[10b] and entailed subjecting benzene, 20 equivalents of water, and 10 mol% DDQ (4) to a 1.5 V controlled potential in an undivided cell (carbon cathode, Pt anode) under visible light irradiation (blue LED strip) in the presence of TBABF4 and acetic acid. Under these conditions, phenol (11) was generated in 43% yield (entry 1). Changing the electrolyte to LiClO4 resulted in an appreciably higher yield (55%, entry 2), while lower catalyst loading resulted in diminished yield (36% yield, entry 3). The catalyst, potential, and light were necessary for this reaction (entries 4–6) which confirmed the process was actually electrophotocatalytic. The product yield was significantly diminished without the addition of acetic acid (entry 7). With further screening, we found that a higher yield (80%) could be realized by using more equivalents of water (50 equiv.) and a longer reaction time of 48 h (entry 8). Importantly, when we attempted the same reaction by direct electrolysis without catalyst and light using up to 3.0 V constant voltage, no phenol was observed (entry 9). Using the optimized conditions but longer reaction time (96 h), the reaction could be scaled up (entry 10).

Table 1.

Optimization studies.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Time (h) | Electrolyte (equiv) | Other | Yield (%)[a,b] |

| 1 | 28 | TBABF4 (1) | – | 43 |

| 2 | 28 | LiClO4 (6) | – | 55 |

| 3 | 28 | LiClO4 (6) | 5% DDQ | 36 |

| 4 | 28 | LiClO4 (6) | no catalyst | 0 |

| 5 | 28 | LiClO4 (6) | no light | 0 |

| 6 | 28 | LiClO4 (6) | no electrolysis | <5 |

| 7 | 28 | LiClO4 (6) | no acid | 8 |

| 8 | 48 | LiClO4 (6) | 50 equiv. H2O | 80 |

| 9 | 48 | LiClO4 (6) | direct electrolysis[a] | 0 |

| 10 | 96 | LiClO4 (6) | 4 mmol scale | 66 (52)[c] |

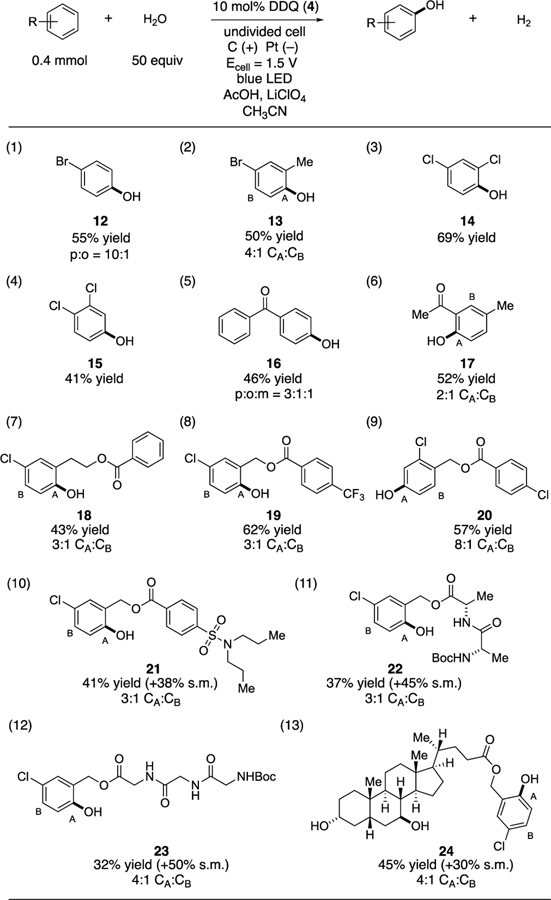

Using the optimized conditions, the generality of the hydroxylation reaction was explored (Table 2). Bromoarene products 12 and 13 were obtained in 55% and 50% yields with 10:1 to 4:1 regioselectivity respectively (entries 1–2). Meanwhile, both 1,3- and 1,2-dichlorobenzene underwent hydroxylation with complete regioselectivity (entries 3 and 4). Benzophenone and 3-methylacetophenone also reacted, furnishing phenol 16 in 46% yield and 17 in 52% yield respectively (entries 5 and 6). Despite the fact that these electron-deficient arenes were reactive to the hydroxylation procedure, substrates with two electronically differentiated arenes were exclusively functionalized on the more electron-rich ring (entries 7–10). Although these conditions are obviously strongly oxidizing conditions, potentially sensitive functionality in the form of Boc-protected peptides (entries 11 and 12) or free hydroxyl groups (entry 13) were tolerated, allowing for the production of phenols 22-24.

Table 2.

Electrophotocatalytic hydroxylation of arenes with water.

|

See SI for detailed procedures.

Isolated yields.

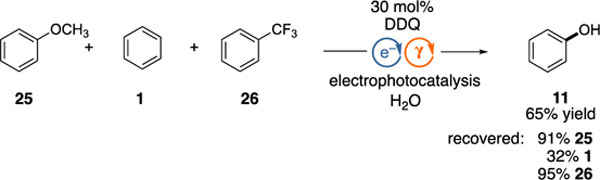

To further demonstrate the selectivity of this protocol, we subjected a mixture of anisole (25), benzene (1), and trifluorotoluene (26) to the electrophotocatalytic hydroxylation procedure (equation 1). In this case, phenol (11) was generated exclusively while the other two arenes were left untouched by these conditions. Intermediate 4* is insufficiently oxidizing to remove an electron from arenes with very high oxidation potentials, while alkoxybenzenes or phenols also do not undergo reaction, likely due to a rapid back-electron transfer process that outcompetes nucleophilic attack to the transient radical cation intermediate.[6]

|

(1) |

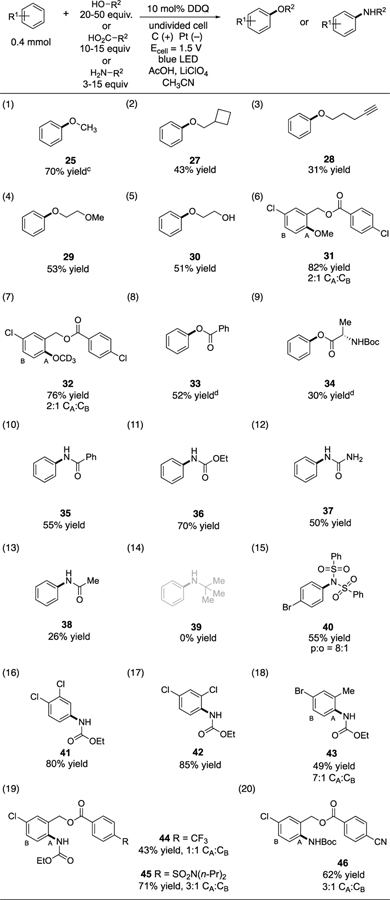

In addition to the use of water to generate phenols, we found that other nucleophiles could also be utilized (Table 3). For example, the reaction of benzene with various alcohols led to the formation of aryl ether products 25, 27-30 (entries 1–5). Methoxylation to generate 31 was readily achieved (entry 6), and the deuterated analogue 32 could also be accessed (entry 7). Alternatively, benzoic acid (entry 8) or N-Boc alanine (entry 9) furnished aryl esters 33 and 34. In terms of nitrogen nucleophiles, benzamide (entry 10), ethyl carbamate (entry 11), urea (entry 12), and acetamide (entry 13) reacted with benzene in varying yields. Amines were not productive (e.g. entry 14), likely due to the acidic conditions. On the other hand, diphenylsulfonimide readily participated (entry 15). Using ethylcarbamate, a variety of halogenated arenes could be derivatized (entries 16–19). Meanwhile, tert-butylcarbamate was also productive to furnish adduct 46 in 62% yield (entry 20).

Table 3.

|

See SI for detailed procedures.

Isolated yields.

Yields were determined by UPLC.

Without AcOH.

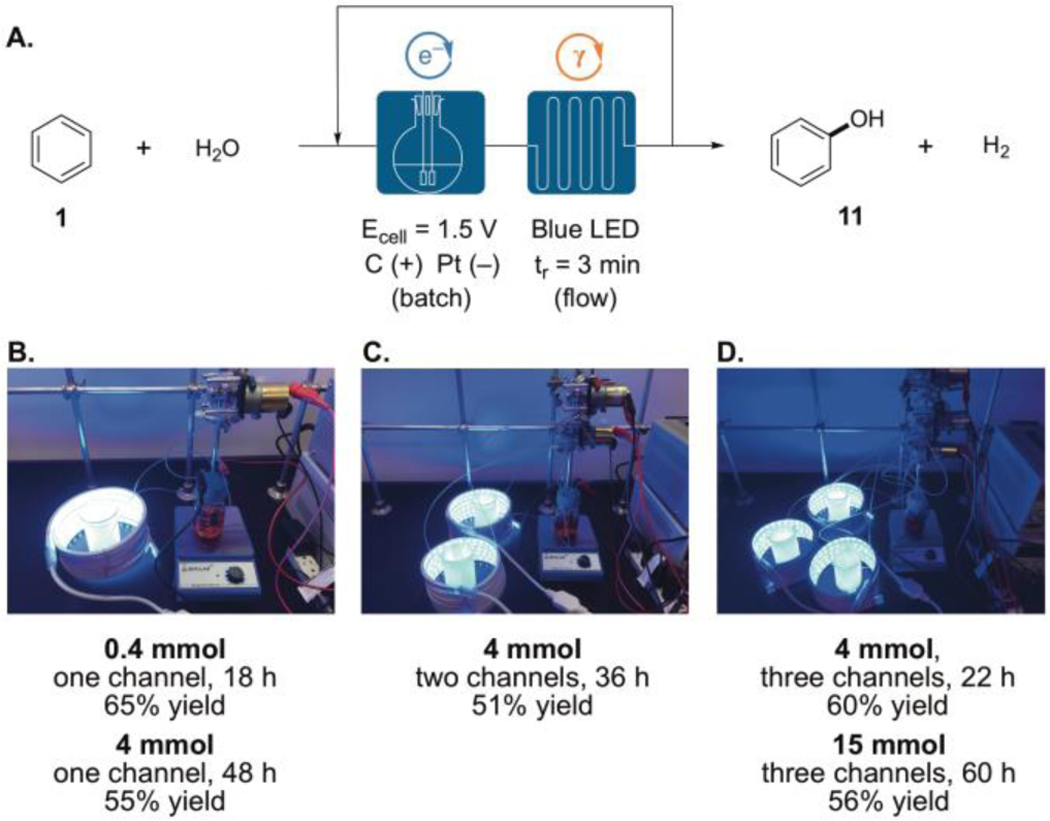

To enable further scale up of this process, we adapted this method to a continuous flow system.[12] Although continuous flow has proven to be highly advantageous for photoredox catalysis, it has only just recently been adapted for electrophotocatalysis.[9j,k,m] Because in the current reactions the photochemical portion of the process is much slower than the electrochemical one, we were able to couple a small electrochemical cell with one or more photochemical chambers using an inexpensive peristaltic pump. Using the hydroxylation of benzene as a representative reaction, we employed a flow set-up (Figure 2) with a residence time of 3 min and a 1.5 V controlled potential undivided cell, with which phenol (11) was formed in 65% yield on a 0.4 mmol scale in 18 h (Figure 2B). For a larger scale (4 mmol), a longer reaction time was needed; however, by equipping two photoreactor channels the reaction time could be reduced with minimal impact on yield (Figure 2C). Equipping three flow channels further decreased the reaction time to 22 h and improved the yield (Figure 2D). Notably, using the three channel set-up, a 15 mmol scale reaction delivered a 56% yield of phenol (11) in 60 h.

Figure 2.

(A) Electrophotocatalytic hydroxylation of benzene in flow using (B) one, (C) two, or (D) three photo reactor channels.

In conclusion, we have developed an electrophotocatalytic procedure for the C–H hydroxylation, alkoxylation, and amination of arenes with high chemoselectivity.[13] Using DDQ as an electrophotocatalyst, water, alcohols, acids, amides or carbamates can be appended to arenes without the use of external oxidants. This work thus adds a new set of tools to the arsenal of direct C–H functionalization protocols.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Financial support for this work was provided by NIGMS (R35 GM127135).

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document.

References

- [1].a) Yu J-Q, Shi Z, C-H Activation; Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2010. [Google Scholar]; b) Davies HML, Morton D, J. Org. Chem 2016, 81, 343–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].a) Hartwig J, Organotransition Metal Chemistry: From Bonding to Catalysis; University Science Books, Sausalito, CA, 2010. [Google Scholar]; For selected recent reviews: b) Gandeepan P, Ackermann L, Chem 2018, 4, 199–222. [Google Scholar]; c) Rej S, Ano Y, Chatani N, Chem. Rev 2020, 120, 1788–1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].a) Examples of direct arene heterofunctionalization: Niwa S.-i., Eswaramoorthy M, Nair J, Raj A, Itoh N, Shoji H, Namba T, Mizukami F Science 2002, 295, 105–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Morimoto Y, Bunno S, Fujieda N, Sugimoto H, Itoh S J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 5867–5870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Han JW, Jung J, Lee Y-M, Nam W, Fukuzumi S Chem. Sci 2017, 8, 7119–7125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) For a review on catalytic phenol production: Schmidt RJ Appl. Catal. A-Gen 2005, 280, 89–103. [Google Scholar]

- [4].a) For selected examples of electrochemical arene heterofunctionalization: Tajima T, Kishi Y, Nakajima A Electrochim. Acta 2009, 54, 5959–5963. [Google Scholar]; b) Eberson L, Oberrauch E Acta Chem. Scand. B 1981, 35, 193–196. [Google Scholar]; c) So Y-H, Becker JY, Miller LL J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Comm 1975, 262–263. [Google Scholar]; d) Eberson L, Nyberg K, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1966, 88, 1686–1691. [Google Scholar]

- [5].a) For selected reviews: Fukuzumi S, Ohkubo K, Org. Biomol. Chem 2014, 12, 6059–6071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Romero NA, Nicewicz DA, Chem. Rev 2016, 116, 10075–10166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Crespi S, Fagnoni M, Chem. Rev 2020, 120, 9790–9833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) For selected examples: Hari DP, Schroll P, König B, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 2958–2961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Beatty JW, Douglas JJ, Cole KP, Stephenson CRJ, Nat. Commun 2015, 6, 7919–7925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Romero NA, Margrey KA, Tay NE, Nicewicz DA, Science 2015, 349, 1326–1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Margrey KA, McManus JB, Bonazzi S, Zecri F, Nicewicz DA, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 11288–11299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].a) Ohkubo K, Fujimoto A, Fukuzumi S, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 5368–5371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ohkubo K, Hirose K, Fukuzumi S, Chem. - Eur. J 2015, 21, 2855–2861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].A related photocatalytic arene hydroxylation / amination reaction that requires UV light has also been reported. Zheng Y-W, Chen B, Ye P, Feng K, Wang W, Meng Q-Y, Wu L-Z, Tung C-H J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 10080–10083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].a) Das S, Natarajan P, König B Chem. Eur. J 2017, 23, 18161–18165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) For a recent review, see: Natarajan P, König B Eur. J. Org. Chem 2021, DOI: 10.1002/ejoc.202100011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [9].a) For examples of electrophotocatalysis or photoelectrocatalysis, see: Moutet J-C, Reverdy G, J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun 1982, 654–655. [Google Scholar]; b) Scheffold R, Orlinski R, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1983, 105, 7200–7202. [Google Scholar]; c) Tateno H, Iguchi S, Miseki Y, Sayama K, Angew. Chem 2018, 130, 11408–11411; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2018, 57, 11238–11241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Yan H, Hou Z-W, Xu H-C, Angew. Chem 2019, 131, 4640–4643; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2019, 58, 4592–4595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Wang F, Stahl SS, Angew. Chem 2019, 131, 6451–6456; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2019, 58, 6385–6390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Zhang L, Liardet L, Luo J, Ren D, Grätzel M, Hu X, Nat. Catal 2019, 2, 366–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Zhang W, Carpenter K, Lin S, Angew. Chem 2020, 132, 417–425; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2020, 59, 409–417. [Google Scholar]; h) Cowper NGW, Chernowsky CP, Williams OP, Wickens ZK, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 2093–2099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Lai X, Shu X, Song J, Xu H-C, Angew. Chem 2020, 132, 10713–10719; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2020, 59, 10626–10632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j) Qiu Y, Scheremetjew A, Finger LH, Ackermann L, Chem. - Eur. J 2020, 26, 3241–3246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k) Xu P, Chen P, Xu H-C, Angew. Chem 2020, 132, 14381–14386; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2020, 59, 14275–14280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; l) Niu L, Jiang C, Liang Y, Liu D, Bu F, Shi R, Chen H, Chowdhury AD, Lei A, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 17693–17702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (m) Yan H, Song J, Zhu S, Xu H-C CCS Chemistry 2021, 3, 317–325. [Google Scholar]; (n) Wu S, Žurauskas J, Domanski M, Hitzfield PS, Butera V, Scott DJ, Rehbein J, Kumar A, Thyrhaug E, Hauer J, Barham JP, Org. Chem. Front 2021, DOI: 10.1039/d0qo01609h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [10].a) For examples of electrophotocatalysis from our group, see: Huang H, Strater ZM, Rauch M, Shee J, Sisto TJ, Nuckolls C, Lambert TH, Angew. Chem 2019, 131, 13452–13456; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2019, 58, 13318–13322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Huang H, Lambert TH, Angew. Chem 2020, 132, 668–672; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2020, 59, 658–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Huang H, Strater ZM, Lambert TH, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 1698–1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Kim H, Kim H, Lambert TH, Lin S, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 2087–2092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Shen T, Lambert TH, Science 2021, 371, 620–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].a) For selected reviews and highlights, see: Capaldo L, Quadri LL, Ravelli D, Angew. Chem 2019, 131, 17670–17672; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2019, 58, 17508–17510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Barham JP, König B, Angew. Chem 2020, 132, 11828–11844; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2020, 59, 11732–11747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Liu J, Lu L, Wood D, Lin S, ACS Cent. Sci 2020, 6, 1317–1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Yu Y, Guo P, Zhong J-S, Yuan Y, Ye K-Y, Org. Chem. Front 2020, 7, 131–135. [Google Scholar]; e) Meyer TH, Choi I, Tian C, Ackermann L, Chem 2020, 6, 2484–2496. [Google Scholar]

- [12].a) Cambié D, Bottecchia C, Straathof NJW, Hessel V, Noël T, Chem. Rev 2016, 116, 10276–10341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Elsherbini M, Wirth T, Acc. Chem. Res 2019, 52, 3287–3296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].During the review of this manuscript, a preprint describing a closely related method appeared: Hou Z-W, Yan H, Song J, Xu H-C, 2021, DOI 10.26434/chemrxiv.13718392.v1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.