Abstract

Rationale

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2/coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic has highlighted the serious unmet need for effective therapies that reduce acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) mortality. We explored whether extracellular nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (eNAMPT), a ligand for Toll-like receptor (TLR)4 and a master regulator of innate immunity and inflammation, is a potential ARDS therapeutic target.

Methods

Wild-type C57BL/6J or endothelial cell (EC)-cNAMPT−/− knockout mice (targeted EC NAMPT deletion) were exposed to either a lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced (“one-hit”) or a combined LPS/ventilator (“two-hit”)-induced acute inflammatory lung injury model. A NAMPT-specific monoclonal antibody (mAb) imaging probe (99mTc-ProNamptor) was used to detect NAMPT expression in lung tissues. Either an eNAMPT-neutralising goat polyclonal antibody (pAb) or a humanised monoclonal antibody (ALT-100 mAb) were used in vitro and in vivo.

Results

Immunohistochemical, biochemical and imaging studies validated time-dependent increases in NAMPT lung tissue expression in both pre-clinical ARDS models. Intravenous delivery of either eNAMPT-neutralising pAb or mAb significantly attenuated inflammatory lung injury (haematoxylin and eosin staining, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) protein, BAL polymorphonuclear cells, plasma interleukin-6) in both pre-clinical models. In vitro human lung EC studies demonstrated eNAMPT-neutralising antibodies (pAb, mAb) to strongly abrogate eNAMPT-induced TLR4 pathway activation and EC barrier disruption. In vivo studies in wild-type and EC-cNAMPT−/− mice confirmed a highly significant contribution of EC-derived NAMPT to the severity of inflammatory lung injury in both pre-clinical ARDS models.

Conclusions

These findings highlight both the role of EC-derived eNAMPT and the potential for biologic targeting of the eNAMPT/TLR4 inflammatory pathway. In combination with predictive eNAMPT biomarker and NAMPT genotyping assays, this offers the opportunity to identify high-risk ARDS subjects for delivery of personalised medicine.

Short abstract

Underscoring the therapeutic potential for targeting the eNAMPT/TLR4 pathway in ARDS/VILI, a humanised eNAMPT-neutralising monoclonal antibody (mAb) was highly effective in reducing the severity of ARDS in these dual complementary pre-clinical ARDS models https://bit.ly/3ljEhBD

Introduction

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2/coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and the unprecedented numbers of deaths due to COVID-19-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) have dramatically highlighted multiple unmet needs of ARDS patients. These include the absence of validated ARDS biomarkers and the absence of effective United States Food and Drug Administration-approved ARDS pharmacotherapies to address the associated lethal multiorgan failure. Although insights into the pathobiology of ARD/ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI) are limited, a key advance has been the appreciation of bacteria- and virus-induced activation of evolutionarily conserved systemic inflammatory networks [1–3], releasing a “cytokine storm” that increases lung and systemic vascular permeability, organ oedema and multiorgan dysfunction [4–7], ultimately increasing COVID-19-ARDS and non-COVID-19-ARDS mortality [8–10]. The life-threatening organ dysfunction is caused by dysregulated host responses to infection [6] mediated via interactions of pathogen-associated molecular patterns and pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) that can also be activated by host nuclear, mitochondrial and cytosolic proteins known as damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). DAMPs are also released in response to danger signals such as hypoxia, cancer, trauma and inhalation injury, thus potentially perpetuating a noninfectious inflammatory response [11].

Previously, we utilised pre-clinical multispecies ARDS models coupled with genomic-intensive approaches [12, 13] to identify novel ARDS biomarkers and targetable pathways [12–18] and identified nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT) as a novel DAMP [19] and attractive ARDS target. We showed NAMPT expression to be highly induced by multiple ARDS-related stimuli including bacterial infection, hypoxia, shock, trauma and excessive mechanical stress produced by mechanical ventilation [20–23]. Reduced expression of the gene encoding NAMPT (NAMPT) via small interfering RNAs, microRNAs and utilisation of NAMPT+/− heterozygous mice dramatically attenuated the severity of pre-clinical ARDS/VILI injury [17].

NAMPT is a cytozyme whose intracellular enzymatic activities regulate nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) biosynthesis [24, 25], contributing to injury in a tissue- and cell-specific manner [26]. However, our studies much more strongly implicate secreted extracellular (e)NAMPT as the primary mechanism of NAMPT's contribution to inflammatory lung injury and the increased mortality of critically ill ARDS patients on mechanical ventilation [17, 19, 27]. eNAMPT is a master regulator of inflammatory networks via binding to the PRR Toll-like receptor (TLR)4 [19], eliciting profound NFκB-mediated inflammatory cytokine release that increases vascular permeability and multiorgan dysfunction directly linked to ARDS mortality [14, 28–30]. Two critical observations link NAMPT expression and function to human ARDS pathobiology. First, eNAMPT plasma levels alone [14, 31–33], or as part of an ARDS plasma biomarker panel [14, 31–33], are associated with ARDS severity and mortality. Secondly, NAMPT genetic variants that alter promoter activity in response to excessive mechanical stress [14, 22, 29, 30] and hypoxia [23] also confer increased ARDS susceptibility and mortality [14, 22, 29, 30].

In the current study, we explored the validation of eNAMPT as a viable ARDS therapeutic target in “one-hit” (lipopolysaccharide (LPS)) and “two-hit” (LPS/VILI) pre-clinical ARDS models. Intravenous administration of eNAMPT-neutralising antibodies, either a polyclonal (pAb) or a humanised monoclonal (mAb), significantly reduced the severity of murine acute inflammatory lung injury. In addition, our study confirms the critical role of endothelial cell (EC)-derived eNAMPT in ARDS pathobiology, extending previous reports of robust spatially localised NAMPT expression in lung endothelium, epithelium and resident and infiltrating leukocytes, but without assessment of cell-specific NAMPT contributions to ARDS severity. Utilising EC-specific conditional NAMPT knockout mice, we now show the significant and unequivocal involvement of EC-secreted eNAMPT in dual pre-clinical ARDS models of injury. These studies strongly validate the viability of eNAMPT as an ARDS therapeutic target and underscore the capacity of an eNAMPT-neutralising biologic therapy to directly address the unmet need for novel strategies that improve ARDS/VILI mortality.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Recombinant human eNAMPT was purchased from Peprotech (Cranbury, NJ, USA). Antibodies that are immunoreactive against p-NF-κB, pp-extracellular signal regulating kinase (ERK), pp-p38, pp-c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNK), interleukin (IL)-6, and IL-8 (keratinocyte chemoattractant (KC)) were purchased from Cell Signalling Technologies (Danvers, MA, USA) and against β-actin from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA) (NF-κB). Goat, rabbit and mouse secondary antibodies were purchased from Life Technologies (Waltham, MA, USA). IgG for use as controls was obtained from Jackson ImmuneResearch (West Grove, PA, USA). Goat anti-human NAMPT pAb was custom-generated, as described previously [17]. All other reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA).

Generation of an eNAMPT-neutralising humanised mAb

Two eNAMPT-neutralising humanised mAbs, ALT-100 and ALT-300, were provided by Aqualung Therapeutics (Tucson, AZ, USA) following in vitro mAb screening utilising trans-EC electrical resistance assays [34, 35], NF-κB activation biochemical assays [19] and in vivo screening utilising dual pre-clinical ARDS models. ALT-100 was selected as the lead in vivo therapeutic and ALT-300 chosen for incorporation into the tissue NAMPT-imaging probe, 99mTc-ProNamptor. Details of mAb generation and selection are supplied in the supplementary materials and methods.

99mTc-ProNamptor. mAb imaging

Extremely high NAMPT protein sequence homology exists between mice, rats, nonhuman primates and humans (95–99%), underscoring ALT-100 and ALT-300 mAb utility in the murine pre-clinical studies we conducted including the ALT-300 mAb-containing fluorescent and 99mTc-labelled probes used for tissue imaging of NAMPT expression with human IgG serving as control [36, 37] (details of ALT-300 Cy5.5 or 99mTc labelling are available in the supplementary materials and methods). A mouse model of skin inflammation [38, 39] induced by topical application of 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) was utilised to validate the ability of the Cy5.5-ALT-300 probe to detect NAMPT tissue expression in vivo. TPA was applied to the surface of the right ear, reapplied at 24 h, and the left ear was treated with acetone as the negative control. In separate experiments (n=3 mice), either Cy5.5-ALT-300 or Cy5.5-IgG (15–20 µg) was injected i.v. 3 h after the second TPA/PBS application, followed by mouse imaging. To assess the capacity of the 99mTc-ALT-300 probe to detect in vivo NAMPT tissue expression, 99mTc-ProNamptor (1.0–1.5 mCi, >98% radiochemical purity) [40, 41] or IgG control Ab was injected i.v. at 3 h post-LPS challenge in the one-hit model and imaged (quantum imaging detector camera) [42–44]. Count activity-based measurements of 99mTc-ProNamptor biodistribution and ex vivo autoradiography were performed in harvested lungs (see the supplementary materials and methods for additional details).

Mouse strains

In vivo experiments utilised either wild-type male C57BL/6J mice (8–12 weeks; Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME, USA), EC-specific conditional NAMPT knockout mice (EC-cNAMPT−/−) on a mixed 129/B6 background, or littermate NAMPTfl/fl controls. EC-cNAMPT−/−mice were generated by crossing floxed NAMPT mice (NAMPTfl/fl) with tamoxifen-inducible EC-specific Cre transgenic mice (Tek-Cre/ERT2-1Soff) [45] with backcrossing with floxed homozygous NAMPT mice. After the final dose of tamoxifen, a 2-week minimal wait period was implemented before the utilisation of EC-cNAMPT−/− mice for experimentation (see the supplementary materials and methods for additional details). EC-specific knockout mice carrying the NAMPT flox transgene did not display discernible differences in phenotypic traits compared to their wild-type littermates. Growth rate, fecundity and fertility did not differ from wild-type mice. Similarly, NAMPT flox mice crossed with the TIE2/ERT2 Cre mice to generate the conditional NAMPT knockout line did not exhibit any phenotypic differences from either littermates or parental strains, both before and after tamoxifen injections.

eNAMPT-neutralising strategies in one-hit and two-hit pre-clinical ARDS models

For the one-hit ARDS model, mice received an intratracheal LPS injection and were sacrificed at 18 h post-LPS, as described previously [46–48]. For the two-hit LPS/VILI ARDS model, similar LPS-exposed mice were reintubated at 18 h and placed on mechanical ventilation for 4 h (tidal volume 20 mL·kg−1, respiratory rate 90 breaths·min−1, positive-end expiratory pressure 0 cmH2O), as described previously [46–48]. In specific experiments, C57BL/6J mice received either the i.v.-delivered eNAMPT-neutralising pAb or the ALT-100 mAb (4 mg·kg−1 and 0.4 mg·kg−1, respectively) or IgG control Ab (4 mg·kg−1) (see the supplementary materials and methods for additional details).

Bronchoalveolar lavage analysis

Bronchoalevolar lavage (BAL) fluid retrieval, protein analysis and cell count analysis, including polymorphonuclear cell (PMN) determinations, were performed as described previously [49], with additional details provided in the supplementary materials and methods.

Evans blue dye extravasation assay

We evaluated lung vascular leakage by measuring extravascular Evans blue dye in the lung as described previously [58]. Briefly, mice were injected with Evans blue dye (0.05 mg; Sigma) i.v. 60 min before euthanasia. Lungs were then perfused to remove the intravascular dye, excised and homogenised in PBS. One volume of lung homogenate was incubated with two volumes of formamide and incubated at 60°C for 18 h before centrifugation. The optical density of the supernatant was measured at 620 nm and 740 nm using an iMark microplate reader (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA). Concentrations of Evans blue dye were corrected for the presence of haem pigments using the following formula: A620 (corrected)=A620 (raw) − (1.1927×A720) + 0.0071. The extravasated Evans blue dye concentrations were then calculated against a standard linear curve as a reflection of vascular protein leak into lung tissues.

Quantitative lung histology and immunohistochemistry analyses

Haematoxylin and eosin staining

Lungs were fixed and sectioned for routine haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and imaging (×10 magnification, Olympus digital camera; Tokyo, Japan) [50].

NAMPT staining

The avidin-biotin-peroxidase method was utilised with a rabbit anti-human NAMPT pAb (1:1000 dilution; Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX, USA) for immunohistochemistry (IHC) visualisation of NAMPT expression in lung tissues, as described previously [14, 17, 19].

NAMPT/β-actin/CD-31 co-staining in EC-cNAMPT−/−mice

Lung tissue sections from EC-cNAMPT−/−mice were incubated overnight (4°C) with primary rabbit anti-human NAMPT pAb (Bethyl), β-actin or rat anti-CD-31 mAb and stained with biotinylated secondary antibody (1 h, 25°C) and imaged (×10 objective, NA 0.4 Zeiss Axiovert photomicroscope; Oberkochen, Germany).

Quantitative analyses

Histological and IHC images were selected randomly for H&E or NAMPT quantification using ImageJ software [51] (additional details are provided in the supplementary materials and methods).

Acute lung injury severity score quantification

The acute lung injury severity score (ALISS) was utilised to integrate lung injury indices in the one-hit and two-hit pre-clinical ARDS models and to standardise the injury levels across the in vivo models. A ranking point system, incorporating published recommendations [52] objectively assigns a score to each study animal (1–4 points) for each of four severity of injury readouts (H&E histology quantification, BAL total protein concentration, BAL total PMN cell count and plasma levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokine, IL-6). The maximal score for each animal is 16 points per mouse. In general, an ALISS score of 1–4 points reflects the complete absence of injury, scores of 5–8 points reflect mild injury, scores of 9–12 points reflect moderate injury and scores >12 points reflect severe injury. Additional details are provided in the supplementary materials and methods.

Trans-endothelial electrical resistance measurements

Human pulmonary artery EC (Lonza, Walkersville, MD, USA) were cultured as described previously [53] and seeded on evaporated gold microelectrodes (37°C, 5% carbon dioxide) to measure trans-endothelial electrical resistance (TER) using an electrical cell-substrate impedance sensing system (Applied Biophysics, Troy, NY, USA) as described previously [54]. TER values from each microelectrode were pooled and plotted versus time (mean±sem).

Biochemical tissue and plasma levels of eNAMPT, NFκB, mitogen-activated protein kinases, IL-6 and IL-8

Western blotting of lung homogenates was performed according to standard protocols as reported previously [23, 49] with densitometric quantification of lung tissue expression of NAMPT, NFκB, mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases, IL-6 and βν-actin (total protein control). eNAMPT plasma levels were measured using ELISA, as reported previously [27, 31], and plasma levels of IL-6 and IL-8 (KC) were measured using a meso-scale ELISA platform (Meso Scale Diagnostics, Rockville, MD, USA) (described in the supplementary materials and methods).

Statistical analysis

Continuous data were compared using nonparametric methods and categorical data using the Chi-squared test. Where applicable, standard one-way ANOVA was used, and groups were compared using the Newman–Keuls test. Two-way ANOVA was used to compare the means of data from two or more different experimental groups. If a significant difference was present by ANOVA (p<0.05), the least significant differences test was performed post hoc. Statistical tests were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 7.00 for Windows; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA, www.graphpad.com). Statistical significance was considered at p<0.05.

Results

Increased lung tissue NAMPT expression in pre-clinical murine ARDS models

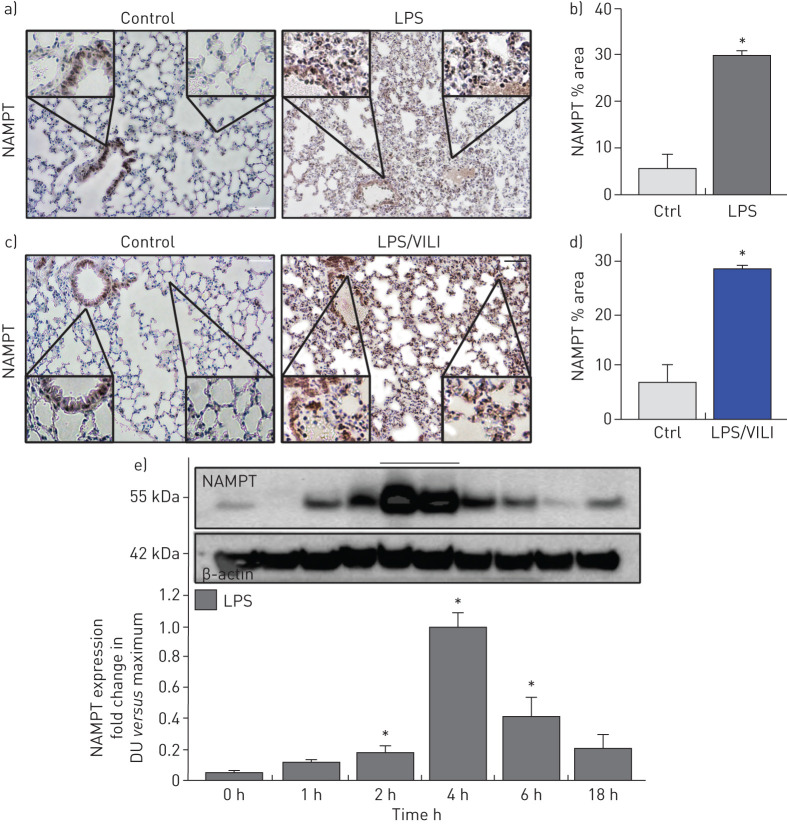

Compared to control mice, IHC lung tissue staining from mice exposed to either the one-hit (LPS 18 h) ARDS model (figure 1a) or the two-hit (LPS 18 h, ventilation 4 h) ARDS/VILI model (figure 1c) demonstrated dramatic upregulation of NAMPT expression (alveolar epithelium, endothelium, macrophages, neutrophils) summarised in figure 1b,d (p<0.05) and confirmed in lung homogenates from LPS-challenged mice. NAMPT protein expression was significantly elevated beginning 2 h post-LPS challenge, peaking at 4 h and returning towards baseline by 18 h (figure 1e).

FIGURE 1.

Increased nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT) expression in lung tissues from “one-hit” and “two-hit” pre-clinical acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) murine models. Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining to visualise NAMPT expression in lung tissues utilised a rabbit anti-human monoclonal antibody (Bethyl, Montgomery, TX, USA). Compared to control, unchallenged C57BL/6J mice, marked increases in NAMPT expression were observed in lung tissues from mice exposed to either a) a one-hit lipopolysaccharide (LPS) ARDS model (intratracheal LPS, 18 h) or c) a two-hit pre-clinical ARDS/ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI) model (LPS 22 h, ventilator exposure for final 4 h, tidal volume 20 mL·kg−1). NAMPT expression was most prominent in alveolar epithelium, endothelium, macrophages and infiltrating neutrophils (insets). b), d) Changes in NAMPT IHC staining were summarised quantitatively (Image J software) (n>5 mice per group). *: p<0.05 for LPS or LPS/VILI versus control. e) We assessed NAMPT protein expression in lung homogenates (Western blotting) at various times post-LPS challenge. Densitometric analysis (n=4 each time point) showed significant time-dependent increases in NAMPT immunoreactivity, peaking at 4 h post-LPS. DU: densitometric units. *: p<0.05. Scale bars=50 μm.

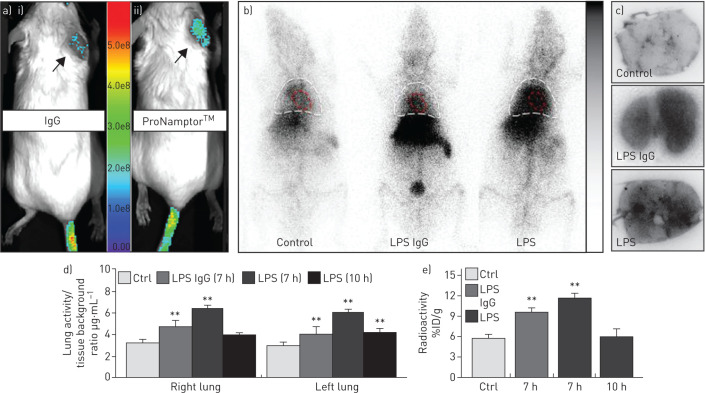

In vivo detection of NAMPT lung tissue expression

Validation of the ProNamptor mAb probe for detection of tissue inflammation was observed with the TPA-induced ear inflammation model with a significantly higher accumulation of Cy5.5-ProNamptor observed relative to the control Cy5.5-IgG (in vivo fluorescence imaging post-injection) (figure 2a). In both unchallenged control mice and LPS-challenged mice exposed to injected either the 9mTc-IgG control or 99mTc-ProNamptor, there was prominent accumulation of radioactivity in the liver and in the cardiac blood pool, and, to much lesser extent, in the lung (figure 2b). However, in vivo and ex vivo imaging demonstrated significantly increased radioactive accumulation of 99mTc-ProNamptor in lung tissues from mice exposed to the one-hit LPS ARDS model (imaged at 7 h; figure 2b) confirmed by ex vivo autoradiograph images (figure 2c). Quantification of 99mTc uptake in lung tissues at 7 h post-LPS challenge showed significant increases in both the nonspecific IgG as well as ProNamptor; however, the magnitude of 99mTc-ProNamptor radioactivity uptake was significantly increased compared to IgG control and unchallenged mice (figure 2c,d). The marked increase in 99mTc-ProNamptor radiolabel uptake at 7 h post-LPS waned substantially by 10 h post-LPS challenge (figure 2d,e), a finding that is consistent with levels of NAMPT protein expression in lung tissue homogenates depicted in figure 1e.

FIGURE 2.

ProNamptor detects nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT) expression in vivo in the “one-hit” lipopolysaccharide (LPS) pre-clinical acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) model. a) To validate the extracellular (e)NAMPT-specific monoclonal antibody (mAb)-containing ProNamptor probe's capacity to detect inflammatory injury, studies were conducted in the 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA)-induced inflammatory ear model. Representative fluorescence images of i) Cy5.5-IgG and ii) the eNAMPT-specific imaging probe, Cy5.5-ProNamptor, acquired 12 h after probe injection in two TPA-injected mice with right ear oedema. Significantly enhanced fluorescence accumulation was observed in the inflamed right ear of a mouse injected with Cy5.5-ProNamptor compared to the Cy5.5-IgG-imaged mouse (arrows). b) Representative whole-body ionising-radiation quantum imaging detector images in an unchallenged control mouse and in LPS-challenged C57BL/6J mice injected with either a nonspecific 99mTc-IgG antibody probe or with 99mTc-ProNamptor. Images were collected 7 h post-LPS instillation (3 h post-99mTc-ProNamptor injection). Magnified thoracic images highlight the detection of NAMPT expression in LPS-induced lung inflammation. Increased radioactivity is noted for both the nonspecific 99mTc-IgG Ab and the 99mTc-ProNamptor probes in the liver and the cardiac blood pool (outlined in red) of LPS-challenged animals. However, increased lung accumulation was observed with the 99mTc-ProNamptor (chest area outlined in white). c) Significantly higher radioactive accumulation of 99mTc-ProNamptor in LPS-injured lungs (7 h, compared to IgG Ab-99mTc and to control lungs) was further confirmed by ex vivo lung autoradiograph imaging (representative image, n=4). d), e) In vivo quantitative image analysis and ex vivo biodistribution measurements (% injected dose (ID)·g−1) demonstrate significant increased 99mTc-ProNamptor pulmonary uptake in LPS-injured lungs at 7 h post-LPS with waning of NAMPT uptake/expression by 10 h compared to 99mTc-IgG antibody and control lungs. **: p<0.01 compared to controls.

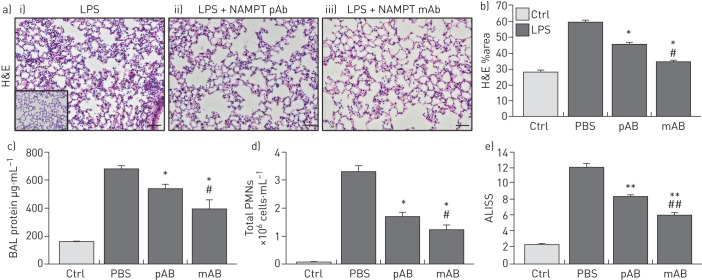

eNAMPT-neutralising strategies attenuate one-hit pre-clinical ARDS injury

H&E lung tissue staining from the one-hit LPS-challenged ARDS model show alveolar inflammation with significant neutrophil infiltration and alveolar oedema compared to control mice (inset) (figure 3a). Intravenous administration of either the eNAMPT-neutralising pAb (4 mg·kg−1) or the ALT-100 mAb (0.4 mg·kg−1) significantly reduced histological injury (figure 3a), which was verified by the significant reductions in LPS-induced inflammatory indices, i.e. BAL protein (figure 3c) and PMN counts (figure 3d). The lung protection afforded by ALT-100 mAb was significantly superior to the eNAMPT pAb as reflected either by H&E staining (figure 3b) or as captured in the integrated acute lung injury severity score or ALISS (H&E staining, BAL protein, BAL PMN counts, plasma IL-6 concentration) (figure 3e).

FIGURE 3.

Extracellular nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (eNAMPT)-neutralising strategies attenuate “one-hit” pre-clinical acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) injury. a) Haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) lung tissue staining from mice exposed to i) the one-hit lipopolysaccharide (LPS)/ARDS injury model (18 h) show interstitial and alveolar inflammation with significant neutrophil infiltration and alveolar oedema compared to control C57BL/6J mice (inset); the severity of LPS-induced histological injury is significantly reduced in mice receiving either ii) an intravenously administered eNAMPT-neutralisingpolyclonal antibody (pAb) (4 mg·kg−1, at time 0 with LPS injection) or iii) the humanised ALT-100 monoclonal antibody (mAb) (0.4 mg·kg−1, at time 0 with LPS injection) (n>5 mice per group). *: p<0.05 for LPS-Ab versus LPS-PBS control; #: p<0.05 for LPS-mAb versus LPS-pAb. b) The ALT-100 mAb was significantly more effective than the eNAMPT pAb in reducing LPS-induced histological evidence of inflammation and injury. *: p<0.05 versus LPS-PBS; #: p<0.05 mAb versus pAb. c), d) i.v. administration of either eNAMPT-neutralising biological intervention (pAb or mAb) significantly reduced LPS-induced increases in c) bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) protein and d) BAL polymorphonuclear cell (PMN) counts. *: p<0.05 versus LPS-PBS; #: p<0.05 mAb versus pAb. e) The superior efficacy of the humanised ALT-100 mAb compared to the eNAMPT pAb was again verified in an acute lung injury severity score (ALISS) comprising H&E staining, BAL protein, BAL PMN counts and interleukin-6 plasma levels. **: p<0.01 versus LPS-PBS, ##: p<0.01 mAb versus pAb. Scale bars=50 μm.

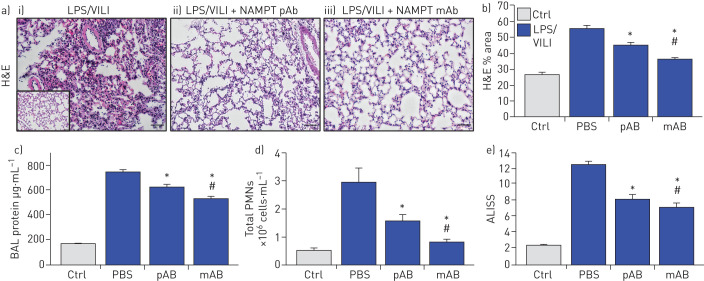

eNAMPT-neutralising strategies attenuate two-hit ARDS/VILI injury

H&E staining in mice exposed to the two-hit ARDS/VILI model (LPS exposure 22 h, ventilator exposure for the final 4 h) revealed significant inflammatory cell infiltration into the lung parenchyma accompanied by both interstitial and alveolar oedema when compared to control mice (inset) (figure 4a). As with the one-hit LPS model, the severity of histological injury in the two-hit LPS/VILI model was significantly reduced by i.v. delivery of either the eNAMPT-neutralising pAb (4 mg·kg−1) or the ALT-100 mAb (0.4 mg·kg−1) (figure 4a,b). Both eNAMPT-neutralising biologic strategies also significantly reduced BAL protein (figure 4c) and BAL PMN counts (figure 4d) with greater ALT-100 mAb-mediated protection compared with the pAb (figure 4e).

FIGURE 4.

Extracellular nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (eNAMPT)-neutralising strategies attenuate “two-hit” pre-clinical acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)/ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI). a) Haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) lung tissue staining analysis in i) mice exposed to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (0.1 mg·kg−1,18 h) followed by mechanical ventilation (4 h, tidal volume 20 mL·kg−1) were histologically compared to control C57BL/6J mice (inset), revealing significant parenchymal neutrophil infiltration and both interstitial and alveolar oedema. The severity of LPS/VILI histological injury was significantly reduced in mice receiving either ii) the eNAMPT-neutralising polyclonal antibody (pAb; 4 mg·kg−1, at time 0 with LPS) or iii) the humanised ALT-100 monoclonal antibody (mAb; 0.4 mg·kg−1, at time 0 with LPS). b) The ALT-100 mAb was significantly more effective than the pAb in reducing two-hit pre-clinical ARDS injury as captured by histological quantification of injury (Image J software). c),d) Both eNAMPT-neutralising biologic interventions (pAb or mAb) also significantly reduced two-hit ARDS/VILI-induced increases in c) BAL protein content and d) BAL polymorphonuclear cell (PMN) counts after the two-hit LPS/VILI model. e) Although both eNAMPT-neutralising biologic interventions (pAb, mAb) significant reduced LPS/VILI inflammatory injury, the ALT-100 mAb proved more effective than the eNAMPT pAb as verified in the acute lung injury severity score (ALISS) (n=5 mice per group). *: p<0.05 versus LPS/VILI-PBS, #: p<0.05 mAb versus pAb.

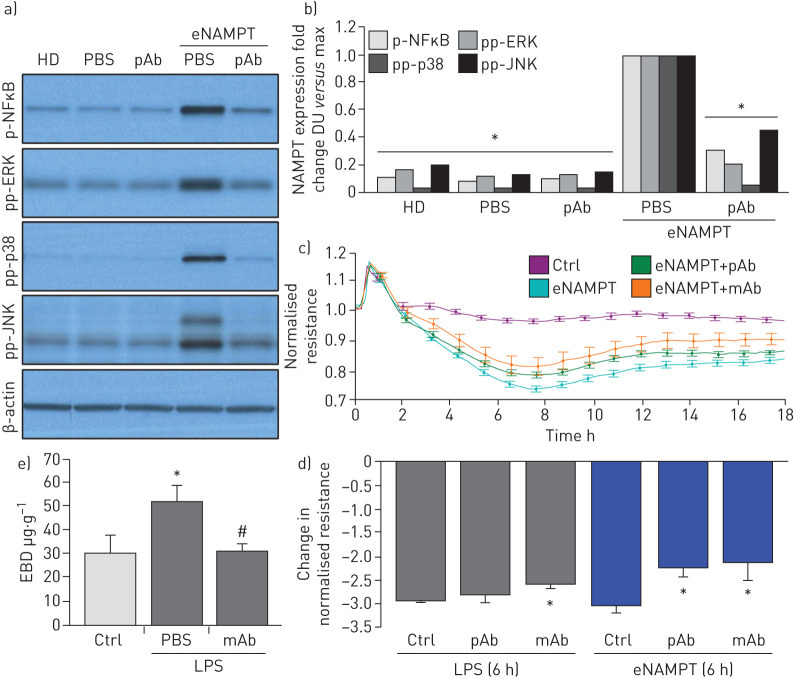

The eNAMPT neutralisation attenuates LPS- and LPS/VILI-challenged human lung EC signalling and barrier responses in vitro and in vivo

We demonstrated previously that NAMPT expression in a pre-clinical VILI model is primarily spatially localised to lung EC, lung epithelium and to resident and infiltrating leukocytes [13, 14]. We sought to specifically characterise lung endothelium as a target tissue for circulating eNAMPT and to assess the contribution of lung EC-derived NAMPT to the severity of acute lung injury in pre-clinical models of ARDS/VILI. Initial in vitro experiments utilising human lung EC confirmed that eNAMPT ligation of TLR4 induces robust NFκB phosphorylation [19] and MAP kinase activation (p38, JNK, p42/44 ERK) with these signalling responses nearly abolished by the eNAMPT-neutralising pAb (figure 5a,b), as were eNAMPT-induced declines in trans-human lung TER, reflecting pAb- and mAb-mediated protection against eNAMPT-induced loss of EC barrier integrity (figure 5c,d). The ALT-100 mAb, but not the eNAMPT-neutralising pAb, also produced significant reductions in LPS-induced barrier disruption (figure 5d), results consistent with the contributory role of LPS-mediated eNAMPT secretion (maximal at 4 h; figure 1e) in loss of EC barrier integrity and reductions in TER.

FIGURE 5.

Extracellular nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (eNAMPT)-neutralising strategies attenuate eNAMPT-induced human lung endothelial cell (EC) signalling and barrier responses. a),b) Human lung ECs were challenged with either human recombinant eNAMPT alone (1 μg·mL−1, 1 h) or an eNAMPT-polyclonal antibody (pAb) mixture (eNAMPT 1 μg·mL−1+pAb 10 μg·mL−1, 1 h). Cells were next lysed and probed for phospho-proteins and total β-actin via Western blot. eNAMPT-induced robust phosphorylation of NFκB, in addition to evidence of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase activation (pp-p38, pp-JNK, pp-42/44 extracellular signal regulating kinase (ERK)). Heat-denatured (100°C, 5 min) human recombinant eNAMPT (HD) (1 μg·mL−1, 1 h) served as a negative control confirming that eNAMPT effects do not reflect endotoxin contamination. The addition of the eNAMPT-neutralising pAb nearly totally abolished eNAMPT-induced NFκB phosphorylation and inhibited eNAMPT-induced MAP kinase activation detected by phosphorylation of ERK, p38 and JNK MAP kinases captured by densitometric measurements (n=3). c) In companion experiments, human lung ECs plated onto gold microelectrodes were challenged with either recombinant human eNAMPT alone (1 µg·mL−1), an eNAMPT-pAb mixture (eNAMPT 1 μg·mL−1 and pAb 10 μg·mL−1) or an eNAMPT-ALT-100 monoclonal antibody (mAb) mixture (eNAMPT 1 μg·mL−1 and ALT-100 10 μg·mL−1). Both eNAMPT-neutralising strategies, pAb and mAb, attenuated eNAMPT-induced declines in EC barrier integrity compared to eNAMPT alone. Human lung ECs on gold microelectrodes were also challenged with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (1 µg·mL−1), with either PBS, eNAMPT pAb (10 µg·mL−1) or ALT-100 mAb (10 µg·mL−1) added immediately after LPS stimulation. The ALT-100 mAb, but eNAMPT pAb, also produced significant reductions in LPS-induced declines in EC barrier integrity compared to LPS alone. For trans-endothelial electrical resistance (TER) studies, normalised resistance values >1 indicate lung EC barrier enhancement, normalised resistance values <1 indicate lung EC barrier disruption. d) Bar graph quantification of the TER declines and loss of barrier integrity, where data are expressed as change in TER compared to normalised unstimulated controls at 6 h (±sem, n=3 independent experiments per condition). *: p<0.05 agonist alone versus agonist-pAb or mAb. e) Lung tissue homogenates from “one-hit” LPS-challenged (1 mg·kg−1, 18 h) with and without treatment with the eNAMPT-neutralising mAb (0.4 mg·kg−1 at time 0 h) were evaluated for Evans blue dye (EBD) accumulation in lung tissues as a reflection of extravascular dye leakage and reported as the EBD concentration (μg·g−1 lung tissue) [55]. The bar graph demonstrates that the significant LPS-induced increases in EBD accumulation are abolished by prior addition of the ALT-10 mAb. *: p<0.05 LPS versus control; #: p<0.05 LPS versus LPS+mAb. DU: densitometric units.

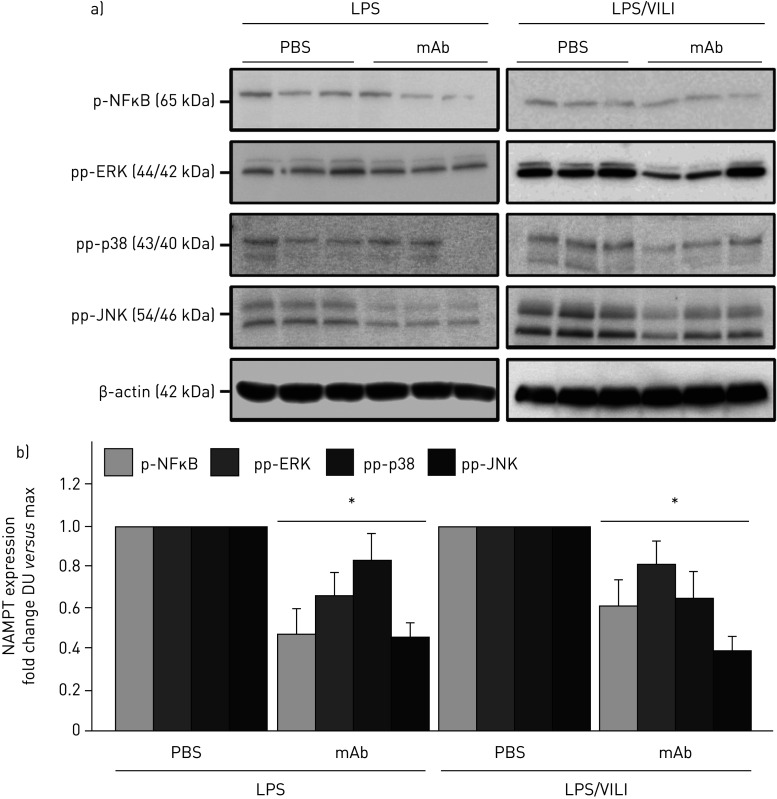

The contribution of circulating eNAMPT to the loss of lung vascular barrier integrity was next examined in vivo initially with the Evans blue dye accumulation in lung tissues, an index of vascular permeability, which demonstrated dramatic ALT-100 mAb-mediated restoration of EC barrier integrity in the one-hit (LPS) pre-clinical ARDS model (figure 5e). To validate our in vitro findings that specifically characterised increased MAP kinase signalling in eNAMPT-challenged lung endothelium, we examined levels of MAP kinase pathway signalling in lung tissues from mice exposed to both one-hit and two-hit pre-clinical ARDS models. Figure 6 demonstrates the activation of NFκB and MAP kinase family effectors (p38, JNK, p42/44 ERK), reflected by phosphorylation in lung tissue homogenates [19], in both pre-clinical ARDS models. Importantly, the ALT-100 mAb effectively suppressed the robust NFκB and MAP kinase family activation observed in the two ARDS models consistent with the contribution of circulating eNAMPT to the severity of lung injury in pre-clinical models of ARDS/VILI (figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

The extracellular nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT)-neutralising ALT-100 monoclonal antibody (mAb) attenuates mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase signalling in “one-hit” and “two-hit” pre-clinical acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)/ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI) models. a) Lung tissue homogenates from one-hit lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-exposed (1 mg·kg−1, 18 h) and two-hit LPS/VILI-exposed (LPS 22 h; mechanical ventilation 4 h, tidal volume 20 mL·kg−1) C57B6 wild-type mice were probed for phospho-proteins and total β-actin (Western blot). LPS- and LPS/VILI-challenged mice displayed robust NFκB and MAP kinase phosphorylation (pp-p38, pp-JNK, pp-42/44 extracellular signal regulating kinase (ERK)) as evidence of pathway activation. b) Treatment with the eNAMPT-neutralising ALT-100 mAb (0.4 mg·kg−1, at time 0 h) resulted in significant reductions in both NFκB and MAP kinase pathway activation in the one-hit- and two-hit-exposed mice captured by densitometric measurements (n=3). DU: densitometric units. *: p<0.05.

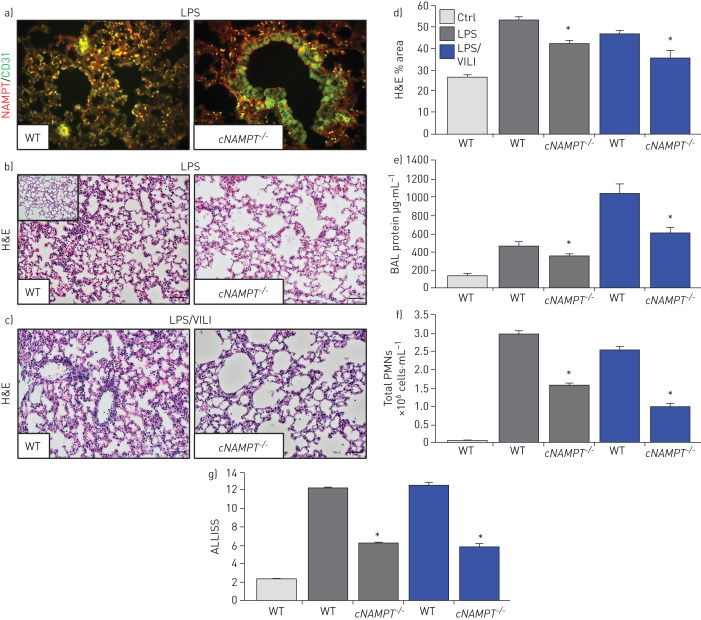

EC-specific NAMPT deletion in vivo reduces one-hit and two-hit lung injury

We utilised genetically engineered conditional EC-cNAMPT−/− knockout mice, with conditional NAMPT deletion restricted to EC, to further explore the contribution of lung EC-specific expression and secretion of NAMPT to the development of one-hit and two-hit lung injury. Lung tissue IHC studies demonstrated that tamoxifen-treated EC-cNAMPT−/− knockout mice exhibit selective loss of NAMPT staining in lung endothelium, whereas lung epithelial NAMPT expression was robust (figure 7a), reflecting conditional deletion of NAMPT expression in lung EC (compared to wild-type mice). Examination of H&E lung tissue staining in one-hit- or two-hit-exposed EC-cNAMPT−/− knockout mice showed significant reductions in inflammatory lung tissue injury (figure 7b–d), accompanied by reduced BAL protein levels (figure 7e) and BAL PMN counts (figure 7f) compared to similarly exposed littermate control mice. The significant protection afforded by EC-specific NAMPT deletion in EC-cNAMPT−/− mice was captured in the integrated lung injury severity score (ALISS, figure 7g).

FIGURE 7.

Endothelial cell (EC)-conditional nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase knockout (cNAMPT−/−) mice are significantly protected from lung injury in “one-hit” and “two-hit” acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) injury models. a) Lung tissue sections were obtained from EC-cNAMPT−/− mice sacrificed >2 weeks post-initiation of tamoxifen treatment (75 mg intraperitoneally daily for 1 week) and tissue slides prepared for dual immunohistochemical (IHC) staining with cell-specific double staining fluorescent-tagged NAMPT (green) and actin or CD-31 (red). In contrast to the dual staining in lung endothelium in littermate control sections (colocalised merge, left), tamoxifen-treated EC-cNAMPT−/− mice exhibit an absence of NAMPT staining in vascular cells while NAMPT staining in lung epithelium and leukocytes is prominent consistent with our original report [14]. These results reflect the targeted NAMPT deletion and absent expression in vascular endothelium. b–d) Haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of wild-type (WT) mice and EC-cNAMPT−/− mice exposed to b) the one-hit lipopolysaccharide (LPS) ARDS model or c) the two-hit LPS/ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI) model demonstrates significantly reduced inflammatory lung injury in mice with conditional deletion of EC NAMPT, d) summarised by Image J quantification. e–g) One-hit LPS- and two-hit LPS/VILI-exposed EC-cNAMPT−/− mice exhibit significant reductions in e) bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) protein levels and f) BAL polymorphonuclear cell (PMN) counts, g) with this protection captured in the integrated acute lung injury severity score (ALISS) score. *: p<0.05 EC-cNAMPT−/− versus similarly exposed littermates. Scale bars=50 μm.

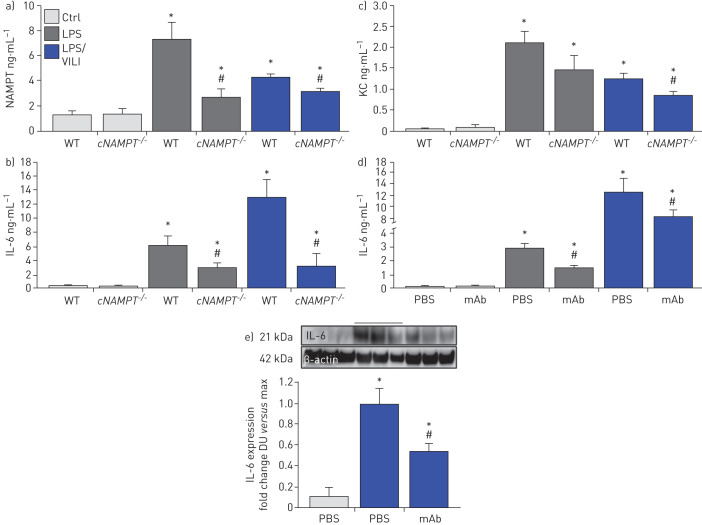

Lastly, we explored the involvement of EC-derived circulating eNAMPT to the severity of acute lung injury and measured eNAMPT plasma levels in one-hit- and two-hit-exposed EC-cNAMPT−/− and littermate control mice. Compared to littermate controls, both one-hit- and two-hit-exposed EC-cNAMPT−/− mice demonstrated reduced plasma eNAMPT levels (figure 8a) as well as reduced plasma levels of IL-6 and IL-8 (KC in mice), two inflammatory cytokines often implicated as components in the ARDS “cytokine storm” (figure 8b,c). Plasma levels of both IL-6 and IL-8 (KC) in one-hit- and two-hit-exposed WT C57Bl6 mice were also significantly reduced in ALT-100 mAb-treated mice compared to untreated mice (figure 8d), validated by the decreased IL-6 protein expression in two-hit ARDS-exposed mice treated with the eNAMPT-neutralising ALT-100 mAb (figure 8f).

FIGURE 8.

Endothelial cell nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT) deletion and the ALT-100 monoclonal antibody (mAb) reduce plasma and tissue cytokine expression in “one-hit”- and “two-hit”-exposed acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) mice. a) Plasma eNAMPT levels (ELISA) were significantly increased in one-hit- and two-hit-exposed littermate controls (Ctrl), with significantly reduced circulating eNAMPT levels in similarly exposed endothelial cell (EC)-cNAMPT−/− knockout mice. *: p<0.05 WT LPS or lipopolysaccharide (LPS)/ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI) versus wild-type (WT) Ctrl; #: p<0.05. EC-cNAMPT−/− versus one-hit/two-hit-exposed littermates. b),c) Plasma levels of the murine inflammatory cytokines, interleukin (IL)-6 and keratinocyte chemoattractant (KC) (IL-8) in one-hit- and two-hit-exposed EC-cNAMPT−/− knockout mice are reduced compared to similarly exposed littermates. d) Treatment with the eNAMPT-neutralising humanised ALT-100 mAb reduces the increase in plasma levels of IL-6 in C57B6 WT mice exposed to one-hit and two-hit pre-clinical ARDS injury models. *: p<0.05 LPS or LPS/VILI alone versus Ctrl; #: p<0.05 LPS or LPS/VILI mAb versus LPS or LPS/VILI alone. e) Western blot detection of IL-6 protein expression in lung tissue homogenates from one-hit LPS-exposed C57B6 WT mice shows significant ALT-100 mAb-mediated reductions in IL-6 expression captured by densitometric measurements (n=4). *: p<0.05 LPS/VILI alone versus Ctrl; #: p<0.05 LPS/VILI mAb versus LPS/VILI alone.

Discussion

Currently, there are no United States Food and Drug Administration-approved ARDS therapies, a serious unmet need that has been dramatically highlighted by the current COVID-19 pandemic. To potentially address the need for pharmacotherapies that reduce ARDS mortality, we previously identified eNAMPT, a novel DAMP [19], as a potentially attractive ARDS target whose expression and function are tightly linked to human ARDS. For example, NAMPT expression is highly induced by ARDS-relevant stimuli such as bacterial infection, hypoxia, shock, trauma and excessive mechanical stress produced by mechanical ventilation [20–23]. Furthermore, plasma levels of eNAMPT are a biomarker for ARDS severity [14, 17, 22, 29–31, 33], and NAMPT genotypes with elevated minor allelic frequencies (i.e. common single nucleotide polymorphisms) confer a significant risk of increased ARDS severity and mortality in both black and non-Hispanic white subjects [14, 17, 22, 29–31, 33]. Our earlier studies strongly implicated an essential contribution of eNAMPT to both VILI and ARDS pathobiology [14, 17, 22, 29–31, 33] via upstream activation of inflammatory cascades as a consequence of TLR4 ligation and NFκB transcriptional activities [19]. Thus, there is a substantial and compelling foundational basis for eNAMPT as a viable therapeutic target in ARDS/VILI.

Our current study underscores eNAMPT involvement in ARDS pathobiology in several important and novel ways. First, we utilised complementary approaches to validate increased NAMPT lung tissue expression in both one-hit (LPS) and two-hit (LPS/VILI) pre-clinical ARDS models. IHC and biochemical studies revealed markedly increased NAMPT lung tissue expression in both pre-clinical models. This was further verified utilising the radiolabelled probe, 99mTc-ProNamptor, with temporally increased LPS-induced NAMPT lung tissue expression that aligned with NAMPT expression in lung homogenates. As 99mTc-ProNamptor contains the radiolabelled eNAMPT-neutralising mAb (ALT-300), the potential exists for 99mTc-ProNamptor to serve as a novel molecular imaging theranostic that may therapeutically reduce inflammatory injury, a hypothesis to be addressed in future studies.

A second significant implication of this work is to extend our earlier studies in VILI murine models and directly explore eNAMPT-neutralisation as an effective ARDS therapy. Previous intratracheal instillation of an eNAMPT-neutralising polyclonal pAb supported eNAMPT as a relevant VILI therapeutic target [17, 19]. We now extend this work to demonstrate iv administration of ALT-100, the eNAMPT-neutralising humanised mAb, significantly reduced the severity of inflammatory lung injury in both pre-clinical ARDS models and was significantly more protective than the eNAMPT pAb. In addition, our use of dual pre-clinical ARDS models adds significant rigour to our work and directly addresses suggestions that a major failure of ARDS pharmacological interventions is due to the use of a single pre-clinical ARDS murine model [56, 57].

Our pre-clinical results support our nascent ARDS clinical trial strategy which is designed to deliver the ALT-100 mAb to ARDS subjects with respiratory failure at the time of intubation, i.e. prior to initiation of mechanical ventilation. This trial design specifically targets VILI prevention and the dampening of ventilator-induced amplification of inflammatory pathways to reduce multiorgan injury, thereby minimising the duration of mechanical ventilation, improving intensive care unit (ICU) survival and reducing healthcare costs. Prior unsuccessful ARDS therapeutic clinical trials, primarily targeting single cytokines or bacterial products, were probably hampered by delays in targeted therapy delivery [58, 59], with initiation of therapy well after the onset of amplified innate immunity-driven lung and systemic inflammatory pathways. The feasibility of administering ALT-100 to ARDS subjects with impending respiratory failure in the emergency room (ER) or upon entry to the ICU, prior to intubation and exposure to mechanical ventilation, was previously a daunting challenge from a clinical trial perspective, but is supported by recent ER–ICU clinical trials.

Another valuable insight provided by our study is to underscore the critical importance of EC-derived circulating eNAMPT to ARDS pathobiology [14, 35]. While NAMPT expression, in addition to lung ECs, is robust in lung alveolar epithelium and in resident and infiltrating leukocytes in VILI-challenged canine and murine models [13, 14], the critical contribution of each cellular component to ARDS severity was previously unknown. Our current in vitro and in vivo studies confirm earlier work that highlighted lung EC as a key eNAMPT cellular target with dysregulation of lung EC permeability responses [35]. We now show potent eNAMPT-mediated activation of human lung EC TLR4 and MAP kinase pathways and loss of EC barrier integrity, responses strongly abrogated by both eNAMPT-neutralising modalities (pAb, ALT-100 mAb). The modest but significant inhibition of LPS-induced declines in TER barrier dysfunction by ALT-100 mAb is again consistent with the contribution of eNAMPT, secreted by EC in response to LPS, to increased vascular permeability, supported by the profound reductions in Evans blue dye accumulation (figure 5e) and dramatic reductions in MAP kinase signalling in vivo (figure 6). To directly interrogate the role of EC-derived eNAMPT in vivo, we utilised an EC-cNAMPT−/− mouse line with targeted knockout of eNAMPT that is conditionally restricted to the endothelium. EC-cNAMPT−/− mice were significantly protected in both one-hit and two-hit pre-clinical ARDS injury models and exhibited significantly reduced plasma levels of eNAMPT, IL-6 and IL-8 (KC) when compared to WT littermates. These results mirror the reductions in plasma and tissue levels of IL-6 in ALT-100-treated mice exposed to one-hit and two-hit ARDS models indicating that EC-derived circulating eNAMPT is probably a significant contributor to ARDS pathobiology.

In summary, our studies strongly validate targeting of the eNAMPT/TLR4 inflammatory pathway with a humanised eNAMPT-neutralising mAb as a viable therapeutic strategy to address the serious unmet need for effective and specific pharmacological therapies to improve ARDS/VILI mortality. Additionally, we have clarified the essential and contributory role of EC-derived eNAMPT to inflammatory lung injury elicited by bacterial infection and by ventilator-induced mechanical stress. Finally, it is well known that the vast heterogeneity of ARDS has been a critical challenge to the conduct of successful therapeutic clinical trials in the U.S. and by ARDS clinical trial networks worldwide. Our study demonstrates that with the combined availability of 1) eNAMPT as an ARDS predictive plasma biomarker, either alone [14, 32, 33], or as part of an ARDS biomarker panel [31]; 2) identification of high-risk NAMPT genotypes [14, 29, 30]; and 3) a highly efficacious eNAMPT-neutralising humanised mAb as targeted biologic therapy, the opportunity exists for novel ARDS clinical trial designs for that stratify patient enrolment for testing a biologic therapy that targets the eNAMPT/TLR4 inflammatory pathway, an attractive mechanism to deliver personalised ICU medicine in the current COVID-19 pandemic landscape.

Supplementary material

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material ERJ-02536-2020.SUPPLEMENT (367KB, pdf)

Shareable PDF

Footnotes

This article has an editorial commentary: https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.04588-2020

This article has supplementary material available from erj.ersjournals.com

Author contributions: J.G.N. Garcia and S. Sammani: conception and design of the work, the analysis and interpretation of data for the work, the drafting and revision of the manuscript, approval of final version to be published; C. Bime, A.E. Cress, Z. Liu and D. Martin: conception and design of the work, the analysis and interpretation of data for the work, critical revision of key intellectual content and approval of final version to be published; T. Bermudez, S.M. Camp, A.N. Garcia, C.L. Kempf, H. Quijada, D.G. Valera and J.H. Song: collection and analysis of data, revision of the manuscript, and approval of the final version to be published; C. Barber, K. Burns, J.K. Burt, A.A. Desai, S.M. Dudek, E. Franco, A. Gaber, J.R. Jacobson, J.B. Mascarenhas, L. Moreno-Vinasco, V. Natarajan, R.C. Oita, V. Reyes Hernon, B. Sun and X. Sun: collected data and assisted with processing and manuscript revision

Conflict of interest: H. Quijada has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: T. Bermudez has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: C.L. Kempf has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: D.G. Valera has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: A.N. Garcia has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: S.M. Camp has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: J.H. Song has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: E. Franco has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: J.K. Burt has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: B. Sun has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: J.B. Mascarenhas has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: K. Burns has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: A. Gaber has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: R.C. Oita has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: V. Reyes Hernon has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: C. Barber has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: L. Moreno-Vinasco has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: X. Sun has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: A.E. Cress has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: D. Martin has investments in Aqualung, outside the submitted work.

Conflict of interest: Z. Liu has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: A.A. Desai reports grants from NIH R01 (HL136603) and consultancy for Novartis, outside the submitted work.

Conflict of interest: V. Natarajan has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: J.R. Jacobson has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: S.M. Dudek has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: C. Bime has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: S. Sammani has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: J.G.N. Garcia reports grants and non-financial support (provision of research materials) from Aqualung Therapeutics, Corp., during the conduct of the study; grants and personal fees from Aqualung Therapeutics, Corp., outside the submitted work; and has a US Patent No. 9,409,983 issued.

Support statement: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) grants P01HL126609, R01HL094394 and P01HL134610. Funding information for this article has been deposited with the Crossref Funder Registry.

References

- 1.Gong T, Liu L, Jiang W, et al. . DAMP-sensing receptors in sterile inflammation and inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Immunol 2020; 20: 95–112. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0215-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kono H, Rock KL. How dying cells alert the immune system to danger. Nat Rev Immunol 2008; 8: 279–289. doi: 10.1038/nri2215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathew G, Unnikrishnan MK. Multi-target drugs to address multiple checkpoints in complex inflammatory pathologies: evolutionary cues for novel ‘first-in-class' anti-inflammatory drug candidates: a reviewer's perspective. Inflamm Res 2015; 64: 747–752. 10.1007/s00011-015-0851-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Denning NL, Aziz M, Gurien SD, et al. . DAMPs, and NETs in sepsis. Front Immunol 2019; 10: 2536. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matthay MA, Zimmerman GA, Esmon C, et al. . Future research directions in acute lung injury: summary of a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute working group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003; 167: 1027–1035. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200208-966WS [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. . The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016; 315: 801–810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ware LB, Matthay MA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2000; 342: 1334–1349. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rubenfeld GD, Caldwell E, Peabody E, et al. . Incidence and outcomes of acute lung injury. N Engl J Med 2005; 353: 1685–1693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rubenfeld GD, Herridge MS. Epidemiology and outcomes of acute lung injury. Chest 2007; 131: 554–562. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zambon M, Vincent JL. Mortality rates for patients with acute lung injury/ARDS have decreased over time. Chest 2008; 133: 1120–1127. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rubartelli A, Lotze MT. Inside, outside, upside down: damage-associated molecular-pattern molecules (DAMPs) and redox. Trends Immunol 2007; 28: 429–436. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grigoryev DN, Ma SF, Irizarry RA, et al. . Orthologous gene-expression profiling in multi-species models: search for candidate genes. Genome Biol 2004; 5: R34. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-5-r34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simon BA, Easley RB, Grigoryev DN, et al. . Microarray analysis of regional cellular responses to local mechanical stress in acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2006; 291: L851–L861. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00463.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ye SQ, Simon BA, Maloney JP, et al. . Pre-B-cell colony-enhancing factor as a potential novel biomarker in acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005; 171: 361–370. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200404-563OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitra S, Wade MS, Sun X, et al. . GADD45a promoter regulation by a functional genetic variant associated with acute lung injury. PLoS One 2014; 9: e100169. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meyer NJ, Huang Y, Singleton PA, et al. . GADD45a is a novel candidate gene in inflammatory lung injury via influences on Akt signaling. FASEB J 2009; 23: 1325–1337. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-119073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hong SB, Huang Y, Moreno-Vinasco L, et al. . Essential role of pre-B-cell colony enhancing factor in ventilator-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008; 178: 605–617. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200712-1822OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao L, Flores C, Fan-Ma S, et al. . Macrophage migration inhibitory factor in acute lung injury: expression, biomarker, and associations. Transl Res 2007; 150: 18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2007.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Camp SM, Ceco E, Evenoski CL, et al. . Unique Toll-like receptor 4 activation by NAMPT/PBEF induces NFκB signaling and inflammatory lung injury. Sci Rep 2015; 5: 13135. doi: 10.1038/srep13135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adyshev DM, Elangovan VR, Moldobaeva N, et al. . Mechanical stress induces pre-B-cell colony-enhancing factor/NAMPT expression via epigenetic regulation by miR-374a and miR-568 in human lung endothelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2014; 50: 409–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elangovan VR, Camp SM, Kelly GT, et al. . Endotoxin- and mechanical stress-induced epigenetic changes in the regulation of the nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase promoter. Pulm Circ 2016; 6: 539–544. doi: 10.1086/688761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun X, Elangovan VR, Mapes B, et al. . The NAMPT promoter is regulated by mechanical stress, signal transducer and activator of transcription 5, and acute respiratory distress syndrome-associated genetic variants. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2014; 51: 660–667. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2014-0117OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun X, Sun BL, Babicheva A, et al. . Direct extracellular NAMPT involvement in pulmonary hypertension and vascular remodeling: transcriptional regulation by SOX and HIF-2α. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2020; 63: 92–103. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2019-0164OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Revollo JR, Grimm AA, Imai S. The regulation of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide biosynthesis by Nampt/PBEF/visfatin in mammals. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2007; 23: 164–170. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32801b3c8f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Revollo JR, Körner A, Mills KF, et al. . Nampt/PBEF/Visfatin regulates insulin secretion in β cells as a systemic NAD biosynthetic enzyme. Cell Metab 2007; 6: 363–375. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moreno-Vinasco L, Quijada H, Sammani S, et al. . Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase inhibitor is a novel therapeutic candidate in murine models of inflammatory lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2014; 51: 223–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oita RC, Camp SM, Ma W, et al. . Novel mechanism for nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase inhibition of TNF-α-mediated apoptosis in human lung endothelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2018; 59: 36–44. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2017-0155OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bajwa EK, Boyce PD, Januzzi JL, et al. . Biomarker evidence of myocardial cell injury is associated with mortality in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med 2007; 35: 2484–2490. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000281852.36573.22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bajwa EK, Yu CL, Gong MN, et al. . Pre-B-cell colony-enhancing factor gene polymorphisms and risk of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med 2007; 35: 1290–1295. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000260243.22758.4F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Mahony DS, Glavan BJ, Holden TD, et al. . Inflammation and immune-related candidate gene associations with acute lung injury susceptibility and severity: a validation study. PLoS One 2012; 7: e51104. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bime C, Casanova N, Oita RC, et al. . Development of a biomarker mortality risk model in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care 2019; 23: 410. doi: 10.1186/s13054-019-2697-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee K, Huh JW, Lim CM, et al. . Clinical role of serum pre-B cell colony-enhancing factor in ventilated patients with sepsis and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Scand J Infect Dis 2013; 45: 760–765. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2013.797600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee KA, Gong MN. Pre-B-cell colony-enhancing factor and its clinical correlates with acute lung injury and sepsis. Chest 2011; 140: 382–390. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-3100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garcia JG, Schaphorst KL, Verin AD, et al. . Diperoxovanadate alters endothelial cell focal contacts and barrier function: role of tyrosine phosphorylation. J Appl Physiol 2000; 89: 2333–2343. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.6.2333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ye SQ, Zhang LQ, Adyshev D, et al. . Pre-B-cell-colony-enhancing factor is critically involved in thrombin-induced lung endothelial cell barrier dysregulation. Microvasc Res 2005; 70: 142–151. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2005.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klohs J, Gräfe M, Graf K, et al. . In vivo imaging of the inflammatory receptor CD40 after cerebral ischemia using a fluorescent antibody. Stroke 2008; 39: 2845–2852. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.509844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Q, Wang F, Wu YS, et al. . Dual-color labeled anti-mucin 1 antibody for imaging of ovarian cancer: a preliminary animal study. Oncol Lett 2015; 9: 1231–1235. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.2807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim EJ, Park H, Kim J, et al. . 3,3'-diindolylmethane suppresses 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate-induced inflammation and tumor promotion in mouse skin via the downregulation of inflammatory mediators. Mol Carcinog 2010; 49: 672–683. doi: 10.1002/mc.20640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu Z, Wyffels L, Barber C, et al. . Characterization of 99mTc-labeled cytokine ligands for inflammation imaging via TNF and IL-1 pathways. Nucl Med Biol 2012; 39: 905–915. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2012.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Malviya G, D'Alessandria C, Bonanno E, et al. . Radiolabeled humanized anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody visilizumab for imaging human T-lymphocytes. J Nucl Med 2009; 50: 1683–1691. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.059485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ouadi A, Bekaert V, Receveur N, et al. . Imaging thrombosis with 99mTc-labeled RAM.1-antibody in vivo. Nucl Med Biol 2018; 61: 21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2018.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miller BW, Gregory SJ, Fuller ES, et al. . The iQID camera: an ionizing-radiation quantum imaging detector. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res A 2014; 767: 146–152. doi: 10.1016/j.nima.2014.05.070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Furenlid LR, Barrett HH, Barber HB, et al. . Molecular imaging in the College of Optical Sciences – an overview of two decades of instrumentation development. Proc SPIE Int Soc Opt Eng 2014; 9186: 91860J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Han L, Miller BW, Barber HB, et al. . A new columnar CsI(Tl) scintillator for iQID detectors. Proc SPIE Int Soc Opt Eng 2014; 9214: 92140D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Korhonen H, Fisslthaler B, Moers A, et al. . Anaphylactic shock depends on endothelial Gq/G11. J Exp Med 2009; 206: 411–420. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goldman JL, Sammani S, Kempf C, et al. . Pleiotropic effects of interleukin-6 in a ‘two-hit' murine model of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Pulm Circ 2014; 4: 280–288. doi: 10.1086/675991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Letsiou E, Rizzo AN, Sammani S, et al. . Differential and opposing effects of imatinib on LPS- and ventilator-induced lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2015; 308: L259–L269. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00323.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rizzo AN, Sammani S, Esquinca AE, et al. . Imatinib attenuates inflammation and vascular leak in a clinically relevant two-hit model of acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2015; 309: L1294–L1304. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00031.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peng X, Hassoun PM, Sammani S, et al. . Protective effects of sphingosine 1-phosphate in murine endotoxin-induced inflammatory lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004; 169: 1245–1251. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200309-1258OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Geraci-Erck M. Immunohistochemistry Research Applications for Animal Tissue. National Society of Histotechnology 32nd Symposium, Portland, OR, USA. June 16–20, 2013. Workshop #82: 1–67.

- 51.Jensen EC. Quantitative analysis of histological staining and fluorescence using ImageJ. Anat Rec 2013; 296: 378–381. doi: 10.1002/ar.22641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Matute-Bello G, Downey G, Moore BB, et al. . An official American Thoracic Society workshop report: features and measurements of experimental acute lung injury in animals. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2011; 44: 725–738. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0210ST [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dudek SM, Jacobson JR, Chiang ET, et al. . Pulmonary endothelial cell barrier enhancement by sphingosine 1-phosphate: roles for cortactin and myosin light chain kinase. J Biol Chem 2004; 279: 24692–24700. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313969200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Garcia JG, Liu F, Verin AD, et al. . Sphingosine 1-phosphate promotes endothelial cell barrier integrity by Edg-dependent cytoskeletal rearrangement. J Clin Invest 2001; 108: 689–701. doi: 10.1172/JCI12450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moitra J, Sammani S, Garcia JG. Re-evaluation of Evans Blue dye as a marker of albumin clearance in murine models of acute lung injury. Transl Res 2007; 150: 253–265. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2007.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jagrosse ML, Dean DA, Rahman A, et al. . RNAi therapeutic strategies for acute respiratory distress syndrome. Transl Res 2019; 214: 30–49. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2019.07.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oakley C, Koh M, Baldi R, et al. . Ventilation following established ARDS: a preclinical model framework to improve predictive power. Thorax 2019; 74: 1120–1129. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2019-213460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fuller BM, Mohr NM, Hotchkiss RS, et al. . Reducing the burden of acute respiratory distress syndrome: the case for early intervention and the potential role of the emergency department. Shock 2014; 41: 378–387. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Malaviya R, Laskin JD, Laskin DL. Anti-TNFα therapy in inflammatory lung diseases. Pharmacol Ther 2017; 180: 90–98. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material ERJ-02536-2020.SUPPLEMENT (367KB, pdf)

This one-page PDF can be shared freely online.

Shareable PDF ERJ-02536-2020.Shareable (231.1KB, pdf)