Abstract

Background

Pexidartinib is approved in the U.S. for tenosynovial giant cell tumors (TGCTs). Herein, we assessed the hepatic safety profile of pexidartinib across patients with TGCTs receiving pexidartinib.

Materials, and Methods

Hepatic adverse reactions (ARs) were assessed by type and magnitude of liver test abnormalities, classified as (a) isolated aminotransferase elevations (alanine [ALT] or aspartate [AST], without significant alkaline phosphatase [ALP] or bilirubin elevations), or (b) mixed or cholestatic hepatotoxicity (increase in ALP with or without ALT/AST and bilirubin elevations, based on adjudication). Median follow‐up from initial pexidartinib treatment was 39 months (range, 32–82) in 140 patients with TGCTs across clinical studies NCT01004861, NCT02371369, NCT02734433, and NCT03291288.

Results

In total, 95% of patients with TGCTs (133/140) treated with pexidartinib (median duration of exposure, 19 months [range, 1–76]), experienced a hepatic AR. A total of 128 patients (91%) had reversible, low‐grade dose‐dependent isolated AST/ALT elevations without significant ALP elevations. Five patients (4%) experienced serious mixed or cholestatic injury. No case met Hy's law criteria. Onset of hepatic ARs was predominantly in the first 2 months. All five serious hepatic AR cases recovered 1–7 months following pexidartinib discontinuation. Five patients from the non‐TGCT population (N = 658) experienced serious hepatic ARs, two irreversible cases.

Conclusion

This pooled analysis provides information to help form the basis for the treating physician's risk assessment for patients with TCGTs, a locally aggressive but typically nonmetastatic tumor. In particular, long‐term treatment with pexidartinib has a predictable effect on hepatic aminotransferases and unpredictable risk of serious cholestatic or mixed liver injury.

Implications for Practice

This is the first long‐term pooled analysis to report on the long‐term hepatic safety of pexidartinib in patients with tenosynovial giant cell tumors associated with severe morbidity or functional limitations and not amenable to improvement with surgery. These findings extend beyond what has been previously published, describing the observed instances of hepatic toxicity following pexidartinib treatment across the clinical development program. This information is highly relevant for medical oncologists and orthopedic oncologists and provides guidance for its proper use for appropriate patients within the Pexidartinib Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Safety program.

Keywords: Hepatic safety, Adverse reactions, Long‐term, Pexidartinib, Tenosynovial giant cell tumor

Short abstract

Pexidartinib is approved in the U.S. for treatment of tenosynovial giant cell tumors (TGCT). This article assesses the hepatic safety profile of pexidartinib in TGCT cases and describes risk mitigation procedures designed to identify any instances of serious liver injury as early as possible to better inform prescribers and patients about this drug.

Introduction

Tenosynovial giant cell tumor (TGCT), also known as pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS)/diffuse type TGCT or giant cell tumor of tendon sheath/localized‐TGCT, is a rare monoarticular disease primarily affecting the synovial lining of joints, bursae, or tendon sheaths [1, 2, 3]. It is characterized by overexpression of the colony‐stimulating factor 1 (CSF1) protein [1, 4, 5, 6]. Systemic therapies, particularly tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) targeting CSF1/CSF1 receptor (CSF1R) signaling pathways, have shown promising results as novel treatment options in patients with TGCTs [3, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16].

Pexidartinib was developed as a novel orally administered small‐molecule TKI with selective activity against the CSF1R. It is the first U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved systemic therapy for TGCT, recently added by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network as a category 1 recommendation for the treatment of adult patients with symptomatic TGCT/PVNS associated with severe morbidity or functional limitations not amenable to improvement with surgery [17, 18]. Treatment with TKIs has been associated with the risk of serious adverse events, including hepatotoxicity [6, 9, 10, 16, 19, 20, 21]. Two clinically distinct types of hepatic adverse reactions (ARs) were observed with pexidartinib: (a) reversible aminotransferase elevations that are frequently seen and attributed to CSF1R inhibition and, less frequently, (b) mixed or cholestatic hepatotoxicity that is unpredictable and may lead to irreversible liver injury, including vanishing bile duct syndrome (VBDS) [6, 14]. The exact mechanism of these liver abnormalities and impact of developing liver injury on clinical outcomes remain unknown.

The aim was to assess the hepatic safety profile of pexidartinib in TGCT cases and describe the risk mitigation procedures designed to identify any instances of serious liver injury as early as possible, to better inform prescribers and patients about this drug.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Participants

This retrospective pooled analysis evaluated hepatic ARs that developed in pexidartinib‐treated patients with TGCTs. Key eligibility criteria and study designs for the PLX108‐01 extension (NCT01004861) [6] and ENLIVEN (NCT02371369) [14] study have been reported and are summarized in Table 1. Furthermore, patients with TGCTs from two additional studies (NCT02734433 [22] and NCT03291288 [23]) were included (Table 1). Briefly, patients were > 18 years, with histologically confirmed TGCT that was symptomatic, and for which surgery was not recommended or potentially associated with worse function or severe morbidity. Patients enrolled had aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels ≤1.5× upper limit of normal (ULN) and total bilirubin (TBIL) was ≤1.5× ULN. Select previously reported serious hepatic AR cases are described in pexidartinib‐treated patients without TGCTs in supplemental online Table 1 [23].

Table 1.

Summary of pooled studies (TGCT population)

| Study ID (NCT no.) | Study title | Study design | Dosing regimen for patients with TGCTs |

|---|---|---|---|

|

PLX108‐01 (NCT01004861) [6] |

A phase 1 study to assess safety, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of PLX3397 in patients with advanced, incurable, solid tumors in which the target kinases are linked to disease pathophysiology | Phase I, first in‐human study with a dose escalation (part 1) and extension (part 2); 16 additional patients were added after the interim cutoff date: April 14, 2014 | Part 2: pexidartinib (n = 39), 1,000 mg/d (split dose) |

| ENLIVEN(NCT02371369) [14] | Pexidartinib versus placebo for advanced tenosynovial giant cell tumor (ENLIVEN): a randomized phase 3 trial | Phase III, multicenter study with 2 parts: randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled part and open‐label, long‐term part | Part 1 (n = 61):pexidartinib: 1,000 mg/d (split dose) for 2 weeks, then pexidartinib: 800 mg/d (split dose) or matching placebo for 22 weeks. Part 2 (n = 30): pexidartinib: 800 mg/d (400 mg BID) |

|

PL3397‐A‐A103 (NCT02734433) [22] |

A phase 1 study of single agent pexidartinib in asian subjects with advanced solid tumors | Phase I, nonrandomized, open‐label, multiple‐dose study of pexidartinib in Asian patients with advanced solid tumors. Dose‐escalation 3 + 3 design. 2 dose levels (cohort 1, 600 mg/d [n = 3] and cohort 2, 1000 mg/d [n = 8]) to assess the safety and tolerability, RP2D, PK and PD, and preliminary antitumor activity of pexidartinib | n = 1 (part of cohort 1). Cohort 1: 600 mg/d (200 mg in the morning and 400 mg in the evening) |

| PL3397‐A‐U126 (NCT03291288) [23] | An open‐label, single sequence, crossover study assessing the effect of pexidartinib on the pharmacokinetics of midazolam and S‐warfarin in patients | Single‐sequence, crossover study will comprise 2 parts: part 1: an initial single‐sequence crossover part to evaluate the effect of pexidartinib on the PK of midazolam and S‐warfarin (DDI phase); part 2: an evaluation of efficacy and safety of pexidartinib treatment in various tumors | Pexidartinib: 400 mg BID from day 5; midazolam: 2 mg on days 1, 5, and 15; S‐warfarin: 10 mg on days 1, 5, and 15 |

Abbreviations: BID, twice daily; d, day; DDI, drug‐drug interaction; ID, identifier; PD, pharmacodynamics; PK, pharmacokinetics; RP2D, recommended phase 2 dose; TGCT, tenosynovial giant cell tumor.

Assessments and Statistical Analysis

Hepatic ARs were assessed by type and magnitude of liver test abnormalities, classified as (a) aminotransferase elevations (in the absence of significant alkaline phosphatase [ALP] or bilirubin elevations) or (b) mixed or cholestatic hepatotoxicity (increase in ALP with or without aminotransferase elevations) [23]. Hepatic ARs were examined by three hepatotoxicity experts with extensive experience evaluating drug‐induced liver injury who composed the pexidartinib Hepatic Event Adjudication Committee (HEAC) that supported the comprehensive evaluation of hepatic safety data across the pexidartinib clinical program. The HEAC assessed severe hepatic events for type of liver injury and potential relatedness to pexidartinib treatment. The HEAC provided advice on identification, management, and risk mitigation of drug‐induced hepatic events. As a postapproval recommendation to manage hepatic ARs and the risk of mixed or cholestatic hepatotoxicity, pexidartinib dose modification criteria have been carefully defined according to the type and magnitude of liver test abnormality [17].

Dose reductions and modifications were based on prescribing information recommendations [17]. A Hy's law case was defined as any patient presenting with ALT or AST ≥3× ULN with TBIL ≥2× ULN, and ALP ≤2× ULN [24]. The data cutoff for the hepatic ARs analysis was May 31, 2019.

Descriptive statistics were calculated including median (range), and Kaplan‐Meier curves were plotted for the time from the start of pexidartinib treatment to first occurrence of hepatic ARs based on lab values criteria.

Results

Patient Characteristics

In all, 140 patients with TGCTs who received pexidartinib (starting dose of 600–1,000 mg per day) were included, with demographics and baseline disease characteristics summarized in Table 2. The median age was 44 years (range, 18–80). Median duration of exposure to pexidartinib was 19 months (range, 1–76), with a median follow‐up from initial pexidartinib treatment of 39 months (range, 32–82). Treatment was ongoing in 60 patients (43%) as of the May 2019 cutoff.

Table 2.

Patient demographics and baseline disease characteristics

| Characteristic | ENLIVEN randomized (1,000 mg/d), n = 61 | ENLIVEN crossover (800 mg/d), a n = 30 | PLX108‐01 TGCT cohort (1,000 mg/d), a n = 39 | Other phase 1 (600 or 800 mg/d), a n = 10 b | Pooled, N = 140 c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (range), yr | 44 (22–75) | 47 (20–79) | 42 (22–80) | 25 (18–57) | 44 (18–80) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||||

| Male | 26 (43) | 14 (47) | 17 (44) | 3 (30) | 60 (43) |

| Female | 35 (57) | 16 (53) | 22 (56) | 7 (70) | 80 (57) |

| Race, n (%) | |||||

| White | 52 (85) | 30 (100) | 33 (85) | 6 (60) | 121 (86) |

| Black | 3 (5) | 0 | 3 (8) | 0 | 6 (4) |

| Asian | 1 (2) | 0 | 3 (8) | 4 (40) | 8 (6) |

| Native American | 2 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (1) |

| Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 2 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (1) |

| Multiracial | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Geographic region, n (%) | |||||

| U.S. region | 23 (38) | 13 (43) | 39 (100) | 6 (60) | 81 (58) |

| Non‐U.S. region | 38 (62) | 17 (57) | 0 | 4 (40) | 59 (42) |

| Disease location, n (%) d | |||||

| Knee | 34 (56) | 19 (63) | 21 (54) | 0 | 74 (56) |

| Ankle | 14 (23) | 3 (10) | 7 (18) e | 0 | 24 (18) |

| Hip | 6 (10) | 3 (10) | 7 (18) f | 0 | 16 (12) |

| Other g | 7 (11) | 5 (17) | 4 (10) | 1 (100) | 16 (12) |

| Prior surgeries for TGCT, n (%) | |||||

| Yes | 32 (52) | 14 (47) | 31 (79) | 7 (70) | 84 (60) |

| No | 29 (48) | 16 (53) | 8 (21) | 3 (30) | 56 (40) |

| Prior systemic therapy, n (%) d | |||||

| Yes h | 8 (13) | 2 (7) | 6 (15) | 0 | 16 (12) |

| No | 53 (87) | 28 (93) | 33 (85) | 1 (100) | 115 (88) |

Starting dose.

For disease location and prior systemic therapy, patient information only available for one patient from A‐103 study. Not collected from nine patients with TGCTs in PL3397‐A‐U126.

For disease location and prior systemic therapy, patient information not collected from nine patients with TGCTs in PL3397‐A‐U126 study. Total patients for those characteristics = 131.

Not collected in study PL3397‐A‐U126.

Included foot/ankle.

Included hip/thigh.

Included wrist, shoulder, spine, finger, and elbow.

Included nilotinib (n = 1) or imatinib (n = 7) in ENLIVEN and imatinib or nilotinib (n = 4) or denosumab or sirolimus (n = 2) in PLX108‐01.

Abbreviation: d, day; TGCT, tenosynovial giant cell tumor.

Characterization of Liver Test Abnormalities

Nearly all patients (n = 133, 95%) experienced liver test abnormalities, of whom 128 experienced aminotransferase elevations. Most (66%) experienced an isolated ALT or AST increase of ≥1 to <3× ULN, with 11% experiencing increases ≥3 to <5× ULN in the absence of TBIL ≥2 ULN (Table 3). Aminotransferase elevations were dose‐dependent and responsive to dose reductions, usually persisted at low‐grade levels with continued treatment, and resolved upon treatment interruption.

Table 3.

Frequency of liver test abnormalities

| Clinical parameter a | ENLIVEN randomized (1,000 mg/d),b n = 61 | ENLIVEN crossover (800 mg/d), b n = 30 | PLX108‐01 TGCT cohort (1,000 mg/d), b n = 39 | Other phase I (600 or 800 mg/d), b n = 10 | Total, c N = 140 d | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aminotransferase evaluations, n (%) a | ||||||||||

| ALT or AST | ||||||||||

| ≥ 1 to <3× ULN | 39 (64) | 21 (70) | 26 (67) | 7 (70) | 93 (66) | |||||

| ≥ 3 to <5× ULN | 7 (12) | 4 (13) | 4 (10) | 1 (10) | 16 (11) | |||||

| ≥ 5 to <10× ULN | 6 (10) | 2 (7) | 2 (5) | 1 (10) | 11 (8) | |||||

| ≥ 10 to <20× ULN | 3 (5) | 1 (3) | 2 (5) | 0 | 6 (4) e | |||||

| ≥ 20× ULN | 2 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (1) f | |||||

| Mixed or cholestatic hepatotoxicity, n (%) | ||||||||||

| ALT or AST ≥3×, TBIL ≥2×, and ALP ≤2× ULN (true Hy's law) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| ALT or AST ≥3×, TBIL ≥2×, and ALP >2× ULN | 3 (5) | 0 | 1 (3) | 1 (10) | 5 (4) g | |||||

| TBIL ≥2× ULN (in absence of ALT ≥3× or ALP >2× ULN) | 0 | 0 | 1 (3) | 0 | 1 (1) | |||||

| Hepatic abnormalities, n (%) h | Grade 1 or 2 | Grade ≥ 3 | Grade 1 or 2 | Grade ≥ 3 | Grade 1 or 2 | Grade ≥ 3 | Grade 1 or 2 | Grade ≥ 3 | Grade 1 or 2 | Grade ≥ 3 |

| AST | 48 (79) | 8 (13) | 25 (83) | 2 (7) | 30 (77) | 4 (10) | 8 (80) | 1 (10) | 111 (79) | 15 (11) i |

| ALT | 28 (46) | 14 (23) | 18 (60) | 3 (10) | 16 (41) | 3 (8) | 2 (20) | 2 (20) | 64 (46) | 22 (16) j |

| ALP | 21 (34) | 3 (5) | 9 (30) | 0 | 9 (23) | 1 (3) | 1 (10) | 1 (10) | 40 (29) | 5 (4) k |

| TBIL | 5 (8) | 2 (3) | 1 (3) | 0 | 3 (8) | 2 (5) | 0 | 1 (10) | 9 (6) | 5 (4) l |

| DBIL m | 6 (10) | 4 (7) | 2 (7) | 0 | 3 (8) | 4 (10) | 0 | 0 | 11 (8) | 8(6) n |

Patients who had isolated aminotransferase elevations were separate from those who had mixed or cholestatic hepatotoxicity.

Pexidartinib starting dose.

Includes one patient with a single time point elevation of TBIL considered unrelated to treatment.

Women (n = 80); men (n = 60).

5 women (6%) and 1 man (2%) experienced ALT or AST elevations of ≥10 to <20× ULN.

Both patients were female.

4 women (5%) and 1 man (2%) experienced mixed or cholestatic hepatotoxicity

Graded per NCI CTCAE v. 4.03.

13 women (17%) and 2 men (3%) experienced grade ≥ 3 AST elevations.

16 women (20%) and 6 men (10%) experienced grade ≥ 3 ALT elevations.

5 women (6%) and no men experienced grade ≥ 3 ALP elevations.

4 women (5%) and 1 man (2%) experienced grade ≥ 3 TBIL elevations.

Direct bilirubin is not collected in study PL3397‐A‐U126. The number of patients who have at least one baseline and postbaseline value = 130.

6 women (8%) and 2 men (4%) experienced grade ≥ 3 DBIL elevations.

Abbreviations: ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; d, day; DBIL, direct bilirubin; NCI CTCAE, National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events; TBIL, total bilirubin; TGCT, tenosynovial giant cell tumor; ULN, upper limit of normal.

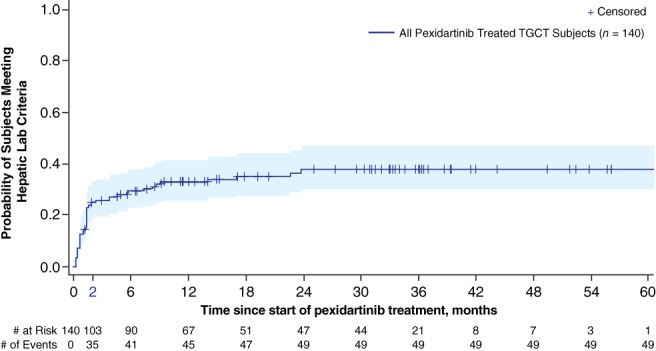

Individual laboratory abnormalities were assessed across the pooled studies. AST increase was the most common hepatic laboratory abnormality, occurring in 126 patients (90%), with mostly grade 1. ALT was increased in 86 patients (61%), and ALP was increased in 45 patients (32%). Most ALT and ALP elevations were also low grade. Increased direct bilirubin (DBIL) and TBIL occurred in 19 patients (15%) and 14 patients (10%), respectively (Table 3). Regarding gender‐based differences and specifically grade ≥ 3 laboratory abnormalities, women compared with men experienced a higher percentage of ALT elevations (17% vs. 3%), AST elevations (20% vs. 10%), ALP elevations (6 vs. 0%), TBIL elevations (5% vs. 2%), and DBIL elevations (8% vs. 4%) (Table 3). Increased partial thromboplastin time and international normalized ratio occurred in 13% and 11% of patients with TGCTs, respectively, with all cases being grade 1 (supplemental online Table 2). The time to first occurrence of any of these laboratory criteria was predominantly in the first 2 months of treatment (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Kaplan‐Meier curve of time to first occurrence of hepatic adverse reactions. Hepatic Laboratory Criteria: alanine aminotransferase >3× upper limit of normal (ULN), or aspartate aminotransferase >3× ULN, or alkaline phosphatase (ALP) >2× ULN, or total bilirubin > ULN, or direct bilirubin > ULN. If ALP >2× ULN and gamma‐glutamyl transferase (GGT) is measured on the same date, GGT must also be >2× ULN.Abbreviation: TGCT, tenosynovial giant cell tumor.

Mixed or Cholestatic Hepatotoxicity

Of the 140 patients with TCGTs treated with pexidartinib, 5 (4%) were adjudicated as experiencing drug‐related mixed or cholestatic hepatotoxicity and are described individually below (Table 4). None of these patients met strict Hy's law criteria (ALT or AST ≥3×, TBIL ≥2×, and ALP ≤2× ULN) [24]. The onset of these serious hepatic ARs occurred only within the first 2 months of pexidartinib treatment. Four of the five cases were experienced in female patients.

Table 4.

Patients with TGCTs with serious hepatic adverse reactions

| TGCT Cases | Pexidartinib Starting Dose (Onset) | Type of Hepatic Injury, R value a | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| ENLIVEN | |||

| No. 1. 75‐yr‐old woman | 1,000 mg/d (d 22) | Cholestatic hepatotoxicity (biopsy: ductopenia, severe cholestasis), Hyperbilirubinemia, R value 5.9 = hepatocellular | Recovered 7 mo |

| No. 2. 52‐yr‐old man | 1,000 mg/d (d 36) | Mixed hepatotoxicity, Hyperbilirubinemia, R value 4.2 = mixed | Recovered 2 mo |

| No. 3. 67‐yr‐old woman | 1,000 mg/d (d 43) | Mixed hepatotoxicity, Hyperbilirubinemia, R value 3.8 = mixed | Recovered 1 mo |

| No. 4. 39‐yr‐old woman | 1,000 mg/d (d 28) | Cholestatic hepatotoxicity, Intermittent ALP increases due to 2 rechallenges, R value 4.4 = mixed | Recovered 2 mo |

| PL3397‐A‐U126 (NCT03291288) | |||

| No. 5. 43‐year‐old woman | 800 mg/d (d 21) | Mixed hepatotoxicity, Hyperbilirubinemia, R value <2 = cholestatic | Recovered 2 mo |

R value is at the time of initial event.

Abbreviations: ALP, alkaline phosphatase; d, day; mo, month(s); R, ratio; TGCT, tenosynovial giant cell tumor.

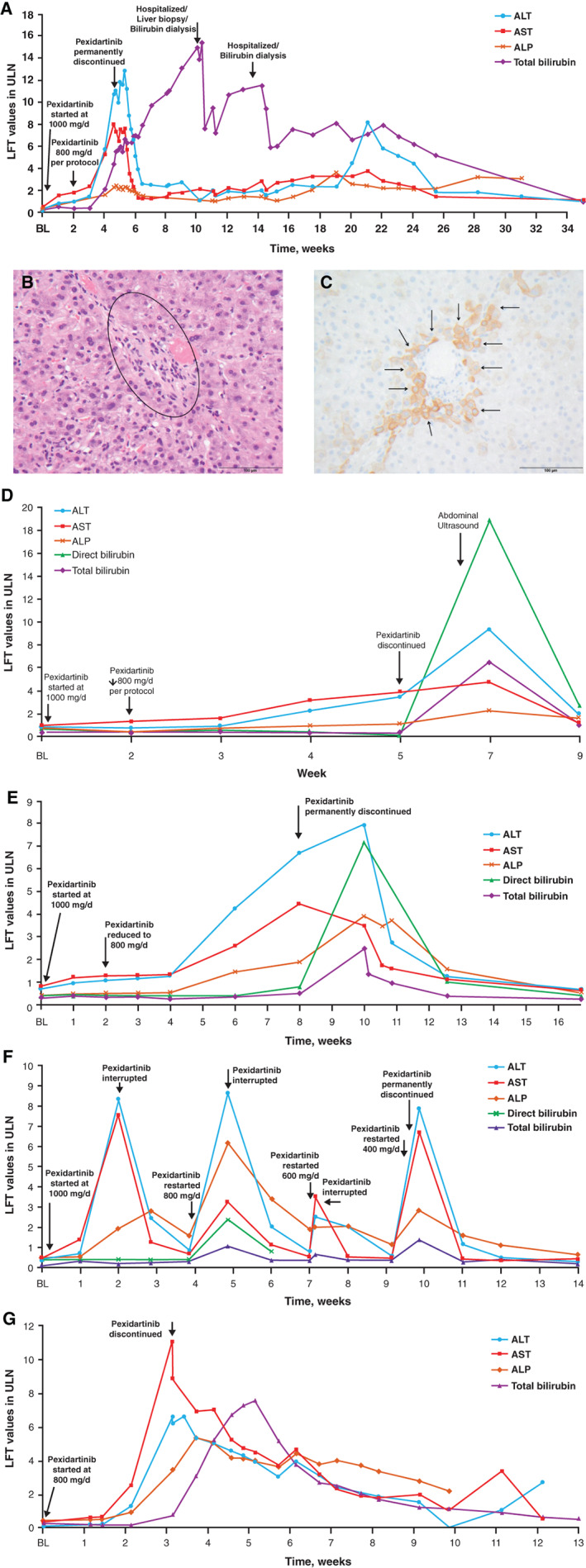

Each of these patients eventually discontinued pexidartinib treatment permanently. Four of these cases had ALT or AST ≥3× ULN, TBIL ≥2× ULN, and ALP >2× ULN (Fig. 2; Table 3), and the remaining case had TBIL between 1 and 2× ULN. Four of these patients started pexidartinib at a dose of 1,000 mg per day (all in ENLIVEN), and the other started pexidartinib at a dose of 800 mg per day (Study PL3397‐A‐U126). Mixed or cholestatic liver injury was diagnosed by determining ratio (R) values, calculated by dividing peak ALT/ULN by peak ALP/ULN. R values of 2 to 5 are considered mixed, R values <2 are considered cholestatic, and R values >5 are considered hepatocellular [25]. Serum bilirubin does not define any of the injury patterns, but accompanying hyperbilirubinemia is a sign of more serious hepatotoxicity and may indicate impaired hepatic function.

Figure 2.

Clinical laboratory results of patients with tenosynovial giant cell tumors (TGCTs) experiencing serious hepatic adverse reactions. (A): Case no. 1. (B): Case no. 1: H&E: portal tract (black circle) without a bile duct or ductular proliferation but with few inflammatory cells. 400× magnification. (C): Case no. 1: immunohistochemical staining against CK7. Portal tract shows loss of bile duct but CK7‐positive adjacent hepatocytes indicating chronic cholestasis (arrows). 400× magnification. (D): Case no. 2. (E): Case no. 3. (F): Case no. 4. (G): Case no. 5.Abbreviations: ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BL, baseline; CK7, cytokeratin 7; d, day; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; LFT, liver function test; ULN, upper limit of normal.

The first and most prolonged case occurred in a 75‐year‐old White woman (case 1). The total duration of treatment was 31 days, and starting on day 22, the patient experienced fatigue, diarrhea, and nausea. Lab tests revealed cholestatic jaundice with TBIL 15× ULN (Fig. 2A) and DBIL 84× ULN. At the time of admission (day 31), laboratory values were AST (281 U/L, 7.5× ULN), ALT (376 U/L, 9.3× ULN), and ALP (231 U/L, 2.3× ULN), R value 4.0: mixed. This case was initially classified as acute hepatocellular and evolved into mixed and cholestatic injury. She underwent bilirubin dialysis and a liver biopsy that showed severe cholestasis, mild fatty transformation, and changes suggestive of significant VBDS, implicating specific damage of cholangioepithelium (Fig. 2B, C). After 7 months, the patient recovered, with all liver biochemical tests (ALT, AST, ALP, TBIL) returning to within the normal ranges (Fig. 2A).

The second patient (case 2) was a 52‐year‐old White man who discontinued pexidartinib on day 36 of treatment because of elevated liver tests and symptoms of jaundice, pruritus, and nausea. Laboratory values revealed peak elevations of ALT 9.3× ULN, AST 4.8× ULN, ALP 2.2× ULN, TBIL 6.5× ULN, and DBIL 18.8× ULN (R value 4.2: mixed) at 7 weeks after the start of pexidartinib treatment. Following the discontinuation of pexidartinib, he recovered fully within 2 months (Fig. 2D).

The third patient (case 3) was a 67‐year‐old White woman who discontinued treatment 8 weeks after the start of pexidartinib because of laboratory results that showed gamma‐glutamyl transferase (GGT) 17.9× ULN, ALP 2.1× ULN, ALT 7.9× ULN, and AST 4.7× ULN (R value 3.8: mixed). The patient also developed clinical symptoms of acute cholangitis that resulted in hospitalization with peak levels of TBIL 2.5× ULN and DBIL 7.2× ULN but recovered after 1 month (Fig. 2E).

The fourth patient (case 4) was a 39‐year old White woman in whom pexidartinib was interrupted on day 15 because of elevated liver test values of ALT 8.3× ULN, AST 7.6× ULN, and ALP 1.9× ULN (R value 4.4: mixed). Two weeks later, after the liver tests were back within normal range, pexidartinib was restarted at a lower dose of 800 mg per day (day 29), with subsequent liver tests rebounding to AST 3.3× ULN, ALT 8.6× ULN, and ALP 6.2× ULN on day 50 (R value 1.4: cholestatic), and treatment was interrupted for a second time. Pexidartinib was restarted again on day 68 at 400 mg per day but was permanently discontinued 1 day later because of further liver test elevations (ALP 2.9× ULN, ALT 7.9× ULN, AST 6.7× ULN, TBIL 1.4× ULN, and GGT 6.4× ULN; R value 2.7: mixed). She recovered 1 month later (Fig. 2F).

The fifth patient (case 5) was a 43‐year‐old Asian woman who was treated with pexidartinib 800 mg per day in the PL3397‐A‐U126 study. By day 21, hepatic evaluation showed ALT 8.7× ULN, AST 8.8× ULN, ALP 5.3× ULN, and GGT 3.9× ULN (R value <2: cholestatic), resulting in pexidartinib discontinuation. Four days later (25 days after starting pexidartinib), TBIL peaked at 3× ULN and DBIL at 2.3× ULN, but the patient recovered after 2 months (Fig. 2G).

Serious Hepatic Adverse Reactions in Patients Without TGCTs

The pexidartinib clinical program also included a non‐TGCT population (N = 658) in which patients were enrolled in monotherapy or combination therapy studies as well as eight investigator‐initiated studies for the treatment of various malignancies (supplemental online Table 1). Among these patients, there were five instances (0.76%) of serious mixed or cholestatic hepatotoxicity that were judged as probably related to pexidartinib treatment by the HEAC. All five serious hepatic AR cases occurred in female patients (supplemental online Table 3).

Two of these cases were not reversible. The first irreversible case was a 66‐year‐old woman with melanoma (PLX108‐13 study; supplemental online Table 3) who started on pexidartinib 1,000 mg per day, and liver tests were monitored weekly from the start of treatment. By day 21, grade 3 elevations in aminotransferases were observed with doubling of TBIL from baseline, which was considered a dose‐limiting toxicity (R value >5: hepatocellular). Four days later, TBIL increased to 3× ULN with decreasing aminotransferase values (supplemental online Fig. 1A). She was diagnosed with drug‐induced hepatitis and remained jaundiced until her death on day 124 (R value <2: cholestatic); cause of death was listed as melanoma and cachexia.

The second irreversible case was a 60‐year‐old woman with metastatic breast cancer (I‐SPY2 study; supplemental online Table 3) who received pexidartinib 1,200 mg per day in combination with weekly paclitaxel. On day 18, aminotransferases were noted to be increasing accompanied by a fever. Although the study treatment was withheld, liver tests continued to rise (supplemental online Fig. 1B). Over the ensuing 13 months, her liver enzymes remained abnormal (ALT/AST 150 to 200 U/L; ALP 350 to 400 U/L; TBIL 20 to 25 mg/dL; R value <2: cholestatic), and she eventually required liver transplantation. Following successful transplant, her liver tests normalized and her performance status vastly improved [26].

Discussion

TKIs are well‐recognized to cause abnormal liver tests [6, 9, 14, 16, 19, 20, 21]. Understanding, monitoring, and managing possible hepatotoxicity is important to optimize systemic therapy for patients with TGCTs, particularly because, although this condition can cause significant morbidity, it is not life‐threatening, unlike malignancies. Of the 140 patients with TGCTs exposed to pexidartinib for a median treatment duration of 19 months (range, 1–76), 133 patients (95%) experienced a hepatic AR. However, in most cases hepatic toxicity was mild and manageable, and only five patients (4%) experienced serious mixed or cholestatic injury. All cases of serious liver toxicity observed presented in the first 8 weeks of treatment and all resolved. However, there is still an unpredictable risk of serious cholestatic or mixed liver injury, as shown by two irreversible cases in the non‐TGCT population.

Based on the clinical laboratory findings, pexidartinib appears to be associated with two types of hepatotoxicity. The most common form was aminotransferase elevations that were frequent, dose‐dependent, and generally low‐grade and occurred in the absence of significant TBIL and ALP elevations. We postulate that these ALT/AST elevations are a pharmacologic effect of CSF1R inhibition, possibly related to reduced clearance from the circulation and associated with a reduced number of Kupffer cells in the liver [6, 27, 28]. In support of this theory, similar aminotransferase increases have also been observed with other CSF1R inhibitors, including monoclonal antibodies [27, 28].

In contrast, mixed or cholestatic hepatotoxicity associated with pexidartinib, which can be nonreversible, is considered idiosyncratic and relatively infrequent. In some cases, as indicated by the R values, the initial injury pattern suggested hepatocellular injury but evolved into mixed and cholestatic injury, including VBDS. In the current analysis, both forms of hepatotoxicity occurred only within the first 2 months of treatment.

The approved dose regimen for pexidartinib of 800 mg per day (as 400 mg twice daily) was revised downward from the original dose regimen of 1,000 mg per day for 2 weeks followed by 800 mg per day (400 mg twice daily) used in the open‐label phase I study and the randomized phase of the ENLIVEN study. Four of the five patients with TGCTs who experienced mixed or cholestatic hepatotoxicity had a starting dose of 1,000 mg per day, although it is not known with any certainty if this was a significant factor in the development of their idiosyncratic drug‐induced liver injury (DILI), given that a 50‐ to 100‐mg dose threshold for triggering DILI has been widely accepted [29, 30, 31].

Nevertheless, the risk‐benefit consideration of starting with 800 mg per day relates to the significant reduction in the frequency of reversible, dose‐dependent aminotransferase elevations observed at this dose level. In most patients receiving pexidartinib, serum aminotransferases normalized rapidly when the drug was withheld. In patients with serum aminotransaminase elevations, in whom pexidartinib was resumed at a lower dose, no additional or only mild, clinically insignificant aminotransferase elevations were seen.

A gender imbalance was noted with respect to DILI risk in the TGCT program; four of the five patients with TGCTs and all five of the patients without TCGTs (9 of 10 total) who developed the mixed/cholestatic form of liver injury were female (Tables 3, 4; supplemental online Table 3), although the reason is not clear. Although women outnumbered men in the ENLIVEN and crossover studies as well as in the pooled TGCT data set (n = 80, 57% vs. n = 60, 43%; Table 2), this modest difference is unlikely to explain why women developed more severe DILI associated with pexidartinib compared with men. When we analyzed the isolated laboratory abnormalities/elevations (ALT, AST, ALP, TBIL, DBIL) by grade and gender across the TGCT program, women also appeared to have a higher incidence of reaching grade 3 elevations compared with men in those randomized to receive pexidartinib (Table 3).

Although it is generally known that women appear to be at higher risk based on the demographics of various DILI registries, possibly due to being prescribed a greater number of potentially hepatotoxic medications (e.g., minocycline, methyldopa, diclofenac, and nitrofurantoin drug classes) [32, 33], other factors may be at play. An analysis of the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System database found that women were at higher risk of developing adverse events from TKIs [34] and women composed 69% of the DILI cases due to antineoplastic drugs in the U.S. DILI Network registry [35], and several case series of DILI related to other TKIs appear to confirm an increased female risk as illustrated in the LiverTox Web site [36]. However, men outnumbered women in DILI cases associated with erlotinib [37], suggesting that gender differences regarding DILI risk may be drug‐specific. The risk to women receiving pexidartinib deserves further study.

All patients with TGCTs had reversible injury following discontinuation of therapy, with four of five recovering within 2 months of injury, and one patient recovering after 7 months, due to VBDS (Fig. 2A–C). It is well known that the resolution of cholestatic and mixed injury (as was seen with this case) is often prolonged over weeks to months. In patients who do not appear to recover within that time frame, chronic cholestatic injury is a possible consequence. VBDS is a rare form of chronic cholestasis with no specific or proven treatment, and it has eventually resulted in the need for liver transplant, as was the case with the one patient without TGCTs [26]. However, VBDS is not specific to pexidartinib, having been associated with a long list of agents from numerous drug classes [38, 39, 40].

Recommended Dose Modifications and the Pexidartinib Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy Program

Careful monitoring of liver enzymes following the start of pexidartinib treatment is critical, and the intensity of monitoring depends upon the occurrence of hepatic ARs. Across the pooled studies, the most frequent elevations in hepatic laboratory values requiring dose modifications were ALT or AST increases to >3 to 5× ULN and TBIL ≥2× ULN, or DBIL >1.5× ULN, followed by ALT or AST increases to >5 to 10× ULN and ALP >2× ULN (supplemental online Table 4). With the approval of pexidartinib as the first systemic therapy for the treatment of adult patients with symptomatic TGCT/PVNS associated with severe morbidity or functional limitations and not amenable to improvement with surgery [17, 18] came the need for liver test monitoring and other measures stipulated in the Pexidartinib Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) for the drug in the U.S. (supplemental online Table 5) [17]. Because of the unpredictable risk of the more serious mixed or cholestatic hepatic injury (including the VBDS) seen in the clinical trials [6, 14], monitoring of liver tests is recommended every week for the first 2 months and then biweekly for the third month, which is believed to cover the period of maximal risk (i.e., the first 8 weeks). Based on the label, dose modifications for pexidartinib (including early withholding treatment for liver test monitoring, dose reduction in 200‐mg increments, and/or permanent discontinuation) have been established (supplemental online Table 5) [17].

It was observed that reducing the pexidartinib dose allowed some patients who developed transiently elevated ALT to resume therapy without developing a second rise in ALT values. The approved pexidartinib starting dose is 800 mg per day for men and women (which is lower than the 1,000‐mg starting dose given in part 1 of the ENLIVEN study). In conjunction with the frequent liver test monitoring that is required and adhering to the conservative stopping rules (supplemental online Table 5) [17], it is anticipated that any potential hepatotoxicity will be identified early and immediate treatment interruption will reduce the risk of progressing further for both men and women.

We recognize the limitations of this pooled analysis, including the lack of a control group for comparison of the hepatic safety profile following long‐term pexidartinib treatment. In addition, the different study designs among the four patient cohorts included varying administered daily doses of pexidartinib ranging from 600 to 1,000 mg per day. Nonetheless, the long‐term hepatic safety profile of pexidartinib as demonstrated in this pooled analysis provides guidance for its proper use for appropriate patients within risk mitigation programs such as the Pexidartinib REMS program.

Conclusion

Long‐term treatment with pexidartinib has demonstrated both a predictable and an unpredictable effect on hepatic enzymes. This knowledge can help form the basis for the prescribing physician's risk/benefit assessment for their patients with TGCTs. Results from our analysis support the current risk mitigation strategies, adherence to which can lead to optimized patient outcomes, foremost of which is safety.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Silvia Stacchiotti, William D. Tap, Dale E. Shuster.

Collection/assembly of data: Hans Gelderblom, William D. Tap, Andrew J. Wagner, Antonio Lopez Pousa, Chia‐Chi Lin, Hideo A. Baba, Youngsook Choi, Dale E. Shuster.

Data analysis/interpretation: James H. Lewis, Hans Gelderblom, Michiel van de Sande, Silvia Stacchiotti, John H. Healey, William D. Tap, Andrew J. Wagner, Antonio Lopez Pousa, Mihaela Druta, Youngsook Choi, Qiang Wang, Dale E. Shuster, Sebastian Bauer.

Manuscript writing: James H. Lewis, Hans Gelderblom, Michiel van de Sande, Silvia Stacchiotti, John H. Healey, William D. Tap, Andrew J. Wagner, Antonio Lopez Pousa, Mihaela Druta, Chia‐Chi Lin, Hideo A. Baba, Youngsook Choi, Qiang Wang, Dale E. Shuster, Sebastian Bauer.

Final approval of manuscript: James H. Lewis, Hans Gelderblom, Michiel van de Sande, Silvia Stacchiotti, John H. Healey, William D. Tap, Andrew J. Wagner, Antonio Lopez Pousa, Mihaela Druta, Chia‐Chi Lin, Hideo A. Baba, Youngsook Choi, Qiang Wang, Dale E. Shuster, Sebastian Bauer.

Disclosures

James H. Lewis: Daiichi Sankyo, Otsuka, Reata, Allergan, B‐I, Pfizer, Zydus, Chimerix, Akebia, CiVi, Sanofi, Intercept, Madrigal, Palladio, Biohaven, Orphazyme (C/A), AbbVie, GlaxoSmithKline, Gilead, Pfizer (OI), Gilead (Other‐speaker's bureau); Hans Gelderblom: Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Five Prime Therapeutics, Novartis, Pfizer, PharmaMar (RF‐institutional); Michiel van de Sande: Daiichi Sankyo (C/A), CarboFix, Daiichi Sankyo, and Implantcast (RF‐institutional); Silvia Stacchiotti: Bavarian Nordic, Bayer, Deciphera, Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly & Co, Epizyme, Glaxo, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Maxivax, Novartis, and PharmaMar (C/A), Advenchen, Bayer, Blueprint Medicines, Deciphera, Eli Lilly & Co, Epizyme, Daiichi Sankyo, Glaxo, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Novartis, PharmaMar, and Springworks (RF‐institutional), Eli Lilly & Co, PharmaMar, and Takeda (H), PharmaMar (Other travel support); John H. Healey: Daiichi Sankyo (C/A); William D. Tap: Agios Pharmaceuticals, Blueprint Medicines, Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, Eli Lilly & Co, EMD Serono, GlaxoSmithKline, Immune Design, Janssen, Loxo Oncology (C/A), Atropos Therapeutics, Certis Oncology Solutions (OI), Companion Diagnostic for CDK4 inhibitors ‐ 14/854,329 pending to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center/Sloan Kettering Institute (IP), Agios Pharmaceuticals, Atropos Therapeutics, Blueprint Medicines, Certis Oncology Solutions, Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, Eli Lilly & Co, EMD Serono, GlaxoSmithKline, Immune Design, Janssen, Loxo Oncology, NanoCarrier, and Deciphera (SAB), Eisai, Eli Lilly & Co, EMD Serono, Immune Design, Janssen (Other‐travel support); Andrew J. Wagner: Daiichi‐Sankyo, Deciphera, Eli Lilly & Co, Five Prime Therapeutics, NanoCarrier, Novartis (C/A), Aadi Bioscience, Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly & Co, Five Prime Therapeutics, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Plexxikon (RF‐institutional), Novartis (H); Mihaela Druta: Adaptimmune, Blueprint, Daiichi Sankyo, Deciphera, Epizyme (C/A), Adaptimmune, Blueprint, Daiichi Sankyo, Deciphera, Epizyme (H), Blueprint, Deciphera (Other‐speaker's bureau), Adaptimmune, Daiichi Sankyo, and Epizyme (Other‐travel support); Chia‐Chi Lin: Blueprint Medicines, Boehringer‐Ingelheim, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, and Novartis (C/A), Eli Lilly & Co, Novartis, Roche (H), BeiGene, Eli Lilly & Co(Other‐travel support); Hideo A. Baba: Alexion and Intercept (H), Intercept (OI), Alexion (Other‐travel support); Youngsook Choi: Daiichi Sankyo (E), Daiichi Sankyo (OI); Qiang Wang: Daiichi Sankyo (E), Daiichi Sankyo (OI); Dale E. Shuster: Daiichi Sankyo (E); Amgen, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Exelixis, Merck, Regeneron (OI); Sebastian Bauer: Blueprint Medicines, Incyte, and Novartis (RF‐institutional), PharmaMar, Eli Lilly & Co, Novartis (H), ADC Therapeutics, Bayer, Blueprint Medicines, Daiichi Sankyo, Deciphera, Eli Lilly & Co, Exelixis, Nanobiotix, Novartis, Roche (SAB), PharmaMar (Other‐travel support). The other author indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

Supporting information

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Figure S1 Clinical laboratory reports of non‐TGCT irreversible serious hepatic adverse reaction cases. A.Case #1; B. Case #2

Supplementary Table 1. Summary of non‐TGCT studies of pexidartinib

Supplemental online Table 2. Hepatic laboratory abnormalities (≥10% All Grades 1, 2, ≥3) in patients receiving pexidartinib

Supplemental online Table 3. Serious Hepatic Adverse Reactions in Non‐TGCT Patients

Supplemental online Table 4. Liver test abnormalities meeting criteria for pexidartinib dose modifications

Supplemental online Table 5. Recommended dosage modifications for pexidartinib dependent on adverse reaction [17]

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients who participated in this analysis, their family members and caregivers, the study staff members at each site who cared for the patients, the sponsor staff involved in data collection and analyses, and Phillip Giannopoulos, Ph.D. (SciStrategy Communications) for medical writing assistance in the development of the manuscript. Research and manuscript support were provided by Daiichi Sankyo, Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan. All research funding for Memorial Sloan Kettering is supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (no. P30 CA008748).

Sponsored by Daiichi Sankyo, Co., Ltd; ClinicalTrials.gov numbers: NCT01004861, NCT02371369, NCT02734433, and NCT03291288.

Deidentified individual participant data and applicable supporting clinical study documents may be available upon request at https://www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com//. In cases where clinical study data and supporting documents are provided pursuant to the sponsor's policies and procedures, the sponsor will continue to protect the privacy of the clinical study participants. Details on data sharing criteria and the procedure for requesting access can be found at this web address: https://www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com/Study‐Sponsors/Study‐Sponsors‐DS.aspx.

Presented previously in part at American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting, May 31–June 4, 2019, Chicago, IL; and European Society for Medical Oncology Congress, September 27–October 1, 2019, Barcelona, Spain.

Disclosures of potential conflicts of interest may be found at the end of this article.

References

- 1. Mastboom MJL, Palmerini E, Verspoor FGM et al. Surgical outcomes of patients with diffuse‐type tenosynovial giant‐cell tumours: An international, retrospective, cohort study. Lancet Oncol 2019;20:877–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. de Saint Aubain Somerhausen N, van de Rijn M. Tenosynovial giant cell tumor: localized type, diffuse type. In: Fletcher C, Bridge J, Hogendoorn P, Martens F, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. 4th ed. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2013:100–103. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Staals EL, Ferrari S, Donati DM et al. Diffuse‐type tenosynovial giant cell tumour: Current treatment concepts and future perspectives. Eur J Cancer 2016;63:34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mastboom MJL, Verspoor FGM, Gelderblom H et al. Limb amputation after multiple treatments of tenosynovial giant cell tumour: Series of 4 Dutch cases. Case Rep Orthop 2017;2017:7402570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tap WD. Multidisciplinary care in tenosynovial giant cell tumours. Lancet Oncol 2019;20:755–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tap WD, Wainberg ZA, Anthony SP et al. Structure‐guided blockade of CSF1R kinase in tenosynovial giant‐cell tumor. N Engl J Med 2015;373:428–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brahmi M, Vinceneux A, Cassier PA. Current systemic treatment options for tenosynovial giant cell tumor/pigmented villonodular synovitis: Targeting the CSF1/CSF1R axis. Curr Treat Options Oncol 2016;17:10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cassier PA, Italiano A, Gomez‐Roca CA et al. CSF1R inhibition with emactuzumab in locally advanced diffuse‐type tenosynovial giant cell tumours of the soft tissue: A dose‐escalation and dose‐expansion phase 1 study. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:949–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gelderblom H, Cropet C, Chevreau C et al. Nilotinib in locally advanced pigmented villonodular synovitis: A multicentre, open‐label, single‐arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:639–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nakayama R, Jagannathan JP, Ramaiya N et al. Clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes in six cases of malignant tenosynovial giant cell tumor: Initial experience of molecularly targeted therapy. BMC Cancer 2018;18:1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Palmerini E, Staals EL, Maki RG et al. Tenosynovial giant cell tumour/pigmented villonodular synovitis: Outcome of 294 patients before the era of kinase inhibitors. Eur J Cancer 2015;51:210–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ravi V, Wang WL, Lewis VO. Treatment of tenosynovial giant cell tumor and pigmented villonodular synovitis. Curr Opin Oncol 2011;23:361–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rebuzzi SE, Grassi M, Catalano F et al. Multiple systemic treatment options in a patient with malignant tenosynovial giant cell tumour. Anticancer Drugs 2020;31:80–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tap WD, Gelderblom H, Palmerini E et al. Pexidartinib versus placebo for advanced tenosynovial giant cell tumour (ENLIVEN): A randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet 2019;394:478‐487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Temple HT. Pigmented villonodular synovitis therapy with MSCF‐1 inhibitors. Curr Opin Oncol 2012;24:404–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Verspoor FGM, Mastboom MJL, Hannink G et al. Long‐term efficacy of imatinib mesylate in patients with advanced tenosynovial giant cell tumor. Sci Rep 2019;9:14551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Turalio (pexidartinib) capsules, for oral use . Prescribing information. Daiichi Sankyo, Inc.; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 18. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Soft tissue sarcoma—version 5.2019. Plymouth Meeting, PA: National Comprehensive Cancer Network; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shah RR, Morganroth J, Shah DR. Hepatotoxicity of tyrosine kinase inhibitors: Clinical and regulatory perspectives. Drug Saf 2013;36:491–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Teo YL, Ho HK, Chan A. Risk of tyrosine kinase inhibitors‐induced hepatotoxicity in cancer patients: A meta‐analysis. Cancer Treat Rev 2013;39:199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Teo YL, Ho HK, Chan A. Formation of reactive metabolites and management of tyrosine kinase inhibitor‐induced hepatotoxicity: A literature review. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 2015;11:231–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lee JH, Chen TW, Hsu CH et al. A phase I study of pexidartinib, a colony‐stimulating factor 1 receptor inhibitor, in Asian patients with advanced solid tumors. Invest New Drugs 2020;38:99–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Briefing Document. Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee Meeting May 14 , 2019: NDA 211810: Pexidartinib. Washington, DC: U.S. Food and Drug Administration; 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Regev A, Björnsson ES. Drug‐induced liver injury: Morbidity, mortality, and Hy's law. Gastroenterology 2014;147:20–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Danan G, Benichou C. Causality assessment of adverse reactions to drugs–I. A novel method based on the conclusions of international consensus meetings: Application to drug‐induced liver injuries. J Clin Epidemiol 1993;46:1323–1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Piawah S, Hyland C, Umetsu SE et al. A case report of vanishing bile duct syndrome after exposure to pexidartinib (PLX3397) and paclitaxel. NPJ Breast Cancer 2019;5:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Genovese MC, Hsia E, Belkowski SM et al. Results from a phase IIA parallel group study of JNJ‐40346527, an oral CSF‐1R inhibitor, in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis despite disease‐modifying antirheumatic drug therapy. J Rheumatol 2015;42:1752–1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pognan F, Couttet P, Demin I et al. Colony‐stimulating factor‐1 antibody lacnotuzumab in a phase 1 healthy volunteer study and mechanistic investigation of safety outcomes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2019;369:428–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chen M, Borlak J, Tong W. High lipophilicity and high daily dose of oral medications are associated with significant risk for drug‐induced liver injury. Hepatology 2013;58:388–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lammert C, Einarsson S, Saha C et al. Relationship between daily dose of oral medications and idiosyncratic drug‐induced liver injury: Search for signals. Hepatology 2008;47:2003–2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lewis JH. Drug‐induced liver injury, dosage, and drug disposition: Is idiosyncrasy really unpredictable? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;12:1556–1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chalasani NP, Hayashi PH, Bonkovsky HL et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: The diagnosis and management of idiosyncratic drug‐induced liver injury. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:950‐966; quiz 967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lewis JH. The art and science of diagnosing and managing drug‐induced liver injury in 2015 and beyond. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:2173–2189.e2178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Huang J, Meng L, Yang B et al. Safety profile of epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors: A disproportionality analysis of FDA adverse event reporting system. Sci Rep 2020;10:4803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chalasani NP, Bonkovsky HL, Fontana RJ et al. Features and outcomes of 899 patients with drug‐induced liver injury: The DILIN prospective study. Gastroenterology 2015;148:1340–1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. LiverTox : Clinical and research information on drug‐induced liver injury. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kim MN, Yee J, Cho YS et al. Risk factors for erlotinib‐induced hepatotoxicity: A retrospective follow‐up study. BMC Cancer 2018;18:988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Desmet VJ. Vanishing bile duct disorders. Prog Liver Dis 1992;10:89–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Desmet VJ, van Eyken P, Roskams T. Histopathology of vanishing bile duct diseases. Adv Clin Path 1998;2:87–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Visentin M, Lenggenhager D, Gai Z et al. Drug‐induced bile duct injury. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2018;1864:1498–1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Figure S1 Clinical laboratory reports of non‐TGCT irreversible serious hepatic adverse reaction cases. A.Case #1; B. Case #2

Supplementary Table 1. Summary of non‐TGCT studies of pexidartinib

Supplemental online Table 2. Hepatic laboratory abnormalities (≥10% All Grades 1, 2, ≥3) in patients receiving pexidartinib

Supplemental online Table 3. Serious Hepatic Adverse Reactions in Non‐TGCT Patients

Supplemental online Table 4. Liver test abnormalities meeting criteria for pexidartinib dose modifications

Supplemental online Table 5. Recommended dosage modifications for pexidartinib dependent on adverse reaction [17]