Abstract

Objective

This study examines changes over time in the prevalence of select sexual behaviors and contraceptive use measures in a national sample of U.S. adolescents.

Study design

We used data on adolescents aged 15-19 from the 2006-2010 (n=4,662), 2011-2015 (n=4,134), and 2015-2019 (n=3,182) National Surveys of Family Growth. We used logistic regression to identify changes between periods in sexual behaviors and contraceptive use by gender, and for some measures by age. We estimated probabilities of age at first penile-vaginal intercourse with Kaplan-Meier failure analysis.

Results

Over half of adolescents have engaged in at least one of the sexual behaviors measured. Males reported declines in sexual behaviors with a partner of a different sex. Adolescent males reported delays in the timing of first penile-vaginal intercourse. Adolescent females reported increases from 2006-2010 to 2015-2019 in use at last intercourse of any contraceptive method (86%, 95%CI 83-89; 91%, 95%CI 88-94), multiple methods (26%, 95%CI 22-31; 36%, 95%CI 30-43), and IUDs or implants (3%, 95%CI 1-4; 15%, 95%CI 11-20). Adolescent males reported increases in partners' use of IUDs or implants use from <1% to 5% and recent declines in condom use at last intercourse (78%, 95%CI 75-82, 2011-2015; 72%, 95%CI 67-77, 2015-2019). Condom consistency declined over time. Males were more likely than females to report condom use at last intercourse and consistent condom use in the last 12 months.

Conclusions

These findings identify declines in male adolescent sexual experience, increased contraceptive use overall, and declines in consistent condom use from 2006 to 2019.

Implications

This analysis contributes a timely update on adolescent sexual behavior trends and contraceptive use, showing that adolescent behaviors are complex and evolving. Sexual health information and services must be available so that young people have the resources to make healthy and responsible choices for themselves and their partners.

Keywords: Adolescents, Contraceptive use, Sexual behaviors, Sexual and reproductive health, Surveillance, Surveys

1. Introduction

Sexual development is a critical part of adolescence, and support for young people's healthy sexual development is essential. National public health goals for adolescent sexual behaviors in the United States (U.S.) take a narrow approach, with specific targets for reducing adolescent sexual activity and increasing contraceptive use [1]. Policies addressing adolescent sexual and reproductive health often do not acknowledge the positive and developmentally appropriate aspects of adolescent sexuality [2]. Research to date has mostly focused on adolescent female behaviors, emphasizing pregnancy risk reduction, despite the availability of national data on sexual and contraceptive behaviors for both genders. Surveillance efforts often focus on first coital experience and typically overlook adolescent engagement in sexual activity other than penile-vaginal intercourse [3,4].

Ongoing monitoring has documented national trends in adolescent sexual behaviors, contraceptive use, and the associated outcomes of pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Analyses of the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) among never-married adolescents have documented a stable proportion of females engaging in penile-vaginal intercourse since 2002, but some declines in this behavior among males [5]. Prior studies have examined adolescent engagement in other sexual behaviors but have not conducted investigation of recent trends [6,7]. Other surveillance has documented increases in the use of long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods, as well as declines in contraceptive non-use, among females ages 15-19 from 2007 to 2014, but more recent surveillance is lacking [8].

This study updates and expands earlier surveillance, using nationally representative data collected from 2006-2019 to examine trends in sexual behaviors and contraceptive use among U.S. adolescents aged 15-19. We extend the focus from prior research to include sexual behaviors beyond penile-vaginal intercourse and examine changes in the contraceptive method mix and consistency of condom use. Where possible, we test for differences by gender and age to provide further insights into changes in adolescent sexual experiences over time. Findings from this study can inform policy and research efforts that support adolescent sexual and reproductive health and well-being more broadly.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Data and measures

The NSFG is a periodic national probability survey of the noninstitutionalized population of women and mena ages 15 to 49 years in the U.S., conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics. The NSFG uses a multistage probability sampling design that oversamples Black and Hispanic groups and adolescents aged 15-19. It collects detailed information on fertility-related behaviors, including sexual activity and contraceptive use. More detailed information on survey methodology is published elsewhere [9]. We use data from interviews conducted continuously from June 2006-September 2019, divided into distinct four-year periods. We limit analyses to respondents aged 15-19, resulting in samples of n=4,662 in 2006-2010, 4,134 in 2011-2015, and 3,182 in 2015-2019.

Measures of penile-vaginal intercourse, age at first intercourse, contraceptive use at last intercourse in the last 12 months, and consistency of condom use during the last 12 months were drawn from the face-to-face interviews. Other sexual behaviors (oral or anal sex with a partner of a different sex and sexual experience with a same-sex partnerb) were measured via the audio computer-assisted self-interviews (ACASI).

2.2. Data analysis

We estimated the prevalence of each outcome and the associated 95% confidence interval (CI) by gender and period. For measures of sexual activity, we also tested for variation within period by age; subsample sizes were too small for robust estimation of age variations in contraceptive use. Additionally, we used Kaplan-Meier failure analysis to estimate the probabilities of age at first penile-vaginal intercourse by gender, expanding on prior estimates [5,10]. We included respondents age 15-24 to account for censoring and use Cox regression-based tests for equality in the survival curves.

We used sampling weights to make the data representative of three distinct periods (2006-2010, 2011-2015, 2015-2019c) and adjusted for survey design and sampling using the svy command in Stata 16.0 [11]. Because our analysis used existing publicly available, deidentified data, the Guttmacher institutional review board granted this study exempt status.

3. Results

3.1. Sexual behaviors

In 2015-2019, more than half of adolescents (54% F, 52% M) had some sexual experience, engaging in at least one of the four types of sexual behaviors examined (Table 1). For both genders, penile-vaginal intercourse (41% F, 39% M) or oral sex with a partner of a different sex (44% F, 43% M) was more common than anal sex with a partner of a different sex (9% F, 8% M) or sexual experience with a same-sex partner (15% F, 3% M).

Table 1.

Percentage of females and males aged 15-19 who engaged in specific sexual behaviors, 2006–2019 National Survey of Family Growth

| Females, % | Males, % | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006-2010 | 95% CI | 2011-2015 | 95% CI | 2015-2019 | 95% CI | 2006-2010 | 95% CI | 2011-2015 | 95% CI | 2015-2019 | 95% CI | |

| Unweighted | (n=2,284) | (n=2,047) | (n=1,894) | (n=2,378) | (n=2,087) | (n=1,918) | ||||||

| Weighted | (N=10,477,877) | (N=9,482,466) | (N=9,439,433) | (N=10,816,496) | (N=9,997,062) | (N=9,901,887) | ||||||

| Any sexual experiencea | ||||||||||||

| Total | 56 | (52, 59) | 57 | (53, 60) | 54 | (50, 58) | 59 | (56, 62) | 58 | (55, 61) | 52 | (49, 56) |

| 15-17 years | 42 | (38, 46) | 44 | (39, 48) | 41 | (36, 46) | 47 | (43, 51) | 48 | (44, 52) | 39 | (35, 43) |

| 18-19 years | 73 | (68, 78) | 75 | (70, 79) | 71 | (65, 77) | 76 | (73, 80) | 74 | (70, 79) | 71 | (66, 76) |

| Ever had penile vaginal intercourse with partner of different sex | ||||||||||||

| Total | 43 | (40, 47) | 43 | (39, 47) | 41 | (37, 45) | 42 | (39, 45) | 44 | (42, 47) | 39 | (35, 43) |

| 15-17 years | 27 | (24, 31) | 28 | (24, 32) | 25 | (21, 29) | 28 | (24, 31) | 31 | (28, 35) | 23 | (19, 27) |

| 18-19 years | 64 | (58, 69) | 64 | (59, 69) | 63 | (57, 69) | 64 | (60, 69) | 65 | (60, 70) | 60 | (55, 66) |

| Ever had oral sex with partner of different sex | ||||||||||||

| Total | 47 | (44, 50) | 45 | (41, 49) | 44 | (40, 48) | 48 | (45, 52) | 51 | (48, 55) | 43 | (40, 47) |

| 15-17 years | 32 | (28, 36) | 33 | (28, 37) | 31 | (27, 36) | 38 | (34, 41) | 41 | (37, 44) | 30 | (27, 34) |

| 18-19 years | 65 | (61, 70) | 62 | (57, 68) | 62 | (56, 68) | 65 | (60, 71) | 68 | (63, 73) | 61 | (56, 66) |

| Ever had anal sex with partner of different sex | ||||||||||||

| Total | 12 | (10, 13) | 11 | (9, 13) | 9 | (7, 12) | 10 | (9, 12) | 11 | (9, 12) | 8 | (6, 9) |

| 15-17 years | 8 | (6, 9) | 6 | (4, 8) | 4 | (3, 6) | 6 | (4, 7) | 8 | (6, 10) | 4 | (3, 6) |

| 18-19 years | 17 | (14, 20) | 18 | (13, 22) | 17 | (12, 21) | 18 | (14, 21) | 15 | (12, 19) | 12 | (9, 16) |

| Ever had a sexual experience with a same sex partner | ||||||||||||

| Total | 12 | (10, 13) | 12 | (10, 14) | 15 | (12, 17) | 3 | (2, 4) | 2 | (1, 2) | 3 | (2, 4) |

| 15-17 years | 10 | (8, 12) | 10 | (8, 12) | 11 | (9, 13) | 2 | (1, 3) | 1 | (1, 2) | 3 | (2, 4) |

| 18-19 years | 14 | (11, 17) | 14 | (11, 18) | 19 | (15, 23) | 4 | (3, 6) | 2 | (1, 4) | 4 | (2, 6) |

This includes vaginal, oral, and anal sex with any partner.a

In each period, there were consistent demographic differentials. Each sexual behavior had large differentials by age. Females were more likely than males to report same-sex activity, regardless of age group. Other sexual behaviors varied little by gender.

The changes over time in these sexual behaviors were concentrated in the most recent period and varied by gender and age. For males overall, rates of all behaviors were stable between 2006-2010 and 2011-2015. By 2015-2019 there were declines in the proportion reporting any sexual experience, penile-vaginal intercourse, and oral sex with a partner of a different sex. The change in intercourse was concentrated among males ages 15-17, declining from 31% (95%CI 28-35) in 2011-2015 to 23% (95%CI 19-27) in 2015-2019. Males in this younger age group reported declines in each sexual behavior with a partner of a different sex. Males in both age groups reported a modest increase in sexual experience with a male partner.

There were few changes in these sexual behaviors over time among females. Anal sex declined among females ages 15-17 from 2006-2010 to 2015-2019 (8%, 95%CI 6-9 vs. 4%, 95%CI 4-8). Additionally, the overall share of females reporting a sexual experience with another female increased from 12% (95%CI 10-13) to 15% (95%CI 12-17).

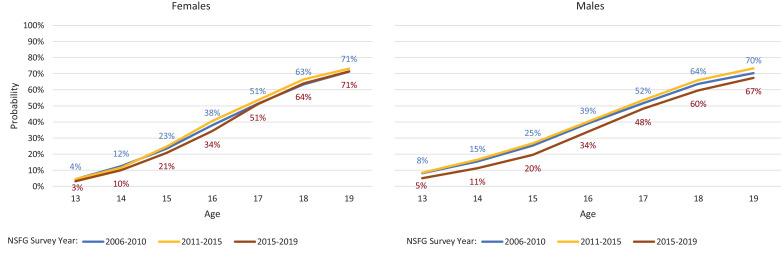

Comparison between periods finds a slower onset of first penile-vaginal intercourse in the most recent period among males (Fig. 1); the log-rank tests indicate changes over time in the cumulative probabilities (p<.0002, not shown). These changes are most pronounced before age 17, particularly for males; for example, the share of males reporting intercourse at age 16 declined from 39% in 2006-2010 to 34% in 2015-2019. Changes over time are more modest among females (Fig. 1). Still, about 70% of adolescents have engaged in intercourse at age 19 in each period. Within each period, the log-rank tests indicate no difference by gender in the timing of first intercourse (not shown).

Fig. 1.

Cumulative probability of age at first penile-vaginal intercourse, by single year of age among females and males aged 15–24, 2006–2019 National Survey of Family Growth.

3.2. Contraceptive use

The share of adolescent women reporting that they or their partner used a contraceptive method as last intercourse in the prior 12 months increased slightly from 2006-2010 to 2015-2019, increasing from 86% (95%CI 83-89) to 91% (95%CI 88-94) (Table 2). Adolescent women reported increases in the use of LARC methods at last sex from 3% (95%CI 1-4) in 2006-2010 to 15% (95%CI 11-20) in 2015-2019. LARC use includes both implants and IUDs; the use of the former increased from less than 1% in 2006-2010 to 10% (95%CI 6-13) in 2015-2019, while IUD use increased from 2% (95%CI 1-4) to 5% (95%CI 3-8). Use of injectables, the pill, and patch or ring did not vary over time. More than half of adolescent females reported that their partner used a condom in each survey period. Withdrawal use increased over time and by 2015-2019, most withdrawal use was combined with another method.

Table 2.

Use of contraception at last penile-vaginal intercourse in the past 12 months among females and males aged 15–19, by method(s) used, 2006–2019 National Survey of Family Growth

| Females, % | Males, % | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006-2010 | 2011-2015 | 2015-2019 | 2006-2010 | 2011-2015 | 2015-2019 | |||||||

| (n=980) | (n=804) | (n=689) | (n=961) | (n=867) | (n=705) | |||||||

| % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | |

| Method Use | ||||||||||||

| Used no method | 14 | (11, 17) | 12 | (9, 15) | 9 | (6, 12) | 7 | (5, 9) | 6 | (4, 7) | 6 | (4, 8) |

| Used any method | 86 | (83, 89) | 88 | (85, 91) | 91 | (88, 94) | 93 | (91, 95) | 94 | (93, 96) | 94 | (92, 96) |

| LARCa | 3 | (1, 4) | 4 | (2, 6) | 15 | (11, 20) | 0 | (0, 1) | 2 | (1, 3) | 5 | (3, 7) |

| IUD | 2 | (1, 4) | 2 | (0, 3) | 5 | (3, 8) | 0 | (0, 1) | 1 | (0, 1) | 2 | (1, 4) |

| Implant | 0 | (0, 0) | 2 | (1, 3) | 10 | (6, 13) | 0 | (0, 0) | 1 | (1, 2) | 2 | (1, 4) |

| Injectables | 8 | (6, 10) | 8 | (6, 10) | 9 | (5, 12) | 6 | (3, 8) | 6 | (4, 8) | 4 | (2, 6) |

| Pill | 28 | (24, 33) | 31 | (26, 36) | 29 | (24, 35) | 38 | (34, 43) | 39 | (34, 43) | 40 | (35, 46) |

| Patch / ring | 4 | (2, 6) | 2 | (0, 4) | 2 | (0, 3) | 2 | (1, 4) | 2 | (1, 3) | 3 | (1, 4) |

| Condom (male) | 54 | (49, 59) | 57 | (51, 63) | 52 | (45, 58) | 77 | (73, 81) | 78 | (75, 82) | 72 | (67, 77) |

| Withdrawal | 17 | (13, 21) | 22 | (17, 27) | 23 | (17, 29) | 19 | (15, 22) | 23 | (19, 27) | 27 | (21, 32) |

| Alone | 8 | (6, 11) | 8 | (5, 11) | 6 | (3, 9) | 3 | (2, 5) | 4 | (3, 6) | 4 | (3, 6) |

| W/other method | 9 | (6, 12) | 13 | (9, 17) | 17 | (12, 22) | 16 | (12, 19) | 19 | (15, 23) | 22 | (17, 27) |

| Other methodb | 1 | (0, 2) | 3 | (2, 4) | 4 | (2, 6) | 2 | (1, 4) | 2 | (1, 3) | 4 | (1, 7) |

| Used 2+ methods | 26 | (22, 31) | 33 | (28, 38) | 36 | (30, 43) | 47 | (42, 51) | 51 | (45, 56) | 50 | (45, 55) |

IUD, implant.

Male sterilization, female condom, emergency contraception, fertility awareness, rhythm, foam/jelly, something else (no 15-19 yr old respondent reported using female sterilization).

Overall, adolescent female reports of use of multiple methods at last intercourse (most often combined use of condoms with LARC or hormonal methods) increased from 26% (95%CI 22-31) to 36% (95%CI 30-43). While condom use remained stable over time, females were less likely to report use of condoms as the most effective method used at last sex in 2015-2019 than 2011-2015 (27% v. 35%, results not shown), due to an increase in combined use with a more effective method.

From 2006-2010 to 2015-2019, males reported a small increase in partners' LARC use, and an increase in withdrawal use from 19% (95%CI 15-22) to 27% (95%CI 21-32). In contrast, reported condom use declined from 78% (95%CI 75-82) in 2010-2015 to 72% (95%CI 67-77) in 2015-2019.

There were consistent gender differences in reported prevalence in each period. Compared with females, males were less likely to report use of implants, but more likely to report use of the pill or the male condom. Additionally, more males reported use of 2 or more methods at last penile-vaginal intercourse than females.

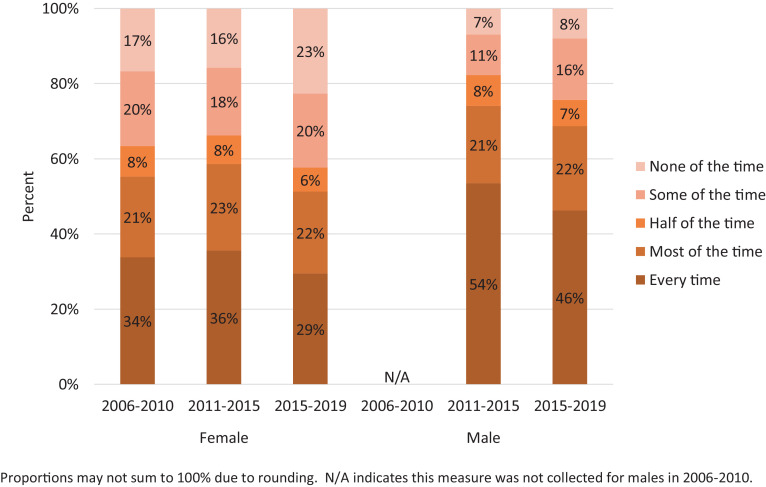

3.3. Condom consistency

Condom consistency during penile-vaginal intercourse in the prior 12 months declined over time (Fig. 2). More adolescent women reported never using a condom during intercourse in the previous 12 months in 2015-2019 than the preceding periods. There was also some decline in reported condom use at every act of intercourse – both among female and males. In years with comparable data, adolescent males were more likely than females to report condom use at every act of intercourse.

Fig. 2.

Consistency of condom use among respondents that had penile-vaginal intercourse in the past 12 months, females and males aged 15-19, by gender and period, 2006-2019 National Survey of Family Growth.

4. Discussion

During the last decade, sexual activity among adolescents has been the normative behavior, with more than half of adolescents engaging in sexual activity, whether penile-vaginal intercourse, oral sex, anal sex, or other activity with a same-sex partner. Differences by age highlight adolescent developmental trajectory, and about three-quarters of older adolescents report having ever engaged in these sexual activities. The most recent period – 2015-2019 – marked emerging declines in the share of males reporting sexual experience, particularly among younger males. In contrast, the general stability in the pattern of sexual behaviors among adolescent females continues long-term trends [8]. More frequent reporting of same-sex partners by adolescent females parallels the gender differential observed in adult populations as well [12]. With nearly one in five females aged 18-19 reporting a same-sex partner in 2015-2019, reporting of this behavior has become increasingly common and likely reflects changing social attitudes about sexuality [13].

This research shows a substantial increase in adolescent LARC use, particularly contraceptive implants, corroborating other recent analyses [14]. Research suggests that adolescents prefer implants over IUDs in part because of the lack of pelvic insertion [15,16]. Given the estimated stability in the proportion of adolescent females engaging in penile-vaginal intercourse, combined with shifts to more effective contraceptive methods, these data further extend the conclusion of earlier studies that improvements in contraceptive use continue to be the critical driver of declines in U.S. adolescent fertility and suggest further declines in adolescent pregnancy rates should be expected [8,17,18]. Additionally, our findings show that increased use of contraceptive methods overall was achieved without any parallel increase in sexual activity, bolstering the body of evidence that improvements in adolescent contraceptive use do not promote sexual activity [17], [18], [19].

The findings around condom use in this study are complicated, reflecting that condoms are coital-dependent methods, use can be episodic, and they are increasingly used in combination with another method. Although about half of young women reported condom use at last sex in each period, as dual method use increased over time, they were less likely to rely on condoms as their most effective method. Additionally, consistent condom use decreased for both genders, which may heighten the risk for STIs. As the share of LARC users grows, there are concerns that they will decrease their condom use [20]. With CDC tracking increases in some STIs among young people, the need for educational and health interventions to promote condom use combined with other highly effective methods continues [21,22].

Many adolescents rely on withdrawal use, primarily in combination with a more effective contraceptive method. Still, the NSFG likely underestimates the extent of withdrawal use. Individuals may not report withdrawal if they do not consider it a formal birth control method or if its use is motivated by non-contraceptive reasons, including sexual pleasure and the relationship's context [23], [24], [25]. In light of the large share of adolescents using withdrawal, health care providers and educators should shift from emphasizing withdrawal as risky and take a harm reduction approach that addresses the probabilities of pregnancy or STI transmission alongside reasons people use it [26]. This approach recognizes adolescent sexual agency and acknowledges withdrawal use as part of a valid contraceptive strategy and other motivations for use beyond pregnancy prevention [25].

This study found substantial gender differences in contraceptive reporting. Females were more likely than males to report LARC and less likely to report pill or condom use. Other studies have also found differences in contraceptive reporting by gender in adult samples [27,28]. Still, the magnitudes were not as consistently large as observed here, suggesting that young people are less knowledgeable of their partners' contraceptive use [30,31]. The CDC's Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) also documents higher reporting of condom use among male, compared to female, high school students [29]. Still, interpretation of the observed differences is unclear, as the individual-level data do not represent partnerships and sexual partners may come from outside this age range. Females are more likely than males to have older partners, which has been associated with different contraceptive use patterns [30]. Greater reporting of condom use by males may also reflect social desirability bias, as this is one of the few methods available to males for pregnancy and STI prevention. Still, the low rates of LARC use reported by males are suggestive that they do not know about their partners' use of these methods or may confuse it with pill use. Discreteness is one of the appeals of these methods [15], but this still raises concerns about a lack of communication about contraception between partners. Supporting adolescent development of communication skills with sexual partners is an essential component of a comprehensive sexual and reproductive health approach [31].

This analysis has limitations. The NSFG data may be subject to self-reporting bias. Due to small sample sizes, we could not examine contraceptive use patterns by age subgroup. Different questions about same-sex behavior between males and females make interpretation of gender differences difficult. Finally, this work is descriptive and does not address the underlying drivers of the observed behaviors. Further research is needed to explore the potential heterogeneity within gender or age groups, focusing especially on structural influences and inequities. Still, this work fills a critical gap, as the valuable surveillance published by the National Center for Health Statistics is limited in scope and frequency.

These findings show the complex and ever-evolving nature of adolescent sexual and reproductive health experiences. Young people deserve access to comprehensive sexual and reproductive health information and services tailored to their developmental, cultural, and logistical needs. Building the evidence base for adolescent sexual and reproductive health can inform public health policies, programs, and practices to help support sexual health and well-being. These findings show how complex and evolving adolescents' sex lives are. Moving forward, the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to have both short-term and longer-term impacts on adolescent sexual experiences and developmental trajectories that warrant new attention [32]. Sexual health information and services must be available so that young people have the resources to make healthy and responsible choices for themselves and their partners.

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest: None.

Funding: Support for this study was provided by an anonymous foundation

All NSFG respondents self-report their current gender at the time of interview, which determines the questionnaire they are routed into. Some individuals may identify as female or male different from their biological sex at birth.

Male respondents were asked specifically about oral or anal sex with a male partner in all survey periods, and additionally asked about any other “sexual experience” with a male partner in 2015-2019; female respondents were asked to report oral sex or any other “sexual experience” with a female partner in all survey periods.

Both the 2011-2015 survey period ended, and the 2015-2019 survey period started, in September 2015.

References

- 1.Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP) U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Department of Health and Human Services (HHS); Washington, D.C.: 2018. Healthy people 2030. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schalet AT. Beyond abstinence and risk: a new paradigm for adolescent sexual health. Womens Health Issues. 2011;21:S5–S7. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holway GV, Brewster KL, Tillman KH. Condom use at first vaginal intercourse among adolescents and young adults in the United States, 2002–2017. J Adolesc Health. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.03.034. S1054139X20301506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cavazos-Rehg PA, Krauss MJ, Spitznagel EL, Schootman M, Bucholz KK, Peipert JF. Age of sexual debut among U.S. adolescents. Contraception. 2009;80:158–162. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martinez GM, Abma JC. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2020. Sexual activity and contraceptive use among teenagers aged 15–19 in the United States, 2015–2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Copen CE, Chandra A, Martínez G. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2012. Prevalence and timing of oral sex with opposite-sex partners among females and males aged 15-24 years: United States, 2007-2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chandra A, Mosher W, Copen C, Sionean C. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyatssville, MD: 2011. Sexual behavior, sexual attraction, and sexual identity in the United States: data from the 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lindberg LD, Santelli JS, Desai S. Changing patterns of contraceptive use and the decline in rates of pregnancy and birth among U.S. adolescents, 2007–2014. J Adolesc Health. 2018;63:253–256. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). NSFG 2015-2017 summary of design and data collection methods 2019.

- 10.Martinez GM, Abma JC. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2015. Sexual activity, contraceptive use, and childbearing of teenagers aged 15–19 in the United States. [Google Scholar]

- 11.StataCorp . StataCorp LLC; College Station, TX: 2019. Stata statistical software: Release 16. [Google Scholar]

- 12.England P, Mishel E, Caudillo M. Increases in sex with same-sex partners and bisexual identity across cohorts of women (but not men) Sociol Sci. 2016;3:951–970. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mishel E, England P, Ford J, Caudillo ML. Cohort increases in sex with same-sex partners: do trends vary by gender, race, and class? Gend Soc. 2020;34:178–209. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kavanaugh ML, Pliskin E. Use of contraception among reproductive-aged women in the United States, 2014 and 2016. FS Rep. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.xfre.2020.06.006. S2666334120300386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kavanaugh ML, Frohwirth L, Jerman J, Popkin R, Ethier K. Long-acting reversible contraception for adolescents and young adults: patient and provider perspectives. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2013;26:86–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Callahan DG, Garabedian LF, Harney KF, DiVasta AD. Will it hurt? The intrauterine device insertion experience and long-term acceptability among adolescents and young women. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2019;32:615–621. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2019.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindberg L, Santelli J, Desai S. Understanding the decline in adolescent fertility in the United States, 2007–2012. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59:577–583. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Santelli JS, Lindberg LD, Finer LB, Singh S. Explaining recent declines in adolescent pregnancy in the United States: the contribution of abstinence and improved contraceptive use. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:150–156. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.089169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meyer JL, Gold MA, Haggerty CL. Advance provision of emergency contraception among adolescent and young adult women: a systematic review of literature. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2011;24:2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Menon S, AAP Committee on Adolescence Long-acting reversible contraception: specific issues for adolescents. Pediatrics. 2020;146 doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-007252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keller LH. Reducing STI cases: young people deserve better sexual health information and services. Guttmacher Policy Rev. 2020;23:7. [Google Scholar]

- 22.CDC. STDs in adolescents and young adults. Sex Transm Dis Surveill 2018 2019. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats18/adolescents.htm (Accessed August 12, 2020).

- 23.Fu T, Hensel DJ, Beckmeyer JJ, Dodge B, Herbenick D. Considerations in the measurement and reporting of withdrawal: findings from the 2018 National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior. J Sex Med. 2019;16:1170–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lindberg L, Jones R, Higgins J. Use of withdrawal among young adults in the U.S.: pulling out all the stops? J Adolesc Health. 2014;54:S61. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones RK, Lindberg LD, Higgins JA. Pull and pray or extra protection? Contraceptive strategies involving withdrawal among U.S. adult women. Contraception. 2014;90:416–421. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laris B, Barrett M, Anderson P, Kesler K, Gerber A, Baumler E. Uncovering withdrawal use among sexually active U.S. adolescents: high prevalence rates suggest the need for a sexual health harm reduction approach. Sex Educ. 2020:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karberg E, Wildsmith E, Manlove J, Johnson M. Do young men's reports of hormonal and long-acting contraceptive method use match their female partner's reports? Contracept X. 2019;1 doi: 10.1016/j.conx.2019.100003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aiken AR, Wang Y, Higgins J, Trussell J. Similarities and differences in contraceptive use reported by women and men in the national survey of family growth. Contraception. 2017;95:419–423. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2016.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2020. Youth risk behavior survey data summary & trends report 2009–2019. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manlove J, Terry-Humen E, Ikramullah E. Young teenagers and older sexual partners: correlates and consequences for males and females. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2006;38:197–207. doi: 10.1363/psrh.38.197.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lalas J, Garbers S, Gold MA, Allegrante JP, Bell DL. Young men's communication with partners and contraception use: a systematic review. J Adolesc Health. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.04.025. S1054139X20302123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lindberg LD, Bell DL, Kantor LM. The sexual and reproductive health of adolescents and young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2020;52:75–79. doi: 10.1363/psrh.12151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]