Abstract

Objectives:

To examine the association between frequency of family member accompaniment to medical visits and heart failure (HF) self-care maintenance and management and to determine whether associations are mediated through satisfaction with provider communication.

Methods:

Cross-sectional survey of 150 HF patients seen in outpatient clinics. HF self-care maintenance and management were assessed using the Self-Care of Heart Failure Index. Satisfaction with provider communication was assessed using a single question originally included in the American Board of Internal Medicine Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire. Frequency of family member accompaniment to visits was assessed using a single-item question. We performed regression analyses to examine associations between frequency of accompaniment and outcomes. Mediation analysis was conducted using MacKinnon’s criteria.

Results:

Overall, 61% reported accompaniment by family members to some/most/every visit. Accompaniment to some/most/every visit was associated with higher self-care maintenance (β=6.4, SE 2.5; p=0.01) and management (β=12.7, SE 4.9; p=0.01) scores. Satisfaction with provider communication may mediate the association between greater frequency of accompaniment to visits and self-care maintenance (1.092; p=0.06) and self-care management (1.428; p=0.13).

Discussion:

Accompaniment to medical visits is associated with better HF self-care maintenance and management, and this effect may be mediated through satisfaction with provider communication.

Keywords: Family, heart failure, self-care, patient–provider communication, social support

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a complex chronic illness affecting almost six million Americans. HF prevalence is expected to increase as the population ages.1 It is a leading cause of preventable hospitalizations among the elderly.2–4 There is an increasing recognition of the importance of social environmental factors, particularly the “post-discharge environment,” on HF.5–9 Social support, in particular, has great potential to improve HF outcomes in part through its effect on HF self-care.10–13

Family members influence HF self-care at home and care delivery during medical visits. HF self-care involves engaging in behaviors to maintain physiologic stability (e.g., adhering to medication and frequent weighing) and decision making in response to symptoms (e.g., recognizing signs of fluid overload and taking an extra dose of a diuretic).14 Approximately 15–60% of adult patients are accompanied to visits by a family member.15,16 Accompaniment can be conceptualized as a form of social support—including tangible (e.g., source of transportation), emotional (e.g., moral support), or informational (e.g., helping facilitate patient–provider communication)—which is predictive of cardiovascular outcomes.17,18 However, accompaniment may not be feasible for many family members due to work or other responsibilities during usual clinic hours. Therefore, it is important to assess the prevalence of alternate modes of family involvement, such as communicating with providers via email or telephone. Clinical practice guidelines suggest that HF patients and family members should receive education and counseling that emphasizes self-care.19 The medical visit is the setting where that education is likely to naturally occur.

Family accompaniment to visits may influence chronic illness self-care, although few studies have empirically tested this association.20 Moreover, mechanisms through which accompaniment influences HF self-care are largely unknown. When family members accompany patients to medical visits, their presence facilitates patient–provider communication and enhances patients’ satisfaction with their provider.16,21,22 Understanding the frequency and mechanisms by which family involvement influences HF care and outcomes is critical to the design of family-based HF self-care interventions. The aims of this study were to examine the association between frequency of family accompaniment to medical visits and HF self-care behaviors and determine whether any observed associations are mediated through greater satisfaction with provider communication.

Methods

Design

We conducted an observational study with a cross-sectional analysis of survey data collected from HF patients after receiving Institutional Review Board approval.

Sample

Participant recruitment, including eligibility criteria, has been previously described.10 Briefly, we recruited HF patients from the general internal medicine or cardiology clinics at one university hospital. Participants were identified as part of a screening process for study recruitment using the Carolina Data Warehouse for Health (CDW-H)—a central repository containing clinical, research, and administrative data from over three million patient records of individuals who have received care in the UNC Health Care System. The CDW-H includes all of the information available in the electronic medical record. After initial screening, we compiled a list of potentially eligible participants and also reviewed daily clinic schedules and medical records for additional potential participants. After verifying the diagnosis of HF and suitability to participate in the study with the patient’s health care provider, a research assistant (RA) directly approached potential participants at the time of a regularly scheduled medical visit to determine their interest in participating. For interested individuals, the RA verified eligibility and obtained informed consent. RAs administered the questionnaire to participants in person immediately prior to the visit or via telephone if the participant was unable to complete it at the visit.

Data collection

Demographic and clinical characteristics.

We used the CDW-H and/or participant self-report to obtain information on age, race (black vs. white), gender, highest educational level, marital status, depressive symptoms, cognitive impairment, number of people living in the household, self-rated health, New York Heart Association (NYHA) class, and ejection fraction. NYHA class was assessed using a structured question. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) 10-item measure.23 We used the Blessed test of Orientation-Memory-Concentration to assess cognitive impairment.24 Satisfaction with family functioning was measured using the Family Adaptability Partnership Growth Affection and Resolve (APGAR).25

HF self-care.

We used the 22-item Self-Care of Heart Failure Index version 6.2 to measure self-care maintenance and self-care management (outcome variables).14 The 10-item self-care maintenance scale assesses behaviors used to maintain physiologic stability (e.g., adherence to medications and frequent weighing). The six-item self-care management scale assesses decision making in response to symptoms (e.g., recognizing signs of fluid overload and taking an extra dose of a diuretic). The internal reliability for the scales has previously been reported as 0.55 for maintenance and 0.60 for management.14 In this study, alpha coefficients were 0.46 for maintenance and 0.65 for management. Notably, the self-care management questions are answered and scored only if the respondent reports having experienced dyspnea or ankle swelling within the past month. Each scale score is standardized, with scores ranging from 0 to 100 (higher scores indicate better self-care). Scores ≥70 are reflective of “adequate” self-care. A change in scale score of one-half of a standard deviation or more is considered clinically significant.14

Family involvement in medical care.

No well-validated measures exist to assess family involvement in medical care. To assess family involvement, we used three questions that were developed and pilot tested in adult patients with HF and diabetes mellitus by colleagues at the University of Michigan.26 For the main analysis, we measured accompaniment to medical visits with the question, “How often does one of your family members or friends come in the exam room with you for your doctor’s visit?” The response options were “none of the time,” “rarely,” “some visits,” “most visits,” or “every visit.” To understand other modes of family–physician interaction, we also asked two other questions: (1) “how many times in the past year has one of your family members or friends talked on the phone to your doctor about your care?” and (2) “how many times in the past year has one of your family members or friends written letters or emails to your doctor about your care?” Categorical response options for both questions were “none,” “1–2 times,” “3–4 times,” or “more than four times.”

Satisfaction with provider communication.

We assessed patient satisfaction with provider communication using a question from the American Board of Internal Medicine Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire.27 The question asks the respondent to rate the doctor who takes care of your HF in the following four areas: (1) telling you everything, (2) letting you know test results when promised, (3) explaining treatment alternatives, and (4) telling you what to expect from treatment. Each item is scored using a five-point (poor–excellent; 0–4) scale, with a total score ranging from 0 to 16.

Data analysis

We performed analyses using SAS 9.2. (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and R 3.0.0 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria).28 We calculated means and frequencies to describe the distribution of the data by categories of frequency of family accompaniment. For normally distributed interval data, we used t-tests. For non-normally distributed data, such as educational level, CES-D, and cognitive impairment score, we used the Mann–Whitney U-test. We used Chi-squared tests to compare frequencies. For the main analysis, we conducted multiple regression analysis to determine the independent effect of frequency of family accompaniment to medical visits on HF self-care maintenance and self-care management after adjusting for the following confounders which have been shown or hypothesized to relate to self-care behaviors and accompaniment: age, race, gender, educational level, marital status, self-rated health, NYHA class, depressive symptoms, cognitive impairment, and satisfaction with family relationships. In separate regression analyses, we examined associations between two questions related to family/friend communication with doctors and HF self-care maintenance and management.

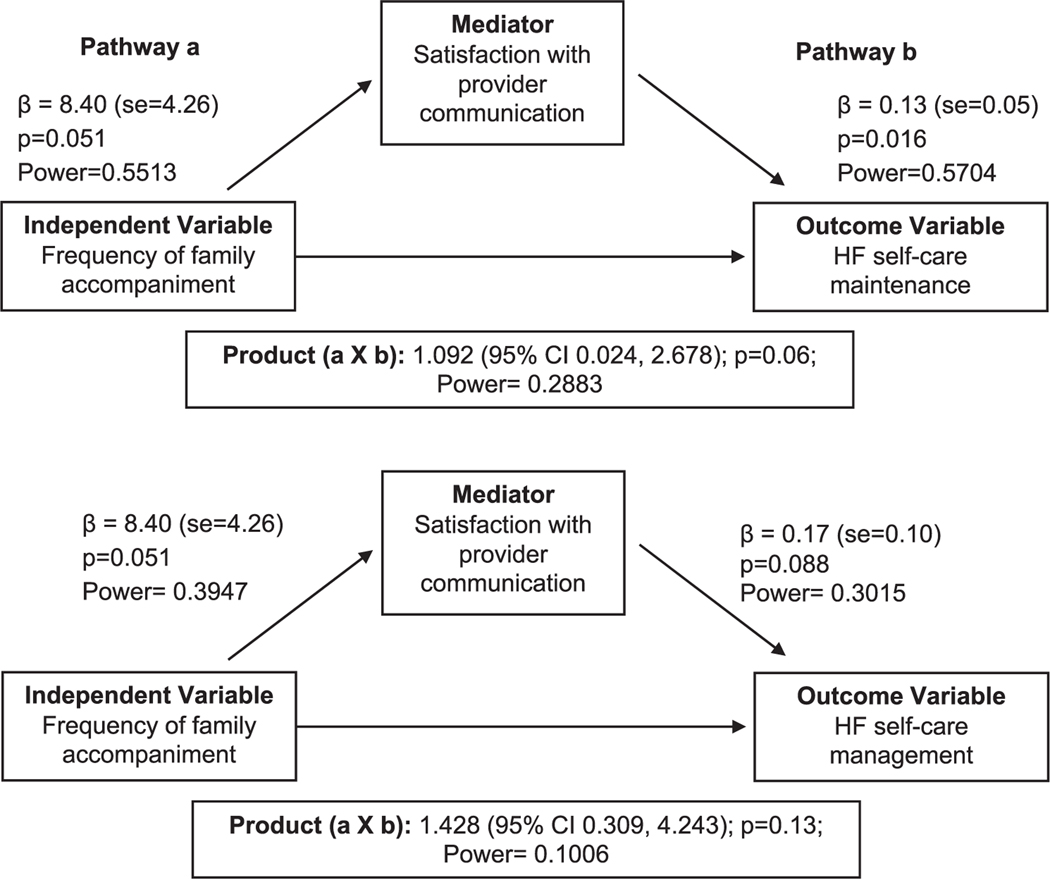

Mediation hypotheses are commonly used in social psychology research and represent the generative mechanism through which the focal independent variable influences the dependent variable.29 We conducted mediation analyses to examine whether satisfaction with provider communication mediated the association between frequency of family accompaniment and HF self-care maintenance and management behaviors (Figure 1). Using methods recommended by MacKinnon et al.,30 satisfaction with provider communication was required to meet the following criteria to be considered a mediator: (a) variations in the levels of the independent variable (frequency of family accompaniment) significantly accounted for variations in the presumed mediator (satisfaction with provider communication); (b) variation in the mediator significantly accounted for variations in the dependent variables (HF self-care maintenance and self-care management); and the product of the two aforementioned regression coefficients (a × b), which is used to measure the mediation effect, is statistically significant (i.e., p ≤ .05 for all regression models). Although mediation analysis requires multiple tests to be conducted, it should be conceptualized as a single test (albeit with several conditions) that yields a single conclusion: significant evidence against the null hypothesis of no mediation. Given that the statistical power required to detect mediation is always lower than that required to detect a direct association between an explanatory and an outcome variable, we conducted a post hoc analysis to determine our statistical power to detect the observed effects (see results on Figure 1). One approach typically used to assess for mediation is to include the mediator in statistical models with other potential confounders. Therefore, we included all covariates in the mediational models.

Figure 1.

Mediational model showing the unstandardized multivariate linear regression coefficients (β) for the mediated pathways by which frequency of family accompaniment to medical visits influences HF self-care maintenance and self-care management.

Results

We identified 916 potentially eligible participants. Of those, 121 (13.2%) were ineligible based on inclusion/exclusion criteria. An additional 40 (5.3%) participants were not approved by providers. Out of the remaining 755 potential participants, 229 (30.3%) were approached, 13 refused to participate, and 163 (71.1%) agreed to participate and were consented. Of the 163, nine (5.5%) failed the Blessed Test; one (<1.0%) died before questionnaire administration, and three (1.8%) did not complete the questionnaire, leaving 150 (92%) who completed the study.

Demographics

Table 1 lists the overall sample characteristics stratified by frequency of accompaniment. The mean age of our sample was 61 years (range 22–84), 51% were female, 44% were African American, and mean educational level attained was 13 years. Overall, 61% of participants reported being accompanied by family members to some/ most/every visit. More females than male were never/rarely accompanied to visits. Participants who reported greater frequency of accompaniment had higher scores for satisfaction with their family functioning.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants overall and stratified by frequency of family accompaniment to medical visits.

| Overall sample (N = 148) | Never/rarely (N = 57) | Some/most/every visit (N = 91) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, years (SD) | 61 (12) | 61 (13) | 60(12) | 0.63 |

| Female, N (%) | 76 (51) | 37 (65) | 39 (43) | 0.01 |

| Black, N (%) | 66 (44) | 23 (40) | 42 (47) | 0.42 |

| Mean highest educational level (SD) | 13 (2.6) | l3 (2.6) | 13(2.4) | 0.21 |

| Annual household income, N (%) | ||||

| <$15,000 | 56 (41) | 24 (45) | 32 (40) | 0.67 |

| $l5,000-$24,999 | 29 (21) | 10 (19) | l9 (24) | |

| $25,000-$40,000 | 25 (l9) | 8(15) | 17(21) | |

| >$40,000 | 25 (l9) | 11 (21) | 13 (16) | |

| Currently married (vs. othera), N (%) | 59 (39) | l9 (33) | 38 (42) | 0.31 |

| Self-rated health, N (%) | ||||

| Excellent/very good/good | 56 (38) | 22 (39) | 33 (36) | 0.52 |

| Fair | 67 (45) | 27 (48) | 40 (44) | |

| Poor | 25(17) | 7(13) | l8 (20) | |

| Mean CES-D score (SD) | 9 (6.4) | 9 (7.0) | 8(6.1) | 0.57 |

| Mean Blessed test score (SD) | 3.3 (2.7) | 3.5 (2.8) | 3.1 (2.6) | 0.41 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction N (%) | ||||

| ≥55% | 53 (40) | 2l (44) | 30 (36) | 0.40 |

| 40–55% | 32 (22) | l3 (26) | l9 (22) | |

| <40% | 50 (37) | l5 (30) | 35 (42) | |

| New York Heart Association, N (%) | ||||

| Class I | 25(17) | 9(16) | 15 (16) | 0.96 |

| Class II | 8l (54) | 3l (54) | 50 (55) | |

| Class III | 31 (21) | l3 (23) | l8 (20) | |

| Class IV | 13(8) | 4 (7) | 8 (9) | |

| Mean family APGAR score (SD) | 7.7 (2.8) | 6.3 (3.3) | 8.5 (2.1) | <0.01 |

APGAR: Adaptability Partnership Growth Affection and Resolve; CES-D: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression.

Other refers to divorced/separated, widowed, single or unknown.

Forty-four percent of patients reported that their family or friends never talked on the phone to their doctor over the past year, while the percentage reporting that their family or friends talked to their doctor 1–2, 3–4, and >4 times were 25%, 13%, and 18%, respectively. Family- or friend- written communication with the doctor (via letters or email) was much less frequent, with 87% of patients reporting that this never occurred.

Accompaniment and HF self-care behaviors

Mean scores for self-care maintenance were 70 (SD 14), with 52% of the sample having “adequate” self-care maintenance (score ≥70). Mean score for self-care management was 57 (SD 24), with 32% of sample having “adequate” self-care management. Notably, 37 patients had missing values for the selfcare management data because they had not experienced symptoms. In bivariate analyses, highest educational level, less cognitive impairment, and higher satisfaction with family function were significantly associated with having higher self-care maintenance scores. Increasing age was the only covariate found to be significantly associated (p < 0.05) with having adequate self-care management. Patients who were accompanied to some/most/every visit, on average, had a self-care maintenance score that was 6.4 points higher than those who were never/rarely accompanied to visits in the adjusted model (Table 2). Similarly, after multivariable adjustment, patients who report being accompanied to some/most/ every visit, on average, had a self-care management score that was 12.7 points higher than those who were never/rarely accompanied to visits (Table 2). We found similar results when we examined frequency of family member accompaniment as a continuous rather than a dichotomous variable and the self-care outcome variables as dichotomous rather than continuous variables (data presented in Appendix 1).

Table 2.

Linear association between frequency of family accompaniment and HF self-care maintenance and self-care management.

| Self-care maintenance (N = 145) |

Self-care management (N = 111) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of family accompaniment to medical visits | Unadjusted Beta (SE) | Adjusteda Beta (SE) | Unadjusted Beta (SE) | Adjusteda Beta (SE) |

| Some/most/every visit (vs. never/rarely) | 7.2 (2.3)* | 6.4 (2.5)† | 12.8 (4.5)* | 12.7 (4.9)† |

HF: heart failure.

Adjusted for age, race, gender, educational level, marital status, self-rated health, New York Heart Association class, depressive symptom score, cognitive impairment and satisfaction with family function.

p< 0.01;

p= 0.01

Satisfaction with provider communication as a mediator

The sample mean for satisfaction with provider communication was 83.2 (SD 23.5). We examined whether the multivariate linear association between frequency of family accompaniment and HF self-care maintenance and self-care management was mediated through satisfaction with provider communication (Figure 1). Frequency of family accompaniment was associated with greater satisfaction with provider communication (Pathway a; β = 8.40, p = 0.05). Satisfaction with provider communication was significantly associated with HF self-care maintenance (Pathway b; β = 0.13, p = 0.02) but not with HF self-care management (Pathway b, lower part Figure 1; β = 0.17, p = 0.09). The product of the aforementioned path coefficients was marginally significant for HF self-care maintenance (1.092; p = 0.06) but not statistically significant for HF self-care management (1.428; p = 0.13) (Figure 1). In sum, satisfaction with provider communication may mediate relationships between frequency of family accompaniment and HF self-care maintenance and management (based on the strength of the effect estimates which are in the hypothesized direction); however, we lack sufficient power to demonstrate statistically significant associations at the p < 0.05 level (Figure 1 power estimates).

Discussion

We found that patients who reported being accompanied to some/most/every visit had significantly higher HF self-care maintenance and self-care management scores than those who reported never/rarely being accompanied, and the degree of change is considered clinically significant. We did not find evidence that satisfaction with provider communication mediates the association between frequency of accompaniment and self-care maintenance and self-care management based on the MacKinnon criteria.

To our knowledge, no other published studies have examined the association between frequency of family member accompaniment and HF self-care behaviors; therefore, we cannot directly compare our results with others. Based on our data, patient-reported prevalence of accompaniment into the examination room is fairly high in HF patients. This is consistent with other studies which find that 36–57% of older patients15 and 15–25% of all adult patients in primary care or outpatient clinics are accompanied.15,16 To the extent that accompaniment reflects a form of social support, previous studies have also shown that social support is associated with better HF self-care behaviors.31–34 We acknowledge that not all support is positive; family “support” can sometimes have detrimental effects on self-care behaviors.20,35,36 However, family members who accompany a patent into the exam room are likely those with whom the patient has a more positive and supportive relationship. Our finding that the mean Family APGAR score was significantly higher in those who reported greater frequency of accompaniment would support this assertion.

The quality of the education and counseling during medical visits sets the stage for how effectively patients manage a chronic illness at home. Family companions who are present in the examination room have a unique opportunity to hear and participate in the communication between HF patients and providers. Although the literature in this area is emerging, studies suggest that facilitation of patient–physician communication is one mechanism by which family companions exert their influence on health.16,37–39 Companions perform specific communication functions during the visit, including sharing information about the patient; recording the doctor’s comments or instructions; asking questions; and explaining the doctors’ instructions.16 The presence of medical visit companions has been associated with greater patient satisfaction with their doctor.16

We found no other studies that empirically tested whether satisfaction with communication mediates the association between accompaniment and HF self-care behaviors. Our data do not support evidence of a mediation effect through satisfaction with provider communication using the MacKinnon criteria largely due to insufficient statistical power. It may also be possible that the observed association is mediated through changes in actual communication behaviors (which were not assessed in this study) as opposed to satisfaction with communication.

Prior studies have demonstrated that patients’, companions’, and doctors’ attitudes toward and experiences with a companion’s presence in the exam room are generally more positive than negative.15,26 Patients generally prefer companion involvement in the medical visit.15 Companions facilitate greater understanding of and motivation to follow the doctor’s advice, help the patient discuss difficult or sensitive topics, help patients remember, and share important information with the doctor to inform treatment decisions.26 However, despite their perceived helpfulness, companions report negative experiences such as being actively excluded by health care professionals or feeling ignored during the visit.40 Doctors feel companions’ presence during the visit adds complexity and may imply that the patient is delegating decision-making authority.41 Future research should assess attitudes toward or experiences with accompaniment from various perspectives.

Our study has limitations. First, the data are cross-sectional, so we cannot determine the directionality of the associations or make causal inferences. Second, frequency of accompaniment and communication between family members and doctors was based on patient report and therefore subject to reporting bias. Third, patients who frequently bring family to their medical visits may systematically differ from patients who do not, in ways that affect self-care behaviors and communication; which may introduce selection bias. Last, we did not assess or “control” for patient preferences for accompaniment. It is possible that it is not frequency of accompaniment, but the effect of patient characteristics that are highly correlated with preferences for accompaniment, that are responsible for our observed associations.

This study has important implications for clinical care and research. Health care organizations have called for increased involvement of family in self-care support programs and have advocated for increased companion participation in clinical care.20,42,43 We demonstrate that family member accompaniment to medical visits is associated with better HF self-care. Adequate HF self-care is critical to enhancing HF outcomes. These findings suggest that clinicians should consider explicitly inviting family members into the exam room (if the patient desires their presence) to enhance HF self-care and possibly outcomes that are sensitive to self-care (e.g., hospitalizations). Larger studies, using longitudinal data, are needed to test mechanisms by which accompaniment to medical visits results in better HF self-care behaviors.

If family member accompaniment to visits is shown to result in better patient– provider communication, HF self-care, and outcomes, future research should help determine the best ways to (1) engage patients and family members during medical visits and (2) train providers to handle the added complexity of triadic visits. Participation of patients and families in care and decision making at the level they choose is a key principle of patient- and family-centered care.44 Therefore, encouraging family presence in the exam room at medical visits as a practical strategy for delivery of patient- and family-centered care may be valuable in and of itself, irrespective of its effects on clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the providers and staff in the General Internal Medicine and Cardiology clinics who allowed us to recruit their patients; our research staff (Ms Diane Dolon-Soto and Mr Justin Lucas) who administered the surveys; and patients who willingly agreed to participate in this study. We would also like to thank AnnMarie Rosland, MD, MS, for allowing us to use survey questions that she developed and used in her prior work.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Center for Research Resources [grant number KL2RR025746 (to CC) and UL1RR025747 (to GC-S)]; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [grant number K23HL107614 (toCC)]; a salary support provided by Midcareer Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Research [grant number K24 HL105493 (to GC-S)]; the National Cancer Institute [grant number 5K05CA129166 (to MP)]; the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health, through [grant award number 1UL1TR001111]; and a NIH/HRSA training grant as a NRSA Primary Care Research Fellow [grant number T32HP14001 (to CJ)].

Appendix.

Appendix 1

In multivariable analyses, we found statistically significant positive linear associations with self-care maintenance (β = 1.9, SE 0.85, p = 0.03) and self-care management (β = 3.6, SE 1.6, p = 0.03) as frequency of family accompaniment increases. We also conducted sensitivity analyses using “adequate” self-care maintenance and “adequate” selfcare management (scores ≥70) as outcome variables. These analyses revealed higher odds of having adequate HF self-care maintenance (AOR=2.1; 95% CI=0.9–4.7; p = 0.09) and self-care management (AOR=5.2; 95% CI=1.5–18.0; p < 0.01) for those with greater frequency of family accompaniment to medical visits.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics – 2009 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation 2009; 119: 480–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ross JS, Chen J, Lin Z, et al. Recent national trends in readmission rates after heart failure hospitalization. Circ Heart Fail 2010; 3: 97–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joynt KE and Jha AK. Who has higher readmission rates for heart failure, and why? Implications for efforts to improve care using financial incentives. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2011; 4: 53–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Epstein AM, Jha AK and Orav EJ. The relationship between hospital admission rates and rehospitalizations. N Engl J Med 2011; 365: 2287–2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marmot MG, Wilkinson RG (eds) Social determinants of health. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tao H, Ellenbecker CH, Chen J, et al. The influence of social environmental factors on rehospitalization among patients receiving home health care services. ANS Adv Nurs Sci 2012; 35: 346–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsuchihashi M, Tsutsui H, Kodama K, et al. Medical and socioenvironmental predictors of hospital readmission in patients with congestive heart failure. Am Heart J 2001; 142: E7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hersh AM, Masoudi FA and Allen LA. Postdischarge environment following heart failure hospitalization: expanding the view of hospital readmission. J Am Heart Assoc 2013; 2: e000116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arbaje AI, Wolff JL, Yu Q, et al. Postdischarge environmental and socioeconomic factors and the likelihood of early hospital readmission among community-dwelling Medicare beneficiaries. Gerontologist 2008; 48: 495–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cene CW, Haymore LB, Dolan-Soto D, et al. Self-care confidence mediates the relationship between perceived social support and self-care maintenance in adults with heart failure. J Card Fail 2013; 19: 202–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cameron J, Worrall-Carter L, Riegel B, et al. Testing a model of patient characteristics, psychologic status, and cognitive function as predictors of self-care in persons with chronic heart failure. Heart Lung 2009; 38: 410–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heo S, Moser DK, Lennie TA, et al. Gender differences in and factors related to self-care behaviors: a cross-sectional, correlational study of patients with heart failure. Int J Nurs Stud 2008; 45: 1807–1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rockwell JM and Riegel B. Predictors of self-care in persons with heart failure. Heart Lung 2001; 30: 18–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riegel B, Lee CS, Dickson VV, et al. An update on the self-care of heart failure index. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2009; 24: 485–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laidsaar-Powell RC, Butow PN, Bu S, et al. Physician-patient-companion communication and decision-making: a systematic review of triadic medical consultations. Patient Educ Couns 2013; 91: 3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolff JL and Roter DL. Hidden in plain sight: medical visit companions as a resource for vulnerable older adults. Arch Intern Med 2008; 168: 1409–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luttik ML, Jaarsma T, Moser D, et al. The importance and impact of social support on outcomes in patients with heart failure: an overview of the literature. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2005; 20: 162–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Riegel B, Moser DK, Anker SD, et al. State of the science: promoting self-care in persons with heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2009; 120: 1141–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, et al. 2009 Focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 guidelines for the diagnosis and management of heart failure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/ American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines: developed in collaboration with the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. Circulation 2009; 119: e391–e479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosland AM, Heisler M, Choi HJ, et al. Family influences on self-management among functionally independent adults with diabetes or heart failure: do family members hinder as much as they help? Chronic Illn 2010; 6: 22–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sayers SL, White T, Zubritsky C, et al. Family involvement in the care of healthy medical outpatients. Fam Pract 2006; 23: 317–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Botelho RJ, Lue BH and Fiscella K. Family involvement in routine health care: a survey of patients’ behaviors and preferences. J Fam Pract 1996; 42: 572–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, et al. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). Am J Prev Med 1994; 10: 77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katzman R, Brown T, Fuld P, et al. Validation of a short Orientation-Memory-Concentration Test of cognitive impairment. Am J Psychiatr 1983; 140: 734–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smilkstein G, Ashworth C and Montano D. Validity and reliability of the family APGAR as a test of family function. J Fam Pract 1982; 15: 303–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosland AM, Piette JD, Choi H, et al. Family and friend participation in primary care visits of patients with diabetes or heart failure: patient and physician determinants and experiences. Med Care 2011; 49: 37–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.American Board of Internal Medicine. Patient satisfaction questionnaire: guide to awareness and evaluation of humanistics qualities in the internist. Philadelphia, PA: American Board of Internal Medicine, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 28.The R Development Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2013, http://www.R-project.org/ (accessed 1 April 2014) [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baron RM and Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol 1986; 51: 1173–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, et al. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol Methods 2002; 7: 83–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gallagher R, Luttik ML and Jaarsma T. Social support and self-care in heart failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2011; 26: 439–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sayers SL, Riegel B, Pawlowski S, et al. Social support and self-care of patients with heart failure. Ann Behav Med 2008; 35: 70–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Riegel B, Lee CS, Dickson VV, et al. Self care inpatients with chronic heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol 2011; 8: 644–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Riegel B, Vaughan Dickson V, Goldberg LR, et al. Factors associated with the development of expertise in heart failure self-care. Nurs Res 2007; 56: 235–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Samuel-Hodge CD, Cene CW, Corsino L, et al. Family diabetes matters: a view from the other side. J Gen Intern Med 2013; 28: 428–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosland AM, Heisler M and Piette JD. The impact of family behaviors and communication patterns on chronic illness outcomes: a systematic review. J Behav Med 2012; 35: 221–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clayman ML, Roter D, Wissow LS, et al. Autonomy-related behaviors of patient companions and their effect on decision-making activity in geriatric primary care visits. Soc Sci Med 2005; 60: 1583–1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ishikawa H, Roter DL, Yamazaki Y, et al. Physician-elderly patient-companion communication and roles of companions in Japanese geriatric encounters. Soc Sci Med 2005; 60: 2307–2320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolff JL and Roter DL. Family presence in routine medical visits: a meta-analytical review. Soc Sci Med 2011; 72: 823–831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morris SM and Thomas C. The carer’s place in the cancer situation: where does the carer stand in the medical setting? Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2001; 10: 87–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barone AD, Yoels WC and Clair JM. Howphysicians view caregivers: Simmel in the examination room. Sociol Perspect 1999; 42: 673–690. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Institute of Medicine. Retooling for an aging America: building the health care workforce. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2008/Retoolingfor-an-aging-America-Building-the-HealthCare-Workforce.aspx (accessed 11 December 2013). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Levine C Family caregivers and health care professionals working together to improve care. New York, NY: United Hospital Fund, 2013, http://www.uhfnyc.org/publications/880925 (accessed 11 December 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Institute for patient- and family-centered care,http://www.ipfcc.org/ (accessed 11 December 2013)