Abstract

A parallel screening method has been developed to rapidly evaluate discrete library substrates of biomaterials using cell-based assays. The biomaterials used in these studies were surface-erodible polyanhydrides based on sebacic acid (SA), 1,6-bis(p-carboxyphenoxy)hexane (CPH), and 1,8-bis(p-carboxyphenoxy)-3,6-dioxaoctane (CPTEG) that have been previously studied as carriers for drugs, proteins, and vaccines. Linearly varying compositional libraries of 25 different polyanhydride random copolymers (based on CPH:SA and CPTEG:CPH) were designed, fabricated, and synthesized using discrete (organic solvent-resistant) multi-sample substrates created using a novel rapid prototyping method. The combinatorial libraries were characterized at high throughput using infrared microscopy and validated using 1H NMR and size exclusion chromatography. The discrete libraries were rapidly screened for biocompatibility using standard SP2/0 myeloma, CHO and L929 fibroblasts, and J774 macrophage cell lines. At a concentration of 2.8 mg/mL, there was no appreciable cytotoxic effect on any of the four cell lines evaluated by any of the CPH:SA or CPTEG:CPH compositions. Furthermore, the activation of J774 macrophages was evaluated by incubating the cells with the polyanhydride libraries and quantifying the secreted cytokines (IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, and TNFα). The results indicated that copolymer compositions containing at least 50% CPH induced elevated amounts of TNFα. In summary, the results indicated that the methodologies described herein are amenable to the high throughput analysis of synthesized biomaterials and will facilitate the rapid and rational design of materials for use in biomedical applications.

INTRODUCTION

Biodegradable polymers have been used in biomedical applications ranging from drug delivery [1], to sutures, to bio-absorbable prostheses [2], to tissue culture scaffolding [3], and stents. Their use in a broad range of applications stems largely from their uniquely versatile and tunable degradation behavior. In particular polyanhydrides have been widely used as carriers for drugs, proteins, and antigens. The Gliadel® wafer, a U.S. FDA approved polyanhydride based drug delivery system, has been used in the treatment of brain tumors. Their history of positive impact for human use [4] along with their chemical diversity makes them ideal candidates for protein and vaccine delivery. Today, many candidate drugs are proteins, which are more susceptible to various forms of deactivation due to their chemical and physical environment [5–7]. To ensure protein stability and functionality, it is highly desirable to provide stable microenvironments for these protein-based drugs during storage and in vivo delivery. Due to their versatile chemistries and degradation rates, polyanhydrides are excellent candidates for protein stabilization and delivery.

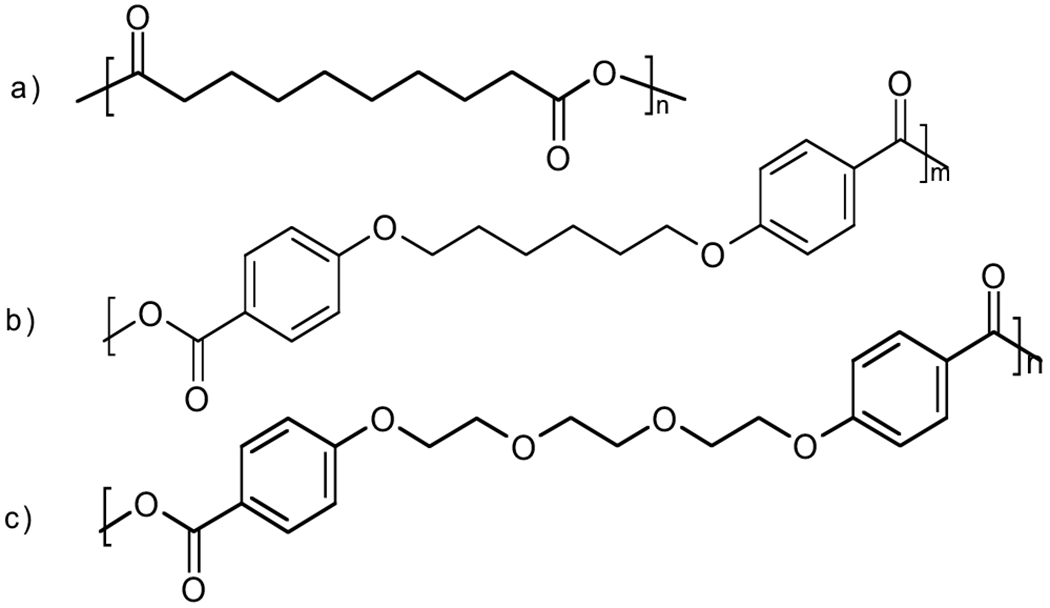

Previous reports from this laboratory [5, 8, 9] have indicated that multiple proteins and antigens can be stably encapsulated into and released from micro/nanospheres composed of random copolymers of sebacic acid (SA) (Fig. 1a), 1,6-bis-(p-carboxyphenoxy)hexane (CPH) (Fig. 1b), and 1,8-bis-(p-carboxyphenoxy)-3,6-dioxaoctane (CPTEG) (Fig. 1c). Specifically, encapsulation of model proteins into these polyanhydrides preserves the primary and secondary structure of proteins [5] and maintains immunogenicity of biologically active antigens [8, 10]. CPH:SA devices degrade by surface erosion, rather than the bulk erosion seen in polyesters. Surface-eroding devices are able to exclude water from the interior during degradation, offering more protection for sensitive payloads [11, 12]. This unique feature has also been observed in vivo, favoring the use of polyanhydrides in human medicine [5, 13, 14]. Additionally, CPTEG:CPH copolymers can be tailored to degrade from bulk-eroding to surface-eroding mechanisms, thereby enabling highly tunable release kinetics for controlled drug delivery [15]. Compared to polyesters, the degradation products of polyanhydrides are less soluble di-carboxylic acids, resulting in a less acidic micro-environment, which enhances the long-term stability of encapsulated proteins [11].

Fig. (1).

Chemical structures of (a) poly(SA); (b) poly(CPH); and (c) poly(CPTEG).

Polyanhydrides have also been used as adjuvants in vaccine delivery devices [8, 16]. A persistent, near zero-order drug release can be obtained, and the polyanhydride chemistry can be used to control the immune response to an antigen. Prolonged presentation of an active antigen, as afforded by the polyanhydrides’ protection and controllable degradation, results in greater balance between the humoral and cell-mediated responses compared to bolus delivery of the antigen [8, 17]. Humoral or Th2 response is accompanied by antibody production, while cell-mediated, or Th1 response, is characterized by macrophage and cytotoxic T cell maturation and activity [18]. Such a balanced response is known to play an important role in the achievement of protective immunity against many intra-cellular pathogens.

Modulation of the release of encapsulated substances is a critically important function of these polymeric devices, and is credited to the unique chemistry and kinetics of polyanhydride degradation in aqueous environment. These polymers have been shown to degrade via hydrolysis to their acidic monomers [13, 19] over a period of years for poly(CPH), weeks for poly(SA) [20, 21], and days for poly(CPTEG) [15]. These degradation times can be modulated by synthesizing copolymers with various combinations of monomers as dictated by application. Less hydrophobic systems (CPTEG and SA rich) tend to degrade more quickly than more hydrophobic systems (CPH rich) [1, 15, 22–24]. Initial burst release from microspheres can also be achieved for certain CPH:SA compositions, and release kinetics can be additionally modified with altered microsphere size [10]. Simple changes such as the number of glycolic oxygens in the polymer’s backbone result in similar differences [15, 24]. Thus, choosing the right polymer chemistry for an application requires navigation of a large parameter space (composition, concentration, synthesis conditions, etc.), which if approached with classical macroscale, single-synthesis methods would require unacceptable amounts of time and cost. Thus, there is a significant need to develop high throughput combinatorial methods aimed to satisfy the demand for rapid discovery without needlessly sacrificing accuracy, time, or cost.

Combinatorial discovery was thrust into the limelight with application in the pharmaceutical industry [2, 25]. Since then, there has been much interest in the development of combinatorial methods for materials science [2]. Recently, the hurdles of expense [26, 27], characterization [25], and availability [28] are being overcome; wide accessibility greatly increases combinatorial methods’ efficacy in allowing more work to be done in parallel. Past combinatorial work in biodegradable polymers has focused largely on characterization of physical properties, such as glass transition temperature [29] and elastic modulus [30], and drug delivery [28]. Cell-based combinatorial methods have also been used to study phenomena such as cell adhesion [31] and protein adsorption [32]. However to our knowledge, none of the past studies present a rapid prototyping, parallel method for combinatorial synthesis and in vitro investigation of cellular interactions. When cells come into contact with biodegradable polymers in vivo, initial interactions and activation can be triggered by surface chemistry, and there is a need for the design of in vitro tests that will allow for both combinatorial synthesis of biomaterials and robust cell based assays to assess the initial cell-biomaterial interaction.

The present work describes the development of a new photolithographic method to design biomaterial libraries for rapid screening by cell-based assays. The speed, low cost, ease of use, and reproducibility of this method allowed for efficient cytotoxic screening and assessment of immune cell activation by discrete libraries of compositionally and concentrationally variant CPH:SA or CPTEG:CPH copolymers. Utilization of this method will allow for flexible and rapid characterization of cell-biomaterial interactions prior to the in vivo studies required for human or animal use [32].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

HPLC Grade Chloroform, 100 mm plastic Petri dishes, and 500 x 750 x 1mm pre-cleaned glass microscope slides were acquired from Fisher Scientific (Fairlawn, NJ). 200 proof ethanol was purchased from Chemistry Stores (Ames, IA). Norland Optical Adhesive 81 (NOA 81) was purchased from Norland Products (Cranbury, NJ). Sebacic acid and 1,6-bis-(p-carboxyphenoxy)hexane prepolymers were prepared with slight modification to well known syntheses [1]. CPTEG diacid was prepared as described previously [15]. Deuterated NMR solvents (DMSO and chloroform) were purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (Andover, MA). MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-y1)-2,5-diphenyltetra-zolium bromide) assays for cytotoxicity screening were obtained from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Sp2/0 mouse myeloma cells were obtained from stock cultures maintained by Iowa State University’s Hybridoma Facility, J774A (J774) mouse macrophage cell line was a gift from Dr. Jesse Hostetter of the Department of Veterinary Pathology at ISU and Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) cells were a gift from Michael Kimbler (Department of Biomedical Sciences at Iowa State University). L929 cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA).

Multi-Well Library Fabrication

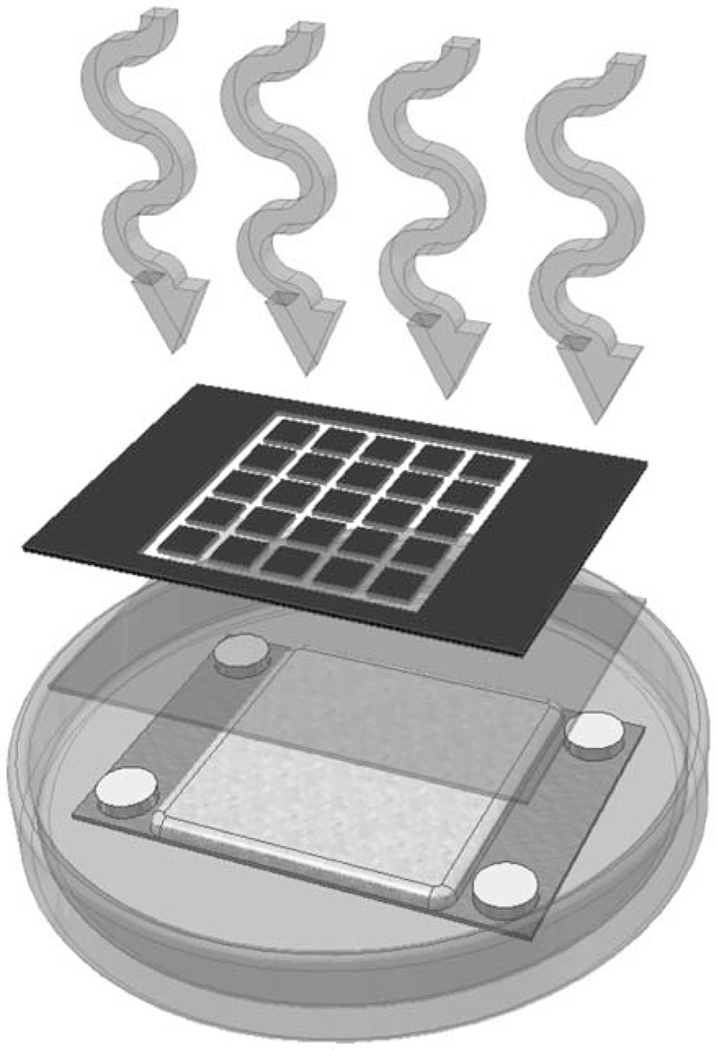

Rapid prototyping was used to fabricate discrete solvent-resistant multi-well substrates capable of containing large enough fluidic volumes to support cell proliferation (Fig. 2). This procedure is an adaptation of existing photolithographic techniques utilizing frontal-polymerizing optical resists [33] described elsewhere [28, 33–36]. Major modifications were made to enable ease of use, speed, durability, reproducibility and cost. The method uses a thiolene-based, UV curing optical adhesive (NOA 81). Mechanistically, this involves the addition of a thiyl radical to a vinyl functional group, followed by radical transfer from the ensuing carbon radical to a thiol functional group [37]. The extremely fast curing in the presence of oxygen using UV light, without the need for traditionally required photoinitiators [38] means that fairly complex structures can be prototyped very easily and rapidly using a simple mask. In this work, the desired 5x5 array of discrete wells was created using a photomask designed with a readily available drawing program and printed on a commercially available laser printer. The mask was then copied as many times as desired onto transparencies with a photocopier. Four of the transparencies were overlaid (to ensure complete opacity) and affixed to a standard glass microscope slide with tape. Wells were given lateral dimensions of 5 x 5 mm, which when combined with a wall height of 2 mm produced space for liquid volumes of 200 μL. To our knowledge, this represents a much greater well capacity than in any previous work.

Fig. (2).

Schematic of photolithographic design of discrete thiolene-based multi-well substrates.

Spacers were taped to regions of a second glass slide which fall outside the desired area of structure formation and served as an upper limit to feature height. The comers of the glass slides were removed with a glass cutter to allow them to fit within standard Petri dishes. Aluminum foil was cut into circles, flattened and laid into standard disposable Petri dish lids. The layer of aluminum served as a surface which could be easily removed from the polymerized NOA 81. Previous work utilized a polydimethylsiloxane release layer (PDMS Sylgard 184 Base and PDMS Sylgard 184 Cure (Dow Coming, Midland, MI)) [28, 33, 34, 36] that requires 12 h to cure, is more expensive, and produced irregular and rounded features due to its uneven surface. NOA 81 was then poured slowly onto the flat aluminum foil to a depth slightly less than the height of the spacers. The slide with spacers was then slowly laid down onto the NOA 81 layer, allowing capillary action to wet only the lower glass surface smoothly and with minimal bubble formation. The stack was then exposed to a collimated long-wave UV source at an intensity of 10 mW/cm2 for 7 min. In order to provide increased resistance to the chlorinated solvents [39], high temperature, and high vacuum the substrate must endure during polyanhydride synthesis, it was necessary to polymerize a thin layer of NOA 81 in the bottom of each well. This was achieved by removing the photomask and exposing the naked substrate to 10 mW/cm2 intensity UV light for 5 s. After precure, the aluminum foil layer was carefully peeled away from the structure and any unreacted NOA 81 remaining in the wells was removed with a blast of compressed air. Liberal amounts of ethanol from a spray bottle helped to more sharply define the features. After the ethanol evaporated, the substrates were postcured under UV light for 17 min at 10 mW/cm2. Finally, the substrates were thermally cured at 80°C for 12 h.

Prepolymer Solution Deposition

Libraries of varying concentration or mole fraction of CPH:SA and CPTEG:CPH copolymers were rapidly deposited using robotics. Two programmable syringe pumps (New Era Pump Systems, Farmingdale, NY) in conjunction with three programmable motorized stages arranged orthogonally (Zaber Technologies, Richmond, British Columbia, Canada) served to fully automate depositions. The pumps and syringes were controlled by third-party macro software operating on the actuators’ respective consoles. Complete 5 x 5 depositions were routinely completed in approximately 5 min.

Combinatorial Synthesis of Polyanhydrides

CPH:SA and CPTEG:CPH copolymer films were synthesized in the discrete well substrate from their corresponding prepolymers. CPH and SA prepolymers were dissolved in chloroform and deposited into the wells in various molar ratios. CPTEG:CPH prepolymers were dissolved in acetic anhydride and deposited in the same manner. With both systems the libraries were placed in a vacuum oven preheated to the necessary temperature (180°C for CPH:SA and 140°C for CPTEG:CPH) and 0.3 torr vacuum for the polycondensation reaction to occur. After synthesis, the polymer libraries were stored in desiccators.

Characterization

Copolymer structures were characterized by 1H NMR in deuterated chloroform on a Varian VXR 300 MHz spectrometer (Palo Alto, CA). Molecular weights were measured by gel permeation chromatography (GPC). GPC samples were dissolved in HPLC-grade chloroform and separated using PL Gel columns from Polymer Laboratories (Amherst, MA) on a Waters GPC system (Milford, MA). 50 μL samples were eluted at 1 mL/min. Elution times were compared to monodisperse polystyrene standards (Fluka, Milwaukee, WI) and used to determine number averaged molecular weights (Mn), and polydispersity indices. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was conducted on a Nicolet Continuum infrared microscope (Thermo Scientific, Madison, WI) in order to verify the ability of the robotics to accurately deposit linearly varying composition gradients. Two hundred scans were collected for each data point at a resolution of 4 cm−1 and nitrogen purge flow rate of 30 SCFH.

High Throughput Cytotoxicity Screening

Cell viability in the presence of CPH:SA and CPTEG:CPH films was assessed using MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay. Cells were grown to near confluency in either cRPMI (RPMI 1640 containing L-glutamine (Mediatech, Herndon, VA) supplemented with 1% non-essential amino acids (Mediatech), 1% sodium pyruvate (Mediatech), 2% essential amino acids (Mediatech), 25 mM HEPES buffer (Mediatech), 100 units/mL penicillin, 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin (Mediatech), 0.05 mg/mL gentamycin (Gibco), 1% L-glutamine (Mediatech), 5 x 10−5 M 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma), and 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum for Sp2/0 cells or in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium or Ham’s F12 with 4.5 g/L glucose (Gibco, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 1% non-essential amino acids (Mediatech), 1% sodium pyruvate (Mediatech), 25 mM HEPES buffer (Mediatech), 100 units/mL penicillin, 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin (Mediatech), 1% L-glutamine (Mediatech), and 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum for J774 and CHO cells. L929 cells were grown to confluency in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium with 4.5 g/L glucose (Gibco, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 1% non-essential amino acids (Mediatech), 1% sodium pyruvate (Mediatech), 2% Sodium Bicarbonate (10% solution) (Mediatech), 100 units/mL penicillin, 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin (Mediatech), 1% L-glutamine (Mediatech), and 10% heat-inactivated horse serum. Cells were maintained in a humidified incubator set at 37°C, 5 % CO2. J774 cells were removed from culture flasks with gentle scraping using sterile cell scrapers (Fisher). CHO and L929 cells were removed from culture flasks by treatment with Trypsin-EDTA solution (Gibco). To generate control wells displaying 100% cytotoxicity, cells were lysed with a cell lysis buffer (Qiagen) containing HC1 (1 M), 2% sodium dilauryl sulfate and 5% Triton 100x (LKB Instruments, Gaithersburg, MD).

The multi-well substrates were incubated in 100 mm Petri dishes atop sterilized gauze pads cut to fit the Petri dish and saturated with sterile phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) in order to create a humid microenvironment and minimize evaporation. 80μL aliquots of 5.0 x 105 cells/mL were incubated for 18 to 24 h with the desired polyanhydride films in each well of the multi-well substrates. 10 μL of MTT salt solution was added to each well. Plates were returned to the incubator for 2-3 h. The solution was then transferred to a 96 well polystyrene assay plate, and each NOA 81 well was washed with 80 μL acidic alcohol solution, which was then added to the corresponding well within the assay plates. Optical density (OD) at 570 nm minus the background OD at 690 nm was measured using a Spectramax 190 Plate Reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Assays were performed on duplicate plates on three separate occasions for each cell type and polymer composition (CPH:SA or CPTEG:CPH), so in total there were twenty-four assays performed with each composition, six for each cell line. The polyanhydride films were also incubated with the MTT solution alone in the absence of cells. The OD measurements were similar to that of the background OD suggesting that the presence of the polyanhydride copolymer films in the library wells did not interfere with the OD measurements.

Cytokine Secretion from J774 Cells

In order to assess immune activation, cytokine production from J774 macrophages was measured following incubation of the cells in the presence of the discrete polyanhydride libraries in the multi-well substrates. Dissolved polymer was deposited to create 4 replicate wells within the 25-well grid. Three wells were left blank (i.e. no polymer deposited) and two wells were treated with 2 μg/m L of lipopolysaccharide (Phenol water extract from E. coli. Sigma) (LPS), which served as a positive control. J774 cells were grown in media as described above to near confluency and removed from the tissue culture flasks using sterile cell scrapers. Cells were washed once by centrifugation and diluted to 1.25 x 106 cells/mL. 100 μL of diluted cells added to each well, as described above. At 48 h, cell free supernatants were collected and stored at −20°C until assayed. Secretion of IL-6, IL-10, IL-12 and TNFα was analyzed using a multiplexed flow cytometric assay (FlowMetric System, Luminex, Austin, TX). Assays were performed on duplicate plates with the J774 cell line on at least three separate occasions for each polymer composition. The results for the background (no polymer) and LPS wells were compared to cells grown in conventional 48 well tissue culture plates.

Statistical Analysis

Analysis was performed with the aid of SAS statistical software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). In the linear mixed models, the Kenwood-Rodgers method was used for calculating degrees of freedom. The cytotoxicity study consisting of varying concentrations (mg/mL) of 50:50 copolymer was fit with a linear model using concentration (mg/mL) as the fixed term. Alternatively, assessment of cytotoxicity based upon changes in polymer composition (% CPH) was performed using a linear mixed model. The fixed term in the composition analyses was mol % CPH and the plate was assigned as the random term in the mixed model. In the analysis of cytokine secretion, a linear mixed model was used in which the mol % CPH was set as the fixed term and plate and day as random terms in the mixed model.

RESULTS

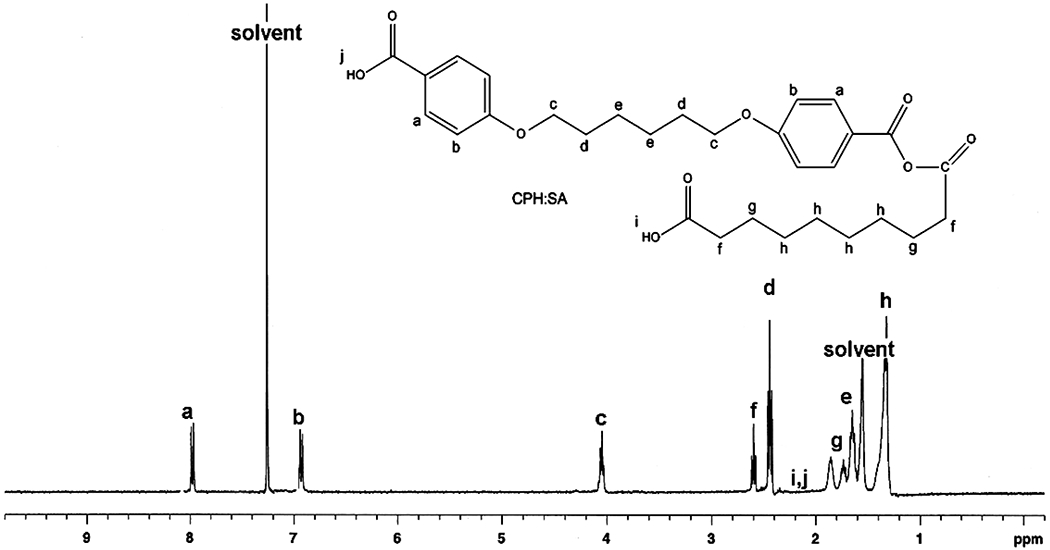

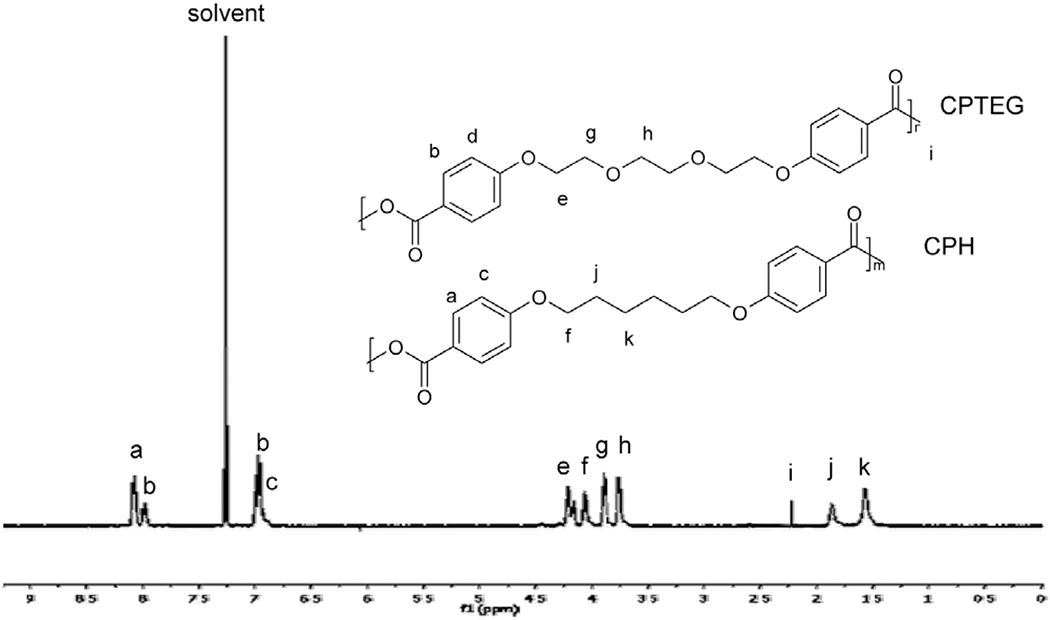

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (1H NMR)

NMR analysis was performed to ensure that the substrate did not interfere in the parallel synthesis of the copolymer libraries. Polyanhydride libraries with concentrations three times higher than that used in the cytotoxicity assays were used in characterization to produce signals large enough to interpret. Representative spectra and lettered chemical shifts denoted in Fig. (3) for CPH:SA and Fig. (4) for CPTEG:CPH are marked as such by comparison to previous work [1, 22]. NMR spectra showed no difference between conventional syntheses methods of similar volumes performed in glass vials and the new combinatorial method performed in the multi-well substrates. Mole fraction gradients in the CPH:SA and CPTEG:CPH systems produced the expected changes in 1H NMR peak area. That is, peaks corresponding to the CPH portion of the copolymer (Peaks a-e in Fig. (3)) became less intense when compared to SA peaks (Peaks f-I in Fig. (3)) as the CPH content was reduced. Similar results were obtained with the CPTEG:CPH system (Fig. 4). This suggests that the multi-well substrate did in fact isolate discrete copolymer compounds with minimal cross-contamination, and that the deposition robot created a smooth compositional gradient. It is also important to note that the end group peaks in these spectra are relatively small, suggesting that the syntheses did in fact drive off much of the prepolymeric acid groups, producing long chain polymers.

Fig. (3).

Proton NMR spectrum for combinatorially synthesized 50:50 CPH:SA copolymer showing chemical shifts.

Fig. (4).

Proton NMR spectrum for combinatorially synthesized 50:50 CPTEG:CPH copolymer showing chemical shifts.

Molecular Weights by Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) and 1H NMR

GPC was performed on various CPH:SA copolymers following synthesis in the wells and their molecular weights were compared to that of conventionally synthesized copolymers. As shown in Table 1, the copolymers had number-average molecular weights suitable for their processing into delivery devices such as tablets and microspheres, and the average polydispersity index was 2.2. Similar results were obtained with the CPTEG:CPH system. In this case, the molecular weights were determined by end-group analysis using 1H NMR spectra (Table 2, for example). These values are consistent with previous work on polyanhydrides synthesized by conventional polycondensation, and add further support to the success of the high throughput synthesis of polymers in the discrete wells [10, 28, 40, 41].

Table 1.

Number Average Molecular Weight and Polydispersity Index of Combinatorially Synthesized CPH:SA Copolymers Obtained by GPC

| CPH:SA Copolymer | Mn (Da) | Polydispersity Index |

|---|---|---|

| 0:100 | 11200 | 2.2 |

| 10:90 | 12700 | 2.5 |

| 20:80 | 9700 | 2.1 |

| 50:50 | 10800 | 2.4 |

| 80:20 | 13300 | 2.0 |

| 90:10 | 16500 | 2.0 |

Table 2.

Number Average Molecular Weight of Combinatorially Synthesized 50:50 CPTEG:CPH Copolymers Obtained by 1H NMR

| 50:50 CPTEG:CPH Trial | Mn (Da) |

|---|---|

| 1 | 10900 |

| 2 | 13500 |

| 3 | 10500 |

| 4 | 13500 |

| 5 | 14200 |

| 6 | 13800 |

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy

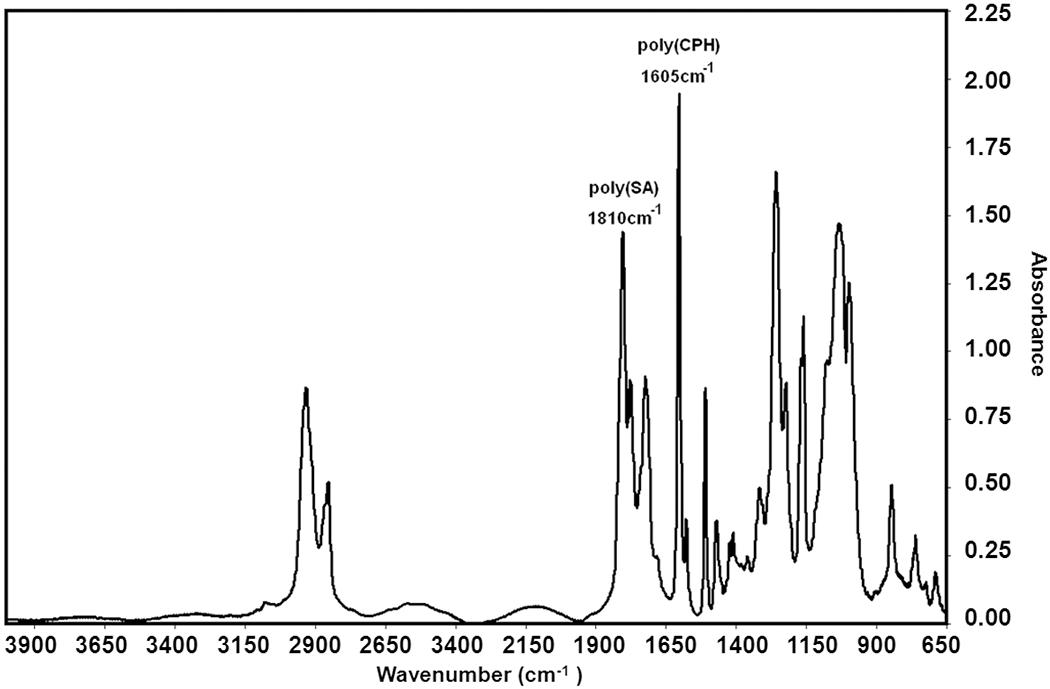

A typical IR spectrum of a CPH:SA copolymer is shown in Fig. 5. The characteristic peak chosen for CPH is sharply defined at 1605 cm−1 and represents the aromatic ring stretching of the CPH moiety. The feature chosen for poly(SA) is at 1810 cm−1 and represents the carboxyl antisymmetric stretching of the aliphatic-aliphatic anhydride bond [42].

Fig. (5).

Representative FTIR spectrum of a 60:40 CPH:SA copolymer with characteristic adsorbances of 1605 cm−1 for the CPH aromatic peak and 1810 cm−1 for the SA aliphatic peak.

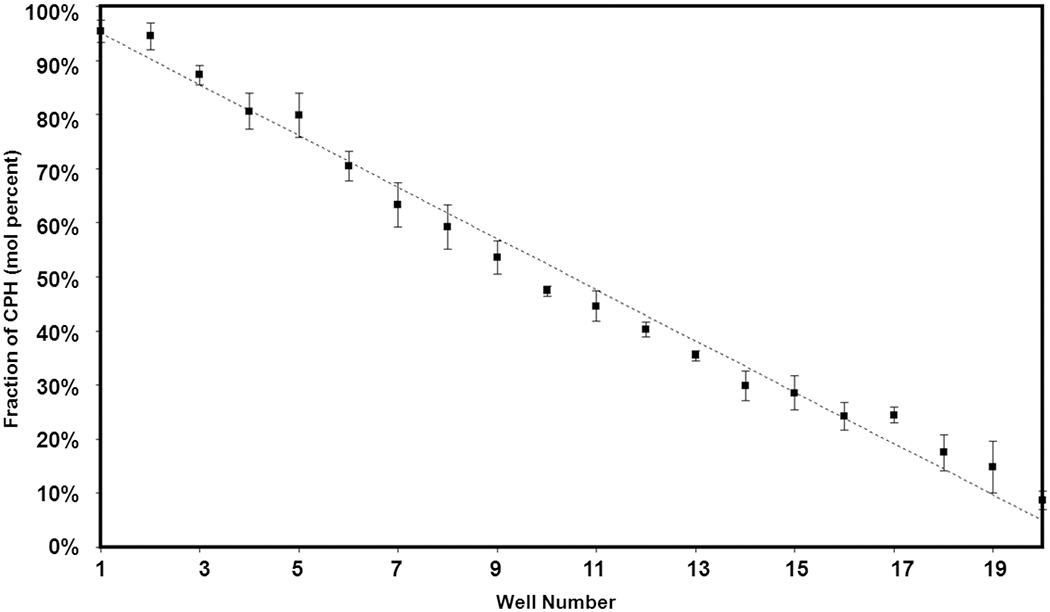

Each of the characteristic peaks was mathematically fitted with a standard normal distribution in order to calculate the area occupied by each band. The calculated peak areas for CPH (1605cm−1) and SA (1810cm−1) were divided by one another and further divided by their respective monomer molecular weights in order to account for the effect that differing values of Mr have on the area of the characteristic peak. The peak areas were also divided by their respective number of occurrences of characteristic peak functionality per monomer. Since the characteristic functionality for CPH (aromatic ring) and SA (aliphatic-aliphatic anhydride bond) both occur twice per monomer unit, the effect can be factored out. The measured area ratios were compared to a previously prepared calibration to elucidate the actual CPH mole fraction. Fig. (6) shows the resulting CPH:SA composition gradient as a function of position in the 5x4 array. The CPTEG:CPH libraries were characterized using NMR. The linearity of the profile spanning the library demonstrates not only the accuracy of the deposition apparatus but also the viability of the thiolene/silicon substrate as a platform for high-throughput transmission FTIR characterization and parallel synthesis of polyanhydrides.

Fig. (6).

Comparison of predicted and experimentally measured composition in a 5x4 discrete library (95% confidence intervals).

MTT Cytotoxicity Screening

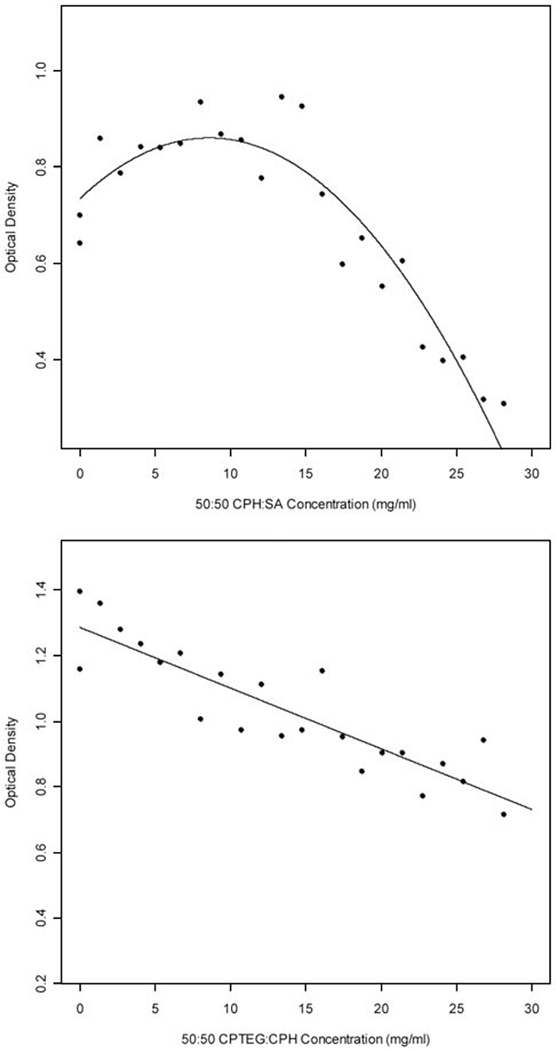

The MTT assay was chosen for screening of the polyanhydrides’ cytotoxicity due to its prevalent use in biocompatibility studies, with a decrease in cell viability being correlated to a decrease in optical density (OD) [43–46]. As the number of metabolically active cells decrease, the amount of tetrazolium rings cleaved and converted to a precipitating product (purple formazan crystals) is reduced, resulting in a relatively lower OD. Conversely, under favorable conditions, cells divide rapidly, thus more cells actively cleave tetrazolium rings resulting in a relatively higher OD. Preliminary tests were run to ensure that there was no interference of the MTT assay with the multi-well substrates. In order to estimate the polyanhydride concentrations at which cytotoxicity is observed, a concentration gradient from 0 to 28 mg/mL 50:50 CPH:SA and 50:50 CPTEG:CPH was combinatorially synthesized and assayed at high throughput by incubating Sp2/0 mouse myeloma cells in the wells for 18 h. The data points in Fig. (7) represent the mean relative OD across four plates for a given concentration whereas the solid line depicts the estimate from the fit of the linear model to the data. The results presented in Fig. (7, top) display the linear fit of a quadratic model to the CPH:SA concentrations. The linear term has a slope of 0.029 with a standard error of 0.007 (p-value = 0.0002) and the quadratic term is −0.002 with a standard error of 0.0003 (p-value < 0.0001). Ninety one observations were used in the model resulting in 88 degrees of freedom for the error term. The results of fitting a linear model to the CPTEG:CPH compositions (Fig. 7, bottom) has a slope of −0.019 with a standard error of 0.003 (p-value < 0.0001). Eighty eight observations were used for the CPTEG:CPH model resulting in 86 degrees of freedom in the error term.

Fig. (7).

Cell (Sp2/0 mouse myeloma) viability as a function of 50:50 CPH:SA (top) and CPTEG:CPH (bottom) concentration. The solid line depicts the fitted quadratic (for CPH:SA, n = 91) or linear (for CPTEG:CPH, n = 88) model respectively. The data points are the means for each concentration tested.

Low concentrations of CPH:SA appear to be stimulatory to the cells as indicated by a mean OD greater than that obtained for cells cultured in wells containing no polymer (Fig. 7, top). However, at higher concentrations (i.e, above 20 mg/mL, which is well above that which would be used physiologically [8]), CPH:SA copolymers were shown to be cytotoxic to Sp2/0 cells. By altering the hydrophobic/hydrophilic properties of the copolymer (i.e. inclusion of CPTEG instead of SA) the overall cytotoxicity was reduced. Taken together, these results indicated that the biocompatibility of polyanhydride copolymers was relatively high. The studies of CPH:SA cytotoxicity determined that a concentration of 2.8 mg/mL was the maximal concentration at which no cytotoxicity was observed. The concentration at which cytotoxicity does not occur was estimated as two standard errors below the mean OD for Sp2/0 cells incubated in the absence of any polymer. The results depicted in Fig. (7) suggest that the concentration at which little or no cytotoxicity is observed may be much higher. To this end, all subsequent studies to evaluate the biological effect of a discrete copolymer library were performed using wells containing 2.8 mg/mL.

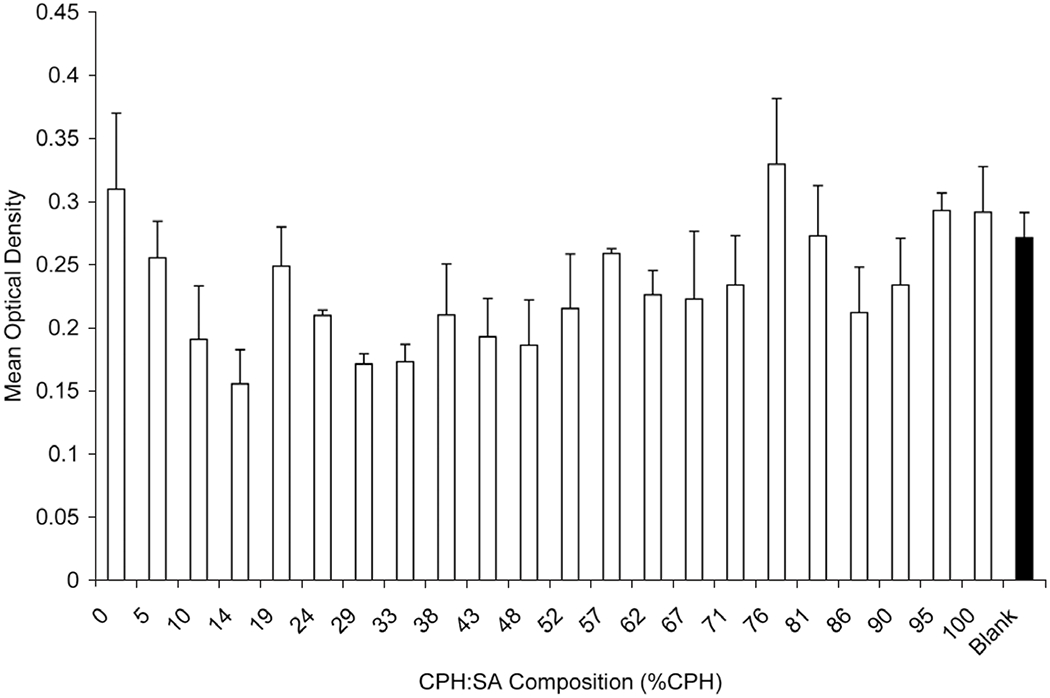

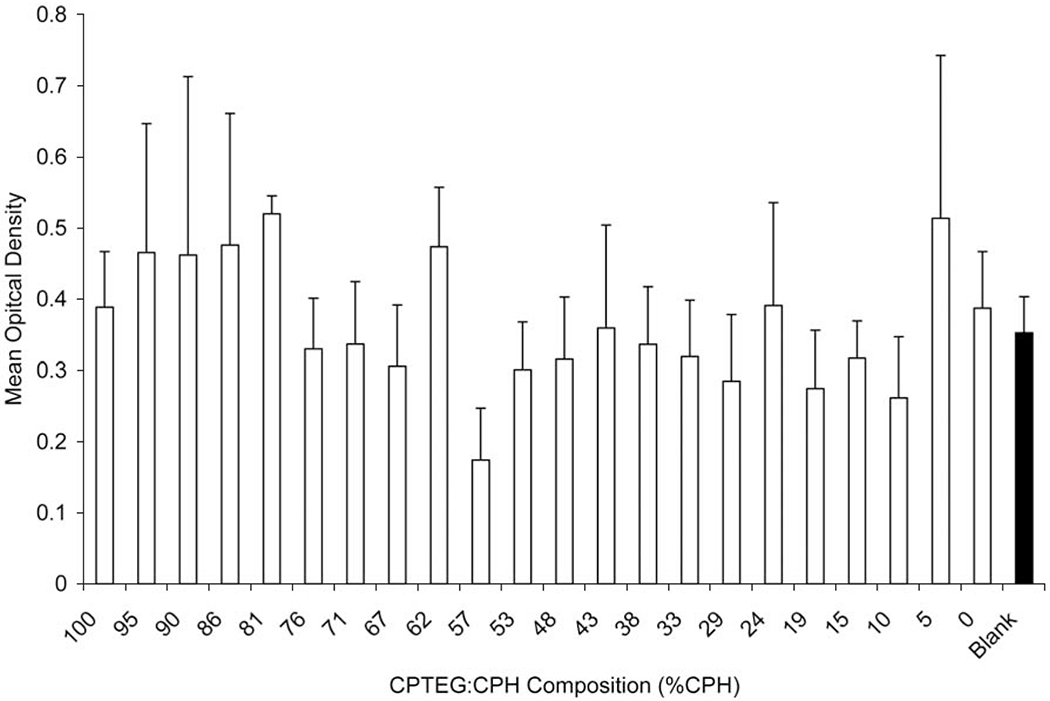

In order to evaluate the effect of varying the fraction of CPH:SA or CPTEG:CPH, multi-well substrates were made in a 5 x 5 format and 2.8 mg/mL copolymer was combinatorially synthesized and deposited in a linear gradient ranging from 100 mol % CPH to 100 mol % SA or CPTEG. A few wells in each plate were left blank to control for the effect of incubating the cells in the NOA 81 substrate wells. Four separate cell lines were used to evaluate the cytotoxicity of the discrete polyanhydride libraries. After incubating the cells in the wells for 18 to 24 h, cytotoxicity was evaluated with MTT. The results in Figs. (8, 9) show that there was no discernable effect of copolymer composed of either CPH:SA or CPTEG:CPH on Sp2/0 myeloma cells. Similarly, these copolymer formulations did not induce cytotoxicity for CHO and L929 fibroblast cell lines or J774 macrophages (data not shown). Table 3 summarizes the findings of the linear mixed model fit for both CPH:SA and CPTEG:CPH copolymers for all the cell lines tested. With the CPH:SA compositional gradients, for Sp2/0 and CHO cells, though the estimated slope obtained using a linear model was significant for some formulations (p < 0.05), the magnitude of the slope was essentially zero (0.0006 and 0.0016, respectively), indicating that there was no biologically significant effect.

Fig. (8).

Effect of CPH:SA copolymer composition on cytotoxicity of Sp2/0 myeloma cells. 5 x 105 cells were incubated for 18 h on 25 multi-well substrate plates with a compositional library of CPH:SA and cytotoxicity was evaluated with MTT assay. Data are represented as mean OD ± SEM for replicate plates. The filled bar indicates cells incubated on multi-well substrate plates without any copolymer. SEM = Standard Error of the Mean.

Fig. (9).

Effect of CPTEG:CPH copolymer composition on cytotoxicity of Sp2/0 myeloma cells. 5 x 105 cells were incubated for 18 h on 25 multi-well substrate plates with a compositional library of CPTEG:CPH and cytotoxicity was evaluated with MTT assay. Data are represented as mean OD ± SEM for replicate plates. The filled bar indicates cells incubated on multi-well substrate plate without any copolymer.

Table 3.

Summary of Linear Fit Model to Data from Compositional Cytotoxicity Experiments. Estimated Slope is the Slope of the Linear Mixed Model Fit to Each Cell Type for Each Copolymer Composition Tested

| Copolymer Type | Cell Type | Estimated Slope of Linear Model | Standard Error of Linear Model | D.F. | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPH:SA | Sp2/0 | 0.0006 | 0.0003 | 62 | 0.0326 |

| CPH:SA | J774 | 0.0002 | 0.0002 | 186 | 0.2494 |

| CPH:SA | L929 | 0.0005 | 0.0003 | 136 | 0.1503 |

| CPH:SA | CHO | 0.0016 | 0.0006 | 125 | 0.0051 |

| CPTEG:CPH | Sp2/0 | 0.0009 | 0.0006 | 62 | 0.1258 |

| CPTEG:CPH | J774 | 0.0005 | 0.0003 | 62 | 0.0967 |

| CPTEG:CPH | L929 | 0.0010 | 0.0012 | 62 | 0.3961 |

| CPTEG:CPH | CHO | 0.0006 | 0.0005 | 83 | 0.2471 |

D.F. = degrees of freedom.

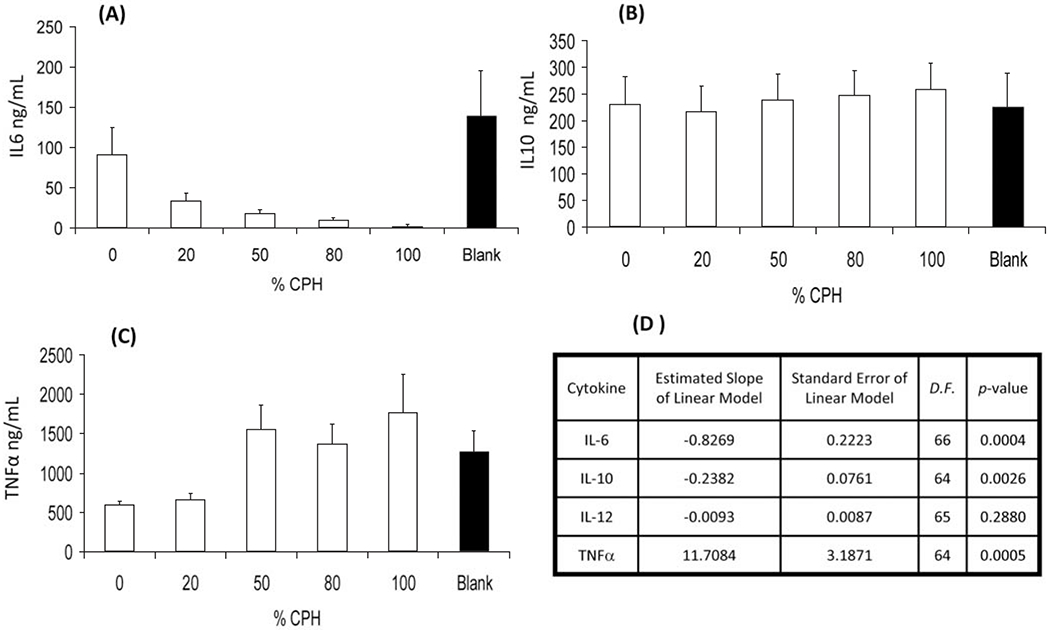

High Throughput Cytokine Screening

In order to evaluate the effect of differing copolymer compositions on the activation of antigen presenting cells, J774 macrophage cells were incubated in the multi-well substrates with discrete compositions of CPH:SA copolymers. After 48 h, cell culture supernatants were collected and analyzed for the secretion of the following cytokines: IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, and TNFα by capture immunoassay. For data analysis, a linear mixed model was fit in order to predict the effect of increasing % of CPH in the CPH:SA copolymer on the cytokine secretion.

Following stimulation with 2 μg/mL LPS, results indicated that the incubation of J774 cells in the multi-well substrate did not affect the secretion of the measured cytokines when compared to that secreted by LPS-stimulated J774 cells incubated in 48 well tissue culture plates (data not shown). While the composition of the copolymer in the wells did not affect the secretion of IL-10 (Fig. 10, panel B) or IL-12 (data not shown), copolymer compositions containing greater than 50% CPH reduced the amount of IL-6 secreted from background levels (Fig. 10, panel A). Correspondingly, the linear mixed model (Fig. 10, panel D) does predict a modest linearly decreasing rate (−0.8269) of IL-6 production with increasing percentages of CPH but essentially no change in IL-10 or IL-12 production (predicted slopes of −0.2382 and −0.0093, respectively). In contrast, the copolymer compositions rich in CPH enhanced the secretion of TNFα (Fig. 10, panel C), which was corroborated with the prediction of the fit linear mixed model with a slope of 11.7084 (Fig. 10, panel D). Collectively, these data suggest that the varying chemical compositions differentially regulate/affect the secretion of IL-6, IL-10, and TNFα.

Fig. (10).

Cytokine secretion from J774 macrophages incubated in multi-well substrates containing 2.8 mg/mL of discrete compositions of CPH:SA was measured by capture immunoassay. Data depicted is the mean ± SEM. (A) IL-6, (B) IL-10, (C) TNFα, and (D) statistical summary of linear mixed model fit to the experimental data. Data are representative of two replicate plates on two separate experiments. D.F. = degrees of freedom.

DISCUSSION

Polyanhydrides, as stated earlier, are generally accepted as being highly biocompatible materials. The goal of these experiments was not to simply confirm the biocompatible nature of CPH:SA and CPTEG:CPH copolymers, but to illustrate a high throughput method for screening of degradable biomaterials using a novel multi-well substrate and combinatorial polymer synthesis. Taken together, these results are consistent with numerous conventional (one-sample-at-a-time) in vitro and in vivo studies that attest to the biocompatibility of polyanhydride systems [14, 47–49]. The highly generalized method developed here will be invaluable in the rapid testing and discovery of optimally tuned biomaterial compositions for drug delivery. Discrete libraries of virtually any geometry can be rapidly produced to screen polymers at any desired resolution. Similarly, the thermally cured multi-well substrate has been newly demonstrated to be highly robust during synthesis at high temperature in the presence of chloroform and acetic anhydride. Thus, many different types of polymer libraries can be created via melt polycondensation in many solvents.

Such a robust, rapid, and generalized method has great potential in various applications. A simple modification of the study could allow for time-dependent parallel monitoring of polyanhydride degradation and cytotoxicity. The study of drug and protein release kinetics would particularly benefit from a combinatorial methodology, as unique release mechanisms have been demonstrated at various copolymer compositions [1, 5, 11]. The discrete multi-well substrate may also find use in high-throughput screening of biodegradable tissue scaffolding materials [50] and integration with microfluidics [35], thus providing a unique combination of generalized high throughput testing, rational design, and discovery of new biomaterials.

CONCLUSIONS

A rapid method has been outlined for prototyping discrete library substrates for high-throughput cytotoxicity and cell activation screening of polyanhydride libraries. This methodology has been validated with NMR and GPC characterization of rapidly synthesized and deposited libraries of poly anhydride chemistries based on CPH:SA and CPTEG:CPH copolymers. The libraries were characterized by high throughput techniques using FTIR spectroscopy and biological responses of various cell lines. There was no observed cytotoxic effect for any CPH:SA or CPTEG:CPH composition at a concentration higher than that expected to be used for a variety of in vivo applications [8]. While the biocompatibility of polyanhydrides has long been established, the methods described herein show the compatibility of the polymers synthesized combinatorially and of the cell based assays. The results from the cytokine secretion studies confirmed the importance of polymer chemistry on the activation of antigen presenting cells. Many of the promiscuous innate immune receptor ligands share the common feature of hydrophobic domains [51]. While it is known that microspheres of various chemistries (i.e. PLGA, PLA and poly-amino acid derivatives) are efficient at delivering protein antigens to antigen presenting cells [52] and that PLGA microspheres can increase activation markers on the surface of antigen presenting cells [53], these previous studies have not systematically evaluated the effect of varying polymer chemistry on immune cell activation. In contrast, the present studies demonstrated that copolymers containing higher hydrophobic (CPH) content induced greater TNFα or pro-inflammatory responses than that observed with less hydrophobic polymers. The level of activation and the behavior of antigen presenting cells such as macrophages and dendritic cells are key factors in the induction and maintenance of a Th1 (cellular) or Th2 (humoral) immune responses [18] and thus underscores the potential of polyanhydrides as effective adjuvants to modulate immune responses [8]. The methods described herein lay a foundation for establishing rapid screening protocols of biomaterials and for quantifying the role of biomaterial chemistry not only in cellular toxicity but also immune activation. These results also add to the large body of evidence supporting the use of polyanhydrides as biocompatible materials for use in drug delivery devices.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

B.N. and M.J.W. gratefully acknowledge financial support from the U.S. Department of Defense – Office of Naval Research (ONR Award # N00014-06-1-1176). This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. EEC 0552584 to B.N. M.P.T. acknowledges financial support from NIH-NCI via the Ruth L. Kirschstein Fellowship. Special thanks to Andrea Dorn for her performance of the Luminex cytokine assays.

REFERENCES

- [1].Shen E; Kipper MJ; Dziadul B; Lim MK; Narasimhan B Mechanistic relationships between polymer micro structure and drug release kinetics in bioerodible polyanhydrides. J. Control. Release, 2002, 82(1), 115–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Thorstenson JB, Narasimhan B Combinatorial Methods for High-Throughput Characterization and Screening of Biodegradable Polymers. In Handbook of Biodegradable Polymeric Materials and Their Applications, Mallapragada SK; Narasimhan B; Eds.; American Scientific: Los Angeles, CA, 2006; Vol. 2, pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Tamanda J; Langer R The Development of Polyanhydrides for Drug Delivery Applications. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed, 1992, 3(4), 315–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Narasimhan B; Kipper MJ Surface-Erodible Biomaterials for Drug Delivery. Adv. Chem. Eng, 2004, 29, 169–218. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Determan AS; Trewyn BG; Lin VS; Nilsen-Hamilton M; Narasimhan B Encapsulation, stabilization, and release of BSA-FITC from polyanhydride microspheres. J. Control. Release, 2004, 100(1), 97–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Cleland JL; Powell MF; Shire SJ The development of stable protein formulations: a close look at protein aggregation, deamidation, and oxidation. Crit. Rev. Ther. Drug Carrier Syst., 1993, 10(4), 307–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Alberts B, Lewis J, Roberts K, Bray D, Raff M, Watson JD Mol. Biol. Cell. 3rd ed.; Garland: New York, 1994; p 89–138. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kipper MJ; Wilson JH; Wannemuehler MJ; Narasimhan B Single dose vaccine based on biodegradable polyanhydride microspheres can modulate immune response mechanism. J. Biomed. Mater. Res, 2006, 76A(4), 798–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Torres MP; Determan AS; Anderson GL; Mallapragada SK; Narasimhan B Amphiphilic polyanhydrides for protein stabilization and release. Biomaterials, 2007, 28(1), 108–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kipper MJ; Shen E; Determan A; Narasimhan B Design of an injectable system based on bioerodible polyanhydride microspheres for sustained drug delivery. Biomaterials, 2002, 23(22), 4405–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Determan AS; Wilson JH; Kipper MJ; Wannemuehler MJ; Narasimhan B Protein stability in the presence of polymer degradation products: consequences for controlled release formulations. Biomaterials, 2006, 27(17), 3312–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gopferich A Mechanisms of polymer degradation and erosion. Biomaterials, 1996, 17(2), 103–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Katti DS; Lakshmi S; Langer R; Laurencin CT Toxicity, biodegradation and elimination of polyanhydrides. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev, 2002, 54(7), 933–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Domb AJ; Nudelman R In vivo and in vitro elimination of aliphatic polyanhydrides. Biomaterials, 1995, 16(4), 319–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Torres MP; Vogel BM; Narasimhan B; Mallapragada SK Synthesis and characterization of novel polyanhydrides with tailored erosion mechanisms. J. Biomed. Mater. Res, 2006, 76(1), 102–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Tabata Y; Gutta S; Langer R Controlled delivery systems for proteins using polyanhydride microspheres. Pharm. Res, 1993, 10(4), 487–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wang X; Uto T; Sato K; Ide K; Akagi T; Okamoto M; Kaneko T; Akashi M; Baba M Potent activation of antigen-specific T cells by antigen-loaded nanospheres. Immunol. Lett, 2005, 98(1), 123–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Janeway CA; Travers P; Shlomichik MJ; Walport M. The Immune System in Health and Disease. In Immunobiology, 6th ed.; Garland Science: New York, 2005; pp 1–134. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Rosen HB; Chang J; Wnek GE; Linhardt RJ; Langer R Bioerodible polyanhydrides for controlled drug delivery. Biomaterials, 1983, 4(2), 131–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].McCann DL; Heatley F; D’Emanuele A Characterization of chemical structure and morphology of eroding polyanhydride copolymers by liquid-state and solid-state H-1 nmr. Polymer, 1999, 40(8), 2151–2162. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Domb AJ; Langer R Solid-State and Solution Stability of Poly(Anhydrides) and Poly(Esters). Macromolecules, 1989, 22(5), 2117–2122. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Domb AJ; Langer R Polyanhydrides .1. Preparation of High-Molecular-Weight Polyanhydrides. J. Polymer Sci. A, 1987, 25(12), 3373–3386. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Domb AJ; Gallardo CF; Langer R Poly(Anhydrides) .3. Poly(Anhydrides) Based on Aliphatic Aromatic Diacids. Macromolecules, 1989, 22(8), 3200–3204. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Vogel BM; Mallapragada SK Synthesis of novel biodegradable polyanhydrides containing aromatic and glycol functionality for tailoring of hydrophilicity in controlled drug delivery devices. Biomaterials, 2005, 26(7), 721–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Meier MAR; Hoogenboom R; Schubert US Combinatorial methods, automated synthesis and high-throughput screening in polymer research: The evolution continues. Macromol. Rapid Commun, 2004, 25(1), 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Guerrero-Sanchez C; Paulus RM; Fijten MWM; de la Mar MJ; Hoogenboom R; Schubert US High-throughput experimentation in synthetic polymer chemistry: from RAFT and anionic polymerizations to process development. Appl. Surf. Sci. , 2006, 252(7), 2555–2561. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Petro M; Nguyen SH; Liu MJ; Kolosov O Combinatorial exploration of polymeric transport agents for targeted delivery of bioactives to human tissues. Macromol. Rapid Commun, 2004, 25(1), 178–188. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Vogel BM; Cabral JT; Eidelman N; Narasimhan B; Mallapragada SK Parallel synthesis and high throughput dissolution testing of biodegradable polyanhydride copolymers. J. Comb. Chem, 2005, 7(6), 921–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Brocchini S; James K; Tangpasuthadol V; Kohn J A combinatorial approach for polymer design. J. of the Am. Chem. Soc, 1997,119(19), 4553–4554. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Tweedie CA; Anderson DG; Langer R; Van Vliet KJ Combinatorial material mechanics: High-throughput polymer synthesis and nanomechanical screening. Adv. Mater, 2005, 17(21), 2599–2604. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Meredith JC; Karim A; Amis EJ Combinatorial methods for investigations in polymer materials science. MRS Bul, 2002, 27(4), 330–335. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Smith JR; Seyda A; Weber N; Knight D; Abramson S; Kohn J Integration of combinatorial synthesis, rapid screening, and computational modeling in biomaterials development. Macromol. Rapid Commun, 2004, 25(1), 127–140. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Cabral JT; Hudson SD; Harrison C; Douglas JF Frontal photopolymerization for microfluidic applications. Langmuir, 2004, 20(23), 10020–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Harrison C; Cabral J; Stafford CM; Karim A; Amis EJ A rapid prototyping technique for the fabrication of solvent-resistant structures. J. Micromech. Microeng, 2004,14(1), 153–158. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Khoury C; Mensing GA; Beebe DJ Ultra rapid prototyping of microfluidic systems using liquid phase photopolymerization. Lab Chip, 2002, 2(1), 50–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Cabral JT; Karim A Discrete combinatorial investigation of polymer mixture phase boundaries. Meas. Sci. Technol, 2005, 16(1), 191–198. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Cramer NB; Davies T; O’Brien AK; Bowman CN Mechanism and modeling of a thiol-ene photopolymerization. Macromolecules, 2003, 3(12), 4631–4636. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Cramer NB; Scott JP; Bowman CN Photopolymerizations of thiol-ene polymers without photoinitiators. Macromolecules, 2002, 5(14), 5361–5365. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Norland Norland Optical Adhesive 81. <http://www.norlandprod.com/adhesives/NOA%2081.html> (July 16, 2006),

- [40].Torres MP; Determan AS; Mallapragada SK; Narasimhan B Polyanhydrides. In Encyclopedia of Chemical Processing, Lee S; Dekker M; Eds.; New York, 2006, pp. 2247–2257. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Kumar N; Langer RS; Domb AJ Polyanhydrides: an overview. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev, 2002, 54(7), 889–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Mathiowitz E; Kreitz M; Pekarek K Morphological Characterization of Bioerodible Polymers .2. Characterization of Polyanhydrides by Fourier-Transform Infrared-Spectroscopy. Macromolecules, 1993, 26(10), 6749–6755. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Zhang Z; Feng SS The drug encapsulation efficiency, in vitro drug release, cellular uptake and cytotoxicity of paclitaxel-loaded poly(lactide)-tocopheryl polyethylene glycol succinate nanoparticles. Biomaterials, 2006, 27(21), 4025–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Fleury C; Petit A; Mwale F; Antoniou J; Zukor DJ; Tabrizian M; Huk OL Effect of cobalt and chromium ions on human MG-63 osteoblasts in vitro: morphology, cytotoxicity, and oxidative stress. Biomaterials, 2006, 27(18), 3351–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Kim SY; Shin IG; Lee YM Amphiphilic diblock copolymeric nanospheres composed of methoxy poly(ethylene glycol) and glycolide: properties, cytotoxicity and drug release behaviour. Biomaterials, 1999, 20(11), 1033–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Mao S; Shuai X; Unger F; Wittmar M; Xie X; Kissel T Synthesis, characterization and cytotoxicity of poly(ethylene glycol)-graft-trimethyl chitosan block copolymers. Biomaterials, 2005, 26(32), 6343–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Domb AJ; Langer J; Robert S Preparation of Anhydride Copolymers U.S. Patent # 4,789,724.

- [48].Laurencin CT; Morris CD; Pierre-Jacques H; Schwartz ER; Keaton AR; Zou L Osteoblast culture on bioerodible polymers: studies of initial cell adhesion and spread. Polym. Adv. Technol, 1992, 3(6), 359–364. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Domb AJ, Maniar M, Haffer A; Andrew ST Biodegradable Polymer Blends for Drug Delivery U.S Patent # 5,919,835. [Google Scholar]

- [50].Yang J; Webb AR; Pickerill SJ; Hageman G; Ameer GA Synthesis and evaluation of poly(diol citrate) biodegradable elastomers. Biomaterials, 2006, 27(9), 1889–1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Seong SY; Matzinger P Hydrophobicity: an ancient damage-associated molecular pattern that initiates innate immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol, 2004, 4(6), 469–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Bramwell VW; Perrie Y Particulate delivery systems for vaccines: what can we expect? J. Pharm. Pharmacol, 2006, 58(6), 717–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Yoshida M; Babensee JE Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) enhances maturation of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. J. Biomed. Mater. Res, 2004, 71(1), 45–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]