Abstract

Background

The prevalence of chronic non-communicable diseases (NCDs) challenges the Chinese health system reform. Little is known for the differences in catastrophic health expenditure (CHE) between urban and rural households with NCD patients. This study aims to measure the differences above and quantify the contribution of each variable in explaining the urban-rural differences.

Methods

Unbalanced panel data were obtained from the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) conducted between 2012 and 2018. The techniques of Fairlie nonlinear decomposition and Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition were employed to measure the contribution of each independent variable to the urban-rural differences.

Results

The CHE incidence and intensity of households with NCD patients were significantly higher in rural areas than in urban areas.

The urban-rural differences in CHE incidence increased from 8.07% in 2012 to 8.18% in 2018, while the urban-rural differences in CHE intensity decreased from 2.15% in 2012 to 2.05% in 2018. From 2012 to 2018, the disparity explained by household income and self-assessed health status of household head increased to some extent. During the same period, the contribution of education attainment to the urban-rural differences in CHE incidence decreased, while the contribution of education attainment to the urban-rural differences in CHE intensity increased slightly.

Conclusions

Compared with urban households with NCD patients, rural households with NCD patients had higher risk of incurring CHE and heavier economic burden of diseases. There was no substantial change in urban-rural inequality in the incidence and intensity of CHE in 2018 compared to 2012. Policy interventions should give priority to improving the household income, education attainment and health awareness of rural patients with NCDs.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12889-021-10887-6.

Keywords: Catastrophic health expenditure, Fairlie nonlinear decomposition, Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition, China

Background

Achieving universal health coverage, defined as ensuring that all people have access to essential health services without suffering financial constraints by 2030, is one of the key targets of the sustainable development goals (SDGs) [1, 2]. However, a global monitoring report released by the World Health Organization and World Bank reflects the situation of “poverty caused by illness” in the global population in 2017: (1) more than 122 million people were classified as “poor” (living on less than $3.10 a day) due to health care expenditure; (2) about 100 million people were pushed into “extremely poor” (living on less than $1.90 a day) because they have to pay for health care [3]. With the prevalence of chronic non-communicable diseases (NCDs) accompanied by accelerated population aging, increasing number of individuals worldwide will suffer from catastrophic health expenditure (CHE) in the future.

As the global epicenter of NCDs epidemic, China is under great pressure. A 2005 study estimated that NCDs had become the leading cause of death and disease burden in China, accounting for 80% of deaths and 70% of disability-adjusted life-years lost [4]. In 2015, NCDs contributed to 86.6% of all deaths and 70% of the total disease burden in China [5]. The heavy burden of NCDs has greatly increased the economic risks for many vulnerable groups in China.

The fundamental functions of a health system is not only to promote access to essential health care services, but also to improve the ability of households to withstand the financial catastrophe associated with illness [6]. The Chinese health system has been working to protect vulnerable households against CHE. In 2009, China’s new round of health system reform involved a series of policy measures, including the reduction of out-of-pocket (OOP) medical expenditure and expansion of basic health care coverage by 2020 [7, 8]. Three types of basic medical insurance schemes, including the Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance (UEBMI), Urban Residents Basic Medical Insurance (URBMI) and New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme (NRCMS), have been established to decrease the financial burden of NCDs on households. In 2013, more than 95% of residents were covered by basic medical insurance in China, which was a sign of universal coverage of basic medical insurance [9, 10]. In addition, supplementary medical insurance (SMI), including commercial medical insurance, public servant medical subsidy, enterprise supplementary medical subsidy, employee medical subsidy for large medical expenses, and employee mutual medical insurance, was established to meet the needs of residents for multiple levels of health services [11]. However, there was still evidence that medical expenditure due to NCDs played an important role in the main causes of poverty among rural households in China [12]. As NCDs are characterized by long treatment duration and high treatment costs [13], substantial financial hardships create obstacles to health services utilization for rural households with NCD patients in China, leading to further escalation of health problems. Therefore, it is necessary and urgent to pay attention to the CHE among rural households with NCD patients.

Several researches have investigated the financial catastrophe among individuals or households suffering from NCDs around the world. Three existing studies emphasized that households with NCD patients were in the high risk to incur CHE in China, Korea and Iran [9, 14, 15]. Gwatidzo (2017) found that adults aged 50 or above in India were less likely to incur CHE due to diabetes mellitus medication use compared to China [16]. Zhao (2019) identified that the CHE incidence among rural households with NCD patients notably exceeded the average level of urban households with NCD patients in China [17]. Xie (2017) verified the main reasons why households with members suffering from NCDs in rural China were prone to CHE [18]. To sum up, most of the studies have explored the CHE of households with NCD patients in rural areas of a country or in a whole country. However, there are seldom researches on the urban-rural differences in CHE among households with NCD patients and its influencing factors. In addition, understanding the urban-rural differences in the financial risks of NCD medical expenses and the factors related to the differences can prompt more effective efforts to reduce the economic risk of rural households with NCD patients.

The objectives of this study were as follows: (1) to measure the extent of CHE for urban and rural households with NCD patients, (2) to examine the urban-rural differences in the degree of CHE between the two groups, and (3) to quantify the contribution of each variable to the urban-rural differences.

Methods

Data source

This study was based on a publicly available database, the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS), which was conducted by the Institute of Social Science Survey (ISSS) of Peking University every 2 y from 2010 to 2018. The CFPS used a three-stage, stratified, probability-proportional-to-scale (PPS) random sampling method to select sample from 25 provinces in China. It was representative that the sample of CFPS representing 94.5% of the population in mainland China [19]. The questionnaire for CFPS involved a wide range of variables, such as demography characteristics, socioeconomic status, health status, health services utilization, family relationships and medical insurance and so on.

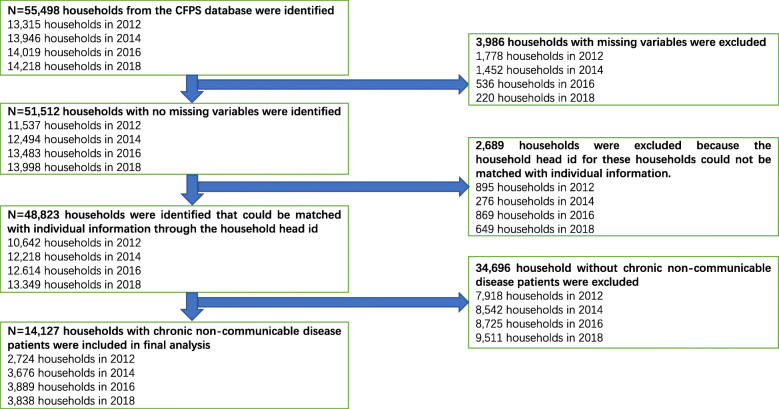

We used four waves of data from the CFPS, which involved 13,315 households in 2012, 13,946 households in 2014, 14,019 households in 2016, and 14,218 households in 2018, respectively. The inclusion criteria for the interviewed households were as follows: (1) no missing variables; and (2) having members with NCDs (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, chronic lung disease, cancer or malignant tumor, liver disease, heart attack, stomach or other digestive disease, emotional nervousness or psychiatric problems, asthma, arthritis or rheumatism, and kidney disease). In this survey, NCDs were determined by whether a respondent had been diagnosed by a doctor within the previous 6 months? Family members were defined as those members who eat together in the household. Finally, 2724 households with NCD patients in 2012, 3676 households with NCD patients in 2014, 3889 households with NCD patients in 2016, and 3838 households with NCD patients in 2018 were specialized in this study, including 1224 households in urban areas and 1500 households in rural areas in 2012, 1782 households in urban areas and 1894 households in rural areas in 2014, 1847 households in urban areas and 2042 households in rural areas in 2016, and 1826 households in urban areas and 2012 households in rural areas in 2018. The detailed sampling process is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of sample selection

Measurement of CHE

We referred to the studies of Wagstaff and van Doorslaer to determine the relevant indicators of measuring CHE [20, 21]. OOP medical expenditure only included direct medical expenditure made by any household members, and excluded indirect expenditure related to seeking health services (e.g., transportation, food, accommodation, lost productivity due to illness). Since the substitution of non-food household expenditure for total household expenditure partly avoided the measurement deviations that were often overlooked in poor households, we used non-food household expenditure as the denominator to calculate CHE [22, 23]. The non-food expenditure of a household is defined as the portion of total household expenditure excluding household food expenditure. According to exiting literature [17, 22, 24, 25], the threshold for CHE was defined as 40%. More specifically, if OOP medical expenditure of a household exceeded 40% of its non-food household expenditure, the household was classified as incurring CHE. A binary variable was defined to determine whether a household experienced CHE or not, as shown in formula (1):

| 1 |

where Ti means the OOP medical expenditure of household i, xi is the total expenditure of household i, fi stands for the food expenditure of household i, and threshold is defined as 40%. The calculation of CHE incidence and intensity can be specified as below:

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

where N represents the total sample size, H means the CHE incidence in the overall sample. CHE intensity is estimated by overshoot and mean positive overshoot (MPO). O stands for overshoot, which is the average percentage of OOP medical expenditure that exceeds a given threshold in the overall sample [26]. MPO indicates the average percentage of OOP medical expenditure in excess of the threshold among households incurring CHE [20]. The higher values of overshoot and MPO both stand for heavier financial burden of diseases for the household.

Definitions of independent variables

Referring to the previous reports, we included the characteristics of each household and its household head into the regression model as independent variables [22, 23, 27–29]. Households characteristics involved six variables: the annual household income per capita, household size, receiving inpatient services, having members below 5 years old, having elderly members and geographic location. The characteristics of household head involved six variables: gender, education, marriage, self-assessed health status, basic medical insurance and SMI. We used the natural logarithm of the annual household income per capita to measure economic status of a household. All income and expenditure variables from 2014 to 2018 were deflated to 2012 using the corresponding consumer price index. In addition, there were only two forms of SMI in this study: (1) the form of commercial medical insurance operated and managed by commercial companies, and (2) the form in which industry organizations raise and manage their own funds in according with the principles of insurance. Table 1 presents the detailed descriptions of the above independent variables.

Table 1.

Description of variables

| Variables | Description |

|---|---|

| Household expenditure (CNT) | Total consumption expenditure of a household. |

| OOP medical expenditure (CNY) | Total out-of-pocket medical expenditure of a household. |

| Food expenditure (CNY) | Total food consumption expenditure of a household. |

| Household income (CNY) | The annual household income per capita. |

| Household size | The number of household members. |

| Inpatient | At least one household member received inpatient services in last year; Yes = 1; No = 0a. |

| Household members aged<=5 | At least one household member below 5 years old; Yes = 1; No = 0a. |

| Household members aged> = 60 | At least one household member over 60 years old; Yes = 1; No = 0a. |

| Geographic location | East = 1a; Central = 2; West = 3. |

| Gender of household head | Female = 0a; Male = 1. |

| Education of household head | Illiterate = 1a; Primary school = 2; Middle school = 3; High school and above = 4. |

| Marriage of household head | Married = 1; Unmarried = 0a. |

| Self-assessed health status of household head | Unhealthy = 0a; Healthy = 1. |

| Basic medical insurance | No medical insurance = 1a; UEBMI = 2; URBMI = 3; NRCMS = 4; Two kind of medical insurance = 5 |

| SMI | The household head is covered by SMI; Yes = 1; No = 0a. |

Note: a Reference group; OOP Out-of-pocket; UEBMI Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance, URBMI Urban Residents Basic Medical Insurance, NRCMS New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme, SMI Supplementary medical insurance

Methodology

The Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition technique, proposed by Blinder and Oaxaca [30, 31], was applied in this study to analyze the contribution of each independent variable to the urban-rural differences in CHE. The implementation of decomposition analysis needs to be based on the relationship between CHE and a series of independent variables.

As CHE incidence (Ei) is a binary variable, probit model is applied to estimate the effect of the independent variables on the CHE incidence. The specific regression model is shown below:

| 5 |

where F represents the cumulative distribution function of the standard normal distribution, superscript γ represents the rural or urban households, Y is the CHE incidence, X stands for the independent variables, and β denotes the regression coefficient.

Fairlie extended the technique of Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition to the application of nonlinear model [32, 33]. Given the probit regression model is a nonlinear regression model, this study employed the method of Fairlie nonlinear decomposition to decompose the urban-rural differences in CHE incidence between two groups into two components:

| 6 |

Where superscript R represents the rural households, superscript U means the urban households. does not necessarily equal . The first term in formula (6) stands for the explained part of the urban-rural differences between two grousps, which is caused by the disparity in distribution of independent variables, and the second term represents the unexplained part due to the disparity in regression coefficient [34].

The detailed decomposition involves a natural one-to-one matching of cases between the two groups to identify the contribution of independent variables. The subsample was drawn from the majority group (rural households), and matched the minority group (urban households) based on the ranking of CHE incidence. The contribution of variable X1 to the urban-rural differences in CHE incidence is estimated as follows:

| 7 |

Where β∗ stands for the regression coefficient from the probit model for the overall sample. It should be noted that the results are sensitive to the order of independent variables in the decomposition of nonlinear model [34]. Following Fairlie [33], independent variables were randomly ordered in the decomposition of nonlinear model. This study repeated the above steps 1000 times to obtain the average value of decomposition results, representing the contribution of each independent variable.

Similarly, the contribution of X2 to the urban-rural differences in CHE incidence is calculated as follows:

| 8 |

In addition, since the CHE intensity (Oi) is a continuous variable, multiple linear regression is used to analyze the factors affecting the CHE intensity. The specific regression model can be written as:

| 9 |

where Y represents the CHE intensity, X stands for a vector of independent variables, β is a vector of regression coefficient including intercept, and ε denotes the random error term.

The contribution of each independent variable to the urban-rural differences in CHE intensity was divided into two components using two-fold Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition approach [35, 36]:

| 10 |

Where β∗ denotes the regression coefficient from the multiple linear regression for the overall sample, represents the corresponding covariate means of the independent variables. The first term indicates the explained part, representing the contribution attributable to group disparity in distribution of independent variables, and the second term indicates the unexplained part, representing the contribution attributable to group disparity in regression coefficient.

It is necessary to emphasize that the Fairlie nonlinear decomposition and Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition are mainly applied to analyze cross-sectional data. Therefore, the regression coefficients needed to calculate the decomposition results were mainly derived from the cross-sectional analysis of the corresponding years. However, considering the superiority of the panel regression model for causal inference and the limited length of this paper, we only presented the analysis results of the panel regression model. In general, panel regression model can be categorized as fixed effects model and random effects model. Fixed effects model would be a poor choice in a situation where independent variables don’t change much over time [11]. In this study, most of the interviewed households included variables (e.g., geographic location, gender of the household head, etc.) that did not change over time. Given the strict samples inclusion criteria for the fixed effects model, we applied random effects panel model for regression analysis.

All statistical analyses were performed in STATA software version 15.1, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Table 2 shows the summary statistics for general characteristics of the urban and rural households with NCD patients. From 2012 to 2018, the mean household size in rural areas was greater than that in urban areas. Meanwhile, the rural households had higher probability in receiving inpatient services in the last 12 months, having children below 5 years old, and having elderly members. In terms of the coverage of basic medical insurance, the proportion of household head with UEBMI and URBMI was higher in urban areas than in rural areas, while the proportion of household head with NRCMS was higher in rural areas than in urban areas. With respect to the coverage of SMI, the proportion of household head having SMI was higher in urban areas in comparison with the rural areas. The percentage of households having female household head was higher in urban areas than in rural areas. In urban areas, the highest percentage of households were located in the east, while in rural areas, the highest percentage of households were located in the west. The education level of household heads in urban areas was mainly middle school or high school and above, while the highest proportion of household head in rural areas was illiterate.

Table 2.

Summary statistics of variables

| Variables | 2012 | 2014 | ||||||

| Urban areas | Rural areas | Urban areas | Rural areas | |||||

| Mean(N) | S.D. (%) | Mean(N) | S.D. (%) | Mean(N) | S.D. (%) | Mean(N) | S.D. (%) | |

| Household expenditure (CNY) | 50,926.38 | 76,144.12 | 32,051.80 | 34,346.17 | 58,323.30 | 85,216.30 | 37,469.02 | 51,815.58 |

| OOP medical expenditure (CNY) | 6056.99 | 16,110.78 | 4895.33 | 11,161.51 | 6749.66 | 15,948.90 | 6043.14 | 12,331.56 |

| Food household expenditure (CNY) | 17,327.07 | 15,105.43 | 12,960.50 | 11,634.00 | 20,079.08 | 16,056.22 | 10,619.55 | 11,161.20 |

| Household size | 3.68 | 1.67 | 4.29 | 1.92 | 3.62 | 1.72 | 4.20 | 1.92 |

| Inpatient | ||||||||

| Yes | 450 | 36.76 | 554 | 36.93 | 737 | 41.36 | 825 | 43.56 |

| No1 | 774 | 63.24 | 946 | 63.07 | 1045 | 58.64 | 1069 | 56.44 |

| Household members aged<=5 | ||||||||

| Yes | 205 | 16.75 | 357 | 23.80 | 290 | 16.27 | 427 | 22.54 |

| No1 | 1019 | 83.25 | 1143 | 76.20 | 1492 | 83.73 | 1467 | 77.46 |

| Household members aged> = 60 | ||||||||

| Yes | 583 | 47.63 | 762 | 50.80 | 983 | 55.16 | 1057 | 55.81 |

| No1 | 641 | 52.37 | 738 | 49.20 | 799 | 44.84 | 837 | 44.19 |

| Geographic location | ||||||||

| East1 | 629 | 51.39 | 509 | 33.93 | 852 | 47.81 | 664 | 35.06 |

| Central | 401 | 32.76 | 451 | 30.07 | 595 | 33.39 | 578 | 30.52 |

| West | 194 | 15.85 | 540 | 36.00 | 335 | 18.80 | 652 | 34.42 |

| Gender of household head | ||||||||

| Female1 | 648 | 52.94 | 582 | 38.80 | 932 | 52.30 | 785 | 41.45 |

| Male | 576 | 47.06 | 918 | 61.20 | 850 | 47.70 | 1109 | 58.55 |

| Education of household head | ||||||||

| Illiterate1 | 256 | 20.92 | 585 | 39.00 | 327 | 18.35 | 657 | 34.69 |

| Primary school | 225 | 18.38 | 410 | 27.33 | 368 | 20.65 | 572 | 30.20 |

| Middle school | 367 | 29.98 | 364 | 24.27 | 549 | 30.81 | 481 | 25.40 |

| High school and above | 376 | 30.72 | 141 | 9.40 | 538 | 30.19 | 184 | 9.71 |

| Marriage of household head | ||||||||

| Married | 1094 | 89.38 | 1370 | 91.33 | 1549 | 86.92 | 1710 | 90.29 |

| Unmarried1 | 130 | 10.62 | 130 | 8.67 | 233 | 13.08 | 184 | 9.71 |

| Self-assessed health status of household head | ||||||||

| Unhealthy1 | 685 | 55.96 | 821 | 54.73 | 866 | 48.60 | 938 | 49.52 |

| Healthy | 539 | 44.04 | 679 | 45.27 | 916 | 51.40 | 956 | 50.48 |

| Basic medical insurance | ||||||||

| No medical insurance1 | 175 | 14.30 | 98 | 6.53 | 150 | 8.42 | 95 | 5.02 |

| UEBMI | 382 | 31.21 | 64 | 4.27 | 570 | 31.99 | 82 | 4.33 |

| URBMI | 226 | 18.46 | 36 | 2.40 | 316 | 17.73 | 53 | 2.80 |

| NRCMS | 429 | 35.05 | 1297 | 86.47 | 722 | 40.52 | 1657 | 87.49 |

| Two kinds of medical insurance | 12 | 0.98 | 5 | 0.33 | 24 | 1.35 | 7 | 0.37 |

| SMI | ||||||||

| Yes | 11 | 0.90 | 3 | 0.20 | 38 | 2.13 | 15 | 0.79 |

| No1 | 1213 | 99.10 | 1497 | 99.80 | 1744 | 97.87 | 1879 | 99.21 |

| Observations | 1224 | 100 | 1500 | 100 | 1782 | 100 | 1894 | 100 |

| Variables | 2016 | 2018 | ||||||

| Urban areas | Rural areas | Urban areas | Rural areas | |||||

| Mean(N) | S.D. (%) | Mean(N) | S.D. (%) | Mean(N) | S.D. (%) | Mean(N) | S.D. (%) | |

| Household expenditure (CNY) | 67,405.13 | 120,825.70 | 40,183.21 | 47,160.57 | 71,220.84 | 77,596.94 | 38,913.09 | 40,913.34 |

| OOP medical expenditure (CNY) | 8329.21 | 20,640.78 | 6760.40 | 14,725.37 | 7832.77 | 17,389.48 | 6746.01 | 15,173.89 |

| Food household expenditure (CNY) | 21,125.59 | 16,339.34 | 10,601.42 | 11,455.37 | 22,927.93 | 18,662.01 | 10,933.08 | 10,910.03 |

| Household size | 3.72 | 1.84 | 4.27 | 2.02 | 3.71 | 1.91 | 4.12 | 2.06 |

| Inpatient | ||||||||

| Yes | 833 | 45.10 | 958 | 46.91 | 842 | 46.11 | 989 | 49.16 |

| No1 | 1014 | 54.90 | 1084 | 53.09 | 984 | 53.89 | 1023 | 50.84 |

| Household members aged<=5 | ||||||||

| Yes | 295 | 15.97 | 440 | 21.55 | 309 | 16.92 | 378 | 18.79 |

| No1 | 1552 | 84.03 | 1602 | 78.45 | 1517 | 83.08 | 1634 | 81.21 |

| Household members aged> = 60 | ||||||||

| Yes | 1096 | 59.34 | 1215 | 59.50 | 1107 | 60.62 | 1291 | 64.17 |

| No1 | 751 | 40.66 | 827 | 40.50 | 719 | 39.38 | 721 | 35.83 |

| Geographic location | ||||||||

| East1 | 811 | 43.91 | 626 | 30.66 | 903 | 49.45 | 629 | 31.26 |

| Central | 660 | 35.73 | 653 | 31.98 | 540 | 29.57 | 608 | 30.22 |

| West | 376 | 20.36 | 763 | 37.37 | 383 | 20.97 | 775 | 38.52 |

| Gender of household head | ||||||||

| Female1 | 984 | 53.28 | 905 | 44.32 | 927 | 50.77 | 871 | 43.29 |

| Male | 863 | 46.72 | 1137 | 55.68 | 899 | 49.23 | 1141 | 56.71 |

| Education of household head | ||||||||

| Illiterate1 | 394 | 21.33 | 754 | 36.92 | 312 | 17.09 | 699 | 34.74 |

| Primary school | 380 | 20.57 | 584 | 28.60 | 353 | 19.33 | 555 | 27.58 |

| Middle school | 537 | 29.07 | 492 | 24.09 | 589 | 32.26 | 520 | 25.84 |

| High school and above | 536 | 29.02 | 212 | 10.38 | 572 | 31.33 | 238 | 11.83 |

| Marriage of household head | ||||||||

| Married | 1593 | 86.25 | 1798 | 88.05 | 1580 | 86.53 | 1736 | 86.28 |

| Unmarried1 | 254 | 13.75 | 244 | 11.95 | 246 | 13.47 | 276 | 13.72 |

| Self-assessed health status of household head | ||||||||

| Unhealthy1 | 951 | 51.49 | 1132 | 55.44 | 855 | 46.82 | 1009 | 50.15 |

| Healthy | 896 | 48.51 | 910 | 44.56 | 971 | 53.18 | 1003 | 49.85 |

| Basic medical insurance | ||||||||

| No medical insurance | 164 | 8.88 | 92 | 4.51 | 154 | 8.43 | 120 | 5.96 |

| UEBMI | 522 | 28.26 | 70 | 3.43 | 534 | 29.24 | 71 | 3.53 |

| URBMI | 337 | 18.25 | 35 | 1.71 | 351 | 19.22 | 41 | 2.04 |

| NRCMS | 806 | 43.64 | 1838 | 90.01 | 770 | 42.17 | 1774 | 88.17 |

| Two kinds of medical insurance | 18 | 0.97 | 7 | 0.34 | 17 | 0.93 | 6 | 0.30 |

| SMI | ||||||||

| Yes | 28 | 1.52 | 11 | 0.54 | 33 | 1.81 | 18 | 0.89 |

| No1 | 1819 | 98.48 | 2031 | 99.46 | 1793 | 98.19 | 1994 | 99.11 |

| Observations | 1847 | 100 | 2042 | 100 | 1826 | 100 | 2012 | 100 |

Note: 1 Reference group; OOP Out-of-pocket; UEBMI Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance; URBMI Urban Residents Basic Medical Insurance, NRCMS New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme, SMI Supplementary medical insurance

CHE incidence and intensity

Table 3 illustrates CHE incidence and intensity of urban and rural households with NCD patients. In 2018, 17.96% of households in urban areas experienced CHE. Meanwhile, the overshoot of urban households was 3.98% in 2018, suggesting that the average percentage of OOP medical expenditure that exceeded the given threshold over all urban households was 3.98%. The MPO for urban households was 22.16% in 2018, meaning that if the burden of overshoot was divided equally by all urban households incurring CHE, the average extent of exceeding given threshold was 22.16%. Each of the other row could be interpreted in a similar pattern for rural/urban households with NCD patients in 2012/2014/2016/2018.

Table 3.

CHE incidence and intensity in rural and urban households with NCD patients

| Urban areas | Rural areas | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | Incidence | 19.53 | 27.60 |

| Overshoot | 4.24 | 6.40 | |

| MPO | 21.71 | 23.19 | |

| 2014 | Incidence | 18.80 | 26.03 |

| Overshoot | 4.27 | 5.75 | |

| MPO | 22.71 | 22.09 | |

| 2016 | Incidence | 20.19 | 26.00 |

| Overshoot | 4.44 | 6.21 | |

| MPO | 21.99 | 23.88 | |

| 2018 | Incidence | 17.96 | 26.14 |

| Overshoot | 3.98 | 6.03 | |

| MPO | 22.16 | 23.07 |

Note: CHE Catastrophic health expenditure, MPO Mean positive overshoot

From 2012 to 2018, the CHE incidence decreased from 19.53 to 17.96% in urban households with NCD patients and decreased from 27.60 to 26.14% in rural households with NCD patients. The overshoot decreased from 4.24 to 3.98% in urban households with NCD patients and decreased from 6.40 to 6.03% in rural households with NCD patients. The MPO increased from 21.71 to 22.16% in urban households with NCD patients and decreased from 23.19 to 23.07% in rural households with NCD patients. None of the indicators showed a steady upward or downward trend.

Associated factors of CHE incidence

Table 4 presents the results of random effects panel probit regression model for factors associated with CHE incidence in urban and rural households with NCD patients. Household income and household size were negatively associated with CHE incidence. Better self-rated health status and higher education attainment of household head significantly decreased the CHE incidence, while receiving inpatient services in the last 12 months and having elderly members significantly increased the occurrence of exposure to CHE. The geographic location of west was negatively correlated with CHE incidence. Having children below 5 years old significantly increased the CHE incidence of rural households. SMI was negatively associated with the CHE incidence of urban households. Meanwhile, UEBMI and URBMI were negatively associated with CHE incidence, while NRCMS was positively correlated with CHE incidence. However, none of the three types of basic medical insurance had a significant effect on the CHE incidence.

Table 4.

Association between factors and CHE incidence in rural and urban households with NCD patients

| Variables | Urban areas | Rural areas | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| dy/dx | Std. Err. | dy/dx | Std. Err. | |

| Household income | −0.0328** | 0.0044 | −0.0281** | 0.0044 |

| Household size | −0.0362** | 0.0032 | −0.0457** | 0.0030 |

| Inpatient, yes | 0.1720** | 0.0087 | 0.1871** | 0.0091 |

| Household members aged<=5, yes | −0.0093 | 0.0153 | 0.0330* | 0.0141 |

| Household members aged> = 60, yes | 0.0604** | 0.0099 | 0.0778** | 0.0107 |

| Geographic location | ||||

| East1 | ||||

| Central | −0.0059 | 0.0107 | −0.0225 | 0.0128 |

| West | −0.0285* | 0.0130 | −0.0699** | 0.0127 |

| Gender of household head, male | −0.0018 | 0.0092 | 0.0095 | 0.0102 |

| Education of household head | ||||

| Illiterate1 | ||||

| Primary school | −0.0359** | 0.0131 | −0.0493** | 0.0124 |

| Middle school | −0.0799** | 0.0128 | −0.0673** | 0.0137 |

| High school and above | − 0.1035** | 0.0144 | − 0.0596** | 0.0196 |

| Marriage of household head, married | −0.0150 | 0.0131 | 0.0069 | 0.0155 |

| Self-assessed health status of household head, healthy | −0.0804** | 0.0091 | −0.0724** | 0.0098 |

| Basic medical insurance | ||||

| No medical insurance1 | ||||

| UEBMI | −0.0160 | 0.0170 | −0.0074 | 0.0342 |

| URBMI | −0.0059 | 0.0176 | −0.0280 | 0.0395 |

| NRCMS | 0.0067 | 0.0161 | 0.0328 | 0.0214 |

| Two kinds of medical insurance | −0.1214 | 0.0626 | −0.0966 | 0.1068 |

| SMI, yes | −0.0889* | 0.0451 | − 0.0918 | 0.0684 |

Note: 1 Reference group; UEBMI Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance; URBMI Urban Residents Basic Medical Insurance; NRCMS New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme; SMI Supplementary medical insurance; The dy/dx in brackets indicates the marginal effect; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01

Associated factors of CHE intensity

The associated factors of the CHE intensity (Oi) are shown in Table 5. These results indicated a significant negative association between CHE intensity and household income, and between CHE intensity and household size. Better self-rated health status and higher education attainment of household head significantly decreased the CHE intensity, while receiving inpatient services in the last 12 months and having elderly members significantly increased the CHE intensity. The geographic location of west significantly decreased the CHE intensity. SMI was negatively associated with the CHE intensity of rural households. Meanwhile, URBMI was negatively correlated with CHE intensity, while NRCMS was positively associated with CHE intensity. UEBMI was negatively correlated with CHE intensity of urban households, and was positively associated with CHE intensity of rural households. However, none of the three types of basic medical insurance had a significant effect on the CHE intensity.

Table 5.

Association between factors and CHE intensity in rural and urban households with NCD patients

| Variables | Urban areas | Rural areas | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| dy/dx | Std. Err. | dy/dx | Std. Err. | |

| Household income | −0.0098** | 0.0014 | −0.0105** | 0.0017 |

| Household size | −0.0104** | 0.0009 | −0.0105** | 0.0012 |

| Inpatient, yes | 0.0490** | 0.0027 | 0.0538** | 0.0034 |

| Household members aged<=5, yes | −0.0023 | 0.0040 | 0.0001 | 0.0050 |

| Household members aged> = 60, yes | 0.0153** | 0.0028 | 0.0206** | 0.0042 |

| Geographic location | ||||

| East1 | ||||

| Central | −0.0057 | 0.0032 | −0.0107 | 0.0060 |

| West | −0.0127** | 0.0038 | −0.0245** | 0.0058 |

| Gender of household head, male | 0.0047 | 0.0027 | 0.0032 | 0.0038 |

| Education of household head | ||||

| Illiterate1 | ||||

| Primary school | −0.0191** | 00043 | − 0.0152** | 0.0051 |

| Middle school | −0.0275** | 0.0041 | −0.0197** | 0.0055 |

| High school and above | −0.0304** | 0.0044 | −0.0106 | 0.0076 |

| Marriage of household head, married | −0.0018 | 0.0041 | 0.0037 | 0.0063 |

| Self-assessed health status of household head, healthy | −0.0203** | 0.0027 | −0.0159** | 0.0036 |

| Basic medical insurance | ||||

| No medical insurance1 | ||||

| UEBMI | −0.0082 | 0.0049 | 0.0025 | 0.0119 |

| URBMI | −0.0034 | 0.0052 | −0.0076 | 0.0141 |

| NRCMS | 0.0033 | 0.0048 | 0.0134 | 0.0074 |

| Two kinds of medical insurance | −0.0228 | 0.0130 | 0.0216 | 0.0299 |

| SMI, yes | −0.0137 | 0.0102 | −0.0405* | 0.0206 |

Note: 1 Reference group; UEBMI Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance; URBMI Urban Residents Basic Medical Insurance; NRCMS New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme; SMI Supplementary medical insurance; The dy/dx in brackets indicates the marginal effect; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01

Aggregate decomposition

Table 6 displays the results for aggregate decomposition of the urban-rural differences in CHE incidence and intensity (Oi) among households with NCD patients. The explained disparity of CHE incidence increased from 14.87% in 2012 to 57.95% in 2018, a relative increase of 289.71%. The corresponding values of CHE intensity rose from 59.53% in 2012 to 88.29% in 2018, a relative increase of 48.31%. None of the indicators showed a steady upward or downward trend.

Table 6.

Aggregate decomposition of the urban-rural differences in CHE incidence and intensity among households with NCD patients

| Total differences | Explained part | Unexplained part | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | Percent | Coefficient | Percent | Coefficient | Percent | ||

| 2012 | CHE incidence | 0.0807 | 100.00 | 0.0120 | 14.87 | 0.0687 | 85.13 |

| CHE intensity | 0.0215 | 100.00 | 0.0128 | 59.53 | 0.0087 | 40.47 | |

| 2014 | CHE incidence | 0.0723 | 100.00 | 0.0411 | 56.85 | 0.0312 | 43.15 |

| CHE intensity | 0.0148 | 100.00 | 0.0067 | 45.27 | 0.0081 | 54.73 | |

| 2016 | CHE incidence | 0.0581 | 100.00 | 0.0231 | 39.76 | 0.0350 | 60.24 |

| CHE intensity | 0.0178 | 100.00 | 0.0114 | 64.04 | 0.0064 | 35.96 | |

| 2018 | CHE incidence | 0.0818 | 100.00 | 0.0474 | 57.95 | 0.0344 | 42.05 |

| CHE intensity | 0.0205 | 100.00 | 0.0181 | 88.29 | 0.0024 | 11.71 | |

Note: CHE Catastrophic health expenditure

Decomposition of contribution of all explanatory variables

The urban-rural differences in CHE incidence and intensity (Oi) among households with NCD patients is further decomposed into the contribution of each variable, as shown in Tables 7 and 8.

Table 7.

Detailed decomposition of the urban-rural differences in CHE incidence among households with NCD patients

| Variables | 2012 | 2014 | 2016 | 2018 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Explained part | Percent (%) | Explained part | Percent (%) | Explained part | Percent (%) | Explained part | Percent (%) | |

| Household income | 0.0066 | 8.18 | 0.0176** | 24.34 | 0.0193** | 33.22 | 0.0445** | 54.40 |

| Household size | −0.0242** | −29.99 | − 0.0177** | −24.48 | − 0.0208** | −35.80 | − 0.0135** | −16.50 |

| Inpatient, yes | − 0.0032 | −3.97 | 0.0040* | 5.53 | 0.0020 | 3.44 | 0.0034 | 4.16 |

| Household members aged<=5, yes | 0.0008 | 0.99 | 0.0009 | 1.24 | 0.0019 | 3.27 | 0.0005 | 0.61 |

| Household members aged> = 60, yes | 0.0020 | 2.48 | −0.0003 | − 0.41 | 0.0000 | 0.00 | 0.0029** | 3.55 |

| Geographic location | ||||||||

| East1 | ||||||||

| Central | −0.0003 | − 0.37 | 0.0011 | 1.52 | 0.0016 | 2.75 | 0.0001 | 0.12 |

| West | −0.0122* | −15.12 | −0.0089** | − 12.31 | − 0.0110** | − 18.93 | −0.0082* | − 10.02 |

| Gender of household head, male | 0.0005 | 0.62 | 0.0005 | 0.69 | 0.0025 | 4.30 | −0.0005 | −0.61 |

| Education of household head | ||||||||

| Illiterate1 | ||||||||

| Primary school | −0.0045* | −5.58 | −0.0052** | −7.19 | − 0.0024 | −4.13 | − 0.0023 | −2.81 |

| Middle school | 0.0052* | 6.44 | 0.0067** | 9.27 | 0.0040* | 6.88 | 0.0032 | 3.91 |

| High school and above | 0.0197* | 24.41 | 0.0117 | 16.18 | 0.0074 | 12.74 | 0.0030 | 3.67 |

| Marriage of household head, married | −0.0012 | −1.49 | 0.0007 | 0.97 | 0.0004 | 0.69 | 0.0000 | 0.00 |

| Self-assessed health status of household head, healthy | −0.0008 | − 0.99 | 0.0010 | 1.38 | 0.0031** | 5.34 | 0.0027** | 3.30 |

| Basic medical insurance | ||||||||

| No medical insurance1 | ||||||||

| UEBMI | −0.0179 | −22.18 | 0.0177 | 24.48 | − 0.0136 | −23.41 | 0.0142 | 17.36 |

| URBMI | −0.0029 | −3.59 | 0.0133 | 18.40 | 0.0012 | 2.07 | −0.0015 | −1.83 |

| NRCMS | 0.0451 | 55.89 | −0.0033 | −4.56 | 0.0266 | 45.78 | 0.0000 | 0.00 |

| Two kinds of medical insurance | – | – | – | – | −0.0001 | −0.17 | − 0.0007 | −0.86 |

| SMI, yes | −0.0007 | −0.87 | 0.0013 | 1.80 | 0.0010 | 1.72 | −0.0004 | −0.49 |

Note: 1 Reference group; UEBMI Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance, URBMI Urban Residents Basic Medical Insurance; NRCMS New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme; SMI Supplementary medical insurance; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01

Table 8.

Detailed decomposition of the urban-rural differences in CHE intensity among households with NCD patients

| Variables | 2012 | 2014 | ||||||

| Explained part | Percent (%) | Unexplained part | Percent (%) | Explained part | Percent (%) | Unexplained part | Percent (%) | |

| Household income | 0.0067** | 31.16 | 0.0183 | 85.12 | 0.0066** | 44.59 | 0.0121 | 81.76 |

| Household size | −0.0081** | −37.67 | −0.0146 | −67.91 | − 0.0059** | − 39.86 | −0.0116 | −78.38 |

| Inpatient, yes | 0.0001 | 0.47 | 0.0042 | 19.53 | 0.0012 | 8.11 | −0.0051 | −34.46 |

| Household members aged<=5, yes | −0.0006 | −2.79 | −0.0017 | −7.91 | − 0.0001 | −0.68 | 0.0027 | 18.24 |

| Household members aged> = 60, yes | 0.0008 | 3.72 | 0.0045 | 20.93 | 0.0001 | 0.68 | 0.0033 | 22.30 |

| Geographic location | ||||||||

| East1 | ||||||||

| Central | −0.0001 | −0.47 | −0.0024 | −11.16 | 0.0004 | 2.70 | −0.0048 | −32.43 |

| West | −0.0045** | −20.93 | −0.0048 | −22.33 | − 0.0044** | −29.73 | −0.0009 | −6.08 |

| Gender of household head, male | 0.0013* | 6.05 | −0.0026 | −12.09 | 0.0005 | 3.38 | 0.0006 | 4.05 |

| Education of household head | ||||||||

| Illiterate1 | ||||||||

| Primary school | −0.0014* | −6.51 | 0.0020 | 9.30 | −0.0016** | −10.81 | 0.0023 | 15.54 |

| Middle school | 0.0012* | 5.58 | 0.0041 | 19.07 | 0.0016** | 10.81 | 0.0034 | 22.97 |

| High school and above | 0.0035* | 16.28 | 0.0006 | 2.79 | 0.0043** | 29.05 | 0.0048 | 32.43 |

| Marriage of household head, married | −0.0001 | −0.47 | −0.0136 | −63.26 | − 0.0003 | −2.03 | −0.0207 | − 139.86 |

| Self-assessed health status of household head, healthy | −0.0003 | −1.40 | 0.0003 | 1.40 | 0.0002 | 1.35 | 0.0039 | 26.35 |

| Basic medical insurance | ||||||||

| No medical insurance1 | ||||||||

| UEBMI | 0.0015 | 6.98 | −0.0001 | −0.47 | 0.0004 | 2.70 | −0.0005 | −3.38 |

| URBMI | −0.0009 | −4.19 | −0.0005 | −2.33 | 0.0001 | 0.68 | −0.0011 | −7.43 |

| NRCMS | 0.0136 | 63.26 | −0.0062 | −28.84 | 0.0031 | 20.95 | 0.0026 | 17.57 |

| Two kinds of medical insurance | 0.0002 | 0.93 | −0.0001 | − 0.47 | 0.0002 | 1.35 | −0.0002 | −1.35 |

| SMI, yes | −0.0001 | −0.47 | 0.0003 | 1.40 | 0.0003 | 2.03 | −0.0001 | −0.68 |

| Constant | 0.0210 | 97.67 | 0.0174 | 117.57 | ||||

| Variables | 2016 | 2018 | ||||||

| Explained part | Percent (%) | Unexplained part | Percent (%) | Explained part | Percent (%) | Unexplained part | Percent (%) | |

| Household income | 0.0085** | 47.75 | 0.0227 | 127.53 | 0.0158** | 77.07 | −0.1813* | − 884.39 |

| Household size | −0.0063** | −35.39 | − 0.0043 | −24.16 | −0.0045** | −21.95 | − 0.0002 | −0.98 |

| Inpatient, yes | 0.0010 | 5.62 | 0.0056 | 31.46 | 0.0014 | 6.83 | 0.0056 | 27.32 |

| Household members aged<=5, yes | 0.0002 | 1.12 | 0.0006 | 3.37 | 0.0000 | 0.00 | −0.0002 | −0.98 |

| Household members aged> = 60, yes | 0.0000 | 0.00 | 0.0029 | 16.29 | 0.0008* | 3.90 | 0.0051 | 24.88 |

| Geographic location | ||||||||

| East1 | ||||||||

| Central | 0.0004 | 2.25 | −0.0056 | −31.46 | 0.0000 | 0.00 | 0.0057* | 27.80 |

| West | −0.0025** | −14.04 | −0.0062* | −34.83 | − 0.0023* | −11.22 | 0.0018 | 8.78 |

| Gender of household head, male | 0.0006 | 3.37 | 0.0016 | 8.99 | −0.0004 | −1.95 | −0.0083 | −40.49 |

| Education of household head | ||||||||

| Illiterate1 | ||||||||

| Primary school | −0.0015** | −8.43 | 0.0039 | 21.91 | −0.0013* | −6.34 | −0.0046 | −22.44 |

| Middle school | 0.0010* | 5.62 | 0.0014 | 7.87 | 0.0013* | 6.34 | −0.0004 | −1.95 |

| High school and above | 0.0049** | 27.53 | 0.0061* | 34.27 | 0.0036** | 17.56 | 0.0029 | 14.15 |

| Marriage of household head, married | 0.0000 | 0.00 | 0.0006 | 3.37 | 0.0000 | 0.00 | 0.0158 | 77.07 |

| Self-assessed health status of household head, healthy | 0.0008* | 4.49 | −0.0034 | −19.10 | 0.0008* | 3.90 | −0.0030 | −14.63 |

| Basic medical insurance | ||||||||

| No medical insurance1 | ||||||||

| UEBMI | 0.0006 | 3.37 | 0.0035 | 19.66 | 0.0038 | 18.54 | 0.0034 | 16.59 |

| URBMI | 0.0009 | 5.06 | 0.0015 | 8.43 | 0.0012 | 5.85 | 0.0012 | 5.85 |

| NRCMS | 0.0024 | 13.48 | 0.0234* | 131.46 | −0.0019 | −9.27 | 0.0060 | 29.27 |

| Two kinds of medical insurance | 0.0001 | 0.56 | 0.0004 | 2.25 | −0.0001 | −0.49 | 0.0006 | 2.93 |

| SMI, yes | 0.0003** | 1.69 | −0.0001 | −0.56 | − 0.0001 | −0.49 | 0.0003 | 1.46 |

| Constant | −0.0482 | −270.79 | 0.1520 | 741.46 | ||||

Note: 1 Reference group; OOP Out-of-pocket; UEBMI Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance; URBMI Urban Residents Basic Medical Insurance, NRCMS New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme, SMI Supplementary medical insurance; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01

With respect to the urban-rural differences in CHE incidence in 2012, the explained part was mainly attributed to household size (− 29.99%), geographic location (west, − 15.12%) and education of household head (primary school, − 5.58%; middle school, 6.44%; high school and above, 24.41%). The main contribution to the explained disparity in CHE incidence in 2018 was associated with household income (54.40%), household size (− 16.50%), having elderly members (3.55%), geographic location (west, − 10.02%), and self-rated health status of household head (3.30%).

With regard to the explained disparity of CHE intensity in 2012, the main contributors were household income (31.16%), household size (− 37.67%), geographic location (west, − 20.93%), gender of household head (6.05%), and education of household head (primary school, − 6.51%; middle school, 5.58%; high school and above, 16.28%). In 2018, the explained disparity in CHE intensity was mainly associated with household income (77.07%), household size (− 21.95%), having elderly members (3.90%), geographic location (west, − 11.22%), education of household head (primary school, − 6.34%; middle school, 6.34%; high school and above, 17.56%), and self-assessed health status of household head (3.90%).

Discussion

By analyzing the national representative unbalanced panel data collected between 2012 and 2018 from the CFPS, this study estimates the extent of CHE for urban and rural households with NCD patients, as well as the differences in the degree of CHE between the two groups.

Here, we found that the CHE incidence of households with NCD patients in urban and rural areas were 17.96 and 26.14%, respectively, which are much higher than the results of another study on the overall proportion of households incurring CHE in China (urban households: 13.06%; rural households: 17.70%) [17]. It indicates that the risk tolerance of households with NCD patients to OOP medical expenditure is lower than the average level of Chinese households. Our results also showed that the households with NCD patients had higher incidence and intensity of CHE in rural areas than in urban areas, demonstrating that rural households with NCD patients have higher risk of incurring CHE and heavier economic burden of diseases.

Using regression analysis to examine the relevant influencing factors for CHE incidence and intensity from 2012 to 2018, this research identified several key determinants reported in prior studies (e.g., household income, household size, having children below 5 years old, having elderly members, education of household head, receiving inpatient services in the last 12 months) [10, 22, 23, 37]. Specifically, higher annual household income per capita, larger household size and higher education level of household head protected against CHE in urban and rural households with NCD patients. Conversely, households utilizing inpatient services, having elderly members and with poor self-assessed health status of household head had higher risk of incurring CHE and heavier economic burden of diseases. Having children below 5 years old may increase the likelihood of incurring CHE for rural household with NCD patients. Meanwhile, this study found that the geographic location of west reduced the risk of incurring CHE and financial burden of diseases in urban and rural households with NCD patients. One potential explanation is that households in western China are prone to forgo needed health services due to their low income [38].

None of the three types of basic medical insurance schemes, including UEBMI, URBMI and NRCMS, significantly reduced the incidence and intensity of CHE in both two groups, which is consistent with some existing literature [11, 22, 39–41]. The weak effect of basic medical insurance in reducing the incidence and intensity of CHE could be attributed to the relatively lower level of scope and actual reimbursement rate, as well as the heavy economic burden of NCDs [23]. The analysis of individual database showed that the OOP medical expenditure as a percentage of total medical expenditure was greater than 40% for both urban and rural patients with NCDs covered by basic medical insurance from 2014 to 2018 (Supplementary Table 1).

Meanwhile, we also found that the NRCMS provided a lower level of health benefits for patients with NCDs compared to the UEBMI and URBMI (Table 4, Table 5 and Supplementary Table 1). Given the special nature of NCDs, local governments in China had established a special outpatient reimbursement system to compensate the medical expenses of patients with critical NCDs. According to the funding levels of the different basic medical insurance, the types of diseases to be included in the list were identified, the corresponding reimbursement rates and ceiling levels were set, and patients with critical NCDs were compensated. The statistical results showed that the per capita funding level of the NRCMS in 2018 was 654.6 CNY, which is lower than URBMI (695.7 CNY) and UEBMI (4273.2 CNY) [42]. This was the main reason why the groups covered by NRCMS were in a relatively disadvantaged position. In order to solve the above problems, relevant suggestions are shown as follows: (1) to strengthen the government’s responsibility for basic medical insurance schemes, especially for the NRCMS, (2) to gradually include more critical NCDs into the list of diseases for outpatient critical illnesses, and (3) to integrate different medical insurance schemes to break through the barriers between different basic medical insurance schemes.

As the supplementary form of basic health insurance, SMI usually reimbursed patients for medical expenses in the form of “secondary compensation”. Our research found that SMI could reduce the incidence and intensity of CHE to some extent, but its effect was not particularly stable in terms of statistical significance. Given that SMI is characterized by voluntary participation, one plausible reason for this phenomenon is the low coverage rate of SMI [43, 44]. The coverage rate of SMI in urban households with NCD patients increased from 0.90% in 2012 to 1.81% in 2018, while the coverage rate of SMI in rural households with NCD patients increased from 0.20% in 2012 to 0.89% in 2018 (Table 2). Therefore, this study deems that the Chinese government should encourage the development of SMI to form a multi-dimensional medical insurance system to further alleviate the financial burden of illness for patients with NCDs.

From 2012 to 2018, the increase of the explained disparity offset the reduction of the unexplained disparity, resulting in a slight increase of the urban-rural differences in the CHE incidence. During the same period, the reduction of the unexplained disparity offset the increase of the explained disparity, resulting in a slight decrease of the urban-rural differences in the CHE intensity.

More importantly, this article identified major contributors to explain the urban-rural differences in CHE incidence and intensity among households with NCD patients. Specifically, household income made the largest positive contribution to the urban-rural differences. From 2012 to 2018, the disparity explained by household income gradually increased, which can be attributed to the increase in the income gap between urban and rural households with NCD patients. Similarly, the education attainment and self-assessed health status of household head also had positive contribution. From 2012 to 2018, the contribution of education attainment to the urban-rural differences in CHE incidence decreased, while the contribution of education attainment to the urban-rural differences in CHE intensity increased slightly. During the same period, the contribution of self-assessed health status to the urban-rural differences in CHE incidence and intensity increased slightly. From the perspective of policymakers, any intervention aimed at decreasing this disparity may be effective if they focus on the observable characteristics mentioned above. The specific suggestions are as follows: (1) poverty alleviation department should resolutely implement “targeted poverty alleviation” strategy to effectively improve the income level of rural households with NCDs; (2) education department should promote the construction of rural education to improve the education level of rural population; (3) propaganda department should strengthen the publicity of NCDs in rural areas to raise the health awareness of rural patients with NCDs.

In addition, the observed characteristics such as household size and geographic location of the west area had an opposite effect in explaining the urban-rural differences. From 2012 to 2018, the contribution of above characteristics to the reduction of the urban-rural differences declined to some extent. If the urban-rural disparity is further reduced in terms of above characteristics, the urban-rural differences in CHE incidence and intensity will be wilder.

The decomposition results regarding the various types of medical insurance schemes were not satisfactory. SMI made minor contribution to the increase of urban-rural differences in CHE incidence and intensity, and its effect was not particularly stable in terms of statistical significance. None of the three types of basic medical insurance had a significant effect on the urban-rural differences in CHE incidence and intensity.

The study is not without its limitations. First, various characteristics (e.g., the levels of medical institution, actual reimbursement rate of medical insurance, distance to the nearest medical institution) can significantly affect CHE in the reports of other scholars [22, 23, 45]. However, the absence of relevant indicators in the database or the inconsistency in the caliber of indicators between different years lead to some unexplained urban-rural differences in incidence and intensity of CHE. Second, the present research uses a conservative method to estimate the OOP medical expenditure, resulting in indirect expenditure (e.g., transportation, food, accommodation, lost productivity due to illness) not being included [10, 29]. Therefore, we underestimated the CHE incidence and intensity to a certain extent. Third, since this study involves self-reported information about health status of household head, the possibility of reporting errors cannot be ruled out.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the present study suggested that rural households with NCD patients had higher CHE incidence and intensity than urban ones. None of the three types of basic medical insurance schemes significantly reduced the incidence and intensity of CHE in both two groups. In particular, NRCMS provided a lower level of health benefits for patients with NCDs compared to the UEBMI and URBMI. Furthermore, the urban-rural differences in CHE incidence slightly increased from 2012 to 2018, while the urban-rural differences in CHE intensity slightly decreased during the same period. By using the methods of Fairlie nonlinear decomposition and Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition, this research found that the household income, education and self-assessed health status of household head explained the urban-rural differences in CHE. From 2012 to 2018, the disparity explained by household income and self-assessed health status of household head increased to some extent. During the same period, the contribution of education attainment to the urban-rural differences in CHE incidence decreased, while the contribution of education attainment to the urban-rural differences in CHE intensity increased slightly. Policymakers should focus on strengthening the government’s responsibility for NRCMS, improving the household income, education attainment and health awareness of rural patients with NCDs.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Out-of-pocket medical expenditure as a percentage of total medical expenditure, China, 2014–2018

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank Ju Sun and Qiang Yao for their helpful suggestions and valuable comments.

Abbreviations

- CFPS

China Family Panel Studies

- CHE

Catastrophic health expenditure

- ISSS

Institute of Social Science Survey

- MPO

Mean positive overshoot

- NCDs

Chronic non-communicable diseases

- NRCMS

New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme

- OOP

Out-of-pocket

- PPS

Probability-proportional-to-scale

- SDGs

Sustainable Development Goals

- SMI

Supplementary Medical Insurance

- UEBMI

Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance

- URBMI

Urban Residents Basic Medical Insurance

Authors’ contributions

XZF formulated the primary framework of the study and contributed to the final manuscript. QWS conducted data analysis and made sufficient modifications according to the modification comments. FX conducted data analysis. JJH and CQS interpreted the results. All authors reviewed the manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study is supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China (Grant number: 15BSH043). The funders had no role in the design of this study, or data collection, analysis, and preparing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

This study was based on a publicly available database, the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS), which was conducted by the Institute of Social Science Survey (ISSS) of Peking University every 2 y from 2010 to 2018. This database was funded by Peking University and the Chinese National Natural Foundation. The original dataset can be obtained from the official website (see link: https://isss.pku.edu.cn/cfps/download/login). The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available for confidentiality reasons, but can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study is conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committees and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its subsequent revisions or similar ethical standards. Each volunteer participant obtained a written informed consent based on inclusion criteria.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Xian-zhi Fu, Email: 1371810134@qq.com.

Qi-wei Sun, Email: 2427057938@qq.com.

Chang-qing Sun, Email: zzugwsy@163.com.

Fei Xu, Email: xufeinanyang@163.com.

Jun-jian He, Email: hh510968@163.com.

References

- 1.Evans DB, Etienne C. Health systems financing and the path to universal coverage. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88(6):402. https://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/88/6/10-078741.pdf [published Online First: 2010/06]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Hogan DR, Stevens GA, Hosseinpoor AR, Boerma T. Monitoring universal health coverage within the Sustainable Development Goals: development and baseline data for an index of essential health services. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(2):e152-e168. https://www.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/langlo/PIIS2214-109X(17)30472-2.pdf [published Online First: 2017/12/13]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.World Health Organization-World Bank. Global Monitoring Report 2017: Tracking universal health coverage; 2019. https://www.emro.who.int/fr/media/advocacy-materials/who-world-bank-tracking-universal-health-coverage-2017-global-monitoring-report.html [published Online First: 2019/12/02].

- 4.Wang L, Kong L, Wu F, Bai Y, Burton R. Preventing Chronic Diseases in China. Lancet. 2005;366(9499):1821–1824. https://www.sas.upenn.edu/~dludden/ChronicDiseaseChina.pdf [published Online First: 2005/10/05]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.The National Health and Family Planning Commission of China The progress of disease prevention in China (in Chinese) Cap J Public Health. 2015;9(3):97–101. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reinhardt UE, Cheng TM. The world health report 2000 -- health systems: improving performance. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(8):1064. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guo Y, Shibuya K, Cheng G, Rao K, Lee L, Tang S. Tracking China's health reform. Lancet. 2010;375(9720):1056–1058. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673610603972 [published Online First: 2010/03/27]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Yip WCM, Hsiao WC, Chen W, Hu SL, Ma J, Maynard A. Early appraisal of China's huge and complex health-care reforms. Lancet. 2012;379(9818):833–842. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0140673611618801?via%3Dihub [published Online First: 2012/03/03]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Xu Y, Ma J, Wu N, Fan X, Zhang T, Zhou Z, Gao J, Ren J, Chen G. Catastrophic health expenditure in households with chronic disease patients: A pre-post comparison of the New Health Care Reform in Shaanxi Province, China. PLoS One. 2018;13(3):e0194539. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0194539&type=printable [published Online First: 2018/03/16]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Si YF, Zhou ZL, Su M, Wang X, Lan X, Wang D, Gong SQ, Xiao X, Shen C, Ren YL, et al. Decomposing inequality in catastrophic health expenditure for self-reported hypertension household in Urban Shaanxi, China from 2008 to 2013: two waves' cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(5):e023033. https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/bmjopen/9/5/e023033.full.pdf [published Online First: 2018/05]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Sun J, Lyu SJ. The effect of medical insurance on catastrophic health expenditure: evidence from China. Cost Effect Resourc Alloc. 2020;18(1):10. https://resource-allocation.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/s12962-020-00206-y [published Online First: 2018/02/27]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Hui-ping Wang, Zeng-tao Wang, Peng-cheng Ma. Situation analysis and thinking about poverty caused by illness in rural areas: Based on research data of 1214 families whose poverty is caused by illness in 9 Provinces in West China (in Chinese). Economist. 2016;(10):71–81. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFDLAST2016&filename=JJXJ201610010&v=DU9eMTweXEvqcskr0W7z6ciQDqxaD57T1bS86yrVl87albBxyV%25mmd2FWdTEVHH6d4r8Y [published Online First: 2016/10/05].

- 13.Fu XZ, Wang LK, Sun CQ, Wang DD, He JJ, Tang QX, Zhou QY. Inequity in inpatient services utilization: a longitudinal comparative analysis of middle-aged and elderly patients with the chronic non-communicable diseases in China. Int J Equit Health. 2020;19(1):6. https://equityhealthj.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/s12939-019-1117-9 [published Online First: 2016/01/06]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Zhang XY, Xu QQ, Guo XL, Jing ZY, Sun L, Li JJ, Zhou CC. Catastrophic health expenditure: a comparative study between hypertensive patients with and without complication in rural Shandong, China. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):545. https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/s12889-020-08662-0 [published Online First: 2020/04/22]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Lee M, Yoon K. Catastrophic Health Expenditures and Its Inequality in Households with Cancer Patients: A Panel Study. Processes. 2019;7(1):39. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330379346_Catastrophic_Health_Expenditures_and_Its_Inequality_in_Households_with_Cancer_Patients_A_Panel_Study [published Online First: 2019/01].

- 16.Gwatidzo SD, Williams JS. Diabetes mellitus medication use and catastrophic healthcare expenditure among adults aged 50+years in China and India: results from the WHO study on global AGEing and adult health (SAGE). BMC Geriatr. 2017;17:15. https://bmcgeriatr.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/s12877-016-0408-x [published Online First: 2017/01/11]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Zhao Y, Oldenburg B, Mahal A, Lin Y, Tang S, Liu X. Trends and socio-economic disparities in catastrophic health expenditure and health impoverishment in China: 2010 to 2016. Trop Med Int Health. 2020;25(2):236–247. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/tmi.13344 [published Online First: 2020/02]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Xie B, Huo MH, Wang ZQ, Chen YJ, Fu R, Liu MN, Meng Q. Impact of the New Cooperative Medical Scheme on the trend of catastrophic health expenditure in Chinese rural households: results from nationally representative surveys from 2003 to 2013. BMJ Open. 2018;8(2):e019442. https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/bmjopen/8/2/e019442.full.pdf [published Online First: 2018/05]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Ma XC, Wang ZY, Liu XY. Progress on Catastrophic Health Expenditure in China: Evidence from China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) 2010 to 2016. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(23):4775. https://apps.webofknowledge.com/full_record.do?product=UA&search_mode=GeneralSearch&qid=48&SID=8FQts7GJKzHJtP5qHyq&page=1&doc=1 [published Online First: 2019/12]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.O'Donnell O, Doorslaer E, Wagstaff A, Lindelow M. Analyzing Health Equity Using Household Survey Data: A Guide to Techniques and Their Implementation. 2008. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281905476_Analyzing_Health_Equity_Using_Household_Survey_Data_A_Guide_to_Techniques_and_Their_Implementation [published Online First: 2008/01].

- 21.Wagstaff A, Lindelow M. Can insurance increase financial risk? The curious case of health insurance in China. J Health Econ. 2008;27(4):990–1005. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/5509309_Can_Insurance_Increase_Financial_Risk_The_Curious_Case_of_Health_Insurance_in_China [published Online First: 2008/10]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Wang ZH, Li XJ, Chen MS. Catastrophic health expenditures and its inequality in elderly households with chronic disease patients in China. Int J Equit Health. 2015;14:8. https://equityhealthj.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/s12939-015-0134-6 [published Online First: 2015/01/20]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Si Y, Zhou Z, Su M, Ma M, Xu Y, Heitner J. Catastrophic healthcare expenditure and its inequality for households with hypertension: evidence from the rural areas of Shaanxi Province in China. Int J Equity Health. 2017;16:27. https://equityhealthj.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/s12939-016-0506-6 [published Online First: 2017/07/01]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Xu K, Evans DB, Kawabata K, Zeramdini R, Klavus J, Murray CJ. Household catastrophic health expenditure: a multicountry analysis. Lancet. 2003;362(9378):111–117. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673603138615 [published Online First: 2013/11]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Van Minh H, Kim Phuong NT, Saksena P, James CD, Xu K. Financial burden of household out-of pocket health expenditure in Viet Nam: findings from the National Living Standard Survey 2002–2010. Soc Sci Med. 2013;96:258–263. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0277953612007873 [published Online First: 2003/07/12]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Ahmadnezhad E, Murphy A, Alvandi R, Abdi Z. The impact of health reform in Iran on catastrophic health expenditures: Equity and policy implications. Int J Health Plann Manag. 2019;34(4):E1833-E1845. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/hpm.2900. [published Online First: 2019/10]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Kavosi Z, Rashidian A, Pourreza A, Majdzadeh R, Pourmalek F, Hosseinpour A, Mohammad K. Inequality in household catastrophic healthcare expenditure in a low-income society of Iran. Health Policy Plan. 2012;27(1):613–623. http://www.researchgate.net/publication/221779122_Inequality_in_household_catastrophic_health_care_expenditure_in_a_low-income_society_of_Iran [published Online First: 2012/10]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Arsenijevic J, Pavlova M, Rechel B, Groot W. Catastrophic Health Care Expenditure among Older People with Chronic Diseases in 15 European Countries. PloS One. 2016;11(7):e0157765. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0157765&type=printable [published Online First: 2016/07/05]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Lee JE, Shin HI, Do YK, Yang EJ. Catastrophic Health Expenditures for Households with Disabled Members: Evidence from the Korean Health Panel. J Korean Med Sci. 2016;31(3):336–344. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4779856/pdf/jkms-31-336.pdf [published Online First: 2016/03]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Blinder AS. Wage Discrimination - Reduced Form and Structural Estimates. J Hum Resour. 1973;8(4):436–455. doi: 10.2307/144855. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oaxaca R. Male-Female Wage Differentials in Urban Labor Markets. Int Econ Rev. 1973;14(3):693–709. https://inequality.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/media/_media/pdf/Reference%20Media/Oaxaca_1973_Discrimination%20and%20Prejudice.pdf [published Online First: 1973/10].

- 32.Fairlie RW. The absence of the African-American owned business: An analysis of the dynamics of self-employment. J Labor Econ. 1999;17(1):80–108. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/209914 [published Online First: 1999/01].

- 33.Fairlie R. An Extension of the Blinder-Oaxaca Decomposition Technique to Logit and Probit Models. J Econ Soc Measure. 2005;30(4):305–316. https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/28425 [published Online First: 2005/11].

- 34.Mehta H, Rajan S, Aparasu R, Johnson M. Application of the nonlinear Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition to study racial/ethnic disparities in antiobesity medication use in the United States. Res Soc Admin Pharm. 2012;9(1):13–26. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1551741112000332 [published Online First: 2013/01]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Jann B. A STATA implementation of the Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition. Stata J. 2008;8(4):453–479. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1536867X0800800401 [published Online First: 2008].

- 36.Oaxaca R, Ransom M. On Discrimination and the Decomposition of Wage Differentials. J Econ. 1994;61(1):5–21. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/222242826_On_Discrimination_and_the_Decomposition_of_Wage_Differentials [published Online First: 1994/03].

- 37.Xu Y, Gao J, Zhou Z, Xue Q, Yang J, Luo H, Li Y, Lai S, Chen G. Measurement and explanation of socioeconomic inequality in catastrophic health care expenditure: Evidence from the rural areas of Shaanxi Province. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:256. https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/s12913-015-0892-2 [published Online First: 2015/07/03]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Li Y, Wu Q, Liu C, Kang Z, Xie X, Yin H, Jiao M, Liu G, Hao Y, Ning N. Catastrophic Health Expenditure and Rural Household Impoverishment in China: What Role Does the New Cooperative Health Insurance Scheme Play? PloS One. 2014;9(4):e93253. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0093253 [published Online First: 2014/04/08]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Jiang CH, Ma JD, Zhang X, Luo WJ. Measuring financial protection for health in families with chronic conditions in Rural China. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:988. https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/1471-2458-12-988 [published Online First: 2012/11/16]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Liu H, Zhao Z. Impact of China's Urban Resident Basic Medical Insurance on Health Care Utilization and Expenditure. 2012. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/254928825_Impact_of_China's_Urban_Resident_Basic_Medical_Insurance_on_Health_Care_Utilization_and_Expenditure [published Online First: 2012/11].

- 41.Lei X, Lin W. The New Cooperative Medical Scheme in rural China: does more coverage mean more service and better health? Health Econ. 2009;18 Suppl 2:S25–S46. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/hec.1501 [published Online First: 2009/06/23]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China. China Health Statistics Yearbook. 2019; https://s2.51cto.com/oss/201912/05/1822362d5f7ccc8ff5d87ecdba23e64c.pdf [published Online First: 2019/12/05].

- 43.Dong K. Medical Insurance System Evolution in China. China Econ Rev. 2009;20(4):591–597. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1043951X09000753 [published Online First: 2009/12].

- 44.Li AQ, Shi YL, Yang X, Wang ZH. Effect of Critical Illness Insurance on Household Catastrophic Health Expenditure: The Latest Evidence from the National Health Service Survey in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(24):5086. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/338048048_Effect_of_Critical_Illness_Insurance_on_Household_Catastrophic_Health_Expenditure_The_Latest_Evidence_from_the_National_Health_Service_Survey_in_China [published online first: 2019/12/02]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Guo N, Iversen T, Lu MS, Wang J, Shi LW. Does the new cooperative medical scheme reduce inequality in catastrophic health expenditure in rural China? BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:653. https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/s12913-016-1883-7 [published Online First: 2016/11/14]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Out-of-pocket medical expenditure as a percentage of total medical expenditure, China, 2014–2018

Data Availability Statement

This study was based on a publicly available database, the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS), which was conducted by the Institute of Social Science Survey (ISSS) of Peking University every 2 y from 2010 to 2018. This database was funded by Peking University and the Chinese National Natural Foundation. The original dataset can be obtained from the official website (see link: https://isss.pku.edu.cn/cfps/download/login). The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available for confidentiality reasons, but can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.