Abstract

In September, 2000, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health called an early halt to the amlodipine arm of the African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension (AASK) trial after careful deliberation by an independent data and safety monitoring board. An interim analysis of the AASK at 3 years revealed a renoprotective effect of the angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor ramipril as compared to the dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker (DHP‐CCB) amlodipine in patients with mild to moderate renal insufficiency. This differential effect was independent of the blood pressure levels reached and was evident in both proteinuric and non‐proteinuric patients with hypertensive nephrosclerosis. The AASK trial data suggest that DHP‐CCBs should be used cautiously in the presence of mild to moderate renal insufficiency. Judgment should be reserved for the use of other CCBs, such as verapamil or diltiazem, since these are fundamentally different CCBs with the potential for a different impact on hypertensive nephrosclerosis. The blinded observation period for AASK will be completed at the end of September, 2001, at which time additional, clinically useful information is expected to become available.

The impact of hypertension on highly vascular organs, such as the kidney, can be particularly devastating. The intimate nature of this relationship was suggested as early as 1836. Although the specific means by which hypertension produces renal structural damage is still open to conjecture, it is now well recognized that if hypertension is left untreated, there is a certain inexorability to the renal failure process, with the frequent development of end‐stage renal disease (ESRD). Furthermore, hypertension, the kidney, and progressive renal disease may be influenced by, and exert influence on, a number of other cardiovascular illnesses, including congestive heart failure and coronary artery disease.

Once established, hypertension is associated with a more rapid loss of renal function in patients with acquired renal disease, as well as acceleration of the more moderate loss of renal function associated with normal aging. Hypertension may also initiate renal disease. The incidence of true hypertensive nephropathy has proved difficult to quantify, as the presence of hypertension and absence of a renal biopsy often lead to a presumptive rather than a definitive diagnosis of hypertensive nephropathy. Nonetheless, the incidence of ESRD presumed secondary to essential hypertension is considerable and particularly high in African American patients. 1 The tendency for African American hypertensives to develop ESRD has also been associated with familial clustering (albeit with a poorly worked‐out genetic pattern), 2 birth weight less than 2500–3000 grams, 3 higher systolic blood pressure readings, and lower socioeconomic status. 1

Even with treatment there is no certainty that the kidney in an African American hypertensive is necessarily shielded; debate persists over the optimal blood pressure for preservation of renal function, and questions remain concerning which antihypertensive medication(s) most enhance renal protection. These questions, which have existed for some time, provided the basis for the African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension (AASK).

STUDY DESIGN

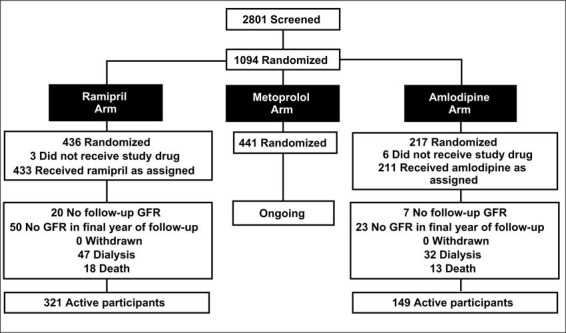

The AASK is an ongoing study in self‐identified African Americans with hypertension, aged 18–70 years, with a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) between 20 and 65 ml/min ṁ 1.73 m2. The trial population includes nondiabetic African Americans with a urinary protein to creatinine ratio of <2.5 and no significant systemic illness. Twenty‐one clinical centers, with support from a central data coordinating center and a data and safety monitoring board, form the working nucleus of this trial. Between February, 1995 and September, 1998, 1094 subjects were enrolled in this study and randomized (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Clinical trial profile for the African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension (AASK) Trial. Adapted with permission from JAMA. 2001;285:2719–2728. 6

The trial design is 3 × 2 factorial, with patients randomized to a usual mean arterial pressure (MAP) goal of 102–107 mm Hg or to a low MAP goal of <92 mm Hg. 4 Patients were randomly assigned to one of three antihypertensive agents: the β blocker metoprolol (Toprolol XL®) at 50–200 mg/day; the ACE inhibitor ramipril (Altace®) at 2.5–10 mg/day; or the dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker (DHP‐CCB) amlodipine (Norvasc®) at 5–10 mg/day. The randomization scheme for this study was an uneven block design with a 2:2:1 ratio for metoprolol:ramipril:amlodipine, respectively. Thus, 441 patients were assigned to metoprolol, 436 patients to ramipril, and 217 to amlodipine (Fig. 1). This design was used because AASK pilot data showed an early increase in GFR in the DHP‐CCB group compared to the ACE inhibitor and β‐blocker groups. 5 This early observation favorably influenced the statistical power of the study, allowing a smaller number of subjects in the DHP‐CCB group. If maximum tolerated doses of the blinded drug failed to effect the assigned blood pressure goal, additional unmasked drug could be added in the following suggested order: furosemide, doxazosin, clonidine, hydralazine, or minoxidil.

GFR was measured twice at baseline by iothalamate clearance; thereafter, it was measured at 3 and 6 months and every 6 months for the remainder of the study. Serum and urinary levels of both creatinine and protein were measured semiannually. 6

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The primary analysis of renal function is through the rate of change of GFR, presented as a GFR slope. This slope was determined during the first 3 months of the study, and subsequently at time points specified in the protocol. Distinguishing early from later slope determinations is important. Antihypertensive therapy can “reset” the GFR in the early treatment phase, and this process differs substantially from the long‐term effects of antihypertensive therapy on the progression of renal disease. The phenomenon of a change in GFR upon starting antihypertensive therapy is particularly prominent with ACE inhibitors. 7 The data analysis takes into account both phases and determines both the mean chronic slope (3 months to the end of the follow‐up) and the mean total slope (from baseline to the end of follow‐up). The mean total slope reflects the effect of the interventions on renal function during the entire study period, while the chronic slope reflects long‐term disease progression and not acute hemodynamic change.

The protocol also designated a main secondary analysis of clinical outcome based on the time from randomization to any of the following end points: 1) a confirmed reduction in GFR by 50% or by 25 ml/min from the mean of the two baseline GFR determinations; 2) the need for renal replacement treatment (ESRD); and 3) death. The clinical end point analysis is important in that it is the principal indicator of patient benefit, since it is based on events of clear clinical import. Finally, urinary protein excretion, expressed as the urinary protein: creatinine ratio (UP/Cr), was specified as a secondary outcome variable. UP/Cr correlates well with timed urine protein excretion determinations. 8

RESULTS

Selected baseline characteristics of the study population are presented in Table I. Figure 1 provides details on patient recruitment and retention. There were no significant differences among the study groups. The mean baseline blood pressure was 151/96 mm Hg; approximately 40% and 46% of the population were taking an angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or a DHP‐CCB, respectively, prior to the study. The UP/Cr exhibited a bimodal distribution for the entire study population, with a median value of 112 mg/day. There was an obvious inverse relationship between the level of renal function and the median value of UP/Cr. For example, for GFR values greater than 60, between 30 and 60, and less than 30 ml/min ṁ 1.73 m2, the median UP/Cr was 0.04, 0.07, and 0.47, respectively.

Table I.

Baseline Study Characteristics in the AASK Trial

| Ramipril (n=436) | Amlodipine (n=217) | |

| Age (years) | 54.2±10.9 | 54.4±10.7 |

| Female (%) | 38.8 | 40.1 |

| Blood pressure (mm Hg) | 151±23.3/96±14.5 | 150±25.3/95.7±14.1 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | ||

| Males | 2.18±0.74 | 2.27±0.83 |

| Females | 1.76±0.59 | 1.76±0.59 |

| Years of hypertension | 13.3±9.9 | 14.6±10.0 |

| Urinary protein (g/day) | ||

| Males | 0.61±1.01 | 0.57±0.99 |

| Females | 0.40±0.75 | 0.38±0.73 |

| Antihypertensive use (%) | ||

| ACE inhibitors | 39.9 | 41.5 |

| Beta blockers | 25.9 | 28.1 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 62.8 | 61.3 |

| Dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers | 46.6 | 44.7 |

| Values are means±SD. AASK=African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension; ACE=angiotensin‐converting enzyme | ||

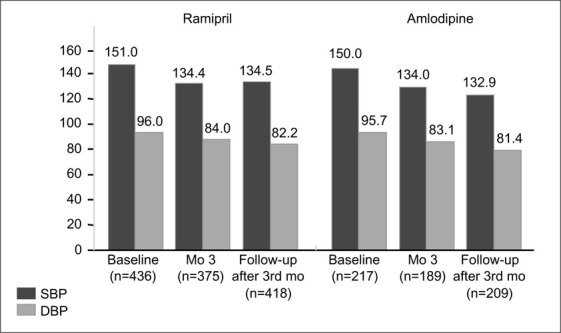

The median duration of GFR follow‐up was similar between the ramipril and amlodipine groups: 37 and 36 months, respectively. Follow‐up blood pressure values were substantially and comparably reduced relative to baseline (Fig. 2). Between the ramipril and amlodipine treatment limbs, there was no difference in either the number of antihypertensive medications prescribed or the number of patients receiving the maximum titrated doses. At baseline in the ramipril group, the average number of drugs used was 2.40; it increased to 2.80 at 3 months into the study, and leveled out at 2.75 at follow‐up after 3 months. At baseline in the amlodipine group, the average number of drugs administered was 2.48; it increased to 2.64 at 3 months into the study, and was 2.75 at follow‐up after 3 months. In the ramipril and amlodipine groups, 57.4% and 56.7% of the subjects, respectively, received the highest doses (10 mg/day of each drug), as specified by the protocol.

Figure 2.

Blood pressure response to ramipril and amlodipine at baseline, 3 months into treatment, and in follow‐up after month 3 in the African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension (AASK) Trial. Blood pressure values at baseline and during treatment did not differ between treatment groups. SBP=systolic blood pressure; DBP=diastolic blood pressure. Adapted with permission from JAMA. 2001;285:2719–2728. 6

The results from AASK can be divided into three categories: renal function analysis, clinical end point analysis, and proteinuria. Because increased protein excretion seems to have been an important determinant of the study findings, information on the three result categories is stratified by a protein excretion cut‐off value of >0.22, which equates with 24‐hour protein excretion of about 300 mg. Patients with gross proteinuria (UP/Cr of >2.5) were specifically excluded from the study. Furthermore, and importantly, the data separated the rate of decline of renal function into two groupings: 1) a rate of decline in function that includes values obtained in the first 3 months after randomization (total slope); and 2) a rate of decline in function that ignored the determination of GFR in the first 3 months (chronic slope). Finally, there was no prestudy washout period, since such was felt to be unethical in this target population. Thus, participants were required to have only one diastolic blood pressure reading of >95 mm Hg or their antihypertensive medication dose was tapered until they met this criterion.

Renal Function Analysis.

During the chronic phase, the rate of decline in renal function was 36% slower in the ramipril group than in the amlodipine group (2.07 ml/min/yr vs. 3.22 ml/min/yr ṁ 1.73 m2 (p=0.002). During the acute phase, the GFR actually increased in the amlodipine group, compared to the ramipril group (4.03 ml/min vs. −0.16 ml/min ṁ 1.73 m2). For this reason, the mean value for the rate of decline (a composite of the acute and chronic phases) did not differ significantly (p=0.38) between the treatment groups. With amlodipine therapy, the acute rise in GFR was seen only in subjects with UP/Cr of ≤0.22. Because of this, in the group of patients with UP/Cr of ≤0.22, the mean decline in GFR to 3 years was actually faster in the ramipril group (1.22 ml/min/yr •1.73 m2).

The AASK study was not designed to determine if the increase in GFR after starting a DHP‐CCB conferred benefit on long‐term renal outcome.

Finally, consistent with the inverse association between GFR and proteinuria at the start of the study, there was a relationship among baseline GFR, the treatment, and the manner in which GFR changed during the acute or chronic phases of surveillance. The total mean decline in GFR to 3 years was 0.97 ml/min/yr • 1.73 m2 faster in the ramipril group if the baseline GFR was at least 40 ml/min/yr • 1.73 m2. However, it was 1.61 ml/min/yr • 1.73 m2 faster in the amlodipine group if the baseline GFR was less then 40 ml/min/yr • 1.73 m2.

Clinical End Point Analysis.

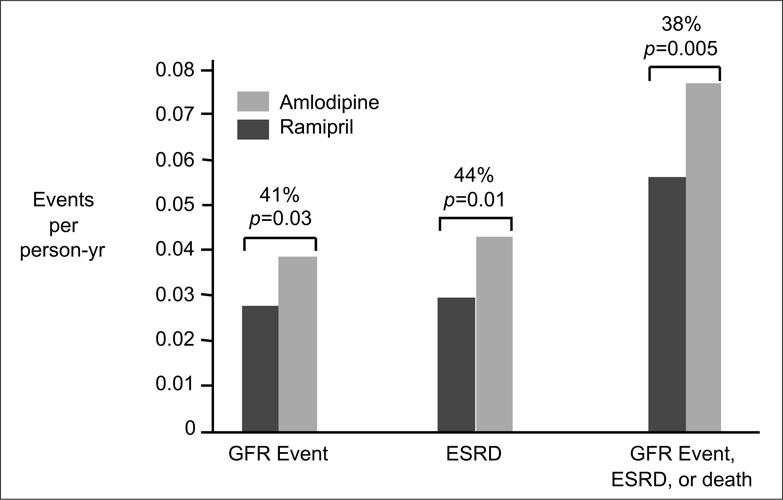

A total of 143 end points occurred in the ramipril and amlodipine groups, of which 73 were GFR events as defined by the protocol. Forty additional end points occurred in participants who reached ESRD but did not have a formally defined renal event. The remaining 30 end points occurred in participants who died without a prior GFR event or ESRD. After adjustment for prespecified covariates, the risk reduction with ramipril, relative to a GFR event, death, or ESRD, was 38% (Fig. 3). For the combined end points of ESRD or death, it was 41%, and for the two renal end points—a major decline in the GFR or dialysis—it was 38%. Although baseline proteinuria did not significantly influence the risk reduction for clinical end points, the majority of end points occurred in the patient subgroup with UP/Cr of >0.22. Of the 143 confirmed end points, 90 (62.9%) occurred in this group.

Figure 3.

Relative risk reduction for glomerular filtration rate (GFR) events (a confirmed reduction in GFR by 50% or by 25 ml/min/1.73 m2 from the mean of the two baseline GFR determinations), progression to end‐stage renal disease (ESRD), or the composite of GFR events, ESRD, or death. Adapted with permission from JAMA. 2001;285:2719–2728. 6

Proteinuria.

Proteinuria increased by 58% in amlodipine‐treated patients and declined by 20% in the ramipril group during the first 6 months of the study. Thereafter, protein excretion increased in both groups, but the percentage of increase was significantly higher in the amlodipine‐treated group. The magnitude of this difference was greatest in patients with UP/Cr of >0.22. Moreover, the rate at which UP/Cr of <0.22 progressed to UP/Cr of >0.22 was 56% slower in the ramipril‐treated group than in the amlodipine‐treated group.

DISCUSSION

The costs of managing hypertension, renal failure, and associated cardiovascular conditions are significant. In the United States, these problems are accentuated in the African American population. Among the disease‐state disparities that exist for African Americans, the development and/or progression of renal failure to ESRD is particularly striking. 1 Unfortunately, well accepted therapies by which renal failure progression can be slowed, such as ACE inhibition and angiotensin receptor blockade, have not been formally tested in significant numbers of African Americans with hypertension and renal disease. 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 Thus, many in the scientific community eagerly anticipated the results of the AASK study.

This study proposed to investigate the impact on progression of hypertensive renal disease of lowering blood pressure to two different goal levels with one of three different antihypertensive medication classes. The drug classes employed include an ACE inhibitor (ramipril), a β blocker (metoprolol), and a DHP‐CCB (amlodipine). The study began in February, 1995, and recruitment was completed in September, 1998. The decision to discontinue the amlodipine arm early was announced at the 33rd Annual Meeting of the American Society of Nephrology (Toronto, Canada, October 13–16, 2000), and the results of an interim analysis of the comparison of the amlodipine and ramipril arms were presented. The early cessation of the amlodipine arm was based on careful deliberation by an independent data safety monitoring board. The ramipril and metoprolol arms of AASK, as well as blood pressure goals, will continue until the study is completed, in September of 2001. The key findings of this study are presented in Table II.

Table II.

Key Points of the AASK Trial

| Treatment with ramipril was significantly better than amlodipine in slowing the progression of renal disease in patients with a baseline urine protein:creatinine ratio of >0.22 (300 mg protein/day). |

| In the entire cohort, after adjusting for prespecified baseline covariates, ramipril was associated with risk reduction in time of progression to the following clinically relevant end points as compared to amlodipine: 41% risk reduction for ESRD or death, and 38% risk reduction for GFR events, ESRD, or death. |

| The reduction in risk of the combined end points of ESRD, death (frank proteinuria), or GFR was influenced heavily by the subgroup of patients with baseline proteinuria; this subgroup contributed 63% of the events, although it represented only 33% of the cohort. |

| Treatment with amlodipine increased proteinuria by 58% in the first 6 months, whereas treatment with ramipril decreased proteinuria by 20%. The rate at which UP/Cr of <0.22 progressed to >0.22 was 56% lower in the ramipril‐treated group than in the amlodipine group. |

| At the end of follow‐up, there was no between‐treatment difference in the decline in GFR among patients with no baseline proteinuria or a GFR of at least 40 ml/min • 1.73 m2, which was related to the fact that amlodipine‐treated patients experienced an acute rise in GFR shortly after beginning therapy. |

| AASK=African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension; ESRD=end‐stage renal disease; GFR=glomerular filtration rate; UP/Cr=urinary protein/creatinine ratio |

This interim analysis unquestionably demonstrates that, relative to amlodipine, ramipril is renoprotective in African Americans with hypertensive nephrosclerosis and proteinuria beyond the threshold of clinically significant “dipstick‐positive” values (UP/Cr of >0.22, or >300 mg/day). This conclusion is supported by several of the findings from the AASK trial, including a significant reduction in risk of the clinical composite outcome, a slower decline in the GFR, and a reduction in urinary protein excretion with ramipril as compared to amlodipine. The findings in the non‐proteinuric study participants, although more subtle, in no way contradict the superiority of ACE inhibitor‐based regimens in African American patients with hypertensive nephrosclerosis.

In non‐proteinuric African American patients with hypertensive nephrosclerosis, what were the findings that supported the conclusion that ramipril is superior? First, there was a reduction in the time to an event in the entire group, as well as a reduction in urinary protein excretion. Second, compared to amlodipine treatment, ramipril administration resulted in a 56% reduction in the progression to clinically significant proteinuria (UP/Cr of >0.22, or >300 mg/day). It is of interest that prior reports of the beneficial effect of ACE inhibition in both diabetic and nondiabetic renal insufficiency cited higher levels of daily protein excretion as the threshold for demonstration of renoprotection. 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 This interim analysis of the AASK data set suggests a significantly lower threshold of proteinuria for an ACE inhibitor benefit but does not define the specific cut‐off point.

This interim analysis is also noteworthy in that this is the first outcome trial to demonstrate a significant beneficial effect of ACE inhibition in African Americans. Moreover, these results emphasize the importance of ACE inhibitors in the prevention of target organ damage, a process that appears to extend beyond the positive benefit(s) of blood pressure control alone. 16 The AASK trial was not mechanism‐oriented, so one can only speculate on the reasons for the benefits of ramipril in these studies. Changes in angiotensin II effect have been proffered as at least a partial explanation for these findings. Angiotensin II exhibits protean tissue and cellular effects in the kidney, in addition to its well established deleterious effect on renal hemodynamics. 17 The former includes augmentation of growth factor production, an increase in oxidative stress, and altered extracellular matrix production, among other actions. 18 , 19 The potential exists for any of these effects, either individually or collectively, to facilitate progression of hypertensive nephrosclerosis.

It should be stressed that the capacity of an ACE inhibitor to reduce urinary protein excretion is an important additional mechanism, capable of retarding progression of renal disease. 20 Because microalbuminuria and frank proteinuria are risk factors for cardiovascular as well as renal disease, the ability to reduce urinary protein excretion is generally viewed as a desirable drug attribute. 21 , 22 The AASK trial was not designed to address the mechanistic bridge between the improved renal and cardiovascular outcomes and the reduction in protein excretion. The findings, however, provide additional support to the therapeutic maxim that if urinary protein excretion is increased, it should be reduced by any means possible.

Finally, the literature is replete with suggestions that ACE inhibitor monotherapy is not very effective in hypertensive African Americans. 23 This has created hesitancy to use these drugs as monotherapy in hypertensive African Americans, which evidently extends to the use of ACE inhibitors in this population as part of a multidrug regimen. The findings from the AASK trial should dispel this myth, as they demonstrate that when an ACE inhibitor is used in combination with a diuretic and/or other agents, blood pressure control is achieved and maintained and renoprotection is readily apparent. Moreover, AASK demonstrates that the number of drugs, the percentage of participants on diuretics, and the achieved blood pressure (133/82 mm Hg) were similar for participants randomized to either amlodipine or ramipril, strengthening the argument that the renoprotective effect of ramipril, as compared to amlodipine, is independent of the achieved blood pressures.

CONCLUSION

Where does the AASK trial take the practicing clinician? It should be clear from the data that ACE inhibitor therapy is important in the African American patient with hypertensive nephrosclerosis and that in these patients, particularly when dipstick‐positive proteinuria is present, DHP‐CCB should not be the primary drug therapy. Considerable circumstantial evidence has been amassed over the past several years that suggests that DHP‐CCB treatment, unaccompanied by an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker, carries a risk of increasing proteinuria and/or accelerating progression of renal disease despite substantially reduced blood pressure. 24 , 25 The AASK study supports these conclusions, but it does not answer the question of whether the superimposition of an ACE inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker attenuates the negative renal effects of a DHP‐CCB.

Should all African American renal failure patients with hypertensive nephrosclerosis be excluded from therapy with amlodipine or similar DHP‐CCBs? The answer to this is probably no, since DHP‐CCBs remain important tools in the control of stage II–III hypertension, a very common form of hypertension in the African American. The data from the AASK trial indicate that for patients without proteinuria, who are therefore at lower risk, treatment with amlodipine carried minimal, if any, risk. It should be recognized that close to three drugs were required to achieve blood pressure reduction in the participants of the AASK trial, and that to achieve tight blood pressure control, DHP‐CCBs can be of particular utility. An alternative approach may be to employ non‐DHP‐CCBs, such as verapamil or diltiazem, when giving either drug alone or together with an ACE inhibitor allows the potential for more favorable renal interactions. 26

References

- 1. Klag MJ, Whelton PK, Randall BL, et al. End‐stage renal disease in African‐American and white men. 16‐year MRFIT findings. JAMA. 1997;277:1293–1298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Freedman BI, Iskandar SS, Appel RG. In‐depth review: the link between hypertension and nephrosclerosis. Am J Kidney Dis. 1995;25:207–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lopes AAS, Port FK. The low birth weight hypothesis as a plausible explanation for the black/white difference in hypertension, non‐insulin dependent diabetes, and end‐stage renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 1995;25:350–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wright JT Jr, Kuzek JW, Toto RD, et al. Design and baseline characteristics in African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension (AASK) Pilot Study. Control Clin Trials. 1996;17(suppl 4):3S–16S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hall WD, Kusek JW, Kirk KA, et al. Short‐term effects of blood pressure and antihypertensive drug regimen on glomerular filtration rate: the African‐American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension Pilot Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 1997;29:720–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Agodoa LY, Appel L, Bakris G, et al., for the African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension (AASK) Study Group . Effect of ramipril vs. amlodipine on renal outcomes in hypertensive nephrosclerosis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;285:2719–2728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bakris GL, Weir MR. Angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor‐associated elevations in serum creatinine: is this a cause for concern? Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:685–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ruggenenti P, Gaspari F, Perna A, et al. Cross sectional longitudinal study of spot morning urine protein:creatinine ratio, 24 hour urine protein excretion rate, glomerular filtration rate, and end‐stage renal failure in chronic renal disease in patients without diabetes. BMJ. 1998;316:504–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Giatras I, Lau J, Levey AS, for the Angiotensin‐Converting Enzyme Inhibition and Progressive Renal Disease Study Group . Effect of angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors on the progression of nondiabetic renal disease: a meta‐analysis of randomized trials. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:337–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Maschio G, Alberti D, Janin G, et al. Effect of the angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor benazepril on the progression of chronic renal insufficiency. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:939–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Bain RP, et al. The effect of angiotensin‐converting‐enzyme inhibition on diabetic nephropathy. The Collaborative Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1456–1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ruggenenti P, Perna A, Gherardi G, et al. Renal function and requirement for dialysis in chronic nephropathy patients on long‐term ramipril: REIN follow‐up trial. Gruppo Italiano di Studi Epidemiologici in Nefrologia (GISEN). Ramipril Efficacy in Nephropathy. Lancet. 1998;352:1252–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Klahr S, Levey AS, Beck GJ, et al. Blood pressure control, proteinuria, and the progression of renal disease. The Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:754–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rodby RA, Rohde RD, Clarke WR, et al., for the Collaborative Study Group . The irbesartan type II diabetic nephropathy trial: study design and baseline patient characteristics. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2000;15:487–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brenner BM, Cooper ME, De Zeeuw D, et al. The losartan renal protection study—rationale, study design and baseline characteristics of RENAAL (Reduction of Endpoints in NIDDM with the Angiotensin II Antagonist Losartan). J RAS. 2000;1:328–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sica DA. The Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation (HOPE) Study: limitations and strengths. J Clin Hypertens. 2000;2:406–414. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Johnston CI, Risvanis J, Naitoh M, et al. Mechanism of progression of renal disease: current hemodynamic concepts. J Hypertens. 1998;16(suppl):S3–S7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Benigni A, Remuzzi G. How renal cytokines and growth factors contribute to renal disease progression. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;37(suppl 2):S21–S24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wolf G. Molecular mechanisms of angiotensin II in the kidney: emerging role in the progression of renal disease: beyond haemodynamics. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13:1131–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Abbate M, Remuzzi G. Proteinuria as a mediator of tubulointerstitial injury. Kidney Blood Press Res. 1999;22:37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bakris GL, Williams M, Dworkin L, et al., for the National Kidney Foundation Hypertension and Diabetes Executive Committees Working Group . Preserving renal function in adults with hypertension and diabetes: a consensus approach. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;36:646–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Marre M. Microalbuminuria and prevention of renal insufficiency and cardiovascular diseases. Am J Hypertens. 1998;11:884–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Flack JM, Mensah GA, Ferrario CM. Using angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors in African‐American hypertensives: a new approach to treating hypertension and preventing target‐organ damage. Curr Med Res Opin. 2000; 16:66–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ruggenenti P, Perna A, Gherardi G, et al. Renoprotective properties of ACE‐inhibition in non‐diabetic nephropathies with non‐nephrotic proteinuria. Lancet. 1999; 354:359–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kloke HJ, Branten AJ, Huysmans FT, et al. Antihypertensive treatment of patients with proteinuric renal diseases: risks or benefits of calcium channel blockers? Kidney Int. 1998;53:1559–1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bakris GL, Weir MR, DeQuattro V, et al. Effects of an ACE inhibitor/calcium antagonist combination on proteinuria in diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int. 1998;54: 1283–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]