Abstract

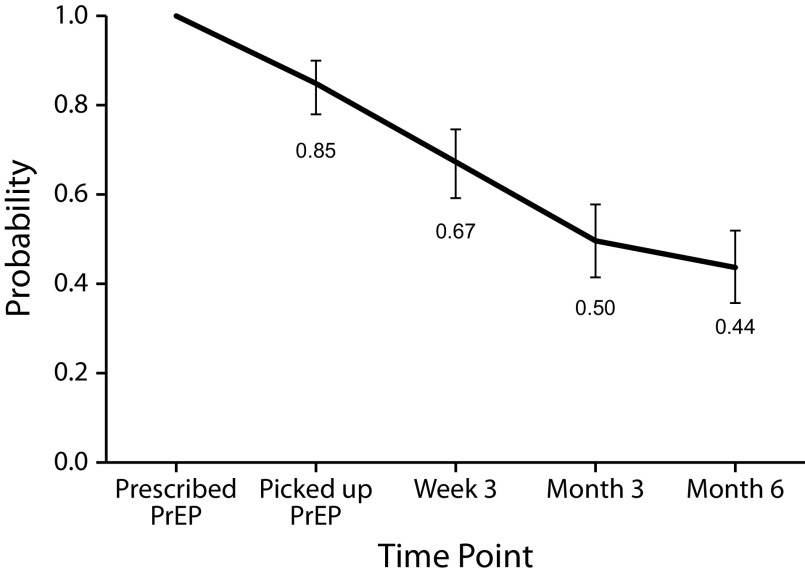

Despite high need, HIV preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) utilization among people who use drugs (PWUD) remains low. Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program implemented an innovative “low-threshold” PrEP Program for PWUD experiencing homelessness in Boston, Massachusetts. From October 1, 2018 to February 29, 2020, 239 clients were linked to PrEP services, and 152 were prescribed PrEP (mean = 8.9/month), over twice the number of PrEP prescriptions over the previous 12 months (n = 48; mean = 4/month). The cumulative probability of remaining on PrEP for 6 months was 44% (95% confidence interval = 36%, 52%).

Recent HIV outbreaks and clusters among people who use drugs (PWUD) and experience homelessness threaten to reverse previous success in lowering HIV incidence among PWUD in the United States. As such, there is an urgent need to expand access to HIV prevention options for PWUD experiencing homelessness. Antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is an efficacious and recommended daily HIV prevention medication; however, despite high levels of need, PrEP utilization in this socially marginalized population remains low.1 Among several important challenges to PrEP implementation for PWUD experiencing homelessness2 is the widespread belief among providers, likely grounded in overlapping stigmas, that PWUD are not good PrEP candidates.3 Moreover, PWUD have described multilevel perceived barriers to PrEP use—for example, competing health needs, provider stigma, and lost or stolen medications resulting from homelessness.2 However, studies indicate that PWUD can adhere to daily medications (e.g., for HIV and hepatitis C virus treatment) with appropriate supports and programming innovation.2,4

INTERVENTION

Prior to October 1, 2018, at Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program (BHCHP), PrEP care was provider initiated and required in-person clinic visits with multiple steps over multiple days to receive a prescription (e.g., labs drawn, results received, prescription provided) and follow-up monitoring with a provider. Additionally, systematic navigational and adherence supports were lacking.

In 2018, in response to increasing rates of HIV transmission locally,5,6 BHCHP implemented an innovative PrEP Program for PWUD experiencing homelessness. This PrEP Program utilizes a “low threshold” care model, which is characterized by highly accessible, harm reduction–oriented approaches (e.g., care is not contingent on abstinence from substance use). One key innovation involves intensive, flexible PrEP navigation services, which include the following: obtaining guideline-recommended intake and follow-up laboratory data through outreach-based phlebotomy; following up closely with clients through phone- and street-based outreach; accompanying clients to appointments; assisting with medication pickup and delivery; and making referrals to other services as needed or desired. Navigation intensity is tailored to clients’ needs but often involves weekly check-ins and lab follow-ups at four weeks and every three months thereafter. A panel of “PrEP champions” (i.e., clinicians) and a PrEP nurse provide brief in-person or phone visits to review clients’ assessments and prescribe same-day PrEP when appropriate. Clinician visits are scheduled every three months, but missed appointments do not necessitate medication discontinuation if appropriate lab follow-up can be performed. Additional innovations include safe same-day starts (prior to HIV status confirmation), short-interval prescriptions (seven to 14 days, to mitigate impact of lost or stolen medication and support adherence through more frequent contact), and on-site medication storage at BHCHP and affiliated venues.

For more details on the program, please contact the authors.

PLACE AND TIME

BHCHP is a federally qualified health center serving more than 10 000 individuals experiencing homelessness in Suffolk County, Massachusetts, an Ending the HIV Epidemic priority jurisdiction. BHCHP utilizes highly accessible, harm reduction–oriented approaches to care.

BHCHP’s PrEP Program was initiated inside the health center and in nonmedical settings (e.g., homeless shelters, syringe service programs, street venues) on October 1, 2018, and is ongoing; we present data through February 29, 2020.

PERSON

Candidates for BHCHP’s PrEP Program include individuals with sexual (e.g., transactional sex, condomless sex) or drug-using (e.g., syringe sharing) behaviors that increase HIV risk, who are referred by BHCHP HIV counselors, clinicians, or partner agencies. Client sociodemographics are described in Table 1.

TABLE 1—

Patient Characteristics: Boston Health Care for the Homeless Preexposure Prophylaxis Program, Boston, MA, October 2018–February 2020

| Mean ±SD or No. (%) | |

| Age, y | 38.5 ±9.3 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 138 (57.7) |

| Female | 77 (32.2) |

| Transgender female | 21 (8.8) |

| Nonbinary | 1 (0.4) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 139 (58.2) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 33 (13.8) |

| Hispanic/Latino/a | 51 (21.3) |

| Other/unknown | 16 (6.7) |

| Primary language | |

| English | 222 (92.8) |

| Spanish | 16 (6.8) |

| Vietnamese | 1 (0.4) |

| History of injection drug use | 169 (70.6) |

| Current primary care provider at BHCHP | 170 (71.1) |

Note. BHCHP = Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program. The sample size was n = 239.

PURPOSE

The overarching goal of BHCHP’s PrEP Program is to increase PrEP use among PWUD experiencing homelessness, eventually decreasing HIV incidence. We hope that this report can motivate and inform other programs regionally and nationally, especially where HIV clusters and outbreaks have emerged in this marginalized population.

IMPLEMENTATION

BHCHP provides PrEP navigation and low-threshold care by staff trained in engaging PWUD experiencing homelessness, and its PrEP Program was built on long-standing relationships with outreach staff based in shelters and harm-reduction interventions to facilitate building trust with clients.

EVALUATION

For this posthoc evaluation of BHCHP’s PrEP Program, we drew on pharmacy and electronic medical records to confirm PrEP medication pickup, and on program-specific tracking information from the first 17 months of the program’s implementation. From October 1, 2018 to February 29, 2020, BHCHP linked 239 PWUD experiencing homelessness to PrEP services (i.e., referred to PrEP navigator), of whom 152 (64%) were prescribed PrEP (mean = 8.9 prescriptions/month), more than 2 times the mean number of PrEP prescriptions in the year preceding implementation of this low-threshold program (n = 48; mean = 4.0/month).

Of those prescribed PrEP and who had reached each respective milestone, 85% (129/152) picked up their initial prescription, and 67% (96/144) picked up a refill at three weeks, 40% (42/105) at three months, and 25% (22/88) at six months. Using the Kaplan–Meier method, we estimated that the cumulative probability of obtaining PrEP prescriptions for six months was 44% (95% confidence interval = 36%, 52%; Figure 1).

FIGURE 1—

Cumulative Probability of Picking Up Preexposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Prescription and Remaining on PrEP (if Prescribed PrEP) Over 6 Months: Boston Health Care for the Homeless PrEP Program, Boston, MA, October 2018–February 2020

Note. Error bars = 95% confidence intervals. The sample size was n = 239.

Notably, we could not collect data on clients who may have received PrEP outside of BHCHP (though this is uncommon), did not collect adherence data, and were limited in the data available in the years leading up to this program because detailed tracking was initiated as part of the program.

ADVERSE EFFECTS

There were no episodes of HIV seroconversion with development of drug resistance or flares of chronic hepatitis B infections associated with the PrEP Program. Other potential social or emotional adverse events were not systematically collected.

SUSTAINABILITY

BHCHP implemented an innovative “low threshold” PrEP Program for PWUD experiencing homelessness. This program had rates of PrEP initiation (i.e., initial prescriptions picked up) and persistence (i.e., prescription refills over six months) comparable to those documented among other populations, including among men who have sex with men attending sexual health clinics, a group for which PrEP has been targeted for nearly a decade.7 Our findings suggest that BHCHP’s innovative strategies can successfully engage this population in PrEP care. Despite this success and the efforts of the PrEP navigators, rates of PrEP discontinuation remained high, a pattern that has been seen with other treatments (e.g., buprenorphine). We did not collect reasons for PrEP discontinuation from the PWUD sample; however, the PrEP navigators report that high levels of mobility and PrEP interruptions due to incarceration and drug treatment were common reasons for disengagement.

Because of its initial success, the BHCHP PrEP Program is ongoing. To mitigate current and future HIV outbreaks, these approaches should be considered in a range of service settings (e.g., syringe service programs, mental health treatment programs, shelters), and should be accompanied with other harm reduction–focused interventions such as low barrier access to medications for opioid use disorder, wound care, and viral hepatitis vaccination and treatment. Moreover, this program relied on a full-time PrEP navigator; as such, local, state, and federal public health departments must invest resources in such programs to ensure sustainability and advocate for making PrEP navigation a billable service.

PUBLIC HEALTH SIGNIFICANCE

This evaluation adds to the growing literature indicating that PWUD can successfully engage in PrEP care when it is provided in low barrier settings with appropriate supports. Clinical providers should not assume that PWUD experiencing homelessness are uninterested in or unable to use PrEP. Funding for PrEP navigation for vulnerable populations should be expanded in both clinical and nonclinical settings where PWUD seek care, and PWUD should be better represented in research on PrEP and other emerging biomedical HIV prevention technologies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH; grants K01DA043412, P30AI042853, and R01DA051849).

An earlier version of this analysis was presented as a poster (#LBPEE45) at the 23rd International AIDS Conference, July 6–10, 2020.

Note. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

This study was reviewed and determined to be exempt by the Boston University Institutional Review Board because data were obtained from secondary sources.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mistler CB, Copenhaver MM, Shrestha R. The pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) care cascade in people who inject drugs: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-02988-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biello K, Bazzi A, Mimiaga M et al. Perspectives on HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) utilization and related intervention needs among people who inject drugs. Harm Reduct J. 2018;15(1):55. doi: 10.1186/s12954-018-0263-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edelman EJ, Moore BA, Calabrese SK et al. Primary care physicians’ willingness to prescribe HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis for people who inject drugs. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(4):1025–1033. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1612-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bazzi AR, Drainoni M-L, Biancarelli DL et al. Systematic review of HIV treatment adherence research among people who inject drugs in the United States and Canada: evidence to inform pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) adherence interventions. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):31. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-6314-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alpren C, Dawson EL, John B et al. Opioid use fueling HIV transmission in an urban setting: an outbreak of HIV infection among people who inject drugs—Massachusetts, 2015–2018. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(1):37–44. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Massachusetts Dept of Public Health. Clinical advisory: statewide outbreak of HIV infection in persons who inject drugs. Massachusetts Executive Office of Health and Human Services. 2019. Available at: https://www.mass.gov/doc/statewide-clinical-advisory-hiv-transmission-through-injection-drug-use-in-massachusetts/download. Accessed May 11, 2020.

- 7.Hojilla JC, Vlahov D, Crouch P-C, Dawson-Rose C, Freeborn K, Carrico A. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) uptake and retention among men who have sex with men in a community-based sexual health clinic. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(4):1096–1099. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-2009-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]