Abstract

Problems accessing affordable treatment are common among low-income adults with substance use disorders. A difference-in-differences analysis was performed to assess changes in insurance and treatment of low-income adults with common substance use disorders following the 2014 ACA Medicaid expansion, using data from the 2008–2017 National Surveys on Drug Use and Health. Lack of insurance among low-income adults with substance use disorders in expansion states declined from 34.8% (2012–13) to 20.0% (2014–15) to 13.5% (2016–17) while Medicaid coverage increased from 24.8% (2012–13) to 48.0% (2016–17). In non-expansion states, lack of insurance declined from 44.8% (2012–13) to 34.2% (2016–17) and Medicaid coverage increased from 14.3% (2012–13) to 23.4% (2016–17). Treatment rates remained low and little changed. Medicaid expansion contributed to insurance coverage gains for low-income adults with substance use disorders, although persistent treatment gaps underscore clinical and policy challenges of engaging these newly insured adults in treatment.

Introduction

Approximately one in five US adults has a substance use disorder1 of which only around one in ten receive treatment.2 Problems accessing affordable treatment is a leading reason for undertreatment.3 Lack of health coverage can pose a financial barrier for substance use treatment, particularly for low-income adults,4 a group that has an elevated risk for drug use disorders.5

The Medicaid expansion provision of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2014 has the potential to narrow gaps in insurance coverage and improve access to substance use treatment. The expansion targeted populations that previously had limited access to health care coverage, particularly low-income non-elderly adults without children. Even before Medicaid expansion, however, Medicaid was the largest source of financing of behavioral health services in the United States.6 One reason for its large role is that Medicaid eligibility spanned several high-need groups including low income women, people with disabilities, and older adults. Prior to the ACA, several states received Section 1115 Medicaid demonstration waivers to expand coverage, change delivery systems, or revise benefits to low-income adults7 with evidence of modest increase in Medicaid coverage among substance use disorder treatment admissions.8 Following passage of the Affordable Care Act in March 2010, but before Medicaid expansion in 2014, five states and the District of Columbia enacted early versions of Medicaid expansion. Medicaid administrators in these early expansion states reported greater than expected demand for substance use disorder treatment.9

In states that expanded Medicaid, income-based eligibility rules extended Medicaid eligibility to many not previously eligible low-income adults. During the first two years following Medicaid expansion (2014–2015), there was a significant decline in low-income adults with substance use disorders in expansion states who were uninsured.10 Prior research further indicates that Medicaid expansion has increased access to treatment with opioid agonist medications.11,12

Whether these early gains in Medicaid coverage among low-income adults with substance use disorders have continued and whether they have coincided with an increase in treatment of low-income adults with common substance use disorders has not been previously examined. This analysis updates an earlier analysis of data from the National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH)10 by evaluating the effects of ACA Medicaid expansion on health insurance coverage and treatment of low-income adults with alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, or heroin use disorders during the first four years following the expansion (2014–2017).

Methods

The NSDUH is an annual cross-sectional national and state representative survey of the civilian noninstitutionalized US population, conducted by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.13 Data from 2008–2017 were pooled into two-year blocks to improve precision. The sample included low-income adults, aged 18–64 years, who met diagnostic criteria for past-year DSM-IV alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, or heroin use disorders. Following the ACA Medicaid income eligibility threshold, low income was defined as self-reported household income of equal or less than 138% of the Federal Poverty Level. Respondent age, sex, race/ethnicity, education level, and state of residence were also collected by self-report.

Health insurance was classified as Medicaid only, other public insurance, private insurance, and no insurance at the time of the survey. Substance use disorder treatment was defined by treatment received for illicit drug or alcohol use. Treatment included services received in the past year within a hospital, rehabilitation facility, mental health center, emergency department, private physician’s office, or other organized settings. Services provided in prisons or jails or by self-help groups, which are not reimbursed by insurance, were not included. In the primary analysis, states that expanded Medicaid by the end of 2014 were considered expansion states. In a sensitivity analysis, states were removed that expanded earlier than January 2014 (California, Connecticut, District of Columbia, Minnesota, New Jersey, and Washington) or expanded during 2015–2017 (Alaska, Indiana, Pennsylvania, Montana, and Louisiana).

Trends in insurance status were compared among adults residing in expansion and non-expansion states before and after Medicaid expansion implementation (January 2014). A difference-in-differences approach measured differences in insurance coverage, treatment by coverage group, and treatment across state groups over time. Multivariable logistic regression models were used for estimation and included categorical survey years; an expansion state dummy variable; an interaction term for year x expansion state; covariates age, sex, race/ethnicity, education level; and state as independent variables. Adjusted difference estimates in outcomes tested change over time within expansion and non-expansion states. The interaction contrast on the predicted prevalence scale from the model provided difference-in-differences tests indicating whether changes over time differed between expansion and non-expansion states. SAS callable SUDAAN accounted for NSDUH’s complex sample design and sample weights was used for the analyses.

Results

In the combined NSDUH samples, most adults with substance use disorders in expansion and non-expansion states were males, under 35 years of age and had alcohol use disorders (Table 1). A smaller percentage had cannabis, cocaine, or heroin use disorders. Approximately one-half were white non-Hispanic and a smaller percentage had at least some college education.

Table 1.

Characteristics of low-income adults with substance use disorders in states that did and did not expand eligibility for Medicaid

| Expansion States | Non-Expansion states | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age range, years | Percent | SE | Percent | SE | |

| 18–25 | 41.4 | (0.84) | 40.0 | (0.97) | 0.13 |

| 26–34 | 22.1 | (0.74) | 21.0 | (0.78) | |

| 35–44 | 15.7 | (0.68) | 14.9 | (0.76) | |

| 45–64 | 20.8 | (0.89) | 24.1 | (1.07) | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 61.0 | (0.82) | 63.3 | (0.84) | 0.05 |

| Female | 39.0 | (0.82) | 36.7 | (0.84) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 49.2 | (0.92) | 53.5 | (103) | <.0001 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 17.6 | (0.70) | 24.0 | (0.86) | |

| Hispanic | 24.8 | (0.84) | 16.7 | (0.82) | |

| Other | 8.5 | (0.46) | 5.7 | (0.39) | |

| Education level | |||||

| Less than high school | 28.9 | (0.85) | 32.1 | (0.99) | 0.02 |

| High school graduate | 30.1 | (0.78) | 30.6 | (0.86) | |

| Some college | 30.7 | (0.82) | 28.7 | (0.92) | |

| College graduate | 10.2 | (0.51) | 8.6 | (0.46) | |

| Substance use disorders in past year | |||||

| Alcohol | 78.4 | (0.66) | 81.6 | (0.71) | 0.001 |

| Marijuana | 27.1 | (0.70) | 23.2 | (0.75) | 0.0001 |

| Cocaine | 7.4 | (0.46) | 8.9 | (0.62) | 0.06 |

| Heroin | 5.4 | (0.42) | 3.0 | (0.30) | <.0001 |

Source: Authors’ analysis of data from the 2008–2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Notes: Low-income adults are those with incomes of no more than 138 percent of the federal poverty level. Selected disorders include alcohol, cannabis (marijuana), heroin, and cocaine use disorders. Expansion states are those that expanded Medicaid in 2014 or earlier. There were 9,700 respondents in expansion states and 7,600 in non-expansion states. p values from chi-square statistics. Because the age groups are mutually exclusive groups, one test statistic was computed; the individual substance use disorders are not mutually exclusive groups, so separate test statistics were computed. SE is standard error.

A comparison of trends in uninsurance among low income adults with substance use disorders before and after Medicaid expansion revealed a decrease in uninsured adults in expansion states from 34.8% in 2012–13 to 20.0% in 2014–15 and to 13.5% in 2016–17 (Table 2). Among those in non-expansion states, lack of insurance decreased more modestly from 44.8% in 2012–13 to 40.1% in 2014–15 and to 34.2% in 2016–17. Between 2012–13 and 2014–15, the decrease in uninsured adults was significantly larger for those in expansion than non-expansion states (difference-in-differences: −10.0%, 95% CI: −17.0, −3.0), although not between 2014–15 and 2016–17 (−0.7%, 95% CI: −7.2, 5.8). In the sensitivity analysis that removed states which expanded earlier than January 2014 or during 2015–2017, this difference-in-differences in uninsured individuals was also significant (−11.4%, 95% CI: −19.1, −3.6).

Table 2.

Changes in health insurance among income eligible adults with selected substance use disorders, 2012–2017

| Group | 2012–13 | 2014–15 | Difference Estimate | Difference in Differences Estimate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | |

| Medicaid, Expansion | 24.9 | 22.0, 28.0 | 38.4 | 35.1, 41.9 | 13.6 | 9.1, 18.1 | 8.3 | 2.3, 14.4 |

| Medicaid, Non-expansion | 14.3 | 12.0, 17.0 | 19.5 | 16.6, 22.9 | 5.2 | 1.2, 9.2 | ||

| Private Insurance, Expansion | 27.1 | 24.3, 30.0 | 27.1 | 24.3, 30.1 | 0 | −4.0, 4.0 | −0.4 | −6.0, 5.2 |

| Private insurance, Non-Expansion | 26.7 | 23.9, 29.7 | 27.0 | 24.2, 30.0 | 0.4 | −3.6, 4.4 | ||

| Other public, Expansion | 13.6 | 11.0, 16.6 | 14.5 | 12.0, 17.3 | 0.9 | −3.0, 4.7 | 1.2 | −4.3, 6.7 |

| Other public, Non-Expansion | 14.0 | 11.4, 17.2 | 13.7 | 11.2, 16.6 | −0.4 | −4.3, 3.6 | ||

| Uninsured, Expansion | 34.8 | 31.2, 38.6 | 20.0 | 17.6, 22.8 | −14.8 | −19.3, −10.2 | −10.0 | −17.0, −3.0 |

| Uninsured, Non-Expansion | 44.8 | 41.0 48.8 | 40.1 | 36.3, 43.9 | −4.8 | −10.1, 0.6 | ||

| 2014–15 | 2016–17 | |||||||

| Medicaid, Expansion | 38.4 | 35.1, 41.9 | 48.0 | 44.5, 51.5 | 9.5 | 4.8, 14.3 | 5.7 | −1.0, 12.4 |

| Medicaid, Non-expansion | 19.5 | 16.6, 22.9 | 23.4 | 20.2, 26.9 | 3.8 | −0.7, 8.4 | ||

| Private Insurance, Expansion | 27.1 | 24.3, 30.1 | 27.5 | 24.8, 30.4 | 0.4 | −3.4, 4.3 | −3.6 | −9.6, 2.3 |

| Private insurance, Non-Expansion | 27.0 | 24.2, 30.0 | 31.1 | 27.9, 34.6 | 4.1 | −0.3, 8.5 | ||

| Other public, Expansion | 14.5 | 12.0, 17.3 | 11.4 | 9.2, 14.0 | −3.1 | −6.6, 0.4 | −0.8 | −6.0, 4.4 |

| Other public, Non-Expansion | 13.7 | 11.2, 16.6 | 11.4 | 9.1, 14.2 | −2.3 | −6.0, 1.4 | ||

| Uninsured, Expansion | 20.0 | 17.6, 22.8 | 13.5 | 11.3, 16.1 | −6.6 | −10.1, −3.0 | −0.7 | −7.2, 5.8 |

| Uninsured, Non-Expansion | 40.1 | 36.3, 43.9 | 34.2 | 30.6, 38.0 | −5.8 | −11.3, −0.4 | ||

Data from NSDUH. Income eligible defined as ≤138% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL). Differences adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, state, and education.

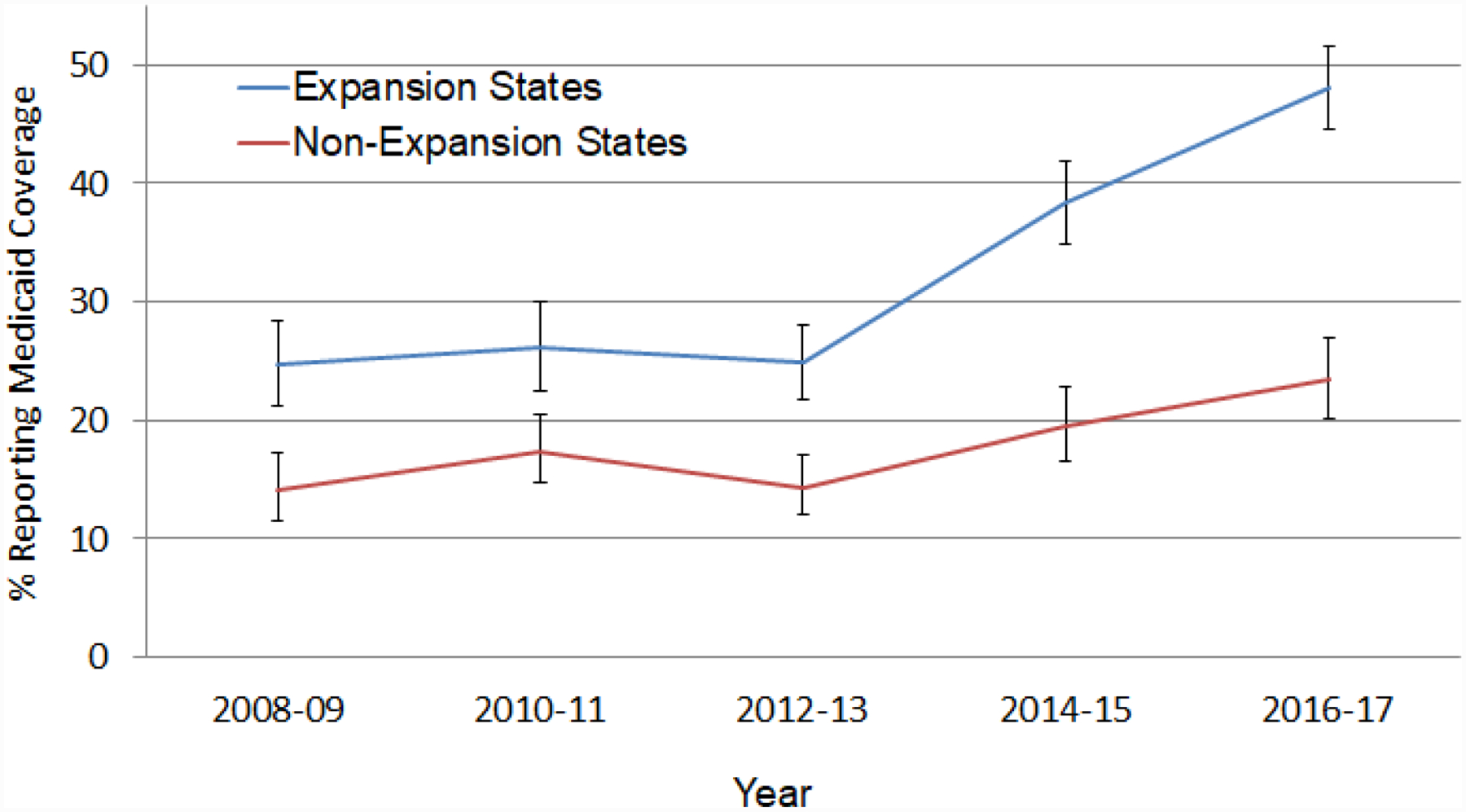

In expansion states, there was a marked increase in Medicaid coverage from 24.8% in 2012–13 to 38.4% in 2014–15 to 48.0% in 2016–17 (Figure 1). Medicaid coverage among those in non-expansion states increased more slowly from 14.3% in 2012–13 to 19.5% in 2014–15 to 23.4% in 2016–2017. Medicaid coverage increased significantly faster in expansion than non-expansion states during 2012–13 to 2014–15, although the difference-in-differences was not significant between 2014–15 and 2016–17. In the sensitivity analysis, these difference-indifferences were also significant between 2012–13 and 2014–15 (8.8%, 95% CI: 2.1%, 15.5%), but not between 2014–15 and 2016–2017 (5.7%, 95% CI: −2.2%, 13.5%).

Figure 1:

Changes in Medicaid coverage among low income adults in expansion and non-expansion states, 2008–2017

Data from NSDUH. Low income defined as ≤138% of the Federal Poverty Level. Error bars represent 95%Cis.

There were no significant changes between consecutive two-year periods in private insurance coverage for the expansion or non-expansion state groups. An increase in private insurance from 2014–15 to 2016–17 in non-expansion states did not meet conventional levels of statistical significance in main analyses (4.1%, 95% CI: −0.3, 8.5) or in the sensitivity analysis (−0.6%, 95% CI: −6.8, 5.6).

Among low-income adults who received substance use treatment, the percentage with Medicaid in expansion states increased from 28.2% in 2012–13 to 63.2% in 2016–17. In non-expansion states, Medicaid coverage of those who received treatment was little changed between 2012–13 and 2014–15, before increasing between 2014–15 and 2016–17 (Table 3). In the sensitivity analysis, this difference remained significant (estimated difference: 7.1%, 95% CI:0.3, 13.8).

Table 3.

Health insurance among low income adults with substance use disorders who received substance use treatment

| Group | 2012–13 | 2014–15 | Difference Estimate | Difference in Differences Estimate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | |

| Medicaid, Expansion | 28.2 | 19.4, 39.1 | 59.8 | 49.6, 69.2 | 31.6 | 17.6, 45.5 | 29.4 | 8.4, 50.3 |

| Medicaid, Non-expansion | 24.7 | 14.3, 39.1 | 26.9 | 19.2, 36.4 | 2.2 | −12.9, 17.3 | ||

| Private Insurance, Expansion | 16.0 | 10.0, 24.8 | 11.3 | 7.5, 16.6 | −5.8 | −13.4, 3.9 | −10.4 | −23.2, 2.2 |

| Private insurance, Non-Expansion | 12.2 | 6.9, 20.6 | 17.9 | 12.3, 25.5 | 5.7 | −3.6, 15.1 | ||

| Other public, Expansion | 20.7 | 13.2, 31.1 | 15.0 | 9.1, 23.7 | −5.8 | −17.2, 5.6 | −8.0 | −26.8, 10.8 |

| Other public, Non-Expansion | 19.1 | 9.9, 33.7 | 21.3 | 13.6, 31.8 | 2.2 | −12.6, 17.0 | ||

| Uninsured, Expansion | 35.8 | 26.1, 46.7 | 13.2 | 7.8, 21.8 | −22.6 | −35.1, −10.0 | −12.9 | −35.0, 9.2 |

| Uninsured, Non-Expansion | 42.0 | 28.5, 57.0 | 32.4 | 23.4, 43.9 | −9.7 | −27.4, 8.0 | ||

| 2014–15 | 2016–17 | |||||||

| Medicaid, Expansion | 59.8 | 49.6, 69.2 | 63.2 | 53.7, 71.8 | 3.4 | −10.2, 17.0 | −13.0 | −32.6, 6.7 |

| Medicaid, Non-expansion | 26.9 | 19.2, 36.4 | 43.3 | 33.2, 54.0 | 16.4 | 3.4, 29.4 | ||

| Private Insurance, Expansion | 11.3 | 7.5, 11.6 | 14.3 | 10.0, 20.0 | 3.0 | −3.6, 9.5 | 8.1 | −2.2, 18.6 |

| Private insurance, Non-Expansion | 17.9 | 12.3, 25.5 | 12.7 | 8.2, 19.2 | −5.2 | −13.2, 2.8 | ||

| Other public, Expansion | 15.0 | 9.1, 23.7 | 10.7 | 5.9, 18.6 | −4.3 | −13.4, 4.9 | −2.5 | −18.0, 12.9 |

| Other public, Non-Expansion | 21.3 | 13.6, 31.8 | 19.6 | 12.2, 29.9 | −1.7 | −14.1, 10.7 | ||

| Uninsured, Expansion | 13.2 | 7.6, 21.8 | 11.5 | 6.5, 19.4 | −1.7 | −11.0, 7.6 | 5.1 | −11.1, 21.2 |

| Uninsured, Non-Expansion | 32.4 | 23.4, 42,9 | 25.6 | 17.5, 35.8 | −6.7 | −19.7, 6.1 | ||

Data from NSDUH. Income eligible defined as ≤138% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL). Differences adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, state, and education.

Among those who received substance use treatment, the percentage in expansion states who were uninsured declined from 38.5% in 2012–13 to 12.3% in 2014–17 while the corresponding decrease for non-expansion state patients was not significantly changed from 42.1% in 2012–13 to 28.9% in 2014–17 (−13.2%,95% CI: −29.5, 3.0) (data not shown in Tables).

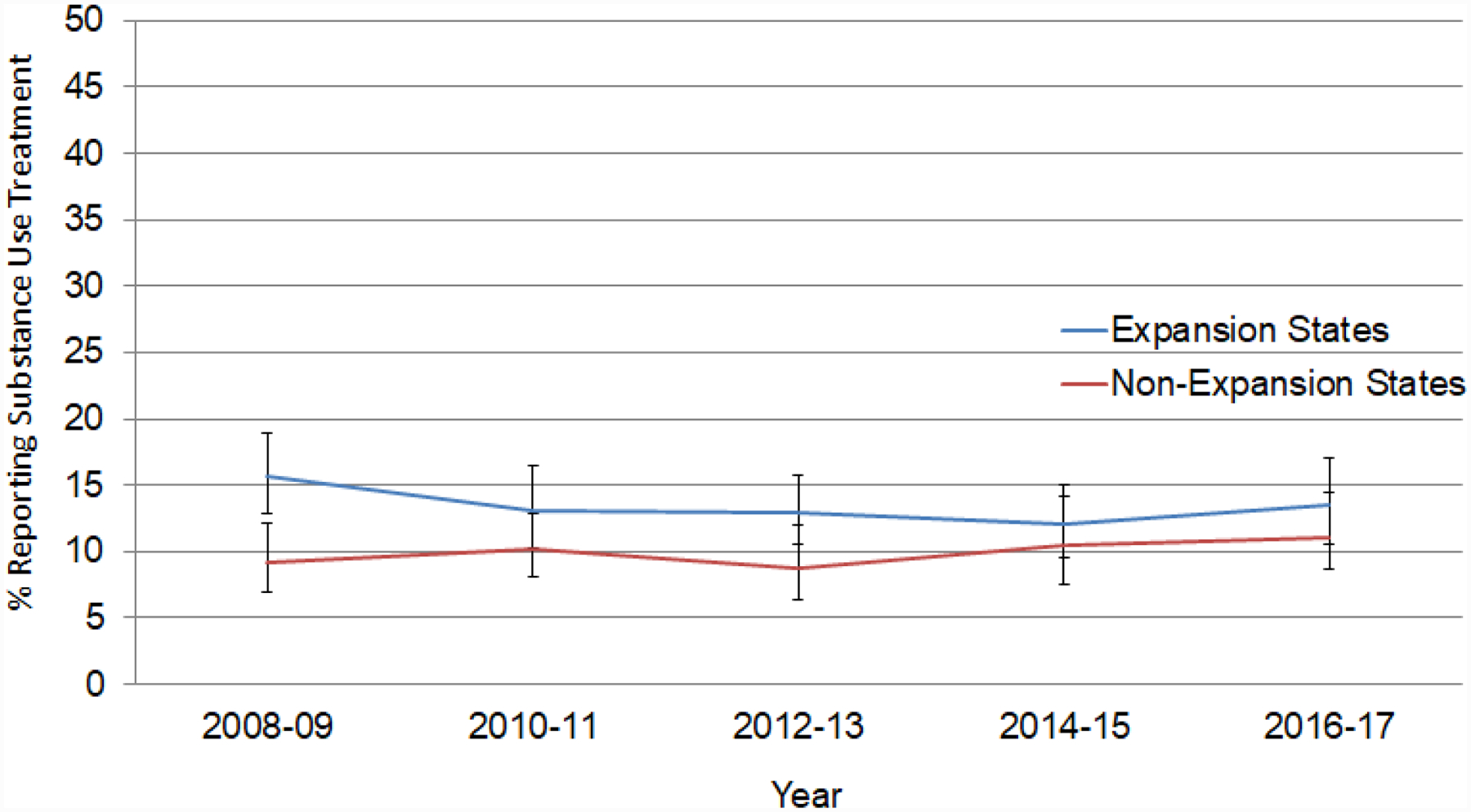

Approximately one in ten low-income adults with substance use disorders in expansion and non-expansion states reported receiving treatment. There were no significant changes in the expansion or non-expansion state groups in the percentage who reported treatment during the study period. In expansion states, treatment was received by 12.9% in 2012–13, 12.0% in 2014–15, and 13.5% in 2016–17 while in non-expansion states these percentages were 8.8%, 10.3%, and 11.1%, respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 2:

Changes in past year substance use disorder treatment among low income adults with select selected substance use disorders in expansion and non-expansion states, 2008–2017

Data from NSDUH. Low income defined as ≤138% of the Federal Poverty Level. Error bars represent 95% CIs.

Discussion

The decrease in uninsured low-income adults with substance use disorders in expansion states that started during the first two years following ACA Medicaid expansion (2014–15) continued during the following two years (2016–2017). This decline was driven primarily by increases in Medicaid coverage. Medicaid expansion appears to have reduced coverage barriers to substance use treatment. During this period, Medicaid assumed a more prominent role in financing substance use treatment of low-income adults, especially in expansion states. By 2016–17, nearly two-thirds of low-income adults treated for substance use disorders in expansion states had Medicaid coverage.

Yet these gains in insurance coverage have not contributed to a measurable increase in treatment of common substance use disorders in these large household samples. In evaluating this finding, it is important to note that over three-quarters of the adults in the substance use disorder study groups had alcohol use disorder. The findings suggest that factors other than insurance coverage impede entry into treatment of these adults. Some recognized barriers include stigma and privacy concerns, geographic and regulatory barriers, and lack of patient and provider confidence in treatment effectiveness.14 Many people enter substance use services for reasons unrelated to Medicaid coverage, for example, because they are mandated or coerced by the courts, employers, or concerned family members.15 In addition, some substance use treatment is supported by federal Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment Block Grant program and provided without charge to clients.16 State allocations to the Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment Block Grant program remained nearly constant ($1.82 billion in 2014 and $1.86 billion in 2019)17,18 following Medicaid expansion.

The effects of Medicaid expansion on treatment access are also likely constrained by the limited availability of substance use treatment programs that accept Medicaid. In 2009, 46% of US substance use treatment facilities did not accept Medicaid and 38% of counties had no substance use treatment facilities that accepted Medicaid. In this analysis, several future non-expansion states had a relatively low density of substance use treatment facilities that accepted Medicaid.19 Expansion and non-expansion states also appear to differ in their coverage of substance use services. A national survey conducted around the time of expansion (2013–14) further revealed that 21% of non-expansion and 7% of expansion state Medicaid programs covered two or fewer of seven possible basic substance use services.20 Beyond expanding Medicaid coverage, increasing the number of programs that accept Medicaid and the range of Medicaid covered services might help increase Medicaid beneficiaries receive needed substance use treatment.

Prior research with facility-level data indicates that Medicaid expansion coincided with disproportionate increases in medication treatment of opioid use disorder21,22 and other substance use disorders23 in expansion states. Weaker evidence further suggests that Medicaid-financed admissions to specialty substance use disorder facilities increased following Medicaid expansion.23 Because, however, these studies did not measure prevalence of substance use disorders in the population, they cannot distinguish whether treatment increased due to a rising prevalence of substance use disorders or due to expanding Medicaid coverage. Some evidence from the period before ACA has suggested a longitudinal association between Medicaid insurance and use of substance use treatments that are covered by insurance.24

This study has several important limitations. First, other contemporaneous changes in the policy landscape, such as the Health Insurance Marketplaces, may have contributed to the overall trends in health insurance coverage. Second, due to a redesign of NSDUH in 2015, it was not possible to assess trends in treatment of prescription opioid use disorder or use of stimulants or sedatives. Third, NSDUH queried substance use “treatment or counseling” without specifically mentioning medication treatments such as buprenorphine or disulfiram and therefore medication treatments may have been undercounted. Other research has shown a substantial recent increase in buprenorphine treatment among Medicaid beneficiaries25 that has occurred disproportionately in expansion states.12 Fourth, claims-based analyses suggest that the NSDUH may underestimate the prevalence of opioid use disorders.26 Finally, the NSDUH sampling frame excluded institutionalized and homeless adults; both groups at increased risk of substance use disorders.

Implications for Behavioral Health

Although there has been an impressive decline in uninsured low-income adults with common substance use disorders in expansion states, challenges remain in translating expanded coverage into meaningful improvements in access to substance use treatment beyond previously reported progress in increased utilization of medication treatment of opioid use disorder. Vigorous and coordinated substance use policy efforts are needed to develop accessible treatment options for newly insured low-income adults with substance use disorders.

One strategy for building the capacity to treat the newly insured population involves increasing substance use treatment programs that accept Medicaid. Nationwide nearly half of substance use treatment programs do not accept Medicaid.19,27 Many of these programs lack the staffing and technical capabilities required for Medicaid billing certification. Helping substance use treatment programs to meet Medicaid certification standards could involve developing formal collaborations with established Medicaid certified programs.28 Assisting substance use treatment programs obtain Medicaid certification together with outreach efforts might narrow the large and persistent gap in unmet need for substance use treatment among low-income adults. Another potential strategy involves smaller substance use treatment agencies partnering with Federal Qualified Health Centers that have greater experience with Medicaid billing requirements and procedures.

A key complementary policy strategy involves expanding integration of Medicaid-reimbursed substance use treatment into primary care practices in the general medical sector. One policy constraint complicating integration is that unlike hospital-based detoxification which is mandated, outpatient care for alcohol and drug treatment is an optional benefit in traditional Medicaid and many state Medicaid plans do not include coverage for these services.20 Nevertheless, expanding substance use covered services within primary care settings, through informal collaboration or formal mergers with shared billing and other administration functions, may be a particularly promising strategy for expanding access to buprenorphine treatment for adults with opioid use disorders where there is evidence that Medicaid expansion has expanded treatment access.11,12

Funding source:

This work is supported by NIDA R01 DA039137.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Olfson M, Blanco C, Wall M, et al. Treatment of common mental disorders in the United States. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 2019;80(3):18m12532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lipari RN, Van Horn SL. Trends in substance use disorders among adults aged 18 or older. The CBHSQ Report: June 29, 2017. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Rockville, MD: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ali MM, Teich JL, Mutter R. Reasons for not seeking substance use disorder treatment: variations by health insurance coverage. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2017;44(1):63–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality (CBHSQ). 2015. Behavioral health trends in the United States: results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. HHS Publication No. SMA 15–4927, NSDUH Series H-50 Rockville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hasin DS, Grant BF. The National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) waves 1 and 2: review and summary of findings. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2015;50:1609–1640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garfield RL. Mental health financing in the United States: a primer. Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, April 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaiser Common Medicaid and the Uninsured, Five key questions and answers about section 1115 Medicaid demonstration waivers. June 2011. https://www.kff.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/8196.pdf Accessed on August 10, 2020.

- 8.Tormohlen KN, Krawczyk N, Feder KA, et al. Evaluating the role of Section 1115 waivers on Medicaid coverage and utilization of opioid agonist therapy among substance use treatment admissions. Health Services Research. 2019. December 29;55(2):232–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sommers BD, Arnston E, Kenney GM, Epstein AM. Lessons from early Medicaid expansions under health reform interviews with Medicaid officials. Medicare & Medicaid Research Review 2013;3(4): E1–E19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olfson M, Wall M, Barry CL, et al. Impact of Medicaid expansion on coverage and treatment of low-income adults with substance use disorders. Health Affairs 2018;37(8):1208–1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mojtabai R, Mauro C, Wall M, et al. The Affordable Care Act and opioid agonist therapy for opioid use disorder. Psychiatric Services 2019; 70 (7):617–620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mojtabai R, Mauro C, Barry C, et al. Medication treatment for opioid use disorders in substance use treatment facilities in the United States. Health Affairs 2019;38:14–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Survey on Drug Use and Health [Internet]. Rockville (MD): SAMHSA; Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/data-we-collect/nsduh-national-survey-drug-useand-health Accessed on August 10, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2019. Medications for opioid use disorder save lives. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. 10.17226/25310 Accessed on August 10, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wild TC. Social control and coercion in addiction treatment: towards evidence-based policy and practice. Addiction 2006;101(1):40–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buck JA. The looming expansion and transformation of public substance abuse treatment under the Affordable Care Act. Health Affairs 2011; 1402–1410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Department of Health and Human Services, fiscal year 2021 justification of estimates for appropriations committees, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/about_us/budget/fy-2021-samhsa-cj.pdf Accessed on August 10, 2020.

- 18.Department of Health and Human Services, fiscal year 2016 justification of estimates for appropriations committees, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/samhsa-fy2016-congressional-justification_2.pdf Accessed on August 10, 2020.

- 19.Cummings JR, Wen H, Ko M, Druss BG. Race/ethnicity and geographic access to Medicaid substance use disorder treatment facilities in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry 2014;71(2):190–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andrews CM, Grogan CM, Westlake MA, Abraham AJ, et al. , Do benefits restrictions limit Medicaid acceptance in addition treatment? Results from a national study. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 2018;87:50–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wen H, Hockenberry JM, Borders TF, Druss BG. Impact of Medicaid expansion on Medicaid-covered utilization of buprenorphine for opioid use disorder treatment. Medical Care 2017;55:336–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meinhofer A, Witman AE. The role of health insurance on treatment for opioid use disorders: evidence from the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansion. Journal of Health Economics 2018;60:177–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maclean LC, Saloner B. The effect of public insurance expansions on substance use disorder treatment: evidence from the Affordable Care Act. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 2019;38(2):366–393. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mojtabai R, Feder KA, Kealhofer M, et al. State variations in Medicaid enrollment and utilization of substance use services: Results from a National Longitudinal Study. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 2018; 89:75–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wen H, Hockenberry JM, Pollack HA. Association of buprenorphine-waivered physician supply with buprenorphine Treatment Use and Prescription Opioid Use in Medicaid Enrollees. JAMA Network Open 2018;1(5):e182943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barocas JA, White LF, Wang J, et al. , Estimated prevalence of opioid use disorder in Massachusetts, 2011–2015: a capture–recapture analysis. American Journal of Public Health 2018;108:1675–1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andrews CM. The relationship of state Medicaid coverage to Medicaid acceptance among substance abuse providers in the United States. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research 2014;41(4): 460–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andrews C, Abraham A, Grogan CM, et al. , Despite resources from the ACA, most states do little to help addiction treatment programs implement health care reform. Health Affairs 2015;34(5):828–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]