Abstract

While the efficacy of therapist-guided internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy (iCBT) for anxiety and depression is well-established, a significant proportion of clients show little to no improvement with this approach. Given that motivational interviewing (MI) is found to enhance face-to-face treatment of anxiety, the current trial examined potential benefits of a brief online MI intervention prior to therapist-guided iCBT. Clients applying to transdiagnostic therapist-guided iCBT in routine care were randomly assigned to receive iCBT with (n = 231) or without (n = 249) the online MI pre-treatment. Clients rated motivation at screening and pre-iCBT and anxiety and depression at pre- and post-treatment and at 13- and 25-week follow-up after enrollment. Clients in the MI plus iCBT group made more motivational statements in their emails and were enrolled in the course for a greater number of days compared to clients who received iCBT only, but did not demonstrate higher motivation after completing the MI intervention or have higher course completion. Clients in both groups, at screening and pre-iCBT, reported high levels of motivation. No statistically significant group differences were found in the rate of primary symptom change over time, with both groups reporting large reductions in anxiety and depression pre- to post-treatment (Hedges' g range = 0.96–1.11). During follow-up, clients in the iCBT only group reported additional small reductions in anxiety, whereas clients in the MI plus iCBT group did not. The MI plus iCBT group also showed small increases in depression during follow-up, whereas improvement was sustained for the iCBT only group. It is concluded that online MI does not appear to enhance client outcomes when motivation at pre-treatment is high.

Keywords: Internet-based, Motivational interviewing, Pre-treatment, Cognitive behaviour therapy, Randomized controlled trial

Highlights

-

•

Clinical trial of guided iCBT with and without online motivational interviewing (MI)

-

•

Examined changes between groups in motivation and treatment outcomes

-

•

Adding MI to guided iCBT resulted in more motivational statements and days in treatment

-

•

No group differences in primary symptom or motivation change were found over time.

1. Introduction

Anxiety and depression are prevalent (Pearson et al., 2013) and disabling conditions (Baxter et al., 2014) that can be effectively treated with internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy (iCBT) (Andersson et al., 2019). As there is mounting evidence showing the efficacy of therapist-guided iCBT, attention has shifted towards exploring processes that may further enhance clinical outcomes (Andersson et al., 2019). In face-to-face treatment, motivational interviewing (MI) is an intervention used by therapists to help facilitate clients' intrinsic motivation to change by strengthening client change talk language and resolving ambivalence in an empathetic and collaborative interpersonal environment (Miller and Rollnick, 2013). To enhance clients' motivation to change, therapists typically ask open-ended questions, practice reflective listening, provide affirmative and summary statements, and inform and advise clients (Miller and Rollnick, 2013).

To date, MI has been primarily offered as a brief pre-treatment prior to CBT (Westra, 2012). The argument has been made that MI is a desirable adjunct to CBT because, rather than assuming readiness to change, the approach aims to increase intrinsic motivation to change by evoking and strengthening client change talk (Arkowitz & Westra, 2004). Notably, client motivation, as assessed by self-report measures as well as by qualitatively coding client motivational language in session, is related to CBT outcomes and adherence (e.g., Bados et al., 2007; de Haan et al., 1997; Sijercic et al., 2016; Wergeland et al., 2005). Results from systematic reviews reveal MI enhances CBT response and completion rates for anxiety relative to CBT alone (Ekelund, 2016; Randall and McNeil, 2016).

There has been limited research on MI and iCBT, and research to date has focused exclusively on MI that consists of static open-ended questions. Specifically, Titov et al. (2010) found clients who received online motivational enhancement questions prior to self-guided iCBT for social anxiety were significantly more likely to complete all eight lessons relative to those who did not receive the questions (75% versus 56%), although both groups showed similar improvements on symptoms of social anxiety from pre- to post-treatment. When considering the development of an online MI intervention, research suggests that in addition to text-based open-ended questions, videos and personalized written feedback to clients should be offered to more accurately simulate face-to-face MI (e.g., Alexander et al., 2010; Friederichs et al., 2014; Hester et al., 2005; Osilla et al., 2012). The efficacy of a more interactive online MI intervention prior to therapist-guided iCBT for anxiety and depression remains unknown.

Beck et al. (2020) evaluated the immediate impact of an online MI pre-treatment developed to be more consistent with MI. The authors examined how the online MI intervention immediately impacted motivation to change among two samples, one with previous therapist-guided iCBT experience and one without previous therapist-guided iCBT experience recruited through social media. Results from this pilot study showed that following completion of the MI lesson, both samples of participants reported an immediate statistically significant increase in perceived ability to reduce symptoms and an increase that approached statistical significance in the perceived importance of reducing symptoms. Beck et al. (2020) recommended further rigorous study of whether the lesson would have a direct effect on iCBT outcomes.

1.1. Study purpose and hypotheses

The aim of the current investigation was to examine the efficacy of the online MI pre-treatment in a randomized controlled trial (RCT). Clients applying to transdiagnostic therapist-guided iCBT for anxiety and depression in routine care were randomly assigned to first receive either the online MI pre-treatment or a no pre-treatment waiting period similar in duration. Groups were compared in terms of motivation levels at screening and then just prior to iCBT, symptom improvement on primary and secondary outcomes from pre- to post-iCBT, and at 13 and 25-week follow-up after enrollment, iCBT completion (e.g., lessons accessed by post-treatment) and engagement (e.g., lesson logins), treatment experiences (e.g., course worth time), and motivational language during initial client email correspondence (e.g., change talk statements). It was hypothesized that clients receiving the addition of the online MI pre-treatment lesson would demonstrate greater motivation, completion rates, and engagement, larger symptom improvements at all-time points, improved treatment experience, and more client motivational language as compared to clients receiving iCBT only. As no comparable, brief online MI intervention has been developed for therapist-guided iCBT for anxiety and depression, feedback on clients' experiences with the MI intervention was collected, but no hypotheses were formulated.

2. Method

2.1. Design, ethics and trial registration

The current investigation is a pragmatic RCT designed to examine the efficacy of transdiagnostic iCBT for anxiety and depression with and without online MI offered at pre-treatment. In addition to being randomly assigned to online MI or not, clients were also randomly assigned to one of two treatment settings to reflect the local environment (therapists are employed by the Online Therapy Unit and Community Mental Health Clinics), thus controlling for therapist setting through random assignment. No differences between therapists employed by the iCBT clinic or community mental health clinic were expected as past research has not found meaningful differences between these two groups (Hadjistavropoulos et al., 2016) and all therapists, regardless of setting, had similar training and worked either part or full-time delivering iCBT.

Prior to engaging in iCBT, clients assigned to the MI plus iCBT group participated in a single online MI pre-treatment lesson, whereas clients assigned to the iCBT only group underwent a waiting period of similar duration. The trial received institutional research ethics board approval and was registered in an international trial registry (NCT03684434 at ClinicalTrials.gov). Some changes to the Method section occurred following trial commencement. First, we recruited more participants than initially anticipated as more clients requested treatment during the study period (n = 480 actual versus 300 planning), which ultimately allowed for greater power. Based on the a priori power analysis, 150 clients were needed per group. Technical errors with online measure administration resulted in the Kessler 10-Item Scale (K10; Kessler et al., 2002) only being administered to 59% of the sample at screening, which limited use of this measure in the analyses described below. As delineated in the Method section, coding of motivational language was different than planned to improve quality of coding (e.g., by coding more data).

2.2. Setting, participant recruitment, screening, and randomization

Clients were recruited through the Online Therapy Unit website (www.onlinetherapyuser.ca). The unit is a government-funded clinic that specializes in iCBT. Clients learned about the unit through diverse sources (e.g., physician referrals, word of mouth).

Clients who completed the online screening process between September 27, 2018 and March 1, 2019 were included. The online screening questionnaire assessed whether clients met the following inclusion criteria: (1) 18 years of age or older; (2) residency in Saskatchewan, Canada; (3) experiencing at least mild to moderate symptoms of anxiety and/or depression by scoring ≥5 on the primary measures of anxiety and/or depression (see Section 2.3.2); (4) able to access a secure computer and the internet and comfortable using technology; and (5) willing to provide an emergency medical contact. In addition to eligibility queries, as part of the online screening questions, potential clients also described motivation (e.g., reasons for participating in online therapy), clinical history (e.g., duration of symptoms of anxiety and depression), and past treatment experiences (e.g., use of medication and psychotherapy for anxiety and depression). Following completion of the online screener, a staff member of the Online Therapy Unit contacted potential clients by telephone to further assess exclusion criteria that could not be fully captured online (e.g., suicide risk). Individuals were excluded if they: (1) had been hospitalized within the last year for mental health and/or suicide risk concerns; (2) had high suicide risk; (3) had unmanaged problems with alcohol, drugs, psychosis, or mania; (4) were seeking regular psychological treatment for anxiety and/or depression creating potential for conflicting therapeutic activities (operationalized as > twice a month); (5) would not be present in the province of Saskatchewan during the 8-week treatment period in order to ensure ability of therapists to manage any crises that may arise; and (6) expressed concerns about participating in iCBT.

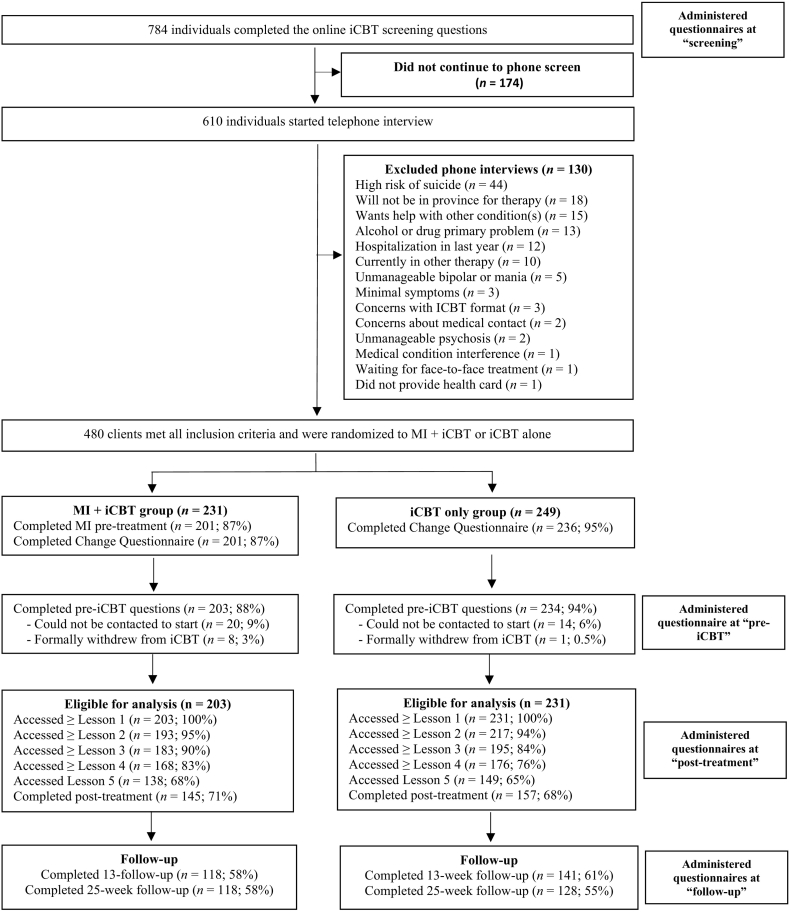

At the end of the telephone interview, eligible clients were provided details about the iCBT course by the screener, and then assigned following simple randomization procedures to one of four treatment groups. As noted above, therapeutic support with the iCBT course was offered from two separate online clinics: therapists situated in the Online Therapy Unit (i.e., “unit”) and therapists situated in a community mental health clinic that specialized in delivering iCBT (i.e., “community”). To facilitate group allocation, a computerised random sequence generator was created by a researcher not affiliated with the study. A sequence of random numbers between 1 and 4 was yielded, where “1” and “2” represented randomization to the MI plus iCBT group delivered by therapists in unit and community, respectively and “3” and “4” represented randomization to the iCBT only group delivered by therapists in the unit and community, respectively. The random sequence of numbers was then imported by the primary investigator into Research Electronic Data Capture (REDcap), a secure web application for building and managing online surveys and databases, including management of randomization, and locked from external manipulation prior to data collection. Eligible clients were subsequently assigned to the next treatment group based on the sequence code. All clients were instructed they would start iCBT two Mondays from the date of the telephone screen, and that they would receive an email on their respective start date with instructions for logging into the iCBT course. Clients assigned to the MI plus iCBT group were additionally informed they would receive a link via email to participate in online MI on the upcoming Saturday, and were encouraged to complete the pre-treatment within one week. See Fig. 1 for participant flow.

Fig. 1.

Client flow chart.

Note. MI = motivational interviewing; iCBT = Internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy.

2.3. Outcomes

When measures below were not completed, one to three automated email reminders were administered along with one to three phone calls carried out by the first author (JS) or a member of the team.

2.3.1. Primary and secondary motivation measures

Primary and secondary measures of motivation were administered at screening and pre-iCBT. Of note, “screening” represents the first point of contact (i.e., baseline) and “pre-iCBT” represents the period following MI but prior to iCBT. The measures were sent to all clients regardless of treatment allocation in an email link through REDcap.

The primary motivation measure was the Change Questionnaire 3-item version (CQ; Miller and Johnson, 2008), in which clients rate their importance, their ability, and their commitment to change in regard to a specific change goal on a 0 (“Definitely not”) to 10 (“Definitely”) scale. In the current study, however, the desired change (i.e., “to reduce the anxiety and/or depression I experience”) was pre-entered in the CQ to ensure consistency across clients. Similar to the original version, the three items were summed to create a total score between 0 and 30, with higher summed scores reflecting greater levels of motivation to reduce symptoms. Past research supports the predictive validity of the CQ (Lombardi et al., 2014), for example, higher motivation scores predict lower post-CBT worry scores. Furthermore, while past research supports the internal consistency of the measure (α = 0.81), in the current study internal consistency of scores on the CQ ranged from α = 0.54 to 0.67.

Two questions developed by Titov et al. (2010) to measure motivation to engage in iCBT were additionally administered as secondary outcome measures of motivation. Specifically, clients rated their motivation to engage in iCBT and their determination to overcome current treatment obstacles using 9-point Likert scales (1 = “Not at all” and 9 = “Extremely”).

In addition to the above-mentioned client motivation measures, clients who received the online MI pre-treatment were asked to complete open- and closed-ended questions to collect feedback about their experiences with the intervention. The client feedback questions were administered immediately following completion of the online MI lesson and were derived from a questionnaire previously used to evaluate the MI lesson (Beck et al., 2020). Using a 1 (“Not at all”) to 5 (“Very much so”) scale, clients rated how much the exercises in the pre-treatment motivated them to learn strategies to reduce anxiety and depression. Following each of the questions, clients had the opportunity to provide written feedback about each exercise in the pre-treatment lesson. Clients subsequently rated the informativeness of the videos in the MI lesson using a 1 (“Not at all”) to 5 (“Extremely”) scale. Lastly, clients were asked to describe what they learned about themselves and to provide suggestions for improving the MI lesson. For the purposes of the current trial, only results from close-ended questions are reported.

2.3.2. Treatment completion and engagement

Treatment completion was measured by examining the percentage of clients who accessed iCBT, as well as the number of lessons accessed by post-treatment. Engagement was assessed by examining the number of emails sent to and from the therapist, the number of logins to the web application, and the number of days in the course from first to last login.

2.3.3. Symptom outcome measures

Primary symptom measures were administered at screening, prior to lessons 1 to 5, at post-treatment, and at 13 and 25-week follow-up after enrollment. Secondary symptom measures were similarly obtained at all periods but not prior to lessons 2 to 5. Measures administered at screening and at 13 and 25-weeks were delivered through REDCap, whereas measures administered prior to lessons 1 to 5 and at post-treatment were delivered through the Online Therapy Unit web platform, allowing therapists to use the information to actively monitor client progress and risk.

Primary symptom measures used to assess the impact of online MI on iCBT outcomes consisted of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7; Spitzer et al., 2006) and the Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al., 2001).

The GAD-7 is a self-report measure assessing anxiety severity over the past 2 weeks using seven items rated on a scale from 0 to 3 that results in a total score ranging from 0 to 21. A score of 10 or greater on the GAD-7 is suggestive of a likely diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder (Spitzer et al., 2006). In the current study, internal consistency for scores on the GAD-7 ranged from α = 0.87 to 0.91.

The PHQ-9 is a validated self-report measure of depression severity over a 2-week period using nine items rated on a scale from 0 to 3 that result in a total score ranging from 0 to 27. A cut-off score between 8 and 11 on the PHQ-9 is suggestive of a depressive disorder (Manea et al., 2012). Internal consistency for scores on the PHQ-9 in the current trial ranged from α = 0.84 to 0.90.

Secondary measures used to evaluate the effect of online MI on iCBT outcomes included the K10 and the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS; Sheehan, 1983).

The K10 is a self-report measure of psychological distress over the past month using 10 items rated on a scale from 1 to 5 that results in a total score ranging from 10 to 50. In the current trial, internal consistency for scores on the K10 ranged from α = 0.86 to 0.92.

The SDS is a brief 3-item self-report measure of functional impairment in the areas of work/school, social life, and home life or family responsibilities, with each item rated on a scale from 0 to 10 that results in a total score ranging from 0 to 30. Internal consistency for scores on the SDS in the current study ranged from α = 0.79 to 0.93.

2.3.4. Treatment experience

Consistent with past research (Hadjistavropoulos et al., 2017), clients regardless of treatment allocation answered a series of questions post-iCBT about their experiences with the course. Specifically, clients were asked to indicate with a “yes” or “no” response whether they felt confident recommending the treatment to a friend and whether completing the course was worth their time.

2.3.5. Client email coding

Client emails to their therapist during the first two weeks of iCBT were qualitatively examined for motivational language for and against change and resistant behaviours.

All messages between therapist and client were first de-identified by an independent staff member in the Online Therapy Unit, and then imported into NVivo 12, a qualitative coding software. Drawing on past literature in the face-to-face field and review of the messages, the Adapted Client Resistance Code (Sijercic et al., 2016) and the Motivational Interviewing Skill Code Version 2.1 (MISC; Miller et al., 2008) were broadly used to derive a coding guide to identify resistant behaviours as well as change (e.g., “I am willing to make a change”) and sustain talk statements (e.g., “I am not able to make a change”) online. Of note, resistance was defined in the current trial as when a client expressed disagreement with their therapist in their email correspondence. Consistent with past literature (Sijercic et al., 2016), an attempt was made to further code sustain talk into oppositional or ambivalent statements; however, due to difficulties with identifying these statements in emails, sustain talk statements were not further coded into different types. After the coding guide was developed and to remain consistent with previous approaches to coding client communication online (e.g., Soucy et al., 2018), the primary investigator (JS) and a different staff member jointly coded six independent client email correspondences from a previous therapist-guided iCBT trial to become familiar with the coding guide. The two researchers then independently coded a random sample of 10% of the data (n = 43 emails) to establish inter-rater reliability for the main dataset. Strong agreement was found (Cohen's Kappa = 0.83), and the coders resolved any discrepancies that arose when coding. The primary investigator (JS) then coded the remaining data according to the coding guide. Following coding, the frequency of each category of statements were calculated using a query function in NVivo and the word count for each email was calculated and summed for a total score per client. Of note, the coders were not therapists in the current trial and were blind to therapist identity and client condition.

2.4. Interventions

2.4.1. The Wellbeing Course

All clients received the same therapist-guided iCBT course, namely the Wellbeing Course, which was developed by the eCentreClinic at Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia. The Wellbeing Course is an 8-week transdiagnostic therapist-guided iCBT program for anxiety and depression that consists of five online lessons, including: information about the cognitive behavioural model and symptom identification (lesson 1), thought monitoring and challenging (lesson 2), de-arousal strategies and pleasant activity scheduling (lesson 3), graded exposure (lesson 4), and relapse prevention (lesson 5) (e.g., Dear et al., 2015; Dear et al., 2016; Fogliati et al., 2016; Titov et al., 2013; Titov et al., 2014; Titov et al., 2015). Each lesson consists of a slideshow presentation and downloadable information with written text, visual images, client stories and suggested activities to facilitate learning. Additional resources are available throughout the course, and pertain to various topics (e.g., assertiveness, communication skills, structured problem solving). Clients gain access to each lesson on a pre-determined schedule, such that lessons 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 were available at the beginning of weeks 2, 3, 5, 6, and 8 after enrollment. For the current trial, the Wellbeing Course was coupled with weekly secure asynchronous emails, in which the therapist answered client questions, provided support and feedback on symptom change, encouraged treatment adherence and use of skills, helped implement skills, highlighted treatment progress and practice of skills, and clarified administrative procedures (Hadjistavropoulos et al., 2016). Telephone contact only occurred if the client reported significant increases in symptoms since last contact (e.g., suicidal ideations), had not logged into the program over the past week, or requested telephone contact to receive additional support.

2.4.2. The Planning for Change lesson

Prior to the Wellbeing Course, clients assigned to the MI plus iCBT group first received access to the Planning for Change lesson (version 2), an online MI pre-treatment developed by team members at the Online Therapy Unit for the purposes of the current trial. The lesson aims to increase clients' intrinsic motivation to participate in iCBT, and contains three videos (i.e., introduction, expert, and conclusion) and five interactive online MI exercises (i.e., values clarification, importance ruler, looking back, confidence ruler, looking forward). To remain consistent with the principles that underlie MI and the skills used in this approach, the exercises include open-ended questions and reflective style written feedback statements, and the videos included information in an attempt to demonstrate compassion and acceptance. The lesson was designed using a positive, supportive, and empathetic style of language without pressure, and gave clients choice by seeking permission before providing information. The pre-treatment MI intervention was developed over a 4-month period, and in consultation with a counsellor who specializes in the dissemination of MI.

2.5. Data preparation and statistical analyses

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 26 was used to conduct all statistical analyses. Prior to hypothesis testing, independent samples t-tests were used to test for possible group differences in demographic and clinical variables at screening that were continuous in nature (e.g., age), while Pearson chi-square tests were used to test for possible group differences in similar variables at screening that were categorical in nature (e.g., ethnicity). The alpha level of significance for these preliminary analyses was adjusted from 0.05 to 0.01 in an attempt to help control for the large number of analyses conducted. As illustrated in Table 1, no statistically significant group differences were observed, thus indicating equivalence between groups at screening.

Table 1.

Screening demographic and clinical characteristics by group.

| Variable | All sample (N = 434) |

MI + iCBT group (n = 203) |

iCBT only group (n = 231) |

Statistical significance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Demographic characteristics | |||||||

| Age | |||||||

| Mean (SD) | 37.67 (12.91) | – | 37.80 (12.98) | – | 37.55 (12.88) | – | t(432) = 0.20, p = 0.84 |

| Range | 18–76 | – | 18–75 | – | 18–76 | – | |

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | 325 | 74.9 | 153 | 75.4 | 172 | 74.5 | χ2 (1) = 0.05, p = 0.83 |

| Male | 109 | 25.1 | 50 | 24.6 | 59 | 25.5 | |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Caucasian | 390 | 89.8 | 180 | 88.7 | 210 | 90.9 | χ2 (2) = 1.33, p = 0.51 |

| Metis | 16 | 3.7 | 7 | 3.4 | 9 | 3.9 | |

| Other | 28 | 6.5 | 16 | 7.9 | 12 | 5.2 | |

| Location | |||||||

| Large city (>200,000) | 183 | 42.2 | 87 | 42.9 | 96 | 41.6 | χ2 (4) = 4.97, p = 0.29 |

| Small city (10,000−200,000) | 109 | 25.1 | 54 | 26.6 | 55 | 23.8 | |

| Town or village (<10,000) | 96 | 22.1 | 47 | 23.2 | 49 | 21.2 | |

| Farm | 40 | 9.2 | 14 | 6.9 | 26 | 11.2 | |

| Reserve | 6 | 1.4 | 1 | 0.4 | 5 | 2.2 | |

| Relationship status | |||||||

| Married | 200 | 46.1 | 101 | 49.8 | 99 | 42.9 | χ2 (4) = 4.80, p = 0.31 |

| Single | 118 | 27.2 | 54 | 26.6 | 64 | 27.7 | |

| Living with partner | 70 | 16.1 | 25 | 12.3 | 45 | 19.4 | |

| Separated or divorced | 40 | 9.2 | 20 | 9.9 | 20 | 8.6 | |

| Widowed | 6 | 1.4 | 3 | 1.4 | 3 | 1.4 | |

| Living arrangements | |||||||

| Living with family | 310 | 71.4 | 149 | 73.4 | 161 | 69.7 | χ2 (3) = 5.02, p = 0.17 |

| Living alone | 63 | 14.5 | 32 | 15.8 | 31 | 13.4 | |

| Living with roommate | 29 | 6.7 | 8 | 3.9 | 21 | 9.1 | |

| Other | 32 | 7.4 | 14 | 6.9 | 18 | 7.8 | |

| Education | |||||||

| College certificate/diploma | 132 | 30.4 | 62 | 30.5 | 70 | 30.3 | χ2 (5) = 4.29, p = 0.51 |

| Undergraduate degree | 103 | 23.7 | 53 | 26.1 | 50 | 21.6 | |

| High school diploma | 90 | 20.7 | 38 | 18.7 | 52 | 22.5 | |

| Some university | 52 | 12.0 | 28 | 13.8 | 24 | 10.4 | |

| Graduate/professional degree | 45 | 10.4 | 17 | 8.4 | 28 | 12.1 | |

| Less than high school | 12 | 2.8 | 5 | 2.5 | 7 | 3.1 | |

| Clinical characteristics | |||||||

| Screening GAD-7 scores | 12.39 (5.17) | – | 12.52 (4.98) | – | 12.28 (5.34) | – | t(432) = 0.48, p = 0.63 |

| Screening PHQ-9 scores | 13.11 (5.66) | – | 13.33 (5.54) | – | 12.92 (5.76) | – | t(432) = 0.77, p = 0.44 |

| Screening K10 scores | 29.08 (6.95) | – | 29.22 (6.85) | – | 28.95 (7.07) | – | t(249) = 0.30, p = 0.77 |

| Screening SDS scores | 19.48 (6.69) | – | 19.50 (6.45) | – | 19.47 (6.90) | – | t(432) = 0.04, p = 0.97 |

| Screening GAD-7 ≥ 10 | 287 | 66.1 | 139 | 68.5 | 148 | 64.1 | χ2 (1) = 0.94, p = 0.33 |

| Screening PHQ-9 ≥ 10 | 308 | 70.9 | 152 | 74.9 | 156 | 67.5 | χ2 (1) = 2.83, p = 0.09 |

| Medication for mental health | |||||||

| Lifetime - yes | 322 | 74.2 | 153 | 75.4 | 169 | 73.2 | χ2 (1) = 2.75, p = 0.60 |

| <3 months - yes | 254 | 58.5 | 124 | 61.1 | 130 | 56.3 | χ2 (1) = 0.82, p = 0.37 |

| Current mental health treatment | |||||||

| Yes | 206 | 47.7 | 98 | 48.3 | 108 | 46.8 | χ2 (1) = 1.00, p = 0.75 |

| Current provider(s)a | |||||||

| Family doctor - yes | 148 | 34.1 | 70 | 34.5 | 78 | 33.8 | χ2 (1) = 0.03, p = 0.88 |

| Psychiatrist - yes | 63 | 14.5 | 27 | 13.3 | 36 | 15.6 | χ2 (1) = 0.45, p = 0.50 |

| iCBT interesta | |||||||

| Convenience | 235 | 54.1 | 119 | 58.6 | 116 | 50.2 | χ2 (1) = 3.07, p = 0.08 |

| Prefer self-management | 231 | 53.2 | 111 | 54.7 | 120 | 51.9 | χ2 (1) = 0.32, p = 0.57 |

| Heard about and wanted to try | 178 | 41.0 | 84 | 41.4 | 94 | 40.7 | χ2 (1) = 0.02, p = 0.89 |

| ICBT was recommended | 135 | 31.1 | 64 | 31.5 | 71 | 30.7 | χ2 (1) = 0.03, p = 0.86 |

| Financial difficulties | 130 | 30.0 | 65 | 32.0 | 65 | 28.1 | χ2 (1) = 0.78, p = 0.38 |

| Symptoms make accessing face-to-face treatment difficult | 100 | 23.0 | 47 | 23.2 | 53 | 22.9 | χ2 (1) = 0.00, p = 0.96 |

| Time constraints | 96 | 22.1 | 53 | 26.1 | 43 | 18.6 | χ2 (1) = 3.52, p = 0.06 |

| Perception about changing | |||||||

| Nothing needs to be worked on | 3 | 0.7 | 2 | 1.0 | 1 | 0.4 | χ2 (5) = 7.78, p = 0.17 |

| Might be time to make a change | 120 | 27.6 | 50 | 24.6 | 70 | 30.3 | |

| There are things I can change | 145 | 33.4 | 67 | 33.0 | 78 | 33.8 | |

| Making some changes right now | 36 | 8.3 | 13 | 6.4 | 23 | 10.0 | |

| Made a change/trying to keep well | 75 | 17.3 | 44 | 21.7 | 31 | 13.4 | |

| Made progress but fallen back | 55 | 12.7 | 27 | 13.3 | 28 | 12.1 | |

Clients selected all statements that applied; alpha level of significance <0.01 in an attempt to help control for the large number of analyses conducted; screening scores reported for non-imputed data; MI = motivational interviewing; iCBT = Internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy; GAD-7 = Generalized Anxiety Disorder – 7 items; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire – 9 items; K10 = Kessler 10-Item Scale; SDS = Sheehan Disability Scale.

A multiple imputation procedure was used to replace missing data as this approach has been shown to generate more precise estimates of the treatment effect when handling missing values in randomized clinical trials (Armijo-Olivo et al., 2009). Among the 434 clients who received iCBT, 30% (n = 132) of primary outcome data was missing at post-treatment, 40% (n = 175) was missing at 13-week follow-up, and 43% (n = 188) was missing at 25-week follow-up. As recommended in the literature (e.g., Karin et al., 2018a; Karin et al., 2021; Little et al., 2012), analysis of missing cases as a function of demographic and clinical variables were explored to identify potential patterns of systematic missingness and non-completion of assessments. Results revealed that lesson completion was the single dominant predictor of missing data at post-treatment (Wald's χ2 = 122.35, p < 0.001, Nagelkerke R Square = 69.9%) and at 25-week follow-up (Wald's χ2 = 99.53, p < 0.001, Nagelkerke R Square = 37.4%), suggesting that multiple imputation would be appropriate for handling missing cases after missing values were substituted with adjusted scores based on clients' lesson completion (Karin et al., 2018a, Karin et al., 2018b; Karin et al., 2021). Specific analyses included pooled estimates from five imputations, with significance testing within each model denoted with ppooled.

To examine changes in primary and secondary outcomes across groups and over time, a series of Generalized Estimation Equation (GEE) analyses were performed. An increasingly popular approach to testing longitudinal data in iCBT trials (e.g., Hadjistavropoulos et al., 2016; Hadjistavropoulos et al., 2017), GEE is a modeling technique that examines change in the dependent variable, over time and within each group, while also controlling for within subject variance (e.g., Hubbard et al., 2010; Karin et al., 2018b). In the current investigation, unstructured working correlations were selected in the GEE models along with gamma distributions and log link response scales to address skewness within the dependent variables. To compare outcomes of iCBT with and without MI, GEE analyses examined change from screening to pre-treatment for the motivation outcomes (i.e., motivation to engage in iCBT questions) and change from pre- to post-iCBT and from pre-iCBT to 25-week-follow-up for the clinical outcomes (i.e., symptom outcomes). For the GEE models performed for the aforementioned primary and secondary symptom measures, client motivation scores at screening were respectively included as a model covariate.

Both groups had similar symptom scores at the first point of contact (i.e., screening; see Table 1) as well as when starting iCBT approximately two weeks later (i.e., pre-treatment; see Table 2). Given that symptom scores are generally higher at screening than at pre-treatment (e.g., Hedman et al., 2013; Hedman et al., 2014; Lutz et al., 2017), a more conservative approach involves starting to assess the outcome of treatment at pre-treatment rather than at screening. If we used symptom scores starting at screening, we risk inflating the overall effect. In our analyses, we were interested in how MI impacted outcomes of iCBT, which was best represented by exploring outcomes from pre- to post-treatment.

Table 2.

Means, standard deviations, and effect sizes for outcomes by group.

| Estimated marginal means |

Percentage changes from pre-ICBT |

Within-group effect sizes from pre-iCBT |

Between-group effect sizes |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening | Post-MI | Pre-ICBT | Post-ICBT | 13-week follow-up | 25-week follow-up | To post | To 6-month follow-up | To post | To 25-week follow-up | At post | At 25-week follow-up | |

| Primary outcomes | ||||||||||||

| CQ | ||||||||||||

| MI + iCBT | 25.44 (3.95) | 25.62 (3.64) | – | – | – | – | −1 [−3/1] | – | −0.05 [−0.1/0] | – | −0.06 [0/0.1] | – |

| iCBT only | 25.59 (3.72) | 25.82 (3.74) | – | – | – | – | −1 [−3/1] | – | −0.06 [−0.1/0] | – | ||

| GAD-7 | ||||||||||||

| MI + iCBT | – | – | 11.74 (5.12) | 6.26 (4.78) | 6.25 (4.57) | 6.42 (4.74) | 47 [38/55] | 45 [38/53] | 1.11 [1/1.2] | 1.08 [1/1.2] | −0.01 [−0.1/0.1] | −0.21 [−0.3/0.1] |

| iCBT only | – | – | 11.17 (5.22) | 6.22 (5.05) | 5.81 (4.66) | 5.44 (4.43) | 44 [37/51] | 51 [42/61] | 0.96 [0.9/1] | 1.18 [1.1/1.3] | ||

| PHQ-9 | ||||||||||||

| MI + iCBT | – | – | 12.10 (5.83) | 6.61 (5.21) | 7.28 (5.14) | 7.60 (5.26) | 45 [37/54] | 37 [29/46] | 0.99 [0.9/1.1] | 0.81 [0.7/0.9] | −0.05 [−0.1/0] | −0.20 [−0.3/0.1] |

| ICBT only | – | – | 11.56 (5.70) | 6.33 (5.19) | 6.35 (5.20) | 6.56 (5.20) | 45 [35/56] | 43 [30/56] | 0.96 [0.9/1] | 0.92 [0.8/1] | ||

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||||||||

| Motivation questions | ||||||||||||

| MI + iCBT | 15.81 (2.27) | 16.19 (2.24) | – | – | – | – | −3 [−5/−1] | – | −0.17[−0.3/−0.1] | – | 0.02 [−0.1/0.1] | – |

| iCBT only | 16.13 (2.23) | 16.24 (2.25) | – | – | – | – | −1 [−3/1] | – | −0.05 [−0.1/0] | – | ||

| K10 | ||||||||||||

| MI + iCBT | – | – | 28.06 (7.66) | 21.91 (7.84) | 21.33 (7.14) | 22.12 (7.55) | 22 [17/27] | 21 [17/26] | 0.79 [0.7/0.9] | 0.78 [0.7/0.9] | −0.07 [−0.2/0] | −0.13 [−0.2/0] |

| iCBT only | – | – | 27.37 (7.89) | 21.36 (7.95) | 20.64 (7.55) | 21.13 (7.91) | 22 [16/28] | 23 [15/31] | 0.76 [0.7/0.8] | 0.79 [0.7/0.9] | ||

| SDS | ||||||||||||

| MI + iCBT | – | – | 17.60 (8.02) | 12.01 (8.07) | 11.00 (8.00) | 11.41 (8.34) | 32 [22/41] | 35 [26/44] | 0.69 [0.6/0.8] | 0.76 [0.7/0.8] | −0.09 [−0.2/0] | −0.24 [−0.3/−0.2] |

| iCBT only | – | – | 16.57 (8.67) | 11.27 (8.38) | 9.46 (7.70) | 9.47 (7.99) | 32 [23/41] | 43 [23/62] | 0.62 [0.5/0.7] | 0.85 [0.8/0.9] | ||

Note. MI = motivational interviewing; iCBT = Internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy; CQ = Change Questionnaire; GAD-7 = Generalized Anxiety Disorder – 7 items; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire – 9 items; K10 = Kessler 10-Item Scale; SDS = Sheehan Disability Scale.

The estimated marginal means derived from the GEE models were used to calculate the average percentage change across time and group for each of the outcome measures. Based on the estimated marginal means, corresponding Hedges' g effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals were also calculated for the within- and between-group effects.

To test for possible group differences on treatment completion and experience with iCBT, a series of Pearson chi-square tests were performed. Additionally, to test for possible group differences on iCBT engagement and motivational language and resistant behaviours, a series of independent samples t-tests were executed. Variables analyzed using independent samples t-tests were examined in terms of outliers and normality of distributions. Common procedures recommended in the literature were used when such procedures were found to improve the data (Field, 2013; Tabachnick and Fidell, 2001). Log transformation was used for lesson login, logarithm transformations were used for email word count and change talk statements, and square root transformation was used for emails sent to therapists. The distribution could not be normalized for the number of lessons accessed, emails received from the therapist, and the duration of time enrolled and, therefore, a bootstrapping method (with 1000 samples) was applied to these parametric tests. Standardized scores for detecting statistically significant outliers were then examined for all variables (Tabachnick and Fidell, 2001). While no adjustments were required for the transformed variables, variables that could not be transformed had statistically significant outliers that could only be partially corrected by altering extreme scores (Tabachnick and Fidell, 2001). Given that bootstrapping is an appropriate technique to help further correct for significant outliers in a distribution (Field, 2013), the outstanding extreme scores were not deemed problematic. Of note, no transformations or adjustment of outliers were attempted on the variable sustain talk statements. Approximately 99% of the sample either expressed or did not express a sustain talk statement. As suggested by Field (2013), all levels of the dependent variable were therefore collapsed to create a binary variable, such that clients either did (coded as “1”) or did not (coded as “0”) express at least one sustain talk statement.

Further, sub-analyses were conducted to explore whether results were moderated by age and symptom severity at screening, but were not significant (see Supplementary material). Consideration was given to conducting sub-analyses to explore if motivation level moderated outcomes, but due to the lack of variability in the distribution of scores for the CQ and motivation questions no such analyses were performed. Only five clients scored below the mid-point on the CQ and only two clients scored below the mid-point on the motivation questions.

3. Results

3.1. Background characteristics

Background characteristics of each group are reported in Table 1. Clients had a mean age of 37.67 (SD = 12.91) years, 90% (n = 390) were Caucasian, 75% (n = 325) were female, and 42% (n = 183) lived in a large urban area. The majority were using psychotropic medication (n = 254; 59%), with 71% (n = 308) having PHQ-9 ≥ 10 suggestive of a depressive disorder and 66% (n = 287) scoring ≥10 on the GAD-7 suggestive of an anxiety disorder. Approximately half the sample noted convenience (n = 235; 54%) and preference for self-management (n = 231; 53%) contributed to their decision to seek iCBT. Most clients endorsed statements indicating readiness to change, such as “it might be time to make some changes” (n = 120; 28%) or “I know there are things I could change” (n = 145; 33%). There were no statistically significant differences found between groups.

3.2. Online MI adherence and feedback

The majority of clients assigned to the MI plus iCBT group started (n = 207/231; 90%) and completed the MI lesson (n = 201/231; 87%) as well as the lesson feedback questionnaire (n = 198/231; 86%). The majority of the sample (n = 153; 77%) completed the lesson in one day, with an average completion time of 87.17 min (SD = 144.63). For the remaining 23% (n = 48) of the sample, the MI lesson took between 2 and 6.09 days. On average, client ratings suggested each of the five exercises in the lesson motivated them at least to a degree for learning strategies to improve their mental wellbeing (M range: 3.71–4.22) and that each of the three videos were informative (M range: 4.24–4.29).

3.3. Intervention use and completion rates

Intervention use and completion rates by group are reported in Table 3. The only significant finding identified was that clients in the MI plus iCBT group spent more days enrolled in iCBT (M = 61.08; SD = 28.88) relative to clients in the iCBT only group (M = 54.42; SD = 25.64; t(432) = 2.54, p = 0.01). On average, both groups showed a similar number of treatment logins (M = 19.42; SD = 11.56), emails sent to (M = 3.49; SD = 2.83) and from therapist (M = 8.77; SD = 1.49), accessed lessons (M = 4.29; SD = 1.20), and treatment completion rates (79% ≥ 4 lesson; 66% 5 lesson completion).

Table 3.

Treatment engagement, completion, and satisfaction by group.

| Variable | All sample (N = 434) |

MI + iCBT group (n = 203) |

iCBT only group (n = 231) |

Statistical significance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Engagement | |||||||

| Mean number of course logins | 19.42 (11.56) | – | 20.69 (12.79) | – | 18.29 (10.25) | – | t(432) = 1.92, p = 0.06 |

| Mean days between first and last login | 58.09 (29.28) | – | 61.08 (28.88) | – | 54.42 (25.64) | – | t(432) = 2.54, p < 0.01 |

| Mean number of messages sent to therapist | 3.49 (2.83) | 3.56 (3.01) | 3.43 (2.66) | – | t(432) = 0.15, p = 0.88 | ||

| Mean number of messages received from therapist | 8.77 (1.49) | – | 8.75 (1.42) | – | 8.78 (1.56) | – | t(432) = −0.21, p = 0.81 |

| Completion | |||||||

| Mean number of lessons accessed at post-treatment | 4.29 (1.20) | – | 4.35 (1.13) | – | 4.23 (1.26) | – | t(432) = 1.12, p = 0.23 |

| Accessed ≥4 lessons at post-treatment | 344 | 79% | 168 | 83% | 176 | 76% | χ2 (1) = 2.84, p = 0.09 |

| Accessed 5 lessons at post-treatment | 287 | 66% | 138 | 68% | 149 | 65% | χ2 (1) = 0.58, p = 0.45 |

| Satisfactiona | |||||||

| Recommend course to others | 276 | 97% | 135 | 98% | 141 | 97% | χ2 (1) = 4.10, p = 0.52 |

| Course worth their time | 277 | 98% | 133 | 96% | 144 | 99% | χ2 (1) = 1.50, p = 0.22 |

Note. MI = motivational interviewing; iCBT = Internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy. While independent samples t-tests were primarily performed on transformed dependent variables, means and standard deviations are reported for non-transformed data in order to facilitate interpretation of results.

Analyses were performed on subsample of clients who completed the treatment satisfaction questions (n = 284).

3.4. Motivation measures

As delineated in Table 2, the GEE analyses revealed no statistically significant Time by Group interactions for the CQ (ppooled = 0.40) or motivation to engage in iCBT questions (ppooled = 0.21). Specifically, motivation levels across groups were high at screening for both groups, and the MI lesson did not further enhance motivation (see Table 2).

3.5. Symptom measures

After controlling for motivation levels at screening, the GEE analyses revealed no statistically significant Time by Group interactions for the GAD-7 (ppooled = 0.37), PHQ-9 (ppooled = 0.30), and K10 (ppooled = 0.10), indicating that the addition of MI to iCBT did not result in further symptom reductions over time. However, there was a statistically significant Time by Group interaction for the SDS (ppooled = 0.02), with clients assigned to the iCBT only group, compared to the MI plus iCBT group, reporting greater reductions in disability over time (see Table 2).

3.6. Percentage improvements and effect sizes

Findings related to percentage improvements and effect sizes are reported in Table 2. Significant percentage improvements were observed from pre- to post-iCBT on the primary and secondary symptom measures for both the MI plus iCBT (range: 45%–47% and 22%–32%, respectively) and iCBT only groups (range: 44%–45% and 22%–32%, respectively), with no statistically significant between-group differences at post-treatment (g range: −0.01/−0.09). From pre- to post-iCBT, large within-group effect sizes were observed for both groups on primary symptom measures (g range: 0.96/1.11) and medium within-group effect sizes were observed for both groups on secondary symptom measures (g range: 0.62/0.79). Gains were generally maintained at follow-up, with medium to large within-group effect sizes reported from pre-iCBT to 6-month follow-up for both the MI plus iCBT group (g range: 0.78/1.08) and iCBT only group (g range: 0.79/1.18). While there was no between-group effect size on the K10 at 6-month follow-up, small group effect sizes were observed for the GAD-7, PHQ-9, and SDS at this time point, in favour of the iCBT only group. Specifically, for the GAD-7 and SDS, clients in the iCBT only group experienced some additional symptom reductions at 6-month follow-up, whereas clients in the MI plus iCBT group maintained, but did not make additional gains. In the case of the PHQ-9, the MI plus iCBT group experienced a minor increase in symptoms of depression at 6-month follow-up, whereas gains were maintained for clients in the iCBT only group.

3.7. Client motivational language

Table 4 presents data pertaining to client motivational language and resistant behaviours. Of note, there were no resistant behaviours identified in client emails. In terms of client motivational language, there was a small yet statistically significant group difference in the number of change talk statements expressed, t(305) = 2.01, p < 0.05, with clients in the MI plus iCBT group (M = 2.65; SD = 2.29) expressing statistically significantly more change talk statements than clients in the iCBT only group (M = 2.25; SD = 2.57). However, the same proportion of clients in the MI plus iCBT group (n = 7; 5%) were found to express at least one sustain talk statement as clients in the iCBT only group (n = 7; 4%). Across groups, the number of change talk statements ranged from 0 to 13; whereas, the majority of clients across groups did not express even one sustain talk statement. Furthermore, the percentage of clients in each group who sent at least one email to their therapist in the first two weeks of iCBT was similar (n = 307; 71%) as was the number of words in these emails (M = 317.92 words; SD = 359.18 words). An example of a change talk statement in the current study included comments about one's need (e.g., “I need to take better care of myself”), whereas an example of a sustain talk statement included comments about the challenges of one's ability to change (e.g., “Some days it feels like I can't change my mindset at all”).

Table 4.

Motivational language by group among clients who sent at least one email during first two weeks of iCBT.

| Variable | All sample who sent at least one email (N = 307) |

MI + iCBT group who sent at least one email (n = 141) |

iCBT only group who sent at least one email (n = 166) |

Statistical significance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Mean number of change talk | 2.43 (2.45) | – | 2.65 (2.29) | – | 2.25 (2.57) | – | t(305) = 2.01, p < 0.05 |

| Range of change talk statements | 0–13 | 0–13 | 0–13 | – | |||

| Expressed at least one sustain talk | 14 | 5% | 7 | 5% | 7 | 4% | χ2 (1) = 0.10, p = 0.75 |

| Mean number of resistant behaviours | 0 | – | 0 | – | 0 | – | – |

| Mean word count | 317.92 (359.18) | – | 337.35 (360.00) | – | 301.42 (358.75) | – | t(305) = 0.60, p = 0.55 |

Note. MI = motivational interviewing; iCBT = Internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy.

3.8. Treatment experiences with iCBT

Table 3 presents data on treatment satisfaction. Out of the clients who completed the treatment satisfaction questions at post-treatment (68% in the MI plus iCBT group and 63% in the MI only group), most clients across groups indicated that they would recommend the course to a friend (n = 276; 97%) and that the course was worth their time (n = 277; 98%).

4. Discussion

The current investigation examined the efficacy of a newly developed online MI pre-treatment, the Planning for Change lesson for enhancing engagement and outcomes of therapist-guided iCBT. It was hypothesized that online MI plus iCBT would be superior to iCBT alone in terms of client motivation as well as treatment engagement and outcomes.

Contrary to hypotheses, while clients who completed online MI were enrolled in the iCBT course for a longer period, there were no other statistically significant differences between the groups. Unexpectedly, clients in the iCBT only group appeared to fare better at follow-up in terms of anxiety severity and perceived disability than clients in the MI plus ICBT group. Of note, lack of differences was observed even though there was at least some partial evidence to suggest that MI had the intended impact; specifically, clients provided online MI expressed statistically significantly more change talk statements during initial email correspondence in iCBT than clients who were not provided online MI. Nevertheless, however, the frequency of sustain talk statements did not differ between groups and were generally infrequently expressed, with 95% of all clients not articulating any sustain talk statements. Overall, completion and engagement rates obtained in the current study were comparable to other trials of iCBT for anxiety and depression delivered in a similar environment (Hadjistavropoulos et al., 2021).

On average in the current study, clients reported high motivation to engage in iCBT at screening. The argument could therefore be made that there was less opportunity for improvement, and that the lesson could have been more valuable had client motivation been lower. Lack of differences between groups was unexpected for several reasons. First, the online MI used in this study was designed to be more interactive and engaging than a previous internet-delivered MI intervention that showed potential for improving completion rates among individuals seeking self-guided iCBT for social anxiety (Titov et al., 2010). Second, Beck et al. (2020) had recently piloted the online MI intervention used in the current investigation, and found the online MI lesson had an immediate statistically significant increase on clients' perceived ability to change. Importantly, the self-reported motivation of participants in Beck et al.'s study prior to the online intervention was lower relative to clients in the current trial. The findings highlight that online MI may enhance immediate motivation, particularly perceived ability to change, if motivation is lower. However, when motivation to engage in iCBT is higher, evidence for the effectiveness of online MI was not found.

In hindsight, the online MI intervention may have been more effective if offered to a select group of clients or perhaps during treatment. Arkowitz and Miller (2008) argue that MI is not essential, and perhaps even counterproductive, for clients who are actively ready to change. For example, Rohsenow et al. (2004) found clients with higher motivation to recover reported a greater number of cocaine and alcohol use days from post-treatment to 1-year follow-up when initially provided online motivational enhancement therapy compared to meditation relaxation training. For clients who are further along in the change process, Hettema et al. (2005) recommend that MI only be incorporated into treatment when active signs of ambivalence or resistance are identified. Extrapolating from this research, online MI may have worked better if it was reserved for specific times throughout treatment when clients exhibit signs of low motivation (e.g., not logging in, expressing ambivalence in emails). As there is initial support that an integrated approach to delivering MI and CBT for generalized anxiety disorder is more favourable (Westra et al., 2016), another strategy that may have resulted in improved outcomes in the current trial was if therapists had more actively used information from the MI lesson when delivering iCBT. Moreover, as Titov et al. (2010) found that using online MI prior to self-guided iCBT resulted in improved completion rates, the argument could also be made that greater benefits may have been observed in the current trial had clients also not been provided therapist contact during treatment. It is possible that our therapists, unbeknownst to us, were actually providing MI in both conditions throughout iCBT (e.g., engaging in reflective listening when calling clients who did not log into treatment).

Taken together, client motivation coupled with the level of therapist support and timing of MI throughout treatment are important factors to consider moving forward with research in this area. As delineated by the efficiency model of support, therapeutic help in an online context is speculated to be most beneficial when it addresses failure points pertaining to usability, engagement, fit, knowledge, or implementation (Schueller et al., 2017). In order for a client to experience meaningful change from an online intervention, Schueller et al. (2017) postulate the technology must be usable, the individual must engage with the treatment in an effective manner, and the individual must also appropriately integrate the techniques and skills into daily practice. As such, in the case of clients who are motivated and in receipt of therapist-guided iCBT, pre-treatment online MI seems unnecessary. As described by Schueller et al. (2017), too much therapeutic contact has the risk of lowering client confidence, decreasing personal autonomy, or reducing motivation. By not addressing ambivalence in therapy when motivation is not an issue, it affords the opportunity to focus therapeutic support on other possible failure points that may hinder treatment efficacy (e.g., helping a client correctly use a skill). It would be beneficial in the future to examine the integration of online MI and therapist support throughout treatment to help increase the ability of those clients with greater ambivalence to effectively engage in iCBT and optimize their outcomes.

4.1. Limitations

Several study limitations should be acknowledged. Foremost, there was limited variability in motivation scores obtained in the current trial, with most clients reporting high levels of motivation. It is possible that among those few clients with lower motivation, a one lesson intervention may not have been powerful enough to address these clients' ambivalence. The short-version of the CQ was also found to have poor to acceptable internal consistency over the two time points assessed. It may therefore have been preferable to use the full CQ or an alternatively psychometrically sound measure to fully capture the construct of motivation and allow for improved comparisons between studies. Further, clients typically respond to the original CQ by identifying a specific change goal; however, the measure was adapted in the current study to assess clients' motivation to engage in iCBT and, thus, the psychometric properties of this version are unknown. As acknowledged above, it is also possible that therapists in the current study were incorporating MI throughout treatment when emailing or telephoning their clients weekly. Also, of note, there was missing data from 30% of clients at post-treatment and 43% of clients at 25-week follow-up. Given that imputed data does not replicate client data with complete accuracy, the generalizability of the current findings concerning symptom change is reduced. It is encouraging to note the percent of missing data is comparable to other iCBT studies (e.g., Ruwaard et al., 2012; Wootton et al., 2019). Lastly, as no diagnostic assessment was included in the screening phase, the generalizability of the findings is limited to clients who are experiencing comparable symptom severity.

4.2. Future directions

As MI may be more beneficial for some individuals than others, it would be valuable to expand the sample scope by assessing whether online MI yields more promising results when targeted at clients with lower motivation. In the future, providing online MI to those individuals who do not follow through with booking the telephone interview or those clients who fail to login to the iCBT course or complete lessons warrants exploration. It will also be beneficial to examine if outcomes vary when online MI is coupled with a self-versus therapist-guided course among clients with varying levels of motivation.

4.3. Conclusions

Partial support for the utility of the pre-treatment Planning for Change lesson was obtained in the current trial as online MI was found to be associated with clients expressing a somewhat greater number of change talk statements and enrolling in iCBT for a longer duration. Yet these improvements did not translate to enhanced treatment response or completion rates. While these statistically significant group differences were small, it is important to acknowledge that more clinically meaningful changes may have been observed under different conditions. Thus, moving forward, it will be important to determine if specific client populations benefit more from online MI or if certain methods or timelines of offering MI help maximize client outcomes.

Funding

This research was supported by funding provided by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research awarded to Joelle Soucy (Frederick Banting and Charles Best Canada Graduate Scholarship Doctoral Award) and Heather Hadjistavropoulos (reference number 152917). Additionally, the Online Therapy Unit is funded by the Saskatchewan Ministry of Health. Funders had no involvement in the study design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data. N.T. and B.F.D. are funded by the Australian Government to operate the national MindSpot Clinic.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that appear to have influenced the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the clients, community advisors, screeners, therapists, research staff, research associates, students, and web developers associated with the Online Therapy Unit at the University of Regina, including therapists from the Saskatchewan Health Authority who also deliver the therapy. We would specifically like to acknowledge Cynthia Beck for her contribution in the development of the online MI intervention and Marcie Nugent for her contribution in study setup.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2021.100394.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

References

- Alexander G.L., McClure J.B., Calvi J.H., Divine G.W., Stopponi M.A., Rolnick S.J., Johnson C. A randomized clinical trial evaluating online interventions to improve fruit and vegetable consumption. Am. Publ. Health Assoc. 2010;100:319–326. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.154468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G., Carlbring P., Titov N., Lindefors N. Internet interventions for adults with anxiety and mood disorders: a narrative umbrella review of recent meta-analyses. Can. J. Psychiatr. 2019;64:465–470. doi: 10.1177/0706743719839381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arkowitz H., Miller W.R. Learning, applying, and extending motivational interviewing. In: Arkowitz H., Westra H.A., Miller W.R., Rollnick S., editors. Applications of Motivational Interviewing. Motivational Interviewing in the Treatment of Psychological Problems. The Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Arkowitz H., Westra H.A. Integrating motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioral therapy in the treatment of depression and anxiety. J. Cogn. Psychother. 2004;18:337–350. [Google Scholar]

- Armijo-Olivo S., Warren S., Magee D. Intention to treat analysis, compliance, dropouts and how to deal with missing data in clinical research: a review. Phys. Ther. Rev. 2009;14:36–49. doi: 10.1179/174328809X405928. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bados A., Balaguer G., Saldaña C. The efficacy of cognitive–behavioral therapy and the problem of drop-out. J. Clin. Psychol. 2007;63:585–592. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter A.J., Vos T., Scott K.M., Ferrari A.J., Whitehead H.A. The global burden of anxiety disorders in 2010. Psychol. Med. 2014;44:1–12. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713003243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck C.D., Soucy J.N., Hadjistavropoulos H.D. Mixed-method evaluation of an online motivational intervention as a pre-treatment to Internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy: immediate benefits and user feedback. Internet Interv. 2020;20 doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2020.100311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dear B.F., Staples L.G., Terides M.D., Karin E., Zou J., Johnston L., Titov N. Transdiagnostic versus disorder-specific and clinician-guided versus self-guided internet-delivered treatment for generalized anxiety disorder and comorbid disorders: a randomized controlled trial. J. Anxiety Disord. 2015;36:63–77. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dear B.F., Staples L.G., Terides M.D., Fogliati V.J., Sheehan J., Johnston L., Titov N. Transdiagnostic versus disorder-specific and clinician-guided versus self-guided internet-delivered treatment for social anxiety disorder and comorbid disorders: a randomized controlled trial. J. Anxiety Disord. 2016;42:30–44. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.05.004. (PMID: 27261562) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekelund S.M. University of Bergen; Bergen, Norway: 2016. Motivational Interviewing and Cognitive-Behaviour Therapy in the Treatment of Anxiety Disorders: A Systematic Review. (unpublished master’s thesis) [Google Scholar]

- Field A. 4th ed. Sage; London: 2013. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Fogliati V.J., Dear B.F., Staples L.G., Terides M.D., Sheehan J., Johnston L., Titov N. Disorder-specific versus transdiagnostic and clinician-guided versus self-guided internet-delivered treatment for panic disorder and comorbid disorders: a randomized controlled trial. J. Anxiety Disord. 2016;39:88–102. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.03.005. (PMID: 27003376) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friederichs S.A.H., Oenema A., Bolman C., Guyaux J., van Keulen H.M., Lechner L. I Move: systematic development of a web-based computer tailored physical activity intervention, based on motivational interviewing and self-determination theory. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:212. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Haan E., van Oppen P., van Balkon A.J.L.M., Spinhoven P., Hoogduin K.A.L., van Dyck R. Prediction of outcome and early vs. late improvement in OCD patients treated with cognitive behaviour therapy and pharmacotherapy. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1997;96:354–361. doi: 10.1111/j.16000447.1997.tb09929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadjistavropoulos H.D., Nugent M., Alberts N., Staples L., Dear B., Titov N. Transdiagnostic Internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy in Canada: an open trial comparing results of a specialized online clinic and nonspecialized community clinics. J. Anxiety Disord. 2016;42:19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadjistavropoulos H.D., Schneider L.H., Edmonds M., Karin E., Nugent M.N., Dirkse D., Dear B., Titov N. Randomized controlled trial of Internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy comparing standard weekly versus optional weekly therapist support. J. Anxiety Disord. 2017;52:15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2017.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadjistavropoulos H.D., Peynenburg V., Thiessen D.L., Nugent M., Karin E., Staples L., Titov N. Utilization, patient characteristics, and longitudinal improvements among patients from a provincially funded transdiagnostic internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy program: observational study of trends over 6 years. Can. J. Psychiatry. 2021 doi: 10.1177/07067437211006873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedman E., Ljótsson B., Rück C., Bergström J., Andersson G., Kaldo V.…Lindefors N. Effectiveness of Internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy for panic disorder in routine psychiatric care. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2013;128:457–467. doi: 10.1111/acps.12079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedman E., Lekander M., Ljótsson B., Lindefors N., Rück C., Hofmann S.G., Schulz S.M. Sudden gains in Internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy for severe heath anxiety. Behav. Res. Ther. 2014;54:22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2013.12.00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hester R.K., Squires D.D., Delaney H.D. The drinker’s check-up: 12-month outcomes of a controlled clinical trial of a stand-alone software program for problem drinkers. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2005;28:159–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettema J., Steele J., Miller W.R. Motivational interviewing. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2005;1:91–111. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard A.E., Ahern J., Fleischer N.L., Van der Laan M., Lippman S.A., Jewell N., Bruckner T., Satariano W.A. To GEE or not to GEE: comparing population average and mixed models for estimating the associations between neighborhood risk factors and health. Epidemiology. 2010;21:467–474. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181caeb90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin E., Dear B.F., Heller G.Z., Crane M.F., Titov N. “Wish you were here”: examining characteristics, outcomes, and statistical solutions for missing cases in web-based psychotherapeutic trials. J. Med. Internet Res. Mental Health. 2018;5:e22. doi: 10.2196/mental.8363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin E., Dear B.F., Heller G.Z., Gandy M., Titov N. Measurement of symptom change following web-based psychotherapy: statistical characteristics and analytical methods for measuring and interpreting change. J. Med. Internet Res. Mental Mealth. 2018;5:e10200. doi: 10.2196/10200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin E., Crane M.F., Dear B.F., Nielssen O., Heller G.Z., Kayrouz R., Titov N. Predictors, outcomes, and statistical solutions of missing cases in web-based psychotherapy: methodological replication and elaboration study. J. Med. Internet Res. Mental Health. 2021;8:e22700. doi: 10.2196/22700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R.C., Andrews G., Colpe L.J., Hiripi E., Mroczek D.K., Normand S.L.…Zaslavsky A.M. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol. Med. 2002;32:959–976. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little R.J., D'Agostino R., Cohen M.L., Dickersin K., Emerson S.S., Farrar J.T.…Stern H. The prevention and treatment of missing data in clinical trials. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;367:1355–1360. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1203730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi D.R., Button M., Westra H.A. Measuring motivation: change talk and counter-change talk in cognitive behavioral therapy for generalized anxiety. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2014;43:12–21. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2013.846400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz W., Arndt A., Rubel J., Berger T., Schröder J., Späth C.…Fuhr K. Defining and predicting patterns of early response in a web-based intervention for depression. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017;19 doi: 10.2196/jmir.7367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manea L., Gilbody S., McMillan D. Optimal cut-off score for diagnosing depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): a meta-analysis. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2012;184:191–196. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.110829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller W.R., Johnson W.R. A natural language screening measure for motivation to change. Addict. Behav. 2008;33:1177–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller W., Rollnick S. 3rd ed. The Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2013. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. [Google Scholar]

- Miller W.R., Moyers T.B., Ernst D., Amrhein P. Manual for the Motivational Interviewing Skill Code (MISC) Version 2.1. 2008. https://casaa.unm.edu/download/misc.pdf Retrieved from.

- Osilla K.C., D’Amico E.J., Díaz-Fuentes C.M., Phil M., Lara M., Watkins K. Multicultural web–based motivational interviewing for clients with a first-time DUI offense. Cult. Divers. Ethnic Minor. Psychol. 2012;18:192–202. doi: 10.1037/a0027751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson C., Janz T., Ali J. Health at a Glance. 2013. Mental and substance use disorders in Canada (Catalogue no. 82-624-X) pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Randall C.L., McNeil D.W. Motivational interviewing as an adjunct to cognitive behavior therapy for anxiety disorders: a critical review of the literature. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2016;24:296–311. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2016.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohsenow D.J., Monti P.M., Martin R.A., Colby S.M., Myers M.G., Gulliver S.B.…Abrams D.B. Motivational enhancement and coping skills training for cocaine abusers: effects on substance use outcomes. Addiction. 2004;99:862–874. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruwaard J., Lange A., Schrieken B., Dolan C.V., Emmelkamp P. The effectiveness of online cognitive behavioral treatment in routine clinical practice. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schueller S.M., Tomasino K.N., Mohr D.C. Integrating human support into behavioral intervention technologies: the efficiency model of support. Clin. Psychol. Scie. Pract. 2017;24:27–45. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan D.V. Charles Scribner and Sons; New York, NY: 1983. The Anxiety Disease. [Google Scholar]

- Sijercic I., Button M.L., Westra H.A., Hara K.M. The interpersonal context of client motivational language in cognitive behavioural therapy. Psychotherapy. 2016;53:13–21. doi: 10.1037/pst0000017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soucy J.N., Hadjistavropoulos H.D., Couture C.A., Owens V.A.M., Dear B., Titov N. 2018. Content of Client E-mails in Internet-delivered Cognitive Behaviour Therapy: Comparability Across Trials and Relationship to Client Outcome. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer R.L., Kroenke K., Williams J.B.W., Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006;166:1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick B.G., Fidell L.S. 4th ed. Allyn and Bacon; Boston, MA: 2001. Using Multivariate Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Titov N., Andrews G., Schwencke G., Robinson E., Peters L., Spence J. Randomized controlled trial of Internet cognitive behavioural treatment for social phobia with and without motivational enhancement strategies. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 2010;44:938–945. doi: 10.3109/00048674.2010.49385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titov N., Dear B.F., Johnston L., Lorian C., Zou J., Wootton B., Rapee R.M. Improving adherence and clinical outcomes in self-guided internet treatment for anxiety and depression: randomised controlled trial. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titov N., Dear B.F., Johnston L., McEvoy P., Wootton B., Terides M.D., Rapee R. Improving adherence and clinical outcomes in self-guided internet treatment for anxiety and depression: a 12-month follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titov N., Dear B., Staples L., Terides M.D., Karin E., Sheehan J., McEvoy P.M. Disorder-specific versus transdiagnostic and clinician-guided versus self-guided treatment for major depressive disorder and comorbid anxiety disorders: a randomized controlled trial. J. Anxiety Disord. 2015;35:88–102. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wergeland G.J.O., Fjermestad K.W., Marin C.E., Haugland B.S.M., Silvermand W.K., Öst L.G., Havik O.E., Heiervang E.R. Predictors of dropout from community clinic child CBT for anxiety disorders. J. Anxiety Disord. 2005;31:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westra H. The Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2012. Motivational Interviewing in the Treatment of Anxiety. [Google Scholar]

- Westra H.A., Constantino M.J., Antony M.M. Integrating motivational interviewing with cognitive-behavioral therapy for severe generalized anxiety disorder: an allegiance-controlled randomized clinical trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2016;84:768–782. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wootton B.M., Karin E., Titov N., Dear B.D. Self-guided internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy (ICBT) for obsessive-compulsive symptoms: a randomized controlled trial. J. Anxiety Disord. 2019;66 doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2019.102111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material