Abstract

Stem cell transplantation holds a promising future for central nervous system repair. Current challenges, however, include spatially and temporally defined cell differentiation and maturation, plus the integration of transplanted neural cells into host circuits. Here we discuss the potential advantages of neuromodulation-based stem cell therapy, which can improve the viability and proliferation of stem cells, guide migration to the repair site, orchestrate the differentiation process, and promote the integration of neural circuitry for functional rehabilitation. All these advantages of neuromodulation make it one potentially valuable tool for further improving the efficiency of stem cell transplantation.

Keywords: Stem cell, Rehabilitation, Neuromodulation, Transcranial magnetic stimulation, Transcranial direct current stimulation, Deep brain stimulation

Introduction

The stem cell-based approach to brain repair aims to either promote endogenous neurogenesis (e.g. facilitating stem cell proliferation and migration), or to transplant exogenous stem cells directly into the injury site or via the circulation. To date, a few clinical trials have been performed targeting Parkinson’s disease (PD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and ischemic stroke, mainly using neural stem cells [1, 2]. However, a number of challenges have been encountered, mainly due to the inability to re-form functional neural circuits at the damage site [3]. Moreover, stem cell therapy faces other obstacles including specific cell lineage differentiation and maturation. For stem cell therapy to succeed, the transplanted cells must replace the degenerated host neurons, reform the projection pattern, and reconstruct precise synaptic transmission [2]. Unfortunately, engrafted neurons do not always precisely integrate into the host neural circuits and faithfully compensate the function of lost neurons, resulting in unpredictable outcomes and even severe side-effects. Furthermore, grafted neurons frequently exhibit abnormal projections patterns, leading to functional disruption. Therefore, the development of complementary approaches to improve the differentiation and maturation of stem cells is of critical importance to facilitate functional recovery.

To overcome the obstacles faced by stem cell therapy, one possible solution is to use invasive or non-invasive neuromodulation approaches (Table 1), which include deep brain stimulation (DBS), transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), and transcranial ultrasound stimulation (tUS). Neuromodulation of stem cells thus refers to the modulation of the differentiation, maturation, and functional circuit integration of grafted neurons using these neuromodulation approaches. In the following, we revise the accumulating evidence showing how neuromodulation works as a promising strategy to improve the efficiency of stem cell therapy.

Table 1.

Summary of the four brain stimulation techniques

| Stimulation technique | Stimulation location | Stimuli form | Invasive method | Neural mechanism | Clinical application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DBS | Brain regions of interest | High frequency continuous current | Invasive procedures | Release of neurotransmitters locally and throughout the stimulated network, regulation of regional oscillation, balance of excitatory/inhibitory (EI) ratio | PD, essential tremor, dystonia |

| TMS | Cortical regions of interest | Alternating currents | Non-invasive procedures | Dopamine release increased neuronal firing | PD, depressive disorders |

| tDCS | Cortical neural network | Direct current | Non-invasive procedures | Regulation of neurotransmitters, neuronal viability, neuronal morphology, modulates synaptic transmission and biosynthesis of molecules | PD, depressive disorders, addiction, stroke, and other movement disorders |

| tUS | Subcortical and Deep Cortical | Focusing pulsed ultrasound | Non-invasive procedures | Unclear | PD, depressive disorders, stroke |

Principles of neuromodulation

The deep brain stimulation (DBS) system contains one or more electrode lead(s) implanted into the brain parenchyma, along with extension wires tunneled underneath the skin and connected to an implanted pulse generator below the collarbone. DBS commonly applies high-frequency (HF, >100 Hz) continuous current to modulate neural activity [4]. It is proposed that excitatory neurons cannot follow this HF stimulation, and the regional effect of HF DBS is mainly in the form of activating inhibitory networks. For example, stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus (STN) can activate nigrostriatal (by increasing dopamine release), pallidothalamic, cerebellothalamic, and pallidonigral fiber tracts, all of which are associated with the therapeutic effects of DBS [5]. Research has reported that the intervention effect of STN DBS on essential tremor is mainly due to the activation of cerebellothalamic fiber pathways that pass just posterior and ventral to the STN [6, 7]. Therefore, DBS at the STN or globus pallidus internus is routinely applied for late-stage PD patients to improve motor function and balance. The neural mechanisms underlying the therapeutic effects of DBS for PD include but are not limited to the improvement of dopamine release, regulation of regional oscillation, restoration of excitatory/inhibitory balance, and normalization of neural network connectivity [4, 8, 9].

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS)

Is a non-invasive brain stimulation technique, which involves the generation of a brief, high-intensity magnetic field by passing a brief electrical current through a magnetic coil. TMS induces prominently cortical activation by placing a coil over the cortical region of interest, and injecting alternating current to induce a transient but strong magnetic field penetrating the skull, thus generating a circular current on the cortical surface [10]. According to physical laws, the depth of TMS-induced current is in direct proportion to the diameter of the coil. One possible mechanism of TMS is its ability to modulate the expression of genes involved in neural plasticity and neurodegeneration [11]. Repetitive TMS (rTMS) pulses modulate neural plasticity in different ways. For instance, HF (>5 Hz) rTMS induces local excitatory effects (e.g. increased metabolism, enhanced neural activity, and increased neuronal firing) in the stimulated region, while low-frequency (<1 Hz) rTMS modulates regional inhibitory transmission [12]. TMS stimulation also activates deep brain regions [13], such as the facilitation of striatal dopamine release [14, 15]. In particular, the dopaminergic system is the most responsive under TMS, particularly when targeting the frontal cortex. Therefore, TMS can be used to alleviate both motor [16] and mood symptoms of PD, in addition to depressive disorders [17].

Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS)

Is also a non-invasive brain stimulation technique with relatively low cost and more convenient operation. In practice, tDCS induces depolarization (at the cathode) or hyperpolarization (at the anode) of cortical neural networks, without causing direct spikes [18]. Anodal stimulation enhances cortical excitability, while cathodal stimulation reduces it. Similar to rTMS, tDCS also results in network activation, including in deep midbrain regions [19]. The effect of tDCS appears to be multifactorial as it can modulate neural plasticity at both local and distant sites. The physiological changes induced by tDCS involve the regulation of various neurotransmitters such as dopamine, acetylcholine, and serotonin [20], in addition to a number of membrane ion channels. As a result, the after-effects of tDCS are associated with synaptic modulation, such as the potentiation of synaptic glutamate receptors [21]. Furthermore, anodal tDCS has an impact on GABAergic neurotransmission [22]. In the clinic, tDCS has been introduced for treating depressive disorders, addiction, stroke, PD, and other movement disorders [23].

Transcranial ultrasound stimulation (tUS)

A novel tool in the non-invasive neurostimulation toolbox, can effectively stimulate and reversibly inhibit neuronal activity in the brain by generating focused pulsing ultrasound waves [24, 25]. The neural mechanism underlying tUS remains unknown, but it has been proposed to modulate specific membrane ion channels or change membrane capacitance that may contribute to neuronal activation. The advantages of tUS stimulation include: (1) non-invasive application compared to DBS; (2) higher spatial resolution than other noninvasive techniques; and (3) site-specific activation of deep brain regions without affecting the overlaying cortex [24–27]. To date, few clinical trials have been deployed using tUS to treat psychiatric diseases, although the neuromodulation effect on cortical regions has been investigated [28, 29].

Modulatory effects on neural stem cells in vitro

Stem cell-based neural regeneration may benefit patients suffering from central nervous injuries, neurodegenerative diseases, or mental illnesses. Recent discoveries have suggested the possible effects of neuromodulation techniques on cultured human neural stem cells (NSCs). For example, electrical fields (EFs) have been used to promote the proliferation and differentiation of NSCs in vitro and to guide their migration and integration into circuitry [30]. In general, EFs guide axonal growth and induce directional cell migration, whereas electromagnetic fields (EMFs) promote neurogenesis and facilitate the differentiation of NSCs into functional neurons [30]. Both the safety and effectiveness of EF treatment have been demonstrated in the neurorehabilitation of spinal cord injury in humans [31]. Recent research suggests that EFs may be developed to improve brain repair by facilitating the proliferation or survival of NSCs [32], or by directing their migration to the injured brain regions for functional replacement [33].

EFs have been found to modulate the direction and velocity of stem cell migration in vitro [34]. Specifically, direct current EFs guide the migration of human embryonic stem cells toward the cathode [35]. The strength of EFs, on the other hand, regulates the migration distance. For example, when the intensity of EFs is increased from 50 mV/mm to 100 mV/mm, the migration distance is remarkably increased [36]. A similar phenomenon occurs when applying EFs to NSCs, whose migration rate is regulated in a voltage-dependent manner [32]. In sum, the direction and intensity of EFs largely determines the migration pattern of NSCs in vitro, and thus similar phenotypes may be expected when using in vivo electrical stimulation.

When investigating the mechanism for EF-directed cell migration, the primary effect can be attributed to the direct attraction/repulsion force depending on the electrical property, since NSCs generally carry negative charges on the cell surface. The application of EFs also facilitates the migration of embryonic stem cell-derived neural cells toward the cathode [36]. Alternatively, EFs probably affect cell migration via specific ligand binding. For example, the application of direct EFs attracts stem cell migration to the cathode, potentially through chemokine receptor signaling [e.g. chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4)], neurotrophic factors, or Wnt signaling pathways [37].

Besides cell migration, EFs also facilitate stem cell differentiation in vitro. One study reported that HF (100 Hz) direct current pulse stimulation increases the differentiation and process formation of mouse cortical neural progenitor cells [38]. In a similar manner, a 115 V/m direct current EF facilitates the differentiation of neural precursor cells into neurons but not astrocytes or oligodendrocytes [39]. It has been found that EFs facilitate neural differentiation as well as the maturation of neural progenitor cells via the interferon-gamma pathway [40]. On the other hand, electrical stimulation helps to protect NSCs and precursors from apoptosis via modulating the PI3K/Akt pathway [41]. When examining neural processes, direct current but not alternating current EFs also increased the length of Tuji1- and MAP2-positive neurites [42]. As a result, direct current EFs have been widely used to facilitate neurite growth after nerve injury or ischemia [43]. In sum, EFs can affect different aspects of NSC development, including cell proliferation, migration, and differentiation. It thus may be expected that EFs can be developed to guide the in vivo migration of NSCs into injured brain sites to exert neural functions.

In addition to EFs, magnetic field stimulation also modifies the behavior of cultured stem/progenitor cells. For instance, a static magnetic field (3–50 mT) increases cell proliferation and facilitates cell differentiation into the osteogenic lineage from bone marrow (BM)-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) [44]. In oligodendrocyte progenitor cells, a static magnetic field (300 mT) promotes oligodendrocyte differentiation via neurotrophic signaling such as brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) or neurotrophin-3 [45]. On the other hand, a static magnetic field (100 mT) suppresses cell proliferation without causing the death of neural progenitor cells, and increases the expression of pro-neuronal genes [46], suggesting its potency in facilitating neuronal differentiation. In rat hippocampal CA1 and CA3, HF rTMS (20 Hz) elevates the expression of BDNF, and activates the ERK pathway [47, 48]. Moreover, an epigenetic mechanism has also been suggested as micorRNA-106b-25 might be mediated by rTMS to facilitate NSC proliferation [49]. In sum, magnetic fields effectively modulate the proliferation and differentiation of NSCs, making this a promising approach for neuromodulation.

It has further been noted that EMFs can have different effects on stem cells. For example, 1 mT and 50 Hz (sinusoidal) low-frequency EMF promotes the neurogenic fate of BM-MSCs without decreasing cell viability [50, 51]. In addition, pulsed EMFs at 1.5–1.8 mT/15 Hz also promote neurogenic, adipogenic, and osteogenic fates of BM-MSCs [52, 53]. Both stimulatory and inhibitory effects on proliferation and viability have been reported using EMF stimulation with different parameters. In addition, EMFs also modulate the neurite growth of NSCs in vitro, as they significantly enhance the probability of neurite outgrowth, length, and direction in cultured PC12 cells [54]. On the other hand, exposure to a very high frequency EMF (such as 1800 MHz) may impair neurite outgrowth [55]. The underlying molecular pathway responding to EMF stimulation is inconclusive at present, although some studies argue for the upregulation of voltage-gated Cav1 channels to facilitate cell proliferation and differentiation [56]. In short, the neural mechanism of EMF stimuli needs to be elucidated so as to optimize the parameters for modulating NSCs.

Ultrasound stimulation has been found to facilitate the neurogenic differentiation of endogenous NSCs [57] and iPSC-derived NSCs [58]. It has also been proposed that a dual-frequency ultrasound protocol exerts stronger effects than single-frequency ultrasound stimulation, potentially due to its stable cavitation, thus modulating membrane mechano-sensitive ion channels and calcium signals more strongly [59]. So far, ultrasound modulation of NSC behaviors has only been sparsely reported, and more systematic studies are required to improve the efficiency of ultrasound modulation of neurons both in vivo and in vitro.

Targeting endogenous neural stem cells in vivo

Neuromodulation approaches have been employed in therapeutic intervention for multiple neurodegenerative diseases and psychiatric disorders. Beyond the known effect on neural activity modulation, oscillation normalization, and plasticity restoration, brain stimulation also evokes abundant changes in neurotrophic factors, which further modulate the endogenous stem cell niche to trigger dynamic changes of cell proliferation and migration. All these modulatory events may affect the behavior and cellular fates of NSCs in vivo.

In adult mammalian brain, the hippocampus and subventricular zone (SVZ) are the major neurogenic sites, although certain controversies still arise from human studies [60, 61]. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis is considered to be an important neural substrate for therapy against depression and Alzheimer’s disease, while SVZ-derived neurons have been proposed as potential sources for striatum and cortex repair after stroke or traumatic brain injury [62]. Adult neurogenesis is regulated by various neurotransmitters (e.g. GABA, glutamate, dopamine, and serotonin), neuroinflammatory cytokines, and neurotrophic factors [e.g. BDNF and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)] [63]. Neuromodulation approaches thus may influence adult neurogenesis via modulating these molecular substrates.

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) induces the most significant changes in adult neurogenesis when compared to other antidepressant therapies [64]. As a result, the volume of the dentate gyrus is prominently increased in depressed patients after ECT [65]. To provide a possible mechanistic explanation, a recent study reported the role of the rs699947 locus in the promoter region of VEGF [66]. Similar to ECT, DBS at the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, anterior nucleus of the thalamus, the fornix, or the entorhinal cortex also increases hippocampal neurogenesis [67–70]. Recent findings suggest that DBS targeting the anterior nucleus of the thalamus induces neurotransmitter re-specification in dopaminergic cells in the ventral tegmental area [71]. In addition, DBS at the STN of PD animal models also facilitates neurogenesis in both the hippocampus and SVZ [72]. DBS at the STN has also been found to increase SVZ neurogenesis [73] from human post-mortem studies, reflecting the potential involvement of neurogenesis in the intervention for both motor and non-motor symptoms of PD. In sum, electrical stimulation effectively facilitates adult neurogenesis for functional recovery.

In addition to EF application, TMS has been found to enhance adult hippocampal neurogenesis as well [74]. In a rat PD model, rTMS treatment synergistically creates a favorable microenvironment for cell survival through the modulation of neurotrophic/growth factors and anti-/pro-inflammatory cytokines [75]. In a rat model of ischemic stroke, human NSC transplantation combined with rTMS not only remarkably increases neurogenesis and the protein levels of BDNF, but also improves the neural differentiation of transplanted NSCs [76]. Regarding the endogenous NSC reserve, TMS treatment also enhances SVZ neurogenesis [77] by regulating the BDNF signaling pathway [78, 79]. Chronic rTMS has also been found to increase rat hippocampal neurogenesis [74]. When investigating the neural mechanism for such induced neurogenesis, it is likely that these changes are mediated by brain network activation, since TMS pulses are generally focused on cortical areas. Besides neurogenesis, low-intensity TMS has recently been found to promote the survival and differentiation of oligodendrocyte precursors in adult mouse [80], providing an alternative explanation for neural rehabilitation. This evidence elucidates the potency of neuro-restoration from endogenous stem cells by TMS intervention. As one possible future direction, the recent development of a deep TMS coil might facilitate the precise targeting of magnetic pulses to circumventricular areas in the brain.

The facilitation of neurogenesis has been postulated as one important route for the neural mechanisms of tDCS [81]. In a rat stroke model, tDCS treatment boosts neurogenesis and recruits oligodendrocyte precursors to facilitate functional recovery [82]. When examining other types of glial cells, tDCS also exerts modulatory actions. For example, tDCS increases microglial proliferation, in addition to the facilitation of SVZ neurogenesis [83]. Furthermore, in post-stroke rodents, tDCS modulates the activation phenotypes of microglia towards the anti-inflammatory M2 type to enhance neural plasticity [84]. The calcium activity of astrocytes is also potentiated by tDCS stimuli [85]. These effects on neurons and glial cells collectively contribute to neurorehabilitation. However, the specific effects with different polarity and length of stimulation remain to be elucidated.

Besides neurogenesis and gliogenesis, the migration of NSCs is also mediated by neuromodulation approaches. A recent study showed that biphasic monopolar stimulation affects the in vivo migration of neural precursor cells in mouse corpus callosum [86]. Combing all this evidence, it is clear that different approaches of neuromodulation can facilitate neurogenesis in the adult brain via certain molecular mechanisms, thus enhancing the functional recovery of injured brain in vivo. Nevertheless, details of the molecular and circuitry mechanisms for guided neurogenesis have not been systematically studied, and future work is thus needed to improve the efficiency of different neuromodulation therapies.

Modulating transplanted stem cells in vivo

After the pioneering work demonstrating that the striatal dopamine depletion can be replaced by the transplantation of catecholaminergic neurons that leads to functional restoration in a rodent model of PD [87], clinical trials have focused on the use of ventral mesencephalon-derived NSCs with better viability and stronger pluripotency in 6–9 weeks old embryos collected during elective surgical termination of pregnancy [88]. Although these trials show a degree of functional recovery in a subpopulation of patients, clinicians have also identified a series of severe side-effects including uncontrolled movements termed graft-induced dyskinesia [89]. These discouraging outcomes have led to a quiescence in the clinical trials of cell therapy. Therefore, the ability to precisely regulate the proliferation, migration, maturation, and functional replacement of grafted human NSCs are critical for the prospects of cell therapy.

One of major challenges for stem cell transplantation resides in the low survival rate plus uncontrollable differentiation. People have tried to introduce EF stimulation to regulate the behavior of transplanted cells [90]. Independent studies have suggested that electrical stimulation is efficient in boosting stem cell survival and differentiation [91]. In an animal model of peripheral nerve injury, electrical stimulation effectively enhances neural regeneration and axonal remyelination, contributing to better functional recovery [91]. In a similar manner, electrical stimulation has been used in stem cell translation to replace lost hair cells or spiral ganglion neurons, or to achieve better survival and differentiation of transplanted cells [90]. When using human mesenchymal stem cells, the delivery of electric stimuli helps to drive the cell differentiation [43]. In rat brain, electrical guidance of human stem cells facilitates cell migration [92]. These modulations of cell behaviors may eventually translate into functional phenotypes, as low-intensity electrical stimulation of transplanted adipose derived stem cells improves the electromyographic signals in dogs after spinal cord injury [93]. Moreover, electrical stimulation can be combined with other approaches such as gene transduction to further improve the neural differentiation of transplanted stem cells [94]. In future, the optimization of EF parameters may help to improve the behavior of transplanted cells.

TMS treatment facilitates the differentiation of transplanted human NSCs in a rat stroke model [76]. In a second mouse model of intracerebral hemorrhage, rTMS has also been shown to promote NSC proliferation and differentiation [95]. Similar results have been reported when examining functional recovery by introducing human NSCs into rat ischemic stroke models [76]. Those data collectively suggested the therapeutic benefits of combined brain stimulation and stem cell transplantation. To accomplish effective functional recovery, further modulation of transplanted cells is required to guide precise axon growth to form the neural circuits. In general, endogenous progenitor cells migrate according to chemicals, physical forces, and electrical fields [96]. Various studies have suggested that the application of direct current EFs helps to guide the migration of stem cells in vivo [97]. Indeed, implanted electrodes guide the migration of transplanted human NSCs along the rostral migratory route in rat brain [92]. As an alternative approach, non-invasive tDCS also promotes the migration of transplanted neural stem cells in rat brain [98], providing the opportunity to facilitate the localization of transplanted cells towards the repairing site. That is, the neuromodulation approach may help to facilitate cell proliferation, differentiation, and migration of transplanted stem cells, contributing to the better recovery of damaged neural circuits and functions.

After obtaining satisfactory numbers of newly-differentiated cells at the injury site, it is of equal importance to restore the normal excitatory-inhibitory balance in the region, and to reorganize neural circuits for functional recovery [99]. As in the enhancement of cell proliferation and migration, neuromodulation approaches also help to precisely regulate neuronal activity to achieve the homeostatic regulation of synaptic transmission. In human iPSCs expressing channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2), reports have described both local and distant neural activity upon light stimulation using fMRI [100]. In future, more observations of in vivo activity are needed to precisely define the correct route by which neuromodulation can be pursued.

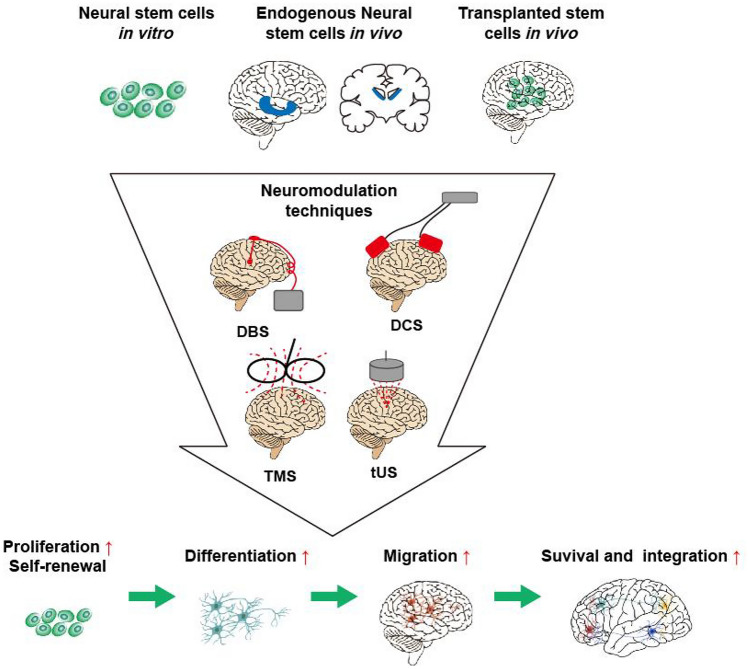

When examining the potential molecular mechanism of electrical/magnetic stimulation on NSC differentiation, epigenetic mechanism may also play a role in addition to the above neurotrophic factors. At the genomic level, a previous study has shown that extremely low-frequency EMFs increase the H3K9 acetylation of proneuronal genes [101]. As for non-coding RNAs, miR-106b has been found to underlie the promotion of the proliferation of neural progenitor cells by rTMS [102]. A similar role of miR-25 has been reported when applying rTMS to facilitate NSC proliferation in a rat model of focal cerebral ischemia [79]. Serum miRNA-let-7 levels have been associated with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in a clinical trial using TMS [103]. Further epigenetic modification events can occur at the protein level, as EMF exposure results in Cav1-dependent phosphorylation of cAMP-responding element binding protein to drive neuronal genes such as NeuroD1 and Neurogenin 1 [104]. Such findings also raise the possibility of calcium ions as the mechanistic explanation, as a magnetic field may elevate the permeability of voltage-gated calcium channels in NSCs [104]. In summary, this epigenetic evidence provides more scenarios under which neuromodulation modifies the micro-niche of transplantation sites to improve cell survival, proliferation, differentiation, and functional recovery (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Neuromodulation techniques used to alter stem cell functions in vitro and in vivo.

Future perspectives: combining physical exercise and neuromodulation in stem cell therapy

We have reviewed the current progress of major neuromodulation methods regarding their potency in the improvement of cell proliferation, migration, and synaptic formation in stem cell therapy. Of note, lifestyle intervention, especially exercise training, may work in conjunction with neuromodulation to further improve its efficiency in stem cell therapy. This hypothesis is supported by evidence for the valuable role of exercise training in improving the proliferation, migration or differentiation, and synaptogenesis of transplanted NSCs.

For decades, exercise training has been found to stimulate adult neurogenesis in vivo. In the late 1990s, a mouse study revealed elevated cell proliferation and neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus [105]. Besides healthy animals, exercise training also aids the protection of NSC proliferation under disease conditions, such as reversal of the ethanol-induced inhibition of neural proliferation [106]. In recent years, investigation of the exercise-mediated antidepressant effect has revealed the potential involvement of adult neurogenesis [107–109]. Such a neuroprotective effect has also been implicated in aging models [110]. From the functional perspective, exercise training also prevents cognitive deficits [111, 112]. It is worth noting that most of the known effects of exercise training in facilitating adult neurogenesis occur in hippocampal regions but not in other neural stem cell niches [113]. The underlying reason is unclear, but the implication is that the NSC transplant site should be taken into account before applying exercise intervention. When studying the molecular mechanism of exercise-enhanced adult neurogenesis, it is well established that BDNF plays an indispensable role [114], in addition to the systemic circulation of cathepsin B [115] and metabolites such as lactate [116]. Although most of the current studies have investigated exercise-related neural mechanism in rodent models, there are also human studies and meta-analysis demonstrating the build-up of adult neurogenesis in humans by physical activity [117]. Such enhancement of neurogenesis is further supported by a human study, which showed an enlarged hippocampus in aged people after exercise training [118]. Although there is no direct study investigating the potency of exercise training in facilitating the proliferation of transplanted neural stem cells, accumulating evidence from endogenous neurogenesis strongly suggest the potency of exercise intervention as a promising approach for improving the efficiency of stem cell therapy.

Besides the facilitation of stem cell proliferation, exercise training has also been suggested to mediate the migration and differentiation of stem cells. In one study, physical exercise enhanced the migration of NSCs in the SVZ, as well as their differentiation in the striatum after ischemic stroke [119]. This process was mediated by the stromal cell-derived factor-1α and CXCR4 pathway [119]. In a second study using rodent models, running wheel exercise also helped to maintain the normal migration and differentiation of adult-born neural precursors [120]. Evidence from different lines of investigation supports the positive role of exercise training in promoting NSC migration during functional recovery from ischemic stroke [121] or cerebral hemorrhage [122]. In a manner similar to cell migration, exercise training also accelerates the differentiation of NSCs [123, 124], thus promoting the functional integration of newly-formed neurons into existing networks for timely functional recovery.

Not limited to the facilitation of neurogenesis and cell differentiation, exercise training also enhances synaptic plasticity. An early study has shown the enhancement of long-term potentiation in the rat dentate gyrus by physical exercise [125]. Such effects are believed to be closely associated with neurotrophic factors such as BDNF [125]. Our recent data has provided the first piece of in vivo evidence showing how exercise training enhances synaptogenesis across different cortical regions [126, 127]. Such effects are dependent on BDNF signaling [127] and the downstream activation of the mechanistic target of rapamycin pathway [126]. It is worth noting that the neuronal activity is enhanced in ex vivo and in vivo recording, forming an activity-dependent plasticity regulation model. Based on such findings, it is possible that appropriate exercise intervention can help to improve the efficiency of neuromodulation, to achieve the ultimate goal of targeted neural network integration of engrafted NSCs.

Conclusion

Although neuromodulation-based stem cell therapy has unique advantages, a number of challenges need to be resolved, such as the identification of target regions, the optimization stimulation parameters, and the minimization of side-effects across different patients. To overcome such disadvantages, it is necessary to develop more precisely modulated approaches with an optimal stimulation region or intensity.

Despite these challenges, neuromodulation could still greatly facilitate the efficiency of stem cell therapy for brain repair. These techniques could promote the neurogenic potential of stem cells in vitro and improve the in vivo differentiation potency of cells for transplantation. Neuromodulation techniques also affect the neurochemical, neuroimmune, and neurotrophic components in the brain, to create a suitable niche for cell transplantation. Finally, neuromodulation techniques facilitate the homing, differentiation, and survival of transplanted stem cells, and the proper synaptic integration for functional recovery. On the other hand, the neuromodulation approach can be combined with environmental interventions, especially physical exercise, to achieve higher efficiency of neural rehabilitation. In sum, the proliferation, migration, and integration of NSC grafts can be enhanced by combining neuromodulation techniques, indicating a promising future for cell therapy in the clinic.

Acknowledgements

This review was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2020YFA0113600 and 2017YFA0105201), National Natural Sciences Foundation of China (81822017 and 32070955). We thank our lab members for help during manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Ti-Fei Yuan, Yi Dong and Li Zhang have contributed equally to this review.

Contributor Information

Yongjun Wang, Email: wyjbs@ntu.edu.cn.

Renjie Chai, Email: renjiec@seu.edu.cn.

Yan Liu, Email: yanliu@njmu.edu.cn.

Kwok-Fai So, Email: hrmaskf@hku.hk.

References

- 1.Trounson A, McDonald C. Stem cell therapies in clinical trials: progress and challenges. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;17:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rossi F, Cattaneo E. Opinion: neural stem cell therapy for neurological diseases: dreams and reality. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:401–409. doi: 10.1038/nrn809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huo W, Liu X, Tan C, Han Y, Kang C, Quan W, et al. Stem cell transplantation for treating stroke: status, trends and development. Neural Regen Res. 2014;9:1643–1648. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.141793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miocinovic S, Somayajula S, Chitnis S, Vitek JL. History, applications, and mechanisms of deep brain stimulation. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70:163–171. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamaneurol.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson MD, Miocinovic S, McIntyre CC, Vitek JL. Mechanisms and targets of deep brain stimulation in movement disorders. Neurotherapeutics. 2008;5:294–308. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stover NP, Okun MS, Evatt ML, Raju DV, Bakay RAE, Vitek JL. Stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus in a patient with Parkinson disease and essential tremor. Archives of Neurology. 2005;62:141–143. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.1.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herzog J, Hamel W, Wenzelburger R, Potter M, Pinsker MO, Bartussek J, et al. Kinematic analysis of thalamic versus subthalamic neurostimulation in postural and intention tremor. Brain. 2007;130:1608–1625. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herrington TM, Cheng JJ, Eskandar EN. Mechanisms of deep brain stimulation. J Neurophysiol. 2016;115:19–38. doi: 10.1152/jn.00281.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vedam-Mai V, van Battum EY, Kamphuis W, Feenstra MG, Denys D, Reynolds BA, et al. Deep brain stimulation and the role of astrocytes. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17(124–131):115. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hallett M. Transcranial magnetic stimulation: a primer. Neuron. 2007;55:187–199. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Medina FJ, Tunez I. Mechanisms and pathways underlying the therapeutic effect of transcranial magnetic stimulation. Rev Neurosci. 2013;24:507–525. doi: 10.1515/revneuro-2013-0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pell GS, Roth Y, Zangen A. Modulation of cortical excitability induced by repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation: influence of timing and geometrical parameters and underlying mechanisms. Prog Neurobiol. 2011;93:59–98. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Denslow S, Lomarev M, George MS, Bohning DE. Cortical and subcortical brain effects of transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS)-induced movement: an interleaved TMS/functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:752–760. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strafella AP, Paus T, Barrett J, Dagher A. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the human prefrontal cortex induces dopamine release in the caudate nucleus. J Neurosci 2001, 21: RC157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Strafella AP, Paus T, Fraraccio M, Dagher A. Striatal dopamine release induced by repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the human motor cortex. Brain. 2003;126:2609–2615. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brys M, Fox MD, Agarwal S, Biagioni M, Dacpano G, Kumar P, et al. Multifocal repetitive TMS for motor and mood symptoms of Parkinson disease: a randomized trial. Neurology. 2016;87:1907–1915. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Reardon JP, Solvason HB, Janicak PG, Sampson S, Isenberg KE, Nahas Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of transcranial magnetic stimulation in the acute treatment of major depression: a multisite randomized controlled trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:1208–1216. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stagg CJ, Nitsche MA. Physiological basis of transcranial direct current stimulation. Neuroscientist. 2011;17:37–53. doi: 10.1177/1073858410386614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Medeiros LF, de Souza IC, Vidor LP, de Souza A, Deitos A, Volz MS, et al. Neurobiological effects of transcranial direct current stimulation: A review. Front Psychiatry. 2012;3:110. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2012.00110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuo MF, Grosch J, Fregni F, Paulus W, Nitsche MA. Focusing effect of acetylcholine on neuroplasticity in the human motor cortex. J Neurosci. 2007;27:14442–14447. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4104-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nitsche MA, Fricke K, Henschke U, Schlitterlau A, Liebetanz D, Lang N, et al. Pharmacological modulation of cortical excitability shifts induced by transcranial direct current stimulation in humans. J Physiol. 2003;553:293–301. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.049916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nitsche MA, Liebetanz D, Schlitterlau A, Henschke U, Fricke K, Frommann K, et al. GABAergic modulation of DC stimulation-induced motor cortex excitability shifts in humans. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:2720–2726. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-816X.2004.03398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lefaucheur JP, Antal A, Ayache SS, Benninger DH, Brunelin J, Cogiamanian F, et al. Evidence-based guidelines on the therapeutic use of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) Clin Neurophysiol. 2017;128:56–92. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2016.10.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tufail Y, Matyushov A, Baldwin N, Tauchmann ML, Georges J, Yoshihiro A, et al. Transcranial pulsed ultrasound stimulates intact brain circuits. Neuron. 2010;66:681–694. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Folloni D, Verhagen L, Mars RB, Fouragnan E, Constans C, Aubry JF, et al. Manipulation of subcortical and deep cortical activity in the primate brain using transcranial focused ultrasound stimulation. Neuron. 2019;101(1109–1116):e1105. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Legon W, Sato TF, Opitz A, Mueller J, Barbour A, Williams A, et al. Transcranial focused ultrasound modulates the activity of primary somatosensory cortex in humans. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:322–329. doi: 10.1038/nn.3620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Niu L, Guo Y, Lin Z, Shi Z, Bian T, Qi L, et al. Noninvasive ultrasound deep brain stimulation of nucleus accumbens induces behavioral avoidance. Sci China Life Sci. 2020;63:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s11427-019-1616-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee W, Croce P, Margolin RW, Cammalleri A, Yoon K, Yoo SS. Transcranial focused ultrasound stimulation of motor cortical areas in freely-moving awake rats. BMC Neurosci. 2018;19:57. doi: 10.1186/s12868-018-0459-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gibson BC, Sanguinetti JL, Badran BW, Yu AB, Klein EP, Abbott CC, et al. Increased excitability induced in the primary motor cortex by transcranial ultrasound stimulation. Front Neurol. 2018;9:1007. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.01007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu R, Sun Z, Li C, Ramakrishna S, Chiu K, He L. Electrical stimulation affects neural stem cell fate and function in vitro. Exp Neurol. 2019;319:112963. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2019.112963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shapiro S, Borgens R, Pascuzzi R, Roos K, Groff M, Purvines S, et al. Oscillating field stimulation for complete spinal cord injury in humans: a Phase 1 trial. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;2:3–10. doi: 10.3171/spi.2005.2.1.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li L, El-Hayek YH, Liu BS, Chen YH, Gomez E, Wu XH, et al. Direct-current electrical field guides neuronal stem/progenitor cell migration. Stem Cells. 2008;26:2193–2200. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ariza CA, Fleury AT, Tormos CJ, Petruk V, Chawla S, Oh J, et al. The influence of electric fields on hippocampal neural progenitor cells. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2010;6:585–600. doi: 10.1007/s12015-010-9171-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishimura KY, Isseroff RR, Nuccitelli R. Human keratinocytes migrate to the negative pole in direct current electric fields comparable to those measured in mammalian wounds. J Cell Sci. 1996;109(Pt 1):199–207. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.1.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang J, Calafiore M, Zeng Q, Zhang X, Huang Y, Li RA, et al. Electrically guiding migration of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2011;7:987–996. doi: 10.1007/s12015-011-9247-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li Y, Weiss M, Yao L. Directed migration of embryonic stem cell-derived neural cells in an applied electric field. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2014;10:653–662. doi: 10.1007/s12015-014-9518-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feng JF, Liu J, Zhang XZ, Zhang L, Jiang JY, Nolta J, et al. Guided migration of neural stem cells derived from human embryonic stem cells by an electric field. Stem Cells. 2012;30:349–355. doi: 10.1002/stem.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chang HF, Lee YS, Tang TK, Cheng JY. Pulsed DC electric field-induced differentiation of cortical neural precursor cells. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0158133. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao H, Steiger A, Nohner M, Ye H. Specific intensity direct current (DC) electric field improves neural stem cell migration and enhances differentiation towards betaIII-tubulin+ neurons. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0129625. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kobelt LJ, Wilkinson AE, McCormick AM, Willits RK, Leipzig ND. Short duration electrical stimulation to enhance neurite outgrowth and maturation of adult neural stem progenitor cells. Ann Biomed Eng. 2014;42:2164–2176. doi: 10.1007/s10439-014-1058-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang M, Li P, Liu M, Song W, Wu Q, Fan Y. Potential protective effect of biphasic electrical stimulation against growth factor-deprived apoptosis on olfactory bulb neural progenitor cells through the brain-derived neurotrophic factor-phosphatidylinositol 3'-kinase/Akt pathway. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2013;238:951–959. doi: 10.1177/1535370213494635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chang KA, Kim JW, Kim JA, Lee SE, Kim S, Suh WH, et al. Biphasic electrical currents stimulation promotes both proliferation and differentiation of fetal neural stem cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18738. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thrivikraman G, Madras G, Basu B. Intermittent electrical stimuli for guidance of human mesenchymal stem cell lineage commitment towards neural-like cells on electroconductive substrates. Biomaterials. 2014;35:6219–6235. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim EC, Leesungbok R, Lee SW, Lee HW, Park SH, Mah SJ, et al. Effects of moderate intensity static magnetic fields on human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Bioelectromagnetics. 2015;36:267–276. doi: 10.1002/bem.21903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prasad A, Teh DBL, Blasiak A, Chai C, Wu Y, Gharibani PM, et al. Static magnetic field stimulation enhances oligodendrocyte differentiation and secretion of neurotrophic factors. Sci Rep. 2017;7:6743. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06331-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nakamichi N, Ishioka Y, Hirai T, Ozawa S, Tachibana M, Nakamura N, et al. Possible promotion of neuronal differentiation in fetal rat brain neural progenitor cells after sustained exposure to static magnetism. J Neurosci Res. 2009;87:2406–2417. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Muller MB, Toschi N, Kresse AE, Post A, Keck ME. Long-term repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation increases the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and cholecystokinin mRNA, but not neuropeptide tyrosine mRNA in specific areas of rat brain. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;23:205–215. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00099-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen YH, Zhang RG, Xue F, Wang HN, Chen YC, Hu GT, et al. Quetiapine and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation ameliorate depression-like behaviors and up-regulate the proliferation of hippocampal-derived neural stem cells in a rat model of depression: The involvement of the BDNF/ERK signal pathway. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2015;136:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cheng Y, Dai Y, Zhu X, Xu H, Cai P, Xia R, et al. Extremely low-frequency electromagnetic fields enhance the proliferation and differentiation of neural progenitor cells cultured from ischemic brains. Neuroreport. 2015;26:896–902. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0000000000000450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Park JE, Seo YK, Yoon HH, Kim CW, Park JK, Jeon S. Electromagnetic fields induce neural differentiation of human bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells via ROS mediated EGFR activation. Neurochem Int. 2013;62:418–424. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2013.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cho H, Seo YK, Yoon HH, Kim SC, Kim SM, Song KY, et al. Neural stimulation on human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells by extremely low frequency electromagnetic fields. Biotechnol Prog. 2012;28:1329–1335. doi: 10.1002/btpr.1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sun LY, Hsieh DK, Yu TC, Chiu HT, Lu SF, Luo GH, et al. Effect of pulsed electromagnetic field on the proliferation and differentiation potential of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Bioelectromagnetics. 2009;30:251–260. doi: 10.1002/bem.20472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schwartz Z, Simon BJ, Duran MA, Barabino G, Chaudhri R, Boyan BD. Pulsed electromagnetic fields enhance BMP-2 dependent osteoblastic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. J Orthop Res. 2008;26:1250–1255. doi: 10.1002/jor.20591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang Y, Ding J, Duan W. A study of the effects of flux density and frequency of pulsed electromagnetic field on neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells. J Biol Phys. 2006;32:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10867-006-6901-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen C, Ma Q, Liu C, Deng P, Zhu G, Zhang L, et al. Exposure to 1800 MHz radiofrequency radiation impairs neurite outgrowth of embryonic neural stem cells. Sci Rep. 2014;4:5103. doi: 10.1038/srep05103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Piacentini R, Ripoli C, Mezzogori D, Azzena GB, Grassi C. Extremely low-frequency electromagnetic fields promote in vitro neurogenesis via upregulation of Ca(v)1-channel activity. J Cell Physiol. 2008;215:129–139. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee IC, Lo TL, Young TH, Li YC, Chen NG, Chen CH, et al. Differentiation of neural stem/progenitor cells using low-intensity ultrasound. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2014;40:2195–2206. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lv Y, Zhao P, Chen G, Sha Y, Yang L. Effects of low-intensity pulsed ultrasound on cell viability, proliferation and neural differentiation of induced pluripotent stem cells-derived neural crest stem cells. Biotechnol Lett. 2013;35:2201–2212. doi: 10.1007/s10529-013-1313-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee IC, Wu HJ, Liu HL. Dual-frequency ultrasound induces neural stem/progenitor cell differentiation and growth factor utilization by enhancing stable cavitation. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2019;10:1452–1461. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ming GL, Song H. Adult neurogenesis in the mammalian central nervous system. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2005;28:223–250. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.051804.101459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lepousez G, Valley MT, Lledo PM. The impact of adult neurogenesis on olfactory bulb circuits and computations. Annu Rev Physiol. 2013;75:339–363. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-030212-183731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Christian KM, Song H, Ming GL. Functions and dysfunctions of adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2014;37:243–262. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-071013-014134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Suh H, Deng W, Gage FH. Signaling in adult neurogenesis. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2009;25:253–275. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.042308.113256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lie DC, Song H, Colamarino SA, Ming GL, Gage FH. Neurogenesis in the adult brain: new strategies for central nervous system diseases. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2004;44:399–421. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.44.101802.121631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nuninga JO, Mandl RCW, Boks MP, Bakker S, Somers M, Heringa SM, et al. Volume increase in the dentate gyrus after electroconvulsive therapy in depressed patients as measured with 7T. Mol Psychiatry 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 66.Van Den Bossche MJA, Emsell L, Dols A, Vansteelandt K, De Winter FL, Van den Stock J, et al. Hippocampal volume change following ECT is mediated by rs699947 in the promotor region of VEGF. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9:191. doi: 10.1038/s41398-019-0530-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liu A, Jain N, Vyas A, Lim LW. Ventromedial prefrontal cortex stimulation enhances memory and hippocampal neurogenesis in the middle-aged rats. Elife 2015, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 68.Magdaleno-Madrigal VM, Pantoja-Jimenez CR, Bazaldua A, Fernandez-Mas R, Almazan-Alvarado S, Bolanos-Alejos F, et al. Acute deep brain stimulation in the thalamic reticular nucleus protects against acute stress and modulates initial events of adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Behav Brain Res. 2016;314:65–76. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pohodich AE, Yalamanchili H, Raman AT, Wan YW, Gundry M, Hao S, et al. Forniceal deep brain stimulation induces gene expression and splicing changes that promote neurogenesis and plasticity. Elife 2018, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 70.Toda H, Hamani C, Fawcett AP, Hutchison WD, Lozano AM. The regulation of adult rodent hippocampal neurogenesis by deep brain stimulation. J Neurosurg. 2008;108:132–138. doi: 10.3171/JNS/2008/108/01/0132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dela Cruz JA, Hescham S, Adriaanse B, Campos FL, Steinbusch HW, Rutten BP, et al. Increased number of TH-immunoreactive cells in the ventral tegmental area after deep brain stimulation of the anterior nucleus of the thalamus. Brain Struct Funct. 2015;220:3061–3066. doi: 10.1007/s00429-014-0832-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Khaindrava V, Salin P, Melon C, Ugrumov M, Kerkerian-Le-Goff L, Daszuta A. High frequency stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus impacts adult neurogenesis in a rat model of Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2011;42:284–291. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vedam-Mai V, Gardner B, Okun MS, Siebzehnrubl FA, Kam M, Aponso P, et al. Increased precursor cell proliferation after deep brain stimulation for Parkinson's disease: a human study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e88770. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ueyama E, Ukai S, Ogawa A, Yamamoto M, Kawaguchi S, Ishii R, et al. Chronic repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation increases hippocampal neurogenesis in rats. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;65:77–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2010.02170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lee JY, Kim HS, Kim SH, Kim HS, Cho BP. Combination of human mesenchymal stem cells and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation enhances neurological recovery of 6-hydroxydopamine model of Parkinsonian's disease. Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2020;17:67–80. doi: 10.1007/s13770-019-00233-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Peng JJ, Sha R, Li MX, Chen LT, Han XH, Guo F, et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation promotes functional recovery and differentiation of human neural stem cells in rats after ischemic stroke. Exp Neurol. 2019;313:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2018.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Arias-Carrion O, Verdugo-Diaz L, Feria-Velasco A, Millan-Aldaco D, Gutierrez AA, Hernandez-Cruz A, et al. Neurogenesis in the subventricular zone following transcranial magnetic field stimulation and nigrostriatal lesions. J Neurosci Res. 2004;78:16–28. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Luo J, Zheng H, Zhang L, Zhang Q, Li L, Pei Z, et al. High-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) improves functional recovery by enhancing neurogenesis and activating BDNF/TrkB signaling in ischemic rats. Int J Mol Sci 2017, 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 79.Guo F, Han X, Zhang J, Zhao X, Lou J, Chen H, et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation promotes neural stem cell proliferation via the regulation of MiR-25 in a rat model of focal cerebral ischemia. PLoS One. 2014;9:e109267. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cullen CL, Senesi M, Tang AD, Clutterbuck MT, Auderset L, O'Rourke ME, et al. Low-intensity transcranial magnetic stimulation promotes the survival and maturation of newborn oligodendrocytes in the adult mouse brain. Glia. 2019;67:1462–1477. doi: 10.1002/glia.23620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pelletier SJ, Cicchetti F. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of action of transcranial direct current stimulation: evidence from in vitro and in vivo models. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2014, 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 82.Braun R, Klein R, Walter HL, Ohren M, Freudenmacher L, Getachew K, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation accelerates recovery of function, induces neurogenesis and recruits oligodendrocyte precursors in a rat model of stroke. Exp Neurol. 2016;279:127–136. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2016.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pikhovych A, Stolberg NP, Jessica Flitsch L, Walter HL, Graf R, Fink GR, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation modulates neurogenesis and microglia activation in the mouse brain. Stem Cells Int. 2016;2016:2715196. doi: 10.1155/2016/2715196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Alam MA, Subramanyam Rallabandi VP, Roy PK. Systems Biology of Immunomodulation for post-stroke neuroplasticity: Multimodal implications of pharmacotherapy and neurorehabilitation. Front Neurol. 2016;7:94. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2016.00094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Monai H, Hirase H. Astrocytic calcium activation in a mouse model of tDCS-Extended discussion. Neurogenesis (Austin) 2016;3:e1240055. doi: 10.1080/23262133.2016.1240055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Iwasa SN, Rashidi A, Sefton E, Liu NX, Popovic MR, Morshead CM. Charge-balanced electrical stimulation can modulate neural precursor cell migration in the presence of endogenous electric fields in mouse brains. eNeuro 2019, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 87.Brundin P, Nilsson OG, Strecker RE, Lindvall O, Astedt B, Bjorklund A. Behavioural effects of human fetal dopamine neurons grafted in a rat model of Parkinson's disease. Exp Brain Res. 1986;65:235–240. doi: 10.1007/BF00243848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Defer GL, Geny C, Ricolfi F, Fenelon G, Monfort JC, Remy P, et al. Long-term outcome of unilaterally transplanted parkinsonian patients I. Clinical approach. Brain. 1996;119(Pt 1):41–50. doi: 10.1093/brain/119.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Olanow CW, Goetz CG, Kordower JH, Stoessl AJ, Sossi V, Brin MF, et al. A double-blind controlled trial of bilateral fetal nigral transplantation in Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol. 2003;54:403–414. doi: 10.1002/ana.10720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tang M, Yan X, Tang Q, Guo R, Da P, Li D. Potential application of electrical stimulation in stem cell-based treatment against hearing loss. Neural Plast. 2018;2018:9506387. doi: 10.1155/2018/9506387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Du J, Zhen G, Chen H, Zhang S, Qing L, Yang X, et al. Optimal electrical stimulation boosts stem cell therapy in nerve regeneration. Biomaterials. 2018;181:347–359. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Feng JF, Liu J, Zhang L, Jiang JY, Russell M, Lyeth BG, et al. Electrical guidance of human stem cells in the rat brain. Stem Cell Reports. 2017;9:177–189. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.05.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Krueger E, Magri LMS, Botelho AS, Bach FS, Rebellato CLK, Fracaro L, et al. Effects of low-intensity electrical stimulation and adipose derived stem cells transplantation on the time-domain analysis-based electromyographic signals in dogs with SCI. Neurosci Lett. 2019;696:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2018.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yang Y, Ma T, Ge J, Quan X, Yang L, Zhu S, et al. Facilitated neural differentiation of adipose tissue-derived stem cells by electrical stimulation and Nurr-1 gene transduction. Cell Transplant. 2016;25:1177–1191. doi: 10.3727/096368915X688957a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cui M, Ge H, Zeng H, Yan H, Zhang L, Feng H, et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation promotes neural stem cell proliferation and differentiation after intracerebral hemorrhage in mice. Cell Transplant. 2019;28:568–584. doi: 10.1177/0963689719834870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Cao L, Wei D, Reid B, Zhao S, Pu J, Pan T, et al. Endogenous electric currents might guide rostral migration of neuroblasts. EMBO Rep. 2013;14:184–190. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yao L, Li Y. The role of direct current electric field-guided stem cell migration in neural regeneration. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2016;12:365–375. doi: 10.1007/s12015-016-9654-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Keuters MH, Aswendt M, Tennstaedt A, Wiedermann D, Pikhovych A, Rotthues S, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation promotes the mobility of engrafted NSCs in the rat brain. NMR Biomed. 2015;28:231–239. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.George PM, Steinberg GK. Novel stroke therapeutics: unraveling stroke pathophysiology and its impact on clinical treatments. Neuron. 2015;87:297–309. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.05.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Byers B, Lee HJ, Liu J, Weitz AJ, Lin P, Zhang P, et al. Direct in vivo assessment of human stem cell graft-host neural circuits. Neuroimage. 2015;114:328–337. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.03.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Leone L, Fusco S, Mastrodonato A, Piacentini R, Barbati SA, Zaffina S, et al. Epigenetic modulation of adult hippocampal neurogenesis by extremely low-frequency electromagnetic fields. Mol Neurobiol. 2014;49:1472–1486. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-8650-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Liu H, Li G, Ma C, Chen Y, Wang J, Yang Y. Repetitive magnetic stimulation promotes the proliferation of neural progenitor cells via modulating the expression of miR-106b. Int J Mol Med. 2018;42:3631–3639. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2018.3922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Cao P, Wang L, Cheng Q, Sun X, Kang Q, Dai L, et al. Changes in serum miRNA-let-7 level in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder treated by repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation or atomoxetine: an exploratory trial. Psychiatry Res. 2019;274:189–194. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cui M, Ge H, Zhao H, Zou Y, Chen Y, Feng H. Electromagnetic fields for the regulation of neural stem cells. Stem Cells Int. 2017;2017:9898439. doi: 10.1155/2017/9898439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.van Praag H, Kempermann G, Gage FH. Running increases cell proliferation and neurogenesis in the adult mouse dentate gyrus. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:266–270. doi: 10.1038/6368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Crews FT, Nixon K, Wilkie ME. Exercise reverses ethanol inhibition of neural stem cell proliferation. Alcohol. 2004;33:63–71. doi: 10.1016/S0741-8329(04)00081-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Micheli L, Ceccarelli M, D'Andrea G, Tirone F. Depression and adult neurogenesis: Positive effects of the antidepressant fluoxetine and of physical exercise. Brain Res Bull. 2018;143:181–193. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2018.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Yuan TF, Paes F, Arias-Carrion O, Ferreira Rocha NB, de Sa Filho AS, Machado S. Neural mechanisms of exercise: anti-depression, neurogenesis, and serotonin signaling. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2015;14:1307–1311. doi: 10.2174/1871527315666151111124402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sun L, Sun Q, Qi J. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis: an important target associated with antidepressant effects of exercise. Rev Neurosci. 2017;28:693–703. doi: 10.1515/revneuro-2016-0076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Saraulli D, Costanzi M, Mastrorilli V, Farioli-Vecchioli S. The long run: Neuroprotective effects of physical exercise on adult neurogenesis from youth to old age. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2017;15:519–533. doi: 10.2174/1570159X14666160412150223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ma CL, Ma XT, Wang JJ, Liu H, Chen YF, Yang Y. Physical exercise induces hippocampal neurogenesis and prevents cognitive decline. Behav Brain Res. 2017;317:332–339. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.09.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.O'Leary JD, Hoban AE, Murphy A, O'Leary OF, Cryan JF, Nolan YM. Differential effects of adolescent and adult-initiated exercise on cognition and hippocampal neurogenesis. Hippocampus. 2019;29:352–365. doi: 10.1002/hipo.23032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Brown J, Cooper-Kuhn CM, Kempermann G, Van Praag H, Winkler J, Gage FH, et al. Enriched environment and physical activity stimulate hippocampal but not olfactory bulb neurogenesis. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:2042–2046. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Liu PZ, Nusslock R. Exercise-mediated neurogenesis in the hippocampus via BDNF. Front Neurosci. 2018;12:52. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Moon HY, Becke A, Berron D, Becker B, Sah N, Benoni G, et al. Running-induced systemic cathepsin B secretion is associated with memory function. Cell Metab. 2016;24:332–340. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Lev-Vachnish Y, Cadury S, Rotter-Maskowitz A, Feldman N, Roichman A, Illouz T, et al. L-lactate promotes adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:403. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Lei X, Wu Y, Xu M, Jones OD, Ma J, Xu X. Physical exercise: bulking up neurogenesis in human adults. Cell Biosci. 2019;9:74. doi: 10.1186/s13578-019-0337-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Erickson KI, Voss MW, Prakash RS, Basak C, Szabo A, Chaddock L, et al. Exercise training increases size of hippocampus and improves memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:3017–3022. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015950108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Luo J, Hu X, Zhang L, Li L, Zheng H, Li M, et al. Physical exercise regulates neural stem cells proliferation and migration via SDF-1alpha/CXCR4 pathway in rats after ischemic stroke. Neurosci Lett. 2014;578:203–208. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2014.06.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Mastrorilli V, Scopa C, Saraulli D, Costanzi M, Scardigli R, Rouault JP, et al. Physical exercise rescues defective neural stem cells and neurogenesis in the adult subventricular zone of Btg1 knockout mice. Brain Struct Funct. 2017;222:2855–2876. doi: 10.1007/s00429-017-1376-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Hicks AU, Hewlett K, Windle V, Chernenko G, Ploughman M, Jolkkonen J, et al. Enriched environment enhances transplanted subventricular zone stem cell migration and functional recovery after stroke. Neuroscience. 2007;146:31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Jin J, Kang HM, Park C. Voluntary exercise enhances survival and migration of neural progenitor cells after intracerebral haemorrhage in mice. Brain Inj. 2010;24:533–540. doi: 10.3109/02699051003610458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Nam SM, Kim JW, Yoo DY, Yim HS, Kim DW, Choi JH, et al. Physical exercise ameliorates the reduction of neural stem cell, cell proliferation and neuroblast differentiation in senescent mice induced by D-galactose. BMC Neurosci. 2014;15:116. doi: 10.1186/s12868-014-0116-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Nam SM, Kim JW, Yoo DY, Choi JH, Kim W, Jung HY, et al. Effects of treadmill exercise on neural stem cells, cell proliferation, and neuroblast differentiation in the subgranular zone of the dentate gyrus in cyclooxygenase-2 knockout mice. Neurochem Res. 2013;38:2559–2569. doi: 10.1007/s11064-013-1169-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Farmer J, Zhao X, van Praag H, Wodtke K, Gage FH, Christie BR. Effects of voluntary exercise on synaptic plasticity and gene expression in the dentate gyrus of adult male Sprague-Dawley rats in vivo. Neuroscience. 2004;124:71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Chen K, Zheng Y, Wei JA, Ouyang H, Huang X, Zhang F, et al. Exercise training improves motor skill learning via selective activation of mTOR. Sci Adv 2019, 5: eaaw1888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 127.Chen K, Zhang L, Tan M, Lai CS, Li A, Ren C, et al. Treadmill exercise suppressed stress-induced dendritic spine elimination in mouse barrel cortex and improved working memory via BDNF/TrkB pathway. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;7:e1069. doi: 10.1038/tp.2017.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]