Abstract

This cross-sectional study examines the extent to which methamphetamine overdose deaths vary by sex and race and ethnicity in the US.

US age-adjusted rates of drug overdose deaths involving methamphetamine increased nearly 5-fold during 2012-2018.1 Although addiction outcomes can be improved with sex-specific and culturally tailored prevention and treatment interventions, the extent to which fatalities differ as functions of sex and race and ethnicity has not been analyzed, to our knowledge.

Methods

This study used existing deidentified public health surveillance data and was exempt from institutional review board review in accordance with the Common Rule. Data were from National Vital Statistics System files for multiple causes of death. Drug overdose deaths were those assigned an underlying cause of death with International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes (X40-X44 [unintentional], X60-X64 [suicide], X85 [homicide], and Y10-Y14 [undetermined intent]). Overdose deaths involving psychostimulants with abuse potential (predominantly corresponding to methamphetamine) were those with ICD-10 code T43.6.2

Age-adjusted overdose death rates during 2011-2018 were stratified by sex and race/ethnicity and limited to aged 25 to 54 years because recent national data show that four-fifths of current methamphetamine users were aged 25 to 54 years.3 Joinpoint Regression Program (version 4.8.01) was used to test for significant changes (joinpoints) in nonlinear trends using bayesian information criteria. A 2-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

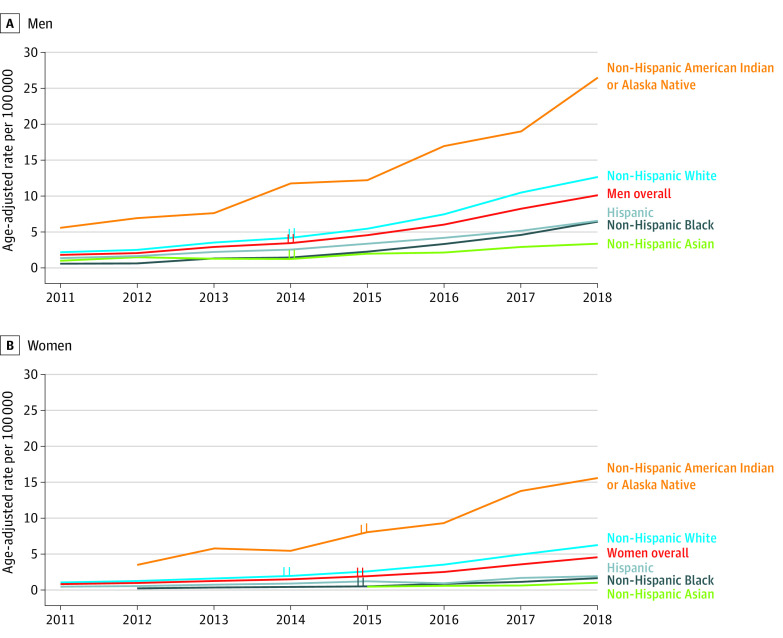

During 2011-2018 (Figure), age-adjusted rates for methamphetamine-involved deaths increased from 1.8 to 10.1 per 100 000 among men (average annual percentage change [AAPC], 29.1; 95% CI, 25.5-32.8; P < .001) and from 0.8 to 4.5 per 100 000 among women (AAPC, 28.1; 95% CI, 25.1-31.2; P < .001) (Table). Within each sex, non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native individuals had the highest rates, increasing from 5.6 to 26.4 per 100 000 among men during 2011-2018 (AAPC, 24.2; 95% CI, 23.0-25.5; P < .001) and from 3.6 to 15.6 per 100 000 among women during 2012-2018 (AAPC, 26.4; 95% CI, 15.9-37.7; P < .001). During 2011-2018, non-Hispanic White individuals had the second highest rates, increasing from 2.2 to 12.6 per 100 000 among men (AAPC, 29.8; 95% CI, 24.3-35.4; P < .001) and from 1.1 to 6.2 per 100 000 among women (AAPC, 29.1; 95% CI, 25.2-33.2; P < .001); rates among Hispanic individuals increased from 1.4 to 6.6 per 100 000 for men and from 0.5 to 2.0 per 100 000 for women. Among non-Hispanic Asian individuals in 2018, rates increased to 3.4 per 100 000 for men and to 1.1 per 100 000 for women. Non-Hispanic Black individuals had low rates. However, among men during 2011-2018, rates for non-Hispanic Black individuals increased from 0.6 to 6.4 per 100 000 with the highest AAPC (AAPC, 41.4; 95% CI, 39.5-43.2; P < .001); among women during 2012-2018, rates for non-Hispanic Black individuals increased from 0.2 to 1.7 per 100 000 with an AAPC (AAPC, 35.5; 95% CI, 28.6-42.8; P < .001), similar to non-Hispanic White and American Indian and Alaska Native women.

Figure. Trends in Methamphetamine Deaths Among US Men and Women Aged 25-54 Years Overall and by Race and Ethnicity.

Joinpoints identified indicate significant changes in nonlinear trends using bayesian information criteria. Annual percentage change trends are detailed in the Table.

Table. Trends in Age-Adjusted Overdose Death Rates per 100 000 (95% CI) Involving Methamphetaminea Among Adults Aged 25-54 Years by Sex and Race and Ethnicity.

| 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | Trends | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | ||||||||||||

| Overall US men | 1.8 (1.7 to 1.9) |

2.1 (2.0 to 2.2) |

2.9 (2.8 to 3.1) |

3.5 (3.3 to 3.6)b |

4.6 (4.4 to 4.8) |

6.1 (5.9 to 6.3) |

8.3 (8.0 to 8.5) |

10.1 (9.9 to 10.4) |

2011-2014: APC = 26.4 (14.5 to 39.4); P = .005 |

2014-2018: APC = 31.2 (27.1 to 35.4); P < .001 | 2011-2018: AAPC = 29.1 (25.5 to 32.8); P < .001 |

|

| Non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native | 5.6 (3.7 to 8.1) |

6.9 (4.8 to 9.7) |

7.6 (5.4 to 10.4) |

11.7 (9.0 to 15.1) |

12.2 (9.3 to 15.6) |

16.9 (13.6 to 20.9) |

19.0 (15.3 to 23.2) |

26.4 (21.9 to 31.9) |

2011-2018: APC = AAPC = 24.2 (23.0 to 25.5); P < .001 | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 2.2 (2.1 to 2.4) |

2.5 (2.4 to 2.7) |

3.6 (3.4 to 3.8) |

4.2 (4.0 to 4.4)b |

5.5 (5.2 to 5.7) |

7.5 (7.2 to 7.8) |

10.5 (10.2 to 10.8) |

12.6 (12.3 to 13.0) |

2011-2014: APC = 25.6 (8.3 to 45.6); P = .02 |

2014-2018: APC = 33.0 (26.6 to 39.7); P < .001 |

2011-2018: AAPC = 29.8 (24.3 to 35.4); P < .001 |

|

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.6 (0.5 to 0.8) |

0.7 (0.5 to 0.9) |

1.4 (1.1 to 1.6) |

1.5 (1.2 to 1.8) |

2.3 (2.0 to 2.7) |

3.4 (3.0 to 3.8) |

4.6 (4.1 to 5.1) |

6.4 (5.9 to 7.0) |

2011-2018: APC = AAPC = 41.4 (39.5 to 43.2); P < .001 | |||

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 1.1 (0.7 to 1.5) |

1.5 (1.2 to 2.0) |

1.3 (1.0 to 1.7) |

1.3 (1.0 to 1.7)b |

2.0 (1.6 to 2.5) |

2.2 (1.7 to 2.7) |

3.0 (2.4 to 3.5) |

3.4 (2.9 to 4.0) |

2011-2014: APC = 5.0 (–15.6 to 30.8); P = .53 |

2014-2018: APC = 25.1 (15.8 to 35.1); P = .003 |

2011-2018: AAPC = 16.1 (8.9 to 23.7); P < .001 |

|

| Hispanic | 1.4 (1.2 to 1.6) |

1.7 (1.4 to 1.9) |

2.3 (2.0 to 2.5) |

2.6 (2.3 to 2.9) |

3.4 (3.1 to 3.7) |

4.2 (3.8 to 4.6) |

5.2 (4.8 to 5.6) |

6.6 (6.1 to 7.0) |

2011-2018: APC = AAPC = 24.8 (24.4 to 25.3); P < .001 | |||

| Women | ||||||||||||

| Overall US women | 0.8 (0.8 to 0.9) |

1.0 (0.9 to 1.1) |

1.3 (1.2 to 1.4) |

1.5 (1.4 to 1.6) |

2.0 (1.9 to 2.1)b |

2.6 (2.4 to 2.7) |

3.6 (3.5 to 3.8) |

4.5 (4.3 to 4.7) |

2011-2015: APC = 24.4 (18.0 to 31.2); P < .001 |

2015-2018: APC = 33.2 (26.2 to 40.6); P < .001 |

2011-2018: AAPC = 28.1 (25.1 to 31.2); P < .001 |

2012-2018: AAPC = 28.9 (25.1 to 32.8); P < .001 |

| Non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native | NA | 3.6 (2.2 to 5.5) |

5.8 (3.9 to 8.3) |

5.4 (3.6 to 8.0) |

8.0 (5.8 to 10.8)b |

9.4 (6.9 to 12.3 |

13.9 (10.9 to 17.4) |

15.6 (12.3 to 19.4) |

2012-2015: APC = 22.4 (–11.4 to 69.0); P = .12 |

2015-2018: APC = 30.5 (7.3 to 58.7); P = .03 |

2012-2018: AAPC = 26.4 (15.9 to 37.7); P < .001 |

|

| Non-Hispanic White | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.2) |

1.3 (1.2 to 1.4) |

1.7 (1.5 to 1.8) |

2.0 (1.9 to 2.1)b |

2.7 (2.5 to 2.8) |

3.6 (3.4 to 3.8) |

5.1 (4.8 to 5.3) |

6.2 (6.0 to 6.5) |

2011-2014: APC = 22.8 (10.4 to 36.6); P = .009 |

2014-2018: APC = 34.1 (29.5 to 38.9); P < .001 |

2011-2018: AAPC = 29.1 (25.2 to 33.2); P < .001 |

2012-2018: AAPC = 30.3 (20.6 to 40.8); P < .001 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | NA | 0.2 (0.2 to 0.4) |

0.4 (0.3 to 0.6) |

0.5 (0.3 to 0.6) |

0.5 (0.4 to 0.7)b |

0.9 (0.7 to 1.1) |

1.2 (1.0 to 1.4) |

1.7 (1.4 to 2.0) |

2012-2015: APC = 27.8 (4.3 to 56.6); P = .04 |

2015-2018: APC = 43.6 (29.1 to 59.7); P = .005 |

2012-2018: AAPC = 35.5 (28.6 to 42.8); P < .001 |

|

| Non-Hispanic Asian | NA | NA | 0.6 (0.4 to 1.0) |

NA | 0.5 (0.3 to 0.7) |

0.6 (0.4 to 0.9) |

0.6 (0.4 to 0.9) |

1.1 (0.8 to 1.4) |

Too few data points to conduct joinpoint trend analysis | |||

| Hispanic | 0.5 (0.4 to 0.7) |

0.6 (0.5 to 0.8) |

0.8 (0.6 to 1.0) |

0.9 (0.7 to 1.1) |

1.3 (1.1 to 1.5) |

1.0 (0.8 to 1.2) |

1.7 (1.5 to 2.0) |

2.0 (1.7 to 2.2) |

2011-2018: APC = AAPC = 20.9 (16.7 to 25.3); P < .001 |

2012-2018: APC = AAPC = 20.4 (15.1 to 26.0); P < .001 |

||

Abbreviations: AAPC, average APC; APC, annual percentage change; NA, not applicable because there were too few cases to report reliable estimates.

Psychostimulants with abuse potential (predominantly responding to methamphetamine).

Joinpoint, which is identified in this year indicating significant changes in nonlinear trends using a bayesian information criterion.

Discussion

Increased age-adjusted rates for methamphetamine-involved deaths for all examined racial/ethnic groups of men and women with acceleration during 2014/2015 to 2018 for many subgroups are consistent with the flourishing methamphetamine market and suggest the urgent need for effective interventions. Within each sex, American Indian and Alaska Native individuals had the highest death rates, with acceleration during 2015-2018 for women and consistent increases during 2011-2018 for men. Within each racial/ethnic group, rates were higher among men than women. However, American Indian and Alaska Native women had higher rates than non-Hispanic Black and Asian men and Hispanic men during 2012-2018. Non-Hispanic Black individuals had the fastest increases in death rates among men during 2011-2018.

Although the category used to estimate death rates from methamphetamine was based on psychostimulants, approximately 85% to 90% of psychostimulant-involved death certificates mentioned methamphetamine.2 Methamphetamine death rates may be underestimated because some overdose death certificates did not report specific drugs involved (eg, 12%-15% in 2016-2017).4 Racial misclassification suggests that even these high rates may underestimate American Indian and Alaska Native mortality.5

Methamphetamine is highly toxic. Its use is associated with pulmonary and cardiovascular pathology6 and frequently co-occurs with other substance use and mental disorders. Our results highlight the urgency to support prevention and treatment interventions for methamphetamine-related harms, especially among American Indian and Alaska Native individuals who experience sociostructural disadvantages, but whose cultural strengths can be leveraged to improve addiction outcomes.

References

- 1.Hedegaard H, Miniño AM, Warner M. Drug Overdose Deaths in the United States, 1999–2018. National Center for Health Statistics; 2020. NCHS Data Brief No. 356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drug Enforcement Administration, US Department of Justice . 2018. National drug threat assessment. Accessed September 6, 2020. https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2018-11/DIR-032-18%202018%20NDTA%20final%20low%20resolution.pdf

- 3.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration(SAMHSA) . 2019. National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). SAMHSA; September 2020.

- 4.Kariisa M, Scholl L, Wilson N, Seth P, Hoots B. Drug overdose deaths involving cocaine and psychostimulants with abuse potential—United States, 2003-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(17):388-395. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6817a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arias E, Heron M, Hakes J; National Center for Health Statistics; US Census Bureau . The validity of race and Hispanic-origin reporting on death certificates in the United States: an update. Vital Health Stat 2. 2016;172(172):1-21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wang GJ, et al. Distribution and pharmacokinetics of methamphetamine in the human body: clinical implications. PLoS One. 2010;5(12):e15269. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]