Key Points

Question

Can a brief, multicomponent, sustained care smoking cessation intervention tailored to individuals with severe mental illness facilitate treatment engagement and abstinence following hospital discharge?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial involving 353 adults with severe mental illness who reported smoking cigarettes, a sustained care smoking cessation intervention yielded greater treatment engagement and abstinence at 6 months following discharge than usual care.

Meaning

In this study, intervening during the psychiatric hospital stay using a patient-centered approach was effective at continuing the move toward smoking abstinence initiated during the hospital stay.

This randomized clinical trial examines the effectiveness of a multicomponent, sustained care smoking cessation intervention vs usual care for smoking abstinence in adults with serious mental illness during and after inpatient care.

Abstract

Importance

Smoking among individuals with serious mental illness (SMI) represents a major public health problem. Intervening during a psychiatric hospital stay may provide an opportunity to aid engagement in smoking cessation treatment and facilitate success in quitting.

Objective

To examine the effectiveness of a multicomponent, sustained care (SusC) smoking cessation intervention in adults with SMI receiving inpatient psychiatric care.

Design, Setting, and Participants

The Helping HAND 3 randomized clinical trial compared SusC with usual care (UC) among individuals with SMI who smoked daily and were receiving inpatient psychiatric care in Austin, Texas, in a single hospital. The study was conducted from July 2015 through August 2019.

Interventions

The UC intervention involved brief smoking cessation information, self-help materials and advice from the admitting nurse, and an offer to provide nicotine replacement therapy during hospitalization. The SusC intervention included 4 main components designed to facilitate patient engagement with postdischarge smoking cessation resources: (1) inpatient motivational counseling; (2) free transdermal nicotine patches on discharge; (3) an offer of free postdischarge telephone quitline, text-based, and/or web-based smoking cessation counseling, and (4) postdischarge automated interactive voice response calls or text messages.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was biochemically verified 7-day point-prevalence abstinence at 6-month follow-up. A secondary outcome was self-reported smoking cessation treatment use at 1, 3, and 6 months after discharge.

Results

A total of 353 participants were randomized, of whom 342 were included in analyses (mean [SD] age, 35.8 [12.3] years; 268 White individuals [78.4%]; 280 non-Hispanic individuals [81.9%]; 169 women [49.4%]). They reported smoking a mean (SD) of 16.9 (10.4) cigarettes per day. Participants in the SusC group evidenced significantly higher 6-month follow-up point-prevalence abstinence rates than those in the UC group (8.9% vs 3.5%; adjusted odds ratio, 2.95 [95% CI, 1.24-6.99]; P = .01). The number needed to treat was 18.5 (95% CI, 9.6-306.4). A series of sensitivity analyses confirmed effectiveness. Finally, participants in the SusC group were significantly more likely to report using smoking cessation treatment over the 6 months postdischarge compared with participants in the UC group (74.6% vs 40.5%; relative risk, 1.8 [95% CI, 1.51-2.25]; P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

The findings of this randomized clinical trial provide evidence for the effectiveness of a scalable, multicomponent intervention in promoting smoking cessation treatment use and smoking abstinence in individuals with SMI following hospital discharge.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02204956

Introduction

Individuals with serious mental illness (SMI)1 smoke cigarettes at disproportionately higher rates,2 are more likely to smoke heavily,3 and have lower cessation rates4,5,6 than the general population. Adults with SMI who smoke cigarettes consume almost half (44.3%) of all cigarettes smoked in the US7 and have lifespans 25 to 32 years shorter than the general population.8,9 Cigarette smoking has been identified as an important modifiable risk factor for excess mortality in people with SMI.10

In 2017, 3.3% of US adults, or almost 11 million adults, received inpatient psychiatric treatment in the past year.11 Traditionally, psychiatrists and mental health professionals have been reluctant to address cigarette smoking in their patients because of beliefs that patients are not interested in quitting smoking or concerns about the negative effects of quitting smoking on psychiatric state or recovery.12 However, there is growing evidence that smoking cessation may serve to improve psychiatric symptoms over the long term.13 Furthermore, adults with SMI who smoke cigarettes want to quit smoking14 and will accept smoking cessation treatment with assistance and encouragement.15,16,17,18 Psychiatric hospitalization itself has been found to increase self-efficacy and motivation to quit smoking.19,20

While patients may be offered nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) and other medications to ease withdrawal during hospitalization, they are rarely offered quit-smoking referrals or provided with NRT on discharge,21,22,23 and most resume smoking after leaving the hospital.14 Because no tobacco use is allowed on psychiatric hospital units, the inpatient setting offers a unique opportunity to initiate smoking cessation by capitalizing on abstinence already achieved during hospitalization.21 Integration of effective smoking cessation interventions into psychiatric hospitals is a public health priority,24,25 accompanied by an important research agenda.26 As with our 2 prior Helping HAND (Hospital-Initiated Assistance for Nicotine Dependence) trials with adults who were medically hospitalized and smoked,27,28 the current trial aimed to capitalize on this largely underused teachable moment by framing a cessation effort as a continuation of what has already begun (ie, a continued move toward total smoking abstinence).

The overall objective of the Helping HAND 3 trial29 was to examine the effectiveness of a multicomponent, sustained care (SusC) smoking cessation intervention in smokers with SMI receiving inpatient psychiatric care. We hypothesized that (1) SusC compared with usual care (UC) would result in significantly higher rates of validated, 7-day point-prevalence abstinence (PPA) from tobacco at 6-month follow-up, and (2) a higher proportion of patients in the SusC vs the UC group would use evidence-based smoking cessation treatment in the months after hospital discharge. If effective, the adapted sustained care model could be broadly disseminated to reduce tobacco use in this vulnerable population of individuals with psychiatric disorders who smoke.

Methods

Design

Participants were adults who smoked cigarettes and were engaged in treatment at a freestanding, acute-care, private psychiatric hospital in Austin, Texas, who provided written informed consent before random assignment by cohort to a sustained care (SusC) smoking cessation intervention or a usual care (UC) intervention. Biochemically verified smoking status was assessed at 6 months, and use of smoking cessation treatment was assessed at 1, 3, and 6 months after hospital discharge. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Texas at Austin and funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (grant R01MH104562). The trial was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier NCT02204956). Reporting of the trial follows the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline.30 We provide the trial protocol in Supplement 1 and have described the methods elsewhere.29

Participants

Participants were adults ages 18 years or older who smoked at least 5 cigarettes per day when not hospitalized. Exclusion criteria included (1) a current diagnosis of dementia or other cognitive impairment, (2) a Mini-Mental State Examination31 score less than 24, (3) an inability to provide consent for study participation, (4) a diagnosis of intellectual disability or autistic spectrum disorder, (5) a current diagnosis of a nonnicotine substance use disorder requiring detoxification, (6) the inability to communicate by telephone, (7) a planned discharge to institutional care, (8) a lack of a current or stable mailing address, (9) medical contraindication to the use of NRT (eg, angina, a recent myocardial infarction), or (10) a current pregnancy, current breastfeeding, or a plan to become pregnant within 6 months.

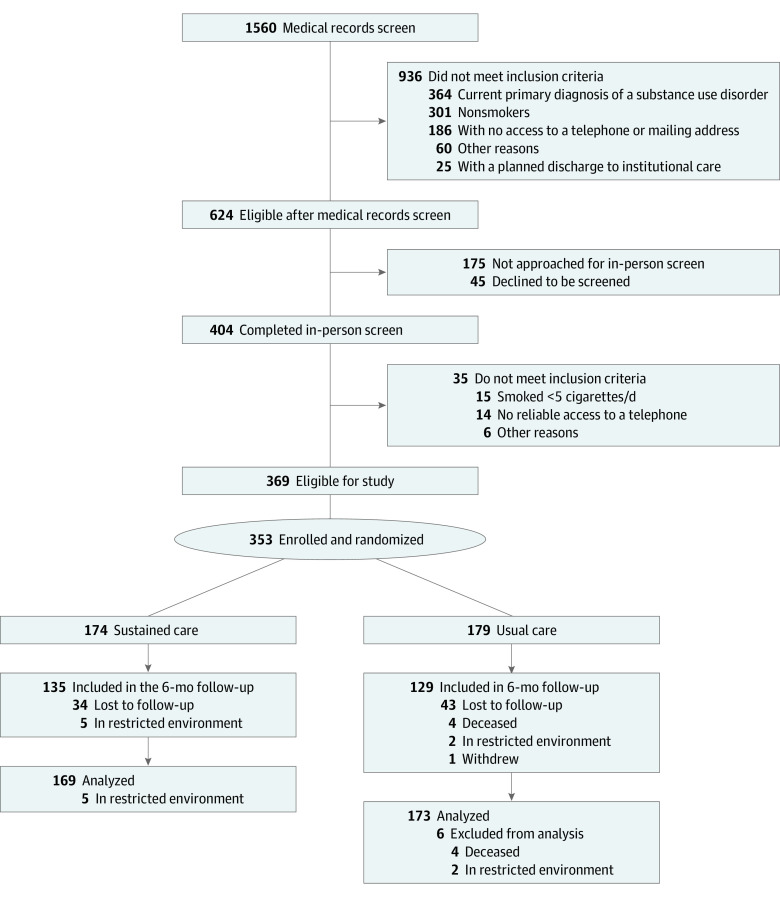

Procedures

The Figure depicts participant flow. Recruitment took place between July 2015 and January 2019, and follow-up data were collected through August 2019. Participants were recruited from 2 hospital units that treat adult patients with SMI. One unit (16 beds) primarily treats mood, anxiety, and personality disorders; the other unit (24 beds) provides specialized treatment for thought disorders and more severe mood disorders. Units providing intensive care to patients with acute psychiatric symptoms and those providing substance use detoxification protocols were excluded. The hospital provides intensive psychiatric stabilization for adult patients and facilitates a wide range of support groups that meet on a regular basis. Licensed psychiatric staff are on call 24 hours per day to address the mental health needs of patients and their families. No smoking, tobacco use, or e-cigarette use is allowed in the hospital or on hospital grounds.

Figure. CONSORT Diagram.

Randomization was based on the hospital unit; 9 cohorts on each hospital unit (18 in all) were randomly assigned to either SusC or UC in a yoked manner, such that a randomized cohort on each unit was followed by the opposite condition on that unit. Participants were compensated up to $125 for completing measures at baseline and 1, 3, and 6 months following discharge. Participants reporting smoking abstinence were compensated with an additional $40 if they provided biochemical verification.

Interventions

UC

Participants assigned to the UC condition received usual hospital care. This consisted of brief (5-minute to 10-minute) smoking cessation information and advice from their admitting nurse, self-help materials, and an offer of NRT to use during their hospitalization.

SusC

Participants assigned to the SusC condition, previously described in more detail,29 received the same, usual hospital care provided to participants in the UC group, but in addition, they received a 40-minute, motivational interviewing–based32 counseling session, with specific adaptations tailored for patients with SMI.29 Hospital-based, master’s-level social workers served as smoking cessation counselors and followed a written protocol, which was not part of routine hospital care. Two authors (R.A.B. and J.H.) provided initial training in tobacco cessation counseling and motivational interviewing and offered ongoing supervision.

At the end of the in-hospital motivational counseling session, participants were offered access to free telephone, text-based, and/or web-based cessation counseling offered by a quitline service provider, Optum. If participants accepted the offer, study staff enrolled them via a web portal set up specifically for this study. Participants enrolled in quitline counseling received a telephone counseling protocol of up to 5 proactive calls over 3 months, with unlimited inbound calls. Quitline counselors received specialized training on how to address tobacco cessation for callers with mental health issues33 and followed a protocol for addressing suicidal ideation if reported by callers.

On discharge, patients received 4 weeks of free transdermal nicotine patches and were enrolled in an automated, proactive interactive voice response (IVR) telephone system. Prerecorded messages and interactive questions, received either via telephone or text message, asked about participants’ smoking, intentions to quit, desire for an additional 4 weeks of transdermal nicotine patches (ie, 8 weeks total), and interest in connecting with free telephone quitline, text-based, and/or web-based cessation counseling. If participants did not accept the offer of telephone quitline, web-based, and/or text-based cessation counseling following the in-hospital counseling session, they could still access these services by responding affirmatively to the IVR prompts received following hospitalization. Participants received these IVR contacts, provided by TelASK Technologies, at 8 predetermined times over the course of 12 weeks posthospital discharge.

Measures

Participants completed self-report measures, including demographics, smoking history, Fagerström Test for Cigarette Dependence,34 Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Emotional Distress-Anxiety–Short Form 8a and Emotional Distress-Depression–Short Form 8a,35,36 and the 4-item psychotic subscale and 3-item emotional liability subscale of the Behavior and Symptoms Identification Scale–24.37 Alcohol and drug use quantity and frequency were assessed, consistent with prior tobacco research.38 Primary and secondary discharge diagnoses, length of stay, type of insurance, discharge medications, and readmissions to the hospital were abstracted from the participant’s medical record.

The primary outcome was self-reported smoking abstinence for the past 7 days (7-day PPA), verified at 6 months by saliva cotinine analysis (cutoff, ≤15 ng/mL).39 Since use of nicotine products produces a false-positive result on cotinine testing, expired carbon monoxide (cutoff, ≤8 ppm)39 was substituted for cotinine for those who reported nonsmoking during the past 7 days while using NRT. In instances in which we were unable to obtain biochemical verification of nonsmoking, a brief, structured interview with participants’ significant other was conducted, which included asking if the participant smoked in the 7 days prior to their 6-month follow-up assessment.40,41,42,43,44 At each follow-up, participants reported on their use of smoking counseling (telephone, in-person, web-based, and/or text-based counseling from any source) and/or pharmacotherapy, including use of NRT (nicotine patch, gum, lozenge, inhaler, or nasal spray), bupropion, or varenicline.

Statistical Analysis

We compared 6-month abstinence rates between groups using a generalized linear model with cohort-clustered SE, since the intervention was assigned at the cohort level, rather than the individual level.45 Analyses were conducted in R version 4.0.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) using a clustered generalized linear model with a binomial family distribution and logit link function. We had proposed to collect smoking outcomes at 6-month and 12-month follow-ups and use generalized estimating equation to analyze these longitudinal smoking outcomes. However, guided by the 6-month follow-up primary outcome standard adopted by the National Institutes of Health–funded Consortium of Hospitals Advancing Research on Tobacco,46 we dropped the 12-month follow-up assessment and thus selected a generalized linear model approach instead, which is appropriate for cross-sectional data.47 As per a prespecified protocol,29 the primary outcome was biochemically verified 7-day PPA at the 6-month follow-up, with missing smoking status or self-reported abstinence that was not biochemically verified coded as smoking. We included sex and baseline cigarette dependence (Fagerström Test for Cigarette Dependence score) as covariates in the model as per study protocol. Odds ratios, adjusted odds ratios (AORs), and the number needed to treat (NNT) were also calculated. A series of sensitivity analyses were conducted using an alternative coding for missing data, a secondary definition of the smoking outcome, additional covariates, and no covariates in the primary outcome model. The targeted sample size was set at 398 to detect a 10% between-group difference (20% in SusC vs 10% in UC) at the 6-month follow-up, with power at 80% and an α of .05.

Differential rates of self-reported smoking cessation treatment use (ie, counseling and pharmacotherapy) at 1, 3, and 6 months after discharge were calculated using relative risks (RRs). Missing data were coded as indicating no treatment. To test the robustness of our findings, we also conducted 4 sensitivity analyses using the same generalized linear model approach but with different assumptions or conditions: (1) missing data regarded as missing data,48 as opposed to missing data regarded as smoking; (2) PPA coded as abstinence if self-reported abstinence was biochemically verified or verified by a significant other; (3) inclusion of unit (which was associated with missingness) as a covariate; and (4) removal of all covariates.

Results

A total of 353 participants were randomized to SusC (n = 174) or UC (n = 179). For the outcome analyses, we excluded 11 participants who died (n = 4) or were in a restricted environment (ie, jail or an inpatient unit; n = 7) at the time of 6-month follow-up. The lower sample size (n = 342; mean [SD] age, 35.8 [12.3] years; 268 White individuals [78.4%]; 280 non-Hispanic individuals [81.9%]; 169 women [49.4%]) reduced statistical power to 74%. Demographic and baseline characteristics by condition are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Sample Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Care group, No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sustained (n = 169) | Usual (n = 173) | |

| Female | 79 (46.7) | 90 (52.0) |

| Male | 90 (53.3) | 83 (48.0) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 30 (17.8) | 32 (18.5) |

| Race | ||

| White | 128 (75.7) | 140 (80.9) |

| Black or African American | 26 (15.4) | 19 (11.0) |

| Asian | 3 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| More than 1 race | 11 (6.5) | 13 (7.5) |

| Choose not to answer | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) |

| Highest level of education | ||

| 4-y College or more | 34 (20.1) | 37 (21.4) |

| Some college | 75 (44.4) | 67 (38.7) |

| High school graduate or GED | 36 (21.3) | 46 (26.6) |

| Less than high school | 24 (14.2) | 20 (11.6) |

| Household income, $ | ||

| 0-24 999 | 113 (66.9) | 119 (68.8) |

| 25 000-49 999 | 20 (11.8) | 28 (16.2) |

| 50 000-74 999 | 12 (7.1) | 12 (6.9) |

| 75 000-99 999 | 6 (3.6) | 5 (2.9) |

| ≥100 000 | 17 (10.1) | 4 (2.3) |

| Employment status | ||

| Full-time | 45 (26.6) | 41 (23.7) |

| Part-time | 19 (11.2) | 20 (11.6) |

| Retired | 3 (1.8) | 5 (2.9) |

| Disabled | 41 (24.3) | 43 (24.9) |

| Unemployed | 61 (36.1) | 63 (36.4) |

| Discharge diagnosis | ||

| Disorders | ||

| Depressive | 83 (49.1) | 84 (48.6) |

| Anxiety | 19 (11.2) | 15 (8.7) |

| Bipolar and associated | 48 (28.4) | 54 (31.2) |

| Trauma-associated and stressor-associated | 15 (8.9) | 16 (9.2) |

| Schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic | 31 (18.3) | 37 (21.4) |

| Obsessive-compulsive and associated | 2 (1.2) | 2 (1.2) |

| Disruptive, impulse control, and conduct | 1 (0.6) | 4 (2.3) |

| Substance-associated and addictive | 65 (38.5) | 75 (43.4) |

| Personality | 25 (14.8) | 23 (13.3) |

| Neurocognitive disorder due to another medical condition | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) |

| Eating | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) |

| Neurodevelopmental | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) |

| Somatic symptom and associated | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) |

| Substance use in the past 30 d | ||

| Daily use of alcohol | 7 (4.1) | 10 (5.8) |

| Marijuana every day or nearly every day | 29 (17.2) | 30 (17.3) |

| Drugs every day or nearly every day | 5 (3.0) | 8 (4.6) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 36.1 (12.4) | 35.5 (12.2) |

| Past serious attempts at quitting, No. | 3.0 (2.4) | 3.0 (2.5) |

| Past attempts at quitting >24 h, No. | 3.0 (3.2) | 3.9 (15.2) |

| Longest attempt at quitting, d | 455.0 (813.8) | 500.5 (1107.8) |

| Fagerström Test for Cigarette Dependence scorea | 4.7 (2.2) | 4.6 (2.6) |

| Cigarettes/d prehospitalization | 17.0 (8.8) | 16.8 (11.7) |

| Readiness to quit smoking in the next 30 d | 6.6 (2.6) | 5.6 (3.0) |

| Depressive symptoms per PROMIS-D8aa | 18.9 (8.1) | 19.0 (7.9) |

| Anxiety symptoms per PROMIS-A8aa | 19.4 (7.7) | 20.0 (6.8) |

| Psychotic symptoms per BASIS-24a | 3.7 (4.2) | 3.6 (3.8) |

| Emotional lability per BASIS-24a | 6.4 (2.7) | 6.7 (2.6) |

| Length of hospital stay, median (IQR), d | 6 (4-8) | 6 (4-8) |

| Discharge diagnoses, median (IQR), No. | 2 (1-2) | 2 (1-2) |

Abbreviations: BASIS-24, the Behavior and Symptoms Identification Scale-24; IQR, interquartile range; PROMIS, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System.

Rates of missing data at the 6-month follow-up did not differ significantly between groups (SusC, 34 of 169 [20.1%] vs UC, 44 of 173 [25.4%]; P = .30), but missingness was associated with the hospital unit (43 of 145 [29.7%] vs 35 of 197 [17.8%]; P = .01), with higher rates of missing data for the unit treating patients with thought disorders and more severe mood disorders. No other baseline characteristics were associated with missingness. Of those who reported abstinence at 6-month follow-up, biochemical verification of self-reported abstinence was obtained for 15 of 48 individuals (31.3%) in the SusC group and 6 of 24 individuals (25%) in the UC group; these rates did not differ significantly between groups.

Effectiveness

As can be seen in Table 2, significantly higher rates of PPA were observed in the SusC group compared with the UC group at 6-month follow-up (8.9% vs 3.5%; AOR, 2.95 [95% CI, 1.24-6.99]; P = .01). The NNT was 18.5 (95% CI, 9.6-306.4).

Table 2. Smoking Abstinence Rates at 6-Month Follow-up by Treatment Conditiona.

| 7-d Point-prevalence abstinence | Care group, No. (%) | Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sustained | Usual | ||

| Missing equated to smoking | |||

| No. | 169 | 173 | NA |

| Biochemically verified | 15 (8.9) | 6 (3.5) | 2.95 (1.24-6.99) |

| Biochemically verified or verified by significant other | 32 (18.9) | 17 (9.8) | 2.22 (1.14-4.31) |

| Missing regarded as missing (available data only) | |||

| No. | 135 | 129 | NA |

| Biochemically verified | 15 (11.1) | 6 (4.7) | 2.75 (1.11-6.84) |

| Biochemically verified or verified by significant other | 32 (23.7) | 17 (13.2) | 2.08 (1.05-4.10) |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

From a generalized linear model with cohort-clustered standard error, controlling for sex and nicotine dependence.

Sensitivity Analyses

The findings of sensitivity analyses are presented in Table 2. The first sensitivity analysis was conducted using only available data (n = 264 [77.2%]). Results from this analysis were unchanged from the primary outcome analysis: significantly higher rates of biochemically verified PPA at the 6-month follow-up were observed in participants in the SusC group compared with participants in the UC group (11.1% vs 4.7%; AOR, 2.75 [95% CI, 1.11-6.84]; P = .03). The NNT was 15.5 (95% CI, 7.8-3066.4).

The second set of sensitivity analyses modeled a secondary smoking outcome, PPA biochemically verified or verified by a significant other, as per study protocol.29 We ran this model twice with missing data coded as smoking or missing (ie, using only available data). Results from both models remained unchanged from the primary outcome analysis: significantly higher rates of PPA were observed in participants in the SusC group compared the participants in the UC group (model 1: 18.9% vs 9.8%; AOR, 2.22 [95% CI, 1.14-4.31]; P = .02; model 2: 23.7% vs 13.2%; AOR, 2.08 [95% CI, 1.05-4.10]; P = .04, respectively). The NNT was 11.0 (95% CI, 6.1-58.1) and 9.5 (95% CI, 5.1-78.3), respectively.

The third sensitivity analysis included inpatient unit as an additional covariate in the primary outcome analysis, given that the unit was associated with missingness at 6-month follow-up. Including unit as a covariate (in addition to the planned covariates of sex and baseline cigarette dependence) in the primary outcome analysis did not change the findings; significantly higher rates of PPA were observed in participants in the SusC group compared with participants in the UC group (AOR, 2.95 [95% CI, 1.26-6.91]; P = .01).

The final set of sensitivity analyses was conducted without any covariates in the primary outcome model, using 2 different coding approaches for missing data (ie, coding missing data as smoking or missing). Excluding covariates from the primary outcome analysis did not change the significance of the findings, whether missing data were coded as smoking (AOR, 2.71 [95% CI, 1.11-6.60]; P = .03) or analysis used only available data (AOR, 2.56 [95% CI, 1.04-6.34]; P = .04).

These sensitivity analyses demonstrated that the results from the primary outcome analysis, indicating the efficacy of SusC over UC, are robust across different specifications. This can increase confidence in the findings.

Treatment Engagement

Use of smoking cessation treatment assessed at 1, 3, and 6 months after discharge is presented in Table 3. Compared with UC, participants in the SusC group were significantly more likely to report having used any smoking cessation treatment over the 6 months (cumulative) after hospital discharge (74.6% vs 40.5%; RR, 1.8 [95% CI, 1.51-2.25]; P < .001), including both counseling (37.3% vs 11.1%; RR, 3.39 [95% CI, 2.13-5.42]; P < .001) and pharmacotherapy (71.0% vs 37.0%; RR, 1.92 [95% CI, 1.54-2.38]; P < .001). Excluding missing data from the analysis did not change the significance of the overall findings.

Table 3. Use of Smoking Cessation Treatment After Hospital Discharge by Treatment Condition.

| Outcome measure reported at follow-up | Care type, No. (%) | Relative risk (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sustained (n = 169) | Usual (n = 173) | ||

| Any smoking cessation treatment use | |||

| 1 mo | 102 (60.4) | 35 (20.2) | 2.98 (2.17-4.11) |

| 3 mo (Cumulative) | 118 (69.8) | 57 (32.9) | 2.12 (1.68-2.68) |

| 6 mo (Cumulative) | 126 (74.6) | 70 (40.5) | 1.84 (1.51-2.25) |

| Smoking cessation counseling use | |||

| 1 mo | 36 (21.3) | 8 (4.6) | 4.61 (2.21-9.62) |

| 3 mo (Cumulative) | 53 (31.4) | 16 (9.2) | 3.39 (2.02-5.69) |

| 6 mo (Cumulative) | 63 (37.3) | 19 (11.0) | 3.39 (2.13-5.42) |

| Smoking cessation medication use | |||

| 1 mo | 99 (58.6) | 31 (17.9) | 3.27 (2.32-4.61) |

| 3 mo (Cumulative) | 112 (66.3) | 52 (30.0) | 2.20 (1.71-2.84) |

| 6 mo (Cumulative) | 120 (71.0) | 64 (37.0) | 1.92 (1.54-2.38) |

Discussion

The current Helping HAND 3 trial demonstrated the efficacy of a hospital-based, sustained care model for tobacco cessation, adapted for smokers receiving inpatient psychiatric treatment, in promoting long-term tobacco cessation. Long-term abstinence rates in the SusC group were about double that observed in the UC group across conservative (biochemically verified and counting missing as smoking; 8.9% vs 3.5%; NNT, 18.5) and more liberal definitions of abstinence (biochemically verified or significant other–verified and counting missing data as missing data; 23.7% vs 13.2%; NNT, 9.5). These findings are notable, given that two-thirds of this sample could be considered economically disadvantaged (with household annual incomes less than $25 000), in addition to having SMI. Both of these factors are associated with higher smoking rates2,49 and less success at quitting.4,5,6,49 Patients receiving SusC vs UC while in the hospital were also more likely to have used any tobacco cessation treatment (including both counseling [SusC, 37.3% vs UC, 11.1%] and pharmacotherapy [SusC, 71.0% vs UC, 37.0%]) over the 6 months after hospital discharge. The difference between the rates of treatment use and successful cessation may be because of underuse of pharmacotherapies (ie, not using as much as or for as long as recommended) and serve to highlight the difficulty of quitting among this population.

The aim of the SusC intervention was to have patients build on the abstinence already attained during hospitalization by enhancing motivation to remain abstinent and providing ready access to tobacco cessation resources after hospital discharge. Although the SusC intervention offered to patients hospitalized with SMI was adapted from a similar intervention that had been established with adults in a general medical inpatient unit who smoked, there were several significant differences in patient eligibility and in the intervention itself. In the original Helping HAND trials,27,28 patients were eligible if they received smoking cessation counseling while in the hospital (which was routinely offered) and discharged were planning to try to quit and were willing to accept smoking cessation pharmacotherapy. In the current trial, only brief advice to quit was routinely offered to patients during their hospitalization and no level of motivation to quit smoking or willingness to accept smoking cessation pharmacotherapy on discharge was required. A primary component of the SusC model in this study was the use of motivational interviewing with patients to promote continued abstinence and acceptance of smoking cessation resources offered (tobacco quitline counseling and transdermal nicotine patches) on hospital discharge.

Our findings suggest that combining this evidenced-based, client-centered counseling approach32 with automated, proactive resources, such as IVR, text messaging, and other technology-assisted interventions, which have been found to aid behavior change following hospital discharge,28,50 increases the likelihood of successful attempts at quitting. Other investigators have demonstrated efficacy for smoking cessation in similar hospitalized populations using various differing intervention components.51,52 Follow-up research aimed at disentangling effective components of these interventions can aid the goal of establishing an optimized, efficient, and effective intervention for smokers hospitalized with psychiatric disorders.53,54 Also, future research should examine potential differential treatment effects across race/ethnicity and diagnoses.

Strengths

The present study has several strengths. These include the sample size, the focus on SMI, the hospital-based delivery, and the use of a randomized clinical trial design with a relevant control condition.

Limitations

Limitations of the investigation include the sample composition (limited racial/ethnic diversity and exclusion of those without a stable address), the single site location of the study, and loss of participants to follow-up and challenges in obtaining biochemical verification. The first 2 limited generalizability, while the third compromised the accuracy of estimates of abstinence rates. An additional limitation is our inability to disentangle the contribution of the individual treatment components to overall abstinence outcomes.

Conclusions

The findings of this randomized clinical trial support the effectiveness of a brief, multicomponent intervention for promoting the use of smoking cessation medication and counseling treatment and ultimately abstinence following hospital discharge. These findings, if replicated, provide a scalable approach to achieving sustained smoking cessation in patients with SMI following a psychiatric hospital stay.

Trial Protocol.

Data Sharing Statement.

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . The way forward: federal action for a system that works for all people living with SMI and SED and their families and caregivers. Published 2017. Accessed March 26, 2021. https://store.samhsa.gov/product/The-Way-Forward-Federal-Action-for-a-System-That-Works-for-All-People-Living-With-SMI-and-SED-and-Their-Families-and-Caregivers-Full-Report/PEP17-ISMICC-RTC

- 2.Cook BL, Wayne GF, Kafali EN, Liu Z, Shu C, Flores M. Trends in smoking among adults with mental illness and association between mental health treatment and smoking cessation. JAMA. 2014;311(2):172-182. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glasheen C, Hedden SL, Forman-Hoffman VL, Colpe LJ. Cigarette smoking behaviors among adults with serious mental illness in a nationally representative sample. Ann Epidemiol. 2014;24(10):776-780. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2014.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Streck JM, Weinberger AH, Pacek LR, Gbedemah M, Goodwin RD. Cigarette smoking quit rates among persons with serious psychological distress in the United States from 2008-2016: are mental health disparities in cigarette use increasing? Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22(1):130-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith PH, Mazure CM, McKee SA. Smoking and mental illness in the U.S. population. Tob Control. 2014;23(e2):e147-e153. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalkhoran S, Thorndike AN, Rigotti NA, Fung V, Baggett TP. Cigarette smoking and quitting-related factors among US adult health center patients with serious mental illness. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(6):986-991. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-04857-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lasser K, Boyd JW, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, McCormick D, Bor DH. Smoking and mental illness: a population-based prevalence study. JAMA. 2000;284(20):2606-2610. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.20.2606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parks J, Svendsen D, Singer P, Foti ME, eds. National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors. Morbidity and mortality in people with serious mental illness: 13th technical report. Published 2006. Accessed March 26, 2021. https://www.nasmhpd.org/content/morbidity-and-mortality-people-serious-mental-illness

- 9.Goff DC, Cather C, Evins AE, et al. Medical morbidity and mortality in schizophrenia: guidelines for psychiatrists. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(2):183-194. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v66n0205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown S, Inskip H, Barraclough B. Causes of the excess mortality of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:212-217. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.3.212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Results from the 2011 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Mental Health Findings. Substance Aubse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheals K, Tombor I, McNeill A, Shahab L. A mixed-method systematic review and meta-analysis of mental health professionals’ attitudes toward smoking and smoking cessation among people with mental illnesses. Addiction. 2016;111(9):1536-1553. doi: 10.1111/add.13387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor G, McNeill A, Girling A, Farley A, Lindson-Hawley N, Aveyard P. Change in mental health after smoking cessation: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2014;348:g1151. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prochaska JJ, Fletcher L, Hall SE, Hall SM. Return to smoking following a smoke-free psychiatric hospitalization. Am J Addict. 2006;15(1):15-22. doi: 10.1080/10550490500419011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prochaska JJ, Rossi JS, Redding CA, et al. Depressed smokers and stage of change: implications for treatment interventions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;76(2):143-151. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evins AE, Cather C, Deckersbach T, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled trial of bupropion sustained-release for smoking cessation in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;25(3):218-225. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000162802.54076.18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Acton GS, Prochaska JJ, Kaplan AS, Small T, Hall SM. Depression and stages of change for smoking in psychiatric outpatients. Addict Behav. 2001;26(5):621-631. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4603(01)00178-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haug NA, Hall SM, Prochaska JJ, et al. Acceptance of nicotine dependence treatment among currently depressed smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2005;7(2):217-224. doi: 10.1080/14622200500055368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shmueli D, Fletcher L, Hall SE, Hall SM, Prochaska JJ. Changes in psychiatric patients’ thoughts about quitting smoking during a smoke-free hospitalization. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(5):875-881. doi: 10.1080/14622200802027198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dohnke B, Ziemann C, Will KE, Weiss-Gerlach E, Spies CD. Do hospital treatments represent a ‘teachable moment’ for quitting smoking? a study from a stage-theoretical perspective. Psychol Health. 2012;27(11):1291-1307. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2012.672649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prochaska JJ, Gill P, Hall SM. Treatment of tobacco use in an inpatient psychiatric setting. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(11):1265-1270. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.11.1265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thorndike AN, Stafford RS, Rigotti NA. US physicians’ treatment of smoking in outpatients with psychiatric diagnoses. Nicotine Tob Res. 2001;3(1):85-91. doi: 10.1080/14622200020032132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ortiz G, Schacht L, Lane GM. Smoking cessation care in state-operated or state-supported psychiatric hospitals: from policy to practice. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(7):666-671. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ziedonis D, Hitsman B, Beckham JC, et al. Tobacco use and cessation in psychiatric disorders: National Institute of Mental Health report. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(12):1691-1715. doi: 10.1080/14622200802443569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Vital signs: current cigarette smoking among adults aged ≥18 years with mental illness—United States, 2009-2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(5):81-87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kagabo R, Gordon AJ, Okuyemi K. Smoking cessation in inpatient psychiatry treatment facilities: a review. Addict Behav Rep. 2020;11:100255. doi: 10.1016/j.abrep.2020.100255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rigotti NA, Regan S, Levy DE, et al. Sustained care intervention and postdischarge smoking cessation among hospitalized adults: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312(7):719-728. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.9237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rigotti NA, Tindle HA, Regan S, et al. A post-discharge smoking-cessation intervention for hospital patients: Helping HAND 2 randomized clinical trial. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51(4):597-608. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hecht J, Rigotti NA, Minami H, et al. Adaptation of a sustained care cessation intervention for smokers hospitalized for psychiatric disorders: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2019;83:18-26. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2019.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D; CONSORT Group . CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Trials. 2010;11:32. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-11-32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Folstein MF, Robins LN, Helzer JE. The Mini-Mental State Examination. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1983;40(7):812. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790060110016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. 3rd ed. The Guildford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 33.North American Quitline Consortium . Results from the 2012 NAQC annual survey of quitlines. Published 2013. Accessed March 26, 2021. https://www.naquitline.org/page/2012Survey

- 34.Fagerström K. Determinants of tobacco use and renaming the FTND to the Fagerstrom Test for Cigarette Dependence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14(1):75-78. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pilkonis PA, Choi SW, Salsman JM, et al. Assessment of self-reported negative affect in the NIH toolbox. Psychiatry Res. 2013;206(1):88-97. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.09.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pilkonis PA, Choi SW, Reise SP, Stover AM, Riley WT, Cella D; PROMIS Cooperative Group . Item banks for measuring emotional distress from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®): depression, anxiety, and anger. Assessment. 2011;18(3):263-283. doi: 10.1177/1073191111411667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cameron IM, Cunningham L, Crawford JR, et al. Psychometric properties of the BASIS-24© (Behaviour and Symptom Identification Scale–Revised) mental health outcome measure. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2007;11(1):36-43. doi: 10.1080/13651500600885531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clark MA, Rogers ML, Boergers J, et al. A transdisciplinary approach to protocol development for tobacco control research: a case study. Transl Behav Med. 2012;2(4):431-440. doi: 10.1007/s13142-012-0164-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.SRNT Subcommittee on Biochemical Verification . Biochemical verification of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2002;4(2):149-159. doi: 10.1080/14622200210123581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simon JA, Carmody TP, Hudes ES, Snyder E, Murray J. Intensive smoking cessation counseling versus minimal counseling among hospitalized smokers treated with transdermal nicotine replacement: a randomized trial. Am J Med. 2003;114(7):555-562. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(03)00081-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taylor CB, Houston-Miller N, Killen JD, DeBusk RF. Smoking cessation after acute myocardial infarction: effects of a nurse-managed intervention. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(2):118-123. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-2-118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miller NH, Smith PM, DeBusk RF, Sobel DS, Taylor CB. Smoking cessation in hospitalized patients: results of a randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(4):409-415. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1997.00440250059007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dornelas EA, Sampson RA, Gray JF, Waters D, Thompson PD. A randomized controlled trial of smoking cessation counseling after myocardial infarction. Prev Med. 2000;30(4):261-268. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sivarajan Froelicher ES, Miller NH, Christopherson DJ, et al. High rates of sustained smoking cessation in women hospitalized with cardiovascular disease: the Women’s Initiative for Nonsmoking (WINS). Circulation. 2004;109(5):587-593. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000115310.36419.9E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abadie A, Athey S, Imbens G, Wooldridge J. When should you adjust standard errors for clustering? Published October 2017. Accessed March 26, 2021. https://arxiv.org/abs/1710.02926

- 46.Riley WT, Stevens VJ, Zhu SH, Morgan G, Grossman D. Overview of the consortium of hospitals advancing research on tobacco (CHART). Trials. 2012;13:122. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-13-122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aktas Samur A, Coskunfirat N, Saka O. Comparison of predictor approaches for longitudinal binary outcomes: application to anesthesiology data. PeerJ. 2014;2:e648. doi: 10.7717/peerj.648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Blankers M, Smit ES, van der Pol P, de Vries H, Hoving C, van Laar M. The missing=smoking assumption: a fallacy in internet-based smoking cessation trials? Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(1):25-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hiscock R, Bauld L, Amos A, Fidler JA, Munafò M. Socioeconomic status and smoking: a review. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1248:107-123. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06202.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reid RD, Mullen KA, Slovinec D’Angelo ME, et al. Smoking cessation for hospitalized smokers: an evaluation of the “Ottawa Model”. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(1):11-18. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Prochaska JJ, Hall SE, Delucchi K, Hall SM. Efficacy of initiating tobacco dependence treatment in inpatient psychiatry: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(8):1557-1565. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Metse AP, Wiggers J, Wye P, et al. Efficacy of a universal smoking cessation intervention initiated in inpatient psychiatry and continued post-discharge: a randomised controlled trial. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2017;51(4):366-381. doi: 10.1177/0004867417692424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Collins LM, Murphy SA, Strecher V. The multiphase optimization strategy (MOST) and the sequential multiple assignment randomized trial (SMART): new methods for more potent eHealth interventions. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(5)(suppl):S112-S118. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.01.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Collins LM. Optimization of Behavioral, Biobehavioral, and Biomedical Interventions: The Multiphase Optimization Strategy (MOST). Springer; 2018. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol.

Data Sharing Statement.