Abstract

Conjunctival congestion has been reported as the most common ophthalmic manifestation of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, affecting 18.4%-31.6% of patients with corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Orbital inflammatory disease has been rarely reported in association with COVID-19 infection, with only 2 case reports of adolescent patients having been recently published. We present a unique case of orbital myositis in a 10-year-old boy who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection in the absence of typical systemic COVID-19 manifestations. Although it is uncertain whether SARS-CoV-2 infection triggered the inflammation or was coincidental, the possible association of the events is concerning.

Case Report

A 10-year-old, previously healthy boy presented to ophthalmology clinic at Benha University for a 5-day history of left progressive periorbital dull-ache swelling. Additionally, he had drooping of his upper eyelid, binocular horizontal diplopia on left gaze, painful eye movement, redness of the eye, low-grade fever, occasional nausea, and vomiting. His mother reported contact 3 week prior to presentation with asymptomatic individuals who were seropositive for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The patient denied symptoms of cough, shortness of breath, or general malaise. He was afebrile at presentation (37.5° C).

On examination, best-corrected visual acuity was 20/20 in the right eye and 20/20 in the left eye. No afferent pupillary defect was observed. Intraocular pressure was 14 mm Hg in each eye. There was a moderate left periorbital edema, erythema, mild left ptosis of 2 mm, and a subtle down-in dystopia (Figure 1 A), with moderately limited left eye elevation and abduction (Figure 1B). Mild left-sided proptosis was noted on Hertel exophthalmometry (right eye, 16 mm; left eye, 18 mm) and on Nafziger testing (in which the lid of the proptotic eye is seen first when examining from above tangentially over the forehead). Neither palpable masses nor resistance to retropulsion were found. Slit-lamp examination revealed mild sectorial chemosis and injection over the left lateral rectus muscle, with no conjunctival discharge. Fundus examination was unremarkable bilaterally, with no evidence of optic nerve head swelling. Head and neck examination did not show any lymphadenopathy.

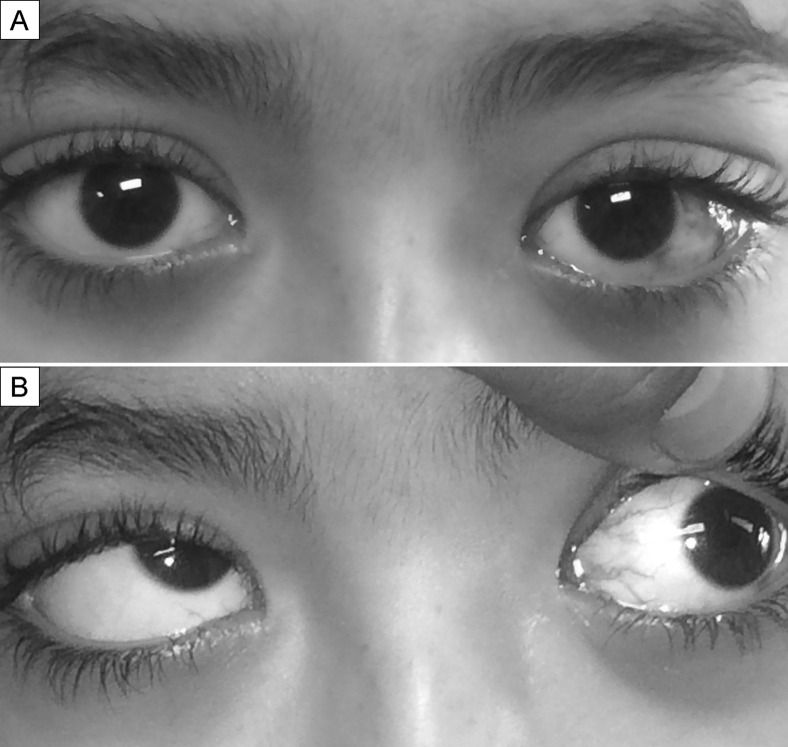

Fig 1.

A, External photography showing left-sided upper lid fullness, proptosis (wider palpebral fissure), and conjunctival hyperemia over the left lateral rectus muscle. B, External photograph showing limited abduction and elevation of the left eye.

Orbital magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed significant enlargement of the left lateral rectus muscle, involving its belly and tendinous insertions, as well as the ipsilateral lacrimal gland, with mild stranding of the surrounding intraorbital fat and consequent proptosis (Figure 2 ).

Fig 2.

T2-weighted orbital magnetic resonance imaging showing left-sided proptosis, significant enlargement of left lateral rectus muscle (black arrow) and lacrimal gland (white arrow) with mild stranding of the surrounding intraorbital fat.

Laboratory analysis showed an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (56 mm/h), positive C-reactive protein level, and positive nasopharyngeal swab reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) tests for SARS-CoV-2. The complete blood cell count results, fasting and postprandial blood glucose levels, thyroid-stimulating hormone level, antinuclear antibody level, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody level, rheumatoid factor level, QuantiFERON TB-Gold test, urine analysis, computed tomography chest, MRI, and magnetic resonance venography of the brain were normal (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Summary of laboratory and imaging findings

| Test | Result |

|---|---|

| ESR | 56 mm in 1st hour |

| CRP | Positive |

| Reverse-transcriptase PCR for SARS-CoV-2 (nasopharyngeal swab) | Positive |

| Complete blood cell count | Normal |

| Blood glucose levels | |

| Fasting | 79 mg/dL |

| Postprandial (2 hours) | 117 mg/dL |

| Thyroid-stimulating hormone level | 2.1 mIU/L |

| Antinuclear antibody level | Negative |

| Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody | Negative |

| Rheumatoid factor | Negative |

| QuantiFERON TB-Gold test | Negative |

| Urine analysis | Normal |

| Computed tomography (chest) | No abnormality detected |

| MRI and MR venography of the brain | No abnormality detected |

CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; TB, tuberculosis.

Based on the positive RT-PCR test for SARS-CoV-2, home isolation for 2 weeks was advised, and a 5-day oral therapy with azithromycin (AZT) 200 mg/5 ml suspension (5 ml once daily) was started. AZT was prescribed for potential bacterial superinfection and for reducing SARS-CoV-2 viral load and spread.1 For the presumed orbital myositis with the lack of clinical or radiological evidence of infectious orbital cellulitis, oral prednisone (1 mg/kg/day) for 2 weeks was prescribed. Dramatic improvement was noticed 2 days after initiating the steroid regimen. At the 1-month follow-up examination, clinical features and proptosis had resolved completely. Oral prednisone therapy was tapered by 10 mg weekly. Repeated orbital MRI 14 days after initiation of therapy revealed resolution of the swelling of the left lateral rectus muscle and lacrimal gland.

Discussion

Although the exact etiology of orbital myositis is unknown, a variety of autoimmune, infective, drug-related, and paraneoplastic conditions have been temporally linked to its pathogenesis.2 Several autoimmune disorders have been associated with orbital myositis, including granulomatosis with polyangiitis, systemic lupus erythematous, and rheumatoid arthritis.2 It has also been reported in cysticercosis, herpes zoster ophthalmicus, Whipple disease, and Lyme disease.2 Several ophthalmic manifestations have been associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection, including dry eye, conjunctival congestion, acute abducens nerve palsy, optic neuropathy, and multiple cranial nerve palsies.3, 4, 5

Three cases of orbital inflammation in the context of SARS-CoV-2 infection have been reported.6 , 7 Turbin and colleagues6 reported 2 adolescent patients presenting with unilateral orbital cellulitis, sinusitis, and radiographic intracranial abnormalities with relatively mild systemic manifestations. SARS-CoV-2 samples were positive confirming COVID-19 infection. They hypothesized that SARS-CoV-2 infection resulted in congested upper respiratory tract and compromised mucociliary clearance, leading to secondary bacterial infection with subsequent orbital cellulitis with intracranial extension. Diaz and colleagues7 reported a 22-year-old man patient who presented with unilateral acute dacryoadenitis, which was complicated by partial ophthalmoplegia and orbital inflammation despite oral antibiotic therapy and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications. The patient improved rapidly a few days after oral steroid therapy was initiated. Their patient did not have systemic manifestations of COVID-19 infection, and PCR test was negative; however, he tested positive for IgM/IgG SARS-CoV-2 antibodies.

In both reports and in our patient, systemic COVID-19 symptoms were either absent or mild. In our patient, there was evidence of lateral rectus myositis, enlarged lacrimal gland, and signs of orbital inflammation. It is unclear whether SARS-CoV-2 infection triggered the orbital inflammation or was coincidental. Immunohistological studies would have been required to discriminate between direct viral infiltration and a sterile immunological process. We speculate that viral particles may have entered to ocular tissues from respiratory droplets, blood spread of the virus via the lacrimal gland,8 or from the nasopharynx. It is also possible that SARS-CoV-2 infection induced an immunological process targeting orbital tissue. Autoimmune myositis has been reported as a manifestation of COVID-19 infection.9

Literature Search

PubMed CENTRAL, Google Scholar, and Ovid MEDLINE were searched in February 2021 using the following terms: orbital myositis, orbital cellulitis, orbital pseudotumor, corona virus, and COVID-19 infection.

References

- 1.Gautret P., Lagier J.C., Parola P., et al. Clinical and microbiological effect of a combination of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin in 80 COVID-19 patients with at least a six-day follow up: a pilot observational study. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;34:101663. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McNab A.A. Orbital myositis: a comprehensive review and reclassification. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;36:109–117. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000001429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen L., Deng C., Chen X., et al. Ocular manifestations and clinical characteristics of 535 cases of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a cross-sectional study. Acta Ophthalmol. 2020;98:e951–e959. doi: 10.1111/aos.14472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greer C.E., Bhatt J.M., Oliveira C.A., Dinkin M.J. Isolated cranial nerve 6 palsy in 6 patients with COVID-19 infection. J Neuroophthalmol. 2020;40:520–522. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0000000000001146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Falcone M.M., Rong A.J., Salazar H., Redick D.W., Falcone S., Cavuoto K.M. Acute abducens nerve palsy in a patient with the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) J AAPOS. 2020;24:216–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turbin R.E., Wawrzusin P.J., Sakla N.M., et al. Orbital cellulitis, sinusitis and intracranial abnormalities in two adolescents with COVID-19. Orbit. 2020;39:305–310. doi: 10.1080/01676830.2020.1768560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martínez Díaz M., Copete Piqueras S., Blanco Marchite C., Vahdani K.J.O. Acute dacryoadenitis in a patient with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Orbit. 2021:1–4. doi: 10.1080/01676830.2020.1867193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valente P., Iarossi G., Federici M., et al. Ocular manifestations and viral shedding in tears of pediatric patients with coronavirus disease 2019: a preliminary report. J AAPOS. 2020;24:212–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2020.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beydon M., Chevalier K., Al Tabaa O., et al. Myositis as a manifestation of SARS-CoV-2. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217573. annrheumdis-2020-217573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]