Abstract

Despite growing evidence that COVID-19 is disproportionately affecting communities of color, state-reported racial/ethnic data are insufficient to measure the true impact.

We found that between April 12, 2020, and November 9, 2020, the number of US states reporting COVID-19 confirmed cases by race and ethnicity increased from 25 to 50 and 15 to 46, respectively. However, the percentage of confirmed cases reported with missing race remained high at both time points (29% on April 12; 23% on November 9). Our analysis demonstrates improvements in reporting race/ethnicity related to COVID-19 cases and deaths and highlights significant problems with the quality and contextualization of the data being reported.

We discuss challenges for improving race/ethnicity data collection and reporting, along with opportunities to advance health equity through more robust data collection and contextualization. To mitigate the impact of COVID-19 on racial/ethnic minorities, accurate and high-quality demographic data are needed and should be analyzed in the context of the social and political determinants of health.

COVID-19 has infected more than 114 million people worldwide, killing more than 2.5 million.1 Every US state has COVID-19 infections, with more than 28.6 million cases and more than 513 000 deaths in the United States.2 In early April 2020, data from several large US cities showed that COVID-19 was disproportionately affecting racial/ethnic minority populations.3–5 The magnitude of the reported disproportionate COVID-19 impact on communities of color was and continues to be staggering. Many studies have confirmed that Black, Hispanic, Native American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander Americans are more likely to contract, be hospitalized for, and die from COVID-19 than are White Americans.6–11 Several studies and reports have highlighted the large number of cases and deaths being reported with unknown race/ethnicity, suggesting that the observed disparities are larger than reported and demonstrating an urgent need to improve the completeness and consistency of COVID-19 race/ethnicity data.12

Our goal in this study was to describe the evolution, granularity, and quality of COVID-19 data reported by race/ethnicity at the state level. We analyzed changes in state reporting of COVID-19 data between April 12 and November 9, 2020, highlighting observed gaps in available data that preclude a true accounting of the COVID-19 impact on racial/ethnic minority communities. Based on these gaps, we discuss interventions to improve data quality, recognize challenges to improvement, and propose strategies to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 on racial/ethnic minorities.

RACE/ETHNICITY DATA

Problems related to the quality and availability of race/ethnicity data have been a pervasive problem in public health surveillance for decades.13 Public health surveillance assesses the effects of disease on populations and is instrumental in public health responses to disease outbreaks such as the COVID-19 pandemic.14 Surveillance data, including on race/ethnicity, are used in mathematical modeling to assess the trajectory of illness among populations and to inform subsequent distribution of resources to affected communities. The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) defines minimum standards for collecting and reporting race/ethnicity across federal agencies.15 The OMB standards provide a baseline of 5 race categories and 2 ethnicity categories, collected as 2 separate fields, which can be supplemented by more finely detailed categories and tailored for local relevance.

Despite its utility, surveillance data have challenges, including timeliness, comprehensiveness, ethical implications, and lack of consistency in reporting across jurisdictions. Traditional strategies for dealing with missing data in public health surveillance, such as excluding cases with incomplete data, are problematic for race/ethnicity data because these data are unlikely to be missing completely at random. Imputation methods have evolved to predict race/ethnicity using data from US Census and other administrative data sources.16 However, self-reported race/ethnicity provides the most accurate and comprehensive source for assessing racial/ethnic disparities.

REPORTING OUTCOMES BY RACE/ETHNICITY

Racial/ethnic disparities in COVID-19 outcomes are prominent and associated with historical inequities and systemic racism.17 Two key factors amplifying the impact of COVID-19 on communities of color are (1) disproportion of minorities serving in “essential,” high-exposure positions18,19; and (2) systemic inequities in access to wealth, quality health care, education, transportation, and healthy food (i.e., the social and political determinants of health),20 resulting in disproportionate prevalence of chronic illnesses and underlying conditions associated with increased COVID-19 susceptibility and worse disease outcomes.21,22 Both of these factors are compounded by residential segregation, lending bias, and current day redlining, policies that sustain health inequities in communities of color by targeting resources and investments elsewhere.23

Despite growing evidence that COVID-19 disproportionately affects communities of color, racial/ethnic data are incomplete and inconsistent and obscure the true magnitude of COVID-19 racial/ethnic disparities. High-quality individual-level data should include granular and consistent race/ethnicity categories, which are needed to understand the effect on populations historically vulnerable to disparities in health outcomes, and should be contextualized using neighborhood sociodemographic characteristics to identify emerging outbreaks, prioritize communities with the most need, and allocate resources. Data are also needed to hold policymakers and public health officials accountable for addressing the observed health inequities related to COVID-19. Without accurate data, policies and interventions to mitigate racial/ethnic disparities cannot be implemented and progress toward equity cannot be measured.

STANDARDIZING RACE/ETHNICITY COVID-19 DATA

Early in the pandemic, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released a COVID-19 case report form that collects key information on persons under investigation for COVID-19 infection.24 In theory, this form would standardize information collected using the OMB race/ethnicity categories. However, state and local authorities were not required to use this form, and, in turn, health care professionals and laboratories in many jurisdictions opted not to collect or report patient race/ethnicity with testing results. Without federally mandated standards providing uniformity of racial/ethnic data collection and reporting, states had broad discretion on what to report, when to report it, and even whether to report it at all. The resulting patchwork of available data undermines efforts to advance health equity in the wake of COVID-19. Recognizing the issue of incomplete and inconsistent data, the CDC issued additional guidance requiring all laboratories to collect and report patient race/ethnicity for all COVID-19 tests completed.25

STATE VARIATION IN DATA REPORTING

The COVID Tracking Project at the Atlantic reports COVID-19 case, death, hospitalization, and testing data for all 50 states, Washington, DC, and the US territories.26 These data are publicly available through a creative commons license (CC-BY-NC-4.0). The COVID-19 Racial Data Tracker gathers data from every state on the race/ethnicity data fields reported for COVID-19 cases and deaths.27 Data from the COVID-19 Racial Data Tracker shed light on the variation in state-level reporting of COVID-19 by race/ethnicity and trends in data reporting over time. We compared the number of states and Washington, DC, reporting COVID-19 confirmed cases and deaths by race/ethnicity on April 12 and November 9, 2020. We analyzed 2 indicators of the data quality: combined reporting of race/ethnicity and percentage of cases and deaths with unknown race/ethnicity.

Table 1 compares states reporting COVID-19 confirmed cases and deaths by race/ethnicity at the 2 time points. On April 12, 2020, 25 states reported confirmed cases by race and 15 reported confirmed cases by ethnicity. On November 9, 2020, 49 states and Washington, DC, reported confirmed cases by race and 46 reported confirmed cases by ethnicity. On April 12, 2020, 21 states reported COVID-related deaths by race and 11 reported deaths by ethnicity. On November 9, 2020, all 50 states and Washington, DC (100%) reported deaths by race and 47 (92%) reported deaths by ethnicity. By contrast with the OMB standard of separate race and ethnicity categories, 20 states (39%) combined reported race and ethnicity for confirmed cases into a single category and 19 (37%) combined reported race and ethnicity for deaths into a single category.

TABLE 1—

Comparing Reporting of Race/Ethnicity for COVID-19 Confirmed Cases and Deaths: United States, April 12, 2020, and November 9, 2020

| April 12, 2020 |

November 9, 2020 |

|||||||

| US State | Reporting Cases by Race | Reporting Cases by Ethnicity | Reporting Deaths by Race | Reporting Deaths by Ethnicity | Reporting Cases by Race | Reporting Cases by Ethnicity | Reporting Deaths by Race | Reporting Deaths by Ethnicity |

| AK | • | • | • | • | ||||

| AL | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||

| AR | • | • | • | • | • | |||

| AZ | • | • | •a | •a | •a | •a | ||

| CA | • | • | •a | •a | •a | •a | ||

| CO | •a | •a | •a | •a | ||||

| CT | • | • | • | •a | •a | •a | •a | |

| DC | • | • | • | • | • | •a | •a | |

| DE | • | •a | •a | •a | •a | |||

| FL | • | • | • | • | ||||

| GA | • | • | •a | •a | •a | •a | ||

| HI | • | • | ||||||

| IA | • | • | • | • | ||||

| ID | • | • | • | • | ||||

| IL | • | • | •a | •a | •a | •a | ||

| IN | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| KS | • | • | • | • | ||||

| KY | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||

| LA | • | • | • | |||||

| MA | • | • | • | • | •a | •a | •a | •a |

| MD | • | • | •a | •a | •a | •a | ||

| ME | • | • | • | • | ||||

| MI | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| MN | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| MO | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| MS | • | • | •a | •a | •a | •a | ||

| MT | • | • | • | • | ||||

| NC | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| ND | • | • | ||||||

| NE | • | • | • | • | ||||

| NH | •a | •a | •a | •a | ||||

| NJ | • | • | •a | •a | •a | •a | ||

| NM | •a | •a | •a | •a | ||||

| NV | •a | •a | •a | •a | ||||

| NY | • | • | •a | •a | ||||

| OH | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| OK | • | • | • | • | ||||

| OR | • | • | • | • | ||||

| PA | • | • | • | • | ||||

| RI | •a | •a | •a | •a | ||||

| SC | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | |

| SD | •a | •a | • | • | ||||

| TN | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||

| TX | • | •a | •a | •a | •a | |||

| UT | •a | •a | • | • | ||||

| VA | • | •a | •a | • | • | |||

| VT | • | • | • | • | ||||

| WA | • | • | • | • | •a | •a | •a | •a |

| WI | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| WV | • | • | ||||||

| WY | • | • | • | • | ||||

| Average | 25 | 15 | 21 | 11 | 50 | 46 | 51 | 47 |

Reports race/ethnicity as a single category.

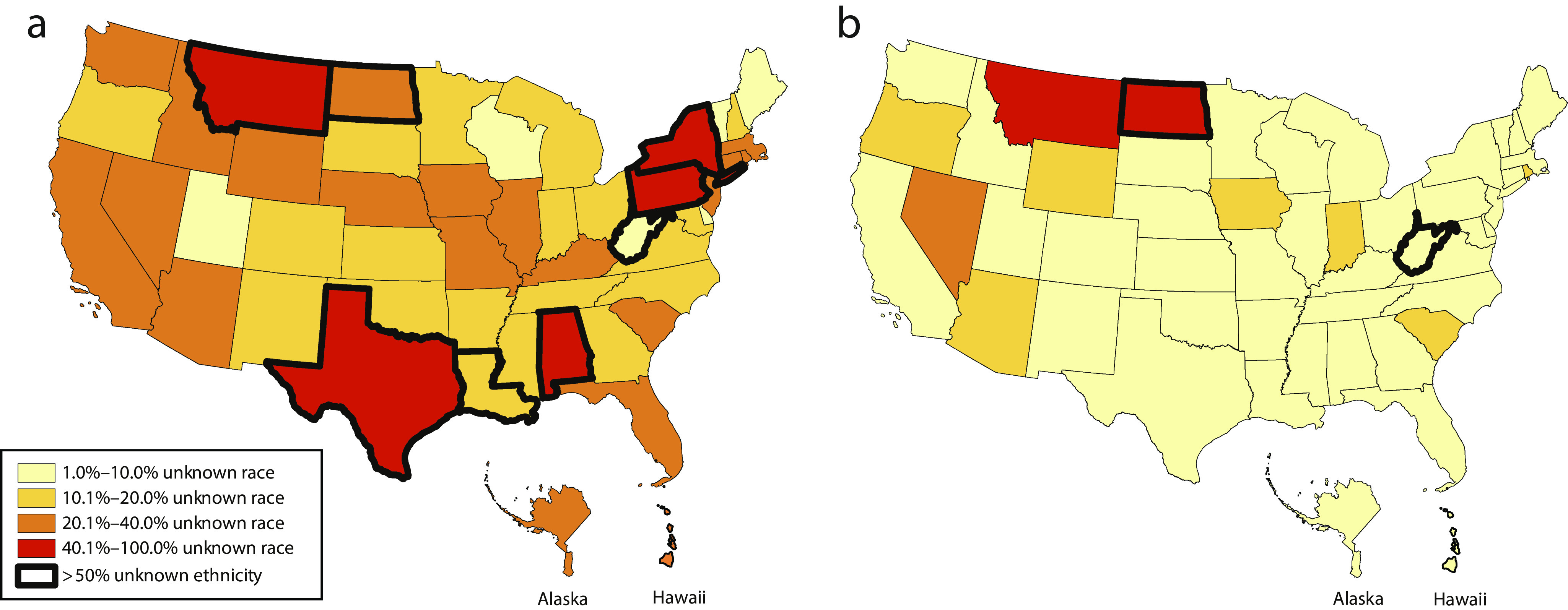

Whether states opt to report race/ethnicity cannot be conflated with the quality of the data. As we will describe in more detail, COVID-19 data quality problems are complex and pervasive. For this reason, we analyzed one of the more consistently reported data quality indicators: reported percentage of cases and deaths with unknown race/ethnicity. Figure 1 demonstrates the reported cases and deaths with unknown race/ethnicity on November 11, 2020. We display the percentage of cases reported with unknown race in 4 quartiles (0.0%–10.0%, 10.1%–20.0%, 20.1%–40.0%, and 40.1%–100.0%) and indicate states with more than 50% of cases and deaths reported with unknown ethnicity.

FIGURE 1—

Percentage of COVID-19 Confirmed (a) Cases and (b) Deaths With Unknown Race/Ethnicity: United States, November 9, 2020

Appendix A (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) compares the percentage of cases and deaths reported with unknown race/ethnicity on April 12 to that reported on November 9, 2020. Across all states, the average of the percentage of reported cases with unknown race or ethnicity was 29% and 39%, respectively, on April 12 and decreased to 23% and 29%, respectively, on November 9, 2020. The average of the percentage of reported deaths with unknown race/ethnicity was 15% and 29%, respectively, on April 12 and decreased to 7% and 9%, respectively, on November 9, 2020. Over this time, the percentage of cases reported with unknown race decreased in 18 states, increased in 6, and remained the same in 1. The percentage of cases reported with unknown ethnicity decreased in 11 states and increased in 3. The percentage of deaths reported with unknown race decreased in 12 states, increased in 8, and remained the same in 1. The percentage of deaths reported with unknown ethnicity decreased in 7 states and increased in 3.

REMAINING GAPS AND INCONSISTENCIES

Our team has been actively monitoring changes to individual states’ COVID-19 tracking and reporting Web sites. In addition to the percentage of cases and deaths reported with missing race/ethnicity, several other factors affect the quality of the data, including the methods of collection and reporting. We observed several other persistent inadequacies in data uniformity and quality not captured by this analysis.

The methods used to collect racial/ethnic data are unclear. Race/ethnicity data should be self-reported, allowing individuals to self-identify.28 Misclassification of race/ethnicity occurs when individuals are precluded from self-identification.29 It is unknown whether and to what extent clinics, hospitals, and laboratories are reporting self-reported race/ethnicity data. When race/ethnicity is missing, we do not know whether the individual declined to answer or the data are missing for some other reason.

The fields and definitions used to report racial/ethnic data are inconsistent and often do not align with accepted public health standards. As noted, many states combine reporting of race and ethnicity into a single category. Aggregating race and ethnicity data in this way obscures important distinctions between and among groups. Hispanic Black people and non-Hispanic Black people are not a monolithic group; they often have distinct cultural and historical backgrounds. Additionally, states selectively report on proportionally smaller minority groups, such as American Indian/Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander. Because of their smaller proportion of the population, some states elect to combine these distinct groups into 1 category—“other”—which diminishes our ability to evaluate the impact of COVID-19 and other extant risk factors on their communities. States such as California, Washington, and Colorado, which have larger populations of these minority groups, have recognized that these groups experience COVID-19 at disproportionate rates.30 However, data for these groups are systematically missing or inaccurate in many places, despite the known elevated risk of contracting COVID-19 owing to higher rates of preexisting and comorbid conditions.31

We also note that few states report the presence of comorbid conditions or socioeconomic factors. Nor do they provide county- or zip code–level COVID-19 data by race/ethnicity. Data related to housing, workplace exposure, insurance status, and access to health care are nearly universally absent from state reporting. Even fewer states report race/ethnicity associated with testing rates, hospitalizations, ventilator use, and other metrics needed to assess the severity of illness and COVID-19 complications among minority patients. Other important categories of individual-level data are also missing completely from state reporting. People with disabilities; people who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer; and people with behavioral health conditions have historically had significant health disparities and are also being disproportionately affected by COVID-19.32,33 As states continue to fight surging infection numbers of new cases and attempt to implement vaccination distribution programs, the need for culturally and linguistically appropriate mitigation strategies that are informed by communities is even more critical.34 Comprehensive and consistent fields of demographic data are needed to contextualize COVID-19 burden on minority, rural, and other vulnerable communities.

CHALLENGES FOR IMPROVING DATA REPORTING

The reasons for these problems are multifactorial, ranging from technical to ethical, which also makes them difficult to solve. For example, race/ethnicity fields may not be consistently recorded across states, may be self-reported or ascribed, and may be reported as missing when an individual reports “do not wish to answer.” Complicating the ability to report uniform and complete race/ethnicity data is the fact that state and local public health authorities receive COVID-19 testing data from several sources, including health care professionals, hospitals, and public and commercial laboratories. Many states use an electronic lab reporting system to collect COVID-19 case data, which introduces problems with data standardization and access to needed technology, especially in rural and other underserved settings.35 To overcome challenges with missing race/ethnicity data, several strategies are being employed, including imputation methods such as the Bayesian improved surname geocoding methodology.36 However, the extent to which these practices are used and their effectiveness are unknown.

Historical misuse of race/ethnicity data poses another challenge to gathering data needed to fully understand COVID-19 racial/ethnic disparities. Redlining intentionally weaponized racial/ethnic data collected in financial lending applications to prevent people of color from owning homes and building generational wealth, with long-term effects on health.37 Racially biased algorithms are a current example of data misuse, resulting in less access to health care resources among racial/ethnic minorities.38 Many studies have reinforced the problematic narrative that race and ethnicity are risk factors for disease, despite being social, not biological constructs.39 It is imperative that racism, not race, be recognized as the root cause of historical and COVID-19 health inequities. Mistrust in health care and governmental systems discourages individuals from disclosing their race/ethnicity. Transparency and accountability for how data are used to allocate resources and reduce the existing racial/ethnic disparities are necessary for improving both trust and disclosure. Furthermore, actively engaging communities in efforts to tailor data collection and to mitigate the impact of COVID-19, including recruitment of community health workers, may improve trust and, in turn, the data being reported.

Finally, public health and health system capacity constrain the ability of individual states to implement robust, evidence-based public health interventions to mitigate the effects of COVID-19 on racial/ethnic minority and other vulnerable populations. Disinvestment and budget constraints for state and local health departments are often the most severe in places with high concentrations of racial/ethnic minority populations.40 Thus, the very places with the most need for high-quality race/ethnicity data also have the most limited resources to implement these practices. This disinvestment by policymakers compounds the barriers to uncovering the full impacts of COVID-19 on communities of color.

OPPORTUNITIES TO ADVANCE HEALTH EQUITY

To improve the uniformity of racial/ethnic COVID-19 data, all states should require the reporting of racial/ethnic data using the OMB Race and Ethnic Standards for Federal Statistics.28 Robust reporting across population health measures, including positive cases, hospitalizations, deaths, underlying conditions, and testing rates, is optimal. It will also be important to monitor and publicly report vaccinations by race/ethnicity. States and local public health authorities should analyze demographic data in the context of social determinants of health, including housing, employment status and setting, health insurance status, and access to health care. They should also conduct ecologic analyses to identify the social, geographic, cultural, ecologic, and policy factors associated with COVID-19 burden and spread.

State and local authorities should apply a health equity lens when making COVID-19 decisions, such as when and where to reopen, how to define the “essential workforce,” and how to designate publicly available testing and vaccination sites. This entails inclusion and engagement of communities, who should be leading and actively informing these efforts. With limited federal intervention, local governments and public health departments will need the authority to make decisions based on the best public health data, which includes comprehensive, finely detailed, and high-quality racial/ethnic data. State governors should provide this authority and support local officials and community leaders in interventions that seek to mitigate COVID-19 disparities. State and local health officials should increase efforts to overcome deep mistrust by investing in culturally tailored information and training and linguistically appropriate interventions and by building a representative public health workforce, including community health workers, that includes members of disproportionately affected communities.

CONCLUSIONS

This study highlights significant improvements and deficiencies in reporting race/ethnicity data related to COVID-19. Although trends in race/ethnicity data reporting for COVID-19 have improved over time, we noted variation across all measures of race/ethnicity data reporting, including the measures being reported (testing, cases, and deaths), categories of race/ethnicity reported, and geographic granularity of data. In this analysis, we identified persistent data quality issues that are amenable to data standardization and process improvements. The nonuniformity of race/ethnicity COVID-19 data, and other notifiable disease data, continues to impede public health and policy leaders’ ability to assess the national landscape of COVID-19 racial/ethnic health disparities, and thus impedes efforts to advance health equity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by a $40 million award from the US Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health’s National Infrastructure for Mitigating the Impact of COVID-19 Within Racial and Ethnic Minority Communities through a cooperative agreement to create the National COVID-19 Resiliency Network (award 1CPIMP201187-01-00). Support for the work was made possible through funding from Google.org Charitable Giving (grants TF2005-091260 and TF2010-094862).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

No protocol approval was necessary because no human participants were involved in this study.

Footnotes

See also Noppert and Zalla, p. 1004.

REFERENCES

- 1.Johns Hopkins University and Medicine. Coronavirus Resource Center. CDC COVID data tracker. November 30, 2020. Available at: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu. Accessed November 30, 2020.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID data tracker. August 6, 2020. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#cases. Accessed August 6, 2020.

- 3.Mauger C, MacDonald C. Michigan’s COVID-19 cases, deaths hit Blacks disproportionately. Detroit News. April 2, 2020. Available at: https://www.detroitnews.com/story/news/local/michigan/2020/04/02/michigans-covid-19-deaths-hit-417-cases-exceed-10-700/5113221002. Accessed August 6, 2020.

- 4.Spielman F. Lightfoot declares “public health red alarm” about racial disparity in COVID-19 deaths. Chicago Sun-Times. April 6, 2020. Available at: https://chicago.suntimes.com/coronavirus/2020/4/6/21209848/coronavirus-covid-19-deaths-racial-disparity-life-expectancy-arwady-lightfoot. Accessed August 6, 2020.

- 5.Samuels R. Covid-19 is ravaging Black communities. A Milwaukee neighborhood is figuring out how to fight back. Washington Post. April 6, 2020. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/covid-19-is-ravaging-black-communities-a-milwaukee-neighborhood-is-figuring-out-how-to-fight-back/2020/04/06/1ae56730-7714-11ea-ab25-4042e0259c6d_story.html. Accessed August 6, 2020.

- 6.Mahajan UV, Larkins-Pettigrew M. Racial demographics and COVID-19 confirmed cases and deaths: a correlational analysis of 2886 US counties. J Public Health (Oxf). 2020;42(3):445–447. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdaa070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hospitalization rates and characteristics of patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed coronavirus disease 2019—COVID-NET, 14 states, March 1–30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(15):458–464. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Characteristics and clinical outcomes of adult patients hospitalized with COVID-19—Georgia, March 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(18):545–550. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6918e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodriguez-Lonebear D, Barceló NE, Akee R, Carroll SR. American Indian reservations and COVID-19 correlates of early infection rates in the pandemic. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2020;26(4):371–377. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000001206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaholokula JK, Samoa RA, Miyamoto RES, Palafox N, Daniels SA. COVID-19 special column: COVID-19 hits Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander communities the hardest. Hawaii J Health Soc Welf. 2020;79(5):144–146. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shippee TP, Akosionu O, Ng W et al. COVID-19 pandemic: exacerbating racial/ethnic disparities in long-term services and supports. J Aging Soc Policy. 2020;32(4–5):323–333. doi: 10.1080/08959420.2020.1772004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gross CP, Essien UR, Pasha S, Gross JR, Wang SY, Nunez-Smith M. Racial and ethnic disparities in population-level Covid-19 mortality. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(10):3097–3099. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06081-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams DR. The monitoring of racial/ethnic status in the USA: data quality issues. Ethn Health. 1999;4(3):121–137. doi: 10.1080/13557859998092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Public health surveillance in the United States: evolution and challenges. MMWR Suppl. 2012;61(3):3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Office of Management and Budget. Directive no. 15. Race and ethnic standards for federal statistics and administrative reporting. Available at: https://transition.fcc.gov/Bureaus/OSEC/library/legislative_histories/1195.pdf. Accessed February 26, 2021.

- 16.Xue Y, Harel O, Aseltine RH., Jr Imputing race and ethnic information in administrative health data. Health Serv Res. 2019;54(4):957–963. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yancy CW. COVID-19 and African Americans. JAMA. 2020;323(19):1891–1892. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.US Department of Health and Human Services. Health Resources and Services Administration; National Center for Health Workforce Analysis. Sex, race, and ethnic diversity of US health occupations (2011–2015). August 2017. Available at: https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bureau-health-workforce/data-research/diversity-us-health-occupations.pdf. Accessed February 26, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Artiga S, Garfield R, Orgera K. Communities of color at higher risk for health and economic challenges due to COVID-19. April 7, 2020. Available at: https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/communities-of-color-at-higher-risk-for-health-and-economic-challenges-due-to-covid-19. Accessed July 22, 2020.

- 20.Signorello LB, Cohen SS, Williams DR, Munro HM, Hargreaves MK, Blot WJ. Socioeconomic status, race, and mortality: a prospective cohort study. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(12):e98–e107. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis J, Penha J, Mbowe O, Taira DA. Prevalence of single and multiple leading causes of death by race/ethnicity among people aged 60 to 70 years. Prev Chronic Dis. 2017;14:e101. doi: 10.5888/pcd14.160241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quiñones AR, Botoseneanu A, Markwardt S et al. Racial/ethnic differences in multimorbidity development and chronic disease accumulation for middle-aged adults. PLoS One. 2019;14(6):e0218462. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0218462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Millett GA, Honermann B, Jones A et al. White counties stand apart: the primacy of residential segregation in COVID-19 and HIV diagnoses. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2020;34(10):417–424. doi: 10.1089/apc.2020.0155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Information for health departments on reporting cases of COVID-19. February 3, 2021. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/php/reporting-pui.html. Accessed February 26, 2021.

- 25.Department of Health and Human Services. COVID-19 pandemic response, laboratory data reporting: CARES Act Section 18115. January 8, 2021. Available at: https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/covid-19-laboratory-data-reporting-guidance.pdf. Accessed July 22, 2020.

- 26.COVID Tracking Project . Currently hospitalized per 1 million people. February 25, 2021. Available at: https://covidtracking.com. Accessed February 26, 2021.

- 27.Madrigal A. Tracking race and ethnicity in the COVID-19 pandemic. Atlantic. April 15, 2020. Available at: https://covidtracking.com/blog/tracking-race-and-ethnicity. Accessed July 22, 2020.

- 28.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Race, ethnicity, and language data: standardization for health care quality improvement. September 2012. Available at: https://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/final-reports/iomracereport/index.html. Accessed December 5, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Jarrín OF, Nyandege AN, Grafova IB, Dong X, Lin H. Validity of race and ethnicity codes in Medicare administrative data compared with gold-standard self-reported race collected during routine home health care visits. Med Care. 2020;58(1):e1–e8. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kamb L. King County has big racial disparities in coronavirus cases and deaths, according to public-health data. Seattle Times. May 1, 2020. Available at: https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/health/king-county-has-big-racial-disparities-in-coronavirus-cases-and-deaths-according-to-public-health-data. Accessed July 22, 2020.

- 31.Anderson C, Clift T, Bizjak T. California releases data on race of 37 percent of coronavirus patients, working to get more. Sacramento Bee. April 8, 2020. Available at: https://www.sacbee.com/news/local/health-and-medicine/article241874076.html. Accessed July 22, 2020.

- 32.Clift AK, Coupland CAC, Keogh RH, Hemingway H, Hippisley-Cox J. COVID-19 mortality risk in Down syndrome: results from a cohort study of 8 million adults. Ann Intern Med . [Online ahead of print October 21, 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Chatterjee S, Biswas P, Guria RT. LGBTQ care at the time of COVID-19. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14(6):1757–1758. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manchanda R. Three workforce strategies to help COVID affected communities. May 9, 2020. Available at: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200507.525599/full. Accessed July 22, 2020.

- 35.Los Angeles County Department of Public Health. Chief Science Office. Report on LA County COVID-19 data disaggregated by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. April 28, 2020. Available at: http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/docs/RacialEthnicSocioeconomicDataCOVID19.pdf. Accessed December 5, 2020.

- 36.Anson-Dwamena R, Pattah P, Crow J. Imputing missing race and ethnicity data in COVID-19 cases. August 26, 2020. Available at: https://www.vdh.virginia.gov/content/uploads/sites/182/2020/08/Race-Ethnicity-Imputation-COVID-19.pdf. Accessed December 5, 2020.

- 37.Krieger N, Van Wye G, Huynh M et al. Structural racism, historical redlining, and risk of preterm birth in New York City, 2013–2017. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(7):1046–1053. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Obermeyer Z, Powers B, Vogeli C, Mullainathan S. Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science. 2019;366(6464):447–453. doi: 10.1126/science.aax2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boyd RW, Lindo EG, Weeks LD, McLemore MR. On racism: a new standard for publishing on racial health inequities. July 2, 2020. Available at: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200630.939347/full. Accessed December 5, 2020.

- 40.Trust for America’s Health. The impact of chronic underfunding of America’s public health system: trends, risks, and recommendations, 2019. April 2019. Available at: https://www.tfah.org/report-details/2019-funding-report. Accessed August 6, 2020.