Abstract

Purpose of Review

Kratom (mitragynine) is a commercially available herbal supplement that is gaining popularity in the United States. Kratom is associated with a variety of neurologic effects. This review will discuss kratom's association with seizure through 3 cases and highlight what neurologists should know about kratom's clinical effects and legal status.

Recent Findings

Kratom is currently commercially available, unscheduled by the US Drug Enforcement Administration, and a topic of regulatory debate in the United States. Large poison center reviews have suggested that kratom use is associated with seizure. There have been limited case studies to corroborate this finding. We present 3 cases in which seizures were associated with kratom use in patients treated for epilepsy.

Summary

Since 2008, kratom use is rising in prevalence in the United States aided by lack of regulation. Neurologists need to be aware of its association with seizure and other neurologic side effects.

Kratom is an herbal supplement derived from the Mitragyna speciosa tree, which is indigenous to Southeast Asia, Malaysia, and the Philippines. For centuries, kratom has been used recreationally throughout Southeast Asia to enhance productivity and mood. In the mid-twentieth century, it was also used to mitigate opioid withdrawal.1 It is primarily consumed as tea or by chewing whole leaves. In the United States, its primary use has been recreational for euphoric effects and for self-treating the symptoms of opioid withdrawal,2 as at high doses, kratom has opioid-like effects.3 Kratom is currently legal and available for retail purchase in the United States. The US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) has now listed kratom as a “drug of concern,” as it has been involved in over 150 overdose-related deaths as of 2017.3

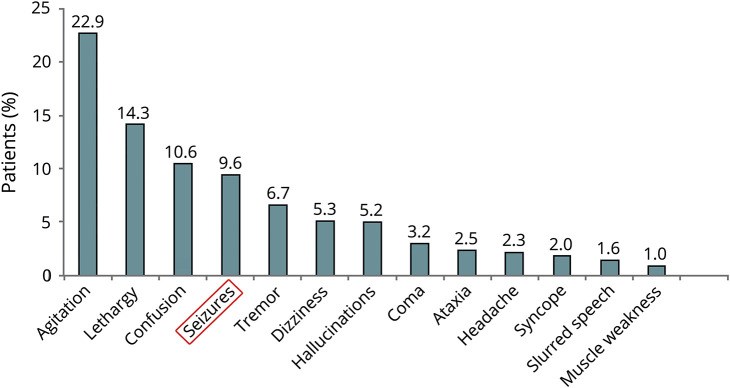

Kratom is of interest to the neurologist, given the variety of neurologic adverse effects. There have been reports of agitation, drowsiness, confusion, seizure, tremor, vertigo, hallucinations, coma, ataxia, headache, syncope, slurred speech, and muscle weakness following kratom use.4 There has even been a report of kratom use associated with spontaneous intracranial hemorrhage.5 However, seizures are common and have been reported after single-substance exposure with an incidence of 6.1%2 to 9.6%4 in the United States. In Thailand, seizures have been seen in as high as 17.5% of cases.6 As of 2019, there have been 4 case reports characterizing seizures following kratom use. Of these 4 cases, none had underlying epilepsy or a full neurologic workup. We hypothesize that kratom use is associated with seizure in patients with epilepsy. We present 3 cases of seizure in patients following kratom use, 2 with preexisting epilepsy and 1 with subsequently diagnosed epilepsy. We believe that US health care providers may not be aware of the neurologic effects of kratom. We will discuss the pharmacology of kratom, its clinical effects, and review the current understanding of the clinical relevance and regulation of kratom use in the United States.

Case Series

Patients were identified through outpatient clinical encounters for seizure follow-up during routine social history and substance abuse/herbal supplement questioning.

Patient 1

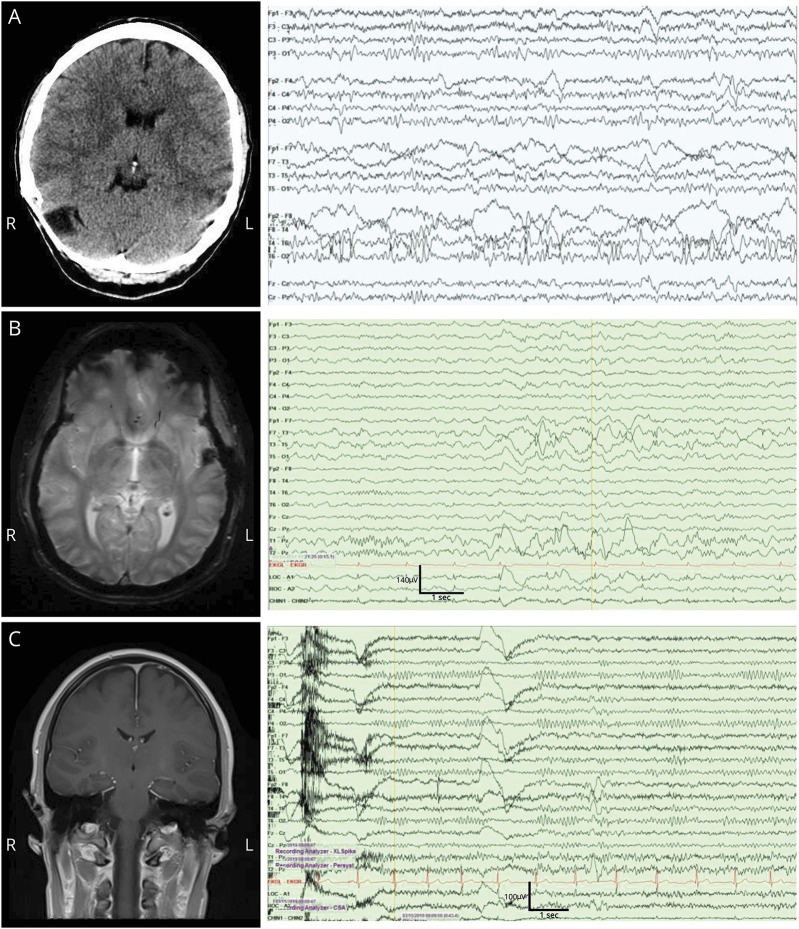

A 49-year-old woman with focal to bilateral tonic-clonic epilepsy status post meningioma resection (3 years prior) presented with frequent generalized tonic-clonic seizures. She had not had any seizures on her current regimen of eslicarbazepine and lacosamide. She began using kratom daily over the preceding month for anxiety and had 6 seizures in 1 month. She endorsed compliance with her antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) including lacosamide and eslicarbazepine (lacosamide level 2.3 μg/mL and Eslicarbazepine qualitatively positive on comprehensive drug screen). No additional provoking factors were identified, and a standard urine toxicology screen was negative. Her laboratory studies were unremarkable, noncontrast CT of the head was unchanged, and EEG was unchanged with an asymmetry of background EEG activity and sharply contoured temporal alpha activity (figure 1). She was discharged on her existing AED combination with instruction to cease kratom use. At follow-up 4 months later, she had ceased kratom use and reported no further generalized tonic-clonic seizures.

Figure 1. Neuroimaging and EEG.

(A) Patient 1: CT with postsurgical changes with stable EEG showing a breach rhythm with right temporal focal slowing and sharply contoured alpha activity. (B) Patient 2: stable cavernous hemangioma and stable EEG showing high-amplitude left temporal spike and slow-wave activity with left temporal breach artifact and focal slowing. (C) Patient 3: normal brain MRI and EEG with right temporal sharp waves predominant in sleep.

Patient 2

A 37-year-old man with focal to bilateral tonic-clonic epilepsy secondary to a left temporal cavernoma with resection in 2016 presented to epilepsy clinic following a generalized tonic-clonic seizure. For 2 years, he was maintained on levetiracetam 1000 mg BID. Treatment of his epilepsy had been complicated by opioid use disorder. He had used kratom intermittently as an attempt to wean off of opioids. He reported AED compliance. His urine toxicology screen was positive for tetrahydrocannabinol and benzodiazepines. He endorsed daily kratom ingestion before his increase in seizure frequency. His levetiracetam level was 20.7 μg/mL (therapeutic range 10.0–40.0 μg/mL), and other laboratory studies including standard toxicology screen were unremarkable. An EEG was performed, which was unchanged with high-amplitude left temporal spikes and slow-wave discharges (figure 1). Brain MRI showed an unchanged resection cavity. Cessation of kratom use was strongly recommended. On follow-up 1 year later, the patient did not report recurrent seizures but has had inpatient hospitalization for his substance use disorder.

Patient 3

A 24-year-old man presented to the neurology clinic after a first generalized tonic-clonic seizure. There were no seizure risk factors identified. He endorsed kratom ingestion including the day of the seizure. He reported using kratom for 1 month to cope with stress and anxiety; he had a previous history of prescription opioid abuse. Laboratory studies including standard urine toxicology screen were negative at that time. Brain MRI with and without contrast was unremarkable (figure 1). His first EEG showed right focal slowing without any epileptiform abnormality. He was advised to discontinue kratom, and no AED was initially prescribed. He had 2 more seizures over the next 4 months in the setting of kratom ingestion. He did not endorse seizure in the absence of kratom ingestion. He was advised to cease kratom use. On follow-up, a repeat EEG identified right temporal interictal epileptiform discharges in sleep (figure 1). He was subsequently treated with lamotrigine monotherapy, and kratom use was discontinued. On follow-up 1 year later, he reported no episodes of impaired awareness or seizures.

Discussion

We present 3 cases of seizures following the use of kratom in patients with diagnosed epilepsy; the third being treated for epilepsy subsequent to seizures associated with kratom use and an abnormal EEG. These cases support that kratom is associated with seizure and suggest that kratom is associated with breakthrough seizures in patients with known epilepsy.

Previous Case Literature

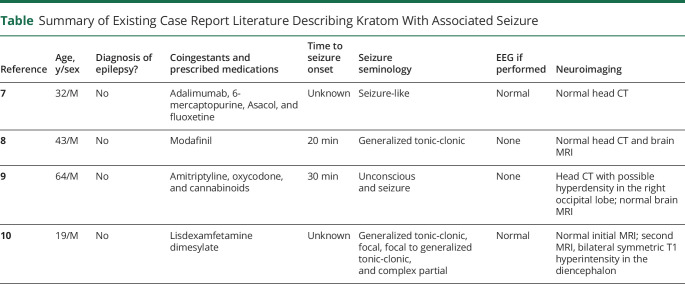

Existing case literature describing seizure from kratom use is sparse; we identified 4 reported cases that have been previously published.7–10 These are summarized in the table. Of these previous case reports, only 2 patients underwent EEG. Of the 4 patients described, they had varied presentations from single to multiple seizures, presence of coingestants, description of seizure semiology, and the availability of neuroimaging. These 4 cases of seizure were thought to be provoked by kratom use, and none of the patients were described as having underlying epilepsy. However as seen in the table, most previous cases had not reported a complete evaluation for epilepsy. This is in contrast to our case series where EEG and neuroimaging findings were supportive of an epilepsy diagnosis.

Table.

Summary of Existing Case Report Literature Describing Kratom With Associated Seizure

The strengths of this case series include the availability of a comprehensive evaluation, including follow-up clinical data for each patient. Previous case studies have not provided a full epilepsy evaluation, including neuroimaging to rule out any structural cause of seizure or EEG correlates. Limitations include that our cases can only suggest an association and should not be interpreted as causation. We cannot inform on any mechanistic reason for breakthrough seizure. It is our hope that our case series will serve to inspire further research. Most importantly, it is our goal to educate the practicing health care provider on kratom.

Kratom is not frequently discussed in the neurology literature and may not be well known to neurologists. Following is a review of the pharmacology, neurologic effects, clinical effects, epidemiology, and legal status that is pertinent to the practicing neurologist and epileptologist.

Pharmacology of Kratom

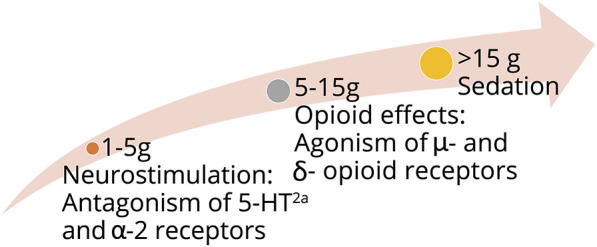

Kratom has an estimated 20 active compounds; however, mitragynine and 7-hydroxymitragynine (7-HMG) are thought to be the primary psychoactive ingredients.1,6,11,12 Mitragynine and 7-HMG are indole-containing alkaloids that make up around 60% and 2%, respectively, of the alkaloids in kratom. Mitragynine is thought to be 16 times more potent at antinociception than morphine, with 7-HMG being 4 times more potent than mitragynine.13 Depending on the dose, mitragynine and 7-HMG have pleotropic effects and target different receptors (figure 2). At low doses, around 1–5 g of raw leaves, mitragynine, and 7-HMG antagonize 5-HT2A and α-2 adrenergic receptors. This leads to neurostimulatory effects.12 At higher doses, from 5 to 15 g, mitragynine and 7-HMG are active at the μ- and δ-opioid receptors, leading to opioid-like effects such as euphoria and sedation. Mitragynine and 7-HMG are full agonists at opioid receptors with high affinity.14 Sedative effects, such as stupor and coma, are present at very high doses greater than 15 g and can mimic opioid overdose.11,14 However, in contrast to opioid overdose, animal studies have shown that very high doses (greater than 800 mg/kg) did not cause respiratory depression.15 This is not completely understood but may be due to the neurostimulatory effects when compared with other opioids13 or delta antagonism.16 Neurotropic effects begin within 5 to 10 minutes of exposure, with effects lasting 4 to 6 hours.17

Figure 2. Dose-Dependent Effects of Kratom and Receptor Targets.

Clinical Effects

Kratom interacts with many receptors and thus has a variety of clinical effects across multiple organ systems. Post et al.4 reviewed exposures to kratom reported to US Poison Control Centers from 2011 to 2017. There were 1,174 single-substance exposures characterized. The most common effects were stimulatory including agitation and tachycardia. Nausea and vomiting were also common, with 14.6% and 13.2% being affected, respectively. In 2019, Eggleston et al.2 analyzed cases from 2011 to 2018 and reported similar adverse effects, with 18.6% experiencing agitation and 16.9% with tachycardia. Effects of kratom were not limited to stimulatory effects, however. Adverse effects involved multiple organ systems, including hematologic (hyperbilirubinemia and elevated transaminases), gastrointestinal (abdominal pain and diarrhea), cardiovascular (chest pain, hypertension, and conduction disturbance), renal (acute kidney injury), and respiratory (dyspnea and respiratory depression).4 The clinical effects described above were derived from single-substance exposures2,4; however, given that kratom is currently unregulated by the Food and Drug Administration and marketed under a variety of names, there is a possibility of the presence of contaminants. For example, 1 particular brand of kratom in Sweden called Krypton was found to have metabolites of tramadol, O-desmethyltramadol.18 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also reported an outbreak of Salmonella that was attributed to kratom contamination.19

Kratom and the Nervous System

The neurologic effects of kratom are varied and illustrated in figure 3. Supplements leading to seizures are not a unique paradigm and must be taken into account when collecting the social history. Certain supplements such as St John's wort, garlic, grapefruit juice, folic acid, and echinacea interact with the cytochrome p450 system and may affect AED metabolism. Data suggest that more than 50% of patients with epilepsy use herbs and dietary supplements.20 Some supplements associated with seizures include black cohosh, barberry, ma huang, kava kava, yohimbe, and monkshood.10 Of note, mitragynine, the active ingredient in kratom, has a structural similarity to yohimbine, which is thought to cause seizure through impairment of gamma-aminobutyric acid.21 Animal studies on kratom have failed to show an etiology of seizure and demonstrated that at high concentrations, kratom decreases muscle twitch and causes muscle relaxation.22 Further research is needed to elucidate the mechanism of the association of kratom with seizure.

Figure 3. Percentage of Patients Reported to the National Poison Data System Experiencing Neurologic Side Effects After Kratom Use4.

Clinical Testing

Supplement use is common in patients with epilepsy, but because up to 29% of patients may not report such use to physicians,20 clinical testing is useful and important in certain settings. At the time of patient presentation in our cases, clinical testing for kratom was not readily available at our institution. There remains a need for more readily available screening. There is currently available confirmatory testing for kratom (mitragynine) now available through LabCorp with a turnaround time of 5–10 days.23 There are other methods of testing available, with liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry shown to be most accurate,22 but this may not be rapidly available in the clinical setting. Kratom testing has been used in the postmortem setting during autopsy as well.24

Epidemiology and Relationship with the Opioid Epidemic

The prevalence of kratom use has increased rapidly from 2011 to 2017, showing a 52-fold increase over the 7-year time frame. Sixty-five percent of cases reported from 2011 to 2017 actually occurred between 2016 and 2017.4 US Poison Centers are also receiving an increasing number of calls regarding kratom exposure.25 The rapid rise in popularity may be related to the opioid epidemic, as a 45% increase in synthetic opioid–related overdose deaths occurred between 2016 and 2017.26 Some sources state that over 1 million Americans are currently using kratom.27 Although some patients use kratom recreationally for euphoria, some patients use kratom as a treatment to mitigate opioid withdrawal.15 A case report by Boyer et al.8 describes a patient who successfully stopped using IV opioids through self-treatment with kratom. In a 2016 anonymous survey of 10,000 kratom users, 85% of responders reported decreased pain, 83% increased energy, and 80% less depressive symptoms.28 Yet, the safety of kratom as a treatment for opioid use disorder and chronic pain has not been thoroughly studied. Therefore, it is not currently recommended by the FDA for use.29

Legal Status

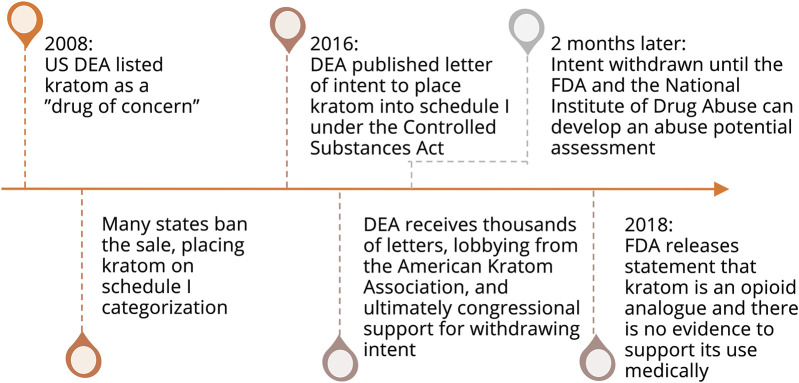

Kratom is currently legal and available in the United States despite its associated morbidity and mortality. From 2016 to 2017, 152 patients with death attributed to unintentional overdose tested positive for kratom on postmortem analysis, and of these, 91 deaths were attributed to kratom itself.3,24 Given limitations of clinical testing and the frequency of multidrug ingestion, it is difficult to attribute deaths specifically to kratom. However, in Colorado, 4 deaths were attributed to kratom only.30 In 2008, the DEA listed kratom among its “Drugs of Concern.” As a result, many states have placed kratom in Schedule I categorization with the DEA planning on categorizing kratom as Schedule I under the Controlled Substances Act. This was met with opposition from the public with bipartisan congressional support. In addition, the American Kratom Association produced several successful legal-regulatory arguments. Less than 2 months after the DEA's planned action to schedule kratom, the bill was retracted to seek input from the FDA, The National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the general public to formulate a formal full abuse potential assessment.1 A timeline of pertinent events is summarized in figure 4. Thus, kratom currently remains widely available but is banned in a few states including Rhode Island, District of Columbia, Wisconsin, Alabama, Arkansas, Indiana, and Vermont.27,31 As of this writing, the Food and Drug Administration has recommended that kratom be categorized as an opioid and placed into a Schedule I category, but the DEA has not yet taken action.31

Figure 4. Timeline of Important Governmental Statements and Actions Regarding the Legal Status of Kratom.

This series reports a possible association of kratom with seizures in patients with epilepsy. Given kratom's ease of access and rapid rise in popularity in the United States, it is essential for general neurologists, epileptologists, and neurointensivists to be aware of the association of kratom with seizure and other neurologic effects. Neurologists should inquire about the use of kratom in patients presenting with new-onset seizure or breakthrough seizure in patients with epilepsy.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

→ Kratom (mitragynine) is an uncontrolled ingestible substance that is readily available in the United States, and its use is rapidly rising.

→ Along with systemic effects, neurologists must be aware of kratom's effects on the CNS, especially seizures

→ There are nonuniform regulations at the federal and state level, so neurologists should be aware of regulations in their specific region

→ Further research is necessary to explore the correlation and cause of kratom and seizures in light of pending regulatory decisions

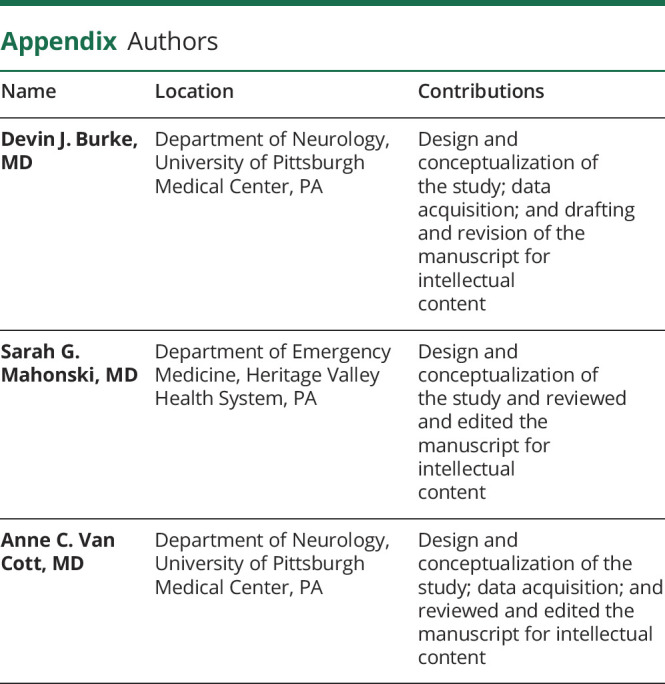

Appendix. Authors

Study Funding

No targeted funding reported.

Disclosure

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Full disclosure form information provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at Neurology.org/cp.

References

- 1.Henningfield JE, Fant RV, Wang DW. The abuse potential of kratom according the 8 factors of the controlled substances act: implications for regulation and research. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2018;235:573–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eggleston W, Stoppacher R, Suen K, Marraffa JM, Nelson LS. Kratom use and toxicities in the United States. Pharmacother J Hum Pharmacol Drug Ther 2019;39:775–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuehn B. Kratom-related deaths. JAMA 2019;321:1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Post S, Spiller HA, Chounthirath T, Smith GA. Kratom exposures reported to United States poison control centers: 2011–2017. Clin Toxicol 2019;57:847–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.NACCT Abstracts 2016. Clin Toxicol 2016;54:659–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trakulsrichai S, Tongpo A, Sriapha C, et al. Kratom abuse in Ramathibodi Poison Center, Thailand: a five-year experience. J Psychoactive Drugs 2013;45:404–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roche K, Kart K, Sangalli B, Lefberg J, Bayer M. Abstracts of the 2008 North American Congress of Clinical Toxicology Annual Meeting, September 11–16, 2008, Toronto, Canada. Clin Toxicol 2008;46:591–645. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyer EW, Babu KM, Adkins JE, McCurdy CR, Halpern JH. Self-treatment of opioid withdrawal using kratom (Mitragynia speciosa korth). Addiction 2008;103:1048–1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nelsen JL, Lapoint J, Hodgman MJ, Aldous KM. Seizure and coma following kratom (Mitragynina speciosa korth) exposure. J Med Toxicol 2010;6:424–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tatum WO, Hasan TF, Coonan EE, Smelick CP. Recurrent seizures from chronic kratom use, an atypical herbal opioid. Epilepsy Behav Case Rep 2018;10:18–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prozialeck WC, Jivan JK, Andurkar SV. Pharmacology of kratom: an emerging botanical agent with stimulant, analgesic and opioid-like effects. J Am Osteopath Assoc 2012;112:792–799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenbaum CD, Carreiro SP, Babu KM. Here today, gone tomorrow…and back again? A review of herbal marijuana alternatives (K2, spice), synthetic cathinones (bath salts), kratom, salvia divinorum, methoxetamine, and piperazines. J Med Toxicol 2012;8:15–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Michael White C. Pharmacologic and clinical assessment of kratom. Am J Heal Pharm 2018;75:261–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warner ML, Kaufman NC, Grundmann O. The pharmacology and toxicology of kratom: from traditional herb to drug of abuse. Int J Leg Med 2016;130:127–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ward J, Rosenbaum C, Hernon C, McCurdy CR, Boyer EW. Herbal medicines for the management of opioid addiction. CNS Drugs 2011;25:999–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Váradi A, Marrone GF, Palmer TC, et al. Mitragynine/corynantheidine pseudoindoxyls as opioid analgesics with mu agonism and delta antagonism, which do not recruit β-arrestin-2. J Med Chem 2016;59:8381–8397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carey JL, Babu KM. 82: Hallucinogens. In: Goldfrank's Toxicologic Emergencies. 10th ed. New York, NY: Appleton & Lange; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kronstrand R, Roman M, Thelander G, Eriksson A. Unintentional fatal intoxications with mitragynine and o-desmethyltramadol from the herbal blend krypton. J Anal Toxicol 2011;35:242–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.FDA Investigated Multistate Outbreak of Salmonella Infections Linked to Products Reported to Contain Kratom | FDA. Available at: fda.gov/food/outbreaks-foodborne-illness/fda-investigated-multistate-outbreak-salmonella-infections-linked-products-reported-contain-kratom#time. Accessed January 7, 2020.

- 20.Kaiboriboon K, Guevara M, Alldredge BK. Understanding herb and dietary supplement use in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsia 2009;50:1927–1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dunn RW, Corbett R. Yohimbine-induced seizures involve NMDA and GABAergic transmission. Neuropharmacology 1992;31:389–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fluyau D, Revadigar N. Biochemical benefits, diagnosis, and clinical risks evaluation of kratom. Front Psychiatry 2017;8:62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kratom (Mitragynine), Screen and Confirmation | LabCorp. Available at: labcorp.com/test-menu/38091/kratom-mitragynine-screen-and-confirmation-urine#. Accessed November 4, 2019.

- 24.Olsen EOM, O'Donnell J, Mattson CL, Schier JG, Wilson N. Notes from the field: unintentional drug overdose deaths with kratom fetected: 27 states, July 2016–December 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:326–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anwar M, Law R, Schier J. Notes from the field: kratom (Mitragyna speciosa) exposures reported to poison centers—United States, 2010–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:748–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, Wilson N, Baldwin G. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths—United States, 2013–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67():1419–1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prozialeck WC, Avery BA, Boyer EW, et al. Kratom policy: the challenge of balancing therapeutic potential with public safety. Int J Drug Policy 2019;70:70–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grundmann O. Patterns of Kratom use and health impact in the US—results from an online survey. Drug Alcohol Depend 2017;176:63–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.FDA issues warnings to companies selling illegal, unapproved kratom drug products marketed for opioid cessation, pain treatment and other medical uses | FDA. Available at: fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-issues-warnings-companies-selling-illegal-unapproved-kratom-drug-products-marketed-opioid. Accessed January 7, 2020.

- 30.Gershman K, Timm K, Frank M, et al. Deaths in Colorado attributed to kratom. N Engl J Med 2019;380:97–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Veltri C, Grundmann O. Current perspectives on the impact of Kratom use. Subst Abuse Rehabil 2019;10:23–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]