Summary

Cell therapy using human-stem-cell-derived pancreatic beta cells (hSC-βs) is a potential treatment method for type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1D). For therapeutic safety, hSC-βs need encapsulation in grafts that are scalable and retrievable. In this study, we developed a lotus-root-shaped cell-encapsulated construct (LENCON) as a graft that can be retrieved after long-term hSC-β transplantation. This graft had six multicores encapsulating hSC-βs located within 1 mm from the edge. It controlled the recipient blood glucose levels for a long-term, following transplantation in immunodeficient diabetic mice. LENCON xenotransplanted into immunocompetent mice exhibited retrievability and maintained the functionality of hSC-βs for over 1 year after transplantation. We believe that LENCON can contribute to the treatment of T1D through long-term transplantation of hSC-βs and in many other forms of cell therapy.

Subject areas: Stem Cells Research, Cell Engineering, Biomaterials

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

A lotus-root-shaped cell-encapsulated construct as a retrieval graft

-

•

Advantages in terms of FBR mitigation and mechanical strength as a graft

-

•

Control the recipient blood glucose levels of NOD-Scid mice for up to half a year

-

•

Retrieval without adhesion over 1 year after transplantation

Stem Cells Research; Cell Engineering; Biomaterials.

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus affects over 400 million patients globally. It causes complications, such as kidney damage, visual impairment, and neuropathy. There are several treatments available for type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1D), such as daily injections of exogenous insulin (Hirsch 1999, Swinnen et al., 2009), pancreatic transplantation (Gruessner and Sutherland, 2005, Hampson et al., 2010), and cell therapy (McBane et al., 2013, Amer and Bryant, 2016, Ellis et al., 2013, Elliott et al., 2007, Bochenek et al., 2018). Cell therapy using human-stem-cell-derived pancreatic beta cells (hSC-βs) is attracting attention for donor-independent islet transplantation (Hogrebe et al., 2020, Rezania et al., 2014, Pagliuca et al., 2014, Yabe et al., 2019). In previous studies, transplantation was performed using encapsulated hSC-β grafts in mice and non-human primates (Agulnick et al., 2015, Vegas et al., 2016, Fukuda et al., 2019, Berman et al., 2016). A graft for clinical application should be scalable, for encapsulating many cells in a single piece and retrievable after transplantation, for therapeutic safety. Retrievable grafts should allow removal without adhesion and should be sufficiently strong to maintain their shape for a long time in vivo. Retrievable grafts of mouse and rat primary cells have been proposed (Onoe et al., 2013, Ma et al., 2013, Tomei et al., 2014, Watanabe et al., 2020); however, there is no report on hSC-β grafts that retain their function for a long time after transplantation. The previous grafts encapsulating hSC-βs induced intense foreign-body responses (FBRs), compared to those encapsulating human primary islets (Torren et al., 2017), resulting in fibrotic deposition, adhesion, nutrient isolation, and cell death.

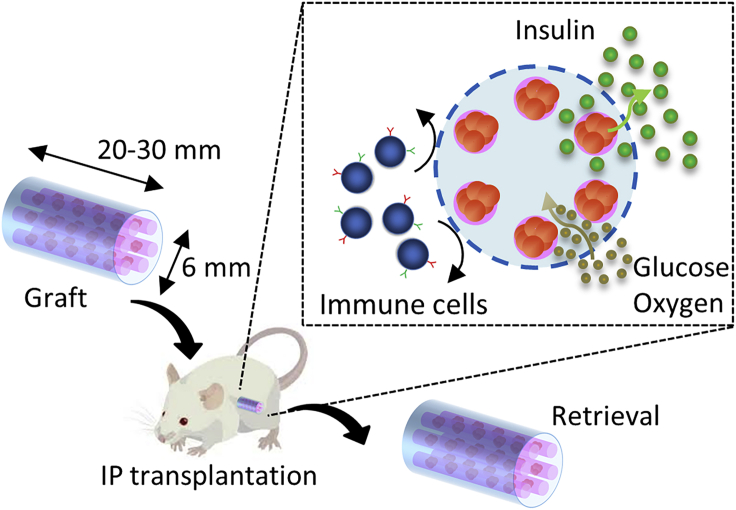

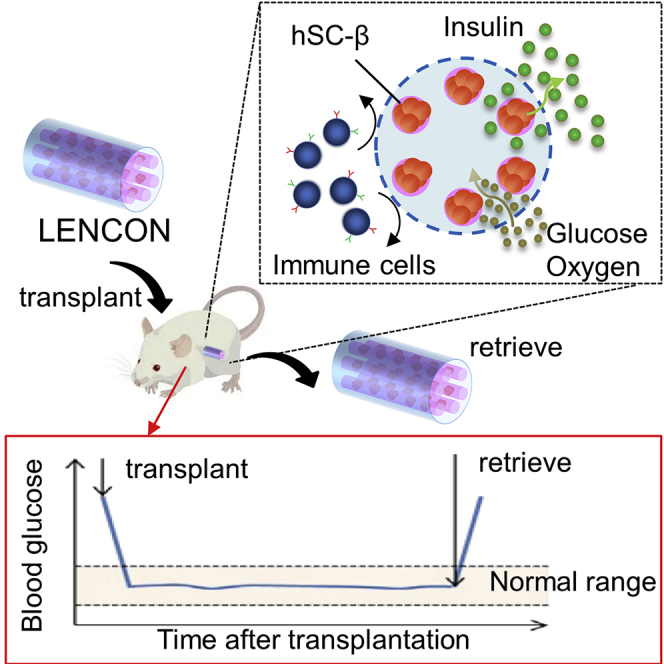

In this study, we develop a lotus-root-shaped cell-encapsulated construct (LENCON) as a graft that can be retrieved after long-term (>1 year) hSC-β transplantation. Figure 1 shows the structure of the proposed LENCON with millimeter-thickness. Grafts with millimeter-thickness tend to mitigate FBR (Watanabe et al., 2020, Veiseh et al., 2015), as well as exhibit higher mechanical strength. The cells are placed near the edge of the lotus-root-shaped graft structure to support cell survival. When the diameter of the graft is in the order of millimeters or more, the diffusion of oxygen and nutrients from the surrounding hydrogel throughout the encapsulated cells is limited resulting in cell death in the center of the hydrogel (Li et al., 1995, Weaver et al., 2018, Buchwald et al., 2018). In addition, this graft is scalable in the direction of the long axis; and therefore, the number of cells can be increased. Here, we fabricate LENCON and evaluate the survival of the encapsulated cells. We then transplant the grafts into mice and characterize cell function, graft strength, and retrievability.

Figure 1.

Concept of LENCON transplantation

Results

Optimization of LENCON

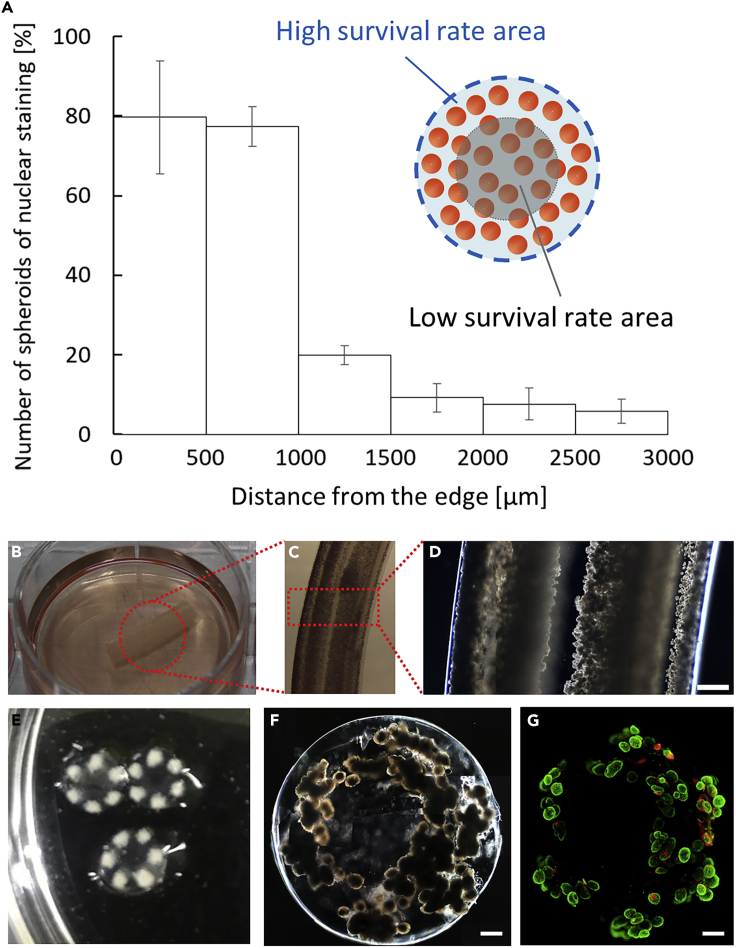

For millimeter-thick fiber-encapsulation of cells, we employed a lotus-root like geometry, in which cells are placed near the edges of the grafts, enabling cell survival, and are covered by a Ba-alginate hydrogel shell. To determine the cell position from the edge, we fabricated 6-mm-thick fibers encapsulating hSC-βs with randomized cell positions in the hydrogel. After a 1-week culture, we prepared hematoxylin and eosin (HE)-stained sections of the 6-mm-thick fibers and estimated the survival ratio by dividing the number of enucleated cells by the total number of cells in the HE sections. The live cell area was calculated as the cell area obtained by subtracting the area occupied by enucleated cells from the area occupied by all stained cells; we postulated that cells without enucleation are viable cells. The cells within 1 mm from the edge of the fabricated LENCON maintained 80% ± 12% nuclear staining, while the cells over 1 mm from the edge exhibited significantly increased enucleation (Figure 2A), suggesting that most cells within 1 mm from the edge were viable cells.

Figure 2.

Formation of LENCON

(A) Survival of hSC-βs in a 6-mm-thick hydrogel after one week of culture.

(B) Optical images of the long axis direction of the 6-mm-thick LENCON.

(C and D) Microscopic images of the long axis direction of the 6 mm-thick LENCON.

(E) Optical images of the short axis direction of the 6-mm-thick LENCON.

(F) Microscopic images of the 6-mm-thick LENCON. (Scale bar: 500 μm).

(G) Fluorescent staining images of 6-mm-thick LENCON stained with calcein-AM and propidium iodide. (Scale bar: 500 μm)

Using a fluidic device, LENCON was fabricated, as shown in the transparent methods section (Figure S1) and Video S1. The LENCON had a diameter of 6 mm and six multicores encapsulating hSC-βs (Figures 2B–2E). Each core had a diameter of 600–700 μm and was located within 1 mm from the edge (Figure 2F). The live/dead fluorescent staining (Figure 2G) indicated that most of the stained hSC-βs in LENCON were viable before transplantation. Moreover, immunofluorescence images revealed that human C-peptide-positive cells were present even after encapsulation (Figure S2). These results suggested that the encapsulation process was sufficient to maintain hSC-β survival and function.

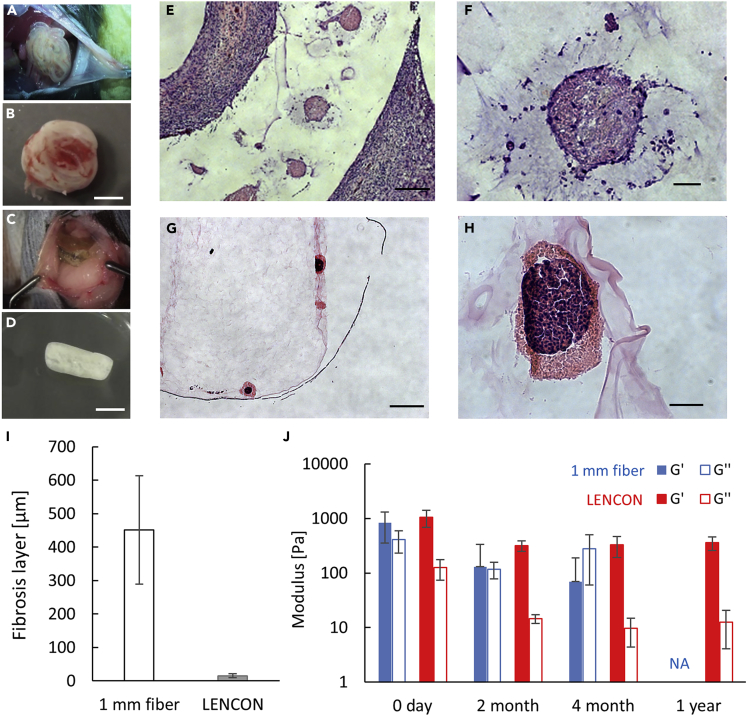

Effect of graft size on FBR and mechanical stability in immunocompetent mice

To investigate the effects of the size of graft encapsulating hSC-βs, we compared the FBR based on the degree of cell deposition in the graft, and the adhesion between the host tissue and graft. We prepared 1-mm-thick grafts and 6-mm-thick LENCONs. Each graft was transplanted into immunocompetent C57BL/6 mice and retrieved after 2 months, 4 months, and 1 year. Four months after transplantation, the 1-mm-thick graft exhibited intense cell deposition and adhesion to the recipient mouse tissue (Figures 3A, 3B, and 3E); it was retrieved with peeling off at the adhesion site (Figure 3B). In contrast, the 6-mm-thick LENCON did not exhibit intense cell deposition (Figure 3C) and could be retrieved without obvious adhesion (Figure 3D). We compared the thickness of the cell deposition using images of HE-stained sections (Figures 3E–3H). The 1-mm-thick grafts were surrounded by an approximately 400-μm-thick cell deposition (Figures 3E and 3I), while the 6-mm-thick LENCON was only partially covered by cells, with a deposition as thin as 20 μm (Figures 3F and 3I). The degree of cell deposition also affects the survival of encapsulated cells; the hSC-βs in the 1-mm-thick grafts were enucleated and dead (Figure 3F), while those in the 6-mm-thick LENCONs retained their nuclei and were viable (Figure 3H). These results indicate that the 6-mm-thick LENCONs provide an appropriate microenvironment to hSC-βs during transplantation.

Figure 3.

Evaluation of fibrosis formation and mechanical strength of grafts

(A) Second-look laparotomy of the mice transplanted with 1-mm-thick grafts. The 1 mm-thick grafts adhered to the recipient mice.

(B) Retrieved 1-mm-thick grafts. The grafts were covered with thick cell layers.

(C) Second-look laparotomy of the recipient mice transplanted with 6-mm-thick LENCONs. The 6-mm-thick grafts did not obviously adhere to the recipient mice.

(D) Retrieved 6-mm-thick LENCONs. The grafts were partially deposited with thin cell layers.

(E) HE-stained sectional image of retrieved 1-mm-thick grafts.

(F) Enlarged HE-stained sectional image of retrieved 1-mm-thick grafts.

(G) HE-stained sectional image of retrieved 6-mm-thick LENCONs.

(H) Enlarged HE-stained sectional image of retrieved 6 mm-thick LENCONs. Scale bars: (E, G) 1 mm, (F, H) 50 μm. Time points of images a-h, 4 months after transplantation.

(I) Comparison of fibrosis layer deposition.

(J) Rheological measurements of the each retrieved graft. (NA: The 1-mm-thick grafts 1 year after transplantation were too fragile to be retrieved.)

To evaluate the changes in mechanical stability of the graft before and after transplantation, we measured the elastic modulus of each graft using a rheometer (Figure 3J). Both the 1-mm- and 6-mm-thick grafts showed similar elastic modulus before transplantation. However, after transplantation, the 1-mm-thick graft exhibited a significantly reduced elastic modulus, and its storage modulus became lower than the loss modulus, indicating that the state of the graft changed from gel to sol after 4 months of transplantation. After 1 year of transplantation, the 1-mm-thick grafts were too fragile to be retrieved, and we were unable to perform a rheological analysis. In contrast, the elastic modulus of the 6-mm-thick grafts decreased slightly in the beginning but showed negligible decrease after 2 months, and the storage modulus was higher than the loss modulus, indicating that the grafts maintained the gel-state after 2 months, 4 months, and 1 year of transplantation.

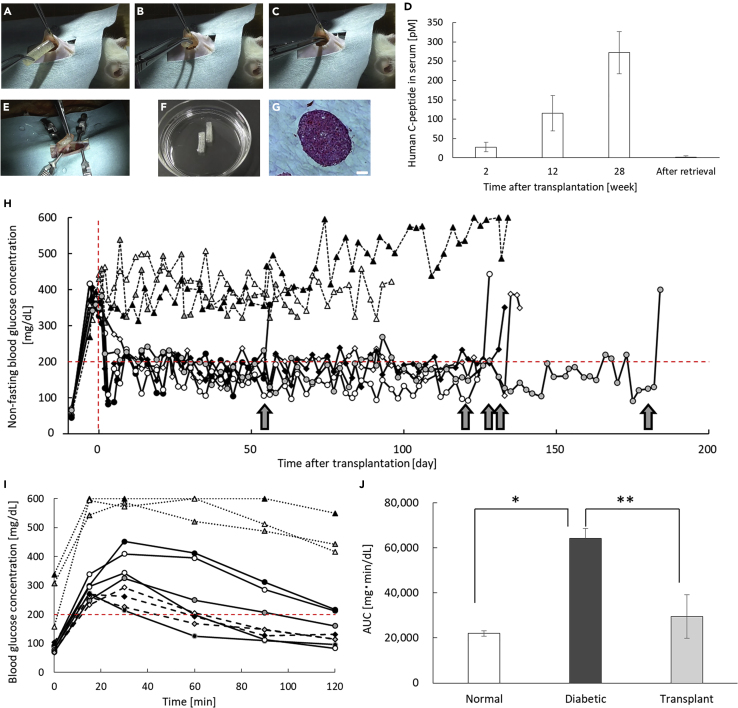

Long-term transplantation of LENCON in immunodeficient mice

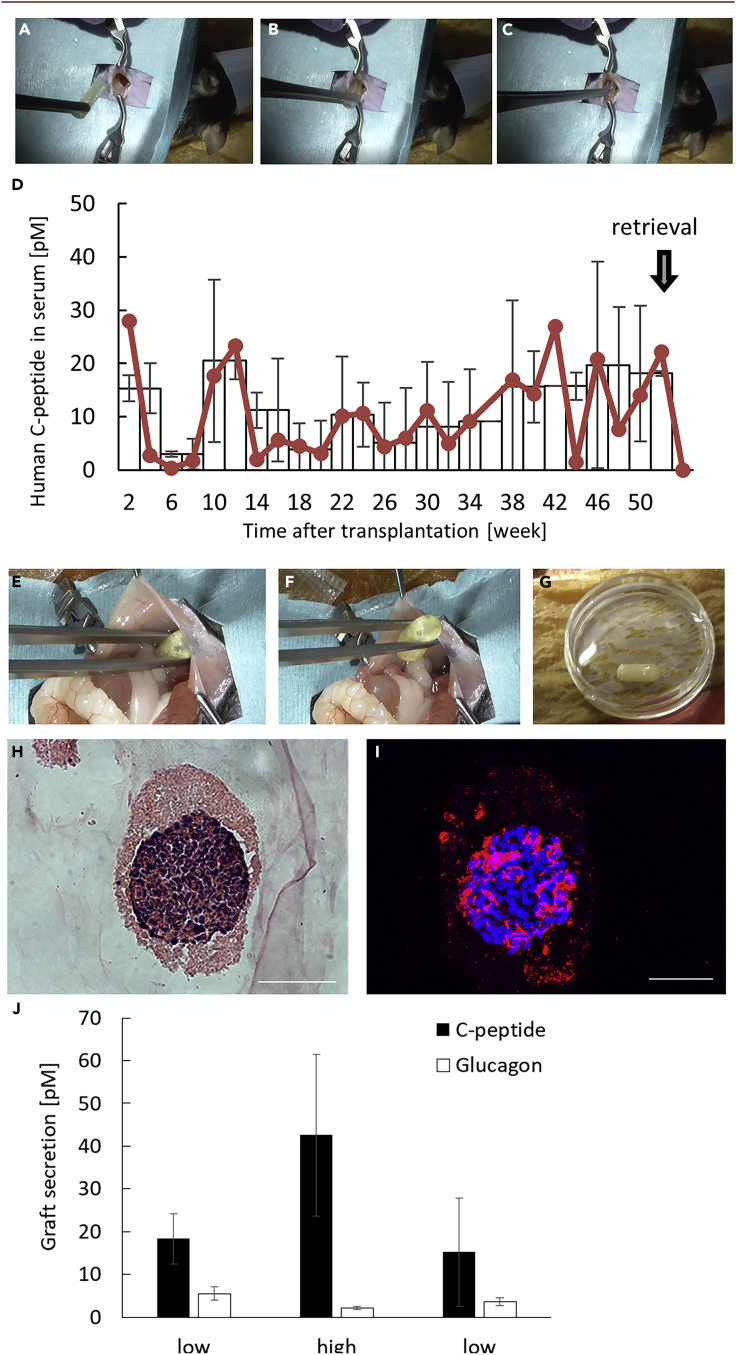

To confirm the in vivo functionality of LENCON encapsulating hSC-βs (6×106 cells) with reduced transplant rejection, we transplanted the LENCONs into the intraperitoneal space of normal immunodeficient NOD-Scid mice (Figures 4A–4C and Video S2). After transplantation, the human C-peptide concentration in blood gradually increased (Figure 4D), as in the case of the 1 mm-thick graft (Figure S3), suggesting that the hSC-βs in the LENCON were functional during transplantation. We performed second-look laparotomy and retrieved the grafts after over 28 weeks of transplantation (Video S3). All grafts appeared intact in the recipient's abdominal cavities without adhesion to the recipient's adjacent abdominal tissues (Figure 4E). In addition, the grafts could be retrieved from the intraperitoneal space of the recipients (Figure 4F). The retrieved grafts had viable hSC-βs (Figures 4G and S4), while the 1-mm-thick grafts encapsulating hSC-βs were broken into pieces in the intraperitoneal space and could not be retrieved completely (Figure S5).

Figure 4.

In vivo demonstration of therapeutic potential of the LENCON using NOD-Scid mice

(A–C) Laparotomy of transplantation of the LENCON.

(D) ELISA results of blood samples of the recipient mice.

(E) Second-look laparotomy for retrieval of the LENCON.

(F) Optical image of retrieved LENCON.

(G) HE-stained sectional image of hSC-βs in the retrieved LENCONs. (Scale bar: 50 μm).

(H) Changes in the non-fasting blood glucose concentration of mice transplanted with the LENCONs (solid line: LENCON transplantation, N = 5, dotted line: non-transplantation, N = 3). The transplanted grafts in the intraperitoneal cavities were retrieved at the timepoints indicated by the arrows (days 54, 120, 127, 131, and 180).

(I) Oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) results of recipient mice 7 days before retrieval (solid line: recipient mice with LENCON transplantation, N = 5, dotted line: diabetic mice without transplantation, N = 3, dashed line: normal mice, N = 3).

(J) The area under curve of the plasma glucose concentrations during OGTT of recipient mice (N = 3).

To demonstrate the glycemic control potential, we measured the blood glucose levels of the recipient streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic mice daily after transplantation of the LENCON. We hypothesized that the glycemic control in the recipient mice is highly correlated with the functions of hSC-βs. We transplanted LENCON encapsulating hSC-βs into the intraperitoneal space of STZ-induced diabetic mice and monitored their non-fasting blood glucose concentrations (Figure 4H). The recipients with LENCON transplantation exhibited normoglycemia within 10 days post-transplantation. Subsequently, the recipient mice with transplanted LENCONs maintained normoglycemia, while all recipient mice without the grafts were hyperglycemic. In addition, the glucose tolerance levels of LENCON-transplanted mice were comparable to those of normal mice even after 100 days of transplantation (Figures 4I and 4J). We performed second-look laparotomy and retrieved the grafts after 56 days, 120 days, 130 days, 136 days, and 180 days of transplantation. All grafts appeared intact in the recipient's abdominal cavities without adhesion to the recipient's adjacent abdominal tissues similar to non-diabetic mice. In addition, the grafts could be retrieved from the intraperitoneal space of the recipients, which resulted in the reappearance of hyperglycemia in the recipients. The retrieved grafts were evaluated using a glucose-stimulated insulin secretion assay, and their functionalities before and after transplantation were compared (Figure S6). LENCONs encapsulating hSC-βs maintained their function of controlling the blood glucose concentration even after transplantation and retrieval.

Long-term xenotransplantation of LENCON in immunocompetent mice

To evaluate whether the LENCONs can be transplanted for a long duration, while maintaining intact immune systems, we transplanted LENCONs encapsulating hSC-βs into the intraperitoneal space of immunocompetent C57BL/6 mice (Figures 5A–5C). After 1 year of transplantation, we performed second-look laparotomy and retrieved the grafts (Figures 5E and 5G). Nine out of the ten LENCONs transplanted were successfully retrieved without adhesion to the recipient's adjacent abdominal tissues (Video S4). The retrieved LENCONs remained intact, although some parts of the graft exhibited a thin cell layer and the edge was slightly rounded (Figure 5G). No tumor formation was observed in the recipient mice due to cell leakage. These results suggest that LENCONs exhibit retrievability and therapeutic safety even in immunocompetent mice.

Figure 5.

Long-term transplantation of LENCON into immunocompetent C57BL/6 mice

(A–C) Laparotomy of transplantation of the LENCON.

(D) ELISA results of blood samples of recipient mice.

(E and F) Second-look laparotomy for retrieval of the LENCON.

(G) Optical image of retrieved LENCON.

(H) HE-stained sectional images of hSC-β in the retrieved LENCON. (Scale bar: 50 μm).

(I) Fluorescent images of hSC-β in the retrieved LENCON stained for C-peptide. (Scale bar: 50 μm).

(J) Glucose responsive test of the retrieved LENCONs.

During the transplantation period, we collected blood of the recipient mice every two weeks and measured the levels of human C-peptide using ELISA. The human C-peptide levels in blood were intermittently detected over the 50-week transplantation period (Figure 5D). The retrieved LENCON sustained the human C-peptide-positive hSC-βs as indicated through HE and immunostaining (Figures 5H and 5I). In addition, the encapsulated cells expressed other islet markers (Figure S7). Following the glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) assay (Figure 5J); both human C-peptide and glucagon were secreted in response to the glucose stimulation, indicating that functional hSC-βs survived in the LENCONs for more than 1 year. These results corroborate that our LENCON has a high potential for long-term xenotransplantation of functional hSC-βs.

Discussion

In this study, we developed 6 mm-thick LENCONs for long-term transplantation, which had six multicores encapsulating hSC-βs located within 1 mm from the edge. The LENCON transplanted into immunodeficient mice controlled the recipient blood-glucose concentration for a period of 180 days after transplantation. The LENCON xenotransplanted into immunocompetent mice maintained retrievability and hSC-β functionality for over a year after transplantation.

Recently, it was reported that hydrogel capsules larger than 1-mm-thick tend to mitigate FBR (Watanabe et al., 2020, Veiseh et al., 2015). In our experiment, however, when 1-mm-thick grafts encapsulating hSC-βs were transplanted into mice, the grafts showed intense FBR. This result is possibly due to the considerable difference between mice and humans; hSC-βs induce severe inflammation than the previously used cells (e.g., mouse/rat primary islets). We found that the 6-mm-thick LENCON tended to mitigate FBR even when encapsulating hSC-βs. We did not elucidate the mechanism through which larger grafts mitigate FBR; however, the relationship between graft size and macrophage functions may help us understand this interesting phenomenon. Millimeter order grafts are surrounded by only a few macrophages, resulting in reduced recruitment and extravasation of additional macrophages (Vegas et al., 2016, Veiseh et al., 2015). In the case of hSC-βs, a thickness of 1 mm was presumably not sufficient to prevent macrophage recruitment, but a thickness of 6 mm was. This fact could lead to a design concept, larger thickness is better to mitigate FBR, while it may increase the burden on the host recipients. Therefore, our results strongly suggest that there may be an optimal graft size depending on the encapsulated cells and host animals.

The 6 mm-thick LENCONs have advantages in terms of mechanical strength over the thinner LENCONs. In case of thin fibers, the fibers bend easily and they are eventually entangled after the transplantation; this increase in the shape complexity may promote cell deposition on the surface of the graft. In contrast, the 6-mm-thick LENCONs do not bend in vivo because of the increased mechanical strength, thereby mitigating cell deposition. In addition, it is known that the cell deposition can be mitigated by modifying the alginate (Liu et al., 2019, Yang et al., 2019) and other chemicals (Doloff et al., 2017, Farah et al., 2019, Alagpulinsa et al., 2019, Kikawa et al., 2014). Combining these materials with mechanically strong LENCONs will provide more inert grafts.

In addition to influencing FBR, increase in the graft size influences cell survival; cells may die, as nutrients and oxygen do not reach the encapsulated cells located at the center of the grafts, resulting in the dysfunction of the graft. We showed that the hSC-βs encapsulated within 1 mm from the edge of the graft could receive sufficient supply oxygen and nutrients during transplantation. The lotus-root-like geometry of our LENCON enables adequate supply of oxygen and nutrients to the encapsulated cells near the edge of the graft, despite the larger size of the graft. The levels of C-peptide at 12 weeks post-transplantation did not exhibit a significant difference between the control 1 mm graft and the LENCON. This indicates that insulin secretion from the LENCON was sufficient as comparable to the previously reported encapsulation devices (Fukuda et al., 2019). In addition, by modifying the graft to be hollow in the center, it will be possible to supply oxygen and nutrients from the edges to the center and enhance the graft functions.

More cells than those required for transplantation into mice need to be encapsulated for clinical transplantation in humans (Park et al., 2015, Sphapiro et al., 2006). Scaling up the number of cells would be problematic when using hydrogel beads, in terms of retrievability. Ensuring complete retrieval of the hydrogel beads is challenging because of the large capsule numbers and the complicated organ structures of the abdominal cavity. However, our LENCON could be scaled up as one graft by increasing the number of cores and the length of the graft, and thereby improving the retrievability of the grafts.

For cell therapy using stem cell-derived cells, the long-term graft functions and the therapeutic safety need to be considered. First, in long-term transplantation, the LENCON encapsulating hSC-βs can control the blood glucose concentrations of recipient mice with deficient immune systems. The increase in blood C-peptide production during transplantation suggests that the encapsulated hSC-βs became more mature in vivo; this result is consistent with that reported by recent studies on hSC-β transplantations (Rezania et al., 2014, Pagliuca et al., 2014, Yabe et al., 2019, Fukuda et al., 2019). Challenges remain in controlling the blood glucose concentration, considering the large species difference; however, the LENCONs represent a major advancement in cell therapy in terms of the survival of encapsulated hSC-βs and their retrievability over 1 year after transplantation in immunocompetent mice. Macrophages and activated fibroblasts, which promote inflammation and fibrosis, were attached to a part of the graft surface after long-term transplantation, as observed through immunofluorescent staining (Figure S8). These cells might cause FBR and induce a decline in graft function (Veiseh et al., 2015, Watanabe et al., 2020). We believe that optimizing the structure of the graft and replacing the hydrogel with a more hydrophilic material may mitigate such cell deposition. Second, our study shows that the LENCONs are therapeutically safe because no apparent tumor formation was observed in the host recipient mice, and these grafts can be used in other stem-cell-derived endocrine cell transplantations, such as hypophysis and thyroid transplantation. The LENCON encapsulating hSC-βs can be a powerful tool with minimal risks for the treatment of T1D and can be potentially used in several other forms of cell therapy that require graft retrievability.

Limitations of the study

Some limitations of this study must be acknowledged. In human clinical application, the encapsulated cells in the graft should be more, around 500,000 IEQ of human primary islets. The functionality of hSC-βs is inferior to that of human primary islets, and a larger number of hSC-βs are required. It is expected that the required number of cells in a LENCON will be similar to that required for human primary islets, considering the improved function of hSC-βs. The LENCON should be optimized for human applications by increasing the number of cores, their diameter, and the length of the graft. Host FBR to the graft are another limitation. The alginate hydrogel does not completely mitigate FBR and cannot completely control the blood glucose levels of immunocompetent mice. A zwitterionically modified alginate hydrogel and other chemicals that reduce inflammatory effects could alleviate this problem. The alginate hydrogel could be replaced with a hydrophilic hydrogel exhibiting low protein adsorption affinity.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Shoji Takeuchi (takeuchi@hybrid.t.u-tokyo.ac.jp).

Materials availability

Not applicable.

Data and code availability

Not applicable.

Methods

All methods can be found in the accompanying transparent methods supplemental file.

Acknowledgments

We thank H. Aoyagi and A. Takimoto for their assistance with the maintenance of diabetic mice, measurement of daily blood glucose concentrations, and preparation of the frozen sections of grafts. We also thank T. Saito for assistance with the fabrication of fluidic devices and LENCONs. This work was partly supported by Research Center Network for Realization of Regenerative Medicine (19bm0304005h0007), Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED), Japan, and Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (S) (Grant number: 16H06329) and Grant-in-Aid for Early-Career Scientists (Grant number: 19K20664) Japan Science and Technology (JST), Japan.

Author contributions

F. Ozawa and S. Takeuchi conceived the design of the study. F. Ozawa fabricated the fluidic devices and grafts. F. Ozawa and S. Nagata designed and conducted graft transplantation experiments in mice. H. Oda measured the elastic modulus of grafts. S. Yabe and H. Okochi prepared the hSC-βs. F. Ozawa analyzed the grafts via microscopy observations of HE sections. S. Nagata analyzed the grafts through confocal microscopy and recorded the immunofluorescent images. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

S. Takeuchi is an inventor on intellectual property rights related to the cell fiber technology, and stockholders of Cellfiber Inc, a start-up company based on the cell fiber technology. However, any authors are NOT employed by the commercial company: Cellfiber Inc. Thus, this does not alter our adherence to iScience policies on sharing data and materials.

Published: April 1, 2021

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2021.102309.

Supplemental information

References

- Agulnick A.D., Ambruzs D.M., Moorman M.A., Bhoumik A., Cesario R.M., Payne J.K., Kelly J.R., Haakmeester C., Srijemac R., Wilson A.Z. Insulin-Producing endocrine cells differentiated in vitro from human embryonic stem cells function in macroencapsulation devices in vivo. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2015;4:1214–1222. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2015-0079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alagpulinsa D.A., Cao J.J.L., Driscoll R.K., Sîrbulescu R.F., Penson M.F.E., Sremac M., Engquist E.N., Brauns T.A., Markmann J.F., Melton D.A., Poznansky M.C. Alginate microencapsulation of human stem cell-derived beta cells with CXCL12 prolongs their survival and function in immunocompetent mice without systemic immunosuppression. Am. J. Transpl. 2019;19:1930–1940. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amer L.D., Bryant S.J. The in vitro and in vivo response to MMP-sensitive poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2016;44:1959–1969. doi: 10.1007/s10439-016-1608-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman D.M., Molano R.D., Fotino C., Ulissi U., Gimeno J., Mendez A.J., Kenyon N.M., Kenyon N.S., Andrews D.M., Ricordi C., Pileggi A. Bioengineering the endocrine pancreas: intraomental islet transplantation within a biologic resorbable scaffold. Diabetes. 2016;65:1350–1361. doi: 10.2337/db15-1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bochenek M.A., Veiseh O., Vegas A.J., McGarrigle J.J., Qi M., Marchese E., Omami M., Doloff J.C., Mendoza-Elias J., Nourmohammadzadeh M. Alginate encapsulation as long-term immune protection of allogeneic pancreatic islet cells transplanted into the omental bursa of macaques. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2018;2:810–821. doi: 10.1038/s41551-018-0275-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchwald P., Tamayo-Garcia A., Manzoli V., Tomei A.A., Stabler C.L. Glucose-stimulated insulin release: parallel perifusion studies of free and hydrogel encapsulated human pancreatic islets. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2018;115:232–245. doi: 10.1002/bit.26442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doloff J.C., Veiseh O., Vegas A.J., Tam H.H., Farah H., Ma M., Li J., Bader A., Chiu A., Sadraei A., Dasilva S.A. Colony stimulating factor-1 receptor is a central component of the foreign body response to biomaterial implants in rodents and non-human primates. Nat. Mat. 2017;16:671–680. doi: 10.1038/nmat4866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott R.B., Escobar L., Tan P.L., Muzina M., Zwain S., Buchanan C. Live encapsulated porcine islets from a type 1 diabetic patient 9.5 yr after xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2007;14:157–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2007.00384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis C.E., Vulesevic B., Suuronen E., Yeung T., Seeberger K., Korbutt G.S. Bioengineering a highly vascularized matrix for the ectopic transplantation of islets. Islets. 2013;5:216–225. doi: 10.4161/isl.27175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farah S., Doloff J.C., Müller P., Sadraei A., Han H.J., Olafson K., Vyas K., Tam H.H., Hollister-Lock J., Kowalski P.S. Long-term implant fibrosis prevention in rodents and non-human primates using crystallized drug formulations. Nat. Mater. 2019;18:892–904. doi: 10.1038/s41563-019-0377-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda S., Yabe S.G., Nishida J., Takeda F., Nashiro K., Okochi H. The intraperitoneal space is more favorable than the subcutaneous one for transplanting alginate fiber containing iPS-derived islet-like cells. Regen. Ther. 2019;11:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.reth.2019.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruessner A.C., Sutherland D.E. Pancreas transplant outcomes for United States (US) and non-US cases as reported to the united Network for organ sharing (UNOS) and the international pancreas transplant registry (IPTR) as of June 2004. Clin. Transpl. 2005;19:433–455. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2005.00378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson F.A., Freeman S.J., Ertner J., Drage M., Butler A., Watson C.J., Shaw A.S. Pancreatic transplantation: surgical technique, normal radiological appearances and complications. Insights Imaging. 2010;1:339–347. doi: 10.1007/s13244-010-0046-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch I.B. Type 1 diabetes mellitus and the use of flexible insulin regimens. Am. Fam. Physician. 1999;60:2343–2346. https://www.aafp.org/afp/1999/1115/p2343.html [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogrebe N.J., Augsornworawat P., Maxwell K.G., Velazco-Cruz L., Millman J.R. Targeting the cytoskeleton to direct pancreatic differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020;38:460–470. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0430-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikawa K., Sakano D., Shiraki N., Tsuyama T., Kume K., Endo F., Kume S. Beneficial effect of insulin treatment on islet transplantation outcomes in akita mice. PLoS One. 2014;9:e95451. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R.H., Altreuter D.H., Gentile F.T. Transport characterization of hydrogel matrices for cell encapsulation. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1995;50:365–373. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(19960520)50:4<365::AID-BIT3>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q., Chiu A., Wang L.H., An D., Zhong M., Smink A.M., de Haan B.J., de Vos P., Keane K., Vegge A. Zwitterionically modified alginates mitigate cellular overgrowth for cell encapsulation. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:5262. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13238-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma M., Chiu A., Sahay G., Doloff J.C., Dholakia N., Thakrar R., Cohen J., Vegas A., Chen D., Bratlie K.M. Core-shell hydrogel microcapsules for improved islets encapsulation. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2013;2:667–672. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201200341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBane J.E., Vulesevic B., Padavan D.T., McEwan K.A., Korbutt G.S., Suuronen E.J. Evaluation of a collagen-chitosan hydrogel for potential use as a pro-angiogenic site for islet transplantation. PLoS One. 2013;8:e77538. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onoe H., Okitsu T., Itou A., Kato-Negishi M., Gojo R., Kiriya D., Sato K., Miura S., Iwanaga S., Kuribayashi-Shigetomi K. Metre-long cell-laden microfibres exhibit tissue morphologies and functions. Nat. Mater. 2013;12:584–590. doi: 10.1038/nmat3606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagliuca F.W., Millman J.R., Gürtler M., Segel M., Van Dervort A., Ryu J.H., Peterson Q.P., Greiner D., Melton D.A. Generation of functional human pancreatic β cells in vitro. Cell. 2014;159:428–439. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park C.G., Bottino R., Hawthorne W.J. Current status of islet xenotransplantation. Int. J. Surg. 2015;23:261–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.07.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezania A., Bruin J.E., Arora P., Rubin A., Batushansky I., Asadi A., O'Dwyer S., Quiskamp N., Mojibian M., Albrecht T. Reversal of diabetes with insulin-producing cells derived in vitro from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014;32:1121–1133. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sphapiro A.M., Ricordi C., Hering B.J., Auchincloss H., Lindblad R., Robertoson R.P., Secchi A., Brendel M.D., Berney T., Brennan D.C. International trial of the Edmonton protocol for islet transplantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;355:1318–1330. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinnen S.G., Hoekstra J.B., DeVries J.H. Insulin therapy for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:253–259. doi: 10.2337/dc09-S318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomei A.A., Manzoli V., Fraker C.A., Giraldo J., Velluto D., Najjar M., Pileggi A., Molano R.D., Ricordi C., Stabler C.L., Hubbell J.A. Device design and materials optimization of conformal coating for islets of Langerhans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2014;111:10514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402216111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torren C., Zaldumbide A., Duinkerken G., Schaaf S., Peakman M., Stangé G., Martinson L., Kroon E., Brandon E., Pipeleers D., Roep B. Immunogenicity of human embryonic stem cell-derived beta cells. Diabetologia. 2017;60:126–133. doi: 10.1007/s00125-016-4125-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vegas A.J., Veiseh O., Gürtler M., Millman J.R., Pagliuca F.W., Bader A.R., Doloff J.C., Li J., Chen M., Olejnik K. Long-term glycemic control using polymer-encapsulated human stem cell-derived beta cells in immune-competent mice. Nat. Med. 2016;22:306–311. doi: 10.1038/nm.4030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veiseh O., Doloff J.C., Ma M., Vegas A.J., Tam H.H., Bader A.R., Li J., Langan E., Wyckoff J., Loo W.S. Size- and shape-dependent foreign body immune response to materials implanted in rodents and non-human primates. Nat. Mater. 2015;14:643–651. doi: 10.1038/nmat4290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T., Okitsu T., Ozawa F., Nagata S., Matsunari H., Nagashima H., Nagaya M., Teramae H., Takeuchi S. Millimeter-thick xenoislet-laden fibers as retrievable grafts mitigate foreign body reactions for long-term glycemic control in mice. Biomaterials. 2020;225:120162. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.120162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver J.D., Headen D.M., Hunckler M.D., Coronel M.M., Stabler C.L., García A.J. Design of a vascularized synthetic poly(ethylene glycol) macroencapsulation device for islet transplantation. Biomaterials. 2018;172:54–65. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.04.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yabe S.G., Fukuda S., Nishida J., Takeda F., Nashiro K., Okochi H. Induction of functional islet-like cells from human iPS cells by suspension culture. Regenerative Ther. 2019;10:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.reth.2018.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Jiang S., Guan Y., Deng J., Lou S., Feng D., Kong D., Li C. Pancreatic islet surface engineering with a starPEG-chondroitin sulfate nanocoating. Biomater. Sci. 2019;7:2308. doi: 10.1039/c9bm00061e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.