Abstract

Positron emission tomography (PET) / computed tomography (CT) are nuclear diagnostic imaging modalities that are routinely deployed for cancer staging and monitoring. They hold the advantage of detecting disease related biochemical and physiologic abnormalities in advance of anatomical changes, thus widely used for staging of disease progression, identification of the treatment gross tumor volume, monitoring of disease, as well as prediction of outcomes and personalization of treatment regimens. Among the arsenal of different functional imaging modalities, nuclear imaging has benefited from early adoption of quantitative image analysis starting from simple standard uptake value (SUV) normalization to more advanced extraction of complex imaging uptake patterns; thanks to application of sophisticated image processing and machine learning algorithms. In this review, we discuss the application of image processing and machine/deep learning techniques to PET/CT imaging with special focus on the oncological radiotherapy domain as a case study and draw examples from our work and others to highlight current status and future potentials.

Keywords: Quantitative PET/CT, cancer, response evaluation, machine learning, deep learning, treatment outcomes, prediction

Introduction

Recent years have witnessed exponential growth in the use of imaging for diagnostic and therapeutic radiological purposes. In particular, positron emission tomography (PET) has been widely used in oncology for the purposes of diagnosis, grading, staging, and assessment of response. For instance, PET imaging with 18F-FDG (fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose), a glucose metabolism analog, has been applied for diagnosis, staging, and treatment planning of lung cancer (1-10), head and neck cancer (11, 12), prostate cancer (13), cervical cancer (14, 15), colorectal cancer (16), lymphoma (17, 18), melanoma (19) and breast cancer (20-22). Moreover, accumulating evidence supports that pre-treatment or post-treatment FDG-PET uptake could be used as a prognostic factor for predicting outcomes (23-27). The combination with computed tomography (CT) further augment the functional/physiological information with anatomical information to better localize disease. A detailed review of recent advances in PET/CT imaging for oncology is presented in our previous work (28).

Quantitative imaging information from hybrid-imaging modalities could be related to biological and clinical endpoints, a new emerging field referred to as “radiomics” (29, 30). We and others have published work to demonstrate the potential of this new field to monitor and predict response to radiotherapy in head and neck (31, 32), cervix (31, 33), sarcoma (34), and lung (35) cancers, allowing for adapting and individualizing treatment regimens. More recently, with the development of deep neural networks (DNNs) as well as the enhanced graphics processing unit (GPU) computing power, deep learning-based image analyses showed promising results in several applications, including segmentation, reconstruction, and outcome modeling, etc. These algorithms allow learning the image representation directly from the raw images in opposite to conventional machine learning approaches that would require manual extraction of these features (36). For instance, Sharif et al. presented an artificial neural networks (ANN) in the wavelet domain for PET volume segmentation (37). Zhao et al. proposed a multi-modality segmentation method based on a 3D fully convolutional neural network (F-CNN), which is capable of taking into account both PET and CT information simultaneously for tumor segmentation (38). Ypsilantis et al. showed that one CNN based PET imaging representation are highly predictive of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy (39).

In this review, we will discuss the application of advanced machine/deep learning techniques based on PET/CT imaging for response evaluation with specific focus on two major areas of obtaining regions of interest (e.g., cancerous tumors) and image-based prediction of treatment outcomes.

Quantitative image analysis from PET/CT

Hand-crafted radiomics methods, with hundreds or even more radiomics features available, requires feature selection and/or feature extraction as a necessary prior step that aims to obtain the optimal subset or combination of features to achieve better performance and also to reduce the risk of overfitting. Filter, wrapper and embedded methods are commonly used supervised methods for feature selection. Principal component analysis (PCA) (40), clustering and t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) (41) are some examples of unsupervised methods, where no labels are needed. Based on the endpoints, either time dependent (survival) or independent (classification) machine learning algorithms could be applied for the feature selection (42). Typical classification algorithms include logistic regression, support vector machines (SVM), random forests (RF), and neural networks (43-45). Cox regression (46), random survival forests (47) and support vector survival (48) methods, as well as recently proposed deep learning based survival models (49, 50) are available for survival analysis.

Though hand-crafted features introduced above can provide prior knowledge, they also suffer from the tedious designing process and may not faithfully capture the underlying imaging information for the task at hand with potential selection bias. Alternatively, with the development of deep learning technologies, as a branch of machine learning, the extraction of machine learnt features is becoming widely applicable recently. These deep learning methods are generally based on multi-layer neural networks, especially the convolutional neural networks (CNN). In deep learning, the processes of data representation and prediction (e.g., classification or regression) are performed jointly. In such a case, multi-stack neural layers of varying modules (e.g., convolution for filtering or pooling for data reduction) with linear/non-linear activation (mapping) functions perform the task of learning the representations of data with multiple levels of abstraction and subsequent fully connected layers are tasked with classification/regression, for instance (36).

A typical scenario to get such features is to use the data representation CNN layers as feature extractor. Each hidden layer module within the network transforms the representation at one level. For example, the first level may represent edges in an image oriented in a particular direction, the second may detect motifs in the observed edges, the third could recognize objects from ensembles of motifs (51). Patch-/pixel-based machine learning methods use pixel/voxel values in images directly instead of features calculated from segmented objects as in other approaches (52). This removes the need for segmentation, one of the major sources of inter- and intra-variability of radiomic features. Moreover, the data representation removes the feature selection portion eliminating associated statistical bias in this process as noted earlier.

For the CNN network, either self-designed (from scratch) or existing pre-trained structures with natural or medical images (e.g., VGG (53), Resnet (54), two CNN network structure that performed well for ImageNet classification task) can be used. Depending on the data size, we can choose to fix the parameters or fine tune the network using our data, also called transfer learning. Instead of using deep networks as feature extractors, we can use them directly for the whole modeling process. Similar to the conventional machine learning methods, there are also supervised, unsupervised and semi-supervised methods. CNN are similar to regular neural networks, but the architecture is modified to fit to the specific input of large-scale images.

Inspired by the Hubel and Wiesel’s work on the animal visual cortex (55), local filters are used to slide over the input space in CNNs, which not only exploit the strong local correlation in natural images, but also reduce the number of weights significantly by sharing weights for each filter. Recurrent neural networks (RNN) can use their internal memory to process time-dependent sequence inputs (e.g., dynamic PET acquisition) and take the previous output as inputs. There are two popular types of RNN – Long short-term memory (LSTM) and Gated recurrent units (GRU) (56, 57). They were invented to solve the problem of vanishing gradients for long sequences by internal gates that are able to learn which data in the sequence is important to keep or discard.

Deep autoencoders (AE), which are unsupervised learning algorithms (no labels are needed for the input data), have been applied to medical imaging for latent representative feature extraction. There are variations to the AEs, such as variational autoencoders that resemble the original AE and variational Bayesian methods to learn a probability distribution that represents the data (58), convolutional autoencoders that preserve spatial locality (59), etc. Another unsupervised method is the restricted Boltzmann machine (RBM), which consists of visible and hidden layers (60). The forward pass learns the probability of activations given the inputs, while the backward pass tries to estimate the probability of inputs given activations. Thus, the RBMs lead to the joint probability distribution of inputs and activations.

Deep belief networks can be regarded as a stack of RBMs, where each RBM communicates with previous and subsequent layers. RBMs are quite similar with AEs, however, instead of using deterministic units, like RELU, RBMs use stochastic units with certain distribution. As mentioned above, labeled data is limited, especially in the medical field. Neural network based semi-supervised approaches that combine unsupervised and supervised learning by training the supervised network with an additional loss component from the unsupervised generative models (e.g. AEs, RBMs) (61). More details on the machine learning aspect is provided here (62, 63).

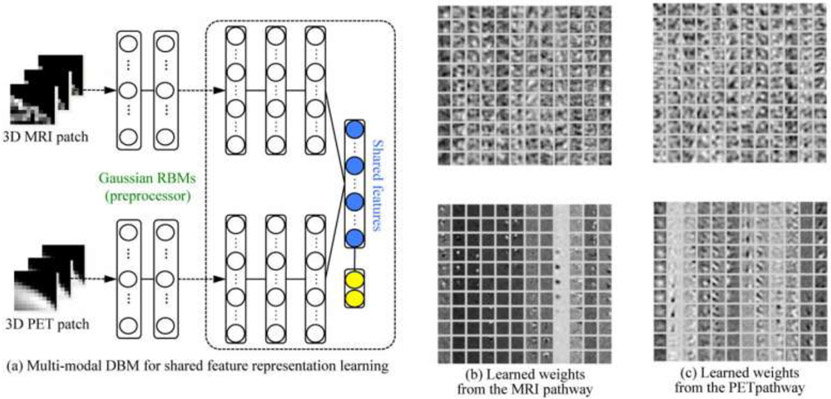

Comparing with feature-based methods, deep learning methods are more flexible and can be used with some modifications in various tasks. In addition to classification, segmentation, registration, and lesion detection are widely explored by deep learning techniques. Fully CNN (FCN), trained end-to-end, merge features learnt from different stages in the encoders and then upsampling low resolution feature maps by deconvolutions (64). Unet, built upon FCNN, with the pooling layers being replaced by upsampling layers, resulting in a nearly symmetric U-shaped network (65). Skipping structures combines the context information with the unsampled feature maps to achieve higher resolution. In order to identify Alzheimer’s disease or mild cognitive impairment, Shen et al. exploited deep Boltzmann machine (DBM) to obtain a latent hierarchical feature representation from a 3D patch, and then devised a systematic method for a joint feature representation, as shown in Figure 1 (a), from the paired patches of MRI and PET with a multi-modal DBM by fusing neuroimaging and biological features. Figure 1 (b) and Figure 1 (c) visualize, respectively, the learned connection weights from the MRI pathway and the PET pathway (66).

Figure 1.

(a) The shared feature learning from patches of the heterogeneous modalities, e.g., MRI and PET, with discriminative multi-modal DBM and (b, c) visualization of the learned weights in Gaussian RBMs (bottom) and those of the first hidden layer (top) from MRI and PET pathways in multi-modal DBM (From Shen et al., 2017).

Once the model is built using the algorithms introduced above, the final step is the model evaluation. Ideally, the model should be tested on a large independent patient cohort. Alternatively, resampling methods were developed to evaluate the model performance in the situation of limited sample sizes. Two commonly applied methods are bootstrapping and cross-validation. The basic idea of bootstrapping is to make inference about a population using the sample data by resampling with replacement methods. It was first introduced by Bradley Efron in 1979 (67), and the more commonly used bias-corrected and accelerated (BCa) bootstrap was developed by Efron as well (68). Cross-validation is used to measure (evaluate) the goodness of fit for a prediction model. Models will be developed on the training folds and tested on the validation fold. Typically used frames are 5-fold or 10-fold cross-validation. Cross-validation is commonly used for model hyper-parameter tuning as well. In terms of the metrics that measure the goodness of fit, the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, or the area under the ROC curve (AUC) quantifies the sensitivity and specificity of the model and represents the probability that a randomly selected case is correctly distinguished with a larger probability than a randomly selected case is incorrectly distinguished for the classification task, and c-index is similar to AUC and is used as a measure for survival models, which is the probability of concordance between predicted and observed survival. The instruction of using these techniques can be found in the TRIPOD guidelines (69).

One thing to point out is that the training data used for feature selection and model construction should not be used for the evaluation of the model, which will lead to overoptimistic results and worse generalization for new data. Careful design of training, validation, and test sets within any resampling technique is vital for reducing the selection or optimization bias (70-72), where a balance between fitting and generalization can be achieved. The size of the training data is an intractable problem that depends on the dataset, the complexity of the problem and the learning algorithm. Ideally, more data is desired to train complex models (e.g., deep learning models) and estimate the generalizability of the developed models. However, in reality, especially in the medical field, data scarcity is a challenge hard to be resolved. To deal with this issue, synthetic data methods were applied, such as generative adversarial networks, or simply using slices or patches of images. Theoretically, power analysis is used to estimate the sample size needed to detect an effect. The definition of power is the probability of rejecting the null hypothesis when it is true.

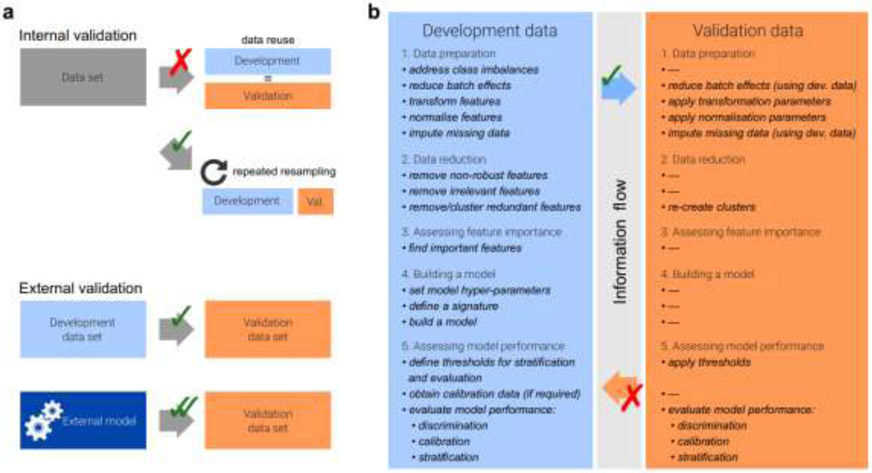

In a review by Zwanenburg, the radiomics workflow as shown in Figure 2 was summarized. Meanwhile several pitfalls during radiomics analysis was pointed out as well, such as the split of training, validation and testing data, class imbalance and incomplete reporting, which should be payed attention to when conducting radiomics study (73).

Figure 2.

a. Data analysis strategies and typical analysis workflow. Generalizability of a radiomics model is assessed through internal and external validation (a). Internal validation should be reported by repeatedly dividing the data into development and validation datasets instead of reusing the development data for validation to avoid optimistic biases. (b). Many steps are only fully performed on the development dataset, and the resulting parameters and results are applied to the validation dataset.

Application of PET/CT based AI models

In the following, we discuss application of PET/CT to radiotherapy, as a case study for oncological applications, with focus on two cases: PET/CT regions of interest delineation/detection and outcome prediction for response evaluation and clinical decision-making using deep learning for PET/CT.

PET/CT deep learning based tumor delineation detection

PET/CT imaging can simultaneously acquire functional metabolic information and anatomical information of the human body. To fuse the complementary information in PET/CT for accurate tumor segmentation is challenging. Some multimodality tumor segmentation methods have been proposed. EI Naqa et al. proposed a multivalued level set model based method to integrate information from multimodality images to identify the biophysical structure (74). Markel et al. used 3D texture features to train a combined decision tree with K-nearest neighbor classifier for segmentation in PET/CT (75). There are works for PET/CT segmentation based on Markov Random Field optimization, graph cut method as well as a ‘topo-poly’ graph model with the intention to combine the information from multimodality images (76-78).

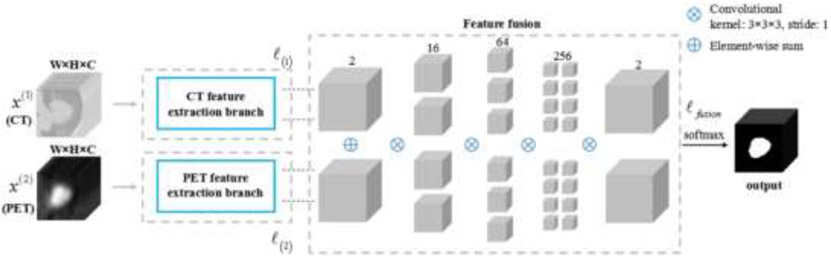

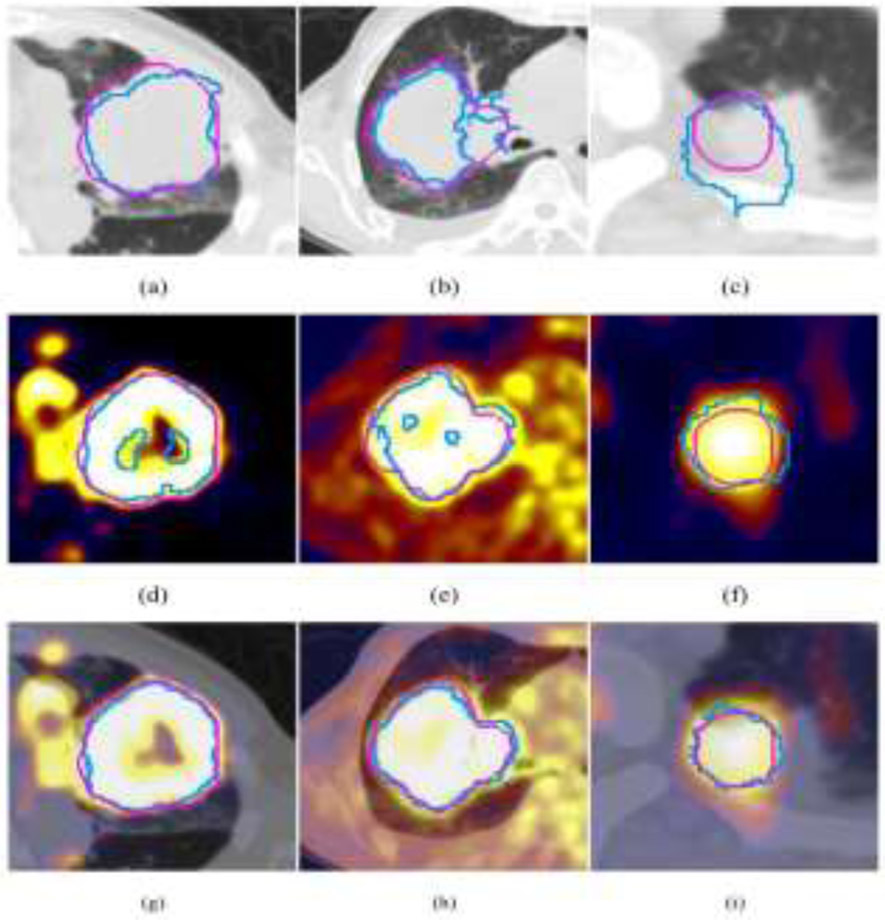

Recently, deep learning based region of interest (ROI) segmentation/abnormality detection methods showed improved performance for different disease sites. Li et al. proposed to use a 3D FCNN to produce a probability map from the CT image in non-small cell lung cancer dataset (79). A fuzzy variational model was then proposed to incorporate the probability map and the PET intensity image for an accurate multimodality tumor segmentation, where the probability map acted as a membership degree prior. They found that only a few samples were needed for training the network to produce the probability map, which is beneficial in clinic research where the dataset is small. The results showed an average dice similarity indexes (DSI) of 0.86 ± 0.05, sensitivity (SE) of 0.86 ± 0.07, positive predictive value (PPV) of 0.87 ± 0.10, volume error (VE) of 0.16 ± 0.12, and classification error (CE) of 0.30 ± 0.12. Moe et al. described an automatic segmentation algorithm using the U-Net architecture for delineation of the gross tumor volume and pathologic lymph nodes of head and neck cancers in PET/CT images (80). Zhao et al. proposed a network started with a multi-task training module, in which two parallel sub-segmentation architectures constructed using deep CNNs were designed to automatically extract feature maps from PET and CT respectively for lung cancer dataset (81). A feature fusion module was subsequently designed based on cascaded convolutional blocks, which re-extracted features from PET/CT feature maps using a weighted cross-entropy minimization strategy. The tumor mask was obtained as the output at the end of the network using a softmax function. Figure 3 shows the network structure and Figure 4 shows the example tumor segmentation results for CT only, PET only and PET/CT conditions.

Figure 3.

The architecture of the proposed co-segmentation network. Two parallel branches were used for feature extraction from the CT image and the PET image, respectively, followed by the feature fusion module. The segmentation result was the output at the end of the network.

Figure 4.

Visual comparison of the segmentation results (blue contour) of different methods and the ground truth (pink contour) for three patients. (a)–(c) Segmentation results of the CNN-based method using CT only, and (d)–(f) segmentation results of using PET only, and (g)–(i) segmentation results of the proposed co-segmentation method.

Gsaxner et al. proposed a method to generate a training dataset from PET/CT by applying thresholding to the PET data for obtaining a ground truth and by utilizing data augmentation to enlarge the dataset for the urinary bladder segmentation (82). Ben-Cohen et al. combined a fully convolutional network (FCN) with a conditional generative adversarial network (GAN) to generate simulated PET data from given input CT data (83). The synthesized PET can be used for false-positive reduction in lesion detection solutions. Clinically, such solutions may enable lesion detection and drug treatment evaluation in a CT-only environment, thus reducing the need for the more expensive and radioactive PET/CT scan. Quantitative evaluation was conducted using an existing lesion detection software, combining the synthesized PET as a false positive reduction layer for the detection of malignant lesions in the liver. Current results showed a 28% reduction in the average false positive per case from 2.9 to 2.1.

A multimodal spatial attention module (MSAM) that automatically learns to emphasize regions (spatial areas) related to tumors and suppress normal regions with physiologic high-uptake was introduced by Fu et al. (84). The resulting spatial attention maps are subsequently employed to target a convolutional neural network (CNN) for segmentation of areas with higher tumor likelihood. Two clinical PET-CT datasets of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and soft tissue sarcoma (STS) validated the effectiveness of the MSAM in these different cancer types. This MSAM method surpassed the state-of-the-art lung tumor segmentation approach by a margin of 7.6% in Dice similarity coefficient (DSC).

PET/CT deep learning based modeling

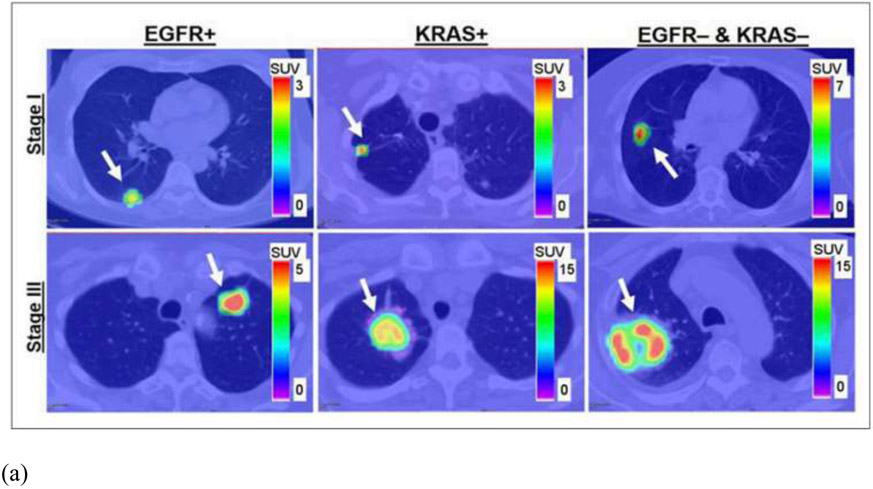

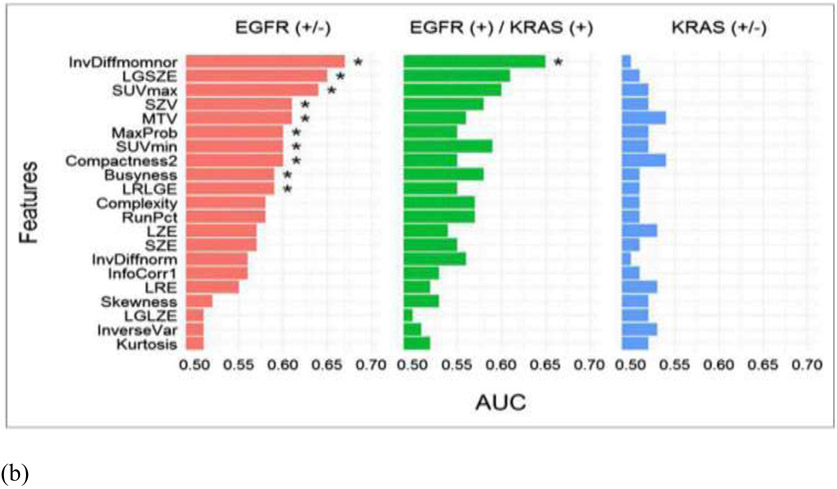

In conventional radiomics, El Naqa et al. investigated intensity-volume histogram metrics and shape and texture features extracted from PET images to predict patient's response to treatment for cervix and head and neck cancers and showed good preliminary discriminant power for utilizing functional imaging in clinical prognosis (85). Cook et al. conducted research on patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated with chemoradiotherapy underwent pretreatment 18F-FDG PET/CT scans and found that baseline 18F-FDG PET scan uptake showing abnormal texture as measured by coarseness, contrast, and busyness is associated with nonresponse to chemoradiotherapy by RECIST and with poorer prognosis (86). Yip et al. assessed the association of and predictive power of FDG PET-based radiomic features for somatic mutation in NSCLC patients (87). They found that found that eight radiomic features and two conventional features were significantly associated with EGFR mutation status (FDR Wilcoxon = 0.01–0.10). Figure 5 showed the PET images for different mutation groups and the predictive power for each feature. Hsu et al. introduced a FDG-PET radiomics tissue classifier for differentiating FDG avid-normal tissues from tumor (88). This work showed that the radiomics features from PET images are able to correctly capture the characteristics of normal tissues and tumor. Figure 6 showed one of the decision tree, the threshold for the random forests and the t-SNE visualization for better understanding of the role of different features.

Figure 5.

(a) From left to right are patients with EGFR mutation, KRAS mutation, and EGFR– and KRAS– tumors. Stage I and III tumors are shown in top and bottom rows, respectively. Arrows indicate locations of lung tumors; (b) AUC. * indicates that AUC is significantly > 0.50 (random guessing) assessed with Noether test (FDRNoether <= 0.10). Many of the features significantly predict EGFR+ tumors; however, they are not able to predict KRAS+ tumors.

Figure 6.

Visualization of random forest classifier. (a) Binary decision tree for classifying FDG-avid tissues and tumor. Fifty binary decision trees were trained with the random forest classifier. (TR: Tumor, KL: kidney left, BL: bladder, KR: kidney right, HT: heart, BR: brain). (b) Display of threshold values for volume and maximum SUV in all 50 trees. The color coding (red: bladder, green: brain, blue: heart, purple: kidney left, gold: kidney right, teal: tumor, white: undecided) shows the tissue classification made on two features: volume and centroid Z. (c) t-SNE plot illustrating the classification results for all segmented volumes and features using dimension reduction.

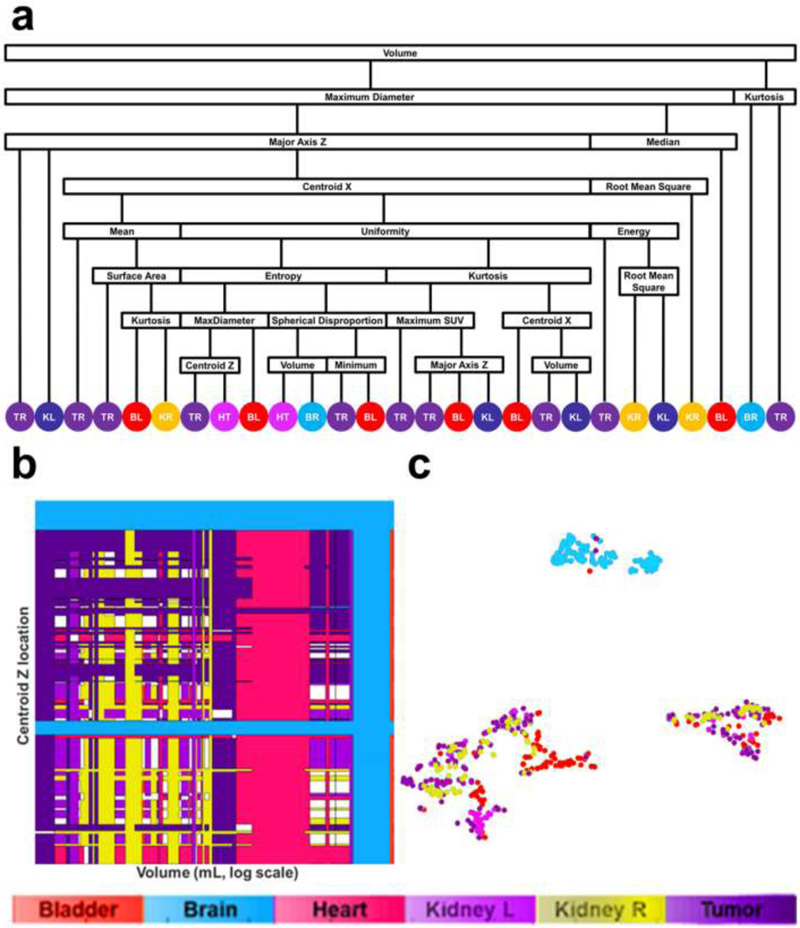

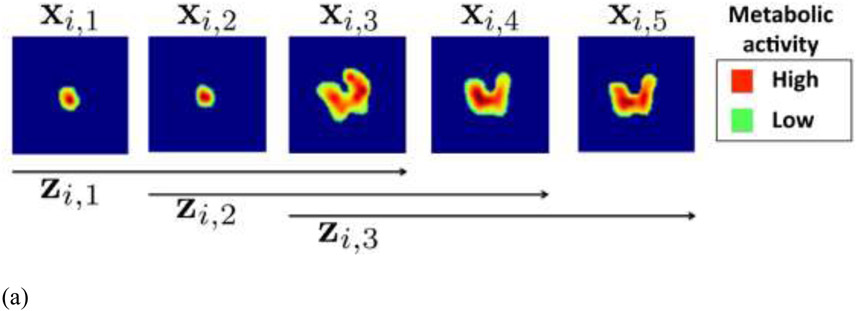

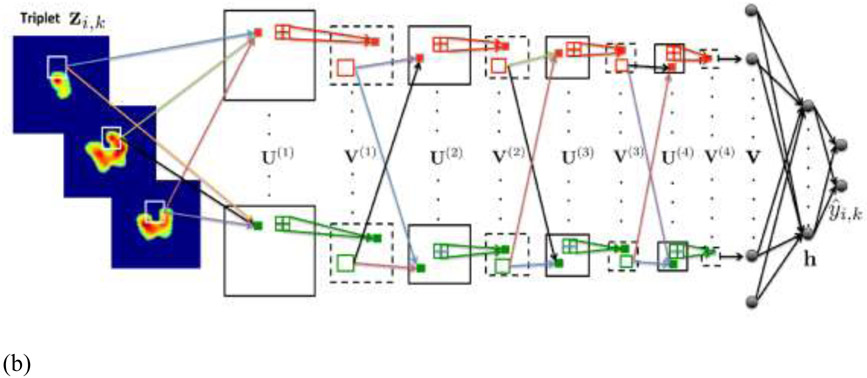

Though hand-crafted features are able to embed experts’ prior knowledge, it suffered from tedious feature selection process and might miss other important information in the images. Deep learning method developed on large dataset that uses the whole image as input avoid this issue and provides a promising option for response evaluation in PET/CT. Ypsilantis et al. compared the performance of the two competing strategies: an approach using state-of-the-art statistical classifiers based on radiomics features; and a CNN trained directly from the PET scans. For radiomics feature-based approach, 103 radiomics features including texture and model-based features were extracted and four statistical classifiers (logistic regression, gradient boosting, RFs and SVMs) were adopted for the discrimination of responders/non-responders for 107 patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. For the deep learning approach, in order to capture patterns of FDG uptake across multiple adjacent slices that might be important for predicting chemotherapy response, all possible sets of three adjacent slices were constructed as input to a three-channel CNN network (3S-CNN). The input and network structures were shown in Figure 7. They showed that the CNN based PET imaging representation are highly predictive of response to therapy and outperformed the feature-based approach (39). Kawauchi et al. conducted a retrospective study included 6462 patients who underwent whole body FDG PET-CT. The CNN network was able to predict the sex, as well as age and body weight to prevent patient misidentification in clinical settings (89). The same group conducted a retrospective study on 3485 sequential patients with malignant disease, who underwent whole-body FDG PET/CT (90). A residual network (ResNet)-based CNN architecture was built for classifying patients into the 3 categories (benign, malignant or equivocal). In addition, they performed a region-based analysis of CNN (head-and-neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvic region). In the patient-based analysis, CNN predicted benign, malignant and equivocal images with 99.4, 99.4, and 87.5% accuracy, respectively. Schwyzer et al. studied the performance of artificial neural network discriminating lung cancer patients based on clinical standard dose, tenfold and thirtyfold reduced radiation dose FDG-PET images. They found that machine learning algorithms may aid fully automated lung cancer detection even at very low dose (91).

Figure 7.

(a)18F-FDG PET ROIs of a specific tumor i after segmentation embedded into larger square background of standard size of 100 × 100 pixels. Each enlarged slice is denoted by xi,j and each set of three spatially adjacent enlarged slides is denoted by xi,k, where j and k represent the slices and triplets of the specific tumor i. In this example only 3 triplets, from the 5 available slices can be formed, so k = 1,2,3; (b) CNN architecture for fusion of 3 adjacent 18F-FDG PET intra slices into a vector v. The CNN architecture is composed from 4 convolutional and 4 max-pooling layers denoted by and (From Ypsilantis et al., 2015).

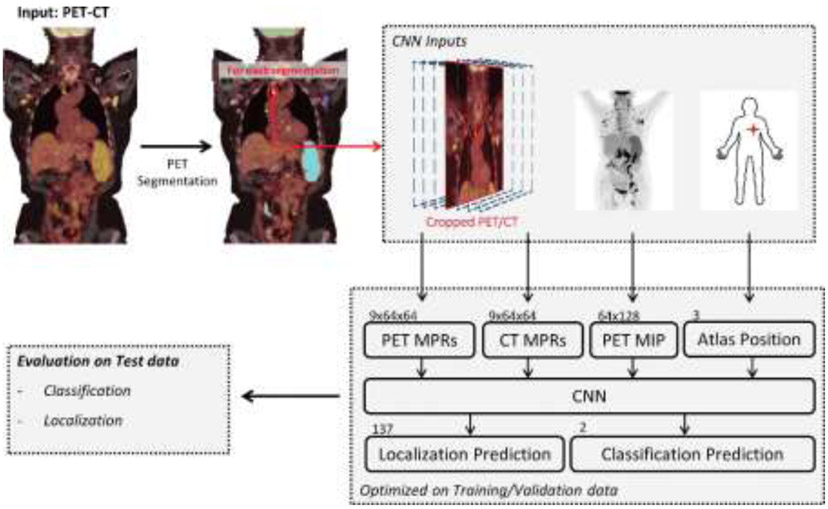

Sibille et al. proposed a CNN to detect foci positive for 18F-FDG uptake, predict the anatomic location, and determine the expert classification (suspicious or non-suspicious) in patients with lung cancer and lymphoma (92) . This study included 629 patients. Fig. 8 shows the network structure where there are PET/CT crop inputs, PET–maximum intensity projection (MIP) and atlas position input. The output contains both classification and location predictions.

Figure 8.

Convolutional neural network (CNN) for automated detection of foci positive for fluorine 18 (18F)–fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake, definition of their anatomic localization, and classification of lesions suspicious for tumor. The position of an 18F-FDG–positive focus, transformed in the atlas space and a PET–maximum intensity projection (MIP) and nine coronal multiplanar reconstructions (MPRs), are extracted from PET and CT and are used by the CNN to predict the localization and classification.

PET volumes of interest were first segmented by using a fixed thresholding algorithm to create candidate regions. Whole-body CT examinations were aligned to an anatomic atlas location; the displacement found was used to translate the manually defined 18F-FDG–positive foci to a standardized position, referred to as atlas position. Nine coronal multiplanar reconstructions were extracted to consider anatomic surroundings of an 18F-FDG–positive focus. A coronal maximum intensity projection (MIP) of the whole-body 18F-FDG PET was reconstructed. They found that both 18F-FDG PET and CT information are needed to obtain the highest accuracy.

Wang et al. compared one deep learning method and four classical machine learning methods (RFs, SVMs, adaptive boosting, and ANN) for classifying mediastinal lymph node metastasis of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) from 18F-FDG PET/CT images (93). The five methods were evaluated using 1397 lymph nodes collected from PET/CT images of 168 patients, with corresponding pathology analysis results as gold standard. It showed that the performance of CNN is not significantly different from the best classical methods and human doctors for classifying mediastinal lymph node metastasis of NSCLC from PET/CT images. However, CNN does not need tumor segmentation or feature calculation, it is more convenient and more objective than the classical methods. Peng et al. constructed radiomics signatures and a nomogram for predicting disease-free survival (DFS) based on the features from PET and CT images for individual induction chemotherapy (IC) in advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) (94). Both deep learning features and handcrafted features were extracted from the lung tumor and lymph nodes (4 ROIs) based on the PET/CT images to quantify the tumor phenotype. For each ROI, a deep CNN was trained to extract deep learning features. A set of handcrafted features was also extracted. The radiomics nomogram achieved a c-index of 0.722 (95% CI, 0.652–0.792) in the test set. Deep learning PET/CT-based radiomics could serve as a reliable and powerful tool for prognosis prediction and may act as a potential indicator for individual IC in advanced NPC.

Current issues and future directions

PET image characteristics

Generally speaking, PET images have lower resolution than CT or MRI in the order of 3-5 mm, which is further worsened under cardiac or respiratory motion conditions due to longer acquisition periods. Moreover, PET images are susceptible to limited photon count noise. Advances in hardware such as crystal detector technologies (95) and software such as image reconstruction techniques (96) are poised to improve PET images quality and their subsequent use. Deep learning reconstruction methods are also promising to obtain better spatial resolution PET images as discussed in previous sections, which cost much less to realize compared with the hardware development approach.

Improved PET-based outcome models

The conventional feature-based machine learning methods embedded experts’ prior knowledge, while the feature selection process is usually blamed to be unstable, especially for high-dimensional feature input. In comparison, deep learning methods are able to bypass the feature designing or selection stages, and have shown great potential in clinical image applications, including segmentation, reconstruction, classification, actuary analysis. However, there are several issues restraining its clinical practice, two major ones are the scarcity of data and the difficulty in interpretability. For limit sample size, data augmentation (e.g., affine transformation of the images) during training is commonly adopted. Transfer learning is also a widely used strategy to reduce the difficulty in training, by transferring deep models trained on other datasets (natural images) and then fine-tuning on the target dataset. The structures of the networks can be modified to reduce overfitting as well, such as, adding dropout and batch normalization layers. Dropout randomly deactivates a fraction of the units during training and can be viewed as a regularization technique that adds noise to the hidden units (97). Batch normalization reduces the internal covariate shift by normalizing for each training minibatch (98).

For the interpretability, the large number of interacting, non-linear parts makes it hard to understand deep neural networks (99, 100). Aiming at improving the interpretability of radiomics for clinicians, graph-based approaches can be utilized (101), and better visualization tools for deep learning are being developed such as activation maps highlighting regions of the tumor that impact the prediction of the deep learning classifier are also being proposed. Several groups have developed methods for identifying and visualizing the features in individual test data points that contribute most towards a classifier’s output. A well-known method is the Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations (LIME), which provides explanations of decisions for any machine learning model by local approximation with simpler methods (102). Selvaraju et al. proposed a method called Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM), which uses the gradients of any target concept (say logits for ‘dog’ or even a caption), flowing into the final convolutional layer to produce a coarse localization map highlighting the important regions in the image for predicting the concept at hand (103). Chattopadhyay et al. further generalized this method into Grad-CAM++ that can explain occurrences of multiple object instances in a single image compared to state-of-the-art (104).

Conclusions

Image processing constitutes an indispensable set of tools for analyzing and extracting valuable information from PET/CT images, this is made more powerful with the emergence of artificial intelligence techniques that is reshaping the future of radiological sciences including nuclear medicine (105). We presented in this review an overview of different traditional features that could be extracted from PET/CT images and various modern machine/deep learning methods that could use these images as direct input for different applications including contouring and response prediction. We have shown that incorporation of different anatomical information from CT into PET is feasible and could yield better results. However, there are challenges still in the use of PET with some issues related to inherited image quality, others related to standardization of image acquisition protocols and reconstruction algorithms, and also some general issues like shortage of data and inadequate interpretability of the models for deep learning approaches that appeared not only in PET/CT applications but across the spectrum of medical imaging applications. Nevertheless, advances in hardware and software technologies will further facilitate wider application of advanced image processing and machine learning techniques to PET/CT and hybrid imaging to achieve better clinical results and personalized treatment regimens. In particular, the synergy between image analysis and machine learning could provide powerful tools to strengthen and further the utilization of PET/CT in clinical practice and realize its potentials for a better personalized health care and improved patient’s quality of life.

Acknowledgements

This work was partly supported by grants from National Institute of Health (NIH) grants and R37-CA222215 and R01-CA233487.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Verhagen AF, Bootsma GP, Tjan-Heijnen VC, van der Wilt GJ, Cox AL, Brouwer MH, et al. FDG-PET in staging lung cancer: how does it change the algorithm? Lung Cancer. 2004;44(2):175–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradley J, Thorstad WL, Mutic S, Miller TR, Dehdashti F, Siegel BA, et al. Impact of FDG-PET on radiation therapy volume delineation in non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;59(1):78–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradley JD, Perez CA, Dehdashti F, Siegel BA. Implementing biologic target volumes in radiation treatment planning for non-small cell lung cancer. J Nucl Med. 2004;45 Suppl 1:96S–101S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradley J, editor Applications for FDG-PET in Lung Cancer; Staging, Targeting, and Follow-up. The Radiological Society of North America; 2004. Nov. 28-Dec. 3; Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Erdi YE, Macapinlac H, Rosenzweig KE, Humm JL, Larson SM, Erdi AK, et al. Use of PET to monitor the response of lung cancer to radiation treatment. Eur J Nucl Med. 2000;27(7):861–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mac Manus MP, Hicks RJ. PET scanning in lung cancer: current status and future directions. Semin Surg Oncol. 2003;21(3):149–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mac Manus MP, Hicks RJ, Matthews JP, McKenzie A, Rischin D, Salminen EK, et al. Positron emission tomography is superior to computed tomography scanning for response-assessment after radical radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(7):1285–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacManus MR, Hicks R, Fisher R, Rischin D, Michael M, Wirth A, et al. FDG-PET-detected extracranial metastasis in patients with non-small cell lung cancer undergoing staging for surgery or radical radiotherapy--survival correlates with metastatic disease burden. Acta Oncol. 2003;42(1):48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pandit N, Gonen M, Krug L, Larson SM. Prognostic value of [18F]FDG-PET imaging in small cell lung cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2003;30(1):78–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toloza EM, Harpole L, McCrory DC. Noninvasive staging of non-small cell lung cancer: a review of the current evidence. Chest. 2003;123(1 Suppl):137S–46S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwartz DL, Ford E, Rajendran J, Yueh B, Coltrera MD, Virgin J, et al. FDG-PET/CT imaging for preradiotherapy staging of head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;61(1):129–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suarez Fernandez JP, Maldonado Suarez A, Dominguez Grande ML, Santos Ortega M, Rodriguez Villalba S, Garcia Camanaque L, et al. [Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging in head and neck cancer]. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp. 2004;55(7):303–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oyama N, Miller TR, Dehdashti F, Siegel BA, Fischer KC, Michalski JM, et al. 11C-acetate PET imaging of prostate cancer: detection of recurrent disease at PSA relapse. J Nucl Med. 2003;44(4):549–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mutic S, Malyapa RS, Grigsby PW, Dehdashti F, Miller TR, Zoberi I, et al. PET-guided IMRT for cervical carcinoma with positive para-aortic lymph nodes-a dose-escalation treatment planning study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;55(1):28–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller TR, Grigsby PW. Measurement of tumor volume by PET to evaluate prognosis in patients with advanced cervical cancer treated by radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;53(2):353–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ciernik IF. [Radiotherapy of rectal cancer]. Schweiz Rundsch Med Prax. 2004;93(36):1441–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Castellucci P, Zinzani P, Nanni C, Farsad M, Moretti A, Alinari L, et al. 18F-FDG PET early after radiotherapy in lymphoma patients. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2004;19(5):606–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spaepen K, Stroobants S, Verhoef G, Mortelmans L. Positron emission tomography with [(18)F]FDG for therapy response monitoring in lymphoma patients. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2003;30 Suppl 1:S97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fogarty GB, Tartaglia CJ, Peters LJ. Primary melanoma of the oesophagus well palliated by radiotherapy. Br J Radiol. 2004;77(924):1050–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Biersack HJ, Bender H, Palmedo H. FDG-PET in monitoring therapy of breast cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2004;31 Suppl 1:S112–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lind P, Igerc I, Beyer T, Reinprecht P, Hausegger K. Advantages and limitations of FDG PET in the follow-up of breast cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2004;31 Suppl 1:S125–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zangheri B, Messa C, Picchio M, Gianolli L, Landoni C, Fazio F. PET/CT and breast cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2004;31 Suppl 1:S135–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brun E, Kjellen E, Tennvall J, Ohlsson T, Sandell A, Perfekt R, et al. FDG PET studies during treatment: prediction of therapy outcome in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2002;24(2):127–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hope AJ, Saha P, Grigsby PW. FDG-PET in carcinoma of the uterine cervix with endometrial extension. Cancer. 2006;106(1):196–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kalff V, Duong C, Drummond EG, Matthews JP, Hicks RJ. Findings on 18F-FDG PET scans after neoadjuvant chemoradiation provides prognostic stratification in patients with locally advanced rectal carcinoma subsequently treated by radical surgery. J Nucl Med. 2006;47(1):14–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hicks RJ, Mac Manus MP, Matthews JP, Hogg A, Binns D, Rischin D, et al. Early FDG-PET imaging after radical radiotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer: Inflammatory changes in normal tissues correlate with tumor response and do not confound therapeutic response evaluation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;60(2):412–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grigsby PW, Siegel BA, Dehdashti F, Rader J, Zoberi I. Posttherapy [18F] fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in carcinoma of the cervix: response and outcome. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(11):2167–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zaidi H, Alavi A, El Naqa I. Novel Quantitative PET Techniques for Clinical Decision Support in Oncology. Seminars in nuclear medicine. 2018;48(6):548–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lambin P, Rios-Velazquez E, Leijenaar R, Carvalho S, van Stiphout RG, Granton P, et al. Radiomics: extracting more information from medical images using advanced feature analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(4):441–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar V, Gu Y, Basu S, Berglund A, Eschrich SA, Schabath MB, et al. Radiomics: the process and the challenges. Magn Reson Imaging. 2012;30(9):1234–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.El Naqa I, Grigsby P, Apte A, Kidd E, Donnelly E, Khullar D, et al. Exploring feature-based approaches in PET images for predicting cancer treatment outcomes. Pattern Recognit. 2009;42(6):1162–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vallieres M, Kay-Rivest E, Perrin LJ, Liem X, Furstoss C, Aerts H, et al. Radiomics strategies for risk assessment of tumour failure in head-and-neck cancer. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):10117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kidd EA, El Naqa I, Siegel BA, Dehdashti F, Grigsby PW. FDG-PET-based prognostic nomograms for locally advanced cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;127(1):136–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vallieres M, Freeman CR, Skamene SR, El Naqa I. A radiomics model from joint FDG-PET and MRI texture features for the prediction of lung metastases in soft-tissue sarcomas of the extremities. Phys Med Biol. 2015;60(14):5471–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vaidya M, Creach KM, Frye J, Dehdashti F, Bradley JD, El Naqa I. Combined PET/CT image characteristics for radiotherapy tumor response in lung cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2012;102(2):239–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wei L, Osman S, Hatt M, El Naqa I. Machine learning for radiomics-based multimodality and multiparametric modeling. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2019;63(4):323–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sharif MS, Abbod M, Amira A, Zaidi H. Artificial neural network-based system for PET volume segmentation. Journal of Biomedical Imaging. 2010;2010:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao X, Li L, Lu W, Tan S. Tumor co-segmentation in PET/CT using multimodality fully convolutional neural network. Phys Med Biol. 2018;64(1):015011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ypsilantis P-P, Siddique M, Sohn H-M, Davies A, Cook G, Goh V, et al. Predicting response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy with PET imaging using convolutional neural networks. PloS one. 2015;10(9):e0137036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wold S, Esbensen K, Geladi P. Principal component analysis. Chemometrics and intelligent laboratory systems. 1987;2(1-3):37–52. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lvd Maaten, Hinton G. Visualizing data using t-SNE. Journal of Machine Learning Research. 2008;9(Nov):2579–605. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parmar C, Grossmann P, Bussink J, Lambin P, Aerts HJ. Machine learning methods for quantitative radiomic biomarkers. Sci Rep. 2015;5:13087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vallières M, Kay-Rivest E, Perrin LJ, Liem X, Furstoss C, Aerts HJ, et al. Radiomics strategies for risk assessment of tumour failure in head-and-neck cancer. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):10117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu S, Zheng J, Li Y, Wu Z, Shi S, Huang M, et al. Development and validation of an MRI-based radiomics signature for the preoperative prediction of lymph node metastasis in bladder cancer. EBioMedicine. 2018;34:76–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang Y, Oikonomou A, Wong A, Haider MA, Khalvati F. Radiomics-based prognosis analysis for non-small cell lung cancer. Sci Rep. 2017;7:46349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cox DR. Regression models and life - tables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological). 1972;34(2):187–202. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ishwaran H, Kogalur UB, Blackstone EH, Lauer MS. Random survival forests. The annals of applied statistics. 2008;2(3):841–60. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Belle V, Pelckmans K, Van Huffel S, Suykens JA. Support vector methods for survival analysis: a comparison between ranking and regression approaches. Artif Intell Med. 2011;53(2):107–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Katzman JL, Shaham U, Cloninger A, Bates J, Jiang T, Kluger Y. DeepSurv: personalized treatment recommender system using a Cox proportional hazards deep neural network. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ching T, Zhu X, Garmire LX. Cox-nnet: An artificial neural network method for prognosis prediction of high-throughput omics data. PLoS Comput Biol. 2018;14(4):e1006076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.LeCun Y, Bengio Y, Hinton G. Deep learning. nature. 2015;521(7553):436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Suzuki K Pixel-based machine learning in medical imaging. Journal of Biomedical Imaging. 2012;2012:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Simonyan K, Zisserman A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:14091556. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 54.He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J, editors. Deep residual learning for image recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hubel DH, Wiesel TN. Receptive fields and functional architecture of monkey striate cortex. The Journal of physiology. 1968;195(1):215–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hochreiter S, Schmidhuber J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997;9(8):1735–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cho K, Van Merriënboer B, Gulcehre C, Bahdanau D, Bougares F, Schwenk H, et al. Learning phrase representations using RNN encoder-decoder for statistical machine translation. arXiv preprint arXiv:14061078. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kingma DP, Welling M. Auto-encoding variational bayes. arXiv preprint arXiv:13126114. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li F, Qiao H, Zhang B. Discriminatively boosted image clustering with fully convolutional auto-encoders. Pattern Recognition. 2018;83:161–73. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hinton GE, Salakhutdinov RR. Reducing the dimensionality of data with neural networks. Science. 2006;313(5786):504–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kingma DP, Mohamed S, Rezende DJ, Welling M, editors. Semi-supervised learning with deep generative models. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 62.El Naqa I, Li R, Murphy MJ, editors. Machine Learning in Radiation Oncology: Theory and Application. 1 ed. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Goodfellow I, Bengio Y, Courville A. Deep learning. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2017. pages cm. p. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Long J, Shelhamer E, Darrell T, editors. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation. Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition; 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ronneberger O, Fischer P, Brox T, editors. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. International Conference on Medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention; 2015: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shen D, Wu G, Suk H-I. Deep learning in medical image analysis. Annual review of biomedical engineering. 2017;19:221–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Efron B Bootstrap methods: another look at the jackknife. Breakthroughs in statistics: Springer; 1992. p. 569–93. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Efron B Better bootstrap confidence intervals. Journal of the American statistical Association. 1987;82(397):171–85. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Moons KG, Altman DG, Reitsma JB, Ioannidis JP, Macaskill P, Steyerberg EW, et al. Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD): explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(1):W1–W73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hastie T, Tibshirani R, Friedman J, Franklin J. The elements of statistical learning: data mining, inference and prediction. The Mathematical Intelligencer. 2005;27(2):83–5. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ambroise C, McLachlan GJ. Selection bias in gene extraction on the basis of microarray gene-expression data. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(10):6562–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Singhi SK, Liu H, editors. Feature subset selection bias for classification learning. Proceedings of the 23rd international conference on Machine learning; 2006: ACM. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zwanenburg A Radiomics in nuclear medicine: robustness, reproducibility, standardization, and how to avoid data analysis traps and replication crisis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2018:1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.El Naqa I, Yang D, Apte A, Khullar D, Mutic S, Zheng J, et al. Concurrent multimodality image segmentation by active contours for radiotherapy treatment planning a. 2007;34(12):4738–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Markel D, Caldwell C, Alasti H, Soliman H, Ung Y, Lee J, et al. Automatic segmentation of lung carcinoma using 3D texture features in 18-FDG PET/CT. 2013;2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ju W, Xiang D, Zhang B, Wang L, Kopriva I, Chen XJIToIP. Random walk and graph cut for co-segmentation of lung tumor on PET-CT images. 2015;24(12):5854–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cui H, Wang X, Zhou J, Eberl S, Yin Y, Feng D, et al. Topology polymorphism graph for lung tumor segmentation in PET-CT images. 2015;60(12):4893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Han D, Bayouth J, Song Q, Taurani A, Sonka M, Buatti J, et al. , editors. Globally optimal tumor segmentation in PET-CT images: a graph-based co-segmentation method. Biennial International Conference on Information Processing in Medical Imaging; 2011: Springer. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Li L, Zhao X, Lu W, Tan SJN. Deep learning for variational multimodality tumor segmentation in PET/CT. 2020;392:277–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Moe YM, Groendahl AR, Mulstad M, Tomic O, Indahl U, Dale E, et al. Deep learning for automatic tumour segmentation in PET/CT images of patients with head and neck cancers. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhao X, Li L, Lu W, Tan SJPiM, Biology. Tumor co-segmentation in PET/CT using multimodality fully convolutional neural network. 2018;64(1):015011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gsaxner C, Roth PM, Wallner J, Egger JJPo. Exploit fully automatic low-level segmented PET data for training high-level deep learning algorithms for the corresponding CT data. 2019;14(3):e0212550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ben-Cohen A, Klang E, Raskin SP, Soffer S, Ben-Haim S, Konen E, et al. Crossmodality synthesis from CT to PET using FCN and GAN networks for improved automated lesion detection. 2019;78:186–94. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fu X, Bi L, Kumar A, Fulham M, Kim JJapa. Multimodal Spatial Attention Module for Targeting Multimodal PET-CT Lung Tumor Segmentation. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.El Naqa I, Grigsby PW, Apte A, Kidd E, Donnelly E, Khullar D, et al. Exploring feature-based approaches in PET images for predicting cancer treatment outcomes. Pattern recognition. 2009;42(6):1162–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cook GJ, Yip C, Siddique M, Goh V, Chicklore S, Roy A, et al. Are pretreatment 18F-FDG PET tumor textural features in non-small cell lung cancer associated with response and survival after chemoradiotherapy? J Nucl Med. 2013;54(1):19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yip SS, Kim J, Coroller TP, Parmar C, Velazquez ER, Huynh E, et al. Associations between somatic mutations and metabolic imaging phenotypes in non small cell lung cancer. J Nucl Med. 2017;58(4):569–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hsu C-Y, Doubrovin M, Hua C-H, Mohammed O, Shulkin BL, Kaste S, et al. Radiomics features differentiate between normal and tumoral high-Fdg uptake. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):3913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kawauchi K, Hirata K, Katoh C, Ichikawa S, Manabe O, Kobayashi K, et al. A convolutional neural network-based system to prevent patient misidentification in FDG-PET examinations. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):7192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kawauchi K, Furuya S, Hirata K, Katoh C, Manabe O, Kobayashi K, et al. A convolutional neural network-based system to classify patients using FDG PET/CT examinations. 2020;20(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Schwyzer M, Ferraro DA, Muehlematter UJ, Curioni-Fontecedro A, Huellner MW, von Schulthess GK, et al. Automated detection of lung cancer at ultralow dose PET/CT by deep neural networks-Initial results. Lung Cancer. 2018;126:170–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sibille L, Seifert R, Avramovic N, Vehren T, Spottiswoode B, Zuehlsdorff S, et al. 18F-FDG PET/CT uptake classification in lymphoma and lung cancer by using deep convolutional neural networks. 2020;294(2):445–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wang H, Zhou Z, Li Y, Chen Z, Lu P, Wang W, et al. Comparison of machine learning methods for classifying mediastinal lymph node metastasis of non-small cell lung cancer from 18 F-FDG PET/CT images. 2017;7(1):11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Peng H, Dong D, Fang M-J, Li L, Tang L-L, Chen L, et al. Prognostic value of deep learning PET/CT-based radiomics: potential role for future individual induction chemotherapy in advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. 2019;25(14):4271–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Moses WW. Fundamental Limits of Spatial Resolution in PET. Nuclear instruments & methods in physics research Section A, Accelerators, spectrometers, detectors and associated equipment. 2011;648 Supplement 1:S236–S40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tong S, Alessio AM, Kinahan PE. Image reconstruction for PET/CT scanners: past achievements and future challenges. Imaging in medicine. 2010;2(5):529–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hinton GE, Srivastava N, Krizhevsky A, Sutskever I, Salakhutdinov RR. Improving neural networks by preventing co adaptation of feature detectors. arXiv preprint arXiv:12070580. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ioffe S, Szegedy C. Batch normalization: Accelerating deep network training by reducing internal covariate shift. arXiv preprint arXiv:150203167. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yosinski J, Clune J, Nguyen A, Fuchs T, Lipson H. Understanding neural networks through deep visualization. arXiv preprint arXiv:150606579. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sankar V, Kumar D, Clausi DA, Taylor GW, Wong A. SISC: End-to-end Interpretable Discovery Radiomics-Driven Lung Cancer Prediction via Stacked Interpretable Sequencing Cells. arXiv preprint arXiv:190104641. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Luo Y, McShan D, Ray D, Matuszak M, Jolly S, Lawrence T, et al. Development of a fully cross-validated Bayesian network approach for local control prediction in lung cancer. IEEE transactions on radiation and plasma medical sciences. 2019;3(2):232–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ribeiro MT, Singh S, Guestrin C, editors. Why should i trust you?: Explaining the predictions of any classifier. Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining; 2016: ACM. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Selvaraju RR, Cogswell M, Das A, Vedantam R, Parikh D, Batra D, editors. Grad-cam: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chattopadhay A, Sarkar A, Howlader P, Balasubramanian VN, editors. Grad-cam++: Generalized gradient-based visual explanations for deep convolutional networks. 2018 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV); 2018: IEEE. [Google Scholar]

- 105.El Naqa I, Haider MA, Giger ML, Ten Haken RKJTBJoR. Artificial Intelligence: reshaping the practice of radiological sciences in the 21st century. 2020;93(1106):20190855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]