Abstract

Background

Patient perspectives in cardiovascular diseases (CVD) are significantly associated with clinical outcomes.

Methods and Results

Among 100 patients who responded to a telephone survey in a university hospital setting in Tokyo during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, 20% reported depressive symptoms and 33% were hesitant to contact medical staff in the event of CVD exacerbation. Interestingly, the frequency of depressive symptoms was maintained even after a decline in the number of newly COVID-19-infected patients.

Conclusions

Our telemedicine practices revealed the magnitude of our patients’ mental health conditions and their hesitation to contact medical facilities in the event of CVD exacerbation.

Key Words: Cardiovascular disease, Coronavirus disease (COVID-19), Telemedicine

With the outbreak of the novel coronavirus COVID-19 pandemic, a need for remote patient visits has emerged and various telemedicine modalities have been implemented.1 In Japan, a state of emergency was declared on April 6, 2020, and some restrictions were imposed that affected patients’ ability to access health services. Therefore, to decrease the risk of COVID-19 infection, medical institutions such as ours launched telemedicine services (teleconsultations) for patients with stable cardiovascular diseases (CVD). However, several concerns have been raised regarding telemedicine consultations. First, the COVID-19 pandemic has imposed emotional stress even on non-COVID patients (e.g., anxiety and depression)2 and, second, there are concerns regarding some patients’ behavior in response to potential or actual worsening of CVD symptoms. Previous studies reported that these patients tended to avoid hospital visits even in true medical emergencies.3–6 Because of these issues, the American Heart Association recommended that medical providers emphasize the importance of calling for help as soon as possible in the event of a CVD emergency.7

Despite these challenges, there have been few investigations of patients’ perspectives regarding these concerns. The aim of this report was to determine the perspectives of patients with stable CVD regarding their mental health and actions in response to worsening CVD symptoms. Furthermore, we also aimed to determine the effects of individual patient characteristics on these perspectives.

Methods

The study population consisted of outpatients with stable CVD who responded to a voluntary telephone-based questionnaire after a remote medical visit in a university hospital setting in Tokyo for the duration of the state of emergency (from April 6 to May 25, 2020). Among the 103 patients who answered the telephone-based survey, 3 were excluded because they could not complete the questionnaire or had missing data. Consequently, 100 patients completed the questionnaire.

Patients’ mental status (e.g., depressive mood) was evaluated using the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) screening tool.8,9 It has been recommended that patients scoring ≥3 on the PHQ-2 should be further assessed for depressive and anxiety symptoms.10 To assess patients’ behavior towards a hypothetical exacerbation of disease, the patients were asked, “Do you feel any hesitation to contact medical staff when your heart’s condition worsens?” Patients were also asked about their living status (e.g., the number of people in their household) and occupation. “Unemployed” patients were defined as those taking a leave of absence from work, those who identified themselves as housewives or househusbands, and those without jobs or who were retired.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as the mean±SD and categorical variables are expressed as percentages. Differences in the frequency of depression and hesitation to contact medical staff between 7-day moving averages ≥100 and <100 newly COVID-19-infected patients were compared using Pearson’s Chi-squared tests. Logistic regression analysis was used to identify predictors associated with depressive symptoms and a hesitation to arrange a clinical consultation.

Ethical Considerations

All patients provided informed consent to participate. The study protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board Committee of Keio University (2020–0164).

Results

Table 1 shows the demographic data of the study participants. In all, 100 patients (59% male, mean age 69±11 years) were analyzed in this study. Among these patients, 54.0% had hypertension, 42.0% had dyslipidemia, and 44.0% had atrial fibrillation.

Table 1.

Patients’ Baseline Characteristics (n=100)

| Demographics and medical history | |

| Age (years) | 69.2±11.3 |

| Male sex | 59 (59.0) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.5±3.8 |

| Smoker | 33 (33.0) |

| Living alone | 18 (18.0) |

| Living with elderly (>60 years) | 60 (60.0) |

| Unemployed | 56 (56.0) |

| Current drinker | 53 (53.0) |

| Hypertension | 54 (54.0) |

| Diabetes | 25 (25.0) |

| Dyslipidemia | 42 (42.0) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 44 (44.0) |

| COPD | 2 (2.0) |

| Stroke | 7 (7.0) |

| Valvular heart disease | 13 (13.0) |

| History of cancer | 19 (19.0) |

| Previous history of PCI | 16 (16.0) |

| Previous history of CABG | 3 (3.0) |

| Previous history of MI | 9 (9.0) |

| Previous heart failure admission | 12 (12.0) |

| Peripheral artery disease | 1 (1.0) |

| Laboratory data at the last outpatient clinic | |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) | 104.0 [76.0–132.0] |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 56.5 [46.0–69.0] |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 98.0 [75.0–122.5] |

| Cr (mg/dL) | 0.92 [0.73–1.09] |

| BNP (pg/mL) | 41.8 [15.3–99.4] |

| Medication | |

| Antiplatelet | 28 (28.0) |

| Anticoagulant | 42 (42.0) |

| Loop diuretics | 17 (17.0) |

| β-blockers | 62 (62.0) |

| RAS inhibitors | 42 (42.0) |

| MRA | 10 (10.0) |

| Statin | 42 (42.0) |

| Allopurinol or febuxostat | 14 (14.0) |

Data are shown as the mean±SD, median [interquartile range], or number (percentage). BMI, body mass index; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; Cr, creatinine; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; MI, myocardial infarction; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; RAS, renin-angiotensin system.

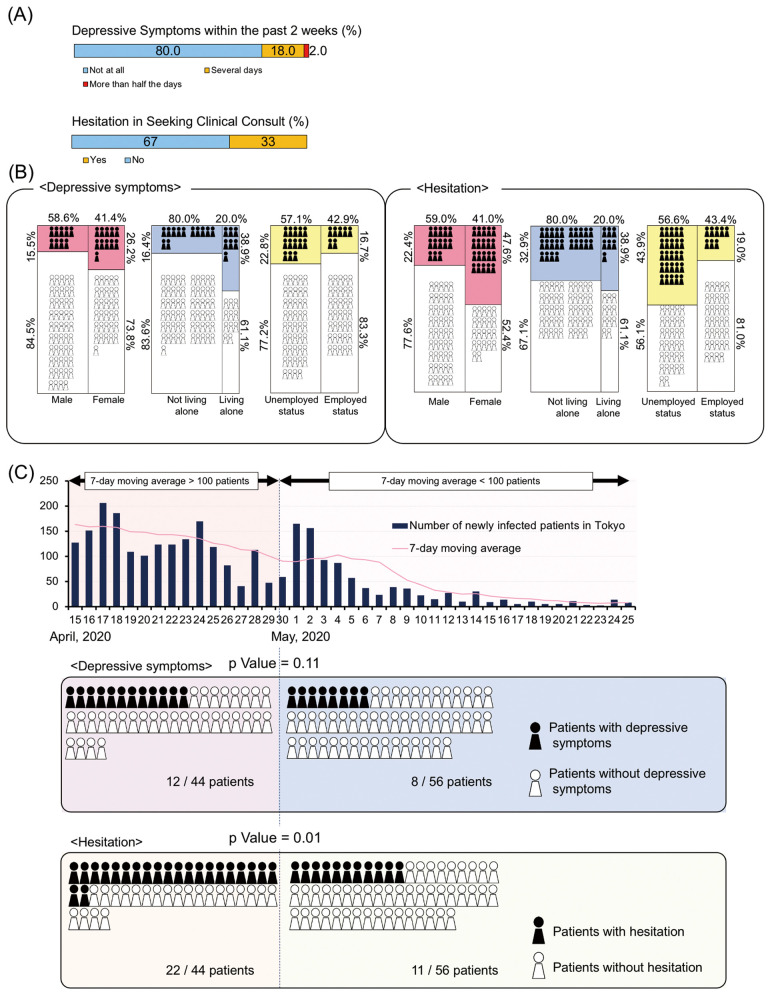

Of the 100 patients, 20% reported mental health concerns, with 18% experiencing depressive symptoms for several days over the past 2 weeks and 2% experiencing depressive symptoms for more than half of those days (Figure A). Living alone was an independent predictor of depressive symptoms (odds ratio [OR] 3.18; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.03–9.87; P=0.045; Table 2A; Figure B). The number of patients with depressive symptoms was not related to the number of newly infected patients (Figure C).

Figure.

Patients’ perspectives regarding remote medical visits during the COVID-19 pandemic. (A) Frequency of experiencing depressive symptoms within the past 2 weeks and hesitation to seek a medical consultation in a hypothetical situation of worsening cardiovascular disease (CVD). (B) Detailed proportion of patients with depressive symptoms and those hesitating to seek medical consultations according to sex, living alone, and employment status. (C) Association between patients hesitating to seek medical consultations and the number of newly COVID-19-infected patients in Tokyo.

Table 2.

Factors Associated With Depressive Symptoms (A) and Hesitation to Seek a Clinical Consultation (B)

| OR | 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (A) | |||

| Age | 0.99 | 0.95–1.03 | 0.675 |

| Female sex | 0.50 | 0.19–1.35 | 0.172 |

| BMI | 1.00 | 0.88–1.15 | 0.965 |

| Living alone | 3.18 | 1.03–9.87 | 0.045 |

| Living with elderly (>60 years) | 0.42 | 0.15–1.20 | 0.106 |

| Unemployed | 1.51 | 0.54–4.20 | 0.428 |

| Hypertension | 0.84 | 0.31–2.24 | 0.723 |

| Diabetes | 0.29 | 0.06–1.35 | 0.113 |

| Dyslipidemia | 1.55 | 0.58–4.15 | 0.385 |

| Previous PCI | 0.99 | 0.25–3.89 | 0.983 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 0.80 | 0.29–2.16 | 0.655 |

| Cancer | 0.70 | 0.18–2.67 | 0.596 |

| (B) | |||

| Age | 1.02 | 0.98–1.06 | 0.414 |

| Female sex | 2.79 | 1.20–6.52 | 0.018 |

| BMI | 0.99 | 0.90–1.12 | 0.986 |

| Living alone | 1.29 | 0.41–3.47 | 0.741 |

| Living with elderly (>60 years) | 0.83 | 0.33–2.10 | 0.697 |

| Unemployed | 3.27 | 1.33–8.08 | 0.010 |

| Hypertension | 1.02 | 0.45–2.32 | 0.966 |

| Diabetes | 0.65 | 0.24–1.76 | 0.399 |

| Dyslipidemia | 0.61 | 0.26–1.43 | 0.253 |

| Previous PCI | 1.14 | 0.38–3.44 | 0.819 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 0.24 | 0.09–0.60 | 0.002 |

| Cancer | 1.46 | 0.52–4.04 | 0.472 |

BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Notably, 33% of patients hesitated contacting medical staff in the event of their disease worsening; female sex (OR 2.79; 95% CI 1.20–6.52; P=0.018) and being unemployed (OR 3.27; 95% CI 1.33–8.08 P=0.010) were also associated with hesitating to seek a clinical consultation (Table 2B; Figure B). The frequency of hesitating to contact medical staff decreased after the number of newly infected patients declined (50% vs. 20% for ≥100 vs. <100 newly COVID-19-infected patients, respectively; Figure C).

Discussion

A hesitation to contact medical facilities at the time of disease exacerbation was common in patients with stable CVD. The number of newly infected patients per day was related to the number of patients hesitating to contact medical staff, and a fear of contracting the disease in hospital is the likely major cause of such hesitation. Early and urgent intervention in emergency CVD exacerbation is of paramount importance in managing the disease. It is recommended that patients with CVD, especially women and the unemployed, are instructed to seek medical help in the case of emergencies. Some of the patients in cardiovascular clinics also reported mental health concerns, independent of the number of newly infected patients. Our findings indicate that cohabiting with others is an important protective factor against the development of depression caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. During the epidemic phase of COVID-19, there was a warning regarding the potential for a substantial increase in feelings of loneliness. Digital technologies are a necessary intervention to bridge the social distance and to lessen loneliness in socially isolated patients.11 The findings of the present study suggest that, even when there is a decline in the number of infected patients, cardiologists should pay attention to their patients’ mental health, especially those patients who are living alone.

The present study has some limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the present study was a small-scale study conducted in a single center; consequently, the statistical power may not have been sufficient to detect reliable outcomes. Second, because the study was a voluntary telephone-based survey, an implicit bias was inevitable. Further larger-scale explorations with more robust methodology are called for. Despite these limitations, this study revealed patients’ perspectives during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the findings may have clinical implications as to the form that telemedicine interventions should take.

Conclusions

The present telephone-based survey during the COVID-19 pandemic indicated the effect of the pandemic on our patients’ mental health and their hesitation to contact medical facilities in the event of CVD exacerbation. Given that there has been a resurgence in COVID-19 in many areas12,13 and pandemics are long lasting,14 medical providers need to consider the appropriate approaches to perform telemedicine, including assessing patients’ mental status and instructing patients as to the importance of contacting medical staff in the case of a CVD emergency.

Acknowledgments / Competing Interests / Sources of Funding

None.

Disclosures

S.K., M.S. are members of Circulation Reports’ Editorial Team. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

IRB Information

The study protocol was approved by the Keio University Institutional Review Board Committee (2020–0164).

Data Availability

The deidentified participant data will not be shared.

References

- 1. Berwick DM.. Choices for the “new normal”. JAMA 2020; 323: 2125–2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yao H, Chen JH, Xu YF.. Patients with mental health disorders in the COVID-19 epidemic. Lancet Psychiatry 2020; 7: e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Natarajan MK, Wijeysundera HC, Oakes G, Cantor WJ, Miner SES, Welsford M, et al.. Early observations during the COVID-19 pandemic in cardiac catheterization procedures for ST-elevation myocardial infarction across Ontario. CJC Open 2020; 2: 678–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Garcia S, Albaghdadi MS, Meraj PM, Schmidt C, Garberich R, Jaffer FA, et al.. Reduction in ST-segment elevation cardiac catheterization laboratory activations in the United States during COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020; 75: 2871–2872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mafham MM, Spata E, Goldacre R, Gair D, Curnow P, Bray M, et al.. COVID-19 pandemic and admission rates for and management of acute coronary syndromes in England. Lancet 2020; 396: 381–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Solomon MD, McNulty EJ, Rana JS, Leong TK, Lee C, Sung SH, et al.. The COVID-19 pandemic and the incidence of acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2020; 383: 691–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. American Heart Association’s Mission: Lifeline and Get With The Guidelines Coronary Artery Disease Advisory Work Group and the Council on Clinical Cardiology’s Committees on Acute Cardiac Care and General Cardiology and Interventional Cardiovascular Care.. Temporary emergency guidance to STEMI systems of care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Circulation 2020; 142: 199–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW.. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: Validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care 2003; 11: 1284–1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Muramatsu K, Miyaoka H, Kamijima K, Muramatsu Y, Tanaka Y, Hosaka M, et al.. Performance of the Japanese version of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (J-PHQ-9) for depression in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2018; 52: 64–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhang WR, Wang K, Yin L, Zhao WF, Xue Q, Peng M, et al.. Mental health and psychosocial problems of medical health workers during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Psychother Psychosom 2020; 89: 242–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Galea S, Merchant RM, Lurie N.. The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing: The need for prevention and early intervention. JAMA Intern Med 2020; 180: 817–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shimizu K, Wharton G, Sakamoto H, Mossialos E.. Resurgence of COVID-19 in Japan. BMJ 2020; 370: m3221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vahidy FS, Drews AL, Masud FN, Schwartz RL, Askary BB, Boom ML, et al.. Characteristics and outcomes of COVID-19 patients during initial peak and resurgence in the Houston metropolitan area. JAMA 2020; 324: 998–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kissler SM, Tedijanto C, Goldstein E, Grad YH, Lipsitch M.. Projecting the transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 through the postpandemic period. Science 2020; 368: 860–868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The deidentified participant data will not be shared.