Summary

Medieval Europe was repeatedly affected by outbreaks of infectious diseases, some of which reached epidemic proportions. A Late Medieval mass burial next to the Heiligen-Geist-Hospital in Lübeck (present-day Germany) contained the skeletal remains of more than 800 individuals who had presumably died from infectious disease. From 92 individuals, we screened the ancient DNA extracts for the presence of pathogens to determine the cause of death. Metagenomic analysis revealed evidence of Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi C, suggesting an outbreak of enteric paratyphoid fever. Three reconstructed S. Paratyphi C genomes showed close similarity to a strain from Norway (1200 CE). Radiocarbon dates placed the disease outbreak in Lübeck between 1270 and 1400 cal CE, with historical records indicating 1367 CE as the most probable year. The deceased were of northern and eastern European descent, confirming Lübeck as an important trading center of the Hanseatic League in the Baltic region.

Subject areas: Paleontology, Microbiology

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Salmonella enterica Paratyphi C detected in remains from a mass burial in Lübeck

-

•

Outbreak of enteric paratyphoid fever likely occurred in 1367 CE

-

•

Pathogen genomes showed close similarity to a strain from Norway (1200 CE)

Paleontology; Microbiology

Introduction

In the High and Late Middle Ages, European settlements of all sizes were repeatedly struck by outbreaks of infectious diseases. Some of them reached epidemic proportions such as smallpox (Duggan et al., 2016), leprosy (Krause-Kyora et al., 2018a; Schuenemann et al., 2013, 2018), or the second plague pandemic that started with the Black Death (Bos et al., 2011; Haensch et al., 2010; Spyrou et al., 2016, 2019). Medieval chronicles generally referred to epidemics as “pestis” or “pestilentiae”, regardless of the causative pathogen responsible (Kahlow 2007). Increasing trade and mobility played an important role in spreading pathogens along cross-country and maritime routes throughout the continent (Yue et al., 2017). One of the most important medieval commercial networks was the Hanseatic League, which dominated the northern European and Baltic maritime trade from the 13th to the 16th century (Dollinger and Krabusch, 1998). At its center was the city of Lübeck in present-day Germany, a wealthy and influential trading hub on the Baltic Sea (Benedictow, 2017; Singman, 1999) (Figure 1A). In 1226 CE, the Heiligen-Geist-Hospital (“Hospital of the Holy Ghost”, HGH) was established there, which was dedicated to the care and welfare of the elderly (Lütgert, 2002). The large building complex still exists today and is currently in use as a retirement home as well as a museum. In 1989, construction works on the southern walls of the hospital revealed a mass burial site nearby (Figure 1B), containing the remains of more than 800 individuals from the Late Middle Ages (Lütgert, 2002; Prechel, 1996, 2002) (Figures 1C and 1D). Based on archaeological evidence and the lack of traumatic lesions on the bones, the dead were assumed to represent victims of an epidemic event, most likely of the Black Death, as the plague was reported to have affected Lübeck successively, first in 1350 CE (Koppmann, 1899) and later again in 1359 CE (Koppmann, 1884). However, these outbreaks were followed by at least four more pestilences of unclear etiology in the 14th century (Koppmann, 1884).

Figure 1.

The excavation site of the Heiligen-Geist-Hospital (HGH) in Lübeck

(A) Location of Lübeck in present-day northern Germany.

(B–D) (B) Plan of the HGH building complex. The mass graves 4528 and 4529 and the two multiple burial pits 4562 and 4571 are indicated. All S. Paratyphi C-positives were found in the pits 4562 (C) and 4571 (D).

In order to identify the infectious agent that led to the death of the individuals buried next to the HGH in Lübeck, we screened the skeletal remains of 92 individuals from this site for the presence of pathogens. We found evidence of an infection with the bacterium Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi C (S. Paratyphi C) in eight individuals, suggesting an outbreak of enteric paratyphoid fever that afflicted the city of Lübeck in the late 14th century.

Results

In this study, we analyzed 92 individuals excavated from the HGH mass burial site in Lübeck. The remains were obtained from four archaeological contexts, i.e., from two mass graves (4528, n = 29 and 4529, n = 11) and two smaller pits (4562, n = 13 and 4571, n = 39; Figures 1C and 1D). We performed radiocarbon dating which placed all four contexts in the same time range from 1270 to 1400 cal CE (Table S1 and Figure S1). However, based on a coin found in situ (4528), the period of use of the mass graves could be narrowed down to 1340–1370 CE. The two smaller pits stratigraphically cut into the mass grave contexts and are therefore considered younger (Prechel, 2002).

We extracted ancient DNA (aDNA) from teeth and/or bones of all 92 individuals following established guidelines for the work with tiny amounts of fragmented DNA (Cooper and Poinar, 2000). All procedures were conducted in dedicated aDNA clean rooms. Blank controls that were included in each experimental step were always negative. Short tandem repeat profiles at seven loci were generated as an additional authentication criterion and to avoid double sampling (Table S2).

Metagenomic screening

First, all metagenomic aDNA extracts were screened for bacterial and viral pathogens using an established in-house pipeline (Krause-Kyora et al., 2018a, 2018b; Susat et al., 2020). Ten data sets were observed to align to the taxonomic node of S. enterica subsp. enterica, based on a threshold of at least 300 reads per sample aligning to S. enterica from an initial sequencing depth of 2–54 million reads per sample (Table S3). The sequencing reads were then competitively mapped to a multi-sequence reference comprising the complete genomes of 15 different serovars that represent the modern diversity of S. enterica (Table S4). In eight of the ten data sets, S. Paratyphi C was the reference with the highest number of aligned reads. For two samples (HGH-1458, HGH-1699), the aligned reads were subsequently identified as false positives. The S. Paratyphi C classifications in the other eight samples were confirmed through a taxa-specific mapping score (see methods; Table S3) that was developed analogously to the mapping score described in a study of Yersinia pestis (Y. pestis) (Andrades Valtueña et al., 2017). Additionally, we used the tool MaltExtract (Hübler et al., 2019) to verify the findings (Table S3). Based on these criteria, we identified eight positive samples (HGH-1429, HGH-1510, HGH-1558, HGH-1579, HGH-1599, HGH-1600, HGH-1607, HGH-1638; Table 1) for which additional 185 to 642 million reads were generated to facilitate genome reconstruction. The obtained sequencing reads were then aligned to the reference genome of S. Paratyphi C RKS4594 (NC_012125), and consensus sequences with a 2-fold genome-wide coverage of up to 96% were constructed (Table 1). All samples displayed typical damage patterns for both ancient bacterial and human DNA (Figures S2 and S3).

Table 1.

Sequencing and mapping statistics of the eight S. Paratyphi C-positive samples from the HGH in Lübeck

| Sample | Context | Pre-processed reads prior to mapping (n) | Unique reads mapped to S. Paratyphi C (n) | Quality filtered endogenous DNA (%) | Mean coverage | Percentage of genome covered at least 1-fold | Percentage of genome covered at least 2-fold |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HGH-1429 | 4571 | 544,611,092 | 291,107 | 0.42 | 4.05 | 85.8 | 75.06 |

| HGH-1510 | 4571 | 15,763,343 | 473 | 0.003 | 0.0057 | 0.56 | 0.01 |

| HGH-1558 | 4571 | 641,527,718 | 229,593 | 0.293 | 2.99 | 82.11 | 64.07 |

| HGH-1579 | 4562 | 533,324,715 | 41,228 | 0.04 | 0.79 | 50.2 | 19.51 |

| HGH-1599 | 4571 | 6,435,352 | 459 | 0.008 | 0.0065 | 0.65 | 0.01 |

| HGH-1600 | 4571 | 530,411,412 | 562,392 | 0.173 | 6.73 | 96.96 | 95.62 |

| HGH-1607 | 4562 | 184,903,636 | 13,219 | 0.035 | 0.12 | 10.65 | 1.03 |

| HGH-1638 | 4571 | 548,078,315 | 18,361 | 0.015 | 0.19 | 16.26 | 2.11 |

Data sets were mapped to the reference genome of S. Paratyphi C RKS4594 (NC_012125).

It is noteworthy that the S. Paratyphi C-positive results were only observed in human remains from the multiple burial pits 4562 (n = 2) and 4571 (n = 6) but not in skeletons from the mass graves 4528 and 4529 (Table S3). In previous publications, the plague was assumed to have caused the death of the individuals buried next to the HGH (Prechel, 1996, 2002). However, in our metagenomic screening of the 92 aDNA extracts, there was no evidence of Y. pestis reads.

Phylogenetic reconstruction

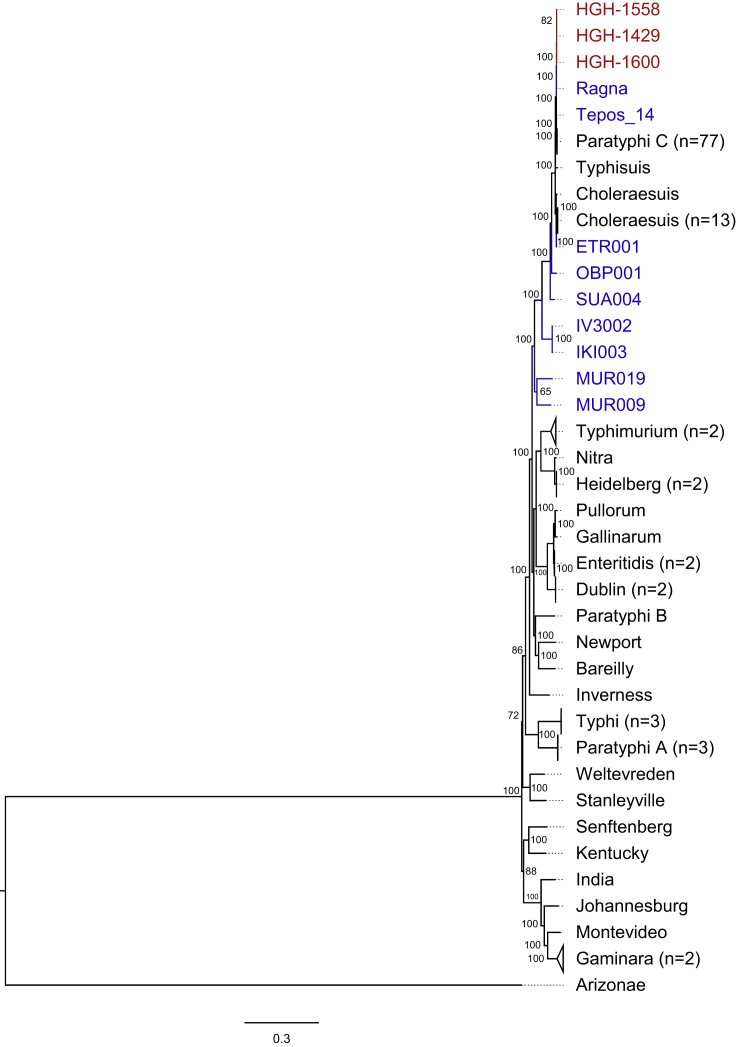

Next, we computed a Bayesian phylogenetic tree based on a multi-variant alignment, including three genomes with high coverage from this study (HGH-1429, HGH-1558, HGH-1600; Table 1) as well as nine ancient (Key et al., 2020; Vågene et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2018) and 123 modern S. enterica subsp. enterica genomes (Alikhan et al., 2018; O'Leary et al., 2016; Zhou et al., 2020). The consensus sequences of the remaining five samples from Lübeck were not considered for phylogenetic reconstruction due to low coverage (a 1-fold coverage below 51%; Table 1). All ancient and modern S. Paratyphi C strains formed a single clade in the tree, supported by a posterior probability of 1 (Figure 2). The three genomes from Lübeck clustered together. They differed from each other only in up to four single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs); this variation probably reflects the micro-diversity within an outbreak (Table S5). The SNP effect analysis showed that none of the four variants had an influence on virulence or function. Furthermore, the three HGH genomes were similar to two previously published ancient S. Paratyphi C genomes, those from Ragna (Norway 1200 CE) (Zhou et al., 2018) and Tepos (Mexico 1545 CE) (Vågene et al., 2018) (Figure S4).

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic relationship of ancient and modern Salmonella enterica genomes

Bayesian phylogenetic tree of three genomes from the HGH mass burial site in Lübeck (red), nine ancient (blue), and 123 modern (black) S. enterica genomes. S. enterica subsp. arizonae RKS2983 is used as out-group. Branches of the same serovars are collapsed, and the number of combined reference genomes is given in brackets. Nodes are labeled with posterior probabilities estimated by MrBayes. Branch lengths correspond to the number of substitutions per site. An enlarged section of the three HGH Lübeck genomes as well as those from Ragna and Tepos is provided in Figure S4.

Population genetic analyses

In a second approach, we analyzed the 92 metagenomic sequences with respect to the presence of human DNA. Fifty-three data sets were of sufficient quality for population genetic analyses (Table S3). In a principal component analysis, the individuals from medieval Lübeck grouped together and showed genetic similarities to modern populations from Scandinavia and the Baltic region, including northern Germany (Figures 3 and S5). Further, f3 statistics revealed affinities between Lübeck and populations from northern and eastern Europe (Figure S6). Mitochondrial (mt) haplogroups could be determined in 52 individuals. The mtDNA distribution in Lübeck was similar to that observed in other central and northern European populations, with haplogroups H and U being the most abundant (Table S3).

Figure 3.

Population genetic analysis

Principal component analysis (PCA) of HGH individuals (red circles) from Lübeck in the context of 19 modern-day European populations. A PCA with a larger set of reference populations is shown in Figure S5.

Discussion

The Late Medieval mass burial site next to the HGH in Lübeck comprised the skeletons of more than 800 individuals that had been interred in two mass graves and two smaller burial pits, probably in the course of different disease outbreaks. Our pathogen screening revealed Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi C in skeletal remains from the two burial pits, indicating the highly contagious enteric paratyphoid fever as the cause of death. However, we could not detect any traces of S. enterica or Y. pestis in the two mass graves.

Our radiocarbon dates (1270–1400 cal CE; Table S1) and the coin (1340–1370 CE) place all four contexts in the second half of the 14th century. Several consecutive epidemics were recorded to have affected the city of Lübeck in this period. The first in 1350 CE and the second in 1359 CE are usually attributed to the Black Death that was responsible for a very high death toll in all cities on the coast of northern Germany (Koppmann, 1884). The large number of corpses in the mass graves suggests that they were the victims of one or both plague waves (Prechel, 1996, 2002), though we did not find genetic traces of Y. pestis.

As the two pits were stratigraphically younger than the mass graves (Lütgert, 2002; Prechel, 2002), we hypothesize that the 120 deceased in the two pits had succumbed to one of the later dated pestilences, i.e., between 1360 and 1400 CE. The archaeological context indicates that the pits were refilled quickly, which suggests that all the individuals had died from the same disease, paratyphoid fever, within a short time. This scenario is supported by our detection rate (8 S. Paratyphi C-positives in 52 remains from the two pits) that is remarkably high for ancient pathogen diagnostics.

The city chronicles mentioned a third epidemic of unknown cause in 1367 CE, which was limited to Lübeck only (Koppmann, 1899; Ibs, 1994). The clinical manifestation of paratyphoid fever would be consistent with such a localized event. Lübeck was a clean city by the standards of the time and had invested in eliminating health hazards, for example, by introducing separate sewage and drinking water systems (Grabowski and Schmitt, 1993; Lüdecke, 1980). An outbreak of paratyphoid fever therefore seems somewhat surprising. But S. Paratyphi C bacteria, which grow in the intestines and blood, are easily spread via water or food contaminated with the feces of an infected individual. In many cases, transmission occurs when active or asymptomatic carriers (super-spreaders) do not wash their hands before preparing or handling food (Bhan et al., 2005, Crump and Mintz, 2010; Sánchez-Vargas et al., 2011). Because the dead were buried next to the HGH, these premises appear to be a possible hotspot of infection. However, the HGH was not a hospital in the modern sense of the word, but rather a social institution managed by the city council providing housing, food, and care for the more affluent elderly who bought the prerogative to reside in the HGH. It thus resembled more a present-day retirement or nursing home. About 51% of the skeletons in the two smaller burial pits represented individuals younger than 40 years (Prechel, 1996) who were unlikely to have lived in an old age home. Besides, the HGH maintained its own regular graveyard in the vicinity. It can therefore be assumed that the majority of the dead in the pits, especially the younger ones, were not residents of the HGH. A paratyphoid fever outbreak that claimed 120 lives from all age groups (Prechel, 1996) must have affected many households. Due to the lack of written or archaeological evidence, we do not know from where the paratyphoid fever emanated or how it spread. But as Lübeck was densely populated and there was no gentrification of residential districts (Hammel-Kiesow, 2006), the outbreak probably affected people of all social strata, including wealthier citizens. This scenario is in agreement with the city chronicles which mentioned that a large proportion of the affluent population was killed in the outbreak of 1367 CE (Koppmann, 1884). However, the latter had their own cemeteries outside the city (Koppmann, 1899), so it was unlikely that they would be interred in a mass burial. In contrast, as evidenced by the different mass graves at the HGH, its unconsecrated grounds were apparently repeatedly used for the disposal of corpses which accumulated rapidly during epidemics and must primarily have come from people who were not wealthy enough for a proper burial in the established cemeteries. In any case, the results of our population genetic analyses showed that the dead represented a varied group of people of northern and eastern European descent. This finding is compatible with the role of Lübeck as an important trading center of the Hanseatic League. The city is often referred to as “The Queen of the Hansa”, attracting merchants, sailors, and workers from all over the Baltic region. Due to the Hanseatic trade and the institutionalized trading stations of the Hanseatic Merchant in Bergen (Norway) and Novgorod (Russia), Lübeck was a melting pot of very diverse people (Dollinger and Krabusch, 1998; Graβmann, 2005).

S. Paratyphi C is one of the several invasive typhoidal Salmonella enterica serovars that cause enteric fever in humans, including S. Typhi (typhoid fever) and S. Paratyphi A, B, and C (paratyphoid fever). Still today, paratyphoid fever affects about five million people a year worldwide, resulting in 54,000 deaths (Crump and Mintz, 2010; World Health Organization, 2018). However, cases of S. Paratyphi C infection are not frequently reported, and the pathogen is no longer endemic in Europe (Achtman et al., 2012; Crump and Mintz, 2010; Liu et al., 2009; Uzzau et al., 2000). In contrast, S. Paratyphi C has been the only Salmonella enterica serovar found so far in specimens from medieval Europe (Zhou et al., 2018) and 16th-century Central America (a strain imported from Europe) (Vågene et al., 2018). Thus, S. Paratyphi C might have been the predominant typhoidal agent at the time.

Our phylogenetic reconstruction showed strong genomic stability of the S. Paratyphi C subgroup over at least one millennium. This is reflected in a small number of variants between the globally distributed ancient and modern genomes within the Paratyphi C clade, with the oldest genome dating to 1200 CE (Zhou et al., 2018) and the most recent to 2015 (Alikhan et al., 2018). Similarly, the three reconstructed genomes from Lübeck differed in only a few SNPs that were identified to have no effect on the phenotype (Table S5).

This aDNA study reports an epidemic outbreak of paratyphoid fever in Lübeck in the 14th century that killed at least 120 people. The infection dynamics were probably less pronounced and more localized than those of the previous plague. Nonetheless, the effects on life and trade must have been clearly felt. The consequences of the recurring disease outbreaks in the second half of the 14th century were severe and long lasting for Lübeck and the surrounding area, leading to collapsing bond and real estate markets, as well as increasing bankruptcy of local businesses. Moreover, the prospect of imminent death drove many citizens to make generous donations to churches and monasteries out of concern for the salvation of their souls (Fouquet and Zeilinger, 2011).

Limitations of the study

The main challenges in aDNA research are the small number of samples usually available for analysis and the poor DNA preservation. Due to a variety of environmental (Bollongino et al., 2008; Collins et al., 2002) and chemical (Warinner et al., 2017) factors, endogenous (human and pathogen) DNA is degraded over time, rendering the recovery and analysis of any remaining DNA fragments often very difficult, if not impossible. In our study, we examined the skeletal remains of 92 individuals, a relatively large sample by aDNA standards. However, only 53 of them (∼57.6%) contained sufficient human DNA for population genetic analyses. S. Paratyphi C DNA was even less abundant than human DNA in the extracts (Tables 1 and S3). In total, we identified S. Paratyphi C reads in eight individuals, and three of the generated data sets allowed for a full genome reconstruction. So far, only two other ancient S. Paratyphi C strains (Norway 1200 CE, Mexico 1545 CE) have been reported. Additional genomes from other historical periods and regions are therefore needed to provide a more comprehensive phylogeography of the pathogen.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information, requests, and inquiries should be directed to the lead contact, Ben Krause-Kyora (b.krause-kyora@ikmb.uni-kiel.de).

Materials availability

The study did not generate new unique reagents or materials.

Data and code availability

The accession number for the data reported in this paper is available through the European Nucleotide Archive: PRJEB41353 (https://www.ebi.ac.uk).

Methods

All methods can be found in the accompanying Transparent methods supplemental file.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, Germany (DFG, German Research Foundation) through the projects 2901391021 (CRC 1266) and 390870439 (EXC 2150 – ROOTS) and the Medical Faculty of Kiel University, Germany. We thank Tal Dagan, Institute of General Microbiology, Kiel University, for her advice and helpful discussions.

Author contributions

A.N., S.H., and B.K.-K. conceived and designed the study. M.H., K.C., J.S., A.L.F., A.I., A.F., A.H., and A.K. generated and analyzed aDNA data. M.H., J.K., G.F., D.R., A.N., and B.K.-K. interpreted the results. M.H., A.N., B.K.-K. wrote and revised the manuscript with input from all the other authors.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Inclusion and diversity

We worked to ensure diversity in experimental samples through the selection of the genomic data sets. The author list of this paper includes contributors from the location where the research was conducted who participated in the data collection, design, analysis, and/or interpretation of the work.

Published: May 21, 2021

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2021.102419.

Supplemental information

References

- Achtman M., Wain J., Weill F.X., Nair S., Zhou Z., Sangal V. Multilocus sequence typing as a replacement for serotyping in Salmonella enterica. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002776. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alikhan N.-F., Zhou Z., Sergeant M.J., Achtman M. A genomic overview of the population structure of Salmonella. PLoS Genet. 2018;14:e1007261. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrades Valtueña A., Mittnik A., Key F.M., Haak W., Allmäe R., Belinskij A. The stone age plague and its persistence in Eurasia. Curr. Biol. 2017;27:3683–3691.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedictow O.J. Boydell Press; 2017. The Black Death, 1346–1353: The Complete History. [Google Scholar]

- Bhan M.K., Bahl R., Bhatnagar S. Typhoid and paratyphoid fever. Lancet. 2005;366:749–762. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67181-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollongino R., Tresset A., Vigne J.-D. Environment and excavation. Pre-lab impacts on ancient DNA analyses. Comptes. Rendus. Palevol. 2008;7:91–98. [Google Scholar]

- Bos K.I., Schuenemann V.J., Golding G.B., Burbano H.A., Waglechner N., Coombes B.K., McPhee J.B., DeWitte S.N., Meyer M., Schmedes S. A draft genome of Yersinia pestis from victims of the Black Death. Nature. 2011;478:506–510. doi: 10.1038/nature10549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins M.J., Nielsen-Marsh C.M., Hiller J., Smith C.I., Roberts J.P., Prigodich R.V., Wess T.J., Csapò J., Millard A.R., Turner-Walker G. The survival of organic matter in bone: a review. Archaeometry. 2002;44:383–394. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper A., Poinar H. Ancient DNA. Do it right or not at all. Science. 2000;289:5482. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5482.1139b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crump J.A., Mintz E.D. Global trends in typhoid and paratyphoid fever. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010;50:241–246. doi: 10.1086/649541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dollinger P., Krabusch M. Kröner; 1998. Die Hanse. [Google Scholar]

- Duggan A.T., Perdomo M.F., Piombino-Mascali D., Marciniak S., Poinar D., Emery M.V., Buchmann J.P., Duchêne S., Jankauskas R., Humphreys M. 17th century Variola virus reveals the recent history of smallpox. Curr. Biol. 2016;26:3407–3412. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.10.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouquet G., Zeilinger G. Philipp von Zabern; 2011. Katastrophen im Spätmittelalter. [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski M., Schmitt G. Und das Wasser fließt in Röhren. Wasserversorgung und Wasserkünste in Lübeck. In: Gläser M., editor. Die Archäologie des Mittelalters und Bauforschung im Hanseraum. Kulturhistorisches Museums Rostock; 1993. pp. 217–223. [Google Scholar]

- Graßmann A. Schmidt-Römhild; 2005. Das Hansische Kontor zu Bergen und die Lübecker Bergenfahrer: International Workshop Lübeck 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Haensch S., Bianucci R., Signoli M., Rajerison M., Schultz M., Kacki S., Vermunt M., Weston D.A., Hurst D., Achtman M. Distinct clones of Yersinia pestis caused the black death. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001134. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammel-Kiesow R. Wachholtz; 2006. Häuser und Höfe in Lübeck. Historische, archäologische und baugeschichtliche Beiträge zur Geschichte der Hansestadt im Spätmittelalter und in der frühen Neuzeit. [Google Scholar]

- Hübler R., Key F.M., Warinner C., Bos K.I., Krause J., Herbig A. HOPS: automated detection and authentication of pathogen DNA in archaeological remains. Genome Biol. 2019;20:280. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1903-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibs J.H. Die Pest in Schleswig-Holstein von 1350 bis 1547/48: Eine sozialgeschichtliche Studie über eine wiederkehrende Katastrophe. In: Hoffmann E., editor. Kieler Werkstücke: Reihe A, Beiträge zur schleswig-holsteinischen und skandinavischen Geschichte 12. Peter Lang; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kahlow S. Die Pest als Interpretationsproblem mittelalterlicher und frühneuzeitlicher Massengräber. Bulletin der Schweizerischen Gesellschaft für Anthropologie. 2007;13:97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Key F.M., Posth C., Esquivel-Gomez L.R., Hübler R., Spyrou M.A., Neumann G.U., Furtwängler A., Sabin S., Burri M., Wissgott A. Emergence of human-adapted Salmonella enterica is linked to the Neolithization process. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2020;4:324–333. doi: 10.1038/s41559-020-1106-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koppmann K. Die Chroniken der niedersächsischen Städte. Lübeck. Band 1. S. Hirzel; 1884. [Google Scholar]

- Koppmann K. Die Chroniken der niedersächsischen Städte. Lübeck. Band 2. S. Hirzel; 1899. [Google Scholar]

- Krause-Kyora B., Nutsua M., Boehme L., Pierini F., Pedersen D.D., Kornell S.-C., Drichel D., Bonazzi M., Möbus L., Tarp P. Ancient DNA study reveals HLA susceptibility locus for leprosy in medieval Europeans. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:1569. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03857-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause-Kyora B., Susat J., Key F.M., Kühnert D., Bosse E., Immel A., Rinne C., Kornell S.-C., Yepes D., Franzenburg S. Neolithic and medieval virus genomes reveal complex evolution of hepatitis B. Elife. 2018;7:e36666. doi: 10.7554/eLife.36666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W.-Q., Feng Y., Wang Y., Zou Q.-H., Chen F., Guo J.-T., Peng Y.-H., Jin Y., Li Y.-G., Hu S.-N. Salmonella paratyphi C: genetic divergence from Salmonella choleraesuis and pathogenic convergence with Salmonella typhi. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4510. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüdecke T. Vom Brunnenwasser zum "Kunstwasser" – die Wasserversorgung im mittelalterlichen und frühneuzeitlichen Lübeck. In: Frerichs K., editor. Archäologie in Lübeck. Erkenntnisse von Archäologie und Bauforschung zur Geschichte und Vorgeschichte der Hansestadt 3. Hansestadt Lübeck; 1980. pp. 97–100. [Google Scholar]

- Lütgert S.A. Archäologische Untersuchungen der Massenbestattungen am Heiligen-Geist-Hospital zu Lübeck: Auswertung der Befunde und Funde. In: Gläser M., editor. Lübecker Schriften zu Archäologie und Kulturgeschichte 26. Rudolf Habelt; 2002. pp. 139–243. [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary N.A., Wright M.W., Brister J.R., Ciufo S., Haddad D., McVeigh R., Rajput B., Robbertse B., Smith-White B., Ako-Adjei D. Reference sequence (RefSeq) database at NCBI: current status, taxonomic expansion, and functional annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D733–D745. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prechel M. Anthropologische Untersuchungen der Skelettreste aus einem Pestmassengrab am Heiligen-Geist-Hospital zu Lübeck. In: Fehring G.P., editor. Lübecker Schriften zu Archäologie und Kulturgeschichte 24. Rudolf Habelt; 1996. pp. 323–339. [Google Scholar]

- Prechel M. Eine Lübecker Population von 1350 – Krankheiten und Mangelerscheinungen. In: Gläser M., editor. Lübecker Schriften zu Archäologie und Kulturgeschichte 26. Rudolf Habelt; 2002. pp. 245–286. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Vargas F.M., Abu-El-Haija M.A., Gómez-Duarte O.G. Salmonella infections: an update on epidemiology, management, and prevention. Trav. Med. Infect. Dis. 2011;9:263–277. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuenemann V.J., Singh P., Mendum T.A., Krause-Kyora B., Jäger G., Bos K.I., Herbig A., Economou C., Benjak A., Busso P. Genome-wide comparison of medieval and modern Mycobacterium leprae. Science. 2013;341:179–183. doi: 10.1126/science.1238286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuenemann V.J., Avanzi C., Krause-Kyora B., Seitz A., Herbig A., Inskip S., Bonazzi M., Reiter E., Urban C., Dangvard Pedersen D. Ancient genomes reveal a high diversity of Mycobacterium leprae in medieval Europe. PLoS Pathog. 2018;14:e1006997. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singman J.L. Greenwood Press; 1999. Daily Life in Medieval Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Spyrou M.A., Tukhbatova R.I., Feldman M., Drath J., Kacki S., Beltrán de Heredia J., Arnold S., Sitdikov A.G., Castex D., Wahl J. Historical Y. pestis genomes reveal the European black death as the source of ancient and modern plague pandemics. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;19:874–881. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spyrou M.A., Keller M., Tukhbatova R.I., Scheib C.L., Nelson E.A., Andrades Valtueña A., Neumann G.U., Walker D., Alterauge A., Carty N. Phylogeography of the second plague pandemic revealed through analysis of historical Yersinia pestis genomes. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:4470. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12154-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susat J., Bonczarowska J.H., Pētersone-Gordina E., Immel A., Nebel A., Gerhards G., Krause-Kyora B. Yersinia pestis strains from Latvia show depletion of the pla virulence gene at the end of the second plague pandemic. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:14628. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-71530-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzzau S., Brown D.J., Wallis T., Rubino S., Leori G., Bernard S. Host adapted serotypes of Salmonella enterica. Epidemiol. Infect. 2000;125:229–255. doi: 10.1017/s0950268899004379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vågene Å.J., Herbig A., Campana M.G., Robles García N.M., Warinner C., Sabin S., Spyrou M.A., Andrades Valtueña A., Huson D., Tuross N. Salmonella enterica genomes from victims of a major sixteenth-century epidemic in Mexico. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2018;2:520–528. doi: 10.1038/s41559-017-0446-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warinner C., Herbig A., Mann A., Fellows Yates J.A., Weiß C.L., Burbano H.A., Orlando L., Krause J. A robust framework for microbial archaeology. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 2017;31:321–356. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-091416-035526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . Vol. 93. 2018. pp. 153–172.https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272272/WER9313.pdf (Typhoid Vaccines: WHO Position Paper – March 2018, Weekly Epidemiological Record No. 13). [Google Scholar]

- Yue R.P.H., Lee H.F., Wu C.Y.H. Trade routes and plague transmission in pre-industrial Europe. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:12973. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-13481-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z., Lundstrøm I., Tran-Dien A., Duchêne S., Alikhan N.-F., Sergeant M.J., Langridge G., Fotakis A.K., Nair S., Stenøien H.K. Pan-genome analysis of ancient and modern Salmonella enterica demonstrates genomic stability of the invasive para C lineage for millennia. Curr. Biol. 2018;28:2420–2428.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.05.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z., Alikhan N.-F., Mohamed K., Fan Y., Achtman M. The EnteroBase user's guide, with case studies on Salmonella transmissions, Yersinia pestis phylogeny, and Escherichia core genomic diversity. Genome Res. 2020;30:138–152. doi: 10.1101/gr.251678.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The accession number for the data reported in this paper is available through the European Nucleotide Archive: PRJEB41353 (https://www.ebi.ac.uk).