Abstract

Hedgehogs are synanthropic mammals, reservoirs of several vector-borne pathogens and hosts of ectoparasites. Arthropod-borne pathogens (i.e., Rickettsia spp., Borrelia spp., and Anaplasmataceae) were molecularly investigated in ectoparasites collected on hedgehogs (n = 213) from Iran (161 Hemiechinus auritus, 5 Erinaceus concolor) and Italy (47 Erinaceus europaeus). In Iran, most animals examined (n = 153; 92.2%) were infested by ticks (Rhipicephalus turanicus, Hyalomma dromedarii), and 7 (4.2%) by fleas (Archeopsylla erinacei, Ctenocephalides felis). Of the hedgehogs infested by arthropods in Italy (i.e., 44.7%), 18 (38.3%) were infested by fleas (Ar. erinacei), 7 (14.9%) by ticks (Haemaphysalis erinacei, Rh. turanicus, Rhipicephalus sanguineus sensu lato), and 6 (12.8%) by mites (Caparinia tripilis, Acarus nidicolous, Ornithonyssus spp.). Phoretic behavior of C. tripilis on Ar. erinacei was detected in two flea specimens from Italy. At the molecular analysis Rickettsia spp. was detected in 93.3% of the fleas of Italy. In Iran, Rickettsia spp. was detected in 8.0% out of 212 Rh. turanicus ticks, and in 85.7% of the Ar. erinacei fleas examined. The 16S rRNA gene for Ehrlichia/Anaplasma spp. was amplified in 4.2% of the 212 Rh. turanicus ticks. All sequences of Rickettsia spp. from fleas presented 100% nucleotide identity with Rickettsia asembonensis, whereas Rickettsia spp. from Rh. turanicus presented 99.84%–100% nucleotide identity with Rickettsia slovaca, except for one sequence, identical to Rickettsia massiliae. The sequences of the 16S rRNA gene revealed 99.57%–100% nucleotide identity with Anaplasma spp., except for one, identical to Ehrlichia spp. A new phoretic association between C. tripilis mites and Ar. erinacei fleas has been herein reported, which could be an important route for the spreading of this mite through hedgehog populations. Additionally, spotted fever group rickettsiae were herein detected in ticks and fleas, and Anaplasma/Ehrlichia spp. in ticks, suggesting that hedgehogs play a role as reservoirs for these vector-borne pathogens.

Keywords: Anaplasmataceae, Ectoparasites, Hedgehogs, Phoresy, Rickettsia spp

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

New phoretic association of Caparinia tripilis mites on Archaeopsylla erinacei fleas.

-

•

Occurrence of spotted fever group rickettsiae in Rhipicephalus turanicus from hedgehogs.

-

•

Occurrence of Anaplasmataceae in Rhipicephalus turanicus from hedgehogs.

-

•

High Prevalence of Rickettsia asembonensis in Archaeopsylla erinacei fleas from hedgehogs.

-

•

Hedgehogs are suggested as reservoirs of vector-borne pathogens.

1. Introduction

Wild animals, mainly those presenting synanthropic behavior, are regarded as important reservoirs of pathogens of zoonotic concern (Simpson, 2002; Hassell et al., 2017). For example, hedgehogs thrive in urban, rural, and natural settings, therefore sharing the same environments with domestic animals as well as humans (Skuballa et al., 2007). Among infectious agents, vector-borne pathogens associated with hedgehogs are of major importance, since they are transmitted by ticks, fleas, and mites blood feeding on these animal species as well as on many other mammalian hosts, including humans (Goz et al., 2016).

Beyond their vector role, ectoparasites of hedgehogs may present ecological interactions (i.e., phoresy) which may influence their distribution within mammal hosts. For example, mites may rely on phoretic association with ticks and fleas to spread among vertebrate hosts (Baumann, 2018), also considering their small body size and scant ability to cover large distances. This phenomenon is often described as a form of commensalism (Hodgkin et al., 2010) or even mutualism (Houck and Cohen, 1995); though, arthropod hosts may be negatively influenced by their phoretic companions (Karbowiak et al., 2013), which may impair their usual behaviors in moving, feeding and in reproduction (Blackman and Evans, 1994). Parasitic mites perpetuate in a wide range of mammals, including rats, hamsters, squirrels, marmots, bats, badgers and hedgehogs (Balashov, 2006; Karbowiak et al., 2013). These arthropods are commonly regarded as causative agents of dermatitis on their hosts (Fischer and Walton, 2014). For example, some species such as Caparinia tripilis is known to infest hedgehogs causing skin injuries, especially in conjunction with other infections (Kim et al., 2012). Scabies lesions due to C. tripilis infestation are located in different anatomical sites (i.e., head, ears, abdominal regions and between the limbs) causing skin irritation, inflammation and pruritus, which lead to self-injuries, secondary infections, and even death (Kim et al., 2012; Garcês et al., 2020). In addition, some mite species such as Leptotrombidium spp. and Liponyssoides sanguineus are vectors of zoonotic infectious agents such as Orientia tsutsugamushi, Bartonella tamiae, Rickettsia akari, and Hantaan virus (Houck et al., 2004; Kabeya et al., 2010; Fischer and Walton, 2014).

Likewise, hedgehogs are commonly infested by ticks and fleas (Iacob and Iftinca, 2018; Khodadadi et al., 2021), which are regarded as vectors of zoonotic pathogens, such as Rickettsia, Borrelia, Ehrlichia, Anaplasma and Bartonella species (Regnery et al., 1992; Bouyer et al., 2001; De Sousa et al., 2017; Millán et al., 2019; Julian et al., 2020). Meanwhile, hedgehogs have been suggested as possible reservoirs of zoonotic vector-borne pathogens such as Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato (s.l.), Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Rickettsia helvetica, Leishmania major and tick-borne encephalitis virus (Skuballa et al., 2012; Speck et al., 2013; Krawczyk et al., 2015; Pourmohammadi and Mohammadi-Azni, 2019; Greco et al., 2021). Thus, investigations on the role that ectoparasites of hedgehogs have in spreading arthropod-borne pathogens, as well as on the ecological interactions among them (i.e., phoresy) are required. This study reports the occurrence of C. tripilis in hedgehogs and its phoretic association with Archaeopsylla erinacei fleas, as well as the detection of arthropod-borne pathogens in ticks, fleas and mites collected on these host species in Iran and Italy.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Study area and sampling

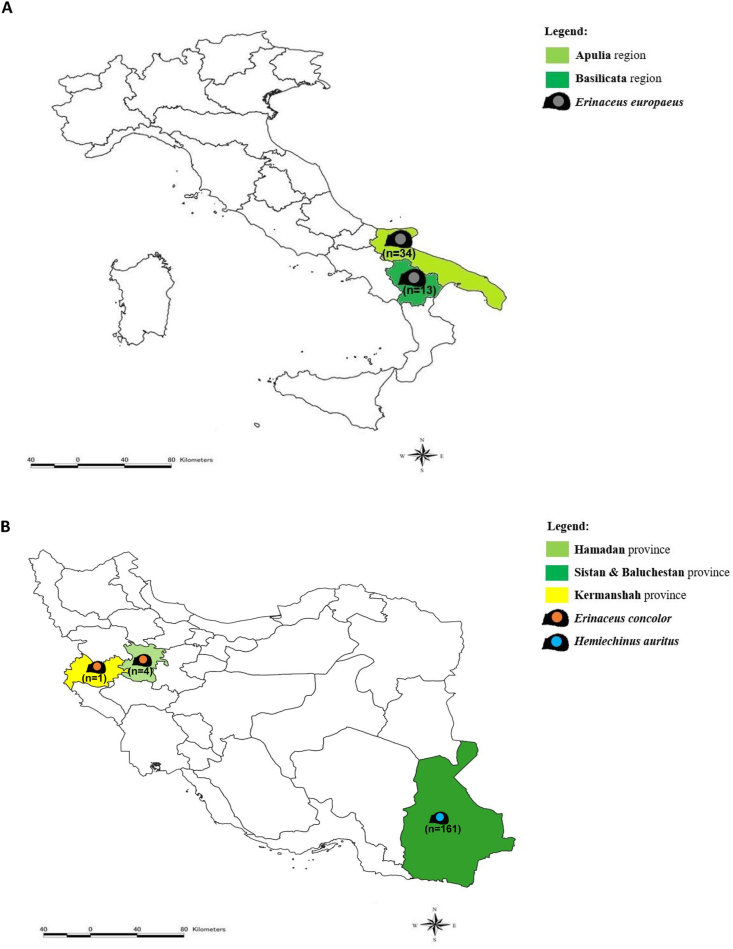

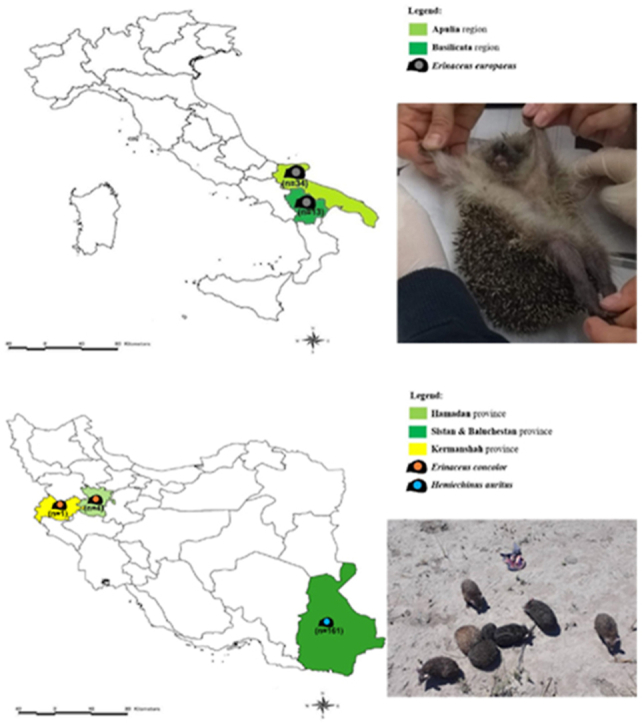

Animals (n = 213) were captured by hands in different regions of Iran and Italy during 2019/2020 (Fig. 1). Animals from Italy were prevenient of the clinical activities of the Recovery Center for Wildlife (CRAS), Puglia, Italy. The examined hedgehogs in Iran were road-killed animals. The hedgehogs were individually inspected for the presence of ectoparasites, which were collected with entomological forceps and placed in 1.5 ml tubes (Eppendorf, Aptaca Spa, Canelli, Italy) containing 70% alcohol. Ectoparasites were individualized, and 20% of them were molecularly processed per infested animal when the total number exceeded three, otherwise all ectoparasites collected on each individual were screened.

Fig. 1.

Map of the study area where hedgehogs were captured. A. Italy; B. Iran.

2.2. Ectoparasite species identification

Ectoparasites were separated by sex and life stage, and morphologically identified with a stereo microscope (Leica MS5) using dichotomous keys for ticks (Manilla, 1998; Estrada-Peña et al., 2004), and fleas (Smit, 1957). For the identification of mites, selected samples were mounted in Amman's Lactophenol on microscope slides and examined at 10 × , 20 × , and 40 × magnification with an optical microscope (Leica DM LB2). Dichotomous keys for hematophagous mites (Baker et al., 1956), and phoretic mites (Baker et al., 1956; Fain and Portús, 1979) were used for genus and species identification. Additionally, ticks and fleas were carefully checked for the presence of phoretic mites.

2.3. Molecular detection of pathogens and ectoparasite species

Genomic DNA of ectoparasites was extracted using an in-house protocol previously described (Ramos et al., 2015). The detection of arthropod-borne pathogens was performed through conventional polymerase chain reaction (PCR), using primers that amplify DNA of Rickettsia spp., Borrelia spp., and Anaplasmataceae (Table 1). For Rickettsia spp. all samples were firstly screened using primers for the gltA gene, and those positives were tested for the ompA gene to further characterize spotted fever group rickettsiae (SFG). DNA of Ehrlichia canis, Rickettsia slovaca, and B. burgdorferi s.l. were used as positive controls for each PCR reaction. Morphological identification of ticks was further confirmed by PCR using the primers forward 16S+1 (5′-CTGCTCAATGATTTTTTAAATTGCTGTGG-3′) and reverse Tick16S-2 (5′-TTACGCTGTTATCCCTAGAG-3′), which amplify a 460 base pair-sized (bp) fragment of the mitochondrial 16S rRNA gene (Black and Piesman, 1994), and for fleas with the primers forward LCO1490 (5′-GGTCAACAAATCATAAAGATATTGG-3′) and reverse HCO02198 (5′-TAAACTTCAGGGTGACCAAAAAATCA-3′), which amplify 710 bp of the cox1 gene of metazoan invertebrates (Folmer et al., 1994).

Table 1.

Primers for the detection of arthropod-borne pathogens.

| Pathogen | Gene | Amplicon size (bp) | Primer sequences | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rickettsia spp. | gltA | 401 | 5′GCAAGTATCGGTGAGGATGTAAT3′ 5′GCTTCCTTAAAATTCAATAAATCAGGAT3′ |

Labruna et al. (2004) |

| Rickettsia spp. | ompA | 632 | 5′ATGGCGAATATTTCTCCAAAA3′ 5′AGTGCAGCATTCGCTCCCCCT3′ |

Regnery et al. (1991) |

| Borrelia spp. | fla | 482 | 5′AGAGCAACTTACAGACGAAATTAAT3′ 5′CAAGTCTATTTTGGAAAGCACCTAA3′ |

Skotarczak et al. (2002) |

| Anaplasmataceae | 16S | 345 | 5′GGTACCYACAGAAGAAGTCC3′ 5′TAGCACTCATCGTTTACAGC3′ |

Parola et al. (2000) |

2.4. Phylogenetic analysis

PCR products were purified and sequenced in both directions using the same forward and reverse primers, employing the Big Dye Terminator v.3.1 chemistry in a 3130 Genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems, California, USA) in an automated sequencer (ABI-PRISM 377). Nucleotide sequences were edited, aligned, and analyzed using MEGA7 software and compared with sequences available on GenBank through the BLAST search tool. For phylogenetic analysis, ompA and gltA gene sequences of Rickettsia spp., and 16S rRNA gene sequences of Ehrlichia/Anaplasma spp. from this study were included along with those available in the GenBank database. Phylogenetic relationships were inferred using the maximum likelihood (ML) method after selecting the best-fitting substitution model. Evolutionary analyses were conducted with 1000 bootstrap replications using MEGA7 software (Kumar et al., 2016). Rickettsia prowazekii (DQ926853), R. akari (L01461), and Ehrlichia risticii (AF206300) sequences were used as outgroups for the gltA, ompA, and 16S rRNA phylogenetic trees, respectively.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to calculate relative and absolute frequencies, as well as mean intensity and mean abundance of ectoparasites. Exact binomial 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were established for proportions using the QP 2.0 software.

3. Results

3.1. Hedgehogs and ectoparasites collection

Of 213 hedgehogs examined (i.e., n = 166 from Iran, and n = 47 from Italy) the majority were Hemiechinus auritus (n = 161) followed by Erinaceus concolor (n = 5) in Iran, whereas in Italy all (n = 47) were identified as Erinaceus europaeus.

In Iran, most animals examined (92.2%; 153/166; 95% CI: 0.87–0.96) scored positive for tick infestation, with the majority being infested by the species Rhipicephalus turanicus (91.6%; 152/166; 95% CI: 0.86–0.94), and one individual infested by the species Hyalomma dromedarii (Table 2). Additionally, seven (4.2%; 95% CI: 0.02–0.09) individuals presented co-infestation by ticks and fleas (Table 3).

Table 2.

Ectoparasites found on Hemiechinus auritus, Erinaceus concolor (Iran), and Erinaceus europaeus (Italy) hedgehogs.

| Country/Ectoparasite |

Total |

Infested animals |

a Mean abundance |

b Mean intensity |

RF % |

AF/N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iran | Hemiechinus auritus (n = 161) | |||||

| Fleas (n = 6) | ||||||

| Archaeopsylla erinacei | 6 (3 M; 3 F) | 6 | 6 | 6 | 3.7 | 6/161 |

| Ticks (n = 256) | ||||||

| Hyalomma dromedarii | 2 (M) | 1 | 0.01 | 2 | 0.6 | 1/161 |

|

Rhipicephalus turanicus |

254 (146 M; 107 F; 1Ny) |

152 |

1.58 |

1.67 |

94.4 |

152/161 |

| Iran |

Erinaceus concolor (n = 5) |

|||||

| Fleas (n = 4) | ||||||

| Archaeopsylla erinacei | 1 (F) | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 20.0 | 1/5 |

| Ctenocephalides felis | 3 (F) | 1 | 0.6 | 3 | 20.0 | 1/5 |

| Tick (n = 1) | ||||||

|

Rhipicephalus turanicus |

1 (L) |

1 |

0.2 |

1 |

20.0 |

1/5 |

| Italy |

Erinaceus europaeus (n = 47) |

|||||

| Fleas (n = 265) | ||||||

| Archaeopsylla erinacei | 265 (80 M; 175 F) | 18 | 5.64 | 14.72 | 38.3 | 18/47 |

| Mites (n = 104) | ||||||

| Caparinia tripilis | 10 | 1 | 0.21 | 10 | 2.1 | 1/47 |

| Acarus nidicolous | 4 | 3 | 0.09 | 1.33 | 6.4 | 3/47 |

| Ornithonyssus spp. | 90 | 2 | 1.91 | 45 | 4.3 | 2/47 |

| Ticks (n = 13) | ||||||

| Haemaphysalis erinacei | 3 (M) | 2 | 0.06 | 1.5 | 4.3 | 2/47 |

| Rhipicephalus turanicus | 8 (1 M; 6 F; 1Ny) | 4 | 0.17 | 2 | 8.5 | 4/47 |

| Rhipicephalus sanguineus s.l. | 2 (L) | 1 | 0.04 | 2 | 2.1 | 1/47 |

Number of ectoparasites per total of examined animals.

Number of ectoparasites per total of infested animals. RF – relative frequency; AF – absolute frequency; N – number of captured animals; M – male; F – female; Ny – nymph; L – Larvae.

Table 3.

Co-infestation by ectoparasites on hedgehogs from Iran and Italy.

| Hedgehog species (infested/total) | Country | Tick species | Flea species | Mite species |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemiechinus auritus (6/161) | Iran | Rhipicephalus turanicus | Archaeopsylla erinacei | – |

| Erinaceus concolor (1/5) | Iran | Rhipicephalus turanicus | Archaeopsylla erinacei; Ctenocephalides felis | – |

| Erinaceus europaeus (1/47) | Italy | Rhipicephalus turanicus | Archaeopsylla erinacei | – |

| Erinaceus europaeus (1/47) | Italy | Rhipicephalus sanguineus sensu lato | Archaeopsylla erinacei | – |

| Erinaceus europaeus (1/47) | Italy | Haemaphysalis erinacei | Archaeopsylla erinacei | – |

| Erinaceus europaeus (1/47) | Italy | Haemaphysalis erinacei | Archaeopsylla erinacei | Ornithonyssus spp. |

| Erinaceus europaeus (2/47) | Italy | – | Archaeopsylla erinacei | Ornithonyssus spp. |

| Erinaceus europaeus (2/47) | Italy | – | Archaeopsylla erinacei | Acarus nidicolous |

| Erinaceus europaeus (1/47) | Italy | – | Archaeopsyllaaerinacei | Capariniaatripilis |

Phoresy.

In Italy 21 out of 47 individuals (44.7%; 95% CI: 0.31–0.60) were positive for ectoparasites (Table 2), predominantly fleas, which were all identified as Ar. erinacei. Co-infestation by fleas and mites, and by fleas and ticks, was detected in six (12.8%; 95% CI: 0.06–0.25) and four (8.5%; 95% CI: 0.03–0.20) animals, respectively, with one hedgehog presenting simultaneous infestation by fleas, ticks, and mites (Table 3). Phoretic behavior of C. tripilis mites on Ar. erinacei was detected in two female flea specimens from one animal in Italy with mites observed on their legs and head (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Caparinia tripilis mites in phoretic association with Archaeopsylla erinacei flea.

Molecular analysis confirmed the morphological identification for ticks and fleas, with nucleotide identity of 100% for Rh. turanicus (Accession number: MT229198) and Rhipicephalus sanguineus sensu lato (Accession number: MN944863), 99.62% for Haemaphysalis erinacei (Accession number: KX237633), and 100% for Ar. erinacei (Accession number: KM890990). Sequences for Hy. dromedarii and Ctenocephalides felis were not obtained in the present study.

3.2. Vector-borne pathogens detection

The molecular analysis for vector-borne pathogens detected Rickettsia spp. in 93.3% (n = 42/45; 95% CI: 0.81–0.98) of the fleas from Italy, but not in ticks and mites. In Iran, Rickettsia spp. was detected in 8.0% (n = 17/212; 95% CI: 0.05–0.12) of the Rh. turanicus ticks, and in 85.7% (n = 6/7; 95% CI: 0.44–0.99) of Ar. erinacei fleas. In addition, the 16S rRNA gene for Ehrlichia spp. and Anaplasma spp. was amplified in 4.2% (n = 9/212; 95% CI: 0.02–0.08) of the Rh. turanicus ticks. DNA of Borrelia spp. was not detected in the examined ectoparasites.

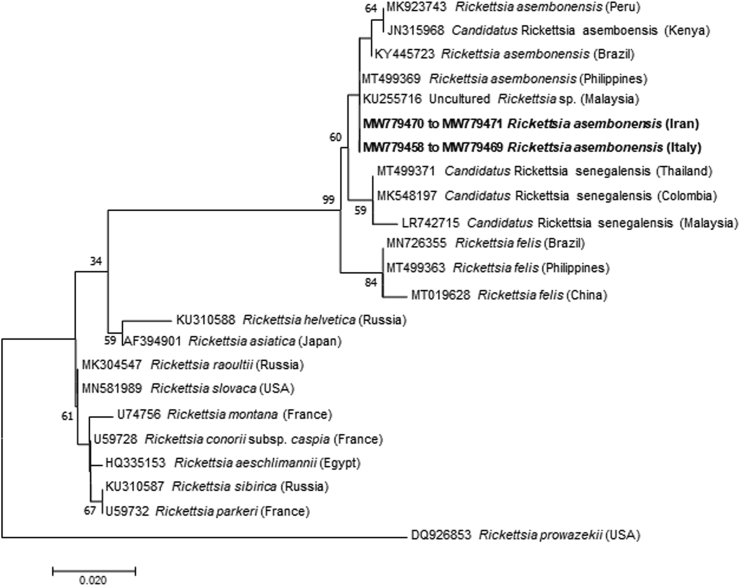

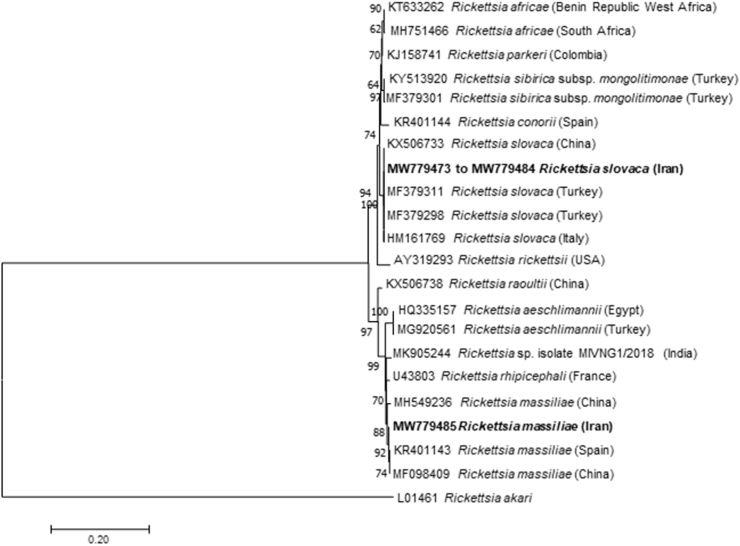

According to BLAST analysis, all gltA sequences of Rickettsia spp. detected in fleas presented 100% identity with Rickettsia asembonensis sequences available in the GenBank database (Accession numbers: MT499370; MT499369; KY445723). Whereas Rickettsia spp. ompA sequences from ticks presented from 99.84% to 100% nucleotide identity with R. slovaca (Accession numbers: MF379311; HM161769), except for one sample that was 99.84% identical to Rickettsia massiliae (Accession number: KR401143). The phylogenetic tree based on the partial gltA gene sequences showed that R. asembonensis from Ar. erinacei fleas from Italy and Iran assembled in a well-supported sister cluster that includes Rickettsia felis and other R. felis-like organisms (Fig. 3). The phylogenetic analysis of the ompA gene revealed that R. slovaca sequences from this study clustered with those from China, Turkey, and Italy (Fig. 4), and R. massiliae with those from China and Spain, as well as with Rickettsia rhipicephali from France (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic analysis of the gltA gene (345 bp) of Rickettsia asembonensis detected in this study (Bold) and relationship with other Rickettsia spp. The evolutionary history was inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method based on the Tamura 3-parameter model (Tamura, 1992). A discrete Gamma distribution was used to model evolutionary rate differences among sites (5 categories [+G, parameter = 0.2157]). GenBank accession number and country of origin are presented for each sequence.

Fig. 4.

Phylogenetic analysis of the ompA gene (579 bp) of Rickettsia slovaca and Rickettsia massiliae detected in this study (Bold) and relationship with other Rickettsia spp. The evolutionary history was inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method based on the Tamura 3-parameter model (Tamura, 1992). Initial tree(s) for the heuristic search were obtained automatically by applying Neighbor-Join and BioNJ algorithms to a matrix of pairwise distances estimated using the Maximum Composite Likelihood (MCL) approach, and then selecting the topology with superior log likelihood value. The rate variation model allowed for some sites to be evolutionarily invariable ([+I], 20.90% sites). GenBank accession number and country of origin are presented for each sequence.

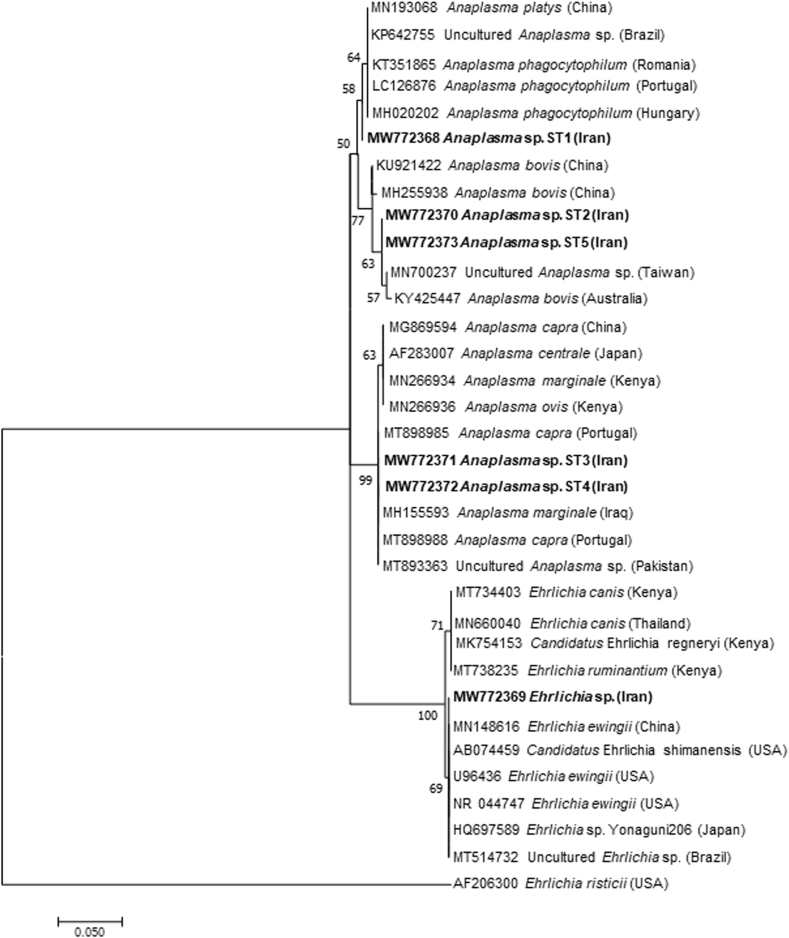

The sequences of the 16S rRNA gene revealed 99.57%–100% identity with Anaplasma spp. (Accession numbers: MN193068; KP642755; MH020202; MN700237; MW368828), except for one which was identical to Ehrlichia spp. (Accession numbers: MN148616; AB074459). The phylogenetic analysis of the 16S rRNA gene sequences showed that five sequence types (i.e., ST1 to ST5) of Anaplasma spp. were closely related with Anaplasma spp. of veterinary and public health concern (Fig. 5). The sequence from Ehrlichia sp. herein detected assembled with Ehrlichia ewingii from China and USA, Candidatus Ehrlichia shimanensis from USA, and Ehrlichia sp. Yanaguni206 from Japan (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Phylogenetic analysis of the 16S rRNA gene (281 bp) of Ehrlichia and Anaplasma spp. detected in this study (Bold) and relationship with other Ehrlichia/Anaplasma spp. The evolutionary history was inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method based on the Kimura 2-parameter model (Kimura, 1980). Initial tree(s) for the heuristic search were obtained automatically by applying Neighbor-Join and BioNJ algorithms to a matrix of pairwise distances estimated using the Maximum Composite Likelihood (MCL) approach, and then selecting the topology with superior log likelihood value. The rate variation model allowed for some sites to be evolutionarily invariable ([+I], 37.72% sites). GenBank accession number and country of origin are presented for each sequence.

Sequences herein obtained were submitted to GenBank under the accession numbers: MW779458 to MW779472 for R. asembonensis; MW779473 to MW779484 for R. slovaca; MW779485 for R. massiliae; MW772368, MW772370, MW772371, MW772372 and MW772373 for Anaplasma spp.; and MW772369 for Ehrlichia sp.

4. Discussion

This study assessed the occurrence of phoresy of C. tripilis mites on Ar. erinacei fleas in Italy, as well as of SFG rickettsiae, Ehrlichia sp., and Anaplasma spp. in the ectoparasite fauna of hedgehogs from Iran and Italy. Of major interest is the high prevalence of R. asembonensis in fleas collected from hedgehogs. To the best of our knowledge, no data is available regarding the phoretic association of C. tripilis mites on Ar. erinacei fleas infesting E. europaeus, with potential implications to animal health due to the host-parasite association these arthropods have with the European hedgehog. Indeed, C. tripilis mites are commonly detected on African hedgehogs, Atelerix albiventris (Kim et al., 2012; Moreira et al., 2013; Iacob and Iftinca, 2018), whereas E. europaeus is rarely reported harboring this mite species (Keymer et al., 1991). In general, animals affected by C. tripilis present dermatitis characterized by skin inflammation, scabs, crusting, hair loss and self-injuries in consequence of pruritus (Kim et al., 2012; Iacob and Iftinca, 2018; Garcês et al., 2020). Animals herein evaluated were apparently healthy, and due to the small size of C. tripilis mite, it was not possible to determine whether the individuals from which the phoresy was detected also presented mites on their body.

Phoresy of mites has been widely recorded on arthropods such as ants, bees (Joharchi et al., 2019), ticks (Karbowiak et al., 2013), psyllids (Liu et al., 2016), termites (Khaustov et al., 2017, 2019) and fleas (Karbowiak et al., 2013). These interactions have different implications according to the biology of the species involved, and might be beneficial, costly, or may present no effect on the arthropod host (Hodgkin et al., 2010). Studies on this phenomenon between mites and fleas are scant, and up to date none of them identified the degree to which phoretic mites affect fleas (Britt and Molyneux, 1983; Schwan, 1993; Karbowiak et al., 2013; Hastriter and Bush, 2014). Additionally, most studies on the phoretic behavior of mites have been performed on Coleoptera, Diptera and Hymenoptera (Norton, 1980; Khaustov and Frolov, 2018; Paraschiv et al., 2018; Durkin et al., 2019; Revainera et al., 2019). For example, phoresy of the mite species (i.e., Acarus farris, Acarus siro, Acarus nidicolous, Caloglyphus rhizoglyphoides, Histiostoma feroniarum and Tyrophagus putrescentiae) was recorded in ticks (i.e., Ixodes hexagonus) and fleas (i.e., Megabothris walkeri, Megabothris turbidus, Hystrichopsylla orientalis, Ctenophthalmus agyrtes) collected on small mammals from Poland (Karbowiak et al., 2013). In E. europaeus hedgehogs, this association was previously recorded in England for the mite species A. nidicolous on Ar. erinacei (Britt and Molyneux, 1983). However, in the present study no phoretic association was observed for this mite species. The high prevalence of Ar. erinacei in hedgehogs may favor the spreading of phoretic mites such as the pathogenic species, C. tripilis. Nevertheless, whether this association is harmful for the animal's health deserves further investigation, as it has been previously suggested that these two arthropod species may compete for the same sites on the host skin, and the absence of fleas may facilitate the establishment of this mite infestation on hedgehogs (Brockie, 1974). Infestation by Ornithonyssus spp. mites on E. europaeus hedgehogs has been also herein recorded for the first-time in two animals. Among the species of this genus, only the zoonotic tropical rat mite, Ornithonyssus bacoti, has been reported on the African hedgehog, A. albiventris (d’Ovidio et al., 2018).

Hedgehogs captured in Iran were rarely infested by Ar. erinacei fleas whereas those from Italy presented a high flea infestation rate. This flea species is commonly found infesting hedgehogs (Goz et al., 2016; Zurita et al., 2018), and has been associated with zoonotic pathogens such as Rickettsia spp. and Bartonella henselae (Hornok et al., 2014). In addition, despite being considered the hedgehog flea, this insect also infests other hosts such as cats, dogs (Gilles et al., 2008), foxes (Marié et al., 2012) and even humans (Greigert et al., 2020). The lower prevalence of fleas in the animals from Iran could be related to the fact that the examined hedgehogs were road-killed, which may cause the ectoparasites to abandon the host soon after the animal dies. In addition, climate factors could be also associated with this low prevalence, since the hot weather may reduce the overall abundance of fleas (Russell et al., 2018). Conversely, ticks (i.e., Rh. turanicus, Hy. dromedarii), especially Rh. turanicus were detected with high prevalence (i.e., 92.2%) in animals from Iran, whereas in Italy the prevalence of ticks (i.e., Rh. turanicus, Rh. sanguineus s.l., Ha. erinacei) was low (i.e., 14.9%). These differences in prevalence of ectoparasites in the animals collected in Italy and Iran could be related to climate factors (arid and semi-arid climate in Iran, and temperate climate in Italy), and to the hedgehog species captured, which diverged between these two countries. The tick species above are regarded as potential vectors of pathogens (Khaldi et al., 2012; Wei et al., 2015; Orkun et al., 2019). For example, Rickettsia aeschlimannii, R. massiliae and Anaplasma marginale have been detected in Rh. turanicus (Wei et al., 2015; Khodadadi et al., 2021), SFG rickettsiae and Babesia sp. in Ha. erinacei (Khaldi et al., 2012; Orkun et al., 2019), and Coxiella burnetti and Rickettsia spp. in Hy. dromedarii (Loftis et al., 2006; Kernif et al., 2012).

The high prevalence of R. asembonensis (i.e., 93.3%) in Ar. erinacei fleas recorded in the present study is confirmed by its retrieval in fleas worldwide (Loyola et al., 2018; Maina et al., 2019; Nguyen et al., 2020). A R. felis-like organism presenting 100% nucleotide identity with R. asembonensis has been previously reported with high prevalence (i.e., 96.0%) in Ar. erinacei fleas in Germany, as uncultured Rickettsia sp. (Gilles et al., 2009), and in Portugal with prevalence of 47.0% (Barradas et al., 2021). In fact, R. asembonensis is a R. felis-like bacterium detected in fleas collected on domestic animals and from human dwellings in Kenya (Jiang et al., 2013), and recently characterized as a novel Rickettsia species from C. felis (Maina et al., 2016). Despite being closely related to R. felis, the pathogenicity of R. asembonensis to humans is still unknown (Jiang et al., 2013; Loyola et al., 2018). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of R. asembonensis in Italy and the high prevalence herein detected in fleas collected from hedgehogs is particularly important as this animal species could act as reservoir for this bacterium in the studied area. However, further investigations are required to confirm the role of this mammal species in the epidemiology of R. asembonensis.

Rickettsia slovaca has been herein detected for the first time in Rh. turanicus ticks collected from H. auritus in Iran. This zoonotic spotted fever group bacterium is the main etiological agent of SENLAT (Scalp Eschar and Neck Lymphadenopathy after tick bite) in humans, an illness characterized by the enlargement of neck lymph nodes and scalp eschar after a tick bite (Hocquart et al., 2019; Barlozzari et al., 2021). In addition, apart from humans, R. slovaca has been reported in other vertebrate host species including domestic animals (e.g., dogs; Iatta et al., 2021), and wildlife (e.g., rodents, wild boars; Martello et al., 2019; Sgroi et al., 2020). Ticks of the genus Dermacentor (e.g., Dermacentor marginatus, Dermacentor reticulatus) are the main vectors of this bacterium (Portillo et al., 2015); however, it has also been associated with other tick species such as Ixodes ricinus, Rhipicephalus bursa, and Hyalomma spp. (Kachrimanidou et al., 2010; Orkun et al., 2019; Remesar et al., 2019). The detection of R. slovaca in Rh. turanicus collected from hedgehogs suggests that this tick species, as well as hedgehogs, could be involved in the transmission cycle of this bacterium in Iran. Moreover, this tick species has also been collected on humans (Eremeeva and Stromdahl, 2011), advocating further studies on the epidemiology of zoonotic SFG rickettsiae and the sympatric occurrence of Rh. turanicus ticks, hedgehogs, humans, and domestic animals.

Rickettsia massiliae was also herein detected in a specimen of Rh. turanicus female tick in Iran. This bacterium has been suggested to be one of the causative agents of the Mediterranean spotted fever (Portillo et al., 2015), and it has been associated with human cases of SENLAT in Romania (Zaharia et al., 2016). Ticks of the genus Rhipicephalus are suggested as the main vectors of R. massiliae, with transovarial and transstadial transmission being experimentally proved in Rh. turanicus (Matsumoto et al., 2005). Additionally, this bacterium has been recently detected in Rh. sanguineus s.l. ticks collected on E. europaeus hedgehogs (Barradas et al., 2021), again demonstrating that hedgehogs may play an important role in the epidemiology of vector-borne diseases.

Rhipicephalus turanicus ticks from Iran were also positive for Anaplasma and Ehrlichia spp., with five sequence types being detected for Anaplasma spp. and one for Ehrlichia sp. The phylogenetic analysis of the 16S rRNA gene demonstrated that the pathogens herein detected in Rh. turanicus ticks were closely related to species infecting humans (e.g., A. phagocytophilum, E. ewingii), and domestic animals (e.g., Anaplasma platys, A. phagocytophilum, Anaplasma bovis, Anaplasma capra, A. marginale). Previous studies have reported the presence of Anaplasmataceae in hedgehogs and their ticks (Silaghi et al., 2012; Khodadadi et al., 2021). For example, A. marginale has been detected in H. auritus and its Rh. turanicus ticks in southeastern Iran (Khodadadi et al., 2021), and A. phagocytophilum in E. europaeus and its Ixodes hexagonus and I. ricinus ticks in Germany (Silaghi et al., 2012). Our results confirm the presence of bacterial DNA of Anaplasma spp. and Ehrlichia sp. in Rh. turanicus ticks collected on hedgehogs in Iran, which deserves further investigation to assess the circulation of these pathogens among hedgehogs, domestic animals, and humans.

Finally, the absence of Borrelia spp. in the ectoparasites examined in the present study could be related to the vector competence of the arthropod species herein detected, as the main vectors for B. burgdorferi s.l. are ticks of the I. ricinus complex (Remesar et al., 2019), which have not been herein detected. Nevertheless, hedgehogs have already been suggested as reservoirs for these bacteria in Europe (Skuballa et al., 2007, 2012).

5. Conclusion

Data herein presented demonstrated a new phoretic association between C. tripilis mites and Ar. erinacei fleas collected on European hedgehogs. This could be a strategy this mite species uses to spread among hedgehog populations given the close host-parasite relationship between Ar. erinacei and E. europaeus. Additionally, we report the presence of SFG rickettsiae in ticks and fleas, and Anaplasma spp. and Ehrlichia sp. in ticks, with Ar. erinacei fleas presenting a high prevalence of R. asembonensis, a R. felis-like organism detected in many arthropods worldwide, suggesting that hedgehogs may play a role as a reservoir host for these vector-borne pathogens. In this aspect, due to the widespread presence of hedgehogs in rural and urban environments, they should be considered a source of ectoparasites in these areas, which is epidemiologically relevant for the circulation of arthropod-borne infectious agents among hedgehogs, domestic animals, and humans.

Ethical standards

All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed.

Financial Support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This study was planned under the academic agreement between the Bu-Ali Sina University Hamedan (Iran) and the University of Bari (Italy). We thank Giada Annoscia (University of Bari) for technical support, Roberto Lombardi for assisting in sampling in Italy, and Salman Zafari, Leili Moradi, Hamidreza Javaheri, Ali Mirzabeigi, and Zahra Bahiraei for assisting in sampling in Iran.

References

- Baker E.W., Evans T.M., Gould D.J., Hull W.B., Keegan H.L., editors. A Manual of Parasitic Mites of Medical or Economic Importance. National Pest Control Association, Inc; New York: 1956. p. 170. [Google Scholar]

- Balashov Y.S. Types of parasitism of acarines and insects on terrestrial vertebrates. Entomol. Rev. 2006;86:957–971. doi: 10.1134/S0013873806080112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barlozzari G., Romiti F., Zini M., Magliano A., De Liberato C., Corrias F., Capponi G., Galli L., Scarpulla M., Montagnani C. Scalp eschar and neck lymphadenopathy by Rickettsia slovaca after Dermacentor marginatus tick bite case report: multidisciplinary approach to a tick-borne disease. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021;21:103. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-05807-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barradas P.F., Mesquita J.R., Mateus T.L., Ferreira P., Amorin I., Gärtner F., de Sousa R. Molecular detection of Rickettsia spp. in ticks and fleas collected from rescued hedgehogs (Erinaceus europaeus) in Portugal. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2021;83:449–460. doi: 10.1007/s10493-021-00600-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann J. Tiny mites on a great journey - a review on scutacarid mites as phoronts and inquilines (Heterostigmatina, Pygmephoroidea, Scutacaridae) Acarologia. 2018;58:192–251. doi: 10.24349/acarologia/20184238. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Black W.4., Piesman J. Phylogeny of hard-and soft-tick taxa (Acari: Ixodida) based on mitochondrial 16S rDNA sequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994;91:10034–10038. doi: 10.1073/2Fpnas.91.21.10034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackman S.W., Evans G.O. Observations on a mite (Poecilochirus davydovae) predatory on the eggs of burying beetles (Nicrophorus vespilloides) with a review of its taxonomic status. J. Zool. 1994;234:217–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7998.1994.tb06070.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bouyer D.H., Stenos J., Crocquet-Valdes P., Moron C.G., Popov V.L., Zavala-Velazquez J.E., Foil L.D., Stothard D.R., Azad A.F., Walker D.H. Rickettsia felis: molecular characterization of a new member of the spotted fever group. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2001;51:339–347. doi: 10.1099/00207713-51-2-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britt D.P., Molyneux D.H. Phoretic associations between hypopi of Acarus nidicolous (Acari, Astigmata, Acaridae) and fleas of British small mammals. Ann. Parasitol. Hum. Comp. 1983;58:95–98. doi: 10.1051/parasite/1983581095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockie R.E. The hedgehog mange mite, Caparinia tripilis, in New Zealand. N. Z. Vet. J. 1974;22:243–247. doi: 10.1080/00480169.1974.34179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Sousa K.C.M., Calchi A.C., Herrera H.M., Dumler J.S., Barros-Battesti D.M., MacHado R.Z., André M.R. Anaplasmataceae agents among wild mammals and ectoparasites in Brazil. Epidemiol. Infect. 2017;145:3424–3437. doi: 10.1017/S095026881700245X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d'Ovidio D., Noviello E., Santoro D. Prevalence and zoonotic risk of tropical rat mite (Ornithonyssus bacoti) in exotic companion mammals in southern Italy. Vet. Dermatol. 2018;29 doi: 10.1111/vde.12684. 522–e174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durkin E.S., Proctor H., Luong L.T. Life history of Macrocheles muscaedomesticae (Parasitiformes: Macrochelidae): new insights on life history and evidence of facultative parasitism on Drosophila. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2019;79:309–321. doi: 10.1007/s10493-019-00431-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eremeeva M.E., Stromdahl E.Y. New spotted fever group Rickettsia in a Rhipicephalus turanicus tick removed from a child in eastern Sicily, Italy. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2011;84:99–101. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.10-0176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estrada-Peña A., Bouattour A., Camicas J.L., Walker A.R. University of Zaragoza; 2004. Ticks of Domestic Animals in the Mediterranean Region: A Guide to Identification of Species; p. 131p. [Google Scholar]

- Fain A., Portús M. Two new parasitic mites (Acari, Astigmata) from the Algerian hedgehog Aethechinus algirus, in Spain. Rev. Iber. Parasitol. 1979;39:577–585. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer K., Walton S. Parasitic mites of medical and veterinary importance - is there a common research agenda? Int. J. Parasitol. 2014;44:955–967. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folmer O., Black M., Hoeh W., Luts R., Vrijenhoek R. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol. Mar. Biol. Biotechnol. 1994;3:294–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcês A., Soeiro V., Lóio S., Sargo R., Sousa L., Silva F., Pires I. Outcomes, mortality causes, and pathological findings in European hedgehogs (Erinaceus europeus, Linnaeus 1758): a seventeen year retrospective analysis in the North of Portugal. Animals. 2020;10:1305. doi: 10.3390/ani10081305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilles J., Just F.T., Silaghi C., Pradel I., Passos L.M.F., Lengauer H., Hellmann K., Pfister K. Rickettsia felis in fleas, Germany. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2008;14:1294–1296. doi: 10.3201/eid1408.071546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilles J., Silaghi C., Just F., Pradel I., Pfister K. Polymerase chain reaction detection of Rickettsia felis-like organism in Archaeopsylla erinacei (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae) from Bavaria, Germany. J. Med. Entomol. 2009;46:703–707. doi: 10.1603/033.046.0338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goz Y., Yilmaz A.B., Aydin A., Dicle Y. Ticks and fleas infestation on east hedgehogs (Erinaceus concolor) in Van province, eastern region of Turkey. J. Arthropod. Borne Dis. 2016;10:50–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco G., Zarea A.N.K., Sgroi G., Tempesta M., D'Alessio N., Lanave G., Bezerra-Santos M.A., Iatta R., Veneziano V., Otranto D., Chomel B. Zoonotic Bartonella species in Eurasian wolves and other free-ranging wild mammals from Italy. Zoonoses Publ. Health. 2021 doi: 10.1111/zph.12827. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greigert V., Brunet J., Ouarti B., Laroche M., Pfaff A.W., Henon N., Lemoine J.P., Mathieu B., Parola P., Candolfi E., Abou-Bacar A. The trick of the hedgehog: case report and short review about Archaeopsylla erinacei (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae) in human health. J. Med. Entomol. 2020;57:318–323. doi: 10.1093/jme/tjz157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassell J.M., Begon M., Ward M.J., Fèvre E.M. Urbanization and disease emergence: dynamics at the wildlife–livestock–human interface. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2017;32:55–67. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2016.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastriter M.W., Bush S.E. Description of Medwayella independencia (Siphonaptera, Stivaliidae), a new species of flea from Mindanao Island, the Philippines and their phoretic mites, and miscellaneous flea records from the Malay Archipelago. ZooKeys. 2014;408:107–123. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.408.7479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hocquart M., Drouet H., Levet P., Raoult D., Parola P., Eldin C. Cellulitis of the face associated with SENLAT caused by Rickettsia slovaca detected by qPCR on scalp eschar swab sample: an unusual case report and review of literature. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2019;10:1142–1145. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2019.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin L.K., Elgar M.A., Symonds M.R.E. Positive and negative effects of phoretic mites on the reproductive output of an invasive bark beetle. Aust. J. Zool. 2010;58:198–204. doi: 10.1071/ZO10034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hornok S., Földvári G., Rigó K., Meli M.L., Tóth M., Molnár V., Gönczi E., Farkas R., Hofmann-Lehmann R. Vector-borne agents detected in fleas of the Northern white-breasted hedgehog. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2014;14:74–76. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2013.1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houck M.A., Cohen A.C. The potential role of phoresy in the evolution of parasitism: radiolabelling (tritium) evidence from an astigmatid mite. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 1995;19:677–694. doi: 10.1007/BF00052079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Houck M.A., Qin H., Roberts H.R. Hantavirus transmission: potential role of ectoparasites. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2004;1:75–79. doi: 10.1089/153036601750137723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacob O., Iftinca A. The dermatitis by Caparinia tripilis and Microsporum, in African pygmy hedgehog (Atelerix albiventris) in Romania - first report. Braz. J. Vet. Parasitol. 2018;27:584–588. doi: 10.1590/S1984-296120180053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iatta R., Sazmand A., Nguyen V.L., Nemati F., Ayaz M.M., Bahiraei Z., Zafari S., Giannico A., Greco G., Dantas-Torres F., Otranto D. Vector-borne pathogens in dogs of different regions of Iran and Pakistan. Parasitol. Res. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s00436-020-06992-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J., Maina A.N., Knobel D.L., Cleaveland S., Laudisoit A., Wamburu K., Ogola E., Parola P., Breiman R.F., Njenga M.K., Richards A.L. Molecular detection of Rickettsia felis and Candidatus Rickettsia asemboensis in fleas from human habitats, Asembo, Kenya. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2013;13:550–558. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2012.1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joharchi O., Tolstikov A.V., Khaustov A.A., Khaustov V.A., Sarcheshmeh M.A. Review of some mites (Acari: Laelapidae) associated with ants and bumblebees in Western Siberia, Russia. Zootaxa. 2019;4613 doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.4613.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julian E., Krüger A., Rakotondranary S.J., Ratovonamana R.Y., Poppert S., Ganzhorn J.U., Tappe D. Molecular detection of Rickettsia spp., Borrelia spp., Bartonella spp. and Yersinia pestis in ectoparasites of endemic and domestic animals in southwest Madagascar. Acta Trop. 2020;205:105339. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2020.105339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabeya H., Colborn J.M., Bai Y., Lerdthusnee K., Richardson J.H., Maruyama S., Kosoy M.Y. Detection of Bartonella tamiae DNA in ectoparasites from rodents in Thailand and their sequence similarity with bacterial cultures from Thai patients. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2010;10:429–434. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2009.0124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kachrimanidou M., Souliou E., Pavlidou V., Antoniadis A., Papa A. First detection of Rickettsia slovaca in Greece. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2010;50:93–96. doi: 10.1007/s10493-009-9283-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karbowiak G., Solarz K., Asman M., Wròblewski Z., Slivinska K., Werszsko J. Phoresy of astigmatic mites on ticks and fleas in Poland. Biol. Lett. 2013;50:87–94. doi: 10.2478/biolet-2013-0007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kernif T., Djerbouh A., Mediannikov O., Ayach B., Rolain J.M., Raoult D., Parola P., Bitam I. Rickettsia africae in Hyalomma dromedarii ticks from sub-Saharan Algeria. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2012;3:377–379. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2012.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keymer I.F., Gibson E.A., Reynolds D.J. Zoonoses and other findings in hedgehogs (Erinaceus europaeus): a survey of mortality and review of the literature. Vet. Rec. 1991;128:245–249. doi: 10.1136/vr.128.11.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaldi M., Socolovschi C., Benyettou M., Barech G., Biche M., Kernif T., Raoult D., Parola P. Rickettsiae in arthropods collected from the North African hedgehog (Atelerix algirus) and the desert hedgehog (Paraechinus aethiopicus) in Algeria. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2012;35:117–122. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaustov A.A., Frolov A.V. A new species, new genus and new records of heterostigmatic mites (Acari: Heterostigmata) phoretic on scarab beetles of the subfamily Orphninae (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) Zootaxa. 2018;4514:181–201. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.4514.2.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaustov A.A., Hugo-Coetzee E.A., Ermilov S.G. A new genus of the mite family Scutacaridae (Acari: Heterostigmata) associated with Trinervitermes trinervoides (Isoptera: Termitidae) from South Africa. Zootaxa. 2017;4258:462–476. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.4258.5.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaustov A.A., Hugo-Coetzee E.A., Ermilov S.G., Theron P.D. A new genus and species of the family Microdispidae (Acari: Heterostigmata) associated with Trinervitermes trinervoides (Sjöstedt) (Isoptera: Termitidae) from South Africa. Zootaxa. 2019;4647:104–114. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.4647.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khodadadi N., Nabavi R., Sarani A., Saadati D., Ganjali M., Mihalca A.D., Otranto D., Sazmand A. Identification of Anaplasma marginale in long-eared hedgehogs (Hemiechinus auritus) and their Rhipicephalus turanicus ticks in Iran. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2021;12:101641. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2020.101641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D.H., Oh D.S., Ahn K.S., Shin S.S. An outbreak of Caparinia tripilis in a colony of African pygmy hedgehogs (Atelerix albiventris) from Korea. Kor. J. Parasitol. 2012;50:151–156. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2012.50.2.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 1980;16:111–120. doi: 10.1007/BF01731581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krawczyk A.I., Van Leeuwen A.D., Jacobs-Reitsma W., Wijnands L.M., Bouw E., Jahfari S., Van Hoek A.H.A.M., Van Der Giessen J.W.B., Roelfsema J.H., Kroes M., Kleve J., Dullemont Y., Sprong H., De Bruin A. Presence of zoonotic agents in engorged ticks and hedgehog faeces from Erinaceus europaeus in (sub) urban areas. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:4–9. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-0814-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Stecher G., Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labruna M.B., Whitworth T., Bouyer D.H., McBride J., Camargo L.M.A., Camargo E.P., Popov V., Walker D.H. Rickettsia bellii and Rickettsia amblyommii in Amblyomma ticks from the state of Rondônia, western Amazon, Brazil. J. Med. Entomol. 2004;41:1073–1081. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-41.6.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Li J., Guo K., Qiao H., Xu R., Chen J., Xu C., Chen J. Seasonal phoresy as an overwintering strategy of a phytophagous mite. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:1–8. doi: 10.1038/srep25483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loftis A.D., Reeves W.K., Szumlas D.E., Abbassy M.M., Helmy I.M., Moriarity J.R., Dasch G.A. Rickettsial agents in Egyptian ticks collected from domestic animals. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2006;40:67–81. doi: 10.1007/s10493-006-9025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loyola S., Flores-Mendoza C., Torre A., Kocher C., Melendrez M., Luce-Fedrow A., Maina A.N., Richards A.L., Leguia M. Rickettsia asembonensis characterization by multilocus sequence typing of complete genes, Peru. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2018;24:931–933. doi: 10.3201/eid2405.170323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maina A.N., Jiang J., Luce-Fedrow A., St John H.K., Farris C.M., Richards A.L. Worldwide presence and features of flea-borne Rickettsia asembonensis. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019;5:334. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2018.00334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maina A.N., Luce-Fedrow A., Omulo S., Hang J., Chan T.-C., Ade F., Jima D.D., Ogola E., Ge H., Breiman R.F., Njenga M.K., Richards A.L. Isolation and characterization of a novel Rickettsia species (Rickettsia asembonensis sp. nov) obtained from cat fleas (Ctenocephalides felis) Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016;66:4512–4517. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.001382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manilla G. Ixodida. Calderini; Bologna: 1998. Fauna d'Italia XXXVI - Acari; p. 280p. [Google Scholar]

- Marié J., Davoust B., Socolovschi C., Mediannikov O., Roqueplo C., Beaucournu J.C., Raoult D., Parola P. Rickettsiae in arthropods collected from red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) in France. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2012;35:59–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martello E., Mannelli A., Grego E., Ceballos L.A., Ragagli C., Stella M.C., Tomassone L. Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato and spotted fever group rickettsiae in small rodents and attached ticks in the Northern Apennines, Italy. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2019;10:862–867. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2019.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto K., Ogawa M., Brouqui P., Raoult D., Parola P. Transmission of Rickettsia massiliae in the tick, Rhipicephalus turanicus. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2005;19:263–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2005.00569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millán J., Travaini A., Cevidanes A., Sacristán I., Rodríguez A. Assessing the natural circulation of canine vector-borne pathogens in foxes, ticks and fleas in protected areas of Argentine Patagonia with negligible dog participation. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2019;8:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ijppaw.2018.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira A., Troyo A., Calderón-Arguedas O. First report of acariasis by Caparinia tripilis in African hedgehogs, (Atelerix albiventris), in Costa Rica. Braz. J. Vet. Parasitol. 2013;22:155–158. doi: 10.1590/s1984-29612013000100029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen V., Colella V., Greco G., Fang F., Nurcahyo W., Hadi U.K., Venturina V., Tong K.B.Y., Tsai Y., Taweethavonsawat P., Tiwananthagorn S., Tangtrongsup S., Le T.Q., Bui K.L., Do T., Watanabe M., Rani P.A.M.A., Dantas-Torres F., Halos L., Beugnet F., Otranto D. Molecular detection of pathogens in ticks and fleas collected from companion dogs and cats in East and Southeast Asia. Parasit Vectors. 2020;13:420. doi: 10.1186/s13071-020-04288-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton R.A. Observations on phoresy by oribatid mites (Acari: Oribatei) Int. J. Acarol. 1980;6:121–130. doi: 10.1080/01647958008683206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Orkun O., Çakmak A., Nalbantoglu S., Karaer Z. Molecular detection of a novel Babesia sp. and pathogenic spotted fever group rickettsiae in ticks collected from hedgehogs in Turkey: Haemaphysalis erinacei, a novel candidate vector for the genus Babesia. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2019;69:190–198. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2019.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paraschiv M., Martínez-Ruiz C., Fernández M.M. Dynamic associations between Ips sexdentatus (Coleoptera: Scolytinae) and its phoretic mites in a Pinus pinaster forest in northwest Spain. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2018;75:369–381. doi: 10.1007/s10493-018-0272-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parola P., Roux V., Camicas J.L., Baradji I., Brouqui P., Raoult D. Detection of ehrlichiae in African ticks by polymerase chain reaction. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2000;94:707–708. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(00)90243-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portillo A., Santibáñez S., García-Álvarez L., Palomar A.M., Oteo J.A. Rickettsioses in Europe. Microb. Infect. 2015;17:834–838. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pourmohammadi B., Mohammadi-Azni S. Molecular detection of Leishmania major in Hemiechinus auritus: a potential reservoir of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis in Damghan, Iran. J. Arthropod. Borne Dis. 2019;13:334–343. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos R.A.N., Campbell B.E., Whittle A., Lia R.P., Montarsi F., Parisi A., Dantas-Torres F., Wall R., Otranto D. Occurrence of Ixodiphagus hookeri (Hymenoptera: Encyrtidae) in Ixodes ricinus (Acari: Ixodidae) in southern Italy. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2015;6:234–236. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regnery R.L., Olson J.G., Perkins B.A., Bibb W. Serological response to “Rochalimaea henselae” antigen in suspected cat‐scratch disease. Lancet. 1992;339:1443–1445. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92032-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regnery R.L., Spruill C.L., Plikaytis B.D. Genotypic identification of Rickettsiae and estimation of intraspecies sequence divergence for portions of two rickettsial genes. J. Bacteriol. 1991;173:1576–1589. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.5.1576-1589.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remesar S., Díaz P., Portillo A., Santibáñez S., Prieto A., Díaz-Cao J.M., López C.M., Panadero R., Fernández G., Díez-Baños P., Oteo J.A. Prevalence and molecular characterization of Rickettsia spp. in questing ticks from north-western Spain. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2019;79:267–278. doi: 10.1007/s10493-019-00426-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revainera P.D., Salvarrey S., Santos E., Arbulo N., Invernizzi C., Plischuk S., Abrahamovich A., Maggi M.D. Phoretic mites associated to Bombus pauloensis and Bombus bellicosus (Hymenoptera: Apidae) from Uruguay. J. Apicult. Res. 2019;58:455–462. doi: 10.1080/00218839.2018.1521775. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Russell R.E., Abbott R.C., Tripp D.W., Rocke T.E. Local factors associated with on-host flea distributions on prairie dog colonies. Ecol. Evol. 2018;8:8951–8972. doi: 10.1002/ece3.4390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwan T.G. Sex ratio and phoretic mites of fleas (Siphonaptera: Pulicidae and Hystrichopsyllidae) on the Nile grass rat (Arvicanthis niloticus) in Kenya. J. Med. Entomol. 1993;30:122–135. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/30.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sgroi G., Iatta R., Lia R.P., D’Alessio N., Manoj R.R.S., Veneziano V., Otranto D. Spotted fever group Rickettsiae in Dermacentor marginatus from wild boars in Italy. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1111/tbed.13859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silaghi C., Skuballa J., Thiel C., Pfister K., Petney T., Pfäffle M., Taraschewski H., Passos L.M. The European hedgehog (Erinaceus europaeus)–a suitable reservoir for variants of Anaplasma phagocytophilum? Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2012;3:49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson V.R. Wild animals as reservoirs of infectious diseases in the UK. Vet. J. 2002;163:128–146. doi: 10.1053/tvjl.2001.0662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skotarczak B., Wodecka B., Hermanowska-Szpakowicz T. Sensitivity of PCR method for detection of DNA of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in different isolates. Przegl. Epidemiol. 2002;56:73–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skuballa J., Oehme R., Hartelt K., Petney T., Bücher T., Kimmig P., Taraschewski H. European hedgehogs as hosts for Borrelia spp., Germany. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2007;13:952–953. doi: 10.3201/eid1306.070224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skuballa J., Petney T., Pfäffle M., Oehme R., Hartelt K., Fingerle V., Kimmig P., Taraschewski H. Occurrence of different Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato genospecies including B. afzelii, B. bavariensis, and B. spielmanii in hedgehogs (Erinaceus spp.) in Europe. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2012;3:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2011.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit F.G.A.M. Royal Entomological Society of London; London: 1957. Handbooks for Identification of British Insects: Siphonaptera; p. 94. [Google Scholar]

- Speck S., Perseke L., Petney T., Skuballa J., Pfäffle M., Taraschewski H., Bunnell T., Essbauer S., Dobler G. Detection of Rickettsia helvetica in ticks collected from European hedgehogs (Erinaceus europaeus, Linnaeus, 1758) Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2013;4:222–226. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions when there are strong transition-transversion and G+ C-content biases. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1992;9:678–687. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Q.Q., Guo L.P., Wang A.D., Mu L.M., Zhang K., Chen C.F., Zhang W.J., Wang Y.Z. The first detection of Rickettsia aeschlimannii and Rickettsia massiliae in Rhipicephalus turanicus ticks, in northwest China. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:631. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-1242-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaharia M., Popescu C.P., Florescu S.A., Ceausu E., Raoult D., Parola P., Socolovschi C. Rickettsia massiliae infection and SENLAT syndrome in Romania. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2016;7:759–762. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2016.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurita A., Callejón R., De Rojas M., Cutillas C. Morphological, biometrical and molecular characterization of Archaeopsylla erinacei (Bouché, 1835) Bull. Entomol. Res. 2018;108:726–738. doi: 10.1017/S0007485317001274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]