Abstract

Introduction

The recovery of other pathogens in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection has been reported, either at the time of a SARS-CoV-2 infection diagnosis (co-infection) or subsequently (superinfection). However, data on the prevalence, microbiology, and outcomes of co-infection and superinfection are limited. The purpose of this study was to examine the occurrence of co-infections and superinfections and their outcomes among patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Patients and methods

We searched literature databases for studies published from October 1, 2019, through February 8, 2021. We included studies that reported clinical features and outcomes of co-infection or superinfection of SARS-CoV-2 and other pathogens in hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients. We followed PRISMA guidelines, and we registered the protocol with PROSPERO as: CRD42020189763.

Results

Of 6639 articles screened, 118 were included in the random effects meta-analysis. The pooled prevalence of co-infection was 19% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 14%-25%, I2 = 98%) and that of superinfection was 24% (95% CI: 19%-30%). Pooled prevalence of pathogen type stratified by co- or superinfection were: viral co-infections, 10% (95% CI: 6%-14%); viral superinfections, 4% (95% CI: 0%-10%); bacterial co-infections, 8% (95% CI: 5%-11%); bacterial superinfections, 20% (95% CI: 13%-28%); fungal co-infections, 4% (95% CI: 2%-7%); and fungal superinfections, 8% (95% CI: 4%-13%). Patients with a co-infection or superinfection had higher odds of dying than those who only had SARS-CoV-2 infection (odds ratio = 3.31, 95% CI: 1.82–5.99). Compared to those with co-infections, patients with superinfections had a higher prevalence of mechanical ventilation (45% [95% CI: 33%-58%] vs. 10% [95% CI: 5%-16%]), but patients with co-infections had a greater average length of hospital stay than those with superinfections (mean = 29.0 days, standard deviation [SD] = 6.7 vs. mean = 16 days, SD = 6.2, respectively).

Conclusions

Our study showed that as many as 19% of patients with COVID-19 have co-infections and 24% have superinfections. The presence of either co-infection or superinfection was associated with poor outcomes, including increased mortality. Our findings support the need for diagnostic testing to identify and treat co-occurring respiratory infections among patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is associated with high morbidity and mortality [1, 2]. Current evidence shows that severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the causative agent of COVID-19, is primarily transmitted through respiratory droplets [3, 4] from symptomatic, asymptomatic, or pre-symptomatic individuals [4, 5]. Similar to other respiratory pathogens, such as influenza, where approximately 25% of older patients get secondary bacterial infections [6, 7], both superinfections and co-infections with SARS-CoV-2 have been reported [8–10]. However, there is scarce data on the frequency of co-infection and superinfections by viral, bacterial, or fungal infections and associated clinical outcomes among patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 [8–10].

We define co-infection as the recovery of other respiratory pathogens in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection at the time of a SARS-CoV-2 infection diagnosis and superinfection as the subsequent recovery of other respiratory pathogens during care for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Two previous reviews have examined the prevalence of bacterial and fungal co-infection or superinfection in SARS-CoV-2 infected patients [11, 12]. In addition, prior work suggests outcome differences in patients with co-infections vs. superinfections. For example, Garcia-Vidal et al., showed that SARS-CoV-2 infected patients with superinfection s had a longer length of hospital stay (LOS) and higher mortality, while those with co-infections had a higher frequency of admission to the ICU [13].

Diagnostic testing and therapeutic decision-making may be affected by the presence of co-infection or superinfection with SARS-CoV-2 and other respiratory pathogens.

Therefore, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to examine the occurrence and outcomes (e.g., LOS) of respiratory co-infections and superinfections among patients infected with SARS-CoV-2.

Materials and methods

We conducted this systematic review in accordance with the Preferred Reporting in Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [14]. We registered this review with PROSPERO: CRD42020189763 [15]. The protocol is available as a S1 File.

Data sources and searches

With the help of a health sciences librarian (LC), we searched PubMed, Scopus, Wiley, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Web of Science Core Collection, and CINAHL Plus databases to identify English-language studies published from October 1, 2019, through February 8, 2021. We executed the search in PubMed and translated the keywords and controlled vocabulary for the other databases, and additional articles were added from reference lists of pertinent articles. The following keywords were used for the search: “coronavirus”,”coronavirus infections”, “HCoV”, “nCoV”, “Covid”, “SARS”, "COVID-19", “2019 nCoV”, “nCoV 19”, “SARS-CoV-2”, “SARS coronavirus2”, “2019 novel corona virus”, “Human”, “pneumonia”, “influenza”, “severe acute respiratory syndrome”, “co-infection”, “Superinfection”, “bacteria”, “fungus”, “concomitant”, “pneumovirinae”, “pneumovirus infections”, "respiratory syncytial viruses", “metapneumovirus”, “influenza”, “human”, “respiratory virus”, “bacterial Infections”, “viral infection”, “fungal infection”, “upper respiratory”, “oxygen inhalation therapy”, “intensive care units”, “nursing homes”, “subacute care”, “skilled nursing”, “intermediate care”, “patient discharge”, “mortality”, “morbidity” and English filter. A complete description of our search strategy is available as a S2 File.

Study selection

Citations were uploaded into Covidence®, an online systematic review software for the study selection process. Two authors (JSM and LW) independently screened titles and abstracts and read the full texts to assess if they met the inclusion criteria. The authors met and discussed any articles where there was conflict and decided to either include or exclude such articles. Inclusion criteria were randomized clinical trials (RCTs), quasi-experimental and observational human studies that reported clinical features and outcomes of co-infection or superinfection of SARS-CoV-2 (laboratory-confirmed) and other pathogens–fungal, bacterial, or other viruses–in hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients. We excluded studies that did not report co-infection or superinfection, editorials, reviews, qualitative studies, those published in a non-English language, articles where full texts were not available, and non-peer-reviewed preprints.

Data extraction

Three reviewers (JSM, LW, and VP) independently abstracted data from individual studies using a standardized template. We abstracted data on study design/methodology, location and setting (intensive care unit [ICU], inpatient non-ICU, or outpatient, where applicable), study population, use of antibiotics, proportion of patients with co-infections, implicated pathogens, method of detection of co-infections and superinfections (laboratory-verified or clinical features only), type of infection (bacterial, viral, or fungal), and outcomes of co-infected patients (death, mechanical ventilation, discharge disposition, length of hospital stay, or mild illness). Discrepancies were resolved by discussion between the three abstractors.

Risk of bias assessment

Risk of bias assessment was conducted by three authors (JSM, LW, and VP) independently. We used two study quality assessment tools, one specific to case series [16], and one for non-case series study designs [17].

The tool for case series examines four domains: selection, ascertainment, causality, and reporting [16]. The selection domain helps to assess whether participants included in a study are representative of the entire population from which they arise. Ascertainment assesses whether the exposure and outcome were adequately ascertained. Causality assesses the potential for alternative explanations and specifically for our study whether the follow-up was long enough for outcomes to occur. Reporting evaluates if a study described participants in sufficient detail to allow for replication of the findings. This tool consists of eight items, but only five were applicable to our study [16]. When an item was present in a study, a score of 1 was assigned and 0 if the item was missing. We added the scores (minimum of 0 and a maximum of 5) and assigned the risk of bias as follows: low risk (5), medium risk (3–4), high risk (0–2).

For non-case series studies, we used the Modified Downs and Black risk assessment scale to assess the quality of cohort studies and RCTs [17]. This scale consists of 27 items that assess study characteristics, such as internal validity (bias and confounding), statistical power, and external validity. We scored studies as low risk (score 20–27, medium risk (score 15–19), or high risk (score ≤14).

Data synthesis and analysis

The primary outcome was the prevalence of co-infections or superinfections by viral, bacterial, or fungal respiratory infections and SARS-CoV-2. We examined whether co-infection or superinfection was associated with an increased risk for the following patient outcomes: 1) mechanical ventilation, 2) admission to the ICU, 3) mortality and LOS.

We estimated the proportion of patients with co-infection or superinfection of viral, bacterial, and fungal respiratory infections and SARS-CoV-2. We anticipated a high level of heterogeneity given the novelty of COVID-19 and potential differences in testing and management of COVID-19 in the healthcare systems of the countries where the studies were conducted. We conducted all statistical analyses using Stata software, version 16.0 (Stata Corp. College Station, Texas). We used the “metan” and “metaprop” commands in Stata to estimate the pooled proportion of co-infection and superinfection and COVID-19 using a random effects model (DerSimonian Laird) [18, 19]. We stabilized the variance using the Freeman-Tukey arcsine transformation methodology in order to correctly estimate extreme proportions (i.e., those close to 0% or 100%) [18]. We assessed heterogeneity using the I2 statistic. Frequencies of outcome variables and study characteristics were estimated using descriptive statistics. For example, in studies where data on co-infecting or super-infecting pathogens were reported, we extracted and tallied the number of different pathogens reported. We calculated the proportion of pathogens using the number of pathogens as the numerator and the total number of pathogens of each type (bacteria, viruses, and fungi) from all the studies as the denominator.

We did not assess for publication bias because standard methods, such as funnel plots and associated tests, were developed for comparative studies and therefore do not produce reliable results for meta-analysis of proportions [20, 21].

Results

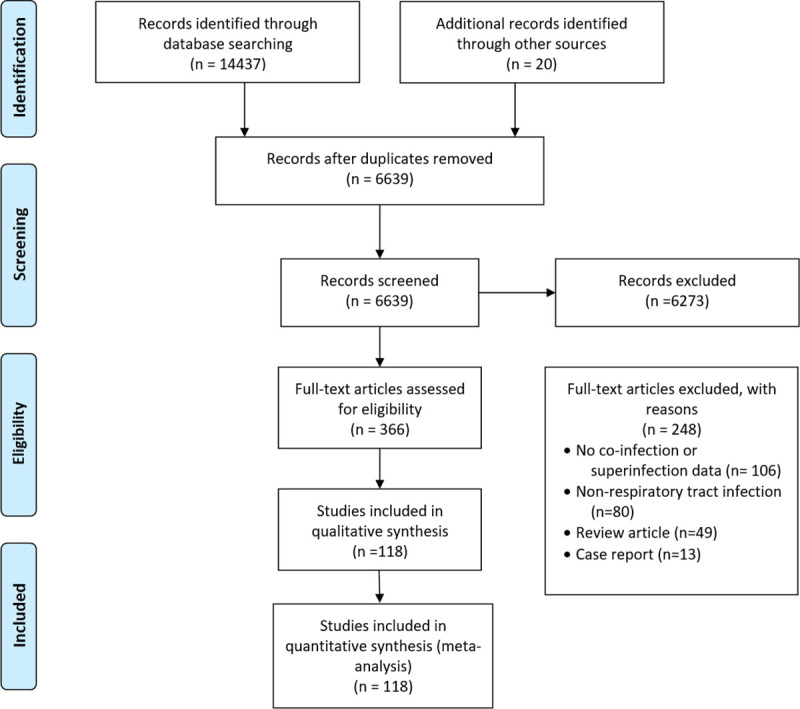

Our search yielded 14457 records; we excluded 7818 duplicates and screened 6639 articles. At the abstract and title review stage, we excluded 6273 articles, leaving 366 articles for full-text review. Of these, 118 articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in this meta-analysis. The most frequent reason for exclusion of studies at the full-text review stage was the absence of superinfection or co-infection data (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Study selection flow diagram: Adapted from the PRISMA guideline [11].

Approximately half of the studies (60/118) were retrospective cohort studies, 35% (42/118) were cases series, and 9% (11/118) were prospective cohort studies. There were two case-control studies, two cross-sectional studies, and one clinical trial. The majority of the studies were conducted in China (42% [49/118)]) and the US (15% [18/118]). Most of the studies were conducted in a mixed setting (i.e., ICU and non-ICU setting; 72% [85/118]) and 92% (108/118) were conducted exclusively in hospitalized patients. The majority of studies were conducted among adults (73% [86/118]). Sixty-seven (57%) of the included studies reported that patients included had co-infections, 37% (44/118) reported superinfections, and 6% (7/118) reported both co-infections and superinfections among patients. Viral co-infections in patients were reported in 67% (55/81) of the studies, bacterial infections in 74% (78/105), fungal in 48% (35/73) of studies. Not all of the 118 studies reported data on viral, bacterial or fungal infections (Table 1). Seventy percent (83/118) of the studies reported data on antibiotic use. Of these, antibiotics were administered in 98% (81/83) of the studies.

Table 1. Main characteristics of included studies.

| Study | Study design | Country | Setting | Number of patients | Age group of patients | Gender (% male) | ICU (%) | Patients who were ventilated n (%) | Patients who died n (%) | Viral co-infections n (%) | Bacterial co-infection n (%) | Fungal co-infections n (%) | Risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arentz, 2020 [22] | Case series | USA | ICUa | 21 | Adults | 52 | 100 | 15 (71) | 11 (52) | 3 (14) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | Medium |

| Barrasa, 2020 [23] | Case series | Spain | ICU | 48 | Adults | 56 | 100 | 45 (94) | 16 (33) | 0 (0) | 6 (13) | 0 (0) | Low |

| Campochiaro, 2020 [24] | Prospective cohort | Italy | ICU and non-ICU | 65 | Adults | 29 | 6 | 25 (38) | 16 (25) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | Low |

| Chen, 2020 [25] | Case series | China | ICU | 99 | Adults | 68 | 100 | 17 (17) | 11 (11) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 4 (4) | Medium |

| Cuadrado-Payán, 2020 [26] | Case series | Spain | ICU | 4 | Adults | 75 | 75 | 3 (75) | 0 (0) | 4 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | High |

| Ding, 2020 [27] | Case series | China | Non-ICU | 115 | Adults | NRb | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | Medium |

| Dong, 2020 [28] | Case series | China | Non-ICU | 11 | Adults/children | 54 | 0 | 1 (9) | 0 (0) | 1 (9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | Medium |

| Du, 2020 [29] | Case series | China | ICU | 109 | Adults | 67.9 | 48.6 | 33 (30) | 109 (100) | 0 (0) | NR | NR | Low |

| Fan, 2020 [30] | Retrospective cohort | China | ICU and non-ICU | 50 | Adults | 83 | 54 | 23 (46) | 12 (24) | 0 (0) | 5 (10) | 5 (10) | Low |

| Feng, 2020 [31] | Case series | China | ICU and non-ICU | 476 | Adults | 56.9 | 26 | 70 (15) | 38 (8) | 0 (0) | 35 (7) | 0 (0) | Medium |

| Garazzino, 2020 [32] | Retrospective cohort | Italy | ICU and non-ICU | 168 | Children | 55.9 | 1.1 | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 10 (6) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0) | Low |

| Gayam, 2020 [33] | Case series | USA | ICU and non-ICU | 350 | Adults | 33 | NR | NR | NR | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | Medium |

| Huang, 2020 [34] | Case series | China | ICU and non-ICU | 41 | Adults | 73 | 32 | 4 (10) | 6 (15) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | Medium |

| Kakuya, 2020 [35] | Case series | Japan | Non-ICU | 3 | Children | 100 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (33) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | Low |

| Khodamoradi, 2020 [36] | Case series | Iran | Non-ICU | 4 | Adults | 75 | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | Medium |

| Kim, 2020 [37] | Retrospective cohort | USA | Non-ICU | 115 | Adults/children | 45 | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 25 (22) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | Low |

| Koehler, 2020 [38] | Case series | Germany | ICU | 19 | Adults | NR | 100 | NR | 3 (16) | 2 (11) | 0 (0) | 5 (26) | Medium |

| Lian, 2020 [39] | Retrospective cohort | China | ICU and non-ICU | 788 | Children/Adults | 52 | 3 | 18 (2) | 0 (0) | NR | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | Low |

| Lin, 2020 [8] | Case series | China | ICU and non-ICU | 92 | Adults | NR | NR | NR | NR | 6 (7) | NR | NR | Medium |

| Liu, 2020 [40] | Retrospective cohort | China | ICU and non-ICU | 12 | Children/Adults | 66 | NR | 6 (50) | NR | 0 (0) | 2 (17) | 0 (0) | Low |

| Lv, 2020 [41] | Retrospective cohort | China | ICU and non-ICU | 354 | Adults | 49 | NR | NR | 11 (3) | 1 (0.3) | 32 (9) | 6 (2) | Low |

| Ma, 2020 [42] | Retrospective cohort | China | NR | 93 | Adults | 55 | NR | NR | 44 (47) | 46 (49) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | Low |

| Mannheim, 2020 [43] | Case series | USA | ICU and non-ICU | 64 | Children | 56 | 11 | NR | 0 (0) | 3 (5) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | Medium |

| Mo, 2020 [44] | Case series | China | ICU and non-ICU | 155 | Adults | 55 | NR | 36 (23) | 22 (14) | 13 (8) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | Medium |

| Nowak, 2020 [9] | Case series | USA | ICU and non-ICU | 1204 | Adults | 56 | NR | NR | NR | 36 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | Medium |

| Ozaras, 2020 [45] | Case series | Turkey | ICU and non-ICU | 1103 | Adults | 50 | NR | NR | NR | 6 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | Medium |

| Palmieri, 2020 [46] | Retrospective cohort | Italy | ICU and non-ICU | 3032 | Children/Adults | 67 | NR | NR | 3032 (100) | NR | NR | NR | Low |

| Peng, 2020 [47] | Retrospective cohort | China | ICU and non-ICU | 75 | Children | 58 | NR | NR | 0 (0) | 8 (11) | 31 (41) | 0 (0) | Low |

| Pongpirul, 2020 [48] | Case series | Thailand | ICU and non-ICU | 11 | Adults | 54 | NR | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (18) | 5 (45) | 0 (0) | Low |

| Richardson, 2020 [49] | Case series | USA | ICU and non-ICU | 5700 | Adults | 60 | 14.2 | 1151 (20) | 553 (10) | 39 (0.7) | 3 (0.1) | 0 (0) | Low |

| Sun, 2020 [50] | Retrospective cohort | China | ICU and non-ICU | 36 | Children | 61 | NR | NR | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | Medium |

| Tagarro, 2020 [51] | Retrospective cohort | Spain | ICU and non-ICU | 41 | Children | 44 | 9.7 | 4 (10) | 0 (0) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | Low |

| Wan, 2020 [52] | Case series | China | ICU and non-ICU | 135 | Adults | 53 | NR | 28 (21) | 1 (0.7) | NR | NR | NR | Medium |

| Wang Y, 2020 [53] | Case series | China | ICU and non-ICU | 55 | Adults | 40 | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | Low |

| Wang L, 2020 [54] | Case series | China | ICU and non-ICU | 339 | Adults | 49 | NR | NR | 65 (19) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | Low |

| Wang R, 2020 [55] | Case series | China | ICU and non-ICU | 125 | Adults | 56.8 | 15.2 | 4 | 0 (0) | 1 (0.8) | 9 (7) | 9 (7) | Medium |

| Wang Y, 2020 [56] | Clinical trial | China | ICU and non-ICU | 237 | Adults | 56 | NR | 21 (9) | 14 (6) | NR | NR | NR | Medium |

| Wee, 2020 [57] | Prospective cohort | Singapore | ICU and non-ICU | 3807 | Adults | NR | NR | NR | 1 (0.02) | 3 (0.08) | NR | NR | Medium |

| Wu C, 2020 [58] | Retrospective cohort | China | ICU and non-ICU | 201 | Adults | 63.7 | 26.4 | 67 (33) | 44 (22) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | Low |

| Xia, 2020 [59] | Case series | China | ICU and non-ICU | 20 | pediatric | 65 | NR | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (0.2) | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | Medium |

| Yang X, 2020 [60] | Case series | China | ICU | 710 | Adults | 67 | 100 | 37 (5) | 32 (4) | 0 (0) | 4 (0.6) | 4 (0.6) | Low |

| Yi, 2020 [61] | Case series | USA | ICU and non-ICU | 132 | Adult | 62 | 50 | 5 (4) | 1 (0.8) | NR | NR | NR | Medium |

| Zhang J, 2020 [62] | Case series | China | ICU and non-ICU | 140 | Adults | 50.7 | NR | NR | NR | 2 (1) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | Medium |

| Zhang G, 2020 [63] | Case series | China | ICU and non-ICU | 221 | Adults | 48.9 | 80 | 26 (12) | 5 (2) | 2 (0.9) | 6 (3) | 6 (3) | Medium |

| Zhao, 2020 [64] | Case series | China | ICU and non-ICU | 34 | Adults | 57.9 | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | Medium |

| Zheng, 2020 [65] | Case series | China | ICU and non-ICU | 1001 | Adult and pediatric | NR | NR | NR | NR | 2 (0.2) | NR | NR | Low |

| Zhou, 2020 [66] | Retrospective cohort | China | ICU and non-ICU | 191 | Adult | 62 | 26 | 32 (17) | 54 (28) | NR | NR | NR | Low |

| Zhu, 2020 [67] | Retrospective cohort | China | ICU and non-ICU | 257 | Adult and pediatric | 53.7 | 1.16 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 9 (3) | 11 (4) | 11 (4) | Low |

| Alvares P, 2020 [68] | Retrospective cohort | Brazil | ICU and non-ICU | 32 | Pediatric | 59.3 | 9.3 | 2 (6) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | NR | NR | Medium |

| Borman, 2020 [69] | Case series | UK | ICU | 719 | Adults | NR | 100.0 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 3NR | Low |

| Chauhdary W, 2020 [70] | Case series | Brunei Darussalam | ICU and non-ICU | 141 | Adults | NR | NR | NR | NR | 7 (5) | NR | Low | |

| Cheng L, 2020 [71] | Retrospective cohort | Hong Kong | ICU and non-ICU | 147 | Adults | 85.0 | 3.0 | NR | NR | NR | 4 (3) | NR | Low |

| Cheng Y, 2020 [72] | Retrospective cohort | China | ICU and non-ICU | 213 | Adults | 50.2 | 2 (1) | 8 (4) | 97 (46) | NR | NR | Low | |

| Cheng K, 2020 [73] | Retrospective cohort | China | NR | 212 | Adults/Children | 51.0 | 19 (9) | NR | NR | 13 (6) | NR | Low | |

| Contou D, 2020 [74] | Retrospective cohort | France | ICU | 92 | Adults | 79.0 | 100.0 | 83 (90) | 45 (49) | NR | 32 (35) | NR | Low |

| Dupont D, 2020 [75] | Case series | France | ICU | 19 | Adults | 78.0 | 100.0 | 18 (95) | NR | NR | NR | 19 (100) | Low |

| Elabbadi A, 2020 [76] | Case series | France | ICU | 101 | Adults | 78.2 | 100.0 | 83 (82) | 21 (21) | NR | 10 (10) | NR | Low |

| Falces-Romero, 2020 [77] | Retrospective cohort | Spain | ICU and non-ICU | 10 | Adults | 80.0 | 70.0 | 7 (70) | 7 (70) | NR | 0 | 10 (100) | Medium |

| Falcone M, 2020 [78] | Prospective cohort | Italy | ICU and non-ICU | 315 | Adults | 66.6 | 26.9 | 55 (17) | 70 (22) | NR | 11 (3) | 2 (1) | Medium |

| Fu Y, 2020 [79] | Case series | China | ICU and non-ICU | 5 | Adults | 80.0 | 100.0 | 5 (100) | NR | NR | 5 (100) | 2 (40) | Low |

| Garcia-Menino, 2021 [80] | Case series | Spain | ICU | 7 | Adults | 86.0 | 100.0 | NR | 1 (14) | NR | 7 (100) | NR | Low |

| Garcia-Vidal, 2021 [81] | Prospective cohort | Spain | ICU and non-ICU | 989 | Adults | 55.8 | 15.0 | NR | 103 (10) | 6 (1) | 47 (5) | 7 (1) | Low |

| Gouzien, 2020 [82] | Retrospective cohort | France | ICU | 53 | Adults | 67.9 | 100.0 | 53 (100) | 39 (74) | NR | NR | 1 (2) | Medium |

| Hashemi S, 2020 [83] | Case series | Iran | ICU and non-ICU | 105 | Adults/Children | NR | NR | 105 (100) | NR | NR | NR | Low | |

| Hazra A, 2020 [84] | Retrospective cohort | USA | ICU and non-ICU | 459 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 6 (1) | NR | NR | High | |

| He Bing, 2020 [85] | Retrospective cohort | China | NR | 21 | Adults/Children | NR | NR | 0 | NR | 2 (10) | 4 (19) | Medium | |

| Hirotsu Y, 2020 [86] | Prospective cohort | Japan | non-ICU | 191 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 32 (17) | NR | NR | Medium | |

| Hughes, 2020 [87] | Case series | UK | ICU | 836 | Adults | 62.0 | NR | 262 (31) | NR | 5 (1) | 27 (3) | Low | |

| Karaba, 2020 [88] | Retrospective cohort | USA | ICU and non-ICU | 1016 | Adults | 54.0 | 12.0 | NR | NR | 2 NR | 1NR | NR | Low |

| Kolenda, 2020 [89] | Prospective cohort | France | ICU | 99 | NR | NR | 100.0 | NR | NR | NR | 17 (17) | NR | Low |

| Kumar, 2021 [90] | Retrospective cohort | USA | ICU and non-ICU | 1573 | Adults | 57.9 | 31.0 | 247 (16) | 413 (26) | NR | 48 (3) | 9 (1) | Low |

| Lardaro T, 2020 [91] | Retrospective cohort | USA | ICU and non-ICU | 542 | Adults | 49.6 | 15.9 | 159 (29) | 78 (14) | NR | 8 (1) | NR | Medium |

| Lehmann C, 2020 [92] | Retrospective cohort | USA | ICU and non-ICU | 321 | Adults | 48.0 | 5.0 | NR | 22 (7) | 5 (2) | 7 (2) | NR | Medium |

| Lendorf, 2020 [93] | Retrospective cohort | Denmark | ICU and non-ICU | 115 | Adults/Children | 60.0 | 18.0 | 12 (10) | 16 (14) | NR | 9 (8) | 1 (1) | Medium |

| Li J, 2020 [94] | Retrospective cohort | China | ICU and non-ICU | 102 | Adults/Children | 66.7 | NR | 50 (49) | NR | 159 (156) | NR | Medium | |

| Li Z, 2020 [95] | Retrospective cohort | China | ICU and non-ICU | 32 | Adults | 62.5 | 40.0 | 6 (19) | NR | 6 (19) | 10 (31) | 2 (6) | High |

| Ma L, 2020 [96] | Retrospective cohort | China | ICU and non-ICU | 250 | Adults | 46.0 | 5 (2) | 4 (2) | 4 (2) | 2 (1) | NR | Low | |

| Mahmoudi H, 2020 [97] | Cross-sectional study | Iran | ICU and non-ICU | 342 | Adults | NR | NR | NR | NR | 6 (2) | NR | Medium | |

| Mendes N, 2020 [98] | Retrospective cohort | USA | ICU and non-ICU | 242 | Adults | 50.8 | 54 (22) | 52 (21) | NR | 6 (2) | NR | Low | |

| Mughal, 2020 [99] | Restrospective cohort | USA | ICU and non-ICU | 129 | Adults | 62.8 | 30.2 | 30 (23) | 20 (16) | NR | NR | NR | Low |

| Nasir N, 2020 [100] | Retrospective cohort | Pakistan | ICU and non-ICU | 30 | Adults | 83.0 | 33.0 | 24 (80) | 7 (23) | NR | 6 (20) | 7 (23) | Low |

| Nasir N, 2020 [101] | Retrospective cohort | Pakistan | ICU and non-ICU | 147 | Adults | 60.0 | NR | NR | 9 (6) | 1 (1) | Medium | ||

| Ng K F, 2020 [102] | Case series | China | ICU and non-ICU | 8 | Pediatric | 25.0 | 25.0 | NR | NR | 5 (63) | NR | NR | Low |

| Nori, 2021 [103] | Retrospective cohort | USA | ICU and non-ICU | 152 | Adults/Children | 59.0 | 55.9 | NR | 86 (57) | NR | 112 (74) | 3 (2) | Low |

| Obata, 2020 [104] | Retrospective cohort | USA | ICU and non-ICU | 226 | Adults | 55.1 | 24.8 | NR | 41 (18) | NR | 8 (4) | 8 (4) | Medium |

| Oliva, 2020 [105] | Case series | Italy | ICU and non-ICU | 7 | Adults | 57.0 | 14.3 | NR | NR | NR | 7 (100) | NR | Low |

| Papamanoli, 2020 [106] | Retrospective cohort | USA | ICU and non-ICU | 447 | Adults | 66.0 | 45.2 | 115 (26) | 102 (23) | NR | NR | NR | Low |

| Peci A, 2021 [107] | Case-control | Canada | ICU and non-ICU | 325 | Adults/Children | NR | NR | NR | 8 (2) | NR | NR | Low | |

| Pereira, 2021 [108] | Case-control | New York | ICU and non-ICU | 87 | Adults | 60.9 | 48.3 | NR | 32 (37) | 10 (11) | 6 (7) | 1 (1) | Medium |

| Pettit, 2020 [109] | Retrospective cohort | USA | ICU and non-ICU | 148 | Adults | 37.5 | 70.3 | 48 (32) | 46 (31) | 1 (1) | 14 (9) | 2 (1) | Low |

| Pickens, 2021 [110] | Retrospective cohort | Chicago | ICU | 179 | Adults | 61.5 | 100.0 | 179 (100) | 34 (19) | NR | 28 (16) | NR | Low |

| Ramadan H, 2021 [111] | Prospective cohort | Egypt | ICU and non-ICU | 260 | Adults | 55.4 | 8 (3) | 24 (9) | NR | 37 (14) | NR | Low | |

| Reig S, 2020 [112] | Retrospective cohort | Germany | ICU and non-ICU | 213 | Adults | 61.0 | 33.0 | 57 (27) | 51 (24) | NR | 26 (12) | 6 (3) | Low |

| Ripa M, 2020 [113] | Prospective cohort | Italy | ICU and non-ICU | 731 | Adults | 68.0 | 12.0 | NR | 194 (27) | NR | 24 (3) | 11 (2) | Low |

| Rothe K, 2020 [114] | Retrospective cohort | Germany | ICU and non-ICU | 140 | Adults | 64.0 | 15.0 | 41 (29) | NR | NR | NR | 9 (6) | Low |

| Segrelles-Calvo G, 2021 [115] | Case series | Spain | ICU and non-ICU | 7 | Adults | 71.0 | 86.0 | 7 (100) | 5 (71) | NR | NR | 7 (100) | Low |

| Sharifipour E, 2020 [116] | Prospective cohort | Iran | ICU | 19 | Adults | 58.0 | 100.0 | 19 (100) | 18 (95) | NR | 19 (100) | NR | Low |

| Sogaard, 2021 [117] | Retrospective cohort | Switzerland | ICU and non-ICU | 162 | Adults | 61.1 | 25.3 | NR | 17 (10) | 5 (3) | 19 (12) | 3 (2) | Low |

| Soriano, 2021 [118] | Retrospective cohort | Spain | ICU | 83 | Adults | 79.0 | 100.0 | 78 (94) | 20 (24) | NR | 7 (8) | NR | Low |

| Tang, 2021 [119] | Retrospective cohort | China | NR | 78 | Adults/Children | 53.0 | NR | NR | 4 (5) | 5 (6) | NR | Low | |

| Torrego, 2020 [120] | Retrospective cohort | Spain | ICU | 163 | NR | NR | 100.0 | 139 (85) | 23 (14) | NR | 18 (11) | NR | High |

| Townsend, 2020 [121] | Prospective cohort | Ireland | ICU and non-ICU | 117 | Adults | 63.0 | 29.1 | NR | 17 (15) | NR | 6 (5) | 1 (1) | Low |

| Verroken, 2020 [122] | Prospective cohort | Belgium | ICU | 32 | NR | NR | 100.0 | NR | NR | NR | 13 (41) | NR | Medium |

| Wang L, 2020 [123] | Retrospective cohort | UK | ICU and non-ICU | 1396 | Adults | 65.0 | 30.0 | NR | 420 (30) | NR | 11 (1) | NR | Low |

| Wei L, 2020 [124] | Retrospective cohort | China | non-ICU | 43 | Adults | 0.0 | 0.0 | NR | NR | 15 (35) | NR | NR | Low |

| White P, 2020 [125] | Retrospective cohort | UK | ICU and non-ICU | 135 | Adults | 69.0 | NR | 51 (38) | NR | NR | 36 (27) | Low | |

| Wu Q, 2020 [126] | Retrospective cohort | China | NR | 74 | Pediatric | 59.5 | 1 (1) | NR | 10 (14) | 16 (22) | NR | Low | |

| Xia P, 2020 [127] | Retrospective cohort | China | ICU | 81 | Adults | 66.7 | 100.0 | 66 (81) | 60 (74) | NR | 34 (42) | NR | Low |

| Xu J, 2020 [128] | Retrospective cohort | China | ICU | 239 | Adults | 59.8 | 100.0 | 165 (69) | 147 (62) | NR | 25 (10) | NR | Low |

| Xu S, 2020 [129] | Retrospective cohort | China | ICU and non-ICU | 64 | Adults | 0.0 | 1.6 | NR | NR | 9 (14) | 10 (16) | NR | Low |

| Xu W, 2021 [130] | Retrospective cohort | China | ICU and non-ICU | 659 | Adults/Children | 50.4 | 5.0 | NR | NR | NR | 48 (7) | NR | Low |

| Yao T, 2020 [131] | Retrospective cohort | China | NR | 83 | Adults | 63.9 | 71 (86) | 83 (100) | NR | 36 (43) | NR | Low | |

| Yu C, 2020 [132] | Retrospective cohort | China | NR | 128 | Adults | 43.0 | NR | 14 (11) | 64 (50) | 5 (4) | NR | Low | |

| Yue H, 2020 [133] | Retrospective cohort | China | NR | 307 | Adults | 47.3 | NR | NR | 176 (57) | NR | NR | Medium | |

| Yusuf E, 2021 [134] | Case-control | Netherlands | ICU | 92 | Adults | 76.1 | 100.0 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 10 (11) | High |

| Zhang C, 2020 [135] | Retrospective cohort | China | NR | 34 | Pediatric | 41.0 | NR | NR | 13 (38) | 9 (26) | NR | Low | |

| Zhang H, 2020 [136] | Retrospective cohort | China | NR | 38 | Adults | 84.2 | 23 (61) | 8 (21) | NR | 37 (97) | 3 (8) | Low |

aICU: intensive care unit.

bNR: Not reported.

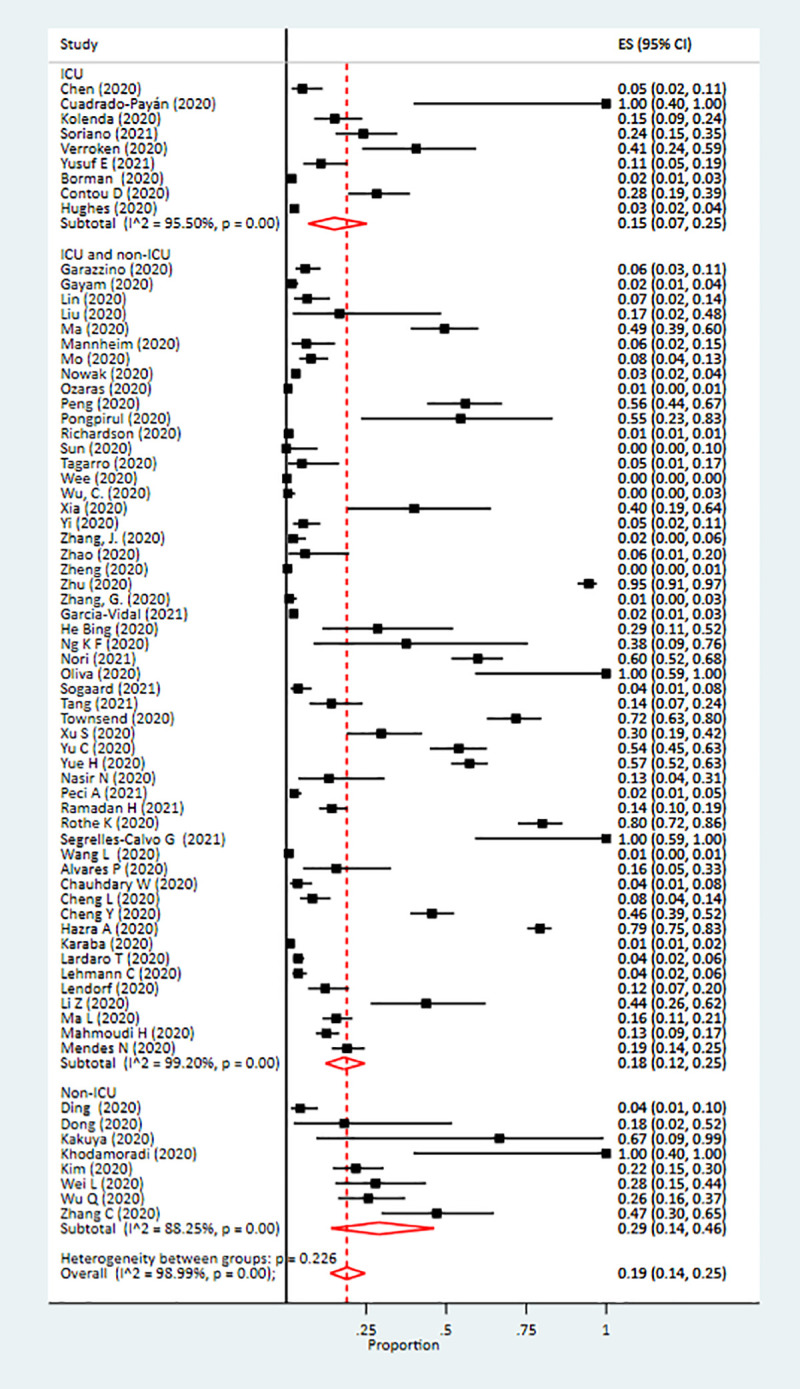

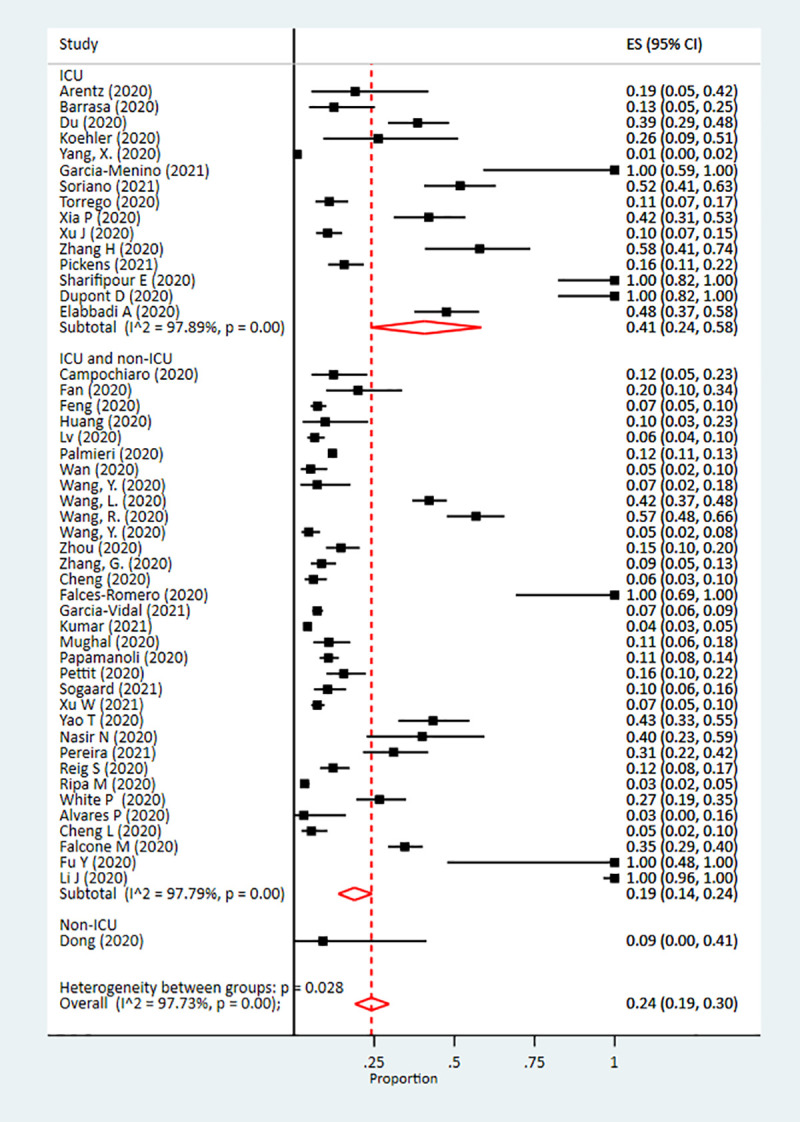

The pooled prevalence of co-infection was 19% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 14%-25%; I2 = 98%). The highest prevalence of co-infection was observed among non-ICU patients at 29% (95% CI: 14%-46%), while it was 18% (95% CI: 12%-25%) among combined ICU and non-ICU patients, and 16% (95% CI: 8%-25%) among only ICU co-infected patients (Fig 2). The pooled prevalence of superinfection was 24% (95% CI: 19%-30%), with the highest prevalence among ICU patients (41% [95% CI: 24%-58%]) (Fig 3).

Fig 2. Forest plot of pooled prevalence of co-infection in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2.

Fig 3. Forest plot of pooled prevalence of superinfection in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2.

Pooled prevalence of pathogen type stratified by co- or superinfection was: viral co-infections, 10% (95% CI: 6%-14%) and viral superinfections, 4% (95% CI: 0%-10%); bacterial co-infections, 8% (95% CI: 5%-11%) and bacterial superinfections, 20% (95% CI: 13%-28%); and fungal co-infections, 4% (95% CI: 2%-7%) and fungal superinfections, 8% (95% CI: 4%-13%) (S1–S3 Figs).

Seventy-eight studies reported data on specific organisms associated with co-infection or superinfection in COVID-19 patients (Table 2). Among patients with co-infections, the three most frequently identified bacteria were Klebsiella pneumoniae (9.9%), Streptococcus pneumoniae (8.2%), and Staphylococcus aureus (7.7%). The three most frequently identified viruses among co-infected patients were influenza type A (22.3%), influenza type B (3.8%), and respiratory syncytial virus (3.8%). For fungi, Aspergillus was the most frequently reported among those co-infected.

Table 2. All identified organisms as a proportion of total number of organisms per pathogen.

| Pathogen type | Co-infection (N = 1910) No. (%) | Superinfection (N = 480) No. (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | ||

| Staphylococcus aureus | 148 (7.7) | 13 (2.7) |

| Haemophilus influenza | 127 (6.6) | 6 (1.3) |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | 82 (4.3) | 6 (1.3) |

| Acinetobacter spps | 78 (4.1) | 107 (22.3) |

| Escherichia coli | 73 (3.8) | 33 (6.9) |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 10 (0.5) | 18 (3.8) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 189 (9.9) | 28 (5.8) |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 156 (8.2) | 4 (0.8) |

| Chlamydia pneumoniae | 29 (1.5) | 0 (0) |

| Bordetella | 3 (0.2) | 0 (0) |

| Moraxella catarrhalis | 32 (1.7) | 2 (0.4) |

| Pseudomonas | 67 (3.5) | 52 (10.8) |

| Enterococcus faecium | 14 (0.7) | 22 (4.6) |

| Viruses | ||

| Non-SARS-CoV-2a coronavirus strains | 38 (2.0) | 9 (1.9) |

| Human influenza A | 426 (22.3) | 0 (0) |

| Human influenza B | 73 (3.8) | 0 (0) |

| Respiratory syncytial virus | 72 (3.8) | 2 (0.4) |

| Parainfluenza | 17 (0.9) | 0 (0) |

| Human metapneumovirus | 20 (1.0) | 9 (1.9) |

| Rhinovirus | 68 (3.6) | 11 (2.3) |

| Adenovirus | 35 (1.8) | 2 (0.4) |

| Fungi | ||

| Mucor | 6 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) |

| Candida spp. | 19 (1.0) | 90 (18.8) |

| Aspergillus | 128 (6.7) | 65 (13.5) |

aSARS-CoV-2: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Among those with superinfections, the three most frequently identified bacteria were Acinetobacter spp. (22.0%), Pseudomonas (10.8%), and Escherichia coli (6.9%). For viruses, Rhinovirus was the most frequently identified among those with superinfections, and for fungi, Candida sp. was the most frequent (18.8%).

The overall prevalence of comorbidities was 42% (95% CI: 35%-49%). Among those with co-infections, the prevalence of comorbidities was 32% (95% CI: 24%-41%), while it was 54% (95% CI: 42%-65%) among those who were super-infected.

Patients with a co-infection or superinfection had a higher odds of dying than those who only had SARS-CoV-2 infection (odds ratio [OR] = 3.31, 95% CI: 1.82–5.99). Subgroup analysis of mortality showed similar results, where the odds of death was higher among patients who were co-infected (OR = 2.84; 95% CI: 1.42–5.66) and those who were super-infected (OR = 3.54; 95% CI: 1.46–8.58). There was a higher prevalence of mechanical ventilation among patients with superinfections (45% [95% CI: 33%-58%]) compared to those with co-infections (10% [95% CI: 5%-16%]). Fifty studies reported data on average LOS. The average LOS for co-infected patients was 29 days (standard deviation [SD] = 6.7), while the average LOS for super-infected patients was 16 days (SD = 6.2). None of the studies included in this meta-analysis reported data on discharge disposition and readmissions.

Risk of bias assessment

Sixty-two percent (73/118) of studies were rated as having low risk of bias, 34% (40/118) as having medium risk of bias, and 4% (5/118) as having a high risk of bias.

Discussion

We found that 19% of patients with SARS-CoV-2 were co-infected with other pathogens, and the prevalence of co-infection was higher among patients who were not in the ICU (29%). We also found a higher prevalence of superinfection compared to co-infection (24%), particularly among ICU patients (41%). Further, we found that super-infected patients had a higher prevalence of mechanical ventilation and comorbidities, and a higher risk of death.

Two previous reviews found a prevalence of bacterial co-infection of 7–8% and viral co-infection of 3% in SARS-CoV-2 infected patients, which are lower than our estimates [11, 12]. We extended this work by distinguishing between super- and co-infection because of the different implications of co-infections vs. superinfections. In particular, bacteria and other pathogens have been shown to complicate viral pneumonia and lead to poor outcomes [137]. In addition, our review spanned a longer period of time and included many newer studies, which may further account for differences in prevalence data.

The three most frequently identified bacteria among co-infected patients in our study were Klebsiella pneumonia, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Staphylococcus aureus. Streptococcus pneumoniae is a frequent cause of superinfection in other respiratory infections, such as influenza [138]. A study by Zhu et al. showed similar results [67], and a review by Lansbury et al. showed that Klebsiella pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenza were some of the most frequent bacterial co-infecting pathogens [11]. As expected, Staphylococcus aureus also was present in a sizeable number of cases. The most frequent bacteria identified in super-infected patients was Acinetobacter spp., which is a common infection, especially in ventilated patients [139].

In our study, the three most frequently identified viruses among co-infected patients were influenza type A, influenza type B, and respiratory syncytial virus. These findings are important particularly for influenza because testing constraints continue to exist, yet clinical presentation of influenza and SARS-CoV-2 is similar. There are major infection control and clinical implications of missing a SARS-CoV-2 or influenza diagnosis if co-infection is not considered and diagnostic testing for both pathogens is not undertaken.

Our findings have implications for infection preventionists, clinicians, and laboratory leaders. Respiratory virus diagnostic testing protocols should take into account that co-infection with SARS-CoV-2 is not infrequent, and therefore viral panel testing may be advisable in patients with compatible symptoms. Treatment protocols should also include assessment for co-infections, particularly influenza, so that appropriate treatment for both SARS-CoV-2 and influenza can be administered.

Another key finding from our study was that co-infection or superinfection was associated with an increased odds of death. This is consistent with other studies that have shown a positive association between co-infection or superinfection and increased risk of death among patients with the SARS-CoV-2 infection [140, 141].

Our study showed that antibiotics were administered in 98% of the 83 studies that reported this data. The type of antibiotics (i.e., broad or narrow spectrum) were not widely ascertainable, as these details were not provided in many studies. In the spirit of antibiotic stewardship, antibiotic use even in SARS-CoV-2 infected patients should be judicious and only in cases with an objective diagnosis of bacterial co-infection.

Our study has limitations. We were not able to assess important outcomes, such as discharge disposition and hospital readmissions, due to a lack of these data in the included studies. We were also not able to document time to superinfection, as the included studies did not report this information. Studies provided the number of patients with superinfections without stating the exact time when this determination was made after SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis. Most of the studies included in the meta-analysis were case series with their inherent limitations [142]. It is possible that some of the pathogens that were reported as superinfections or secondary infections were present but not tested for at admission and hence were co-infections. It was not possible to assess this from the studies. There was significant heterogeneity in the studies, as was anticipated given the variation in settings, patient populations, and diagnostic testing platforms across the studies.

Conclusions

Our study showed that as many as 19% of patients with COVID-19 have co-infections and 24% have superinfections. The presence of either co-infection or superinfection was associated with poor outcomes, such as increased risk of mortality. Our findings support the need for diagnostic testing to identify and treat co-occurring respiratory infections among patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Supporting information

(TIF)

(TIF)

(TIF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(XLSX)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

NS received research support for this work from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number DP2AI144244. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The funding agency did not play any role in the study’s design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): cases in US 2020 [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/cases-in-us.html.

- 2.The World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Pandemic 2020 [Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019.

- 3.The World Health Organization. Modes of transmission of virus causing COVID-19: implications for IPC precaution recommendations 2019 [Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/modes-of-transmission-of-virus-causing-covid-19-implications-for-ipc-precaution-recommendations.

- 4.Wang Y, Chen Y, Qin Q. Unique epidemiological and clinical features of the emerging 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) implicate special control measures. J Med Virol. 2020. 10.1002/jmv.25748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arons MM, Hatfield KM, Reddy SC, Kimball A, James A, Jacobs JR, et al. Presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infections and Transmission in a Skilled Nursing Facility. N Engl J Med. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chertow DS, Memoli MJ. Bacterial coinfection in influenza: a grand rounds review. JAMA. 2013;309(3):275–82. 10.1001/jama.2012.194139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morens DM, Taubenberger JK, Fauci AS. Predominant role of bacterial pneumonia as a cause of death in pandemic influenza: implications for pandemic influenza preparedness. J Infect Dis. 2008;198(7):962–70. 10.1086/591708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin D, Liu L, Zhang M, Hu Y, Yang Q, Guo J, et al. Co-infections of SARS-CoV-2 with multiple common respiratory pathogens in infected patients. Sci China Life Sci. 2020;63(4):606–9. 10.1007/s11427-020-1668-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nowak MD, Sordillo EM, Gitman MR, Paniz Mondolfi AE. Co-infection in SARS-CoV-2 infected Patients: Where Are Influenza Virus and Rhinovirus/Enterovirus? Journal of Medical Virology. 2020. 10.1002/jmv.25953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang M, Wu Q, Xu W, Qiao B, Wang J, Zheng H, et al. Clinical diagnosis of 8274 samples with 2019-novel coronavirus in Wuhan. medRxiv. 2020:2020.02.12.20022327. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lansbury L, Lim B, Baskaran V, Lim WS. Co-infections in people with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of infection. 2020. 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.05.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rawson TM, Moore LSP, Zhu N, Ranganathan N, Skolimowska K, Gilchrist M, et al. Bacterial and Fungal Coinfection in Individuals With Coronavirus: A Rapid Review To Support COVID-19 Antimicrobial Prescribing. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2020. 10.1093/cid/ciaa530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia-Vidal C, Sanjuan G, Moreno-García E, Puerta-Alcalde P, Garcia-Pouton N, Chumbita M, et al. Incidence of co-infections and superinfections in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.07.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic reviews. 2015;4:1. 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Musuuza J, Watson L, Parmasad V, Putman-Buehler N, Christensen L, Safdar N. The prevalence and outcomes of co-infection with COVID-19 and other pathogens: a rapid systematic review and meta-analysis. PROSPERO 2020. CRD42020189763 [Available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42020189763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murad MH, Sultan S, Haffar S, Bazerbachi F. Methodological quality and synthesis of case series and case reports. BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine. 2018;23(2):60. 10.1136/bmjebm-2017-110853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(6):377–84. 10.1136/jech.52.6.377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nyaga VN, Arbyn M, Aerts M. Metaprop: a Stata command to perform meta-analysis of binomial data. Arch Public Health. 2014;72(1):39. 10.1186/2049-3258-72-39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–88. 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hunter JP, Saratzis A, Sutton AJ, Boucher RH, Sayers RD, Bown MJ. In meta-analyses of proportion studies, funnel plots were found to be an inaccurate method of assessing publication bias. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(8):897–903. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin L. Graphical augmentations to sample-size-based funnel plot in meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods. 2019;10(3):376–88. 10.1002/jrsm.1340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arentz M, Yim E, Klaff L, Lokhandwala S, Riedo FX, Chong M, et al. Characteristics and Outcomes of 21 Critically Ill Patients With COVID-19 in Washington State. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1612–4. 10.1001/jama.2020.4326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barrasa H, Rello J, Tejada S, Martín A, Balziskueta G, Vinuesa C, et al. SARS-CoV-2 in Spanish Intensive Care Units: Early experience with 15-day survival in Vitoria. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2020. 10.1016/j.accpm.2020.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campochiaro C, Della-Torre E, Cavalli G, De Luca G, Ripa M, Boffini N, et al. Efficacy and safety of tocilizumab in severe COVID-19 patients: a single-centre retrospective cohort study. European Journal of Internal Medicine. 2020;76:43–9. 10.1016/j.ejim.2020.05.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507–13. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cuadrado-Payán E, Montagud-Marrahi E, Torres-Elorza M, Bodro M, Blasco M, Poch E, et al. SARS-CoV-2 and influenza virus co-infection. The Lancet. 2020;395(10236):e84. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31052-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ding Q, Lu P, Fan Y, Xia Y, Liu M. The clinical characteristics of pneumonia patients coinfected with 2019 novel coronavirus and influenza virus in Wuhan, China. J Med Virol. 2020. 10.1002/jmv.25781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dong X, Cao YY, Lu XX, Zhang JJ, Du H, Yan YQ, et al. Eleven faces of coronavirus disease 2019. Allergy. 2020. 10.1111/all.14289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Du RH, Liu LM, Yin W, Wang W, Guan LL, Yuan ML, et al. Hospitalization and Critical Care of 109 Decedents with COVID-19 Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202003-225OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fan W, Yumin Z, Zhongfang W, Min X, Zhe S, Zhiqiang T, et al. Clinical characteristics of COVID-19 infection in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a multicenter, retrospective, observational study. Journal of Thoracic Disease. 2020;12(5):1811–23. 10.21037/jtd-20-1914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feng Y, Ling Y, Bai T, Xie Y, Huang J, Li J, et al. COVID-19 with Different Severities: A Multicenter Study of Clinical Features. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2020;201(11):1380–8. 10.1164/rccm.202002-0445OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garazzino S, Montagnani C, Donà D, Meini A, Felici E, Vergine G, et al. Multicentre Italian study of SARS-CoV-2 infection in children and adolescents, preliminary data as at 10 April 2020. Euro surveillance: bulletin Europeen sur les maladies transmissibles = European communicable disease bulletin. 2020;25(18). 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.18.2000600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gayam V, Konala VM, Naramala S, Garlapati PR, Merghani MA, Regmi N, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes of patients coinfected with COVID-19 and Mycoplasma pneumoniae in the USA. Journal of Medical Virology. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kakuya F, Okubo H, Fujiyasu H, Wakabayashi I, Syouji M, Kinebuchi T. The first pediatric patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Japan; The risk of co-infection with other respiratory viruses. Japanese journal of infectious diseases. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khodamoradi Z, Moghadami M, Lotfi M. Co-infection of coronavirus disease 2019 and influenza a: A report from Iran. Archives of Iranian Medicine. 2020;23(4):239–43. 10.34172/aim.2020.04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim D, Quinn J, Pinsky B, Shah NH, Brown I. Rates of Co-infection Between SARS-CoV-2 and Other Respiratory Pathogens. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2085–6. 10.1001/jama.2020.6266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koehler P, Cornely OA, Böttiger BW, Dusse F, Eichenauer DA, Fuchs F, et al. COVID-19 associated pulmonary aspergillosis. Mycoses. 2020;63(6):528–34. 10.1111/myc.13096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lian J, Jin X, Hao S, Cai H, Zhang S, Zheng L, et al. Analysis of Epidemiological and Clinical features in older patients with Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) out of Wuhan. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu Y, Yang Y, Zhang C, Huang F, Wang F, Yuan J, et al. Clinical and biochemical indexes from 2019-nCoV infected patients linked to viral loads and lung injury. Sci China Life Sci. 2020;63(3):364–74. 10.1007/s11427-020-1643-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lv Z, Cheng S, Le J, Huang J, Feng L, Zhang B, et al. Clinical characteristics and co-infections of 354 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Microbes Infect. 2020. 10.1016/j.micinf.2020.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ma S, Lai X, Chen Z, Tu S, Qin K. Clinical Characteristics of Critically Ill Patients Co-infected with SARS-CoV-2 and the Influenza Virus in Wuhan, China. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2020. 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.05.068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mannheim J, Gretsch S, Layden JE, Fricchione MJ. Characteristics of Hospitalized Pediatric COVID-19 Cases—Chicago, Illinois, March—April 2020. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mo P, Xing Y, Xiao Y, Deng L, Zhao Q, Wang H, et al. Clinical characteristics of refractory COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2020. 10.1093/cid/ciaa270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ozaras R, Cirpin R, Duran A, Duman H, Arslan O, Bakcan Y, et al. Influenza and COVID-19 Co-infection: Report of 6 cases and review of the Literature. Journal of Medical Virology. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Palmieri L, Vanacore N, Donfrancesco C, Lo Noce C, Canevelli M, Punzo O, et al. Clinical Characteristics of Hospitalized Individuals Dying with COVID-19 by Age Group in Italy. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2020. 10.1093/gerona/glaa140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peng H, Gao P, Xu Q, Liu M, Peng J, Wang Y, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 in children: Characteristics, antimicrobial treatment, and outcomes. Journal of Clinical Virology. 2020;128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pongpirul WA, Mott JA, Woodring JV, Uyeki TM, MacArthur JR, Vachiraphan A, et al. Clinical Characteristics of Patients Hospitalized with Coronavirus Disease, Thailand. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2020;26(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, Crawford JM, McGinn T, Davidson KW, et al. Presenting Characteristics, Comorbidities, and Outcomes Among 5700 Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19 in the New York City Area. Jama. 2020;323(20):2052–9. 10.1001/jama.2020.6775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sun D, Chen X, Li H, Lu XX, Xiao H, Zhang FR, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection in infants under 1 year of age in Wuhan City, China. World Journal of Pediatrics. 2020:1–7. 10.1007/s12519-020-00368-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tagarro A, Epalza C, Santos M, Sanz-Santaeufemia FJ, Otheo E, Moraleda C, et al. Screening and Severity of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Children in Madrid, Spain. JAMA Pediatr. 2020. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wan S, Xiang Y, Fang W, Zheng Y, Li B, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features and treatment of COVID-19 patients in northeast Chongqing. Journal of Medical Virology. 2020;92(7):797–806. 10.1002/jmv.25783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang Y, Liu Y, Liu L, Wang X, Luo N, Li L. Clinical Outcomes in 55 Patients With Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Who Were Asymptomatic at Hospital Admission in Shenzhen, China. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2020;221(11):1770–4. 10.1093/infdis/jiaa119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang L, He W, Yu X, Hu D, Bao M, Liu H, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 in elderly patients: Characteristics and prognostic factors based on 4-week follow-up. J Infect. 2020;80(6):639–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang R, Pan M, Zhang X, Han M, Fan X, Zhao F, et al. Epidemiological and clinical features of 125 Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19 in Fuyang, Anhui, China. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2020;95:421–8. 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang Y, Zhang D, Du G, Du R, Zhao J, Jin Y, et al. Remdesivir in adults with severe COVID-19: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2020;395(10236):1569–78. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31022-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wee LE, Ko KKK, Ho WQ, Kwek GTC, Tan TT, Wijaya L. Community-acquired viral respiratory infections amongst hospitalized inpatients during a COVID-19 outbreak in Singapore: co-infection and clinical outcomes. Journal of clinical virology: the official publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology. 2020;128:104436. 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, Xia J, Zhou X, Xu S, et al. Risk Factors Associated With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and Death in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. 2020. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xia W, Shao J, Guo Y, Peng X, Li Z, Hu D. Clinical and CT features in pediatric patients with COVID-19 infection: Different points from adults. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2020;55(5):1169–74. 10.1002/ppul.24718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, Shu H, Xia J, Liu H, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(5):475–81. 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yi SG, Rogers AW, Saharia A, Aoun M, Faour R, Abdelrahim M, et al. Early Experience With COVID-19 and Solid Organ Transplantation at a US High-volume Transplant Center. Transplantation. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang JJ, Dong X, Cao YY, Yuan YD, Yang YB, Yan YQ, et al. Clinical characteristics of 140 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan, China. Allergy. 2020. 10.1111/all.14238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang G, Hu C, Luo L, Fang F, Chen Y, Li J, et al. Clinical features and short-term outcomes of 221 patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Journal of clinical virology: the official publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology. 2020;127:104364. 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhao D, Yao F, Wang L, Zheng L, Gao Y, Ye J, et al. A comparative study on the clinical features of COVID-19 pneumonia to other pneumonias. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2020. 10.1093/cid/ciaa247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zheng X, Wang H, Su Z, Li W, Yang D, Deng F, et al. Co-infection of SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza virus in Early Stage of the COVID-19 Epidemic in Wuhan, China. Journal of Infection. 2020. 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.05.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–62. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhu X, Ge Y, Wu T, Zhao K, Chen Y, Wu B, et al. Co-infection with respiratory pathogens among COVID-2019 cases. Virus Research. 2020;285. 10.1016/j.virusres.2020.198005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Alvares PA. SARS-COV-2 AND RESPIRATORY SYNCYTIAL VIRUS COINFECTION IN HOSPITALIZED PEDIATRIC PATIENTS. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2021. 10.1097/INF.0000000000003057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Borman AM, Palmer MD, Fraser M, Patterson Z, Mann C, Oliver D, et al. COVID-19-Associated Invasive Aspergillosis: Data from the UK National Mycology Reference Laboratory. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2020;59(1). 10.1128/JCM.02136-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chauhdary WA, Chong PL, Mani BI, Asli R, Momin RN, Abdullah MS, et al. Primary Respiratory Bacterial Coinfections in Patients with COVID-19. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 2020;103(2):917–9. 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cheng LS, Chau SK, Tso EY, Tsang SW, Li IY, Wong BK, et al. Bacterial co-infections and antibiotic prescribing practice in adults with COVID-19: experience from a single hospital cluster. Ther Adv Infect Dis. 2020;7:2049936120978095. 10.1177/2049936120978095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cheng Y, Ma J, Wang H, Wang X, Hu Z, Li H, et al. Co-infection of influenza A virus and SARS-CoV-2: A retrospective cohort study. Journal of Medical Virology. 2021. 10.1002/jmv.26817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cheng K, He M, Shu Q, Wu M, Chen C, Xue Y. Analysis of the Risk Factors for Nosocomial Bacterial Infection in Patients with COVID-19 in a Tertiary Hospital. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy. 2020;13:2593–9. 10.2147/RMHP.S277963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Contou D, Claudinon A, Pajot O, Micaelo M, Longuet Flandre P, Dubert M, et al. Bacterial and viral co-infections in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia admitted to a French ICU. Annals of intensive care. 2020;10(1):119. 10.1186/s13613-020-00736-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dupont D, Menotti J, Turc J, Miossec C, Wallet F, Richard JC, et al. Pulmonary aspergillosis in critically ill patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Medical Mycology. 2021;59(1):110–4. 10.1093/mmy/myaa078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Elabbadi A, Turpin M, Gerotziafas GT, Teulier M, Voiriot G, Fartoukh M. Bacterial coinfection in critically ill COVID-19 patients with severe pneumonia. Infection. 2021. 10.1007/s15010-020-01553-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Falces-Romero I, Ruiz-Bastián M, Díaz-Pollán B, Maseda E, García-Rodríguez J. Isolation of Aspergillus spp. in respiratory samples of patients with COVID-19 in a Spanish Tertiary Care Hospital. Mycoses. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Falcone M, Tiseo G, Giordano C, Leonildi A, Menichini M, Vecchione A, et al. Predictors of hospital-acquired bacterial and fungal superinfections in COVID-19: a prospective observational study. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fu Y, Yang Q, Xu M, Kong H, Chen H, Fu Y, et al. Secondary Bacterial Infections in Critical Ill Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7(6):ofaa220. 10.1093/ofid/ofaa220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Garcia-Menino I, Forcelledo L, Rosete Y, Garcia-Prieto E, Escudero D, Fernandez J. Spread of OXA-48-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae among COVID-19-infected patients: The storm after the storm. Journal of infection and public health. 2021;14(1):50–2. 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Garcia-Vidal C, Sanjuan G, Moreno-Garcia E, Puerta-Alcalde P, Garcia-Pouton N, Chumbita M, et al. Incidence of co-infections and superinfections in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27(1):83–8. 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.07.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gouzien L, Cocherie T, Eloy O, Legriel S, Bedos JP, Simon C, et al. Invasive Aspergillosis Associated with severe COVID-19: A Word of Caution. Infect Dis Now. 2021. 10.1016/j.idnow.2020.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hashemi SA, Safamanesh S, Ghasemzadeh-Moghaddam H, Ghafouri M, Azimian A. High prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 and influenza A virus (H1N1) coinfection in dead patients in Northeastern Iran. Journal of Medical Virology. 2021;93(2):1008–12. 10.1002/jmv.26364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hazra A, Collison M, Pisano J, Kumar M, Oehler C, Ridgway JP. Coinfections with SARS-CoV-2 and other respiratory pathogens. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020;41(10):1228–9. 10.1017/ice.2020.322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.He B, Wang J, Wang Y, Zhao J, Huang J, Tian Y, et al. The Metabolic Changes and Immune Profiles in Patients With COVID-19. Frontiers in Immunology. 2020;11:2075. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.02075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hirotsu Y, Maejima M, Shibusawa M, Amemiya K, Nagakubo Y, Hosaka K, et al. Analysis of Covid-19 and non-Covid-19 viruses, including influenza viruses, to determine the influence of intensive preventive measures in Japan. Journal of Clinical Virology. 2020;129:104543. 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hughes S, Troise O, Donaldson H, Mughal N, Moore LSP. Bacterial and fungal coinfection among hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study in a UK secondary-care setting. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2020;26(10):1395–9. 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.06.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Karaba SM, Jones G, Helsel T, Smith LL, Avery R, Dzintars K, et al. Prevalence of Co-infection at the Time of Hospital Admission in COVID-19 Patients, A Multicenter Study. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8(1):ofaa578. 10.1093/ofid/ofaa578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kolenda C, Ranc AG, Boisset S, Caspar Y, Carricajo A, Souche A, et al. Assessment of Respiratory Bacterial Coinfections Among Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2-Positive Patients Hospitalized in Intensive Care Units Using Conventional Culture and BioFire, FilmArray Pneumonia Panel Plus Assay. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7(11):ofaa484. 10.1093/ofid/ofaa484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kumar G, Adams A, Hererra M, Rojas ER, Singh V, Sakhuja A, et al. Predictors and outcomes of healthcare-associated infections in COVID-19 patients. International journal of infectious diseases: IJID: official publication of the International Society for Infectious Diseases. 2021;104:287–92. 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.11.135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lardaro T, Wang AZ, Bucca A, Croft A, Glober N, Holt DB, et al. Characteristics of COVID-19 Patients with Bacterial Co-infection Admitted to the Hospital from the Emergency Department in a Large Regional Healthcare System. Journal of Medical Virology. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lehmann CJ, Pho MT, Pitrak D, Ridgway JP, Pettit NN. Community Acquired Co-infection in COVID-19: A Retrospective Observational Experience. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lendorf ME, Boisen MK, Kristensen PL, Lokkegaard ECL, Krog SM, Brandi L, et al. Characteristics and early outcomes of patients hospitalised for COVID-19 in North Zealand, Denmark. Dan Med J. 2020;67(9). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Li J, Wang J, Yang Y, Cai P, Cao J, Cai X, et al. Etiology and antimicrobial resistance of secondary bacterial infections in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective analysis. Antimicrobial resistance and infection control. 2020;9(1):153. 10.1186/s13756-020-00819-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Li Z, Chen ZM, Chen LD, Zhan YQ, Li SQ, Cheng J, et al. Coinfection with SARS-CoV-2 and other respiratory pathogens in patients with COVID-19 in Guangzhou, China. J Med Virol. 2020;92(11):2381–3. 10.1002/jmv.26073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ma L, Wang W, Le Grange JM, Wang X, Du S, Li C, et al. Coinfection of SARS-CoV-2 and Other Respiratory Pathogens. Infect Drug Resist. 2020;13:3045–53. 10.2147/IDR.S267238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mahmoudi H. Bacterial co-infections and antibiotic resistance in patients with COVID-19. GMS hygiene and infection control. 2020;15:Doc35. 10.3205/dgkh000370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Goncalves Mendes Neto A, Lo KB, Wattoo A, Salacup G, Pelayo J, DeJoy R, 3rd, et al. Bacterial infections and patterns of antibiotic use in patients with COVID-19. J Med Virol. 2021;93(3):1489–95. 10.1002/jmv.26441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mughal MS, Kaur IP, Jaffery AR, Dalmacion DL, Wang C, Koyoda S, et al. COVID-19 patients in a tertiary US hospital: Assessment of clinical course and predictors of the disease severity. Respir Med. 2020;172:106130. 10.1016/j.rmed.2020.106130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Nasir N, Mahmood F, Habib K, Khanum I, Jamil B. Tocilizumab for COVID-19 Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: Outcomes Assessment Using the WHO Ordinal Scale. Cureus. 2020;12(12):e12290. 10.7759/cureus.12290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Nasir N, Farooqi J, Mahmood SF, Jabeen K. COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA) in patients admitted with severe COVID-19 pneumonia: An observational study from Pakistan. Mycoses. 2020;63(8):766–70. 10.1111/myc.13135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ng KF, Bandi S, Bird PW, Wei-Tze Tang J. COVID-19 in Neonates and Infants: Progression and Recovery. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2020;39(7):e140–e2. 10.1097/INF.0000000000002738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Nori P, Cowman K, Chen V, Bartash R, Szymczak W, Madaline T, et al. Bacterial and fungal coinfections in COVID-19 patients hospitalized during the New York City pandemic surge. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 2021;42(1):84–8. 10.1017/ice.2020.368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Obata R, Maeda T, Do DR, Kuno T. Increased secondary infection in COVID-19 patients treated with steroids in New York City. Japanese journal of infectious diseases. 2020. 10.7883/yoken.JJID.2020.884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Oliva A, Siccardi G, Migliarini A, Cancelli F, Carnevalini M, D’Andria M, et al. Co-infection of SARS-CoV-2 with Chlamydia or Mycoplasma pneumoniae: a case series and review of the literature. Infection. 2020;48(6):871–7. 10.1007/s15010-020-01483-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Papamanoli A, Yoo J, Grewal P, Predun W, Hotelling J, Jacob R, et al. High-dose methylprednisolone in nonintubated patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia. European journal of clinical investigation. 2021;51(2):e13458. 10.1111/eci.13458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Peci A, Tran V, Guthrie JL, Li Y, Nelson P, Schwartz KL, et al. Prevalence of Co-Infections with Respiratory Viruses in Individuals Investigated for SARS-CoV-2 in Ontario, Canada. Viruses. 2021;13(1). 10.3390/v13010130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Pereira MR, Aversa MM, Farr MA, Miko BA, Aaron JG, Mohan S, et al. Tocilizumab for severe COVID-19 in solid organ transplant recipients: a matched cohort study. American Journal of Transplantation. 2020;20(11):3198–205. 10.1111/ajt.16314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Pettit NN, Nguyen CT, Mutlu GM, Wu D, Kimmig L, Pitrak D, et al. Late onset infectious complications and safety of tocilizumab in the management of COVID-19. J Med Virol. 2021;93(3):1459–64. 10.1002/jmv.26429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Pickens CO, Gao CA, Cuttica M, Smith SB, Pesce L, Grant R, et al. Bacterial superinfection pneumonia in SARS-CoV-2 respiratory failure. medRxiv. 2021. 10.1101/2021.01.12.20248588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ramadan HK, Mahmoud MA, Aburahma MZ, Elkhawaga AA, El-Mokhtar MA, Sayed IM, et al. Predictors of Severity and Co-Infection Resistance Profile in COVID-19 Patients: First Report from Upper Egypt. Infect Drug Resist. 2020;13:3409–22. 10.2147/IDR.S272605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Rieg S, von Cube M, Kalbhenn J, Utzolino S, Pernice K, Bechet L, et al. COVID-19 in-hospital mortality and mode of death in a dynamic and non-restricted tertiary care model in Germany. PloS one. 2020;15(11):e0242127. 10.1371/journal.pone.0242127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ripa M, Galli L, Poli A, Oltolini C, Spagnuolo V, Mastrangelo A, et al. Secondary infections in patients hospitalized with COVID-19: incidence and predictive factors. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2020. 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.10.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Rothe K, Feihl S, Schneider J, Wallnofer F, Wurst M, Lukas M, et al. Rates of bacterial co-infections and antimicrobial use in COVID-19 patients: a retrospective cohort study in light of antibiotic stewardship. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021;40(4):859–69. 10.1007/s10096-020-04063-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Segrelles-Calvo G, Araujo GRS, Llopis-Pastor E, Carrillo J, Hernandez-Hernandez M, Rey L, et al. Prevalence of opportunistic invasive aspergillosis in COVID-19 patients with severe pneumonia. Mycoses. 2021;64(2):144–51. 10.1111/myc.13219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Sharifipour E, Shams S, Esmkhani M, Khodadadi J, Fotouhi-Ardakani R, Koohpaei A, et al. Evaluation of bacterial co-infections of the respiratory tract in COVID-19 patients admitted to ICU. BMC infectious diseases. 2020;20(1):646. 10.1186/s12879-020-05374-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Sogaard KK, Baettig V, Osthoff M, Marsch S, Leuzinger K, Schweitzer M, et al. Community-acquired and hospital-acquired respiratory tract infection and bloodstream infection in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 pneumonia. J Intensive Care. 2021;9(1):10. 10.1186/s40560-021-00526-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Soriano MC, Vaquero C, Ortiz-Fernandez A, Caballero A, Blandino-Ortiz A, de Pablo R. Low incidence of co-infection, but high incidence of ICU-acquired infections in critically ill patients with COVID-19. The Journal of infection. 2021;82(2):e20–e1. 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.09.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Tang ML, Li YQ, Chen X, Lin H, Jiang ZC, Gu DL, et al. Co-Infection with Common Respiratory Pathogens and SARS-CoV-2 in Patients with COVID-19 Pneumonia and Laboratory Biochemistry Findings: A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Study of 78 Patients from a Single Center in China. Med Sci Monit. 2021;27:e929783. 10.12659/MSM.929783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Torrego A, Pajares V, Fernandez-Arias C, Vera P, Mancebo J. Bronchoscopy in Patients with COVID-19 with Invasive Mechanical Ventilation: A Single-Center Experience. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(2):284–7. 10.1164/rccm.202004-0945LE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Townsend L, Hughes G, Kerr C, Kelly M, O’Connor R, Sweeney E, et al. Bacterial pneumonia coinfection and antimicrobial therapy duration in SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) infection. JAC Antimicrob Resist. 2020;2(3):dlaa071. 10.1093/jacamr/dlaa071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Verroken A, Scohy A, Gerard L, Wittebole X, Collienne C, Laterre PF. Co-infections in COVID-19 critically ill and antibiotic management: a prospective cohort analysis. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):410. 10.1186/s13054-020-03135-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Wang L, Amin AK, Khanna P, Aali A, McGregor A, Bassett P, et al. An observational cohort study of bacterial co-infection and implications for empirical antibiotic therapy in patients presenting with COVID-19 to hospitals in North West London. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Wei L, Gao X, Chen S, Zeng W, Wu J, Lin X, et al. Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes of Childbearing-Age Women With COVID-19 in Wuhan: Retrospective, Single-Center Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2020;22(8):e19642. 10.2196/19642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.White PL, Dhillon R, Cordey A, Hughes H, Faggian F, Soni S, et al. A national strategy to diagnose COVID-19 associated invasive fungal disease in the ICU. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2020. 10.1093/cid/ciaa1298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Wu Q, Xing Y, Shi L, Li W, Gao Y, Pan S, et al. Coinfection and Other Clinical Characteristics of COVID-19 in Children. Pediatrics. 2020;146(1). 10.1542/peds.2020-0961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Xia P, Wen Y, Duan Y, Su H, Cao W, Xiao M, et al. Clinicopathological Features and Outcomes of Acute Kidney Injury in Critically Ill COVID-19 with Prolonged Disease Course: A Retrospective Cohort. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31(9):2205–21. 10.1681/ASN.2020040426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Xu J, Yang X, Yang L, Zou X, Wang Y, Wu Y, et al. Clinical course and predictors of 60-day mortality in 239 critically ill patients with COVID-19: a multicenter retrospective study from Wuhan, China. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):394. 10.1186/s13054-020-03098-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Xu S, Shao F, Bao B, Ma X, Xu Z, You J, et al. Clinical Manifestation and Neonatal Outcomes of Pregnant Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7(7):ofaa283. 10.1093/ofid/ofaa283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Xu W, Sun NN, Gao HN, Chen ZY, Yang Y, Ju B, et al. Risk factors analysis of COVID-19 patients with ARDS and prediction based on machine learning. Scientific reports. 2021;11(1):2933. 10.1038/s41598-021-82492-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Yao T, Gao Y, Cui Q, Peng B, Chen Y, Li J, et al. Clinical characteristics of a group of deaths with COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a retrospective case series. BMC infectious diseases. 2020;20(1):695. 10.1186/s12879-020-05423-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Yu C, Zhang Z, Guo Y, Shi J, Pei G, Yao Y, et al. Lopinavir/ritonavir is associated with pneumonia resolution in COVID-19 patients with influenza coinfection: A retrospective matched-pair cohort study. J Med Virol. 2021;93(1):472–80. 10.1002/jmv.26260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Yue H, Zhang M, Xing L, Wang K, Rao X, Liu H, et al. The epidemiology and clinical characteristics of co-infection of SARS-CoV-2 and influenza viruses in patients during COVID-19 outbreak. Journal of Medical Virology. 2020;92(11):2870–3. 10.1002/jmv.26163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Yusuf E, Vonk A, van den Akker JPC, Bode L, Sips GJ, Rijnders BJA, et al. Frequency of Positive Aspergillus Tests in COVID-19 Patients in Comparison to Other Patients with Pulmonary Infections Admitted to the ICU. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Zhang C, Gu J, Chen Q, Deng N, Li J, Huang L, et al. Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of pediatric SARS-CoV-2 infections in China: A multicenter case series. PLoS Medicine. 2020;17(6):e1003130. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Zhang H, Zhang Y, Wu J, Li Y, Zhou X, Li X, et al. Risks and features of secondary infections in severe and critical ill COVID-19 patients. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9(1):1958–64. 10.1080/22221751.2020.1812437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Joseph C, Togawa Y, Shindo N. Bacterial and viral infections associated with influenza. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2013;7 Suppl 2:105–13. 10.1111/irv.12089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]