Abstract

Objective:

To conduct a systematic review of the measures designed to assess sluggish cognitive tempo (SCT) since the first SCT scale using careful test-construction procedures was published in 2009.

Method:

The MEDLINE (PubMed), Embase, PsychINFO, and Web of Science databases were searched from September 2009 through December 2019. Articles reporting on the reliability (internal consistency, test-retest, and inter-rater reliability), structural validity (an aspect of construct validity focused on items’ convergent and discriminant validity), concurrent and longitudinal external validity, invariance, or intervention/experimental findings were included.

Results:

Seventy-six studies met full criteria for data extraction and inclusion. Nine measures for assessing SCT were identified (seven assessing parent-, teacher-, and/or self-report in children and two assessing self- and/or collateral-informant report in adults). Each measure has demonstrated acceptable to excellent reliability. All or at least the majority of SCT items on each measure also had structural validity (high loadings on an SCT factor and low loadings on an ADHD inattention factor). Studies have supported the invariance of SCT across sex and time, and there is also initial evidence of invariance across informants, ADHD and non-ADHD youth, and ADHD presentations. The Child and Adolescent Behavior Inventory (CABI), Child Concentration Inventory, Second Edition (CCI-2), and the Barkley Adult ADHD Rating Scale-IV (BAARS-IV) have particularly strong support for assessing parent/teacher-reported, youth self-reported, and adult self-reported SCT, respectively.

Conclusion:

The SCT measures included in this review share numerous positive properties, have promising psychometric support, and have proven useful for examining the external correlates of SCT across the life span. Although substantial progress has been made over the last decade, work remains to be done to further improve the assessment of SCT and key directions for future research are provided.

Keywords: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, measurement, psychopathology, sluggish cognitive tempo, systematic review

Introduction

Sluggish cognitive tempo (SCT) refers to a set of behavioral symptoms that include excessive daydreaming, mental confusion and fogginess, being lost in one’s thoughts, and slowed behavior and thinking.1 SCT has historically been studied almost exclusively in the context of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).2 There was initial interest in whether SCT symptoms might prove useful for defining and identifying a “pure” inattentive subtype or presentation of ADHD,3 but when studies failed to consistently support this possibility4,5 researchers increasingly turned to evaluating the extent to which SCT can or should be differentiated from ADHD more broadly.2

In 2016, a meta-analysis of 73 studies examining the factor structure and/or external correlates of SCT was published.1 Strong support was found for 13 SCT constructs/items that in factor analytic studies consistently loaded on an SCT factor as opposed to an ADHD factor. These 13 SCT constructs are listed in Table 1 and marked with a double-dagger symbol (‡). Also listed are constructs that at times have been used to define SCT but were not found in the meta-analysis to load primarily on an SCT factor (e.g., absentminded, easily bored, low initiative/persistence) and as such are not likely to be optimal items to include when assessing SCT, at least as distinguishable from ADHD. In addition, the meta-analysis found SCT to be more strongly associated with internalizing than with externalizing psychopathologies and to be moderately associated with functional impairment.1

Table 1.

Items Used to Assess Sluggish Cognitive Tempo Across Sluggish Cognitive Tempo (SCT)-Specific Measures

| SCT Construct (see1) / Item | ACI | BAARS-IV | BSCTS-CA | CABI | CADBI | CCI | CCI-2 | K-SCT | Penny |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absentminded | |||||||||

| Absentminded | X | ||||||||

| Apathetic/unmotivated a | |||||||||

| Apathetic | X | X | |||||||

| Less engaged in activities than others | (X) | ||||||||

| Little interest in things or activities | X | (X) | |||||||

| Unmotivated | X | X | |||||||

| Withdrawn | (X) | ||||||||

| Daydreams a | |||||||||

| Daydreaming when should be concentrating | X | ||||||||

| Daydreams | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Easily Bored | |||||||||

| Easily bored | X | X | |||||||

| Needs stimulation | (X) | ||||||||

| Easily Confused a | |||||||||

| Confused | X | X | (X) | X | X | X | X | ||

| Mind gets mixed up | X | X | X | X | |||||

| In a Fog a | |||||||||

| In a fog | (X) | X | X | ||||||

| Mentally foggy | X | ||||||||

| Loses Train of Thought/Cognitive Set ‡ | |||||||||

| Alertness fluctuates | X | ||||||||

| Difficulty expressing thoughts | X | ||||||||

| Forgets what was going to say | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Gets “tongue-tied” | (X) | X | |||||||

| Loses train of thought | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Lost in Thoughts ‡ | |||||||||

| In own world | X | X | X | ||||||

| Lost in thoughts | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Mind drifts off | X | ||||||||

| Low Initiative/Persistence | |||||||||

| Effort on tasks fades quickly | X | X | |||||||

| Lacks initiative to complete work | X | X | X | ||||||

| Sleepy/Drowsy a | |||||||||

| Drowsy | (X) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Sleepy | X | (X) | (X) | ||||||

| Trouble staying alert | X | ||||||||

| Trouble staying alert in boring situations | X | ||||||||

| Slow Thinking/Processing a | |||||||||

| Slow information processing | X | X | |||||||

| Slow thinking | X | X | X | ||||||

| Slow Work/Task Completion | |||||||||

| Needs extra time for assignments | X | X | |||||||

| Slow or delayed in completing tasks | X | X | |||||||

| Sluggish a | |||||||||

| Sluggish | (X) | (X) | X | X | |||||

| Spacey a | |||||||||

| Mind seems elsewhere and not paying attention | (X) | ||||||||

| Spaces out | X | X | (X) | X | |||||

| Spacey | X | X | |||||||

| Zones out | (X) | (X) | X | ||||||

| Stares Blankly a | |||||||||

| Stares | X | ||||||||

| Stare into space | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Tired/Lethargic a | |||||||||

| Get tired easily | X | X | X | ||||||

| Lethargic | X | X | (X) | (X) | |||||

| Tired | (X) | (X) | X | X | X | ||||

| Yawning, stretching, sleepy-eyed | X | X | X | ||||||

| Underactive/Slow Moving a | |||||||||

| Less energy than others | (X) | (X) | |||||||

| Low level of activity | X | (X) | |||||||

| Not very active | X | X | |||||||

| Slow behavior | X | X | X | ||||||

| Slow moving | X | X | (X) | (X) | |||||

| Underactive | X | X | (X) | X | X | ||||

Note: Only items in the final measure are indicated; items that were included in the initial pool but removed from the measure during analyses of structural validity are not shown. SCT constructs marked with a superscript dagger (a) were found in a meta-analysis examining SCT items to have a mean factor loading >0.70 on an SCT factor (Becker et al.). Items marked with an (X) indicate that this item is included as part of another item (marked with an ‘X’) that includes multiple SCT-relevant items (e.g., double-barreled questions and parenthetical examples). For comparison purposes, the CBCL/TRF SCT items are: “confused or seems to be in a fog”, “daydreams or gets lost in his/her thoughts”, “stares blankly”, “underactive, slow moving, or lacks energy”, and “apathetic or unmotivated” (this last item is only on the TRF and not the CBCL). ACI = Adult Concentration Inventory. BAARS-IV = Barkley Adult ADHD Rating Scale IV; BSCTS-CA = Barkley SCT Scale Children and Adolescents; CABI = Child and Adolescent Behavior Inventory; CADBI = Child and Adolescent Disruptive Behavior Inventory; CCI = Child Concentration Inventory; CCI-2 = Child Concentration Inventory 2nd Edition; K-SCT = Kiddie Sluggish Cognitive Tempo Scale.

New research indicates that SCT may also be important for clinicians treating children with ADHD. Recent studies indicate that youth with ADHD who have co-occurring SCT symptoms are less likely to respond to front-line methylphenidate treatment6,7 but may respond to atomoxetine.8,9 There is also some indication that children with ADHD and co-occurring SCT symptoms may be less responsive to evidence-based behavioral treatments for ADHD.10 Although these findings will need to be replicated before impacting evidence-based clinical practice guidelines, they make clear that SCT is clinically-relevant and potentially valuable to assess to optimize clinical care for children and adolescents with ADHD.

Although SCT was initially, and continues to be, examined primarily in the context of ADHD, this has appreciably begun to shift. In addition to evaluating SCT in community samples, recent studies have examined SCT in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder,11–13 sleep disorders,14 trauma histories,15 and traumatic brain injuries.16 These studies point to the growing recognition of SCT as important for psychiatry and developmental psychopathology as either a distinct disorder or a construct of transdiagnostic significance.17–19

As SCT research advances and expands, a key priority for the field has been to develop measures that are reliable and valid for the assessment of SCT. For approximately 25 years, investigators interested in SCT relied on ad hoc items that were not subjected to necessary psychometric evaluation.1,2 Indeed, many of the studies included in the meta-analysis examining the empirical differentiation of SCT and ADHD inattention1 had no other option but to assess SCT using an ad hoc measure and so the meta-analysis examined SCT items but did not examine SCT measures. However, the state of affairs changed in 2009, when the first rating scale measure specifically designed to assess SCT using careful test-construction procedures was published.20 That seminal study launched a rapid escalation in the number of studies developing and evaluating rating scales for assessing SCT, though a review of these measures has not previously been conducted. It has now been a decade since that initial SCT measure was published, and this systematic review provides an overview of measures specifically designed to assess SCT that were published since that time.

Method

A systematic search of the literature was completed to identify all studies that included data relevant to the psychometric properties of measures specifically developed for the assessment of SCT. Because the first carefully-constructed SCT scale was published in September 2009,20 computer searches were performed for the dates September 2009 through December 2019 in the MEDLINE (PubMed), Embase, PsychINFO, and Web of Science databases. “Sluggish cognitive tempo” was used as the primary search term (see Supplement 1, available online, for additional information). The reference lists of included studies and reviews1,18,21 were examined for any additional papers.

After duplicate records were removed, the author and another coder independently screened each title and abstract for meeting the following inclusion criteria: (1) peer-reviewed journal article, (2) empirical study (not a review, commentary, or letter to the editor), (3) study conducted with human participants, (4) published in English, and (5) published in an issue or advance online from September 2009 through December 2019. Full texts of the remaining records were further assessed independently by the author and another coder for inclusion eligibility, including the previous five inclusion criteria in addition to the study using a measure developed specifically to assess SCT that had undergone psychometric evaluation, with excellent inter-rater reliability (Cohen’s kappa = 0.93). For example, studies solely using the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL)/Teacher’s Report Form (TRF) measure of SCT were excluded as these scales were not carefully designed to assess SCT specifically and would not be optimal choices for a researcher or clinician interested in assessing SCT. The author and another coder then independently coded each study identified for inclusion using a data extraction form to ensure systematic coding of study characteristics, with disagreement resolved via discussion. When multiple studies utilized data from the same sample, only the first study (or the study with the largest sample size) was included for relevant measure characteristics and psychometric properties, unless subsequent studies included new information (e.g., evaluation of previously-unexamined psychometric properties; longitudinal analyses).

Results

Included Studies

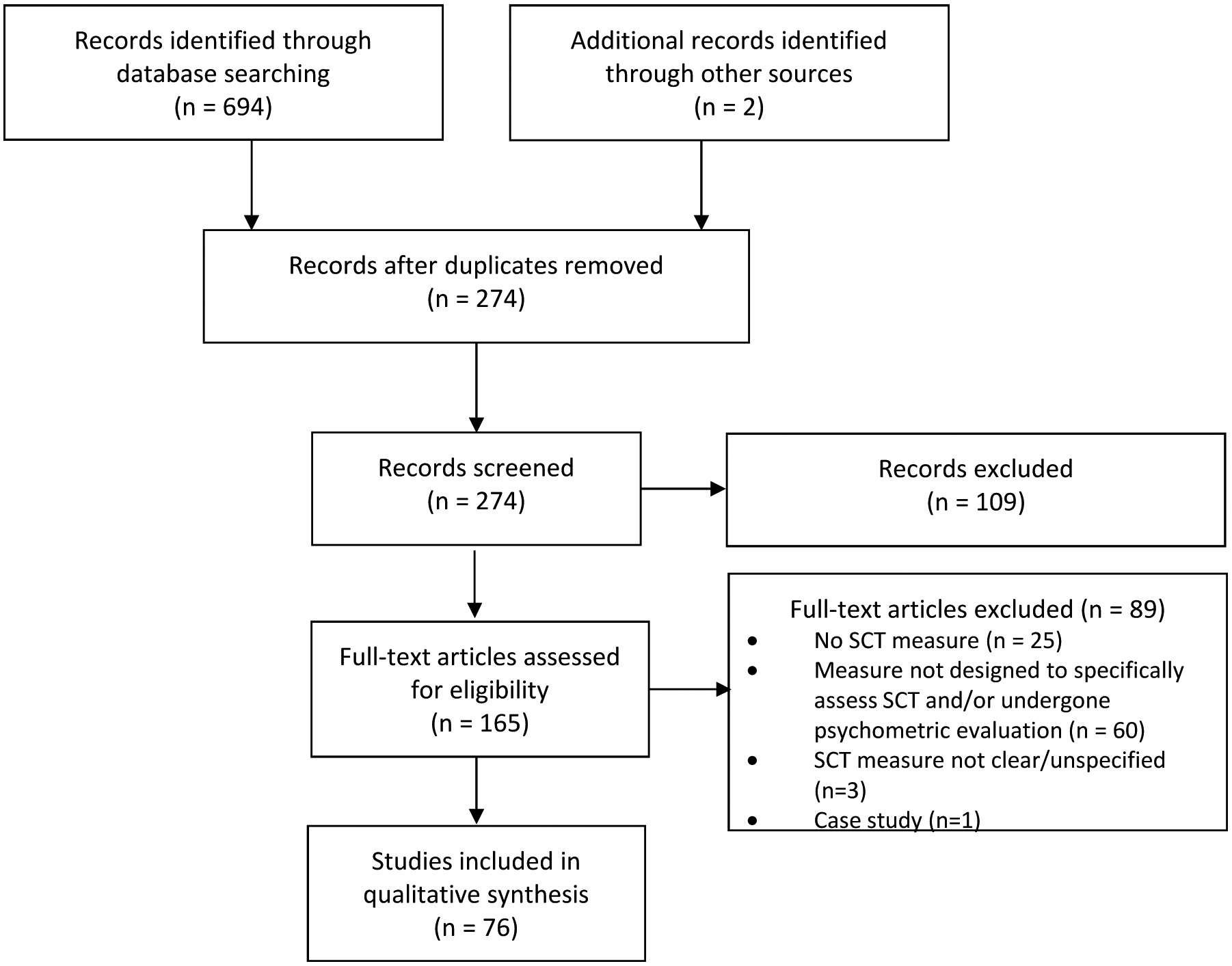

Figure 1 provides the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram. The systematic search identified 274 unique records for title and abstract screening. Of these, 165 records were retained for full-text screening and 76 met full criteria for data extraction and inclusion in the review. Among studies excluded from this review, by far the most common reason was because the study used the CBCL/TRF measure of SCT (n = 39). Details of the 76 included studies are provided in Table S1, available online.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram

Overview of Measures for Assessing SCT

Nine SCT rating scales were identified for inclusion. Six are stand-alone SCT scales,20,22–26 with the remaining three SCT scales embedded in larger measures of adult ADHD symptoms27 or child and adolescent psychopathology.28,29 The SCT items used in each of the identified measures is summarized in Table 1, and details about the nine measures are provided in Table 2. As shown in Table 2, the measures had an initial item pool ranging from 9 to 44 items, with the final measures including 8 to 15 items.

Table 2.

Summary of Sluggish Cognitive Tempo Measures

| Measure | Year Published and Referencea | Informant(s) | No. Items in Initial Item Pool | No. Items in Final Measureb | Response Format | Timeframe | Subscales | Language(s) | Countries Used In | No. Samples Used Inc | Total No. Participantsd | Sample Types | Age Range | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult Concentration Inventory (ACI) | 201822 | Adult self-report | 16 | 10 | Four-point scale (0 = not at all, 3 = very often) | Six months | None | English | USA | 2 | SR: 7,851 | College | 18–29 | Free |

| Barkley Adult ADHD Rating Scale-IV (BAARS-IV) | 201227 | Adult self- and informant-reporte | 9 | 9 | Four-point scale (1 = not at all, 4 = very often) | Six months | None | English, Japanese, Persian, Turkish | Iran, Japan, Turkey, USA | 16 | SR: 5,063 IR: 313 |

Nationally-representative (USA), Community, College, Clinical (ADHD, SUD) | 18–96 | Modest cost (manual purchase includes permission to copy) |

| Barkley SCT Scale – Children and Adolescents (BSCTS-CA) | 201323 | Parent and Teacherf | 14 | 12 | Four-point scale (1 = never or rarely, 4 = very often) | Six months | Sluggish (7 items), Daydreaming (5 items) | English, Turkish | Turkey, USA | 2 | PR: 2,091 TR: 212 |

Nationally-representative (USA), Clinical (ADHD) | 6–17 | Modest cost (manual purchase includes permission to copy) |

| Child and Adolescent Behavior Inventory (CABI) | 201829,30 | Parent and Teacher | 16 | 15 | Six-point scale (0 = almost never [never or about once per month], 5 = almost always [many times per day]) | One month | None | English, Spanish | Spain, USA | 5 | PR: 3,962 TR: 3,122 |

Nationally-representative (USA), School, Clinical (ADHD), Foster Care | 4–17 | Free |

| Child and Adolescent Disruptive Behavior Inventory (CADBI) | 201428 | Parent and Teacher | 10 | 8 | Six-point scale (0 = nearly none of the time, 5 = nearly all of the time) | One month | Noneh | English, Korean, Spanish | Chile, Nepal, South Korea, Spain, USA | 6 | PR: 3,401 TR: 2,439 |

Community, School | 4–16 | Free |

| Child Concentration Inventory (CCI) | 201524 | Youth self-report | 14 | 14 | Four-point scale (0 = not at all, 3 = very much) | Not specified | Total score recommendedi | English | USA | 2 | SR: 217 | School, Community | 8–18 | Free |

| Child Concentration Inventory, 2nd Ed. (CCI-2) | 201925 | Youth self-report | 16 | 15 | Four-point scale (0 = never, 3 = always) | Not specified | None | English, Spanish | USA, Spain | 3 | SR: 2,362 | School, Community, Clinical (ADHD) | 8–17 | Free |

| Kiddie Sluggish Cognitive Tempo Scale (K-SCT) | 201426 | Parent and Teacher | 44 | 15 | Four-point scale (0 = never, 3 = very often) | Not specified | Daydreams (6 items), Sleepy/Tired (4 items), WM Problems (5 items) | English | USA | 2 | PR: 297 TR: 297 |

Clinical (ADHD), Community | 7–13 | Free |

| Penny SCT Scale | 200920 | Parent, Teacher, and Youth Self-Reportg | 26 | 14m | Four-point scale (0 = not at all, 3 = very much) | Not specified | Parentj: Slow (6 items), Sleepy (5 items), Daydreamer (3 items) Teacherj,k,l: Slow (7 items), Sleep/Daydreamer (10 items) | English | Canada, USA | 11 | PR: 1,720 TR: 1,266 SR: 461 |

Clinical (ADHD, Neuropsych Clinic), Community, School | 4–18 | Free |

Note: ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. SUD = substance use disorder.

The year is the year the first peer-reviewed journal article examining the measure was published, which may differ from the year the measure was developed or the year the article was published in advance online format.

The final number of items is the final number as demonstrated in the initial validation study. Subsequent studies may have used or found support for a different number of items, see Table S1, available online, for details.

Number of samples refers to distinct samples, not counting samples that may have been used multiple times across different publications or longitudinal timepoints.

If a sample was used in part or in entirely in multiple studies, the largest sample was used for calculations and other studies using the same sample were not included in the calculation of total number of participants.

The BAARS-IV validation study only examined adult self-report; for studies including the informant-report version, see Kamradt et al.32 and Lunsford-Avery et al.31

The BSCTS-CA validation study only examined parent-report; for a study including a teacher-report version, see Baytunca et al.72

The Penny SCT Scale validation study only examined parent- and teacher-report; for examination of a self-report version, see Smith et al.44,62

See Fenollar Cortés et al.58 for support for a two-factor structure of the CADBI SCT scale (Inconsistent alertness [4 items] and Slowness [3 items]).

Slow, Sleep, and Daydreamer dimensions were found but bifactor analyses led to a total score being recommended

These subscales are based on factor structure analyses with the 14 SCT items. In subsequent analyses that also included ADHD items, all parent and teacher SCT slow items loaded with ADHD inattentive symptoms (Penny et al.20).

The teacher version of the Penny SCT Scale had 3 items that loaded approximately equally on each of the subscales in Penny et al.20, and these three items were not included in the calculation of the teacher SCT subscale scores.

SCT items used in identified measures.

Table 1 summarizes the item content for the nine SCT measures. It is apparent that measures do differ somewhat in their item content. Only the “daydreams” and “sleep/drowsy” domains of SCT are represented in all nine measures, with “tired/lethargic” and “underactive/slow moving” represented in eight measures and “easily confused” and “lost in thoughts” represented in seven measures. Three or fewer measures include item content related to “absentminded,” “easily bored,” “low initiative/persistence,” “slow work/task completion,” and “apathetic/unmotivated”.

Measures for assessing SCT in children and adolescents.

Seven of the measures are for assessing SCT in children and adolescents. These include parent/teacher rating scales,23,26,28,29 youth self-report scales,24,25 and one scale that has been used across parent, teacher, and youth informants.20 Two of the measures24,28 have been updated with more recent versions25,29 based on items with meta-analytic support for assessing SCT.1

As indicated in Table 2, among the parent and teacher measures, the Child and Adolescent Behavior Inventory (CABI)29,30 has been used with the largest number of participants, the Child and Adolescent Disruptive Behavior Inventory (CADBI)28 has been used in the most countries and sample types, and the Penny SCT Scale20 has been used in the most samples. Fewer studies have examined the youth self-report measures, with the Child Concentration Inventory, Second Edition (CCI-2)25 used with the largest number of participants and in the most samples.

Measures for assessing SCT in adults.

Two of the measures are for assessing SCT in adults. The Barkley ADHD Adult Rating Scale-IV (BAARS-IV)27 was validated as a self-report scale of current SCT symptoms and the collateral informant scale has also been used.31,32 The BAARS-IV also includes a clinician-assessed version and forms for retrospectively assessing childhood SCT, though these have yet to be empirically evaluated. The Adult Concentration Inventory (ACI)22 is an adult self-report scale that also includes items assessing SCT-related impairment, though the impairment items remain unexamined.

As indicated in Table 2, the ACI22 has been used with the largest number of participants, though the BAARS-IV27 has been used in a larger number of samples, sample types, and countries, and with a wider age span.

Internal Validity

Table 3 summarizes evidence for the internal validity of the nine SCT measures.

Table 3.

Summary of Evidence for the Reliability and Validity of Sluggish Cognitive Tempo Measures

| Measure | Norms?a | Internal Consistency Reliability | Test-Retest Reliability | Inter-Rater Reliability | Structural Validityb | Invariance | Concurrent External Validityc | Longitudinal External Validityd | Transcultural Validitye | Treatment/Experimental Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult Concentration Inventory (ACI) | No | SR: α = 8880 – .8922 | Not examined | Not examined | 10 items load on SCT factor and distinct from ADHD-IN and INT factors.22 | Not examined | SCT sx uniquely related to ↑ INT sx, emotion dysregulation, daily life EF deficits, functional impairment,22 suicidal behaviors,52 behavioral inhibition system sensitivity, neuroticism81, and reward valuation and exepectancy.80 SCT sx uniquely related to ↓ self-esteem,22 extraversion and conscientiousness.81 |

Not examined | Not examined | Not examined |

| Barkley Adult ADHD Rating Scale-IV (BAARS-IV) | Yes (adult self-report)27 | SR: α = .7945 – .9232 SR: ω = .8447 IR: α = .9132 |

SR: .72)47 – .8827 (2–3 weeks) | SR and IR SCT r = .4131 – .5932 | 9 items load on SCT factor and distinct from ADHD factors.27,45 SCT distinct from daytime sleepiness.46 |

SCT invariant across sex45 | SCT-only group had ↓ education than comparison group; SCT-only and SCT+ADHD groups had ↓ income and ↑ problems with self-organization/ problem-solving than ADHD-only or comparison groups.27 SCT sx uniquely related to ↑ INT sx,32,45,47 academic impairment,45 functional impairment,27,31,82 daily life EF deficits,27,61,82–84 emotion dyscontrol,61 sleep disturbances, daytime sleepiness,46,63 and psychotic sx.85 SCT sx uniquely related to ↓ sleep quality,63 study skills,82 self-regulation learning strategies,86 and ADHD-HI sx.47 In adults with ADHD, participants in moderate and severe SCT groups had ↑ ANX sx; Participants in the severe SCT group had ↑ DEP sx and total INT sx than participants in the moderate SCT group, who in turn had ↑ DEP sx and total INT sx than participants in the minimal SCT group. The severe SCT group also had highest levels of impairment.32 |

Not examined | See studies conducted in Iran,87 Japan,47 and Turkey85,88 | Not examined |

| Barkley SCT Scale – Children and Adolescents (BSCTS-CA) | Yes (parent-report)23 | PR: α = .8372 – .9323 (total score) α = .80 and .83 (Sluggish and Daydreaming, respectively)37 TR: α = .8772 (total score) |

PR: .84 (3–5 weeks)23 | MR-FR, MR-TR, and FR-TR correlation rs = .61, .27 and .31, respectively38 | 12 items load on two SCT factors and distinct from ADHD factors: Sluggish (7 items) and Daydreaming (5 items).23 Two SCT factors, with slightly different item sets than original validation study,23 reported in Turkish study.37,38 |

Not examined | SCT less consistently or strongly associated than ADHD with daily life EF deficits, with SCT more impairing in community-leisure domains.27 SCT sx uniquely related to ↑ INT sx, withdrawal, and social problems, and to ↓ ADHD-HI sx.38 |

Not examined | See studies conducted in Turkey37,38,72 | Not examined |

| Child and Adolescent Behavior Inventory (CABI) | Yes (parent-report)30 | PR: α = .9229,51 – .9550 TR: α = .8851 – .9833 |

PR: .82 (4 weeks)30 | MR-FR, MR-TR, FR-TR factor correlations = .81, .43, and .42, respectively29 MR, FR, and TR factor correlations with CCI-2 SR = .36, .36, and .29, respectively25 PR and SR SCT (on CCI-2) rs = .2751 – .5550 |

Across informants, 15 items load on SCT factor and distinct from ADHD factor.29,30,33 | SCT invariant across sex30,33 and MR, FR, and TR ratings29 | Across informants, the SCT-only group generally had ↑ INT sx, conflicted shyness,30,53 and sleep problems30 than the ADHD-only group, as well as ↓ ODD sx30,53 SCT sx uniquely related to ↑ ANX sx, DEP sx, conflicted shyness,29 social impairment,29,33 academic impairment,33 and to ↓ ADHD-HI sx29 and slower fine motor speed.51 Children in foster care had ↑ SCT sx scores than children not in foster care.89 |

Not examined | See studies conducted in Spain29,53 | Parents reported ↑ SCT sx during sleep restriction than sleep extension.50 |

| Child and Adolescent Disruptive Behavior Inventory (CADBI) | No | PR: α = .7156 – .9155 TR: α = .9136 – .9555 PR: ω = .9060 TR: ω = .9360 PR factor reliability coefficients = .8168 – .9535 TR factor reliability coefficients = .8768 – .9535 |

PR: .8028 (4 weeks); .73 – .7559 (6 weeks) TR: .7436 (4 weeks); 85 – .8657 (6 weeks) PR: stability coefficients = .6754 – .7668 (1 yr); .60 – .6568 (2 yrs) TR: stability coefficients = .51 – .5768 (1 yr); .42 – .4668 (2 yrs) |

M-F factor correlations = .7159 – .8034 PR-TR factor correlation = .3834 – .7635 PT-TA factor correlations = .71 – .7857,68 |

In US and Chile studies, 8 SCT items were distinct from ADHD-IN for both PR and TR28,35 and also showed DV from ANX/DEP.28 In Spain study, 5 SCT items distinct from ADHD across four informants (MR, TR, PT, TA).34 Two SCT factors, reported in one study: Inconsistent Alertness (4 items) and Slowness (3 items).58 |

SCT invariant across M-F, PT-TA, home-school34, and across a 1-yr period49 | Across informants, SCT sx uniquely related to ↑ ANX sx, DEP sx,28,34–36,54–58 social impairment,28,36,54,58–60 emotional reactivity,56 somatic complaints.56

Across informants, mixed findings for SCT sx being uniquely related to ↑ academic impairment28,34,36,54,55,57,59,60 or not uniquely related to academic impairment.35,55 Across informants, mixed findings for SCT sx being uniquely related to ↓ ADHD-HI or ODD sx,28,34,36,55–59 uniquely related to ↑ ADHD-HI or ODD sx,35,58 or not uniquely related to ODD sx.28,36,54–56,59 Across informants, SCT ratings more trait-like than state-like.49 |

TR SCT uniquely predicted ↑ DEP sx, academic impairment, and social impairment 1 month later.36 PR and TR SCT generally uniquely predicted ↑ DEP sx academic impairment, and social impairment 1 yr and 2 yrs later.57,68 PR SCT sx uniquely predicted ↑ ANX sx social impairment 1 yr and 2 yrs later.68 TR SCT sx uniquely predicted ↓ ADHD-HI sx and ODD sx 1 and 2 yrs later, whereas PR SCT sx generally did not uniquely predict ADHD-HI or ODD sx 1 or 2 yrs later.57,68 |

See studies conducted in Chile,35 Nepal,36 South Korea,55,56 and Spain34,49,54,57–59,68 | Not examined |

| Child Concentration Inventory (CCI) | No | α = .7742 – .9171 | Not examined | SR and TR SCT (on Penny) r = .5324 | A three-factor structure of SCT was found (Slow, Sleepy, Daydreamer), though bifactor modeling supported SCT conceptualized as unidimensional.24 SCT showed DV from SR INT sx and TR ADHD sx.24 |

Not examined | SCT sx strongly related to ↑ SR DEP sx, SR ANX sx, and TR ADHD-IN sx, and moderately associated with ↑ TR ADHD-HI sx and ODD/CP sx.24 SCT sx uniquely related to↑ SR loneliness, emotion inhibition, and emotion dysregulation, and to ↓ SR academic competence, academic functioning, social competence, peer relations, self-worth, and emotion coping.24 SCT sx uniquely cross-sectionally related to ↑ TR student-teacher relationship conflict but not uniquely related to student-teacher closeness.42 |

Not examined | Not examined | SR SCT sx lower during sleep extension compared to typical short sleep.71 Adolescents reporting improvement in SCT sx reported ↓ driving problems during sleep extension than during typical short sleep.71 |

| Child Concentration Inventory, 2nd Ed. (CCI-2) | No | α = .8025 – .9550 | .72 (1-wk across two experimental conditions)50 | SR and PR (on CABI) rs = .2751 – .5550 SR-MR, SR-FR, SR-TR factor correlations (on CABI) = .36, .36, and .29, respectively25 |

13 SCT items load on SCT factor and distinct from ADHD43 15 SCT items had moderate to strong loadings on the SCT factor.25 |

SCT invariant across sex and across ADHD and comparison groups43 | SCT sx uniquely related to ↑ SR and PR INT sx, SR suicidal ideation, and SR emotion dysregulation (but not PR emotion dysregulation).43 SCT sx associated with ↑ SR loneliness, SR preference for solitude, ↑ MR, FR, and TR academic impairment, and ↑ MR social impairment.25 SCT sx uniquely associated with slower Grooved Pegboard time and lower Coding scores but not Symbol Search scores.51 |

Not examined | See study conducted in Spain25 | Adolescents reported ↑ SCT sx during sleep restriction than sleep extension.50 |

| Kiddie Sluggish Cognitive Tempo Scale (K-SCT) | No | PR: α = .8926 – .9090 (total score) α = .91, .87, and .85 (Daydreams, WM Problems, and Sleepy/Tired, respectively)26 TR: .9126 – .9390 (total score) α = .95, .90, and .88 (Daydreams, WM Problems, and Sleepy/Tired, respectively)26 |

Not examined | PR and TR SCT sx correlated, r = .13, .22, and .12 for Daydreams, WM Problems, and Sleepy/Tired, respectively26 | Across informants, 15 items load on three SCT factors and distinct from ADHD factors: Daydreams (6 items), WM Problems (5 items), Sleepy/ Tired (4 items).26 | Not examined | Across informants, total SCT sx uniquely related to ↑ problem social bx and organization problems. Total TR SCT also uniquely related to ↑ ANX sx, DEP sx and ↓ social skills and academic enablers.26 In examining SCT subscales across informants, SCT sleepy/tired sx uniquely related to ↑ DEP sx and organization problems and SCT daydreams sx uniquely related to ↑ global impairment.26 For both PR and TR, significant evidence for associations between SCT sx and slower WM manipulation speed and significant evidence against associations between SCT sx and computationally modeled processing speed. For PR only, significant evidence for associations between SCT sx and faster inhibition speed.90 SCT sleepy/tired sx uniquely related to poorer sleep functioning.91 |

Not examined | Not examined | In initial analyses, ↓ SCT sx associated with higher rates of positive response to behavioral tx, but the smaller effect size compared to other variables led it being removed from subsequent models.10 |

| Penny SCT Scalef | No | PR: α = .8762,92 – .9371 (total score) α = .7839 – .8920, .8692 – .9493, .7839 – .8766, and .8192 (Slow, Sleepy/Sluggish, Daydreamer, and Low Initiation respectively) TR: α = .9266 – .9620 (total score) TR Penny20 factor structure: α = .9320 and .9420 (Slow and Sleepy/Daydreamer, respectively) TR Jacobson39 factor structure: α = .8766 – .9493, .9366 – .9593, and .8766 – .8993 (Low Initiation/Persistence, Sleepy/Sluggish, Slow/Daydreamy, respectively) SR: α = .8662 (total score) α = .71, .80, .75 (Slow, Sleepy, Daydreamer, respectively)67 |

PR: test-retest = .87, .87, .83, and .70 for total, Slow, Sleepy, and Daydreamer, respectively (12-week mean time interval)20 | PR and TR SCT sx correlated, r = .2666 – .5220 (total score) PR and TR SCT sx correlated, r =, .27, .17, and .32 for Slow, Sleepy, and Daydreamy, respectively66 TR and SR SCT (on CCI) r = .5324 |

In community sample, For PR, 3 SCT dimensions: Slow (6 items), Sleepy (5 items), and Daydreamer (3 items). For TR, 2 SCT dimensions: Slow (7 items) and Sleepy/ Daydreamer (10 items); 3 of the 14 items loaded ~equally on both SCT factors. For PR and TR, in analyses with ADHD sx, SCT slow items loaded with ADHD-IN.20 In clinical sample, 10 PR items distinct from ADHD-IN: Sleepy/ Sluggish (5 items), Daydreamy (3 items), and Low Initiation (2 items). 11 TR items distinct from ADHD-IN: Sleepy/Sluggish (6 items) and Slow/Daydreamy (5 items).73 For both PR and SR, a bifactor model was the best overall fitting model, with a general factor and slow, sleepy, and daydreamer specific factors.62 SR SCT distinct from SR ANX, DEP, and daytime sleepiness.44 |

SCT not invariant across PR and SR62 SCT invariant across sex, older/younger youth, and ADHD presentation44 |

Across PR and TR, SCT sx uniquely related to ↓ ADHD-HI sx.20 PR SCT sx uniquely related to ↑ PR INT sx,20 PR overall school impairment,66 writing impairment,66 math impairment,66 SR driving violations71 and to ↓ TR homework performance64 and ↓ SR ANX sx.64 TR SCT sx uniquely related to ↓ TR ODD sx,20 TR social acceptance,24 SR emotion coping24 but not academic outcomes.66 SR SCT symptoms uniquely related to ↑ daytime sleepiness,62 SR ANX sx,64 and SR DEP sx.64 In considering SCT subscales, PR SCT sleepy/sluggish, daydreamy, and low initiation sx were each uniquely related to ↑ PR ANX/DEP sx.73 Neither PR nor TR SCT sx uniquely related to TR organizational impairment.65 PR SCT Slow sx uniquely related to to ↑ PR and TR metacognitive daily life EF deficits,93 PR organizational impairment,65 PR homework problems,65 PR school impairment66 and both PR and TR academic problems65 and to ↓ GPA,64 word reading achievement,66 spelling achievement,66 TR homework performance,64 and SR academic motivation.67 PR SCT daydreamy sx uniquely related to to ↑ GPA64 and slower processing speed for younger youth but not older youth.73 PR SCT slow and SCT daydreamy sx uniquely related to ↓ reading fluency and math fluency, whereas SCT sleepy/sluggish uniquely related to ↑ reading fluency and math fluency.39 SCT low initiation sx uniquely related to slower processing speed.73 TR SCT sx dimensions uniquely related to ↑ impairment in academic progress.39 TR SCT slow sx uniquely related to ↓ numerical operations achievement and spelling achievement and to ↑ TR writing impairment.66 TR SCT low initiation/persistence sx uniquely related to ↑ PR homework problems65 and ↓ report card grades.65 TR SCT sx dimensions were not uniquely related to daily life EF deficits,93 TR classroom behavior,39 or TR of children’s selfesteem.39 All three SR SCT subscales uniquely related to ↑ SR ANX sx; SR SCT Slow and Daydreamer sx uniquely related to ↑ SR DEP sx.64 SR SCT slow sx uniquely related to ↓ SR academic motivation.67 |

Not examinedf | Not examined | No effect on PR SCT sx during sleep extension compared to typical short sleep.71 PR SCT sx, but not SR SCT sx, decreased following school-based bx intervention, with PR SCT sx decreasing in the intervention group but not in the waitlist control group.70 |

Note: ACI = Adult Concentration Inventory; ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ADHD-PI = ADHD predominantly inattentive type/presentation; ANX = anxiety; BAARS-IV = Barkley Adult ADHD Rating Scale IV; BSCTS-CA = Barkley SCT Scale Children and Adolescents; C = child/adolescent self-report; CABI = Child and Adolescent Behavior Inventory; CADBI = Child and Adolescent Disruptive Behavior Inventory; CCI = Child Concentration Inventory; CCI-2 = Child Concentration Inventory 2nd Edition; CR = clinician-reported. CV = convergent validity. DEP = depression. DV = discriminant validity. Dx = diagnosed. EF = executive functioning. EFA = exploratory factor analysis. F = father. FR = father-reported. GPA = grade point average. HI = hyperactivity-impulsivity. IN = inattention. INT = internalizing symptoms. IR = adult informant-report (e.g., parent, romantic partner, roommate). K-SCT = Kiddie Sluggish Cognitive Tempo Scale. M = mean. M = mother. MR = mother-reported. P = parent-report. PCA = principal components analysis. PR = parent-reported. PT = primary teacher. S = adult self-report. SR = self-reported. Sx = symptoms. SCT = sluggish cognitive tempo. SD = standard deviation. SR = self-reported. T = teacher-reported. TA = teacher aide. TR = teacher-reported. Tx = treatment.

All studies reporting norms have been conducted based on nationally representative samples in the United States.

Key findings are reported in this table; for additional details, see individual studies in Table S1.

Only primary findings, focused on unique effects of incremental validity (typically controlling for ADHD-IN but sometimes demographics or other psychopathology dimensions), are included in this table given space considerations.

Only primary findings, focused on unique effects (typically controlling for ADHD-IN but sometimes demographics or other psychopathology dimensions), are included in this table given space considerations.

All measures identified for this review were developed in English (in Canada and the United States), and so only studies conducted in other countries are included in the transcultural validity column.

Information for the Penny SCT Scale is based on studies using the original 14-item scale; for studies using a modified Penny scale with a smaller item set, see Table S1.

Structural validity (construct validity).

All nine measures had at least a subset of items that demonstrated structural validity. That is, studies have examined whether the SCT had high loadings on an SCT factor (convergent validity) and low loadings on an ADHD-IN factor or other factor (discriminant validity). See Table 3 and Table S1, available online, for details.

In considering parent/teacher ratings of SCT, one study has examined the structural validity of the K-SCT.26 In a sample of children with ADHD predominantly inattentive type, 15 SCT items from an initial pool of 44 items comprised the final K-SCT measure.26 Three studies have examined the structural validity of the CABI, with consistent findings across community-based and nationally-representative studies conducted in the United States and Spain and using both parent (mother and father) and teacher informants.29,30,33 Studies using the CADBI, a predecessor to the CABI, found a smaller SCT item set to demonstrate structural validity in community samples across parent (mother and father) and teacher informants in Spain34 compared to the original validation study of parent and teacher ratings in the United States28 and studies in Chile35 and Nepal.36 The structural validity of the BSCTS-CA has been examined in two studies, with slightly different SCT subscales in the original validation study of a nationally representative sample of children and adolescents in the United States23 and a subsequent study in Turkey.37,38 Similarly, the Penny SCT Scale has demonstrated different findings in the original community sample20 and a subsequent clinic-referred sample.39 Of note, both studies examining the structural validity of the Penny measure found that a number of the retained SCT items (assessing slow task completion, apathy, low motivation, lacking initiative, effort on tasks fading quickly, and needing extra time for assignments) to load with ADHD-IN.20,39 For this reason, some recent studies40–42 have used a modified Penny measure using only the items from the scale that were found to be strong SCT items in the 2016 meta-analysis1 (see Table S1, available online, for details).

In considering youth self-report ratings of SCT, the CCI-2 has been examined in two studies. In a large community sample of Spanish children, 15 CCI-2 items loaded strongly on the SCT factor.25 A subsequent study of adolescents with and without ADHD in the United States found 13 of the 15 CCI-2 items demonstrate discriminant validity from adolescent self-reported ADHD-IN.43 One study has examined the structural validity of the CCI,24 the predecessor to the CCI-2, finding CCI scores to be distinct from teacher-rated ADHD inattention as well as child-rated anxiety and depression in a study of school-aged children. The self-report version of the Penny scale has been shown to be empirically distinct from self-reported anxiety, depression, and daytime sleepiness in adolescents with ADHD.44 No study was identified that has examined whether the SCT items on the self-report version of the Penny scale demonstrate discriminant validity from self-reported ADHD inattention items.

In considering adult self-report of SCT, the structural validity of the ACI has been examined in one study which found 10 SCT items to be empirically distinct from both ADHD inattention and internalizing symptoms in a large sample of college students.22 The structural validity of the BAARS-IV has been examined in four studies.27,45–47 First, in a nationally representative sample of United States adults, 9 SCT items were distinct from ADHD symptom dimensions.27 In a sample of college students, the BAARS-IV SCT scale was shown to be distinct from ADHD dimensions45 and daytime sleepiness.46 In contrast, a study of adults in Japan found 5 of the 9 BAARS-IV SCT items to be empirically distinct from ADHD inattention items.47

Dimensionality of SCT.

As summarized in Tables 2 and 3 (with study-specific details provided in Table S1, available online), six of the nine included scales report and/or recommend a single, total SCT score be used. This includes the ACI and BAARS-IV adult self-report measures, the CCI and CCI-2 youth self-report measures, and the parent/teacher-report CABI and CADBI. However, there have been studies that examined SCT items in isolation of other psychopathology items and identified subscales for the self- and collateral-report versions of the BAARS-IV31 and the parent-report version of the CADBI.48

The other three measures (BSCTS-CA, K-SCT, Penny) reported a two- or three-factor structure of SCT, with each measure finding support for a daydreaming and sluggish/sleepy factor. The K-SCT also found support for a working memory problems factor, including items related to mental confusion and losing train of thought.26 The Penny measure has found support for a Slow/Low Initiative factor with items that generally load with ADHD-IN as opposed to on a distinct SCT factor.20,39

Reliability.

Identified studies reported on measures’ internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and inter-rater reliability.

Internal consistency.

Internal consistency reliability has been examined for all nine SCT measures, and all measures and their scores (total scores and, if applicable, subscales) demonstrated adequate internal consistency (all >.70 and most >.80; see Table 3).

Test-retest reliability.

As summarized in Table 3, test-retest reliability has been reported for six of the nine SCT measures. The BAARS-IV, BSCTS-CA, CABI, CADBI, and CCI-2 each had acceptable test-retest reliability (>.70) over time periods ranging from one to six weeks. The parent version of the Penny SCT scale total score and subscales also had high test-retest reliability over a 12-week period.20 In addition, although not a direct measure of test-retest reliability, findings with the CADBI indicate that SCT is more trait-like than state-like.49

Inter-rater reliability.

Inter-rater reliability has been reported for all of the SCT measures, as summarized in Table 3 and detailed in Table S1, available online. High inter-rater reliability has been found for within-setting informants (e.g., fathers with mothers, primary teachers with teachers’ aides) and small-to-moderate inter-rater reliability has been found for across-setting informants (e.g., parents with teachers). Moderate-to-large inter-rater reliability has also been found for self-reported SCT with other informants (e.g., parent-report with youth self-report; adult self-report with collateral-informant report).

The extant inter-rater reliabilities also offer some evidence of associations between different SCT measures (see Table S1, available online). Studies have found parent- and teacher-reported SCT on the CABI to be moderately-to-strongly correlated with youth self-reported SCT on the CCI-2.25,50,51 Teacher ratings on the Penny SCT scale have also been found to be moderately-to-strongly correlated with youth self-report ratings on the CCI.24,42 No studies were identified that included different SCT measures completed by the same informant.

External Validity

Table 3 also summarizes evidence for the external validity of the nine SCT measures. Only primary findings, focused on unique effects of incremental validity (typically controlling for ADHD-IN but sometimes demographics or other psychopathology dimensions), are reviewed in this section and in Table 3 given space considerations and the importance of establishing unique associations beyond bivariate correlations.

Cross-sectional associations.

Collectively, the SCT measures have been examined in relation to a range of functioning domains, typically by evaluating incremental validity in whether SCT symptoms are uniquely associated with functioning above and beyond ADHD-IN symptoms (and sometimes other psychopathology dimensions also). As summarized in Table 3, studies most consistently find SCT to be uniquely associated with higher internalizing problems (e.g., anxiety, depression, suicidal ideation),20,22,24,26,28–30,32,34–36,38,43,45,47,52–58 lower externalizing problems (e.g., hyperactivity-impulsivity, oppositional defiant disorder symptoms),20,28–30,33,34,36,47,53,55–59 and more social difficulties (e.g., global social impairment, withdrawal, conflicted shyness).24,26,28–30,33,36,38,42,53,54,58–60 Although examined in fewer studies, there is some indication that SCT is uniquely related to greater emotion dysregulation,22,24,43,61 loneliness,22,25 and sleep difficulties/daytime sleepiness,46,62,63 again above and beyond the contribution of other psychopathologies examined. Findings are more mixed for whether or not SCT is uniquely associated with academic functioning, daily life executive functioning, or task-based neurocognitive performance (see Table 3 and Table S1, available online).

Studies examining SCT subscales have reported mixed findings.26,58,64 Using the K-SCT, across both parent and teacher ratings, SCT sleepy/tired symptoms were uniquely associated with increased depressive symptoms and more organizational problems, whereas SCT daydreams symptoms were uniquely associated with increased global impairment.26 One study examining two SCT factors on the CADBI found SCT inconsistent alertness symptoms were uniquely associated with increased peer problems whereas SCT slowness symptoms were uniquely related to greater depressive symptoms and learning problems.58 Among studies examining the Penny measure subscales, the most consistent finding across samples and informants has been a unique association between SCT slow/low initiation symptoms and poorer academic functioning,39,64–67 though as noted above the Penny SCT slow/low initiation symptoms have not demonstrated discriminant validity from ADHD-IN symptoms. A study examining the youth self-report version of the Penny measure found all three SCT subscales to be uniquely associated with increased anxiety symptoms, whereas the SCT slow and daydreamer subscales were uniquely associated with increased depressive symptoms.64

Longitudinal associations.

As summarized in Table 3 and detailed in Table S1, available online, studies using the CADBI have generally found parent- and teacher-rated SCT to uniquely predict higher depressive symptoms, academic impairment, and social impairment one year54,57 and two years68 later. A study with teachers in Nepal also found teacher-rated CADBI scores to predict higher depression and impairment scores one month later.36 Studies using a modified Penny scale have found teacher-rated SCT to predict increased internalizing symptoms,41 peer impairment,69 and poorer student-teacher relationship quality42 across a school year (see Table S1, available online, for details). Longitudinal external validity remains unexamined for the other SCT measures.

Intervention and Experimental Findings

Only two studies have examined the SCT measures in intervention trials, both in samples of youth with ADHD. Using the parent-report K-SCT, lower SCT scores were associated with higher rates of positive response to behavioral treatment, though the effect size for SCT was smaller compared to other variables examined and was therefore removed from subsequent analyses.10 Using the Penny measure, parent-reported, but not adolescent-reported, SCT symptoms decreased following school-based behavioral intervention.70

Two experimental studies using randomized sleep protocols have found lower SCT symptoms during extended sleep conditions compared to shorter sleep conditions using the CCI71 and CCI-250 and the parent-report CABI.50 See Table 3 and Table S1, available online, for details.

Invariance

Table 3 summarizes evidence for invariance of the nine SCT measures. Studies using the BAARS-IV, parent and teacher CABI, CCI-2, and youth self-report version of the Penny measure have demonstrated that SCT is invariant across sex.30,33,43–45 The self-report version of the Penny measure was also invariant across older/younger youth and ADHD presentation (combined or predominantly inattentive),44 but not with parent ratings on the Penny measure.62 The CABI and CADBI have also demonstrated invariance across mother, father, and teacher ratings,29,34 with the CADBI also having invariance across primary teachers and teaching aides34 and across a one-year period.49 The CCI-2 has also demonstrated invariance across adolescents with and without ADHD.43

Normative Data

As indicated in Table 3, the adult self-report BAARS-IV27 and the parent-report versions of the BSCTS-CA23 and CABI30 measures currently have normative data based on nationally-representative samples in the United States. No study was found presenting normative data for teacher-report or youth self-report of SCT.

Discussion

Findings from this systematic review demonstrates that substantial work has been done in the past decade to develop and validate rating scale measures for assessing SCT. Scales to assess parent and teacher perceptions of children’s SCT symptoms, as well as self-perceptions using youth or adult self-report scales, have all been developed and examined. Collectively, these measures have promising psychometric support and have proven useful for examining the external correlates of SCT across the life span.

Before making recommendations for research and practice, it is important to note that the measures include in this review share numerous positive properties. To the extent that studies have examined reliability, each measure has demonstrated acceptable to excellent reliability, including internal consistency, test-retest, and inter-rater reliability. All or at least the majority of items on each measure also have structural validity with ADHD-IN items. Studies have supported the invariance of SCT across sex and time, and there is also initial evidence of invariance across informants, youth with and without ADHD, and ADHD presentations. Across the various measures, SCT symptoms are uniquely associated with greater internalizing problems, fewer externalizing problems, and increased social difficulties, with emerging empirical support linking SCT to numerous other domains. Studies examining the factor structure and external correlates in different countries and continents have also reported largely similar findings. As detailed below, although much work remains to be done, tremendous progress in the assessment of SCT has been made over the last decade.

In considering the various measures for assessing SCT in children, the CABI and CCI-2 appear to have the strongest support for parent/teacher-reported and youth self-reported SCT, respectively. Both are based on the SCT items found to have strong empirical support in a meta-analysis,1 have strong psychometric properties (including examination of reliability and invariance), have been used with the largest number of participants, and have been examined in multiple countries. The mother-report CABI also has normative data based on a nationally representative sample of U.S. children (ages 4–13 years).30 The only other parent-report scale with normative data (ages 6–17 years) is the BSCTS-CA, which also has strong psychometric properties and has been used in multiple countries. The BSCTS-CA was developed as a parent-report measure, but a teacher-report version has also been used.72 Although additional studies are needed to examine the structural validity of the BSCTS-CA and to examine invariance, particularly with the teacher version, the BSCTS-CA is another strong measure for assessing SCT in children. In addition, if a clinician or researcher is particularly interested in SCT subscales, either the BSCTS-CA or K-SCT are good options, as both include subscales that have shown discriminant validity from ADHD-IN items.

In considering the two measures for assessing SCT in adults, the BAARS-IV has the strongest support. The BAARS-IV has strong psychometric properties (including examination of reliability and invariance across sex), has been examined in numerous samples, sample types, and countries, and has normative data based on the self-report version collected in a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults. The BAARS-IV also has a collateral-informant version that has begun to be used.31,32 If an investigator or clinician is interested in adult self-report of SCT that has structural validity with both ADHD-IN and internalizing symptoms, the ACI is a good option as it was first developed based on SCT items supported by meta-analysis, though studies are needed that further examine the ACI particularly in non-college student samples.

A key question for the study of SCT has been whether there are subdimensions within the SCT construct. There is not yet an agreed-upon symptom set for defining the SCT construct and, as such, the identified measures vary in their number of items and item content. It is therefore difficult to draw firm conclusions regarding the nature and validity of SCT subdimensions. Six of the measures included in this review do not have subscales, whereas three measures do. Across these three measures, the subscales identified focus on daydreaming, sleepy/sluggish behaviors, mental confusion/losing train of thought, and low motivation/initiative. Items for the low motivation/initiative subscale seem to clearly load with ADHD-IN as evidenced by original factor analytic studies,20,23,39 meta-analytic findings,1 and more recent investigations.29,30,33,73 Of note, the low motivation/initiative factor has also been the SCT subscale to be most consistently associated with poorer academic functioning. This has unfortunately created some confusion for the field, as studies (including some by this author) have concluded that the low motivation/initiative subdimension of SCT is uniquely related to academic functioning even though the items comprising this subdimension are not optimal for defining the SCT construct as distinct from ADHD. It is therefore recommended that studies assessing SCT remove items or subscales that have consistently failed to demonstrate discriminant validity from ADHD-IN items (for examples of studies taking this approach, see40–42).

An ancillary finding of this systematic review is that a large number of studies continue to use the brief CBCL/TRF scales to assess SCT. This may be reasonable, as many studies included the CBCL/TRF and only later was there specific interest in SCT. Although it would certainly be best for a study focused on SCT to include one of the scales identified in this review, that is not always possible, especially for archival, ongoing, or large datasets. In those instances, the CBCL/TRF SCT scale could be useful, as the correlates of SCT appear to be similar when the CBCL/TRF SCT scale or a more comprehensive SCT scale is used. However, it is important for researchers and clinicians to keep in mind that the CBCL/TRF SCT scale does not cover the full range of currently-established SCT item content, particularly items assessed slowed/sleepy behaviors (see Table 1 note), and studies have yet to test whether the CBCL/TRF SCT scales have associations with external correlates of a similar magnitude as an SCT scale with more comprehensive item content.

There are many directions for further work in the assessment of SCT. First, as indicated in Table 1, there is variability among existing measures for the item content used to assess SCT. The field would greatly benefit by arriving at a standard symptom set that can be used across studies, allowing for clearer comparisons across studies. There may be benefit for studies that examine larger item pools that can establish what might be an agreed-upon symptom set based on both conceptualizations of SCT and empirical data. Second, very few studies have included multiple SCT measures, which would allow for examining the strength of associations among SCT measures, whether associations with external correlates are similar when different SCT measures are used in the same sample, and whether certain measures are preferable for assessing SCT in clinical (e.g., ADHD) or nonclinical samples. Third, few studies have examined which informant(s) may be best when assessing SCT. There is some indication that teacher-rated SCT may be more consistently linked than parent-rated SCT to other psychopathology dimensions and impairment,34 and collateral report may be less biased74 and especially important for examining SCT-related impairments in adults.31 Studies are needed that not only examine whether different informant ratings of SCT have similar external correlates, but also the incremental validity of including ratings from certain informants or informant combinations. Fourth, there is a need for studies that examine other domains of psychometrics, including sensitivity/specificity, item response theory, and responsiveness to detecting change over time. Fifth, very few studies have used the identified measures to examine the longitudinal validity of SCT, and even fewer studies have sought to identify longitudinal predictors of SCT. Sixth, the field would benefit from continued expansion of predictor and criterion variables examined in relation to SCT. To name a few, there remains a need to evaluate SCT with objective measures of sleep (e.g., actigraphy, polysomnography) and daytime sleepiness (e.g., multiple sleep latency test), performance measures of attentional lapses (e.g., reaction time variability indicators) and temporal processing (e.g., duration reproduction, duration discrimination, and finger tapping tasks), motor function (e.g., fine and gross motor skills and visual-motor integration), and brain networks linked to daydreaming and introspection (e.g., default mode network). Seventh, although SCT has been examined in multiple countries, no more than three studies have been conducted in any countries besides South Korea, Spain, Turkey, and the United States, with no studies at all conducted in Africa or Australia and only one in South America. Further, no study has used a cross-cultural approach or used the same study design simultaneously in different cultural contexts (either across countries or varied contexts within countries), and this will be necessary for establishing the transdiagnostic validity and possible cultural nuances of SCT.75 Eighth, although SCT is increasingly studied in clinical populations beyond ADHD, the existing studies are limited (e.g., none have been conducted in samples recruited for depression or anxiety) and none have used carefully-validated measures of SCT. Ninth, there is a clear need for additional research examining whether SCT improves with existing interventions or predicts treatment response. Tenth, although studies using nationally representative U.S. samples have provided normative data for parent- and adult self-reported SCT, no norms exist for any teacher-report or youth self-report measure of SCT. Gathering additional representative data of SCT would be highly useful to help understand the distribution and nature of SCT.

Until these and other areas for further work are undertaken, pressing questions to guide theory and clinical care will remain unanswered. At the core, the sound assessment of SCT is a prerequisite to advance our field’s understanding of what precisely SCT is. Only by examining SCT with reliable and valid measures will we then be able to further determine whether SCT should be a distinct disorder, diagnostic specifier, or transdiagnostic construct; whether SCT represents in large or small part sleep disturbances, motivational processes, neurological insult or traumatic brain injury, or a subclinical indicator of other mental health problems (e.g., subclinical depression); whether the cognitive (e.g., daydreaming) and motoric (e.g., sluggish) aspects of SCT have distinct etiologies, developmental pathways, and correlates; and whether existing treatments or new treatments can make an impact on SCT symptoms and associated impairments.

There have been recent advances in these areas to provide directions for further investigations. For instance, it has been hypothesized that SCT may represent a form of mind wandering or ruminative thought,18,19,76 and recent studies have found SCT to be more clearly linked than ADHD symptoms to self-reported mind wandering.77,78 Studies are needed that use psychometrically-validated measures of SCT to examine brain function including the executive circuit and default mode network. Further, such work may inform clinical recommendations based on behavioral phenotype, as it has been suggested that cognitive-behavioral and mindfulness-based interventions may be effective for treating children displaying SCT symptoms.18,79 These and other treatment approaches may be important to consider if additional studies replicate recent findings that children with ADHD and co-occurring SCT symptoms have a poorer response to methylphenidate.6,7 But for these and other lines of inquiry to advance, careful measurement of SCT is crucial to provide a foundation for understanding and comparing research findings.

In light of these areas for further work, the present review indicates that there are numerous rating scale measures well-suited for assessing SCT across informants and across the life span. These measures should prove useful for further examination of the etiology, course, correlates, and clinical relevance of the SCT construct.

Supplementary Material

Disclosure:

Dr. Becker has received grant funding from the Institute of Education Sciences, US Department of Education, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the Cincinnati Children’s Research Foundation. He has received book honoraria from Guilford Press. He is an author or co-author on several of the measures reviewed in this manuscript, though he has received no financial benefit from these measures as they are freely available.

Dr. Becker is supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; K23MH108603) and the Institute of Education Science (IES; R305A160064, R305A160126, R305A200028). The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) or the US Department of Education.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Becker SP, Leopold DR, Burns GL, et al. The internal, external, and diagnostic validity of sluggish cognitive tempo: A meta-analysis and critical review. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;55:163–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Becker SP, Marshall SA, McBurnett K. Sluggish cognitive tempo in abnormal child psychology: an historical overview and introduction to the special section. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2014;42:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Milich R, Balentine AC, Lynam DR. ADHD combined type and ADHD predominantly inattentive type are distinct and unrelated disorders. Clinical Psychology-Science and Practice. 2001;8:463–488. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Todd RD, Rasmussen ER, Wood C, Levy F, Hay DA. Should sluggish cognitive tempo symptoms be included in the diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:588–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harrington KM, Waldman ID. Evaluating the utility of sluggish cognitive tempo in discriminating among DSM-IV ADHD subtypes. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2010;38:173–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Froehlich TE, Becker SP, Nick TG, et al. Sluggish cognitive tempo as a possible predictor of methylphenidate response in children with ADHD: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fırat S, Gul H, Aysev A. An open-label trial of methylphenidate treating sluggish cognitive tempo, inattention, and hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms among 6- to 12-year-old ADHD children: What are the predictors of treatment response at home and school? J Atten Disord. 2020:1087054720902846. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.McBurnett K, Clemow D, Williams D, Villodas M, Wietecha L, Barkley R. Atomoxetine-related change in sluggish cognitive tempo is partially independent of change in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder inattentive symptoms. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2017;27:38–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wietecha L, Williams D, Shaywitz S, et al. Atomoxetine improved attention in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and dyslexia in a 16 week, acute, randomized, double-blind trial. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2013;23:605–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Owens EB, Hinshaw SP, McBurnett K, Pfiffner L. Predictors of response to behavioral treatments among children with ADHD-inattentive type. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2018;47:S219–S232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duncan A, Tamm L, Birnschein AM, Becker SP. Clinical correlates of sluggish cognitive tempo in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2019;23:1354–1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reinvall O, Kujala T, Voutilainen A, Moisio AL, Lahti-Nuuttila P, Laasonen M. Sluggish cognitive tempo in children and adolescents with higher functioning autism spectrum disorders: Social impairments and internalizing symptoms. Scand J Psychol. 2017;58:389–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McFayden T, Jarrett MA, White SW, Scarpa A, Dahiya A, Ollendick TH. Sluggish cognitive tempo in autism spectrum disorder, ADHD, and their comorbidity: Implications for impairment. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2020:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Becker SP, Garner AA, Byars KC. Sluggish cognitive tempo in children referred to a pediatric Sleep Disorders Center: Examining possible overlap with sleep problems and associations with impairment. J Psychiatr Res. 2016;77:116–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Musicaro RM, Ford J, Suvak MK, Sposato A, Andersen S. Sluggish cognitive tempo and exposure to interpersonal trauma in children. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2020;33:100–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahdavi S, Hasper E, Donders J. Sluggish cognitive tempo in children with traumatic brain injuries. Appl Neuropsychol Child. 2019:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Becker SP, Willcutt EG. Advancing the study of sluggish cognitive tempo via DSM, RDoC, and hierarchical models of psychopathology. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;28:603–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Becker SP, Barkley RA. Sluggish cognitive tempo. In: Banaschewski T, Coghill D, Zuddas A, eds. Oxford textbook of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2018:147–153. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barkley RA. Sluggish cognitive tempo (concentration deficit disorder?): current status, future directions, and a plea to change the name. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2014;42:117–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Penny AM, Waschbusch DA, Klein RM, Corkum P, Eskes G. Developing a measure of sluggish cognitive tempo for children: content validity, factor structure, and reliability. Psychol Assess. 2009;21:380–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mueller AK, Tucha L, Koerts J, Groen Y, Lange KW, Tucha O. Sluggish cognitive tempo and its neurocognitive, social and emotive correlates: A systematic review of the current literature. J Mol Psychiatry. 2014;2:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Becker SP, Burns GL, Garner AA, et al. Sluggish cognitive tempo in adults: Psychometric validation of the Adult Concentration Inventory. Psychol Assess. 2018;30:296–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barkley RA. Distinguishing sluggish cognitive tempo from ADHD in children and adolescents: Executive functioning, impairment, and comorbidity. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2013;42:161–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Becker SP, Luebbe AM, Joyce AM. The Child Concentration Inventory (CCI): Initial validation of a child self-report measure of sluggish cognitive tempo. Psychol Assess. 2015;27:1037–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sáez B, Servera M, Burns GL, Becker SP. Advancing the multi-informant assessment of sluggish cognitive tempo: Child self-report in relation to parent and teacher ratings of SCT and impairment. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2019;47:35–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McBurnett K, Villodas M, Burns GL, Hinshaw SP, Beaulieu A, Pfiffner LJ. Structure and validity of sluggish cognitive tempo using an expanded item pool in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2014;42:37–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barkley RA. Distinguishing sluggish cognitive tempo from attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults. J Abnorm Psychol. 2012;121:978–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee S, Burns GL, Snell J, McBurnett K. Validity of the sluggish cognitive tempo symptom dimension in children: Sluggish cognitive tempo and ADHD-inattention as distinct symptom dimensions. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2014;42:7–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sáez B, Servera M, Becker SP, Burns GL. Optimal items for assessing sluggish cognitive tempo in children across mother, father, and teacher ratings. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2019;48:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burns GL, Becker SP. Sluggish cognitive tempo and ADHD symptoms in a nationally representative sample of U.S. children: Differentiation using categorical and dimensional approaches. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Lunsford-Avery JR, Kollins SH, Mitchell JT. Sluggish Cognitive Tempo in Adults Referred for an ADHD Evaluation: A Psychometric Analysis of Self- and Collateral Report. J Atten Disord. 2018:1087054718787894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Kamradt JM, Momany AM, Nikolas MA. Sluggish cognitive tempo symptoms contribute to heterogeneity in adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Psychopathology & Behavioral Assessment. 2018;40:206–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Becker SP, Burns GL, Schmitt AP, Epstein JN, Tamm L. Toward establishing a standard symptom set for assessing sluggish cognitive tempo in children: Evidence from teacher ratings in a community sample. Assessment. 2019;26:1128–1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burns GL, Becker SP, Servera M, Bernad MD, Garcia-Banda G. Sluggish cognitive tempo and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) inattention in the home and school contexts: Parent and teacher invariance and cross-setting validity. Psychol Assess. 2017;29:209–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Belmar M, Servera M, Becker SP, Burns GL. Validity of sluggish cognitive tempo in South America: An initial examination using mother and teacher ratings of Chilean children. J Atten Disord. 2017;21:667–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khadka G, Burns GL, Becker SP. Internal and external validity of sluggish cognitive tempo and ADHD inattention dimensions with teacher ratings of Nepali children. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2016;38:433–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Firat S, Bolat GU, Gul H, et al. Barkley Child Attention Scale Validity and Reliability Study. Dusunen Adam-Journal of Psychiatry and Neurological Sciences. 2018;31:284–293. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Firat S, Gul H, Aysev A. Distinguishing SCT Symptoms from ADHD in Children: Internal and External Validity in Turkish Culture. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2019;41:716–729. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jacobson LA, Murphy-Bowman SC, Pritchard AE, Tart-Zelvin A, Zabel TA, Mahone EM. Factor structure of a sluggish cognitive tempo scale in clinically-referred children. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2012;40:1327–1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yung TWK, Lai CYY, Chan JYC, Ng SSM, Chan CCH. Neuro-physiological correlates of sluggish cognitive tempo (SCT) symptoms in school-aged children. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;29:315–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Becker SP, Webb KL, Dvorsky MR. Initial examination of the bidirectional associations between sluggish cognitive tempo and internalizing symptoms in children. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Holdaway AS, Becker SP. Sluggish cognitive tempo and student-teacher relationship quality: Short-term longitudinal and concurrent associations. Sch Psychol Q. 2018;33:537–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Becker SP, Burns GL, Smith ZR, Langberg JM. Sluggish cognitive tempo in adolescents with and without ADHD: Differentiation from adolescent-reported ADHD inattention and unique associations with internalizing domains. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2020;48:391–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith ZR, Eadeh HM, Breaux RP, Langberg JM. Sleepy, sluggish, worried, or down? The distinction between self-reported sluggish cognitive tempo, daytime sleepiness, and internalizing symptoms in youth with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychol Assess. 2019;31:365–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Becker SP, Langberg JM, Luebbe AM, Dvorsky MR, Flannery AJ. Sluggish cognitive tempo is associated with academic functioning and internalizing symptoms in college students with and without attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Psychol. 2014;70:388–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Langberg JM, Becker SP, Dvorsky MR, Luebbe AM. Are sluggish cognitive tempo and daytime sleepiness distinct constructs? Psychol Assess. 2014;26:586–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takeda T, Burns GL, Jiang Y, Becker SP, McBurnett K. Psychometric properties of a sluggish cognitive tempo scale in Japanese adults with and without ADHD. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord. 2019;11:353–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fenollar Cortes J, Servera M, Becker SP, Burns GL. External Validity of ADHD Inattention and Sluggish Cognitive Tempo Dimensions in Spanish Children With ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2017;21:655–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Preszler J, Burns GL, Litson K, Geiser C, Servera M, Becker SP. How consistent is sluggish cognitive tempo across occasions, sources, and settings? Evidence from latent state-trait modeling. Assessment. 2019;26:99–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Becker SP, Epstein JN, Tamm L, et al. Shortened sleep duration causes sleepiness, inattention, and oppositionality in adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Findings from a crossover sleep restriction/extension study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;58:433–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Becker SP, Marsh NP, Holdaway AS, Tamm L. Sluggish cognitive tempo and processing speed in adolescents with ADHD: Do findings vary based on informant and task? Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Becker SP, Holdaway AS, Luebbe AM. Suicidal behaviors in college students: Frequency, sex differences, and mental health correlates including sluggish cognitive tempo. J Adolesc Health. 2018;63:181–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Servera M, Saez B, Burns GL, Becker SP. Clinical differentiation of sluggish cognitive tempo and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children. J Abnorm Psychol. 2018;127:818–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Servera M, Bernad MD, Carrillo JM, Collado S, Burns GL. Longitudinal correlates of sluggish cognitive tempo and ADHD-inattention symptom dimensions with Spanish children. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2016;45:632–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]