Abstract

Medication non-adherence is one of the major problems in treating patients with depression. Non-adherence results in an increased risk of relapse and reduced quality of life. The objective of this review was to review and summarize studies that focused on the factors associated with antidepressant medication non-adherence in patients with depression. Literature searches were performed using PubMed/Medline and Google Scholar. The search was limited to articles published in the English language in peer-reviewed journals between January 2000 and December 2019. Studies that analyzed factors of non-compliance in patients with depressive disorders were included in the review.

Patient-related factors such as forgetfulness, comorbidities, and misconceptions about the disease and medication, medication-related factors, polypharmacy, side effects, pill burden and cost, healthcare system-related factors, including physician-patient interactions, sociocultural factors such religious and cultural beliefs and stigma, and logistic factors were found to be the major factors associated with antidepressant non-adherence. Efforts should be made to increase patient adherence to antidepressants by strengthening physician-patient relationships, simplifying medication regimens, and rectifying myths and beliefs held by patients with scientific information and explanations.

Keywords: Adherence, antidepressants, depression, associated factors

INTRODUCTION

Depression has become a major public health concern with an increased prevalence and global disease burden due to the associated mental, social, and interpersonal dysfunction.1 According to the World Health Organization, by 2020, depression will be the second-highest known cause of disability worldwide.2 It is characterized by a sad mood, pessimistic thoughts, lowered interest in day-to-day activities, poor concentration, insomnia or increased sleep, significant weight loss or gain, decreased energy, continuous feelings of guilt and worthlessness, decreased libido, and suicidal thoughts occurring at least once every two weeks.1,3 Antidepressant drugs are the most effective and widely used forms of treatment for depression.4 Despite the availability of many effective antidepressants, 50% patients do not achieve a complete cure of symptoms and even experience recurrence.5,6 Therefore, in many patients, depression becomes a chronic disorder and may require lifelong antidepressant treatment. For the desired treatment outcome, adherence to antidepressant medication plays a crucial role, and non-adherence is the key problem associated with antidepressant treatment. Adherence has been defined as “the extent to which a person’s behavior regarding taking medication, following a diet, or executing a lifestyle (change) corresponds with recommendations from a healthcare provider”.7 The failure of patients to follow medical advice results in a risk of relapse and reduced quality of life. Many factors, be they patient, medicine, health system, or social and cultural factors, all are associated with patient non-adherence to prescribed antidepressants. Hence, this study was conducted to review and summarize studies focused on the factors associated with antidepressant medication non-adherence in patients with depression.

METHODS

Data sources, literature search, and selection

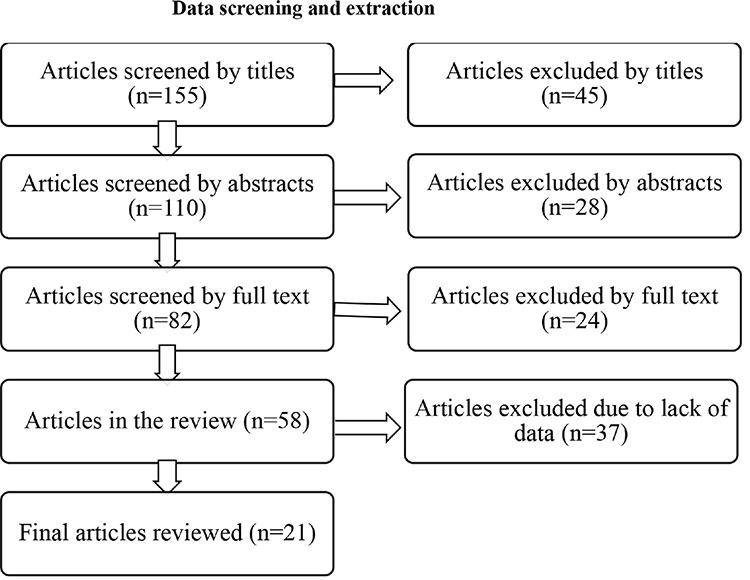

A comprehensive literature review was conducted using PubMed/Medline and Google Scholar. The search was limited to articles published in the English language in peer-reviewed journals between 2000 and 2019. The keywords used for the article search were depression, depressive patients, antidepressant, antidepressant adherence, patient compliance, and discontinuation of antidepressants. We also included articles listed in the author’s reference lists and those listed in other systematic reviews. Studies were selected on the basis of relevance. Full articles on those studies that were deemed relevant to our study title were fully reviewed. This study is a narrative review and does not include any statistical analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Data screening and extraction

Study selection

For inclusion in our review, studies must have included adult or elderly patients, irrespective of gender, diagnosed with depression, and prescribed antidepressants by physicians. Literature could be of varying methodologies i.e. observational, prospective, cross-sectional, retrospective, or survey.

Our study outcomes were the factors that caused non-adherence to antidepressants among patients with depressive disorder. Studies that did not meet our criteria were excluded during the review. Studies were discarded if they were clinical trials or reviews.

RESULTS

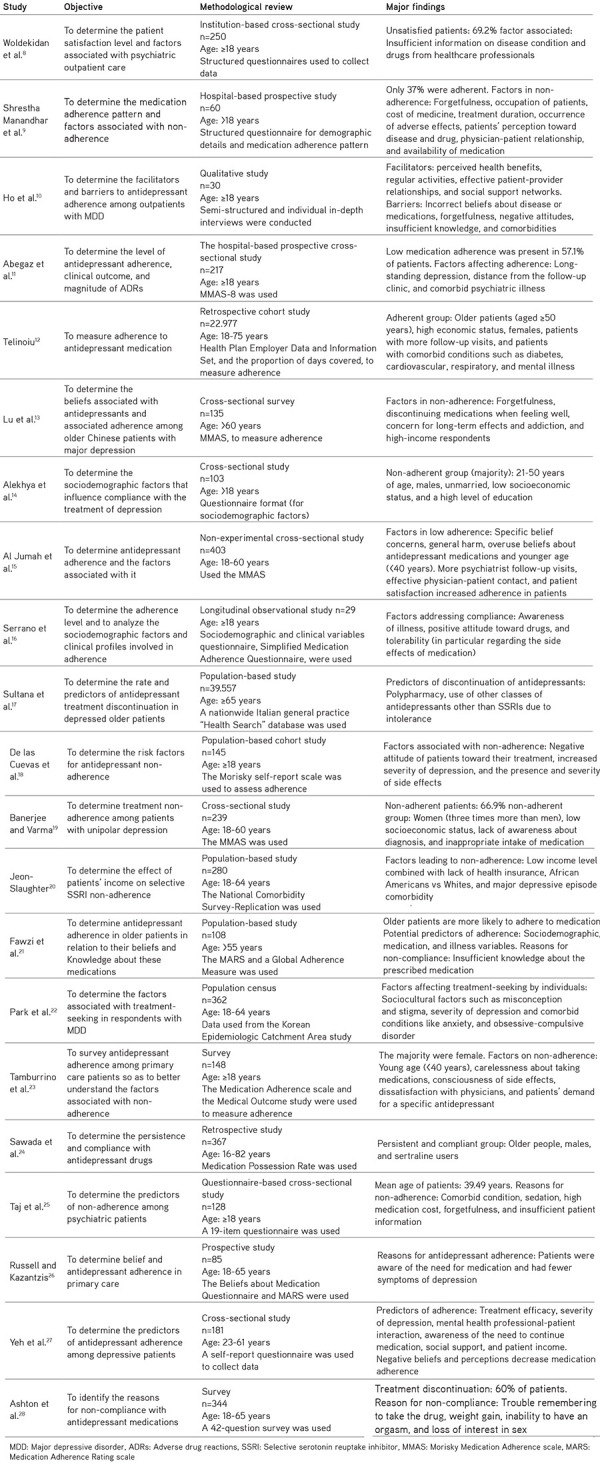

One hundred fifty-five articles were selected by title/abstract; finally, 21 articles were included. Table 1 shows the main findings of these studies. Two studies were performed in Ethiopia,8,9,10,11 one in Nepal,9 one in Malaysia,10 one in Island,12 two in China,13,27 two in India,14,17 one in Saudi Arabia,15 two in Spain16,19, one in Italy,18 three in the United States,20,23,28one in the UK,21 one in Korea,22 one in Japan,24one in Pakistan,25 and one in New Zealand.26

Table 1. Objectives, methods, and major findings of the included studies.

DISCUSSION

a. Sociodemographic factors

From this review, it was observed that the majority of patients who were non-adherent to their prescribed antidepressants were younger patients aged <40 years.15,21,23 Non-adherence among younger patients could be due to having less experience with depression and associated medications. In contrast, older patients may have more experience with depressive episodes and antidepressants, which makes them more willing to complete their prescribed doses.15,23 Additionally, antidepressants are associated with common side effects such as weight gain and impaired sexual function, which may make it troublesome for younger patients to adhere to antidepressant drugs.15,21,23,29,30,31

Female patients were found to be less adherent to prescribed antidepressants than males.19,23,24,32 Women play multiple roles in the family and society, for example, as homemakers, spouses, mothers, professionals, and caregivers, which might cause them difficulty visiting the hospital and making them unable to adhere to their prescribed medications. However, findings contrary to these studies were reported by other works,12,14 where males were less adherent to their regimens. This could be because they were not permitted leave from the office, or they may have been concerned about a pay deduction on the particular day they took leave to visit the hospital. Their inability to attend hospital visits on work days might have kept them from adhering to their treatment.12,14,19,29,33

One of the study14 showed that non-adherence and level of education are inversely proportional. This means that when the level of education increases, adherence decreases, and vice versa. Highly educated people fear side effects and long-term effects of the drugs, which might be due to lack of appropriate information about disease and the drugs prescribed to them and their unwillingness to communicate with their healthcare personnel.14,34

Many studies predicted that people of low socioeconomic status would be less adherent to antidepressants.12,14,19,20,27 This could be due to unemployment or an unstable income, inability to afford medications in the long term, and frequent appointments with their physician becoming expensive for them, which leads to premature discontinuation and non-adherence to drug regimens.27,35 In contrast, another work13 found that patients with a high socioeconomic status were less adherent to antidepressants. This could be because higher-income people generally have a high social status and education level. They might be more concerned about the side effects or potential for dependence on antidepressants, which finally leads to decreased adherence.

b. Patient-related factors

From the literature review, patients often forgetting to take their medications was found to be a common patient-related factor in antidepressant non-adherence.9,10,13,25,28,36,37 Inappropriate intake of medication or patient carelessness were other reasons for non-adherence.9,19,23

Patients have incorrect beliefs about the disease itself or prescribed antidepressants.10,13,15,22,27 From the findings of our review, a poor understanding of mental illness and medication was found to be the main barrier to depression treatment and hence, to adherence. Even after being diagnosed with depression, many did not consider themselves as having a mental illness. They believed they could easily overcome their mental illness on their own.22,38 They also believed that it would be resolved by positive thinking or having a complete rest without taking antidepressants.3 Some people accept depression as a normal part of their aging process, and some even consider it as a result of bad fortune in their lives or a weak personality, rather than a mental illness.39,40

The majority of patients taking antidepressants have misconceptions about them. They believe there is no need to take medication in the absence of any signs or symptoms. They believe they can take less medication or simply discontinue the medication themselves when they feel better.10,13,41,42

The patient’s decision to adhere to antidepressants mainly depends on the balance between necessity and concern about the safety and efficacy of the prescribed medication.43,44 Therefore, many people believe that long-term use of antidepressants is toxic and may lead to kidney damage. They were also concerned with the potential for addiction and psychological dependence on antidepressants, all of which affect their adherence to treatment.10,13,15

Patients with a positive attitude towards their disease and medication and an awareness of their illness adhere more to their regimens.9,10,16,18,19,26,27 They believe they will return to normal functioning if they continue to take their medications. They will communicate regularly with their physicians to enhance their knowledge about their own mental illnesses and medications.10 All this will help them cope with the response and lead to better health outcomes.45

Comorbidity, polypharmacy, and non-adherence are inter-related with each other. Comorbidity increases the number of medications be taken by the patients.10,17,25 Patients will feel pill burdens and even an economic burden because they must take different types of medications. The complex dosing schedule and the intention to save money may force patients to discontinue their medication, leading to non-compliance.10,20 Comorbidity also leads to logistic problems, as patients must seek medical advice from more than one physician, obtaining appointments and timely medication refills time and again.25

c. Medication-related factors

It is evident from many studies that the majority of patients refuse to continue antidepressants due to the prevalent side effects of the drug prescribed.9,11,13,18,25,26,28 Patients mostly prefer medications that have a lower risk of weight gain, sexual dysfunction, and fatigue.28 Antidepressants are reported to cause many adverse effects such as sedation, restlessness, tremor, dry mouth, decreased libido, weight gain, irregular menstrual cycles, and impotence. These unpleasant effects may impair patient quality of life and self-esteem, resulting in non-adherence to prescribed antidepressants.46,47,48 In two of the studies,17,24 patients prescribed with antidepressants other than selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) were more likely to be non-adherent. This might be due to the lower side effect profile, low overdose-related cardiotoxicity, better tolerability, and overall favorable risk-benefit ratio attributed to SSRIs.11,49,50,51,52

Adherence to treatment is greatly influenced by physician-patient interactions. One of the common reason for non-adherence was the failure of physicians to provide adequate information on patients’ illness and medications prescribed.9,15,21,25,27 The studies found that the most common patient complaint was the failure of the physician to explain the timing and dosing of the medication completely, along with the benefits of therapy, and the consequence was non-adherence.21,25,46,53 Similarly, not trusting the physician and dissatisfaction with the physician and their prescribed medication also led to patients being non-adherent to their treatment.10,15,23,54,55

Due to multiple prescribers, problems communicating with physicians, frequent follow-up, long waiting times in hospitals, repeated medication refills, and unavailability of prescribed medications,19 many patients choose to discontinue their medications.9,10 Patients lose confidence in their physician when there are multiple prescribers, which ultimately affects their medication-taking behavior. Some patients alter/stop their medication without informing their physician, as they find it difficult to communicate with them. To avoid long wait times, patients skip their appointments, leading to an insufficient supply of medication at home.10

d. Sociocultural factors

Lower adherence to medication depends on the patient’s perception of their illness, which may differ according to the religion and culture to which they belong.13,56 A study10 collected the beliefs of people from different religions and cultures. It stated that people from Malaysia believe that mental illness is a social punishment for particular people, or an illness of the soul caused by weakness of the spirit. Similarly, Chinese people believe that mental illness is a symbol of lack of self-worth, which is measured in terms of education and monetary gain that brings honor to the family. Likewise, Indians believe that one gets a mental illness from evildoers.57 All of these beliefs create barriers to pursuing and sticking to antidepressant regimens. Some patients want to determine experimentally whether being prayerful will cure their depression, which forces them to stop taking the medication.10,13,38

Depression is still considered a social stigma. Many regard it as a sign of a personal weakness.26 Regular social support and motivation from family members and co-workers help depressive patients get going their antidepressant treatment.22,27,58 Due to fear of being stigmatized by society, many patients do not reveal their mental illness,22 which influences their adherence to medication. Unsupportive family members and co-workers also discourage patients from continuing their medication,10 which further worsens their mental illness.

e. Logistical factors

Many patients who live far from city areas or hospitals have poor access to healthcare facilities and hence hinder patients from adhering to antidepressants.9,10,11

CONCLUSION

From our review, we conclude that patient-related factors such as forgetfulness, comorbidity, and misconception about the disease and medication; medication-related factors such as polypharmacy, side effects, pill burden, and cost; healthcare-system-related factors including the physician-patient interaction; sociocultural factors such as religious and cultural beliefs and stigma; and logistic factors are the major barriers to antidepressant adherence. Hence, efforts should be made to increase patient adherence by strengthening physician-patient relationships. Physicians should emphasize patient education that includes an explanation of the drug, dosage, duration, and timing of administration, possible side effects, adverse effects, lag time before the onset of treatment and relief of symptoms, and consequences of non-adherence. In the case of comorbid conditions, physicians should simplify the medication regimen. Additionally, they should focus on rectifying the myths and beliefs held by patients with scientific information and explanations.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: No conflict of interest was declared by the authors. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

References

- 1.Tejashwini K, Bhushan A, Suma S, Katte R. Drug utilization pattern and adverse drug reactions in patients on antidepressants. National Journal of Physiology, Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 2019;9:4–11. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Depression WH. Other common mental disorders: global health estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2017:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang CH, Chen CM, Hsu KY, Wang LJ, Chen SY, Lee CF. The Prescription Pattern and Analyses of Antidepressants under the National Health Insurance Policy in Taiwan. Taiwanese Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;25:76–85. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauer M, Monz BU, Montejo AL, Quail D, Dantchev N, Demyttenaere K, Garcia-Cebrian A, Grassi L, Perahia DGS, Reed C, Tylee A. Prescribing patterns of antidepressants in Europe: results from the Factors Influencing Depression Endpoints Research (FINDER) study. Eur Psychiatry. 2008;23:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. Depression: The Treatment and Management of Depression in adults (Updated Edition). National Clinical Practice Guideline Number 90. London, UK: British Psychological Society and Royal College of Psychiatrists. 2009. [Internet]

- 6.Solomon DA, Keller MB, Leon AC, Mueller TI, Lavori PW, Shea MT, Coryell W, Warshaw M, Turvey C, Maser JD, Endicott J. Multiple recurrences of major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:229–233. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Adherence to Long-Term Therapies: evidence for action. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. 2003. [Internet]

- 8.Woldekidan NA, Gebresillassie BM, Alem RH, Gezu BF, Abdela OA, Asrie AB. Patient Satisfaction with Psychiatric Outpatient Care at University of Gondar Specialized Hospital: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Psychiatry J. 2019;2019:5076750. doi: 10.1155/2019/5076750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shrestha Manandhar J, Shrestha R, Basnet N, Silwal P, Shrestha H, Risal A, Kunwar D. Study of adherence pattern of antidepressants in patients with depression. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ) 2017;15:3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ho SC, Jacob SA, Tangiisuran B. Barriers and facilitators of adherence to antidepressants among outpatients with major depressive disorder: A qualitative study. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0179290 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abegaz TM, Sori LM, Toleha HN. Self-reported adverse drug reactions, medication adherence, and clinical outcomes among major depressive disorder patients in Ethiopia: A prospective hospital based study. Psychiatry J. 2018;2018:9274278. doi: 10.1155/2018/9274278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Telinoiu CM. Measuring adherence with antidepressant medication: Comparison of HEDIS and PDC methodologies. 2016. Open Access Master’s Thesis. Paper 823. [Internet]

- 13.Lu Y, Arthur D, Hu L, Cheng G, An F, Li Z. Beliefs about antidepressant medication and associated adherence among older Chinese patients with major depression: A cross-sectional survey. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2016;25:71–79. doi: 10.1111/inm.12181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alekhya P, Sriharsha M, Venkata Ramudu R, Shivanandh B, Priya Darsini T, Reddy KSK, Hrushikesh Reddy Y. Adherence to antidepressant therapy: Sociodemographic factor wise distribution. Int J Pharm Clin Res. 2015;7:180–184. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al Jumah K, Hassali MA, Al Qhatani D, El Tahir K. Factors associated with adherence to medication among depressed patients from Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2014;10:2031–2037. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S71697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Serrano MJ, Vives M, Mateu C, Vicens C, Molina R, Puebla-Guedea M, Gili M. Therapeutic adherence in primary care depressed patients: a longitudinal study. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2014;42:91–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sultana J, Italiano D, Spina E, Cricelli C, Lapi F, Pecchioli S, Gambassi G, Trifirò G. Changes in the prescribing pattern of antidepressant drugs in elderly patients: an Italian, nationwide, population-based study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;70:469–478. doi: 10.1007/s00228-013-1636-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De las Cuevas C, Peñate W, Sanz EJ. Risk factors for non-adherence to antidepressant treatment in patients with mood disorders. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;70:89–98. doi: 10.1007/s00228-013-1582-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Banerjee S, Varma RP. Factors Affecting non-adherence among patients diagnosed with unipolar depression in a psychiatric department of a tertiary hospital in Kolkata, India. Depress Res Treat. 2013;2013:809542. doi: 10.1155/2013/809542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jeon-Slaughter H. Economic factors in of patients’ nonadherence to antidepressant treatment. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47:1985–1998. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0497-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fawzi W, Abdel Mohsen MY, Hashem AH, Moussa S, Coker E, Wilson KC. Beliefs about medications predict adherence to antidepressants in older adults. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24:159–169. doi: 10.1017/S1041610211001049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park S, Cho MJ, Bae JN, Chang SM, Jeon HJ, Hahm BJ, Son JW, Kim SG, Bae A, Hong JP. Comparison of treated and untreated major depressive disorder in a nationwide sample of Korean adults. Community Ment Health J. 2012;48:363–371. doi: 10.1007/s10597-011-9434-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tamburrino MB, Nagel RW, Chahal MK, Lynch DJ. Antidepressant medication adherence: a study of primary care patients. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;11:205–211. doi: 10.4088/PCC.08m00694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sawada N, Uchida H, Suzuki T, Watanabe K, Kikuchi T, Handa T, Kashima H. Persistence and compliance to antidepressant treatment in patients with depression: a chart review. BMC Psychiatry. 2009;9:38. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-9-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taj F, Tanwir M, Aly Z, Khowajah AA, Tariq A, Syed FK, Waqar F, Shahzada K. Factors associated with non-adherence among psychiatric patients at a tertiary care hospital, Karachi, Pakistan: a questionnaire based crosssectional study. J Pak Med Assoc. 2008;58:432–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Russell J, Kazantzis N. Medication beliefs and adherence to antidepressants in primary care. N Z Med J. 2008;121:14–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yeh MY, Sung SC, Yorker BC, Sun CC, Kuo YL. Predictors of adherence to an antidepressant medication regimen among patients diagnosed with depression in Taiwan. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2008;29:701–717. doi: 10.1080/01612840802129038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ashton AK, Jamerson BD, L Weinstein W, Wagoner C. Antidepressantrelated adverse effects impacting treatment compliance: Results of a patient survey. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 2005;66:96–106. doi: 10.1016/j.curtheres.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zivin K, Ganoczy D, Pfeiffer PN, Miller EM, Valenstein M. Antidepressant adherence after psychiatric hospitalization among VA patients with depression. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2009;36:406–415. doi: 10.1007/s10488-009-0230-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bambauer KZ, Soumerai SB, Adams AS, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D. Provider and patient characteristics associated with antidepressant nonadherence: the impact of provider specialty. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:867–873. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krivoy A, Balicer RD, Feldman B, Hoshen M, Zalsman G, Weizman A, Shoval G. The impact of age and gender on adherence to antidepressants: a 4-year population-based cohort study. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2015;232:3385–3390. doi: 10.1007/s00213-015-3988-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burra TA, Chen E, McIntyre RS, Grace SL, Blackmore ER, Stewart DE. Predictors of self-reported antidepressant adherence. Behav Med. 2007;32:127–134. doi: 10.3200/BMED.32.4.127-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goethe JW, Woolley SB, Cardoni AA, Woznicki BA, Piez DA. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor discontinuation: side effects and other factors that influence medication adherence. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;27:451–458. doi: 10.1097/jcp.0b013e31815152a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olfson M, Marcus SC, Tedeschi M, Wan GJ. Continuity of antidepressant treatment for adults with depression in the United States. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:101–108. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chapman JR. Compliance: the patient, the doctor, and the medication? Transplantation. 2004;77:782–786. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000110411.23547.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coe AB, Moczygemba LR, Gatewood SB, Osborn RD, Matzke GR, Goode JV. Medication adherence challenges among patients experiencing homelessness in a behavioral health clinic. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2015;11:e110–e120. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sajatovic M, Levin J, Fuentes-Casiano E, Cassidy KA, Tatsuoka C, Jenkins JH. Illness experience and reasons for nonadherence among individuals with bipolar disorder who are poorly adherent with medication. Compr Psychiatry. 2011;52:280–287. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Conner KO, Lee B, Mayers V, Robinson D, Reynolds III CF, Albert S, Brown C. Attitudes and beliefs about mental health among African American older adults suffering from depression. Journal of aging studies. 2010;24:266–277. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jang Y, Chiriboga DA, Herrera JR, Tyson DM, Schonfeld L. Attitudes toward mental health services in Hispanic older adults: the role of misconceptions and personal beliefs. Community Ment Health J. 2011;47:164–170. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9274-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sarkisian CA, Lee-Henderson MH, Mangione CM. Do depressed older adults who attribute depression to “old age” believe it is important to seek care? J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:1001–1005. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2003.30215.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jacob SA, Ab Rahman AF, Hassali MA. Attitudes and beliefs of patients with chronic depression toward antidepressants and depression. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:1339–1347. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S82563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khan TM, Sulaiman SA, Hassali MA. Mental health literacy towards depression among non-medical students at a Malaysian university. Ment Health Fam Med. 2010;7:27–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aikens JE, Nease DE Jr, Klinkman MS. Explaining patients’ beliefs about the necessity and harmfulness of antidepressants. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:23–29. doi: 10.1370/afm.759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aikens JE, Nease DE Jr, Nau DP, Klinkman MS, Schwenk TL. Adherence to maintenance-phase antidepressant medication as a function of patient beliefs about medication. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3:23–30. doi: 10.1370/afm.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brown C, Battista DR, Sereika SM, Bruehlman RD, Dunbar-Jacob J, Thase ME. Primary care patients’ personal illness models for depression: relationship to coping behavior and functional disability. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29:492–500. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taj R, Khan S. A study of reasons of non-compliance to psychiatric treatment. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2005;17:26–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Merikangas AK, Mendola P, Pastor PN, Reuben CA, Cleary SD. The association between major depressive disorder and obesity in US adolescents: results from the 2001-2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Behav Med. 2012;35:149–154. doi: 10.1007/s10865-011-9340-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Uher R, Farmer A, Henigsberg N, Rietschel M, Mors O, Maier W, Kozel D, Hauser J, Souery D, Placentino A, Strohmaier J, Perroud N, Zobel A, Rajewska-Rager A, Dernovsek MZ, Larsen ER, Kalember P, Giovannini C, Barreto M, McGuffin P, Aitchison KJ. Adverse reactions to antidepressants. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195:202–210. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.061960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Trifirò G, Barbui C, Spina E, Moretti S, Tari M, Alacqua M, Caputi AP; UVEC group, Arcoraci V. Antidepressant drugs: prevalence, incidence and indication of use in general practice of Southern Italy during the years 2003-2004. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16:552–559. doi: 10.1002/pds.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bauer M, Monz BU, Montejo AL, Quail D, Dantchev N, Demyttenaere K, Garcia-Cebrian A, Grassi L, Perahia DG, Reed C, Tylee A. Prescribing patterns of antidepressants in Europe: results from the Factors Influencing Depression Endpoints Research (FINDER) study. Eur Psychiatry. 2008;23:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spina E, Trifirò G, Caraci F. Clinically significant drug interactions with newer antidepressants. CNS Drugs. 2012;26:39–67. doi: 10.2165/11594710-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Trifirò G, Dieleman J, Sen EF, Gambassi G, Sturkenboom MC. Risk of ischemic stroke associated with antidepressant drug use in elderly persons. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30:252–258. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181dca10a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Roter D. The enduring and evolving nature of the patient-physician relationship. Patient Educ Couns. 2000;39:5–15. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(99)00086-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van Os TW, van den Brink RH, Tiemens BG, Jenner JA, van der Meer K, Ormel J. Communicative skills of general practitioners augment the effectiveness of guideline-based depression treatment. J Affect Disord. 2005;84:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hunot VM, Horne R, Leese MN, Churchill RC. A cohort study of adherence to antidepressants in primary care: the influence of antidepressant concerns and treatment preferences. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;9:91–99. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v09n0202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cho SJ, Lee JY, Hong JP, Lee HB, Cho MJ, Hahm BJ. Mental health service use in a nationwide sample of Korean adults. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009;44:943–951. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Haque A. Mental health concepts and program development in Malaysia. Journal of Mental Health. 2005;14:183–195. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee MS, Lee HY, Kang SG, Yang J, Ahn H, Rhee M, Ko YH, Joe SH, Jung IK, Kim SH. Variables influencing antidepressant medication adherence for treating outpatients with depressive disorders. J Affect Disord. 2010;123:216–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]